Abstract

Bacterial biofilms are critical to pathogenesis and infection. They are associated with rising rates of antimicrobial resistance. Biofilms are correlated with worse clinical outcomes, making them important to infectious diseases research. There is a gap in knowledge surrounding biofilm kinetics and dynamics which makes biofilm research difficult to translate from bench to bedside. To address this gap, this work employs a well-characterized crystal violet biomass accrual and planktonic cell density assay across a clinically relevant time course and expands statistical analysis to include kinetic information in a protocol termed the TMBL (Temporal Mapping of the Biofilm Lifecycle) assay. TMBL’s statistical framework quantitatively compares biofilm communities across time, species, and media conditions in a 96-well format. Measurements from TMBL can reliably be condensed into response features that inform the time-dependent behavior of adherent biomass and planktonic cell populations. Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms were grown in conditions of metal starvation in nutrient-variable media to demonstrate the rigor and translational potential of this strategy. Significant differences in single-species biofilm formation are seen in metal-deplete conditions as compared to their controls which is consistent with the consensus literature on nutritional immunity that metal availability drives transcriptomic and metabolomic changes in numerous pathogens. Taken together, these results suggest that kinetic analysis of biofilm by TMBL represents a statistically and biologically rigorous approach to studying the biofilm lifecycle as a time-dependent process. In addition to current methods to study the impact of microbe and environmental factors on the biofilm lifecycle, this kinetic assay can inform biological discovery in biofilm formation and maintenance.

Keywords: Biofilm Formation, Crystal Violet, Time-dependent, Nutritional Immunity, Staphylococcus aureus, Pseudomonas aeruginosa

1. INTRODUCTION

Epidemiological studies have established that biofilms play critical roles in the incidence and outcome of at least 65% of clinical infections.1–6 The conventional biofilm lifecycle is a dynamic process where microbes form communities that attach, adhere, accumulate, disaggregate, and detach from surfaces and from one another.7 Biofilms are classically composed of bacterial and/or fungal cells in various metabolic states which produce an extracellular matrix (ECM) composed of polysaccharides, extracellular DNA, proteins, and other polymers that together define the ability of a cell population to adhere to surfaces, grow on those surfaces, form a biofilm, and disperse to promote growth and biofilm formation in other locations.8–14 This proposed model of the biofilm lifecycle has been refined from experiments which suggest that biofilm formation occurs in a cyclical process of attachment, accumulation, and dispersal.7 There remain gaps in knowledge surrounding the kinetic behavior of biofilm, including that of pathogens like Staphylococcus aureus and Pseudomonas aeruginosa, which are typically studied at distinct timepoints depending on the specific intent of the study12,15–19. This has limited discovery and screening of effectors and small molecules that mediate or interfere with bacterial adherence, biofilm development, and community dispersal that could be aided by the use of a more granular, high-throughput, statistically robust, kinetic analysis.

S. aureus is a top cause of bacterial-associated mortality worldwide and is a leading cause of antimicrobial-resistance associated mortality.1,20–22 As a major contributor to the global burden of infectious diseases, S. aureus benefits from the production of dozens of virulence factors and the ability to form biofilms.23,24 These key features have made S. aureus an ideal model for the study of Gram-positive bacterial biofilm formation. Similar to S. aureus, the Gram-negative opportunistic pathogen P. aeruginosa also forms biofilms in mono- and co-culture. P. aeruginosa is an opportunistic pathogen commonly seen in patients with chronic health conditions including cystic fibrosis and diabetes. Notably, P. aeruginosa produces a number of well-characterized virulence factors, and is increasingly recalcitrant and resistant to treatment strategies.2,25–37

Biofilm formation can be induced by antibiotic treatment and aids in the development of antimicrobial resistance, as the niches that biofilms occupy promote genetic diversity within the spatial and temporal organization of a biofilm.7,9,12,13,27,29,38–42 Treatment of S. aureus with sub-inhibitory concentrations of clindamycin results in the upregulation of genes associated with biofilm and aggregation (atlA, lrgA, agrA, psm, fnbA, and fnbB).3,11,43 Evaluation of biomass accumulation as an early stage of biofilm formation has suggested the importance of key transcriptional regulatory elements of the ica and agr operons to facilitate downstream processes of attachment.3,11,43 Separate work has also implicated the agr system in mediating biofilm dispersal and has identified an inverse correlation between biofilm-promoting sigB and biofilm-antagonizing agr RNA III expression.17,44 S. aureus biofilm formation relies also on the expression of sarA, mgrA, sigB, hld, codY, and iron-dependent transcriptional regulator fur.34,45–49 In Pseudomonas species, fur, pvdS, and sadARS are implicated in the response to iron starvation and biofilm formation. Iron acquisition through the pyoverdine family of small molecules allows for biofilm formation to maintain cellular redox potential, and similar systems for controlling redox state across biofilm play vital roles in maintaining the cellular metabolism of cells not exposed to crucial environmental metabolites.26,28,30–32,34,37,46,50,51 S. aureus and P. aeruginosa biofilm formation are responsive to environmental iron in addition to a variety of extracellular factors.34,46,52,53

In the setting of infection, bacteria, fungi, and other infectious agents require transition metals to perform essential cellular processes. In response to this increased demand for metals by infectious agents, the host limits metal availability to combat infection through a process termed nutritional immunity.45,54–58 Research into nutritional immunity has led to the understanding of the importance of iron, manganese, zinc, and other metals to infection and pathogenesis of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa.32,34,57,59–62 Depletion of these metals in the infectious environment redefines bacterial gene regulation in vitro and in vivo.34,45,52,54–57,63–67

To mediate nutritional immunity, S100 proteins play significant roles in sequestration of iron, zinc, copper, manganese, and other micronutrient metals.57,59,68–70 The foremost example of the S100 proteins that defend against infection is calprotectin (CP), an S100A8-A9 heterodimer with high affinity for essential micronutrient divalent metals (Kd ≦ 10−7 M).32,34,61,62,71 Other S100 family members also bind micronutrient metals, including the S100A2, S100A7, and S100A12 homodimers. CP, S100A7 and S100A12 are antibacterial through direct and indirect mechanisms.32,57,59,72–75 There is limited understanding of the impact of metal bioavailability and nutritional immunity on biofilm formation. Further, given the known impact of nutritional immune factors on planktonic bacterial growth, evaluation of these factors on cellular adherence, biofilm formation, and community dynamics could be of critical importance to the study of clinical infection and antibiotic effectiveness in translational models.57,59,68,69,74,76

Taken together, S. aureus and P. aeruginosa biofilm formation are environment-dependent processes that are typically studied at similar stages of the biofilm lifecycle.3,7,9,13,29,31,43,77 Biofilm formation of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa is predicated on the presence of genes involved in the production of quorum sensing molecules, transcriptional-regulatory elements, and/or the response to nutritional immunity.32,34,40,44 Additionally, planktonic cell dynamics in these pathogens are sensitive to the environment and nutrient availability.32,34,60–62 These traits have been observed in rigorous studies of both clinical isolates and lab strains, but inform an incomplete model of the biofilm lifecycle across a clinically relevant infection course.7,14,78,79

Research studying biofilm formation of pathogenic and commensal bacteria and fungi suffers from a principal challenge of biology. Many of the downstream assays for biofilm formation, including quantification of adherent biomass, are endpoint studies. Most assays, including crystal violet quantification of biomass, microscopic examination of biofilm, multi-omic approaches, and evaluation of libraries (genetic, small molecule, or others), require the separation of planktonic and biofilm populations. Evaluation of time-dependence of an in vitro population typically assumes that populations seeded separately behave identically in a given growth environment and over time samples from a population behave identically in the same growth conditions.

Biofilms are in a dynamic equilibrium between surface-adherent aggregates, non-surface adherent aggregates, and non-aggregated cells, which all contribute individually to bacterial pathogenesis and clinical outcomes. In this context, it is important to understand the dynamics of these populations across a clinically relevant time course. However, since biofilm assays are typically terminal for the evaluated sample(s), independent measurements of these populations are difficult to interpret. In this work we describe the incorporation of time-dependence and statistical analysis into an assay of biofilm dynamics through the TMBL Assay that takes advantage of well-established statistical methods. The statistical framework that supports the TMBL Assay involves robust, reproducible measurements across time and randomly assembles samples into time courses based on their environmental condition to avoid potential confounding variables. To demonstrate the power of this statistical approach, we apply the TMBL assay to biofilms that are exposed to altered metal conditions.

2. MATERIALS AND METHODS

2.1. Media and reagents

Tryptic soy and Lysogeny broth were obtained from BD, where phosphate buffered saline and RPMI 1640 media were obtained from Gibco. Ninety-six well, sterile, tissue-culture treated, clear polystyrene flat-bottom plates (DNAse-, RNAse-, DNA-, and pyrogen-free) were obtained from CytoOne. Sigma-Aldrich sourced zinc chloride (>98% purity), manganese (II) chloride tetrahydrate (ReagentPlus, 99% purity), anhydrous calcium chloride (granular, <7.0mm, >93% purity), and iron (III) chloride (97% purity). N, N, N’, N’ - Tetrakis - (2-pyridyl-methyl)-ethylene-diamine (TPEN) and Chelex were obtained from Thermo Scientific. S100A2, S100A7, S100A12 and calprotectin (CP; S100A8/S100A9) WT and mutant proteins were produced and utilized in vitro as described previously.59,61,62,76,80

2.2. Bacterial strains and stock production

All experiments use either the S. aureus bacterial strain Newman or the P. aeruginosa strain PAO1. All bacterial stocks are maintained as −80°C in 20% glycerol. Prior to each experiment, bacteria were streaked onto tryptic soy agar for S. aureus (TSA; 2% agar) and lysogeny broth agar for P. aeruginosa (LBA; 2% agar) and grown at 37°C overnight. From these cultures, single colonies were transferred to liquid tryptic soy broth (TSB) and lysogeny broth (LB), respectively. These cultures were then grown to stationary phase (12–16 hours) at a 45° angle, 180 rpm, 37°C.

2.3. Temporal measurement of the biofilm lifecycle (TMBL)

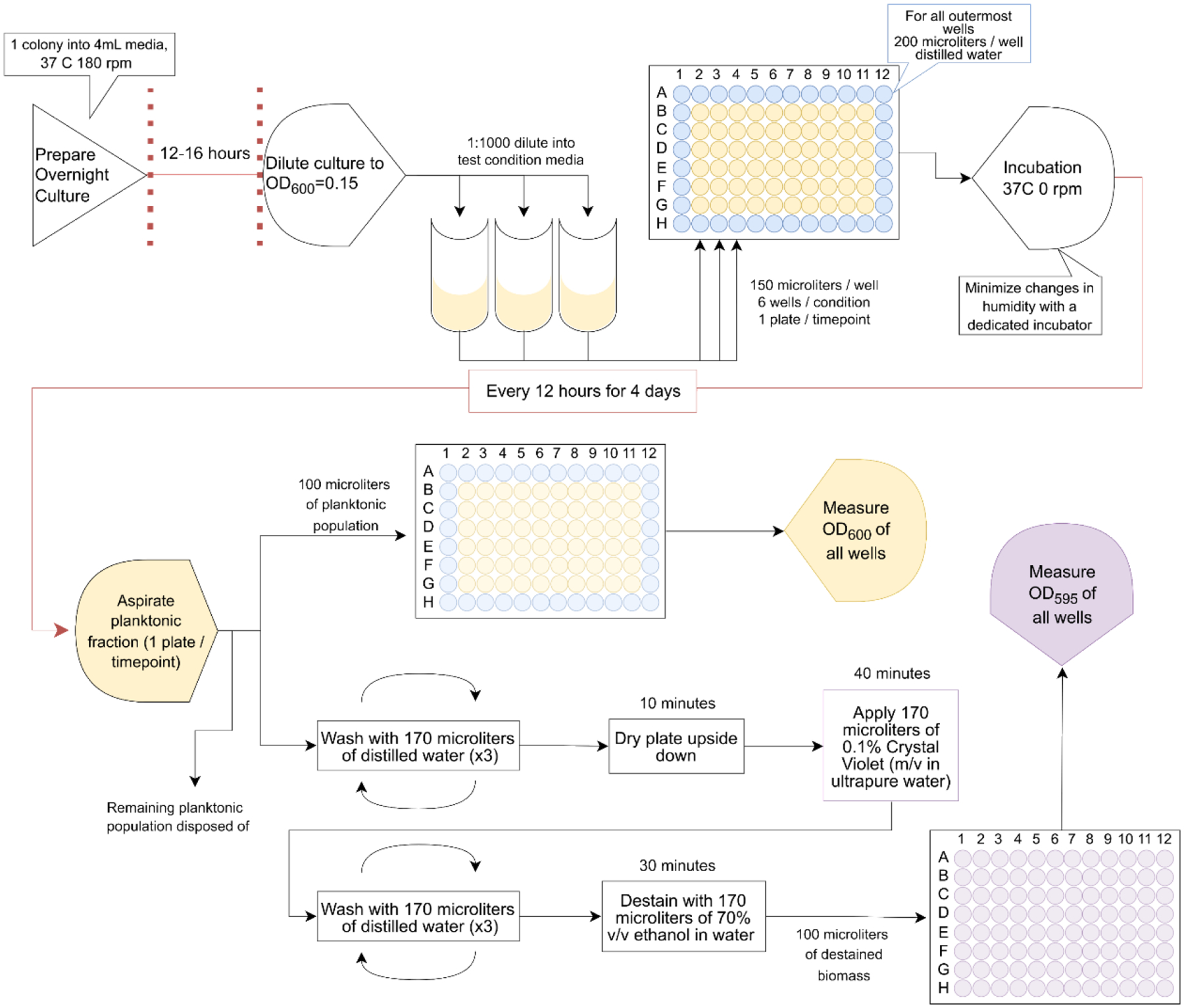

Overnight cultures from single colonies were grown in parallel for 12–16 hours at a 45° angle at 37°C and 180 rpm (Fig. 1). After reaching stationary phase, cultures were diluted with PBS (1x) to an optical density at 600 nm (OD600) of 0.15 ± 0.01, then diluted 1:1000 into the media condition(s) of interest. Aliquots of this mixture (150 μL) were applied to non-edge wells of a 96-well plate (CytoOne). Per condition, there were at least 6 technical replicates across a culture plate. Extended culture times of up to 48 hours required the use of distilled water instead of experimental samples in the outermost wells of the plate (highlighted in blue within Fig. 1) as a buffer for evaporation. As such, these wells were filled with 200 μL of Milli-Q distilled water, which was sufficient for measurements made to validate and evaluate the effectiveness of this adapted technique. To control for exposure to air, humidity, and temperature, each timepoint measured required a separate 96-well plate. These plates (8 in total for 8 measurements at 12-hour intervals across 4 days) were then placed in a static 37°C incubator. At the desired timepoints, a plate was removed without disturbing any pellicle (liquid-air interface) biofilm present, and media were removed via multi-channel pipette. Media were gently mixed 3 times to dislodge planktonic cells from the adhered biomass. Bacteria-containing growth media (100 μL, any extra was aspirated and disposed of) were then placed in a separate 96-well plate (CytoOne) and measured for OD600 to understand the planktonic biomass present in the non-adhered fraction of these cultures. The remaining biomass was washed 3 times with 170 μL of autoclaved Milli-Q distilled water per well then left to dry upside down for 10 minutes. Crystal Violet (CV) in ultrapure water (0.1% w/v, 170 μL per well) was applied to the adhered biomass and left covered to stain for 40 minutes. These samples were then washed 3 times with autoclaved Milli-Q distilled water and de-stained with 170 μL of 70% ethanol v/v in distilled water for 30 minutes. Finally, a 100 μL aliquot of these samples was transferred to a new 96-well plate (CytoOne) and OD595 was measured as a proxy measurement of adhered biomass (Fig. 1). This process was then repeated at each timepoint across the entire experiment, where the same CV solution, culture interval, incubator, and sample sets were used to obtain precise measurements that maintain robustness and rigor.

Figure 1: Schematic procedure for temporal measurement of biofilm.

Overnight culture of the microbe of interest in nutrient-rich media is grown to early stationary phase (12–16 hours), then diluted into media conditions of interest and aliquoted into 96-well plates. These plates (1/desired timepoint) are then incubated at 37°C, and at 12-hour intervals for 4 days, 1 plate is pulled. Each plate undergoes aspiration of the planktonic bacterial population which is then measured for optical density at 600 nm. The remaining population(s) in wells are then washed with PBS, dried, stained with CV, washed and de-stained with 70% v/v ethanol solution. The de-stained biomass is measured at optical density 595 nm.

2.4. Data analysis and statistical modelling

Presented data are the result of at least 2 biological replicates with at least 12 total technical replicates per bacterial strain and test condition. These data were analyzed in a structured manner to understand the interaction of the adhered and non-adherent biomass in cultures as a function of time. The test conditions in Fig. 2, for instance, consisted of a control and four increasing concentrations of the small molecule chelator TPEN including 1.25 μg/ml, 2.5 μg/ml, 5 μg/ml, and 10 μg/ml. Comparisons were made across these conditions using three central strategies which were conducted separately for adhered biomass (OD595) and planktonic (OD600) populations. Response feature analyses were used to avoid modeling the correlation structure of growth responses at different times within individual replicates.81 Bacterial cultures were derived from the same source, but since measurement is a terminal endpoint, samples could not be statistically matched for analysis. As such, averages of technical and biological replicates collected using the kinetic methods described in Figure 1 were randomly matched as a time course. Spaghetti plots of these time courses were then used to calculate area under the curve (AUC) for each replicate. These AUCs were used as a response variable (feature). It was compared across all conditions per figure via Kruskal-Wallis H-test with follow-up comparison of control to each of the test conditions by independent Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests. A second response variable was defined by fitting a linear model to the growth-time data from each replicate. The estimated slopes from these models were compared by Kruskal-Wallis H-test with follow-up comparison of the control condition to each test condition by independent Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests. Finally, a three-knot restricted cubic spline model was fit to each replicate using default knot locations as recommended by Harrell.82 The linear and non-linear parameter estimates from these models were compared across the control and 4 test conditions by one-way multivariate analysis of variance. This technique was then used to compare the control condition to each of the four test conditions. Wilks’ lambda statistic was used for these comparisons.83 Statistical work as performed using GraphPad Prism 9, R, and Stata v17 software, and significance is indicated on the graphs as follows: *, P ≤ 0.05; **, P ≤ 0.01; ***, P ≤ 0.001; ****, P ≤ 0.0001; and ns, not significant.84–86 All tests were with respect to two-sided alternative hypotheses.

Figure 2: Nutrient-rich media support bacterial biomass accumulation in a species- and kinetics-dependent manner.

(A and B) Measurement of accrued biomass on polystyrene 96-well flat-bottom plate as a function of time (A) and of planktonic cell density (B). (C and E) Area under the curve analyses for growth-time replicates of adhered biomass (C) and planktonic biomass (E). (D and F) These replicates were also analyzed using the slope of the growth-time curve for each replicate as the response variable of adhered biomass (D) and planktonic biomass (F). At least 2 biological and 12 technical replicates were performed for each bacterial strain. Comparisons between the strains were made by Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests. Comparisons between test and control conditions without specific notation were not significant. *** p-value <0.001

4. RESULTS

S. AUREUS AND P. AERUGINOSA ACCUMULATE BIOMASS IN DISTINCT PATTERNS.

Studies of biofilm have used different small molecules to measure biofilm formation and the cellular content of biofilm. Crystal violet (CV) is an effective tool for measurement of bacterial community formation. The original studies using CV in conjunction with harsh wash steps have been modified within the TMBL Assay to obtain more sensitive measurements of biofilm formation.78,79,87,88 There remains a gap in knowledge surrounding the application and optimization of these procedures for the evaluation of community formation across a clinically relevant time period, including a measurement of the dispersed non-adhered population as described in Fig. 1. Using the TMBL assay, S. aureus and P. aeruginosa were separately measured for their ability to form bacterial communities that adhere to tissue-culture treated polystyrene plates.

This baseline comparison of bacterial strains in a nutrient-rich in vitro environment was designed to evaluate the impact of the procedures (if any) on biofilm formation. To this effect, S. aureus communities were grown in the absence of supplementary glucose or NaCl. The results of these experiments in Fig. 2A suggest that S. aureus has regular periodic decline in biomass in the media conditions tested. By comparison, P. aeruginosa exhibits higher levels of adhered biomass, reflective of the differential binding of Crystal Violet by Gram-positive and -negative organisms. Additionally, P. aeruginosa has only a minimal reduction in biomass accumulation at 60 hours of growth. This behavior may be explained by biofilm dispersal, a genetically and biochemically complex process that is well-studied but has been difficult to quantify.3,17,89,90 Significant differences in biomass accumulation across the time-scale of 4 days (Fig. 2A) appear to to be independent of a planktonic cell population that remains largely unchanged in size across the time course (Fig. 2B). Further analysis of response variables derived from these datasets suggest that there are significant differences in the total accrued biomass detected for each of these bacteria under these nutrient-rich conditions (Fig. 2C) and that the pattern of biomass accrual over time is also different (Fig 2D and Supp. Fig. 1A and B). The planktonic populations, however, were not different from one another in their pattern of growth by either analysis, suggesting that these distinct nutrient-rich media similarly optimize the growth of planktonic S. aureus and P. aeruginosa bacteria (Fig. 2E and F). These differences were maintained in three-knot restricted cubic spline models of population behavior of adhered and non-adhered biomass (Supp. Fig. 1A and B). Kinetic measurement via the TMBL Assay suggest there are discrete differences in biofilm formation of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. Additionally, these data suggest that across bacterial species, the TMBL Assay provides sensitive measurements that are reproducible and that can be analyzed by the established statistical framework.

ZINC SEQUESTRATION MODIFIES BIOFILM POPULATION DYNAMICS.

To modify the growth environment and assess its impact on biofilm formation of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa, TPEN was applied to cultures in a nutrient-rich environment. TPEN is a membrane permeable zinc chelator with a Kd of 0.4 * 10−15 M that can also bind iron, manganese, and copper with lower affinities. When increasing concentrations of TPEN are applied to S. aureus cultures (Fig. 3), a dose-dependent effect is seen at low concentrations which limits biofilm formation and at high concentrations which increases overall biofilm formation and decreases planktonic growth (Fig. 3A and B). These differences are captured by all sets of response-variable analyses (Fig. 3C, D, E, and F, and Supp. Fig. 2) and suggest that this assay design is sensitive for differences in biomass in the adhered and non-adhered fractions of cultures over time. This informs new biology as well, suggesting that the impact of TPEN and zinc sequestration on S. aureus may extend to biofilm formation, particularly at early time points

Figure 3: Staphylococcus aureus biomass accrual and planktonic growth are significantly affected by bioavailable zinc concentration in the growth environment.

(A and B) Measurement of accrued biomass on polystyrene 96-well flat-bottom plate as a function of time (A) and of planktonic cell density (B) in nutrient rich media containing increasing concentrations of small molecule chelator TPEN. (C and E) Area under the curve analyses show the area under the curve for growth-time replicates of adhered biomass (C) and planktonic biomass (E). (D and F) These replicates were also analyzed using the slope of the growth-time curve for each replicate as the response variable of adhered biomass (D) and planktonic biomass (F). Two biological and twelve technical replicates were used for each concentration of TPEN. All comparisons made by Kruskal-Wallis Rank Sum test for overall difference among all concentrations with follow-up Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests comparing control replicates to replicates at each TPEN concentration. Comparisons between test and control conditions without specific notation were not significant. * p<0.05 ** p<0.01 *** p<0.001

A similar set of experiments was conducted in P. aeruginosa (Fig. 4A and B) and suggests that despite a different organism and set of media conditions, the designed method is optimized to temporally resolve differences in biofilm formation (Fig. 4C and E). In Fig. 4C, there appear to be differences in area under the curve and therefore in the total adhered biomass over the experiment. However, Fig. 4D suggests that these differences do not impact the overall pattern of biofilm formation. Further analysis in Supp. Fig. 2 and 3 supports these findings and the importance of 10 μg/mL of TPEN as a critical concentration for observation of differences in biofilm quantification of S. aureus and P. aeruginosa. Use of kinetic measurements to evaluate biofilm formation revealed the impact of zinc chelation on biofilm formation, where in S. aureus zinc depletion results in increased biofilm formation and in P. aeruginosa the same stimulus results in increased biomass over time without a change in the pattern of biofilm formation. Further, these results suggest that the TMBL Assay is sensitive to changes in bacterial species and availability of micronutrients. This sensitivity is accomplished in a 96-well format, supporting future high-throughput study and screening of environmental conditions, bacterial strains, and bacterial species of interest.

Figure 4: Pseudomonas aeruginosa biomass accrual and planktonic growth are significantly affected by bioavailable zinc concentration in the growth environment.

(A and B) Measurement of accrued biomass on polystyrene 96-well flat-bottom plate as a function of time (A) and of planktonic cell density (B) in nutrient rich media containing increasing concentrations of small molecule chelator TPEN. (C and E) Area under the curve analyses show the area under the curve for growth-time replicates of adhered biomass (C) and planktonic biomass (E). (D and F) These replicates were also analyzed using the slope of the growth-time curve for each replicate as the response variable of adhered biomass (D) and planktonic biomass (F). Two biological and twelve technical replicates were used for each concentration of TPEN. All comparisons made by Kruskal-Wallis Rank Sum test for overall difference among all concentrations with follow-up Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests comparing control replicates to replicates at each TPEN concentration. Comparisons between test and control conditions without specific notation were not significant. * p<0.05 ** p<0.01 *** p<0.001

S100 PROTEINS MODULATE BIOFILM FORMATION AS A FUNCTION OF METAL-BINDING AND ANTI-BACTERIAL ACTIVITY

To understand biofilm formation in a more translational manner, assays for biofilm-centered discovery must be adaptable to conditions that progressively approch in vivo conditions. Experiments interrogating nutritional immunity have been used to understand the host-microbe interface and present a model platform for understanding the effectiveness of the proposed methods32,34,40,44. To examine the impact of S100 proteins, specifically CP, on biofilm population dynamics, CP was incorporated into the growth medium (Fig. 5). To control for the metal-binding and antibacterial properties of CP, as well as the impact of protein and the CP buffer on the development of S. aureus biofilm over time, these experiments were conducted in parallel with cultures enriched with: (i) a nutrient metal binding deficient CP mutant (CP site1-site2 mutant), (ii) a corresponding mutant of S100A7 without antibacterial activity (S100A7 Zn-binding mutant), (iii) S100A12, which binds zinc and other nutrient metals, and (iv) a non-bactericidal S100A2 mutant with substitution of its zinc binding residues (S100A2 Zn-binding mutant).68–70,91,92 Without metal sequestration or associated bactericidal activity, S100 proteins increase adherent biomass and planktonic cell density (Fig. 5A and B). However, CP and S100A12 bind zinc, and consistent with data in Fig. 3, also result in significantly less adherent and non-adherent biomass growth over time (Fig. 5C, D, E, and F). Three-knot modelling of biofilm development under these conditions suggest that these populations react to nutritional immune factors in drastically different ways dependent on the bactericidal and metal-binding activity of the protein of interest (Supp. Fig. 4). These results suggest that when treated with S100 proteins, there are significant and detectable changes in biofilm formation kinetics and that these differences are correlated with available zinc concentration using the TMBL assay. These analyses also present the modular and adaptable nature of this assay to non-standard media conditions, allowing for screening of the impact of diverse compounds on biofilm.

Figure 5: Staphylococcus aureus biomass and planktonic growth are responsive to nutritional immune factor calprotectin and additional metal-binding S100 host proteins.

(A and B) Measurement of accrued biomass on polystyrene 96-well flat-bottom plate as a function of time (A) and of planktonic cell density (B) in media with applied S100 proteins and zinc-binding defective mutants. (C and E) Area under the curve analyses show the area under the curve for growth-time replicates of adhered biomass (C) and planktonic biomass (E). (D and F) These replicates were also analyzed using the slope of the growth-time curve for each replicate as the response variable of adhered biomass (D) and planktonic biomass (F). Two biological and twelve technical replicates were used for each S100 protein. All comparisons made by Kruskal-Wallis Rank Sum test for overall difference among all concentrations with follow-up Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests comparing CP replicates to replicates of each S100 protein. Comparisons between test and control conditions without specific notation were not significant. * p<0.05 ** p<0.01 *** p<0.001

ALTERATIONS IN METAL AVAILABILITY REVEALS DIFFERENCES IN BIOFILM DYNAMICS

TMBL is highly adaptable, including to nutrient-restricted conditions that recapitulate particular cellular environments. As an extension of this idea, S. aureus was grown in phenol red-free RPMI +1% w/v casamino acids that had been depleted of metal by treatment with Chelex. This metal-depleted media was then selectively supplemented with known concentrations of specific metals, including test conditions with single-metal exclusion (25 μM zinc, 100 μM calcium, 1 μM iron, 25 μM manganese, and 2 mM magnesium). This array of media conditions were then innoculated as described in Section 2.3 where the adhered and non-adhered biomass was measured in Fig. 6A and B. By selectively replenishing metals to a metal-poor media, these data demonstrate that low calcium leads to an increase in biomass accrual over time. Further, this difference changes in magnitude as a function of time. An assay that only captured biofilm behavior at 72 hours, for instance, would be unlikely to discover the impact of calcium on biofilm formation explored in Fig. 6A, C, and D. These results support the need for kinetic measurement in the study of biofilms and support prior work investigating the essential role of micronutrient metals in bacterial proliferation32,55–57,60–62,64,93–95. Additionally, modelling of these data suggest that despite large differences in the magnitude of biomass accrued in a low calcium condition, the dynamics of that population are not statistically different from a metal-replete media (Supp. Fig. 5). Bulk modification of metal availability by limitation suggests that metal bioavailability facilitates changes in biofilm formation that can be measured specifically as the result of kinetic measurement by TMBL.

Figure 6: Staphylococcus aureus biomass and planktonic growth are significantly affected by individual metal starvation.

(A and B) Measurement of accrued biomass on polystyrene 96-well flat-bottom plate as a function of time (A) and of planktonic cell density (B) in nutrient-poor (relative to TSB and LB) media RPMI which had been depleted of metals by Chelex. Aliquots were then supplemented back with metals at a known concentration sufficient for S. aureus growth (denoted as Full Addback on Fig. 6A–F). (C and E) Area under the curve analyses show the area under the curve for growth-time replicates of adhered biomass (C) and planktonic biomass (E). (D and F) These replicates were also analyzed using the slope of the growth-time curve for each replicate as the response variable of adhered biomass (D) and planktonic biomass (F). Two biological and twelve technical replicates were used for each media condition. All comparisons made by Kruskal-Wallis Rank Sum test for overall difference among all concentrations with follow-up Wilcoxon Rank Sum tests comparing Full Addback replicates to replicates of each metal depleted condition. Comparisons between test and control conditions without specific notation were not significant. * p<0.05 ** p<0.01 *** p<0.001

5. DISCUSSION

The experimental method (TMBL) proposed within this work aimed to test the hypothesis that time is a central variable that can be evaluated mathematically in evaluating biofilm and adherent bacterial communities. Further, experiments were performed to modify the bacteria (Fig. 2), media (Fig. 3, 4, 5, and 6), nutritional environment (Fig. 3–6), and presence of innate immune factors (Fig. 5) to isolate the impact of the method on experimental outcomes. To complement this approach, these data were compared as a function of multiple orthogonal statistical approaches that include resonse variable analyses of area under the curve, linear modelling, and three-knot restricted cubic spline modelling (Supp. Fig. 1–5). The results suggest that changes to all evaluated variables have impacts on biomass accumulation and population dynamics of bacterial communities, and that interrogation of biofilm formation of clinically relevant species benefits from kinetic analysis. These analyses were reliant on the increased granularity of TMBL kinetic data, where analysis by area under the curve, linear modelling, and cubic spline modelling each probe a different dimension of population dynamics and inform comparison of the total accrued biomass/planktonic cell density and the behavior of these populations over time. This adds a critical feature of analysis to discovery-based applications of research into biofilm formation and dispersal and does so in a cost-effective and high-throughput manner that allows for screening of differences in adherence, biofilm formation, and dispersal. Further, this method is highly adaptable to different model systems and downstream assays of interest, and can be applied to investigate a range of variables. This adaptability includes vast differences in culture conditions and organism. Future work could explore separate fractions of planktonic cells and adhered cells and could further sub-divide these fractions by cellular and non-cellular content for transcriptomic, metabolomic, genetic, and/or biochemcial analysis. This work suggests that the use of kinetic experimentation, modelling, and implementation of the described statistical framework defines a robust and reproducible approach for the basic evaluation of biofilm. Futher study into biomass accumulation and biofilm formation may consider time-dependence of the TMBL Assay for screening of conditions of interest and for generating scientific hypotheses, which can increase the accesibility of and stimulate scientific discovery within the study of biofilm formation and maintenance.

Supplementary Material

HIGHLIGHTS.

Limited techniques exist for studying and analyzing the time-dependence of biofilm.

Interrogating biofilm kinetics with TMBL adds statistical power to biofilm experimentation.

TMBL’s semi-continuous measurements capture differences in biofilm dynamics.

Statistical models support time-dependent analysis as robust and reproducible.

ACKNOWLEDGEMENTS

ROLE OF THE FUNDING SOURCE

Research reported in this publication was supported by NIGMS and NCATS of the National Institutes of Health under award number T32GM007347 to KTE, R01AI150701, R01AI138581, R01145992 to EPS, R0101171 to EPS and WJC, and UL1 TR000445.

ABBREVIATIONS

- CV

Crystal Violet

- TMBL

Temporal Modelling of the Biofilm Lifecycle

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Álvarez A et al. Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus in Hospitals: Latest Trends and Treatments Based on Bacteriophages. Journal of Clinical Microbiology 57 (2019). 10.1128/jcm.01006-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kaya E et al. Planktonic and Biofilm-Associated Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus epidermidis Elicit Differential Human Peripheral Blood Cell Responses. Microorganisms 9 (2021). 10.3390/microorganisms9091846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lister JL & Horswill AR Staphylococcus aureus biofilms: recent developments in biofilm dispersal. Frontiers in Cellular and Infection Microbiology. 4 (2014). 10.3389/fcimb.2014.00178 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Parastan R, Kargar M, Solhjoo K & Kafilzadeh F Staphylococcus aureus biofilms: Structures, antibiotic resistance, inhibition, and vaccines. Gene Reports. 20, 100739 (2020). 10.1016/j.genrep.2020.100739 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lewis K Riddle of biofilm resistance. Antimicrob Agents Chemother 45, 999–1007 (2001). 10.1128/aac.45.4.999-1007.2001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Donlan RM Biofilm formation: a clinically relevant microbiological process. Clin Infect Dis 33, 1387–1392 (2001). 10.1086/322972 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Sauer K et al. The biofilm life cycle: expanding the conceptual model of biofilm formation. Nature Reviews Microbiology 20, 608–620 (2022). 10.1038/s41579-022-00767-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cegelski L Bottom-up and top-down solid-state NMR approaches for bacterial biofilm matrix composition. Journal of Magnetic Resonance 253, 91–97 (2015). 10.1016/j.jmr.2015.01.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cruz CD, Shah S & Tammela P Defining conditions for biofilm inhibition and eradication assays for Gram-positive clinical reference strains. BMC Microbiology 18 (2018). 10.1186/s12866-018-1321-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gélinas M, Museau L, Milot A, Beauregard PB & Zhang K The de novo Purine Biosynthesis Pathway Is the Only Commonly Regulated Cellular Pathway during Biofilm Formation in TSB-Based Medium in Staphylococcus aureus and Enterococcus faecalis. Microbiology Spectrum. 9 (2021). 10.1128/spectrum.00804-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grande R et al. Temporal expression of agrB, cidA, and alsS in the early development of Staphylococcus aureus UAMS-1 biofilm formation and the structural role of extracellular DNA and carbohydrates. Pathogens and Disease 70, 414–422 (2014). 10.1111/2049-632x.12158 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kaplan JB et al. Low Levels of β-Lactam Antibiotics Induce Extracellular DNA Release and Biofilm Formation in Staphylococcus aureus. MBio. 3, e001982012). 10.1128/mbio.00198-12 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mann EE et al. Modulation of eDNA Release and Degradation Affects Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm Maturation. PLoS ONE 4, e5822 (2009). 10.1371/journal.pone.0005822 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Thieme L et al. MBEC Versus MBIC: the Lack of Differentiation between Biofilm Reducing and Inhibitory Effects as a Current Problem in Biofilm Methodology. Biological Procedures Online 21 (2019). 10.1186/s12575-019-0106-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wake N et al. Temporal dynamics of bacterial microbiota in the human oral cavity determined using an in situ model of dental biofilms. npj Biofilms and Microbiomes 2, 16018 (2016). 10.1038/npjbiofilms.2016.18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thurlow LR et al. Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms Prevent Macrophage Phagocytosis and Attenuate Inflammation In Vivo. The Journal of Immunology 186, 6585–6596 (2011). 10.4049/jimmunol.1002794 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Boles BR & Horswill AR agr-Mediated Dispersal of Staphylococcus aureus Biofilms. PLoS Pathogens 4, e1000052 (2008). 10.1371/journal.ppat.1000052 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Moormeier DE et al. Use of Microfluidic Technology To Analyze Gene Expression during Staphylococcus aureus Biofilm Formation Reveals Distinct Physiological Niches. Applied and Environmental Microbiology 79, 3413–3424 (2013). 10.1128/aem.00395-13 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Paula AJ, Hwang G & Koo H Dynamics of bacterial population growth in biofilms resemble spatial and structural aspects of urbanization. Nature Communications 11, 1354 (2020). 10.1038/s41467-020-15165-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Coombs GW, Daley DA, Shoby P & Mowlaboccus S Australian Group on Antimicrobial Resistance (AGAR) Australian Staphylococcus aureus Surveillance Outcome Program (ASSOP) - Bloodstream Annual Report 2021. Communicable Diseases Intelligence 46 (2022). 10.33321/cdi.2022.46.76 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Liu C et al. Clinical Practice Guidelines by the Infectious Diseases Society of America for the Treatment of Methicillin-Resistant Staphylococcus aureus Infections in Adults and Children. Clinical Infectious Diseases 52, e18–e55 (2011). 10.1093/cid/ciq146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Lowy FD Antimicrobial resistance: the example of Staphylococcus aureus. J Clin Invest 111, 1265–1273 (2003). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ikuta KS et al. Global mortality associated with 33 bacterial pathogens in 2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 400, 2221–2248 (2022). 10.1016/s0140-6736(22)02185-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Murray CJ et al. Global burden of bacterial antimicrobial resistance in 2019: a systematic analysis. The Lancet 399, 629–655 (2022). 10.1016/s0140-6736(21)02724-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bisht K, Moore JL, Caprioli RM, Skaar EP & Wakeman CA Impact of temperature-dependent phage expression on Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. npj Biofilms and Microbiomes 7 (2021). 10.1038/s41522-021-00194-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Das T & Manefield M Pyocyanin Promotes Extracellular DNA Release in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. PLoS ONE 7, e46718 (2012). 10.1371/journal.pone.0046718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Harrison J, Turner R & Ceri H Persister cells, the biofilm matrix and tolerance to metal cations in biofilm and planktonic Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environ Microbiol 7, 981–994 (2005). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hynen AL et al. Multiple holins contribute to extracellular DNA release in Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilms. Microbiology 167 (2021). 10.1099/mic.0.000990 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Kuchma SL, Connolly JP & O’Toole GA A Three-Component Regulatory System Regulates Biofilm Maturation and Type III Secretion in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of Bacteriology 187, 1441–1454 (2005). 10.1128/jb.187.4.1441-1454.2005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Pasqua M et al. Ferric Uptake Regulator Fur Is Conditionally Essential in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Journal of Bacteriology 199 (2017). 10.1128/jb.00472-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Sass G et al. Studies of Pseudomonas aeruginosa Mutants Indicate Pyoverdine as the Central Factor in Inhibition of Aspergillus fumigatus Biofilm. Journal of Bacteriology 200 (2018). 10.1128/jb.00345-17 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wakeman CA et al. The innate immune protein calprotectin promotes Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus interaction. Nature Communications 7, 11951 (2016). 10.1038/ncomms11951 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Wilson MJ & Lamont IL Characterization of an ECF Sigma Factor Protein from Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Biochemical and Biophysical Research Communications. 273, 578–583 (2000). 10.1006/bbrc.2000.2996 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Zygiel EM, Obisesan AO, Nelson CE, Oglesby AG & Nolan EM Heme protects Pseudomonas aeruginosa and Staphylococcus aureus from calprotectin-induced iron starvation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 296, 100160 (2021). 10.1074/jbc.ra120.015975 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Bell SC et al. The future of cystic fibrosis care: a global perspective. The Lancet. 8, 65–124 (2020). 10.1016/S2213-2600(19)30337-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Reasoner SA et al. Urinary tract infections in cystic fibrosis patients. Journal of Cystic Fibrosis 21, e1–e4 (2022). 10.1016/j.jcf.2021.07.005 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Filkins LM et al. Coculture of Staphylococcus aureus with Pseudomonas aeruginosa Drives S. aureus towards Fermentative Metabolism and Reduced Viability in a Cystic Fibrosis Model. Journal of Bacteriology 197, 2252–2264 (2015). 10.1128/jb.00059-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Romaniuk JAH & Cegelski L Bacterial cell wall composition and the influence of antibiotics by cell-wall and whole-cell NMR. Philosophical Transactions of the Royal Society B: Biological Sciences 370, 20150024 (2015). 10.1098/rstb.2015.0024 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Abedon ST, Danis-Wlodarczyk KM, Wozniak DJ & Sullivan MB Improving Phage-Biofilm In Vitro Experimentation. Viruses 13, 1175 (2021). 10.3390/v13061175 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Haque M, Mosharaf K, Haque A, Tanvir Z & Alam K Biofilm Formation, Production of Matrix Compounds and Biosorption of Copper, Nickel and Lead by Different Bacterial Strains. Front. Microbiol (2021). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Macia MD, Rojo-Molinero E & Oliver A Antimicrobial susceptibility testing in biofilm-growing bacteria. Clinical Microbiology and Infection. 20, 981–990 (2014). 10.1111/1469-069-0691.12651 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Syed A et al. Heavy Metals Induced Modulations in Growth, Physiology, Cellular Viability, and Biofilm Formation of an Identified Bacterial Isolate. ACS Omega 6, 25076–25088 (2021). 10.1021/acsomega.1c04396 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Schilcher K & Horswill AR Staphylococcal Biofilm Development: Structure, Regulation, and Treatment Strategies. Microbiology and Molecular Biology Reviews. 84 (2020). 10.1128/mmbr.00026-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paulander W et al. The agr quorum sensing system in Staphylococcus aureus cells mediates death of sub-population. BMC Research Notes 11 (2018). 10.1186/s13104-018-3600-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Rehder D et al. (MIT Press, Cambridge (MA), 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 46.Imperi F, Tiburzi F, Fimia GM & Visca P Transcriptional control of the pvdS iron starvation sigma factor gene by the master regulator of sulfur metabolism CysB in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Environmental Microbiology (2010). 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2010.02210.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Vasil ML How we learnt about iron acquisition in Pseudomonas aeruginosa: a series of very fortunate events. BioMetals 20, 587–601 (2007). 10.1007/s10534-006-9067-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Banin E, Vasil ML & Greenberg EP Iron and Pseudomonas aeruginosa biofilm formation. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 102, 11076–11081 (2005). 10.1073/pnas.0504266102 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Chien Y-T, Manna AC, Projan SJ & Cheung AL SarA, a Global Regulator of Virulence Determinants in Staphylococcus aureus, Binds to a Conserved Motif Essential for sar-dependent Gene Regulation. Journal of Biological Chemistry 274, 37169–37176 (1999). 10.1074/jbc.274.52.37169 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Seyedmohammad S et al. Structural model of FeoB, the iron transporter from Pseudomonas aeruginosa, predicts a cysteine lined, GTP-gated pore. Bioscience Reports. 36, e00322 (2016). 10.1042/bsr20160046 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Price-Whelan A, Dietrich LEP & Newman DK Pyocyanin Alters Redox Homeostasis and Carbon Flux through Central Metabolic Pathways in Pseudomonas aeruginosa PA14. Journal of Bacteriology 189, 6372–6381 (2007). 10.1128/jb.00505-07 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Shin M et al. Characterization of an Antibacterial Agent Targeting Ferrous Iron Transport Protein FeoB against Staphylococcus aureus and Gram-Positive Bacteria. ACS Chemical Biology. 16, 136–149 (2021). 10.1021/acschembio.0c00842 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Lau CKY, Krewulak KD, Vogel HJ & Bitter W Bacterial ferrous iron transport: the Feo system. FEMS Microbiology Reviews. 40, 273–298 (2016). 10.1093/femsre/fuv049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Hood MI & Skaar EP Nutritional immunity: transition metals at the pathogen–host interface. Nature Reviews Microbiology 10, 525–537 (2012). 10.1038/nrmicro2836 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Kehl-Fie TE & Skaar EP Nutritional immunity beyond iron: a role for manganese and zinc. Current Opinion in Chemical Biology 14, 218–224 (2010). 10.1016/j.cbpa.2009.11.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Murdoch CC & Skaar EP Nutritional immunity: the battle for nutrient metals at the host–pathogen interface. Nature Reviews Microbiology 20, 657–670 (2022). 10.1038/s41579-022-00745-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Zackular JP, Chazin WJ & Skaar EP Nutritional Immunity: S100 Proteins at the Host-Pathogen Interface. Journal of Biological Chemistry 290, 18991–18998 (2015). 10.1074/jbc.r115.645085 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Barwinska-Sendra A & Waldron KJ The Role of Intermetal Competition and Mis-Metalation in Metal Toxicity. Microbiology of Metal Ions 70, 315–379 (2017). 10.1016/bs.ampbs.2017.01.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kozlyuk N et al. in Methods in Molecular Biology 275–290 (Springer; New York, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 60.Cho H et al. Calprotectin Increases the Activity of the SaeRS Two Component System and Murine Mortality during Staphylococcus aureus Infections. PLOS Pathogens 11, e1005026 (2015). 10.1371/journal.ppat.1005026 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Damo SM et al. Molecular basis for manganese sequestration by calprotectin and roles in the innate immune response to invading bacterial pathogens. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences 110, 3841–3846 (2013). 10.1073/pnas.1220341110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Kehl-Fie E, Thomas et al. Nutrient Metal Sequestration by Calprotectin Inhibits Bacterial Superoxide Defense, Enhancing Neutrophil Killing of Staphylococcus aureus. Cell Host & Microbe 10, 158–164 (2011). 10.1016/j.chom.2011.07.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Jiang H et al. Ferrous iron–activatable drug conjugate achieves potent MAPK blockade in KRAS - driven tumors. The Journal of Experimental Medicine. 219 (2022). 10.1084/jem.20210739 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Cassat JE & Skaar EP Metal ion acquisition in Staphylococcus aureus: overcoming nutritional immunity. Seminars in Immunopathology 34, 215–235 (2012). 10.1007/s00281-011-0294-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Lonergan ZR et al. An Acinetobacter baumannii, Zinc-Regulated Peptidase Maintains Cell Wall Integrity during Immune-Mediated Nutrient Sequestration. Cell Reports 26, 2009–2018.e2006 (2019). 10.1016/j.celrep.2019.01.089 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Lonergan ZR & Skaar EP Nutrient Zinc at the Host–Pathogen Interface. Trends in Biochemical Sciences. 44, 1041–1056 (2019). 10.1016/j.tibs.2019.06.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Mcdevitt CA et al. A Molecular Mechanism for Bacterial Susceptibility to Zinc. PLoS Pathogens 7, e1002357 (2011). 10.1371/journal.ppat.1002357 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gilston BA, Skaar EP & Chazin WJ Binding of transition metals to S100 proteins. Science China. Life Sciences 59, 792–801 (2016). 10.1007/s11427-016-5088-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Goyette J & Geczy CL Inflammation-associated S100 proteins: new mechanisms that regulate function. Amino Acids 41, 821–842 (2011). 10.1007/s00726-010-0528-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Fritz G, Botelho HM, Morozova-Roche LA & Gomes CM Natural and amyloid self-assembly of S100 proteins: structural basis of functional diversity. The FEBS journal 277, 4578–4590 (2010). 10.1111/j.1742-4658.2010.07887.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Hoonsik Cho D-WJ, Liu Qian, Yeo Won-Sik, Vogl Thomas, Skaar Eric P, Chazin Walter J, Bae Taeok. Calprotectin Increases the Activity of the SaeRS Two Component System and Murine Mortality during Staphylococcus aureus Infections. PLoS Pathogens 11, e1005026 (2015). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Shank JM et al. The Host Antimicrobial Protein Calgranulin C Participates in the Control of Campylobacter jejuni Growth via Zinc Sequestration. Infect Immun 86 (2018). 10.1128/iai.00234-18 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Haley KP et al. The Human Antimicrobial Protein Calgranulin C Participates in Control of Helicobacter pylori Growth and Regulation of Virulence. Infect Immun 83, 2944–2956 (2015). 10.1128/iai.00544-15 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Moroz OV et al. Structure of the human S100A12-copper complex: implications for host-parasite defence. Acta Crystallogr D Biol Crystallogr 59, 859–867 (2003). 10.1107/s0907444903004700 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Ravasi T et al. Probing the S100 protein family through genomic and functional analysis. Genomics 84, 10–22 (2004). 10.1016/j.ygeno.2004.02.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Randazzo A, Acklin C, Schäfer BW, Heizmann CW & Chazin WJ Structural insight into human Zn(2+)-bound S100A2 from NMR and homology modeling. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 288, 462–467 (2001). 10.1006/bbrc.2001.5793 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Flemming H-C & Wingender J The biofilm matrix. Nature Reviews Microbiology 8, 623–633 (2010). 10.1038/nrmicro2415 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.O’Toole GA Microtiter Dish Biofilm Formation Assay. Journal of Visualized Experiments (2011). 10.3791/2437 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Syal K Novel Method for Quantitative Estimation of Biofilms. Current Microbiology 74, 1194–1199 (2017). 10.1007/s00284-017-1304-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Maurakis S et al. The novel interaction between Neisseria gonorrhoeae TdfJ and human S100A7 allows gonococci to subvert host zinc restriction. PLOS Pathogens 15, e1007937 (2019). 10.1371/journal.ppat.1007937 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dupont WD Statistical Modeling for Biomedical Researchers: A Simple Introduction to the Analysis of Complex Data. 2 edn, (Cambridge University Press, 2009). [Google Scholar]

- 82.Harrell FE Regression Modeling Strategies: With Applications to Linear Models, Logistic and Ordinal Regression, and Survival Analysis. (Springer International Publishing, 2015). [Google Scholar]

- 83.Grey DR Multivariate analysis, by Mardia KV, Kent JT and Bibby JM. Pp 522. £14·60. 1979. ISBN 0 12 471252 5 (Academic Press; ). The Mathematical Gazette 65, 75–76 (1981). 10.2307/3617970 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Team, R. C. (R Foundation for Statistical Computing, Vienna, Austria, 2018). [Google Scholar]

- 85.StataCorp. (StataCorp LLC, College Station, TX, 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 86.Windows, G. P. v. f. (GraphPad Software, San Diego, California USA: ). [Google Scholar]

- 87.Thibeaux R, Kainiu M & Goarant C in Methods in Molecular Biology 207–214 (Springer; US, 2020). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Haney EF, Trimble MJ & Hancock REW Microtiter plate assays to assess antibiofilm activity against bacteria. Nature Protocols 16, 2615–2632 (2021). 10.1038/s41596-021-00515-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Toledo-Silva B et al. Bovine-associated non-aureus staphylococci suppress Staphylococcus aureus biofilm dispersal in vitro yet not through agr regulation. Veterinary Research 52 (2021). 10.1186/s13567-021-00985-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Caro-Astorga J et al. Biofilm formation displays intrinsic offensive and defensive features of Bacillus cereus. NPJ Biofilms and Microbiomes 6, 3–3 (2020). 10.1038/s41522-019-0112-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Moroz OV, Dodson GG, Wilson KS, Lukanidin E & Bronstein IB Multiple structural states of S100A12: A key to its functional diversity. Microscopy Research and Technique 60, 581–592 (2003). 10.1002/jemt.10300 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Roth J, Vogl T, Sorg C & Sunderkötter C Phagocyte-specific S100 proteins: a novel group of proinflammatory molecules. Trends in Immunology 24, 155–158 (2003). 10.1016/S1471-4906(03)00062-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Monteith AJ & Skaar EP The impact of metal availability on immune function during infection. Trends in Endocrinology and Metabolism 32, 916–928 (2021). 10.1016/j.tem.2021.08.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Sheldon JR & Skaar EP Metals as phagocyte antimicrobial effectors. Current Opinion in Immunology. 60, 1–9 (2019). 10.1016/j.coi.2019.04.002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Palmer LD & Skaar EP Transition Metals and Virulence in Bacteria. Annual Review of Genetics 50, 67–91 (2016). 10.1146/annurev-genet-120215-035146 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.