Abstract

Altered DNA methylation (DNAm) might be a biological intermediary in the pathway from smoking to cancer. In this study, we investigated the contribution of differential blood DNAm to explain the association between smoking and lung cancer incidence. Blood DNAm was measured in 2321 Strong Heart Study (SHS) participants. Incident lung cancer was assessed as time to event diagnoses. We conducted mediation analysis, including validation using DNAm and paired gene expression data from the Framingham Heart Study (FHS). In the SHS, current versus never smoking and pack-years single-mediator models showed, respectively, 29 and 21 differentially methylated positions (DMPs) for lung cancer (14 of 20 available, and five of 14 available, replicated, respectively, in FHS) with statistically significant mediated effects. In FHS, replicated DMPs showed gene expression downregulation largely in trans, and were related to biological pathways in cancer. The multimediator model identified that DMPs annotated to the genes AHRR and IER3 jointly explained a substantial proportion of lung cancer. Thus, the association of smoking with lung cancer was partly explained by differences in baseline blood DNAm at few relevant sites. Experimental studies are needed to confirm the biological role of identified eQTMs and to evaluate potential implications for early detection and control of lung cancer.

Keywords: Smoking, DNA methylation, lung cancer incidence, Strong Heart Study, Framingham Heart Study

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Differential patterns in blood DNA methylation (DNAm) are associated with lung cancer, the main cause of cancer death worldwide,1-5 suggesting that DNAm changes may play a key role in tumorigenesis.6 Epigenetic signatures associated with smoking are robust across ethnically diverse populations,7,8 and support that DNAm might play a role in the biological pathway linking smoking to lung cancer.9-17 However, studies investigating the role of DNAm in smoking-related lung cancer are unclear.18 Hypomethylation of CpGs annotated to smoking-related genes including AHRR and F2RL3 has been associated with lung cancer.15 An in-vitro study showed that smoking-induced epigenetic changes in the KRAS oncogene might lead to sensitization of bronchial epithelial cells for malignant transformation.19 However, two Mendelian randomization studies have provided little evidence in favor of a causal role of DNAm in lung cancer.20,21 In most studies of smoking, DNAm and cancer are limited by the lack of time to incident (i.e. newly diagnosed) cancer or the lack of formal mediation analyses.

In this study, we investigated whether the association of current and cumulative smoking with lung cancer risk might be explained by differences in human blood DNAm. We used data from the Strong Heart Study (SHS), a cohort of US Native Americans22 (discovery population), and the Framingham Heart Study (FHS) (replication population). In addition, we conducted additional validation of the findings using whole blood gene expression in a subset of FHS participants, as well as a bioinformatic pathway enrichment analysis to assess potential biological implication of the findings. Finally, we extended a previously published multimediator model23 to the survival setting to jointly assess individual mediated effects in a way that can account for correlations across DNAm sites, which enabled the evaluation of the most impactful DMPs potentially driving lung cancer risk.

Methods

Discovery study population: The Strong Heart Study

The SHS is a prospective cohort study of American Indian adults.24 Blood DNAm was measured at baseline (1989-1991) in 2,351 participants using Illumina’s MethylationEPIC BeadChip (850K). After preprocessing, 2325 individuals were left for DNAm data analysis (Supplementary Figure 1). For this study, one participant that withdrew consent and 89 additional participants with missing cigarette pack-years data were excluded, leaving 2235 individuals and 788,368 CpG sites for analyses. Specific details regarding participant inclusion, clinical variable collection and microarray DNAm measurements can be found in the Supplementary Methods.

Lung cancer incidence was assessed by self-report during interviews, death certificates and/or chart reviews and pathology reports if available (Supplementary Table 1). We calculated the time-to-event from the date of baseline examination (1989-1991) to the date of the cancer diagnosis or 31 December 2017, whichever occurred first.

Replication study population: The Framingham Heart Study

The FHS is a population-based study that started in 1948. DNAm from whole blood was measured in 2,648 participants who participated in the 8th visit (2005-2008) and 1,522 Generation III participants who participated in the second visit (2006-2009) using the Illumina Infinium HumanMethylation 450K BeadChip22 (Supplementary Methods). Gene expression from paired whole blood RNA was sequenced at >×30 depth of coverage using RNA-SeQC v1.1.9. according to TOPMed RNA-Seq pipeline v225 (Supplementary Methods).

Lung cancer incidence was assessed by interviews, death certificates, and/or chart reviews that included pathology reports, and crosschecked with official medical records whenever possible (Supplementary Table 1). We calculated the time-to-event from the date of baseline examination (2005-2008 or 2006-2009) to the date of the cancer diagnosis or December 31, 2016, whichever occurred first.

Statistical Methods

Differential Methylation Analysis by Iterative Sure Independence Screening (ISIS).

We first conducted a screening among the CpG sites that were associated with smoking in previous work in the SHS (303 CpGs in total),22 by using a Cox ISIS coupled with elastic-net26 (ISIS-ENET, as conducted by the extended SIS R package, which is publicly available for download at https://github.com/statcodes/SIS), to select CpG sites associated with time to lung cancer. Models accounted for potential confounding due to age, sex, BMI, study center (Arizona, Oklahoma, or North Dakota and South Dakota) cell counts (CD8T, CD4T, NK, B cells and monocytes) and five genetic PCs.27. Former smoking has been associated with cancer mortality in the SHS.28 Consequently, we kept the regression coefficient for former smoking status in the models (i.e. two indicator variables were simultaneously introduced in the regression models, for mutually exclusive former and current smoking status categories, with the never smoking category being the reference). Former smoking indicator was thus considered an adjustment variable. Cumulative smoking models were additionally adjusted for current smoking status using an indicator variable.

Mediation analysis based on Aalen additive hazards models.

We calculated natural direct, indirect and total effects based on the product of coefficients method for survival mediation analysis using Aalen additive hazards models (see Supplementary Methods).29 Please note that these effects do not imply causal associations, but refer to associations in the context of an epidemiological study following the standard wording in mediation analysis. Mediated effects were reported as differences in cancer cases comparing current to never smokers, or differences in cancer cases per a 10 cigarette pack-years increase, attributable to smoking-related blood DNAm differences per 100,000 person-years. The corresponding 95 % confidence intervals were calculated using a resampling method.30

Expression quantitative trait methylation.

The eQTM analysis was performed fitting a linear model for DMPs that were significant in the single-DMP mediation analysis both in the SHS and the FHS. For a detailed description of RNASeq pre-processing methods see Supplementary Methods (Supplementary Material). The final regression model included batch effect-corrected expression as the dependent variable, batch effect-corrected DNAm as an independent variable, and adjustment for sex, age, predicted blood cell fraction, five expression PCs and 10 DNAm PCs, which accounted for population.

Multimediator model.

In presence of correlated mediators, traditional mediation analysis methods might lead to individual relative mediated effects that add up to more than 100 %, which suggests that some pathways are overlapping and the joint and individual effects remain unidentifiable. To address this limitation, we extended the multimediate algorithm,23 which uses the counterfactual multiple mediation framework, to the survival data setting based on the Aalen additive hazards model. The R code is available in the Github repository (https://github.com/AllanJe/multimediate). Our novel multimediate algorithm23 is able to identify individual mediated effects of several mediators simultaneously while taking into account correlated mediators. In this setting, relative mediated effects could never add up to more than 100%. We fitted the multimediate algorithm for current versus never smokers and for heavy versus light smokers (i.e. cigarette pack-years < 20 versus >= 20). For the FHS, the multimediate algorithm was only fitted for current versus never smokers due to the smaller cigarette pack-years values. Mediated effects with p-values lower than 0.05 were considered statistically significant.

The joint mediated effect for a given set of correlated mediators as calculated by the traditional “difference of coefficients” method31 and the joint indirect effect as calculated by the multimediator algorithm should yield similar results. We thus ran post-hoc sensitivity analyses using the traditional “difference of coefficients method” to provide additional support to our newly developed multi-mediator model.

Enrichment analysis.

We conducted a KEGG enrichment analysis out of the genes annotated to cis- and trans- eQTMs to explore possible biological implications of our findings. We considered a given KEGG pathway as significantly enriched if the enrichment p-value was ≤ 0.01 based on a two-sided hypergeometric test and at least 10 eQTM-related genes were contributing to that pathway. The Kappa statistic, which is used to define KEGG terms interrelations (edges) and functional groups based on shared genes between terms, was set to 0.4. The enrichment analysis was performed using Cytoscape (version.3.8.2)32 with the ClueGO (version 2.5.8) and CluePedia (version 1.5.8) plugins.33,34

Sensitivity analysis.

Oncogenic transformations can happen several years before cancer diagnosis. Thus, as an attempt to discard cases where DNAm may have been measured after oncogenic transformations started, we conducted a sensitivity analysis by repeating the mediation analysis after excluding lung cancer cases that happened the first five years, as well as calculating the relative mediated effect of the CpG cg05575921 (AHRR) after excluding cases that happened in the first 5 to 15 years of follow-up (10 to 48 lung cancer cases excluded). In addition, DNAm in our data may be reflecting smoking-related inflammation.47,48 Therefore, we repeated the mediation analysis in the FHS adjusting the models for C reactive protein. This analysis could not be done in the SHS due to the lack of inflammation biomarkers at baseline.

Results

Descriptive analysis.

There were 97 lung cancer cases in the SHS, and 56 in the FHS. Participants with lung cancer were older, had higher cumulative smoking and were mostly current smokers (Supplementary Table 2).

Mediation Analysis.

The Cox ISIS model selected 62 Differentially Methylated Positions (DMPs) associated with lung cancer (Supplementary Excel Table 1). Of those, 29 CpGs had statistically significant indirect effects in the SHS for current versus never smoking. Among those, 20 were also measured in the FHS, of which 14 were replicated in the FHS (Table 1). For cumulative smoking, 20 (out of 62) CpGs had statistically significant indirect effects in the SHS. Among those, 14 were also measured in the FHS, of which four were replicated in the FHS (Table 2).

Table 1.

Differences in lung cancer cases per 100,000 person-years comparing current to never smokers attributable to differences in DNA methylation for each CpG (‘mediated effects’) in the Strong Heart Study and replication in the Framingham Heart Study.

| Strong Heart Study | Framingham Heart Study | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediated (i.e., indirect) effect of current vs never smoking through DNAmb |

Direct effect of current vs never smokinga |

Mediated (i.e., indirect) effect of current vs never smoking through DNAmb |

Direct effect of current vs never smokinga |

|||||

| CpG | Chr | Gene | Difference in cancer cases attributable to DNAm (95 % CI) per 100,000 person- years |

Percentage of difference in cancer cases attributable to DNAm (95 % CI) |

Absolute difference in cancer cases comparing current vs never smokers (95 % Cl) per 100,000 person-years |

Difference in cancer cases attributable to DNAm (95 % CI) per 100,000 person-years |

Percentage of difference in cancer cases attributable to DNAm (95 % CI) |

Absolute difference in cancer cases comparing current vs never smokers (95 % CI)a per 100,000 person-years |

| cg05575921 | 5 | AHRR | 253.9 (167.3, 342.3) | 76.5 (50.9, 113.6) | 78.0 (−34.5, 190.5) | 207.7 (65.7, 350.1) | 68.8 (23.2, 172.8) | 94.1 (−107.9, 295.5) |

| cg21566642 | 2 | ALPG | 152.9 (85.9, 221.3) | 45.5 (25.3, 73.7) | 183.6 (66.5, 300.3) | 172.2 (71.3, 273.7) | 57.3 (24.2, 142.2) | 128.5 (−58.1, 315.1) |

| cg14391737* | 11 | PRSS23 | 149.9 (92.2, 210.0) | 42.7 (26.8, 64.4) | 201.1 (94.4, 307.4) | - | - | - |

| cg03636183 | 19 | F2RL3 | 136.9 (79.9, 195.5) | 41.0 (24.3, 63.9) | 196.8 (90.1, 303.2) | 191.4 (57.5, 326.1) | 63.9 (20.5, 162.1) | 108.3 (−90.2, 306.7) |

| cg01940273 | 2 | ALPG | 107.0 (47.9, 167.2) | 31.9 (14.0, 56.2) | 228.9 (109.8, 347.8) | 93.4 (12.5, 174.5) | 31.7 (4.4, 89.4) | 201.4 (12.3, 390.5) |

| cg24859433 | 6 | IER3 | 91.4 (49.2, 136.4) | 26.7 (14.7, 42.3) | 251.1 (146.6, 355.5) | 95.3 (21.8, 169.6) | 32.1 (7.9, 84.7) | 201.5 (18.3, 384.7) |

| cg03329539 | 2 | ALPG | 72.7 (32.5, 115.1) | 21.6 (9.5, 38.1) | 263.9 (152.6, 374.8) | 76.0 (30.2, 122.6) | 25.7 (10.9, 62.5) | 219.9 (44.1, 395.7) |

| cg17739917* | 17 | RARA | 69.9 (26.9, 114.1) | 20.6 (8.1, 35.8) | 270.4 (163.1, 377.4) | - | - | - |

| cg09842685* | 12 | FGF23 | 64.1 (36.2, 94.1) | 18.8 (10.8, 29.6) | 276.5 (173.9, 378.9) | - | - | - |

| cg01899089 | 5 | AHRR | 51.3 (24.9, 80.2) | 15.1 (7.6, 24.9) | 288.5 (184.8, 392.1) | 55.2 (16.2, 95.5) | 18.6 (6, 45.8) | 242.1 (64.7, 419.4) |

| cg04885881 | 1 | SRM | 50.8 (15.4, 87.7) | 14.8 (4.7, 27.1) | 291.6 (185.4, 397.6) | 89.8 (40.1, 141.2) | 30.4 (13.8, 75.3) | 205.4 (28.2, 382.5) |

| cg03707168 | 19 | PPP1R15A | 48.4 (16.9, 82.7) | 14.2 (5.1, 25.6) | 292.4 (186.4, 398.2) | 61.2 (17.2, 106.1) | 20.6 (6.5, 50.5) | 235.5 (59.3, 411.6) |

| cg11902777 | 5 | AHRR | 42.6 (25.3, 62.2) | 12.4 (7.4, 19.5) | 301.2 (196.0, 406.3) | 43.7 (11.2, 77.2) | 15.0 (4.1, 39.6) | 248.5 (68.6, 428.2) |

| cg14580211 | 5 | SMIM3 | 39.3 (10.2, 69.8) | 11.5 (3.1, 21.9) | 301.6 (194.9, 408.0) | 42.1 (−13.9, 98.9) | 14.4 (−6.2, 43.9) | 250.1 (70.4, 429.9) |

| cg14624207 | 11 | LRP5 | 38.3 (16.6, 62.7) | 11.4 (4.9, 20.1) | 298.7 (193.1, 404.1) | 40.0 (−6.1, 86.7) | 13.6 (−2.5, 41.9) | 254.2 (70.3, 437.9) |

| cg27241845 | 2 | ECEL1P2 | 36.2 (11.3, 63.6) | 10.8 (3.4, 20.5) | 299.4 (192.3, 406.1) | 45.3 (6.5, 84.8) | 15.5 (2.6, 39.3) | 246.8 (70.9, 422.6) |

| cg01513913 | 14 | FAM30A | 35.1 (12.0, 60.5) | 10.4 (3.5, 19.7) | 301.7 (193.9, 409.3) | 33.1 (−7.6, 74.9) | 11.3 (−2.7, 41.2) | 259.6 (68.6, 450.4) |

| cg16207944* | 14 | FAM30A | 33.9 (12.5, 57.4) | 10.1 (3.7, 18.6) | 302.9 (196.3, 409.2) | - | - | - |

| cg23916896 | 5 | AHRR | 33.9 (12.5, 57.5) | 10.0 (3.8, 17.9) | 305.3 (200.6, 409.8) | 95.8 (47.0, 145.7) | 32.3 (15.1, 82.1) | 201.1 (20.2, 382.0) |

| cg07251887 | 17 | RECQL5 | 29.3 (10.5, 50.8) | 8.7 (3.2, 16.1) | 307.8 (201.7, 413.6) | 59.8 (21.2, 99.6) | 20.4 (6.8, 57.8) | 233.5 (47.8, 419.3) |

| cg02738868* | 14 | ELMSAN1 | 28.7 (5.3, 53.8) | 8.5 (1.6, 17.2) | 310.6 (202.7, 418.2) | - | - | - |

| cg06521527* | 6 | NEDD9 | 27.4 (8.9, 48.1) | 8.0 (2.7, 14.6) | 314.5 (209.8, 419.1) | - | - | - |

| cg24947681* | 15 | THBS1 | 26.6 (7.9, 47.4) | 7.9 (2.4, 15.3) | 310.5 (203.5, 417.3) | - | - | - |

| cg16201146 | 20 | SLC24A3 | 26.0 (9.1, 45.5) | 7.6 (2.8, 13.8) | 315.7 (210.9, 420.3) | 17.9 (−6.6, 43.5) | 6.2 (−2.9, 19.1) | 274.2 (93.4, 455.1) |

| cg18158149* | 1 | NOS1AP | 25.9 (6.8, 47.3) | 7.6 (2.1, 14.1) | 317.7 (213.8, 421.4) | - | - | - |

| cg23025288* | 2 | HS6ST1 | 23.6 (5.8, 43.7) | 7.0 (1.8, 13.6) | 312.7 (207.6, 417.6) | - | - | - |

| cg23771366 | 11 | PRSS23 | 23.7 (3.7, 45.7) | 7.0 (1.1, 14.4) | 316.1 (209.1, 422.7) | 80.1 (22.8, 138.6) | 27.2 (9.1, 64.4) | 214.4 (42.8, 385.9) |

| cg24556382 | 4 | GALNT7 | 19.5 (5.3, 36.0) | 5.7 (1.6, 10.7) | 321.9 (217.5, 425.9) | 32.8 (−2.9, 69.4) | 11.2 (−1.2, 35.3) | 260.2 (75.6, 444.8) |

| cg25799109 | 3 | ARHGEF3 | 19.4 (3.8, 37.2) | 5.7 (1.1, 11.6) | 319.1 (213.3, 424.6) | 3.9 (−14.2, 22.5) | 1.4 (−6.8, 9.4) | 286.0 (103.1, 468.9) |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval.

CpGs not present in the 450K array, therefore not evaluated in the Framingham Heart Study.

Models were adjusted for age, sex, former smoking, BMI and cell counts (CD8T, CD4T, NK, B cells and monocytes). Additionally adjusted for study center (Arizona, Oklahoma or North and South Dakota) and five genetic PCs in the Strong Heart Study.

Absolute changes in cancer incidence (per 100,000 person-years) for current versus never smokers were obtained from Aalen additive hazards models.

Effects mediated by DNA methylation were estimated with the ‘product of coefficients method’ that multiplies the coefficient for the mean change in DNA methylation for the current versus never smoking comparison from the mediator model by the absolute change in cancer incidence cases for the current versus never smoking comparison expressed in absolute terms (difference in change reflecting the number of attributable cancer cases per 100,000 person-years) and relative to the adjusted changes in cancer cases before adding DNA methylation to the model. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in the table were derived by simulation from the estimated model coefficients and covariance matrices.

Table 2.

Differences in lung cancer cases per 100,000 person-years for a 10 pack-years change attributable to differences in DNA methylation for each CpG (‘mediated effects’) in the Strong Heart Study and replication in the Framingham Heart Study.

| Strong Heart Study | Framingham Heart Study | |||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mediated (i.e., indirect) effect of cigarette pack-years smoking through DNAm |

Direct effect of cigarette pack-years |

Mediated (i.e., indirect) effect of cigarette pack-years smoking through DNAm |

Direct effect of cigarette pack-years |

|||||

| CpG | Chr | Gene | Difference in cancer cases attributable to DNAm (95 % CI) |

Percentage of difference in cancer cases attributable to DNAm (95 % CI) |

Absolute difference in cancer cases per 10 pack-years increase (95 % CI) |

Difference in cancer cases attributable to DNAm (95 % CI) |

Percentage of difference in cancer cases attributable to DNAm (95 % CI) |

Absolute difference in cancer cases per 10 pack-years increase (95 % CI) |

| cg14391737* | 11 | PRSS23 | 17.3 (7.5, 27.6) | 14.2 (5.5, 31.9) | 104.9 (45.1, 164.5) | - | - | - |

| cg05575921 | 5 | AHRR | 14.4 (6.7, 22.6) | 11.9 (4.6, 28.9) | 106.8 (45.5, 167.9) | 10.1 (−16.2, 36.5) | 4.7 (−7.3, 23.6) | 206.4 (85.4, 327.2) |

| cg03636183 | 19 | F2RL3 | 10.2 (3.3, 17.5) | 8.4 (2.4, 20.6) | 112.0 (51.9, 171.9) | 21.5 (−2.9, 46.2) | 10.9 (−1.7, 28.5) | 175.8 (71.5, 279.7) |

| cg21566642 | 2 | ALPG | 9.4 (2.0, 17.0) | 7.6 (1.5, 19.6) | 113.1 (52.9, 173.1) | 13.8 (−5.4, 33.1) | 7.0 (−2.6, 25.9) | 182.3 (69.1, 295.3) |

| cg24859433 | 6 | IER3 | 6.9 (2.8, 11.8) | 5.6 (2.1, 13.1) | 115.7 (56.9, 174.4) | 11.8 (−1.8, 25.9) | 6.0 (−1.0, 17.5) | 186.6 (79.0, 293.9) |

| cg03329539 | 2 | ALPG | 6.3 (0.9, 12.3) | 5.2 (0.7, 14) | 116.3 (56.4, 176.0) | 9.6 (0.2, 19.5) | 4.9 (0.1, 14.0) | 186.9 (79.5, 294.2) |

| cg09842685* | 12 | FGF23 | 5.4 (2.3, 9.2) | 4.4 (1.7, 10) | 117.2 (58.8, 175.5) | - | - | - |

| cg11902777 | 5 | AHRR | 4.4 (1.7, 7.7) | 3.6 (1.4, 7.9) | 119.0 (60.9, 176.9) | 6.5 (−1.3, 14.8) | 3.3 (−0.7, 10.2) | 191.0 (83.7, 298.1) |

| cg03707168 | 19 | PPP1R15A | 4.2 (0.9, 8.4) | 3.4 (0.7, 8) | 119.2 (61.4, 176.9) | 11.1 (0.4, 22.1) | 5.6 (0.2, 15.3) | 186.8 (79.8, 293.7) |

| cg14624207 | 11 | LRP5 | 3.8 (1.1, 7.3) | 3.1 (0.8, 7.5) | 119.2 (60.7, 177.5) | 2.2 (−5.5, 10.1) | 1.1 (−3.3, 6.0) | 195.9 (89.2, 302.4) |

| cg27241845 | 2 | ECEL1P2 | 3.4 (0.4, 7.2) | 2.8 (0.3, 7.3) | 120.0 (61.5, 178.4) | 5.3 (−3.1, 14.1) | 2.7 (−1.6, 9.7) | 193.1 (85.1, 300.7) |

| cg16207944* | 14 | FAM30A | 3.3 (0.2, 6.9) | 2.7 (0.1, 7.3) | 120.1 (61.4, 178.6) | - | - | - |

| cg01513913 | 14 | FAM30A | 3.3 (0.3, 6.9) | 2.7 (0.2, 7.5) | 119.8 (60.8, 178.7) | 4.2 (−5.1, 13.8) | 2.1 (−3, 8.2) | 194.22 (87.9, 300.3) |

| cg01899089 | 5 | AHRR | 3.1 (0.8, 6.3) | 2.6 (0.6, 6.8) | 119.1 (60.3, 177.8) | 9.2 (−0.1, 19.1) | 4.7 (0.0, 13.0) | 188.6 (81.7, 295.1) |

| cg07251887 | 17 | RECQL5 | 3.2 (0.5, 6.6) | 2.6 (0.4, 6.9) | 120.3 (61.5, 178.9) | 10.3 (1.9, 19.4) | 5.2 (1.0, 12.9) | 186.8 (81.1, 292.3) |

| cg23916896 | 5 | AHRR | 2.7 (0.6, 5.7) | 2.2 (0.4, 5.8) | 121.7 (63.1, 180.1) | 14.8 (3.9, 26.2) | 7.5 (1.9, 19.2) | 181.3 (74.5, 287.9) |

| cg24947681* | 15 | THBS1 | 2.7 (0.3, 5.7) | 2.2 (0.2, 5.7) | 121.3 (62.8, 179.6) | - | - | - |

| cg06521527* | 6 | NEDD9 | 2.6 (0.3, 5.6) | 2.1 (0.3, 5.4) | 120.6 (62.5, 178.7) | - | - | - |

| cg04885881 | 1 | SRM | 2.6 (0.1, 5.8) | 2.1 (0.1, 5.9) | 120.4 (61.9, 178.7) | 5.3 (−3.1, 14.1) | 2.7 (−1.6, 9.7) | 193.1 (85.2, 300.7) |

| cg18158149* | 1 | NOS1AP | 1.9 (0.2, 4.3) | 1.5 (0.1, 4) | 122.1 (63.9, 180.1) | - | - | - |

Abbreviations: CI, confidence interval; DNAm, DNA methylation.

CpGs not present in the 450K array, therefore not evaluated in the Framingham Heart Study.

Models were adjusted for age, sex, former smoking, BMI and cell counts (CD8T, CD4T, NK, B cells and monocytes). Additionally adjusted for study center (Arizona, Oklahoma or North and South Dakota) and five genetic PCs in the Strong Heart Study.

Absolute changes in cancer incidence (per 100,000 person-years) for a 10 pack-years change were obtained from Aalen additive hazards models.

Effects mediated by DNA methylation were estimated with the ‘product of coefficients method’ that multiplies the coefficient for the mean change in DNA methylation for a 10 pack-years increase from the mediator model by the absolute change in cancer incidence cases for a 10 pack-years increase expressed in absolute terms (difference in change reflecting the number of attributable cancer cases per 100,000 person-years) and relative to the adjusted changes in cancer cases before adding DNA methylation to the model. The 95% confidence intervals (CIs) in the table were derived by simulation from the estimated model coefficients and covariance matrices.

A descriptive table comparing blood DNAm proportions in the SHS and the FHS for the CpGs that were statistically significant in the mediation analysis in both the SHS and the FHS can be found in Supplementary Table 3. DNAm proportions at the specific CpGs were highly consistent in the SHS and the FHS. DNAm proportions were generally lower in individuals that developed cancer as compared to those that did not.

Estimated PC loadings from DMPs with statistically significant mediated effects in both the SHS and the FHS can be found in Supplementary Table 4. RC1 (rotated principal component 1), RC2 and RC3 explained 40 %, 11.6 % and 8.8 % of the total variance, respectively. Supplementary Figure 2 shows the clustering of participants by lung cancer status based on scores for the estimated PCs.

Expression quantitative trait methylation (eQTM) and biological pathway enrichment.

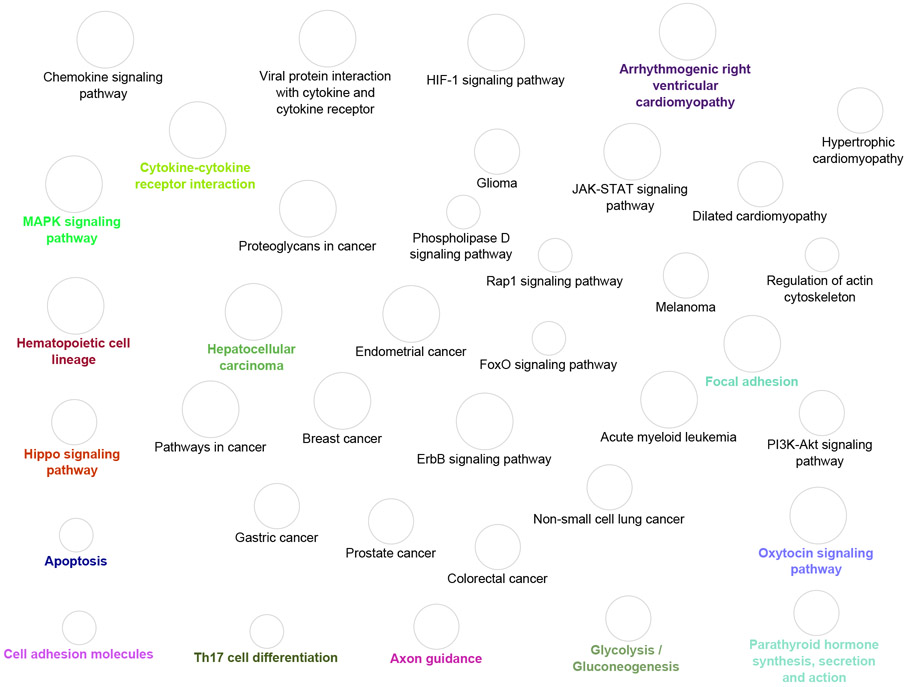

At a statistical significance p-value < 10−4, 17 mediating DMPs of lung cancer in common for the SHS and FHS were associated with 12 cis-eQTMs and 2415 trans-eQTMs (Supplementary Excel Table 2). The large majority of the eQTM-associated transcripts (75.7 % of transcripts in trans and 83.3 % of transcripts in cis) showed, overall, gene expression downregulation (Supplementary Excel Table 2). The genes annotated to the top transcripts were GPR15, LINC00599, LRRN3 and SEMA6B (Table 3). Biological pathway enrichment analysis of target genes annotated to eQTM-associated transcripts showed 37 enriched biological pathways (Figure 1). The enriched pathways were largely related to cancer (Figure 1).

Table 3.

Expression quantitative trait methylation (eQTM) for the CpG sites that were significant for both the Strong Heart Study and the Framingham Heart Study in the mediation analysis, and the CpG sites that were significant for the SHS in the multimediator model.

| Smoking- related DMP |

DNA methylation gene symbol |

Smoking-related exposure | N cis- eQTMs |

N trans- eQTMs |

Direction of association |

CpG location |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| cg05575921a | AHRR | Current vs never | 3 | 655 | Inverse | Body |

| cg03636183 | F2RL3 | Current vs never, pack-years | 0 | 347 | Inverse | Body |

| cg03707168 | PPP1R15A | Current vs never, pack-years | 1 | 276 | Inverse | Body |

| cg01899089 | AHRR | Current vs never, pack-years | 1 | 63 | Inverse | Body |

| cg07251887 | RECQL5 | Current vs never, pack-years | 1 | 43 | Inverse | TSS1500 |

| cg23771366 | PRSS23 | Current vs never | 0 | 37 | Inverse | TSS1500 |

| cg11902777a | AHRR | Current vs never, pack-years | 1 | 24 | Inverse | Body |

| cg23916896 | AHRR | Current vs never, pack-years | 1 | 17 | Inverse | Body |

| cg01940273 | ALPG | Current vs never | 0 | 2 | Positive | Intergenic |

| cg03329539 | ALPG | Current vs never, pack-years | 0 | 1 | Inverse | Intergenic |

| cg04885881 | SRM | Current vs never, pack-years | 0 | 1 | Inverse | Intergenic |

| cg14624207 | LRP5 | Current vs never, pack-years | 0 | 1 | Inverse | Body |

| cg21566642 | ALPG | Current vs never | 0 | 1 | Inverse | Intergenic |

| cg24859433a | IER3 | Current vs never, pack-years | 0 | 1 | Inverse | Intergenic |

| cg27241845 | ECEL1P2 | Current vs never, pack-years | 0 | 1 | Inverse | Intergenic |

Abbreviations: eQTM, expression quantitative trait methylation; IQR, interquartile range.

Effect estimates calculated from a linear model with residualized expression as the response, residualized DNA methylation as an independent variable, adjusting for sex, age, predicted blood cell fraction to account for signal heterogeneity from multiple sample types, five expression PCs and 10 DNA methylation PCs.

Significant CpGs in the multimediator model.

Figure 1.

Network of significantly enriched pathways for annotated trans-eQTMs genes from CpGs with significant mediated effects in the Strong Heart Study and the Framingham Heart Study.

KEGG pathways are represented as nodes and the node size represents the term enrichment significance (increasing size of nodes reflect smaller p-values). Nodes with the same colors reflect they belong to the same cluster based on a Kappa clustering statistic cut-off of 0.4. The nodes with colored letters represent the most significant pathway within a clustering group.

Multiple-mediators analysis.

In multi-mediator models, in absolute terms, of the 385.7 (95% CI 265.9, 509.8) incident lung cancer cases per 100,000 person-years attributable to current smoking, 223.6 (95 % CI 126.1, 324.5), 62.6 (95 % CI 16.8, 110.2) and 28.3 (95 % CI 11.5, 46.5) lung cancer cases were attributable to differences in DNAm in cg05575921 (AHRR), cg24859433 (IER3) and cg11902777 (AHRR), respectively (Table 4). In addition, of the 315.8 (95 % CI 160.9, 468.8) incident lung cancer cases per 100,000 person-years attributable to heavy smoking (cigarette pack-years >= 20), 86.2 (95 % CI 38.9, 134.8), 29.6 (95 % CI 7.6, 55.5) and 14.3 (95 % CI 5.0, 25.8) lung cancer cases were attributable to differences in DNAm in cg05575921 (AHRR), cg24859433 (IER3) and cg11902777 (AHRR), respectively (Table 4). The joint mediated effects estimated using the “difference of coefficients method” were similar to the sum of individual mediated effects calculated using the multimediator model (Supplementary Table 5). For the FHS, of the 46.7 (95% CI 20.8, 72.9) incident lung cancer cases per 100,000 person-years attributable to current smoking, 27.7 (95 % CI 5.8, 50.1), 5.6 (95 % CI −2.5, 13.8) and 2.1 (95 % CI −2.3, 6.6) lung cancer cases were attributable to differences in DNAm in cg05575921 (AHRR), cg24859433 (IER3) and cg11902777 (AHRR), respectively (Table 5).

Table 4.

Differences in lung cancer cases per 100,000 person-years attributable to differences in DNA methylation for each CpG (‘mediated effects’) from a multimediator model in the Strong Heart Study.

| CpG | Gene | Mediated (i.e. indirect) effect of current vs never smoking through DNAm (95 % CI)b |

Percentage of difference in cancer cases attributable to DNAm (95 % CI)c |

|---|---|---|---|

| Current versus never smoking | |||

| cg05575921 | AHRR | 223.6 (126.1, 324.5) | 58.1 (30.8, 98.4) |

| cg24859433 | IER3 | 62.6 (16.8, 110.2) | 16.2 (4.2, 32.1) |

| cg11902777 | AHRR | 28.3 (11.5, 46.5) | 7.3 (2.9, 13.8) |

| cg05575921 + cg24859433 + cg11902777 | Joint effect | 314.6 (210.4, 419.5) | 81.3 (55.4, 120.4) |

| Heavy versus light smoking a | |||

| cg05575921 | AHRR | 86.3 (38.9, 134.8) | 29.4 (11.3, 60.9) |

| cg24859433 | IER3 | 29.6 (7.6, 55.5) | 10.0 (2.4, 22.9) |

| cg11902777 | AHRR | 14.3 (5.0, 25.8) | 4.9 (1.5, 11.1) |

| cg05575921 + cg24859433 + cg11902777 | Joint effect | 130.2 (80.8, 181.3) | 43.9 (22.9, 83.6) |

Abbreviations: DNAm, DNA methylation.

Direct effect of smoking in lung cancer: 71.1 (−60.7, 200.0), total effect: 385.7 (265.9, 509.8).

Cigarette pack-years < 20 versus >= 20

Mediated effects are calculated based on the counterfactual framework, i.e. leaving the exposure constant and substracting the number of cancer cases per 100,000 person-years with DNA methylation fixed to the value it would take in presence of current smoking to the number of cancer cases per 100,000 person-years with DNA methylation fixed to the value it would take in absence of smoking [Y(E, M(1)) − Y[E, M(0)), being 1 current smoking and 0 never smoking]. For individual mediated effects, DNA methylation levels of all CpGs except the CpG of interest are fixed to the value of the exposure (i.e., only the CpG of interest is variable). For the joint mediated effects, all CpGs are variable.

Mediated percentages are calculated as the rate between the mediated effect and the total effect. Total effect is calculated based on the counterfactual framework, i.e. substracting the number of cancer cases per 100,000 person-years with the exposure fixed to current smoking and DNA methylation fixed to the value it would take in presence of current smoking to the number of cancer cases per 100,000 person-years with the exposure fixed to never smoking and DNA methylation fixed to the value it would take in absence of smoking [Y(1, M(1)) − Y[0, M(0)), being 1 current smoking and 0 never smoking]. Model adapted from Jerolon et al. [36]

Models were adjusted for age, sex, former smoking, BMI, study center (Arizona, Oklahoma or North and South Dakota) cell counts (CD8T, CD4T, NK, B cells and monocytes) and five genetic PC

Table 5.

Differences in lung cancer cases per 100,000 person-years comparing current to never smokers attributable to differences in DNA methylation for each CpG (‘mediated effects’) from a multimediator model in the Framingham Heart Study.

| CpG | Gene | Mediated (i.e. indirect) effect of current vs never smoking through DNAm (95 % CI)a |

Percentage of difference in cancer cases attributable to DNAm (95 % CI)b |

|---|---|---|---|

| cg05575921 | AHRR | 27.7 (5.8, 50.1) | 66.3 (11.8, 162.7) |

| cg24859433 | IER3 | 5.6 (−2.5, 13.8) | 13.4 (−5.5, 40.5) |

| cg11902777 | AHRR | 2.1 (−2.3, 6.6) | 5.1 (−5.4, 18.9) |

| cg05575921 + cg24859433 + cg11902777 | Joint effect | 35.5 (13.6, 57.6) | 82.8 (30.0, 175.7) |

Abbreviations: DNAm, DNA methylation.

Direct effect of smoking in lung cancer: 11.3 (−19.5, 41.7), total effect: 46.7 (20.8, 72.9).

Mediated effects are calculated based on the counterfactual framework, i.e. leaving the exposure constant and substracting the number of cancer cases per 100,000 person-years with DNA methylation fixed to the value it would take in presence of current smoking to the number of cancer cases per 100,000 person-years with DNA methylation fixed to the value it would take in absence of smoking [Y(E, M(1)) − Y[E, M(0)), being 1 current smoking and 0 never smoking]. For individual mediated effects, DNA methylation levels of all CpGs except the CpG of interest are fixed to the value of the exposure (i.e., only the CpG of interest is variable). For the joint mediated effects, all CpGs are variable.

Mediated percentages are calculated as the rate between the mediated effect and the total effect. Total effect is calculated based on the counterfactual framework, i.e. substracting the number of cancer cases per 100,000 person-years with the exposure fixed to current smoking and DNA methylation fixed to the value it would take in presence of current smoking to the number of cancer cases per 100,000 person-years with the exposure fixed to never smoking and DNA methylation fixed to the value it would take in absence of smoking [Y(1, M(1)) − Y[0, M(0)), being 1 current smoking and 0 never smoking]. Model adapted from Jerolon et al. [36]

Models were adjusted for age, sex, former smoking, BMI and cell counts (CD8T, CD4T, NK, B cells and monocytes).

Sensitivity analysis.

The mediation models excluding cancer cases diagnosed during the first 5 follow-up years yielded similar results as compared to the main analyses (Supplementary Excel Tables 3-4). The relative mediated effects of the CpG cg05575921 (AHRR) decreased when the number of excluded cancer cases was higher (Supplementary Figure 3). The mediation analysis adjusting for C reactive protein in the FHS led to higher indirect effects of DNAm on the association between current versus never smoking and lung cancer. All CpG sites that were significant in the main mediation analysis remained significant after the adjustment of C reactive protein (Supplementary Excel Tables 5-6).

Discussion

In our study, we conducted a formal mediation analysis (including multiple mediators evaluated simultaneously) using time-to-newly diagnosed cancer data, and found that a substantial extent of the prospective association of smoking with lung cancer was explained by differences in blood DNAm. Results were largely consistent in the FHS, including additional validation of findings with expression data, which mostly showed methylation-related downregulation of distant genes that have a plausible role on cancer biological pathways. In the multimediator model, a joint mediated effect of 81.3 % was driven by three DMPs (annotated to AHRR and IER3) for lung cancer.

The fact that AHRR and F2RL3 genes showed significant mediated effects in our single mediator analysis for both endpoints is widely consistent with findings from numerous study populations.7 However, previous studies lack formal mediation analysis, except for a case-control study which was part of a Norwegian cohort.15 This study reported that AHRR and F2RL3 genes explained ~37% of the total effect of smoking in lung cancer. Nevertheless, only single mediation analysis was conducted, and the study lacked follow-up. Also, a study used data from The Cancer Genome Atlas to assess mediation of the association between smoking and lung cancer mortality by blood DNAm35 with inconsistent findings compared to our study. Nevertheless, this study had a smaller sample size (N=907) and used Cox proportional hazards models in mediation analysis, which is not advisable due to the non-collapsibility of the hazard ratios.36 A recent study conducted a Mendelian randomization analysis to assess the potential causal association of DNAm in several smoking-related genes including AHRR and F2RL3 and lung cancer with conflicting results,20 possibly given some of the limitations reported by the authors. Additional Mendelian Randomization studies with sufficiently valid genetic instruments and methods to accomodate the multiple correlated DNAm mediators are needed.

Interestingly, we mostly found inverse associations between blood DNAm at sites identified in the mediation analysis and gene expression. Of especial interest is GPR15, as it was identified both as a closest annotated gene to a relevant DMP from the multimediator analysis, and as a trans target gene of another DMPs in the eQTM analysis. DNAm in this gene was identified as a potential mediator on the association between smoking and lung cancer in a previous study.21 Upregulation of GPR15 was proposed as a biological mechanism involved in smoking-related chronic inflammatory diseases.37 Subsequent biological pathway enrichment analysis among target genes annotated to eQMTs pointed to relevant pathways in cancer.38-41 The association of DNAm with gene expression in our cross-sectional analysis, however, is not definitive proof that changes on DNAm result in changes on gene expression. Research is needed to confirm the influence of smoking-related DNAm on gene expression.

On the other hand, the mediated effect of DNAm on the association between smoking and lung cancer was mostly driven by DMPs annotated to the closest genes AHRR and IER3. While there is substantial accumulated evidence supporting a role of the AHRR gene, IER3 has been less studied. Upregulation of IER3, which plays a differential role in tumorigenesis depending on the cell-type,42 promotes apoptosis in some cells such as hepatocytes, keratinocytes and various tumour cell lines; but acts as an anti-apoptotic agent in others, including Jurkat or 3T3 cells. Downregulation of IER3, however, is associated with decreased apoptosis and cell cycle progression.43 Further studies are needed to clarify the potential role of the gene IER3 in lung cancer.

This study has several limitations. First, although the replication in the FHS was high for lung cancer in the current versus never smoking model, it was smaller for lung cancer in the cumulative smoking model and for smoking-related cancers. Differences in smoking intensity and cessation across the SHS and FHS could explain some of the non-replicated DMPs (Supplementary Table 1). Also, non-fatal cancer data might be incomplete in the SHS as non-fatal cancers were not confirmed with chart review and no linkage with the cancer registry is available. Despite these limitation, however, we still found substantial replication of findings between the SHS and the FHS. Self-reported smoking might also constitute a source of bias. Therefore, in a previous work conducted in the Strong Heart Study,22 we predicted smoking status using DNAm data with the EpismokEr tool.44 Most of the misclassification between self-reported and predicted smoking status was from participants who self-reported to be former smokers, but for which the algorithm predicted them to be never smokers. Given that it is less likely that people would indicate to be former smokers when they have never smoked, this aspect could be related to the previously reported reversible nature of some of the smoking-related epigenetic marks.45 Most of the current smokers identified by the algorithm, however, were correctly classified.

In addition, the joint mediated effect reported by the multimediate algorithm was very high (81.3 % and 82.8 % of the effect of smoking in lung cancer for the SHS and the FHS, respectively). Mediation analysis, however, provides valid estimates only if the mediation assumptions such as absence of unmeasured confounding, which cannot be fully verified in practice, hold.46 In addition, the multimediate algorithm is only valid in settings of non-causal correlations.23 Consequently, our results need to be interpreted with caution, especially for probes that could not be replicated because they were not available by design in the replication microarray. Experimental studies are needed to confirm the role of the identified blood DNAm signature of smoking in the association between smoking and lung cancer.

Strengths of our study include replication in an independent cohort, the large sample size with methylation data from one of the largest microarrays nowadays available, the availability of information to account for numerous potential confounders and the additional validation of the results using gene expression data. In addition, we used state-of-the-art statistical methods including the multimediator model for time-to-event data, which enabled the evaluation of correlated methylation sites jointly.

Conclusions

In conclusion, the prospective association of smoking with lung cancer in this study was largely explained by differences in few specific blood DNAm sites. These findings contribute to the identification of potentially novel mechanisms of lung cancer, and provide evidence in favor of DNAm as a potential biological intermediary in the association between smoking and lung cancer. However, the no unmeasured confounding assumption for mediation analysis cannot be fully verified in practice. Therefore, additional experimental and translational research targeting the identified methylation sites is needed to assess the relevance of these epigenetic signatures for the prevention and control of smoking-related cancer and lung cancer.

Supplementary Material

We found mediated effects of epigenetics on the association between smoking and cancer

Associated gene expression was down-regulated

Genomic sites with mediated effects were related to biological pathways in cancer

The mediated effect was jointly driven by AHRR and IER3 genes in lung cancer

Acknowledgements:

The Strong Heart Study is funded by grants from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (NHLBI) (contract numbers 75N92019D00027, 75N92019D00028, 75N92019D00029 and 75N92019D00030) and previous grants (R01HL090863, R01HL109315, R01HL109301, R01HL109284, R01HL109282, and R01HL109319 and cooperative agreements: U01HL41642, U01HL41652, U01HL41654, U01HL65520 and U01HL65521) and by the National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences (grant numbers R01ES021367, R01ES025216, P42ES033719, P30ES009089).

The Framingham Heart Study (FHS) is funded by National Institutes of Health contract N01-HC-25195. The laboratory work for this investigation was funded by the Division of Intramural Research, National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institutes, National Institutes of Health and an NIH Director’s Challenge Award (D. Levy, Principal Investigator).

ADR was supported by a fellowship from “la Caixa” Foundation (ID 100010434) (fellowship code “LCF/BQ/DR19/11740016”).

MTP was supported by the Strategic Action for Research in Health sciences (PI15/00071) and CIBERCV, which are initiatives from Instituto de Salud Carlos III and the Spanish Ministry of Science and Innovation and co-funded with European Funds for Regional Development (FEDER), by the Third AstraZeneca Award for Spanish Young Researchers, and by the State Agency for Research (PID2019-108973RB- C21).

Ana Navas-Acien reports financial support was provided by National Heart Lung and Blood Institute. Ana Navas-Acien reports financial support was provided by National Institute of Environmental Health Sciences. Daniel Levy reports financial support was provided by National Institutes of Health. Arce Domingo-Relloso reports financial support was provided by La Caixa Foundation.

Footnotes

Sample CRediT author statement

Arce Domingo-Relloso: Formal analysis, Methodology, Software, Writing - Original draft. Roby Joehanes: Validation, Formal analysis, Writing – review & editing. Zulema Rodriguez-Hernandez: Formal analysis. Lies Lahousse: Conceptualization, Writing – review & editing. Karin Haack: Data curation, Resources. M. Daniele Fallin: Conceptualization, Supervision. Miguel Herreros-Martinez: Resources. Jason G. Umans: Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Lyle G. Best: Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Tianxiao Huan: Validation, Writing – review & editing. Chunyu Liu: Validation, Writing – review & editing. Jiantao Ma: Validation, Writing – review & editing. Chen Yao: Validation, Writing – review & editing. Allan Jerolon: Software. Jose D. Bermudez: Software. Shelley A. Cole: Data curation, Resources, Supervision. Dorothy A. Rhoades: Conceptualization, Supervision, Writing - review & editing. Daniel Levy: Funding acquisition, Validation, Supervision. Ana Navas-Acien: Conceptualization, Funding acquisition, Investigation, Writing - original draft. Maria Tellez-Plaza: Conceptualization, Investigation, Writing - original draft.

Declaration of interests

The authors declare that they have no known competing financial interests or personal relationships that could have appeared to influence the work reported in this paper.

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References

- 1.Vaissière T, Hung RJ, Zaridze D, et al. Quantitative analysis of DNA methylation profiles in lung cancer identifies aberrant DNA methylation of specific genes and its association with gender and cancer risk factors. Cancer Res. 2009;69(1):243–252. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-08-2489 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Carvalho RH, Hou J, Haberle V, et al. Genomewide DNA methylation analysis identifies novel methylated genes in non-small-cell lung carcinomas. J Thorac Oncol. 2013;8(5):562–573. doi: 10.1097/JTO.0b013e3182863ed2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Wauters E, Janssens W, Vansteenkiste J, et al. DNA methylation profiling of non-small cell lung cancer reveals a COPD-driven immune-related signature. Thorax. 2015;70(12):1113–1122. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2015-207288 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Tsou JA, Shen LYC, Siegmund KD, et al. Distinct DNA methylation profiles in malignant mesothelioma, lung adenocarcinoma, and non-tumor lung. Lung Cancer. 2005;47(2):193–204. doi: 10.1016/j.lungcan.2004.08.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bjaanæs MM, Fleischer T, Halvorsen AR, et al. Genome-wide DNA methylation analyses in lung adenocarcinomas: Association with EGFR, KRAS and TP53 mutation status, gene expression and prognosis. Mol Oncol. 2016;10(2):330–343. doi: 10.1016/j.molonc.2015.10.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Klutstein M, Nejman D, Greenfield R, Cedar H. DNA Methylation in Cancer and Aging. Cancer Res. 2016;76(12):3446–3450. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-15-3278 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Joehanes R, Just AC, Marioni RE, et al. Epigenetic Signatures of Cigarette Smoking. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2016;9(5):436–447. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.116.001506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Christiansen C, Castillo-Fernandez JE, Domingo-Relloso A, et al. Novel DNA methylation signatures of tobacco smoking with trans-ethnic effects. Clin Epigenetics. 2021;13(1):1–13. doi: 10.1186/S13148-021-01018-4/FIGURES/3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Zong D, Liu X, Li J, Ouyang R, Chen P. The role of cigarette smoke-induced epigenetic alterations in inflammation. Epigenetics and Chromatin. 2019;12(1):1–25. doi: 10.1186/s13072-019-0311-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Baglietto L, Ponzi E, Haycock P, et al. DNA methylation changes measured in pre-diagnostic peripheral blood samples are associated with smoking and lung cancer risk. Int J Cancer. 2017;140(1):50–61. doi: 10.1002/ijc.30431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Bakulski KM, Dou J, Lin N, London SJ, Colacino JA. DNA methylation signature of smoking in lung cancer is enriched for exposure signatures in newborn and adult blood. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):1–13. doi: 10.1038/s41598-019-40963-2 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tan Q, Wang G, Huang J, et al. Epigenomic analysis of lung adenocarcinoma reveals novel DNA methylation patterns associated with smoking. Onco Targets Ther. 2013;6:1471–1479. doi: 10.2147/OTT.S51041 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zhang Y, Elgizouli M, Schöttker B, Holleczek B, Nieters A, Brenner H. Smoking-associated DNA methylation markers predict lung cancer incidence. Clin Epigenetics. 2016;8:127. doi: 10.1186/s13148-016-0292-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tekpli X, Zienolddiny S, Skaug V, Stangeland L, Haugen A, Mollerup S. DNA methylation of the CYP1A1 enhancer is associated with smoking-induced genetic alterations in human lung. Int J Cancer. 2012;131(7):1509–1516. doi: 10.1002/ijc.27421 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Fasanelli F, Baglietto L, Ponzi E, et al. Hypomethylation of smoking-related genes is associated with future lung cancer in four prospective cohorts. Nat Commun. 2015;6(1):10192. doi: 10.1038/ncomms10192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bojesen SE, Timpson N, Relton C, Smith GD, Nordestgaard BG. AHRR (cg05575921) hypomethylation marks smoking behaviour, morbidity and mortality. Thorax. 2017;72(7):646–653. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2016-208789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Yao C, Joehanes R, Wilson R, et al. Epigenome-wide association study of whole blood gene expression in Framingham Heart Study participants provides molecular insight into the potential role of CHRNA5 in cigarette smoking-related lung diseases. Clin Epigenetics. 2021;13(1). doi: 10.1186/S13148-021-01041-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Herceg Z, Ambatipudi S. Smoking-associated DNA methylation changes: No smoke without fire. Epigenomics. 2019;11(10):1117–1119. doi: 10.2217/epi-2019-0136 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Vaz M, Hwang SY, Kagiampakis I, et al. Chronic Cigarette Smoke-Induced Epigenomic Changes Precede Sensitization of Bronchial Epithelial Cells to Single-Step Transformation by KRAS Mutations. Cancer Cell. 2017;32(3):360–376.e6. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2017.08.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Battram T, Richmond RC, Baglietto L, et al. Appraising the causal relevance of DNA methylation for risk of lung cancer. Int J Epidemiol. 2019;48(5):1493–1504. doi: 10.1093/IJE/DYZ190 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Sun YQ, Richmond RC, Suderman M, et al. Assessing the role of genome-wide DNA methylation between smoking and risk of lung cancer using repeated measurements: the HUNT study. Int J Epidemiol. 2021;50(5):1482–1497. doi: 10.1093/IJE/DYAB044 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Domingo-Relloso A, Riffo-Campos AL, Haack K, et al. Cadmium, Smoking, and Human Blood DNA Methylation Profiles in Adults from the Strong Heart Study. Environ Health Perspect. 2020;128(6):067005. doi: 10.1289/EHP6345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jérolon A, Baglietto L, Birmelé E, Alarcon F, Perduca V. Causal mediation analysis in presence of multiple mediators uncausally related. Int J Biostat. October 2020. doi: 10.1515/IJB-2019-0088 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Lee ET, Welty TK, Fabsitz R, et al. The Strong Heart Study. A study of cardiovascular disease in American Indians: design and methods. Am J Epidemiol. 1990;132(6):1141–1155. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/pubmed/2260546. Accessed April 5, 2018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.gtex-pipeline/rnaseq at master · broadinstitute/gtex-pipeline · GitHub. https://github.com/broadinstitute/gtex-pipeline/tree/master/rnaseq. Accessed February 11, 2022.

- 26.Zou H, Hao A, Zhang H. ON THE ADAPTIVE ELASTIC-NET WITH A DIVERGING NUMBER OF PARAMETERS. Ann Stat. 2009;37(4):1733–1751. doi: 10.1214/08-AOS625 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Barfield RT, Almli LM, Kilaru V, et al. Accounting for Population Stratification in DNA Methylation Studies. Genet Epidemiol. 2014;38(3):231. doi: 10.1002/GEPI.21789 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Rhoades DA, Farley J, Schwartz SM, et al. Cancer mortality in a population-based cohort of American Indians – The strong heart study. Cancer Epidemiol. 2021;74:101978. doi: 10.1016/J.CANEP.2021.101978 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lange T, Hansen JV. Direct and Indirect Effects in a Survival Context. Epidemiology. 2011;22(4):575–581. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0b013e31821c680c [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Huanga YT, Yangc HI. Causal mediation analysis of survival outcome with multiple mediators. Epidemiology. 2017;28(3):370–378. doi: 10.1097/EDE.0000000000000651 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Jiang Z, Vanderweele TJ. When Is the Difference Method Conservative for Assessing Mediation? Am J Epidemiol. 2015;182(2):105–108. doi: 10.1093/AJE/KWV059 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Shannon P, Markiel A, Ozier O, et al. Cytoscape: A software Environment for integrated models of biomolecular interaction networks. Genome Res. 2003;13(11):2498–2504. doi: 10.1101/gr.1239303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.B G, G J, M B. CluePedia Cytoscape plugin: pathway insights using integrated experimental and in silico data. Bioinformatics. 2013;29(5):661–663. doi: 10.1093/BIOINFORMATICS/BTT019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.B G, M B, H H, et al. ClueGO: a Cytoscape plug-in to decipher functionally grouped gene ontology and pathway annotation networks. Bioinformatics. 2009;25(8):1091–1093. doi: 10.1093/BIOINFORMATICS/BTP101 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Luo C, Fa B, Yan Y, et al. High-dimensional mediation analysis in survival models. Althouse B, ed. PLOS Comput Biol. 2020;16(4):e1007768. doi: 10.1371/journal.pcbi.1007768 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Martinussen T, Vansteelandt S. On collapsibility and confounding bias in Cox and Aalen regression models. Lifetime Data Anal. 2013;19(3):279–296. doi: 10.1007/s10985-013-9242-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Kõks G, Uudelepp ML, Limbach M, Peterson P, Reimann E, Kõks S. Smoking-Induced Expression of the GPR15 Gene Indicates Its Potential Role in Chronic Inflammatory Pathologies. Am J Pathol. 2015;185(11):2898–2906. doi: 10.1016/J.AJPATH.2015.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.MAPK Cancer Pathway ∣ Genentech Oncology. https://www.genentechoncology.com/pathways/cancer-tumor-targets/mapk.html. Accessed October 30, 2022.

- 39.Xiao Y, Dong J. The Hippo Signaling Pathway in Cancer: A Cell Cycle Perspective. Cancers (Basel). 2021;13(24). doi: 10.3390/CANCERS13246214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Lee M, Rhee I. Cytokine Signaling in Tumor Progression. Immune Netw. 2017;17(4):214. doi: 10.4110/IN.2017.17.4.214 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.McLean GW, Carragher NO, Avizienyte E, Evans J, Brunton VG, Frame MC. The role of focal-adhesion kinase in cancer — a new therapeutic opportunity. Nat Rev Cancer 2005 57. 2005;5(7):505–515. doi: 10.1038/nrc1647 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Arlt A, Schäfer H. Role of the immediate early response 3 (IER3) gene in cellular stress response, inflammation and tumorigenesis. Eur J Cell Biol. 2011;90(6-7):545–552. doi: 10.1016/J.EJCB.2010.10.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wu MX. Roles of the stress-induced gene IEX-1 in regulation of cell death and oncogenesis. Apoptosis. 2003;8(1):11–18. doi: 10.1023/A:1021688600370 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Bollepalli S, Korhonen T, Kaprio J, Anders S, Ollikainen M. EpiSmokEr: A robust classifier to determine smoking status from DNA methylation data. Epigenomics. 2019;11(13):1469–1486. doi: 10.2217/epi-2019-0206 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Reynolds LM, Wan M, Ding J, et al. DNA Methylation of the Aryl Hydrocarbon Receptor Repressor Associations With Cigarette Smoking and Subclinical AtherosclerosisCLINICAL PERSPECTIVE. Circ Cardiovasc Genet. 2015;8(5):707–716. doi: 10.1161/CIRCGENETICS.115.001097 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Zhang Z, Zheng C, Kim C, Van Poucke S, Lin S, Lan P. Causal mediation analysis in the context of clinical research. Ann Transl Med. 2016;4(21):425. doi: 10.21037/atm.2016.11.11 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Wielscher M, Mandaviya PR, Kuehnel B, et al. DNA methylation signature of chronic low-grade inflammation and its role in cardio-respiratory diseases. Nat Commun 2022 131. 2022;13(1):1–14. doi: 10.1038/s41467-022-29792-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Lee J, Taneja V, Vassallo R. Cigarette Smoking and Inflammation: Cellular and Molecular Mechanisms. J Dent Res. 2012;91(2):142. doi: 10.1177/0022034511421200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.