Abstract

Background

Sleep duration is associated with stroke risk and is one of eight essential components of cardiovascular health according to the American Heart Association. As stroke disproportionately burdens Black and Hispanic populations in the United States, we hypothesized that long and short sleep duration would be associated with greater subclinical carotid atherosclerosis, a precursor of stroke, in the racially and ethnically diverse Northern Manhattan Study (NOMAS).

Methods

NOMAS is a study of community-dwelling adults. Self-reported nightly sleep duration and daytime sleepiness were collected between 2006-2011. Carotid plaque presence, total plaque area, and intima media thickness were measured by ultrasound between 1999-2008. Linear and logistic regression models examined the cross-sectional associations of sleep duration groups (primary exposure) or daytime sleepiness (secondary exposure) with measures of carotid atherosclerosis. Models adjusted for age, time between ultrasound and sleep data collection, sex, race/ethnicity, education, health insurance, smoking, alcohol use, physical activity, body mass index, hypertension, diabetes, hypercholesterolemia, and cardiac disease.

Results

The sample (n=1,553) had a mean age of 64.7±8.5 years and was 61.9% female, 64.8% Hispanic and 18.2% non-Hispanic Black. Of the sample, 55.6% had carotid plaque, 22.3% reported nightly short sleep (<7 hours), 66.6% intermediate sleep (≥7 and <9 hours), and 11.1% long sleep (≥9 hours). Compared to intermediate sleep, long sleep was associated with greater odds of carotid plaque presence relative to plaque absence (OR 1.6, 95% CI 1.1-2.4) and larger total plaque area (OR 1.4, 95% CI 1.0-1.9) after full covariate adjustment. Short sleep and daytime sleepiness were not significantly associated with any carotid measures.

Conclusions

The association between long sleep and subclinical carotid atherosclerosis may explain prior associations between long sleep and stroke.

Keywords: subclinical atherosclerosis, carotid plaque, carotid ultrasound, vascular risk factors, sleep

INTRODUCTION

Stroke disproportionately affects Black and Hispanic adults relative to non-Hispanic White adults in the United States (US). A prior analysis of the Northern Manhattan Study (NOMAS) demonstrated a 2.4-fold greater incidence of stroke among non-Hispanic Black adults and 2.0-fold greater incidence of stroke among Hispanic adults of all races relative to non-Hispanic White adults living within the same urban community.1 Identifying modifiable risk factors for stroke may help mitigate the disproportionate burden of stroke on Black and Hispanic adults in the US.

According to the American Heart Association, nightly sleep duration is 1 of 8 essential components for optimal cardiovascular health.2 Several studies have established associations between both self-reported short and long sleep duration and increased stroke risk.3, 4 In particular, a meta-analysis of 11 studies (n=559,252) reported a stronger association for long sleep duration and stroke risk than short sleep and stroke risk.5 These findings are also supported by other meta-analyses.6, 7 However, the vascular pathways and subclinical measures that precede stroke are not fully understood. More so, there is little data on the relationship between sleep and subclinical measures of cerebrovascular disease in aging ethnically and racially diverse cohorts. In the aging and multi-ethnic NOMAS cohort, we previously observed associations between long sleep duration and increased white matter hyperintensity volumes, a known predictor of stroke.8, 9

Carotid atherosclerosis, including carotid plaque, has been associated with white matter hyperintensities and has predicted stroke in prior NOMAS analyses and in other studies.10–12 An estimated 21% of the world population has carotid plaque.13 Carotid atherosclerosis may mediate the association between sleep duration and stroke risk. As such, examining the association between sleep duration and carotid atherosclerosis may support the establishment of sleep duration as a risk factor for subclinical carotid atherosclerosis and stroke. As sleep is a ubiquitous and modifiable process, sleep duration may serve as a modifiable risk factor of stroke. Our primary hypothesis is that self-reported short and long sleep duration would be associated with greater carotid atherosclerosis and carotid plaque burden.

METHODS

Northern Manhattan Study

Northern Manhattan is an area of New York City bordered by 218th Street to the north, 145th Street to the south, the Hudson River to the west, and the Harlem River to the east. According to the 1990 US Census, approximately 260,000 people lived in Northern Manhattan, of which 63% identified as Hispanic, 20% identified as non-Hispanic Black, and 15% identified as non-Hispanic White.14 NOMAS is a longitudinal observational study of community-dwelling adults from this racially and ethnically diverse Northern Manhattan urban community. NOMAS was designed to study the incidence and risk factors for stroke. Between 1993 and 2001, NOMAS enrolled 3,298 participants, using random digit dialing and dual frame sampling as previously described.15 Inclusion criteria were (1) age ≥39 years, (2) no prior history of stroke, and (3) had resided in the Northern Manhattan area for ≥3 months with a telephone. The overall response rate was 68%. This study was approved by the Columbia University Medical Center and University of Miami Institutional Review Boards. Participants were followed longitudinally. Written consent was provided by each participant at enrollment. Written consent was provided by each participant at enrollment. The data that support the findings of this study are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Analytic Sample

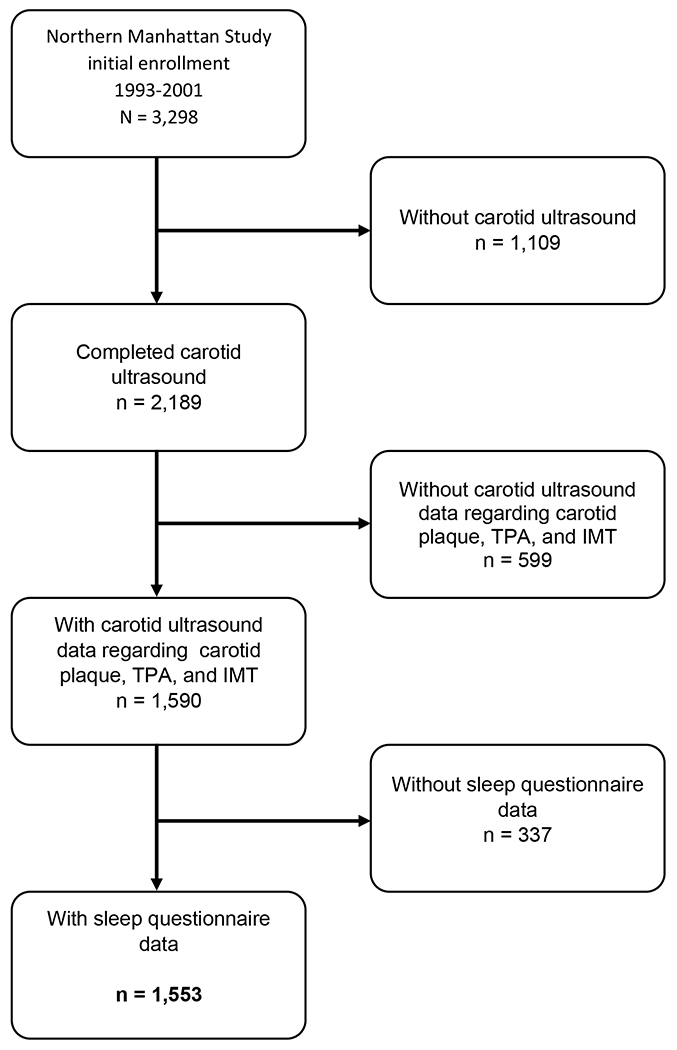

This study is a cross-sectional analysis of NOMAS participants with self-reported sleep data and carotid ultrasound evaluations. Carotid ultrasound measures of interest were carotid plaque presence, total plaque area (TPA), and intima-media thickness (IMT). Sleep data of interest were self-reported sleep duration (primary exposure) and daytime sleepiness (secondary exposure). Of the 3,298 participants enrolled in NOMAS, 2,189 underwent carotid ultrasound, and 2,153 were administered sleep questionnaires. Of those that underwent carotid ultrasound, 1,590 had data regarding carotid IMT, plaque presence, and TPA. Among those 1,590 with carotid ultrasound outcomes of interest, 1,553 also self-reported sleep duration and daytime sleepiness in their sleep questionnaires (Figure 1). This manuscript follows the STROBE reporting guideline.16

Figure 1.

Flow diagram of analytical sample.

Covariate Data

Data regarding demographics (age, self-reported sex, self-reported race-ethnicity), socioeconomic resources (educational attainment and health insurance status), behavioral vascular risk factors (smoking, alcohol use, and physical activity), and medical history (hypertension, diabetes mellitus, hypercholesterolemia, and cardiac disease) were collected through in-person interviews conducted by trained bilingual (English and Spanish) research assistants at study entry. Standardized questions were adapted from the Behavioral Risk Factor Surveillance System by the Centers for Disease Control regarding hypertension, diabetes mellitus, smoking, and cardiac conditions.17 Race and ethnicity were based on participant self-identification using questions modeled after the US Census and conforming to standard definitions outlined by Directive 15.18 Physical examinations were conducted by physicians affiliated with the study. Methods regarding the measurement of blood pressure, collection of fasting blood specimens for glucose and lipids, and the definitions of vascular risk factors in NOMAS have been described previously.19–22

Age was defined at the time of sleep data collection. Sex (female and male), race (e.g., Black, White), and ethnicity (e.g., Hispanic, non-Hispanic) were defined by self-report. Education was dichotomized into those who had completed high school versus those who had not. Health insurance status was dichotomized into two mutually exclusive groups: 1) individuals who had Medicaid or no insurance and 2) all others who had private insurance, private Medicare, or Medicare only (reference group). Smoking was categorized as never, former, and current smoker. Alcohol use was dichotomized into two groups: 1) moderate alcohol use and 2) no alcohol use or alcohol use other than moderate (reference group). Moderate alcohol use was defined as current drinking of > 1 drink per month and ≤ 2 drinks per day. Physical activity was dichotomized as 1) moderate-heavy physical activity and 2) no physical activity or light physical activity within the 2 weeks before baseline enrollment, as described previously23. Body mass index (BMI, kg/m2) was assessed by physical examination. Hypertension was defined as the self-reported history of hypertension, self-reported history of anti-hypertensive use, systolic blood pressure greater than 140 mm Hg, or diastolic blood pressure greater than 90 mm Hg. Diabetes was defined as a history of diabetes mellitus, anti-diabetic medication use, or fasting blood sugar >126 mg/dl. Hypercholesterolemia was defined as a total cholesterol >200 mg/dl, self-reported history of hypercholesterolemia, or self-reported history of taking medications for hypercholesterolemia. Cardiac disease was defined as a history of angina, myocardial infarction, coronary artery disease, or valvular heart disease.

Carotid Ultrasound

High-resolution B-mode ultrasounds (General Electric LogIQ 700, 9- to 13-MHz linear-array transducer) were performed at study entry (1993-2001) and at subsequent follow-up visits (through 2008) by trained and certified sonographers as previously described.24 The presence of plaque is defined as a focal wall thickening or protrusion in the lumen >50% greater than the surrounding thickness.11 Carotid plaque area (mm2) was measured using an automated computerized edge tracking software M’Ath (Paris, France).25 TPA was defined as the sum of all plaque areas measured in any of the carotid artery segments within an individual.11 TPA was categorized into 4 groups: no plaque, smallest plaque (first tertile of TPA), medium plaque (second tertile of TPA), and largest plaque (third tertile of TPA). IMT in all carotid segments was measured in areas without plaque. IMT was calculated as a composite measure combining proximal and distal walls of the common carotid artery IMT, bifurcation IMT, and internal carotid artery IMT of both sides of the neck. IMT was expressed as the mean of the maximum measurements of the 12 carotid sites.

Sleep Data

As part of NOMAS, questions about sleep duration and daytime sleepiness were administered during annual follow-up beginning in 2004 through 2011.15 Sleep questionnaires were administered throughout the year on an ongoing basis. Self-reported sleep duration was assessed through the following question: “During the past four weeks, how many hours, on average, did you sleep each night?” Responses were noted in 30-minute increments. Consistent with American Heart Association recommendations for sleep duration2, sleep duration was grouped into short (<7 hours), intermediate (≥7and <9 hours), and long (≥9 hours) sleep duration. Daytime sleepiness was assessed using seven of the eight questions of the Epworth Sleepiness Scale (ESS)26 that were adapted for relevance to the Northern Manhattan population15. Participants were asked, on a scale of 0-3, “How often would you say you doze while: (1) sitting and reading, (2) watching television, (3) sitting inactive in a public place, (4) as a passenger in a car, train or bus, (5) sitting and talking to someone, (6) sitting quietly after lunch without alcohol, and (7) as a driver in a car while stopped for a few minutes in traffic?” We excluded the ESS question, “How often would you say you doze as a driver in a car while stopped for a few minutes in traffic?” because of the low frequency of driving in the NOMAS population. Our modified 7-question ESS had a maximum score of 21 instead of the maximum score of 24 in the complete 8-question ESS. To account for the non-applicability of the driving question and to allow for comparison of participants with incomplete ESS data, proportional ESS scores were calculated by dividing a participant’s total ESS score by the total possible points (3 × the number of applicable and non-missing questions), and then multiplying by 21. We used a score of ≥10 to define excessive daytime sleepiness.15

Statistical Analysis

First, descriptive statistics were generated to characterize the entire sample and the three sleep duration groups: short (<7 hours), intermediate (≥7 and <9 hours), and long (≥9 hours) sleep. Second, linear regression models were constructed to examine the associations between sleep measures and carotid IMT (as a continuous variable). To test our main hypothesis, linear models were created for the primary independent exposure: short and long sleep duration groups. Linear models were also created for each secondary independent exposure: sleep duration as a continuous variable and excessive daytime sleepiness as a categorical variable (with the absence of excessive daytime sleepiness as the reference). Third, logistic regression models were constructed to examine the associations of sleep duration groups with carotid plaque presence (binary logistic regression) or carotid TPA (ordinal logistic regression). To test our primary hypothesis, logistic regression models were created for the primary independent exposure: short and long sleep groups (with intermediate sleep as the reference). Logistic regression models were also created for each secondary independent exposure: sleep duration as a continuous variable and excessive daytime sleepiness as a categorical variable (with the absence of excessive daytime sleepiness as the reference). Logistic regression outcomes were either carotid plaque presence as a binary categorical variable (with plaque absence as the reference) or carotid TPA groups as an ordinal variable (carotid TPA groups were plaque absence and each of three TPA tertiles). Four covariate adjustment models were sequentially constructed for both linear and logistic regression analyses. Model 1 was unadjusted. Model 2 adjusted for age, time between carotid ultrasound and sleep data collection, sex, race/ethnicity, education, and health insurance status. Model 3 further adjusted for smoking status, alcohol use, and physical activity. Model 4 further adjusted for BMI, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, diabetes, and cardiac disease. For all analyses, p<0.05 was defined as statistically significant. Statistical analyses were performed with SAS (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC).

RESULTS

Descriptives

Descriptive statistics of the sample are presented in Table 1. The sample had a mean age of 64.7 ± 8.5 years, was 61.9% female, and had a mean BMI of 28.2 ± 4.9 kg/m2; 18.2% self-identified as non-Hispanic Black, 64.8% self-identified as Hispanic, and 17.0% self-identified as non-Hispanic White. Carotid ultrasounds in the sample were obtained from 1999 to 2008 (mean 2003 ± 2.6 years). Of the sample, 55.6% had carotid plaque. Self-reported sleep data in the sample was collected from 2006 to 2011 (mean 2008 ± 1.5 years). Of the sample, 8.1% had excessive daytime sleepiness, and mean sleep duration was 6.8 ± 1.6 hours. The sample was divided into three sleep duration groups, of which 22.3% had short sleep (<7 hours), 66.6% had intermediate sleep (≥7and <9 hours), and 11.1% had long sleep (≥9 hours). The time from carotid ultrasound to sleep data collection ranged from 12 to −1.3 years (mean 5.2 ± 2.8 years). Descriptive statistics of the sample stratified by sleep duration groups are presented in Table 2. Short sleepers less often reported currently smoking, less often were diabetic, and more often were obese. Intermediate sleepers less often had hypertension. Long sleepers less often had completed at least high school, less often reported moderate alcohol use, more often were diabetic, and more often had a history of cardiac disease.

Table 1.

Demographics, Vascular Risk Factors, Sleep Data, and Carotid Ultrasound Data for the Study Sample

| N=1553 | n (%) |

|---|---|

| Demographic Factors | |

| Age, mean ± SD in years | 65 ± 9 |

| BMI, mean ± SD in kg/m2 ** | 28.2 ± 4.9 |

| Women | 962 (62) |

| High school education | 705 (45) |

| Medicaid or no insurance*** | 739 (48) |

| Race-Ethnicity | |

| Non-Hispanic Black | 282 (18) |

| Hispanic (of any race) | 1007 (65) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 264 (17) |

| Vascular Risk factors | |

| Moderate alcohol | 625 (40) |

| Current smoker | 224 (14) |

| Light or no physical activity**** | 1381 (90) |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2)** | 459 (30) |

| Diabetes | 294 (19) |

| Hypertension | 1087 (70) |

| Hypercholesterolemia | 1013 (65) |

| Cardiac disease | 259 (17) |

| Self-Reported Sleep Data | |

| Short sleep (<7 hours) | 709 (46) |

| Intermediate sleep (≥7 and <9 hours) | 672 (43) |

| Long sleep (≥9 hours) | 172 (11) |

| Excessive daytime sleepiness | 102 (8) |

| Carotid Ultrasound ***** | |

| Carotid IMT, mean ± SD in mm | 0.92 (0.09) |

| Carotid plaque presence | 864 (56) |

| Carotid TPA, mean ± SD in mm2 | 20.34 ± 20.67 |

| Smallest TPA | 300 (20) |

| Medium TPA | 288 (19) |

| Largest TPA | 274 (17) |

| Time from ultrasound to sleep data collection, mean ± SD in years | 5.2 ± 2.8 |

Age at time of collection of sleep data.

BMI data not available for 2 participants.

Health insurance status not available for 3 participants.

Physical activity data not available for 19 participants.

Carotid IMT data available for all 1,553 participants in the study sample. Of the 864 participants with carotid plaque, 2 participants did not have data for carotid TPA.

TPA = total plaque area. BMI = body mass index.

Table 2.

Descriptive Covariates per Sleep Duration Group

| Short Sleep (<7 hours) | Intermediate Sleep (≥7 & <9 hours) | Long Sleep (≥9 hours) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| n (%) | n (%) | n (%) | |

| Demographic Factors | |||

| n | 709 | 672 | 172 |

| Age, mean ± SD in years* | 74 ± 9 | 73 ± 9 | 77 ± 9 |

| Women | 270 (38) | 252 (38) | 69 (40) |

| High school education | 327 (46) | 305 (45) | 73 (42) |

| Medicaid or no insurance** | 330 (47) | 318 (47) | 91 (53) |

| Race-Ethnicity | |||

| Non-Hispanic Black | 143 (20) | 113 (17) | 26 (15) |

| Hispanic (of any race) | 448 (63) | 440 (65) | 119 (69) |

| Non-Hispanic White | 118 (17) | 119 (18) | 27 (16) |

| Vascular Risk factors | |||

| Moderate alcohol use | 284 (40) | 280 (42) | 61 (35) |

| Current smoking | 92 (13) | 104 (15) | 28 (16) |

| Light or no physical activity*** | 636 (91) | 588 (89) | 157 (92) |

| Obesity (BMI ≥30 kg/m2)**** | 225 (32) | 178 (27) | 49 (28) |

| Diabetes | 112 (16) | 138 (21) | 44 (26) |

| Hypertension | 507 (72) | 456 (68) | 124 (72) |

| Cardiac disease | 110 (16) | 102 (15) | 47 (27) |

| Carotid Ultrasound | |||

| Plaque presence | 377 (53) | 367 (55) | 120 (70) |

| Time from ultrasound to sleep data collection, mean ± SD in years | 5.2 (2.8) | 5.1 (2.8) | 5.1 (2.8) |

Age at time of collection of sleep data.

Health insurance status missing for 2 participants in the short sleep group and 1 participant in the long sleep group.

Physical activity not available for 7 participants in the short sleep group, 10 participants in the intermediate sleep group, and 2 participants in the long sleep group.

BMI data not available for 2 participants in the long sleep group. BMI = body mass index.

Our sample had a mean carotid IMT of 0.92±0.09 mm2 (Table 1). In those with carotid plaque, the mean TPA was 20.34 mm2 ± 20.67 mm2, with a range of 1.31 mm2 to 168.80 mm2 (Table 1). Participants with carotid plaque area were categorized into tertiles, of which 20% were in the tertile with smallest TPA (1.31-9.21mm2), 19% were in the tertile with medium TPA (9.24-21.59mm2), and 17% were in the tertile with largest TPA (21.60-168.80mm2) (Table 1). Two participants with carotid plaque did not have TPA data.

Primary Hypothesis

In binary logistic regression models of sleep duration groups (with intermediate sleep as the reference) and carotid plaque presence, only the long sleep group was significantly associated with greater odds of carotid plaque presence relative to plaque absence after full covariate adjustments (Table 3). The odds ratio (OR) of carotid plaque presence in the long sleep group decreased from 1.9 in the unadjusted model to 1.6 in the fully adjusted model. In ordinal logistic regression models of sleep duration groups (with intermediate sleep as the reference) and carotid TPA groups, only the long sleep group was associated with greater odds of larger TPA after full covariate adjustment. The OR of larger TPA in the long sleep group decreased from 1.7 in the unadjusted model to 1.4 in the fully adjusted model. Of note, proportional odds assumptions were met for all ordinal logistic regression models. In linear models of sleep duration groups and carotid IMT, sleep duration groups were not significantly associated with carotid IMT (Table 4).

Table 3.

Associations of Sleep Measures with Carotid Plaque Measures

| Plaque Presence | Total Plaque Area | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| odds ratio (95% confidence interval) | |||

| Sleep Duration (groups) | |||

| Short (<7 hours) | 1.0 (0.8-1.2) | 0.9 (0.7-1.1) | |

| Intermediate (reference) | --- | --- | |

| Long (≥9 hours) | 1.6 (1.1-2.4)* | 1.4 (1.0-1.9)* | |

| Sleep Duration (continuous) | |||

| Sleep duration, per hour | 1.1 (1.0-1.1)* | 1.1 (1.0-1.2)** | |

| Daytime Sleepiness (groups) | |||

| Less than excessive (reference) | --- | --- | |

| Excessive | 1.0 (0.6-1.5) | 1.0 (0.7-1.5) | |

Logistic regression models were adjusted for age at collection of sleep data, years between carotid ultrasound and collection of sleep data, sex, education, race-ethnicity, health insurance status, alcohol use, physical activity, body mass index, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia, and cardiac disease (full adjustment). Logistic regression models used either plaque presence as a binary outcome variable (relative to plaque absence) or carotid total plaque area groups as an ordinal outcome variable. The odds ratios presented for sleep duration as a continuous variable are per hour of sleep.

p<0.05;

p<0.01.

Table 4.

Associations of Sleep Measures with Carotid IMT

| Carotid IMT | ||

|---|---|---|

| β (SE) | p | |

| Sleep Duration (groups) | ||

| Short (<7 hours) | 0.004 (0.004) | 0.31 |

| Intermediate (reference) | --- | --- |

| Long (≥9 hours) | 0.005 (0.007) | 0.49 |

| Sleep Duration (continuous) | ||

| Sleep, per hour | −0.001 (0.001) | 0.65 |

| Daytime Sleepiness | ||

| Less than excessive (reference) | --- | --- |

| Excessive | 0.003 (0.008) | 0.65 |

Linear models were adjusted for age at collection of sleep data, years between carotid ultrasound and collection of sleep data, sex, education, race-ethnicity, health insurance status, alcohol use, physical activity, body mass index, smoking, diabetes, hypertension, hypercholesterolemia and cardiac disease (full adjustment). The β’s for sleep duration as a continuous variable are per hour of sleep. IMT = intima media thickness.

Post Hoc Analyses

In binary logistic regression models of sleep duration as a continuous variable and carotid plaque presence, the association between longer sleep and greater odds of carotid plaque presence was significant after full covariate adjustment (Table 3). The OR per hour of sleep for plaque presence was 1.1 in both unadjusted and fully adjusted models. In ordinal logistic regression models of sleep duration as a continuous variable and carotid TPA groups, longer sleep duration was associated with greater odds of larger TPA after full covariate adjustment. The OR per hour of sleep for larger plaque TPA was 1.1 in both unadjusted and fully adjusted models. In linear models of sleep duration as a continuous variable and carotid IMT, sleep duration was not significantly associated with carotid IMT (Table 4).

Logistic regression models found no significant associations of excessive daytime sleepiness with carotid plaque presence (relative to plaque absence) or carotid TPA groups (Table 3). Linear models found no significant association between excessive daytime sleepiness and carotid IMT (Table 4).

Supplemental tables (Tables S1–S3) present the results of all unadjusted and partially adjusted linear and logistic regression models.

DISCUSSION

In this racially and ethnically diverse sample of 1,553 community-dwelling adults from NOMAS, long sleep (compared to intermediate sleep duration) was associated with greater odds of carotid plaque presence relative to carotid plaque absence. Long sleep was also associated with greater odds of larger carotid TPA. Notably, short sleep was not associated with carotid plaque presence or TPA; sleep duration was not associated with carotid IMT; and daytime sleepiness was not associated with carotid plaque presence, TPA, or IMT. The association between sleep duration and carotid atherosclerotic plaque burden carries clinical implications. As sleep is modifiable, sleep may serve as a target for interventions that could mitigate carotid atherosclerosis.

Long Sleep and Carotid Atherosclerotic Burden in Context

Compared to the few studies that have reported associations between long sleep and carotid atherosclerotic burden, the racial and ethnic distributions of our sample were more diverse (18% Non-Hispanic Black, 65% Hispanic). Our results are consistent with three studies that demonstrated cross-sectional associations between long sleep and greater carotid IMT in community-dwelling adults in Pomerania (Germany)27, adult community clinic patients in Niigata (Japan)28, and police officers in Buffalo (New York, US)29. Unlike these three prior studies, our study demonstrated an association of long sleep with greater odds of carotid plaque presence and greater TPA. Our observed associations of sleep duration with carotid plaque presence and carotid TPA may have greater clinical relevance than prior studies that used carotid IMT as an outcome. A meta-analysis of 11 population-based studies (n=54,336 patients) demonstrated that carotid plaque presence is a more accurate predictor of future myocardial infarction than carotid IMT (area under the curve 0.64 vs. 0.61, relative diagnostic odds ratio 1.35; 95%CI 1.03-1.82, p <0.05).30 Similarly, a 5-year longitudinal study from Ontario, Canada demonstrated that carotid TPA was a better predictor of incident stroke, transient ischemic attack, and vascular death than carotid IMT.31

Short Sleep and Carotid Atherosclerotic Burden in Context

Although our study did not find any association between short sleep and carotid plaque presence or TPA, prior observational studies have reported associations between shorter sleep and greater carotid atherosclerotic burden. Short sleep was associated with greater carotid IMT among middle-aged adults in the US (multiple sites)32, older adults in Chūbu (Japan)33, and community-dwelling adults in Pomerania (Germany)27. Short sleep was associated with greater carotid plaque presence in adults 40 years or older in Beijing (China)34 and perimenopausal and postmenopausal women in Pittsburgh (Pennsylvania, US)35. These prior studies methodologically differed from our study in three ways that can contribute to the discrepant findings. First, these prior studies categorized sleep duration as <5 hours27, 33–35. Second, these prior studies differed in their references for comparison. Short sleep was either compared to all other sleep duration groups (i.e., sleep duration ≥5 hours)34, to sleep duration >7 hours33, 35, or to sleep duration of only 8 hours27. Our study defined short sleep as <7 hours and compared short sleep to intermediate sleep duration (≥7 hours and <9 hours). Third, these prior studies either used actigraphy to measure sleep during the main rest period (i.e., overnight sleep)32, 33, 35 or calculated total self-reported sleep duration in a 24-hour period, which included naps outside the main rest period27, 34. Our study measured self-reported sleep duration only in the main rest period and did not account for nap frequency or duration. Of note, nap frequency has been associated with increased risk of stroke36, and further study is needed to identify the mechanisms associating naps with stroke risk.

Potential Pathways Between Sleep Duration and Carotid Atherosclerosis

Long sleep has been associated with metabolic derangements, inflammatory markers, and behavioral risk factors implicated in cardiovascular disease, any of which could mediate a relationship between long sleep and carotid plaque burden. Short and long sleep have been associated with metabolic syndrome37, 38, which predicted incident cardiovascular events in a prior NOMAS analysis39. Features of metabolic syndrome specifically associated with long sleep include hypertriglyceridemia37, low levels of high-density lipoproteins38, 40, hyperglycemia37, insulin resistance41, and obesity42. Long sleep has been associated with inflammatory markers, including interleuken-6 (IL-6)43 and C-reactive protein (CRP)40, 43, which in turn have also been associated with cardiovascular disease44. Long sleep has also been associated with behavioral risk factors implicated in carotid atherosclerosis45–48, including insufficient physical activity49, 50, smoking40, and increased alcohol consumption40. Of note, NOMAS has no direct measure of sleep disordered breathing, another potential contributor to sleep duration and carotid atherosclerotic burden. Although long sleep has been associated with metabolic derangements, obesity, immune mediated inflammation, and behavioral risk factors, it is unclear whether these associations are causal.51

Strengths

Relative to prior studies that evaluated the associations between sleep duration and carotid atherosclerosis, our study sample is diverse in composition of race and ethnicity. A racially and ethnically diverse sample enhances the generalizability of our results. Our large sample size also allowed for ample covariate adjustment, which substantiates the independence of associations between long sleep and carotid plaque burden. Relative to prior studies that defined short sleep as <5 hours, our study’s categorization of sleep duration as short (<7 hours), intermediate (≥7and <9 hours), and long (≥9 hours) are more consistent with consensus recommendations. The American Heart Association, American Academy of Sleep Medicine, and Sleep Research Society describe optimal sleep duration as 7 to 9 hours, while sleeping less than 7 hours is associated with adverse health outcomes, and sleeping more than 9 hours has been equivocally associated with health risk52. Last, although prior studies reported associations between long sleep and carotid IMT, our study found associations between long sleep and carotid plaque presence and carotid TPA. In spite of the observed associations of common carotid IMT with greater odds of lacunar stroke, greater ischemic stroke severity, and greater risk of ischemic stroke recurrence53–55, carotid plaque presence and TPA have been more predictive of cardiovascular outcomes than carotid IMT.30, 31 Established cardiovascular risk factors (i.e., total cholesterol, systolic blood pressure, and smoking) have also been more closely associated with carotid TPA than with IMT.56 As such, the association between long sleep and greater carotid plaque burden demonstrated in our study expands the clinical relevance of prior work that examined sleep duration and carotid atherosclerosis.

Limitations

Our results have limitations inherent to secondary analyses of observational epidemiological studies. First, our analyses are cross-sectional and cannot be used to infer the directionality or causality of any relationship between sleep duration and carotid atherosclerosis. Second, this study did not obtain polysomnography or actigraphy, which objectively measure sleep and physical activity, respectively. Self-reported sleep duration is an incomplete approximation of sleep that does not characterize the multiple dimensions of sleep, such as sleep microstructure or sleep continuity. Similarly, self-reported physical activity is only an approximation of physical activity, which can be measured objectively with actigraphy. Third, analyses did not adjust for sleep disordered breathing, making it difficult to parse whether the association between long sleep and carotid plaque was independent of sleep disordered breathing. Fourth, our study did not use MRI to identify neuroanatomical variations and abnormalities that can influence sleep, such as pineal gland cysts. Fifth, our analyses did not adjust for the use of hypnotic medications, which can affect sleep duration. Our analyses also did not adjust for adherence to pharmacotherapy that can mitigate atherosclerosis, such as anti-platelet medications or blood lipid lowering agents.

Conclusion

Our study of ethnically and racially diverse community-dwelling adults in a Northern Manhattan urban community demonstrated associations of long sleep duration with greater odds of plaque presence and greater carotid TPA. Further research is needed to identify the potential mechanisms that mediate associations between long sleep and carotid atherosclerosis. As sleep is a ubiquitous and modifiable process, modifying sleep may help mitigate carotid atherosclerosis. As sleep varies by race and ethnicity57, sleep may serve as a target for intervention that helps reduce the disproportionate burden of stroke on non-Hispanic Black and Hispanic adults.

Supplementary Material

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

This manuscript is published posthumously for Ralph L. Sacco, MD, MS, FAAN, FAHA. Dr. Sacco served as president of both the American Heart Association and the American Academy of Neurology and was the editor-in-chief of Stroke. As faculty at Columbia University, he founded the Northern Manhattan Study. At the University of Miami Miller School of Medicine, he was professor of neurology, public health sciences, human genetics, and neurosurgery, the executive director of the Evelyn F. McKnight Brain Institute, and the Olemberg Family Chair in Neurologic Disorders. He served in various academic and clinical roles, received numerous awards, and published more than 1,000 peer-reviewed articles. Dr. Sacco mentored and continues to inspire generations of clinicians and scientists. He is remembered with profound and enduring gratitude.

FUNDING SOURCES

This work was supported by the National Institutes of Health through grants from the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (R37 NS029993, PI: Sacco/Elkind) and the National Institute on Aging (R01 AG067568, PI: Ramos), and by The Evelyn F. McKnight Brain Institute.

DISCLOSURES

Dr. Elkind has received royalties from UpToDate for chapters on stroke; study drug in kind from the BMS-Pfizer Alliance for Eliquis® and ancillary research funding from Roche, both for a federally funded trial of stroke prevention; and is currently employed by the American Heart Association as Chief Clinical Science Officer. Drs. Agudelo, Ramos, Gardener, Cheung, Sacco, and Rundek had no disclosures related to this work.

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms:

- NOMAS

Northern Manhattan Study

- OR

odds ratio

- CI

confidence interval

- US

United States of America

- TPA

total plaque area

- IMT

intima-media thickness

- BMI

body mass index

- kg/m2

kilograms per square meter

- mm Hg

millimeters of mercury

- mg/dl

milligrams per deciliter

- ESS

Epworth Sleepiness Scale

REFERENCES

- 1.Sacco RL, Boden-Albala B, Gan R, Chen X, Kargman DE, Shea S, Paik MC, Hauser WA. Stroke incidence among white, black, and hispanic residents of an urban community: The northern manhattan stroke study. Am J Epidemiol. 1998;147:259–268 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lloyd-Jones DM, Allen NB, Anderson CAM, Black T, Brewer LC, Foraker RE, Grandner MA, Lavretsky H, Perak AM, Sharma G, et al. Life’s essential 8: Updating and enhancing the american heart association’s construct of cardiovascular health: A presidential advisory from the american heart association. Circulation. 2022;146:e18–e43 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Yin J, Jin X, Shan Z, Li S, Huang H, Li P, Peng X, Peng Z, Yu K, Bao W, et al. Relationship of sleep duration with all-cause mortality and cardiovascular events: A systematic review and dose-response meta-analysis of prospective cohort studies. J Am Heart Assoc. 2017;6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Akinseye OA, Ojike NI, Akinseye LI, Dhandapany PS, Pandi-Perumal SR. Association of sleep duration with stroke in diabetic patients: Analysis of the national health interview survey. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2016;25:650–655 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Leng Y, Cappuccio FP, Wainwright NW, Surtees PG, Luben R, Brayne C, Khaw KT. Sleep duration and risk of fatal and nonfatal stroke: A prospective study and meta-analysis. Neurology. 2015;84:1072–1079 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Itani O, Jike M, Watanabe N, Kaneita Y. Short sleep duration and health outcomes: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and meta-regression. Sleep Med. 2017;32:246–256 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Jike M, Itani O, Watanabe N, Buysse DJ, Kaneita Y. Long sleep duration and health outcomes: A systematic review, meta-analysis and meta-regression. Sleep Med Rev. 2018;39:25–36 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ramos AR, Dong C, Rundek T, Elkind MS, Boden-Albala B, Sacco RL, Wright CB. Sleep duration is associated with white matter hyperintensity volume in older adults: The northern manhattan study. J Sleep Res. 2014;23:524–530 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ramos AR, Dib SI, Wright CB. Vascular dementia. Curr Transl Geriatr Exp Gerontol Rep. 2013;2:188–195 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Touboul PJ, Hennerici MG, Meairs S, Adams H, Amarenco P, Bornstein N, Csiba L, Desvarieux M, Ebrahim S, Hernandez Hernandez R, et al. Mannheim carotid intima-media thickness and plaque consensus (2004–2006-2011). An update on behalf of the advisory board of the 3rd, 4th and 5th watching the risk symposia, at the 13th, 15th and 20th european stroke conferences, mannheim, germany, 2004, brussels, belgium, 2006, and hamburg, germany, 2011. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2012;34:290–296 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kuo F, Gardener H, Dong C, Cabral D, Della-Morte D, Blanton SH, Elkind MS, Sacco RL, Rundek T. Traditional cardiovascular risk factors explain the minority of the variability in carotid plaque. Stroke. 2012;43:1755–1760 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Rundek T, Arif H, Boden-Albala B, Elkind MS, Paik MC, Sacco RL. Carotid plaque, a subclinical precursor of vascular events: The northern manhattan study. Neurology. 2008;70:1200–1207 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Song P, Fang Z, Wang H, Cai Y, Rahimi K, Zhu Y, Fowkes FGR, Fowkes FJI, Rudan I. Global and regional prevalence, burden, and risk factors for carotid atherosclerosis: A systematic review, meta-analysis, and modelling study. Lancet Glob Health. 2020;8:e721–e729 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sacco RL, Kargman DE, Gu Q, Zamanillo MC. Race-ethnicity and determinants of intracranial atherosclerotic cerebral infarction. The northern manhattan stroke study. Stroke. 1995;26:14–20 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Boden-Albala B, Roberts ET, Bazil C, Moon Y, Elkind MS, Rundek T, Paik MC, Sacco RL. Daytime sleepiness and risk of stroke and vascular disease: Findings from the northern manhattan study (nomas). Circulation. Cardiovascular quality and outcomes. 2012;5:500–507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Vandenbroucke JP, von Elm E, Altman DG, Gotzsche PC, Mulrow CD, Pocock SJ, Poole C, Schlesselman JJ, Egger M, Initiative S. Strengthening the reporting of observational studies in epidemiology (strobe): Explanation and elaboration. PLoS Med. 2007;4:e297. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Gentry EM, Kalsbeek WD, Hogelin GC, Jones JT, Gaines KL, Forman MR, Marks JS, Trowbridge FL. The behavioral risk factor surveys: Ii. Design, methods, and estimates from combined state data. Am J Prev Med. 1985;1:9–14 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Management Oo, Budget. Race and ethnic standards for federal statistics and administrative reporting. Statistical Policy Directive 15. 1977 [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sacco RL, Boden-Albala B, Abel G, Lin IF, Elkind M, Hauser WA, Paik MC, Shea S. Race-ethnic disparities in the impact of stroke risk factors: The northern manhattan stroke study. Stroke. 2001;32:1725–1731 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gardener H, Sacco RL, Rundek T, Battistella V, Cheung YK, Elkind MSV. Race and ethnic disparities in stroke incidence in the northern manhattan study. Stroke. 2020;51:1064–1069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Boden-Albala B, Cammack S, Chong J, Wang C, Wright C, Rundek T, Elkind MS, Paik MC, Sacco RL. Diabetes, fasting glucose levels, and risk of ischemic stroke and vascular events: Findings from the northern manhattan study (nomas). Diabetes Care. 2008;31:1132–1137 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Willey JZ, Paik MC, Sacco R, Elkind MS, Boden-Albala B. Social determinants of physical inactivity in the northern manhattan study (nomas). J Community Health. 2010;35:602–608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Willey JZ, Gardener H, Caunca MR, Moon YP, Dong C, Cheung YK, Sacco RL, Elkind MS, Wright CB. Leisure-time physical activity associates with cognitive decline: The northern manhattan study. Neurology. 2016;86:1897–1903 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Alsulaimani S, Gardener H, Elkind MS, Cheung K, Sacco RL, Rundek T. Elevated homocysteine and carotid plaque area and densitometry in the northern manhattan study. Stroke. 2013;44:457–461 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ferguson GG, Eliasziw M, Barr HW, Clagett GP, Barnes RW, Wallace MC, Taylor DW, Haynes RB, Finan JW, Hachinski VC, et al. The north american symptomatic carotid endarterectomy trial : Surgical results in 1415 patients. Stroke. 1999;30:1751–1758 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Johns MW. A new method for measuring daytime sleepiness: The epworth sleepiness scale. Sleep. 1991;14:540–545 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wolff B, Volzke H, Schwahn C, Robinson D, Kessler C, John U. Relation of self-reported sleep duration with carotid intima-media thickness in a general population sample. Atherosclerosis. 2008;196:727–732 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Abe T, Aoki T, Yata S, Okada M. Sleep duration is significantly associated with carotid artery atherosclerosis incidence in a japanese population. Atherosclerosis. 2011;217:509–513 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Ma CC, Burchfiel CM, Charles LE, Dorn JM, Andrew ME, Gu JK, Joseph PN, Fekedulegn D, Slaven JE, Hartley TA, et al. Associations of objectively measured and self-reported sleep duration with carotid artery intima media thickness among police officers. Am J Ind Med. 2013;56:1341–1351 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Inaba Y, Chen JA, Bergmann SR. Carotid plaque, compared with carotid intima-media thickness, more accurately predicts coronary artery disease events: A meta-analysis. Atherosclerosis. 2012;220:128–133 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Wannarong T, Parraga G, Buchanan D, Fenster A, House AA, Hackam DG, Spence JD. Progression of carotid plaque volume predicts cardiovascular events. Stroke. 2013;44:1859–1865 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sands MR, Lauderdale DS, Liu K, Knutson KL, Matthews KA, Eaton CB, Linkletter CD, Loucks EB. Short sleep duration is associated with carotid intima-media thickness among men in the coronary artery risk development in young adults (cardia) study. Stroke. 2012;43:2858–2864 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nakazaki C, Noda A, Koike Y, Yamada S, Murohara T, Ozaki N. Association of insomnia and short sleep duration with atherosclerosis risk in the elderly. Am J Hypertens. 2012;25:1149–1155 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chen S, Yang Y, Cheng GL, Jia J, Fan FF, Li JP, Huo Y, Zhang Y, Chen DF. Association between short sleep duration and carotid atherosclerosis modified by age in a chinese community population. J Epidemiol Community Health. 2018;72:539–544 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Thurston RC, Chang Y, von Kanel R, Barinas-Mitchell E, Jennings JR, Hall MH, Santoro N, Buysse DJ, Matthews KA. Sleep characteristics and carotid atherosclerosis among midlife women. Sleep. 2017;40 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Yang MJ, Zhang Z, Wang YJ, Li JC, Guo QL, Chen X, Wang E. Association of nap frequency with hypertension or ischemic stroke supported by prospective cohort data and mendelian randomization in predominantly middle-aged european subjects. Hypertension. 2022;79:1962–1970 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Choi KM, Lee JS, Park HS, Baik SH, Choi DS, Kim SM. Relationship between sleep duration and the metabolic syndrome: Korean national health and nutrition survey 2001. Int J Obes (Lond). 2008;32:1091–1097 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hall MH, Muldoon MF, Jennings JR, Buysse DJ, Flory JD, Manuck SB. Self-reported sleep duration is associated with the metabolic syndrome in midlife adults. Sleep. 2008;31:635–643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Suzuki T, Hirata K, Elkind MS, Jin Z, Rundek T, Miyake Y, Boden-Albala B, Di Tullio MR, Sacco R, Homma S. Metabolic syndrome, endothelial dysfunction, and risk of cardiovascular events: The northern manhattan study (nomas). Am Heart J. 2008;156:405–410 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Williams CJ, Hu FB, Patel SR, Mantzoros CS. Sleep duration and snoring in relation to biomarkers of cardiovascular disease risk among women with type 2 diabetes. Diabetes Care. 2007;30:1233–1240 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Pyykkonen AJ, Isomaa B, Pesonen AK, Eriksson JG, Groop L, Tuomi T, Raikkonen K. Sleep duration and insulin resistance in individuals without type 2 diabetes: The ppp-botnia study. Ann Med. 2014;46:324–329 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Brady EM, Bodicoat DH, Hall AP, Khunti K, Yates T, Edwardson C, Davies MJ. Sleep duration, obesity and insulin resistance in a multi-ethnic uk population at high risk of diabetes. Diabetes Res Clin Pract. 2018;139:195–202 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Patel SR, Zhu X, Storfer-Isser A, Mehra R, Jenny NS, Tracy R, Redline S. Sleep duration and biomarkers of inflammation. Sleep. 2009;32:200–204 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Collaboration IRGCERF, Sarwar N, Butterworth AS, Freitag DF, Gregson J, Willeit P, Gorman DN, Gao P, Saleheen D, Rendon A, et al. Interleukin-6 receptor pathways in coronary heart disease: A collaborative meta-analysis of 82 studies. Lancet. 2012;379:1205–1213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Laguzzi F, Baldassarre D, Veglia F, Strawbridge RJ, Humphries SE, Rauramaa R, Smit AJ, Giral P, Silveira A, Tremoli E, et al. Alcohol consumption in relation to carotid subclinical atherosclerosis and its progression: Results from a european longitudinal multicentre study. Eur J Nutr. 2021;60:123–134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Yang D, Iyer S, Gardener H, Della-Morte D, Crisby M, Dong C, Cheung K, Mora-McLaughlin C, Wright CB, Elkind MS, et al. Cigarette smoking and carotid plaque echodensity in the northern manhattan study. Cerebrovasc Dis. 2015;40:136–143 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mast H, Thompson JL, Lin IF, Hofmeister C, Hartmann A, Marx P, Mohr JP, Sacco RL. Cigarette smoking as a determinant of high-grade carotid artery stenosis in hispanic, black, and white patients with stroke or transient ischemic attack. Stroke. 1998;29:908–912 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Stein RA, Rockman CB, Guo Y, Adelman MA, Riles T, Hiatt WR, Berger JS. Association between physical activity and peripheral artery disease and carotid artery stenosis in a self-referred population of 3 million adults. Arterioscler Thromb Vasc Biol. 2015;35:206–212 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Stranges S, Dorn JM, Shipley MJ, Kandala NB, Trevisan M, Miller MA, Donahue RP, Hovey KM, Ferrie JE, Marmot MG, et al. Correlates of short and long sleep duration: A cross-cultural comparison between the united kingdom and the united states: The whitehall ii study and the western new york health study. Am J Epidemiol. 2008;168:1353–1364 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Krueger PM, Friedman EM. Sleep duration in the united states: A cross-sectional population-based study. Am J Epidemiol. 2009;169:1052–1063 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Grandner MA, Drummond SP. Who are the long sleepers? Towards an understanding of the mortality relationship. Sleep Med Rev. 2007;11:341–360 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Watson NF, Badr MS, Belenky G, Bliwise DL, Buxton OM, Buysse D, Dinges DF, Gangwisch J, Grandner MA, Kushida C, et al. Recommended amount of sleep for a healthy adult: A joint consensus statement of the american academy of sleep medicine and sleep research society. Sleep. 2015;38:843–844 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Tsivgoulis G, Vemmos KN, Spengos K, Papamichael CM, Cimboneriu A, Zis V, Zakopoulos N, Mavrikakis M. Common carotid artery intima-media thickness for the risk assessment of lacunar infarction versus intracerebral haemorrhage. J Neurol. 2005;252:1093–1100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Tsivgoulis G, Vemmos K, Papamichael C, Spengos K, Manios E, Stamatelopoulos K, Vassilopoulos D, Zakopoulos N. Common carotid artery intima-media thickness and the risk of stroke recurrence. Stroke. 2006;37:1913–1916 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Heliopoulos I, Papaoiakim M, Tsivgoulis G, Chatzintounas T, Vadikolias K, Papanas N, Piperidou C. Common carotid intima media thickness as a marker of clinical severity in patients with symptomatic extracranial carotid artery stenosis. Clin Neurol Neurosurg. 2009;111:246–250 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Herder M, Johnsen SH, Arntzen KA, Mathiesen EB. Risk factors for progression of carotid intima-media thickness and total plaque area: A 13-year follow-up study: The tromso study. Stroke. 2012;43:1818–1823 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Grandner MA, Williams NJ, Knutson KL, Roberts D, Jean-Louis G. Sleep disparity, race/ethnicity, and socioeconomic position. Sleep Med. 2016;18:7–18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.