SUMMARY

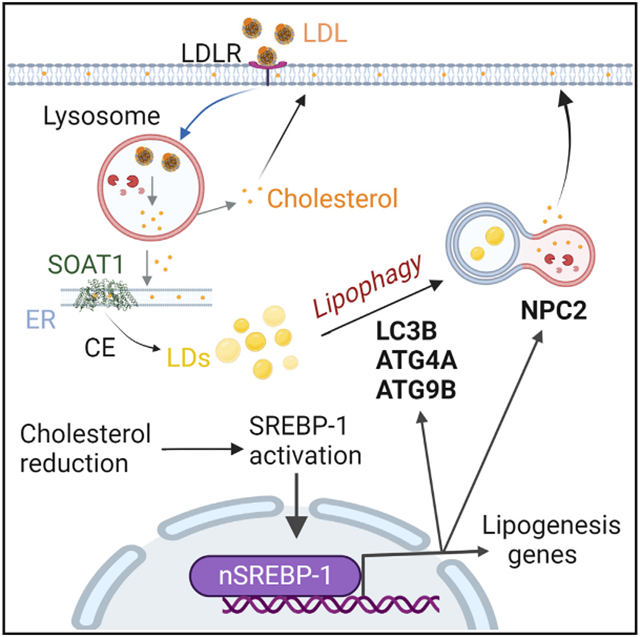

Cholesterol is a structural component of cell membranes. How rapidly growing tumor cells maintain membrane cholesterol homeostasis is poorly understood. Here, we found that glioblastoma (GBM), the most lethal brain tumor, maintains normal levels of membrane cholesterol but with an abundant presence of cholesteryl esters (CEs) in its lipid droplets (LDs). Mechanistically, SREBP-1 (sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1), a master transcription factor that is activated upon cholesterol depletion, upregulates critical autophagic genes, including ATG9B, ATG4A, and LC3B, as well as lysosome cholesterol transporter NPC2. This upregulation promotes LD lipophagy, resulting in the hydrolysis of CEs and the liberation of cholesterol from the lysosomes, thus maintaining plasma membrane cholesterol homeostasis. When this pathway is blocked, GBM cells become quite sensitive to cholesterol deficiency with poor growth in vitro. Our study unravels an SREBP-1-autophagy-LD-CE hydrolysis pathway that plays an important role in maintaining membrane cholesterol homeostasis while providing a potential therapeutic avenue for GBM.

Graphical Abstract

In brief

Geng et al. found that cholesterol deficiency in brain tumor activates SREBP-1, which transcriptionally upregulates the expression of critical autophagy- and lysosome-related genes. The upregulation of autophagy mobilizes cholesterol from cholesterol ester-laden lipid droplets to the plasma membrane to maintain cholesterol homeostasis and to promote tumor growth and survival.

INTRODUCTION

Cells need adequate lipids to produce membranes in order to maintain their viability and growth.1-6 Cholesterol acts as an essential structural component of membrane lipids, playing a critical role in the regulation of membrane integrity and function.5 Cholesterol in the plasma membrane corresponds to ~70% of the total cellular cholesterol levels and accounts for 30%–40% of total plasma membrane lipids.7-10 Cancer cells undergo rapid cell growth, and thus sustaining proper membrane cholesterol levels represents a significant challenge for their viability but also represents a potential leverage point for anti-tumor therapy.5,11

Mammalian cells obtain cholesterol through uptake and de novo synthesis.5 Both pathways are regulated by a family of transcription factors—the sterol regulatory element-binding proteins (SREBPs)—that occur as three isoforms, namely SREBP-1a, −1c, and −2.5,12,13 SREBP activation is negatively regulated by cholesterol.12-14 But whether SREBPs also play other important roles in addition to regulating lipogenesis remains elusive.

Under physiological conditions, cholesterol is transported by low-density lipoprotein (LDL), which circulates in the blood-stream and delivers cholesterol to different organs and tissues via binding to the transmembrane LDL receptor (LDLR).15 LDL is hydrolyzed in the lysosomes to release its associated cholesterol moiety by Niemann Pick disease type C proteins, NPC1 and NPC2, to maintain cellular membrane cholesterol levels.16 Our recent study demonstrated that glioblastoma (GBM), the most lethal primary brain tumor,17-19 is notably dependent on uptake to obtain sufficient cholesterol for its rapid growth.2,20,21 However, in tumor tissues, cancer cells reside in a fluctuating nutrient microenvironment.22-25 How cancer cells maintain adequate cholesterol levels upon the challenge of extracellular cholesterol deficiency is unknown.

Cholesterol occurs in either an un-esterified or esterified form. Esterified cholesterol, or cholesteryl esters (CEs), is stored in lipid droplets (LDs), along with excess fatty acids, which are stored as triglycerides (TGs).5 TG-laden LDs have been demonstrated to be a cellular energy reservoir.25-27 Our recent studies have shown that LDs are largely present in GBM cells,11,25,28-30 and they have also been observed in the tumor cells of colon cancer, clear-cell renal carcinoma, and prostate cancer.31-33 However, the function of LD-stored CEs has rarely been studied.

In this study, by examining clinical GBM specimens and their cells, we found that the LD-stored CEs are hydrolyzed by lipophagy to sustain membrane cholesterol homeostasis when exogenous cholesterol levels are low. We identified that cholesterol deficiency activates SREBP-1, which upregulates the expression of the critical autophagic genes ATG4A, ATG9B, and LC3B, as well as the lysosome cholesterol transporter NPC2, to promote lipophagy and cholesterol release from the lysosomes. We further showed that inhibiting lipophagy can antagonize GBM growth in vitro.

RESULTS

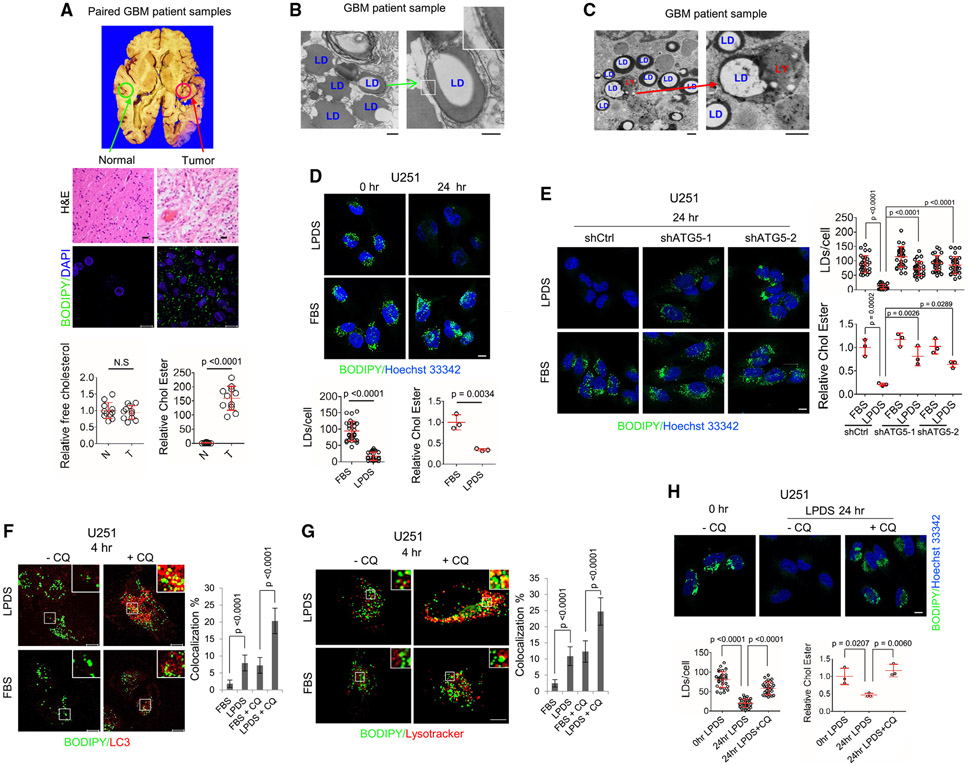

Esterified cholesterol, not free cholesterol, is abundant in GBM tissues vs. healthy brain tissues

Recent studies have shown that cancer cell lipid metabolism is altered compared with healthy cells,5,20,34 but differences in the distribution of cholesterol between tumor cells and those of healthy tissues has rarely been reported. To explore this issue, we firstly examined cholesterol and CE levels in 11 paired GBM tumor vs. contralateral healthy brain tissues from patient autopsy samples (Figure 1A, top panel). We did not find an appreciable difference in free cholesterol levels between tumor and healthy tissues, but there was a marked prevalence of LDs and CE levels in the GBM tumor tissues but not in the healthy tissue (Figure 1A, middle and bottom panels). We further analyzed 15 GBM tumors vs. unpaired healthy brain tissues from other individuals without cancer. As with the paired samples (Figure 1A), there was no significant difference in the free cholesterol levels between the unpaired tumor and healthy brain tissues (Figure S1A), while CEs and LDs were only detected in the GBM tumor tissues (Figure S1A). We also examined a human primary GBM30 cell-derived orthotopic tumor model.28 The pattern for cholesterol and CE/LD distribution between tumor and healthy brain tissues was like that observed in the samples from patients with GBM (Figure S1B).

Figure 1. Cholesterol reduction induces autophagy to hydrolyze LD-bound CEs in GBM cells.

(A) Representative images of H&E (top panels) or BODIPY 493/503 (green)/DAPI (blue) staining (middle panels) of paired GBM tumor and healthy brain tissues from human patient autopsies. Free cholesterol and CE in paired GBM tumor tissues vs. healthy brain tissues from patient autopsies (n = 11) were determined by cholesterol measuring kit (mean ± SD) (bottom panels). Statistical significance was analyzed by an unpaired Student’s t test. N.S, not significant. Scale bars, 10 μm in fluorescence images and 50 μm in H&E images.

(B and C) Representative transmission electron microscopy (TEM) images of tumor tissues from GBM patient biopsies. Green arrows indicate the double-membrane vesicle that engulfs LDs (B); red arrow shows that LD is entrapped in the lysosome (LY) (C). Scale bars, 500 nm.

(D) Representative confocal images of BODIPY 493/503 (green) staining in live U251 cells cultured in 5% FBS or 5% LPDS media for 0 or 24 h (top panels). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). LDs were quantified by ImageJ software from 30 cells (mean ± SD), and CEs were determined by a cholesterol/CE measuring kit (mean ± SD) (bottom panels). Statistical significance was analyzed by an unpaired Student’s t test.

(E) Representative confocal images of BODIPY 493/503 (green) staining in live U251 cells with shATG5 vs. shRNA control cells cultured in 5% FBS or 5% LPDS for 24 h (left panels). LDs and CE were determined as above.

(F and G) Representative confocal images of co-staining of BODIPY 493/503 (green)/LC3 (red) (F) and BODIPY 493/503 (green)/LysoTracker (red, staining the LYs) (G) in U251 cells cultured in 5% FBS or 5% LPDS media in the absence or presence of CQ (5 μM) for 4 h. The co-localization (yellow) of BODIPY-stained LDs with LC3-stained puncta (F) or lysotracker-stained LYs (G) was quantified by ImageJ software from 30 cells (mean ± SD).

(H) Representative confocal images of BODIPY 493/503 (green) staining in live U251 cells cultured in 5% LPDS media in the absence or presence of CQ (5 μM) for 0 and 24 h (top panels).

Statistical significance for (E)–(H) was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. Scale bar, 10 μm for (D)–(H).

Please also see Figures S1 and S2 and Videos S1 and S2.

We next used transmission electron microscopy (TEM) to closely examine LDs in human GBM tumor tissues. Intriguingly, in addition to the prevalence of LDs in the cytosol of tumor cells, we observed that the LDs were enclosed by double-membrane vesicles, a feature of autophagosomes (Figures 1B and S1C, green arrow). We also observed LDs in the lysosomes (Figures 1C and S1D, red arrow). We co-stained LDs with the autophagic marker LC3 and the lysosomal-associated membrane protein 1 (LAMP1) by immunostaining, respectively. Consistent with the TEM results, confocal fluorescence imaging showed that LDs (stained with BODIPY 493/503) were co-stained with LC3-formed puncta (Figure S1E) and LAMP1-stained lysosomes (Figure S1F), suggesting the presence of lipophagy in these cells.

Cholesterol depletion induces autophagy to hydrolyze LD-bound CEs in GBM cells

We next explored the conditions that trigger lipophagy in GBM cells. We first examined the effects on the LDs when extracellular cholesterol levels were depleted by culturing GBM cells with either medium containing cholesterol-deficient, lipoprotein-deficient serum (LPDS)20 or with medium that contains healthy fetal bovine serum (FBS), which contains abundant cholesterol carried by lipoproteins. By confocal imaging, we found that LDs were dramatically diminished by 24 h in the LPDS-containing medium but that LDs remained prevalent in the control cells cultured with FBS-containing medium (Figures 1D and S1G). The CE levels were also significantly lower in the GBM cells cultured in LPDS medium than control cells with FBS culturing (Figure 1D, bottom panel). Adding cholesterol (5 μg/mL) to the LPDS medium completely prevented the loss of LDs (Figure S1G).

We used a GFP-LC3 reporter to examine autophagy. We found that LPDS culturing (24 h) markedly enhanced GFP-LC3 puncta formation in GBM cells (Figure S2A). We then examined whether cholesterol depletion increased autophagic flux as determined by an mRFP-GFP-LC3 reporter.35 Fluorescence imaging clearly showed that LPDS culturing significantly enhanced both mRFP-GFP (yellow, 15.57% ± 3.07% puncta/cell) and mRFP (red, 65.47% ± 9.60% puncta/cell) signals compared with FBS culturing (3.13% ± 1.85% [yellow puncta/cell] and 13.10% ± 3.72% [red puncta/cell]) (Figure S2B).

Next, we found that ATG5 knockdown by short hairpin RNA (shRNA) effectively blocked LD and CE hydrolysis in GBM cells cultured with LPDS serum (24 h) (Figures 1E and S2D). Western blotting showed that LPDS culturing resulted in greater lipidation of LC3A/B35,36 (Figure S2C, bottom band). The lipidated form of LC3A/B was markedly lower upon ATG5 knockdown (Figure S2C).

By fluorescence imaging, we further found that LPDS culturing for 4 h induced the co-localization of LDs (green) with LC3 (red), whereas FBS culturing did not (Figure 1F). The co-localization was more clearly observed when lysosomal activity was inhibited by chloroquine (CQ) (Figure 1F, yellow color). By examination of time-lapse images (Figures 1G and S2E) and live-cell movies (Videos S1 and S2), we found that LDs (green) clearly mobilized into LysoTracker-stained lysosomes (red), with their co-localization (yellow) occurring after 4 h of LPDS culturing. The co-localization was further confirmed by immunostaining of LAMP1 and co-staining LDs with BODIPY 493/503, and this co-localization was further enhanced by CQ (Figure S2F). CQ treatment blocked the hydrolysis of LDs and CEs, leading to their accumulation after LPDS culturing for 24 h (Figures 1H and S2G). Further, western blotting showed that LPDS culturing resulted in greater levels of LC3 lipidation, and this effect was markedly enhanced upon CQ treatment (Figure S2H). Moreover, in a GBM xenograft model, tumor tissues with autophagy blockade by ATG5 knockdown contained more LDs, and had a smaller tumor volume, compared with control tumors (Figures S2I-S2K).

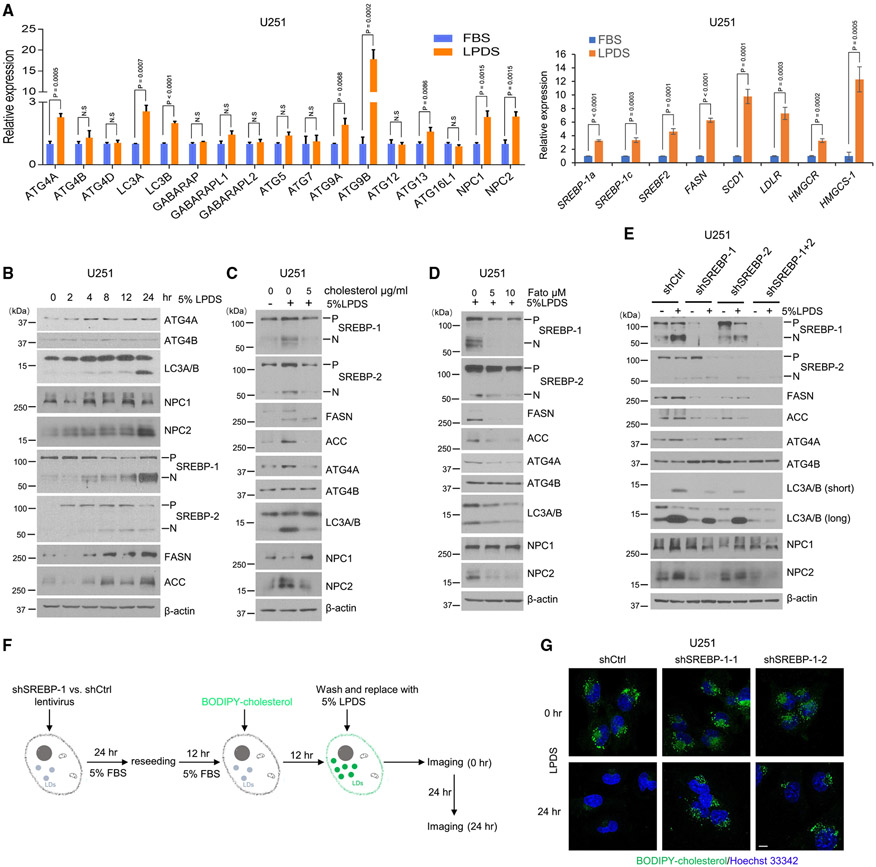

Cholesterol depletion activates SREBP-1 to induce lipophagy for CE hydrolysis

By quantitative real-time PCR analysis, we found that LPDS culturing was associated with significantly greater expression of multiple autophagic genes, including ATG4A, ATG9B, LC3A, LC3B, and ATG13, as well as the lysosome genes NPC1 and NPC2, along with greater expression of lipogenic genes, including SREBP-1a, -1c, and -2, FASN, SCD1, LDLR, HMGCR, and HMGCS1, compared with culturing with FBS-containing medium (Figure 2A). Western blotting validated that LPDS culturing was associated with greater protein levels of ATG4A, LC3A/B (lipidation form, bottom band), and NPC2, but not ATG4B, in a time-dependent manner, along with higher levels of N-terminal SREBP-1 and −2 fragments and the lipogenic enzymes fatty acid synthase (FASN) and acetyl-CoA carboxylase (ACC) (Figure 2B), which reflect the activation of SREBP transcriptional function.11,28,37

Figure 2. Cholesterol depletion activates SREBP-1 to induce lipophagy for CE hydrolysis.

(A) Real-time PCR analysis of mRNA expression (mean ± SD) of autophagy-related genes (left panel) and lipid-related genes (right panel) in U251 cells cultured in 5% FBS or 5% LPDS for 24 h. Statistical significance was analyzed by an unpaired Student’s t test. N.S, not significant.

(B) A representative western blot of U251 cells cultured in 5% LPDS at indicated time course.

(C) A representative western blot of U251 cells cultured in 5% LPDS vs. control 5% FBS labeled by minus symbol (−) in the absence or presence of supplemental cholesterol (5 μg/mL) for 40 h.

(D) A representative western blot of U251 cells cultured in 5% LPDS in the absence or presence of SREBP inhibitor fatostatin for 40 h.

(E) A representative western blot of U251 cells with shRNA silencing of SREBP-1 and −2 compared with shRNA control cells cultured in 5% FBS (−) or 5% LPDS (+) for 40 h. P, precursor; N, N-terminal active form of SREBPs.

(F and G) Schematic diagram illustrating the paradigm (F) to visualize the dynamic changes of BODIPY-cholesterol-labeled LDs in LPDS culturing (F). Representative confocal imaging of BODIPY-cholesterol-labeled LDs (green) in U251 cells with shSREBP-1 vs. shRNA control cells cultured in 5% LPDS for 0 and 24 h (G). Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm.

Please also see Figures S2 and S3.

By western blotting, we found that addition of cholesterol completely suppressed LPDS-induced ATG4A, LC3A/B (lipidation, bottom band), and NPC2 protein levels, without an effect on ATG4B expression, and this was accompanied by the suppression of SREBP-1 and −2 cleavage and downregulation of the lipogenic enzymes FASN and ACC (Figure 2C). We further used the SREBP inhibitor fatostatin (Fato) to treat GBM cells. By western blotting, we found that along with a striking suppression of SREBP-1 activation, ATG4A, LC3A/B, and NPC2 levels were lower compared with untreated controls (Figures 2D and S3A). Consistent with these results, genetic knockdown of SREBP-1 via lentivirus-mediated shRNA resulted in lower ATG4A, LC3A/B, and NPC2 protein levels, particularly under the LPDS culturing condition, compared with control cells (Figure 2E). In contrast, knockdown of SREBP-2 only resulted in slightly lower ATG4A, LC3A/B, and NPC2 levels in the LPDS condition, accompanied by a slight reduction of the active N-terminal cleavage band of SREBP-1 (N) but not the full length of precursor SREBP-1 (P), compared with shControl (shCtrl) cells in the same condition. In contrast, knockdown of both SREBP-1 and −2 showed the strongest effect on autophagic proteins (Figure 2E). These data suggest that SREBP-1 plays a major role in the regulation of autophagic and lysosome gene expression in GBM cells.

Next, we used BODIPY-labeled cholesterol to form fluorescent-labeled, LD-associated CE (Figure S3B).10,38 We confirmed it by co-staining with TIP47, a specific LD membrane protein.28 Fluorescence imaging showed that TIP47 bound to all BODIPY-cholesterol-formed droplets (Figure S3C). We then tracked their hydrolysis after culturing GBM cells in LPDS media with or without SREBP-1 knockdown via shRNA (Figures 2F and 2G). We found that BODIPY-cholesterol-labeled LDs remained largely retained in SREBP-1 knockdown cells, while LDs were markedly diminished in control cells transfected with scramble shRNA (Figure 2G). Moreover, the co-localization (yellow) between BODIPY-cholesterol-formed LDs (green) and LC3-positive puncta (red) were dramatically lower in ATG5 and SREBP-1 knockdown cells compared with control cells (Figure S3D).

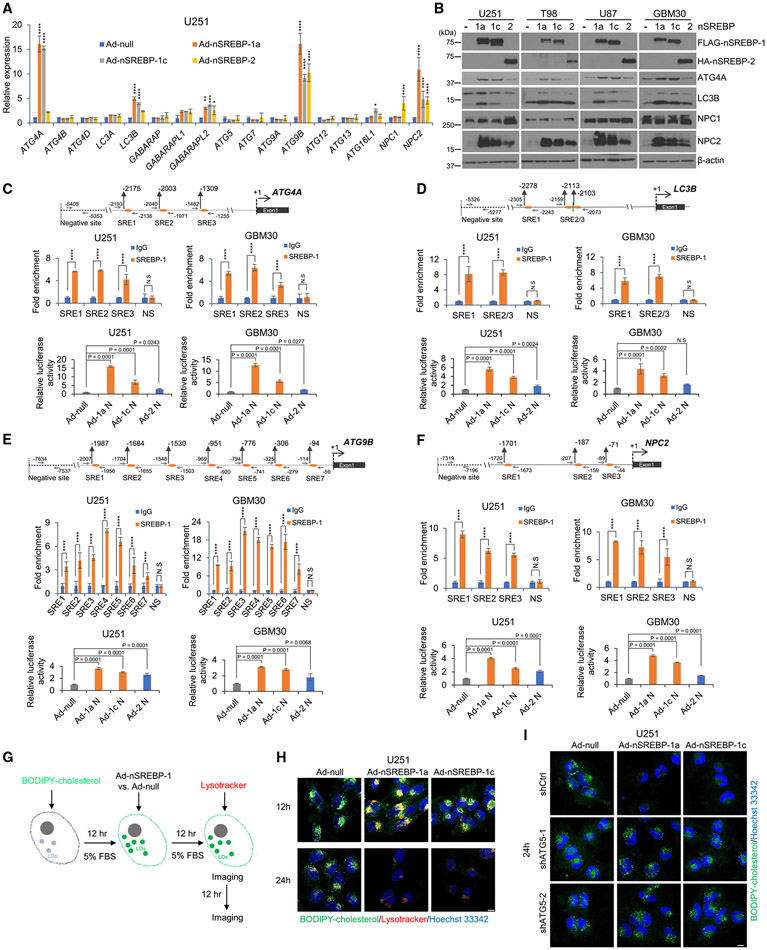

SREBP-1 transcriptionally activates autophagic and lysosome gene expression to promote autophagy-mediated CE hydrolysis

We next examined whether SREBP-1 acts via direct transcriptional regulation to promote autophagic gene expression. To test this possibility, we used an adenovirus vector to express active N-terminal SREBP-1a, −1c, or −2 isoforms in GBM cells cultured with FBS-containing medium (Figure S4A).39 By quantitative real-time PCR analysis, we found that active N-terminal SREBP-1a is the strongest isoform to stimulate ATG4A, ATG9B, LC3B, and NPC2 gene expression, and SREBP-2 showed less activation on these gene expressions (Figure 3A). Consistent with these gene expression results, ATG4A, LC3B, and NPC2 protein levels were strongly elevated by expression of the N-terminal SREBP-1 isoforms, while the SREBP-2 isoform only showed a slight effect on the expression of these proteins (Figure 3B).

Figure 3. SREBP-1 transcriptionally activates autophagic gene expression to promote autophagy-mediated CE hydrolysis.

(A) Real-time PCR analysis of mRNA expression (mean ± SD) of autophagy-related genes in U251 cells with overexpression of the active N-terminal SREBP-1a (Ad-nSREBP-1a), −1c (Ad-nSREBP-1c), or −2 (Ad-nSREBP-2) or Ad-null via adenovirus-mediated vector cultured in 5% FBS medium for 48 h. Statistical significance was analyzed by two-way ANOVA. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001.

(B) Representative western blots of U251, T98, U87, and GBM30 cells with overexpression of active N-terminal SREBP-1a, −1c, and −2 via adenovirus-mediated vector cultured in 5% FBS for 48 h.

(C–F) Top panels (scheme) show the putative SREBP-1-binding sites (SREs) and negative binding site (NS) on ATG4A (C), ATG9B (D), LC3B (E), and NPC2 (F) gene promoters. Middle panels show ChIP-PCR analysis of SREBP-1 binding to SREs and NS motifs located in respective gene promoters in U251 or primary GBM30 cells. Statistical significance was analyzed by two-way ANOVA. ****p < 0.0001. N.S., not significant. Bottom panels show promoter reporter luciferase (luc) activity for respective gene promoters containing SREs shown in the diagrams (top panels) cloned in the pGL3-luc basic vector that were transfected into U251 or primary GBM30 cells together with Renilla and infected with adenoviruses expressing N-terminal SREBP-1a (Ad-1a N), −1c (Ad-1c N), or −2 (Ad-2 N) or control (Ad-null) virus for 24 h (mean ± SD). Statistical significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA. N.S., not significant.

(G–I) Illustration of the paradigm (G) to visualize the dynamic changes of BODIPY-cholesterol-formed LDs in U251 (H), U251-shCtrl, or shATG5 stable cells (I) with overexpression of N-terminal SREBP-1a (Ad-nSREBP-1a) or −1c (Ad-nSREBP-1c) or Ad-null via adenovirus-mediated vector cultured in 5% FBS for indicated time. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Scale bars, 10 μm.

We then analyzed ATG4A, LC3B, ATG9B, and NPC2 gene promoters by using the online JASPAR resource40 and found multiple putative SREBP-1 transcriptional binding sites (i.e., sterol regulatory elements [SREs]) in these promoters (Figures 3C-3F, top panels). We conducted chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assays by using anti-SREBP-1 antibody, followed by qPCR analysis to validate SREBP-1 binding on the putative SREs. We found that SREBP-1 bound to the predicted SRE sites located in the promoters of all these genes (Figures 3C-3F, middle panels). We further examined the transcriptional activity of SREBP-1 in these gene promoters by using a pGL3-luciferase (pGL3-luc) reporter assay. We cloned these gene promoters into a pGL3-luc vector (pGL3-ATG4A-luc, -LC3B-luc, -ATG9B-luc, and -NPC2-luc) containing SREs. We found that SREBP-1a had the strongest effect on these gene promoters, while SREBP-1c had modest effects, compared with control cells transfected with pcDNA3.1 vector (Ad-null), and the promoter activity was minimally stimulated upon SREBP-2 expression (Figures 3C-3F, bottom panels).

We further examined whether expression of N-terminal SREBP-1 isoforms promoted BODIPY-cholesterol-labeled, LD-bound CE hydrolysis (Figure 3G). By fluorescent imaging, we found that both N-terminal SREBP-1a and −1c isoform expressions promoted a marked co-localization of BODIPY-cholesterol-labeled LDs with the LysoTracker-stained lysosomes in GBM cells at 12 h of culturing, but they resulted in the almost complete diminishment of the LDs after 24 h of expression (Figures 3G and 3H). Consistently, by using a U251-RFP-LC3 stable expression cell line, time-lapse imaging (Figure S4B) and Videos S3 and S4 showed that N-terminal SREBP-1a strongly stimulated the co-localization of BODIPY-cholesterol-formed LDs with RFP-LC3-formed puncta. In contrast, ATG5 knockdown markedly blocked SREBP-1 activation-mediated hydrolysis of LD-bound CEs in the FBS cultures (Figure 3I).

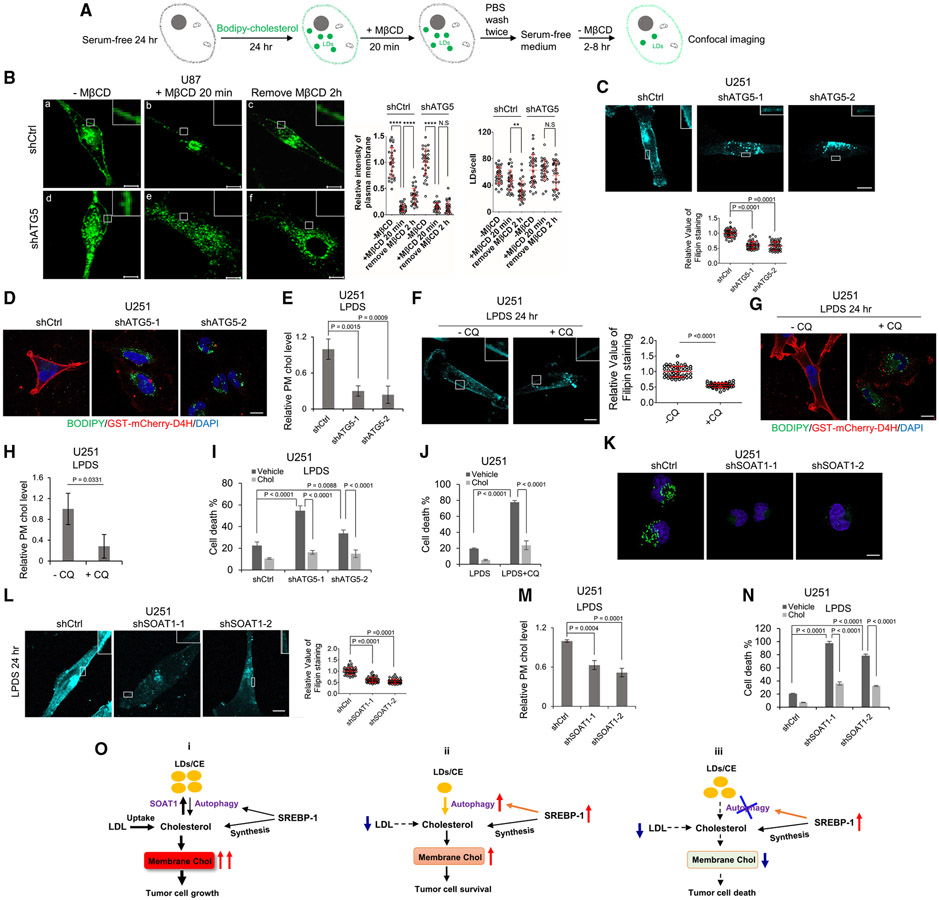

Free cholesterol liberated from CE hydrolysis traffics to the plasma membrane to maintain cholesterol homeostasis and GBM survival

We next used BODIPY-labeled cholesterol to form LD-bound CEs (Figures 4A and S5A) and then determined whether the released labeled cholesterol trafficked to the plasma membrane after autophagy-mediated hydrolysis. We starved U87 cells that were either knocked down for ATG5 via shRNA or infected with scramble shRNA for 24 h in FBS-free medium and then cultured the cells with BODIPY-cholesterol for another 24 h. The plasma membranes from both shCtrl and shATG5 cells were labeled by BODIPY-cholesterol (Figures 4B-a, 4B-d, S5B-a, and S5B-f, please see amplified boxes), along with many LD-bound CEs in both cells (Figures 4B and S5A). The cells were then placed in fresh serum-free medium without BODIPY-cholesterol and treated with methyl-beta-cyclodextrin (MβCD) (4 mM, 20 min) (please see Figure 4A), a cyclic heptasaccharide that directly extracts cholesterol from the plasma membrane.41 By confocal imaging, we found that BODIPY-cholesterol in the plasma membrane of both cells (shCtrl and shATG5 cells) was quickly removed and reduced to 13.5% ± 7.1% and 14.6% ± 7.3% of the BODIPY-cholesterol level in the plasma membrane prior to MβCD treatment, respectively (Figures 4B-b, 4B-e, S5B-b, and S5B-g). MβCD was then removed, the cells were cultured in fresh serum-free media for 2 h, and we found that fluorescence from BODIPY-cholesterol was restored to 35.2% ± 15.1% in the plasma membrane of shCtrl cells, concurrent with a marked reduction of BODIPY-cholesterol-labeled LDs (Figures 4B-c, S5B-c, S5B-d, and S5B-e). In contrast, in ATG5 knockdown cells, BODIPY-cholesterol in the plasma membrane was not restored, and BODIPY-cholesterol-labeled LDs had no significant change (Figures 4B-f, S5B-h, S5B-i, and S5B-j).

Figure 4. Free cholesterol liberated from CE hydrolysis traffics to the plasma membrane to maintain cholesterol homeostasis and GBM survival.

(A and B) Schematic diagram illustrating the paradigm (A) to visualize BODIPY-cholesterol-labeled plasma membrane and LDs (green) in U87 cells with shRNA silencing of ATG5 compared with shRNA control cells (B) cultured with BODIPY-cholesterol (20 μg/mL) in serum-free media for 24 h (a and d); these cells were then replaced with fresh serum-free media and treated with MβCD (4 mM) for 20 min (b and e), followed by replacing with fresh serum-free media for 2 h (c and f). Scale bars, 10 μm. BODIPY-cholesterol level in the plasma membrane in each condition was quantified by ImageJ software from over 30 cells and normalized with shCtrl or shATG5 cells prior to MβCD treatment (mean ± SD) (right panel). The number of BODIPY-cholesterol-formed LDs was quantified by ImageJ software from over 30 cells (mean ± SD) (right panel). Scale bars, 10 μm.

(C) The plasma membrane cholesterol in U251-shATG5 stable cells cultured in 5% LPDS media for 24 h was measured by staining with filipin and observed by fluorescent microscopy (top panel). The intensity of filipin staining on plasma membrane from 50 cells was quantified by ImageJ software (mean ± SD, bottom panel). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(D) Labeling of plasma membrane cholesterol by GST-mCherry-D4H probe for 2 h in 37°C (red) in U251- shCtrl and -shATG5 cells after culturing in 5% LPDS for 24 h. Lipid droplets were co-stained with BODIPY 493/503 (5 μM) (green), and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(E) Biochemical measurement of plasma membrane cholesterol level in U251-shCtrl and -shATG5 cells cultured in 5% LPDS for 24 h.

(F) The plasma membrane cholesterol in U251 cells cultured in 5% LPDS media in the absence or presence of CQ (5 μM) for 24 h was measured by staining with filipin and observed by fluorescent microscopy (left panel). The intensity of filipin staining on plasma membrane from 50 cells was quantified by ImageJ software (mean ± SD, right panel), and statistical significance was analyzed by an unpaired Student’s t test. Scale bar, 10 μm.

(G) Labeling of plasma membrane cholesterol by GST-mCherry-D4H (red) in U251 cells after culturing in 5% LPDS in the absence or presence of CQ (5 μM) for 24 h. Lipid droplets were co-stained with BODIPY 493/503 (5 μM) (green), and nuclei were stained with DAPI (blue).

(H) Biochemical measurement of plasma membrane cholesterol level in U251 cells cultured in 5% LPDS media in the absence or presence of CQ (5 μM) for 24 h. Statistical significance was analyzed by an unpaired Student’s t test.

(I) Cell death percentile of U251 cells with shRNA silencing of ATG5 compared with shCtrl cultured in 5% LPDS in the absence or presence of supplemental cholesterol (5 μg/mL) for 3 days. Statistical significance was analyzed by two-way ANOVA.

(J) Cell death percentile of U251 cultured in 5% LPDS in the absence or presence of CQ (5 μM) with/without supplemental cholesterol (5 μg/mL) for 3 days.

(K) Representative confocal images of BODIPY 493/503 (green) staining in live U251 cells with shRNA silencing of SOAT1 compared with shCtrl for 24 h and then split in 35 mm glass-bottom dish cultured in 5% FBS media for 24 h. Nuclei were stained with Hoechst 33342 (blue). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(L) The plasma membrane cholesterol in U251 with shRNA silencing of SOAT1 compared with shCtrl cells in 5% FBS for 48 h and then replaced with fresh 5% LPDS medium for 24 h before staining with filipin and observed by fluorescent microscopy (left panel). The intensity of filipin staining on plasma membrane from 50 cells was quantified by ImageJ software (mean ± SD, right panel). Scale bar, 10 μm.

(M) Biochemical measurement of plasma membrane cholesterol level in U251-shSOAT1 vs. control cells (shCtrl) cultured in 5% LPDS for 24 hr.

(N) Cell death percentile of U251 cells with shRNA silencing of SOAT1 compared with shCtrl cultured in 5% LPDS in the absence or presence of supplemental cholesterol (5 μg/mL) for 3 days.

(O) Schematic model illustrating the role of LD-bound CEs in the maintenance of cholesterol homeostasis and GBM cell growth through autophagy-mediated hydrolysis. (i) When the cellular cholesterol level is high, it is converted to CE and stored in LDs. In this condition, the autophagy rate is low and LDs are maintained at high levels in GBM cells. (ii) Under a low LDL/cholesterol microenvironment, SREBP-1 is activated to promote cholesterol biosynthesis, but autophagy is also induced to hydrolyze LD-bound CEs, releasing the stored cholesterol to contribute to the maintenance of membrane cholesterol homeostasis and tumor survival. (iii) Under a low LDL/cholesterol microenvironment, inhibition of autophagy blocks the hydrolysis of LD-bound CEs, resulting in a marked reduction of membrane cholesterol levels, leading to GBM cell death.

Statistical significance was analyzed by one-way ANOVA for (A)–(E) and (J)–(N).

Please also see Figures S5 and S6.

Filipin staining, a fluorescent compound that specifically binds to cholesterol,42 showed that the plasma membrane cholesterol in ATG5 knockdown cells was significantly lower compared with scrambled shRNA transfection in LPDS cultures (Figure 4C). Consistently, by using GST-purified mCherry-labeled cholesterol-binding protein probe D4H(GST-mCherry-D4H),43 we found that mCherry-D4H mainly bound to the plasma membrane in control cells (Figure 4D). In contrast, mCherry-D4H failed to bind to the plasma membrane in ATG5 knockdown cells, where LDs accumulated due to the blockade of LD hydrolysis by autophagy inhibition (Figure 4D), demonstrating that cholesterol levels in the plasma membrane were dramatically reduced upon the inhibition of lipophagy. This result was further confirmed by using a biochemical assay to measure plasma membrane cholesterol levels according to a previous study (Figure S5C),44 which showed that cholesterol levels in the plasma membrane of ATG5 knockdown cells were significantly reduced in LPDS cultures (Figure 4E). Furthermore, filipin staining, mCherry-D4H binding, and biochemical measurements all showed that CQ treatment inhibited autophagy-mediated hydrolysis of LD-bound CEs, and this was associated with significantly reduced plasma membrane cholesterol levels in LPDS cultures compared with control cells without CQ treatment (Figures 4F-4H).

Furthermore, inhibition of LD-bound CE hydrolysis in LDPS culturing conditions, either via ATG5 knockdown or CQ treatment for 3 days, markedly enhanced GBM cell death compared with control cells transfected with scrambled shRNA or without CQ treatment, while this effect was completely abolished by the addition of cholesterol (5 μg/mL) to the cell media (Figures 4I, 4J, S5D, and S5E).

We next depleted GBM cells of LD-bound CEs via knockdown of sterol O-acyltransferase 1 (SOAT1) (Figures 4K, S6A, and S6B), which controls CE synthesis and LD formation in GBM cells as demonstrated by our previous study.28,45 Both by fluorescence imaging of filipin staining (Figures 4L and S6C) and by biochemical assessment (Figure 4M), we found that plasma membrane cholesterol levels were significantly lower in LD-bound, CE-depleted cells (shSOAT1) than LD-bound, CE-replete cells (shCtrl). GBM cells lacking LD-bound CEs (shSOAT1 cells) were more sensitive to cholesterol restriction, which showed dramatically increased cell death in LPDS culture than shCtrl cells containing LD-bound CEs (Figures 4N, S6D, and S6E), and these effects were significantly reduced by the addition of cholesterol (5 μg/mL) to the media (Figures 4N and S6E).

DISCUSSION

In this study, we identified a pro-survival mechanism whereby LD-bound CEs serve as an intracellular cholesterol reservoir that maintains membrane cholesterol levels in GBM cells via autophagy-mediated hydrolysis when extracellular cholesterol levels are low (Figure 4O). Our autophagy inhibition experiments help tease apart the contribution of SREBP-induced lipophagy from SREBP-induced cholesterol synthesis to the maintenance of membrane cholesterol levels. Importantly, that approach revealed that de novo synthesis is not sufficient to maintain cholesterol homeostasis when extracellular cholesterol is depleted, but rather that lipophagy plays a critical role in this process. Our data suggest that targeting this lipophagic pathway might be promising for GBM therapy (Figure 4O).

Autophagy is an evolutionarily conserved biologic process that recycles nutrients under starvation or stressful conditions.46,47 By using a ChIP sequencing (ChIP-seq) assay, a previous study reported that SREBP-2 in mouse hepatocytes regulates the expression of the autophagic genes ATG4B, ATG4D, and LC3B,48 while they found that SREBP-1 is not at all involved in the regulation of autophagic gene expression.48,49 In addition, they reported that there is only an 11% overlap in genes regulated by SREBP-1 and SREBP-2, which are mainly in the lipid metabolism and apoptosis pathways, while there is an 89% difference in the gene sets regulated by these two isoforms.48,49 Moreover, a recent study further excluded SREBP-1 as a stimulator of autophagy, rather showing that SREBP-1c inhibits autophagy by blocking ULK1 (unc-51 like autophagy activating kinase 1) sulfhydration-mediated autophagic flux in the liver of high-fat diet-fed mice.50 In contrast, our current study demonstrated an opposite function for SREBP-1 compared with these previous reports. We revealed that SREBP-1 directly activates the transcriptional activity of the autophagic genes ATG4A, ATG9B, and LC3B, as well as the critical lysosome cholesterol transporter NPC2, in GBM cells, while SREBP-2 only plays a minor role in this process. Our data demonstrate a marked difference between mouse hepatocytes and human cancer cells with respect to the regulation of lipophagy between SREBP-1 and SREBP-2. Moreover, SREBP-1 activation occurs in a variety of cancer cells, including GBM, breast, pancreatic, colorectal, ovarian, and liver cancer cells.51-57 It is possible that SREBP-1-regulated autophagic hydrolysis of LD-bound CEs is a common mechanism used by various cancers to maintain their cholesterol homeostasis.

Limitation of the study

Our study reveals the role of LD-bound CE hydrolysis in maintaining plasma membrane cholesterol homeostasis, but it also brings up further interesting questions that will need to be addressed, such as general autophagy factors seeming to regulate selective autophagy and that how this happens is unclear, and how free cholesterol is transported to the plasma membrane after autophagic release from the lysosomes, such as by vesicles or sterol transfer proteins. In addition, it will also be important to determine whether LD-bound, CE-derived free cholesterol traffics to the membranes of the endoplasmic reticulum, the Golgi, and the mitochondria to maintain their functions. Furthermore, there is an intriguing question that should be explored involving why SREBP-1 activates autophagy in human brain tumor cells while it inhibits autophagy in the liver of high-fat diet-fed mice, as reported by others.50 Finally, further in vivo testing of whether targeting this system indeed has a beneficial effect on tumor burden is required.

STAR★METHODS

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Further information and requests for resources and reagents should be directed and will be fulfilled by the Lead Contact, Deliang Guo (deliang.guo@osumc.edu).

Materials availability

All plasmids and cell lines generated in this study are available from the lead contact with a completed materials transfer agreement.

Data and code availability

All the data reported in this paper are available from the lead contact upon request. This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

Tissues from human participant

All patient samples used in this study are de-identified. Biopsies from individuals were obtained from the Department of Pathology at the Ohio State University Medical Center after surgery and were fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 24 h. One-half of the biopsy tissue was embedded in paraffin and the other half was incubated with 30% sucrose for 24 h and embedded in Tissue-Plus O.C.T. (optimal cutting temperature) compound (Fisher Scientific). Cryosections derived from the latter were stained by BODIPY 493/503 (Invitrogen). Autopsy tissues from individuals were obtained from the Department of Pathology at the UCLA Medical Center and were frozen at −80°C immediately after excision. The study on tissues from individuals was approved by the Ohio State University Institutional Human Care and Use Committee.

Xenograft mouse model

Female athymic nude mice (6–8 weeks of age) obtained from the OSU Target Validation Shared Resource (TVSR) and acclimatized for 1–2 weeks were used to generate xenograft models. GBM30 cells (1×105) were implanted into mouse brain. Mice were sacrificed 18 days after implantation and the brain was removed for lipid droplet staining as described for GBM patient tissues or used for CE analysis. For subcutaneous xenograft model, U87/EGFRvIII/shcontrol and U87/EGFRvIII/shATG5 cells (1×106) were implanted into mouse flank. Mice were sacrificed when tumors grew to the limitation on day 22, and tumors were collected and embedded in OCT. Mice were housed 5 per cage in a conventional barrier facility with free access to water and food on a 12 h light/12 h dark cycle at 22°C and a relative humidity of 25%. Mice health status was monitored by following the protocols. All animal procedures were approved by the Subcommittee on Research Animal Care at the Ohio State University Medical Center.

Cell lines

Human GBM cell lines, U87, U87/EGFRvIII, T98 and U251, were cultured in Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s media (DMEM) supplemented with 5% FBS (Cytiva HyClone) and 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37°C. Human lung cancer cell lines, H520 and HCC827, were cultured in RPMI-1640 media (Corning) supplemented with 5% FBS (Cytiva HyClone) and 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2 and 95% air at 37°C. U87/GFP-LC3, U251/mRFP-GFP-LC3 and U251/RFP-LC3 cells were generated by transfection of EGFP-LC3 (Addgene),58 ptfLC3 (mRFP-GFP-LC3) plasmid (Addgene)59 or pmRFP-LC3 plasmid (Addgene)59 into U87 or U251 cells followed by G418 (200 μg/mL) selection for 14 days to obtain stable clones.59 GBM30 and GBM83, primary GBM patient-derived cells, have been previously described28 and were cultured in DMEM/F12 50/50 medium (Corning) supplemented with B27 (1x) (Gibco), Heparin (2 μg/mL) (Sigma), EGF (20 ng/mL) (Sigma) and FGF (20 ng/mL) (R&D Systems) and 2 mM L-glutamine (Gibco) in a humidified atmosphere of 5% CO2, 95% air at 37°C. When GBM30 cells were used for cholesterol depletion experiments, the cells were placed in 5% FBS/DMEM and 5% LPDS/DMEM culture as U251 cells. The cell lines were tested for mycoplasma contamination routinely.

METHOD DETAILS

Western blotting

Cultured cells were lysed using RIPA buffer (Fisher), containing phosphatase inhibitors and a cocktail of protease inhibitors (Sigma). Equal amounts of protein extracts were resolved by 12% SDS-PAGE, and electro-transferred onto a nitrocellulose membrane (Bio-Rad). After blocking the membranes for 1 h in a Tris-buffered saline containing 0.1% Tween 20 and 5% nonfat milk, they were probed with various primary antibodies, followed by appropriate secondary antibodies conjugated with horseradish peroxidase. The immunoreactivity was revealed by use of an ECL kit (Cytiva Amersham). The dilutions of each antibody were used as follows: SREBP-1 1:2,000, SREBP-2 1:500, FASN 1:3,000, ACC 1:3,000, ATG4A 1:30,000, ATG4B 1:1,000, LC3A/B 1:2,000, LC3B 1:3,000, HA 1:3,000, FLAG 1:3,000, NPC1 1:30,000, NPC2 1:2,000, β-actin 1:50,000.

Preparation of cell membrane fractions

Cells were washed once with PBS, scraped into 1mL PBS, and centrifuged at 1000 × g for 5 min at 4°C. Cells were then suspended in ice-cold buffer containing 10 mM HEPES-KOH (pH 7.6), 10 mM KCl, 1.5 mM MgCl2, and 1 mM sodium EDTA, 1 mM sodium EGTA, 250 mM sucrose and a mixture of protease inhibitors (5 μg/mL pepstatin A, 10 μg/mL leupeptin, 0.5 mM PMSF, 1 mM DTT, and 25 μg/mL ALLN) for 30 min on ice. Extracts were then passed through a 22G x 1 1/2 needle 30 times and centrifuged at 890 x g at 4°C for 5 min to isolate the nuclei. Supernatant was used for the separation of membrane fractions.

The supernatant from the original 890x g spin was centrifuged at 20,000x g for 20 min at 4°C. For subsequent Western blot analysis (for SOAT1 protein), the pellet was dissolved in 0.1 mL of SDS lysis buffer (10mM Tris-HCl pH 6.8, 100mM NaCl, 1% (v/v) SDS, 1 mM sodium EDTA, and 1 mM sodium EGTA) and designated “membrane fraction”. The membrane fraction was incubated at 37°C for 30 min, and protein concentration was determined. 1 μL 100x bromophenol blue solution was added before the samples were subjected to SDS-PAGE.

Cell proliferation and viability

Cells (1-2 x 104) were seeded into 12-well plates, washed with PBS after 24 h, and incubated with fresh media containing 5% FBS or 5% LPDS. Cells were counted using a hemocytometer, while live and dead cells were assessed using Trypan blue exclusion assays (Gibco). Percentage of dead cells was calculated as the number of dead cells divided by the total cell number.

Lipid droplet staining and quantification

Lipid droplets were stained by incubating cells with 0.5 μM BODIPY 493/503 (Life Technologies) for 30 min, were visualized by confocal microscope (Carl Zeiss LSM510 Meta, LSM800 63x/1.4 NA oil) and 1 μm wide z-stacks were acquired. More than 30 cells in each group were analyzed and LD numbers quantified with ImageJ software (NIH) in a 3D stack as previous report.60

Immunofluorescence microscopy

Cells were cultured and treated on glass coverslip, washed with PBS twice and fixed with 4% paraformaldehyde for 10 min, followed by 5 min of permeabilization with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS. After incubation with the primary antibody overnight at 4°C, cells were incubated with fluorescence-labeled second antibody for 30 min at 37°C, then incubated with 0.5 μM BODIPY 493/503 for 30 min to stain the lipid droplets. Coverslips were mounted with antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen) and visualized with confocal microscopy.

Transmission electronic microscopy (TEM)

Fresh tumor tissues from GBM patients were fixed in 2.5% glutaraldehyde/0.1 M phosphate buffer (0.019 M monobasic sodium phosphate and 0.081 M dibasic sodium phosphate), pH 7.4 for 10 min, and then cut into pieces less than 1 mm3, followed by fixation by 2.5% glutaraldehyde/0.1M phosphate buffer overnight at 4°C. Tissues were then washed with 0.1M phosphate buffer for 3 × 5 min. After fixation in 1% osmium tetroxide/phosphate buffer for 1 h at room temperature, tissue pieces were stained with 2% uranyl acetate/10% ethanol for 1 h, followed by dehydration in 50%, 70%, 80%, 95% and 100% ethanol. The tissues were finally embedded in Eponate-12 resin. Ultra-thin sections (70 nm) were produced on a Leica EM UC6 ultramicrotome and stained with 2% uranyl acetate and Reynold’s lead citrate. TEM was performed on a FEI Tecnai G2 Spirit TEM at 80 kV. Images were captured using an AMT 2x2 digital camera. These experiments were performed at the OSU Microscopy Core Facility.

Cholesterol and cholesteryl esters measurement

Cells were washed with PBS twice and collected by scraping and centrifugation at 200 x g for 10 min. The cell pellets were resuspended in Isopropanol/1% Triton X-100 for 1 h at room temperature. After centrifugation at 12,000 rpm (Sorvall Legend Micro 17 centrifuge) for 10 min, the supernatants were transferred into glass tubes and dried under passing nitrogen gas. Cholesterol and cholesteryl esters (CE) measurements were performed following the instruction manual of the cholesterol assay kit (Invitrogen).

Biochemistry plasma membrane cholesterol measurement

The level of plasma membrane (PM) cholesterol was measured by following the previous publication.44 As shown in Figure S5C, 2 x 105 cells were seeded in 60 mm dish in DMEM medium containing 5% FBS. After 24 h, cells were washed with PBS, and then replaced with fresh medium containing 5% LPDS. After 24hr, cells were washed with cold-PBS for 3 times, and 3 times with cold assay buffer (310 mM sucrose, 1 mM MgSO4, 0.5 mM sodium phosphate [pH 7.4]), followed by incubated in the absence or presence of 1 U/ml cholesterol oxidase for 3 min at 25°C, the buffer was then removed and discarded. 2 mL of PBS were used to scape cells, and mixed with 4 mL of chloroform:methanol (2:1) to extract lipid. Finally, the dried lipid was dissolved in 200 μL of 1 x assay buffer from cholesterol measurement kit, and measure the cholesterol level following the instruction manual of the cholesterol assay kit (Invitrogen).

Construction of the plasmid pGEX-mCherry-D4H

The pmCherry-C1 vector with D4H expression cassette (pmCherry-D4H) was a kind gift from Dr. Gregory D. Fairn (University of Toronto, Canada). The DNA fragment of D4H was amplified from pmCherry-D4H using the primers of 5′-CCGCTCGAGCCAAGGGAAAAATAAACTTA-3’ (D4H forward primer) and 5′-CGCCAATTGTTAATTGTAAGTAATACT-3’ (D4H reverse primer). pGEX-KG-D4H*-mCherry (GST- D4H*-mCherry, Addgene, #134604) plasmid61 was digested by XhoI and MfeI restrictive endonucleases to remove the fragment of D4H*-mCherry. The PCR product of D4H was digested by XhoI and MfeI restrictive endonucleases and then inserted into the above plasmid backbone to generate the vector pGEX-KG-D4H. Then, the mCherry expression cassette was amplified from the pmCherry-D4H using the primers of 5′-CCGCTCGAGATGGTGAGCAAGGGCGAG-3’ (mCherry forward primer) and 5′-CCGCTCGAGATCTGAGTCCGGACTTGTAC-3’ (mCherry reverse primer). The product was digested by XhoI restrictive endonuclease and then introduced into the pGEX-KG-D4H vector at the XhoI site. The resulting plasmid candidates were verified by Sanger sequencing at OSU genomic shared resource core. The vector with the mCherry fragment incorporated in the correct orientation was selected as the final construct pGEX-KG-mCherry-D4H.

Purification of recombinant GST-mCherry-D4H

The purification of GST tagged mCherry-D4H followed the protocol published by Lim, C. Y et al.61 Briefly, pGEX-KG-mCherry-D4H plasmid was transfected in Escherichia coli strain BL21 cultured in Luria-Bertani (LB) broth medium (ampicillin 50 μg/mL) at 37°C until the OD600 reached around 0.6, and the GST-mCherry-D4H protein production was induced with 0.4 mM IPTG (Fisher) for 20 h at 18°C. Bacteria were collected by centrifugation and the pellets were lysed in lysis buffer (20 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.0, 0.1 M NaCl, 1 mM DTT) containing protease inhibitor cocktail tablet and incubated with 0.35 mg/mL lysozyme (Fisher) on ice for 30 min followed by sonication on ice using a Sonic Dismembrator (Fisher, # FB120). The lysate was treated with 0.5% Triton X-100 at 4°C for 15 min and centrifuged at 17,000 g at 4°C for 30 min. The supernatant was bound to GLUTATHIONE Sepharose 4B (Cytiva), and GST-mCherry-D4H proteins were eluted from beads with 25 mM L-glutathione solution in 50 mM Tris-Cl, pH 8.8 and 200 mM NaCl. The fractions of the eluate were pooled and filtered by Microcon-30kDa Centrifugal Filter Unit (Sigma) to remove glutathione and concentrate the protein in 50 mM Tris-Cl pH8.0, 0.5 mM DTT. The protein solution was then supplemented with 20% sucrose and stored in −80°C.

Labeling of plasma membrane cholesterol with GST-mCherry-D4H

GBM cells were cultured and treated on glass cover clip, washed with PBS twice, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were washed 3 times with PBS, and then stained with purified GST-mCherry-D4H (10 μg/mL) and BODIPY 493/503 (5 μM) for 2 h at 37°C. After washing 3 times with PBS, coverslips were mounted with antifade reagent with DAPI (Invitrogen) and visualized with confocal microscopy.

Real-time PCR

Total RNA was extracted from human cells using TRIzol reagent according to its protocol (Invitrogen). Total RNA (800 ng) was subjected to reverse transcription to cDNA using iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad) and amplified through a subsequent real-time PCR using PowerUp SYBR Green Master Mix (Applied Biosystems), and its values were normalized against the internal control gene 36B4 for each replicate.

The primers used are shown in Table S1.

Chromatin immunoprecipitations (ChIP)

ChIP were performed using SimpleChIP Plus Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit (Cell Signaling) by following the instruction. Briefly, cells in 15cm dish were fixed with formaldehyde at final concentration 1% to crosslink proteins to DNA, and then incubated with glycine. Remove media and wash cells two times with ice-cold 1 x PBS, and scape cells with ice-cold 1 x PBS containing Protease Inhibitor Cocktail following centrifuge at 2,000 x g for 5 min at 4°C. The pellet was used for nuclei preparation and chromatin digestion. Finally, 2 μg of SREBP-1 antibody or IgG (Sigma) were used for chromatin immunoprecipitation. PCR primers used for analysis of SREBP-1 binding motifs in ATG4A, ATG9B, LC3B and NPC2 are shown in Table S1.

Promoter luciferase assay

After PCR, the fragment of gene promoter of ATG4A (2175 bp) or LC3B (1631 bp) was cloned into pGL3-basic vector at KpnI/HindIII site; the fragment of gene promoter of ATG9B (2058 bp) or NPC2 (1803 bp) was cloned into pGL3-basic vector at NheI/XhoI (Promega, #E1751). Promoter construct DNA (100 ng) and renilla plasmid (20 ng) (Promega) were transfected into U251 by using X-tremeGENE HP DNA Transfection Reagent (Sigma) in a 12-well plate with 5% FBS full DMEM medium then infected with adenovirus expression null, N-terminal SREBP-1a, −1c or −2. GBM30 cells were seeded in Geltrex (Gibco) coated 12-well plate, and performed same procedure as done in U251. Luciferase activity was measured 24 h post-transfection by using firefly luciferase assay reagent (Promega) and renilla luciferase assay reagent (Promega) according to the kit instruction, and the signal was detected by Promega GloMax Plate Reader.

Primers used to clone gene promoters are shown in Table S1.

Lentivirus transduction

Mission pLKO.1-puro lentivirus vector containing ATG5 shRNA-1 (TRCN0000330394), ATG5 shRNA-2 (TRCN0000330392), SREBP-1 shRNA-1 (TRCN0000421299), SREBP-1 shRNA-2 (TRCN0000422088), SREBP-2 shRNA (TRCN00000431900), SOAT1 shRNA-1 (TRCN0000036440), SOAT1 shRNA-2 (TRCN0000234512) and the non-mammalian shRNA control (SHC002) were purchased from Sigma. The 293FT cells were transfected with the shRNA vector and packaging plasmids psPAX2 and the envelope plasmid pMD2.G using polyethylenimine (Polysciences). The supernatant was collected after 48 h and concentrated using the Lenti-X Concentrator (Clontech) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. The lentiviral transduction was performed according to Sigma’s MISSION protocol with polybrene (8 μg/mL; Sigma).

H&E staining

Paraffin tissue sections were deparaffinized in xylene and rehydrated in degraded ethanol. After washing with dH2O, slides were stained with hematoxylin and eosin solution in sequence followed by washing with distilled H2O. Slides were then dehydrated in degraded ethanol and immersed in xylene, followed by mounting in Permount mounting medium.

Filipin staining and quantification

GBM cells were cultured and treated on glass cover clip, washed with PBS twice, and fixed in 4% paraformaldehyde for 1 h at room temperature. Cells were washed 3 times with PBS, and then stained with filipin (50 μg/mL in PBS) for 1 h at room temperature. After washing 3 times with PBS, cells were visualized by Olympus FV1000 MPE Multiphoton Laser Scanning Confocal. For quantification, 50 cells from each group were photographed and 5 random regions along the plasma membrane were analyzed. The intensity for each region was determined by ImageJ and the average of 5 regions stands for filipin staining value for each cell.

BODIPY-cholesterol labeling

Five mg of BODIPY-cholesterol (Bchol) powder were dissolved in ethanol (1.74 mL) to generate a 5 mM stock solution, then transferred to a clean glass vial and the ethanol was evaporated by passing nitrogen gas to produce a thin film. Then, 5 mL of MβCD (dissolved in PBS, 17.4 mM) were added to make a BODIPY-cholesterol/MβCD complex (molar ratio of 1:10) at 1 mg/ml final concentration. BODIPY-cholesterol film was resuspended by vortexing and sonicated for 10 min, then shaken overnight at 37°C. This complex solution was centrifuged for 10 min at 21,000 × g to remove undissolved BODIPY-cholesterol, and then aliquoted and stored at 4°C under nitrogen gas. Plasma membrane binding of BODIPY-cholesterol was quantified by ImageJ, which was the same as filipin staining quantification. Quantification of LD formation by BODIPY-cholesterol was the same as with BODIPY 493/503 staining.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

All figures are representative of at least two biological replicates with similar results, unless stated otherwise. No animals or data points were excluded from the analyses in our study. Statistical analysis was performed with Excel or GraphPad Prism7. Cell proliferation, tumor volumes, and quantification of LDs were performed using the two-tailed Student’s t-test as well as by ANOVA, as appropriate. The data are reported as means ± SD. p value was indicated in the figure, or as *, p < 0.05; **, p < 0.01; ***, p < 0.001; ****, p < 0.0001; N.S, not significant.

Supplementary Material

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-FASN | Cell Signaling | Cat#3180; RRID:AB_2100796 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-ACC | Cell Signaling | Cat#3676; RRID:AB_2219397 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-HA tag | Cell Signaling | Cat#3724; RRID:AB_1549585 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-LC3A/B | Cell Signaling | Cat#4108 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-LC3B | Cell Signaling | Cat#3868; RRID:AB_2137707 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-ATG4A | Cell Signaling | Cat#7613; RRID:AB_10827645 |

| Rabbit polyclonal anti-ATG4B | Cell Signaling | Cat#5299; RRID:AB_10622184 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-ATG5 | Cell Signaling | Cat#8540; RRID:AB_10828728 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-SREBP-1 | BD Biosciences | Cat#557036; RRID:AB_396559 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-NPC1 | NOVUS Biologicals | Cat# NBP2-76798 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-NPC2 | Santa Cruz Biotechnology | Cat#sc-166321; RRID:AB_2236437 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-FLAG | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#F3165; RRID:AB_259529 |

| Mouse monoclonal anti-β-Actin, clone AC-15 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#A1978; RRID:AB_476692 |

| Rabbit monoclonal anti-SREBP-2, clone 22D5 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#MABS1988 |

| Normal Mouse IgG | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#NI03-100UG |

| Anti-mouse IgG, HRP-linked Antibody | Cell Signaling | Cat#7076; RRID:AB_330924 |

| Anti-rabbit IgG, HRP-linked Antibody | Cell Signaling | Cat#7074; RRID:AB_2099233 |

| Goat anti-Mouse IgG (H + L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 594 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A-11032; RRID:AB_2534091 |

| Goat anti-Rabbit IgG (H + L) Highly Cross-Adsorbed Secondary Antibody, Alexa Fluor™ 568 | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#A-11036; RRID:AB_10563566 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| Escherichia coli strain BL21 (DE3) | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat# FEREC0114 |

| Adeno-null | Ru et al.42 | N/A |

| Adeno-nSREBP-1a | Ru et al.42 | N/A |

| Adeno-nSREBP-1c | Ru et al.42 | N/A |

| Adeno-nSREBP-2 | Ru et al.42 | N/A |

| Biological samples | ||

| Human GBM patient samples | Department of Pathology at the OSU Medical Center | https://pathology.osu.edu/ |

| Human GBM patient samples | Department of Pathology at the UCLA Medical Center | https://www.uclahealth.org/departments/pathology |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| Filipin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#F9765; CAS: 11078-21-0 |

| Chloroquine diphosphate salt | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#C6628; CAS: 50-63-5 |

| Cholesterol-Water Soluble | Sigma-Aldrich | Catt#C4951 |

| Paraformaldehyde | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#P6148; CAS: 30525-89-4 |

| Glutaraldehyde solution | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#G5882; CAS: 111-30-8 |

| G 418 disulfate salt | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#A1720; CAS: 108321-42-2 |

| Triton™ X-100 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#T8787; CAS: 9036-19-5 |

| Heparin sodium salt from porcine intestinal mucosa | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#H3393; CAS: 9041-08-1 |

| hEGF | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat# E9644; CAS: 62253-63-8 |

| Pepstatin A | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#P5318; CAS: 26305-03-3 |

| Leupeptin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#L2884; CAS: 103476-89-7 |

| Phenylmethanesulfonyl fluoride | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#P7626; CAS: 329-98-6 |

| Calpain Inhibitor I (ALLN) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#A6185; CAS: 110044-82-1 |

| Cholesterol Oxidase from microorganisms | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#C8868; CAS: 9028-76-6 |

| Hexadimethrine bromide (Polybrene) | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#H9268; CAS: 28728-55-4 |

| Methyl-β-cyclodextrin | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#C455; CAS: 128446-36-6 |

| Recombinant Human FGF | R&D Systems | Cat#4114-TC |

| BODIPY 493/503 | Invitrogen | Cat#D3922; CAS: 194235-40-0 |

| BODIPY-cholesterol (TopFluor Cholesterol) | Avanti Polar Lipids | Cat#810255; CAS: 878557-19-8 |

| DTT | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#R0861; CAS: 3483-12-3 |

| IPTG Solution | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#R1171; CAS: 367-93-1 |

| lysozyme | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#89833; CAS: 9001-63-2 |

| GST-mCherry-D4H | This paper | N/A |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| Amplex™ Red Cholesterol Assay Kit | Invitrogen | Cat#A12216 |

| iScript cDNA Synthesis Kit | Bio-rad | Cat#170-8891 |

| ECL kit | Cytiva Amersham | Cat#RPN2106 |

| SimpleChIP Plus Enzymatic Chromatin IP Kit | Cell Signaling | Cat#9005 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Human GBM cell: U87 | ATCC | Cat#ATCC HTB-14 |

| Human GBM cell: U87/EGFRvIII | A kind gift from Dr. Paul Mischel | N/A |

| Human GBM cell: U87/GFP-LC3 | This paper | N/A |

| Human GBM cell: T98 | ATCC | Cat#ATCC CRL-1690 |

| Human GBM cell: U251 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#09063001 |

| Human GBM cell: U251/mRFP-GFP-LC3 | This paper | N/A |

| Human GBM cell: U251/RFP-LC3 | This paper | N/A |

| Human lung cancer cell: H520 | ATCC | Cat#ATCC HTB-182 |

| Human lung cancer cell: HCC827 | ATCC | Cat#ATCC CRL-2868 |

| Human GBM primary cell: GBM30 | Geng et al.29 | N/A |

| Human GBM primary cell: GBM83 | Geng et al.29 | N/A |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Mouse: Athymic female nude (NCr-nu/nu) | OSU Target Validation Shared Resource | https://u.osu.edu/ccclabs/shared-resources-and-cores/ |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| Primers, see Table S1 | This paper | N/A |

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| EGFP-LC3 | Addgene | Cat#11546 |

| ptfLC3 | Addgene | Cat#21074 |

| pmRFP-LC3 | Addgene | Cat#21075 |

| pGEX-KG-D4H*-mCherry | Addgene | Cat#134604 |

| psPAX2 | Addgene | Cat#12260 |

| pMD2.G | Addgene | Cat#12259 |

| pmCherry-D4H | A kind gift from Dr. Gregory D. Fairn (University of Toronto, Canada) | N/A |

| pRL Renilla Luciferase Control Reporter Vectors | Promega | Cat#E2261 |

| Non-mammalian shRNA control | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#SHC002 |

| ATG5 shRNA-1 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#TRCN0000330394 |

| ATG5 shRNA-2 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#TRCN0000330392 |

| SREBP-1 shRNA-1 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#TRCN0000421299 |

| SREBP-1 shRNA-2 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#TRCN0000422088 |

| SREBP-2 shRNA | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#TRCN00000431900 |

| SOAT1 shRNA-1 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#TRCN0000036440 |

| SOAT1 shRNA-2 | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#TRCN0000234512 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| GraphPad Prism 7 | GraphPad | https://www.graphpad.com/scientific-software/prism/ |

| ImageJ | ImageJ | https://imagej.net/Downloads |

| ZEN 2 (blue edition) | Zeiss | https://www.zeiss.com/microscopy/us/downloads.html |

| Microsoft Excel | Microsoft | https://www.microsoft.com/en-us/microsoft-365/excel |

| Other | ||

| X-tremeGENE™ HP DNA Transfection Reagent | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#6366236001 |

| Lipoprotein Deficient Serum from fetal calf | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#S5394 |

| cOmplete™, Mini, EDTA-free Protease Inhibitor Cocktail | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#11836170001 |

| PhosSTOP™ | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#4906845001 |

| Microcon-30kDa Centrifugal Filter Unit with Ultracel-30 membrane | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#MRCF0R030 |

| X-tremeGENE™ HP DNA Transfection Reagent | Sigma-Aldrich | Cat#6366236001 |

| Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX Transfection Reagent | Invitrogen | Cat#13778150 |

| ProLong™ Gold Antifade Mountant with DNA Stain DAPI | Invitrogen | Cat#P36935 |

| TRIzol™ Reagent | Invitrogen | Cat#15596018 |

| Scigen Tissue-Plus™ O.C.T. Compound | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#23-730-571 |

| RIPA buffer | Thermo Fisher Scientific | Cat#NC9484499 |

| Dulbecco’s modified Eagle’s media | Corning | Cat#15-013-CV |

| RPMI-1640 | Corning | Cat#15-040-CV |

| DMEM/F12 50/50 | Corning | Cat#90-090-PB |

| Fetal Bovine Serum (FBS) | Cytiva HyClone | Cat#SH3007103 |

| Glutathione Sepharose™ 4B Media | Cytiva | Cat#17075601 |

| L-glutamine | Gibco | Cat#25030164 |

| Geltrex™ LDEV-Free, hESC-Qualified, Reduced Growth Factor Basement Membrane Matrix | Gibco | Cat# A1413301 |

| B-27™ Supplement (50X), minus vitamin A | Gibco | Cat#12587010 |

| Trypan Blue Solution, 0.4% | Gibco | Cat#15250061 |

| Nitrocellulose membrane | Bio-rad | Cat#1620112 |

| PowerUp™ SYBR™ Green Master Mix | Applied Biosystems | Cat#A25778 |

| Bright-Glo™ Luciferase Assay System | Promega | Cat#E2610 |

| Renilla-Glo™ Luciferase Assay System | Promega | Cat#E2710 |

| Lenti-X Concentrator | Clontech | Cat#631231 |

Highlights.

Esterified cholesterol, not free cholesterol, is abundant in GBM tissues

Cholesterol reduction triggers autophagy by activation of SREBP-1

SREBP-1 upregulates autophagic and lysosomal genes to promote lipophagy

Liberated cholesterol from LDs maintains cholesterol homeostasis and GBM survival

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This work was supported by the National Institute of Neurological Disorders and Stroke (NINDS) and the National Cancer Institute (NCI) of United States grants R01NS104332, R01NS112935, R01CA227874, and R01CA240726 to D.G. and the American Cancer Society (United States) Research Scholar grant RSG-14-228-01–CSM to D.G. We also appreciate the support from an OSUCCC-Pelotonia (United States) Idea grant and the Urban and Shelly Meyer Foundation to D.G. and Art of The Brain to T.F.C. and W.H.Y. The graphical abstract was created with BioRender.com.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112790.

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

REFERENCES

- 1.Nohturfft A, and Zhang SC (2009). Coordination of lipid metabolism in membrane biogenesis. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 25, 539–566. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Guo D, Bell EH, and Chakravarti A (2013). Lipid metabolism emerges as a promising target for malignant glioma therapy. CNS Oncol. 2, 289–299. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Guo D, Hildebrandt IJ, Prins RM, Soto H, Mazzotta MM, Dang J, Czernin J, Shyy JYJ, Watson AD, Phelps M, et al. (2009). The AMPK agonist AICAR inhibits the growth of EGFRvIII-expressing glioblastomas by inhibiting lipogenesis. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 12932–12937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Guo D, Cloughesy TF, Radu CG, and Mischel PS (2010). A metabolic checkpoint that regulates the growth of EGFR activated glioblastomas. Cell Cycle 9, 211–212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cheng C, Geng F, Cheng X, and Guo D (2018). Lipid metabolism re-programming and its potential targets in cancer. Cancer Commun. 38, 27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Cheng C, Kelsey S, and Guo D (2023). Glutamine-released ammonia acts as an unprecedented signaling molecule activating lipid production. Genes Dis. 10, 307–309. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Holthuis JCM, and Menon AK (2014). Lipid landscapes and pipelines in membrane homeostasis. Nature 510, 48–57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ikonen E. (2008). Cellular cholesterol trafficking and compartmentalization. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 9, 125–138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.van Meer G, Voelker DR, and Feigenson GW (2008). Membrane lipids: where they are and how they behave. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol 9, 112–124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Iaea DB, and Maxfield FR (2015). Cholesterol trafficking and distribution. Essays Biochem. 57, 43–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheng X, Geng F, Pan M, Wu X, Zhong Y, Wang C, Tian Z, Cheng C, Zhang R, Puduvalli V, et al. (2020). Targeting DGAT1 Ameliorates Glioblastoma by Increasing Fat Catabolism and Oxidative Stress. Cell Metabol. 32, 229–242.e8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cheng X, Li J, and Guo D (2018). SCAP/SREBPs are Central Players in Lipid Metabolism and Novel Meta-bolic Targets in Cancer Therapy. Curr. Top. Med. Chem 18, 484–493. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Brown MS, Radhakrishnan A, and Goldstein JL (2018). Retrospective on Cholesterol Homeostasis: The Central Role of Scap. Annu. Rev. Biochem 87, 783–807. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Guo D. (2016). SCAP links glucoseto lipid metabolism in cancer cells. Molecular & cellular oncology 3, e1132120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Goldstein JL, and Brown MS (2009). The LDL receptor. Arterioscler. Thromb. Vasc. Biol 29, 431–438. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kwon HJ, Abi-Mosleh L, Wang ML, Deisenhofer J, Goldstein JL, Brown MS, and Infante RE (2009). Structure of N-terminal domain of NPC1 reveals distinct subdomains for binding and transfer ofcholesterol. Cell 137, 1213–1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wen PY, and Kesari S (2008). Malignant gliomas in adults. N. Engl. J. Med 359, 492–507. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Cloughesy TF, Cavenee WK, and Mischel PS (2014). Glioblastoma: from molecular pathology to targeted treatment. Annu. Rev. Pathol 9, 1–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bell EH, and Guo D (2012). Biomarkers for malignant gliomas. Malignant Gliomas, Radiation Medicine Rounds 3. 389–357. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Guo D, Reinitz F, Youssef M, Hong C, Nathanson D, Akhavan D, Kuga D, Amzajerdi AN, Soto H, Zhu S, et al. (2011). An LXR agonist promotes GBM cell death through inhibition of an EGFR/AKT/SREBP-1/LDLR-dependent pathway. Cancer Discov. 1, 442–456. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Ru P, Williams T, Chakravarti A, and Guo D (2013).Tumor metabolism of malignant gliomas. Cancers 5, 1469–1484. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ackerman D, and Simon MC (2014). Hypoxia, lipids, and cancer: surviving the harsh tumor microenvironment. Trends Cell Biol. 24, 472–478. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Gullino PM, Grantham FH, and Courtney AH (1967). Glucose consumption by transplanted tumors in vivo. Cancer Res. 27, 1031–1040. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Hirayama A, Kami K, Sugimoto M, Sugawara M, Toki N, Onozuka H, Kinoshita T, Saito N, Ochiai A, Tomita M, et al. (2009). Quantitative metabolome profiling of colon and stomach cancer microenvironment by capillary electrophoresis time-of-flight mass spectrometry. Cancer Res. 69, 4918–4925. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wu X, Geng F, Cheng X, Guo Q, Zhong Y, Cloughesy TF, Yong WH, Chakravarti A, and Guo D (2020). Lipid Droplets Maintain Energy Homeostasis and Glioblastoma Growth via Autophagic Release of Stored Fatty Acids. iScience 23, 101569. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Farese RV Jr., and Walther TC (2009). Lipid droplets finally get a little R-E-S-P-E-C-T. Cell 139, 855–860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Walther TC, and Farese RV Jr. (2012). Lipid droplets and cellular lipid metabolism. Annu. Rev. Biochem 81, 687–714. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Geng F, Cheng X, Wu X,Yoo JY, Cheng C, Guo JY, Mo X, Ru P, Hurwitz B, Kim SH, et al. (2016). Inhibition of SOAT1 suppresses glioblastoma growth via blocking SREBP-1-mediated lipogenesis. Clin. Cancer Res 22, 5337–5348. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Guo D, and Guo D (2017). Lipid droplets, potential biomarkerand metabolic target in glioblastoma. Intern. Med. Rev 3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Cheng X, Geng F, and Guo D (2020). DGAT1 protects tumor from lipotoxicity, emerging as a promising metabolic target for cancer therapy. Mol. Cell. Oncol 7, 1805257. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Qiu B, Ackerman D, Sanchez DJ, Li B, Ochocki JD, Grazioli A, Bobrovnikova-Marjon E, Diehl JA, Keith B, and Simon MC (2015). HI-F2alpha-Dependent Lipid Storage Promotes Endoplasmic Reticulum Homeostasis in Clear-Cell Renal Cell Carcinoma. Cancer Discov. 5, 652–667. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Accioly MT, Pacheco P, Maya-Monteiro CM, Carrossini N, Robbs BK, Oliveira SS, Kaufmann C, Morgado-Diaz JA, Bozza PT, and Viola JPB (2008). Lipid bodies are reservoirs of cyclooxygenase-2 and sites of prostaglandin-E2 synthesis in colon cancer cells. Cancer Res. 68, 1732–1740. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Yue S, Li J, Lee SY, Lee HJ, Shao T, Song B, Cheng L, Masterson TA, Liu X, Ratliff TL, and Cheng JX (2014). Cholesteryl ester accumulation induced by PTEN loss and PI3K/AKT activation underlies human prostate cancer aggressiveness. Cell Metabol. 19, 393–406. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Kou Y, Geng F, and Guo D (2022). Lipid Metabolism in Glioblastoma: From De Novo Synthesis to Storage. Biomedicines 10, 1943. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Klionsky DJ, Abdalla FC, Abeliovich H, Abraham RT, Acevedo-Arozena A, Adeli K, Agholme L, Agnello M, Agostinis P, Aguirre-Ghiso JA, et al. (2012). Guidelines for the use and interpretation of assays for monitoring autophagy. Autophagy 8, 445–544. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Solomon VR, and Lee H (2009). Chloroquine and its analogs: a new promiseofan old drug for effective and safe cancer therapies. Eur. J. Pharmacol 625,220–233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Cheng C, Ru P, Geng F, Liu J, Yoo JY, Wu X, Cheng X, Euthine V, Hu P, Guo JY, et al. (2015). Glucose-Mediated N-glycosylation of SCAP Is Essential for SREBP-1 Activation and Tumor Growth. Cancer Cell 28, 569–581. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Hölttä-Vuori M, Uronen RL, Repakova J, Salonen E, Vattulainen I, Panula P, Li Z, Bittman R, and Ikonen E (2008). BODIPY-cholesterol: a newtool to visualize sterol trafficking in living cellsand organisms.Traffic 9, 1839–1849. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Ru P, Hu P, Geng F, Mo X, Cheng C, Yoo JY, Cheng X, Wu X, Guo JY, Nakano I, et al. (2016). Feedback Loop Regulation of SCAP/SREBP-1 by miR-29 Modulates EGFR Signaling-Driven Glioblastoma Growth. Cell Rep. 16, 1527–1535. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Castro-Mondragon JA, Riudavets-Puig R, Rauluseviciute I, Lemma RB, Turchi L, Blanc-Mathieu R, Lucas J, Boddie P, Khan A, Manosalva Pérez N, et al. (2022). JASPAR 2022: the 9th release of the open-access database of transcription factor binding profiles. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D165–D173. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Mahammad S, and Parmryd I (2015). Cholesterol depletion using methyl-beta-cyclodextrin. Methods Mol. Biol 1232, 91–102. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Börnig H, and Geyer G (1974). Staining of cholesterol with the fluorescent antibiotic "filipin". Acta Histochem. 50, 110–115. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Maekawa M, and Fairn GD (2015). Complementary probes reveal that phosphatidylserine is required for the proper transbilayer distribution of cholesterol. J. Cell Sci 128, 1422–1433. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Chu BB, Liao YC, Qi W, Xie C, Du X, Wang J,Yang H, Miao HH, Li BL, and Song BL (2015). Cholesterol transport through lysosome-peroxisome membrane contacts. Cell 161, 291–306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Chang TY, Chang CCY, Ohgami N, and Yamauchi Y (2006). Cholesterol sensing, trafficking, and esterification. Annu. Rev. Cell Dev. Biol 22, 129–157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Mizushima N, and Komatsu M (2011). Autophagy: renovation of cells and tissues. Cell 147, 728–741. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Mizushima N, Levine B, Cuervo AM, and Klionsky DJ (2008). Autophagy fights disease through cellular self-digestion. Nature 451, 1069–1075. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Seo YK, Jeon TI, Chong HK, Biesinger J, Xie X, and Osborne TF (2011). Genome-wide localization of SREBP-2 in hepatic chromatin predicts a role in autophagy. Cell Metabol. 13, 367–375. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Seo YK, Chong HK, Infante AM, Im SS, Xie X, and Osborne TF (2009). Genome-wide analysis of SREBP-1 binding in mouse liver chromatin reveals a preference for promoter proximal binding to a new motif. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 106, 13765–13769. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Nguyen TTP, Kim DY, Lee YG, Lee YS, Truong XT, Lee JH, Song DK, Kwon TK, Park SH, Jung CH, et al. (2021). SREBP-1c impairs ULK1 sulfhydration-mediated autophagic flux to promote hepatic steatosis in high-fat-diet-fed mice. Mol. Cell 81, 3820–3832.e7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Bao J, Zhu L, Zhu Q, Su J, Liu M, and Huang W (2016). SREBP-1 is an independent prognostic marker and promotes invasion and migration in breast cancer. Oncol. Lett 12, 2409–2416. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Sun Y, He W, Luo M, Zhou Y, Chang G, Ren W, Wu K, Li X, Shen J, Zhao X, and Hu Y (2015). SREBP1 regulates tumorigenesis and prognosis of pancreatic cancer through targeting lipid metabolism. Tumour Biol. 36, 4133–4141. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Gao Y, Nan X, Shi X, Mu X, Liu B, Zhu H, Yao B, Liu X, Yang T, Hu Y, and Liu S (2019). SREBP1 promotes the invasion of colorectal cancer accompanied upregulation of MMP7 expression and NF-kappaB pathway activation. BMC Cancer 19, 685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Nie LY, Lu QT, Li WH, Yang N, Dongol S, Zhang X, and Jiang J (2013). Sterol regulatory element-binding protein 1 is required for ovarian tumor growth. Oncol. Rep 30, 1346–1354. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Xu D, Wang Z, Xia Y, Shao F, Xia W, Wei Y, Li X, Qian X, Lee JH, Du L, et al. (2020). The gluconeogenic enzyme PCK1 phosphorylates INSIG1/2 for lipogenesis. Nature 580, 530–535. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Guo D, Prins RM, Dang J, Kuga D, Iwanami A, Soto H, Lin KY, Huang TT, Akhavan D, Hock MB, et al. (2009). EGFR signaling through an Akt-SREBP-1-dependent, rapamycin-resistant pathway sensitizes glioblastomas to antilipogenic therapy. Sci. Signal 2, ra82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Guo D, Bell EH, Mischel P, and Chakravarti A (2014). Targeting SREBP-1-driven lipid metabolism to treat cancer. Curr. Pharm. Des 20, 2619–2626. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Jackson WT, Giddings TH Jr., Taylor MP, Mulinyawe S, Rabinovitch M, Kopito RR, and Kirkegaard K (2005). Subversion of cellular autophagosomal machinery by RNA viruses. PLoS Biol. 3, e156. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Kimura S, Noda T, and Yoshimori T (2007). Dissection of the autophagosome maturation process by a novel reporter protein, tandem fluorescent-tagged LC3. Autophagy 3, 452–460. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Singh R, Kaushik S, Wang Y, Xiang Y, Novak I, Komatsu M, Tanaka K, Cuervo AM, and Czaja MJ (2009). Autophagy regulates lipid metabolism. Nature 458, 1131–1135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Lim CY, Davis OB, Shin HR, Zhang J, Berdan CA, Jiang X, Counihan JL, Ory DS, Nomura DK, and Zoncu R (2019). ER-lysosome contacts enable cholesterol sensing by mTORC1 and drive aberrant growth signalling in Niemann-Pick type C. Nat. Cell Biol 21, 1206–1218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All the data reported in this paper are available from the lead contact upon request. This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.