Abstract

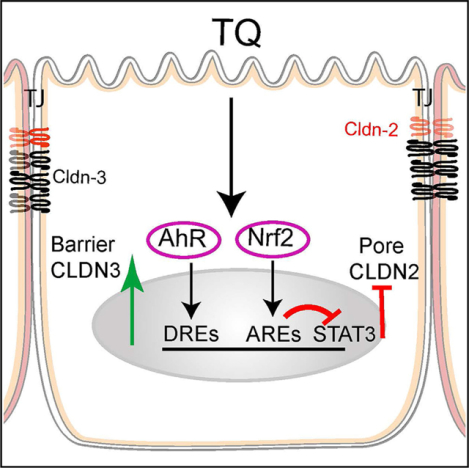

Defects in intestinal epithelial tight junctions (TJs) allow paracellular permeation of noxious luminal antigens and are important pathogenic factors in inflammatory bowel disease (IBD). We show that alpha-tocopherylquinone (TQ), a quinone-structured oxidation product of vitamin E, consistently enhances the intestinal TJ barrier by increasing barrier-forming claudin-3 (CLDN3) and reducing channel-forming CLDN2 in Caco-2 cell monolayers (in vitro), mouse models (in vivo), and surgically resected human colons (ex vivo). TQ reduces colonic permeability and ameliorates colitis symptoms in multiple colitis models. TQ, bifunctionally, activates both aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) and nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathways. Genetic deletion studies reveal that TQ-induced AhR activation transcriptionally increases CLDN3 via xenobiotic response element (XRE) in the CLDN3 promoter. Conversely, TQ suppresses CLDN2 expression via Nrf2-mediated STAT3 inhibition. TQ offers a naturally occurring, non-toxic intervention for enhancement of the intestinal TJ barrier and adjunct therapeutics to treat intestinal inflammation.

Graphical abstract

In brief

Ganapathy et al. show that alphatocopherylquinone reduces intestinal paracellular permeability via an AhR-mediated increase in tight junction barrier-forming CLDN3 and an Nrf2-mediated reduction in channel-forming CLDN2 expression. α-tocopherylquinone-mediated enhancement of the tight junction barrier is associated with amelioration of experimental colitis.

INTRODUCTION

Apically located inter-cellular tight junctions (TJ) polarize intestinal epithelial cells into apical and basolateral regions (fence function) and regulate passive diffusion of solutes and macromolecules in the space between adjacent epithelial cells (gate function),1 acting as a barrier against paracellular permeation of noxious luminal antigens.2 TJs consist of tetraspan membrane proteins (e.g., occludin and claudins) linked by cytoplasmic plaque protein zonula occludens protein-1 and - 2 (ZO-1 and ZO-2) to the cytoskeleton. Claudin family proteins are functionally diverse, crucial components of TJs. Claudins such as claudin-1 (CLDN1), CLDN3, and CLDN4 establish the paracellular barrier, while CLDN2 forms a charge-/size-selective channel.3–5

Inflammatory bowel disease (IBD) is a chronic, incurable disease primarily diagnosed in adolescents and young adults. Nearly four million patients with IBD are expected in North America alone by 2030.6 A defective TJ barrier is associated with various etiological factors in IBD such as genetic predisposition (leading to immunological abnormalities), dysbiosis of the gut microbiota, and environmental influences. The defects in the intestinal TJ barrier also lead to increased antigenic penetration, resulting in an intensified intestinal inflammatory response.4,7 In clinical studies, a persistent increase in intestinal TJ permeability predicts poor clinical outcomes, and normalization of intestinal permeability is correlated with clinical improvement of active IBD.8,9 Thus, enhancement of the intestinal TJ barrier can help therapeutic efforts against intestinal inflammation.

α-Tocopherylquinone (αTQ; referred to as TQ in this study) is a quinone-structured endogenous derivative of α-tocopherol (an active form of vitamin E). TQ is reported to exhibit distinct activity compared with that of α-tocopherol, but there have been limited studies on the effect of TQ on host health. TQ has been shown to inhibit the androgen receptor or the formation of Aβ42 fibrils owing to its p-benzoquinone central ring structure.10,11 TQ also inhibits cytotoxicity by decreasing reactive oxygen species and inflammatory cytokines,11 and it is reported to be non-toxic in multiple cell lines.12–14 Also, a clinical trial has examined the potential value of TQ in the treatment of Friedreich’s ataxia.15 The biological activity of TQ in intestinal epithelial cells is not well understood. Earlier reports have shown the bifunctional activity of a variety of quinones, which induce activation of aryl hydrocarbon receptor (AhR) as well as nuclear factor erythroid factor 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2) pathways. These quinones activate AhR via covalent binding, resulting in the upregulation of cytochrome P450 1A1 (CYP1A1),16 and activate Nrf2 indirectly via AhR-regulated enzymes or directly by S-arylation of its negative regulator Keap1.16–18

The environmental sensor, AhR, binds to a variety of synthetic and natural compounds and acts as a class I, basic-helix-loop-helix transcriptional regulator.19 Upon activation, AhR translocates into the nucleus and dimerizes with the AhR nuclear translocator (ARNT) protein. This AhR-ARNT dimer binds to the xenobiotic-responsive elements (XREs; also known as dioxin response elements [DREs]) in gene regulatory regions and regulates the expression of a diverse set of genes.20 Prior studies have demonstrated important functions of AhR in intestinal stem cell differentiation, intestinal homeostasis, and immune regulation in the gut.21,22 AhR activation has also been shown to improve colitis outcomes in animal IBD models.23–29 Nrf2 is a transcription factor that binds the antioxidant response element (ARE) to regulate the expression of genes involved in cellular defense against oxidative or electrophilic stress. In addition, the Keap1 (Kelch-like ECHassociated protein)/Nrf2/ARE signaling pathway is reported to inhibit inflammation by regulating anti-inflammatory gene expression.30 Nrf2 knockout (KO)mice are reported to have impaired barrier function in the esophageal epithelium.31 The Nrf2 pathway plays an essential role in the development and maintenance of the gastrointestinal tract and is proposed to be a promising target in preventing IBD.30,32

In the present study, we provide evidence that TQ enhances the intestinal TJ barrier and reduces TJ permeability by differential regulation of CLDNs in human intestinal Caco-2 cells, mouse colons, and human colonic mucosal explants. Our results demonstrate that orally administered TQ preserved the TJ barrier and reduced intestinal inflammation in dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) colitis (acute and chronic), 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) colitis, and T cell transfer-mediated chronic colitis. We show that TQ increases barrier-forming CLDN3 expression via an AhR-dependent mechanism and that it reduces channel-forming CLDN2 via Nrf2/SHP signaling cascade by inhibiting STAT3 activation. Thus, TQ offers a potential tool for the enhancement of the intestinal TJ barrier and oral therapeutics in intestinal inflammation.

RESULTS

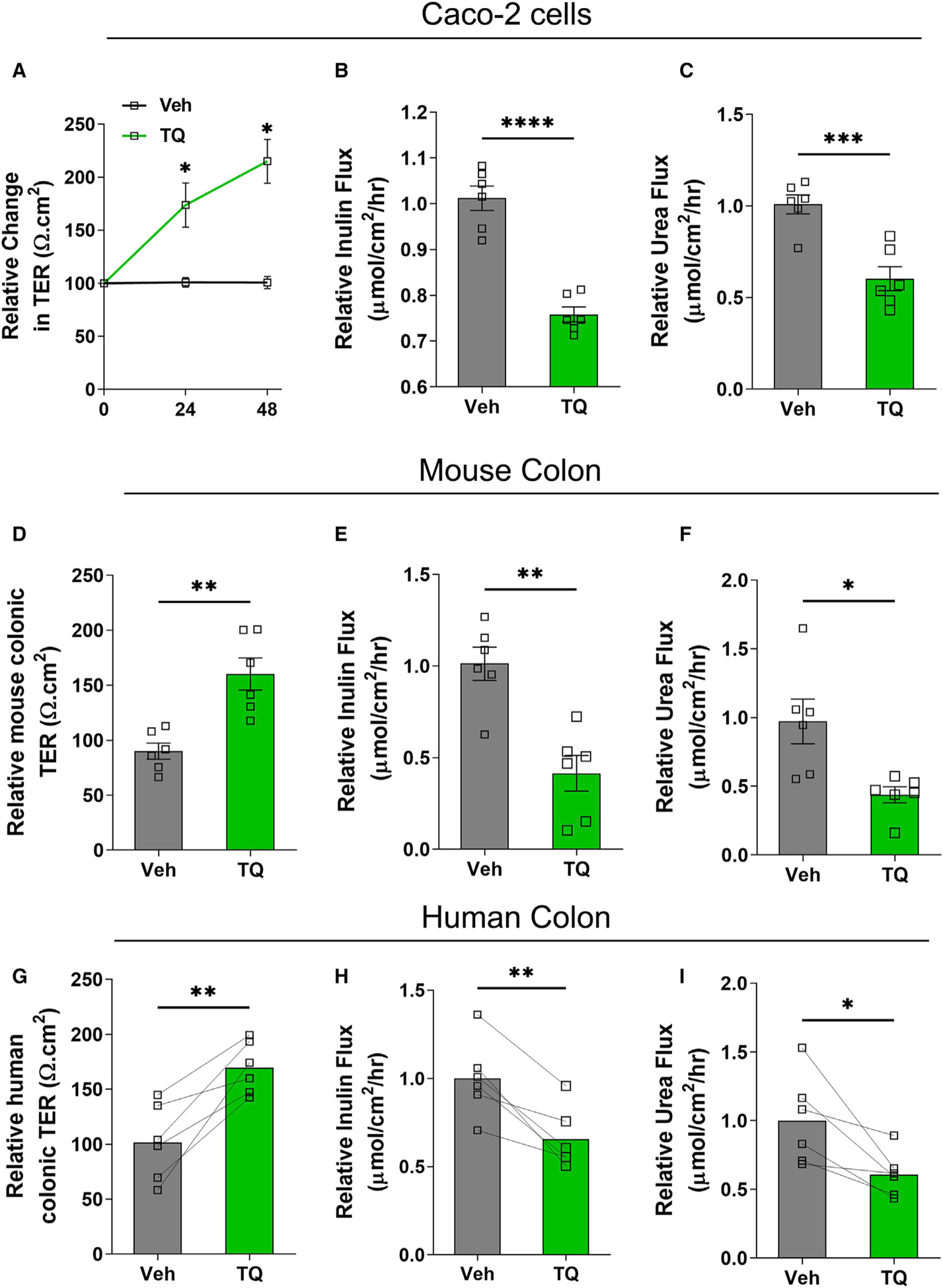

TQ enhances intestinal TJ barrier function

To investigate the effect of TQ on intestinal epithelial TJ barrier function, we treated confluent human intestinal Caco-2 cell monolayers with TQ (25 μM) or vehicle. TQ increased the Caco-2 transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) in a time-dependent manner (Figure 1A). As an alternate assessment of TQ’s effect on the TJ barrier, we examined the apical-to-basolateral flux of paracellular probes. TQ reduced the paracellular flux of large-sized inulin (~12-Å diameter, molecular weight of 5,000 Da) as well as small-sized urea (~3.8-Å diameter, molecular weight of 60 Da) (Figures 1B and 1C). Next, we examined the effect of TQ on mouse colonic mucosa. The wild-type adult C57BL/6J mice were treated with TQ (50 mg/kg/day, oral gavage, dose based on previous studies33–35) or vehicle for 3 days, and the unstripped mouse colon samples were mounted in Ussing chambers. TQ administration increased the mouse colonic TER (Figure 1D) and reduced the mucosal-to-serosal paracellular flux of inulin and urea (Figures 1E and 1F) when compared with vehicle-treated WT mice. TQ administration also increased the TER and reduced the mucosal-to-serosal paracellular flux of inulin and urea in mouse small intestines (data not shown). Moreover, to demonstrate the clinical relevance of our findings in cell culture and mouse studies, we used explant cultures of surgically resected healthy human colonic mucosa to confirm the effect of TQ on the human colonic TJ barrier. 18 h after culturing the paired colonic mucosal specimens (~0.25 cm2, stripped of muscular serosal layers) on gelatin sponges (with vehicle or 25 μM TQ), the colonic mucosal tissues were mounted on Ussing chambers to assess TJ barrier (TER and paracellular flux). We found that TQ treatment increased TER (Figure 1G) and reduced inulin and urea flux in human colonic mucosal explants (Figures 1H and 1I). Overall, these data demonstrate the consistent TJ barrier-enhancing effect of TQ on in vitro cell lines and in vivo mouse colonic mucosa as well as ex vivo human colonic mucosal samples.

Figure 1. TQ enhances the intestinal TJ barrier.

(A–C) Caco-2 cell monolayers grown on Transwells were treated with TQ (25 μM) or vehicle for 48 h. TQ increased transepithelial electrical resistance (TER) (A) and reduced paracellular inulin (B) and urea (C) flux. n = 6, *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001.

(D–F) Wild-type C57BL/6J mice (n = 6) were treated with TQ (50 mg/kg/day, oral gavage) or vehicle, and the mice’s colon tissues were mounted in Ussing chambers after 48 h of TQ administration. TQ increased mouse colonic TER (D) and reduced paracellular inulin (E) and urea (F) flux. *p < 0.05; **p < 0.01.

(G–I) Surgically resected normal human colonic tissues were stripped of the sero-muscular layer, and the colonic mucosa was cultured using a gelatin sponge for 18 h with TQ (25 mM) or vehicle and mounted in Ussing chambers. TQ treatment increased the human colonic TER (G) and reduced colonic inulin (H) and urea (I) flux. n = 6. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

Veh, vehicle; TQ, α-tocopherylquinone.

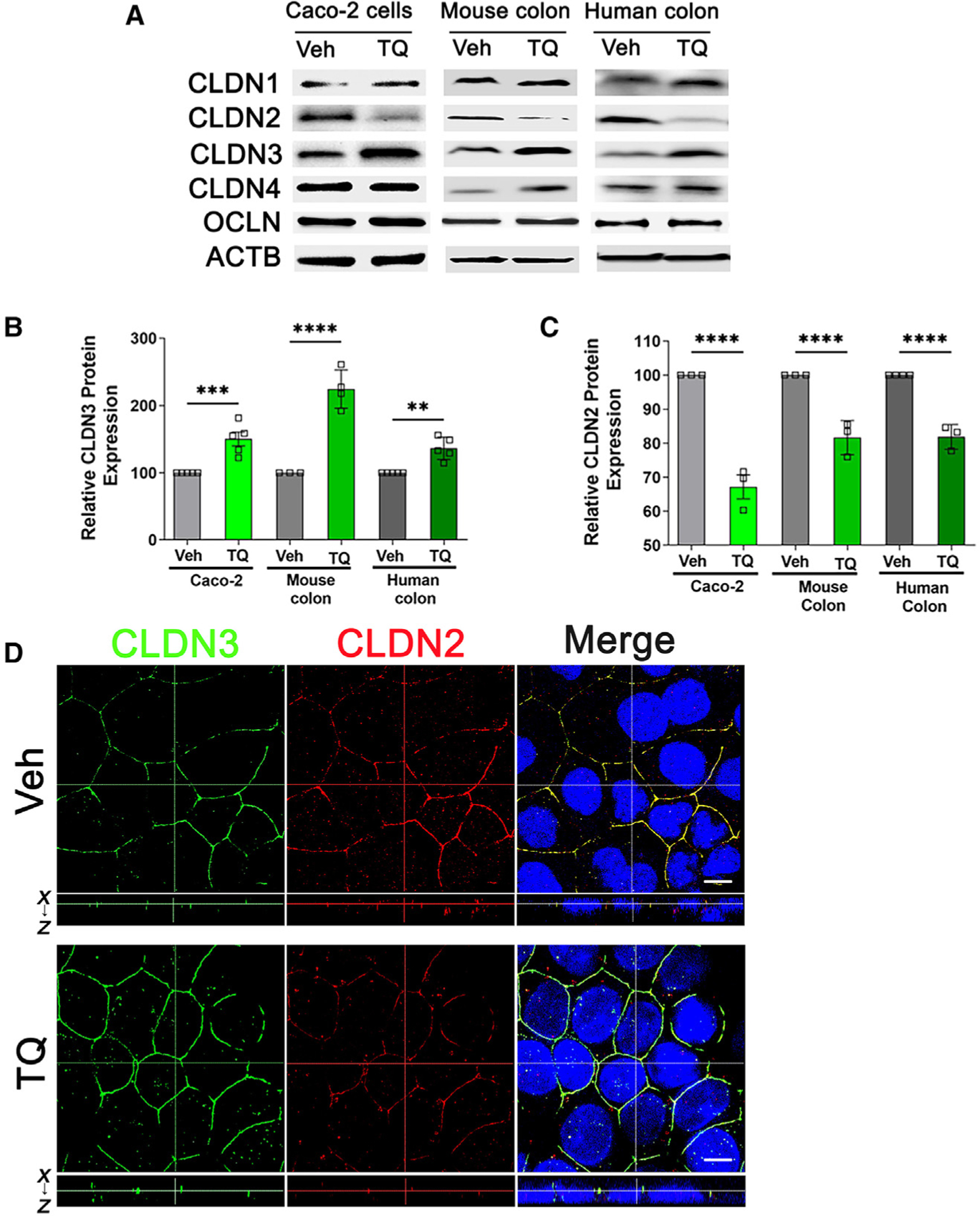

TQ differentially modulates TJ CLDN expression

As the TJs have size- and charge-selective pathways that are regulated by specific proteins,3,36 we examined TJ composition by assessing the expression of TJ proteins after TQ treatment in Caco-2 cells, mouse colon, and human colonic mucosal explants. By western blot analysis, we found that TQ consistently increased protein expression of CLDN3 and reduced CLDN2 expression in all three tested models. TQ treatment did not affect the levels of another known TJ protein, occludin (Figures 2A–2C). The level of TJ-associated Marvel domain-containing protein (MARVELD2), tricellulin, which also regulates macromolecular flux,37 was not altered after TQ treatment (Figure S1). The TQ-mediated increase in CLDN3 and reduction in CLDN2 are consistent with the increase in TER and decreased TJ permeability of small- and large-sized paracellular probes (Figure 1). CLDN3 is known to seal the paracellular pathway against the passage of uncharged small and large solutes, while CLDN2 regulates the small-sized pore pathway.38,39 Thus, TQ had opposing effects on TJ pathways: TQ increased barrier-forming CLDN3 levels and reduced water- and small cation-selective CLDN2 channel levels. Confocal immunolocalization studies further confirmed the increased CLDN3 and reduced CLDN2 levels in the TQ-treated Caco-2 cell membrane (Figure 2D). Additionally, colons from TQ-treated mice showed increased CLDN3 staining along the crypt-villus axis and reduced CLDN2 staining in the colonic crypts (Figure S2). TQ treatment of human colonic mucosal explants also increased CLDN3 staining in the surface epithelium and reduced CLDN2 staining in the colonic crypts (Figure S3). Overall, these in vitro and in vivo studies indicated that TQ differentially increased barrier-forming CLDN3 and reduced channel-forming CLDN2, consistent with the increased TER and decreased TJ permeability.

Figure 2. TQ differentially modulates TJ claudin-2 and -3 expression.

(A–C) Protein lysate of Caco-2 cells treated with TQ (25 μM, 48 h), colonic mucosa of mice treated with TQ (50 mg/kg/day, oral gavage, 48 h), and human colonic mucosa treated with TQ (25 μM, 18 h) or vehicle were studied for candidate claudins protein expression by western blot. TQ consistently increased barrier-forming claudin-3 (CLDN3) and reduced channel-forming CLDN2 protein expression in all tested models (A). The densitometry for CLDN3 (B) and CLDN2 (C) was quantified using ImageJ software. β-Actin (ACTB) was used as a loading control. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001.

(D) Confocal images of CLDN3 and CLDN2 staining in Caco-2 cells. TQ increased CLDN3 (green) in the Caco-2 cell membrane and reduced CLDN2 (red) in the Caco-2 cell membrane Nuclei are shown in blue in the merged panels. The dotted lines represent optical levels in x-y and x-z planes. White bar: 5 μm. Veh, vehicle; TQ, α-tocopherylquinone. These data are representative of several areas from n = 7.

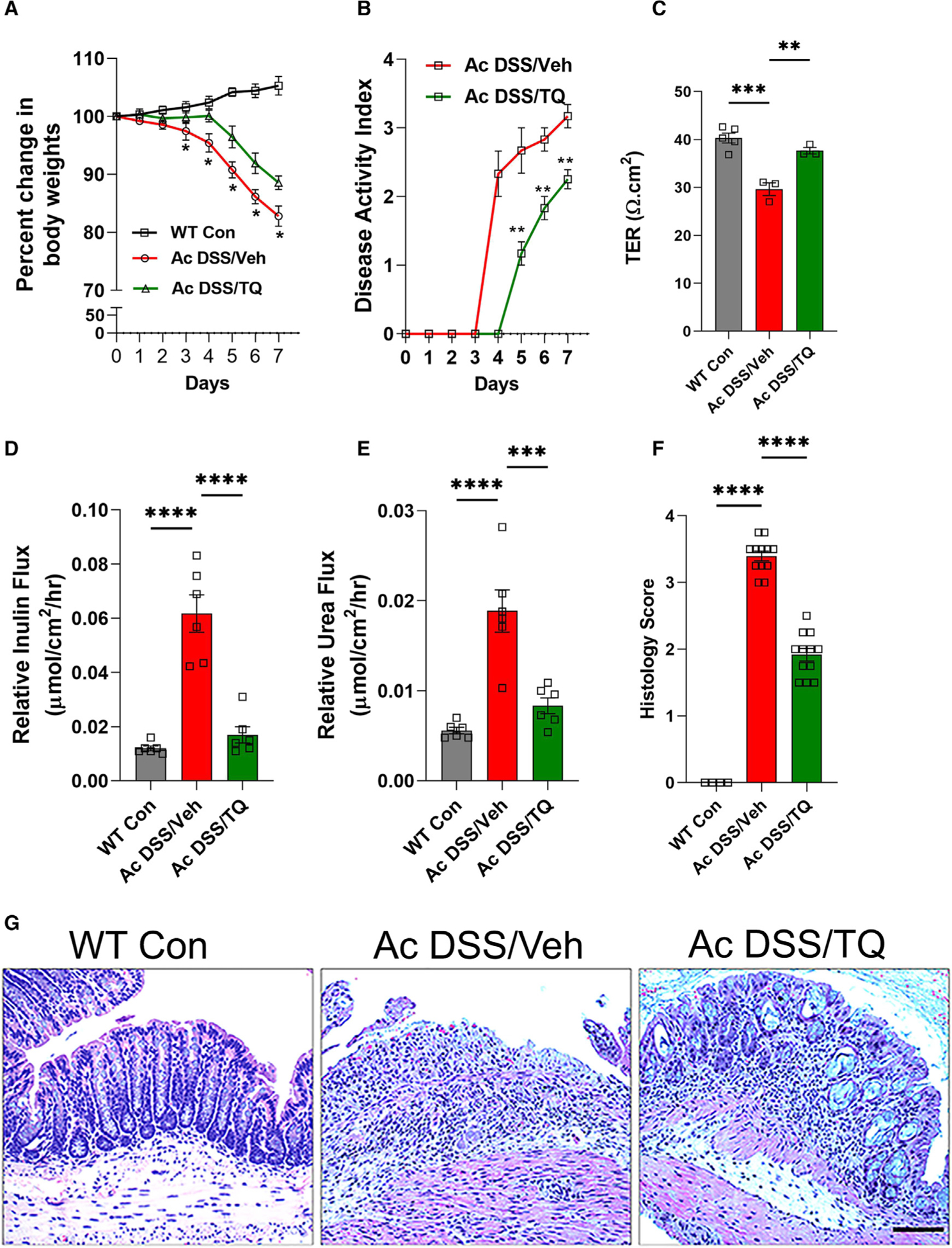

TQ ameliorates experimental DSS colitis

We, and others, have shown that enhancement of the TJ barrier ameliorates intestinal inflammation.40–43 Since we observed that TQ increases baseline TER and reduces paracellular TJ permeability in mouse colon, we hypothesized that TQ treatment would attenuate experimental colitis. Initially, we examined the effect of TQ in the acute DSS (Ac DSS)-induced colitis model. TQ treatment attenuated DSS-induced loss of body weight and disease activity index (Figures 3A and 3B). Ussing chamber studies showed that TQ attenuated the Ac DSS-induced decrease in mouse colonic TER (Figure 3C) and prevented the DSS-induced multi-fold increase in mouse colonic paracellular inulin and urea permeability (Figures 3D and 3E). Moreover, TQ also ameliorated colonic histological changes of DSS colitis and reduced histological scores (Figures 3F and 3G).

Figure 3. TQ reduces the severity of acute DSS colitis.

In the acute DSS (Ac DSS) colitis (2.5% DSS, 7 days) model, treatment with TQ (Ac DSS/TQ) (50 mg/kg/day, oral gavage) or vehicle (Ac DSS/Veh) on C57BL/6J mice was started 2 days before DSS treatment and continued throughout the treatment.

(A and B) Mouse body weight was measured throughout the experiment. The disease activity index was calculated based on the loss of body weight, ruffled fur, occult blood, and stool consistency. TQ attenuated DSS-induced loss of body weight (A) and the disease activity index (B). *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01.

(C–E) After Ac DSS with TQ or vehicle treatment, the unstripped mice colonic tissues were mounted in Ussing chambers. TQ attenuated the DSS-induced decrease in mouse colonic TER (C) and prevented the DSS-induced multi-fold increase in mouse colonic paracellular flux of inulin (D) and urea (E). **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001.

(F and G) The histological score of Ac DSS colitis was reduced by TQ (F). ****p < 0.001. The DSS-induced loss of colonic crypts, epithelial ulceration, and mucosal infiltration of inflammatory cells was attenuated by TQ in histological examination (G). Black bar: 100 μm. Representation of 3 independent experiments (n = 3 per experiment).

To be more relevant to the chronic nature of IBD, apart from Ac DSS colitis, we examined the effect of TQ in the chronic DSS (Ch DSS) colitis mice model. Our results show that TQ ameliorated the Ch DSS-induced loss of body weight (Figure S4A). Ussing chamber studies showed that TQ attenuated the Ch DSS-induced decrease in mouse colonic TER (Figure S4B), the paracellular flux of inulin (Figure S4C), as well as urea (Figure S4D), and histological changes of colitis (Figures S4E and S4F). Moreover, consistent with the barrier-enhancing effect of TQ in both the DSS mice models, TQ administration also attenuated the loss of barrier-forming CLDN3 and prevented the increase in channel-forming CLDN2 levels in both Ac (Figures S5A–S5C) and Ch DSS colitis mice (Figures S5D–S5F) models.

TQ reduces the severity of TNBS colitis

As an alternative model to chemical-induced DSS colitis, we also investigated the effect of the vehicle and TQ on TNBS colitis in the BALB/c mice model. Daily gavaging of TQ starting 2 days before the intracolonic TNBS administration (100 μL 2.5% TNBS in ethanol) attenuated the severity of TNBS colitis in terms of TNBS-induced body weight loss (Figure S6A) and increases in colonic inulin and urea permeability (Figures S6B and S6C). In histological examination, the vehicle-treated mice colons showed diffuse obliteration of colonic mucosal architecture with loss of surface epithelium and crypts, inflammatory infiltration, hemorrhages, and necrosis that extended to the muscular layers. TQ administration, however, attenuated inflammatory changes in the colon (Figures S6D and S6E). Thus, TQ demonstrated beneficial effects against experimental TNBS colitis.

TQ dampens T cell transfer chronic colitis

As an alternative, non-chemical, chronic colitis model, we also investigated the effect of the vehicle and TQ on T cell transferinduced chronic colitis in Rag-/- mice. The mice were gavaged with TQ for 7 days beginning the first day the colitis symptoms were observed from T cell transfer. TQ reduced the multi-fold increase in colonic inulin and urea permeability caused by T cell transfer (Figures S7A and S7B). The histological examination also revealed the protective effect of TQ against T cell transfer induced colitis. TQ administration inhibited the disruption of colonic mucosal architecture, loss of surface epithelium and crypts, inflammatory infiltration, hemorrhages, and necrosis compared with that observed in vehicle-treated mice (Figures S7C and S7D).

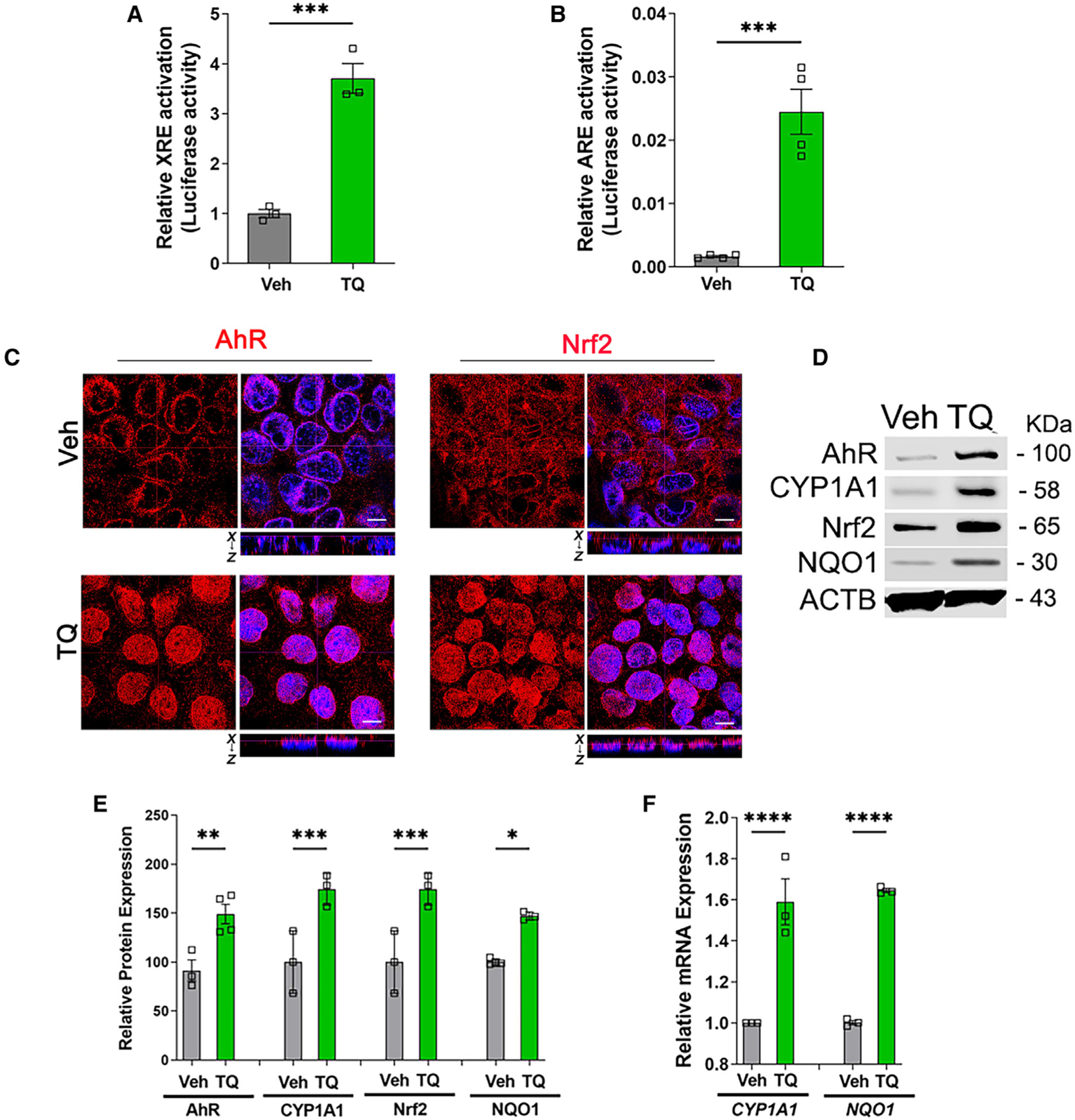

Identification of TQ as an AhR and Nrf2 activator

Earlier studies have reported the bifunctional activity of quinone-structured compounds such as 1,4-benzoquinone (BQ) and tertbutyl-1, 4-benzoquinone (TBQ) to activate both AhR and Nrf2 pathways.16 Once activated by a ligand, AhR and Nrf2 transcription factors translocate into the nucleus and modulate transcription of multiple target genes via binding to XREs and AREs, respectively. To test whether TQ induces AhR/XRE and Nrf2/ARE activation, Caco-2 cells were transfected with an XRE-luciferase plasmid (pGL4.43, Promega) and ARE-luciferase plasmid (pGL4.37, Promega) individually and assayed for luciferase activity in the presence of TQ or vehicle. The TQ treatment increased both XRE (Figure 4A) as well as ARE (Figure 4B) luciferase activity, showing that TQ indeed activates both AhR and Nrf2 pathways. To further corroborate these results, confocal microscopy was performed, which showed increased nuclear translocation of AhR and Nrf2 upon TQ treatment(Figure 4C).Western blot analysis revealed that TQ treatment increased the protein expression of AhR and Nrf2 along with their downstream proteins CYP1A1 and NAD(P)H dehydrogenase [quinone] 1 (NQO1), respectively (Figures 4D and 4E). Moreover, qPCR analysis found increased mRNA expression of CYP1A1 and NQO1 (Figure 4F), which are downstream gene targets of the AhR and Nrf2 pathways, respectively. This increased mRNA expression of the downstream genes further confirms the TQ-mediated activation of transcriptional factors AhR and Nrf2. Overall, the TQ-mediated increase in XRE and ARE luciferase activity, the increase in protein levels and translocation of AhR and Nrf2 into the nucleus, and the increase in mRNA levels of AhR-mediated CYP1A1 and Nrf2-mediated NQO1 confirms that TQ activates both the AhR and Nrf2 pathways.

Figure 4. TQ activates AhR and Nrf2.

(A) Caco-2 cells were treated with TQ (25 μM) 24 h after transfection with pGL4.43[luc2P/XRE/Hygro] vector and pGL4.74[hRluc/TK] vector. After 48 h of incubation, cells were lysed and analyzed by the luciferase reporter assay. TQ treatment increased luciferase activity, indicating increased XRE/AhR activity compared with that of vehicle control. ***p < 0.005.

(B) Caco-2 cells were treated with TQ (25 μM) 24 h after transfection with pGL4.43[luc2P/ARE/Hygro] vector and pGL4.74[hRluc/TK] vector. After 48 h of incubation, cells were lysed and analyzed by the luciferase reporter assay. TQ treatment increased luciferase activity, indicating increased ARE/Nrf2 activity compared with that of vehicle control. ***p < 0.005.

(C) Confocal immunofluorescence images of Ahr or Nrf2 staining (red color) in Caco-2 cells. The images showed that TQ treatment (6 h) increased AhR or Nrf2 migration into the nuclei (blue), indicating that TQ activates AhR and Nrf2. The dotted lines represent the optical level for the x-y plane and the x-z plane. White bar: 5 μm. These data are representative of several areas from n = 5.

(D and E) Protein lysates from vehicle (Veh) and TQ-treated Caco-2 cells were studied for AhR and its downstream target CYP1A1, along with Nrf2 and its downstream target NQO1, protein expression by western blot. TQ treatment (24 h) increased AhR, CYP1A1, Nrf2, and NQO1 protein levels (D). (E) The densitometry for (D) was quantified using ImageJ software. ACTB was used as a loading control. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005.

(F) The fold changes in mRNA levels of AhR target CYP1A1 and Nrf2 target NQO1 between Veh- and TQ-treated Caco-2 cells were determined by qRT-PCR. TQ treatment (24 h) increased the mRNA levels of both CYP1A1 and NQO1. The mRNA expression is relative to the GAPDH mRNA level. ****p < 0.001.

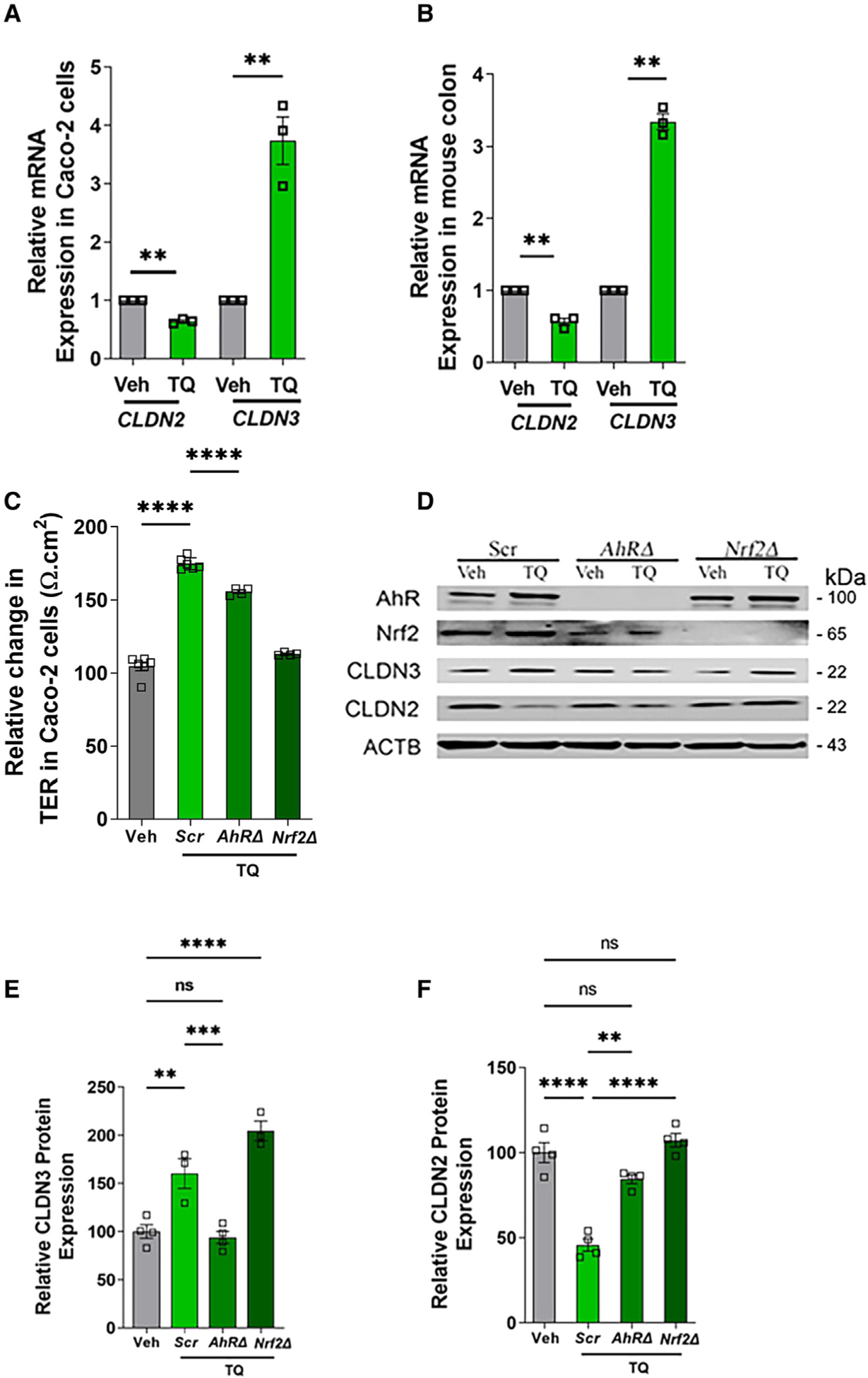

Effect of TQ on TJ gene expression

Since AhR and Nrf2 are transcriptional gene regulators, we studied the mRNA expression of CLDN2 and CLDN3 upon TQ treatment in Caco-2 cells (Figure 5A) and mouse colonic mucosa (Figure 5B). In both Caco-2 cells and mice colon, we observed a significant (p < 0.05) decrease in CLDN2 mRNA and increase in CLDN3 mRNA levels upon TQ treatment. These data indicate that TQ differentially regulates CLDN2 and CLDN3 expression at the transcript level.

Figure 5. TQ transcriptionally regulates CLDN2 and CLDN3 gene expression.

(A and B) The fold changes in mRNA levels of CLDN2 and CLDN3 between Veh- and TQ-treated Caco-2 cells (A) and mice colon (B) were determined by qRT-PCR upon TQ treatment. TQ treatment reduced the mRNA levels of CLDN2 and increased the mRNA levels of CLDN3 in both Caco-2 cells and mice colon. The mRNA expression is relative to the GAPDH mRNA level. **p < 0.01.

(C–F) Genetic deletion of AhR or Nrf2 impairs TQ-mediated enhancement of TJ barrier. Genetic deletion of AhR (AhRΔ) or Nrf2 (Nrf2Δ) in Caco-2 cells was achieved using CRISPR-Cas9-mediated genome editing technology.

(C) Non-target scrambled (Scr), AhRΔ, and Nrf2Δ Caco-2 cell monolayers grown on Transwells were treated with TQ (25 mM) or Veh for 48 h, and the effect of gene knockouts on TQ-mediated increase in TER was studied. The graph represents the percentage increase in TER upon TQ treatment compared with the corresponding Veh-treated control. TQ-mediated increase in TER in Scr cells was inhibited in Δ AhRD cells as well as Nrf2Δ cells. ****p < 0.001.

(D–F) Protein lysates from the Veh- and TQ-treated Scr, AhRΔ, and Nrf2Δ were assessed for AhR and Nrf2 deletion and CLDN3 and CLDN2 protein expression by western blot. Western blot shows the efficiency of CRISPR-Cas9-mediated knockout of AhR and Nrf2 in AhRΔ and Nrf2Δ Caco-2 cells (D). TQ treatment increased CLDN3 protein levels in non-target Scr cells and Nrf2Δ cells but not in AhRΔ cells. TQ-mediated reduction of CLDN2 in Scr cells was still observed in AhRΔ but was inhibited in Nrf2Δ cells. The densitometry for CLDN3 (E) and CLDN2 (F) from (B) was quantified using ImageJ software. ACTB was used as a loading control. **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001, ns, non-significant.

Effect of TQ on TJ proteins in AhRΔ and Nrf2Δ cells

To further study the role of AhR and Nrf2 on TQ-mediated enhancement of the TJ barrier, we knocked out AhR (AhRΔ) and Nrf2 (Nrf2Δ) individually in Caco-2 cells using CRISPR-Cas9-mediated gene editing. TQ treatment increased TER by ~74.8% in scrambled cells, whereas the TQ-mediated increase in TER was mildly reduced to ~55.6% in AhRΔ cells and further reduced to 20.2% in Nrf2Δ cells compared with the corresponding untreated controls (Figure 5C). Consistent with the TER results, western blot analysis revealed that the TQ-mediated reduction of CLDN2 protein levels was completely inhibited in Nrf2Δ cells and mildly inhibited in AhRΔ cells. On the other hand, a TQ-mediated increase in CLDN3 protein levels was inhibited in AhRΔ cells but not in Nrf2Δ cells (Figures 5D–5F). Western blot analysis also revealed the reduction of Nrf2 levels in AhRΔ cells, but the TQ-mediated increase in Nrf2 expression was still observed in AhRΔ cells. The mild to moderate inhibition of TQ-mediated increase in TER and reduction in CLDN2 protein levels in AhRΔ cells is expected to be due to the reduction of Nrf2 levels in AhRΔ cells. Thus, we speculated that AhR plays an important role in the TQ-mediated increase in CLDN3 expression, while Nrf2 may play an important role in the TQ-mediated reduction in CLDN2 expression and increase in TER.

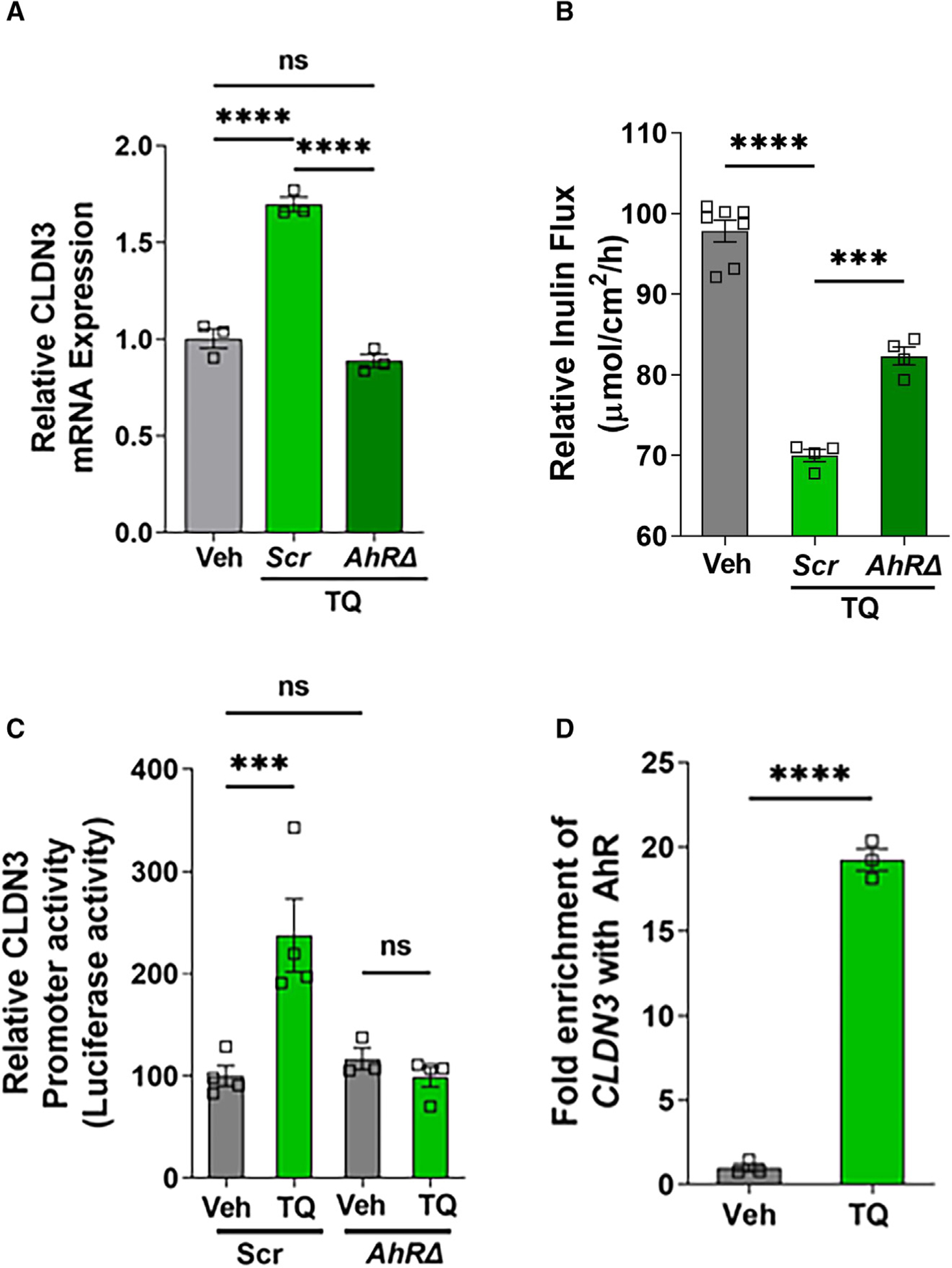

TQ increases CLDN3 expression via AhR-XRE interaction in the CLDN3 promoter

To further study the role of AhR on CLDN3, we analyzed the presence of XREs (GCGTG/CACGC) in the CLDN3 promoter region in both human as well as the mouse genome. We found the presence of two XRE regions at −426 and −365 in human CLDN3 promoter and one XRE region at −472 in mouse CLDN3 promoter regions. In contrast, XRE was not found in the CLDN2 promoter. The CLDN3 mRNA studies also showed that the increase in CLDN3 expression upon TQ treatment was inhibited in AhRD cells (Figure 6A). Consistent with the CLDN3 mRNA and protein levels, TQ-mediated reduction in large-molecule inulin flux was also inhibited in AhRΔ cells (Figure 6B). To study the role of XREs, we cloned human CLDN3 promoter in luciferase plasmid, transfected it into Caco-2 cells, and performed luciferase assay. Consistent with CLDN3 protein expression data, TQ treatment increased CLDN3 promoter activity, and this increase was inhibited in AhRΔ cells (Figure 6C). To further confirm the role of AhR on CLDN3 transcription, we performed chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) analysis to determine whether AhR binds to the CLDN3 promoter region. The ChIP analysis demonstrated a significant (p < 0.001) increase in the interaction of AhR with the CLDN3 promoter upon TQ treatment (Figure 6D). Collectively, increased CLDN3 mRNA expression and promoter activity upon TQ treatment, which was inhibited in the AhRΔ cells compared with non-target scrambled cells, and the increased interaction of AhR with CLDN3 promoter indicate that AhR directly activates CLDN3 expression upon TQ treatment via AhR-XRE interaction in the CLDN3 promoter.

Figure 6. AhR/XRE-mediated effect of TQ on CLDN3.

(A) The effect of TQ treatment on the mRNA levels of CLDN3 was studied in non-target Scr and AhRΔ Caco-2 cells. The graph represents the CLDN3 mRNA fold change to their corresponding Vehtreated control. TQ-mediated increases in CLDN3 mRNA levels were found to be inhibited in AhRΔ cells. ****p < 0.001, ns, non-significant.

(B)The large-molecule inulin flux in AhRΔ cells was compared with that in non-target Scr cells upon treatment with TQ. The reduction of inulin flux upon TQ treatment in Scr cells was found to be inhibited in AhRΔ cells. The graph represents the relative inulin flux upon TQ treatment to their corresponding Vehtreated control. ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001.

(C) Non-target Scr and AhRD Caco-2 cells were transfected with CLDN3 promoter cloned pGL4.26 [luc2P/minP/Hygro] vector and pGL4.74[hRluc/TK] vector. After 24 h incubation, the cells were treated with TQ (25 μM) or Veh for an additional 48 h, lysed, and analyzed by the luciferase reporter assay. TQ treatment increased luciferase activity (CLDN3 promoter activity) in Scr Caco-2 cells, but this increase was significantly inhibited in AhRΔ cells. ***p < 0.005, ns, non-significant.

(D) ChIP assays were performed using digestedchromatin from wild-type Caco-2 cells and an AhR antibody to interrogate binding to the CLDN3 promoter. ChIP-PCR amplification demonstrated the increased abundance of AhR binding to the promoter regions of CLDN3 after TQ treatment of Caco-2 cells. The graph represents the signal relative to the corresponding input. ****p < 0.001.

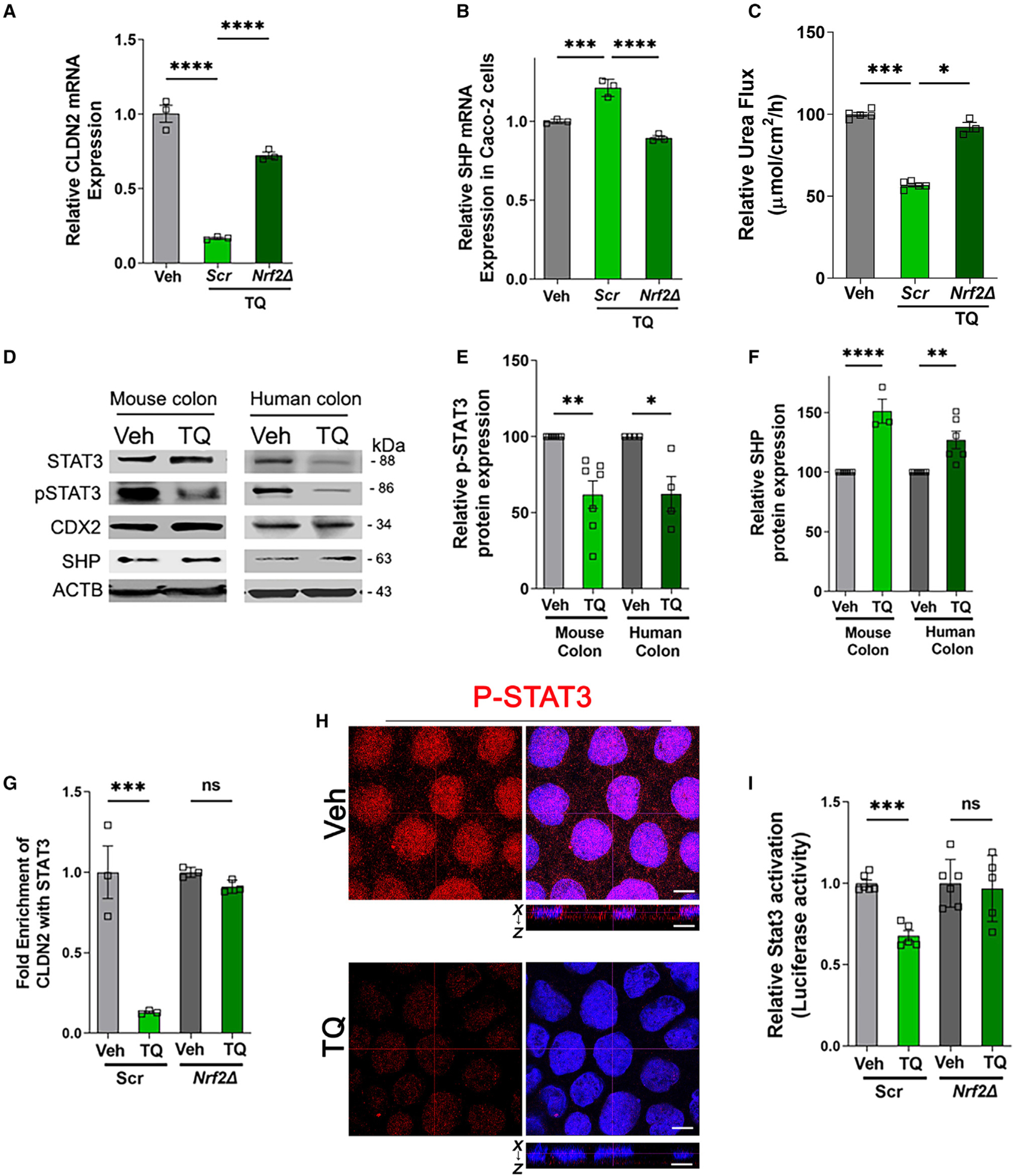

TQ reduces CLDN2 via Nrf2-SHP-mediated STAT3 inactivation

Next, to study the role of Nrf2 on CLDN2 expression, the CLDN2 promoter sequence was analyzed, which revealed that the CLDN2 promoter did not contain XREs or AREs. An earlier report44 showed the presence of caudal-type homeobox (CDX) protein, signal transducer and activator of transcription (STAT), and nuclear factor kB (NF-kB) subunit 1 binding sites in the CLDN2 promoter region. STAT3 is reported to regulate CLDN2 expression via a STAT binding site in its proximal promoter region.45 Moreover, STAT3 activation is reported to be controlled by Nrf2 via SHP (small heterodimer partner), which acts as a corepressor of STAT3 transcriptional activity.46 To further delve into TQ-mediated CLDN2 regulation, we studied mRNA expression of CLDN2 and SHP in non-target scrambled and Nrf2Δ cells. These mRNA studies showed that the TQ-mediated reduction of CLDN2 expression was inhibited in Nrf2Δ cells (Figure 7A). On the other hand, TQ increased SHP expression in scrambled cells and not in Nrf2Δ cells (Figure 7B). Consistent with the CLDN2 expression pattern and TER, the reduction in urea flux in scrambled cells upon TQ treatment was inhibited in Nrf2Δ cells (Figure 7C). To further understand the mechanism, we studied the effect of TQ on protein levels of SHP, STAT3, phospho-STAT3 (P-STAT3), and CDX2 in human and mouse colonic mucosa. Western blot analyses revealed a significant increase in Nrf2-regulated SHP protein levels and a significant reduction in P-STAT3 levels upon TQ treatment in both mouse and human colonic mucosa. CDX2 levels, on the other hand, showed no significant difference upon TQ treatment (Figures 7D–7F). To further study the role of STAT3 on CLDN2 transcription, we performed ChIP analysis to determine if STAT3 binds to the CLDN2 promoter. TQ treatment caused a significant reduction in STAT3 binding to the CLDN2 promoter (Figure 7G) in control cells but not in Nrf2Δ cells. Corroborating with the reduction of P-STAT3 levels, immunofluorescence analysis showed that TQ treatment reduced P-STAT3 staining and inhibited the nuclear localization of STAT3 (Figure 7H). Furthermore, TQ treatment also reduced luciferase activity in STAT3 homodimer luciferase reporter assay in scrambled (Scr) cells but not in NRF2Δ cells (Figure 7I). Collectively, these results demonstrate that TQ increases Nrf2-SHP levels, leading to reduced P-STAT3 levels, and reduces the interaction of STAT3 with the CLDN2 promoter, which in turn reduces CLDN2 levels. Hence, STAT3 plays a crucial role in TQ-/Nrf2-SHP-mediated transcriptional regulation of CLDN2 expression upon TQ treatment.

Figure 7. TQ reduces CLDN2 via STAT3-dependent mechanism.

(A) The effect of TQ treatment on the mRNA levels of CLDN2 was studied in Scr and Nrf2Δ Caco-2 cells. The graph represents the CLDN2 mRNA fold change upon TQ treatment compared with their corresponding Veh-treated control. TQ-mediated decrease in CLDN2 mRNA levels was found to be inhibited in Nrf2Δ cells. ****p < 0.001.

(B) The effect of TQ treatment on the mRNA levels of SHP was studied in Scr and Nrf2Δ Caco-2 cells. The graph represents the SHP mRNA fold change compared with the corresponding Veh-treated control. TQ-mediated increases in SHP mRNA levels were found to be inhibited in Nrf2Δ cells. ***p < 0.005, ****p < 0.001.

C) The small-molecule urea flux in Nrf2Δ cells was compared with that in non-target Scr cells upon treatment with TQ. The reduction of urea flux upon TQ treatment in Scr cells was found to be inhibited in Nrf2Δ cells. The graph represents the relative urea flux upon TQ treatment compared with their corresponding Veh-treated control. *p < 0.05, ***p < 0.005.

(D–F) Protein lysates from Veh- and TQ-treated mice colonic mucosa and human colonic mucosa were studied for STAT3, P-STAT3, CDX2, and SHP protein expression by western blot (D). TQ treatment (6 h) reduced P-STAT3 and increased SHP levels in both mouse and human colonic mucosa. No significant difference was observed in CDX2 protein levels upon TQ treatment (D). The densitometry for P-STAT3 (E) and SHP (F) from (A) were quantified using ImageJ software. ACTB was used as a loading control. *p < 0.05, **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.001.

(G) ChIP assays were performed using digested chromatin from Scr and Nrf2Δ Caco-2 cells and a STAT3 antibody on the CLDN2 promoter. ChIP-PCR amplification demonstrated the reduced abundance of STAT3 binding to the promoter regions of CLDN2 in Scr cells but not in Nrf2Δ cells. The graph represents the signal relative to the corresponding input. ***p < 0.005, ns, non-significant.

(H) Confocal images of P-STAT3 (red) and nuclei (blue) in Caco-2 cells. The images showed that TQ treatment (3 h) reduced P-STAT3 levels as well as its nucleartranslocation, indicating that TQ inhibits STAT3 activation. The dotted lines represent the optical level for the x-y and x-z planes. White bar: 5 μm. These data are representative of n = 5.

(I) Non-target Scr and NRF2Δ Caco-2 cells were cotransfected with pLminPLuc2P_RE5 (STAT3 homodimer luciferase reporter) vector and pGL4.74[hRluc/TK] vector. After 24 h incubation, the cells were treated with TQ (25 μM) or Veh for an additional 48 h, lysed, and analyzed by the luciferase reporter assay. TQ treatment decreased luciferase activity (STAT3 dimer) in Scr Caco-2 cells, but this decrease was not observed in the NRF2Δ cells. ***p < 0.001, ns, non-significant.

DISCUSSION

It is well established that a defective intestinal TJ barrier is a key pathogenic factor in intestinal inflammation. Thus, enforcement of the TJ barrier remains an important intervention tool in IBD.8,9,42 The composition of the TJs, in terms of channel-forming and barrier-forming proteins, is also altered in Crohn’s disease,47 ulcerative colitis,37,48,49 and microscopic colitis.50,51 In the present study, we show that TQ enhances the intestinal TJ barrier by increasing barrier-forming CLDN (CLDN3) and decreasing channel-forming CLDN (CLDN2) levels. Consequently, TQ also ameliorated experimental colitis in acute and chronic models of DSS colitis and TNBS and T cell transfer-mediated chronic colitis. Mechanistically, we showed that the TQ-mediated increase in CLDN3 is dependent on the AhR pathway, wherein AhR binds to the XRE present in the CLDN3 promoter and increases the protein expression. However, the reduction of CLDN2 is mediated via Nrf2-SHP-dependent STAT3 inactivation, leading to reduced interaction of STAT3 with CLDN2 promoter. Thus, the bifunctional action of TQ on AhR and Nrf2 pathway activation results in the enhancement of the intestinal TJ barrier, via diverse mechanisms.

TQ is a non-arylating quinone that consists of a benzoquinone central ring in its chemical structure and is widely reported to be non-toxic in nature.11,12 TQ treatment on Transwell-grown Caco-2 cell monolayers (in vitro), mice models (in vivo), and surgically resected human colonic tissues (ex vivo) consistently increased TER and reduced paracellular inulin and urea flux. The intestinal TJ protein analysis upon TQ treatment revealed that TQ differentially modulated CLDN expression by a significant and consistent increase in barrier-forming CLDN3 and a decrease in channel-forming CLDN2 in all three tested models. In recent studies, transgenic CLDN2 expression was shown to exacerbate, while genetic deletion of CLDN2 dampens, immune-mediated colitis in T cell transfer model.52 Several studies have shown that the inflamed intestinal mucosa in patients with active IBD has increased CLDN2 expression.47–49 On the other hand, the barrier-forming CLDN3 has reduced levels in IBD but is typically highly expressed in the colon, is involved in TJ barrier homeostasis, and is targeted by pro-inflammatory cytokines.53,54

As shown in previous reports,41,55,56 Ac and Ch DSS administration increased mouse colonic TJ paracellular permeability. TQ administration attenuated the Ac or Ch DSS-induced increase in colonic TJ permeability and ameliorated the severity of DSS colitis, as assessed by the loss of body weight, clinical disease activity index, and colonic histological inflammation scores. Similarly, TQ administration attenuated TNBS and T cell transfer chronic colitis in terms of colonic permeability as well as clinical and histologic score. TQ administration also preserved the loss of CLDN3 and an increase in CLDN2 in Ac and Ch DSS colitis. As increased epithelial permeability is an integral factor in experimental colitis, these data suggest that TQ-mediated TJ barrier modulation is an important factor in the amelioration of experimental colitis.

AhR has been shown to play several homeostatic roles including intestinal differentiation, stem cell homeostasis, and maintenance of gut microbiome.21,57 Meanwhile, AhR deficiency has been shown to cause increased susceptibility to experimental colitis.25,58 It has been previously shown that AhR activation by various agents is protective of the intestinal TJ barrier and beneficial against experimental colitis.26,28,29 The combined effect of CLDN2 reduction and increase in CLDN3 protein levels is specific to TQ compared with other tested AhR activators and is consistent with previous reports that modulation of AhR signaling has been ligand and tissue specific.59 Nrf2, on the other hand, is critical for managing oxidative stress and has pro-barrier and anti-inflammatory functions.30,60 The Nrf2 pathway is also known to be barrier protective in traumatic brain injury,61 chronic kidney disease models,62 and esophageal epithelium.31 Moreover, Nrf2 KO mice are reported to have increased susceptibility to oxidative damage and inflammation.63

Quinone-structured compounds are reported to be bifunctional and to activate AhR via covalently binding to the AhR protein as well as activate the Nrf2 pathway, owing to their oxidative and electrophilic nature.16 The effect of bifunctional compounds on the intestinal TJ barrier and their molecular mechanism has yet to be fully studied. In our study, the bifunctional nature of TQ in AhR and Nrf2 activation was evident in XRE- and ARE-luciferase reporter assays, specifically increased nuclear translocation of AhR and Nrf2, and increased protein and gene expression of CYP1A1 and NQO1, downstream target genes of AhR and Nrf2, respectively. The transcriptomic regulatory nature of AhR and Nrf2 was manifested by a TQ-mediated increase in CLDN3 and a reduction in CLDN2 mRNA levels in Caco-2 cells and mice colons. The dual activation of AhR and Nrf2 pathways and their effect on the intestinal TJ barrier have been reported for other compounds, such as coffee,64 prenylated xanthones from mangosteen,65 and Urolithin A, a microbial metabolite derived from fruit polyphenolics.28 The latter study revealed that Urolithin A-mediated activation of both AhR and Nrf2 independently affects CLDN4 protein levels.

The increase in TER upon TQ treatment was reduced in both AhRΔ and Nrf2Δ cells, but this effect was more dramatic in Nrf2Δ cells, suggesting that Nrf2 plays a more prominent role in TQ-mediated regulation of CLDN2-based cationic permeability. Accordingly, the TQ-mediated increase in CLDN3 mRNA and protein levels was completely inhibited in AhRΔ cells but not in Nrf2Δcells. In contrast, the TQ-mediated reduction of CLDN2 mRNA and protein levels was found to be completely inhibited in Nrf2Δ cells but only marginally so in AhRΔ cells. Thus, the TQ-mediated increase in CLDN3 is mediated via AhR, and the reduction of CLDN2 is majorly mediated via Nrf2 pathways. Furthermore, the partial inhibition of TQ-mediated increase in TER and the inhibition of inulin flux in AhRΔ cells are consistent with CLDN3 playing a direct role in the leak pathway and its indirect, CLDN2-dependent role in pore pathway.38 The inhibition of TQ-mediated increase in TER and the reduction in small-size probe flux seen in Nrf2Δ cells are consistent with the CLDN2-mediated small solute permeability and its inverse relation with TER.5,66

The transcriptional regulation of AhR on the CLDN3 promoter is attributed to the presence of XREs, which is conserved in humans and mice. The CLDN3 promoter activity as well as ChIP analysis confirmed that TQ-mediated increase in CLDN3 mRNA and protein expression is mediated via AhR-XRE interaction. On the other hand, the absence of AREs or XREs on the CLDN2 promoter and transcriptional regulation of TQ prompted us to study the transcriptional factor binding sites on the CLDN2 promoter. Earlier studies have reported the presence of CDX and STAT putative binding sites on the CLDN2 promoter (−1,026- to −1-bp upstream), which play an important role in regulating CLDN2 expression upon interleukin-6 (IL-6) and vitamin D treatment.44,67 Our results showed that TQ reduced P-STAT3 levels and decreased nuclear accumulation of STAT3, suggesting inhibition of STAT3 activation. Consistent with a previous report,68 we also observed a reduction in CLDN2 levels upon treatment with STAT3 inhibitor, stattic (data not shown). The interaction of STAT3 with the CLDN2 promoter was further studied with ChIP analysis, wherein we observed that TQ treatment decreased the abundance of STAT3 in the CLDN2 promoter. This result agrees with a previous report demonstrating that flavonoid treatment of lung adenocarcinoma A549 cells inhibited the interaction of STAT3 with CLDN2 promotor and reduced CLDN2 expression.45 Nrf2-mediated STAT3 inactivation is reported to occur via the Nrf2-SHP signaling cascade, which transcriptionally represses STAT3.46 Our results of TQ-induced increase in the levels of SHP in human and mice colonic mucosa suggest that TQ-mediated reduction of CLDN2 is mediated via the Nrf2-SHP signaling cascade. Though the crosstalk between AhR and Nrf2 pathway is reported to be sequential, with AhR playing a pivotal role, our data show that the observed effect of TQ on CLDN2 is partially due to the effect of AhR on the Nrf2 pathway. The increase in TQ-mediated Nrf2 protein in AhRΔ cells indicates that Nrf2 plays a pivotal role. The effect of TQ on CLDN3 is completely mediated via the Nrf2-independent AhR pathway.

Overall, we demonstrated the unique ability of TQ to enhance the basal intestinal TJ barrier as well as to protect against TJ barrier loss and inflammation in DSS and TNBS colitis. We also showed that healthy human colonic mucosa is responsive to TQ in terms of TJ barrier enhancement. Our data provide strong evidence that TQ modulates CLDN expression to reduce paracellular TJ permeability via AhR and Nrf2 pathways. Despite intense research, clinical application of AhR and Nrf2 activators in IBD is hampered by very complex, ligand- and tissue-specific effects of AhR and Nrf2 activation, toxicity considerations, and inadequate potency.59,69 Therefore, the possibility of regulating AhR and Nrf2 activity through an effective, non-toxic molecule is of great scientific and clinical interest.19 Based on several in vitro studies showing the antioxidant and membrane-protective effects of TQ,11,12,14 our findings of TQ-mediated promotion of cell membrane integrity, minimal in vivo accumulation with low yield conversion into non-toxic α-tocopherol levels,35 and clinical safety with oral administration15 indicate a potential for the safe therapeutic use of TQ. Our study indicates that TQ may offer a naturally occurring, non-toxic intervention for enhancement of the intestinal TJ barrier and adjunct therapeutics for intestinal inflammation.

Limitations of the study

Though we demonstrated the beneficial effect of TQ on the TJ barrier in multiple models including human colonic explants, the in vivo effect of TQ needs further investigation, particularly in terms of the therapeutic dosage and possible overdose. Human colon samples were not analyzed for any difference in permeability or response to TQ based on age and gender. Also, activation of AhR and Nrf2 pathways by TQ may have in vivo redundant or non-desirable effects, which were not investigated in this study. Further work is needed to find out the effect of TQ on junctional proteins not investigated in this study and the relative contribution of TQ-mediated enhancement of the TJ barrier in attenuating intestinal inflammation.

STAR★METHODS

KEY RESOURCES TABLE

| REAGENT or RESOURCE | SOURCE | IDENTIFIER |

|---|---|---|

| Antibodies | ||

| Anti-Claudin-2 | Abcam, Boston, MA | Cat# Ab53032; RRID:AB_869174 |

| Anti-Claudin-1 | Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA | Cat# 37–4900; RRID:AB_2533323 |

| Anti-Claudin-3 | Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA | Cat# 34– 1700; RRID:AB_86804 |

| Anti-Claudin-4 | Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA | Cat# PA5–34437; RRID:AB_2551789 |

| Anti-Occludin | ProteinTech, Rosemont, IL | Cat# 27260–1-AP; RRID:AB_2880820 |

| Anti-Tricellulin | ProteinTech, Rosemont, IL | Cat# 13515–1-AP; RRID:AB_2281702 |

| Anti-AhR | Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA | Cat# MA1–514; RRID:AB_2273723 |

| Anti-SHP/NROB2 | Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA | Cat# MA5–26790; RRID:AB_2724864 |

| Anti-CYP1A1/Cytochrome450 | Life Technologies, Carlsbad, CA | Cat# PA5–15212; RRID:AB_2088694 |

| Anti-NRF2 | ProteinTech, Rosemont, IL | Cat# 1639–1-AP |

| Anti-Cdx2 | ProteinTech, Rosemont, IL | Cat# 60243–1-lg |

| Anti-Stat-3 | ProteinTech, Rosemont, IL | Cat# 10253–2-AP; RRID:AB_2302876 |

| Anti-β-actin-HRP tagged | ProteinTech, Rosemont, IL | Cat# HRP- 60008; RRID:AB_2819183 |

| Anti-phospho-Tyr705-Stat-3 | Cell Signaling Technologies, Danvers, MA | Cat# 9145; RRID:AB_2491009 |

| Anti-CD45RB-FITC tagged | Biolegend, San Diego, CA | Cat# 103306; RRID:AB_313013 |

| Anti-CD4-APC tagged | Biolegend, San Diego, CA | Cat# 116014; RRID:AB_2563025 |

| Goat anti-mouse HRP tagged secondary antibody | Abcam, Boston, MA | Cat# AB205719; RRID:AB_2755049 |

| Goat anti-rabbit HRP tagged secondary antibody | Abcam, Boston, MA | Cat# AB97051; RRID:AB_10679369 |

| Goat anti-rabbit AF488 tagged IgG | Invitrogen, Waltham, MA | Cat# A11008; RRID:AB_143165 |

| Goat anti-mouse Cy3 tagged IgG | Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO | Cat# AP124C; RRID:AB_92459 |

| Bacterial and virus strains | ||

| E.coli DH5α | Invitrogen, Waltham, MA | Cat# 18-265-017 |

| Biological samples | ||

| Human colonic biopsies | Division of Colon and Rectal Surgery, Department of Surgery, Penn State College of Medicine. | N/A |

| Chemicals, peptides, and recombinant proteins | ||

| D-alpha-tocophreyl-quinone | Tokyo Chemical Industry (TCI), Portland, OR | Cat# T2283 |

| 14C Urea (Specific activity 56.5 mCi/mM) | Moravek Inc. Brea, CA | Cat# MC141 |

| 3H Inulin (Specific activity 100 mCi/g) | American Radiolabeled Chemicals (ARC) Inc. St.Louis, MO | Cat# ART0117 |

| Dulbecco′s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) | Gibco, Waltham, MA | Cat# 11965118 |

| Fetal bovine serum | R&D Systems, Minneapolis, MN | Cat# S11150H |

| Penicillin-Streptomycin | Gibco, Waltham, MA | Cat# 15140122 |

| Bovine Serum Albumin | Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO | Cat# A8412 |

| Dextran Sodium Sulfate (DSS) | MP Biomedicals, Santa Ana, CA, | Cat# 160110 |

| 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) | Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO | Cat# P2297 |

| RIPA buffer | Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO | Cat# R0278 |

| Protease inhibitor cocktail | Sigma Aldrich, St. Louis, MO | Cat# 11836170001 |

| Lamelli Buffer | Invitrogen, Waltham, MA | Cat# NP007 |

| SuperSignal West Pico PLUS kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA | Cat# 34580 |

| ProLong Gold antifade reagent | Invitrogen, Waltham, MA | Cat# P36931 |

| Lipofectamine 2000 | Invitrogen, Waltham, MA | Cat# 11668019 |

| Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay system | Promega, Madison, WI | Cat# E1960 |

| Trypsin protease | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA | Cat# 90–058 |

| XhoI | New England Biolabs (NEB), I pswich, MA | Cat# R0146L |

| HINDIII | New England Biolabs (NEB), Ipswich, MA | Cat# R0104L |

| Human Genomic DNA | Promega, Madison, WI | Cat# G304A |

| Critical commercial assays | ||

| BCA protein assay kit | Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA | Cat# 23225 |

| Direct-zol RNA Miniprep Plus Kit | ZYMO research, Irvine, CA | Cat# R2072 |

| iScript gDNA Clear cDNA Synthesis Kit | Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA | Cat# 1725034 |

| Simple ChIP kit | Cell Signaling Technology, Danvers, MA | Cat# 9003 |

| Experimental models: Cell lines | ||

| Human colonic epithelial Caco-2 cells | American Type Culture Collection (ATCC), Manassas, VA | Cat# HTB-37; RRID:CVCL_0025 |

| Experimental models: Organisms/strains | ||

| Acute and Chronic DSS Colitis in C57BL/6J | Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME | RRID:IMSR_JAX:000664 |

| mice | ||

| TNBS colitis in BALB/cJ mice | Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME | RRID:IMSR_JAX:000651 |

| T cell colitis in Rag−/− C57BL/6J mice | Jackson Laboratory, Bar Harbor, ME | RRID:IMSR_JAX:002216 |

| Oligonucleotides | ||

| 5′- AGATCTCGAGCGACGCGGCCA | Polygen synthesizer with | Penn State College of Medicine |

| CGCCCACCCT -3′ | Nensorb column purification | Macromolecular Synthesis Core |

| Forward primer for cloning CLDN3 | (RRID:SCR_01783) | |

| regulatory region | ||

| 5′- TTCGAAGCTTCGAAACTGGGCT | Polygen synthesizer with | Penn State College of Medicine |

| GGCCCTGGG -3′ | Nensorb column purification | Macromolecular Synthesis Core |

| Reverse primer for cloning CLDN3 | (RRID:SCR_01783) | |

| regulatory region | ||

| Recombinant DNA | ||

| Cas9 nuclease | Genecopoeia, Rockville, MD | Cat# CP-LVC9NU |

| PMD2.G | Addgene, Watertown, MA | RRID:Addgene_12259 |

| pPAX2 | Addgene, Watertown, MA | RRID:Addgene_12260 |

| pLminP_Luc2P_RE5 | Addgene, Watertown, MA | RRID:Addgene_90339 |

| pGL4.74 | Promega, Madison, WI | Cat# E6921 |

| luc2P/XRE pGL4.43 | Promega, Madison, WI | Cat #E4121 |

| luc2P/ARE pGL4.37 | Promega, Madison, WI | Cat# E3641 |

| pGL4.26 | Promega, Madison, WI | Cat #E8441 |

| pCRISPR- LVSG03 | Genecopoeia, Rockville, MD | Cat# CCPCTR01 |

| Software and algorithms | ||

| SigmaStat, Systat Software, | N/A | N/A |

| San Jose, CA | ||

| LAS X software | Leica Microsystems, Inc. Wood Dale, IL | N/A |

| Flow Jo V10 | BD Biosciences, Ashland OR | N/A |

| Other | ||

| single guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting the region 5′-CAAGTCGGTCTCTATGCCGCT-3′ of the AHR gene | Genecopoeia, Rockville, MD | Cat# HCP254627-LvSG03 |

| single guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting the region 5′- GGACTTGGAGCTGCCGCCGC -3′ of the NRF2 gene | Genecopoeia, Rockville, MD | Cat# HCP206580-LvSG03 |

RESOURCE AVAILABILITY

Lead contact

Any further information and resources and reagents requests may be directed to and will be fulfilled by the lead contact, Prashant Nighot (pnighot@pennstatehealth.psu.edu).

Materials availability

The unique reagents generated in this study are available from the lead contact with the appropriate institutional MTA agreements.

Data and code availability

The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

This paper does not report original code.

Any additional information required to reanalyze the data reported in this paper is available from the lead contact upon request.

EXPERIMENTAL MODEL AND STUDY PARTICIPANT DETAILS

Experimental methodologies used in the study were approved by the Institutional Animal Care and Use Committee of Pennsylvania State University College of Medicine (approval number 201800202). Wild-type male and female C57BL/6J mice (Stock No. 000664, Jackson Laboratory) were used for dextran sodium sulfate (DSS) (molecular mass, 36000–50000 Da; MP Biomedicals, 160110) studies, and wild-type male and female BALB/cJ mice (Stock No. 000651, Jackson Laboratory) were used for 2,4,6-trinitrobenzene sulfonic acid (TNBS) (Sigma Aldrich, P2297) studies. The mice were administered with TQ (50 mg/kg/day, oral gavage, dose based on previous pharmacological studies33–35). The experimental murine DSS colitis (acute and chronic DSS) models were established using standard protocols and as described previously.40,41,70 In the acute colitis model, 8–10-week old C57BL/6J mice received 3% DSS dissolved in autoclaved water for 7 days. TQ treatment was initiated two days before and continued throughout DSS treatment. In the chronic DSS colitis model, 8–10-week old C57BL/6J mice received three cycles of 5 days of 2% DSS in drinking water followed by 5 days of plain water. Mice were treated with TQ in the last cycle of water and DSS. The TNBS murine colitis model was established using standard protocols.70

In the TNBS colitis model, 8–10-week old BALB/cJ mice received daily gavaging of TQ starting two days before intracolonic TNBS administration (100 μL of 2.5% TNBS in ethanol) and continued throughout the experiment.

In the T cell transfer model for chronic colitis, T cells were isolated from WT mice, as described.71 Briefly, the leukocyte cell population from WT mice spleen was enriched using 80–40% Percoll gradient centrifugation. Effector and memory T cells were sorted as the CD45RB- FITC+, CD4-APC+ cells. Approximately 0.5 × 106 T cells were then injected into gender-matched recipient Rag–/– mice (JAX stock #002216). Mice were weighed twice per week and monitored for disease onset post-injection. Upon the appearance of diarrhea-like symptoms (~5 weeks post-injection), mice were randomly separated into control and test groups. The test groups of mice were administered with TQ for 7 days and control groups were administered with the vehicle. In all of the disease models, mouse body weights were monitored daily, and the disease activity index and histological grading of colitis lesions were conducted as described previously.56,70 The histological score consisted of 0, no evidence of inflammation; 1, low level of inflammation with scattered infiltrating mononuclear cells (1–2 foci); 2, moderate inflammation with multiple foci; 3, high level of inflammation with increased vascular density and marked wall thickening; and 4, maximal severity of inflammation with transmural leukocyte infiltration and loss of goblet cells.70 The experimental colitis data represent a minimum of two or more independent experiments with n ≥ 3 mice per group. No significant differences between male and female mice were seen in TQ effect on colonic permeability. The mice were housed under standard housing conditions with a 12-h light-dark cycle and ad lib standard chow diet and water supply.

Human tissue samples and treatment

The surgically resected, deidentified, human colon samples were obtained freshly from the Department of Surgery, Division of Colon and Rectal Surgery as per the protocols approved by the Institutional Review Board (STUDY00010256). Human colonic tissues were washed, the muscular layers were stripped, and the isolated mucosal epithelial tissues (0.5 cm × 0.5 cm) were incubated overnight flat on a gelatin sponge (Ethicon, Raritan, NJ, 1975) with the mucosal surface facing up, in supplemented DMEM, in the presence of vehicle or TQ.

METHOD DETAILS

Cell culture

Human colonic epithelial Caco-2 cells (ATCC) were maintained routinely in Dulbecco’s Modified Eagle’s Medium (DMEM) – High Glucose (Gibco; Cat. No. 11965118) supplemented with 10% heat-inactivated fetal bovine serum (R&D systems, S11150H) and antibiotics (Penicillin–Streptomycin; Gibco, 15140122) at 37°C with 5% CO2, 95% air. Caco-2 cell monolayers were grown on transwell plates, specifically over a 12 mm transwell with 0.4 μm pore polyester membrane inserts (Corning, 3460), and the media was changed every third day. The trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TER) of the transwell-grown cells was measured by an EVOM voltohmmeter and STX-2 electrode set (World Precision Instruments, Sarasota, FL), and monolayers with a TER of 450–500 Ω cm2, between postseeding day 15–18, were used for experiments.

Cell culture treatment

TQ treatment of cells in culture was performed as described previously.10 Briefly, cells in standard growth medium were treated with TQ (25 μM) for 48 h or indicated otherwise. TQ is first dissolved in ethanol and subsequently added to a 7.5% bovine serum albumin (BSA) solution (Sigma-Adrich, A8412). An equal volume of the vehicle control (100 μL ethanol and 900 μL 7.5% BSA mixture) in media was used where indicated.

Determination of Caco-2 paracellular flux

Caco-2 paracellular permeability was determined using the paracellular marker urea (14C, Mr = 60) and inulin (3H, Mr = 5000). The apical-to-basal flux rates of the paracellular markers were determined by adding them to the apical solution and radioactivity was measured in the basal solution at 30 min and 60 min using a scintillation counter, as described previously.72

Paracellular permeability of murine and human colon

The trans-epithelial resistance of the mice and human colonic tissues was measured by mounting the colonic tissue on 0.03-cm2-aperture Ussing chambers (Physiologic Instruments, Reno, NV). The mouse colons were unstripped while human colons were stripped of seromuscular layers. Trans-epithelial electrical resistance (TER, Ω cm2) was calculated from the spontaneous potential difference and short-circuit current. The paracellular permeability was assessed by the mucosal-to-serosal flux of [14C]-urea and [3H]-inulin as described previously.5

Western blot analysis for protein expression

Caco-2 monolayers were rinsed twice with ice-cold PBS and lysed using RIPA buffer (Sigma-Aldrich, R0278) containing protease inhibitors (Sigma-Aldrich, 11836170001). The mouse colonic mucosa or human colonic mucosa were washed with ice-cold PBS and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen soon after harvesting or treatment. The frozen tissues were resuspended in RIPA buffer containing protease inhibitors, minced, and sonicated to prepare tissue lysates. The cell/tissue lysates were centrifuged at 10,000 rpm for 10 min to remove debris, and the protein content of clarified supernatants was quantified using the BCA protein assay kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 23225). Laemmli gel loading buffer (Invitrogen, NP007) was added to the lysate, and the samples were boiled at 70°C for 10 min. An equal amount of protein was loaded on an SDS-PAGE gel, separated, and transferred to a nitrocellulose membrane. The membrane was incubated for 1 h in a blocking solution (5% non-fat dry milk in TBS-Tween 20 buffer), followed by incubation with the appropriate primary antibody in the blocking solution. After incubation with the primary antibody, the membrane was washed in TBS-0.1% Tween 20 buffer, then incubated in the appropriate secondary antibody and developed using SuperSignal West Pico PLUS kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, 34580). The densitometry analysis was performed using ImageJ software.73

Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy

Confocal immunofluorescence microscopy to detect claudins, AhR, and Nrf2 within Caco-2 cell monolayers or mouse colonic tissues was performed by standard methods. Caco-2 monolayers were washed twice with cold PBS and fixed with methanol for 10 min, while colon cryosections were fixed in acetone. The cell monolayers or cryosections were permeabilized with 0.1% Triton X-100 in PBS at room temperature for 5 min. The cell monolayers or cryosections were blocked in normal serum and labeled with primary antibodies in blocking solution overnight at 4°C. After PBS washes, the sections were incubated in Alexa Fluor 488, Cy-3, or Alexa Fluor-647- conjugated secondary antibodies (Invitrogen). ProLong Gold antifade reagent (Invitrogen, P36931) containing DAPI as a nuclear stain was used to mount the sections on glass slides. The slides were examined using a confocal fluorescence microscope, Leica SP8. Images were processed with LAS X software (Leica Microsystems).

RNA extraction and real-time PCR (PCR) analysis

Total RNA was extracted using Direct-zol RNA Miniprep Plus Kit (ZYMO research, R2072), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The DNase treatment and cDNA synthesis were performed using iScript gDNA Clear cDNA Synthesis Kit (Bio-Rad, 1725034) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Real-time quantitative PCR for the selected genes was performed using fam-tagged TaqMan Gene Expression Assay (Applied Biosystems) for CLDN2 (ID: Hs00265816_s1), CLDN3 (ID: Hs00265816_s1), CYP1A1 (ID: Hs01054796_g1), NQO1 (ID: Hs01045993_g1), and NROB2(SHP) (ID: Hs00222677_M1). Housekeeping gene GAPDH (Vic tagged; ID 4325792) was used as a control. The steady-state levels of the candidate genes were assessed from the cycle threshold (Ct) values of the candidate genes relative to the Ct values of corresponding endogenous controls (GAPDH), using the 2–ΔΔCt method.

Cloning of the 5′-regulatory region for the CLDN3 gene

To isolate the genomic DNA fragment that contained the 5′-regulatory region of the CLDN3 gene (GenBank gene ID: 1365 Chromosome 7, human reference genome (NCBI Reference Sequence: NC_000007.14)), PCR was performed using two gene-specific primers tagged with restriction digestion sites (forward, 5′- AGATCTCGAGCGACGCGGCCACGCCCACCCT −3′ with XhoI and reverse, 5′- TTCGAAGCTTCGAAACTGGGCTGGCCCTGGG −3′ with HindIII) and 100 ng of human genomic DNA (Promega, G304A). The amplified DNA product was separated on a 0.7% agarose gel and purified. The purified DNA was then cut with the restriction enzymes HindIII and XhoI (sequence encoded in the primers) and ligated into the pGL4.26 basic luciferase reporter plasmid (Promega), linearized with the same enzymes. The ligated Plasmid sequence was further verified by DNA sequencing.

Transient transfection and reporter gene assay

Caco-2 cells were cultured in 12-well tissue culture plates for 24 h before transfection at 60–80% confluency. For the measurement of either ARE or XRE activation by TQ, Caco-2 cells were transiently co-transfected with 1 mg/well XRE-luciferase (luc2P/XRE) expressing plasmid (pGL4.43, Promega) or ARE-luciferase (luc2P/ARE) expressing plasmid (pGL4.37, Promega) as stated above and 0.1 mg/ well Renilla luciferase (hRluc) reporting plasmid (pGL4.74) using Lipofectamine 2000 (11668019; Invitrogen). For CLDN3 promoter activity, 1 mg/well CLDN3 promoter in luciferase (luc2P) reporting plasmid (pGL4.26) (cloned as stated above) was co-transfected with 0.1 mg/well Renilla luciferase (hRluc) plasmid (pGL4.74). After 24 h of transfection, cells were treated with TQ for 48 h after which, the cells were lysed and assayed for luciferase activity using Dual-Luciferase Reporter Assay system (Promega, E1960) on GloMax 20/20 Luminometer (Promega). The activity of firefly luciferase was normalized against Renilla reporter activity (control) in the same samples. For assessing STAT3 activation we used the pLminP_Luc2P_RE5 plasmid (Addgene, 90339) and employed the same cotransfection methodology mentioned above.

Generation of CRISPR/Cas9 mediated AhR and Nrf2 gene knockout

The plasmid Cas9 nuclease CP-LVC9NU (Genecopoeia) was used individually with a single guide RNA (sgRNA) targeting the region CAAGTCGGTCTCTATGCCGCT of the AhR gene, GGACTTGGAGCTGCCGCCGC of the Nrf2 gene, and scrambled sgRNA for control in pCRISPR- LVSG03 (Genecopoeia), to generate respective lentiviral particles packaged in Lenti-X 293T cells using PMD2.G and pPAX2 (Addgene, 12259, 12260). The lentiviral particles obtained were used to transduce Caco-2 cells in the presence of polybrene and were selected in their respective antibiotic selection media to generate stable knockout Caco-2 cells.66 Gene knockouts were confirmed using Western blot analysis.

Chromatin immunoprecipitation (ChIP) assay

ChIP assays were performed with 1% formaldehyde to crosslink the protein to the DNA using the Simple ChIP kit (Cell Signaling Technology, 9003) as per the manufacturer’s protocol. Anti-STAT3 and anti-AhR antibodies were used to co-immunoprecipitate the DNA. The eluted DNA was amplified by quantitative PCR using the primer pairs for the CLDN2 promoter (forward: ACTTGAGTTAACACAGCCACCA and reverse: ACTTTGAACGTGGAGCCAAAAT) and CLDN3 promoter (forward: CGCGGC CACGCCCACCCT and reverse: ACTGGGCTGGCCCTGGG). Input chromatin was evaluated to confirm the same amounts of chromatins used in immunoprecipitation between groups.

QUANTIFICATION AND STATISTICAL ANALYSIS

Data are reported as means ± SE. Whenever needed, data were analyzed by using an ANOVA for repeated measures (SigmaStat, Systat Software, San Jose, CA). Tukey’s test was used for post hoc analysis between treatments following ANOVA (p < 0.05).

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Alpha-tocopherylquinone (TQ) enhances intestinal tight junction (TJ) barrier

TQ increases barrier-forming CLDN3 expression via AhR

TQ reduces channel-forming CLDN2 via Nrf-mediated STAT3 inactivation

TQ ameliorates experimental colitis

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the IBD and Colorectal Diseases Biobank, Confocal Microscopy, Animal Facility, and Flow Cytometry core (RRID: SCR_021134) at Penn State College of Medicine for their excellent technical assistance. This research was supported in part by the National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases grants DK100562 (P.N.) and DK114024 (P.N.), the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences R35ES028244 (G.P.), and a Crohn’s & Colitis Foundation Award 694583 (M.N.). The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of the funding agencies. The authors also acknowledge support from the Peter and Marshia Carlino Fund for IBD Research.

Footnotes

SUPPLEMENTAL INFORMATION

Supplemental information can be found online at https://doi.org/10.1016/j.celrep.2023.112705..

DECLARATION OF INTERESTS

The authors declare no competing interests.

INCLUSION AND DIVERSITY

We support the inclusive, diverse, and equitable conduct of research.

REFERENCES

- 1.Mandel LJ, Bacallao R, and Zampighi G (1993). Uncoupling of the molecular ‘fence’ and paracellular ‘gate’ functions in epithelial tight junctions. Nature 361, 552–555. 10.1038/361552a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Podolsky DK (1997). Healing the epithelium: solving the problem from two sides. J. Gastroenterol 32, 122–126. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Shen L, Weber CR, Raleigh DR, Yu D, and Turner JR (2011). Tight Junction Pore and Leak Pathways: A Dynamic Duo. Annu. Rev. Physiol 73, 283–309. 10.1146/annurev-physiol-012110-142150. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Turner JR (2009). Intestinal mucosal barrier function in health and disease. Nat. Rev. Immunol 9, 799–809. 10.1038/nri2653. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Nighot PK, Hu CAA, and Ma TY (2015). Autophagy enhances intestinal epithelial tight junction barrier function by targeting claudin-2 protein degradation. J. Biol. Chem 290, 7234–7246. 10.1074/jbc.M114.597492. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Coward S, Clement F, Benchimol EI, Bernstein CN, Avina-Zubieta JA, Bitton A, Carroll MW, Hazlewood G, Jacobson K, Jelinski S, et al. (2019). Past and Future Burden of Inflammatory Bowel Diseases Based on Modeling of Population-Based Data. Gastroenterology 156, 1345–1353.e4. 10.1053/j.gastro.2019.01.002. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ma TY, and Anderson JM (2006). Tight junction and intestinal barrier. In Textbook of Gastrointestinal Physiology, Johnson LR, ed. (Elsevier Health Sciences; ), pp. 1559–1594. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wyatt J, Vogelsang H, Hubl W, Waldhöer ¨ er T, and Lochs H (1993). Intestinal permeability and the prediction of relapse in Crohn’s disease. Lancet 341, 1437–1439. 10.1016/0140-6736(93)90882-h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Arnott ID, Kingstone K, and Ghosh S (2000). Abnormal intestinal permeability predicts relapse in inactive Crohn disease. Scand. J. Gastroenterol 35, 1163–1169. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Fajardo AM, MacKenzie DA, Olguin SL, Scariano JK, Rabinowitz I, and Thompson TA (2016). Antioxidants Abrogate Alpha-Tocopherylquinone-Mediated Down-Regulation of the Androgen Receptor in Androgen-Responsive Prostate Cancer Cells. PLoS One 11, e0151525. 10.1371/journal.pone.0151525. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Yang SG, Wang WY, Ling TJ, Feng Y, Du XT, Zhang X, Sun XX,Zhao M, Xue D, Yang Y, and Liu RT (2010). α-Tocopherol quinone inhibits β-amyloid aggregation and cytotoxicity, disaggregates preformed fibrils and decreases the production of reactive oxygen species, NO and inflammatory cytokines. Neurochem. Int 57, 914–922. 10.1016/j.neuint.2010.09.011. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Cornwell DG, Jones KH, Jiang Z, Lantry LE, Southwell-Keely P,Kohar I, and Thornton DE (1998). Cytotoxicity of tocopherols and their quinones in drug-sensitive and multidrug-resistant leukemia cells. Lipids 33, 295–301. 10.1007/s11745-998-0208-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Gant TW, Rao DN, Mason RP, and Cohen GM (1988). Redoxcycling and sulphydryl arylation; their relative importance in the mechanism of quinone cytotoxicity to isolated hepatocytes. Chem. Biol. Interact 65, 157–173. 10.1016/0009-2797(88)90052-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Wang X, Thomas B, Sachdeva R, Arterburn L, Frye L, Hatcher PG,Cornwell DG, and Ma J (2006). Mechanism of arylating quinone toxicity involving Michael adduct formation and induction of endoplasmic reticulum stress. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. USA 103, 3604–3609. 10.1073/pnas.0510962103. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lynch DR, Willi SM, Wilson RB, Cotticelli MG, Brigatti KW,Deutsch EC, Kucheruk O, Shrader W, Rioux P, Miller G, et al. (2012). A0001 in Friedreich ataxia: biochemical characterization and effects in a clinical trial. Mov. Disord 27, 1026–1033. 10.1002/mds.25058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Abiko Y, and Kumagai Y (2013). Interaction of Keap1 Modified by 2-tertButyl-1,4-benzoquinone with GSH: Evidence for S-Transarylation. Chem. Res. Toxicol 26, 1080–1087. 10.1021/tx400085h. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Miura T, Shinkai Y, Jiang HY, Iwamoto N, Sumi D, Taguchi K, Yamamoto M, Jinno H, Tanaka-Kagawa T, Cho AK, and Kumagai Y (2011). Initial response and cellular protection through the Keap1/Nrf2 system during the exposure of primary mouse hepatocytes to 1,2-naphthoquinone. Chem. Res. Toxicol 24, 559–567. 10.1021/tx100427p. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Motahari P, Sadeghizadeh M, Behmanesh M, Sabri S, and Zolghadr F (2015). Generation of stable ARE- driven reporter system for monitoring oxidative stress. Daru 23, 38. 10.1186/s40199-0150122-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Mulero-Navarro S, and Fernandez-Salguero PM (2016). New Trends inAryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Biology. Front. Cell Dev. Biol 4, 45. 10.3389/fcell.2016.00045. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mimura J, Ema M, Sogawa K, and Fujii-Kuriyama Y (1999). Identification of a novel mechanism of regulation of Ah (dioxin) receptor function. Genes Dev 13, 20–25. 10.1101/gad.13.1.20. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Metidji A, Omenetti S, Crotta S, Li Y, Nye E, Ross E, Li V, Maradana MR, Schiering C, and Stockinger B (2019). The Environmental Sensor AHR Protects from Inflammatory Damage by Maintaining Intestinal Stem Cell Homeostasis and Barrier Integrity. Immunity 50, 1542. 10.1016/j.immuni.2019.05.024. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Yang W, Yu T, Huang X, Bilotta AJ, Xu L, Lu Y, Sun J, Pan F,Zhou J, Zhang W, et al. (2020). Intestinal microbiota-derived short-chain fatty acids regulation of immune cell IL-22 production and gut immunity. Nat. Commun 11, 4457. 10.1038/s41467-020-18262-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Monteleone I, Rizzo A, Sarra M, Sica G, Sileri P, Biancone L, Mac-Donald TT, Pallone F, and Monteleone G (2011). Aryl hydrocarbon receptor-induced signals up-regulate IL-22 production and inhibit inflammation in the gastrointestinal tract. Gastroenterology 141, 237–48, 248.e1. 10.1053/j.gastro.2011.04.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Goettel JA, Gandhi R, Kenison JE, Yeste A, Murugaiyan G, Sambanthamoorthy S, Griffith AE, Patel B, Shouval DS, Weiner HL, et al. (2016). AHR Activation Is Protective against Colitis Driven by T Cells in Humanized Mice. Cell Rep 17, 1318–1329. 10.1016/j.celrep.2016.09.082. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Furumatsu K, Nishiumi S, Kawano Y, Ooi M, Yoshie T, Shiomi Y,Kutsumi H, Ashida H, Fujii-Kuriyama Y, Azuma T, and Yoshida M (2011). A role of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor in attenuation of colitis. Dig. Dis. Sci 56, 2532–2544. 10.1007/s10620-011-1643-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Ma Y, Wang Q, Yu K, Fan X, Xiao W, Cai Y, Xu P, Yu M, andYang H (2018). 6-Formylindolo(3,2-b)carbazole induced aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation prevents intestinal barrier dysfunction through regulation of claudin-2 expression. Chem. Biol. Interact 288, 83–90. 10.1016/j.cbi.2018.04.020. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Benson JM, and Shepherd DM (2011). Aryl hydrocarbon receptor activation by TCDD reduces inflammation associated with Crohn’s disease. Toxicol. Sci 120, 68–78. 10.1093/toxsci/kfq360. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Singh R, Chandrashekharappa S, Bodduluri SR, Baby BV, Hegde B, Kotla NG, Hiwale AA, Saiyed T, Patel P, Vijay-Kumar M, et al. (2019). Enhancement of the gut barrier integrity by a microbial metabolite through the Nrf2 pathway. Nat. Commun 10, 89. 10.1038/s41467-018-07859-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Yu M, Wang Q, Ma Y, Li L, Yu K, Zhang Z, Chen G, Li X, Xiao W,Xu P, and Yang H (2018). Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Activation Modulates Intestinal Epithelial Barrier Function by Maintaining Tight Junction Integrity. Int. J. Biol. Sci 14, 69–77. 10.7150/ijbs.22259. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Piotrowska M, Swierczynski M, Fichna J, and Piechota-Polanczyk A(2021). The Nrf2 in the pathophysiology of the intestine: Molecular mechanisms and therapeutic implications for inflammatory bowel diseases. Pharmacol. Res 163, 105243. 10.1016/j.phrs.2020.105243. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Chen H, Hu Y, Fang Y, Djukic Z, Yamamoto M, Shaheen NJ, Orlando RC, and Chen X (2014). Nrf2 deficiency impairs the barrier function of mouse oesophageal epithelium. Gut 63, 711–719. 10.1136/gutjnl-2012-303731. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Kobayashi A, Kang MI, Okawa H, Ohtsuji M, Zenke Y, Chiba T,Igarashi K, and Yamamoto M (2004). Oxidative stress sensor Keap1 functions as an adaptor for Cul3-based E3 ligase to regulate proteasomal degradation of Nrf2. Mol. Cell Biol 24, 7130–7139. 10.1128/mcb.24.16.7130-7139.2004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Bennet JD (1986). Use of alpha-tocopherylquinone in the treatment of ulcerative colitis. Gut 27, 695–697. 10.1136/gut.27.6.695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Palan PR, Woodall AL, Anderson PS, and Mikhail MS (2004). Alpha-tocopherol and alpha-tocopheryl quinone levels in cervical intraepithelial neoplasia and cervical cancer. Am. J. Obstet. Gynecol 190, 1407–1410. 10.1016/j.ajog.2004.01.067. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Moore AN, and Ingold KU (1997). alpha-Tocopheryl quinone is converted into vitamin E in man. Free Radic. Biol. Med 22, 931–934. 10.1016/s0891-5849(96)00276-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Van Itallie CM, Holmes J, Bridges A, Gookin JL, Coccaro MR,Proctor W, Colegio OR, and Anderson JM (2008). The density of small tight junction pores varies among cell types and is increased by expression of claudin-2. J. Cell Sci 121, 298–305. 10.1242/jcs.021485. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Krug SM, Bojarski C, Fromm A, Lee IM, Dames P, Richter JF,Turner JR, Fromm M, and Schulzke JD (2018). Tricellulin is regulated via interleukin-13-receptor a2, affects macromolecule uptake, and is decreased in ulcerative colitis. Mucosal Immunol 11, 345–356. 10.1038/mi.2017.52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Milatz S, Krug SM, Rosenthal R, Gunzel D, Müller D, Schulzke JD, Amasheh S, and Fromm M (2010). Claudin-3 acts as a sealing component of the tight junction for ions of either charge and uncharged solutes. Biochim. Biophys. Acta 1798, 2048–2057. 10.1016/j.bbamem.2010.07.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Günzel D, and Yu ASL (2013). Claudins and the modulation of tight junction permeability. Physiol. Rev 93, 525–569. 10.1152/physrev.00019.2012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Nighot M, Ganapathy AS, Saha K, Suchanec E, Castillo EF, Gregory A, Shapiro S, Ma T, and Nighot P (2021). Matrix Metalloproteinase MMP-12 promotes macrophage transmigration across intestinal epithelial tight junctions and increases severity of experimental colitis. J. Crohns Colitis 15, 1751–1765. 10.1093/ecco-jcc/jjab064. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Nighot P, Al-Sadi R, Rawat M, Guo S, Watterson DM, and Ma T(2015). Matrix metalloproteinase 9-induced increase in intestinal epithelial tight junction permeability contributes to the severity of experimental DSS colitis. Am. J. Physiol. Gastrointest. Liver Physiol 309, G988–G997. 10.1152/ajpgi.00256.2015. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arrieta MC, Madsen K, Doyle J, and Meddings J (2009). Reducingsmall intestinal permeability attenuates colitis in the IL10 gene-deficient mouse. Gut 58, 41–48. 10.1136/gut.2008.150888. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Madsen KL, Malfair D, Gray D, Doyle JS, Jewell LD, and Fedorak RN (1999). Interleukin-10 gene-deficient mice develop a primary intestinal permeability defect in response to enteric microflora. Inflamm. Bowel Dis 5, 262–270. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Suzuki T, Yoshinaga N, and Tanabe S (2011). Interleukin-6 (IL-6) regulates claudin-2 expression and tight junction permeability in intestinal epithelium. J. Biol. Chem 286, 31263–31271. 10.1074/jbc.M111.238147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Sonoki H, Tanimae A, Endo S, Matsunaga T, Furuta T, Ichihara K,and Ikari A (2017). Kaempherol and Luteolin Decrease Claudin-2 Expression Mediated by Inhibition of STAT3 in Lung Adenocarcinoma A549 Cells. Nutrients 9, 597. 10.3390/nu9060597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]