Abstract

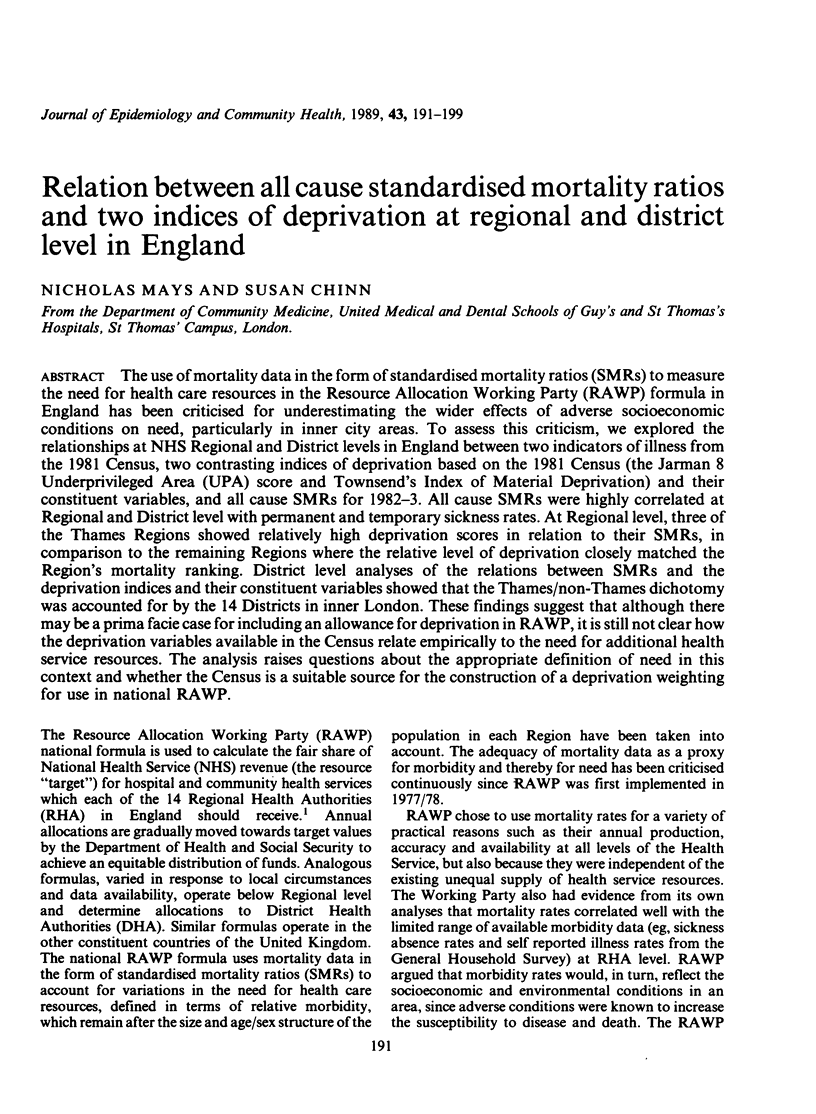

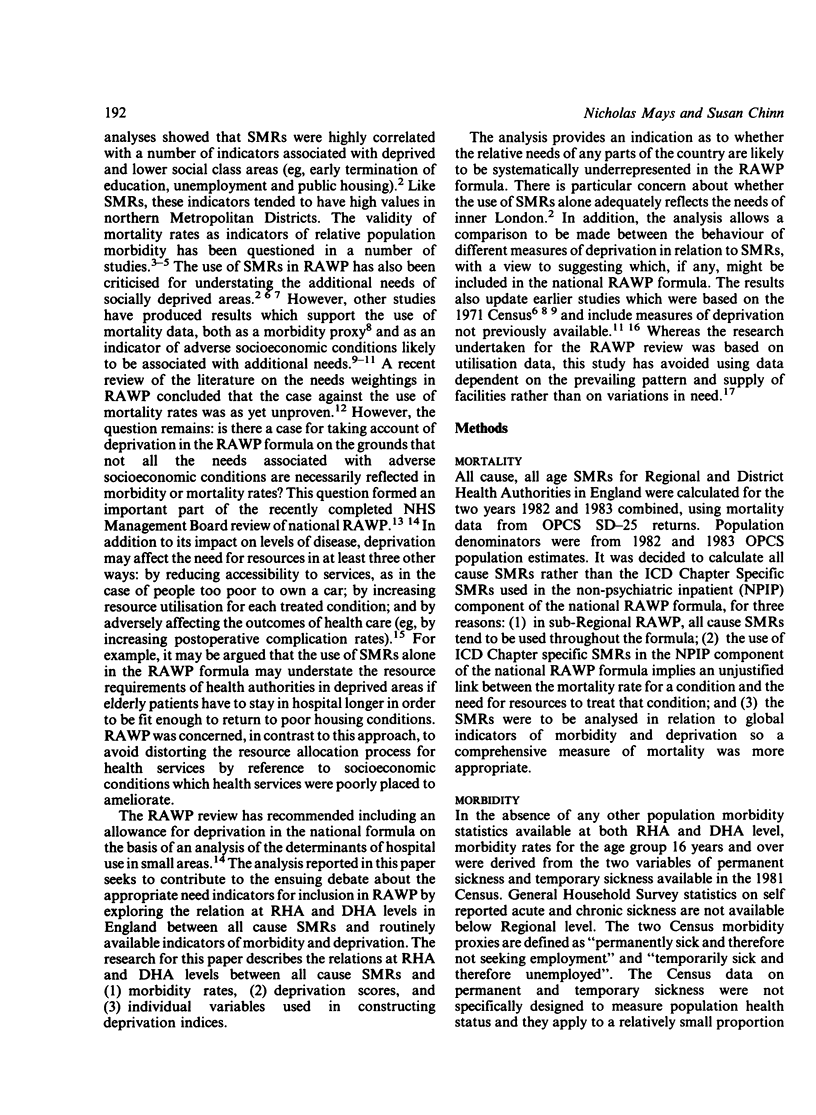

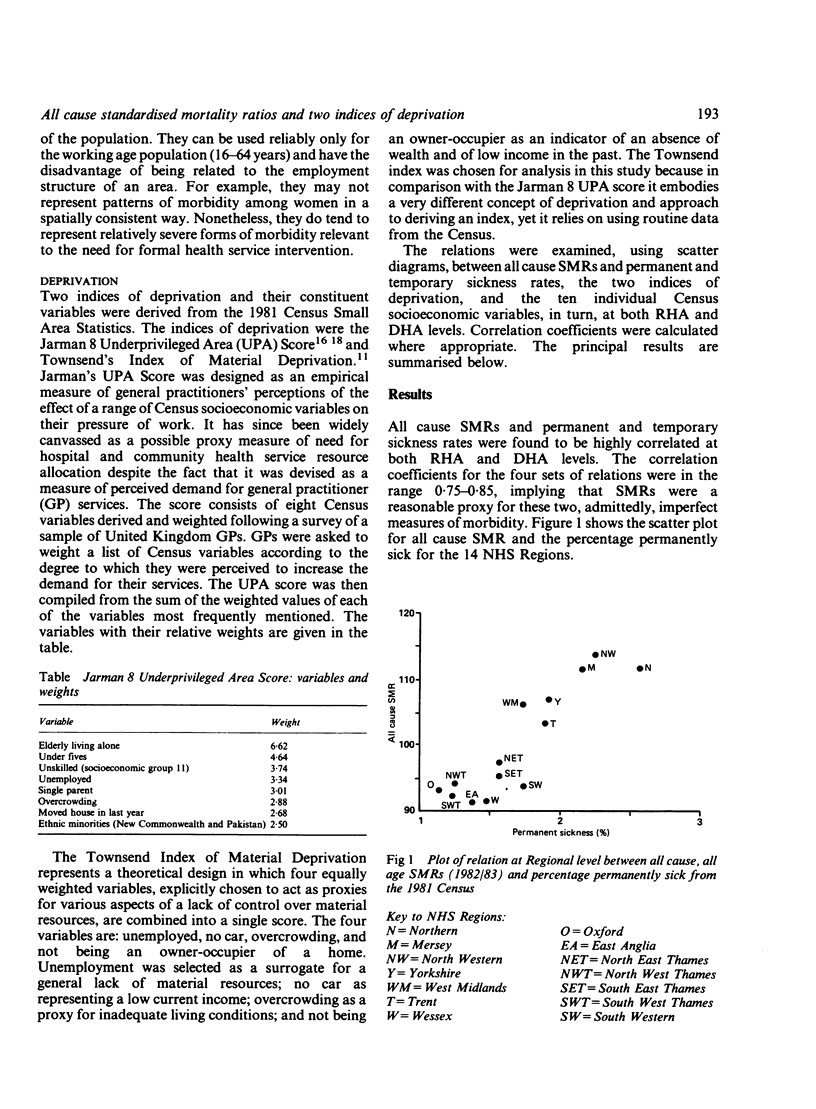

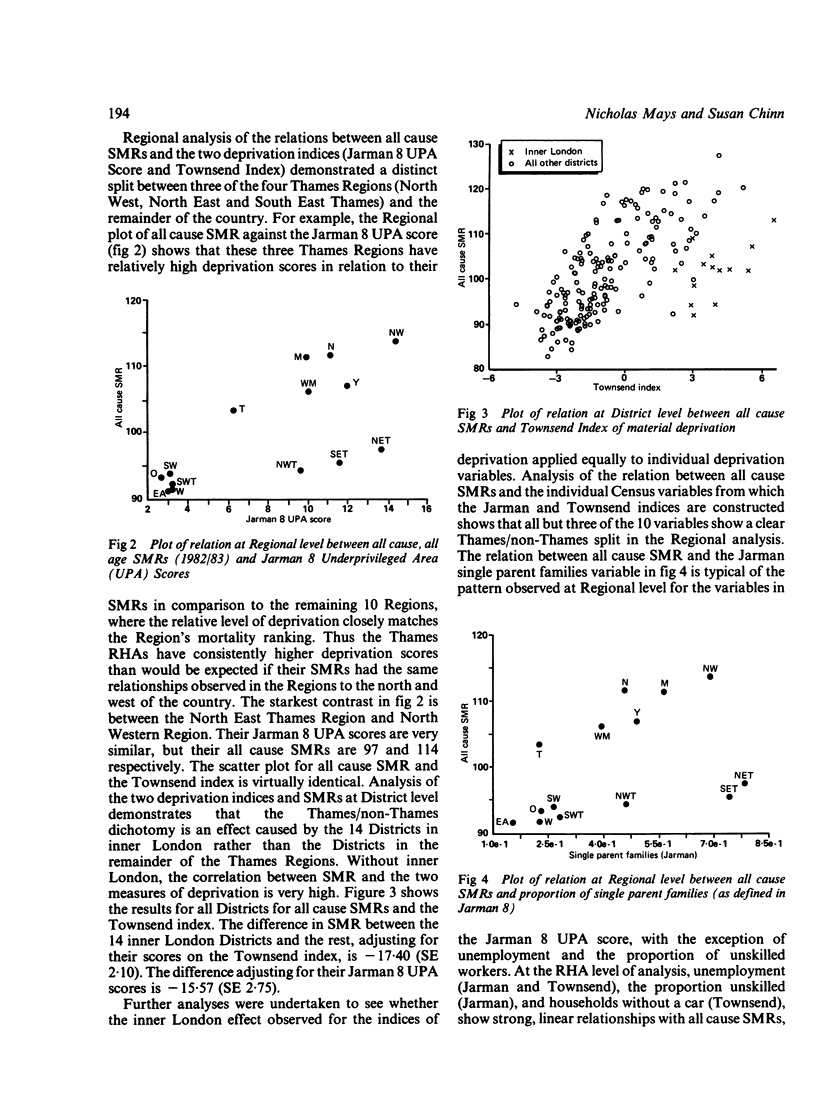

The use of mortality data in the form of standardised mortality ratios (SMRs) to measure the need for health care resources in the Resource Allocation Working Party (RAWP) formula in England has been criticised for underestimating the wider effects of adverse socioeconomic conditions on need, particularly in inner city areas. To assess this criticism, we explored the relationships at NHS Regional and District levels in England between two indicators of illness from the 1981 Census, two contrasting indices of deprivation based on the 1981 Census (the Jarman 8 Underprivileged Area (UPA) score and Townsend's Index of Material Deprivation) and their constituent variables, and all cause SMRs for 1982-3. All cause SMRs were highly correlated at Regional and District level with permanent and temporary sickness rates. At Regional level, three of the Thames Regions showed relatively high deprivation scores in relation to their SMRs, in comparison to the remaining Regions where the relative level of deprivation closely matched the Region's mortality ranking. District level analyses of the relations between SMRs and the deprivation indices and their constituent variables showed that the Thames/non-Thames dichotomy was accounted for by the 14 Districts in inner London. These findings suggest that although there may be a prima facie case for including an allowance for deprivation in RAWP, it is still not clear how the deprivation variables available in the Census relate empirically to the need for additional health service resources. The analysis raises questions about the appropriate definition of need in this context and whether the Census is a suitable source for the construction of a deprivation weighting for use in national RAWP.

Full text

PDF

Selected References

These references are in PubMed. This may not be the complete list of references from this article.

- Balarajan R. On the state of health in inner London. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1986 Mar 29;292(6524):911–914. doi: 10.1136/bmj.292.6524.911. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blaxter M. Evidence on inequality in health from a national survey. Lancet. 1987 Jul 4;2(8549):30–33. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(87)93062-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan M. E., Clare P. H. The relationship between mortality and two indicators of morbidity. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1980 Jun;34(2):134–138. doi: 10.1136/jech.34.2.134. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brennan M. E., Lancashire R. Association of childhood mortality with housing status and unemployment. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1978 Mar;32(1):28–33. doi: 10.1136/jech.32.1.28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carr-Hill R., Eastwood A., Stephenson P. Resource allocation review. Lancet. 1988 Jul 16;2(8603):168–168. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(88)90723-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Carstairs V. Multiple deprivation and health state. Community Med. 1981 Feb;3(1):4–13. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dudley E. F., Beldin R. A., Johnson B. C. Climate, water hardness and coronary heart disease. J Chronic Dis. 1969 Jun;22(1):25–48. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(69)90084-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrer H. P., Moore A., Stevens G. C. The use of mortality data in the report of the Resource Allocation Working Party (H.M.S.O. 1976). Public Health. 1977 Nov;91(6):289–295. doi: 10.1016/s0033-3506(77)80071-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster D. P. Mortality, morbidity, and resource allocation. Lancet. 1977 May 7;1(8019):997–998. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(77)92291-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Forster D. P. The relationships between health needs, socio-environmental indices, general practitioner resources and utilisation. J Chronic Dis. 1979;32(4):333–337. doi: 10.1016/0021-9681(79)90089-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Holland W. W. The RAWP review: pious hopes. Resource Allocation Working Party. Lancet. 1986 Nov 8;2(8515):1087–1090. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(86)90479-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jarman B. Underprivileged areas: validation and distribution of scores. Br Med J (Clin Res Ed) 1984 Dec 8;289(6458):1587–1592. doi: 10.1136/bmj.289.6458.1587. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jones F. A. For debate. The London hospitals scene. Br Med J. 1976 Oct 30;2(6043):1046–1049. doi: 10.1136/bmj.2.6043.1046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morgan M., Mays N., Holland W. W. Can hospital use be a measure of need for health care? J Epidemiol Community Health. 1987 Dec;41(4):269–274. doi: 10.1136/jech.41.4.269. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Newhouse J. P., Friedlander L. J. The relationship between medical resources and measures of health: some additional evidence. J Hum Resour. 1980 Winter;15(2):200–218. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Snaith A. H. Subregional resource allocations in the National Health Service. J Epidemiol Community Health. 1978 Mar;32(1):16–21. doi: 10.1136/jech.32.1.16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]