Abstract

Background:

Understanding heterogeneity across patients in effectiveness of network-based HIV testing interventions may optimize testing and contact tracing strategies, expediting linkage to therapy or prevention for contacts of persons with HIV (PWH).

Setting:

We analyzed data from a randomized controlled trial of a combination intervention comprising acute HIV testing, contract partner notification (cPN), and social contact referral conducted among PWH at two STI clinics in Lilongwe, Malawi, between 2015 and 2019.

Methods:

We used binomial regression to estimate the effect of the combination intervention vs. passive PN (pPN) on having any: 1) contact, 2) newly HIV-diagnosed contact, and 3) HIV-negative contact present to the clinic, overall and by referring participant characteristics. We repeated analyses comparing cPN alone with pPN.

Results:

The combination intervention effect on having any presenting contact was greater among referring women than men (Prevalence Difference (PD): 0.17 vs. 0.10) and among previously vs. newly HIV-diagnosed referring persons (PD: 0.20 vs. 0.11). Differences by sex and HIV diagnosis status were similar in cPN vs. pPN analyses. There were no notable differences in intervention effect on newly HIV-diagnosed referrals by referring participant characteristics. Intervention impact on having HIV-negative presenting contacts was greater among younger vs. older referring persons and among those with >1 vs. ≤1 recent sex partner. Effect differences by age were similar for cPN vs. pPN.

Conclusion:

Our intervention package may be particularly efficacious in eliciting referrals from women and previously diagnosed persons. When the combination intervention is infeasible, cPN alone may be beneficial for these populations.

Keywords: acute HIV infection, clinical trial, contact tracing, HIV, Malawi, partner notification

INTRODUCTION

The HIV burden in the southeastern African country of Malawi, where about 9% of adults live with HIV,1 is among the highest in the world. An estimated 88% of Malawians living with HIV are aware of their HIV status, 98% of status-aware persons are on antiretroviral therapy (ART), and 97% of those on ART are virally suppressed.1 Persons unaware of their HIV infection are at particularly high risk of onward HIV transmission,2 especially during the earliest (acute) stage of infection when the virus is rapidly multiplying.3,4 To achieve the UNAIDS objective of identifying 95% of persons with HIV (PWH),5 efficient strategies for finding undiagnosed PWH are needed, including focused efforts to identify persons with acute HIV infection (AHI) and sexual partners of recently HIV-diagnosed persons.6

Voluntary partner notification (PN), in which persons diagnosed with HIV refer their sexual partners for HIV testing services (HTS), can effectively identify previously undiagnosed PWH for linkage to HIV care and HIV-susceptible persons for HIV prevention services.7,8 Since 2016, the World Health Organization (WHO) has recommended augmenting passive PN (self-disclosure to and referral of sexual partners; pPN) with provider-assisted contact tracing as part of routine care for persons newly diagnosed with HIV.9,10 Contract PN (cPN), an assisted approach that first allows a contracted amount of time for pPN before provider intervention,11 is feasible and cost-effective in Malawi and other sub-Saharan African countries.12–17 Additionally, social contact referral for HTS effectively identifies persons unaware of their HIV infection or at risk of HIV exposure,18 given social contacts of PWH may also engage in behaviors that increase HIV acquisition risk.19

In a randomized controlled trial (RCT) among PWH at two sexually transmitted infections (STI) clinics in Malawi,20 we previously demonstrated that a combination intervention of cPN, social contact referral, and AHI screening increased the rate of new HIV diagnoses within participants’ sociosexual networks compared to pPN alone (standard of care). But cPN and the successful identification of persons with AHI require available staff and enhanced testing services, which can be resource-intensive.21 To inform the strategic allocation of scarce clinical resources for enhanced testing and PN services, we sought to determine the impact of the combination intervention versus pPN on having at least one: 1) presenting contact, 2) newly HIV-diagnosed presenting contact, and 3) HIV-negative presenting contact, both overall and according to key characteristics of referring PWH. The standard of care for partner services in Malawi during the trial was pPN, and after the trial ended in 2019, the standard HTS guidelines were updated to include cPN.22 In consideration of these updated standards, particularly for settings where the combination intervention would be infeasible, we repeated analyses for cPN alone vs. pPN.

METHODS

Study design, setting, participants, and procedures

We conducted a secondary analysis of data from the iKnow study, a two-arm RCT20 that aimed to determine the efficacy of a combination HIV detection intervention comprising AHI screening, cPN, and social network referral (vs. pPN) among persons attending two STI clinics in Lilongwe, Malawi, between 2015 and 2019.

Study eligibility and enrollment

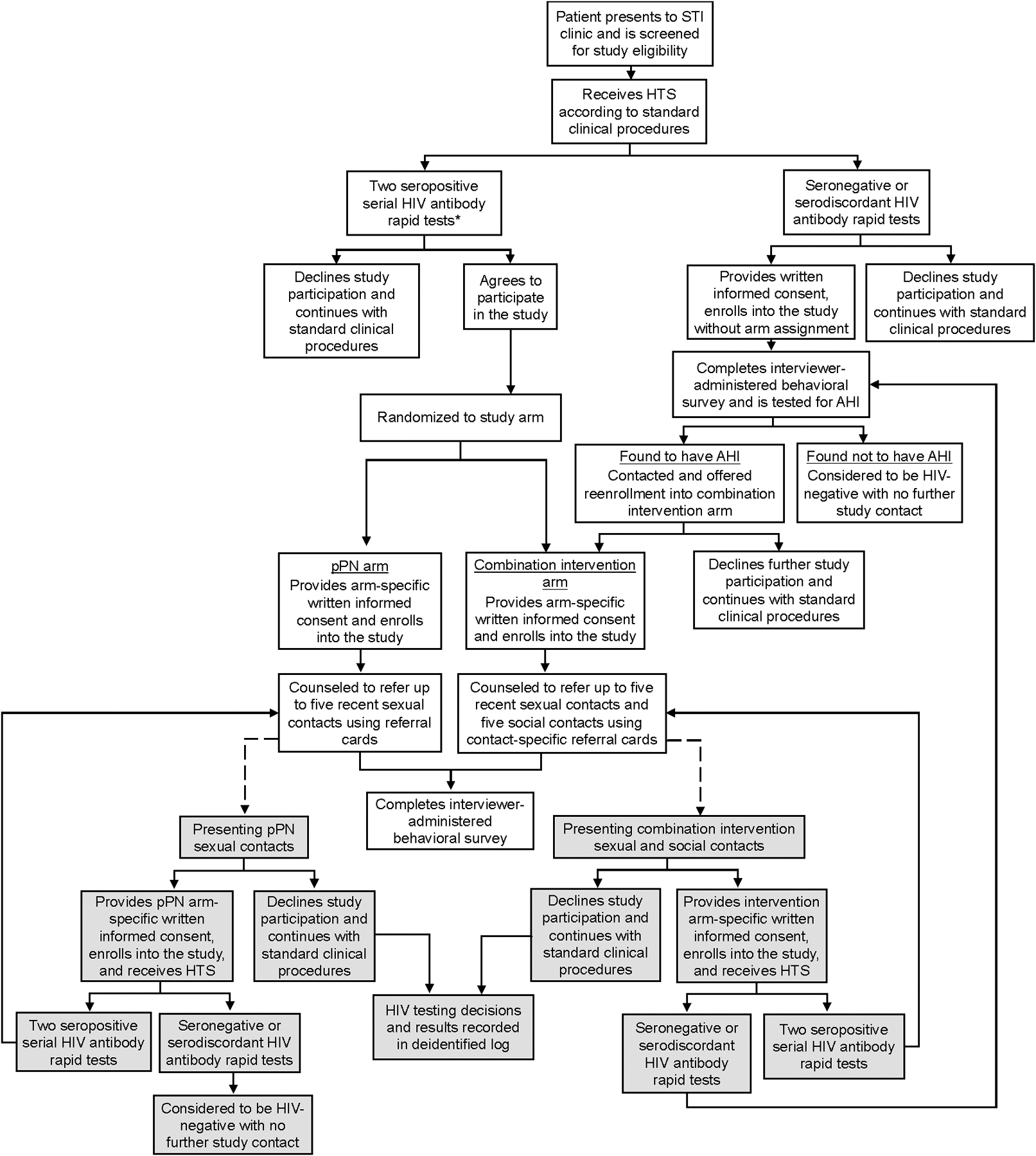

All persons presenting to the STI clinic during the study period were screened for study eligibility prior to routine opt-out HIV testing (Figure 1). Eligible participants included persons ages ≥18 years who were sexually active in the prior six months and living in the Lilongwe area. Persons who were ineligible or declined study participation received standard HIV testing (i.e., rapid HIV antibody test and pPN if seropositive) and STI services.

Figure 1. Flow chart of iKnow study procedures.

*Eligibility for index participant study procedures was expanded from enrolling only persons with a newly identified HIV infection to also include persons with a previously identified HIV infection in April 2017.

Index participants

Persons who agreed to participate in the study received HTS through standard clinical procedures. PWH were identified by serial rapid HIV antibody tests (Alere Determine HIV-1/2 and Uni-Gold Recombigen HIV-1/2): if the initial rapid test was positive, an additional test was immediately performed. If both tests were positive, PWH were randomized into one of two arms: 1) the combination intervention arm (also referred to as intervention), which included both cPN and social contact referral, or 2) the standard-of-care arm with only pPN (henceforth called pPN arm). Immediately after randomization, PWH were offered enrollment into the study as “index participants,” and among those who agreed to enroll, arm-specific informed consent was obtained (see below). Participants were randomized 3:1 (pPN:intervention) from June 2015 through March 2018, and 1:1 from April 2018 through May 2019. In April 2017, eligibility for index participant study procedures was expanded from enrolling only persons with a newly identified HIV infection to also include persons with a previously identified HIV infection. Persons reporting a prior HIV diagnosis had their HIV status confirmed with the HIV testing procedures above before enrollment.

Eligible persons with either seronegative or serodiscordant (a seropositive followed by a seronegative) HIV antibody rapid tests were offered enrollment into the AHI screening phase of the study, and following informed consent, their blood samples were pooled23,24 and tested within several days for AHI using HIV RNA polymerase chain reaction (PCR; Abbott RealTime HIV-1 assay). Those with AHI (HIV RNA >5000 copies/ml) were contacted by clinic staff and asked to return to the clinic for study follow-up and linkage to HIV care. Upon returning to the clinic, participants with AHI were offered enrollment into the intervention arm; persons without AHI did not participate further.

Participants in the intervention arm were asked to: 1) provide names and contact information for up to five sexual contacts in the previous six months; 2) refer all named sexual contacts to the clinic for HTS within seven days, after which clinic staff would attempt to contact and counsel named sexual contacts who had not presented to the clinic (i.e., through cPN); and 3) refer up to five social contacts who were not sexual contacts in the previous six months to the clinic for HTS (i.e., social contact referral). Participants in the pPN arm received counseling on PN and were asked to passively refer up to five sexual contacts from the previous six months without additional clinic assistance. All index participants were provided referral cards with their coded identification number to give to each sexual contact (both arms) or social contact (intervention arm only), with cards for sexual vs. social contacts distinguished by a color-coding system. The cards were then used to link each presenting contact to the referring index participant upon clinic presentation.

Referred sexual and social contacts

Sexual contacts who presented to the STI clinic with a linked referral card after either cPN through the intervention arm or pPN through the standard-of-care arm were screened for study eligibility and offered enrollment into the study (Figure 1). Consenting contacts who tested HIV-seropositive were automatically enrolled into the arm of the referring index participant and followed arm-specific procedures described above. Consenting HIV-seronegative or -serodiscordant sexual contacts of intervention index participants were screened for AHI, and if found to have AHI, followed index procedures; those found not to have AHI were enrolled as HIV-negative contacts with no onward contact referral. HIV-seronegative or -serodiscordant sexual contacts of pPN index participants were not screened for AHI but enrolled as HIV-negative sexual contacts with no onward contact referral.

Social contacts who presented to the STI clinic with a linked referral card were screened for study eligibility and followed the same enrollment procedures as sexual contacts of intervention participants.

All enrolled sexual and social contacts with HIV were subsequently treated as index participants according to contact referral procedures under their assigned (i.e., non-randomized) study arm. Enrolled contacts were unable to refer their initial index participant for re-enrollment. Subsequent contact enrollment and referral (i.e., chain referrals) were not limited to a specific number of waves and were able to continue through study end (May 2019).20 We retained a deidentified referral log of referral type (social vs. sexual), referring participant ID, HIV testing decisions (tested vs. not tested), and HIV test results for sexual partners and social contacts who refused study enrollment.

Data collection

All enrolled participants self-reported demographic, sexual behavior, and clinical characteristics through an interviewer-administered survey via electronic tablet at study enrollment after HIV antibody testing. For participants who enrolled with AHI, an extension of the initial survey was administered following AHI diagnosis to capture detailed information on sexual partners.

Analyses: combination intervention vs. pPN

Analysis sample

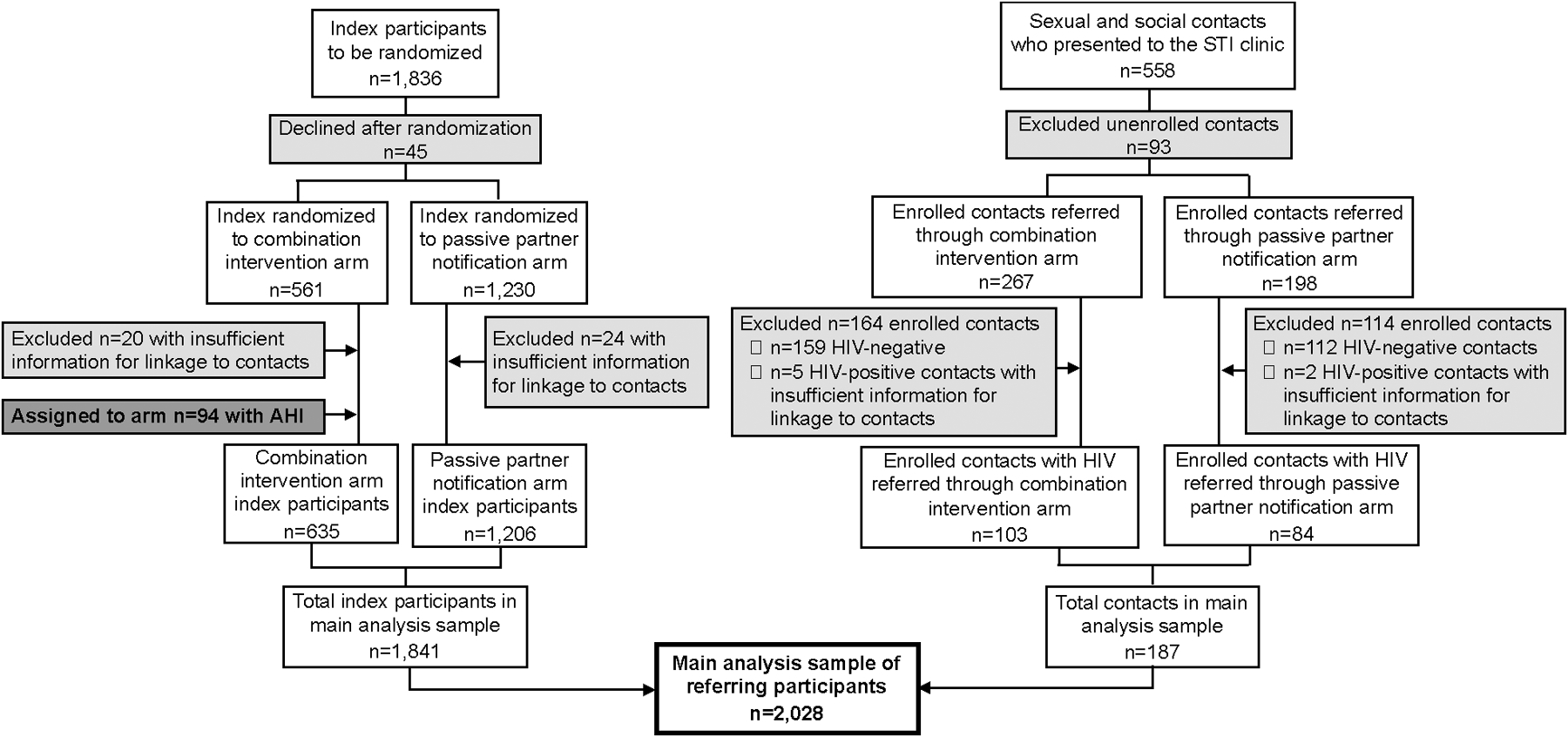

This analysis sample comprised all participants with HIV: index participants and referred sexual and social contacts with HIV who received counseling to refer their sexual or social contacts for HTS, according to either the combination intervention or pPN arm procedures. Henceforth, this analysis sample is called referring participants (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Referring participant population in analyses comparing the combination intervention with passive partner notification.

Measures

We had three primary outcomes of interest. Our first outcome of interest was any presenting contact, defined as having had at least one sexual or social contact present to the STI clinic for HTS. A presenting contact included any person attending the clinic with a coded referral card directly linking them to a referring participant. All linkable presenting contacts were included in the outcome, irrespective of study enrollment and HIV status. Presenting contacts who were unable to be linked to a referring participant were excluded. Our second outcome of interest, newly HIV-diagnosed presenting contact, was defined as having at least one presenting contact with newly diagnosed HIV infection (either acute or seropositive). Our third outcome was HIV-negative presenting contact, defined as having at least one HIV-negative presenting contact.

Referring participant characteristics of interest were enrollment type (index vs. contact), HIV diagnosis status [new (acute or seropositive) vs. previous], sex (female vs. male), marital status [not married (never married, separated, divorced, or widowed) vs. married], more than one sexual partner in the previous four weeks (yes vs. no), and age (18–24 vs. ≥25 years).

Statistical analyses

We first calculated the proportion of referring participants with each of the three primary outcomes (any contact, ≥1 newly HIV diagnosed contact, ≥1 HIV-negative contact) according to referring participant characteristic and study arm (intervention vs. pPN).

We used generalized linear models with an identity link and binomial distribution to estimate the prevalence differences (PDs) and 95% confidence intervals (CIs) for each outcome of interest, comparing intervention arm participants to pPN arm participants. In each model, we included a product term between the study arm and each referring participant characteristic to produce separate characteristic-specific exposure-outcome estimates. We used likelihood ratio tests (LRTs) to assess whether each exposure-outcome relationship varied by characteristic, with a threshold of α=0.15 for statistical significance.

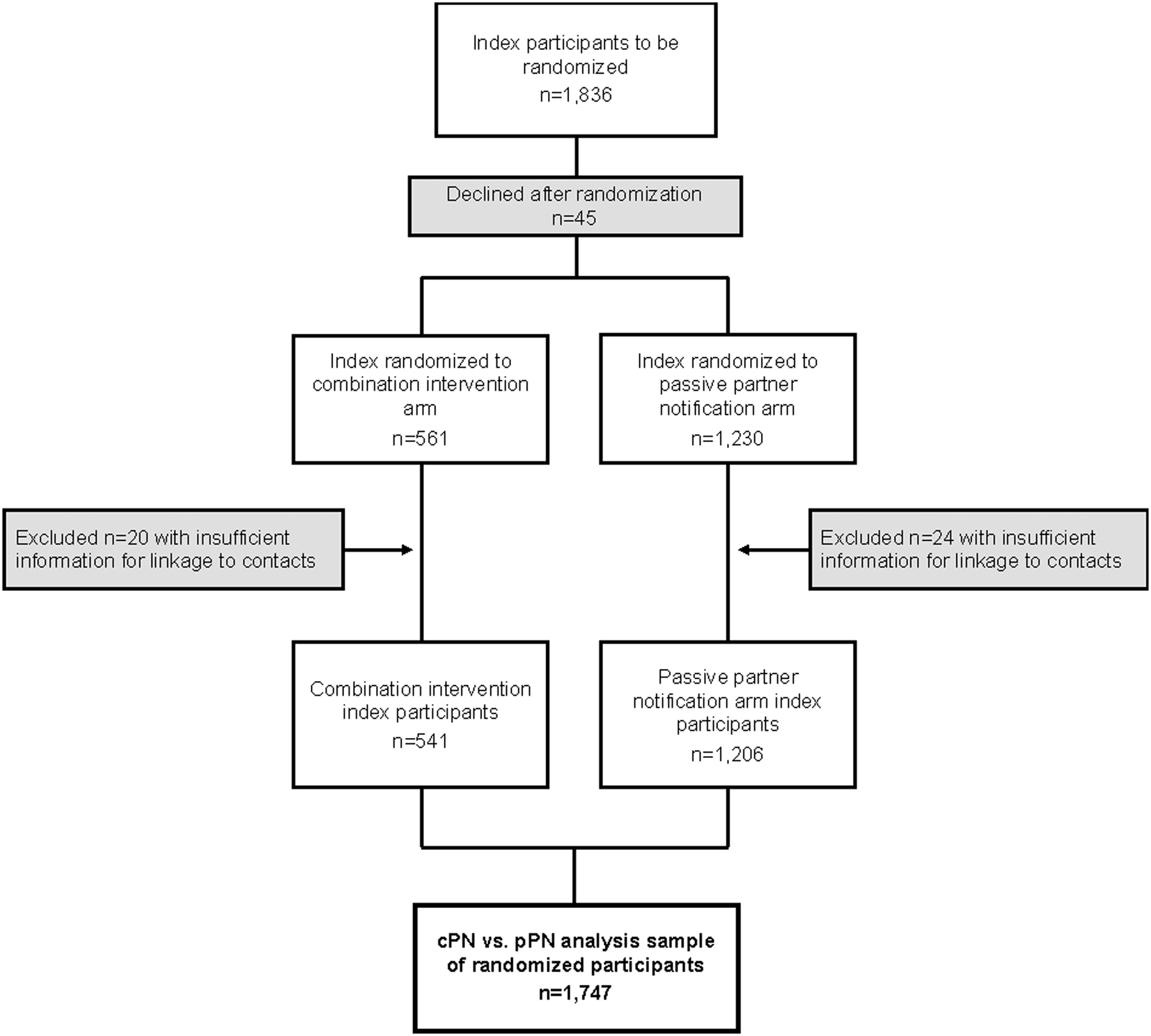

Analyses: cPN vs. pPN

To estimate the effect of the cPN component of the intervention alone, we restricted the referring participant population to randomized, seropositive index participants (i.e., we excluded all presenting sexual and social contacts, and all persons diagnosed with AHI, from the referring participant population), and repeated all statistical analyses. Henceforth, this restricted analysis sample is called randomized index participants (Figure 3).

Figure 3.

Randomized index participant population in analyses comparing contract partner notification with passive partner notification.

In these analyses, we counted only presenting sexual contacts for each outcome, excluding presenting social contacts and persons diagnosed with AHI from presenting contact counts. The three outcomes in this population were thus any: 1) presenting sexual contact; 2) newly HIV-seropositive presenting sexual contact (as persons with AHI were excluded); and 3) HIV-seronegative presenting sexual contact.

All analyses were performed using SAS 9.4 (SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC, USA).

Ethical approval

The Institutional Review Board at the University of North Carolina and the Malawi National Health Services Research Committee reviewed and approved all study procedures, which were in accordance with the ethical standards of the responsible committee on human experimentation (institutional and national) and with the Helsinki Declaration of 1975, as revised in 2000. The RCT is registered at clinicaltrials.gov (NCT02467439).

RESULTS

The final analysis sample comparing the combination intervention with pPN included a total of 2,028 referring participants (n=1,841 index participants; n=187 contacts who were assigned to an arm according to referring index arm) (Figure 2). For analyses comparing cPN only to pPN, the final analysis sample included a total of 1,747 randomized index participants (Figure 3).

Combination intervention vs. pPN

Overall, 29% of participants in the intervention arm had a contact present to the clinic, compared to 15% of participants in the pPN arm [prevalence difference (PD): 0.14, 95% CI: (0.11, 0.18)] (Table 1). Higher proportions of participants in the intervention vs. pPN arm had any presenting contact within each participant characteristic stratum, but there were statistically significant differences in intervention effect by enrollment type, HIV diagnosis status, and sex.

Table 1.

Referring participants with any presenting contact, a newly HIV-diagnosed presenting contact, or an HIV-negative presenting contact, comparing the combination intervention versus passive partner notification alone (N=2,028)

| Referring participant characteristic | Combination intervention (N=738) vs. pPN (N=1,290) | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Any presenting contact |

Newly HIV-diagnosed presenting contact |

HIV-negative presenting contact |

|||||||

| Combo* | pPN | PD (95% CI) | Combo | pPN | PD (95% CI) | Combo | pPN | PD (95% CI) | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||||

| Overall | 214 (29) | 188 (15) | 0.14 (0.11, 0.18) | 37 (5) | 37 (3) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.04) | 109 (15) | 87 (7) | 0.08 (0.05, 0.11) |

| Enrollment type | |||||||||

| Contact | 29 (28) | 3 (4) | 0.25 (0.15, 0.34)† | 6 (6) | 1 (1) | 0.05 (0.00, 0.10) | 16 (16) | 3 (4) | 0.12 (0.04, 0.20) |

| Index | 185 (29) | 185 (15) | 0.14 (0.10, 0.18)† | 31 (5) | 36 (3) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.04) | 93 (15) | 84 (7) | 0.08 (0.05, 0.11) |

| HIV diagnosis status | |||||||||

| New diagnosis | 121 (25) | 124 (14) | 0.11 (0.07, 0.16)† | 27 (6) | 30 (3) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.05) | 62 (13) | 56 (6) | 0.07 (0.03, 0.10) |

| Previous diagnosis | 93 (36) | 64 (16) | 0.20 (0.13, 0.27)† | 10 (4) | 7 (2) | 0.02 (-0.01, 0.05) | 47 (18) | 31 (8) | 0.10 (0.05, 0.16) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 127 (29) | 90 (12) | 0.17 (0.13, 0.22)† | 23 (5) | 16 (2) | 0.03 (0.13, 0.22) | 67 (15) | 46 (6) | 0.09 (0.06, 0.13) |

| Male | 87 (29) | 98 (19) | 0.10 (0.04, 0.16)† | 14 (5) | 21 (4) | 0.01 (0.04, 0.16) | 42 (14) | 41 (8) | 0.06 (0.02, 0.11) |

| Age | |||||||||

| 18–24 years | 51 (27) | 35 (11) | 0.17 (0.09, 0.24) | 7 (4) | 5 (2) | 0.02 (-0.01, 0.05) | 34 (18) | 18 (6) | 0.13 (0.07, 0.19)† |

| ≥25 years | 162 (30) | 153 (16) | 0.14 (0.09, 0.18) | 29 (5) | 32 (3) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.04) | 75 (14) | 69 (7) | 0.07 (0.03, 0.10)† |

| Marital status ‡ | |||||||||

| Not married | 49 (18) | 18 (5) | 0.13 (0.08, 0.18) | 8 (3) | 5 (1) | 0.02 (-0.01, 0.04) | 32 (12) | 13 (3) | 0.08 (0.04, 0.13) |

| Married | 162 (36) | 167 (19) | 0.17 (0.12, 0.22) | 28 (6) | 32 (4) | 0.03 (0.00, 0.05) | 77 (17) | 72 (8) | 0.09 (0.05, 0.13) |

| >1 recent sex partner § | |||||||||

| Yes | 35 (39) | 26 (17) | 0.22 (0.10, 0.33) | 4 (4) | 8 (5) | −0.01 (-0.06, 0.04) | 24 (27) | 15 (10) | 0.17 (0.06, 0.27)† |

| No | 176 (28) | 159 (14) | 0.13 (0.09, 0.17) | 32 (5) | 29 (3) | 0.02 (0.00, 0.04) | 85 (13) | 70 (6) | 0.07 (0.04, 0.10)† |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; Combo = combination intervention; PD = prevalence differences; pPN = passive partner notification

Presenting sexual contacts: n=5 newly diagnosed with AHI, n=26 newly diagnosed as HIV-seropositive, n=74 previously HIV-diagnosed, n=83 HIV-negative; presenting social contacts: n=7 newly diagnosed as HIV-seropositive, n=21 previously HIV-diagnosed, n=59 HIV-negative; presenting contacts with missing referral type: n=1 newly diagnosed as HIV-seropositive, n=1 HIV-negative.

P-value <0.15 for likelihood ratio tests from binomial models assessing whether each exposure-outcome relationship varied by referring participant characteristic.

Not married includes never married, separated, divorced, or widowed.

Recent = previous 4 weeks; Yes = ≥2 sexual partners; No = 0–1 sexual partners; eligibility criteria included having had any sexual activity within the previous 6 months.

The intervention effect on having any presenting contact was higher among participants initially enrolled as a contact [28% vs. 4%; PD:0.25, 95% CI:(0.15, 0.34)] than among participants initially enrolled as an index [29% vs. 15%; PD:0.14, 95% CI:(0.10, 0.18); LRT p=0.04]. Intervention impact on having any presenting contact was more pronounced among participants with a previous HIV diagnosis [36% vs. 16%; PD:0.20, 95% CI:(0.13, 0.27)] than among newly diagnosed participants [25% vs. 14%; PD:0.11, 95% CI:(0.07, 0.16); LRT p=0.05]. Intervention impact on having a presenting contact was higher among females [29% vs. 12%; PD:0.17, 95% CI:(0.13, 0.22)] than among males [29% vs. 19%; PD:0.10, 95% CI:(0.04, 0.16); LRT p=0.06].

The effect of the intervention on having a newly HIV-diagnosed contact present to the clinic was low overall [5% intervention vs. 3% pPN; PD:0.02, 95% CI:(0.00, 0.04)]. There were no notable differences in effect according to referring participant characteristics.

Overall, 15% of intervention participants and 7% of pPN participants had an HIV-negative contact present to the clinic [PD:0.08, 95% CI:(0.05, 0.11)]. The intervention had a larger impact among referring participants ages 18 to 24 years [18% vs. 6%; PD:0.13, 95% CI:(0.07, 0.19)] than among participants ages ≥25 years [14% vs. 7%; PD:0.07, 95% CI:(0.03, 0.10); LRT p=0.07] and among referring participants with multiple recent sex partners versus those with ≤1 partner [PD:0.17, 95% CI:(0.06, 0.27) vs. PD:0.07, 95% CI:(0.04, 0.10); LRT p=0.07].

cPN only vs. pPN

Among the 1,747 randomized index participants, 27% of cPN participants and 16% of pPN participants had a presenting sexual contact [PD:0.12, 95% CI:(0.08, 0.16)] (Table 2). A higher proportion of those in the cPN vs. pPN arm had a presenting sexual contact in all characteristic strata, but there were notable differences in cPN effect according to HIV diagnosis status, sex, and marital status. We observed a greater cPN impact on having any presenting sexual contact among previously diagnosed participants [34% vs. 18%; PD:0.17, 95% CI:(0.09, 0.24)] than among newly diagnosed participants [23% vs. 14%; PD:0.09, 95% CI:(0.04, 0.14); LRT p=0.10]. The effect of cPN alone on having any presenting sexual contact was greater among females [27% vs. 13%; PD:0.15, 95% CI:(0.09, 0.20)] than among males [27% vs. 20%; PD:0.08, 95% CI: (0.01, 0.15); LRT p=0.14], and among married participants [36% vs. 20%; PD:0.16, 95% CI: (0.10, 0.22)] than among unmarried participants [13% vs. 4%; PD:0.08, 95% CI:(0.03, 0.13); LRT p=0.06)].

Table 2.

Randomized index participants with any presenting sexual contact, a newly HIV-seropositive presenting sexual contact, or an HIV-seronegative presenting sexual contact, comparing contract partner notification alone versus passive partner notification (N=1,747)

| cPN (N=541) vs. pPN (N=1,206) | |||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Referring participant characteristic | Any presenting contact |

Newly HIV-diagnosed presenting contact |

HIV-negative presenting contact |

||||||

| cPN | pPN | PD (95% CI) | cPN | pPN | PD (95% CI) | cPN | pPN | PD (95% CI) | |

| N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | N (%) | ||||

| Overall | 147 (27) | 188 (16) | 0.12 (0.08, 0.16) | 19 (4) | 36 (3) | 0.01 (-0.01, 0.02) | 68 (13) | 84 (7) | 0.06 (0.02, 0.09) |

| HIV diagnosis status | |||||||||

| New diagnosis | 81 (23) | 123 (14) | 0.09 (0.04, 0.14)* | 12 (3) | 30 (4) | 0.00 (-0.02, 0.02) | 41 (12) | 55 (6) | 0.05 (0.02, 0.09) |

| Previous diagnosis | 66 (34) | 62 (18) | 0.17 (0.09, 0.24)* | 7 (4) | 6 (2) | 0.01 (-0.10, 0.11) | 27 (14) | 29 (8) | 0.06 (0.00, 0.11) |

| Sex | |||||||||

| Female | 91 (27) | 90 (13) | 0.15 (0.09, 0.20)* | 13 (4) | 16 (2) | 0.02 (-0.01, 0.04) | 45 (13) | 46 (6) | 0.07 (0.03, 0.11) |

| Male | 56 (27) | 95 (20) | 0.08 (0.01, 0.15)* | 6 (3) | 20 (4) | −0.01 (-0.04, 0.02) | 23 (11) | 38 (8) | 0.03 (-0.02, 0.08) |

| Age | |||||||||

| 18–24 years | 33 (24) | 34 (11) | 0.13 (0.05, 0.21) | 3 (2) | 4 (1) | 0.01 (-0.02, 0.04) | 21 (15) | 17 (6) | 0.10 (0.03, 0.16)* |

| ≥25 years | 113 (28) | 151 (17) | 0.11 (0.06, 0.17) | 15 (4) | 32 (4) | 0.00 (-0.02, 0.02) | 47 (12) | 67 (7) | 0.04 (0.01, 0.08)* |

| Marital status † | |||||||||

| Not married | 26 (13) | 16 (4) | 0.08 (0.03, 0.13)* | 4 (2) | 4 (1) | 0.01 (-0.01, 0.03) | 18 (9) | 11 (3) | 0.06 (0.02, 0.10) |

| Married | 119 (36) | 166 (20) | 0.16 (0.10, 0.22)* | 15 (5) | 32 (4) | 0.01 (-0.02, 0.03) | 50 (15) | 71 (9) | 0.06 (0.02, 0.11) |

| >1 recent sex partner ‡ | |||||||||

| Yes | 24 (33) | 25 (17) | 0.16 (0.04, 0.29) | 1 (1) | 7 (5) | −0.03 (-0.08, 0.01)* | 16 (22) | 14 (10) | 0.13 (0.02, 0.23) |

| No | 121 (26) | 157 (15) | 0.11 (0.07, 0.16) | 18 (4) | 29 (3) | 0.01 (-0.01, 0.03)* | 52 (11) | 68 (7) | 0.05 (0.01, 0.08) |

Abbreviations: CI = confidence interval; cPN = contract partner notification; PD = prevalence differences; pPN = passive partner notification

P-value <0.15 for likelihood ratio tests from binomial models assessing whether each exposure-outcome relationship varied by referring participant characteristic.

Not married includes never married, separated, divorced, or widowed.

Recent = previous 4 weeks; Yes = ≥2 sexual partners; No = 0–1 sexual partners; eligibility criteria included having had any sexual activity within the previous 6 months.

cPN alone did not have a meaningful impact on the percentage of participants with a newly seropositive presenting sexual contact, relative to pPN overall [4% vs. 3%; PD:0.01, 95% CI:(-0.01, 0.02)]. The effect of cPN on having a newly seropositive sexual contact present was similar across most participant characteristics, differing only slightly according to number of sexual partners in the prior four weeks. cPN participants with multiple recent partners were less likely to have a newly HIV-seropositive presenting sexual contact compared to pPN participants [1% vs. 5%; PD: −0.03, 95% CI:(-0.08, 0.01)]; those with ≤1 recent partner were equally likely to have a newly HIV-seropositive presenting sexual contact in both the cPN and pPN arms [4% vs. 3%; PD:0.01, 95% CI:(-0.01, 0.03); LRT p=0.10].

A higher percentage of cPN participants had an HIV-seronegative presenting sexual contact than pPN participants overall [13% vs. 7%; PD:0.06, 95% CI:(0.02, 0.09)]. The effect of cPN on having an HIV-seronegative presenting sexual contact was higher among randomized index participants ages 18–24 years compared to those ages ≥25 years [PD:0.10, 95% CI:(0.03, 0.16) vs. PD:0.04, 95% CI:(0.01, 0.08); LRT p=0.13].

DISCUSSION

In this analysis, we identified subpopulations of PWH for whom network-based HIV testing interventions20 most substantially enhanced contact HTS uptake compared to a passive notification strategy in an STI clinic in Lilongwe, Malawi. While both our combination intervention and cPN alone were more effective than pPN across nearly all participant strata and contact types assessed, our results suggest that some PWH are especially likely to benefit from specific aspects of these resource-intensive tracing efforts, providing an opportunity to focus efforts and optimize referral of persons with undiagnosed HIV and HIV-negative persons at substantial risk of acquiring HIV in resource-limited settings.

Our findings suggest that in settings where the combination intervention package of AHI screening, cPN, and social network referral is feasible, intervention deployment specifically among women and previously HIV-diagnosed persons may be most beneficial in reaching network members of any HIV status. In settings where cPN alone is feasible, without AHI testing and social contact referral, a focus on women and previously diagnosed people may again be efficient. Our results further suggest that deployment of cPN alone among married persons could improve HTS uptake among sexual partners. These differential intervention impacts by subgroup support the WHO-endorsed differentiated service delivery approach to enhance HIV health resources in subpopulations with the highest care needs, versus a “one-size-fits-all” approach.25–27 For example, sex differences in HIV status awareness is a key consideration in differentiated service delivery for HIV testing and contact tracing in sub-Saharan African populations,25 given that men have consistently lower testing rates than women. Offering enhanced PN services to women with HIV may efficiently identify male contacts at risk for HIV or those with undiagnosed HIV who would otherwise not present to the clinic.17,27–29 In addition to these voluntary PN interventions, offering a variety of HTS options that have been shown to increase testing uptake in men (e.g., community-based sites and self-testing initiatives) may aid in reducing the HIV testing gap between men and women.30–32

We also observed a pronounced intervention impact on any contact presentation among referring participants enrolled as referred contacts compared to persons initially enrolled as index participants. Chain referral extends the potential case-finding reach of PN into waves well beyond the initially presenting index, and the subsequent waves of contact referrals outpaced those of the index participants in our study. The effectiveness of multi-wave HIV chain referral in sub-Saharan African is not well documented, and the apparent increased motivation of continued referral among presenting contacts in our study may be an important point for further investigation.

In a previous analysis using data from this RCT,20 we demonstrated that the combination intervention increased the number of undiagnosed HIV infections detected per index participant compared to pPN. Here, we expanded upon those prior analyses by including all persons who were eligible to refer contacts for HTS (i.e., all index and enrolled presenting contacts with HIV) and examining intervention effects both overall and by participant characteristics. Additionally, our outcome definitions for presenting contacts included both enrolled and unenrolled contacts who presented to the clinic. Similar to the main trial results, we found that the combination intervention may aid in reaching undiagnosed persons overall, and we did not observe meaningful differences between arms by participant characteristics. Although the intervention increased the presentation of undiagnosed PWH both here and in the main trial findings,20 overall recruitment of newly diagnosed contacts was low in each arm. We also observed that cPN alone (the updated standard of care since 201922) vs. pPN was not effective with regard to identifying a higher percentage of newly-diagnosed contacts. In order to expand HIV case-finding with cPN, Malawi is currently integrating assisted self-testing with community workers, with special focus on key populations such as younger persons, men, and female sex workers.22 The low HIV case finding yield in our study populations may in part be explained by a high HIV status awareness among PWH in Malawi33 which potentially extends to sexual and social contacts of PWH.

HIV case-finding (with linkage to ART) is only one of the potential means through which network-based interventions can interrupt HIV transmission. Referral of HIV-negative contacts to HTS presents an opportunity for focused HIV prevention services for persons at particularly high risk of HIV acquisition. We found that the combination intervention may be particularly likely to improve referral of HIV-negative contacts by younger PWH and those with >1 sex partner. As access to HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) expands across sub-Saharan Africa, including in Malawi,34,35 the recruitment of HIV-negative sexual and social contacts will become increasingly important for linkage to these prevention services. In settings where resources may be too low to offer the combination intervention, our results suggest that the less resource-intensive approach of cPN alone may be similarly beneficial in these groups. Furthermore, assisted PN may identify persons with known HIV infection who are not on ART, representing another critical opportunity for linkage to HIV care. Although previously HIV-diagnosed persons (of any ART status) were included in our definition of any presenting contact, we did not separately estimate intervention or cPN effects on presentation of previously diagnosed persons (overall or according to ART status), limiting our ability to comment on the specific prevention benefits associated with finding such persons with these strategies.

Conclusions

Consistent with a WHO-endorsed differentiated service delivery approach,25–27 our findings highlight opportunities to leverage clinical resources and customize enhanced HIV testing and referral services for subpopulations of STI clinic patrons who are most likely to derive additional benefit beyond pPN strategies. An intervention package of AHI screening, cPN, and social contact referral may be particularly efficacious in eliciting chain referrals and contact referrals from women and previously diagnosed persons. In settings where the combination intervention may not be feasible, cPN alone is an opportunity for lower-cost assistance for these populations. In addition, our findings suggest the combination intervention or cPN alone may boost referrals of HIV-negative sexual and social contacts among younger persons, presenting focused opportunity to extend HIV prevention services such as testing, counseling, and PrEP linkage to populations at high risk of HIV acquisition.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

The authors would like to thank the STI clinic staff at Bwaila District Hospital, the student research assistants, and all participants for their important contributions to this project.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding

This work was supported by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health (R01AI114320 to WCM and KAP; T32AI070114 to CNM and JSC; T32AI007001 to SER and NLB); the University of North Carolina at Chapel Hill Center for AIDS Research (P30AI50410); and the Fogarty International Center at the National Institutes of Health (D43 TW010060 to MM). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the National Institutes of Health. The STI Clinic at Bwaila District Hospital is co-funded by the Lilongwe District Health Office, the Malawi Ministry of Health and UNC Project, Malawi.

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

REFERENCES

- 1.Malawi Ministry of Health. Malawi Population-Based HIV Impact Assessment 2020–2021 Malawi Population-Based HIV Impact Assessment MPHIA 2020–2021.; 2022. http://phia.icap.columbia.edu. Accessed January 27, 2023.

- 2.Gardner EM, McLees MP, Steiner JF, et al. The Spectrum of Engagement in HIV Care and its Relevance to Test-and-Treat Strategies for Prevention of HIV Infection. Clin Infect Dis. 2011;52(6):793–800. doi: 10.1093/cid/ciq243 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cohen MS, Shaw GM, McMichael AJ, Haynes BF. Acute HIV-1 Infection. N Engl J Med. 2011;364(20):1943–1954. doi: 10.1056/NEJMra1011874 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Miller WC, Rosenberg NE, Rutstein SE, Powers KA. Role of acute and early HIV infection in the sexual transmission of HIV. Curr Opin HIV AIDS. 2010;5(4):277–282. doi: 10.1097/COH.0b013e32833a0d3a [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.UNAIDS. 2025 AIDS TARGETS - UNAIDS. https://aidstargets2025.unaids.org/. Published 2022. Accessed November 3, 2022.

- 6.Powers KA, Ghani AC, Miller WC, et al. The Role of Acute and Early HIV Infection in the Spread of HIV-1 in Lilongwe, Malawi: Implications for “Test and Treat” and Other Transmission Prevention Strategies. 2011. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(11)60842-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hogben M, McNally T, McPheeters M, Hutchinson AB. The effectiveness of HIV partner counseling and referral services in increasing identification of HIV-positive individuals a systematic review. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(2 Suppl):S89–100. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Task Force on Community Preventive Services. Recommendations to increase testing and identification of HIV-positive individuals through partner counseling and referral services. Am J Prev Med. 2007;33(2 Suppl):S88. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2007.04.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization. Guidelines on HIV Self-Testing and Partner Notification: Supplement to Consolidated Guidelines on HIV Testing Services; 2016. https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/251655. Accessed November 15, 2021. [PubMed]

- 10.World Health Organization. WHO Recommends Assistance for People with HIV to Notify Their Partners. Policy Brief. HIV Testing Services; 2016. www.who.int/hiv. Accessed November 15, 2021.

- 11.Ward H, Bell G. Partner notification. Medicine (Abingdon). 2014;42(6):314–317. doi: 10.1016/j.mpmed.2014.03.013 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tih PM, Temgbait Chimoun F, Mboh Khan E, et al. Assisted HIV partner notification services in resource-limited settings: experiences and achievements from Cameroon. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22 Suppl 3(Suppl Suppl 3):e25310. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25310 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rutstein SE, Brown LB, Biddle AK, et al. Cost-effectiveness of provider-based HIV partner notification in urban Malawi. Health Policy Plan. 2014;29(1):115–126. doi: 10.1093/HEAPOL/CZS140 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Brown LB, Miller WC, Kamanga G, et al. HIV Partner Notification Is Effective and Feasible in Sub-Saharan Africa: Opportunities for HIV Treatment and Prevention. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2011;56(5):437–442. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0b013e318202bf7d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sharma M, Smith JA, Farquhar C, et al. Assisted partner notification services are cost-effective for decreasing HIV burden in western Kenya. AIDS. 2018;32(2):233–241. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0000000000001697 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Myers RS, Feldacker C, Cesár F, et al. Acceptability and Effectiveness of Assisted Human Immunodeficiency Virus Partner Services in Mozambique: Results From a Pilot Program in a Public, Urban Clinic. Sex Transm Dis. 2016;43(11):690–695. doi: 10.1097/OLQ.0000000000000529 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Masyuko SJ, Cherutich PK, Contesse MG, et al. Index participant characteristics and HIV assisted partner services efficacy in Kenya: results of a cluster randomized trial. 2019. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25305/full [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rosenberg NE, Kamanga G, Pettifor AE, et al. STI Patients Are Effective Recruiters of Undiagnosed Cases of HIV. JAIDS J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2014;65(5):e162–e169. doi: 10.1097/QAI.0000000000000066 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ssali S, Wagner G, Tumwine C, Nannungi A, Green H. HIV Clients as Agents for Prevention: A Social Network Solution. AIDS Res Treat. 2012;2012:1–7. doi: 10.1155/2012/815823 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Chen JS, Matoga M, Pence BW, et al. A randomized controlled trial evaluating combination detection of HIV in Malawian sexually transmitted infections clinics. J Int AIDS Soc. 2021;24(4):e25701. doi: 10.1002/jia2.25701 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Rutstein SE, Ananworanich J, Fidler S, et al. Clinical and public health implications of acute and early HIV detection and treatment: a scoping review. J Int AIDS Soc. 2017;20(1):21579. doi: 10.7448/IAS.20.1.21579 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.National AIDS Commission Malawi. Malawi National Strategic Plan for HIV and AIDS 2020–2025.; 2020.

- 23.Miller WC, Leone PA, McCoy S, Nguyen TQ, Williams DE, Pilcher CD. Targeted Testing for Acute HIV Infection in North Carolina. AIDS. 2009;23(7):835. doi: 10.1097/QAD.0B013E328326F55E [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pilcher CD, Fiscus SA, Nguyen TQ, et al. Detection of acute infections during HIV testing in North Carolina. N Engl J Med. 2005;352(18):1873–1883. doi: 10.1056/NEJMOA042291 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.International AIDS Society. Differentiated Service Delivery for HIV: A Decision Framework for HIV Tetsing Services.; 2022.

- 26.World Health Organization. Service Delivery for the Tteatment and Care of People Living with HIV Guidelines.; 2021. https://apps.who.int/iris/bitstream/handle/10665/341052/9789240023581-eng.pdf. Accessed February 4, 2022. [PubMed]

- 27.Phiri MM, Schaap A, Simwinga M, et al. Closing the gap: did delivery approaches complementary to home‐based testing reach men with HIV testing services during and after the HPTN 071 (PopART) trial in Zambia? J Int AIDS Soc. 2022;25(1). doi: 10.1002/jia2.25855 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Staveteig S, Wang S, Head SK, Bradley SEK, Nybro E, Macro I. Demographic Patterns of HIV Testing Uptake in Sub-Saharan Africa.; 2013. www.measuredhs.com. Accessed February 6, 2022.

- 29.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). Blind Spot: Reaching out to men and boys — Addressing a blind spot in the response to HIV.

- 30.Hlongwa M, Mashamba-Thompson T, Makhunga S, Hlongwana K. Barriers to HIV testing uptake among men in sub-Saharan Africa: a scoping review. African J AIDS Res. 2020;19(1):13–23. doi: 10.2989/16085906.2020.1725071 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sharma M, Barnabas RV., Celum C. Community-based strategies to strengthen men’s engagement in the HIV care cascade in sub-Saharan Africa. PLOS Med. 2017;14(4):e1002262. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1002262 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Indravudh PP, Fielding K, Kumwenda MK, et al. Effect of community-led delivery of HIV self-testing on HIV testing and antiretroviral therapy initiation in Malawi: A cluster-randomised trial. Fox MP, ed. PLOS Med. 2021;18(5):e1003608. doi: 10.1371/journal.pmed.1003608 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Joint United Nations Programme on HIV/AIDS (UNAIDS). UNAIDS Data 2021.; 2021. https://www.unaids.org/sites/default/files/media_asset/JC3032_AIDS_Data_book_2021_En.pdf. Accessed December 2, 2022.

- 34.Avert. HIV and AIDS in Malawi. https://www.avert.org/professionals/hiv-around-world/sub-saharan-africa/malawi. Published 2020. Accessed November 15, 2021.

- 35.AVAC. PrEPWatch – Malawi. https://www.prepwatch.org/country/malawi/. Published 2022. Accessed February 6, 2022.