Abstract

Fatigue among patients with head and neck cancer (HNC) has been associated with higher inflammation. Short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs) have been shown to have anti-inflammatory and immunoregulatory effects. Therefore, this study aimed to examine the association between SCFAs and fatigue among patients with HNC undergoing treatment with radiotherapy with or without concurrent chemotherapy. Plasma SCFAs and the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory-20 were collected prior to and one month after the completion of treatment in 59 HNC patients. The genome-wide gene expression profile was obtained from blood leukocytes prior to treatment. Lower butyrate concentrations were significantly associated with higher fatigue (p=0.013) independent of time of assessment, controlling for covariates. A similar relationship was observed for iso/valerate (p=0.025). Comparison of gene expression in individuals with the top and bottom 33% of butyrate or iso/valerate concentrations prior to radiotherapy revealed 1,088 and 881 significantly differentially expressed genes, respectively (raw p<0.05). The top 10 Gene Ontology terms from the enrichment analyses revealed the involvement of pathways related to cytokines and lipid and fatty acid biosynthesis. These findings suggest that SCFAs may regulate inflammatory and immunometabolic responses and, thereby, reduce inflammatory-related symptoms, such as fatigue.

Keywords: Short chain fatty acids, fatigue, inflammation, gene expression, radiotherapy, chemotherapy, head and neck cancer

Introduction

There is a growing awareness that the gut microbiome is a key regulator of brain function through the gut-brain axis. Commensal bacteria contribute to brain development and function in mice1,2 and humans,3,4 and microbiome dysbiosis has been implicated in complex symptoms5 including fatigue6,7 and depression.8 The gut microbiome also is believed to play immunomodulatory roles, in part mediated by short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs),8,9 the most abundant metabolites of bacterial fermentation of dietary fibers in the gut.10 SCFAs, including notably butyrate, not only play key anti-inflammatory and immunomodulatory roles within the gut and periphery,11,12 but also cross the blood-brain barrier,13 leading to decreases in neuroinflammation and improvement in brain homeostasis.14 Evidence further suggests that SCFAs act as histone deacetylase (HDAC) inhibitors at high concentrations.15 As a major epigenetic mechanism, the inhibition of HDAC facilitates the accessibility of DNA to transcription factors and, subsequently, promotes gene expression.16 Therefore, by inhibiting HDAC, SCFAs can modulate signaling pathways related to neuroprotection, the inflammatory response, and oxidative stress at the level of gene expression.17,18 These signaling pathways are also commonly altered in cancer patients with fatigue.19–22 However, the association between SCFAs and fatigue among cancer patients has not been well-documented.

Fatigue is the most reported side effect of cancer and its treatment. However, the management of fatigue is still challenging, in part due to the unclear mechanisms involved. Our previous studies have identified that elevated inflammatory responses during and following cancer treatment may play a key role in cancer-related fatigue.23,24 Our early findings also suggested that the gut microbiome profiles associated with high inflammation and low SCFA production may contribute to high fatigue in head and neck cancer patients.25,26 These results support a potential link among the gut microbiome, its metabolites, and fatigue in cancer patients undergoing treatment. Indeed, among patients with head and neck cancer (HNC), the side effects from cancer and its treatment, such as mucositis, dry mouth, and oral pain, trigger significant changes in food intake. Due to the impact of diet on the gut microbiome and its metabolites,27,28 reduced SCFAs may occur before and after cancer treatment. Given the potential beneficial effects of SCFAs, our primary hypothesis was that lower SCFAs would be associated with higher fatigue among patients with HNC. Thus, the goal of this study was to examine the association between blood SCFAs concentrations and fatigue among patients with HNC undergoing radiotherapy with or without concurrent chemotherapy. We also explored functional molecular pathways associated with SCFAs via gene expression profiles.

Material and Methods

Study Design and Population

This was a longitudinal study; potential patients were recruited from the clinics of Emory University Winship Cancer Institute. Once eligibility was established, patients were consented, and data were collected prior to radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy and/or and one month post-treatment. The duration of the treatment was approximately six weeks. If needed, surgery occurred approximately one month prior to radiotherapy. Eligible patients were enrolled in the study based on the following inclusion criteria: newly diagnosed with cancer of the head and neck region without distant metastasis and uncontrolled major organ disease. Patients were excluded if they had simultaneous tumors at other sites. Patients with major psychiatric disorders or chronic medical conditions involving the immune system (e.g., hepatitis B or C infection or human immunodeficiency virus) were also excluded. The study was approved by the Emory Institutional Review Board; all patients provided informed consent.

Demographic, clinical, and symptom measures

Demographic characteristics were collected via a standard questionnaire, including age, sex (men vs. women), race (white vs. non-white), marital status (married/living with significant others vs. not), history of smoking (defined as cigarette smoking ≥ one year), and history of alcohol use (defined as ≥one drink/week during the past one year). Clinical characteristics were collected through chart review and included variables of body mass index (BMI), medical comorbidities (Charlson Comorbidity Index), primary cancer site (oropharynx vs. others), cancer stage (TNM; >=III vs. IV), radiation dose, cancer treatment (radiotherapy±surgery; chemoradiotherapy; chemoradiotherapy+surgery), feeding tubes (yes vs. no), and human papillomavirus (HPV) status (related vs. not related). These variables were considered as potential covariates in the analysis.

Fatigue was assessed using the Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI)-20; patients completed the questionnaire using a paper-pencil format. MFI, a 20-item self-report instrument, measures five fatigue dimensions: general fatigue, physical fatigue, mental fatigue, reduced motivation, and reduced activity.29 Each dimension includes four items on a 1- to 5-point scale. The total score is the sum of all 20 items and ranges from 20 to 100, with a higher score indicating more fatigue. The MFI-20 has well-established validity and reliability (α=0.84) in patients with cancer receiving RT.29,30

Laboratory Measurements

Whole blood was collected into chilled EDTA tubes to isolate plasma and blood leukocytes (buffy coat) using standardized protocols24,31 and stored at −80°C until batched assays for SCFAs and gene expression. Whole blood for gene expression was collected at baseline only. To reduce the travel burden, the time of blood sample collection varied during the day depending on patients’ clinical visits with their oncologists.

Short-chain fatty acids:

The Emory Integrated Lipidomics Core performed assays for free fatty acids (FFAs) in plasma. The FFA panel included three major SCFAs (butyrate, acetate and propionate), as well as formate, iso/caproate, and iso/valerate, which were examined in exploratory analyses. The selection of butyrate, acetate, and propionate as primary outcome variables was based on previous publications10,32–35 on the potential association of SCFAs with the gut microbiome. For the FFA panel, 100 μl of plasma were aliquoted into a 96-deep well plate for the derivatization. 20 μL of 200 mM 3-NPH and 20 μL of 120 mM N-EDC were then added to each sample, followed by 6% pyridine and derivatized at 40°C for 30 min. 1.5mL of 10% acetonitrile were added into each tube after the reaction and were spun at 4,000 rpm for 15 min at 4°C. The 400 uL of the top layer of the centrifuged supernatant were drawn from each sample and filtered with a 0.2 μm filter plate. 20μL of the filtered sample were then injected into Sciex Exion AC HPLC/SCIEX QTRAP 5500 (Sciex, Waltham, MA) LC/MS system to generate data. For chromatography, lipids were resolved using a ThermoScientific Accucore C18 (4.6 × 100mm, 2.6μm) column on a 12-minute linear gradient consisting of 0.1 % formic acid in water (Solvent A) and 0.1 % formic acid in acetonitrile (Solvent B). The FFAs were analyzed with a multiple reaction monitoring-based method, using the derivated mass as the precursor mass and the pyridinyl moiety as the product mass (Supplementary Table 1). The concentration of each detected FFA was determined based on five-point calibration with external standards within the range of 0.1 nM to 100 μM.

Genome-wide RNA gene expression:

Total RNA was isolated from blood leukocytes according to the manufacturer’s protocol (Qiagen RNeasy Mini Kit: Qiagen; Valencia, CA). RNA integrity was determined by scanning with an Agilent 2100 Bioanalyzer using the RNA 6000 Nano LabChip. Samples with RNA integrity number (RIN) <5 were excluded. No sample was excluded as RIN <5. Isolated RNA was kept at −80 C until microarray analysis. The Emory Integrated Genomics Core analyzed RNA samples for gene expression using Clariom S Assay for humans (Applied Biosystems; San Diego, CA).

R package oligo36 was used to process raw data, which were then normalized with the log scale robust multi-array analysis (RMA).37 After the preprocessing, 19,556 genes with annotation were left. Samples were further filtered by using 1) the median of the signal (<90) and 2) the area under the curve (AUC; <0.9). Negative and positive control probes in each sample were used to calculate AUC. No sample was removed after quality control.

Statistical analyses

Descriptive statistics were used for demographic and clinical variables: mean and standard deviation for continuous variables, and frequency and percentage for categorical variables. Paired t-tests were used to compare the changes in SCFA and fatigue from pre- to post-RT. Mixed-effect models were performed to examine the linear association between SCFAs (independent variable) and fatigue scores (dependent variable) at both time points, controlling for time (pre vs. post-treatment) and other covariates. Covariates were selected based on association with fatigue and a priori.23 In addition, sensitivity analyses (two-way ANOVA) were carried out with a categorical fatigue score to examine SCFA concentrations as a function of high versus low fatigue; time (pre vs. post-treatment) and their interaction. According to established cutoff score of the MFI-20, patients with fatigue scores >43.5 were classified as experiencing high fatigue, and patients with fatigue scores <=43.5 were classified as having low fatigue.38 SCFAs were natural log-transformed to normalize the distributions. Further sensitivity analyses were conducted for the five dimensions of fatigue and their association with significant SCFAs using linear mixed-effect models. All statistical analyses were performed using SPSS 27 with a two-tailed p < 0.05 considered to be statistically significant.

For the SCFAs significantly associated with fatigue, we further explored whether high/low SCFAs concentrations were associated with differentially expressed genes prior to treatment. For this analysis, the SCFA values were categorized into tertiles (33%, 66%). Genes from patients with a low SCFAs tertile (1–33%) were compared with those from patients with a high SCFAs tertile (66–100%) using logistic regression. All analyses were adjusted for possible plate effects and other covariates. Given the sample size, p<0.05 was used to identify significant genes associated with SCFAs.

Enriched gene ontology (GO) terms were identified in an analysis with more than 2 FDR-corrected genes using the R package topGO. Fisher’s Exact test was implemented to determine over-expressed GO pathways. p<0.05 was used to identify significant GO terms, due to exploratory and hypothesis-generating nature of the study.

Results

Demographic and clinical characteristics of study participants

Fifty-nine eligible patients were enrolled in the study. All of them had baseline data, and only one patient’s post-treatment fatigue and SCFA data were missing. The average age of study participants was 59 years old. The majority were men (71%), white (84%), and married (67%). Sixty percent of study participants had a history of tobacco use and 46% had a history of alcohol use. Approximately 50% of study participants were diagnosed with oropharyngeal cancer; 52% had HPV-associated tumors; and 75% had advanced tumors (stage IV). All study participants received radiotherapy, and 78% received concurrent chemotherapy. Forty-five percent of patients received surgery prior to radiotherapy and/or chemotherapy. The fatigue score was 49.52 ± 17.37 at pre-treatment, which was significantly increased to 53.68 ± 15.66 at one month post-treatment (paired t-test p=0.03; Supplemental Figure 1A). No significant differences were found between pre- and post-treatment for butyrate and acetate using paired t-tests; significant decreases in propionate (pre: −0.015±0.018; post: −1.022±0.015; p=0.027; Supplemental Figure 1B) were observed. Exploratory analyses showed that iso/valerate had a trend of decline at one-month post-RT, compared to pre-RT (pre: 0.036±0.195; post: −0.037±0.188; p=0.05; Supplemental Figure 1C).

Association between SCFAs and fatigue from pre- to one month post-treatment

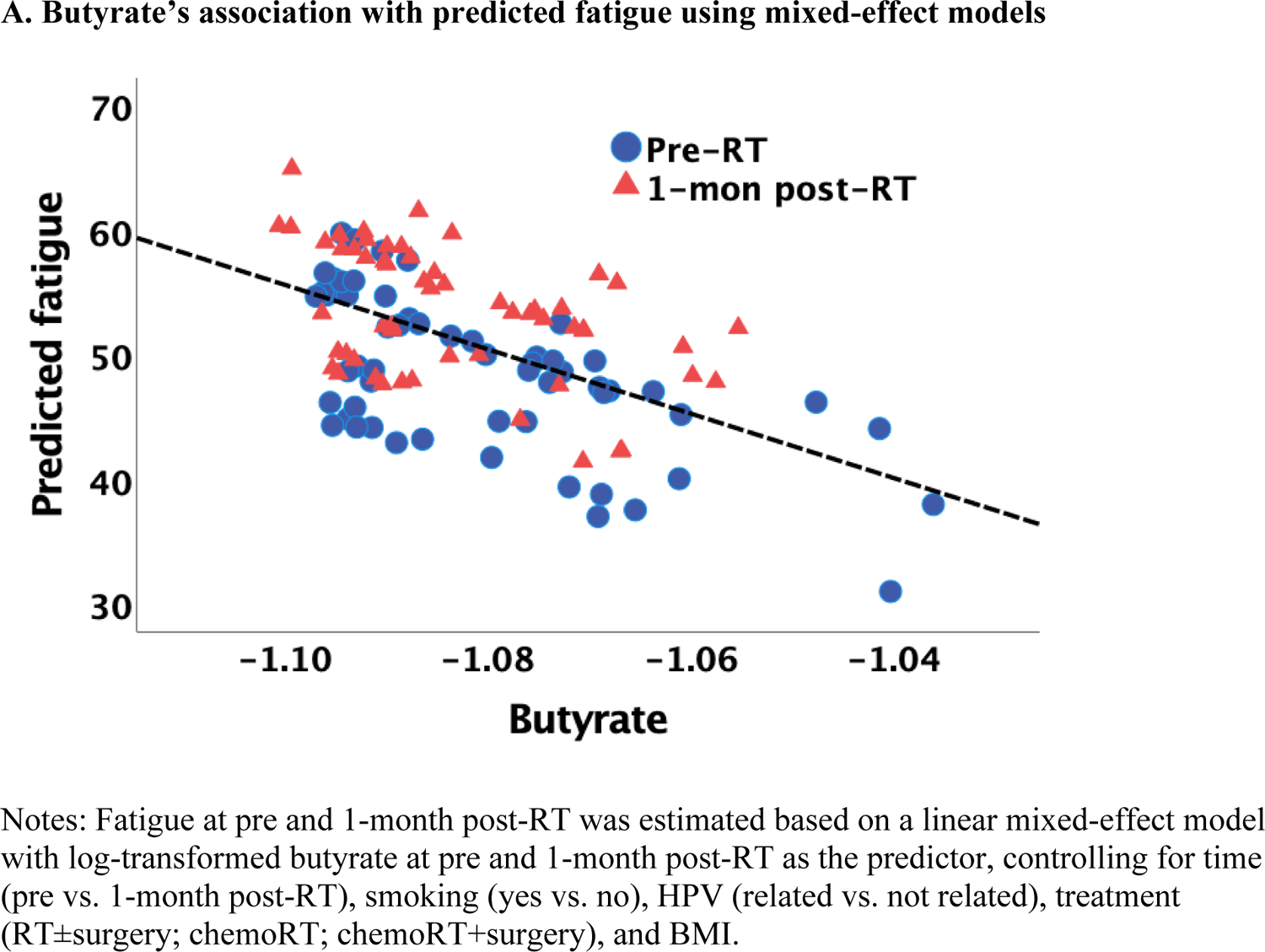

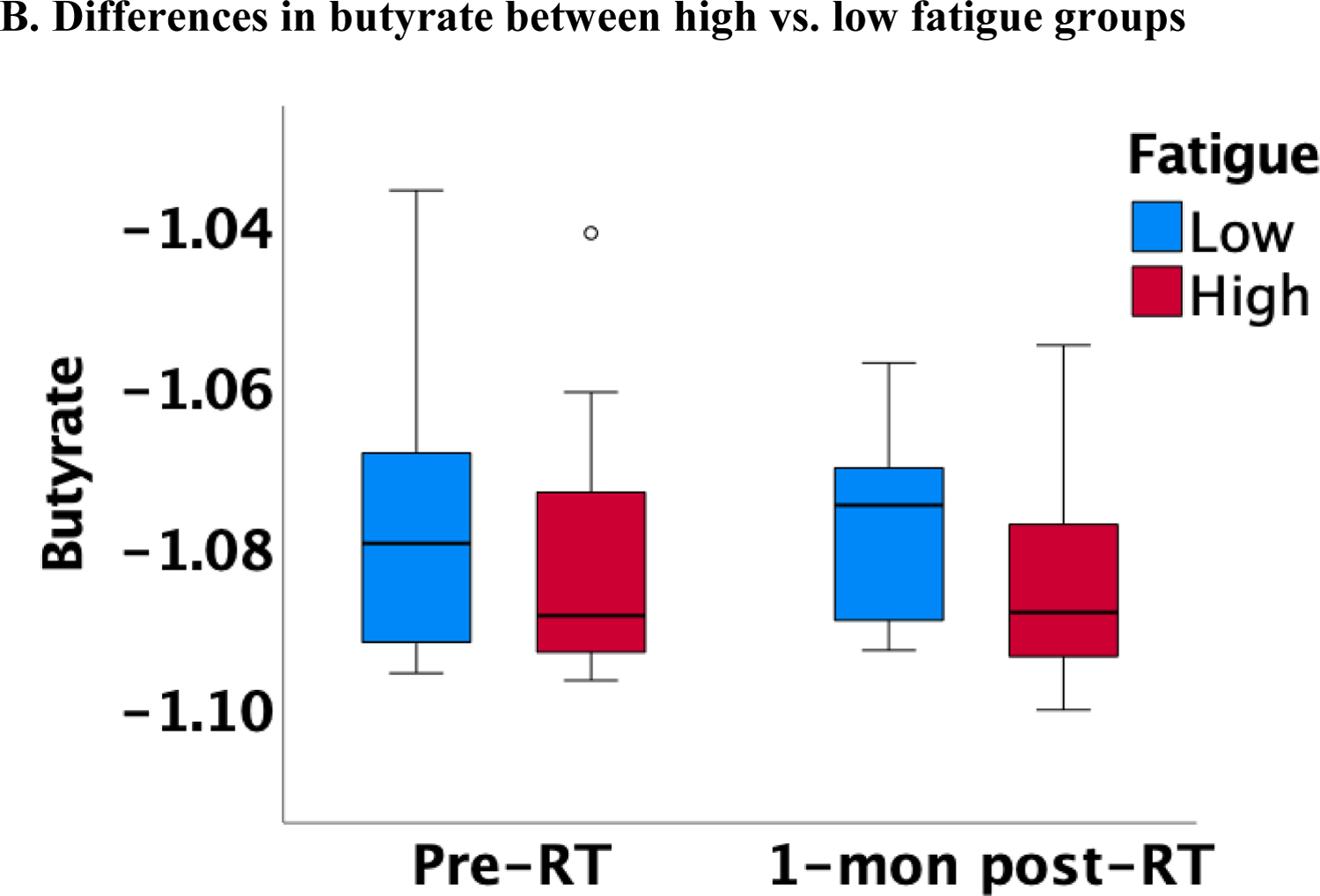

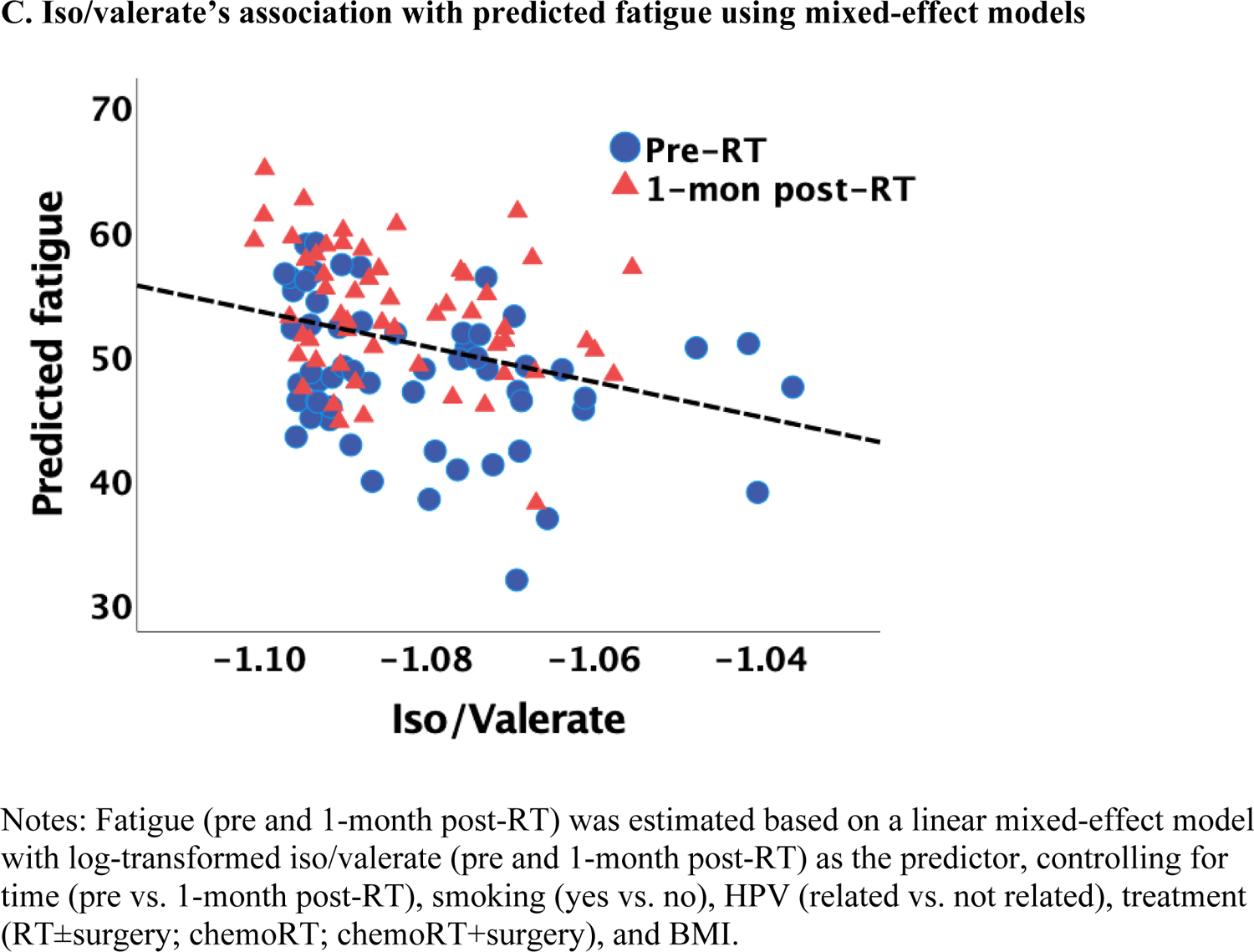

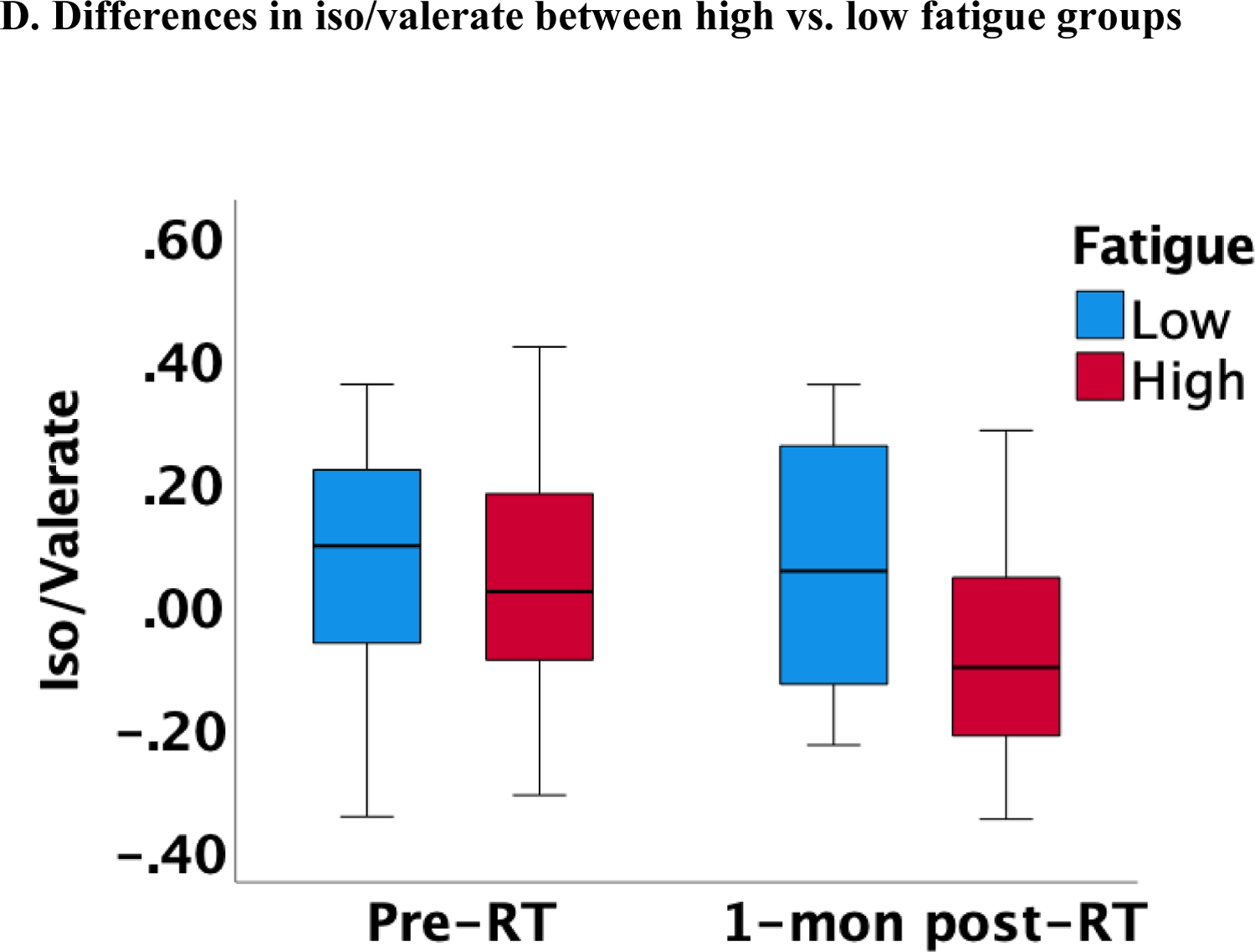

Lower butyrate concentrations were statistically significantly associated with higher fatigue independent of measurement time, controlling for covariates, such as smoking, HPV, treatment, and BMI (estimate=−285.29, p=0.013; Figure 1A). Of note, this association was also significant after adjusting for multiple comparisons (Bonferroni correction: p=0.05/3=0.017). Similar findings were obtained when patients were categorized into high vs. low fatigue groups (two-way ANOVA): butyrate was significantly lower in the group of patients with high fatigue (p=0.012; Figure 1B). No significant associations with fatigue were found for acetate and propionate. Exploratory analyses revealed that lower iso/valerate concentrations were also associated with higher fatigue independent of measurement time and controlling for the same covariates described above (estimate=−18.73, p=0.025; Figure 1C). Similarly, patients in the high fatigue group had significantly lower iso/valerate concentrations than those in the low fatigue group (p=0.017; Figure 1D).

Figure 1.

Association between SCFAs (log-transformed) and fatigue at pre and 1-month post-radiotherapy (RT)

As the MFI-20 has five dimensions, we also explored whether the association between each of the five dimensions and butyrate (data not shown). Controlling for the same covariates, we found that general fatigue, physical fatigue, and reduced motivation were significantly associated with peripheral butyrate concentrations (p = 0.012 to 0.003).

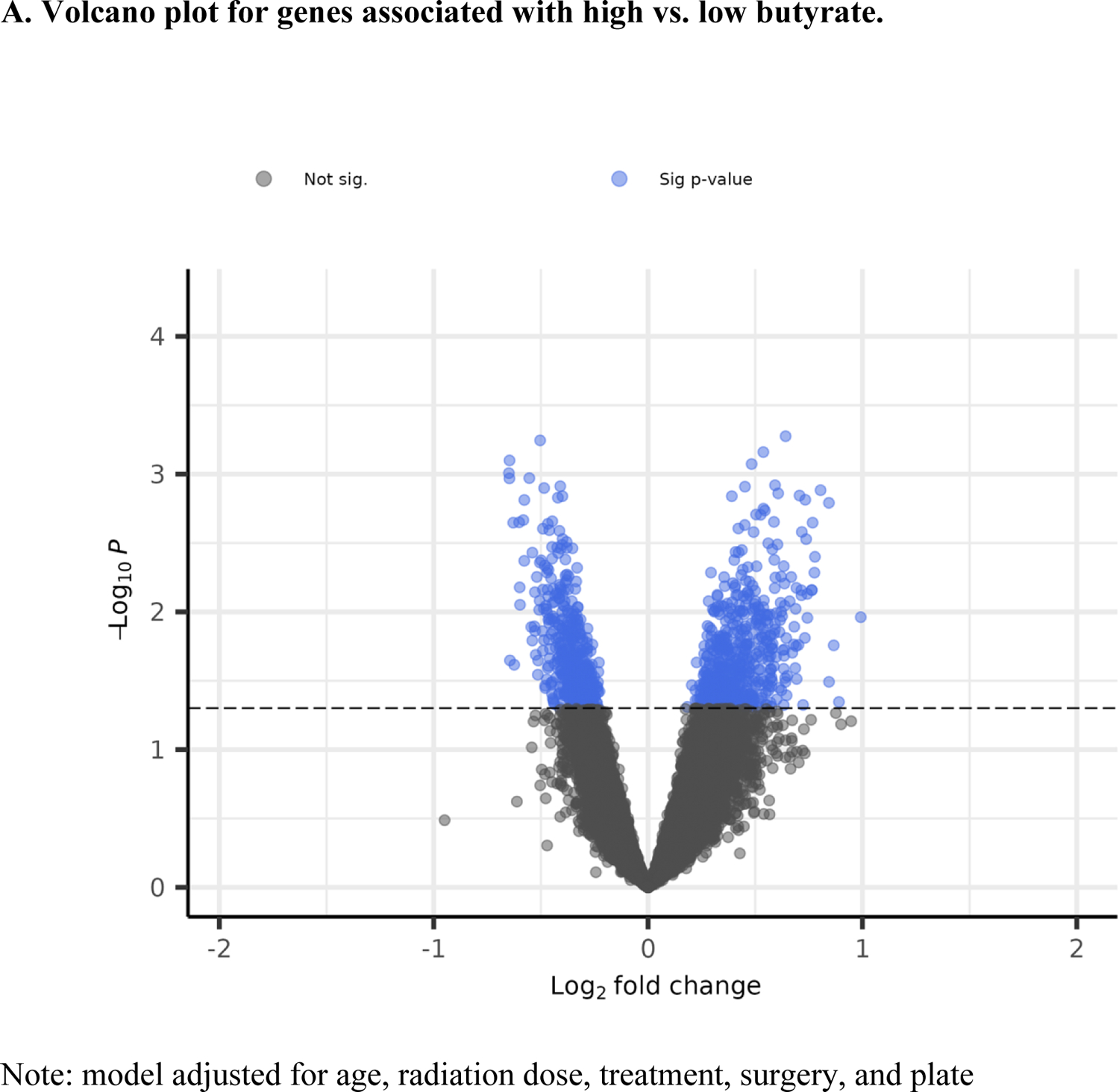

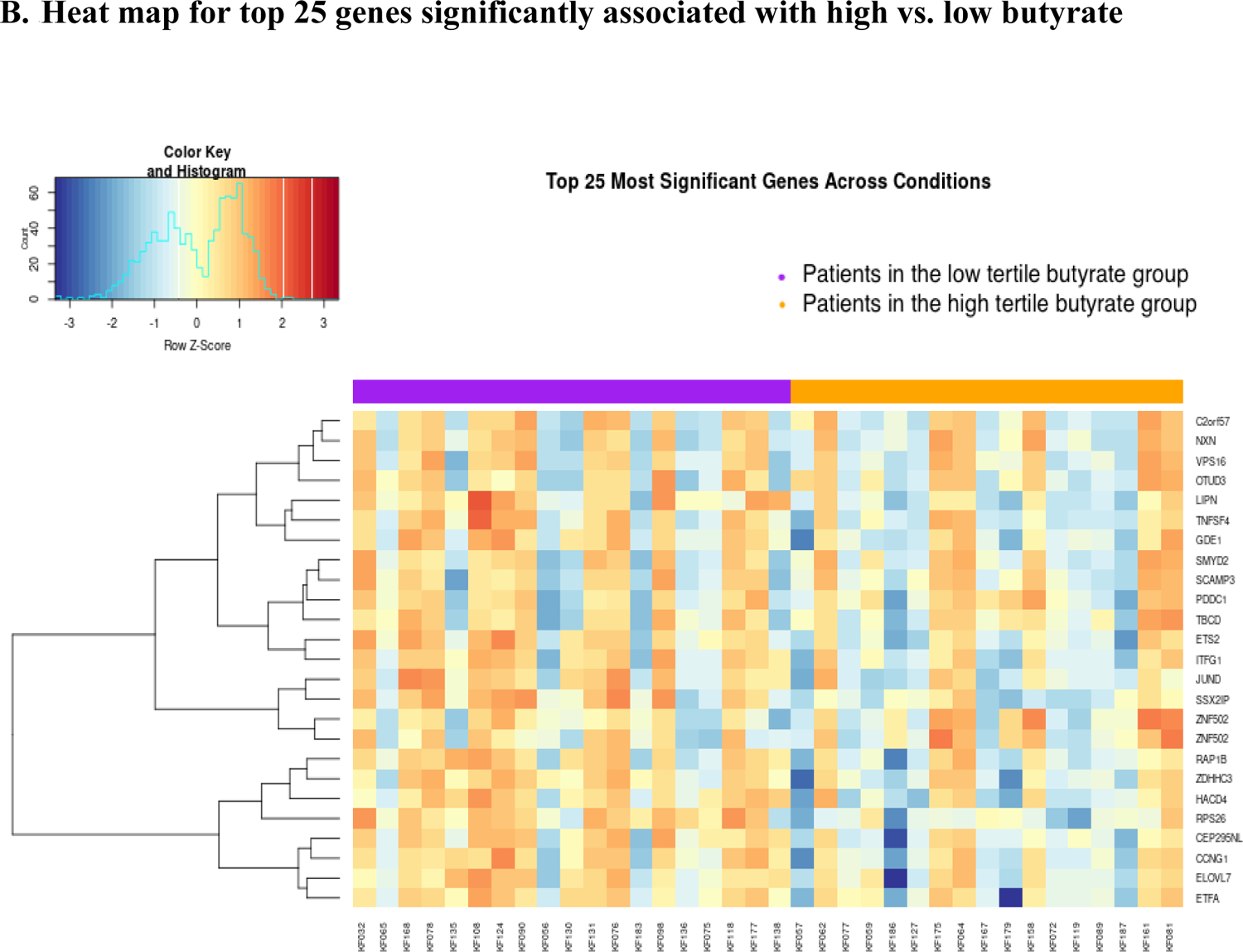

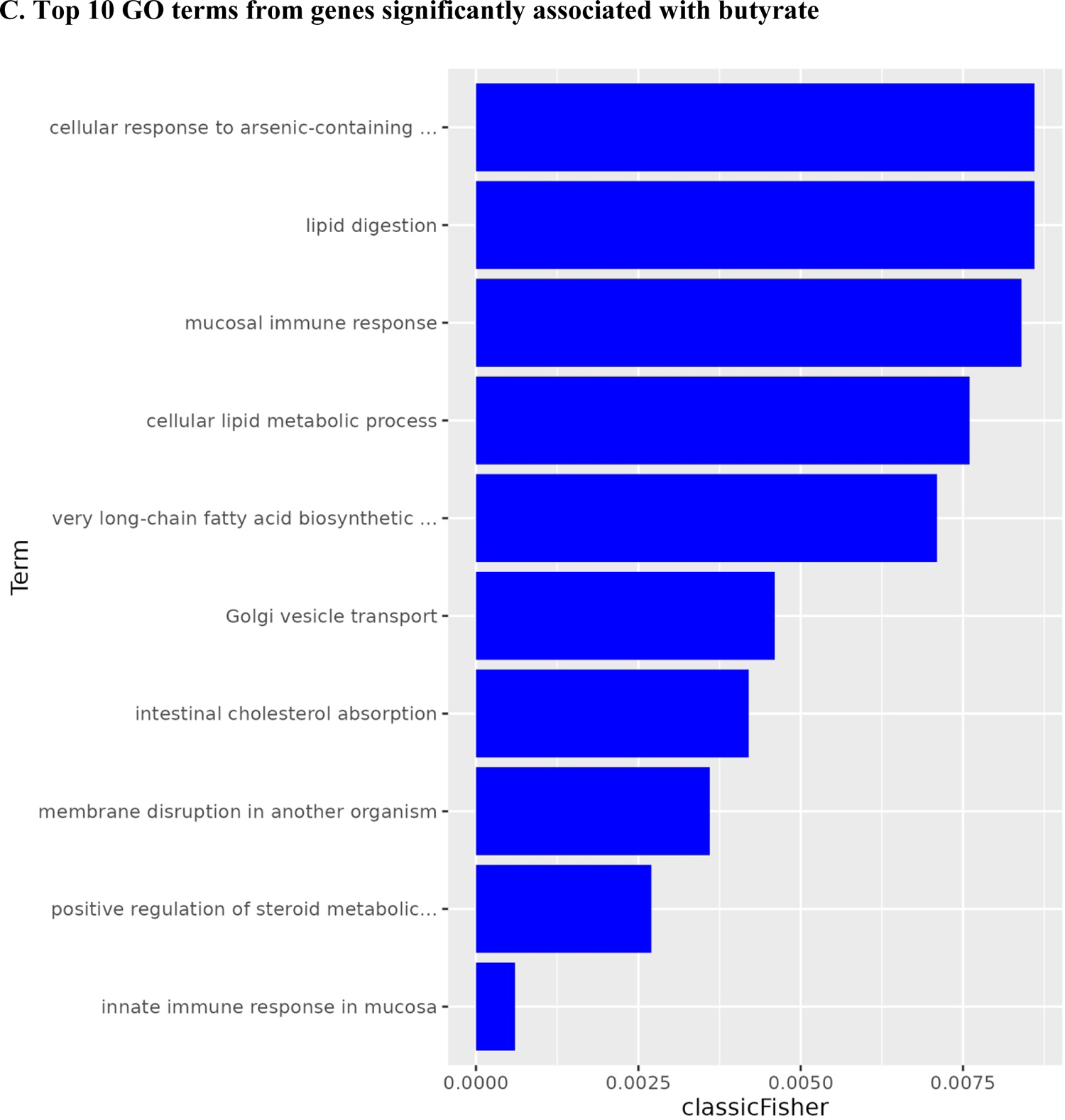

Association between SCFAs and gene expression at pre-treatment

A total of 50 patients had gene expression data at baseline. Based on the significant association between butyrate and fatigue, we compared gene expression at pre-treatment in patients with butyrate concentrations in the top 33% (n=19) vs. the bottom 33% (n=17). Results from the logistic regression models identified 1,088 genes statistically significantly associated with butyrate status (high vs. low), controlling for covariates (i.e., age, radiation dose, treatment, surgery, and assay plate). Among them, 559 were up-regulated, and 489 were down-regulated (Figure 2A). The heat map shows a different pattern of the top 25 genes in the low and high butyrate quantiles (Figure 2B). A total of 138 GO terms were significant at p<0.05 (Supplemental Table 2). The top 10 GO terms from the enrichment analyses of the significant genes revealed the involvement of innate immune responses, lipid and fatty acid biosynthetic process, and metabolic process (Figure 2C).

Figure 2.

Volcano plot, heat map, and bar plot for genes associated with high vs. low butyrate status at pre-treatment.

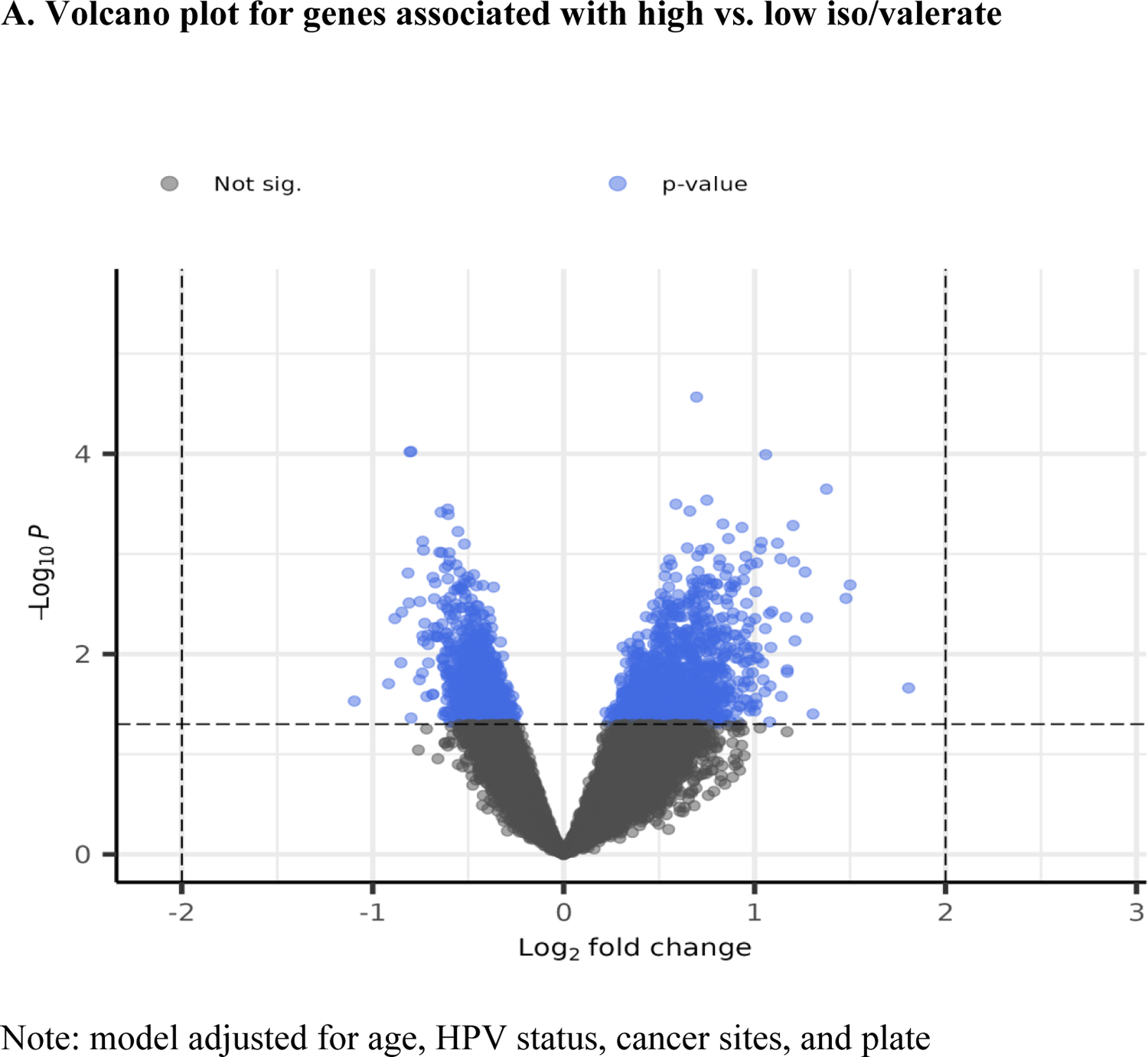

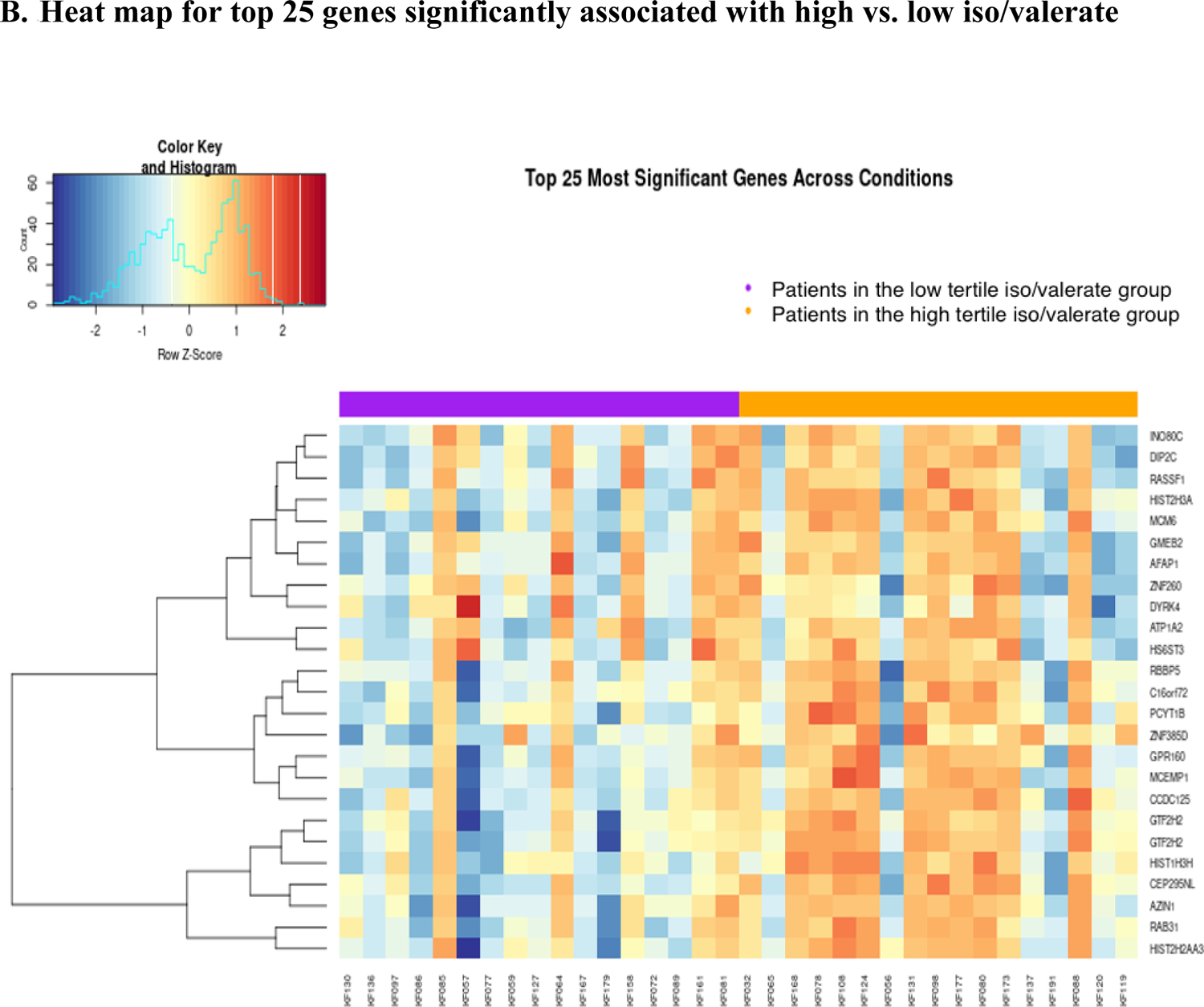

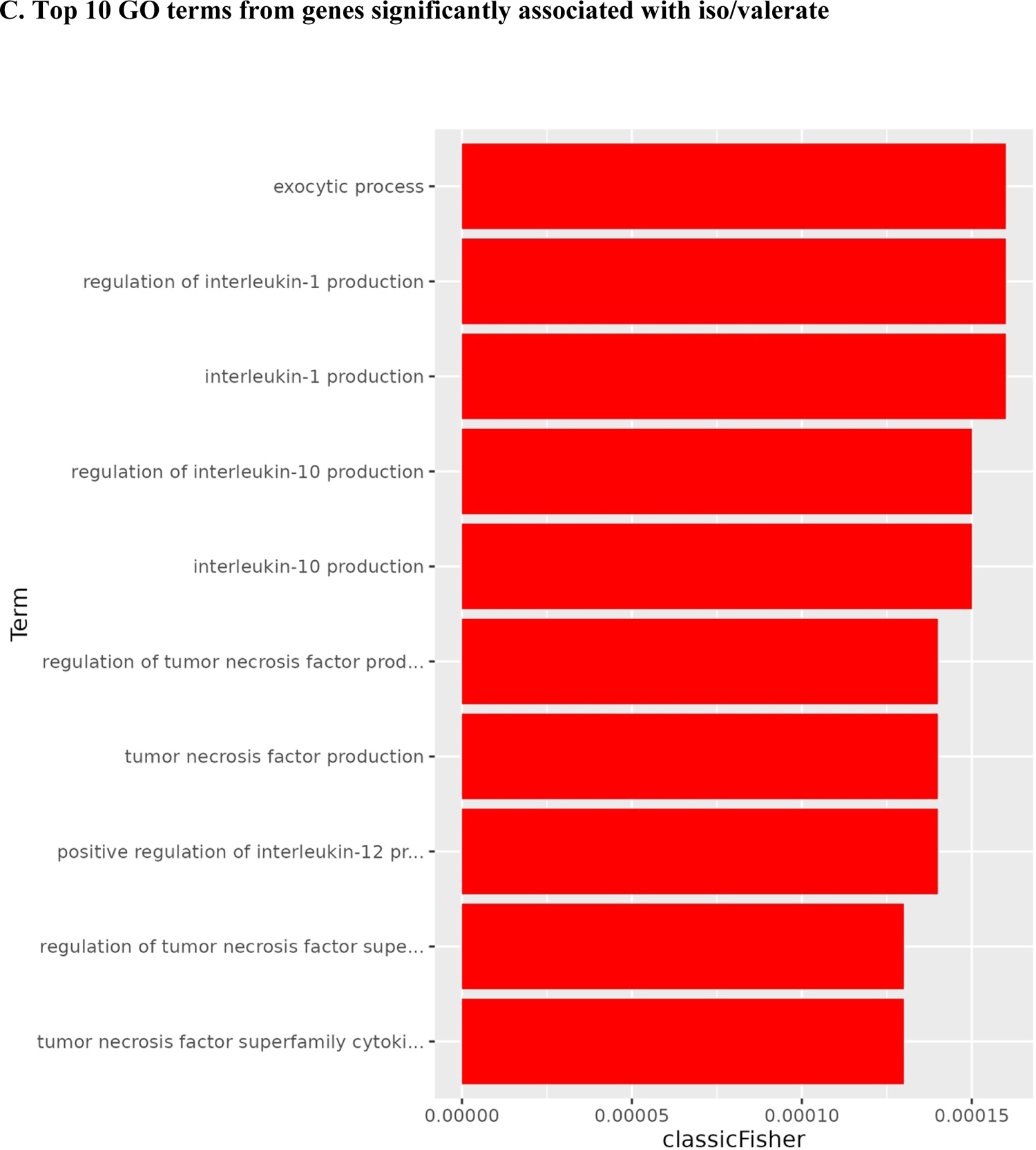

After categorizing iso/valerate into three quantiles, 17 patients were in the low quantile and 17 in the high. Logistic regression results showed that 881 genes were significantly associated with iso/valerate, controlling for covariates (i.e., age, HPV status, cancer sites, and assay plate).

Among them, 547 were up-regulated, and 334 were down-regulated (Figure 3A). The heat map shows a different pattern of the top 25 genes in the low and high iso/valerate quantiles (Figure 3B). A total of 465 GO terms were significant (p<0.05; Supplemental Table 3). Table 1 shows the top 20 GO terms from the enrichment analyses of the significant genes; most of them were cytokine-related (e.g., tumor necrosis factor [TNF], interleukin (IL)-12, IL-1, IL-10; Figure 3C). Of note, 14 of the 20 terms had an FDR <0.05.

Figure 3.

Volcano plot and heat map for gene associated with iso/valerate

Table 1.

Baseline demographic and clinical characteristics of the study participants (N=59)

| Variables | Mean ± SD or N (%) | |

|---|---|---|

| Age (years) | 58.61 ± 9.73 | |

| Sex | Men | 42 (71) |

| Women | 17 (29) | |

| Race | White | 50 (85) |

| Non-White | 9 (15) | |

| Marital statusa | Married | 45 (76) |

| Unmarried | 14 (24) | |

| History of tobacco use | No | 21 (36) |

| Yes | 38 (64) | |

| History of alcohol use* | No | 29 (50) |

| Yes | 29 (50) | |

| BMI, kg/m2 | 27.03 ± 4.94 | |

| Comorbiditiesb | 0 | 37 (63) |

| >=1 | 22 (37) | |

| Antidepressants* | No | 45 (79) |

| Yes | 12 (21) | |

| Cancer site | Oropharynx | 32 (54) |

| Other | 27 (46) | |

| Stage | ≤ III | 16 (27) |

| IV | 43 (73) | |

| HPV status | HPV related | 31 (52) |

| HPV unrelated | 28 (48) | |

| Treatment | RT | 2 (3) |

| RT + Surgery | 13 (22) | |

| ChemoRT | 27 (46) | |

| ChemoRT + Surgery | 17 (29) | |

| Chemotherapy | Cisplatin | 30 (68) |

| Carboplatin/Paclitaxel | 11 (25) | |

| Other | 3 (7) | |

| Radiation dose (Gy) | 66 ± 5 | |

| Feeding tubes* | No | 27 (47) |

| Yes | 30 (53) | |

Note. BMI = Body Mass Index, HPV = Human papillomavirus, RT = Radiation Therapy, SD = Standard deviation.

Having missing data: History of alcohol use (1); Antidepressants (2); Feeding tubes (2).

Married includes patients married or living as married; Unmarried includes patients single, separated, divorced, or widowed.

Comorbidities was assessed using the Charlson Comorbidity Index excluding tumor.

Discussion

The present study found that lower plasma butyrate and iso/valerate concentrations were associated with higher fatigue during and immediately after cancer treatment. Moreover, high vs. low butyrate or iso/valerate was associated with differentially expressed gene profiles enriched for inflammatory, immunological, and metabolic processes, which have been associated with fatigue in HNC patients in previous studies. Given that the microbiome is a major source of SCFAs, these findings suggest that the gut microbiome may play a role in symptoms of fatigue, further implicating the potential of SCFAs and inflammation in the gut-brain axis among cancer populations.

As hypothesized, our data revealed that lower plasma concentrations of SCFAs, butyrate and iso/valerate, were associated with higher fatigue. Butyrate, an important SCFA, can promote immunomodulatory and anti-inflammatory responses by binding to G protein-coupled receptors that are abundant on the surface of gut epithelial and immune cells.11,12 Butyrate, along with other SCFAs, can also function as a HDAC inhibitor, which in turn can regulate cytokine expression and lead to suppression of pro-inflammatory effects.39,40 For example, in patients with ulcerative colitis, butyrate administrated via enema inhibited NF-κB activation in lamina propria macrophages.41 Additionally, butyrate can pass through the blood-brain barrier and has been implicated in brain homeostasis14 and may have therapeutic potential for neurodegenerative diseases and psychological disorders.42

While similar studies among cancer populations of fatigue are lacking, a comparable trend was observed for cachectic cancer patients, for whom fecal acetate concentrations were significantly reduced.43 This decreased SCFA (i.e., acetate and butyrate) in cachexia was also supported by a preclinical study using cachectic mice.44 Interestingly, SCFAs (i.e., butyrate) have been shown to suppress tumor growth45 and have been associated with longer progression-free cancer survival,46 suggesting higher SCFAs may be associated not only with reduced fatigue but also anti-tumor properties. In addition, there is some evidence for an association between fatigue and SCFAs in non-cancer patients. For instance, lower plasma SCFAs, including butyrate and iso/valerate, were associated with increased leg muscle fatigue in obese adults.47 Moreover, fecal butyrate concentrations were lower for patients with chronic fatigue syndrome compared to healthy controls.48 Although our study found a significant association between butyrate, as well as iso/valerate, with fatigue, other SCFAs, such as acetate and propionate, have been linked with fatigue-related symptoms. For instance, a lower concentration of acetate was found in patients with chronic fatigue syndrome, and propionate was associated with shorter uninterrupted sleep in infants49 and higher depression scores in adult women.50 Thus, future large studies are warranted to further examine the scope and reproducibility of the findings.

Regarding the functional pathways associated with SCFAs and their relationship with fatigue, we examined the gene expression profile associated with high vs. low SCFAs using blood leukocytes. Among the top 20 GO terms from genes significantly associated with high vs low butyrate or iso/valerate, the majority were related to inflammatory responses (cytokines), lipid and fatty acid biosynthetic process, and metabolic process. SCFAs, such as butyrate, are considered to have various beneficial effects on host health and metabolism. One of the major beneficial effects is its anti-inflammatory effect. Animal studies have revealed that mice without SCFA receptors had greater inflammatory responses to a carcinogenic stimulus than wild-type mice,51 while the addition of butyrate directly or indirectly via dietary fiber reduced inflammation.51–54 Our data from the host gene expression profiles further supported SCFAs’ role in immune and inflammatory modulation. Combined with previous findings on inflammatory mechanisms of cancer related behavior symptoms,55 including fatigue,31 the data suggest that increasing SCFAs, such as by diet or SCFA-producing taxa, may reduce inflammation and subsequently decrease fatigue and other inflammation-related conditions among cancer patients.

Patients with HNC often experience side effects from cancer and its treatment. Those side effects, such as oral mucositis, dry mouth, difficulty of opening mouth, and oral pain, significantly impact patients’ diet, leading to not only malnutrition and weight loss but also altered dietary intake, which may contribute to changes in the microbiome and SCFAs. While we did not find literature on the changes in SCFAs over cancer treatment, several studies on weight loss did report that people with weight loss had decreased concentrations of SCFAs.32,56

The findings from our study suggest clinical considerations for reducing fatigue and related symptoms via SCFAs. As suggested by experimental studies in laboratory animals, increasing the intake of high-fiber food or food rich in natural sources of SCFAs may increase SCFAs production and improve neuroinflammation.57 A second approach might be to identify SCFAs-producing taxa, as SCFAs are mostly produced by the gut microbiome.58 Different SCFAs are produced by different taxa. For instance, species of the Firmicutes phylum are associated with butyrate production, whereas species of the Bacteroidetes phylum are more likely to produce acetate and propionates.59,60 Indeed, our group is currently examining taxa and their potential association with SCFAs and neuropsychological symptoms, including fatigue. A third approach is related to the direct oral intake of SCFAs, which has shown positive effects in reducing mucosal inflammation and maintaining remission in patients with inflammatory bowel disease.61,62 Studies have also found alternative approaches, such as orally administered butyrate-releasing xylan derivative, which is fermented by gut bacteria into xylooligosaccharides to produce SCFAs.63 A combination of high-fiber food, SCFAs-producing taxa, and SCFAs could also be considered, as suggested by studies in inflammatory bowel diseases.64 Nevertheless, more research is needed before clinical recommendations can be implemented.

Several limitations should be noted. Although we identified the association between lower SCFAs concentrations and higher fatigue, our study cannot establish a direct link between the gut microbiome and SCFAs due to its observational nature. However, our previous study on the gut microbiome showed lower SCFA-producing taxa among those with high fatigue.26 Other evidence also suggests low SCFAs-producing taxa among patients with chronic fatigue syndrome.48 Taken together, this evidence indicates a potential link between the gut microbiome and SCFAs. Nonetheless, whether increasing SCFA-producing taxa may increase SCFA and decrease inflammation still need more investigation. Another limitation is that we only assessed SCFA concentrations in peripheral blood but not in fecal samples. Given the mixed literature on testing either blood or fecal samples, future studies may further examine the differences between blood and fecal SCFAs. The relatively small sample size may limit our capability to conduct stratified analyses by sex and other potential effect modifiers. For instance, we compared whether chemotherapy may influence fatigue or SCFAs, and we did not find any significant effects of chemotherapy on fatigue or SCFAs in pre- and post-treatment. We also only had gene expression data at pre-RT, and multiple comparisons were not correct for due to the small sample size. However, the ANOVA did not show a significant effect of time or the interaction of time and fatigue, while the main effect of fatigue on SCFA was significant. Finally, data on diet and gastrointestinal diseases/conditions were not collected and may have had influence on the gut microbiome and subsequently SCFAs.

Conclusions

In the current study, we found that lower butyrate and iso/valerate were associated with higher fatigue among patients with HNC. Our peripheral gene expression analyses further showed that butyrate and iso/valerate may contribute to fatigue pathophysiology via the involvement of immune/inflammatory responses, lipid and fatty acid biosynthetic processes, and metabolic processes. In addition, our data showed that plasma concentrations of SCFAs, propionate and iso/valerate, decreased after cancer treatment with RT. Given the beneficial role of SCFAs in preventing inflammation and promoting host health, further large studies on SCFAs are warranted to verify our findings. Investigating potential approaches to increase SCFAs, such as via SCFA supplements, high-fiber food, and SCFA-producing taxa, are also needed.

Supplementary Material

Highlights:

Lower blood butyrate concentrations were associated with higher fatigue.

Lower blood iso/valerate concentrations were associated with higher fatigue.

High vs. low SCFAs were linked with inflammation and lipid metabolism gene pathways.

Funding:

The study was supported by NIH/NINR K99/R00NR014587, NIH/NINR R01NR015783, NIH/NINR R01NR020188, and NIH/NCI P30CA138292.

V. Fedirko is supported by the Cancer Prevention and Research Institute of Texas (CPRIT) Rising Stars Award (Grant ID RR200056).

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement:

None.

References

- 1.Collins SM, Surette M, Bercik P. The interplay between the intestinal microbiota and the brain. Nature reviews Microbiology. 2012;10(11):735–742. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Hsiao EY, McBride SW, Hsien S, et al. Microbiota modulate behavioral and physiological abnormalities associated with neurodevelopmental disorders. Cell. 2013;155(7):14511463. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Tillisch K, Labus J, Kilpatrick L, et al. Consumption of fermented milk product with probiotic modulates brain activity. Gastroenterology. 2013;144(7):1394–1401, 1401.e1391–1394. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Steenbergen L, Sellaro R, van Hemert S, Bosch JA, Colzato LS. A randomized controlled trial to test the effect of multispecies probiotics on cognitive reactivity to sad mood. Brain Behav Immun. 2015;48:258–264. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jordan KR, Loman BR, Bailey MT, Pyter LM. Gut microbiota-immune-brain interactions in chemotherapy-associated behavioral comorbidities. Cancer. 2018;124(20):3990–3999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Giloteaux L, Goodrich JK, Walters WA, Levine SM, Ley RE, Hanson MR. Reduced diversity and altered composition of the gut microbiome in individuals with myalgic encephalomyelitis/chronic fatigue syndrome. Microbiome. 2016;4(1):30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Shukla SK, Cook D, Meyer J, et al. Changes in Gut and Plasma Microbiome following Exercise Challenge in Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome (ME/CFS). PLoS One. 2015;10(12):e0145453. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cheung SG, Goldenthal AR, Uhlemann AC, Mann JJ, Miller JM, Sublette ME. Systematic Review of Gut Microbiota and Major Depression. Front Psychiatry. 2019;10:34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Sarkar A, Harty S, Lehto SM, et al. The Microbiome in Psychology and Cognitive Neuroscience. Trends in cognitive sciences. 2018;22(7):611–636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.den Besten G, van Eunen K, Groen AK, Venema K, Reijngoud D-J, Bakker BM. The role of short-chain fatty acids in the interplay between diet, gut microbiota, and host energy metabolism. Journal of lipid research. 2013;54(9):2325–2340. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yarandi SS, Peterson DA, Treisman GJ, Moran TH, Pasricha PJ. Modulatory Effects of Gut Microbiota on the Central Nervous System: How Gut Could Play a Role in Neuropsychiatric Health and Diseases. Journal of neurogastroenterology and motility. 2016;22(2):201–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Valles-Colomer M, Falony G, Darzi Y, et al. The neuroactive potential of the human gut microbiota in quality of life and depression. Nature Microbiology. 2019;4(4):623–632. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braniste V, Al-Asmakh M, Kowal C, et al. The gut microbiota influences blood-brain barrier permeability in mice. Science Translational Medicine. 2014;6(263):263ra158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Silva YP, Bernardi A, Frozza RL. The Role of Short-Chain Fatty Acids From Gut Microbiota in Gut-Brain Communication. Frontiers in Endocrinology. 2020;11(25). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Stilling RM, van de Wouw M, Clarke G, Stanton C, Dinan TG, Cryan JF. The neuropharmacology of butyrate: The bread and butter of the microbiota-gut-brain axis? Neurochem Int. 2016;99:110–132. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Thiagalingam S, Cheng KH, Lee HJ, Mineva N, Thiagalingam A, Ponte JF. Histone deacetylases: unique players in shaping the epigenetic histone code. Annals of the New York Academy of Sciences. 2003;983:84–100. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Sanderson IR. Short Chain Fatty Acid Regulation of Signaling Genes Expressed by the Intestinal Epithelium. The Journal of nutrition. 2004;134(9):2450S–2454S. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Luo CH, Lai AC, Chang YJ. Butyrate inhibits Staphylococcus aureus-aggravated dermal IL-33 expression and skin inflammation through histone deacetylase inhibition. Front Immunol. 2023;14:1114699. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martinowich K, Lu B. Interaction between BDNF and Serotonin: Role in Mood Disorders. Neuropsychopharmacology. 2008;33(1):73–83. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bower JE, Ganz PA, Aziz N, Fahey JL. Fatigue and proinflammatory cytokine activity in breast cancer survivors. Psychosom Med. 2002;64(4):604–611. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Zielinski MR, Kim Y, Karpova SA, McCarley RW, Strecker RE, Gerashchenko D. Chronic sleep restriction elevates brain interleukin-1 beta and tumor necrosis factor-alpha and attenuates brain-derived neurotrophic factor expression. Neuroscience letters. 2014;580:27–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Salim S. Oxidative stress and psychological disorders. Current neuropharmacology. 2014;12(2):140–147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Xiao C, Beitler JJ, Peng G, et al. Epigenetic age acceleration, fatigue, and inflammation in patients undergoing radiation therapy for head and neck cancer: A longitudinal study. Cancer. 2021;n/a(n/a). [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Xiao C, Beitler JJ, Higgins KA, et al. Differential regulation of NF-kB and IRF target genes as they relate to fatigue in patients with head and neck cancer. Brain Behav Immun. 2018;74:291–295. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Bai J, Bruner DW, Fedirko V, et al. Gut Microbiome Associated with the Psychoneurological Symptom Cluster in Patients with Head and Neck Cancers. Cancers (Basel). 2020;12(9). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Xiao C, Fedirko V, Beitler J, et al. The role of the gut microbiome in cancer-related fatigue: pilot study on epigenetic mechanisms. Support Care Cancer. 2020. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Zhang C, Zhang M, Wang S, et al. Interactions between gut microbiota, host genetics and diet relevant to development of metabolic syndromes in mice. The ISME journal. 2010;4(2):232–241. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.David LA, Maurice CF, Carmody RN, et al. Diet rapidly and reproducibly alters the human gut microbiome. Nature. 2014;505(7484):559–563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Smets EM, Garssen B, Bonke B, De Haes JC. The Multidimensional Fatigue Inventory (MFI) psychometric qualities of an instrument to assess fatigue. J Psychosom Res. 1995;39(3):315–325. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Schubert C, Hong S, Natarajan L, Mills PJ, Dimsdale JE. The association between fatigue and inflammatory marker levels in cancer patients: a quantitative review. Brain Behav Immun. 2007;21(4):413–427. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Xiao C, Beitler JJ, Higgins KA, et al. Fatigue is associated with inflammation in patients with head and neck cancer before and after intensity-modulated radiation therapy. Brain Behav Immun. 2016;52:145–152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Sowah SA, Hirche F, Milanese A, et al. Changes in Plasma Short-Chain Fatty Acid Levels after Dietary Weight Loss Among Overweight and Obese Adults over 50 Weeks. Nutrients. 2020;12(2):452. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Nishitsuji K, Xiao J, Nagatomo R, et al. Analysis of the gut microbiome and plasma short-chain fatty acid profiles in a spontaneous mouse model of metabolic syndrome. Scientific reports. 2017;7(1):15876. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Müller M, Hernández MAG, Goossens GH, et al. Circulating but not faecal short-chain fatty acids are related to insulin sensitivity, lipolysis and GLP-1 concentrations in humans. Scientific reports. 2019;9(1):12515. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Sarah K, Nicolaas D, John T, Gabriella TH, Engelen M. Reduced Short-Chain Fatty Acid (SCFA) Plasma Concentrations Are Associated with Decreased Psychological Well-Being in Clinically Stable Congestive Heart Failure Patients. Current Developments in Nutrition. 2020;4(Supplement_2):42–42.32258998 [Google Scholar]

- 36.Carvalho BS, Irizarry RA. A framework for oligonucleotide microarray preprocessing. Bioinformatics (Oxford, England). 2010;26(19):2363–2367. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Irizarry RA, Bolstad BM, Collin F, Cope LM, Hobbs B, Speed TP. Summaries of Affymetrix GeneChip probe level data. Nucleic Acids Res. 2003;31(4):e15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Andic F, Miller AH, Brown G, et al. Instruments for determining clinically relevant fatigue in breast cancer patients during radiotherapy. Breast cancer (Tokyo, Japan). 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Chang PV, Hao L, Offermanns S, Medzhitov R. The microbial metabolite butyrate regulates intestinal macrophage function via histone deacetylase inhibition. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(6):2247–2252. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Luceri C, Femia AP, Fazi M, et al. Effect of butyrate enemas on gene expression profiles and endoscopic/histopathological scores of diverted colorectal mucosa: A randomized trial. Digestive and Liver Disease. 2016;48(1):27–33. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Lührs H, Gerke T, Müller JG, et al. Butyrate inhibits NF-kappaB activation in lamina propria macrophages of patients with ulcerative colitis. Scand J Gastroenterol. 2002;37(4):458–466. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Bourassa MW, Alim I, Bultman SJ, Ratan RR. Butyrate, neuroepigenetics and the gut microbiome: Can a high fiber diet improve brain health? Neuroscience letters. 2016;625:56–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Ubachs J, Ziemons J, Soons Z, et al. Gut microbiota and short-chain fatty acid alterations in cachectic cancer patients. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle. 2021;12(6):2007–2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pötgens SA, Thibaut MM, Joudiou N, et al. Multi-compartment metabolomics and metagenomics reveal major hepatic and intestinal disturbances in cancer cachectic mice. Journal of cachexia, sarcopenia and muscle. 2021;12(2):456–475. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Krishna S, Brown N, Faller DV, Spanjaard RA. Differential effects of short-chain fatty acids on head and neck squamous carcinoma cells. The Laryngoscope. 2002;112(4):645650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Nomura M, Nagatomo R, Doi K, et al. Association of Short-Chain Fatty Acids in the Gut Microbiome With Clinical Response to Treatment With Nivolumab or Pembrolizumab in Patients With Solid Cancer Tumors. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3(4):e202895. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wierzchowska-McNew R, Engelen MP, Knoop KD, Kirschner SK, Cruthirds CL, Deutz NE. Lower Plasma Short-Chain Fatty Acids Are Associated With Increased Leg Muscle Fatigue in (Morbidly) Obese Adults. Current Developments in Nutrition. 2021;5(Supplement_2):1258–1258. [Google Scholar]

- 48.Guo C, Che X, Briese T, et al. Deficient butyrate-producing capacity in the gut microbiome of Myalgic Encephalomyelitis/Chronic Fatigue Syndrome patients is associated with fatigue symptoms. 2021.

- 49.Heath A-LM, Haszard JJ, Galland BC, et al. Association between the faecal short-chain fatty acid propionate and infant sleep. European journal of clinical nutrition. 2020;74(9):1362–1365. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Skonieczna-Żydecka K, Grochans E, Maciejewska D, et al. Faecal Short Chain Fatty Acids Profile is Changed in Polish Depressive Women. Nutrients. 2018;10(12):1939. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Maslowski KM, Vieira AT, Ng A, et al. Regulation of inflammatory responses by gut microbiota and chemoattractant receptor GPR43. Nature. 2009;461(7268):1282–1286. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Pacheco RG, Esposito CC, Müller LC, et al. Use of butyrate or glutamine in enema solution reduces inflammation and fibrosis in experimental diversion colitis. World J Gastroenterol. 2012;18(32):4278–4287. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Song M, Xia B, Li J. Effects of topical treatment of sodium butyrate and 5-aminosalicylic acid on expression of trefoil factor 3, interleukin 1beta, and nuclear factor kappaB in trinitrobenzene sulphonic acid induced colitis in rats. Postgrad Med J. 2006;82(964):130135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Clarke JM, Young GP, Topping DL, et al. Butyrate delivered by butyrylated starch increases distal colonic epithelial apoptosis in carcinogen-treated rats. Carcinogenesis. 2012;33(1):197–202. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang XS, Shi Q, Williams LA, et al. Inflammatory cytokines are associated with the development of symptom burden in patients with NSCLC undergoing concurrent chemoradiation therapy. Brain Behav Immun. 2010;24(6):968–974. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Sowah SA, Riedl L, Damms-Machado A, et al. Effects of Weight-Loss Interventions on Short-Chain Fatty Acid Concentrations in Blood and Feces of Adults: A Systematic Review. Advances in nutrition (Bethesda, Md). 2019;10(4):673–684. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Matt SM, Allen JM, Lawson MA, Mailing LJ, Woods JA, Johnson RW. Butyrate and Dietary Soluble Fiber Improve Neuroinflammation Associated With Aging in Mice. Front Immunol. 2018;9:1832. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Furusawa Y, Obata Y, Fukuda S, et al. Commensal microbe-derived butyrate induces the differentiation of colonic regulatory T cells. Nature. 2013;504(7480):446–450. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Wang G, Huang S, Wang Y, et al. Bridging intestinal immunity and gut microbiota by metabolites. Cellular and Molecular Life Sciences. 2019;76(20):3917–3937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Louis P, Hold GL, Flint HJ. The gut microbiota, bacterial metabolites and colorectal cancer. Nature Reviews Microbiology. 2014;12(10):661–672. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Facchin S, Vitulo N, Calgaro M, et al. Microbiota changes induced by microencapsulated sodium butyrate in patients with inflammatory bowel disease. Neurogastroenterology & Motility. 2020;32(10):e13914. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Vernero M, De Blasio F, Ribaldone DG, et al. The Usefulness of Microencapsulated Sodium Butyrate Add-On Therapy in Maintaining Remission in Patients with Ulcerative Colitis: A Prospective Observational Study. Journal of Clinical Medicine. 2020;9(12). doi: 10.3390/jcm9123941. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Zha Z, Lv Y, Tang H, et al. An orally administered butyrate-releasing xylan derivative reduces inflammation in dextran sulphate sodium-induced murine colitis. Int J Biol Macromol. 2019. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Recharla N, Geesala R, Shi XZ. Gut Microbial Metabolite Butyrate and Its Therapeutic Role in Inflammatory Bowel Disease: A Literature Review. Nutrients. 2023;15(10). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.