Abstract

Background:

Positive thoughts and emotions contribute to overall psychological health in diverse medical populations, including patients undergoing HSCT. However, there have been minimal studies that describe positive psychological well-being (e.g., optimism, gratitude, flourishing) in patients undergoing HSCT using well-established, validated patient-reported outcome measures.

Methods:

We conducted a cross-sectional secondary analyses of baseline data in 156 patients at 100 days post-HSCT enrolled in a randomized controlled trial of a psychological intervention (NCT05147311) and a prospective study assessing medication adherence at a tertiary care academic cancer center, from September 2021 to December 2022. We used descriptive statistics to outline participant reports of positive psychological well-being (PPWB) using validated measures for optimism, gratitude, positive affect, life satisfaction, and flourishing.

Results:

Participants had a mean (standard deviation) age of 57.4 (13.1) years, and 51% of participants were male (n=79). Many, but not all, participants reported high levels of PPWB (i.e., optimism, gratitude, positive affect, life satisfaction, and flourishing), defined as agreement with items on a given PPWB measure. For example, for optimism, 29% of participants did not agree that “overall, I expect more good things to happen to me than bad.” Aside from life satisfaction, mean PPWB scores in the HSCT population were higher than in other illness populations.

Conclusions:

Although many patients with hematologic malignancies undergoing HSCT report high levels of PPWB, a substantial minority of patients reported low PPWB (i.e., no agreement with items on a given PPWB measure). Because PPWB is associated with important clinical outcomes in medical populations, further research should determine whether an intervention to promote PPWB can improve quality of life in HSCT recipients.

Keywords: Positive Psychological Well–Being, positive psychology, well–being, hematopoietic stem cell transplantation, Psycho-Oncology

Introduction

Psychological health is vital to every aspect of care and recovery for patients undergoing hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (HSCT). However, patients undergoing HSCT experience significant levels of distress characterized by depression, anxiety, post-traumatic stress, and difficulties with adjustment.1 Additionally, very few studies show patients undergoing HSCT also report low levels of positive psychological well-being (PPWB) at different stages of the transplant care continuum.2 PPWB constitutes the positive thoughts, feelings, and strategies individuals use to appraise their lives and function well.3 High levels of distress and low levels of PPWB adversely impact clinical outcomes (e.g., quality of life [QOL], mortality).4,5,6 However, low PPWB is not the same as high levels of distress.7,8 Diverse PPWB constructs including optimism, gratitude, positive affect, life satisfaction, and flourishing are crucial to overall psychological health independent of the impact of distress.3,9,10

PPWB has not been studied extensively in the HSCT population. Indeed, most of the literature describing psychological well-being in the HSCT population focuses on distress. Existing interventions to accentuate psychological health in this population also primarily aim to mitigate the negative consequences of distress symptoms, with minimal emphasis on PPWB. However, a few studies show PPWB’s association with important clinical outcomes similar to other serious illness populations, including better immune response characterized by improved day-to-neutrophil engraftment and less mortality.11,12 Since PPWB is associated with enhanced QOL, better engagement in health behaviors such as medication adherence and moderate to vigorous physical activity, and lower mortality rates, in various medical populations,3,9,13–15 a nuanced understanding of PPWB among HSCT survivors will guide the development of tailored interventions that holistically enhance well-being in this population.

Patients undergoing HSCT have described PPWB during transplant hospitalization and in the first 100-days post-HSCT16 Also, few existing studies examine PPWB as part of other constructs such as spiritual well-being or with non-validated questions in the HSCT population.17–19 However, systematic and quantitative assessments for PPWB using established measures of these constructs across the continuum of care of HSCT are lacking.2 Accordingly, in this study, we examined various PPWB constructs such as optimism, gratitude, positive affect, satisfaction with life, and flourishing in HSCT recipients using well-validated patient-reported outcome measures for PPWB.

Methods

Study Procedure

Cross-sectional secondary analyses (N=156) of data in a randomized controlled trial (N=70) of a positive psychology intervention trial (NCT05147311) and a prospective study (N=86) assessing medication adherence in patients undergoing HSCT at the Dana-Farber Cancer Institute, Boston, MA, from September 2021 to December 2022 were analyzed. The Dana-Faber/Harvard Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approved these studies. All participants provided written or verbal informed consent and completed identical measures of positive psychological constructs at approximately 100 days post-transplant, which allowed us to combine data from the two studies. For the randomized controlled trial, we used only baseline data for this secondary analysis, preventing the need to account for random assignment to the positive psychology intervention.

Participants

Adults (≥18 years of age) with hematologic malignancies undergoing allogeneic HSCT who were approximately 100 days (+/− 10 days) post-HSCT were eligible for both studies. Participants were also required to speak English with the ability to read and complete surveys with minimal assistance. Patients were excluded if their transplant oncologist thought a history of serious mental illness or comorbid disease would interfere with their ability to successfully complete informed consent and study procedures.

Sociodemographic and Clinical Data

Participants provided demographic information, including age, sex, gender, race, ethnicity, gender, relationship status, religious beliefs, education, and income at enrollment. We obtained disease and treatment information with the electronic health record.

Patient-Reported Measures for Positive Psychological Well-Being

We used the 10-item Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R) to measure dispositional (trait) optimism (Cronbach’s alpha=0.874). Scores range from 0–24, and higher scores indicate greater optimism.20

We used the 6-item Gratitude Questionnaire (GQ-6) to measure dispositional gratitude (Cronbach’s alpha=0.735); scores range from 6–42, and higher scores indicate greater proneness to experience gratitude in daily life.21

We used the 10-item positive affect scale of the Positive and Negative Affect Scale (PANAS) to measure positive affect (Cronbach’s alpha=0.919); scores range from 10–50, and higher scores indicate greater positive affect.22

We used the 5-item Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS) to measure satisfaction with life (Cronbach’s alpha=0.893); scores range from 5–35, and higher scores indicate greater satisfaction with life.23

We used the 8-item Flourishing Scale (FS) to assess a person’s self-perceived success in critical areas such as engagement, relationships, self-esteem, meaning & purpose, and optimism (Cronbach’s alpha=0.867); scores range from 8–56, and higher scores indicate many psychological resources and strengths.24

Comparison of positive psychological well-being in HSCT with other medical samples

To compare the mean score of PPWB constructs of our study sample to other medical populations, we conducted a scoping review of the literature to identify studies that used the same validated measures in general representative samples with chronic conditions. Unfortunately, studies with large representative samples of oncology and HSCT populations which assessed PPWB are lacking so we settled on the following chronic disease populations where PPWB has been studied: cardiac disease, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, major neurocognitive impairment, and mood disorders. The general healthy population mean scores for 1) optimism, life satisfaction, and positive affect were obtained from studies published from the 2004–2006 midlife in the United States (MIDUS),25 2) gratitude was obtained from Grateful Disposition Study Dataset,21 and 3) flourishing was obtained from the New Zealand Sovereign Well-being Index study which assessed the psychometric properties of the Flourishing Scale and a nationally representative dataset.26 When multiple potential studies were available for medical or healthy populations, we prioritized studies with 1) samples with a similar mean age as our sample and 2) samples in the United States or Western countries. Since we did not have the actual data from the respective studies, we only descriptively compared the mean scores without a comprehensive analysis of raw data.

Statistical analysis

We used STATA 17.0 (StataCorp, College Station, TX) to complete all statistical analyses. Descriptive statistics (i.e., proportions for categorical variables and mean/standard deviation for continuous variables) were used to outline participant characteristics and to describe the distribution of PPWB constructs via self-report measures.

Data Sharing

Please contact hermioni_amonoo@dfci.harvard.edu for original data.

Results

Participant and Sociodemographic Characteristics

We summarize participants’ baseline characteristics in Table 1. Most participants were White (n=141; 91.0%), non-Hispanic (n=146; 93.6%), married (n=113; 72.9%), with a mean (standard deviation [SD]) age of 57.4 (13.1) years. Approximately half the sample (n=79; 51.0%) were male, 40.6% (n=63) were Catholic Christian, 27.1% (n=42) were college educated, and 49.7% (n=77) were not working due to illness or were on disability. Most of the participants (n=95; 61.3%) had leukemia, underwent reduced intensity conditioning (n=99; 63.9%), and had no acute graft-versus-host disease (GVHD: n=128; 82.6%).

Table1.

Participant Characteristics

| Total N=156 | |

|---|---|

| Age, median (Interquartile Range) | 61 (28, 73) |

| Sex, n (%) | |

| Female | 74 (47.4%) |

| Male | 79 (50.6%) |

| Missing | 3 (1.9%) |

| Race, n (%) | |

| Asian/Asian Background | 6 (3.8%) |

| Black | 1 (0.6%) |

| Middle Eastern | 1 (0.6%) |

| Native American/Indigenous | 2 (1.3%) |

| White | 141 (90.4%) |

| Other | 2 (1.3%) |

| Missing | 3 (1.9%) |

| Relationship Status, n (%) | |

| Single | 21 (13.5%) |

| Relationship/Not living together | 7 (4.5%) |

| Married/Living Together | 113 (72.4%) |

| Separated/Divorced | 7 (4.5%) |

| Widowed/Loss of Partner | 5 (3.2%) |

| Missing | 3 (1.9%) |

| Ethnicity, n (%) | |

| Not Hispanic or Latinx | 146 (93.6%) |

| Hispanic or Latinx | 7 (4.5%) |

| Missing | 3 (1.9%) |

| Religion, n (%) | |

| Agnostic | 13 (8.3%) |

| Atheist | 9 (5.8%) |

| Buddhist | 5 (3.2%) |

| Catholic Christian | 63 (40.4%) |

| Other Christian | 32 (20.5%) |

| Hindu | 1 (0.6%) |

| Jewish | 12 (7.7%) |

| None | 11 (7.1%) |

| Other | 5 (3.2%) |

| Missing | 5 (3.2%) |

| Education, n (%) | |

| < High School Diploma | 2 (1.3%) |

| High School Diploma (GED) | 19 (12.2%) |

| Some College | 41 (26.3%) |

| College | 42 (26.9%) |

| Some Postgraduate/Professional Education | 13 (8.3%) |

| Post-Graduate/Professional | 36 (23.1%) |

| Missing | 3 (1.9%) |

| Employment, n (%) | |

| Employed | 22 (14.1%) |

| Unemployed | 1 (0.6%) |

| Disability | 77 (49.4%) |

| Retired | 51 (32.7%) |

| Student | 1 (0.6%) |

| Other | 1 (0.6%) |

| Missing | 3 (1.9%) |

| Income, n (%) | |

| <$25,000 | 8 (11.8%) |

| $25,000–$49,999 | 6 (8.8%) |

| $50,000–$74,999 | 10 (14.7%) |

| $75,000–$99,999 | 10 (14.7%) |

| $100,000–149,999 | 14 (20.6%) |

| >$150,000 | 20 (29.4%) |

| Type of Cancer, n (%) | |

| Leukemia | 96 (61.5%) |

| Lymphoma | 12 (7.7%) |

| Myeloproliferative/Myelodysplastic Neoplasms | 43 (27.6%) |

| Other | 4 (2.6%) |

| Missing | 1 (0.6%) |

| Conditioning Regimen, n (%) | |

| Myeloablative Conditioning | 56 (35.9%) |

| Reduced Intensity Conditioning | 99 (63.5%) |

| Missing | 1 (0.6%) |

| Total Body Radiation, n (%) | |

| No | 129 (82.7%) |

| Yes | 26 (16.7%) |

| Missing | 1 (0.6%) |

| Donor Source, n (%) | |

| Matched | 137 (87.8%) |

| Mismatched | 18 (11.5%) |

| Missing | 1 (0.6%) |

| Acute Graft-versus-host Disease, n (%) | |

| No | 128 (82.1%) |

| Yes | 27 (17.3%) |

| Missing | 1 (0.6%) |

| Graft-versus-host Disease Prophylaxis, n (%) | |

| None | 1 (0.6%) |

| Cyclophosphamide-Based | 40 (25.6%) |

| Tacrolimus-Based | 114 (73.1%) |

| Missing | 1 (0.6%) |

Details for Other: Race (option not listed × 2), Religion (none x5),

Employment (option not listed), Type of Cancer (Aplastic Anemia x1, Red Cell Aplasiax1,

Beta Thalassemia Major x1, Refractory Anemia with Ringed Sideroblasts x1)

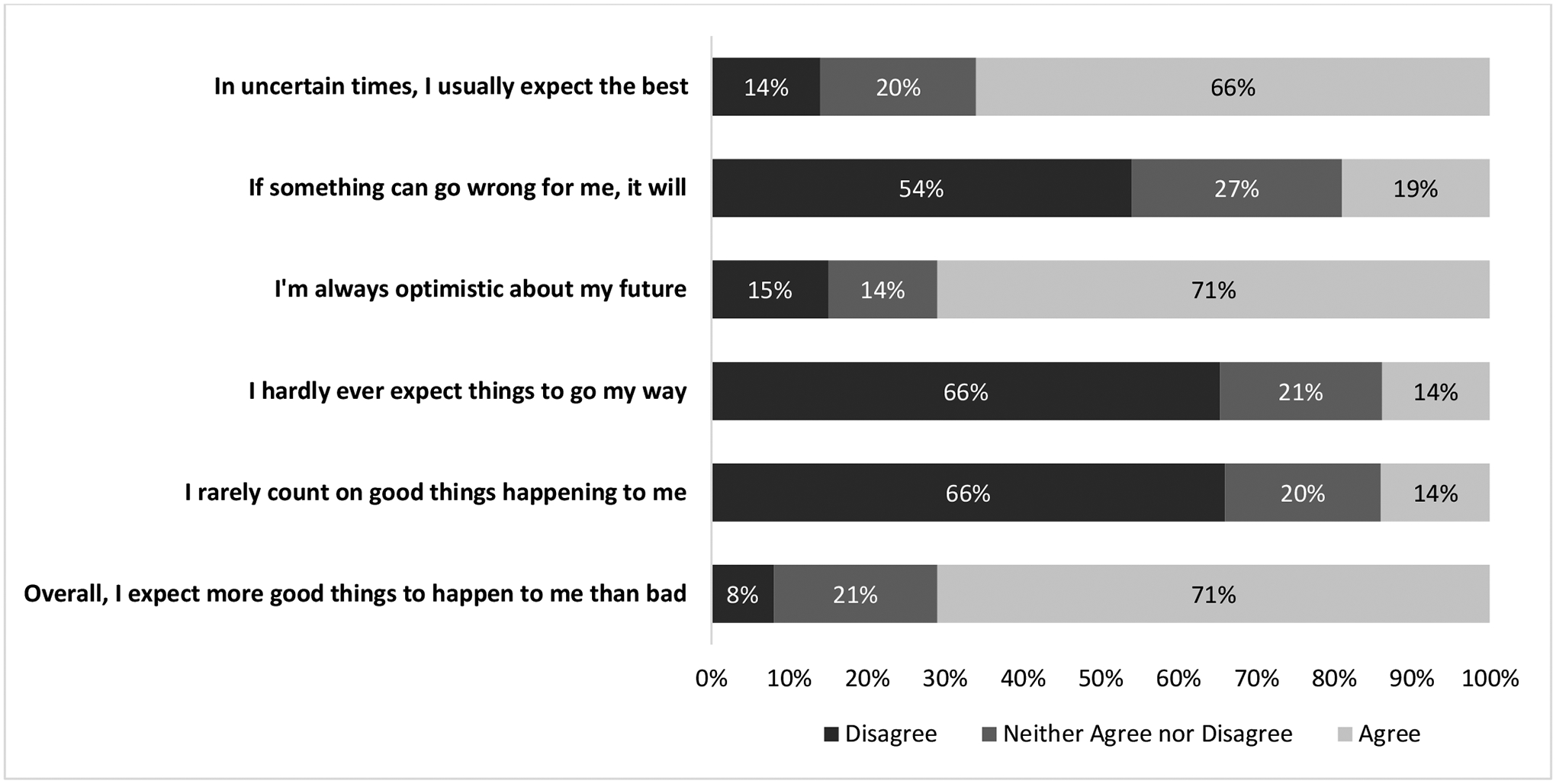

Optimism

The mean (SD) score of optimism via the LOT-R in our cohort was 17.4 (5.5). Although many participants reported optimistic thoughts and experiences defined by the specific questions in the LOT-R, approximately a third of the cohort disagreed with several items in the LOT-R (Figure 1). For example, 29% of participants did not agree that “overall, I expect more good things to happen to me than bad,” and 29% of participants did not agree that “I am always optimistic about the future.”

Figure 1.

Optimism from Life Orientation Test-Revised Questionnaire (N=154)

This figure provides a distribution of participants report of optimism via their responses to the Life Orientation Test-Revised (LOT-R) Questionnaire, a validated measure for dispositional optimism. The four distractor questions were not included.

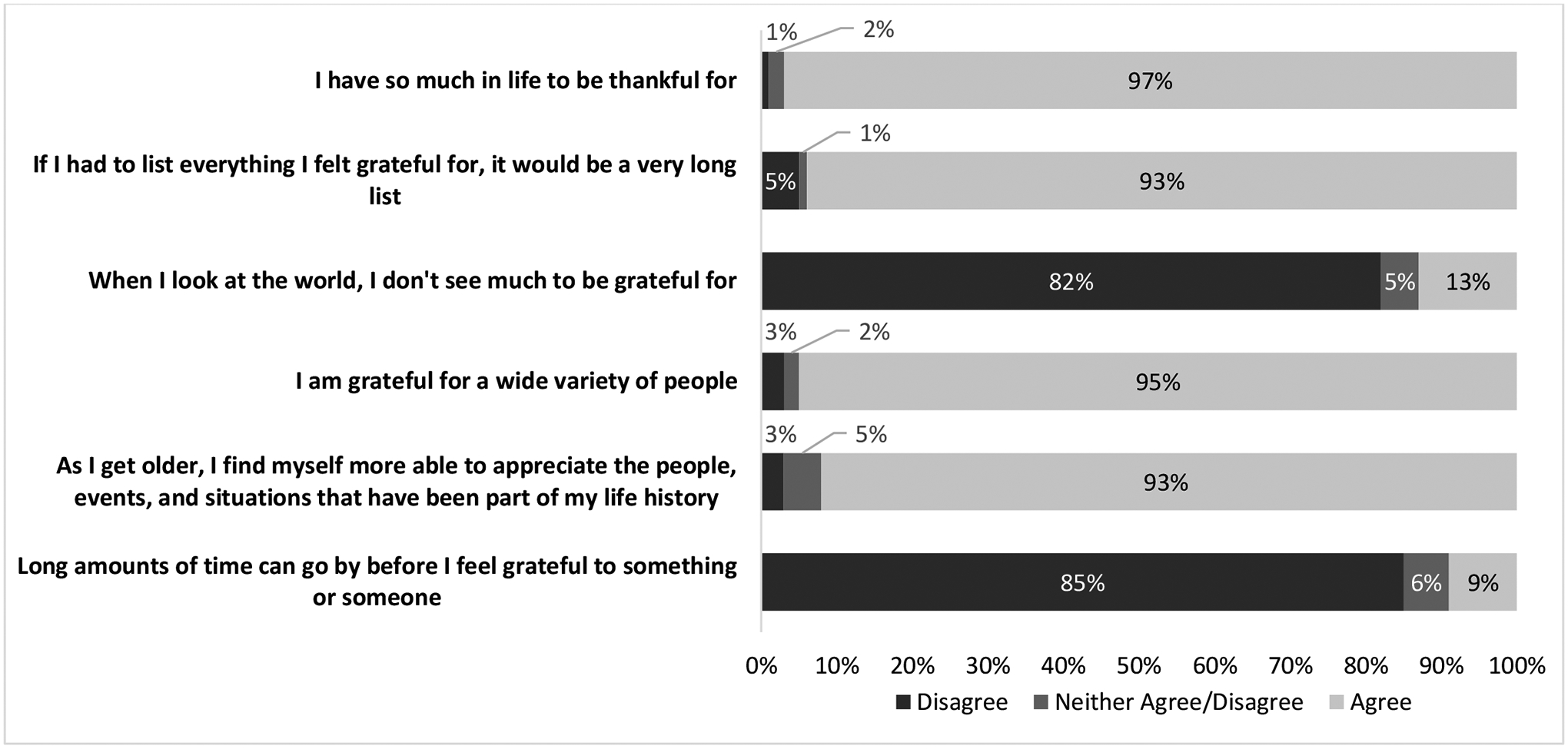

Gratitude

The mean (SD) score of gratitude via the GQ-6 in our cohort was 37.5 (5.5). Most participants reported thoughts and feelings of gratitude as defined by questions in the GQ-6. For example, 97% of our cohort agreed with the statement “I have so much in life to be thankful for,” and 95% agreed with “I am grateful for a wide variety of people” (Figure 2).

Figure 2.

Gratitude from Gratitude Questionnaire-6 (N=150)

This figure provides a distribution of participants report of gratitude via their responses to the Gratitude Questionnaire-6 (GQ-6), a validated measure for dispositional gratitude.

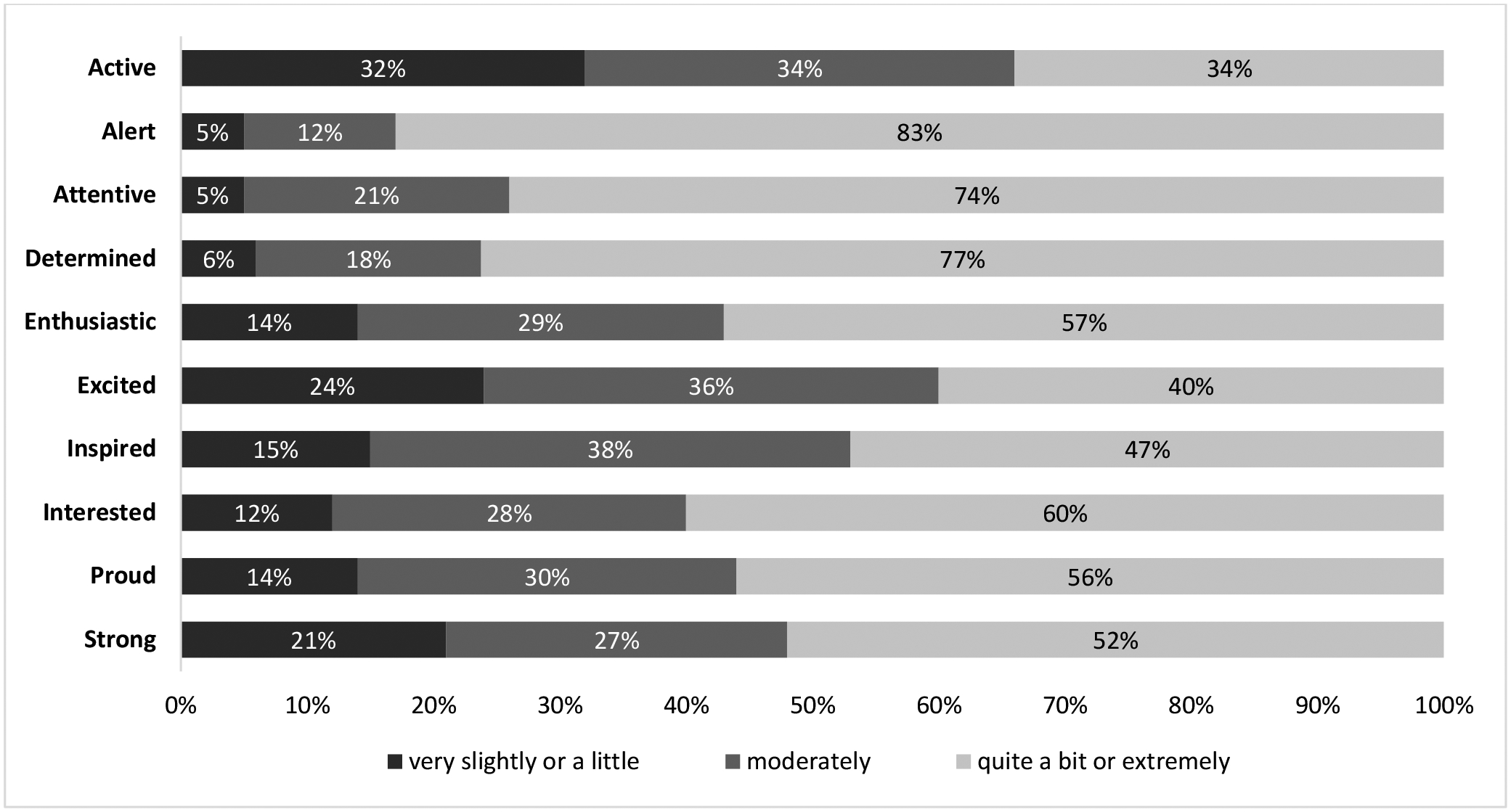

Positive Affect

The mean (SD) score of positive affect via the PANAS in our cohort was 35.6 (8.2). A higher proportion of participants reported they were quite a bit or extremely “determined” (77%), “attentive” (74%), “alert” (83%), and “interested” (60%). However, only 47%, 40%, and 34% reported quite a bit or extremely “inspired,” “excited,” and “active;” see Figure 3.

Figure 3.

Positive Affect from the Positive Affect Scale (N=154)

This figure provides a distribution of participants report of positive affect via their responses to the Positive Affective Scale (PANAS), a validated measure for trait positive affect.

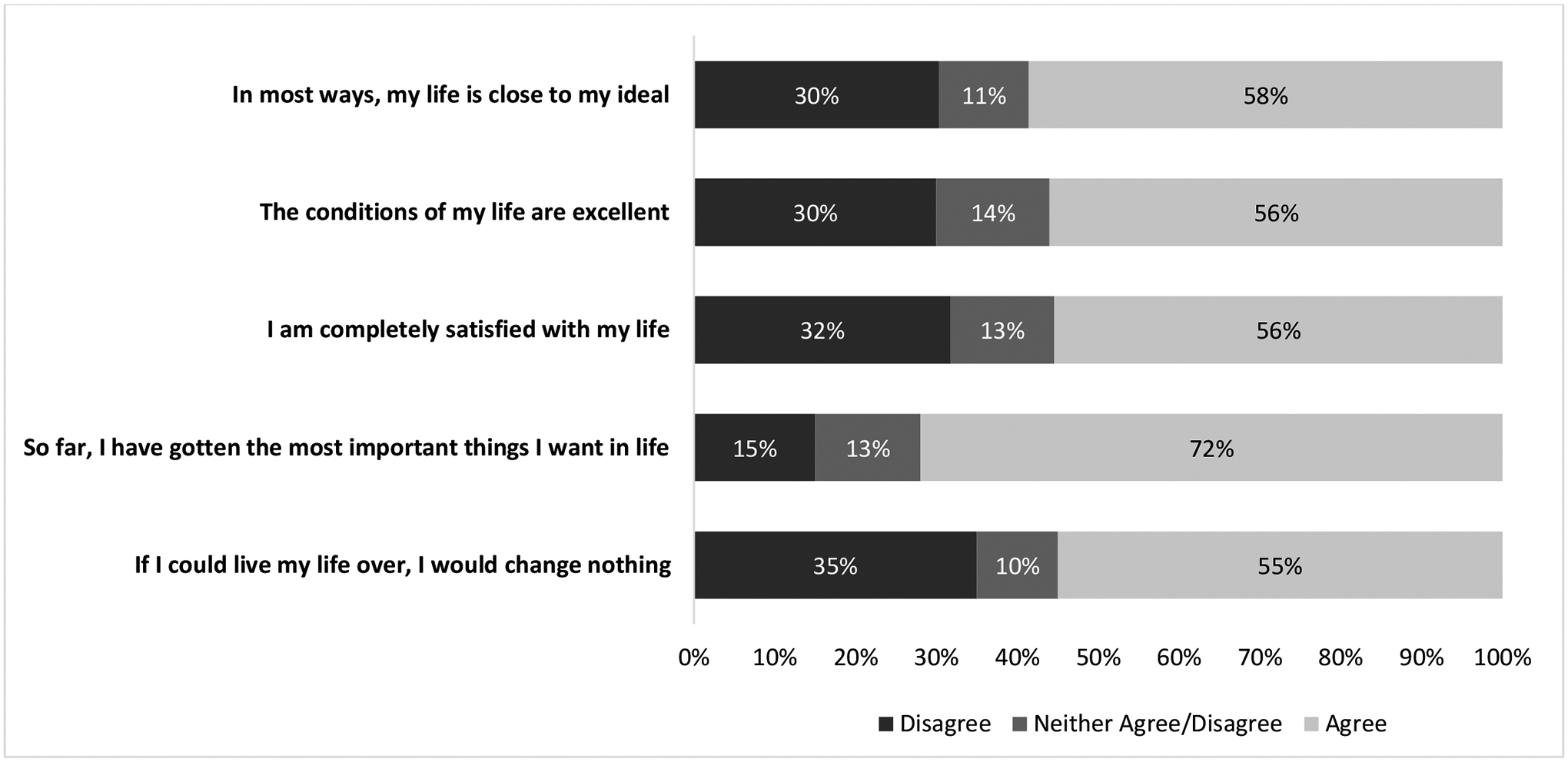

Satisfaction with Life

The mean (SD) score of satisfaction via the SWLS in our cohort was 23.5 (7.3). Over 40% of participants did not agree with questions that reflected satisfaction with life. For example, 45% did not agree that “if I could live my life over, I would change nothing,” and 44% did not agree that “I am completely satisfied with my life” (Figure 4).

Figure 4.

Life Satisfaction from Satisfaction with Life Scale (N=149)

This figure provides a distribution of participants report of life satisfaction via their responses to the Satisfaction with Life Scale (SWLS), a validated measure for dispositional life satisfaction.

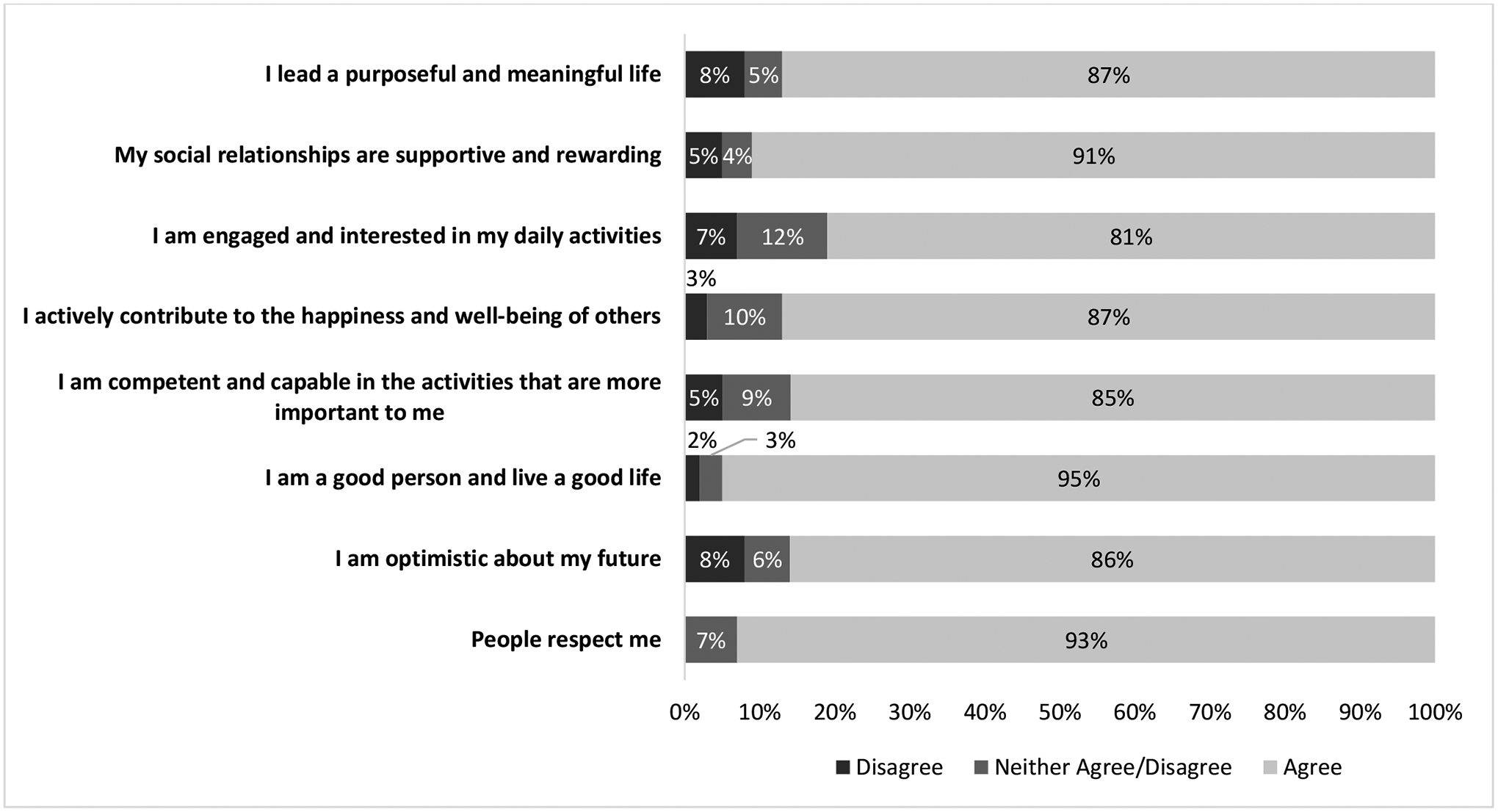

Flourishing

The mean (SD) score of flourishing via the Flourishing Scale in our cohort was 49.9 (8.4). The majority of our cohort agreed with all the items on the flourishing scale. Of all measures, the flourishing scale was the only one with an appreciable ceiling effect, with at least 80% of our cohort agreeing with all the items. For example, 95% agreed that “I am a good person and live a good life,” and 91% agreed that “my social relationships are supportive and rewarding” (Figure 5).

Figure 5.

Flourishing from the Flourishing Scale (N=150)

This figure provides a distribution of participants report of flourishing via their responses to the Flourishing scale, a validated measure for trait flourishing.

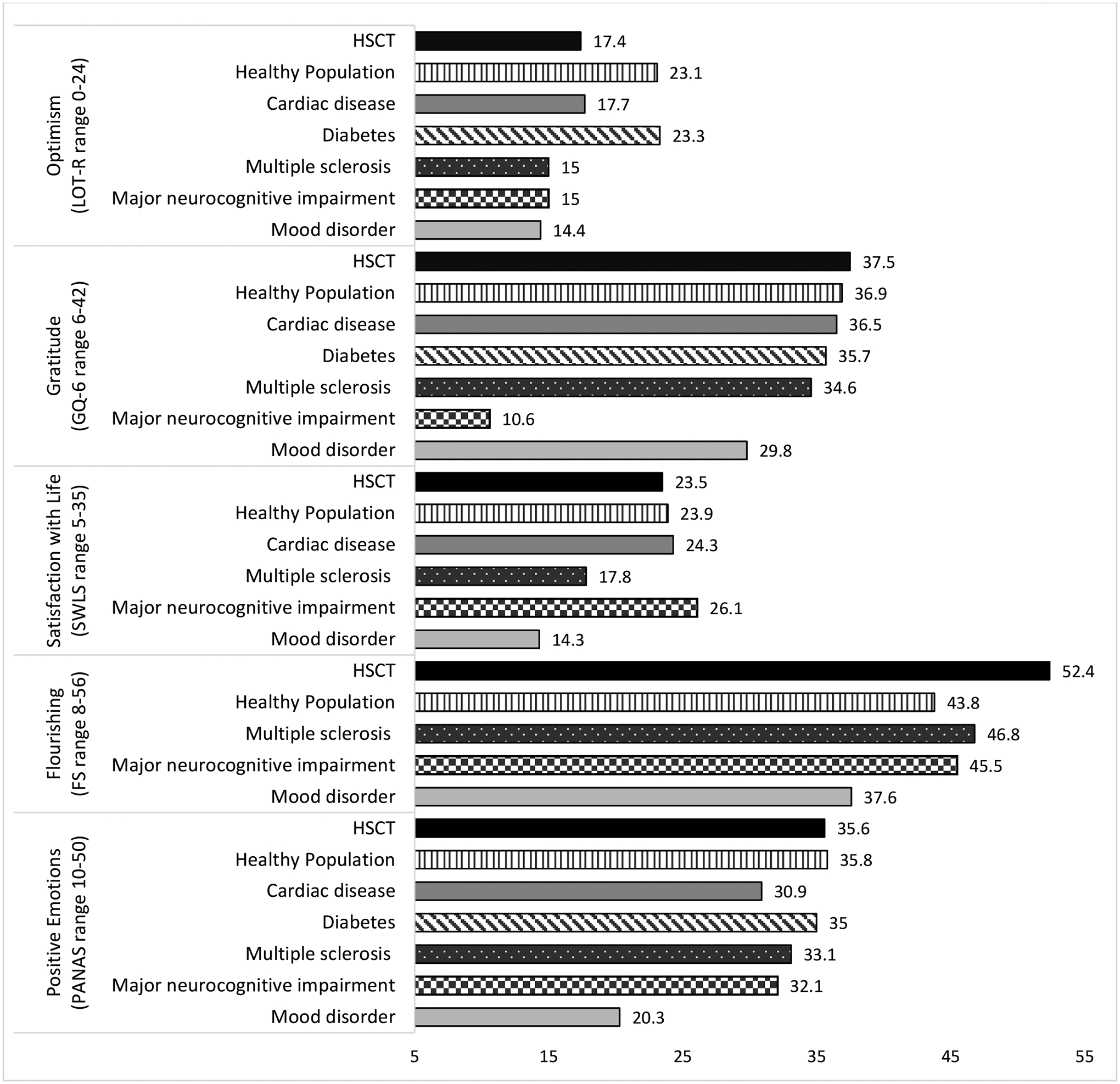

Comparison of positive psychological well-being in HSCT with other medical samples

Supplemental Table 1 provides detailed information (e.g., sample size, mean age, country) on the comparator populations, including sample size and demographic information. Figure 6 shows our cohort’s mean score of PPWB constructs and that of a descriptive comparison of other chronic medical samples. Among trait PPWB constructs (i.e., optimism, gratitude, and life satisfaction),25,27–30 gratitude (GQ-6) was the only construct with higher reported mean scores in HSCT recipients compared to all comparator samples.21,31–35 On the contrary, our cohort’s optimism score [LOT-R: 7.4 (5.5)] was lower than the healthy population mean score (23.1 [4.8]) and that of patients with diabetes (23.3 [4.8]) but higher than the mean score for patients with a mood disorder (14.4 [6.6]) or patients with multiple sclerosis (15.0 [3.5]).25,29,31,35–37 Among state PPWB constructs (i.e., positive affect and flourishing), the mean score for flourishing (FS scores)38–41 was higher among HSCT recipients compared to comparator samples. However, the mean score for positive affect reported by our cohort [35.6 (8.20)] was comparable to that of the healthy population mean score (35.8 [7.5]) and patients with diabetes (35.0 [5.7]) but higher than the mean score for patients with multiple sclerosis (33.1 [8.1]), see supplemental table.25,35–37,42,43

Figure 6:

HSCT Positive Psychology Measure Means Compared to Other Samples

This figure shows a descriptive comparison of mean scores of positive psychological well-being constructs of patients undergoing HSCT and that of other chronic medical populations.

Discussion

This is among the first studies to describe the spectrum of PPWB in patients with hematologic malignancies undergoing HSCT using well-established, validated PPWB measures for medical populations but has not been extensively used in the HSCT population. Many patients in our cohort reported high levels of PPWB characterized by optimism, gratitude, positive affect, life satisfaction, and flourishing. Compared with a healthy population and other medical samples (i.e., cardiac disease, diabetes, multiple sclerosis, mood disorder, and major neurocognitive impairment), the mean scores for gratitude and flourishing were higher in our cohort and showed trends toward greater PPWB in several other domains. However, a substantial minority of patients in our cohort did not report high levels of PPWB and may benefit from supportive interventions which promote PPWB, given the links between PPWB and clinical outcomes (e.g., quality of life [QOL]).4,5,6

Although no longitudinal studies describe PPWB over the continuum of care for patients undergoing HSCT, PPWB may evolve over the course of HSCT as symptom burden evolves and immune reconstitution improves throughout HSCT and recovery. For example, in a study of 313 patients preparing to undergo HSCT, 44% reported having optimistic expectations,44 while >65% of our cohort at 100-day post-HSCT reported high optimism. For some patients, at 100 days post-HSCT, the worst symptom burden may be behind them, catalyzing higher levels of PPWB in that context. Hence, the 100-day post-HSCT assessment of PPWB may be relevant compared to patients at different time points of their transplantation and recovery. More longitudinal studies are needed to describe how PPWB evolves in the HSCT population to inform the timing of interventions to best support patients who are at risk of low levels of PPWB and its adverse associations with clinical outcomes.

Our findings are consistent with patients’ qualitative reports of positive experiences during the HSCT hospitalization and in the first 100 days post-HSCT.16 Additionally, our cohort had higher mean gratitude and flourishing scores than our comparator medical samples. While a ceiling effect could explain the high scores on the GQ-6 and FS compared to other medical samples,45,46 it is possible that the curative intent of HSCT influences patients’ level of gratitude (i.e., towards donors and caregivers essential to recovery in required isolation)16 and sense of flourishing compared to other medical populations without curative treatment options. Life-threatening experiences, including treatments like HSCT, can sometimes cause individuals to be more purposeful in things that bring meaning which contributes to flourishing, defined as “being happy, having meaning and purpose, being “a good person,” and having fulfilling relationships.”47 In contrast to gratitude and flourishing, a high minority of patients reported low levels of life satisfaction. Further, compared with other medical samples, our cohort’s average scores for life satisfaction were lower. Life satisfaction, a global evaluation of the degree to which a person positively evaluates the overall quality of their life as a whole, is associated with clinical outcomes.48,49 Since life satisfaction entails connection with others, social support, and engaging in meaningful activities,48,50 the prolonged isolation, which accompanies HSCT and recovery, likely negatively impacts patients’ evaluation of life satisfaction. Hence, prospective studies which assess the gamut of PPWB in this population and their association with clinical outcomes such as QOL will provide us with an understanding of the benefits of improving PPWB in this population.

For patients undergoing HSCT with low levels of PPWB, positive psychology (PP) interventions that enhance PPWB are needed to mitigate the burden of adverse clinical outcomes attributed to low levels of PPWB observed in medical populations beyond the unfavorable effects of distress.4,5,6 PP interventions employ simple and pleasurable activities such as writing a gratitude letter to promote PPWB.8,51 Although PP interventions are feasible and have successfully fostered PPWB in several medical populations with sustained effects on clinical outcomes (e.g., QOL),52–54 tailored PP interventions for the HSCT population are lacking and understudied. Our prior work on a tailored PP intervention for HSCT survivors which constitutes a nine-week phone-delivered PP intervention (PATH) on gratitude, strengths, and meaning, showed initial acceptability in an open pilot trial.51 Although the feasibility and preliminary efficacy of the PATH intervention is currently being tested using a randomized controlled trial (NCT05147311), future efficacy trials for PP interventions tailored to the unique and unmet psychosocial needs of patients undergoing HSCT are warranted.

This study has several important limitations. First, the cross-sectional data of patients at 100 days post-transplant may potentially limit the generalizability of our findings to patients during the transplant hospitalization or later in recovery. A longitudinal assessment of these constructs, especially those that can change over time, like flourishing, may enhance our understanding of how these constructs evolve over the course of HSCT. Second, this project was not designed to assess the psychometric properties of individual measures, such as the ceiling effect, and potentially how measures correlate. Hence, future studies should also evaluate the correlation between PPWB measures to inform recommendations for the best and most efficient ways to adequately assess PPWB in this population without a survey burden. As we gain more knowledge on the best validated measures to assess PPWB in this population, the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplantation Research (CIBMTR) which collects longitudinal and cross-sectional patient-reported outcome (PRO) data from cellular therapy recipients including HSCT survivors, should include PPWB assessments in their routine PRO assessments. Third, our findings may not generalize to individuals from ethnic minorities and underserved groups since the majority of our cohort were non-Hispanic White and were college educated. Fourth, given PPWB is not a routinely included with psychological health measures in chronic medical populations, our comparator samples such as data from the MIDUS study is dated and does not reflect potential changes impacted by the COVID-19 pandemic or advancements in chronic disease management over the past two decades. Lastly, we were unable to control for sociodemographic variables, such as age, sex, race, and other factors known to affect PPWB outcomes in the comparator samples, which limited our ability to make head-to-head comparisons.55,56 Since we did not have access to data from these studies for our analysis, we could not account for any biases or differences in reported mean scores. Large prospective studies which rigorously compare positive constructs in the HSCT population and other serious illness populations may further enhance our ability to understand their impact on clinical outcomes.

In conclusion, although patients with hematologic malignancies undergoing HSCT report high levels of PPWB captured by well-validated measures for PPWB in medical populations, a substantial minority report lower levels of PPWB. Future studies should explore how PPWB evolves over the entire trajectory of HSCT and recovery to inform tailored interventions to help patients cultivate PPWB, given its beneficial association with clinical outcomes observed in other medical populations.

Supplementary Material

Highlights.

Positive psychological well-being (PPWB) includes gratitude and flourishing

PPWB is associated with important health outcomes in the HSCT population

A substantial minority of HSCT survivors report low PPWB.

Findings demonstrate the need to increase support for HSCT recipients with low PPWB

Funding:

This work was supported by the National Cancer Institute through grant K08CA251654 (to Dr. Amonoo) and by the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute through grants R01HL113272 (to Dr. Huffman), and R01HL155301 (to Dr. Celano). Dr. El-Jawahri is a scholar of the Leukemia and Lymphoma Society.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

Conflict of Interest Statement: All other authors report no conflict of interest.

References

- 1.El-Jawahri AR, Vandusen HB, Traeger LN, Fishbein JN, Keenan T, Gallagher ER, et al. Quality of life and mood predict posttraumatic stress disorder after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Cancer. Mar 1 2016;122(5):806–12. doi: 10.1002/cncr.29818 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Amonoo HL, Barclay ME, El-Jawahri A, Traeger LN, Lee SJ, Huffman JC. Positive Psychological Constructs and Health Outcomes in Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation Patients: A Systematic Review. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. Jan 2019;25(1):e5–e16. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2018.09.030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Kubzansky LD, Huffman JC, Boehm JK, Hernandez R, Kim ES, Koga HK, et al. Positive Psychological Well-Being and Cardiovascular Disease: JACC Health Promotion Series. J Am Coll Cardiol. Sep 18 2018;72(12):1382–1396. doi: 10.1016/j.jacc.2018.07.042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Chida Y, Steptoe A. Positive psychological well-being and mortality: a quantitative review of prospective observational studies. Psychosomatic Medicine. Sep 2008;70(7):741–756. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jim HS, Syrjala KL, Rizzo D. Supportive care of hematopoietic cell transplant patients. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. Jan 2012;18(1 Suppl):S12–6. doi: 10.1016/j.bbmt.2011.10.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Ehrlich KB, Miller GE, Scheide T, Baveja S, Weiland R, Galvin J, et al. Pre-transplant emotional support is associated with longer survival after allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Bone Marrow Transplant. Jul 18 2016; doi: 10.1038/bmt.2016.191 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Huffman JC, Millstein RA, Mastromauro CA, Moore SV, Celano CM, Bedoya CA, et al. A Positive Psychology Intervention for Patients with an Acute Coronary Syndrome: Treatment Development and Proof-of-Concept Trial. J Happiness Stud. Oct 2016;17(5):1985–2006. doi: 10.1007/s10902-015-9681-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Amonoo HL, El-Jawahri A, Deary EC, Traeger LN, Cutler CS, Antin JA, et al. Yin and Yang of Psychological Health in the Cancer Experience: Does Positive Psychology Have a Role? J Clin Oncol. Aug 1 2022;40(22):2402–2407. doi: 10.1200/jco.21.02507 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Boehm JK, Trudel-Fitzgerald C, Kivimaki M, Kubzansky LD. The prospective association between positive psychological well-being and diabetes. Health Psychol. Oct 2015;34(10):1013–21. doi: 10.1037/hea0000200 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Madva EN, Sadlonova M, Harnedy LE, Longley RM, Amonoo HL, Feig EH, et al. Positive psychological well-being and clinical characteristics in IBS: A systematic review. Gen Hosp Psychiatry. Jan 11 2023;81:1–14. doi: 10.1016/j.genhosppsych.2023.01.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kenzik K, Huang IC, Rizzo JD, Shenkman E, Wingard J. Relationships among symptoms, psychosocial factors, and health-related quality of life in hematopoietic stem cell transplant survivors. Support Care Cancer. Mar 2015;23(3):797–807. doi: 10.1007/s00520-014-2420-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Knight JM, Moynihan JA, Lyness JM, Xia Y, Tu X, Messing S, et al. Peri-transplant psychosocial factors and neutrophil recovery following hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. PLoS One. 2014;9(6):e99778. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0099778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Larsson B, Dragioti E, Gerdle B, Bjork J. Positive psychological well-being predicts lower severe pain in the general population: a 2-year follow-up study of the SwePain cohort. Ann Gen Psychiatry. 2019;18:8. doi: 10.1186/s12991-019-0231-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Madva EN, Harnedy LE, Longley RM, Rojas Amaris A, Castillo C, Bomm MD, et al. Positive psychological well-being: A novel concept for improving symptoms, quality of life, and health behaviors in irritable bowel syndrome. Neurogastroenterol Motil. Jan 17 2023:e14531. doi: 10.1111/nmo.14531 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Steptoe A, Demakakos P, de Oliveira C, Wardle J. Distinctive biological correlates of positive psychological well-being in older men and women. Psychosom Med. Jun 2012;74(5):501–8. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0b013e31824f82c8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Amonoo HL, Brown LA, Scheu CF, Millstein RA, Pirl WF, Vitagliano HL, et al. Positive psychological experiences in allogeneic hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Psychooncology. Aug 2019;28(8):1633–1639. doi: 10.1002/pon.5128 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Peterman AH, Fitchett G, Brady MJ, Hernandez L, Cella D. Measuring spiritual well-being in people with cancer: the functional assessment of chronic illness therapy--Spiritual Well-being Scale (FACIT-Sp). Ann Behav Med. Winter 2002;24(1):49–58. doi: 10.1207/s15324796abm2401_06 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peterman AH, Reeve CL, Winford EC, Cotton S, Salsman JM, McQuellon R, et al. Measuring meaning and peace with the FACIT-spiritual well-being scale: distinction without a difference? Psychol Assess. Mar 2014;26(1):127–37. doi: 10.1037/a0034805 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Webster K, Cella D, Yost K. The Functional Assessment of Chronic Illness Therapy (FACIT) Measurement System: properties, applications, and interpretation. Health Qual Life Outcomes. Dec 16 2003;1:79. doi: 10.1186/1477-7525-1-79 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scheier MF, Carver CS, Bridges MW. Distinguishing optimism from neuroticism (and trait anxiety, self-mastery, and self-esteem): a reevaluation of the Life Orientation Test. J Pers Soc Psychol. Dec 1994;67(6):1063–78. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.67.6.1063 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.McCullough ME, Emmons RA, Tsang JA. The grateful disposition: a conceptual and empirical topography. J Pers Soc Psychol. Jan 2002;82(1):112–27. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.82.1.112 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Watson D, Clark LA, Tellegen A. Development and validation of brief measures of positive and negative affect: The PANAS scales. J Pers Soc Psychol. 1988;54(6):1063–1070. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Diener E, Emmons RA, Larsen RJ, Griffin S. The Satisfaction With Life Scale. J Pers Assess. Feb 1985;49(1):71–5. doi: 10.1207/s15327752jpa4901_13 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Diener E, Wirtz D, Tov W, Kim-Prieto C, Choi D, Oishi S, & Biswas-Diener R New Well-being Measures: Short Scales to Assess Flourishing and Positive and Negative Feelings. Social Indicators Research. 2010;97(2):143–156. doi: 10.1007/s11205-009-9493-y [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Ryff CD, Almeida DM, Ayanian JZ, Carr DS, Cleary PD, Coe C, et al. Data from: Midlife in the United States (MIDUS 2), 2004–2006. 2021. doi: 10.3886/ICPSR04652.v8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hone L, Jarden A, Schofield G. Psychometric properties of the Flourishing Scale in a New Zealand sample. Social Indicators Research. 2014;119:1031–1045. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0501-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 27.McDonnell LA, Riley DL, Blanchard CM, Reid RD, Pipe AL, Morrin LI, et al. Gender differences in satisfaction with life in patients with coronary heart disease: physical activity as a possible mediating factor. J Behav Med. Jun 2011;34(3):192–200. doi: 10.1007/s10865-010-9300-x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Lucas-Carrasco R, Sastre-Garriga J, Galan I, Den Oudsten BL, Power MJ. Preliminary validation study of the Spanish version of the satisfaction with life scale in persons with multiple sclerosis. Disabil Rehabil. 2014;36(12):1001–5. doi: 10.3109/09638288.2013.825650 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Lamont RA, Nelis SM, Quinn C, Martyr A, Rippon I, Kopelman MD, et al. Psychological predictors of ‘living well’ with dementia: findings from the IDEAL study. Aging Ment Health. Jun 2020;24(6):956–964. doi: 10.1080/13607863.2019.1566811 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Oei TP, McAlinden NM. Changes in quality of life following group CBT for anxiety and depression in a psychiatric outpatient clinic. Psychiatry Res. Dec 30 2014;220(3):1012–8. doi: 10.1016/j.psychres.2014.08.036 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Legler SR, Beale EE, Celano CM, Beach SR, Healy BC, Huffman JC. State Gratitude for One’s Life and Health after an Acute Coronary Syndrome: Prospective Associations with Physical Activity, Medical Adherence and Re-hospitalizations. J Posit Psychol. 2019;14(3):283–291. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2017.1414295 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Huffman JC, DuBois CM, Millstein RA, Celano CM, Wexler D. Positive Psychological Interventions for Patients with Type 2 Diabetes: Rationale, Theoretical Model, and Intervention Development. J Diabetes Res. 2015;2015:428349. doi: 10.1155/2015/428349 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Crouch TA, Verdi EK, Erickson TM. Gratitude is positively associated with quality of life in multiple sclerosis. Rehabil Psychol. Aug 2020;65(3):231–238. doi: 10.1037/rep0000319 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.McGee JS, Zhao HC, Myers DR, Kim SM. Positive Psychological Assessment and Early-Stage Dementia. Clin Gerontol. Jul–Sep 2017;40(4):307–319. doi: 10.1080/07317115.2017.1305032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Celano CM, Beale EE, Mastromauro CA, Stewart JG, Millstein RA, Auerbach RP, et al. Psychological interventions to reduce suicidality in high-risk patients with major depression: a randomized controlled trial. Psychol Med. Apr 2017;47(5):810–821. doi: 10.1017/S0033291716002798 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Huffman JC, Golden J, Massey CN, Feig EH, Chung WJ, Millstein RA, et al. A Positive Psychology-Motivational Interviewing Intervention to Promote Positive Affect and Physical Activity in Type 2 Diabetes: The BEHOLD-8 Controlled Clinical Trial. Psychosom Med. Sep 2020;82(7):641–649. doi: 10.1097/PSY.0000000000000840 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Freedman ME, Healy BC, Huffman JC, Chitnis T, Weiner HL, Glanz BI. An At-home Positive Psychology Intervention for Individuals with Multiple Sclerosis: A Phase 1 Randomized Controlled Trial. Int J MS Care. May-Jun 2021;23(3):128–134. doi: 10.7224/1537-2073.2020-020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Strober LB. Personality in multiple sclerosis (MS): impact on health, psychological well-being, coping, and overall quality of life. Psychol Health Med. Feb 2017;22(2):152–161. doi: 10.1080/13548506.2016.1164321 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Mountain GA, Cooper CL, Wright J, Walters SJ, Lee E, Craig C, et al. The Journeying through Dementia psychosocial intervention versus usual care study: a single-blind, parallel group, phase 3 trial. Lancet Healthy Longev. Apr 2022;3(4):e276–e285. doi: 10.1016/S2666-7568(22)00059-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.de Manincor M, Bensoussan A, Smith CA, Barr K, Schweickle M, Donoghoe LL, et al. Individualized Yoga for Reducing Depression and Anxiety, and Improving Well-Being: A Randomized Controlled Trial. Depress Anxiety. Sep 2016;33(9):816–28. doi: 10.1002/da.22502 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Hone L, Jarden A & Schofield G Psychometric Properties of the Flourishing Scale in a New Zealand Sample. Social Indicators Research. 2014;119:1031–1045. doi: 10.1007/s11205-013-0501-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Huffman JC, Feig EH, Millstein RA, Freedman M, Healy BC, Chung WJ, et al. Usefulness of a Positive Psychology-Motivational Interviewing Intervention to Promote Positive Affect and Physical Activity After an Acute Coronary Syndrome. Am J Cardiol. Jun 15 2019;123(12):1906–1914. doi: 10.1016/j.amjcard.2019.03.023 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Markus Wettstein US, Wahl Hans-Werner, Shoval Noam, and Heinik Jeremia. Behavioral Competence and Emotional Well-Being of Older Adults with Mild Cognitive Impairment: Comparison with Cognitively Healthy Controls and Individuals with Early-Stage Dementia. Journal of Gerontopsychology and Geriatric Psychiatry. 2014;27(2):55–65. doi: 10.1024/1662-9647/a000107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lee SJ, Loberiza FR, Rizzo JD, Soiffer RJ, Antin JH, Weeks JC. Optimistic expectations and survival after hematopoietic stem cell transplantation. Biol Blood Marrow Transplant. Jun 2003;9(6):389–96. doi: 10.1016/s1083-8791(03)00103-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.French B, Sycamore NJ, McGlashan HL, Blanchard CCV, Holmes NP. Ceiling effects in the Movement Assessment Battery for Children-2 (MABC-2) suggest that non-parametric scoring methods are required. PLoS One. 2018;13(6):e0198426. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0198426 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holmes NP. The principle of inverse effectiveness in multisensory integration: some statistical considerations. Brain Topogr. May 2009;21(3–4):168–76. doi: 10.1007/s10548-009-0097-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.VanderWeele TJ, McNeely E, Koh HK. Reimagining Health-Flourishing. JAMA. May 7 2019;321(17):1667–1668. doi: 10.1001/jama.2019.3035 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Zhou M, Lin W. Adaptability and Life Satisfaction: The Moderating Role of Social Support. Front Psychol. 2016;7:1134. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2016.01134 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Strine TW, Chapman DP, Balluz LS, Moriarty DG, Mokdad AH. The associations between life satisfaction and health-related quality of life, chronic illness, and health behaviors among U.S. community-dwelling adults. J Community Health. Feb 2008;33(1):40–50. doi: 10.1007/s10900-007-9066-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Hooker SA, Masters KS, Vagnini KM, Rush CL. Engaging in personally meaningful activities is associated with meaning salience and psychological well-being. The Journal of Positive Psychology. 2020/11/01 2020;15(6):821–831. doi: 10.1080/17439760.2019.1651895 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Amonoo HL, El-Jawahri A, Celano CM, Brown LA, Harnedy LE, Longley RM, et al. A positive psychology intervention to promote health outcomes in hematopoietic stem cell transplantation: the PATH proof-of-concept trial. Bone Marrow Transplant. Sep 2021;56(9):2276–2279. doi: 10.1038/s41409-021-01296-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Rosenberg AR, Bradford MC, Junkins CC, Taylor M, Zhou C, Sherr N, et al. Effect of the Promoting Resilience in Stress Management Intervention for Parents of Children With Cancer (PRISM-P): A Randomized Clinical Trial. JAMA Netw Open. Sep 4 2019;2(9):e1911578. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2019.11578 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Rosenberg AR, Bradford MC, Barton KS, Etsekson N, McCauley E, Curtis JR, et al. Hope and benefit finding: Results from the PRISM randomized controlled trial. Pediatr Blood Cancer. Jan 2019;66(1):e27485. doi: 10.1002/pbc.27485 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Rosenberg AR, Bradford MC, McCauley E, Curtis JR, Wolfe J, Baker KS, et al. Promoting resilience in adolescents and young adults with cancer: Results from the PRISM randomized controlled trial. Cancer. Oct 1 2018;124(19):3909–3917. doi: 10.1002/cncr.31666 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Dricu M, Moser DA, Aue T. Optimism bias and its relation to scenario valence, gender, sociality, and insecure attachment. Scientific Reports. 2022/11/02 2022;12(1):18534. doi: 10.1038/s41598-022-22031-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Mroczek DK, Kolarz CM. The effect of age on positive and negative affect: a developmental perspective on happiness. J Pers Soc Psychol. Nov 1998;75(5):1333–49. doi: 10.1037//0022-3514.75.5.1333 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.