Abstract

Background:

Verbal and visuospatial memory impairments are common to Alzheimer’s disease and Related Dementias (ADRD), but the patterns of decline in these domains may reflect genetic and lifestyle influences. The latter maybe pertinent to populations such as the Amish who have unique lifestyle experiences.

Methods:

Our dataset included 420 Amish and 401 CERAD individuals. Sex-, age-, and education-adjusted Z-scores were calculated for the recall portions of the Constructional Praxis (CPD) and Word List Learning (WLD). ANOVAs were then used to examine the main and interaction effects of cohort (Amish, CERAD), cognitive status (case, control), and sex on CPD and WLD Z-scores.

Results:

The Amish performed better on the CPD than the CERAD cohort. In addition, the difference between cases and controls on the CPD and WLD were smaller in the Amish; and Amish female cases performed better on the WLD than the CERAD female cases.

Discussion:

The Amish performed better on the CPD task, and ADRD related declines in CPD and WLD were less severe in the Amish. Additionally, Amish females with ADRD may have preferential preservation of WLD. This study provides evidence that the Amish exhibit distinct patterns of verbal and visuospatial memory loss associated with aging and ADRD.

Keywords: Visuospatial Memory, Alzheimer Disease, Amish, Verbal Memory

Introduction

Memory impairment is a defining feature of Alzheimer’s disease (AD) 1, 2. However, memory is multi-dimensional and has several domains (e.g., verbal, procedural, visuospatial, etc.). Further, age- and AD- related decline may not be uniform across the domains. The pattern of decline in the different domains of memory may be influenced by genetic factors, disease state (such as vascular dementia vs. AD), and environmental/psychosocial factors. This study will examine the patterns of decline in visuospatial memory and verbal memory in the Old Order Amish (Amish) a group characterized by reduced genetic diversity as well as more uniform environmental and psychosocial influences.

AD is commonly associated with a loss of semantic and episodic memory. Neuropsychological testing for dementia often evaluates these types of memory with verbal memory (VBM) tests that assess the ability to remember semantic information that is presented verbally. Common VBM tasks include story recall and word list learning tasks 3-6. For example, the CERAD battery contains the Word List Learning test, a 10-item word list which is read aloud to participants who then recall the words over three trials and after a short delay [Word List Delay (WLD)] 5.

In contrast to VBM, Visuospatial memory (VSM) is the ability to remember colors, form, structure, location, and spatial relations, as well as movements. At its core, VSM requires the ability to identify and remember details about the structure of forms in multiple dimensions of space. A widely used VSM task included in the CERAD neuropsychological battery is the delayed recall portion of the Constructional Praxis (CPD) test 5, 7 for which participants initially copy four shapes from stimulus cards and reproduce them from memory after a short delay during which other non-VSM tasks are administered. Visuospatial deficits are one of the first noticeable signs of AD and can often be detected in the preclinical stages of the disease 8. In addition, the extant literature suggests that sex differences exist on VSM and VBM. For instance, women tend to outperform men on VBM tasks, whereas men tend to outperform women on VSM tasks 9-11.

The patterns of decline in VSM and VBM have not been studied among older Amish individuals or Amish individuals with ADRD. However, one study found that healthy Amish individuals performed within half a standard deviation of non-Amish individuals on VBM and VSM tasks. It should be noted though that their sample consisted of individuals ranging from young adults to the elderly, and the sample size of older Amish individuals was small 12. There are, however, several genetic and non-genetic reasons that the Amish may have differing patterns of cognition in older age and ADRD compared to non-Amish populations. Cultural and religious isolation have greatly restricted the introduction of genetic variation among the Amish, who come from an isolated founder population originating from the emigration of German and Swiss Anabaptists to the U.S. in the 1700’s and 1800’s 13-15, with fewer than 1,000 founders 16. The Amish also have extensive experiences that may maintain or enhance cognitive abilities. For example, a large proportion of the Amish have occupations that heavily rely on visuospatial abilities, such as construction, craftwork, and woodwork (e.g., furniture building), as well as having high levels of physical activity and a low prevalence of obesity 17-19.

For this study, we propose that VSM is resistant to decline among the Amish, even among individuals who show significant impairments on other neuropsychological tests. Thus, we will test if VSM (using CPD) and VBM (using WLD) performance differs in older Amish individuals (both AD and cognitively unimpaired) compared to non-Amish individuals. Our primary hypothesis is that overall, our Amish participants will demonstrate better VSM relative to the CERAD participants and that Amish participants with ADRD will show less decline in VSM compared to non-Amish individuals.

Methods

Study Populations

Collaborative Amish Aging and Memory Project (CAAMP)

Participants were drawn from ongoing studies of aging and memory in the Amish communities located in Adams, Elkhart, and LaGrange counties in Indiana and Holmes County in Ohio. Participants were ascertained as previously described 13, 20, 21. All participants were administered a standard battery of neuropsychological tests including the CPD and the WLD tests 13, 20-22, which were used for categorization of cognitive status during a case conference by an adjudication panel consisting of neurologists and neuropsychologists. This cohort consists of 420 individuals between the ages of 66-101 who had complete data for the CPD and the WLD tests on the same date and had a case conference categorization of cases (ADRD) or controls (Cognitively Unimpaired); individuals who had cognitive impairment due to other reasons were excluded.

CERAD Normative Cohort

The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease (CERAD) enrolled participants from various clinical centers (CERAD centers and select Alzheimer’s Disease Research Centers) with and without Alzheimer disease from 1987 to 1995. Participants underwent clinical evaluations that included a neuropsychological assessment; the battery consisted of multiple tests including the CPD and WLD tests 5, 7. All participants were between the ages of 60 and 96 and had complete data for the CPD and the WLD tests on the same date. Participants were classified as AD cases or cognitively unimpaired controls using NINDS-ADRA criteria 5.

Constructional Praxis Test

The Constructional Praxis test 7 consists of a copy portion in which participants copy four shapes (circle, diamond, overlapping rectangles, and a cube). Reproductions are scored based on accuracy using well-defined criteria, with a total maximum score of 11 points. For the CERAD battery, the copy portion was expanded to include a delayed recall component (CPD) to better characterize VSM 5, 7, 23. For the CPD component, participants are asked to draw the four shapes from memory after a delay, and the shapes are scored using the same criteria as above, with a total maximum score of 11 points.

CERAD Word List Learning Test

The Word List Learning test consists of both immediate and delayed recall tasks 5. During the immediate recall portion of the Word List Learning test, a 10-item word list is read aloud to participants who are then asked to immediately recall the words; this is repeated twice for a total of three trials. For the delay recall portion of the Word List Learning (WLD) the participant is asked to recall the 10 words after a delay of 15 minutes. The WLD score is the number of words correctly recalled following a delay.

Data Processing

For both cohorts, education-adjusted Z-scores were calculated for the CPD test, using 10-year age group normative data from the Cache County Memory study 24. Education-adjusted Z-scores were also calculated for the WLD test, using 20-year age group normative data derived from 23 US CERAD sites and participants enrolled in an Alzheimer’s Disease Research Center study 25, 26.

Statistical Analyses

Descriptive analyses included independent t-tests to examine differences between cohorts on age, sex, and percent of cases. Univariate factorial ANOVAs were then used to examine the main and interaction effects of cohort (Amish, CERAD), cognitive status (case, control), and sex on CPD and WLD Z-scores. Pairwise comparisons with Bonferroni corrections were implemented for significant interaction effects. All analyses were conducted using IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, Version 27 (IBM SPSS Statistics for Windows, IBM Corporation, Armonk, NY).

Results

Descriptive results

Compared to the CERAD cohort, the Amish cohort contains a higher proportion of controls (t = 6.957, p < 0.001, proportional difference (PD) = 23.5%) and is older (t = 15.380, p < 0.001, mean difference (MD) = 6.68 years). The proportion of females to males is similar between the two cohorts (t = 0.094, p = 0.93, PD = 0.3%). See Table 1 for a summary of descriptive data.

Table 1.

Demographic information for Amish and CERAD cohorts

| ADRD (%) *** | Age (years) *** | Female (%) | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Amish (n = 420) | 33.6 | 81.87 + 4.50 | 61.7 |

| CERAD (n = 401) | 57.1 | 75.19 + 6.88 | 61.3 |

Note: ADRD: Alzheimer’s disease and Related Dementias

p<0.001

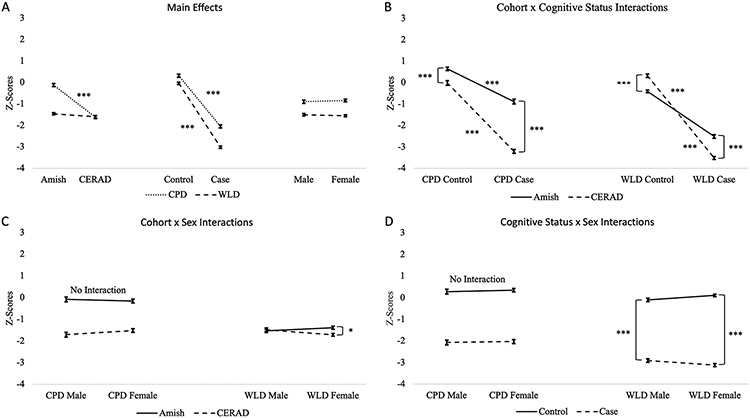

The main effects for the CPD and WLD are shown in Figure 1A. The Cohort by Cognitive Status interactions are shown in Figure 1B. The Cohort by Sex and Cognitive Status by sex interactions are shown in Figure 1C and Figure 1D.

Figure 1:

Main and Interaction Effects. Amish: Old Order Amish; CERAD: Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer’s Disease; CPD: delayed recall component of the Constructional Praxis test; WLD: delayed recall component of the Word List Learning Test; *p<0.05; ***p<0.001.

Constructional Praxis Delay (CPD)

The analysis revealed a main effect of cohort where Amish individuals had higher CPD Z-scores than CERAD individuals (F(1,813) = 229.279, p < 0.001, EMD = 1.494). There was also a main effect of cognitive status where controls had higher CPD Z-scores than cases (F(1,813) = 572.787, p < 0.001, EMD = 2.361). No main effect was found for sex (F(1,813) = 0.343, p = 0.558, EMD = 0.058). Additionally, we found a cohort by cognitive status interaction (F(1,813) = 71.309, p < 0.001) where the Amish had higher CPD Z-Scores, but the difference in CPD performance between Amish and CERAD individuals was more pronounced between the two case groups (p < 0.001, EMD = 2.327) than it was between the two control groups (p < 0.001, EMD = 0.661). Post-hoc tests also demonstrated that controls had higher CPD Z-Scores than cases in both the Amish (p < 0.001, EMD = 1.528). and CERAD (p < 0.001, EMD = 3.194) cohorts. No other interactions were significant [cohort by sex (F(1,813) = 1.791, p = 0.181), cognitive status by sex (F(1,813) = 0.020, p = 0.889), cohort by cognitive status by sex (F(1,813) = 0.397, p = 0.529)].

Word List Delay (WLD)

The analysis revealed a main effect of cognitive status where controls had higher WLD Z-scores than cases (F(1,813) = 1631.176, p < 0.001, EMD = 2.969). No main effect was found for cohort (F(1,813) = 3.557, p = 0.060, EMD = 0.139) or sex (F(1,813) = 0.367, p = 0.545, EMD = 0.045). The results also demonstrated interaction effects for cohort by cognitive status (F(1,813) = 140.037, p <0.001), cohort by sex (F(1,813) = 6.239, p = 0.013), and cognitive status by sex (F(1,813) = 5.020, p = 0.025). The 3-way cohort by cognitive status by sex interaction was not significant (F(1,813) = 0.523, p = 0.470).

For the cohort by cognitive status interaction, Amish controls had lower WLD Z-scores than CERAD controls (p < 0.001, EMD = 0.731), while Amish cases had higher WLD Z-scores than CERAD cases (p < 0.001, EMD = 1.07). Post-hoc tests also showed that controls had higher WLD Z-scores than cases for both the Amish (p < 0.001, EMD = 2.099) and CERAD (p < 0.001, EMD = 3.839) cohorts.

For the cohort by sex interaction, the Amish and CERAD males had similar WLD Z-scores (p = 1.00, EMD = 0.045), while Amish females had higher WLD Z-Scores than the CERAD females (p = 0.002, EMD = 0.322). Post-hoc tests also showed that the Amish females had slightly higher WLD Z-Scores than Amish males (p = 0.728, EMD = 0.139), and CERAD females had slightly lower Z-Scores than CERAD males (p = 0.112, EMD = 0.228). However, those differences were not statistically significant.

For the cognitive status by sex interaction, female controls had higher WLD Z-Scores than control males (p = 0.941, EMD = −0.12), and in the cases, males had higher Z-Scores than females (p = 0.201, EMD = 0.209). However, neither of these differences were statistically significant. Post hoc tests also revealed that controls had higher WLD Z-Scores than cases in both males (p < 0.001, EMD = 2.804) and females (p < 0.001, EMD = 3.134).

Discussion

As hypothesized, the Amish had higher CPD Z-Scores than CERAD individuals (both cases and controls), and there was an interaction where the difference in CPD performance between ADRD cases and controls was smaller in the Amish (EMD = 0.66) than it was in the CERAD cohort (EMD = 2.33). In addition, Amish controls had lower WLD Z-scores than CERAD controls, but like the CPD results, the interaction demonstrated a smaller difference in WLD performance between ADRD and controls in the Amish (EMD = 2.10) compared to CERAD cohort (EMD = 3.84). Further, we found a cohort by sex interaction where Amish females performed better than CERAD females on the WLD.

Overall, relative to the CERAD cohort, the Amish demonstrated superior VSM and comparable VBM. The cognitive status by cohort interactions found for both VSM and VBM showed that difference in VSM and VBM between ADRD and control individuals was smaller in the Amish cohort. Broadly, we believe these results suggest a preservation of cognitive abilities among the Amish with ADRD relative to CERAD individuals with ADRD. These findings could reflect underlying neurobiological influences (e.g., genetics) in conjunction with life experiences/psychosocial factors. For example, twin and family studies have shown that cognitive abilities both in aging and in ADRD can be partially explained by genetic heritability 27-29. Additionally, studies have suggested that cognitive processes bolstered by well-learned life experiences often show less decline 30. Genetic heritability as well as an emphasis on learning and engaging in highly relevant VSM and VBM skills (e.g., woodworking, reading) could be central to cognitive preservation among the Amish.

Overall, no main effect of sex was found between VSM or VBM in either cohort. The lack of sex differences was surprising as previous research indicates that in young healthy adults, females perform better on VBM tasks while males perform better on VSM tasks. It may be that sex differences in VSM and VBM do not generalize to older adults.

While no main effect of sex was discovered, there was a cohort by sex interaction for VBM, where CERAD females demonstrated poorer VBM than Amish females, while no differences were found between CERAD and Amish males. It is worth noting that while females tend to outperform males on VBM tasks 9-11, females with dementia typically perform worse on tasks of VBM than their male counterparts 31. Our results are suggestive of this trend in the CERAD cohort with females performing worse than males on VBM (EMD = 0.23), while an opposite trend was found in the Amish females outperforming males on VBM (EMD = 0.14). Despite a lack of statistically significant sex differences within cohorts, these results may suggest a sparing of VBM in Amish females with ADRD.

There are several reasons why the Amish might demonstrate different patterns of cognitive performance including both genetic and non-genetic factors. The Amish come from an isolated small founder population 13-15, and thus may share genetic heritability of cognitive abilities and show different patterns of age/ADRD related decline in cognition. In addition, occupational, lifestyle, and non-formal educational information may establish a cognitive reserve in the Amish. Occupations, hobbies, and life experiences that are common among the Amish (e.g., woodworking, farming, quilt making, reading) allow for additional non-formal education and practice that strengthens abilities such as VSM and VBM. This is consistent with evidence that links years of formal education with cognitive reserve, which is associated with less neurodegenerative disease 32-35.

Limitations

The current study found that VSM performance is better in older Amish adults and that they showed less decline in both VBM and VSM abilities. Nonetheless, interpretation of these results must consider that raw scores on all cognitive measures were adjusted for education with the assumption that educational attainment is comparable across the Amish and the CERAD. However, educational experiences in the Amish may be systematically different due to educational standards and cultural practices. For instance, among the Amish, 8 years of formal education is the cultural standard and is often supplemented by practical real-world experiences. Given the lack of methods to adjust for quality of education, our education adjustment is our best estimate, but further research could clarify this. Another limitation of this study is the absence APOE data for the CERAD cohort resulting in our inability to control for APOE status in the analyses. For instance, the CERAD cohort could have had a greater percentage of individuals with an APOE-e4 allele, which might explain the greater differences in performance between cases and controls. This study also had relatively small sample sizes in both the Amish and CERAD cohorts; however, the sample sizes did end up being comparable. Finally, while it is well known that Amish men and women engage in work and hobbies that consist of building things and attention to detail, we did not have sufficient individual information about work and hobbies to include in our analyses 19.

Conclusion

In summary, this study suggests that the Amish had better VSM than a non-Amish cohort, and that ADRD related decline in VSM and VBM was less severe in the Amish. Additionally, the cognitive decline associated with being female and having ADRD appeared to be diminished in the Amish. We suggest that these differences may be due to a combination of genetic as well as non-genetic (e.g., lifestyle) factors. In future studies we will investigate this phenomenon by examining other tests in the neuropsychological battery to see if the Amish demonstrate any other differences in the pattern of cognitive decline. Furthermore, we will expand our work to assess the contributions of underlying genetics and lifestyle factors with cognitive performance among Amish individuals with ADRD.

Acknowledgements

We thank the Amish families for allowing us into their communities and for participating in our study. We also acknowledge the contributions of the Anabaptist Genealogy Database and Swiss Anabaptist Genealogy Association. This study is supported by National Institutes of Health / National Institute of Aging, grant 1RF1AG058066 (to Jonathan L. Haines, Margaret Pericak-Vance, and William K. Scott). Finally, we acknowledge the resources provided by the Department of Population and Quantitative Health Sciences, School of Medicine at Case Western Reserve University and the John P. Hussman Institute for Human Genomics at University of Miami, Miller School of Medicine.

Ms. Denise Fuzzell passed away on October 28, 2022. She was an integral part of our Amish clinical team and contributed warmth, kindness, and a deep respect for her colleagues and, most importantly, the Amish community. She will be remembered and missed by all.

Conflicts of Interest and Source of Funding:

We have no conflicts of interest to report. This study is supported by National Institutes of Health / National Institute of Aging, grant R01 AG058066 (to Jonathan L. Haines, Margaret Pericak-Vance, and William K. Scott). Finally, we acknowledge the resources provided by the Department of Population and Quantitative Health Sciences, Cleveland Institute for Computational Biology, and Department of Neurology at Case Western Reserve University, as well as the John P. Hussman Institute for Human Genomics and the Dr. John T. Macdonald Foundation at University of Miami.

REFERENCES

- 1.Borelli CM, Grennan D, Muth CC. Causes of Memory Loss in Elderly Persons. JAMA. 2020;323:486. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Jahn H Memory loss in Alzheimer's disease. Dialogues Clin Neurosci. 2013;15:445–454. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bowden SC, Saklofske DH, Weiss LG. Augmenting the core battery with supplementary subtests: Wechsler adult intelligence scale--IV measurement invariance across the United States and Canada. Assessment. 2011;18:133–140. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Crossen JR, Wiens AN. Comparison of the Auditory-Verbal Learning Test (AVLT) and California Verbal Learning Test (CVLT) in a sample of normal subjects. J Clin Exp Neuropsychol. 1994;16:190–194. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Fillenbaum GG, van Belle G, Morris JC, et al. Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD): the first twenty years. Alzheimers Dement. 2008;4:96–109. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Weintraub S, Salmon D, Mercaldo N, et al. The Alzheimer's Disease Centers' Uniform Data Set (UDS): the neuropsychologic test battery. Alzheimer Dis Assoc Disord. 2009;23:91–101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Morris JC, Heyman A, Mohs RC, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD). Part I. Clinical and neuropsychological assessment of Alzheimer's disease. Neurology. 1989;39:1159–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Iachini I, Iavarone A, Senese VP, Ruotolo F, Ruggiero G. Visuospatial memory in healthy elderly, AD and MCI: a review. Curr Aging Sci. 2009;2:43–59. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Herlitz A, Nilsson LG, Backman L. Gender differences in episodic memory. Mem Cognit. 1997;25:801–811. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Herlitz A, & Rehnman J Sex differences in episodic memory. Current Directions in Psychological Science. 2008;17:52–56. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lewin C, Wolgers G, Herlitz A. Sex differences favoring women in verbal but not in visuospatial episodic memory. Neuropsychology. 2001;15:165–173. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kuehner RM, Kochunov P, Nugent KL, et al. Cognitive profiles and heritability estimates in the Old Order Amish. Psychiatr Genet. 2016;26:178–183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Hahs DW, McCauley JL, Crunk AE, et al. A genome-wide linkage analysis of dementia in the Amish. Am J Med Genet B Neuropsychiatr Genet. 2006;141B:160–166. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Hostetler J Amish Society, 4th Ed. Baltimore, MD: Johns Hopkins University Press; 1993. [Google Scholar]

- 15.van der Walt JM, Scott WK, Slifer S, et al. Maternal lineages and Alzheimer disease risk in the Old Order Amish. Hum Genet. 2005:1–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Lee WJ, Pollin TI, O'Connell JR, Agarwala R, Schaffer AA. PedHunter 2.0 and its usage to characterize the founder structure of the Old Order Amish of Lancaster County. BMC Med Genet. 2010;11:68-2350-11-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bassett DR, Schneider PL, Huntington GE. Physical activity in an Old Order Amish community. Med Sci Sports Exerc. 2004;36:79–85. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Katz ML, Ferketich AK, Broder-Oldach B, et al. Physical activity among Amish and non-Amish adults living in Ohio Appalachia. J Community Health. 2012;37:434–440. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kraybill DB, Olshan MA. The Amish Struggle with Modernity. Upne; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Edwards DR, Gilbert JR, Jiang L, et al. Successful aging shows linkage to chromosomes 6, 7, and 14 in the Amish. Ann Hum Genet. 2011;75:516–528. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Pericak-Vance MA, Johnson CC, Rimmler JB, et al. Alzheimer's disease and apolipoprotein E-4 allele in an Amish population. Ann Neurol. 1996;39:700–704. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Edwards DR, Gilbert JR, Hicks JE, et al. Linkage and association of successful aging to the 6q25 region in large Amish kindreds. Age (Dordr). 2013;35:1467–1477. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fillenbaum GG, Burchett BM, Unverzagt FW, Rexroth DF, Welsh-Bohmer K. Norms for CERAD constructional praxis recall. Clin Neuropsychol. 2011;25:1345–1358. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Welsh-Bohmer KA, Ostbye T, Sanders L, et al. Neuropsychological performance in advanced age: influences of demographic factors and Apolipoprotein E: findings from the Cache County Memory Study. Clin Neuropsychol. 2009;23:77–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Beeri MS, Schmeidler J, Sano M, et al. Age, gender, and education norms on the CERAD neuropsychological battery in the oldest old. Neurology. 2006;67:1006–1010. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Welsh KA, Butters N, Mohs RC, et al. The Consortium to Establish a Registry for Alzheimer's Disease (CERAD). Part V. A normative study of the neuropsychological battery. Neurology. 1994;44:609–614. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Reynolds CA, Finkel D. A meta-analysis of heritability of cognitive aging: minding the "missing heritability" gap. Neuropsychol Rev. 2015;25:97–112. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wilson RS, Barral S, Lee JH, et al. Heritability of different forms of memory in the Late Onset Alzheimer's Disease Family Study. J Alzheimers Dis. 2011;23:249–255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Xu C, Sun J, Duan H, et al. Gene, environment and cognitive function: a Chinese twin ageing study. Age Ageing. 2015;44:452–457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Committee on the Public Health Dimensions of Cognitive Aging, Board on Health Sciences Policy, Institute of Medicine. 2015.

- 31.Laws KR, Irvine K, Gale TM. Sex differences in Alzheimer's disease. Curr Opin Psychiatry. 2018;31:133–139. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Farfel JM, Nitrini R, Suemoto CK, et al. Very low levels of education and cognitive reserve: a clinicopathologic study. Neurology. 2013;81:650–657. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Lovden M, Fratiglioni L, Glymour MM, Lindenberger U, Tucker-Drob EM. Education and Cognitive Functioning Across the Life Span. Psychol Sci Public Interest. 2020;21:6–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Luerding R, Gebel S, Gebel EM, Schwab-Malek S, Weissert R. Influence of Formal Education on Cognitive Reserve in Patients with Multiple Sclerosis. Front Neurol. 2016;7:46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Ramos J, Chowdhury AR, Caywood LJ, et al. Lower Levels of Education Are Associated with Cognitive Impairment in the Old Order Amish. J Alzheimers Dis. 2021;79:451–458. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]