Abstract

Background:

Obesity-induced hyperglycemia is a significant risk factor for stroke. Integrin α9β1 is expressed on neutrophils and stabilizes adhesion to the endothelium via ligands, including fibronectin containing extra domain A (Fn-EDA) and tenascin C. While myeloid deletion of α9 reduces susceptibility to ischemic stroke, it is unclear whether this is mediated by neutrophil-derived α9. We determined the role of neutrophil-specific α9 in stroke outcomes in a mice model with obesity-induced hyperglycemia.

Methods:

α9Neu-KO (α9fl/flMRP8Cre+) and littermate control α9WT (α9fl/flMRP8 Cre−) mice were fed on a 60% high-fat diet for 20 weeks to induce obesity-induced hyperglycemia. Functional outcomes were evaluated up to 28 days after stroke onset in mice of both sexes using a transient (30 min) middle cerebral artery ischemia. Infarct volume (MRI) and post-reperfusion thrombo-inflammation (thrombi, fibrin, neutrophil, p-NFκB, TNFα, and IL1β levels, markers of NETs) were measured post 6 or 48 h of reperfusion. In addition, functional outcomes (mNSS, rotarod, corner, and wire-hanging test) were measured for up to 4 weeks.

Results:

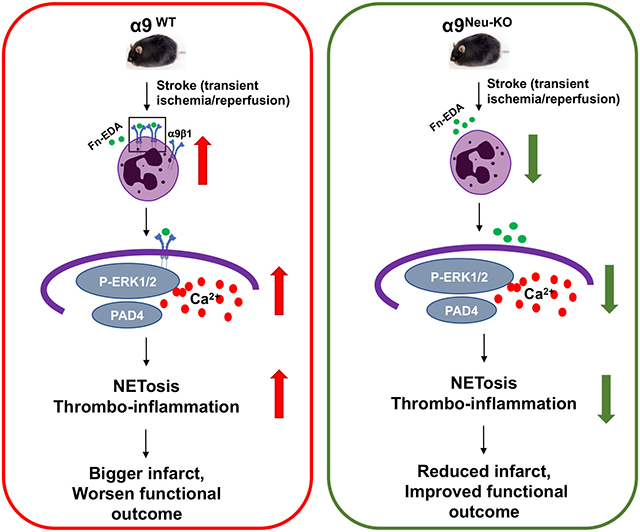

Stroke upregulated neutrophil α9 expression more in obese mice (P<0.05 vs. lean mice). Irrespective of sex, deletion of neutrophil α9 improved functional outcomes up to 4 weeks, concomitant with reduced infarct, improved cerebral blood flow, decreased post-reperfusion thrombo-inflammation, and NETosis (P<0.05 vs. α9WT obese mice). Obese α9Neu-KO mice were less susceptible to thrombosis in FeCl3 injury-induced carotid thrombosis model. Mechanistically, we found that α9/cellular fibronectin axis contributes to NETosis via ERK and PAD4, and neutrophil α9 worsens stroke outcomes via cellular fibronectin-EDA but not tenascin C. Obese wild-type mice infused with anti-integrin α9 exhibited improved functional outcomes up to 4 weeks (P<0.05 vs. vehicle).

Conclusion:

Genetic ablation of neutrophil-specific α9 or pharmacological inhibition improves long-term functional outcomes after stroke in mice with obesity-induced hyperglycemia, most likely by limiting thrombo-inflammation.

Graphical Abstract

Introduction

Stroke remains one of the leading causes of disability worldwide. Reperfusion therapy is recommended for certain patients with acute stroke and includes intravenous thrombolysis with recombinant tissue plasminogen activator or mechanical thrombectomy. Unfortunately, most patients with acute ischemic stroke cannot be treated with reperfusion therapies, and many of those treated exhibit only modest effectiveness and do not functionally recover in the long term.1 These patients may benefit from cerebroprotective therapies that can limit the infarct core, protect the stroke penumbra, and offer better functional outcomes if administered as early as possible during recanalization.

Neutrophils are among the first line of immune cells in the circulation following cerebral ischemia and play a key role in determining stroke severity. Evidence from human and experimental models suggests that ischemic brain injury and reperfusion are associated with neutrophil activation, which is known to augment cerebral injury by releasing inflammatory cytokines and free radicals.2 Recent studies have found the markers of neutrophil extracellular traps (NETs) in the infarcted tissue, thrombi, and plasma of ischemic stroke patients and mice after stroke onset.3,4 NETs contain double-stranded DNA, histones, elastase, cathepsin G, and myeloperoxidase. Targeting NETs with DNase has been shown to reduce infarction after stroke.5,6 Together, these studies suggest a pathological role of NETs in exacerbating ischemic stroke.

Integrin α9β1 is upregulated upon neutrophil activation and stabilizes neutrophil adhesion to the activated endothelium in synergy with β2 integrin.7 Till date, β1 is the only subunit of α9. Besides neutrophils, α9β1 is expressed in other cell types, including monocytes, smooth muscle, hepatocytes, endothelial, and epithelial .8 Previously, we have found that myeloid-specific α9β1 contributes to arterial thrombosis and ischemic stroke.9,10 However, the cell-specific role of neutrophil α9β1 in stroke pathogenesis remains unclear. Moreover, the mechanism by which α9β1 contributes to NETs formation (NETosis) has not been explored yet. Herein, we generated neutrophil-specific α9−/− mice to examine the role of α9β1 in NETosis and stroke pathogenesis in a mice model with obesity-induced hyperglycemia, a common comorbidity in stroke that is known to promote endothelial dysfunction, thrombo-inflammation, NETosis, and oxidative stress, thereby exacerbating stroke susceptibility. In a preclinical model of stroke, we report targeting neutrophil integrin α9 genetically or pharmacologically improves long-term functional outcomes in a mice model with obesity-induced hyperglycemia.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Detailed information on materials and methods is available in the online-only data supplement. The data supporting this study’s findings are available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Mice

The University of Iowa Animal Care and Use Committee approved all the procedures, and studies were performed according to the current Animal Research: Reporting of In Vivo Experiment guidelines (https://www.nc3rs.org.uk/arriveguidelines).

Filament model of cerebral ischemia

Transient middle cerebral artery occlusion (tMCAo) was induced by transiently occluding the right middle cerebral artery for 30 minutes. See Online Data Supplement for details.

Statistical analysis

The statistical significance was assessed using either an unpaired t-test, one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons test, or two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak’s multiple comparisons test (for normally distributed data) and Mann-Whitney test (for not normally distributed data). P<0.05 was considered to be statistically significant. See Online Data Supplement for details.

Results

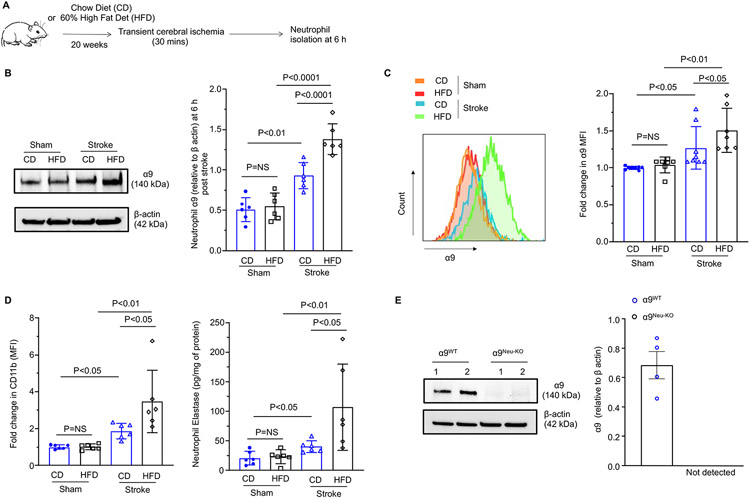

Stroke upregulates neutrophil α9 expression more in high-fat diet-fed obese mice

We first analyzed the α9 expression in neutrophils following ischemic stroke onset (Figure 1A). We selected 30 mins of ischemia because ~50% of the obese mice in pilot studies subjected to 60 mins died before 28 days (data not shown), making it difficult to study long-term functional outcomes. Western blot analysis revealed that stroke upregulates neutrophil α9 expression more (~1.5 fold) in high-fat diet-fed mice (P<0.05 vs. chow diet-fed mice, Figure 1B). In parallel, these results were confirmed by flow cytometry (Figure 1C). The upregulation of α9 was associated with increased levels of markers of neutrophil activation, including CD11b and elastase (Figure 1D). Next, we generated novel α9fl/fl Mrp8Cre+/− (neutrophil-specific α9−/− mice). Out of 8 β subunits, β1 is the only known subunit of α9; therefore, lack of α9 should completely inhibit α9β1 signaling. We did not target β1 in addition to α9 because β1 binds to several other subunits, including α4 and α5 that may confound our findings. To simplify, from herein, α9fl/fl Mrp8Cre +/− and littermate α9fl/fl Mrp8Cre−/− will be referred as α9Neu-KO and α9WT respectively. Genomic PCR confirmed the presence of the Cre gene in α9fl/fl mice (Figure S1). Western blotting confirmed α9 deficiency in neutrophils from α9Neu-KO mice (Figure 1E). Deletion of α9 did not affect the integrin subunit β1 level (Figure S2).

Figure 1: Stroke upregulated α9 expression.

(A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Representative immunoblots and densitometric analysis of α9 expression in neutrophils following stroke onset in wild-type (WT) mice fed a chow diet (CD) and high-fat diet (HFD). n=6,6. (C) Representative flow cytometry and fold change in mean fluorescence intensity (MFI) of α9 expression. n=8,7,8,7. (D) Fold change in MFI of Neutrophil CD11b (Left) and elastase level (right) following stroke onset. n=6,6,6,6. (E) Representative immunoblot of α9 from the bone-marrow-derived neutrophils of the α9WT and α9Neu-KO mice. #1 and #2 represent samples from two individual mice and β-actin as a loading control. n=4,4. Data are mean ± SD. Statistical analysis: two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparisons test (B-D). NS: non-significant.

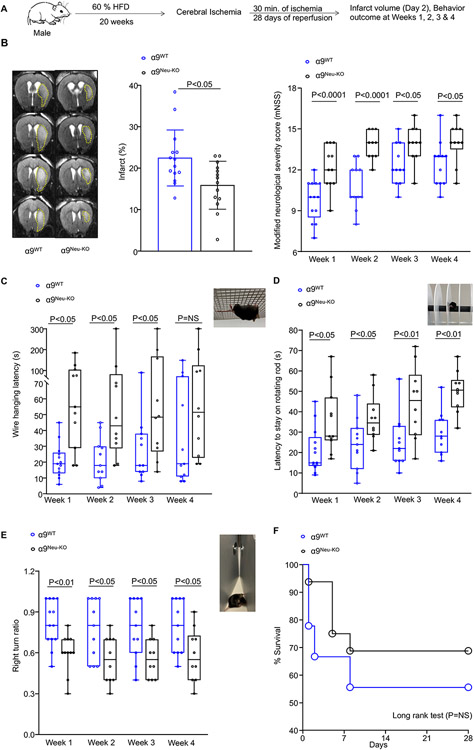

Neutrophil α9−/− obese mice exhibited reduced brain infarction and improved long-term functional outcomes

Irrespective of sex, α9Neu-KO chow-fed mice exhibited smaller infarcts on day two and improved functional outcomes (P<0.05 versus α9WT, Figure S3 & S4). Infarcts and functional outcomes were comparable between α9WT MRP8Cre+/− and α9WT mice (Figure S5), ruling out nonspecific effects of MRP8Cre recombinase expression on stroke outcome. Next, α9Neu-KO mice were fed a 60% high-fat diet for 20 weeks starting at the age of 5 weeks to induce obesity-induced hyperglycemia. Body weight gain, total and visceral fat was comparable between high-fat diet-fed α9WT and α9Neu-KO mice (Figure S6). Similar to clinical findings, we found obesity-induced hyperglycemia in high-fat diet-fed mice. Fasting glucose and insulin levels were comparable in high-fat diet-fed α9WT and α9Neu-KO mice (Figure S6). The plasma cholesterol, triglycerides, and complete blood count were comparable between groups (Table S1 & S2). Irrespective of sex, α9Neu-KO obese mice exhibited smaller infarcts on day 2 (P<0.05 versus α9WT obese mice, Figure 2B & S7B). Next, we evaluated the modified neurological severity score (mNSS) based on spontaneous activity, symmetry in limb movement, forepaw outstretching, climbing, body proprioception, and responses to vibrissae touch and motor function up to 4 weeks in the same cohort of mice. α9Neu-KO mice exhibited improved mNSS (P<0.05 versus α9WT obese mice, Figure 2B & S7B). We performed a corner test, accelerated rota-rod test, and hanging wire test to evaluate the sensorimotor outcome. α9Neu-KO male (Figure 2C-E) and female (Figure S7C-E) mice exhibited significantly improved long-term sensorimotor outcome (P<0.05 versus α9WT obese mice). Despite the better functional outcome in the α9Neu-KO mice, the mortality rate was comparable between the groups (Figure 2F & S7F). Laser Doppler flow measurements (Table S3) were similar among groups before, during, and after ischemia. No gross differences in cerebrovascular anatomy were observed between the groups (Figure S8).

Figure 2. Neutrophil-specific deletion of α9 improves stroke outcome in male obese mice.

(A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Representative T2-MRI images (left) from one mouse on day 2 and mean infarct (middle) of each genotype. White (demarcated by yellow dots) is the infarct area. n=14,14. Right: Modified Neurological Severity Score (mNSS) in the same cohort of mice up to weeks 4 (a higher score indicates a better outcome). n=13,11 (week 1) & 11,10 (week 2-4). (C-E) Sensorimotor recovery in the same cohort of mice as analyzed by motor strength in the hanging-wire test (C), fall latency in the accelerated rota-rod test (D), and right turn ratio in the corner test (E). n=13,11 (week 1) & 11,10 (week 2-4). (F) Survival (%) up to day 28. Data are mean ± SD (infarct) and median ± range (functional outcome). Statistical analysis: unpaired t-test (infarct), two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparisons test (functional outcome). The comparison of survival curves was evaluated by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. NS: non-significant.

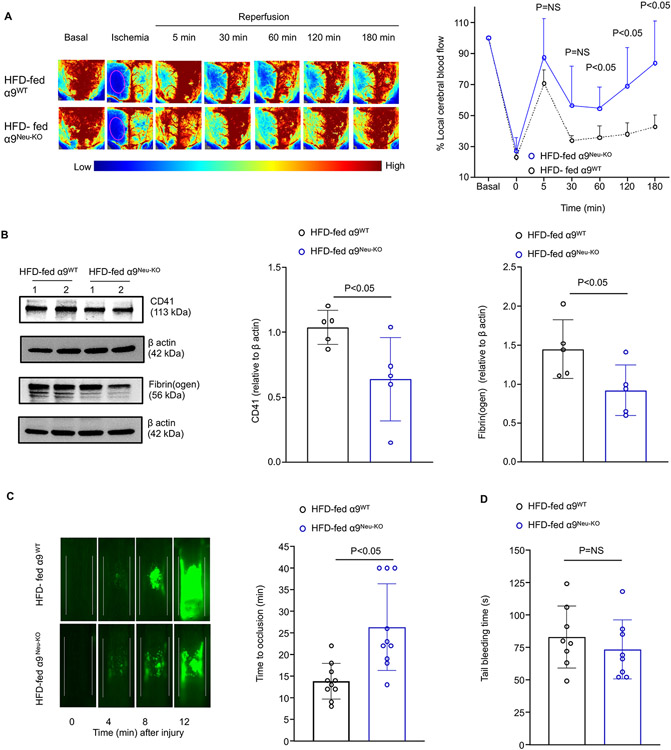

Neutrophil-specific α9−/− obese mice exhibited reduced post-ischemic thrombosis and inflammation

To determine whether improved stroke outcome in the α9Neu-KO obese mice was associated with improved local cerebral blood flow (CBF), laser speckle imaging was performed. Regional CBF was improved up to 3 hours following reperfusion in α9Neu-KO obese mice (P<0.05 versus α9WT obese mice, Figure 3A). Additionally, we observed significantly reduced intracerebral fibrin(ogen) and platelet (CD41-positive) deposition (Figure 3B) and reduced thrombotic index (Figure S9) in the α9-Neu-KO mice (P<0.05 versus α9WT obese mice). Using intravital microscopy, we found that α9Neu-KO obese mice developed smaller thrombi compared to α9WT obese mice in the FeCl3 injury-induced carotid artery thrombosis model. Furthermore, the mean time to complete occlusion was significantly prolonged in the α9-Neu-KO obese mice (Figure 3C) without altered hemostasis in the tail bleeding assay (Figure 3D). Together, these findings suggested that neutrophil α9 may potentiate thrombosis and thereby exacerbate stroke outcomes in the context of obesity.

Figure 3. Neutrophil α9−/− obese mice exhibited improved local cerebral blood flow and reduced post-ischemia/reperfusion thrombosis.

(A) Left: Representative images were taken using laser speckle imaging of the cortical region's regional cerebral blood flow (CBF). Right: Quantification at different time points. n=8,8. (B) Representative Western blots of brain homogenates and densitometric analysis of platelets (CD4-positive) and fibrin(ogen) from the infarcted and peri-infarcted areas. β-Actin was used as a loading control. n=5,5. (C) Representative microphotographs of thrombus growth in FeCl3-injured carotid arteries as visualized by upright intravital microscopy. Platelets were labeled with calcein green. White lines delineate the arteries. Right: Mean time to complete occlusion. n=10,10. (D) The tail bleeding time was determined by the time taken for the initial cessation of bleeding after transection, n=8,8. Data are mean ± SD. Statistical analysis: two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparisons test (A), Mann-Whitney test (B-D). NS: non-significant.

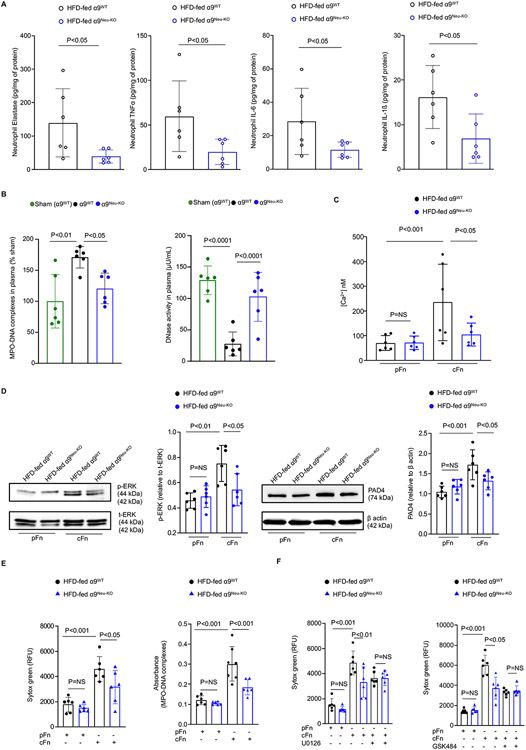

To evaluate post-cerebral ischemic reperfusion inflammation, we measured elastase and inflammatory cytokines in plasma and peripheral neutrophils, and phospho NF-κB and IL-1β within the brain homogenates from the infarct and peri-infarct area. α9Neu-KO obese mice exhibited reduced elastase levels and decreased IL6 and IL-1β levels in the plasma and peripheral neutrophils at 6-hour post-reperfusion (P<0.05 versus α9WT obese mice, Figure 4A and S10A). TNFα was decreased in peripheral neutrophils but not in the plasma of α9Neu-KO obese mice (P<0.05 versus α9WT obese mice, Figure 4A and S10A). The basal levels of elastase, TNFα, IL6, and IL-1β were comparable between neutrophils of α9Neu-KO and WT obese mice (Figure S10B). In addition, we found a reduction in phospho-NFκB p65 and IL-1β in the brain homogenates of the α9Neu-KO obese mice (P<0.05 versus α9WT obese mice, Figure S11). Furthermore, MPO-DNA complexes (a NETs marker) were reduced, whereas DNAse activity was increased in the plasma of α9Neu-KO obese mice (P<0.05 versus α9WT obese mice, Figure 4B).

Figure 4. Neutrophil-specific deletion of α9 limits post-ischemic inflammation and NETosis.

(A) Quantification of elastase, tumor necrosis factor-α (TNF-α), interleukin-1β (IL-1β), and interleukin-6 (IL-6) levels in peripheral neutrophils 6 hours post-reperfusion by ELISA. n=6,6. (B) Plasma level of MPO-DNA complexes (left) and DNase activity (middle) 6 hours post-reperfusion. n=6,6. (C) BM derived neutrophils were stimulated with pFn or cFn (20 μg/ml) for 5 mins. Fluorometric quantitation of intracellular calcium flux using Fura-2 AM loaded neutrophils. n= 6,6, 6, 6. (D) BM derived neutrophils were stimulated with pFn or cFn (20 μg/ml) for 15 min (ERK1/2) and 3 h (PAD4). Left: Representative immunoblots and densitometric analysis of p-ERK1/2 and PAD4 in neutrophils lysates. β-Actin was used as a loading control. Right: Quantification. n=6,6,6,6. (E) BM derived neutrophils were stimulated with pFn or cFn (20 μg/ml). NETosis (left) was detected by SYTOX green fluorescence. Quantification of MPO-DNA complexes (right) by ELISA. n=6,6,7,6. (F) U0126 (10 μM) (left) and GSK484 (10 μM) (right) were added 30 min before cFn incubation. NETosis was detected by SYTOX green fluorescence. n=6,6,6,6,6,6. Data are mean ± SD. Statistical analysis: unpaired t-test (A), one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett’s multiple comparisons tests (B), two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparisons test (C-F). NS: non-significant.

Neutrophil α9 and cellular fibronectin axis contribute to NETosis via ERK and PAD4

To understand the mechanism by which α9 promotes NETosis, we examined intracellular Ca2+, ERK phosphorylation, and peptidyl arginine deiminase 4 (PAD4), all known to contribute to NETosis.11,12 The cellular Fn (Fn-EDA) is a specific ligand for α9β1.13 We determined whether cFn contributes to α9β1-mediated NETosis. Neutrophils were stimulated with pFn (lacks EDA) or cFn (contains EDA). We found that cFn, but not pFn induces increase in intracellular Ca2+, ERK phosphorylation and PAD4 levels. cFn stimulated neutrophil from α9Neu-KO mice exhibited decreased intracellular Ca2+ (Figure 4C) that was associated with reduced ERK phosphorylation and PAD4 in the lysates (P<0.05 versus α9WT obese mice, Figure 4D) suggesting α9Neu-KO neutrophil exhibited reduced NETosis. These findings were confirmed in parallel by quantifying MPO-DNA complexes, a marker for NETs (Figure 4E). Neutrophils were pre-treated with U0160 (10 μM, an inhibitor of ERK pathway) and GSK484 (10 μM, an inhibitor of PAD4) for 30 min before cFn stimulation to determine the role of ERK and PAD4 in α9/Fn-EDA-mediated NETosis. U0160 and GSK484 inhibited NETosis in cFn treated α9WT neutrophils but not in cFn treated α9Neu-KO neutrophils (Figure 4F), suggesting α9/Fn-EDA axis promotes NETs formation via ERK and PAD4.

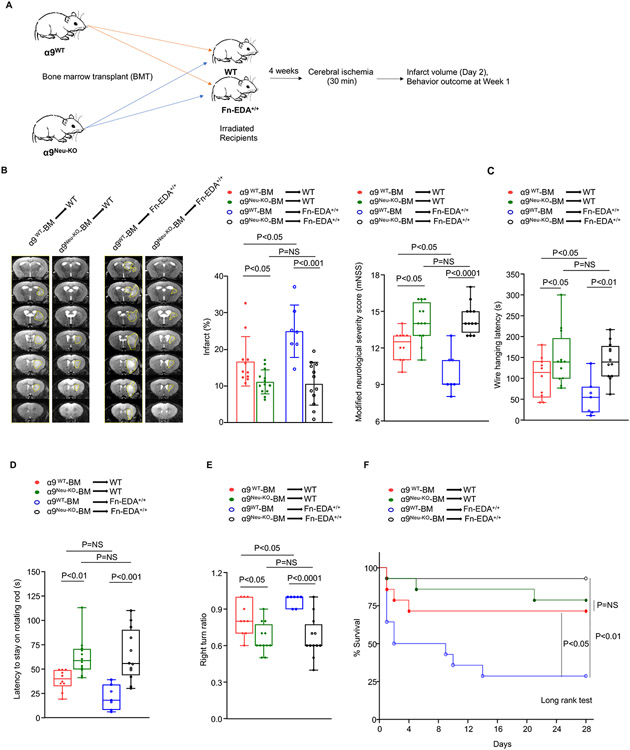

Fn-EDA contributes to neutrophil α9-mediated stroke

Previously, we have shown that extracellular matrix Fn-EDA, a specific ligand for α9β1,13 exacerbates stroke outcome.14,15 Because α9 and Fn-EDA axis promoted NETosis in vitro, we examined the contribution of Fn-EDA in α9-mediated stroke susceptibility in vivo. We transplanted obese WT or Fn-EDA+/+ mice (constitutively express Fn-EDA in plasma and tissues) with bone marrow (BM) from obese α9Neu-KO and α9WT mice (Figure 5A). The efficiency of the BM transplant procedure was checked by genotyping 4-weeks after the procedure (data not shown) and complete blood counts (Table S4). Susceptibility to stroke was evaluated in the same cohort of mice up to 28 days of reperfusion. α9WTBM→Fn-EDA+/+ mice exhibited larger infarcts and worsened functional outcomes as compared to α9WTBM→WT mice. We found significantly reduced infarcts and better functional outcomes in α9Neu-KOBM→ Fn-EDA+/+ mice compared to α9WTBM→Fn-EDA+/+ mice (Figure 5 & Figure S12). We also observed reduced infarcts and better functional outcomes in α9Neu-KOBM→WT mice compared to α9WTBM→WT mice (Figure 5 & Figure S12). However, the extent of infarct size and functional outcome were comparable between α9Neu-KOBM→WT mice and α9Neu-KOBM→ Fn-EDA+/+ mice, suggesting that Fn-EDA contributes to neutrophil α9-mediated stroke outcome. In addition to Fn-EDA, tenascin C is another ligand for integrin α9. We found that infusion of tenascin C worsens stroke outcomes in WT mice (Figure S13). To evaluate whether neutrophil- α9 contributes to stroke exacerbation via tenascin C, we infused tenascin in α9WT obese and α9Neu-KO obese mice 5 min after reperfusion. Susceptibility to stroke was evaluated in the same cohort of mice following 2 and 7 days of reperfusion. We found that elevated tenascin C levels increased infarction and worsened functional outcome in both α9Neu-KO and α9WT obese mice (P <0.05 vs. vehicle-treated mice, Figure S14), suggesting that under these experimental conditions, most likely neutrophil α9 does not exacerbate stroke via tenascin C.

Figure 5. Fn-EDA contributes to neutrophil α9-mediated stroke exacerbation in obese mice.

(A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Representative T2-MRI images (left) from one mouse of each genotype on day 2 and mean infarct (middle) of each genotype. White (demarcated by yellow dots) is the infarct area. n=11,13,7,12. Right: Modified Neurological Severity Score (mNSS) in the same cohort of mice at day 7. n=10,12,7,12. (C-E) Sensorimotor recovery in the same cohort of mice as analyzed by motor strength in the hanging-wire test (C), fall latency in the accelerated rota-rod test (D), and right turn ratio in the corner test (E). n=10,12,7,12. (F) Survival (%) up to day 28. Data are mean ± SD (infarct) and median ± range (functional outcome). Statistical analysis: two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparisons test. The comparison of survival curves was evaluated by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. NS: non-significant.

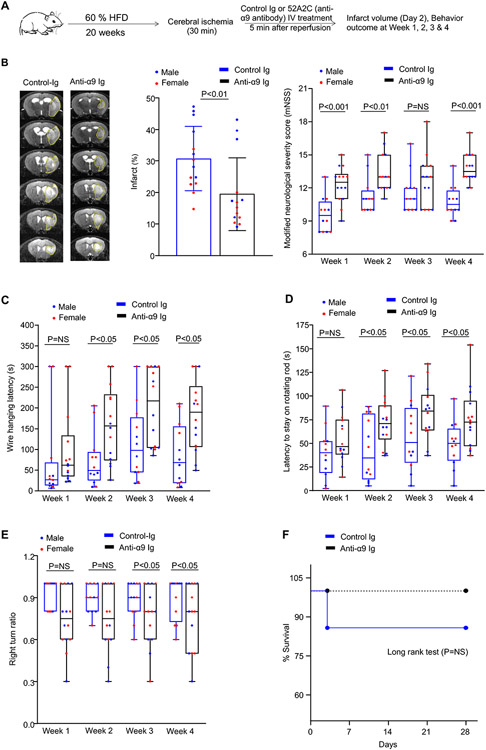

Targeting α9 with anti-α9 antibody reduces infarcts and improves long-term functional outcomes in obese mice

Next, we assessed the therapeutic efficacy of the anti-α9 antibody 55A2C16 in obesity. Obese male and female mice were randomly assigned to receive 55A2C or control Ig, and susceptibility to stroke was evaluated in tMCAo model (Figure 6A). Treatments were performed 5 minutes post-reperfusion. A significant reduction of infarct area (Figure 6B) and improved functional outcomes were observed in anti-integrin α9 antibody-treated mice compared to control Ig-treated mice (Figure 6 B-E). The mortality rate did not differ between the groups (Figure 6F). Infarct size and functional outcome were comparable in anti-integrin α9 antibody and control Ig treated α9Neu-KO obese mice (Figure S15), suggesting that no off-target effects and most likely anti-integrin α9 improve stroke outcomes by inhibiting neutrophil α9.

Figure 6. Anti-integrin α9 antibody-treated obese mice exhibited improved long-term stroke outcomes.

(A) Schematic of experimental design. (B) Representative T2-MRI from one mouse of each group on day 2 (left) and corrected mean infarct of each genotype (middle). White (demarcated by yellow dots) is the infarct area. n=14,14. Modified Neurological Severity Score (mNSS) in the same cohort of mice up to weeks 4 (right) n=12,14. (C-E) Sensorimotor recovery in the same cohort mice as analyzed by motor strength in the hanging-wire test (C), fall latency in the accelerated rota-rod test (D), and right turn ratio in the corner test (E). n=12,14. (F) Survival rates up to day 28. Data are represented as mean ± SD (infarct) and median ± range (functional outcome). Statistical analysis: unpaired t-test (infarct area), two-way ANOVA followed by Holm-Sidak multiple comparisons test (functional outcome). The comparison of survival curves was evaluated by the log-rank (Mantel-Cox) test. NS: non-significant.

Discussion

While many therapeutic interventions following reperfusion have shown efficacy in preclinical studies, they have failed in clinical trials. This is likely multifactorial, including the complexity of human stroke and the use of healthy rodents devoid of preexisting comorbidities despite the relevance of factors such as obesity-induced hyperglycemia, hypertension, sex, and age, in influencing human stroke outcomes. Herein, we report that deletion of neutrophil-specific integrin α9β1 improved long-term functional outcomes in preexisting comorbidity obesity-induced hyperglycemia. We believe that these findings may have clinical significance for the following reasons. First, we show that ischemic stroke upregulates α9 expression more on peripheral neutrophils in obesity-induced hyperglycemia. Second, we provide genetic evidence that neutrophil α9 exacerbates stroke in a model of obesity-induced hyperglycemia by promoting NETosis and thrombo-inflammation. Third, as a translational potential, treatment with a blocking anti-integrin α9 antibody exhibited improved functional outcomes for up to 4 weeks in obese mice following stroke onset. These findings suggest a previously unidentified role for neutrophil-derived α9β1 in regulating post-stroke NETosis and thrombo-inflammation and an opportunity for therapeutic intervention.

Previously, we have reported that myeloid-specific α9−/− mice have improved stroke outcomes in a model of hyperlipidemia.10 Although this study suggests a role for α9 in stroke pathogenesis, whether α9 contributes to stroke in a preexisting comorbidity obesity-induced hyperglycemia was not explored. Herein, we provide definitive evidence that neutrophil α9 contributes to stroke pathogenesis in a mice model of obesity-induced hyperglycemia. There are several murine models of obesity, including monogenic, polygenic, genetically modified, and high-fat diets.17 The widely used is monogenic ob/ob with a mutation in the leptin gene that results in hyperphagia with a low energy expense. The ob/ob mice exhibit impaired glucose tolerance, insulin sensitivity, high levels of corticosterone, and dyslipidemia and are difficult to breed because of infertility due to hypogonadism. We chose the high fat diet-induced obese model over ob/ob mice because it resembles humans in terms of the development of a metabolic syndrome resulting in obese phenotype, with increased hyperglycemia, insulin resistance, hyperlipidemia, and hypertension. Additionally, it is devoid of any genetic manipulation. Weight gain by diet also results in endothelium dysfunction and defects in neuronal response to negative feedback signals from circulating insulin. Insulin resistance results in an increased cellular inflammatory response, thus increasing sensitivity to stroke. On the other hand, despite obesity remaining an independent risk factor for stroke, its influence on clinical and functional outcomes and mortality in human ischemic stroke remains debatable. Several studies report a reduced mortality rate in obese or overweight patients with a better functional outcome, also known as the “obesity paradox”. However, several methodological concerns exist. For example, the studies reporting the “obesity paradox” were observational without a controlled randomized trial and did not adjust for stroke severity, the primary determinant for mortality and clinical prognosis (reviewed).18 When adjusted for stroke severity, the initial association between body weight and better outcomes disappeared.19 Additionally, obese patients were younger and treated aggressively with antithrombotic, antihypertensive drugs and statins, which may result in treatment bias between lean versus obese patients.18 Other studies reported a lack of “obesity paradox” after intravenous thrombolysis.20,21

The injury severity and functional outcome positively correlate with increased neutrophil infiltration in human stroke.2,22 Neutrophils aggravate stroke by several mechanisms, including releasing proteases, reactive oxygen species, proinflammatory factors, thrombosis, and NETs. Herein, we observed that the deletion of neutrophil α9 limits post-ischemic thrombosis that was associated with decreased intracerebral fibrin(ogen) and platelet deposition. Indeed, neutrophil-specific integrin α9−/− obese mice were less susceptible to experimental arterial thrombosis. Furthermore, we observed that deletion of α9 in neutrophils limits inflammatory response (reduced TNF-α, IL-1β, and IL-6) following stroke onset. TNF-α and IL-1β enhance leukocyte migration to the ischemic region, promote necrosis, increase endothelial dysfunction, disrupt the blood-brain barrier, and increase edema formation following stroke.23 High level of IL-6 in stroke patients is known to be associated with early neurological deterioration and poor outcomes after cerebral infarction.24 To our surprise, we found that α9 deletion in neutrophils reduced markers for NETosis, including DNA-MPO complexes and elastase associated with elevated DNase activity suggesting α9 promotes NETosis. Reduced DNase activity and elevated MPO-DNA complexes3, myeloperoxidase, and elastase5,25 are known to be correlated positively with stroke exacerbation.

We demonstrate mechanistically that the α9β1/cFn axis is a novel pathway contributing to NETosis via ERK and PAD4. We found reduced intracellular calcium and PAD4 levels in cFn -stimulated neutrophils of α9−/− mice. PAD4 plays a key role in NETosis and is regulated by increased intracellular calcium.12,26,27 In addition to PAD4, the ERK pathway is implicated in NETosis.11 Integrins regulate ERK signaling by binding to extracellular stimuli such as adhesion to the extracellular matrix or growth factors. α9β1 engagement activates the ERK signaling pathway in human neutrophils and delays apoptosis.28 Delay in neutrophil apoptosis was associated with enhanced NETosis in a disease model of cystic fibrosis.29 Herein, we found reduced pERK levels in cFn-stimulated neutrophils of α9−/− mice. Furthermore, inhibitor experiments with U0160 and GSK484 suggested α9/cFn axis promotes NETs formation via ERK and PAD4. Based on these studies, we speculate that integrin α9β1 engagement with cFn activates ERK signaling, which delays apoptosis allowing neutrophils to enhance NETosis via PAD4. Our results in neutrophils agree with other studies that have suggested that α9β1 engagement with cFn (Fn-EDA) results in the activation of the ERK pathway in cancer and smooth muscle cells.30,31 Although these studies suggest a role of ERK and PAD4 in regulating α9β1/cFn-mediated NETosis, the possibility of other calcium-dependent kinases cannot be ruled out.

We also investigated the possible molecular ligand by which neutrophil α9β1 promotes stroke exacerbation. α9β1 interacts with ligands, including vascular cell adhesion protein 1 (VCAM-1), osteopontin, tenascin- C, and Fn-EDA. Unlike other integrins that recognize RGD sequences, α9β1 recognizes several non-RGD sequences, including SVVYGLR in osteopontin, AEIDGIEL in tenascin-C, and EDGIHEL in Fn-EDA. Targeting VCAM1 does not protect against ischemic stroke.32 Tenascin C is proinflammatory,33 and targeting tenascin C with siRNA improved stroke outcome in the tMCAo model.34 In line with this study, increased tenascin C levels exacerbated stroke outcomes in wild-type obese mice. However, tenascin C did not mediate α9β1-mediated stroke exacerbation in obese mice. α9β1 recognizes non-RGD sequences within Fn-EDA, which is prothrombotic and proinflammatory,35-37 and is known to contribute to stroke exacerbation.14 Using a BMT approach, we observed that Fn-EDA contributes to α9β1-mediated stroke exacerbation.

Currently, no effective adjunct therapies can limit brain damage in ischemic stroke patients following reperfusion, either by thrombolytic or thrombectomy. A particular strength of the study is that we included biological variables, sex, and comorbidity of obesity-induced hyperglycemia known to influence stroke patients’ outcomes. As a translational potential, we demonstrated that targeting α9 with a blocking antibody improves long-term functional outcomes. Despite the strength, our study has limitations. We used a filament model of stroke, which limits the observed beneficial effect to this particular model but not to the embolic clot model with thrombolysis. Still, the filament model replicates mechanical thrombectomy in stroke patients and is widely used for preclinical assessment. Another limitation is that other cell types express α9β1 and possible physiological side effects with the long-term use of an inhibitor. We speculate that such a scenario is unlikely because of the single bolus treatment of anti-integrin α9 antibody. In conclusion, we identified neutrophil-specific integrin α9β1 as a novel regulator of NETosis and thrombo-inflammation in the stroke setting. Further studies are warranted to test the efficacy of integrin α9 antibody in other stroke models as an adjunct therapy in combination with thrombolysis or thrombectomy as a potential treatment for stroke patients.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank Shigeyuki Kon for providing integrin α9 antibody. RBP, AKC conceptualization, designing the experiments, and writing. RBP, ND, BS, MG, PD, TB and MK performed the experiments: EL, Intellectual input and editing: AKC, Funding acquisition, and Supervision. All authors reviewed, edited, and approved the manuscript.

Sources of Funding:

The AKC lab is supported by National Institutes of Health grants (R35HL139926, R01NS109910 & U01NS130587).

Non-standard Abbreviations and Acronyms

- Fn-EDA

Fibronectin containing extra domain A

- NETs

Neutrophil extracellular traps

- mNSS

modified Neurological Severity score

- tMCAo

transient Middle Cerebral Artery occlusion

- BMT

Bone marrow transplant

- PAD4

peptidyl arginine deiminase 4

- CBF

cerebral blood flow

Footnotes

Disclosures

None.

References

- 1.Bhatia R, Hill MD, Shobha N, Menon B, Bal S, Kochar P, Watson T, Goyal M, Demchuk AM. Low rates of acute recanalization with intravenous recombinant tissue plasminogen activator in ischemic stroke: real-world experience and a call for action. Stroke. 2010;41:2254–2258. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.592535 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Aronowski J, Roy-O'Reilly MA. Neutrophils, the Felons of the Brain. Stroke. 2019;50:e42–e43. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.118.021563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Denorme F, Portier I, Rustad JL, Cody MJ, de Araujo CV, Hoki C, Alexander MD, Grandhi R, Dyer MR, Neal MD, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps regulate ischemic stroke brain injury. J Clin Invest. 2022;132. doi: 10.1172/JCI154225 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Valles J, Lago A, Santos MT, Latorre AM, Tembl JI, Salom JB, Nieves C, Moscardo A. Neutrophil extracellular traps are increased in patients with acute ischemic stroke: prognostic significance. Thromb Haemost. 2017;117:1919–1929. doi: 10.1160/TH17-02-0130 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Kang L, Yu H, Yang X, Zhu Y, Bai X, Wang R, Cao Y, Xu H, Luo H, Lu L, et al. Neutrophil extracellular traps released by neutrophils impair revascularization and vascular remodeling after stroke. Nat Commun. 2020;11:2488. doi: 10.1038/s41467-020-16191-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Meyer SF, Suidan GL, Fuchs TA, Monestier M, Wagner DD. Extracellular chromatin is an important mediator of ischemic stroke in mice. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2012;32:1884–1891. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.112.250993 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Mambole A, Bigot S, Baruch D, Lesavre P, Halbwachs-Mecarelli L. Human neutrophil integrin alpha9beta1: up-regulation by cell activation and synergy with beta2 integrins during adhesion to endothelium under flow. J Leukoc Biol. 2010;88:321–327. doi: 10.1189/jlb.1009704 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Palmer EL, Ruegg C, Ferrando R, Pytela R, Sheppard D. Sequence and tissue distribution of the integrin alpha 9 subunit, a novel partner of beta 1 that is widely distributed in epithelia and muscle. J Cell Biol. 1993;123:1289–1297. doi: 10.1083/jcb.123.5.1289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Dhanesha N, Nayak MK, Doddapattar P, Jain M, Flora GD, Kon S, Chauhan AK. Targeting myeloid-cell specific integrin alpha9beta1 inhibits arterial thrombosis in mice. Blood. 2020;135:857–861. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019002846 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dhanesha N, Jain M, Tripathi AK, Doddapattar P, Chorawala M, Bathla G, Nayak MK, Ghatge M, Lentz SR, Kon S, et al. Targeting Myeloid-Specific Integrin alpha9beta1 Improves Short- and Long-Term Stroke Outcomes in Murine Models With Preexisting Comorbidities by Limiting Thrombosis and Inflammation. Circ Res. 2020;126:1779–1794. doi: 10.1161/CIRCRESAHA.120.316659 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Hakkim A, Fuchs TA, Martinez NE, Hess S, Prinz H, Zychlinsky A, Waldmann H. Activation of the Raf-MEK-ERK pathway is required for neutrophil extracellular trap formation. Nat Chem Biol. 2011;7:75–77. doi: 10.1038/nchembio.496 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Li P, Li M, Lindberg MR, Kennett MJ, Xiong N, Wang Y. PAD4 is essential for antibacterial innate immunity mediated by neutrophil extracellular traps. J Exp Med. 2010;207:1853–1862. doi: 10.1084/jem.20100239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Liao YF, Gotwals PJ, Koteliansky VE, Sheppard D, Van De Water L. The EIIIA segment of fibronectin is a ligand for integrins alpha 9beta 1 and alpha 4beta 1 providing a novel mechanism for regulating cell adhesion by alternative splicing. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:14467–14474. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M201100200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dhanesha N, Ahmad A, Prakash P, Doddapattar P, Lentz SR, Chauhan AK. Genetic Ablation of Extra Domain A of Fibronectin in Hypercholesterolemic Mice Improves Stroke Outcome by Reducing Thrombo-Inflammation. Circulation. 2015;132:2237–2247. doi: 10.1161/CIRCULATIONAHA.115.016540 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khan MM, Gandhi C, Chauhan N, Stevens JW, Motto DG, Lentz SR, Chauhan AK. Alternatively-spliced extra domain A of fibronectin promotes acute inflammation and brain injury after cerebral ischemia in mice. Stroke. 2012;43:1376–1382. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.111.635516 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Kon S, Uede T. The role of alpha9beta1 integrin and its ligands in the development of autoimmune diseases. J Cell Commun Signal. 2018;12:333–342. doi: 10.1007/s12079-017-0413-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lutz TA, Woods SC. Overview of animal models of obesity. Curr Protoc Pharmacol. 2012;Chapter 5:Unit 5 61. doi: 10.1002/0471141755.ph0561s58 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Oesch L, Tatlisumak T, Arnold M, Sarikaya H. Obesity paradox in stroke - Myth or reality? A systematic review. PLoS One. 2017;12:e0171334. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171334 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Kim Y, Kim CK, Jung S, Yoon BW, Lee SH. Obesity-stroke paradox and initial neurological severity. J Neurol Neurosurg Psychiatry. 2015;86:743–747. doi: 10.1136/jnnp-2014-308664 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sarikaya H, Elmas F, Arnold M, Georgiadis D, Baumgartner RW. Impact of obesity on stroke outcome after intravenous thrombolysis. Stroke. 2011;42:2330–2332. doi: 10.1161/STROKEAHA.110.599613 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Seet RC, Zhang Y, Wijdicks EF, Rabinstein AA. Thrombolysis outcomes among obese and overweight stroke patients: an age- and National Institutes of Health Stroke Scale-matched comparison. J Stroke Cerebrovasc Dis. 2014;23:1–6. doi: 10.1016/j.jstrokecerebrovasdis.2012.04.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Akopov SE, Simonian NA, Grigorian GS. Dynamics of polymorphonuclear leukocyte accumulation in acute cerebral infarction and their correlation with brain tissue damage. Stroke. 1996;27:1739–1743. doi: 10.1161/01.str.27.10.1739 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Lambertsen KL, Biber K, Finsen B. Inflammatory cytokines in experimental and human stroke. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2012;32:1677–1698. doi: 10.1038/jcbfm.2012.88 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Acalovschi D, Wiest T, Hartmann M, Farahmi M, Mansmann U, Auffarth GU, Grau AJ, Green FR, Grond-Ginsbach C, Schwaninger M. Multiple levels of regulation of the interleukin-6 system in stroke. Stroke. 2003;34:1864–1869. doi: 10.1161/01.STR.0000079815.38626.44 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Laridan E, Denorme F, Desender L, Francois O, Andersson T, Deckmyn H, Vanhoorelbeke K, De Meyer SF. Neutrophil extracellular traps in ischemic stroke thrombi. Ann Neurol. 2017;82:223–232. doi: 10.1002/ana.24993 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gupta AK, Giaglis S, Hasler P, Hahn S. Efficient neutrophil extracellular trap induction requires mobilization of both intracellular and extracellular calcium pools and is modulated by cyclosporine A. PLoS One. 2014;9:e97088. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0097088 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Wong SL, Wagner DD. Peptidylarginine deiminase 4: a nuclear button triggering neutrophil extracellular traps in inflammatory diseases and aging. FASEB J. 2018;32:fj201800691R. doi: 10.1096/fj.201800691R [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Saldanha-Gama RF, Moraes JA, Mariano-Oliveira A, Coelho AL, Walsh EM, Marcinkiewicz C, Barja-Fidalgo C. alpha(9)beta(1) integrin engagement inhibits neutrophil spontaneous apoptosis: involvement of Bcl-2 family members. Biochim Biophys Acta. 2010;1803:848–857. doi: 10.1016/j.bbamcr.2010.03.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Gray RD, Hardisty G, Regan KH, Smith M, Robb CT, Duffin R, Mackellar A, Felton JM, Paemka L, McCullagh BN, et al. Delayed neutrophil apoptosis enhances NET formation in cystic fibrosis. Thorax. 2018;73:134–144. doi: 10.1136/thoraxjnl-2017-210134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Jain M, Dev R, Doddapattar P, Kon S, Dhanesha N, Chauhan AK. Integrin alpha9 regulates smooth muscle cell phenotype switching and vascular remodeling. JCI Insight. 2021;6. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.147134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ou J, Deng J, Wei X, Xie G, Zhou R, Yu L, Liang H. Fibronectin extra domain A (EDA) sustains CD133(+)/CD44(+) subpopulation of colorectal cancer cells. Stem Cell Res. 2013;11:820–833. doi: 10.1016/j.scr.2013.05.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Justicia C, Martin A, Rojas S, Gironella M, Cervera A, Panes J, Chamorro A, Planas AM. Anti-VCAM-1 antibodies did not protect against ischemic damage either in rats or in mice. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2006;26:421–432. doi: 10.1038/sj.jcbfm.9600198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Midwood K, Sacre S, Piccinini AM, Inglis J, Trebaul A, Chan E, Drexler S, Sofat N, Kashiwagi M, Orend G, et al. Tenascin-C is an endogenous activator of Toll-like receptor 4 that is essential for maintaining inflammation in arthritic joint disease. Nat Med. 2009;15:774–780. doi: 10.1038/nm.1987 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Chelluboina B, Chokkalla AK, Mehta SL, Morris-Blanco KC, Bathula S, Sankar S, Park JS, Vemuganti R. Tenascin-C induction exacerbates post-stroke brain damage. J Cereb Blood Flow Metab. 2022;42:253–263. doi: 10.1177/0271678X211056392 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chauhan AK, Kisucka J, Cozzi MR, Walsh MT, Moretti FA, Battiston M, Mazzucato M, De Marco L, Baralle FE, Wagner DD, et al. Prothrombotic effects of fibronectin isoforms containing the EDA domain. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2008;28:296–301. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.107.149146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Doddapattar P, Gandhi C, Prakash P, Dhanesha N, Grumbach IM, Dailey ME, Lentz SR, Chauhan AK. Fibronectin Splicing Variants Containing Extra Domain A Promote Atherosclerosis in Mice Through Toll-Like Receptor 4. Arteriosclerosis, thrombosis, and vascular biology. 2015;35:2391–2400. doi: 10.1161/ATVBAHA.115.306474 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Prakash P, Kulkarni PP, Lentz SR, Chauhan AK. Cellular fibronectin containing extra domain A promotes arterial thrombosis in mice through platelet Toll-like receptor 4. Blood. 2015;125:3164–3172. doi: 10.1182/blood-2014-10-608653 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.