Abstract

Random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) was used for the identification of Legionella species. Primer SK2 (5′-CGGCGGCGGCGG-3′) and standardized RAPD conditions gave the technique a reproducibility of 93 to 100%, depending on the species tested. Species-specific patterns corresponding to the 42 Legionella species were consequently defined by this method; the patterns were dependent on the recognition of a core of common bands for each species. This specificity was demonstrated by testing 65 type strains and 265 environmental and clinical isolates. No serogroup-specific profiles were obtained. A number of unidentified Legionella isolates potentially corresponding to new species were clustered in four groups. RAPD analysis appears to be a rapid and reproducible technique for identification of Legionella isolates to the species level without further restriction or hybridization.

The Philadelphia outbreak of pneumonia in 1976 led to recognition of a new genus, Legionella (6), responsible for both legionellosis and Pontiac fever. In 1996, the family Legionellaceae contained 42 described species (2) and three subspecies (5). Usually, the bases for the identification of Legionella species are cultural characteristics, biochemical reactions, and serotyping by slide agglutination test or direct immunofluorescence assay (7, 15, 16, 26). Additionally, analysis of whole-cell fatty acids, ubiquinone contents, and whole-cell protein profiles can be useful to achieve identification of Legionella isolates at the species level (3, 17, 29). However, in several instances, as for the bluish white autofluorescent species and all of the cross-reacting serogroups, these methods do not discriminate to a sufficient extent for definitive species identification. In these cases, genotypic methods such as DNA-DNA hybridization (4) and ribotyping (13) are the only means for identification at the species level.

One of the new genotypic methods, known as random amplified polymorphic DNA (RAPD) analysis (30, 31), has been used mostly for intraspecies discrimination in epidemiological studies (12, 22, 27). However, for some other taxa, such as Enterococcus, Candida, and Leptospira species, this method has been successfully applied for species identification (9, 18, 23). At first, RAPD analysis was used to differentiate the bluish white autofluorescent Legionella species, allowing identification for the first time of a clinical isolate of L. parisiensis (19). Use of RAPD analysis for identification of Legionella species has recently been reported by Bansal and McDonell, but that investigation was limited by the use of type strains of Legionella species and included nonreference isolates only for Legionella pneumophila (1). In the present study, we have evaluated and validated RAPD analysis for the identification of Legionella species by using a large number of strains representing 42 species. Importantly, this method has been optimized for our laboratory conditions, as exemplified by its nearly complete reproducibility.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Bacterial strains.

The strains used in this study included 65 type strains of 42 species (plus three L. pneumophila subspecies) and 64 serogroups, 28 well-defined strains described in the literature, and 186 environmental and clinical isolates from patients with pneumonias that were collected by the French National Reference Center for Legionella (Table 1). Fifty-one strains belonging to four potentially new species were also tested (Table 1). All of the strains were tested after being conserved in liquid nitrogen. Some isolates were also tested as fresh isolates or after lyophilization.

TABLE 1.

Legionella strains used in this study

| Species (serogroup) | No. of strains | Strain designation(s)a |

|---|---|---|

| L. adelaidensis | 1 | ATCC 49625T |

| L. anisa | 24 | ATCC 35292T, CH47-C1L, CH47-C3L, Card76A1, Cobac, FMI-3, G11-1, Go1-1, Go1-2, HD10K2, HEH15D3, PaDebIH3, S14-14, S14-17, SIX-1, SIX-2, S17-5, S18-1, S97XXIII1, StSiI-7, Tour97I-1, Tour97I-2, Tour97I-3, Tour97I-4 |

| L. birminghamensis | 4 | ATCC 43702T, A12C15, CFVII3A, Greo8P2 |

| L. bozemanii (1) | 8 | ATCC 33217T, Arizona-1L, GAPHL, Bruxelles DL, DignB111, DignC61, Ly86.88, PortII-18 |

| L. bozemanii (2) | 4 | ATCC 35545S, Paris-96010250, Paris-96010251, UL-7T/2 |

| L. brunensis | 4 | ATCC 43878T, FS-60, Ji-642, OV-182 |

| L. cherrii | 1 | ATCC 35252T |

| L. cincinnatiensis | 2 | ATCC 43753T, IB97III3 |

| “L. donaldsonii” | 1 | LC 878 |

| L. dumoffii | 9 | ATCC 33279T, ATCC 35850L, A80B3, A97I-1, A97I-2, L2F10, S-92101226, T23-3, T23-6 |

| L. erythra (1) | 5 | ATCC 35303T, A96VII2-1, AngIVLev, CEP3F29, T26-20 |

| L. erythra (2) | 5 | LC217S, A96VII2-6, M12-6, S96XXII-5, UL-13 |

| L. fairfieldensis | 1 | ATCC 49588T |

| L. feeleii (1) | 4 | ATCC 35072T, Ly126.92a, Ly126.92b (ATCC 700513), Ly166.96 (ATCC 700514) |

| L. feeleii (2) | 1 | ATCC 35849S |

| L. geestiana | 2 | ATCC 49504T, ParDid16-1 |

| Legionella genomospecies 1 | 1 | ATCC 51913T |

| L. gormanii | 4 | ATCC 33297T, Greo9C3, Greo9C5, Toul29-16 |

| L. gratiana | 1 | ATCC 49413T |

| L. hackeliae (1) | 1 | ATCC 35250T |

| L. hackeliae (2) | 1 | ATCC 35299S |

| L. israelensis | 1 | ATCC 43119T |

| L. jamestowniensis | 1 | ATCC 35298T |

| L. jordanis | 3 | ATCC 33623T, BesacII-1, Ly95.96 |

| L. lansingensis | 1 | ATCC 49751T |

| L. londiniensis | 16 | ATCC 49505T, A52F94, CF17-1, CF97I-1, Co9C3, Dij13-1, Frankfurt 3, Grèce 5-1, IB35-1, IP8-1, IP13-1, IZ-200L, Mulhouse B26 (ATCC 700510), Mulh12A1, NancV-4, Port5 |

| L. longbeachae (1) | 3 | ATCC 33462T, BruxIII-3, 88010337 |

| L. longbeachae (2) | 1 | ATCC 33484S |

| L. maceachernii | 2 | ATCC 35300T, Toul20-5 |

| L. micdadei | 12 | ATCC 33218T, A73G9, CF97I-2, LugII-124, Lyon-91103670, Nantes-93101936, PortIII-10, PPAL, T16-5, T29-9, Toulon VI-5, Virginia-1L |

| L. moravica | 1 | ATCC 43877T |

| L. nautarum | 1 | ATCC 49506T |

| L. oakridgensis | 15 | ATCC 33761T, A31H1, Dign2C34, Dij6-2, Greo8E18, Greo8P12, Lille A1, N3, NIV-1, NIV-2, NV-2, NV-6, Nantes-930101937 (ATCC 700516), Nantes-93101868 (ATCC 700515), PortII-16 |

| L. parisiensis | 3 | ATCC 35299T, FLP1L, FLP2 (ATCC 700174)L |

| L. pneumophila | 96 | ATCC 33152T, ATCC 33154S, ATCC 33155S, ATCC 33156T, ATCC 33216S, ATCC 33215S, ATCC 33823S, ATCC 35096S, ATCC 35289S, ATCC 43283S, ATCC 43130S, ATCC 43290S, ATCC 43736S, ATCC 43703S, ATCC 35251S, ATCC 33735L, ATCC 33737T, Bellingham-1L, Benidorm 030EL, Cambridge-2L, Detroit-1L, CFIII1C, Golf7-9, HEH96IVe1c3, HEH96IVe2c3, IP23-1, IP23-2, Knoxville-1L, L3, L12, L13, L23, L27, L31, L32, L33, L34, L35, L36, L37, L38, L39, L40, L41, L42, L43, L44, L45, L46, L47, L48, L51, L52, L54, L59, L60, L61, L62, L64, L65, L66, L67, L68, L71, L211, L212, L214, L215, LisbIIIA10, Lisb95-1, Lisb95-2, Lisb95-3, Lisb95-4, Lisb95-5, Lisb95-6, Lisb95-7, Lisb95-8, Lyon-96010018, Ly154.95, Mars96II1, Mars96II2, Mars96III2, MI97122245, Nancy-96010154, NevIN1, NevIN2, NevIIIA1, NevIIIA2, Nevers-950102440, Nice-96010131, OLDAL, Oxford-1L, PontiacL, Portland-1L, S96XIII16, S96XIV4 |

| L. quateirensis | 1 | ATCC 49507T |

| L. quinlivanii (1) | 8 | ATCC 43830T, 1448-AUS-EL, 1449-AUS-EL, 1451-AUS-EL, 1452-AUS-EL, 2359-AUS-EL, Lech2A10, Lech2A47 |

| L. quinlivanii (2) | 1 | NCTC 12434S |

| L. rubrilucens | 8 | ATCC 35304T, A56, Ang6-1, Dij45-1, Dij48-2, Gen2, Lech2E58, VilleA1 |

| L. sainthelensi (1) | 1 | ATCC 35248T |

| L. sainthelensi (2) | 5 | ATCC 49322S, Bord-97010302, ED-4aL, IZ-86L, Ly176.97 (ATCC 700517) |

| L. santicrucis | 2 | ATCC 35301T, A9C27 |

| L. shakespearei | 1 | ATCC 49655T |

| L. spiritensis (1) | 2 | ATCC 35249T, IB96VI-1 |

| L. spiritensis (2) | 2 | NCTC 12082S, Lnetti |

| L. steigerwaltii | 1 | ATCC 35302T |

| L. tucsonensis | 1 | ATCC 49180T |

| L. wadsworthii | 2 | ATCC 33877T, Dign2C67 |

| L. waltersii | 1 | ATCC 51914T |

| L. worsleiensis | 3 | ATCC 49508T, SBPIB1, SBPIB2 |

| Legionella sp. 1 | 3 | Greo11D13 (ATCC 700509), Mulh12A22, Mulh12A23 1 |

| Legionella sp. 2 | 3 | IBV-2, IBV-3 (ATCC 700511), VeniIA |

| Legionella sp. 3 | 5 | MontA1 (ATCC 700512), MontA2, MontA3, MontA4, MontA5 |

| Legionella sp. 4 | 40 | Turin I no. 1 (ATCC 700508), Turin I-2, Turin II-180, Turin II-195, BM-750, C/SE1C25, C/SE1C26, CrRo2C9, CrRo2C13, GapIB41, GapIB42, Gen10-1, HD2B3, HD2B4, HD2B12, HGIe1C7, HGeI3C7, HGeI3C10, IB39-6, Laus15-6, Laus96V-1, LisbIIIA5, MI-4, MIV-1, MoulIC1, MoulID5, MoulID6, Merc96I8-7, Merc96I8-8, PortA12, PortA13, PortA14, PortA16, PortA17, PortA19, PortA20, T26-14, T26-17, T28-7, T28-8 |

Superscripts: L, strain described in the literature; S, serogroup type strain; T, species type strain.

Bacteriologic methods.

Bacteria were grown on buffered charcoal yeast extract (BCYE) agar supplemented with 0.1% α-ketoglutarate in 2.5% CO2 (11) and, when required, on glycine-vancomycin-polymyxin B-colistin BCYE agar plates. Controls were prepared with unsupplemented BCYE agar and blood agar plates (3). Environmental and clinical isolates were identified by combinations of biochemical reactions (16), direct immunofluorescence assay with unadsorbed and adsorbed sera (15), ubiquinone content and whole-cell fatty acid composition analysis (3), and whole-cell protein profiling (3). Bacteria were lysed by the boiling water method as previously described (19), and DNA extracts were quantified spectrophotometrically.

Choice of primer.

Three primers were tested for the ability to differentiate Legionella species: SK2 (5′-CGGCGGCGGCGG-3′) (21), 910-05 (5′-CCGGCGGCG-3′) (20), and BG2 (5′-TACATTCGAGGACCCCTAAGTG-3′) (27).

Optimization of PCR conditions.

Optimal conditions for each primer were achieved by using the Taguchi method as modified by Cobb and Clarkson (8). The development of the required conditions was at first attained with L. anisa ATCC 35292, L. bozemanii serogroup 1 strain ATCC 33217, L. micdadei ATCC 33218, L. pneumophila serogroup 1 strain ATCC 33152, and L. pneumophila serogroup 3 strain ATCC 33155.

Optimized RAPD technique.

RAPD was performed with primer SK2 as follows. A 5-μg sample of DNA, 3 mM MgCl2, 0.4 mM each primer, 2.5 U of Taq DNA polymerase (Amplitaq; Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Branchburg, N.J.), and 0.1 mM each deoxynucleoside triphosphate (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) were mixed for each sample reaction in 1× PCR buffer (10 mM Tris-HCl [pH 8.3], 50 mM KCl, 0.001% gelatin; Perkin-Elmer Cetus). PCR cycles were as follows: 4 min of denaturation at 94°C followed by 42 cycles of 1 min at 94°C, 1 min at 30°C, and 2 min at 72°C and a final extension step of 72°C for 3 min. PCR products were then separated on standard 1.5% agarose gel (SeaKem GTG; FMC BioProducts, Rockland, Maine), stained with ethidium bromide, and photographed under UV light with an MP-4 Camera (Polaroid, Cambridge, Mass.). The profiles were analyzed by the Taxotron package (Institut Pasteur, Paris, France) using the Dice coefficient (10); clustering was based on the single-linkage method. A linear error of 2% at 100 bp to 3% at 3,500 bp was tolerated.

Reproducibility of the RAPD assay.

The reproducibility of the method was assessed by 20 independent PCR assays with primer SK2 for each reference strain with different DNA extracts. A control strain, L. pneumophila serogroup 1 strain Philadelphia-1, was included in each RAPD assay.

RESULTS

Optimization.

The conditions were optimized for DNA, MgCl, and primer concentrations, template annealing temperature, and number of PCR cycles by using the modified Taguchi method. Conditions allowing the best readable patterns were therefore chosen for further experiments. The RAPD fingerprints obtained with primer SK2 gave 2 (i.e., for L. steigerwaltii) to 11 (i.e., for L. micdadei) DNA bands with various intensities ranging in size from 200 bp to approximately 3 kbp. Within a species, primer SK2 was found to generate more fragments common to nonepidemiologically related isolates, whereas primer BG2 generated very diverse patterns (data not shown).

Reproducibility.

For all of the reference strains tested under these optimized RAPD assay conditions, over 20 independent determinations, the reproducibility of the patterns ranged from 93 to 100%, depending on the species tested. For instance, 51 of the 55 profiles obtained for strain Philadelphia-1 (L. pneumophila serogroup 1) were strictly identical, whereas 4 profiles differed by only 1 or 2 minor bands over a total of 14 bands.

Differentiation of Legionella type strains.

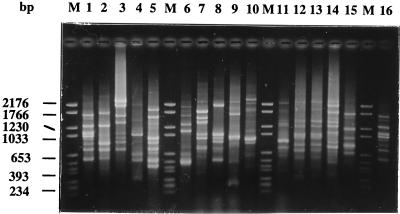

A type strain-specific pattern was obtained for the 42 species. Species with more than one serogroup, except L. pneumophila, L. bozemanii, L. longbeachae, and L. sainthelensi, did not present additional profiles corresponding to each serogroup and showed only a species-specific profile. For L. pneumophila, minor variations were detected among the 15 serogroups tested, but a core of three common bands (750, 1,080, and 1,675 bp) deduced from a total number of bands varying from 5 to 14 and corresponding to a species-specific pattern was observed in all strains (Fig. 1, lanes 1 and 2). L. bozemanii serogroups 1 and 2 had five DNA fragments in common and were differentiated by four (putatively) serogroup 1-specific bands and two (putatively) serogroup 2-specific bands. The two serogroup type strains of L. longbeachae had seven fragments in common (Fig. 1, lanes 10 and 11), the same as for L. sainthelensi. Each serogroup type strain of these two species also contained (putatively) strain-specific fragments.

FIG. 1.

RAPD amplification patterns of Legionella type strains. Lanes: M, molecular weight marker VI (Boehringer Mannheim); 1 and 16, L. pneumophila serogroup 1 strain ATCC 33152; 2, L. pneumophila serogroup 3 strain ATCC 33155; 3, L. micdadei ATCC 33218; 4, L. maceachernii ATCC 35300; 5, L. anisa ATCC 35292; 6, L. bozemanii serogroup 1 strain ATCC 33217; 7, L. parisiensis ATCC 35299; 8, L. gratiana ATCC 49413; 9, L. tucsonensis ATCC 49180; 10, L. longbeachae serogroup 1 strain ATCC 33462; 11, L. longbeachae serogroup 2 strain ATCC 33484; 12, L. erythra serogroup 1 strain ATCC 35303; 13, L. erythra serogroup 2 strain LC217; 14, L. rubrilucens ATCC 35304; 15, L. spiritensis serogroup 1 strain ATCC 49655.

Identification of L. pneumophila isolates.

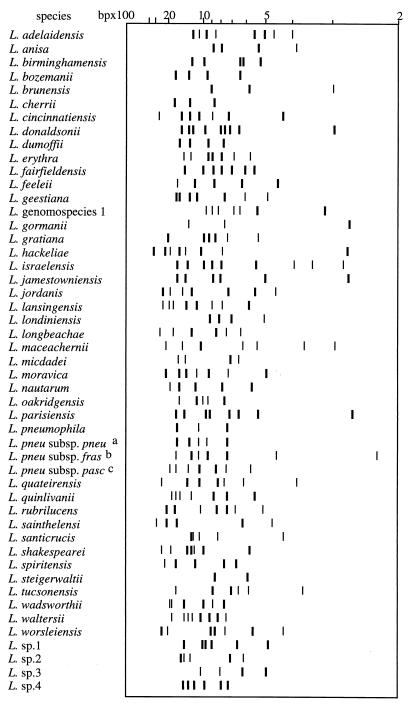

For the 96 L. pneumophila strains tested (16 serogroup type strains, 10 strains described in the literature, and 70 environmental and clinical isolates), 50 profiles were produced. The species-specific pattern made by three bands (described above) was always present, whatever the serogroups or the subspecies tested (Fig. 2). These three bands were simultaneously present only in the case of L. pneumophila strains. The following additional DNA fragments were frequently found: 1,296 bp (95% of the strains), 966 bp (82%), and 575 bp (79%). Neither serogroup nor monoclonal subtype patterns were observed. However, the four available strains of L. pneumophila subsp. fraseri exhibited three other bands simultaneously in their patterns (1,247, 455, and 227 bp). The latter three bands were never found in the other subspecies of L. pneumophila. At the time of the study, the two available strains of L. pneumophila subsp. pascullei showed the same profile, while their subspecies-specific bands (1,950 and 860 bp) were never present in the other two subspecies. According to these results, strains belonging to L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila could be differentiated from the subspecies pascullei by the presence of a 966-bp DNA fragment and the absence of the two bands specific to L. pneumophila subsp. pascullei (Fig. 2).

FIG. 2.

Schematic core of species- and subspecies-specific patterns of Legionella species. Schematic of RAPD patterns constructed with Taxotron software. The bands represented are those always present in a given species; bands are represented according to their intensities. a, L. pneumophila subsp. pneumophila; b, L. pneumophila subsp. fraseri; c, L. pneumophila subsp. pascullei.

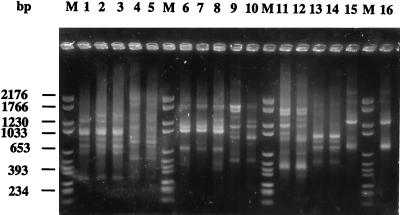

Identification of Legionella species.

Of the 234 non-L. pneumophila strains studied (49 serogroup and species type strains, 18 strains described in the literature, 116 environmental and clinical isolates of known species, and 51 isolates unidentified at the species level), 135 profiles were obtained. Species-specific fragments were found when multiple isolates of a species were analyzed (Fig. 3), supporting the existence of type strain-pecific patterns, as noted above. For these, the number of common fragments varied among the species from three (L. gormanii) to eight (L. parisiensis). Again, no serogroup-specific patterns were found (Fig. 3, lanes 1 to 3). For L. bozemanii, a species-specific pattern was confirmed but not the serogroup-specific patterns proposed for the type strains. For the species L. longbeachae and L. sainthelensi, no serogroup-specific patterns were found either.

FIG. 3.

Visual identification of Legionella isolates by RAPD patterns. Lanes: M, molecular weight marker VI (Boehringer Mannheim); 1, L. erythra serogroup 1 strain ATCC 35302; 2, L. erythra serogroup 2 strain LC217; 3, L. erythra serogroup 2 strain Aix96VII2-1; 4, L. rubrilucens aix56; 5, L. rubrilucens ATCC 35304; 6, L. bozemanii serogroup 1 strain GAPH; 7, L. bozemanii serogroup 1 strain Bruxelles D; 8, L. bozemanii serogroup 1 strain DignB111; 9, L. bozemanii serogroup 2 strain Paris-96010250; 10, L. bozemanii serogroup 2 strain ATCC 35545; 11, L. feeleii serogroup 1 strain ATCC 35072; 12, L. feeleii serogroup 1 strain Ly126.92a; 13, L. londiniensis ATCC 49505; 14, L. londiniensis IP8-1; 15, L. jordanis ATCC 33623; 16, L. jordanis Ly95.96.

After numerical comparisons with the Taxotron package, the 330 strains (L. pneumophila included) were grouped into species-specific clusters. The 51 unidentified isolates were clustered into four groups corresponding to four potentially new genomic species (data not shown).

DISCUSSION

In the present study, we have evaluated the RAPD assay technique for the identification of Legionella species. Since preliminary experiments revealed that the method suffered from low reproducibility, our efforts were applied to optimization of this technique. Therefore, we examined conditions that would allow maximum reproducibility and reliable typeability for Legionella. The modified Taguchi method (8) enabled us to attain PCR conditions that generated reproducible profiles for all of the species tested. Primer SK2 proved to be an efficient tool for taxonomic purposes, whereas primer BG2 confirmed its usefulness for the previously demonstrated intraspecies differentiation of Legionella (27). It should be noted that the RAPD assay method using various other primers has also been applied for this purpose in other studies (12, 22, 27).

The realization of type strain-specific patterns corresponding to the 42 Legionella species led us to evaluate the intraspecies stability of RAPD profiles by testing 265 environmental and clinical isolates. By observing that multiple well-identified strains of a given species had a core of bands in common, we demonstrated that minimal profiles can be proposed for each species. In fact, this was found even for the bluish white autofluorescent species and the red autofluorescent species, which are otherwise difficult to identify. For L. pneumophila, we were able to obtain a minimal profile for each of the subspecies, thus allowing them to be differentiated from each other. However, in most cases, the level of taxonomic resolution did not reach the serogroup level, in that no serogroup-specific profile was identified when multiple strains were tested. This observation is in agreement with previous findings which show that isolates from different serogroups or different monoclonal antibody subtypes can have identical genotypes (14, 22, 25, 28) and that strains from different L. pneumophila subspecies can belong to a unique serogroup (5, 24). Hence, the claim of others that serogroup-specific profiles can be obtained by RAPD analysis was probably too optimistic and could well be due to the fact that a limited number of strains were tested (type strains only) (1).

Several species were tested with only one isolate because no other isolates were available, and the number of bands forming these species-specific profiles will probably decrease when more strains are tested. This point reinforces the need for exchanges of rarely isolated bacterial species between microbiologists.

Analysis of RAPD profiles with the Taxotron package confirmed the visual identification and allowed isolates of each species to be clearly clustered together. The standardization of the method provided a convenient way to compare patterns obtained from independent gel runs. This method of analysis has proved to be extremely useful for determining the most probable species assignment of a given isolate. The entire procedure can be done in 10 h (2 h for DNA extraction, 5 h for the PCR procedure, and 3 h for electrophoresis) but remains practicable for laboratories having all of the Legionella reference strains. Moreover, it contributes to the identification of potentially new species by grouping a number of unidentified isolates into four additional clusters which were unrelated to those corresponding to the type strains.

In conclusion, it appears that once optimized, the RAPD technique is a rapid, reproducible, and powerful method for identification of Legionella isolates to the species level without further restriction or hybridization.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

We are grateful to M. Goldner for editing the manuscript and to S. Botton, C. Bouveyron, P. Lefevre, D. Falcon de Longevialle, and C. Vallier for technical assistance.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bansal N S, McDonell F. Identification and DNA fingerprinting of Legionella strains by randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:2310–2314. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.9.2310-2314.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Benson R F, Thacker W L, Daneshvar M I, Brenner D J. Legionella waltersii sp. nov. and an unnamed Legionella genomospecies isolated from water in Australia. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:631–634. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-3-631. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bornstein N, Marmet D, Surgot M, Nowicki M, Meugnier H, Fleurette J, Ageron E, Grimont F, Grimont P A D, Thacker W L, Benson R F, Brenner D J. Legionella gratiana sp. nov. isolated from French spa water. Res Microbiol. 1989;140:541–552. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(89)90086-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Brenner D J. Classification of Legionellaceae. Current status and remaining questions. Isr J Med Sci. 1986;22:620–632. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Brenner D J, Steigerwalt A G, Epple P, Bibb W F, McKinney R M, Starnes R W, Colville J M, Selander R K, Edelstein P H, Moss C W. Legionella pneumophila serogroup Lansing 3 isolated from a patient with fatal pneumonia and descriptions of L. pneumophila subsp. L. pneumophila subsp. nov., L. pneumophila subsp. fraseri subsp. nov., and L. pneumophila subsp. pascullei subsp. nov. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1695–1703. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.9.1695-1703.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Brenner D J, Steigerwalt A G, McDade J E. Classification of the Legionnaires’ disease bacterium: Legionella pneumophila, genus novum, species nova, of the family Legionellaceae, familia nova. Ann Intern Med. 1979;90:656–658. doi: 10.7326/0003-4819-90-4-656. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Cherry W B, Pittman B, Harris P P, Hebert G A, Thomason B M, Thacker L, Weaver R E. Detection of Legionnaires disease bacteria by direct immunofluorescent staining. J Clin Microbiol. 1978;8:329–338. doi: 10.1128/jcm.8.3.329-338.1978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cobb B, Clarkson J M. A simple procedure for optimising the polymerase chain reaction (PCR) using modified Taguchi methods. Nucleic Acids Res. 1994;22:3801–3805. doi: 10.1093/nar/22.18.3801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Descheemaeker P, Lammens C, Pot B, Vandamme P, Goosens H. Evaluation of arbitrarily primed PCR analysis and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis of large genomic DNA fragments for identification of enterococci important in human medicine. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:555–561. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-2-555. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Dice L R. Measures of the amount of ecological association between species. Ecology. 1945;26:297–302. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Edelstein P H. Improved semiselective medium for isolation of Legionella pneumophila from contaminated clinical and environmental specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1981;14:298–303. doi: 10.1128/jcm.14.3.298-303.1981. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Gomez-Lus P, Fields B S, Benson R F, Martin W T, O’Connor S P, Black C M. Comparison of arbitrarily primed polymerase chain reaction, ribotyping, and monoclonal antibody analysis for subtyping Legionella pneumophila serogroup 1. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1940–1942. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.7.1940-1942.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Grimont F, Lefèvre M, Ageron E, Grimont P A D. rRNA gene restriction patterns of Legionella species: a molecular identification system. Res Microbiol. 1989;140:615–626. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(89)90193-9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Harrison T G, Saunders N A, Haththotuwa A, Doshi N, Taylor A G. Further evidence that genotypically closely related strains of Legionella pneumophila can express different serogroup specific antigens. J Med Microbiol. 1992;37:155–161. doi: 10.1099/00222615-37-3-155. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Harrison T G, Taylor A G. Identification of legionellae by serological methods. In: Harrison T G, Taylor A G, editors. A laboratory manual for Legionella. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 1988. pp. 57–68. [Google Scholar]

- 16.Harrison T G, Taylor A G. Phenotypic characteristics of legionellae. In: Harrison T G, Taylor A G, editors. A laboratory manual for Legionella. Chichester, England: John Wiley & Sons, Ltd.; 1988. pp. 45–56. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Lambert M A, Moss C W. Cellular fatty acid compositions and isoprenoid quinone contents of 23 Legionella species. J Clin Microbiol. 1989;27:465–473. doi: 10.1128/jcm.27.3.465-473.1989. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Lehman P F, Lin D, Lasker B A. Genotypic identification and characterization of species within the genus Candida by using random amplified polymorphic DNA. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:3249–3254. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.12.3249-3254.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Lo Presti F, Riffard S, Vandenesch F, Reyrolle M, Ronco E, Ichai P, Etienne J. The first clinical isolate of Legionella parisiensis, from a liver transplant patient with pneumonia. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1706–1709. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.7.1706-1709.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Ménard C, Mouton C. Randomly amplified polymorphic DNA analysis confirms the biotyping scheme of Porphyromonas gingivalis. Res Microbiol. 1993;144:445–455. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(93)90052-4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Meunier J-R, Grimont P A D. Factors affecting reproducibility of random amplified polymorphic DNA fingerprinting. Res Microbiol. 1993;144:373–379. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(93)90194-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Pruckler J M, Mermel L A, Benson R F, Giorgio C, Cassiday P K, Breiman R F, Whitney C G, Fields B S. Comparison of Legionella pneumophila isolates by arbitrarily primed PCR and pulsed-field gel electrophoresis: analysis from seven epidemic investigations. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:2872–2875. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.11.2872-2875.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ralph D, McClelland M, Welsh J, Baranton G, Perolat P. Leptospira species categorized by arbitrarily primed polymerase chain reaction (PCR) and by mapped restriction polymorphisms in PCR-amplified rRNA genes. J Bacteriol. 1993;175:973–981. doi: 10.1128/jb.175.4.973-981.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Selander R K, McKinney R M, Whittam T S, Bibb W F, Brenner D J, Nolte F S, Pattison P E. Genetic structure of populations of Legionella pneumophila. J Bacteriol. 1985;163:1021–1037. doi: 10.1128/jb.163.3.1021-1037.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Struelens M J, Maes N, Rost F, Deplano A, Jacobs F, Liesnard C, Bornstein N, Grimont F, Lauwers S, McIntyre M P, Serruys E. Genotypic and phenotypic methods for the investigation of a nosocomial Legionella pneumophila outbreak and efficacy of control measures. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:22–30. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.1.22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Thacker W L, Plikaytis B B, Wilkinson H W. Identification of 22 Legionella species and 33 serogroups with the slide agglutination test. J Clin Microbiol. 1985;21:779–782. doi: 10.1128/jcm.21.5.779-782.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Van Belkum A, Struelens M, Quint W. Typing of Legionella pneumophila strains by polymerase chain reaction-mediated DNA fingerprinting. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:2198–2200. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.8.2198-2200.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Van Ketel R J. Similar DNA restriction endonuclease profiles in strains of Legionella pneumophila from different serogroups. J Clin Microbiol. 1988;26:1838–1841. doi: 10.1128/jcm.26.9.1838-1841.1988. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Verissimo A, Morais P V, Diogo A, Gomes C, Da Costa M S. Characterization of Legionella species by numerical analysis of whole-cell protein electrophoresis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1996;46:41–49. doi: 10.1099/00207713-46-1-41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Welsh J, McClelland M. Fingerprinting genomes using PCR with arbitrary primers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:7213–7218. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.24.7213. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Williams J G K, Kubelik A R, Livak K J, Rafalski J A, Tingey S V. DNA polymorphisms amplified by arbitrary primers are useful as genetic markers. Nucleic Acids Res. 1990;18:6531–6535. doi: 10.1093/nar/18.22.6531. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]