Abstract

Background:

Early-stage knee osteoarthritis (KOA) classification criteria will enable consistent identification and trial recruitment of individuals with knee OA at an earlier stage of disease, when interventions may be more effective. Towards this goal, we identified how early-stage KOA has been defined in the literature.

Methods:

We performed a scoping literature review in PubMed, EMBASE, Cochrane, and Web of Science including human studies where early-stage KOA was included as a study population or outcome. Extracted data included demographics, symptoms/history, examination, laboratory, imaging, performance-based measures, and gross inspection/histopathologic domains, and the components of composite early-stage KOA definitions.

Results:

Of 6142 articles identified, 211 were included in data synthesis. An early-stage KOA definition was used for study inclusion in 194 studies, to define study outcome in 11 studies, and in the context of new criteria development or validation in 6 studies. The element most often used to define early-stage KOA was Kellgren-Lawrence (KL) grade (151 studies, 72%), followed by symptoms (118 studies, 56%) and demographic characteristics (73 studies, 35%); 14 studies (6%) used previously developed early-stage KOA composite criteria. Among studies defining early-stage KOA radiographically, 52 studies defined early-stage KOA by KL grade alone; of these 52, 44 (85%) studies included individuals with KL grade 2 or higher in their definitions.

Conclusion:

Early-stage KOA is variably defined in the published literature. Most studies included KL grades of 2 or higher within their definitions, which reflects established or later-stage OA. These findings underscore the need to develop and validate classification criteria for early-stage KOA.

Keywords: Osteoarthritis, Scoping review, Classification criteria, Knee osteoarthritis, Symptomatic knee osteoarthritis, Early stage osteoarthritis

Introduction

Knee osteoarthritis (OA) is a highly prevalent disorder and leading cause of disability worldwide,1 with a burden projected to increase over the coming decades.2 The rising number of total knee replacements performed annually reflect both its healthcare burden and the lack of therapies available to prevent disease progression. Current pharmacological approaches for the treatment of knee OA focus on symptom control. To address the rising epidemic of knee OA, halting structural progression and symptomatic or functional consequences are important therapeutic goals and key deliverables for disease-modifying OA drug (DMOAD) development. To date, no DMOADs have been successfully developed, and approved by regulators, for use. A key factor limiting the success of DMOAD development may be the inclusion of individuals with established or late-stage OA, defined as at a minimum showing evidence of radiographic joint-space narrowing, a stage when pharmacologic intervention may be less successful.3

Identifying individuals with knee OA at an earlier stage of disease may allow provision of therapy, including rehabilitative and pharmacologic options, during a window of opportunity where interventions may be more likely to slow, halt or reverse disease progression. Critically, there is no established definition for early-stage knee OA (early-stage KOA), nor validated classification criteria to identify individuals for enrollment into clinical trials. Unlike diagnostic criteria, classification criteria should have high specificity, as they are standardized definitions that identify a relatively homogenous group of individuals with the condition of interest for research purposes.4 Diagnostic criteria, on the other hand, are used in clinical practice and should have adequate sensitivity to detect the majority of individuals who are likely to have the condition of interest. Published classification criteria for knee OA5 largely capture individuals with established or late-stage disease.6 While draft classification criteria for early-stage KOA have been proposed,7–9 they have not been sufficiently validated.

This is the initial phase of an Osteoarthritis Research Society International (OARSI)-endorsed initiative to develop classification criteria for early-stage KOA. The overall goal of this multi-phase initiative is to identify people early in the course of OA and to differentiate them from those with established or later stage OA. In order to identify candidate items to inform the development of classification criteria, the first step is to better understand how early-stage KOA has previously been defined. In this study we sought to identify the domains (e.g., symptoms or imaging features), and elements within these domains (e.g., joint space narrowing on x-ray) that have been used to define early-stage KOA to date in the literature.

Methods

We identified a scoping review as the most appropriate method of knowledge synthesis as we anticipated substantial heterogeneity of study samples and designs, exposures, and outcomes. A review protocol was developed, guided by the methodological framework proposed by Arksey and O’Malley.10 The review was conducted according to Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses Extension for Scoping Reviews (PRISMA-ScR).11

Eligibility criteria.

To identify the concept of early-stage KOA in published studies, we first developed intentionally broad inclusion criteria that could include both early-stage (i.e., meaning early in the course of OA as a disease and/or illness) and early-onset knee OA (i.e., onset or diagnosis of OA either early in the life course or early following joint injury). Although the focus of our review was on early-stage OA, these broad search criteria allowed for the capture of more potentially relevant studies at the outset.

We included human studies in which early-stage KOA was a study population or outcome of interest, without language exclusions (search strategy outlined below). A secondary objective was to identify existing early-stage KOA criteria. Thus, we included studies that aimed to develop and/or validate classification or diagnostic criteria for early-stage KOA under this umbrella. The initial search included full text manuscripts, conference abstracts and clinical trial entries, and basic, translational, intervention, observational, and qualitative study designs. For our initial search we did not exclude reviews, editorials, or commentaries, as their reference lists could be used to guide a hand search for further relevant studies. Case reports and non-human studies comprised our initial exclusion criteria.

Literature search strategy.

To identify relevant studies, a systematic literature search was designed, and implemented on March 14, 2022 by a medical librarian (DF) using both keywords and controlled vocabulary with Medical Subject Headings (MeSH) to search PubMed from the date of database inception. Searches in EMBASE, Web of Science, and Cochrane were performed on April 18, 2022 from the date of database inception. The full search strategies are available in the appendix (Supplemental Table 1).

Identification and selection of eligible studies.

We used Covidence software to assist with screening. The titles and abstracts of all references were screened independently by two reviewers and conflicts were resolved by a third reviewer (among a panel of 4 reviewers: JWL, LKK, AM, QW). Duplicates and studies not meeting inclusion criteria were excluded from further review. Full texts of included references were obtained and screened by two reviewers, with discrepancies resolved by a third reviewer.

Non-English language articles were translated using an online Google translator. At this stage we excluded reviews, commentaries, and editorials, but performed a hand search of their reference lists to identify additional studies that met our inclusion criteria. Due to the paucity of extracted data that would inform the goals of our review, we did not include clinical trial entries or conference abstracts without published manuscripts among our tabulated data for synthesized studies.

In the case of multiple reference identifiers arising from the same study, we included manuscripts with the most complete information and excluded others as duplicates. Some cohorts using a single early-stage KOA definition resulted in multiple non-duplicate publications. In such cases, in order to capture unique definitions of early-stage KOA used in the literature, one study (the first publication) was selected for extraction. If a cohort used different early-stage KOA definitions, each unique definition was included separately.

Data extraction process and data items.

For the eligible studies, we developed a standardized data extraction tool within Covidence. The extracted data for each study included meta-data (author, date, year of publication), study design, study objective, and geographic location of the study. For each study we determined whether early-stage KOA was used to determine participant eligibility, to define a study outcome, or in the context of development or validation of a new criteria set, as well as the setting (e.g., primary care, specialty care, community/general population) from which participants were selected.

For each study, we identified the specific elements of the definition of early-stage KOA used, within the following pre-specified domains: demographics, symptoms or history including standardized patient-reported outcome questionnaires (such as the Western Ontario and McMaster University Osteoarthritis Index [WOMAC]), physical examination, performance-based or objective measures, laboratory measures, imaging, and gross inspection or histopathology. We also identified whether the study definition for early-stage KOA included published composite OA criteria, such as those developed by Luyten, et al. for the classification of early-stage KOA in 2012 and 2018,7,8 or the 1986 American College of Rheumatology (ACR) classification criteria for knee OA5 (defined in Table 1). Additionally, we noted when a study’s early-stage KOA definition was based upon the inclusion criteria for Cohort Hip and Cohort Knee [CHECK]12 (also defined in Table 1). Data were extracted in duplicate by two reviewers, with a third reviewer or group discussion (among JWL, LKK, AM, QW, HFA) resolving any further discrepancies.

Table 1.

Composite knee OA criteria

| 1986 ACR classification criteria for knee OA | 1. Clinical and laboratory: Knee pain and at least 5 of 9: Age >50 years Stiffness <30 minutes Crepitus Bony tenderness Bony enlargement No palpable warmth ESR <40 mm/hour RF <1:40 Synovial fluid of OA (clear, viscous, WBC <2000/mm3) 2. Clinical and radiographic: Knee pain and at least 1 of 3: Age >50 years Stiffness <30 minutes Crepitus AND Osteophytes 3. Clinical Knee pain and at least 3 of 6: Age >50 years Stiffness <30 minutes Crepitus Bony tenderness Bony enlargement No palpable warmth |

| Luyten, et al. 2012 | Knee pain: At least two episodes of pain for 10 days in the last year Radiographs: KL grade 0 or 1 or 2 (osteophytes only) Arthroscopy, at least one of the following: ICRS grade I-IV in at least two compartments ICRS grade II-IV in one compartment with surrounding softening and swelling MRI, at least two of the following: Cartilage morphology: WORMS 3–6 or BLOKS grade 2 and 3 Meniscus: BLOKS grade 3 and 4 BMLs: WORMS 2 and 3 |

| Luyten, et al. 2018 | Patient-based questionnaire, KOOS score: 2 out of the 4 KOOS subscales need to score “positive” (≤85%) Pain Symptoms, stiffness Function, daily living Knee-related quality of life Clinical examination, with at least one of the following: Joint line tenderness Crepitus X-rays: KL grade 0–1 standing, weight bearing, with at least two projections |

| Cohort Hip and Cohort Knee (CHECK) inclusion criteria | At initial presentation to general practitioner: 45–65 years old with pain and/or stiffness of the knee and/or hip ≤6 months of symptoms |

Abbreviations: OA, osteoarthritis; ESR, erythrocyte sedimentation rate; RF, rheumatoid factor; WBC, white blood cell; KL, Kellgren-Lawrence; ICRS, International Cartilage Repair Society; KOOS, Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score; WORMS, Whole Organ Magnetic Resonance Imaging Score; BLOKS, Boston Leeds Osteoarthritis Knee Score

Data synthesis.

We summarized study characteristics and tabulated the number and proportion of studies that included each domain and each element within domains in their definition of early-stage KOA, making note of whether included domains or elements had been incorporated in a composite measure.

Results

Study selection.

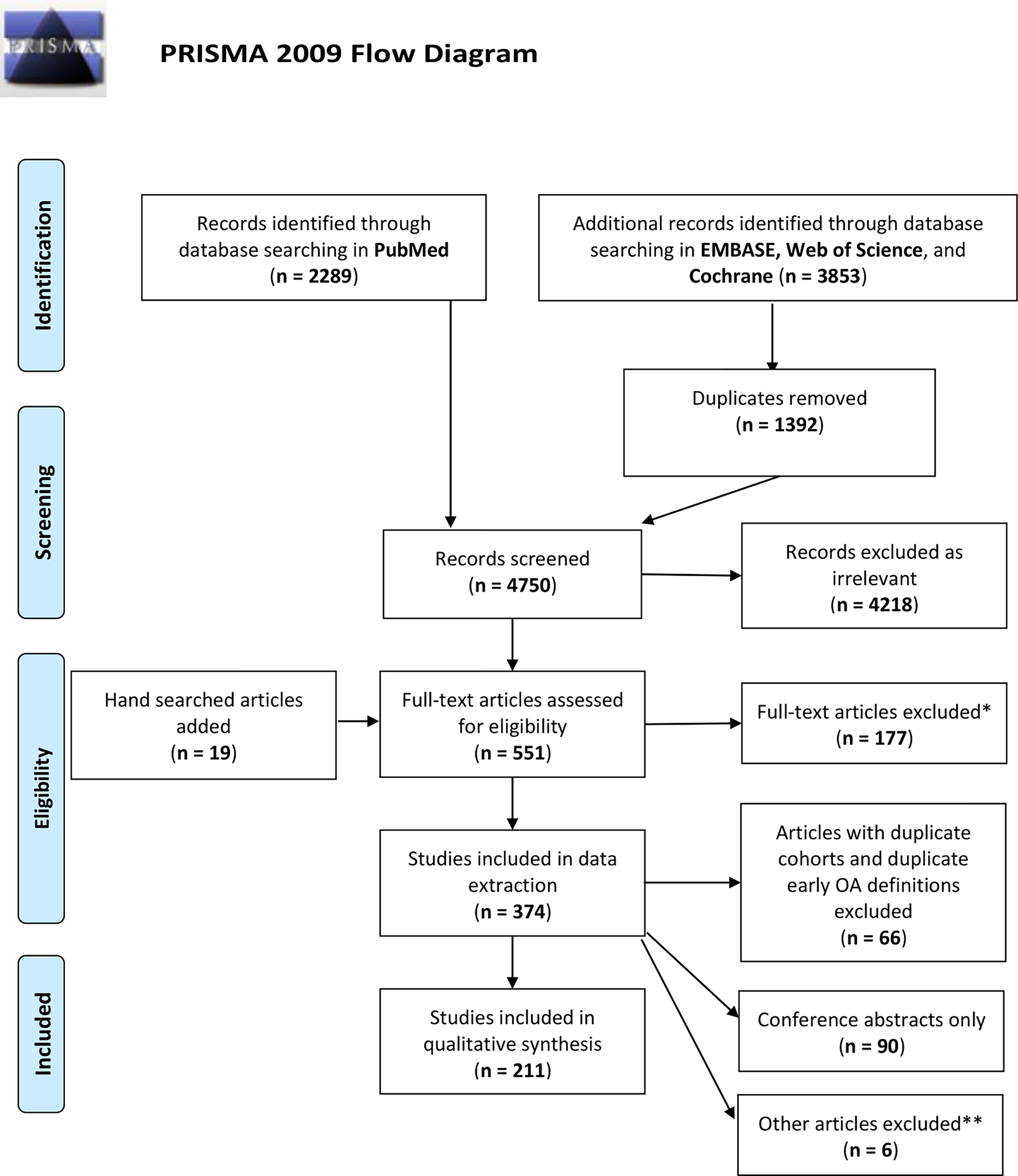

A total of 6142 citations were identified from searches of electronic databases (Figure 1). Following the removal of 1392 duplicates, we screened 4750 citations and removed 4218. An additional 19 studies were identified by manual search of a previously published review,13 which resulted in 551 articles that were reviewed for full text retrieval and eligibility assessment. A further 177 studies were excluded for the following reasons: excluded study designs (including reviews/commentaries/editorials), 52; wrong patient population, 38; duplicates, 26; “early OA” within the study did not refer to being early in the course of OA, 25; clinical trial without available abstract/manuscript, 23; no clear indication of early-stage KOA population, 9; and no full text available, 4.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study inclusion for the scoping review.

*Exclusion reasons: Wrong study design, 52; Wrong patient population, 38; Duplicate, 26; Early OA did not refer to being early in the course of OA, 25; Clinical trial without abstract/manuscript, 23; No clear indication of Early-stage KOA population, 9; No full text available, 4

**Exclusion reasons: Duplicate, 9; No clear indication of early-stage KOA population, 2

The remaining 374 studies were considered eligible for data extraction. During this phase we excluded 7 further studies (5 duplicates, 2 without clear indication of an early OA population), identified 90 studies as conference abstracts only, and 66 studies of duplicate cohorts that did not use unique early-stage KOA definitions. Due to the limited extracted data within the conference abstracts, we chose to further exclude these from our final analysis. This resulted in 211 primary studies eligible for qualitative analysis (Supplemental Table 2).

Characteristics of included studies.

Characteristics of the 211 studies included in the scoping review qualitative analysis are listed in Table 2. These included 115 observational, 58 interventional, 31 translational/basic science studies, 3 qualitative, and 4 with other designs. Most were performed in Asia (n=71), Europe (n=66), or North America (n=36). All were published after 1990. The plurality of studies (90, 43%) included patients or participants selected from a specialty clinic (including orthopedic surgery, rheumatology, and sports medicine) or a medical center, while 33 studies drew participants from the community. Only 5 studies primarily drew patients from a primary care setting. Fifty-three studies did not have available data on clinical setting. In 194 studies, an early-stage KOA definition was used as study inclusion, in 11 studies to define study outcome, and in 6 studies in the context of the development or validation of new criteria.7–9,14–16

Table 2.

Characteristics of included studies for synthesis, n=211

| Study characteristics | |

|---|---|

| Study design, n studies | Observational: 115 Cross-sectional: 64 Cohort: 42 Case-control: 7 Case series: 2 Interventional trial: 58 Basic science or translational: 31 Qualitative: 3 Other: 4 |

| Geographic site(s), n studies | Asia: 71 Europe: 66 North America: 36 South America: 6 Australia/NZ: 6 Africa: 1 Middle East: 2 Multiple: 2 NA: 21 |

| Setting from which participants were selected* | Specialty clinic: 90 Community/general population: 33 Medical center, secondary or tertiary: 29 Primary care: 5 Outpatient, unspecified: 2 Not specified/not available: 53 |

| How was early OA definition used within the study | Study inclusion or exposure: 194 Outcome definition: 11 Development of diagnostic or classification criteria: 5 Validation of diagnostic or classification criteria: 1 |

1 study used two cohorts that recruited from different populations

NA = not available

Definitions of Early-stage KOA (Supplemental Table 2).

Of the 211 studies in the main qualitative synthesis, 52 (25%) defined early-stage KOA d by Kellgren and Lawrence (KL) radiographic OA grade alone; of these, 44 (85%) included KL grade 2. Some studies used established composite criteria to define early-stage KOA: the 1986 ACR knee OA classification criteria (32 studies),5 previously developed early knee OA criteria sets by Luyten, et al. in 2012 (6 studies) and 2018 (8 studies). 7,8

Domains and elements used in defining Early-stage KOA.

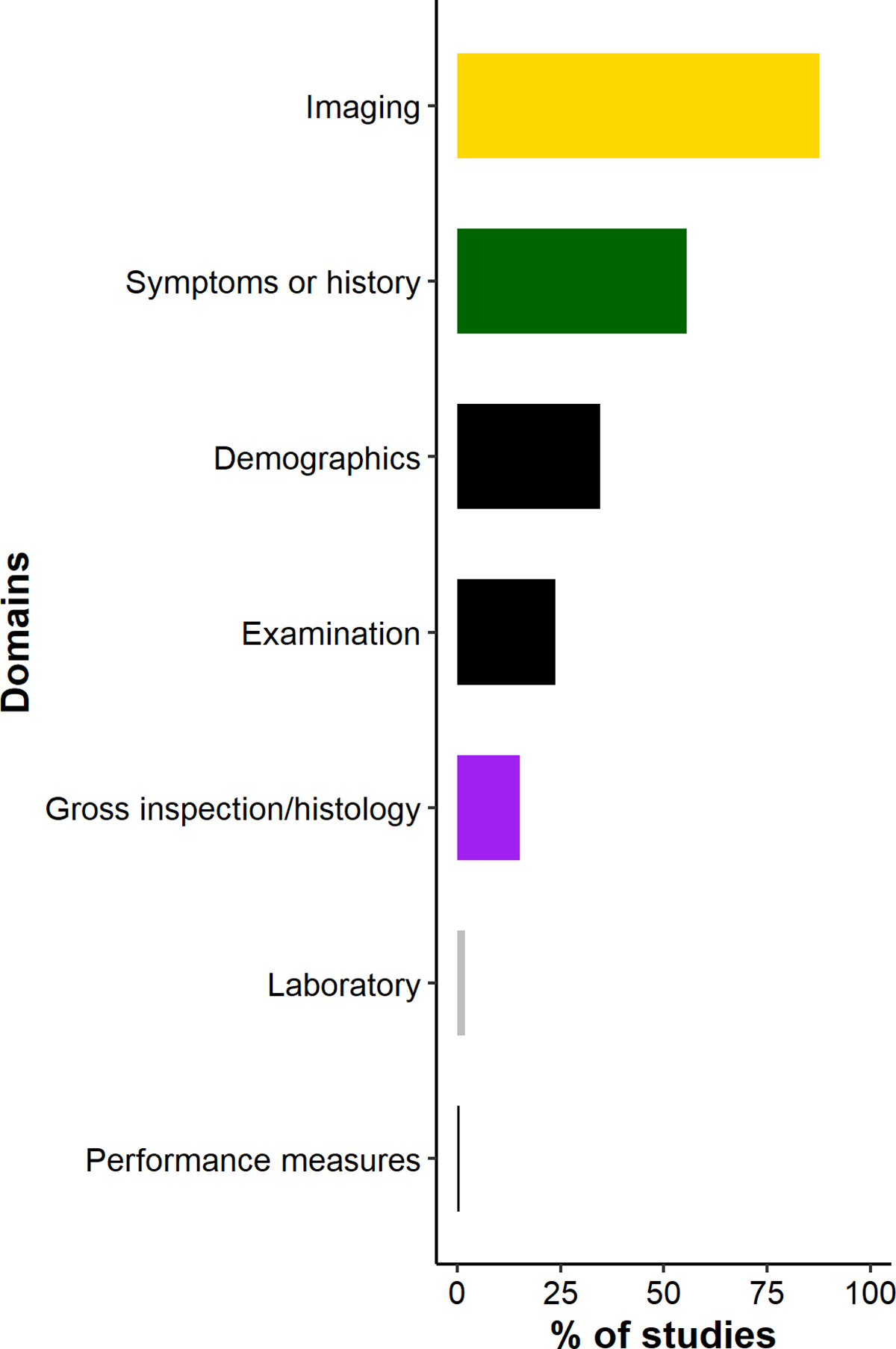

All elements (categorized by domain) included in Early-stage KOA definitions are included in Figure 2 and Supplemental Table 3.

Figure 2.

Domains included in study definitions of early-stage KOA for n=211 synthesized studies

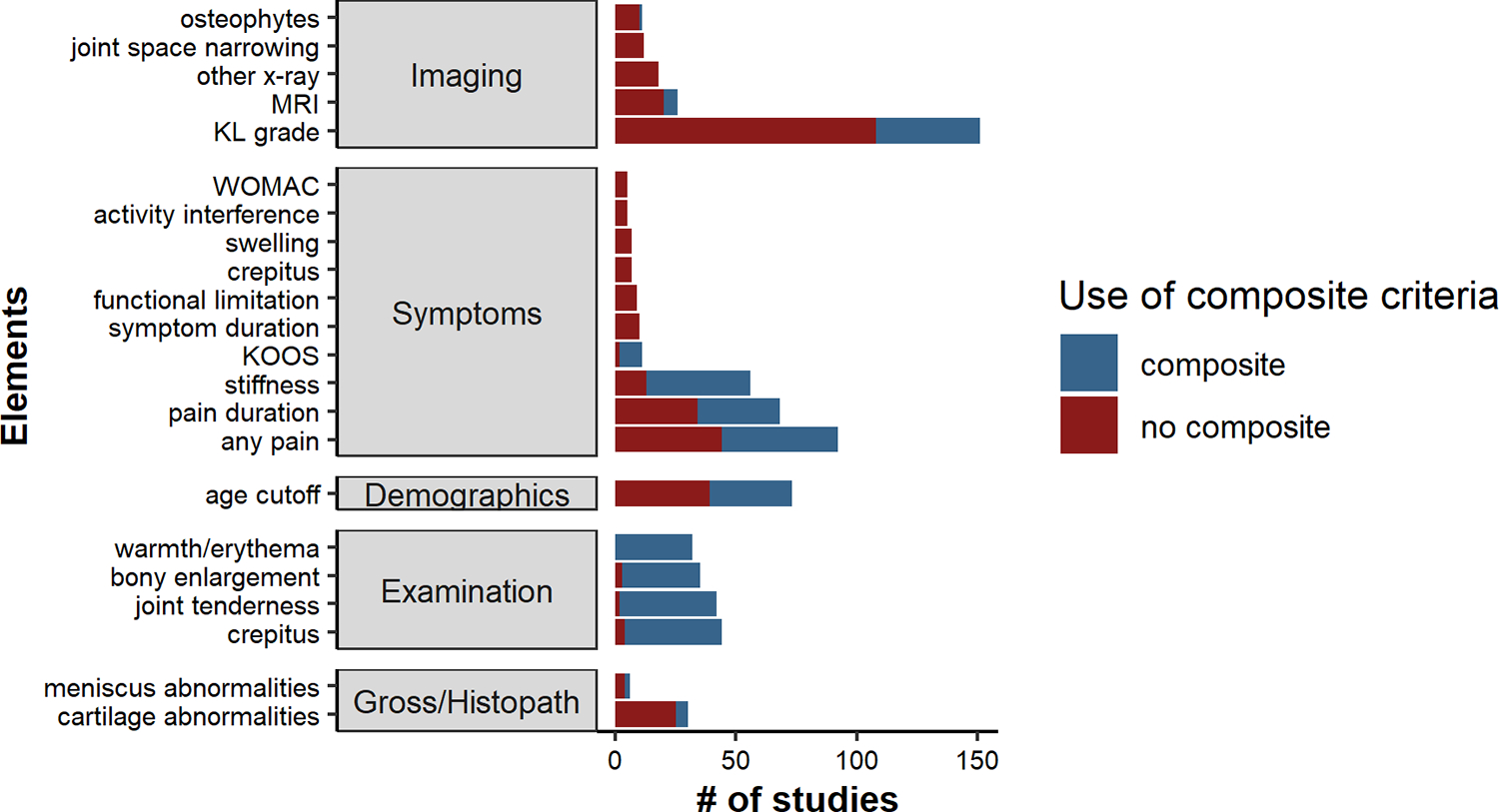

Elements within the imaging domain were included in 185 studies (88%) (14 studies based on the 2012 or 2018 Luyten, et al. criteria sets), with radiographic KL grade as the most common element (n=151). Of studies including KL grade in its early-stage KOA definition, the most commonly used KL grade combinations were grades 1–2 (n=59), followed by 0–2 (n=29) and 0–1 (n=17). Overall, 112 (53%) studies included KL grade 2 in their early-stage KOA definition and 16 (8%) studies included individuals with a KL grade 3 knee. For the 7 studies that included the Ahlbäck classification criteria for radiographic OA17 in their early-stage KOA definition, all included stage 1, which is the presence of joint space narrowing. Other imaging elements included knee MRI (n=26; with features including cartilage damage, meniscal degeneration, and presence of bone marrow lesions), joint space narrowing/joint space width (n=12), and osteophytes on x-ray (n=10).

Of the 211 included studies, 118 studies (56%) explicitly included symptoms or history; these included 32 studies with early-stage KOA definitions that were based on the ACR criteria, 8 on the Luyten, et al. 2018 criteria, and 2 on CHECK cohort inclusion criteria (Figure 3). The most common symptoms were presence of any knee pain (n=92), stiffness (n=56), pain duration (n=34), and symptom duration (n=10). Most of the studies that specified a cutoff for stiffness duration used <30 minutes per the ACR criteria. Of those specifying knee pain duration, cutoffs ranged from 1–12 months. Of the studies including symptom duration, cutoffs ranged from 3–60 months. Fifteen studies included other standardized patient-reported outcomes with the Knee Injury and Osteoarthritis Outcome Score (KOOS) questionnaire as the most common, n=10 (of these, 8 from the Luyten, et al. 2018 criteria set).

Figure 3.

Most common elements, within domains, included in study definitions of early-stage KOA for n=211 synthesized studies

Elements represented if used in ≥5 studies.

The presence of an element was a potential inclusion criterion for early-stage KOA within a study.

Composite OA criteria included the 1986 ACR OA classification criteria, the early OA classification criteria developed by Luyten, et al. (2012 and 2018), and the inclusion criteria for the Cohort Hip and Cohort Knee (CHECK).

Early-stage KOA definitions included elements within the demographic domain in 73 studies (35%). All 73 included an age cutoff; 32 of these studies were based on ACR criteria and two others utilized the CHECK inclusion criteria12). Of studies including an age cutoff, the most common cutoff was <40 years (23 studies). Four studies included BMI cut-offs (lower limit of BMI cutoffs: 25, 30, 35, and 40 kg/m2).

Elements within the physical examination domain were included in 50 studies (24%) (32 studies included the ACR criteria, 8 studies included the 2018 Luyten, et al. criteria set), with crepitus (n=44), joint line tenderness (n=42), bony enlargement (n=35), and warmth/erythema (n=32) most common.

Elements within the domain gross inspection/histopathologic examination were included in 32 studies (15%) (6 studies based on the 2012 Luyten, et al. criteria set). Cartilage (n=30) and meniscal abnormalities (n=6) were the most common elements.

Only 4 studies included laboratory values (erythrocyte sedimentation rate as the most common), and 1 study included physical performance-based or objective measures (isokinetic measures of muscle strength).

The most three most common domain combinations that were included in early-stage KOA definitions were Imaging + Symptoms/history (106 studies), Imaging + Demographics (66 studies), and Symptoms/history + Demographics (62 studies).

Discussion

Although the term “early-stage KOA” has been widely used for study inclusion or as a study outcome in the published literature, this scoping review highlights important considerations. We found substantial variability in how early-stage KOA has been defined across studies, and that many definitions of early-stage KOA have included presence of advanced structural changes and/or symptoms reflective of established or late-stage OA. The definition of early-stage KOA also varied by study design and primary objective, pointing to the broad interest in applying early-stage KOA criteria in OA research studies. This variability in definitions hinders comparisons across studies and demands clarification regarding the concept of early-stage KOA classification criteria, including what is meant by “early-stage” in each study. The majority of existing definitions used in the literature are not able to distinguish early-stage KOA from established or later-stage OA, a primary focus of the present OARSI initiative.

The goal of classification criteria development is to produce a highly specific definition to enable identification of a well-defined and relatively homogenous sample of individuals with the condition of interest for enrollment into research studies, including clinical trials. In the case of early-stage KOA classification criteria, a primary goal is to identify individuals early in the course of OA with symptoms or functional limitations before potentially irreversible damage/disability occurs. While it may be appropriate for diagnostic considerations in clinical practice to include early-stage disease in addition to later or more advanced disease, this differs from the goal in research settings, where discrimination of early-stage KOA from later stage disease is the aim for programs targeting therapy to earlier stage disease that may be more amenable to interventions. Further, the goals of the present classification criteria development initiative differ from the goals of many studies included in our scoping review, which ranged from describing the characteristics of an early-stage KOA population to development of prediction models for KOA progression.

Since its introduction, the most commonly used classification criteria for knee OA are the 1986 ACR criteria, which were developed in patients with longstanding knee OA and in the setting of a rheumatology clinic, where a main purpose was excluding rheumatoid arthritis.5 Individuals that fulfill the clinical and radiological ACR criteria already have irreversible joint damage, making these criteria inappropriate for use in studies where identification of an early-stage KOA population is desired.18

Several prior classification and diagnostic criteria have been proposed for early-stage KOA. In 2012, new classification criteria were proposed by the European Society for Sports Traumatology, Knee Surgery and Arthroscopy by including knee symptoms such as pain or stiffness associated with degenerative changes detected by MRI or arthroscopy, therefore making these criteria more targeted towards a patient population seen by specialists rather than general practitioners.7 A set of criteria for early symptomatic knee OA was proposed by the Italian Society for Rheumatology in 2017, with a focus on exclusion criteria, risk factors and symptoms, for the purpose of referral from primary care to rheumatology practices or specialty centers9 However, the goals of most of these prior criteria differ from the current goal of the OARSI initiative, which is to differentiate early-stage KOA from established or later stage OA. Another set of classification criteria was proposed by Luyten, et al. in 2018 to identify symptomatic patients with early-stage knee OA, with a focus on use in primary care.8 These criteria relied on broadly applicable, simple, patient-based assessments and clinical examination in the absence (or near-absence) of radiological abnormalities. The Criteria for the Early Diagnosis of Osteoarthritis (CREDO) group recently proposed early diagnostic criteria intended for use in the primary care setting.15 The criteria from Luyten, et al (2018) and CREDO have been validated and refined, but only to a limited extent.14,16 Only a small minority of studies identified in our review employed proposed definitions for early-stage KOA, likely due to the recency of their publication.

Beyond the use of defined composite OA criteria, the majority (72%, 151/211) of studies evaluated in our scoping review included radiographic KL grade as an element in their early-stage KOA definition. The rationale for relying on radiographic KL grade to define early-stage KOA includes the simplicity of applying criteria for a clinical study or trial, especially as x-rays are easily obtained in both the clinical and research settings. The majority of the studies that included KL grade as an element included KL grade 2 (77%, 116/151), which was originally defined as presence of definite osteophyte with possible joint-space narrowing. The inclusion of possible joint space narrowing will include individuals with knee OA who already have more established structural joint damage such as likely cartilage loss,19 which could reflect disease that may be outside of the window of opportunity for certain effective disease-modifying treatment. The need to capture early-stage KOA while excluding more established OA is a novel goal for the new early-stage KOA classification criteria, because the intended use of these criteria in research will be to focus on early-stage KOA rather than expanding the definition of knee OA. In addition, some studies identified in our review that included KL grading in their early-stage KOA definitions explicitly excluded KL grade 0. This may highlight the lack of clarity regarding how best to define knees with the complete absence of plain radiographic abnormalities indicative of OA. Finally, those with radiographic OA (disease) may not necessarily have the illness of OA. Subsequent steps in classification criteria development will focus on OA as both disease and illness.

Only 56% (118/211) of studies required patients/participants to have knee symptoms. Even fewer (24%) included physical examination features and only one study included objective performance-based functional measures. However, the aim of therapeutic intervention trials, is to enroll individuals with clinical (i.e., symptomatic) manifestations. Due to the known symptom-structure discordance in OA, it may in this context not be appropriate for imaging features alone to define early-stage KOA. Thus, newly proposed early-stage KOA classification criteria should consider other elements from the clinical presentation, including symptoms. How best to identify individuals with early-stage KOA and differentiate them from those with established OA remains challenging. For example, in the earliest stages of OA, radiographs may be normal (KL 0). The addition of other elements, including symptoms, physical examination, and functional limitations identified using objective performance-based measures, must be examined for utility in discriminating early-stage KOA from other causes of knee pain and from later stages of knee OA. To date, data on whether the frequency, intensity, type, and duration of symptoms can differentiate early-stage KOA from established or late-stage OA are lacking. There is also a paucity of data on what symptomatic features occur in the early stages of OA. Development of clinically feasible modalities to measure intra-articular inflammatory markers associated with OA could, as an example, provide insight on disease status in patients with minimal structural or functional changes.

Strengths of our study included an extensive scoping review of the literature including different types of study designs, settings and languages. Studies were screened in duplicate, involving multiple reviewers with expertise in OA research. Several limitations should be acknowledged. First, despite our screening strategy and search within four databases, we may have missed studies that included a definition for early-stage KOA, including if they were not explicitly labeled as such. Some studies had vague definitions for early-stage KOA, or definitions that overlapped with general study inclusion criteria. While we utilized multiple reviewers for data extraction, some items may have been misidentified as being part of the study’s intended definition for early-stage KOA. Second, quantitative analysis of our data was limited by the lack of details available in the majority of studies. Third, we did not assess the methodological quality of included studies using validated risk of bias tools. However, in keeping with best practices for conducting scoping reviews,10 the purpose of this study was to synthesize the breadth of literature regarding the concept of early-stage KOA in preparation for the rigorous development of consensus classification criteria for early-stage KOA.

In summary, we sought to identify how early-stage KOA has been defined in the literature to date and found that most studies have defined early-stage KOA as early in structural progression, when assessed radiographically. Non-imaging elements that were included in published early-stage KOA definitions, including symptoms, demographics, and examination variables, were often based on existing composite criteria for knee OA. Considering these published studies, there does not appear to be a consensus for an early-stage KOA definition that identifies those at a stage prior to presence of significant radiographically-defined structural change. Given the need to identify individuals with early-stage KOA at a sufficiently early stage for enrollment into disease-modifying OA clinical trials, before the onset of structural changes and symptoms of established or late-stage knee OA, our findings underscore the need for evidence-supported, validated classification criteria for early-stage KOA. This scoping review has identified items to consider in the development of new early-stage KOA classification criteria. It informs next steps, including being incorporated in a Delphi exercise to generate a comprehensive list of variables that may discriminate early-stage KOA from established or later stage OA and non-OA causes of knee pain.

Supplementary Material

Footnotes

COMPETING INTERESTS

JWL reports a Pfizer research grant completed in 2021, unrelated to this work.

CTA reports grant funding from the Canadian Institutes of Health Research, Arthritis Society of Canada, and grant funding and consulting/honoraria from Abbvie, Fresenius Kabi, Novartis, and Pfizer.

IKH reports a research grant from Pfizer/Lilly, and consulting fees from Abbvie, Novartis and GSK, all outside of the submitted work.

SL reports consulting/honoraria from Arthro Therapeutics AB, Sweden and participation on a DSMB board for AstraZeneca.

All other authors report no competing interests.

Contributor Information

Jean W. Liew, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA.

Lauren K. King, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Canada.

Armaghan Mahmoudian, Department of Clinical Sciences Lund, Orthopedics, Clinical Epidemiology Unit, Lund University, Lund, Sweden and Department of Movement Sciences and Health, University of West Florida, FL, USA..

Qiuke Wang, Department of General Practice, Erasmus MC University Medical Center Rotterdam, the Netherlands..

Hayden F. Atkinson, Faculty of Health Sciences, University of Western Ontario, London, Canada.

David B. Flynn, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA.

C. Thomas Appleton, Department of Medicine; Department of Physiology and Pharmacology Schulich School of Medicine and Dentistry, The University of Western Ontario, London, Canada; Western Bone and Joint Institute..

Martin Englund, Department of Clinical Sciences Lund, Orthopedics, Clinical Epidemiology Unit, Lund University, Lund, Sweden..

Ida K. Haugen, Center for Treatment of Rheumatic and Musculoskeletal Diseases (REMEDY), Diakonhjemmet Hospital, Oslo, Norway.

L. Stefan Lohmander, Department of Clinical Sciences Lund, Orthopedics, Lund University, Lund, Sweden..

Jos Runhaar, Department of General Practice, Erasmus MC University Medical Center Rotterdam, the Netherlands..

Tuhina Neogi, Boston University School of Medicine, Boston, MA, USA..

Gillian Hawker, Department of Medicine, University of Toronto, Canada..

REFERENCES

- 1.GBD2019. Global burden of 369 diseases and injuries in 204 countries and territories, 1990–2019: a systematic analysis for the Global Burden of Disease Study 2019. The Lancet 2020;396:1204–1222. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(20)30925-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Kurtz S, Ong K, Lau E, et al. Projections of primary and revision hip and knee arthroplasty in the United States from 2005 to 2030. J Bone Joint Surg Am 2007;89:780–5. doi: 10.2106/JBJS.F.00222. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Mahmoudian A, Lohmander LS, Mobasheri A, Englund M, Luyten FP. Early-stage symptomatic osteoarthritis of the knee — time for action. Nat Rev Rheumatol 2021;17:621–632. doi: 10.1038/s41584-021-00673-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Aggarwal R, Ringold S, Khanna D, et al. Distinctions between diagnostic and classification criteria? Arthritis Care Res 2015;67:891–897. doi: 10.1002/acr.22583 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Altman R, Asch E, Bloch D, et al. Development of criteria for the classification and reporting of osteoarthritis. Arthritis Rheum 1986;29:1039–1049. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Peat G, Greig J, Wood L, Wilkie R, Thomas E, Croft P. Diagnostic discordance: We cannot agree when to call knee pain “osteoarthritis.” Fam Pract 2005;22:96–102. doi: 10.1093/fampra/cmh702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Luyten FP, Denti M, Filardo G, Kon E, Engebretsen L. Definition and classification of early osteoarthritis of the knee. Knee Surgery, Sports Traumatology, Arthroscopy 2012;20:401–406. doi: 10.1007/s00167-011-1743-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Luyten FP, Bierma-Zeinstra S, Dell’Accio F, et al. Toward classification criteria for early osteoarthritis of the knee. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2018;47:457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2017.08.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Migliore A, Scirè CA, Carmona L, et al. The challenge of the definition of early symptomatic knee osteoarthritis: a proposal of criteria and red flags from an international initiative promoted by the Italian Society for Rheumatology Rheumatol Int 2017;37:1237–1238. doi: 10.1007/s00296-017-3742-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Arksey H, O’Malley L. Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology: Theory and Practice 2005;8:19–32. doi: 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): Checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med 2018;169:467–473. doi: 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Wesseling J, Dekker J, van den Berg WB, et al. CHECK (Cohort Hip and Cohort Knee): Similarities and differences with the Osteoarthritis Initiative. Ann Rheum Dis 2009;68:1413–1419. doi: 10.1136/ard.2008.096164 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Iolascon G, Gimigliano F, Moretti A, et al. Early osteoarthritis: How to define, diagnose, and manage. A systematic review. Eur Geriatr Med 2017;8:383–396. doi: 10.1016/j.eurger.2017.07.008 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mahmoudian A, Lohmander LS, Jafari H, Luyten FP. Towards classification criteria for early-stage knee osteoarthritis: A population-based study to enrich for progressors. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2021;51:285–291. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2020.11.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Runhaar J, Kloppenburg M, Boers M, Bijlsma JWJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA. Towards developing diagnostic criteria for early knee osteoarthritis: Data from the CHECK study. Rheumatology 2021;60:2448–2455. doi: 10.1093/rheumatology/keaa643 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Wang Q, Runhaar J, Kloppenburg M, Boers M, Bijlsma JWJ, Bierma-Zeinstra SMA. Diagnosis for early stage knee osteoarthritis: probability stratification, internal and external validation; data from the CHECK and OAI cohorts. Semin Arthritis Rheum 2022;55. doi: 10.1016/j.semarthrit.2022.152007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ahlbäck S Osteoarthrosis of the knee: a radiographic investigation. Acta Radiol Stockholm 1968;suppl 277:7–72. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Skou ST, Koes BW, Grønne DT, Young J, Roos EM. Comparison of three sets of clinical classification criteria for knee osteoarthritis: a cross-sectional study of 13,459 patients treated in primary care. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2020;28:167–172. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2019.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Roemer FW, Felson DT, Stefanik JJ, et al. Heterogeneity of cartilage damage in Kellgren and Lawrence grade 2 and 3 knees: the MOST study. Osteoarthritis Cartilage 2022;30:714–723. doi: 10.1016/j.joca.2022.02.614 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.