Summary

Fertilization is a fundamental process in sexual reproduction during which gametes fuse to combine their genetic material and start the next generation in their life cycle. Fertilization involves species-specific recognition, adhesion, and fusion between the gametes 1,2. In mammals and other model species, some proteins are known to be required for gamete interactions and have been validated with loss-of-function fertility phenotypes 3,4. Yet, the molecular basis of sperm-egg interaction is not well understood. In a forward genetic screen for fertility mutants in Caenorhabditis elegans, we identified spe-51. Mutant worms make sperm that are unable to fertilize the oocyte but otherwise normal by all available measurements. The spe-51 gene encodes a secreted protein that includes an immunoglobulin (Ig)-like domain and a hydrophobic sequence of amino acids. The SPE-51 protein acts cell-autonomously and localizes to the surface of the spermatozoa. We further show that the gene product of the mammalian sperm function gene Sof1 is likewise secreted. This is the first example of a secreted protein required for the interactions between the sperm and egg with genetic validation for a specific function in fertilization in C. elegans (also see Krauchunas et al. on spe-36). This is also the first experimental evidence that mammalian SOF1 is secreted. Our analyses of these genes begin to build a paradigm for sperm-secreted or reproductive tract-secreted proteins that coat the sperm surface and influence their survival, motility, and/or the ability to fertilize the egg.

Keywords: fertilization, fertilization synapse, sperm, oocyte, secreted protein, Immunoglobulin, gamete interaction, C. elegans

eTOC Blurb

Mei et al. present a secreted Immunoglobulin superfamily protein SPE-51 that is on the sperm surface and required for the sperm to fertilize the eggs. In their secretion assay, the mammalian fertilization molecule SOF1 is also secreted. This work highlights the role of secreted molecules in mediating interactions between the sperm and egg.

Results

spe-51 mutants are severely subfertile with a sperm specific fertility defect

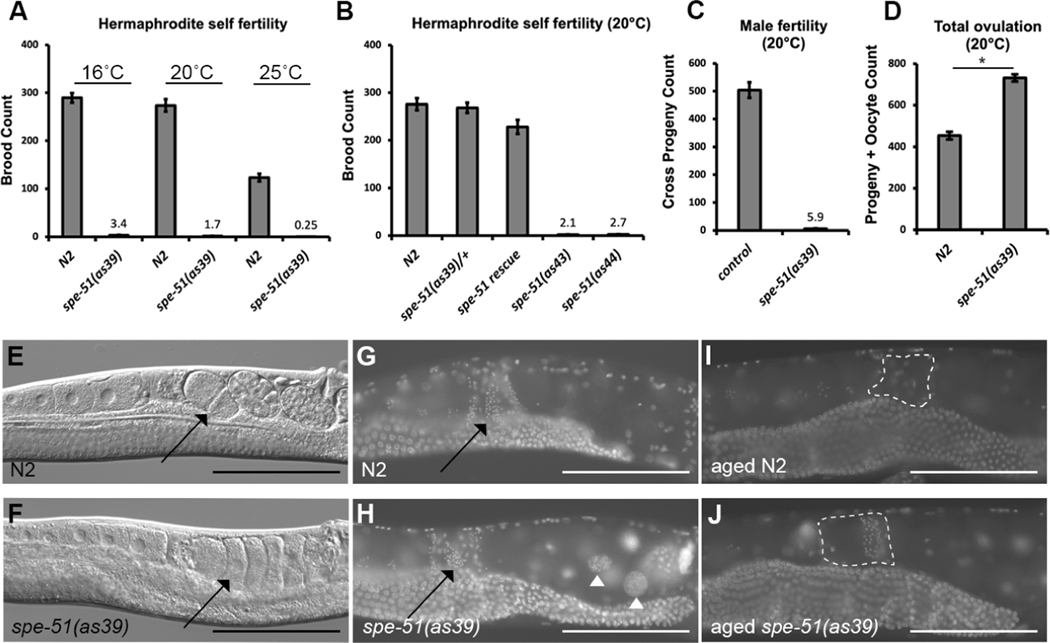

Mutant spe-51(as39) hermaphrodites lay unfertilized eggs, occasionally producing one or two rather than hundreds of progeny (Figure 1). Fertility in the worm is inherently temperature-dependent, but the spe-51(as39) mutant hermaphrodites are severely subfertile at all culture temperatures (Figure 1A). Heterozygous animals are fully fertile (Figure 1B) suggesting that the mutation is recessive for fertility. When mutant hermaphrodites are mated with wild-type males, they can produce progeny (406.2±12.0). To evaluate male fertility, mutant spe-51(as39) males were mated with either fem-1(hc17) or dpy-5(e61) hermaphrodites. The fem-1 mutants cannot produce self-sperm thus any live progeny would be cross progeny sired by males. The dpy-5 mutants are morphologically dumpy, and the mutation is recessive, so we can distinguish cross progeny. We saw that while control males produce ~500 progeny, spe-51(as39) males only produce 5.9(±1.2) progeny with fem-1 mutants (Figure 1C). Similar results were obtained when we mated mutant males with dpy-5 hermaphrodites (Figure 2J). Thus, spe-51 is required for fertility in both hermaphrodites and males.

Figure 1. spe-51(as39) phenotypes.

A. Progeny counts for N2 and spe-51(as39) hermaphrodites at different culture temperatures. For all groups from left to right, sample sizes (number of worms) are: N=18, 19, 22, 30, 19, and 20. B. Progeny count at 20 °C. Samples sizes from left to right are: N=17, 20, 19 19, and 20. C. Male fertility as measured by crossing mutant spe-51(as39);him-5(e1490) males with fem-1(hc17) hermaphrodites. Age-matched him-5(e1490) males were used as controls. N=15 for N2, and N=17 for spe-51(as39). D. Numbers of all the progeny and oocytes throughout the whole laying period. Horizontal line and * indicate statistically significant difference between the two groups (t-test, p<0.0001). N=22 for N2 and N=16 for spe-51(as39). E-F. DIC imaging of the worm. Black arrows point to embryos or unfertilized oocytes in the uterus. G-J. DAPI staining of hermaphrodites. G-H, young adults; I-J, 4 days old adults. Black arrows in G and H point to sperm in the spermatheca. Black arrowheads in H point to endomitotic nuclei in the mutant. White dashed circles show the spermathecae in I and J. For A-D, Data are presented as mean ± SEM.

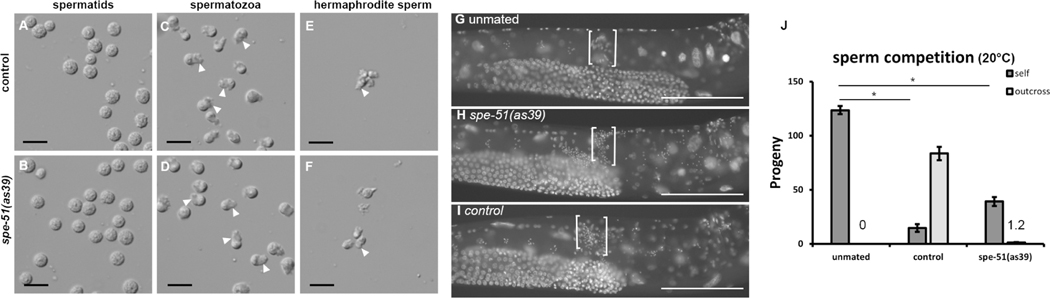

Figure 2. Sperm development in spe-51(as39) mutants.

In this figure, all spe-51(as39) males were in the him-5(e1490) background and age matched him-5(1490) males were used as controls. Spermatids are dissected from control or spe-51(as39) males. Spermatozoa are activated in vitro by Pronase. A and B. Control and spe-51 mutant male spermatids, respectively. C and D. Control and spe-51 mutant spermatozoa activated by Pronase in vitro, respectively. E-F. self-sperm dissected from hermaphrodites. In C-F, white arrowheads mark the pseudopods of activated sperm. Scale bars in A-F represent 10 μm. G-I. DAPI stained fem-1(hc17) hermaphrodites. White brackets show the location of the spermathecae. Scale bars represent 50 μm. J. sperm competition. Progeny count of mated and unmated dpy-5(e61) hermaphrodites with control males or spe-51(as39) males. Data are presented as mean ± SEM. Horizontal lines indicate comparison groups and stars (*) indicate a statistically significant difference (p<0.01, one-way ANOVA). The number of self-progeny (Dpy) are significantly lower in hermaphrodites mated with either the control or spe-51(as39) males compared to unmated worms. Sample sizes from left to right are: N=27, 27, 24, 24, 27 and 27.

Adult worms of both sexes displayed no other mutant phenotypes than sperm specific fertility defects. The uteri of mutant hermaphrodites are filled with unshelled eggs (Figure 1E–F, arrow) that had contacted and passed sperm in the spermatheca. The morphology of the gonad looks normal in the mutant of both sexes. Maturing oocytes in the mutant also look indistinguishable from wild type. By DAPI staining, we found sperm are present in the spermatheca of the mutant (Figure 1G–H, arrow). The unshelled eggs produced by unmated spe-51 hermaphrodites showed a single DNA mass in the nucleus (Figure 1H, arrowhead), the classic “endomitotic” phenotype that results from continuous DNA replication in the oocytes without chromosome segregation 5. Because chromosome segregation depends on centrosomes brought in by the sperm6, our observation suggests that the sperm fails to enter the oocyte in spe-51 mutants and those unshelled eggs are unfertilized.

In C. elegans, hormonal signals secreted by the sperm stimulate oocyte maturation and ovulation 7. Because we observed the presence of sperm in spe-51(as39) mutants, we asked whether ovulation rates were normal. We measured ovulation rates by counting the total number of unfertilized eggs plus progeny produced throughout the egg laying period. spe-51(as39) showed slightly higher ovulation totals than wild-type controls (Figure 1D, t-test, p<0.0001). This higher ovulation rate was previously observed in the mutant of spe-13, another gene required in sperm for fertilization 8. Consistently, 4-day old spe-51(as39) mutants still have sperm in their spermathecae, as opposed to wild-type worms where all the sperm have participated in fertilization so that none remain in the spermatheca (Figure 1I–J). We reason that the sperm in the mutant are not utilized for fertilization but retained for longer, and so induce more ovulation events. These data further suggest that the fertility phenotype in spe-51 mutants is due to defects in the sperm that prevent them from fertilizing the oocytes.

spe-51 is not required for sperm activation, sperm motility or sperm competition

Since mutant spe-51 sperm cannot fertilize the oocytes, we examined the morphology of mutant spermatids and spermatozoa. Spermatids differentiate into spermatozoa after meiosis. In C. elegans, round and non-polar spermatids differentiate into ameboid spermatozoa that are polarized and motile and use their pseudopods to crawl 9. This process, called sperm activation or spermiogenesis, can be induced in vitro by pharmacological reagents such as Pronase 5,10. We initially observed the presence of sperm in mutant hermaphrodites, indicating that spermatids were made (Figure 1E–H). In fact, spermatids dissected from mutant males appeared normal (Figure 2A–B). When we treated the spermatids with Pronase, spe-51(as39) spermatids activated normally, similar to the wild-type controls (Figure 2C–D, arrowheads point to pseudopods in activated sperm). In C. elegans, hermaphrodite sperm activate when they are pushed into the spermatheca during the first rounds of ovulation 11. Sperm dissected from spe-51 hermaphrodites were activated in vivo, similar to those from the wild type (Figure 2E–F, arrowheads). Thus, spe-51 is not required for spermatid production or sperm activation either in vitro or in vivo.

Sperm motility is critical for its function because the sperm needs the ability to crawl to the spermatheca, the site of fertilization 5,12. Male-derived sperm activate and migrate to the spermatheca when deposited into the uterus during mating. Hermaphrodite self-sperm need to migrate back to the spermatheca if they are pushed out of it by passing oocytes. The observation that aged mutant hermaphrodites retained their sperm suggests that the sperm were motile and able to maintain their position in the spermatheca (Figure 1J). We tested the motility of spe-51(as39) male-derived sperm. We DAPI-stained mated fem-1(hc17) mutants to see whether the inseminated, male-derived sperm made their way to the spermatheca. Both control and spe-51(as39) mutant male-derived sperm were able to migrate to the spermatheca (Figure 2G–I, white brackets), suggesting that they activated properly in vivo and were motile. Thus, spe-51 is not required for sperm activation or sperm motility.

C. elegans male-derived sperm can out compete hermaphrodite self-sperm at fertilization 11,13,14. This effect can be measured by counting the number of outcross and self-progeny 13. A mated hermaphrodite preferably uses male-derived sperm over self-sperm and as a result, the production of self-progeny is suppressed 14. We tested whether spe-51(as39) mutant sperm were also able to out compete hermaphrodite self-sperm. When males were given a 48-hour window to mate with the hermaphrodite, the production of self-progeny is suppressed with both control and as39 males (Figure 2J, p<0.01 for both control and as39 males, one-way ANOVA). This suppression is not accompanied by a substantial rise in outcross progeny. This result suggests that spe-51(as39) males can out compete hermaphrodite self-sperm despite lacking the ability to fertilize the egg.

SPE-51 encodes a protein with an Ig-like domain

Traditional mapping positioned the as39 mutation on Chromosome IV between dpy-13 and unc-24 (data not shown). Using a mapping-by-sequencing approach 15–18, we identified a region with a low frequency for Hawaiian SNPs (Figure S1). Searching for homozygous, nonsynonymous mutations within this region, we found a single nonsense mutation (Chr:IV 4696911CtoT) in the second exon of the gene T22B11.1. Sanger sequencing confirmed that this mutation indeed exists in the genome of the spe-51(as39) mutants. An extrachromosomal transgene carrying a wild-type copy of T22B11.1 genomic DNA restored fertility in the mutant (Figure 1B). Thus, we confirm that spe-51 is T22B11.1 and that the mutation in as39 is responsible for the fertility phenotype.

The spe-51 gene produces a single transcript that encodes a protein of 468 amino acids. BLAST searches (https://blast.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/Blast.cgi) showed no obvious homologs outside of nematodes (Figure S2). The nonsense mutation in the as39 allele leads to a truncation of the protein at amino acid 31 (Q31STOP, Figure 3A). We have since obtained two additional alleles of spe-51. The as43 allele has an insertion that causes a frameshift that alters the coding sequence after amino acid 19 while the as44 allele has a nonsense mutation that truncates the protein at amino acid 20 (Figure 3A). Both as43 and as44 show the same fertility phenotype in hermaphrodites (Figure 1B). Based on the nature of the molecular lesions and the same extremely low fertility in all three alleles, they are all likely null alleles. Previous transcriptome data show that T22B11.1 expression is enriched in males 19,20. To check the expression of spe-51, we performed RT-PCR from glp-4(bn2) mutants, in which few germ cells are present in the germline and these cells don’t enter meiosis 21,22. Expression of spe-51 is absent in glp-4(bn2), but present in him-5(e1490) (Figure S3A), suggesting that spe-51 is specifically expressed in the germline. These data together with the sperm-specific mutant phenotypes strongly suggest that spe-51 is expressed only in the sperm.

Figure 3. Molecular features, secretion, and localization of SPE-51.

A. The spe-51 gene and protein products encoded by wild type and three different mutant alleles. Top panel shows the gene structure. Black boxes show the exons, and black lines in between exons show the introns. Bottom panels show the protein products. Wild-type SPE-51 protein: ss, signal sequence as recognized by SignalP5.0. The white box in the middle of the protein shows the hydrophobic region that some programs predict as a transmembrane domain. The mutant proteins predicted to be encoded by all three mutant alleles are shown below the wild type. B-D’. Expression of SPE-51::GFP in the muscle and its uptake by coelomocytes. B-D. DIC imaging. B’-D’. Green fluorescence of the worm as shown in B-D, respectively. Arrows in each panel point to the coelomocyte in the posterior region of the worm. Scale bars represent 50 μm. E-H’. localization of SPE-51. E-E’. N2 spermatids. F-F’. SPE-51::mNG spermatids. G-G’. N2 spermatozoa. H-H’. SPE-51::mNG spermatozoa. Scale bars represent 5 μm. See also Figure S1 – S3, and Table S1.

The high similarity between spe-51 phenotypes and those of the spe-9 class mutants led us to predict that SPE-51 functions during sperm-egg interaction and must be a transmembrane protein just like other SPE-9 class proteins. SPE-51 is predicted to have a signal sequence at the N-terminus (SignalP5.0 23). The SPE-51 protein is also predicted to have a single Ig-like domain (amino acids 76–190) by the Phyre 2 structural prediction tool (Figure 3A) 24. Although some programs (“DAS” and “Phyre2”) did recognize a transmembrane domain in SPE-51 (amino acids 197–212), other programs predicted that it is secreted (“TMHMM2.0” and “TOPCONS”). We decided to test whether it is secreted with a C. elegans secretion assay 25,26. Secreted proteins that are expressed from somatic tissues such as the gut or muscle are taken up by the scavenger cells, coelomocytes. We included two controls, a secreted version of GFP (ssGFP), and a SPE-45 tagged with GFP 27,28. SPE-45 is a predicted transmembrane protein and is not expected to be secreted. We found that when expressed in the muscle, ssGFP is present in the coelomocytes, SPE-45::GFP is absent (Figure 3B–D’, Figure S3B–D). SPE-51::GFP is also present in the coelomocytes indicating that it is secreted from the muscle cells (arrows, Figure 3D–D’, Figure S3B–D). We conclude that SPE-51 is not a transmembrane protein but is secreted.

We then tested the cell autonomy of SPE-51 function. If SPE-51 is indeed secreted by the sperm, the presence of SPE-51 secreted by wild-type sperm could allow the mutant sperm to gain the ability to fertilize oocytes. We re-analyzed our data from the male fertility test where we mated mutant males with either fem-1 or dpy-5 hermaphrodites. During a 24-hour mating period, spe-51(as39) mutant males produced an average of 5.9(±1.2) cross progeny with fem-1, but 1.2(±0.3) outcross progeny with dpy-5 (Figure 1C; Figure 2J). These numbers are consistent with SPE-51 acting cell-autonomously. To rule out the contribution of seminal fluid, we further tested autonomy by crossing SPE-51-positive males to mutant spe-51(as39) hermaphrodites. For this experiment, we used spe-9(eb19) mutant males that are completely sterile29 so any progeny can be counted as self-progeny from spe-51(as39) hermaphrodites. As a control, we used spe-51(as39) males. Compared to unmated hermaphrodites, hermaphrodites mated with either spe-9(eb19) or spe-51(as39) males did not show an increase or decrease in the number of self-progeny (Table S1, one-way ANOVA, p=0.28). Despite the possible situation where cross fertilization requires specific timing and amount of SPE-51 secretion and transfer, our data argue that SPE-51 acts cell-autonomously and stays associated with the sperm that produced the protein.

To visualize the SPE-51 protein, we obtained a tagged allele of spe-51 by inserting a C-terminal mNeonGreen (mNG) tag at the endogenous location using CRISPR. This strain shows slightly smaller but comparable brood size to wild type, indicating that adding the tag does not interfere with SPE-51 protein function (Figure S3E). In whole-mount males, we detected a signal in the region where spermatids are stored (Figure S3F–G), suggesting that SPE-51 is secreted by the sperm. Using confocal microscopy, in spermatids, we detected a signal that is consistently above the level of autofluorescence in control spermatids (Figure 3E–F’). The pattern of signal is consistent with localization to the membranous organelles (MOs) (Figure 3F’). In in vivo activated spermatozoa, the signal decorated the whole sperm surface, including the pseudopods (Figure 3H–H’, arrowheads). In the spermatozoa, the signal can also be seen in what appears to be the MOs, which have fused with the plasma membrane during spermiogenesis. The same observations were made when we used super-resolution microscopy (Figure S3H–K’). These results indicate that SPE-51 is secreted from the MOs and stays associated with the mature sperm. This localization pattern is consistent with the cell-autonomous behavior.

Mammalian SOF1 is secreted when expressed in C. elegans

Because SPE-51 is secreted, we hypothesize that secreted proteins could be required for fertilization on the gamete surface in mammals. One of the recently discovered mouse fertilization molecules, SOF1 30, is predicted by some programs to be secreted, similar to SPE-51. We decide to test whether SOF1 can be secreted using our secretion assay. As controls, we expressed ssGFP, SPE-51::GFP and TMEM95::GFP in the gut. We found that ssGFP and SPE-51::GFP are both present in the coelomocytes (Figure 4A–B’) as expected. TMEM95::GFP is mostly absent from the coelomocytes (Figure 4D–D’), although with a small percentage of weakly GFP-positive coelomocytes likely due to toxicity of the mammalian protein to worm cells (21%, n=39, Figure S3L–M). In contrast, SOF1::GFP is present in the coelomocytes (Figure 4C–C’) 100%, n=23). Thus, we conclude that SOF1 can be secreted when expressed in the worm. These data provide the first experimental evidence that SOF1 is a member of this newly emerging class of secreted proteins required for fertilization.

Figure 4. Secretion of mammalian SOF1 and model of SPE-51 functions.

A-A’. Secretion of ssGFP when expressed by the gut. B-B’. Secretion of SPE-51. C-C’. Secretion of SOF1. D-D’. TMEM95 is absent in the coelomocytes. A-D. DIC images of the middle section of the worm. A’-D’. fluorescent images of the green channel. Arrows point to one of the posterior coelomocytes. E. model of SPE-51 functions within the fertilization synapse. Spermatids (shown on the left) express SPE-51 in the MOs (shown as light grey shapes within the cytoplasm of spermatids). Upon activation, we predict that SPE-51 is translocated to the extracellular space of spermatozoa but stays associated with them (middle panel) possibly via interactions with unknown proteins on the sperm side (white rectangles). SPE-51 may interact with proteins on the sperm surface (additional white rectangles). Upon fertilization when the sperm encounters the oocyte, SPE-51 may also interact with proteins (dark grey rectangles) on the oocyte surface. See also Figure S3 and Table S1.

Discussion

The SPE-51 protein localizes to the MOs in spermatids and stay associated with spermatozoa surface. These observations suggest that SPE-51 is likely shuttled to the sperm surface during sperm activation when MOs fuse with the plasma membrane, similar to IZUMO1, which is contained in the acrosomes and redistribute to the sperm surface upon acrosome reaction 31. Based on the localization in spermatozoa and the cell-autonomous behavior, SPE-51 is likely tethered to the spermatozoa surface. Even though we cannot rule out lipid modification as a tether, proteins in the SPE-9 class are likely interacting with SPE-51. For example, SPE-38 is shown to interact with multiple fertilization proteins on the sperm surface by a membrane yeast two-hybrid assay 32. Recent live imaging of fluorescently tagged SPE-38 reveals that it localizes to the MOs and decorates to the entire spermatozoa surface after activation 33. Future work is needed to determine molecular interactions with SPE-51 and how SPE-51 is redistributed and tethered to the sperm surface.

Ig superfamily molecules are generally implicated in the molecular recognition and binding activities of cells 34. The Ig-like domain (or other parts) of SPE-51 may mediate the interactions of SPE-51 with cis binding partners on the surface of sperm, trans binding partners on the surface of the egg, or both (Figure 4E). These interactions may serve as an initial recognition signal or trigger functional conformational changes in SPE-51 itself and/or its binding partners on either gamete surface. Several Ig superfamily molecules have been shown to play a role in gamete interactions 4, including: the sperm protein GEX2 in Arabidopsis 35, FUS1 on the plus gamete in Chlamydomonas 36,37, IZUMO1 38 and SPACA6 in mice 30,39,40, and SPE-45 in worms 27,28. The presence of Ig superfamily proteins as required for gamete adhesion and/or fusion across a wide range of species further suggest a deep structural conservation at the fertilization synapse.

Here, we identify a secreted, Ig-domain containing protein SPE-51 that is required for sperm function at fertilization in C. elegans. SPE-51 is associated with the spermatozoa surface and acts cell-autonomously. This is the first time that sperm secreted molecules in C. elegans are shown to be involved in gamete interactions (also see Krauchunas et al. on spe-36). Previous work has identified a few secreted proteins that are critical for gamete recognition/binding, such as the egg surface receptor Ebr1 for the sperm protein Bindin in sea urchins 41,42, and the sperm surface SED1 for binding to the egg zona pellucida in mice 43. Together, our findings provide insights into the complexity of the fertilization synapse and serve as a paradigm for understanding how secreted proteins modify the sperm surface to influence their ability to interact with the egg.

STAR Methods

Resource Availability

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Xue Mei (meix@stjohns.edu).

Materials availability

Strains and plasmids generated in this study are available upon request. These two strains, AD292 and AD296, will be available from the Caenorhabditis Genetics Center at the University of Minnesota.

Data and code availability

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request. This paper does not report original code. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

Experimental model and subject details

All the strains were cultured on C. elegans growth media MYOB plates at 20°C unless stated otherwise. A list of strains used in this study can be found in the key resource table. The spe-51(as39) strain was identified in a previous ethyl methanesulfonate (EMS) mutagenesis screen for fertility genes by Dr. Guna Singaravelu and Dr. Diane Shakes in the lab of Dr. Andrew Singson. Details of the screen was previously described in 28. Before transgenic rescue, spe-51(as39) was maintained by crossing to N2 males and selecting sterile worms in the F2 generation. Once the gene was identified, we made transgenic lines that carry extrachromosomal arrays of genomic DNA of the spe-51 gene and crossed this line into the mutant background. Any animals that do not carry the array, as shown by the absence of fluorescent markers, would be mutant for spe-51. For all the experiments that used mutant males, this rescued line was crossed into the him-5(e1490) background. The him-5 mutants produce males due to defects in meiosis that affect X chromosome segregation. Having him-5 in the background does not affect the morphology or function of the sperm (Geldziler et al., 2011). All the control males are matched for their genetic backgrounds. Both spe-51(as43) and spe-51(as44) were isolated by CRISPR-mediate genome editing tools. We injected synthetic sgRNA with Cas9 protein into the germline of hermaphrodites. The dpy-10 locus was co-edited as a visible indicator of editing efficiency, a strategy described by Paix et al 44. The strain PHX2737, spe-51(syb2737) carries a mNeonGreen insertion at the endogenous location on the C-terminus. This allele was generated by SunyBiotech.

Key resources table

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Escherichia coli OP50–1 | CGC | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Protease from Streptomyces griseus | Sigma | P-6911 |

| Vectashield with DAPI Mounting Medium for Fluorescence | Vector Laboratories | H-1200 |

| S. pyogenes Cas9 (10ug/uL) | IDT | 1081058 |

| Nuclease-free Duplex buffer | IDT | 11–01-03–01 |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Zymo Direct-zol RNA MicroPrep kit | Zymo Research | R2061 |

| LunaScript RT SuperMix kit | NEB | E3010S |

| Phusion high fidelity DNA polymerase | NEB | M0530S |

| Expand Long Template PCR system | Roche | 11681834001 |

| NEBuilder® HiFi DNA Assembly Master Mix | NEB | E2621S |

| Miniprep kit | Qiagen | 27104 |

| PCR purification kit | Qiagen | 28104 |

| MinElute PCR purification kit | Qiagen | 28004 |

| Gel extraction kit | Qiagen | 28704 |

| LongAmp Taq PCR kit | NEB | E5200S |

| Competent cells | NEB | C2987H |

| KAPA HiFi HS+dNTPs (100U) | Roche | KK2501 |

| KAPA Hyper Prep PCR-free (8rxn) | Roche | KK8501 |

| AMPure XP beads | Beckman Coulter | A63880 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| C. elegans Bristol N2 | CGC | N/A |

| C. elegans AD291: spe-51(as39);asEx95[myo3p::gfp; T22B11.1genomicDNA] | This study | AD291 |

| C. elegans AD292: spe-51(as39);him-5(e1490);asEx95[myo3p::gfp; T22B11.1genomicDNA] | This study | AD292 |

| C. elegans AD306: spe-51(as43); asEx95[myo3p::gfp; T22B11.1genomicDNA] | This study | AD306 |

| C. elegans AD307: spe-51(as44); asEx95[myo3p::gfp; T22B11.1genomicDNA] | This study | AD307 |

| C. elegans PHX2737: spe-51(syb2737[spe-51::mNG]) | This study | PHX2737 |

| C. elegans DR466: him-5(e1490) | CGC | DR466 |

| C. elegans BA17: fem-1(hc17) | CGC | BA17 |

| C. elegans CB61: dpy-5(e61) | CGC | CB61 |

| C. elegans RT36: arIs37[myo3p::ssGFP] | Fares and Greenwald 200125 | RT36 |

| C. elegans SL438: spe-9(eb19); him-5(e1490); ebEx126 | CGC | SL438 |

| C.elegans AD348: glp-4(bn2);him-5(e1490) | This study | AD348 |

| C. elegans AD334: asEx99[myo-3p::spe-51::gfp; myo-2p::mCherry] 1D | This study | AD334 |

| C. elegans AD335: asEx100[myo-3p::spe-51::gfp; myo-2p::mCherry] 2B | This study | AD335 |

| C. elegans AD336: asEx101[myo-3p::spe-45::gfp; myo-2p::mcherry] 20 | This study | AD336 |

| C. elegans AD337: asEx102[myo-3p::spe-45::gfp;myo-2p::mcherry] 31 | This study | AD337 |

| C. elegans AD340: asEx105[vit-2p::tmem95::gfp;rps-0p::HygR]#2 | This study | AD340 |

| C. elegans AD341: asEx106[vit-2p::tmem95::gfp;rps-0p::HygR]#3 | This study | AD340 |

| C. elegans AD342: asEx107[vit-2p::sof1::gfp;rps-0p::HygR]#1 | This study | AD342 |

| C. elegans AD343: asEx108[vit-2p::sof1::gfp;rps-0p::HygR]#2 | This study | AD343 |

| C. elegans AD344: asEx109[vit-2p::spe-51::gfp;rps-0p::HygR]#1 | This study | AD344 |

| C. elegans AD345: asEx110[vit-2p::spe-51::gxfp;rps- 0p::HygR]#4 | This study | AD345 |

| C. elegans AD346: asEx111[vit-2p::ss::gfp;rps-0p::HygR]#1 | This study | AD346 |

| C. elegans AD347: asEx112[vit-2p::ss::gfp;rps-0p::HygR]#2 | This study | AD348 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Spe-51_genomic_F: 5’- TTTATGCCTGCCCGCCTATG - 3’ | IDT | N/A |

| Spe-51_genomic_R: 5’- TCCTCGAAATCGGCTGAAATGA −3’ |

IDT | N/A |

| Spe-51_RT_F: 5’-ACGTGTTTACACCGATGGCT-3’ | IDT | N/A |

| Spe-51_RT_R: 5’-GCGTCCCATCTCACTTCGAT-3’ | IDT | N/A |

| Spe-51_Cterm_F: 5’-AAGGACGAGAAAGATGGTTTGT- 3’ | IDT | N/A |

| Spe-51_Cterm_R: 5’-ATATGCATGCTCTCTCTTCCTC-3’ | IDT | N/A |

| Spe-45_pJF25_F: 5’cccacgaccactagatccatctagatctgaaaaaATGCAAGCTCT TTTGTATTTTAC-3’ |

IDT | N/A |

| Spe-45_pJF25_R: 5’tcctttactcattttttctaccggtgcCTTTTTCTTTTTCGTTGGC-3’ | IDT | N/A |

| Spe-51_pJF25_F:5’- cccacgaccactagatccatctagatctgaaaaaATGCCTTGGTTCT TATTTC-3’ |

IDT | N/A |

| Spe51_pJF25_R: 5’- tcctttactcattttttctaccggtgcACAATAATCAACTTGTGTAGA ATAG-3’ |

IDT | N/A |

| Pvit2_F: 5’-TAGCATTCGTAGAATTCCAACTG-3’ | IDT | N/A |

| Pvit2-R: 5’-GGCTGAACCGTGATTGGAC-3’ | IDT | N/A |

| Spe51GFP-overlap-F: 5’- agtccaatcacggttcagccATCTGAAAAAATGCCTTGG-3’ | IDT | N/A |

| GFP3’-overlap_R: 5’- ttggaattctacgaatgctaTTTGTATAGTTCGTCCATGC-3’ | IDT | N/A |

| SOF1GFP-overlap_F: 5’- agtccaatcacggttcagccATCTGAAAAAATGACCTCC-3’ | IDT | N/A |

| TMEM95-overlap_F: 5’- agtccaatcacggttcagccATCTGAAAAAATGTGGGTC-3’ | IDT | N/A |

| ssGFP-overlap_F: 5’- agtccaatcacggttcagccAGGATCCCCATCGAATTC-3’ | IDT | N/A |

| Alt-R® CRISPR-Cas9 tracrRNA, 5 nmol | IDT | 1072532 |

| Dpy-10 ssODN: CACTTGAACTTCAATACGGCAAGATGAGAATGACTG GAAACCGTACCGCATGCGGTGCCTATGGTAGCGGA GCTTCACATGGCTTCAGACCAACAGCCTAT |

IDT | N/A |

| Dpy-10 Alt-R® CRISPR-Cas9 crRNA, 2 nmol GCUACCAUAGGCACCACGAG | IDT | N/A |

| SG – 915 AATGATACGGCGACCACCGAGATCTACACTC TTTCCCTACACGA | Gu lab (Rutgers) | SG-915 and SG-916 are PCR primers for TruSeq library amplification, designed by Illumina |

| SG – 916 CAAGCAGAAGACGGCATACGAGAT | Gu lab (Rutgers) | N/A |

| Spe-51 sgRNA: UAACGGGUCUGUGCUGUAAA | Synthego | N/A |

| Gene fragment for mammalian TMEM95 cDNA | Azenta | N/A |

| Gene fragment for mammalian SOF1 cDNA | Azenta | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| pCFJ90 | Addgene | 19327 |

| pPD93_97 | Addgene | 1476 |

| PJF25 | Fares and Greenwald, 200125 | N/A |

| Pmyo3::spe-45::gfp | This study | N/A |

| Pmyo3::spe-51::gfp | This study | N/A |

| Pvit2::spe-51::gfp | This study | N/A |

| Pvit2::tmem95::gfp | This study | N/A |

| Pvit2::sof1::gfp | This study | N/A |

| Pvit2::ss::gfp | This study | N/A |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| DAS transmembrane prediction tool | https://tmdas.bioinfo.se/ | N/A |

| TMHMM-2.0 | https://services.healthtech.dtu.dk/services/TMHMM-2.0/ | N/A |

| TOPCONS | https://topcons.cbr.su.se/ | N/A |

| PHYRE2 | http://www.sbg.bio.ic.ac.uk/~phyre2/html/page.cgi?id=index | N/A |

| MimodD | https://mimodd.readthedocs.io/en/latest/ | N/A |

| PRALINE | https://www.ibi.vu.nl/programs/pralinewww/ | N/A |

Method details

Light and fluorescent Microscopy

To image whole live worms, hermaphrodites or males were mounted onto agarose pads and paralyzed in 1mM levamisole. To image the sperm, hermaphrodites or males were dissected in sperm media on a glass slide. For the secretion assay, the posterior coelomocytes were identified by their morphology under the DIC and imaged for fluorescence. For fluorescent imaging, appropriate filters (GFP or DAPI) were selected. DIC and fluorescent imaging was done using a Zeiss Universal microscope and captured with a ProgRes camera with the ProgresCapturePro software.

DAPI staining

Hermaphrodites were fixed in cold methanol for 30 seconds and washed in PBS. They were then transferred onto agarose pads with Vectashield mounting medium with DAPI. Fluorescent imaging was done on an epifluorescent microscope as described in the preceding subheading.

Progeny and ovulation count

For hermaphrodite fertility, each hermaphrodite was picked onto a fresh plate at the L4 stage. They were then transferred daily onto a new plate until they stopped laying eggs (for progeny count) or oocytes (for ovulation count). The number of adult progeny or progeny plus oocytes was counted daily.

To assess male fertility, fem-1(hc17) hermaphrodites were maintained at 16°C and shifted to 25°C at L1 stage. Shifted hermaphrodites were crossed with him-5(e1490) or spe-51(as39); him-5 young adult males in a 1:4 ratio. After 24 hours, males were removed and hermaphrodites were transferred to a new plate. The hermaphrodites were transferred daily until they stopped laying eggs. The number of adult progeny was counted.

Hermaphrodites that died or became absent before the end of the experiment were excluded from the analyses.

Sperm activation

L4 stage males were isolated from hermaphrodites overnight. The next day, they were dissected in normal sperm media (pH 7.80) with or without Pronase (200 μg/mL) 10. Imaging was done 10 minutes after dissection. L4 stage hermaphrodites were isolated from males for overnight. Then their reproductive tract was dissected in sperm media without Pronase.

Sperm migration

fem-1(hc17) hermaphrodites were crossed with him-5(e1490) or spe-51(as39); him-5(e1490) young adult males in a 1:4 ratio. After 24 hours, hermaphrodites were used for DAPI staining. Details for DAPI staining and fluorescent imaging were describe in the preceding subsections “DAPI staining” and “Light and Fluorescent Microscopy”.

Sperm competition

Individual dpy-5(e61) hermaphrodites were crossed with him-5(e1490) or spe-51(as39); him-5(e1490) young adult males in a 1:4 ratio for 48 hours at 20°C. At the end of 48 hours, the parents were removed. Three days later, all the Dpy and non-Dpy progeny on the plates were counted.

Sperm mixing to test cell autonomy

Individual spe-51(as39) hermaphrodites were crossed with spe-9(eb19); him-5(e1490) males, or spe-51(as39); him-5(e1490) males in 1:3 ratio for 24 hours at 20°C. At the end of 24 hours, the parents were removed. Three days later, all progeny on the plates were counted.

Whole genome sequencing and data analyses

Homozygous spe-51(as39) was crossed with CB4856 males. F1 progeny were allowed to self-fertilize. About 500 F2 progeny were picked into individual wells of 24-well plates at the L4 stage. Their fertility phenotype was scored the next day. About 100 sterile F2 worms were identified, washed in M9 and pooled in Tris-EDTA buffer. The frozen worms were then sonicated, and genomic DNA was extracted by standard column purification. Library construction was done the same way as described previously 45. For data analysis, we used the MiModD program (https://mimodd.readthedocs.io/en/latest/) and filtered the region from 4.5Mbp~7Mbp on Chromosome IV.

Transgenic rescues

The genomic region of spe-51 was amplified by PCR from N2 genomic DNA using the Expand Long Template PCR system from Roche. This 6.5 kb product covers all the exons as well as 1378 bp upstream of the transcription start site and 1130 bp downstream of the stop codon. The PCR product (2 μL of 120ng/μL) together with the injection marker plasmid pPD93_97 (3 μL of 180 ng/μL) was injected into N2 young adult worms and stable transgenic lines were selected. This transgenic line was then crossed into the spe-51(as39) mutant background. F2 individuals that segregated GFP-negative sterile progeny indicated that they were homozygous for spe-51(as39). GFP-positive worms from these individuals were then scored for fertility to evaluate rescue.

RT-PCR

The temperature-sensitive strain glp-4(bn2);him-5(e1490) was grown at 25°C. Both the him-5(e1490) and glp-4(bn2);him-5(e1490) animals were bleach synchronized and adults were collected for RNA extraction. Total RNA was extracted using the Zymo Direct-zol RNA MicroPrep kit. cDNA was synthesized using the LunaScript RT SuperMix kit (NEB). PCR was done using the cDNA as template and gene-specific primers. PCR conditions were selected based on manufacturer’s instructions and annealing temperatures were selected based on estimated Tm for primers.

Secretion assay

The plasmid pJF25 was used as a backbone for cloning. This plasmid contains the promoter region of myo-3, a signal sequence from SEL-1, GFP, and the 3’UTR of unc-54 25. For cloning, pJF25 was digested by AgeI and XbalI which flank the signal sequence from SEL-1. Digested DNA was purified by column purification (Qiagen PCR purification Kit). Gene fragments for spe-51 (cDNA) and spe-45 (genomic DNA) were amplified by PCR, purified by column, and inserted into digested pJF25 by Gibson Assembly (NEBuilder HiFi DNA assembly kit). We designed the Gibson Assembly so that spe-51 or spe-45 would be inserted between the myo-3 promoter and GFP, replacing the original signal sequence. TMEM95 and SOF1 full length cDNA 30 was ordered as gene fragments and inserted into pJF25 replacing the signal sequence as described above. For expression in the gut, ssGFP, SPE-51::GFP, TMEM95::GFP and SOF1::GFP were amplified from the above plasmids. All four fragments were then inserted to a plasmid containing the vit-2 promoter by Gibson assembly. All the final constructs were verified by Sanger sequencing. For injections, individual expression constructs were mixed with pCFJ90 and injected into the gonad of young adults. F1 transformants were isolated and F2 transmitting lines were generated. At least two independent lines for each expression construct were obtained and imaged. Imaging was done by mounting whole live adult hermaphrodites on agarose pads. Fluorescent imaging was described in the subsection “Light and Fluorescent Microscopy”.

Localization of SPE-51

The strain PHX2737 was heat-shocked to obtain males. The heat shock was done with L4 stage hermaphrodites at 30°C for 4.5–5.5 hours. Male progeny from these heat-shocked animals were selected and mated with PHX2737 hermaphrodites. Continuous mating was set up to maintain males in the population. For whole-mount imaging, spe-51::mNG; him-5 worms and him-5 control males were mounted on agarose pads. Images were obtained on a AxioPlanII epifluorescent microscope with an ORCA charge-coupled device camera (Hamamatsu) using the iVision software (Biovision Technologies). For spermatids, males were separated from hermaphrodites overnight and then dissected in sperm media. To get in vivo activated sperm, 10 hermaphrodites and 20 males were picked on to a plate and allowed to mate overnight. The next day, hermaphrodites were dissected in sperm media. Following dissection, sperm were then dispersed on the slide and ready for imaging. N2 crosses were set up the same way as a control. For Figure 4, images for spermatids were obtained on a Leica TCS SP8 confocal microscope with a 63x oil immersion objective. Excitation laser was set at 488 nm. Emission range was 509–524 nm. Images were a maximum projection of two optical sections that are 0.5μm thick. Lightening deconvolution was applied, with the highest resolution setting. Images for spermatozoa were obtained on a Leica TCS SP8 tauSTED 3x confocal microsope with a 40x oil immersed objective. Excitation laser was set at 510 nm and emission range was 521nm-588nm with time gating set between 1ns and 6ns. Images were single section of a step of 3 sections of 0.33 μm apart. Standard lightening deconvolution was applied. For Figure S3H–K’, images were obtained on a Zeiss Elyra7 Lattice Structured Illumination Microscope (SIM2) with the 63W objective using the 488nm laser.

Quantification and Statistical Analyses

Statistical analyses (t-test or one-way ANOVA) were done in Microsoft Excel. For all tests, N numbers indicate the total number of worms. Statistical significance was defined as showing a p-value of less than 0.05. All p-values and names of tests were provided in the main text and figure legends.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Sperm from spe-51 mutant appear normal, behave normally but cannot fertilize the egg.

SPE-51 protein has an Immunoglobulin-like domain and a hydrophobic region.

SPE-51 localizes to the surface of spermatozoa and mutants behave cell-autonomously.

SPE-51 and the mammalian SOF1 are both secreted in a secretion assay.

Acknowledgements

We thank Dr. Christopher Rongo for sharing experimental equipment. We thank Waksman Institute Shared Imaging Facility, Rutgers, The State University of New Jersey for microscopy service. Special thanks to Nanci Kane, Director of the Waksman Institute Shared Imaging Facility and Dr. Jessica Shivas for offering help with confocal microscopy. Dr. Matthew Marcello and all members of the Singson lab provided critical feedback on this manuscript. The C. elegans Genetics Center is funded by NIH Office of Research Infrastructure Programs (P40 OD010440). The Singson lab is supported by the National Institute of Health (NIH) grant R01HD054681 to A.W.S. B.D.G is supported by the NIH grant R01GM135326 to B.D.G. D.C.S is supported by the NIH grant R15GM-096309 to D.C.S and the McLeod Tyler Professorship to D.C. S. S.G is supported by the NIH grant R01GM111752 to S.G. K.A.M was also supported by an NIH Institutional Research and Academic Career Development Award (K12GM093854) Fellowship. X.M. was supported by a Busch Postdoctoral Fellowship and startup funds from St. John’s University.

Footnotes

Declaration of Interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Bhakta HH, Refai FH, and Avella MA (2019). The molecular mechanisms mediating mammalian fertilization. Development 146. 10.1242/dev.176966. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Schultz R, and Williams C. (2005). Developmental biology: sperm-egg fusion unscrambled. Nature 434, 152–153. 10.1038/434152a. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mei X, and Singson AW (2021). The molecular underpinnings of fertility: Genetic approaches in Caenorhabditis elegans. Adv Genet (Hoboken) 2. 10.1002/ggn2.10034. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lu Y, and Ikawa M. (2022). Eukaryotic fertilization and gamete fusion at a glance. J Cell Sci 135. 10.1242/jcs.260296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Geldziler BD, Marcello MR, Shakes DC, and Singson A. (2011). The genetics and cell biology of fertilization. Methods Cell Biol 106, 343–375. 10.1016/B978-0-12-544172-8.00013-X. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.O’Connell KF (2000). The centrosome of the early C. elegans embryo: inheritance, assembly, replication, and developmental roles. Curr Top Dev Biol 49, 365–384. 10.1016/s0070-2153(99)49018-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Miller MA, Nguyen VQ, Lee M-H, Kosinski M, Schedl T, Caprioli RM, and Greenstein D. (2001). A Sperm Cytoskeletal Protein That Signals Oocyte Meiotic Maturation and Ovulation. Science 291, 2144–2147. 10.1126/science.1057586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.L’Hernault SW, Shakes DC, and Ward S. (1988). Developmental genetics of chromosome I spermatogenesis-defective mutants in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 120, 435–452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singson A. (2001). Every sperm is sacred: fertilization in Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol 230, 101–109. 10.1006/dbio.2000.0118. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shakes DC, and Ward S. (1989). Initiation of spermiogenesis in C. elegans: a pharmacological and genetic analysis. Dev Biol 134, 189–200. 10.1016/0012-1606(89)90088-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ward S, and Carrel JS (1979). Fertilization and sperm competition in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. Dev Biol 73, 304–321. 10.1016/0012-1606(79)90069-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ward S, and Miwa J. (1978). Characterization of temperature-sensitive, fertilization-defective mutants of the nematode caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 88, 285–303. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Singson A, Hill KL, and L’Hernault SW (1999). Sperm competition in the absence of fertilization in Caenorhabditis elegans. Genetics 152, 201–208. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.LaMunyon CW, and Ward S. (1995). Sperm precedence in a hermaphroditic nematode (Caenorhabditis elegans) is due to competitive superiority of male sperm. Experientia 51, 817–823. 10.1007/bf01922436. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Sarin S, Prabhu S, O’Meara MM, Pe’er I, and Hobert O. (2008). Caenorhabditis elegans mutant allele identification by whole-genome sequencing. Nat Methods 5, 865–867. 10.1038/nmeth.1249. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Doitsidou M, Poole RJ, Sarin S, Bigelow H, and Hobert O. (2010). C. elegans mutant identification with a one-step whole-genome-sequencing and SNP mapping strategy. PLoS One 5, e15435. 10.1371/journal.pone.0015435. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Zhao Y, Tan CH, Krauchunas A, Scharf A, Dietrich N, Warnhoff K, Yuan Z, Druzhinina M, Gu SG, Miao L, et al. (2018). The zinc transporter ZIPT-7.1 regulates sperm activation in nematodes. PLoS Biol 16, e2005069. 10.1371/journal.pbio.2005069. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Thompson OA, Snoek LB, Nijveen H, Sterken MG, Volkers RJ, Brenchley R, Van’t Hof A, Bevers RP, Cossins AR, Yanai I, et al. (2015). Remarkably Divergent Regions Punctuate the Genome Assembly of the Caenorhabditis elegans Hawaiian Strain CB4856. Genetics 200, 975–989. 10.1534/genetics.115.175950. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Reinke V, Smith HE, Nance J, Wang J, Van Doren C, Begley R, Jones SJ, Davis EB, Scherer S, Ward S, and Kim SK (2000). A global profile of germline gene expression in C. elegans. Mol Cell 6, 605–616. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ortiz MA, Noble D, Sorokin EP, and Kimble J. (2014). A new dataset of spermatogenic vs. oogenic transcriptomes in the nematode Caenorhabditis elegans. G3 (Bethesda) 4, 1765–1772. 10.1534/g3.114.012351. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Beanan MJ, and Strome S. (1992). Characterization of a germ-line proliferation mutation in C. elegans. Development 116, 755–766. 10.1242/dev.116.3.755. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rastogi S, Borgo B, Pazdernik N, Fox P, Mardis ER, Kohara Y, Havranek J, and Schedl T. (2015). Caenorhabditis elegans glp-4 Encodes a Valyl Aminoacyl tRNA Synthetase. G3 (Bethesda) 5, 2719–2728. 10.1534/g3.115.021899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Almagro Armenteros JJ, Tsirigos KD, Sonderby CK, Petersen TN, Winther O, Brunak S, von Heijne G, and Nielsen H. (2019). SignalP 5.0 improves signal peptide predictions using deep neural networks. Nat Biotechnol 37, 420–423. 10.1038/s41587-019-0036-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Kelley LA, Mezulis S, Yates CM, Wass MN, and Sternberg MJ (2015). The Phyre2 web portal for protein modeling, prediction and analysis. Nat Protoc 10, 845–858. 10.1038/nprot.2015.053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Fares H, and Greenwald I. (2001). Regulation of endocytosis by CUP-5, the Caenorhabditis elegans mucolipin-1 homolog. Nat Genet 28, 64–68. 10.1038/ng0501-64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fares H, and Grant B. (2002). Deciphering endocytosis in Caenorhabditis elegans. Traffic 3, 11–19. 10.1034/j.1600-0854.2002.30103.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Nishimura H, Tajima T, Comstra HS, Gleason EJ, and L’Hernault SW (2015). The Immunoglobulin-like Gene spe-45 Acts during Fertilization in Caenorhabditis elegans like the Mouse Izumo1 Gene. Curr Biol 25, 3225–3231. 10.1016/j.cub.2015.10.056. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singaravelu G, Rahimi S, Krauchunas A, Rizvi A, Dharia S, Shakes D, Smith H, Golden A, and Singson A. (2015). Forward Genetics Identifies a Requirement for the Izumo-like Immunoglobulin Superfamily spe-45 Gene in Caenorhabditis elegans Fertilization. Curr Biol 25, 3220–3224. 10.1016/j.cub.2015.10.055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Singson A, Mercer KB, and L’Hernault SW (1998). The C. elegans spe-9 gene encodes a sperm transmembrane protein that contains EGF-like repeats and is required for fertilization. Cell 93, 71–79. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Noda T, Lu Y, Fujihara Y, Oura S, Koyano T, Kobayashi S, Matzuk MM, and Ikawa M. (2020). Sperm proteins SOF1, TMEM95, and SPACA6 are required for sperm-oocyte fusion in mice. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 117, 11493–11502. 10.1073/pnas.1922650117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Satouh Y, Inoue N, Ikawa M, and Okabe M. (2012). Visualization of the moment of mouse sperm-egg fusion and dynamic localization of IZUMO1. J Cell Sci 125, 4985–4990. 10.1242/jcs.100867. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Marcello MR, Druzhinina M, and Singson A. (2018). Caenorhabditis elegans sperm membrane protein interactome. Biol Reprod 98, 776–783. 10.1093/biolre/ioy055. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zuo Y, Mei X, and Singson A. (2023). CRISPR/Cas9 Mediated Fluorescent Tagging of Caenorhabditis elegans SPE-38 Reveals a Complete Localization Pattern in Live Spermatozoa. Biomolecules 13. 10.3390/biom13040623. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Barclay AN (2003). Membrane proteins with immunoglobulin-like domains--a master superfamily of interaction molecules. Semin Immunol 15, 215–223. 10.1016/s1044-5323(03)00047-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Mori T, Igawa T, Tamiya G, Miyagishima SY, and Berger F. (2014). Gamete attachment requires GEX2 for successful fertilization in Arabidopsis. Curr Biol 24, 170–175. 10.1016/j.cub.2013.11.030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Misamore MJ, Gupta S, and Snell WJ (2003). The Chlamydomonas Fus1 protein is present on the mating type plus fusion organelle and required for a critical membrane adhesion event during fusion with minus gametes. Mol Biol Cell 14, 2530–2542. 10.1091/mbc.e02-12-0790. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pinello JF, Liu Y, and Snell WJ (2021). MAR1 links membrane adhesion to membrane merger during cell-cell fusion in Chlamydomonas. Dev Cell 56, 3380–3392 e3389. 10.1016/j.devcel.2021.10.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Inoue N, Ikawa M, Isotani A, and Okabe M. (2005). The immunoglobulin superfamily protein Izumo is required for sperm to fuse with eggs. Nature 434, 234–238. 10.1038/nature03362. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Lorenzetti D, Poirier C, Zhao M, Overbeek PA, Harrison W, and Bishop CE (2014). A transgenic insertion on mouse chromosome 17 inactivates a novel immunoglobulin superfamily gene potentially involved in sperm-egg fusion. Mamm Genome 25, 141–148. 10.1007/s00335-013-9491-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Barbaux S, Ialy-Radio C, Chalbi M, Dybal E, Homps-Legrand M, Do Cruzeiro M, Vaiman D, Wolf JP, and Ziyyat A. (2020). Sperm SPACA6 protein is required for mammalian Sperm-Egg Adhesion/Fusion. Sci Rep 10, 5335. 10.1038/s41598-020-62091-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Kamei N, and Glabe CG (2003). The species-specific egg receptor for sea urchin sperm adhesion is EBR1,a novel ADAMTS protein. Genes Dev 17, 2502–2507. 10.1101/gad.1133003. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Vacquier VD (2012). The quest for the sea urchin egg receptor for sperm. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 425, 583–587. 10.1016/j.bbrc.2012.07.132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ensslin MA, and Shur BD (2003). Identification of mouse sperm SED1, a bimotif EGF repeat and discoidin-domain protein involved in sperm-egg binding. Cell 114, 405–417. 10.1016/s0092-8674(03)00643-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Paix A, Folkmann A, and Seydoux G. (2017). Precision genome editing using CRISPR-Cas9 and linear repair templates in C. elegans. Methods 121-122, 86–93. 10.1016/j.ymeth.2017.03.023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krauchunas AR, Mendez E, Ni JZ, Druzhinina M, Mulia A, Parry J, Gu SG, Stanfield GM, and Singson A. (2018). spe-43 is required for sperm activation in C. elegans. Dev Biol 436, 75–83. 10.1016/j.ydbio.2018.02.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All data reported in this paper will be shared by the lead contact upon request. This paper does not report original code. Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.