Abstract

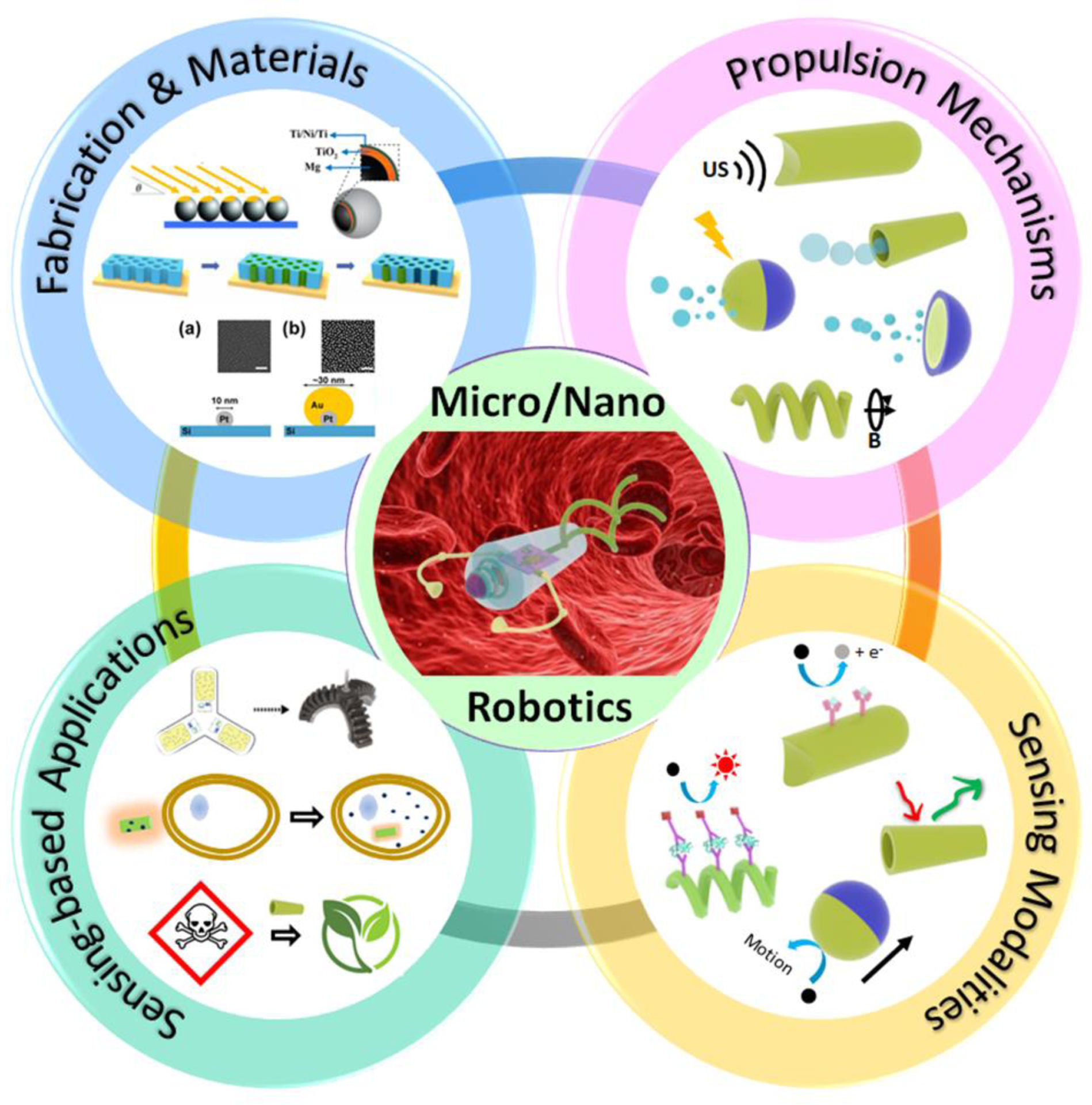

The fields of micro-/nanorobotics have attracted extensive interest from a variety of research communities and witnessed enormous progress in a broad array of applications ranging from basic research, global healthcare and to environmental remediation and protection. In particular, micro-/nanoscale robotics provides an enabling platform for the development of next-generation chemical and biological sensing modalities, owing to their unique advantages as programmable, selfsustainable, and/or autonomous mobile carriers to accommodate and promote physical and chemical processes. In this review, we intent to provide an overview of the state-of-the-art development of this area and share our perspective in the future trend. This review starts with a general introduction of micro-nanorobotics and the commonly used methodsfor their propulsion in solution, along with commonly used methods in micro-/nanorobot fabrication. Next, we comprehensively summarize the current status of the micro/nanorobotic research in relevance to chemical and biological sensing (e.g., motion-based sensing, optical sensing, and electrochemical sensing). Following that, we provide an overview of the primary challenges currently faced in the micro-/nanorobotic research. Finally, we conclude this review by providing our perspective detailing the future application of soft robotics in chemical and biological sensing.

1. Introduction

More than half a century ago, Richard Feynman explored the concept of a swallowable surgeon in his famous lecture entitled There’s Plenty of Room at the Bottom. In his speech, Feynman imagined the possibility that one day we may have small “mechanical surgeons” able to explore structures in the body as small as the blood vessels and aid in performing both operations and medical diagnoses1. Over the past few decades, mechanical and robotic systems have completely reshaped human society. And in present day, state-of-the-art micro- and nanotechnology have greatly fueled the miniaturization of robotic systems, bringing the concept of “swallowing a surgeon” closer to fruition.

Micro-/nanorobots, also referred to as micro-/nanomotors, micro-/nanomachines or micro-/nanoengines by researchers, are functional machines with sizes ranging from nanometers to micrometers. Similar to traditional robotic systems, micro-/nanorobots rely on utilization or conversion of external energy to actuate their autonomous or tethered mechanical movements, which encompass a variety of different actuation mechanisms (see Propulsion Techniques). Various configurations have also been developed for micro-/nanorobotics, including tubular structure, micro-/nanorod, helical spiral, Janus particle, and biohybrid structures2. Through years of multifaceted effort, the field of micro-/nanorobotics has become increasingly more interdisciplinary, attracting researchers from fields ranging from engineering and medicine to even material science and chemistry.

Despite the enormous potential these devices hold and the significant amount of progress accomplished in the past few years, there still exists a few major challenges which stand in the way of future implementation of this technology - the most important of which being locomotion at the micro-/nanoscale.

Any micro-/nanorobot moving in a fluid sample is subject to two major forces: inertial and viscous forces. The Reynold’s number ( – where represents the density of the fluid, represents velocity, represents length, and represents dynamic viscosity) provides a ratio of inertial forces to viscous forces present in a flowing fluid. While the movement of larger animals (e.g., fish) in fluids occurs at high Reynolds numbers (where inertial forces dominate), the movement of microorganisms (comparable in size to a microrobot) occurs at very low Reynolds numbers - indicative of an overwhelming viscous forces at hand. With the typical small size of micro-/nanorobots, continuous work must be done to maintain continuous motion in solution3.

Another challenge presents itself in that micro-/nanorobots are currently not able to be powered using traditional forms of power generation (i.e., batteries, generators, etc.) - meaning that alternative fuel sources must be used, which ideally should be biocompatible and remotely controllable. In a highly viscous medium such as blood (where miniscule amount of inertial force presents), the power supplied must be continuous as well. To overcome these challenges, specific propulsion strategies have been proposed to facilitate their motion in low-Reynolds number environments.

Therefore, in this work, we begin by reviewing the most commonly used propulsion techniques. Taking into account their extremely small size, flexible controllability, and versatile functionalization, micro-/nanorobotics are being increasingly recognized as next-generation platforms for many applications, including biomedicine, biosensing and environmental remediations4–9. Specifically, as a platform for “chemistry-on-the-fly”, the motion of micro-/nanorobotics in fluids can accelerate reaction processes, which is extremely desirable for the liquid-based sensing. Therefore, in the next section, we focus on the application of micro-/nanorobotics in bio- and chemical sensing. This section is outlined by different sensing strategies – including motion-based sensing, optical sensing, and electrochemical sensing. The following is a survey of state-of-the-art development in sensing-based applications, for which the tasks are based on the sensing of micro-/nanorobotics to specific molecular species, the environment, or to each other.

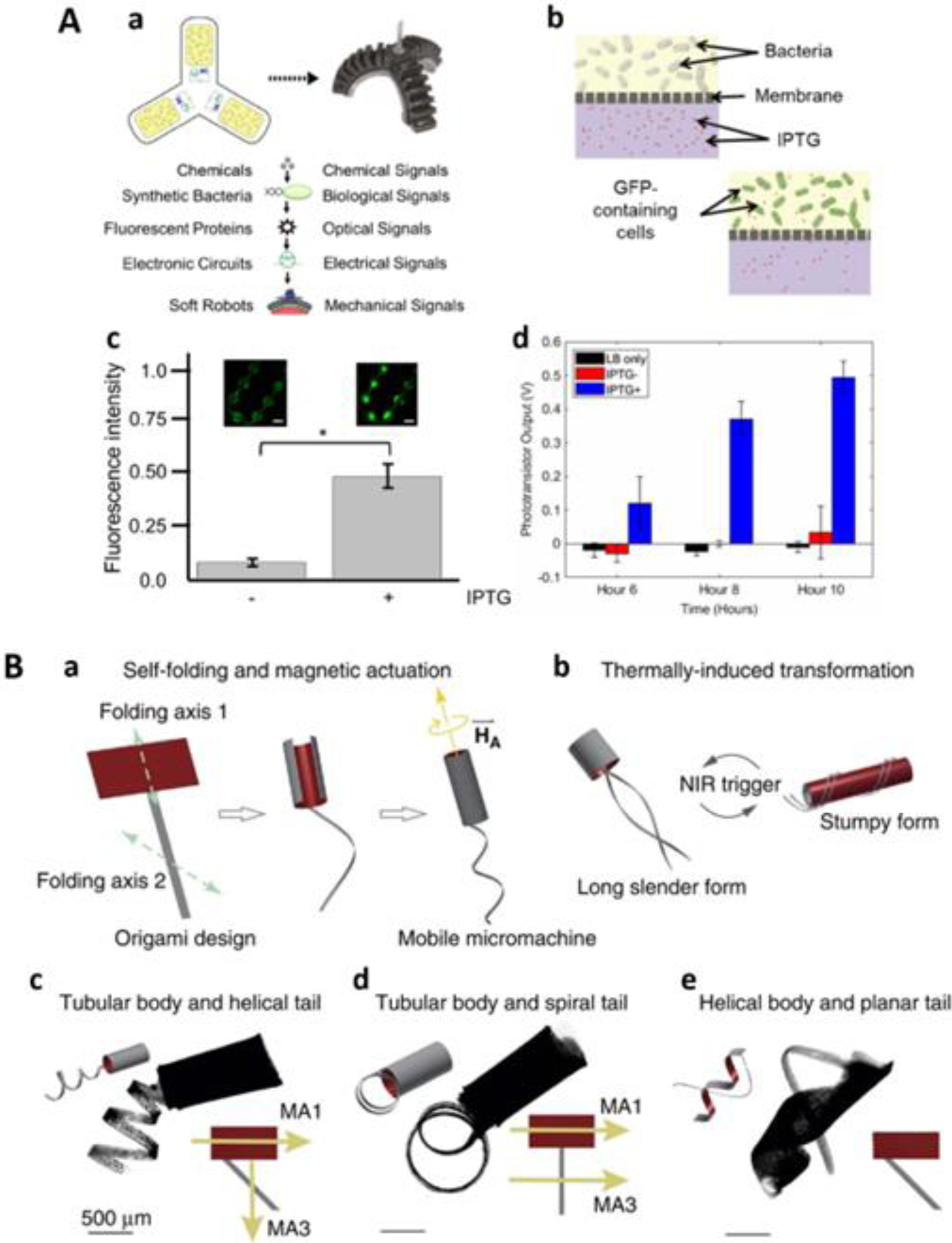

Even though traditional micro-/nanorobots have indisputable advantages that make them favorable in sensing applications, there are still several long-standing limitations preventing further development in sensing. Meanwhile, as an alternative to conventional rigid robotic systems, soft robotics has rapidly evolved over the past decade to address some of the critical problems encountered by rigid robotics, including safety, conformability and compatibility10. These inherent advantages have led to many instances of soft robotics use in the biomedical field11, 12. However, we believe that the participation of soft robotics in bio- and chemical sensing is somewhat underrepresented. Upon comparison with traditional, rigid micro-/nanorobotics, some of the unique characteristics of soft robotics can be potentially used to supplement or remedy the drawbacks of micro-/nanorobotics, especially in the field of bio- and chemical sensing. So finally, we propose the application of (micro) soft robotics in bio- and chemical sensing to push the boundaries of this field even further than before.

2. Propulsion Techniques

Micro-/nanorobots, resulting from their small size, inhabit environments characterized by very low Reynolds numbers and are unable to be powered via traditional power sources. In order for these devices to be able to move in solution, their means of propulsion must be both continuous as well as wireless. In addition, some applications of this technology may require the method of propulsion to be biocompatible as well. In this section, we will describe the most common propulsion methods used in modern micro-/nanorobotics work. Great care will be taken in addressing the mechanism of each method - as well as their advantages and limitations.

2.1. Chemical Propulsion

Using chemical propulsion techniques, a swimming micro-/nanorobot converts chemical energy into kinetic energy for movement. This means for energy conversion is in many cases provided by the use of a metal or metal catalyst - allowing the machine to autonomously propel itself when exposed to fuel in its immediate microenvironment13. Since inertia is negligible in an environment characterized by a low Reynold’s number, this chemical conversion must be continuous in order for motion in solution to be maintained14. There are three main propulsion models of autonomous chemical propulsion: self-diffusiophoresis, self-electrophoresis, and bubble propulsion.

Self-diffusiophoretic motion (Figure 2A)15 is caused by the presence of concentration gradients (which stem from the asymmetric release of reaction products) around the micro-/nanomotors which work to drive the motors forward16. Janus particles have long been associated with this propulsion model - receiving their name from having two hemispheres with distinct chemical/catalytic characteristics17. Their inherent asymmetry allows these microspheres to propel in solution via the generation of reaction products on only one side of the particle. In fact, the particle must generate more products than reactants, producing an asymmetric net repulsive interaction with the particle that pushes it forward. A common example of this type of reaction is the catalytic decomposition of hydrogen peroxide - producing both oxygen and water molecules18. More than a decade ago, Howse et al fabricated polystyrene spheres and coated one side of the spheres with platinum. The metal coating catalyzed the reduction of hydrogen peroxide, allowing the particles to move in a predominantly directed way on a short time scale. This work used the simplest method of producing Janus particles - that being, thin metal film deposition on top of microspheres typically made of silicon dioxide or polystyrene (however, a variety of other fabrication techniques have been reported)19.

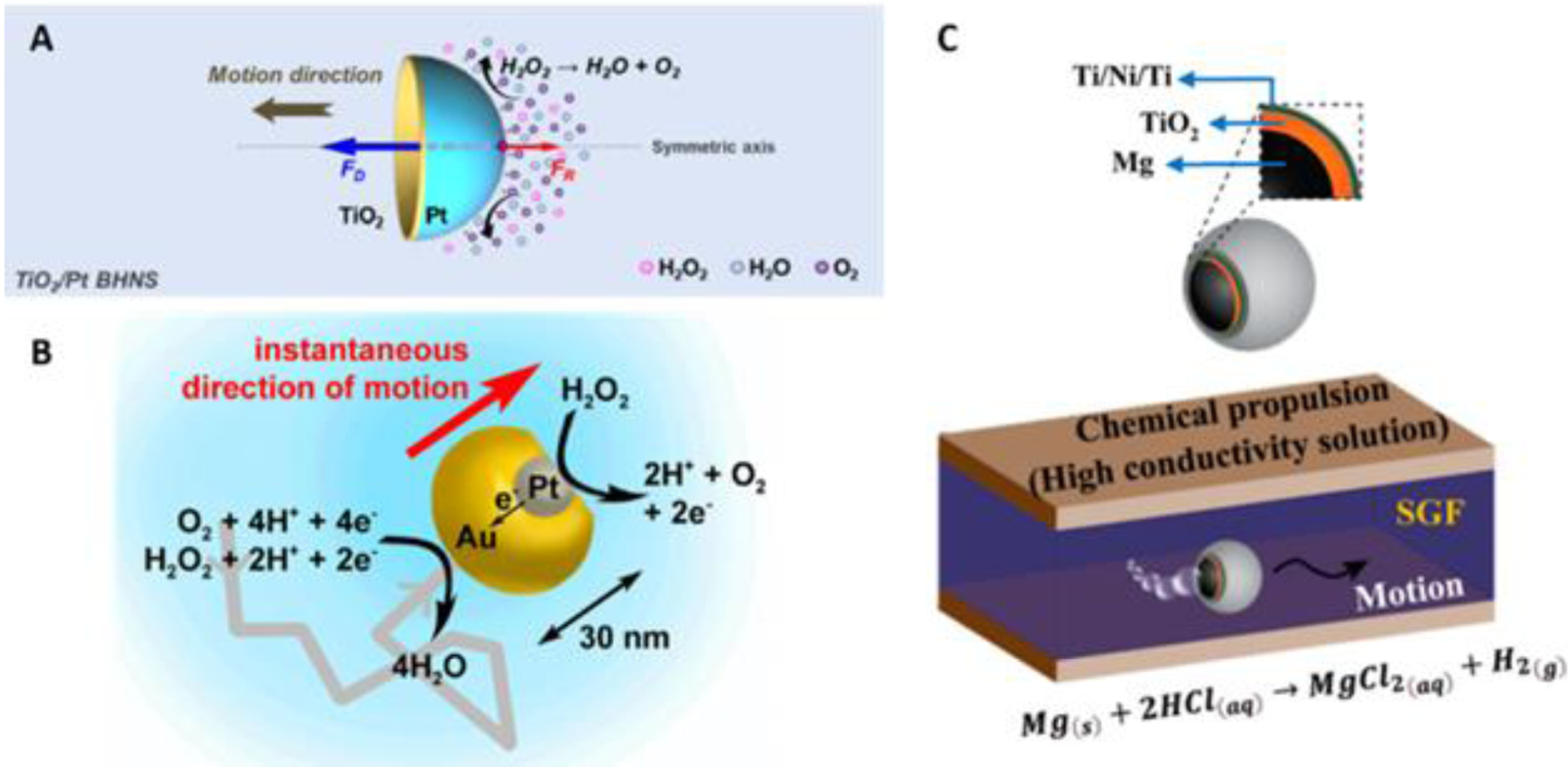

Figure 2. Chemical Propulsion in Solution.

(A) Pt-TiO2 nanoshell undergoing self-diffusiophoresis in solution (reprinted from ref. 15 with permission, copyright 2022, American Chemical Society). (B) Au-Pt Janus nanoparticle propelled via self-electrophoresis mechanism (reprinted from ref. 20 with permission, copyright 2014, American Chemical Society). (C) Structure (above) of Mg-core micromotor and its movement in solution via bubble propulsion (below) (reprinted from ref. 21 with permission, copyright 2022, American Chemical Society).

Self-electrophoretic motion is very similar to the previously mentioned self-diffusiophoretic motion (albeit, more complicated) - stemming from surface reactions which create a heterogeneous distribution of ions in solution. This distribution of ions essentially creates an electric field that works to propel the micro-/nanorobotics16. Self-electrophoresis is typically exhibited by bimetallic nanomotors, having one segment dedicated to reduction and the other for oxidation. Calling back to the example of hydrogen peroxide decomposition, an Au/Pt nanomotor can oxidize hydrogen peroxide at the platinum anodic segment and reduce it at the gold cathodic segment - acting in a similar manner to that of an electrochemical cell (Figure 2B)20. What happens is the anode produces large amounts of protons and electrons, and an electric field is developed that points toward the cathode. As protons travel towards the cathode, fluid is dragged along with it, which results in movement in the opposite direction with the anode facing forward17.

Micro-/nanorobots which move via bubble propulsion use the production of bubbles as a means of propulsion and are known for their light weight and small size as well as their high speed and propulsion force in solution (Figure 2C)21. Bubble-propelled micro-/nanorobots come in a variety of shapes - including rod- and tubular shaped22. The tubular geometry typically involves an inner catalytic surface which decomposes chemical fuel into gas bubbles, which rapidly combine and grow into larger bubbles via effective nucleation and eventually expel out due to pressure. Fabrication of these types of micro-/nanorobotics is typically done using a roll-up technique; however, use of template-assisted electrochemical deposition techniques has been reported as well as a layer-by-layer assembly method (See Section 3. Fabrication Methods). On the other hand, rod-shaped micro-/nanorobotics are completely solid, containing two or more metal segments prepared via an electrochemical deposition technique17.

In the case of bubble propulsion, a considerable amount of research has been focused on using the catalytic decomposition of hydrogen peroxide by platinum metal to evolve water and oxygen bubbles as a means of high-speed propulsion - with the change in momentum during bubble ejection being speculated to drive motion in the direction opposite of the bubble stream23. Interestingly, this change in momentum can be modulated directly via the use of external stimuli (including light, temperature, and acoustic fields) in order to directly control the speed of micro/nanomotors14. For example, Li et al developed photoactivated TiO2/Au Janus micromotors fabricated by asymmetrically coating gold on the exposed surface of AmTiO2 microspheres - the speed of which could be modulated using the intensity of UV radiation with a response rate less than 0.1 seconds24. In an impressive feat, Magdanz et al exploited the thermoresponsive nature of poly(N-isopropylacrylamide) (PNIPAM) film, creating flexible, self-propelled microjets which could reversibly fold and unfold into a tubular shape depending on solution temperature. Bubble formation was only observed when the film was folded (cooler temperatures) - as the tubular shape allowed generated oxygen to accumulate into visible bubbles instead of quickly diffusing into the surrounding solution. It was observed that the velocity of the microjets could be controlled via changing the radius of the tube25. This concept of speed modulation has been taken one step further by Wu et al, who demonstrated on-demand motion of catalytic microengines dependent upon NIR illumination. Illumination of the microengine with a focused NIR laser could induce a fast thermally modulated motion, reaching a maximum speed of 62 m/s. However, after leaving the laser spot, the micromotor would soon come to a standstill26.

Lacking inherent directional motion, the movement of bubble-propelled micro-/nanorobots typically follow random trajectories in three dimensions14. However, magnetic material can be incorporated within the structure of the micromotor in order to control the direction of propulsion. For example, Demirbuken et al have recently described the fabrication of a self-propelled PAPBA/Pt/Pt-Ni/Pt nanomotor - the direction of which can be changed via use of a magnetic field27. The use of fuel concentration gradients has also been demonstrated as a means of directional control14. A common criticism of this specific means of propulsion is its prevalent use of biologically incompatible catalysts and fuels (including platinum and hydrogen peroxide), limiting its potential use for in vivo and biomedical applications23. However, what the method lacks in terms of biocompatibility, it makes up for it, with the low cost associated with the technique as well as easy integration of the technology into the nano scale.

2.2. Magnetic Propulsion

The use of magnetic fields as a means of micro-/nanorobotic propulsion has generated considerable interest in the biomedical micro-/nanorobotics community due to its advantages of remote/wireless operation, deep penetration into the tissues and body, directed propulsion, and low adverse effects on living organisms and tissues (biocompatibility)13, 14. The working principle behind this technique can be explained in the following sentences. When a magnetic micro-/nanorobot (typically containing either ferromagnetic materials like Ni, Fe, or Co or paramagnetic materials such as Fe2O3) of volume is placed in an external magnetic field (with representing the magnetic flux density), the device will become magnetized (magnetization represented using ). If subject to a magnetic field gradient (), the device will experience a magnetic force (, either attractive or repulsive). In order to minimize magnetic energy when exposed to the magnetic field, the robot will then experience a torque () - causing the robot to orient its body so that it aligns with the magnetic field. The direction of the magnetic dipole moment and the external magnetic field controls the torque. A space-varying (gradient magnetic field) or time-varying (rotating, oscillating or pulsed) magnetic field can therefore be used in order to continuously propel the robot in solution13, 28.

The equations for the magnetic force (Equation 1) and magnetic torque (Equation 2) of a magnetic object inside of a magnetic field are given below:

| (1) |

| (2) |

By carefully adjusting the rotation axis of the magnetic field, the micro-/nanorobot can be steered in different directions. In fact, magnetic fields offer as much as six degrees of freedom for motion - allowing absolute spatial manipulation depending on the actuation system28. Essentially, magnetic forces generated in gradient fields and magnetic torque act in a similar way to fuel sources seen in chemical propulsion techniques in order to cause micro-/nanorobots to continuously move in solutions where viscous forces greatly overpower inertial ones.

There are three main translational mechanisms associated with the movement of micro-/nanorobots undergoing magnetic actuation: corkscrew motion, surface-assisted propulsion, and undulatory (traveling-wave) motion. As discussed in Purcell’s famous 1977 paper titled Life at Low Reynolds Number, time-symmetric, reciprocal motion (e.g., the swimming motion of a scallop which is dependent on the opening and closing of a single hinge) cannot create a net propulsive force in a highly viscous fluid. Therefore, microscopic organisms must produce non-reciprocal motion in order to produce movement in Newtonian liquids29. One of the ways in which non-reciprocal motion can be achieved is through use of a non-symmetric or chiral structure (e.g., a helical structure). In mimicking the corkscrew-like motion prokaryotic cells perform by rotating their flagella, micro-/nanorobotics (either fully helical in structure or consisting of a magnetic head attached to a helical tail) are able to accomplish a similar motion by using external rotating magnetic fields (Figure 3A)30. Since a magnetic object, upon experiencing magnetic torque, will align its easy magnetization axis parallel with the direction of a local homogeneous field, a torque that is continuously applied under an external rotating field creates rotational movement of the object’s body. This steady rotation can be converted into translational motion - the direction of which is parallel with the axis of rotation of a two-dimensional planar rotating field. The direction of this motion (in terms of forward versus backward) can be changed by simply reversing the direction of rotation of the applied magnetic field28, 31.

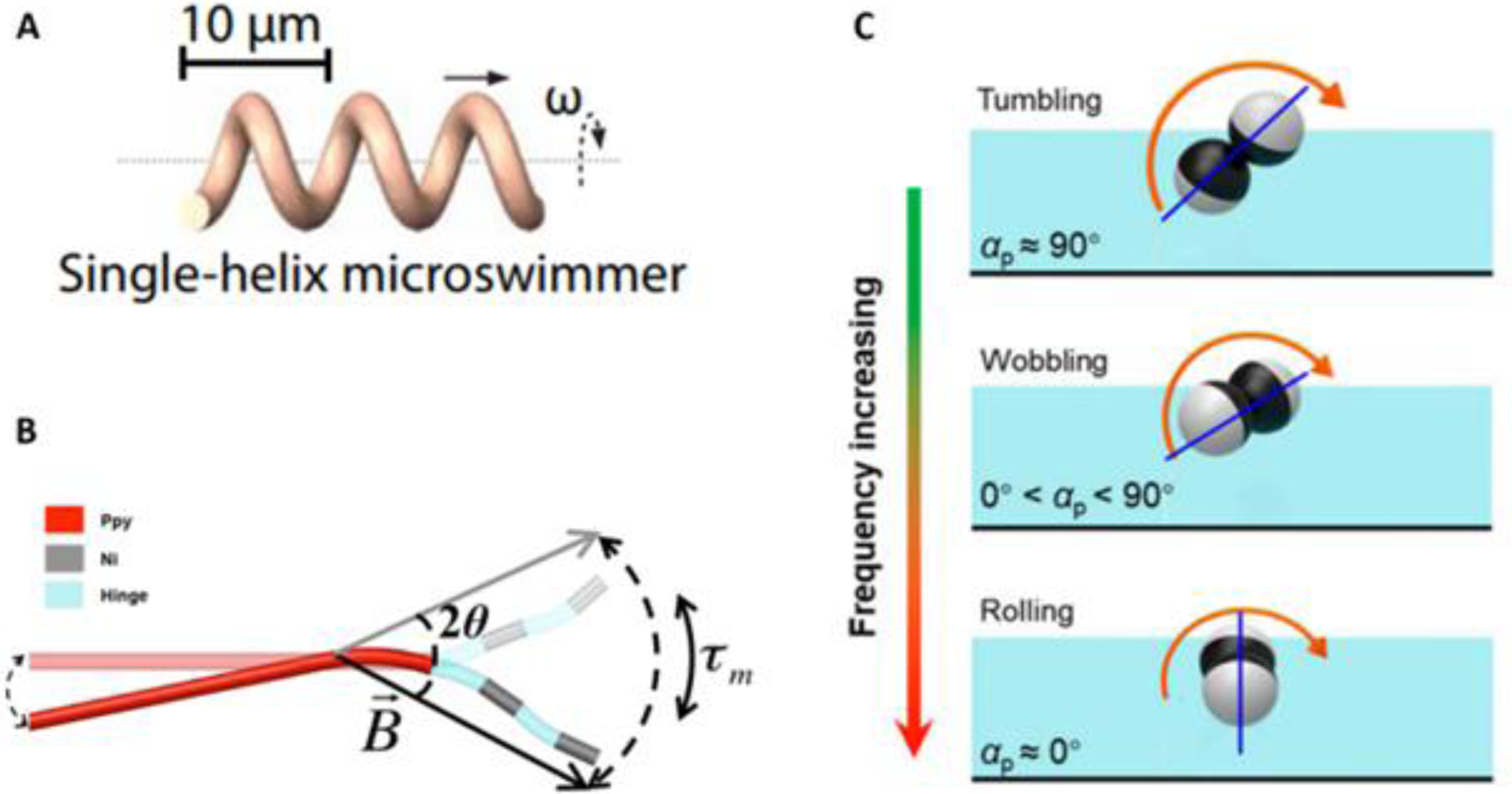

Figure 3. Propulsion via Magnetic Fields Achieved Using Various Geometries.

(A) Micro-/nanorobotics can mimic flagellar movements of prokaryotes via use of a helical structure. Application of external magnetic fields help to create corkscrew-like motion (reprinted from ref. 30 with permission, copyright 2021, The American Association for the Advancement of Science). (B) Three-link polypyrrole nanoswimmer comprising of magnetic nickel segments connected by flexible polymer heniges (reprinted from ref. 34 with permission, copyright 2015, American Chemical Society). (C) Janus microdimer moving via surface-assisted propulsion under a rotating magnetic field (reprinted from ref. 32 with permission, copyright 2021, Frontiers Media S.A.).

Similar in principle to how corkscrew motion is achieved, surface-assisted motion gets its name from the use of a physical boundary to break spatial symmetry for the purpose of generating a walking or rolling motion of micro-/nanorobots at low Reynolds numbers31. These micro-/nanorobots are commonly called “surface walkers” or “surface rollers” and can take on a variety of shapes including nanorods and microtubes as well as Janus particles (Figure 3C)32. This type of motion is achieved in viscous solution by magnetically actuating a magnetic micro- or nanostructure lying near a surface using a rotating or oscillating magnetic field - the dynamics and mechanism by which is controlled by a variety of factors including: fluid properties, boundary features, and the degree of confinement. While surfaces have traditionally been flat, movement of micro-/nanorobots on topographic surfaces has been achieved28. A notable example is described in Wang et al in which magnetic nanoparticles were able to be actuated on top of a sample of uneven biological tissue33.

The third way in which non-reciprocal motion can be achieved is through non-symmetric actuation. Mimicking the motion of cilia and flagella, an elastic component is typically crucial to achieve traveling-wave propulsion. Magnetic micro-/nanorobots capable of undulatory motion have typically been created by either adding an elastic tail to a rigid head or by connecting nanowires together via flexible segments (Figure 3B)34. An oscillating magnetic field can then be used to break temporal symmetry and create an effective net displacement via the thrust from the backward-traveling wave generated by the flexible structure28, 31. For example, Li et al created a magnetically propelled fish-like nanoswimmer consisting of a gold segment as both the head and caudal fin, two nickel segments as the body, and three flexible silver hinges linking each segment. When actuated by an oscillating magnetic field, the flexible nickel segments caused the body and fin to periodically bend, generating thrust via traveling-wave motions35.

However, it is important to note that there are instances where Purcell’s theorem does not hold. For example, an object undergoing reciprocal motion in a common Newtonian fluid like water can undergo a net displacement if it experiences anisotropic drag36. Non-Newtonian fluids are an entire domain in which the scallop theorem does not hold, and fortunately for researchers, many bodily fluids of interest to application of micro-/nanoswimmers (including blood) are classified as non-Newtonian. With this in mind, work from Qui and team have demonstrated creation of a symmetric magnetic, single hinge “micro-scallop” able to propel in non-Newtonian fluids by reciprocal motion at low Reynolds numbers37.

2.3. Acoustic Propulsion

With the strong medical interest in developing micro-/nanorobotic systems for applications including drug delivery, minimally invasive surgeries, and biosensing in vivo, there has been a great effort to develop biocompatible methods of powering these systems - one of these methods being the use of acoustic energy. The medical field is no stranger to using acoustic waves - with ultrasound machines being a common sight in hospitals throughout the world. Acoustic (or ultrasound) propulsion has emerged as a promising off-board approach to micro-/nanorobot propulsion in the last decade due to its inherent biocompatibility and ability to be used with a wide variety of different particle shapes, sizes, materials and solutions23, 38.

In this technique, micro-/nanorobots convert excitation energy in the frequency (MHz range) and power (up to several W/cm2) range into axial movement39. However, despite all that has been studied, our understanding of the mechanism of acoustic propulsion is incomplete13. Even our understanding of the influence design properties has on the propulsion mechanism is very limited. A few known design requirements include the importance of a motor having shape or density asymmetry as well as the ultrasound intensity and particle size needing to be sufficiently large enough in order to ensure acoustic propulsion dominates random Brownian motion. However, a clear hierarchical relationship between these design parameters has not yet been proposed38. For example, the directionality of motors composed of a single material is controlled via the motor’s shape asymmetry - whereas for bimetallic motors the directionality is controlled via both the density of its materials as well as resonance mode asymmetries40.

Multiple mechanisms have been proposed in an attempt to explain propulsion of micro-/nanorods via acoustic waves. An early mechanism proposed that the axial motion of micro-/nanorods could be explained by a process known as “self-acoustophoresis” in which the asymmetric shape of the rods leads to asymmetric scattering of acoustic pressure on the rod’s surface to generate directional motion. Around a year later, a newer physical mechanism was proposed in which metallic rods were modeled as axisymmetric rigid near spheres in a standing acoustic wave and acted as a rigid body which moves in a uniformly oscillating velocity field. Oscillation in the fluid is considered to produce steady streaming on the particle’s surface to generate propulsion - the force of this propulsion stemming from the rod’s asymmetric shape. This model explained the faster motion of more concave rods as well as the need for a large difference in density between the rods and surrounding medium. Later on, a general mechanism was proposed by Collis et al which considers both shape and density effects39, 41. Debate around the mechanism for this propulsion technique indicates there is still much more to learn about this technique. A more in-depth understanding of the mechanism behind acoustic propulsion could lead to improved micro-/nanorobot actuation performance as well as a myriad of more efficient micro-/nanorobot designs.

2.4. Light-driven Propulsion

The use of light as a renewable source of power for the movement of micro-/nanobots offers a variety of benefits. A main source of attraction comes from the method’s variety of adjustable encoding modes (including wavelength, light intensity and polarization) as well as its high spatio-temporal precision which has proven useful for the actuation of single, multiple, and even swarms of micro-/nanorobots23, 42. The possibility of concentrating the beam size down to sub-micron levels offers considerable promise in future applications13. However, the limitation of the low penetration depths in tissue could perhaps limit in vivo applications of these machines to actuation at near skin positions23. Once a locomotive object has been scaled down to a low Reynolds number system, it requires a continuous driving force in order to allow it to move against overwhelming viscous forces. In order to achieve movement, a number of light-driven propulsion schemes have been created, which can be divided into two broad categories: propulsion via electric field and non-electric field driven propulsion.

Propulsion via an electric field typically occurs either via self-electrophoresis or electrolyte diffusiophoresis. In self-electrophoresis (Figure 4B)43, the electric field needed for propulsion is generated by cathodic and anodic photochemical reactions separated in space which create an asymmetric distribution of ions across the particle. Specifically, this electrolyte gradient stems from the asymmetric generation or depletion of photogenerated electrolyte ions under irradiation. Once generated, the charged particles move in response to the local electric field42. A common example can be seen by observing Au-Pt bimetallic nanorods. The oxidation of H2O2 preferentially occurs at the anode (Pt) end whereas the reduction of H2O2 occurs at the cathode (Au) - leading to a higher concentration of protons near the platinum end and a lower concentration near the gold end. Given a proton’s positive charge, an electric field develops, pointing from the platinum end to the gold end - allowing the negatively charged nanorod to move in response to the self-generated electric field.

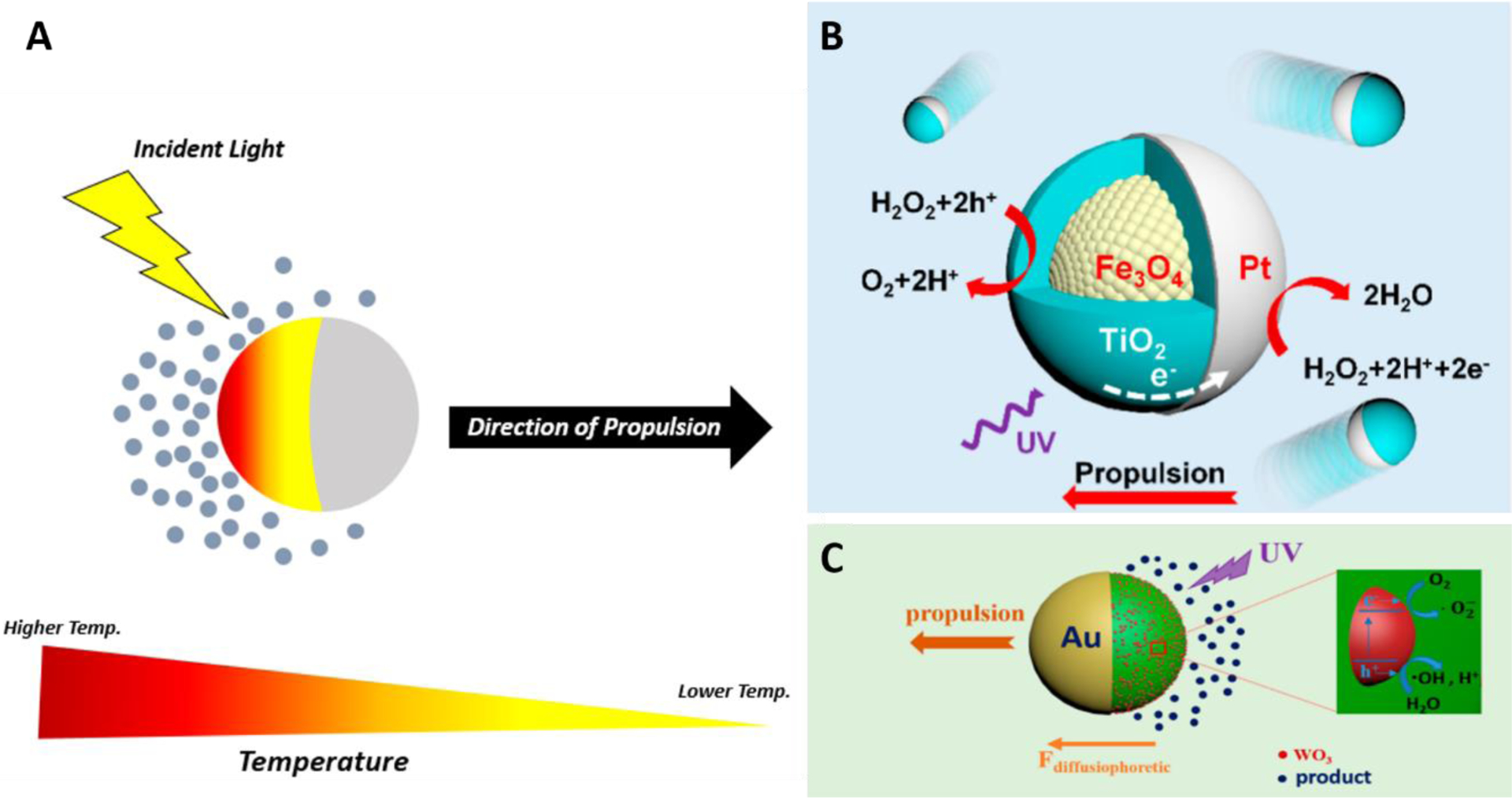

Figure 4. The Main Mechanisms of Light-induced Propulsion of Micro-/Nanorobotics.

(A) Self-thermophoresis. (B) Self-electrophoresis (reprinted from ref. 43 with permission, copyright 2022, American Chemical Society). (C) Self-diffusiophoresis (reprinted from ref. 44 with permission, copyright 2017, American Chemical Society).

However, in electrolyte diffusiophoresis (Figure 4C)44, the cathodic and anodic reactions occur in the same area, generating ions typically on one side of the micro-/nanorobot. Owing to the different diffusivities of cations and anions generated (electrophoretic term), a diffusion-induced electric field can be established along a concentration gradient - creating propulsion. Cations and anions can also interact with the double layer of the charged particle differently, resulting in a pressure which can move the particle. However, this effect (known as the chemophoretic effect) is usually negligible - with the directions of diffusiophoretic flows largely governed by the electrophoretic effect, unless the diffusivities of the cations and anions are very similar42. Equation 3 summarizes the two effects on particle velocity () in the presence of a nearby charged surface wall16:

| (3) |

where represents the concentration gradient of a monovalent salt, represents the bulk concentration of ions, and represent cation and anion diffusion coefficients, is the Boltzmann constant, represents the charge of an electron, is absolute temperature, is the viscosity of solution, represent the solution’s dielectric permittivity, and represent the zeta potentials of both the particle and wall, and corresponds to

| (4) |

Electroosmotic flow can also occur, depending on the presence of a charged substrate. However, this phenomenon depends on the relative magnitudes of the surface charges on the particle and the substrate. A “competition” between both electrophoretic diffusiophoresis and electroosmosis results in the particle moving in either direction. In fact, in both mechanisms, the generated electric field can induce electroosmotic flow, and the migration speed of the particle in both cases can be estimated using the Helmholtz–Smoluchowski equation for electroosmotic velocity42:

| (5) |

where is the migration velocity of the particle, represents the solution permittivity, is the zeta potential of the particle’s surface, is the viscosity of the solution, and is the electric field.

Non-electric field driven propulsion mechanisms include self-thermophoresis and light-induced bubble propulsion. In self-thermophoresis (Figure 4A), the micro-/nanorobot used is typically coated asymmetrically with light-absorbing materials (typically gold) as a means of encouraging directed motion - as opposed to the enhanced Brownian motion observed when symmetrically coated. The coating process can be accomplished via sputter coating under vacuum (in the case of Janus particles) as well as a template-assisted layer by layer process combined with a seeding-growth procedure (in the case of tube motors, colloquially known as micro-/nanorockets)42, 45. Absorption of light by the coating generates a local temperature gradient along the particle, creating a net thermophoretic force proportional to the local temperature gradient () and the particle diameter () as described in the equation (6)46:

| (6) |

where the coefficient is the diameter of a particle, is the viscosity of the fluid, is the fluid thermal conductivity, is the particle thermal conductivity, and is the fluid density. Simply put, the temperature gradient creates a situation in which the frequency of collisions between one (warmer) side of the micro-/nanorobot and the surrounding molecules is higher than that on the other (cooler) side, thus pushing the motor away in the direction opposite of its heated side45.

Light-induced bubble propulsion makes use of high-performance photocatalysts (e.g., TiO2 and WO3) to generate a directed stream of bubbles via a photochemical reaction. In order to form bubbles, these photocatalysts are typically spatially confined (e.g., tubular structure), allowing gases to accumulate and inhibiting their diffusion in solution. Light acts as a “switch”, allowing the reaction to be turned “on” and “off.” The release of a jet of bubbles during illumination results in a continuous change in momentum which propels the motor through the solution in the direction opposite from the side of bubble generation42.

Interestingly, Gibbs and Zhao developed an expression for the velocity of a micro-/nanorobot actuated via bubble propulsion, showing that the velocity is proportional to the concentration of fuel as well as , which determine how much gas is produced46:

| (7) |

where represents the number of bubbles, is the universal gas constant, 𝑇 is the temperature, ⍴ is the density of oxygen gas produced, is the liquid’s interfacial tension, 𝑐 is the bulk concentration of H2O2 fuel, and is the Langmuir adsorption constant.

2.5. Propulsion/Control via Multiple Energy Sources

Micro-/nanorobots are not limited to making use of only one of the above-mentioned means of propulsion. In fact, there are quite a few recent notable examples in which motors have been designed with two or more methods of control in mind. These “hybrid” robots incorporate two or more energy sources for navigation and control and are therefore better able to respond to changes in complicated environments, extending their utility in multiple applications both in vivo and ex vivo23.

A common example of hybrid micro-/nanorobots includes those which have a main mechanism for propulsion and a separate means of directional control (typically magnetic fields). For example, Wu et al have developed micromotors for cancer treatment which rely on the enzymatic reaction of glucose oxidase with glucose as a chemical fuel and the incorporation of magnetic Fe3O4 nanoparticles as a means of controlling the robot’s direction47. Recently, Demirbuken et al have described the fabrication of a self-propelled PAPBA/Pt/PteNi/Pt nanomotor - the direction of which can be changed via use of a magnetic field27. Using computer simulations, Nitschke et al have proposed a biocompatible method for the collective guiding of acoustically propelled micro- and nanoparticles in which a space- and time-dependent ultrasonic field propels the particles, and a time-dependent magnetic field collectively aligns their propulsion directions38.

However, other micro-/nanorobotics have two or more means of propulsion. A notable example would be the pH responsive mesoporous silica-Pt@Au Janus nanomotors created by Xing et al. In hydrogen peroxide solution, these nanomotors undergo self-diffusiophoresis due to the catalytic decomposition of peroxide. However, the solution’s weak acidity can cause the disassembly/reassembly of gold nanoparticles - leading to reconstruction of the nanomotor and a change in propulsion mechanism from self-diffusiophoresis to self-electrophoresis. The asymmetric, aggregated gold nanoparticles also permit the generation of a thermal gradient via laser irradiation - leading to an additional self-thermophoresis mechanism as well48. Karaca and group have reported gold-nickel nanowires able to undergo both magnetic and acoustic propulsion. In fact, both propulsion methods could be activated at the same time - creating impressive speeds as high as 120 m/s49. Taking inspiration from nature, Shao et al have reported what they call “twin-engine” nanomotors based on the structure of stomatocytes in which the enzyme catalase was loaded as well as a hemispherical gold coating. These Janus nanomotors could be exposed to both hydrogen peroxide and near-infrared laser light - creating two competing driving forces and resulting in a “seesaw” motion. Modulation of this “seesaw” effect via changing the peroxide concentration and laser power permitted the ability to switch between motile modes50. Similarly, Yuan et al have reported creating graphene oxide Janus micromotors having an adaptive propulsion mechanism, allowing the motors to use nearby peroxide as a chemical fuel or magnetic actuation via an external magnetic field51.

3. Fabrication Methods

A variety of techniques have been employed over the past few decades to create micro-/nanorobots – with advances in micro-/nanofabrication having made great contributions towards the fabrication of these small-scale robotic devices. Particularly, photolithography as well as certain deposition and etching techniques are extensively used in micro/-nanorobot fabrication – along with other fabrication techniques including additive manufacturing. This section aims to provide a review of some of the most commonly used fabrication methods in micro- and nanorobotics.

3.1. Photolithography

The conventional clean room process of photolithography involves the use of a light-sensitive material (photoresist) and a custom photolithographic mask to create designed patterns on a target substrate. Upon illumination of the photoresist, the material changes its solubility properties, leaving the user with a structure having raised features corresponding to the photomask after development52. The resolution of this high throughput technique spans from the nanometer to the micrometer range, offering researchers the ability to create intricate patterns and structures with high precision53.

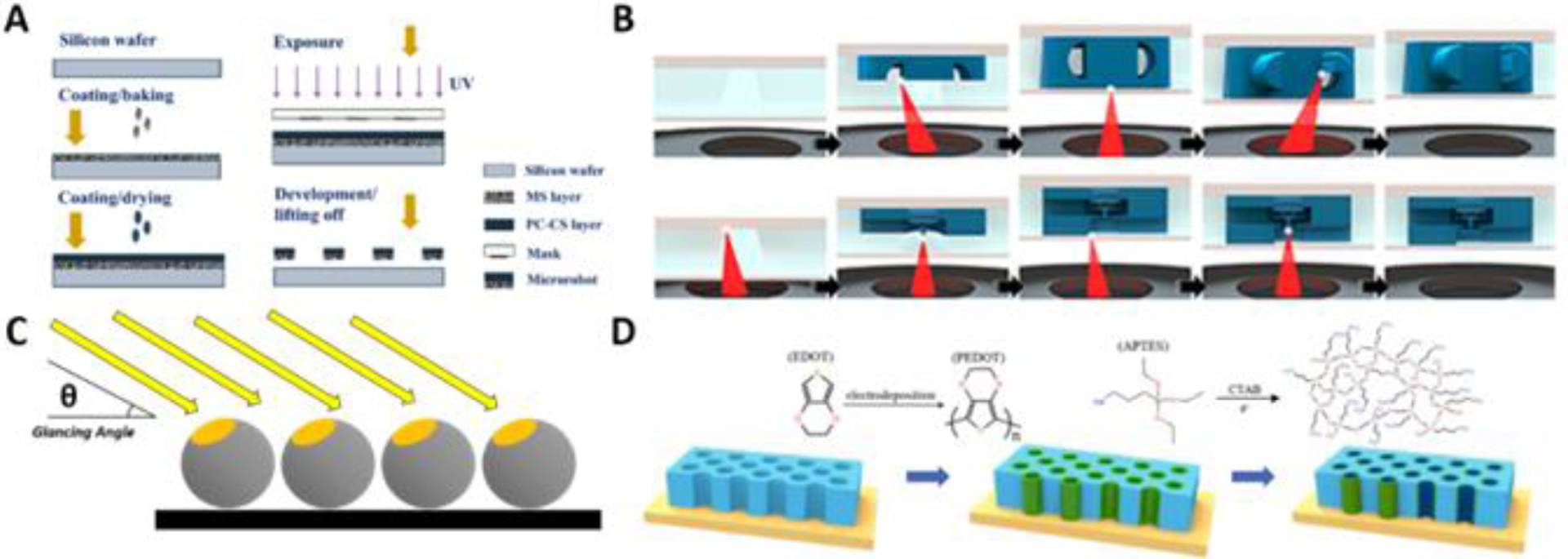

Recent work by Wang et al describes the use of a layer-by-layer optical photolithographic technique to produce L-shaped magnetic microrobots (Figure 5A)54. Briefly, after cleaning a silicon wafer using a plasma cleaner, a layer of magnetic nanoparticle solution was spin coated and baked on top of the wafer to form the first layer. A photo-crosslinkable chitosan solution was then spin coated on top of the magnetic solution layer and dried to form a photo-crosslinkable chitosan film. With use of a photomask, the sample underwent ultraviolet light illumination and subsequent development, producing chitosan-based achiral planar microrobots. Similar work reported by Tan and Cappelleri uses both conventional photolithography and two-photon polymerization (TPP) to create helical swimming microrobots55. Work by Iacovacci et al demonstrates a method for creating soft microrobots, relying on the use of a two-step, backside exposure photolithographic process - allowing for the inclusion of a radiocompound within the robot’s structure to permit imaging56. A recent publication by Mu and team reports the preparation of MOF-based microrobots57. This method relies on the use of sacrificial photoresist platforms used to help release the robots from the substrate for further treatment after a series of metal film depositions using RF magnetron sputtering. Microrobots of different shapes could be created using photomasks having different designs.

Figure 5. Commonly used Micro-/Nanorobotic Fabrication Methods.

(A) Photolithography (reprinted from ref. 54 with permission, copyright 2022, MDPI). (B) Additive manufacturing (reprinted from ref. 65 with permission, copyright 2021, IOP Publishing). (C) Glancing angle deposition. (D) Template-guided electrodeposition (reprinted from ref. 59 with permission, copyright 2022, Elsevier B.V.).

3.2. Template-Guided Electrodeposition

Template-guided electrodeposition typically involves the use of an electric current to reduce metal cations (or conductive polymers) onto the surface of an electrode covered with a porous membrane53. This membrane is used to restrict growth to occur solely within the pores. A direct consequence of this growth restriction is that the membrane’s pore size can be modulated to create different sizes of micro-/nanorobots. The membrane can then be dissolved after deposition, releasing the robots into solution.

In their bid to create a cargo-delivering micromotor that could be propelled using magnetism as well as a chemical fuel, Li and coauthors used electrodeposition with a membrane template as their fabrication method of choice58. Their method first begins with sputtering a gold film on one side of the polycarbonate membrane to serve as a working electrode followed by deposition of an external polyaniline layer. A layer of nickel was continuously deposited in the tube as well as the internal platinum catalytic layer. The gold film could be removed by manual polishing with alumina, and the microrobots were subsequently released after dissolving the membrane in methylene chloride. A similar method was recently used by Lu et al in their publication describing the fabrication of superfast, tubular micromotors powered by ultrasonic waves (Figure 5D)59. Ji et al have recently demonstrated synthesis of swinging flexible nanomotors60. In their method, the authors use electrodeposition to synthesize the nanomotors in a part-by-part method by sequential electrodeposition of gold, silver, and nickel within an aluminium oxide membrane. The authors remark that their use of template-assisted electrodeposition allowed reproducible mass production of nanomotors.

3.3. Additive Manufacturing

There are currently five main types of additive manufacturing (also known as 3D printing) techniques used to fabricate micro-/nanomotors - those being: direct laser writing (DLW), stereolithography, microscale continuous optical printing, inkjet printing, and PolyJet61. However, the most common means of 3D printing microrobots is direct laser writing, which will be the focus of this subsection.

Direct laser writing via two-photon polymerization (TPP) involves the use of a high intensity femtosecond laser source to selectively polymerize photosensitive material in a preprogrammed three-dimensional path via a nonlinear absorption process62. Depending on the resist used, areas of the resin that were either exposed or unexposed to the laser can be removed using developer solution in a way similar to conventional photolithography63. While DLW is known to have a relatively slower fabrication speed when compared to other 3D printing technologies, it makes up for it with its superior resolution (100 nm).

Liu et al have recently used two-photon polymerization to permit construction of 3D cavities out of photoresist to serve as negative molds for fabricating complex magnetic microdevices with heterogeneous material compositions and 3D programmable magnetization profiles64. The authors claim that by repeating their exposure-molding cycle they are able to integrate multiple materials together and program the individual magnetization direction for the purpose of creating smart microdevices - ranging from magnetic micro-rotors to a micro-cilia array. Interestingly, Alsharhan and team have managed to use DLW to create soft microrobotic grippers within a microfluidic device (Figure 5B)65. The grippers could be designed in computer-aided design (CAD) software. Using the exported model, CAM (computer aided manufacturing) software could then be used to produce the path the laser will take during printing. Negative-tone photoresist was then loaded into channels in the microfluidic device, and the grippers could be printed in a serial “floor to ceiling” fashion.

3.4. Glancing Angle Deposition

Conventional physical vapor deposition (PVD) processes involve target materials being vaporized and subsequently deposited onto a stationary substrate of the researcher’s choice31. Glancing Angle Deposition (GLAD) is a more specialized PVD technique used to produce nano-scale columnar films with controlled shapes and porosities66. During GLAD, the substrate is tilted at an angle to the direction of the coating vapor flux and rotated to control the film’s characteristics and growth. By varying parameters including the angle of incidence, rate of deposition and rotation of the substrate, it is possible to change the morphology and properties of the desired film with fully three-dimensional control - making the technique very useful for nanostructure fabrication with a variety of materials possible.

Using this approach, Dasgupta et al have developed helical nanorobots which they have proposed for use in fighting bacterial infection in the tooth’s dentinal tubules67. To fabricate their nanorobots, the authors began by first placing down a seeding layer consisting of pillars made of silica. Then, GLAD was used to grow silica helices onto the seeding layer at a deposition angle of around 5° while the seeding layer was rotated. The diameter of each silica pillar in the seeding layer determined the thickness of the nanorobots, whereas the time and rotation rate of the seeding layer determined their length and pitch, respectively. To form the nanorobot’s head, material was deposited in layers using a sequential order - that being: 5 nm of silver, 50 nm of silica, 10 nm of pure iron, and 50 nm of silica without rotation of the seeding layer. Material deposition was followed by controlled rotation of the GLAD platform and deposition of silica until a total vertical deposition thickness of 3 μm was achieved. Similar methods have been reported by Ghosh and Ghosh to create helical nanostructures using polystyrene beads as a seeding layer68. Rivas and team have recently reported the use of microrobots to physically manipulate cells69. Using GLAD, micro-sized silica spheres were coated with a 100 nm nickel layer at a 70° glancing angle as a means of making them magnetic for actuation via rotating magnetic fields.

4. Applications in Sensing

In conventional surface-based sensing, roaming target analytes – in free liquid phase or gas phase – are recognized and captured by stationary probes functionalized on a solid surface70, 71. In this model, the process is mainly driven by two factors: 1) the inherent (bio)chemical reaction kinetics between target and probe – including electrochemical transduction, enzyme-based reaction and affinity-based recognition72 – which is the chemical limit of the surface assay; 2) the transport efficiency of the target analyte onto the reactive surface – determined by liquid topography and fluid dynamics, including diffusion, convection – which is the physical limit of the surface assay73. In the case of a steady-state liquid, mass transport is fueled by passive Brownian diffusion, or molecular random walk. In the case of flow-through platform (particularly microfluidics) mass transport (as well as heat transfer) can be improved compared to the diffusion-limited process, but laminar flow becomes dominant, leading to the formation of a diffusion boundary layer and limited radial convective flux and mixing74–76. The mass transport limitation, being increasingly significant at ultralow concentrations, affects the overall sensing performance, including sensitivity, robustness, and response time. In this regard, enhancing the dynamic flux as a means of breaking the bottleneck of mass transport is always appealing to physicists and chemists. Numerous efforts in vastly diverse approaches have been proposed to improve the reaction efficiency and overcome the relevant issues in fluids, such as external advection71, 77, active depletion of boundary layer78, generation of convective flow by electro-thermophoresis79, herringbone microstructure80–83, isotachophoresis84, 85, acoustics induced mixing86–88 and tuning of probe immobilization89. However, in these works, sophisticated engineering of the interface or introduction of advanced molecular mechanism90, 91 are inevitable, restricting the potential mass production as well as out-of-lab implementations.

As mobile platforms of “chemistry-on-the-fly”, micro-/nanorobots offer fundamentally revolutionary solutions for surface-based sensing3, 92. On one hand, the motion of micro-/nanorobots – including speed and trajectory – is sensitive to many parameters in the surroundings, thus, the motion can be directly used to reflect the changes in these physical or chemical signals; on the other hand, when functionalized with various probes, the active motions of micro-/nanorobots turn them into “active hunters” that feature enhanced target recognition, enrichment, and detection. Simultaneously, in-liquid mass transport (whether in microfluidics or large liquid reservoirs) can be accelerated due to motion-induced fluid convection and mixing93, which helps to push the limit in the interfacial recognition events between probes and analytes. In all, micro-/nanorobots can help to break the physical limitations in the previously discussed surface-based sensing platforms, leading to shortened response time and enhanced sensitivity3, 7. Other unique properties, including minimized size, large surface area, versatile and enduring functionalization availability, help them to flourish. In this regard, micro-/nanorobots has been adopted in the sensing and detection of a wide variety of analytes, including cells, bacteria, proteins, nucleic acid, biomolecules, inorganic ions, etc. As an unconventional approach, this section will be introducing these applications based on their different strategies.

4.1. Strategies

4.1.1. Motion-based Sensing

Having controlled, autonomous motion is one of the most critical parts in the design of micro-/nanorobots. Given that the motion in aqueous environment can be dependent on multiple factors (e.g., concentration of chemical species), any changes in these factors will directly lead to the changes in the motion3, which makes motion-based sensing the earliest developed and the most extensively studied. In 2009, Wang et al proposed a catalytic Au-Pt nanowire for the chemical detection of trace level silver94 (Figure 6A). In this pioneering work, the existence of Ag+ will remarkably induce an increase in the average speed of the nanowire, as the silver ions would be absorbed onto the nanowire surface with the presence of hydrogen peroxide. The reduced silver could help to accelerate the electrocatalytic decomposition of the hydrogen peroxide fuel, leading to observably faster motion of the nanowire. Besides Ag+, other heavy metal ions also have significant effect on the catalytic activities that are responsible for the motion of micro-/nanorobots, which led to following studies that used this mechanism to detect water-polluting metal ions such as lead95 and mercury96, 97. For example, Hg2+ could be absorbed onto the Pt surface, which dramatically decrease the moving speed of the nanomotor, and the detection of Hg2+ reached very low LOD in the allowable range in drinking water97. Furthermore, using pH-responsive gelatin material, the catalytic activity can also be engineered to be responsive to the pH of the circumstance, enabling the motion-based pH sensing application98.

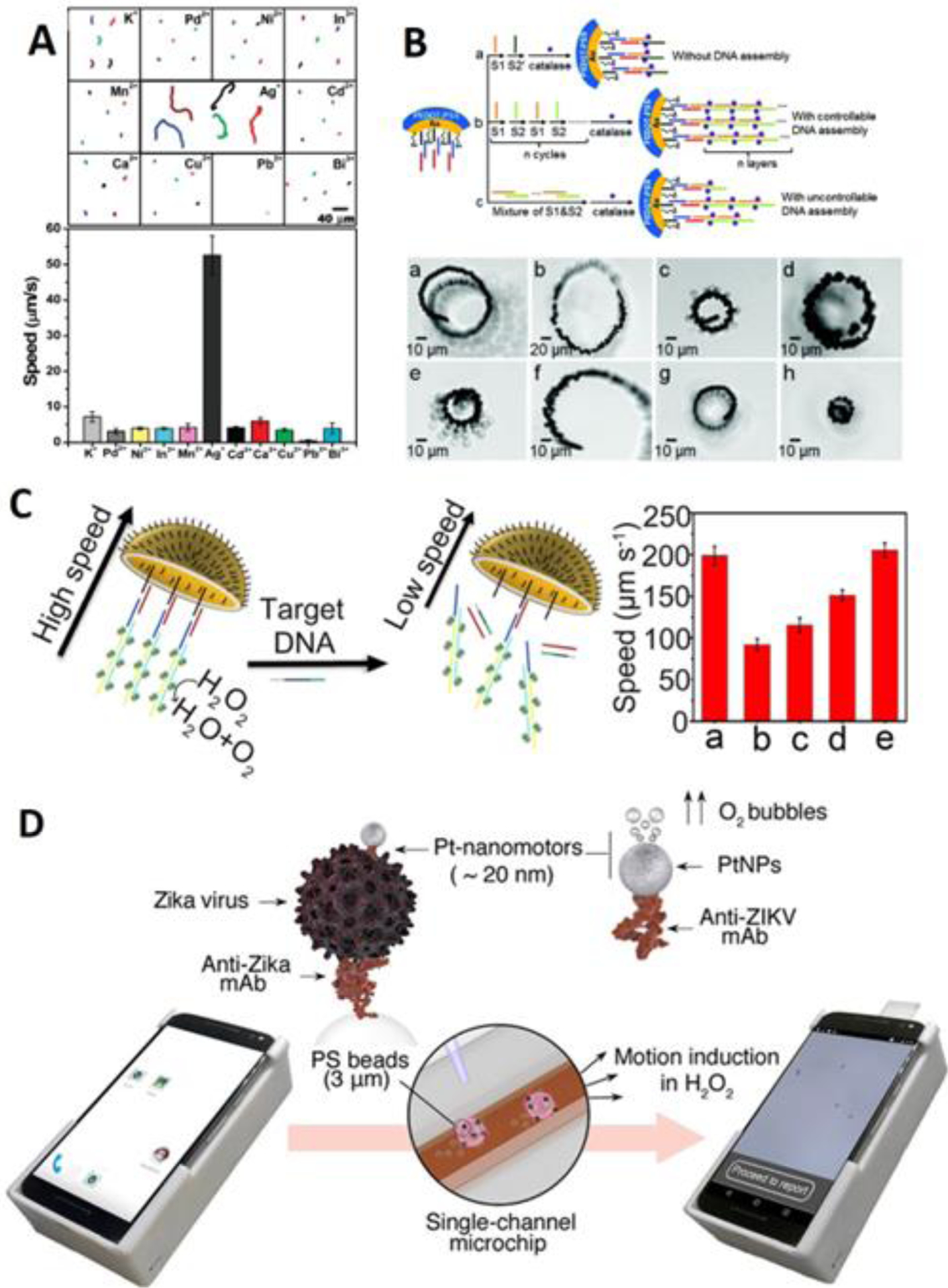

Figure 6. Motion-based sensing.

(A) Motion-based sensing of trace level silver. The reduced silver could accelerate the motion of the nanowire, scale bar: 40 m (reprinted from ref. 94 with permission, copyright 2009, American Chemical Society). (B) Motion-based sensing of DNA improved by cyclic alternate hybridization. The subset of photo from (a) to (h) shows the time-lapse images of micromotors in response to 0, 10, 30, 50, 100, 300, 500 and 1000 nM DNA in 0.2 s, scale bar: 10 m (reprinted from ref. 102 with permission, copyright 2017, American Chemical Society). (C) Motion-based sensing by jellyfish-like micromotor. The plot shows the average speed of micromotor in (a) background, (b) 5 M target DNA, (c) 50 M 1 bp mismatch DNA, (d) 50 M 3 bp mismatch DNA, (d) noncomplementary DNA (reprinted from ref. 103 with permission, copyright 2019, American Chemical Society). (D) Motion-based sensing of Zika virus using smartphone as readout. The screenshots show the motion tracking application interface and data processing (reprinted from ref. 117 with permission, copyright 2018, American Chemical Society).

Following the work of Ag+ sensing, using the same mechanism, motion-based strategy has been developed for the sensing of DNA99. Herein, after the capture of the target strand, a detector probe, which was functionalized with Ag nanoparticle, was added to hybridize with the target strand. Therefore, the amount of Ag nanoparticle was in proportion with the amount of target strand. Transferring into H2O2 solution, the speed (or the moving distance of a straight line) of the nanomotor can be readily used to determine the DNA or RNA as low as 2,000 copies per L. However, the system’s application in “real-life” samples was quite limited due to the inactivation of high ionic strength100. Similarly, a microtube was fabricated, where the inner Au surface was functionalized with DNA strands101. To facilitate detection, the Pt nanoparticle, which was also functionalized with DNA strands, would be conjugated onto the Au surface at the presence of the target DNA. Again, the conjugated Pt could catalyze the decomposition of H2O2, resulting in a “signal-on” motion-based DNA sensor. However, the sensitivity of this microtube was low (LOD = 0.5 M), possibly due to the poor catalytic capability of Pt. To increase the sensitivity, the Ju group employed cyclic alternate hybridization assembly of multiple catalytic units, which improved the motion102 (Figure 6B). The catalase was attached with 2 partly complementary DNA strands (S1 and S2) that can alternately hybridize with each other. Since each strand was attached with a catalase unit, a multilayer catalase structure can be controllably immobilized on the inner surface of the microtube (i.e., S1/S2…S1/S2), which can efficiently empower the motion of the microtube. In this study, the speed in 2% H2O2 solution (~420 m/s) was much faster than the last case101 (210 m/s in 5% H2O2), and brought about a detection limit that was 50 times lower. Recently, the same group has also developed a jellyfish-like micromotor103 – an umbrella-shaped structure with increased sensing surface – that featured easy fabrication and sensitive detection of DNA (Figure 6C).

Some other analytes in motion-based sensing include protein104, glucose105 and toxins106, 107, but these are less representative in motion-based sensing due to the more complicated recognition (e.g., enzyme based reactions) and propulsion process (e.g., Marangoni effect). Interestingly, motion-based sensing was also applied for the evaluation of liquid viscosity or mechanical properties of cells108, 109. For example, Ambarish Ghosh et al internalized helical magnetic nanomotors into cells, performed precise locomotion of the nanomotor, and found that the motion is strongly sensitive to the local mechanical properties of the intracellular environment110. While there are many cases that used magnetic tweezers or magnetic wires for the measurement of intracellular environment111–113, micro/-nanorobots can provide better maneuverability. Later, this group used a helical magnetic nanomotor as the probe to measure the mechanical properties of cytoplasm and found significant difference between normal cell and HeLa cells114. Lin Wang et al applied motion-based sensing for liquid viscosity115, where the measurement of 1.5–7.486 cP viscosity was conducted by a bubble propelled micromotor. An inevitable problem in motion-based sensing strategy is the accurate interpretation of the distance or the speed: it can be imprecise using naked eye or labor-intensive using microscopes, which is improper for commercial use. To address this, several studies have proposed using a smartphone platform as a readout. For example, Shafiee et al developed DNA engineered micromotors for motion-based detection of HIV116 and Zika virus117 (Figure 6D) using a cellphone. Escarpa et al also proposed a Janus micromotor for the motion-based detection of glutathione using a smartphone118, and proved that the analytical characteristics are very comparable to results obtained using an optical microscope.

4.1.2. Optical Sensing

Optical sensing is a powerful tool and comprises an extremely important category of sensing based on micro-/nanorobots119. As aforementioned, micro-/nanorobots can be easily functionalized with various optical probes, and these mobile platforms offer great advantages over static platforms to perform “sensor-on-the-fly”3, 92. Here, optical sensing can be discussed in the following categories:

4.1.2.1. Fluorescence

Fluorescence detection is sensitive, cost-effective, and straightforward, making it simple to be coupled with micro-/nanorobotics119. Fluorescence detection can be conducted via 2 modes: “on-off” detection, where the analyte quenches the fluorescence previously labelled on the micro-/nanorobot, and “off-on” mode, where the analyte “turns on” the fluorescence signal via some specific molecular mechanism.

“On-off” mode.

The Wang group first incorporated quantum dots (CdTe) onto the outer surface of a tubular micromotor, which employed binding-induced quenching to monitor Hg2+ in real time120. The response time is very short (12s for 3 mg/L Hg2+); however, the sensitivity is not very high (LOD 0.1 mg/L). In another study, a Janus micromotor was coated with dye that allowed instantaneous determination of sarin and soman simulants121. Here, the fluorescence of the moving micromotors was completely quenched by sarin and soman simulants while the fluorescence of the static micromotors barely changed, which demonstrated the increased rate of collision between the moving micromotor and analytes. The Pumera group fabricated a photoactivated tubular micromotor using C3N4, which was used for optical monitoring of heavy metal and concomitant removal122 (Figure 7A). This material possesses inherent fluorescence, eliminating the need to label with fluorescence dyes. After the adsorption of heavy metal ions, the auto fluorescence could be greatly quenched due to the transfer of a photogenerated electron, enabling the rapid sensing of Cu2+. Yang et al fabricated a tubular micromotor where the Eu-based MOF material was used for the sensing layer123 (Figure 7B). The fluorescence emission of the micromotor can be completely quenched by Fe3+, leading to a detection limit of as low as 0.15 M, which is lower than LODs achieved in other similar works. Similar techniques have been applied in many other research areas, including the sensing of mycotoxin in food samples124, enterobacterial contamination125, nitro explosives126 and gas molecules127.

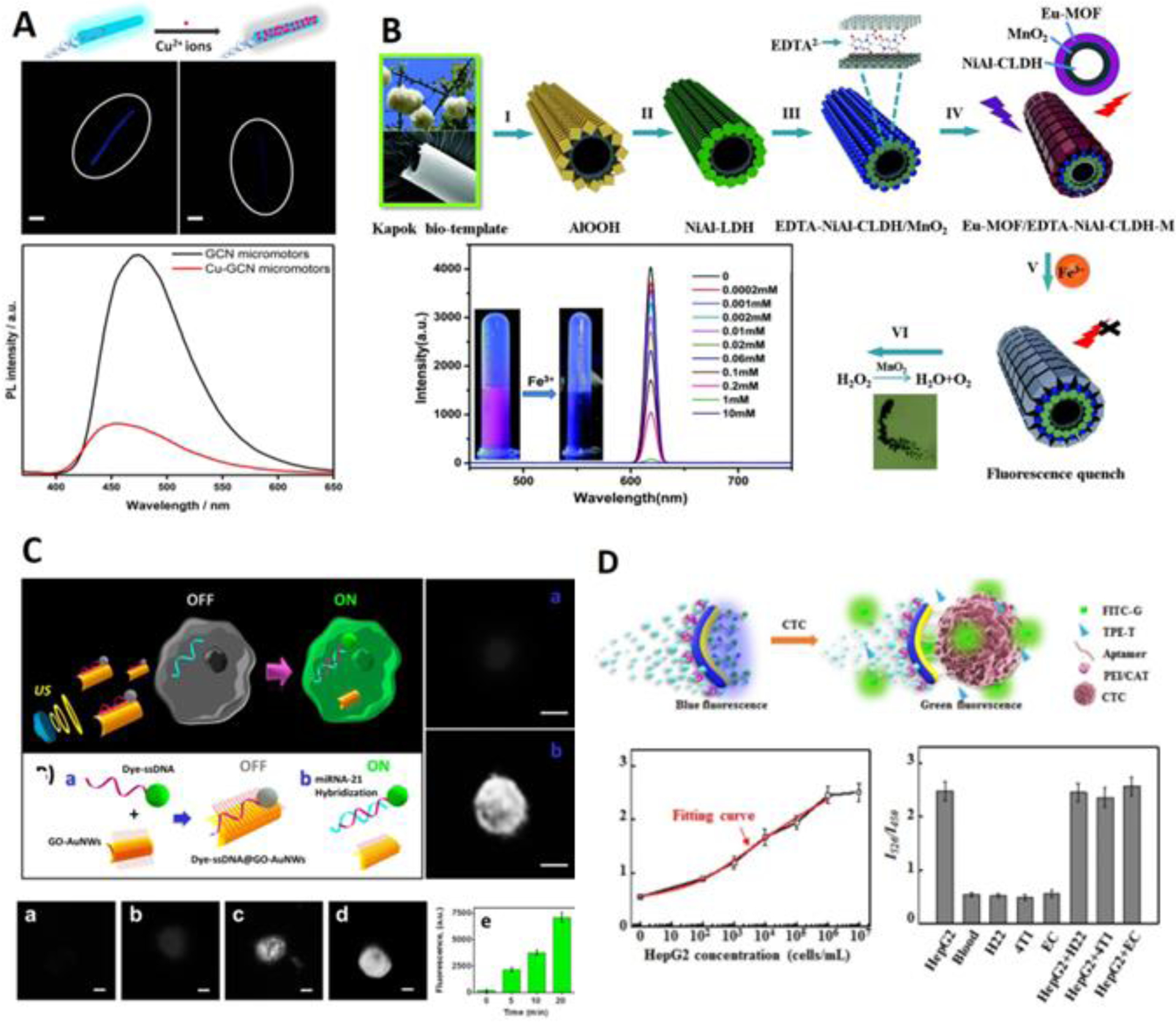

Figure 7. Fluorescence Sensing Based on Micro-/Nanorobotics.

(A) “On-off” fluorescence sensing by copper ion quenching of fluorescence on micromotor, time-lapse images of fluorescence intensity (7 min) (scale bar: 10 m), and photoluminescence overlapped spectra of micromotor at excitation of 350 nm (reprinted from ref. 122 with permission, copyright 2018, American Chemical Society). (B) Bio-template fabrication of micromotor and the sensing and removal of Fe3+. The inset shows the fluorescence intensity in response to different concentrations of Fe3+(reprinted from ref. 123 with permission, copyright 2019, The Royal Society of Chemistry). (C) “Off-on” fluorescence sensing of miRNA by nanomotor in cell. (a) to (d) fluorescence images of MCF-7 cells after incubation with nanomotor for 0, 5, 10 and 20 min, scale bar: 10 m. (e) dependence of fluorescence signal upon ultrasound exposure time (reprinted from ref. 128 with permission, copyright 2015, American Chemical Society). (D) Ratiometric fluorescence detection of CTC by Janus micromotor. The insets show the ratio of with different concentrations of HepG2 cells (n=3) and the ratio in response to different cells (reprinted from ref. 134 with permission, copyright 2020, Elsevier B.V.).

“Off-on” mode.

On the other hand, the “off-on” detection methodology offers more intuitive analytical results - even though the transduction process is more complicated as it usually involves the spatial separation of fluorescent dye and quenchers. The Wang group devised a gold nanowire carrying dye-labelled single-stranded DNA and graphene oxide (GO)128 (Figure 7C). Using ultrasound propulsion, the nanomotor can be internalized into cells easily and safely. The fluorescence of the dye, which was initially quenched by GO due to the stacking interaction, can be “turned on” when the single strand DNA was hybridized with target miRNA-21 and separated from GO, leading to sensitive miRNA detection in a single cell. Compared to static condition, the hybridization efficiency was observed to be improved due to the nanomotor movement and was directly related to the applied ultrasound and nanomotor speed. A very similar work by this group used a reduced GO/Pt tubular micromotor to carry dye-labeled ricin B aptamer, which enabled real time “off-on” fluorescent detection of ricin B129. MoS2 also has a delocalized electron network that can facilitate the stacking interaction and has therefore been used to fabricate tubular micromotor with multiple capabilities, including “off-on” fluorescent detection of miRNA-21 and thrombin130. WS2 can also quench the fluorescence (e.g., from rhodamine) via electrostatic and hydrophobic interactions, which was applied in a Janus micromotor for the “off-on” detection of bacterial lipopolysaccharides131. Additionally, the WS2 micromotor had a rougher surface morphology than the MoS2 micromotor, which allowed increased probe loading and better sensing performances132. However, in these works, the fluorescence signal was “turned on” by separating the dye from the quencher, which means the fluorescence signal was not concentrated on the micro-/nanorobot but rather dispersed in the aqueous solution. This will impose possible difficulties in the observation of the fluorescence signal and in real applications. To focus the fluorescence signal on micro-/nanorobots, other mechanisms have been introduced. The Li group grafted mannose on a Janus micromotor, which can instantaneously capture E. coli due to the recognition of FimH proteins133. Meanwhile, the specific binding will initiate aggregation-induced-emission (AIE) effect of tetraphenylethene (TPE) derivatives, so the fluorescent Janus micromotor can be “turned on”. The same group also applied TPE-T (thymine conjugated on tetraphenylethene) and FITC-G (guanine conjugated on fluorescein isothiocyanate) on a Janus micromotor134 (Figure 7D). The binding between the fluorophores and aptamer induces aggregation-caused-quenching (ACQ) effect on FITC and aggregation-induced-emission effect on TPE, where only blue fluorescence was observed. When circulating tumor cells are captured by the micromotor, the blue fluorescence of TPE would be reduced while the green fluorescence of FITC would be restored. Therefore, the ratio between the blue fluorescence and green fluorescence can reflect the amount of CTC, resulting in an interesting “ratiometric” fluorescence detection. Fei Peng and group have functionalized a magnetically driven helical hydrogel micromotor using a monomeric cyanine dye, SYBR Green I, which emits fluorescence upon combining with double-stranded DNA, allowing the fluorescence signal to be observed on the body of the micromotor135. Some signal amplification strategy could be introduced, for example, an entropy-driven signal amplification method was used for the detection of miRNA, where the paired target strand would be replaced by a fuel DNA, so the target strand can enter the next round of displacement reaction, achieving the effect of cascade amplification136. Reasonably, a smartphone was also introduced for the accurate and convenient readout of the fluorescence detection137.

4.1.2.2. Colorimetric Sensing

Colorimetric sensing is widely applied in many detection methods, including immunoassays70. The Wang group presented the first antibody-functionalized micromotor for capturing and transporting protein between reservoirs in microfluidics138. Here, the multistep immunoassay was conducted by magnetically directing the micromotor to separate reservoirs for different events (i.e., capturing of antigen or binding of secondary antibody), simplifying the total process of immunoassay. However, colorimetric analysis wasn’t applied in this case. Shortly after, Merkoçi group applied micromotors in a microarray immunoassay and proved that the mass transport was improved by the mixing effect from the micromotor, which resulted in a relative increase in signal intensity of up to 3.5-fold139. However, the antibody was functionalized on the microarray slides, and the micromotor only functioned as an additional mixer. Ju’s group used an antibody-functionalized micromotor to capture cancer biomarkers (AFP and CEA)140. The authors used glycidyl methacrylate (GMA) microspheres modified secondary antibody to specifically recognize the captured biomarker, so the target concentration can be visualized by tag counting or motion speed of the micromotor in only 5 minutes. In another work that used the microscale tags141, a multiplexed immunoassay of different model proteins was achieved by a micromotor functionalized with different capturing antibodies. In 2017, the Wang group performed ELISA of cortisol on micromotors142 (Figure 8A). It was demonstrated that the signal intensity from the moving micromotor in 30s was 3-fold higher than that from a static micromotor in 1 minute. Using antibody-attached HRP to catalyze TMB/H2O2, rapid, naked-eye detection was accomplished, and here, H2O2 was used as both the fuel of the micromotor and the visualizing reagent of the detection. Yong Wang et al presented magnetic nanobots as maneuverable immunoassay probes143. Instead of self-propulsion, this work utilized magnetic field-induced spinning of the magnetic rod to improve the mixing efficiency, and the resulting fluid flow had been well simulated. Furthermore, they developed a Helmholtz coil for automated and high-throughput analysis of samples in 4 96-well plates. Together with an impressive limit of detection (0.18 ng/mL) and short assay time (< 1 h), this work demonstrated the great potential in applying micro-/nanorobots towards immunoassays. Other types of immunoassays, including fluorescence immunoassay144, electrochemical immunoassay145 motion-based immunoassay117 were also applied on micro-/nanorobots. Despite immunoassays, colorimetric sensing was also applied to the sensing of glucose146 or phenylenediamines147, based on micro- or nanomotors.

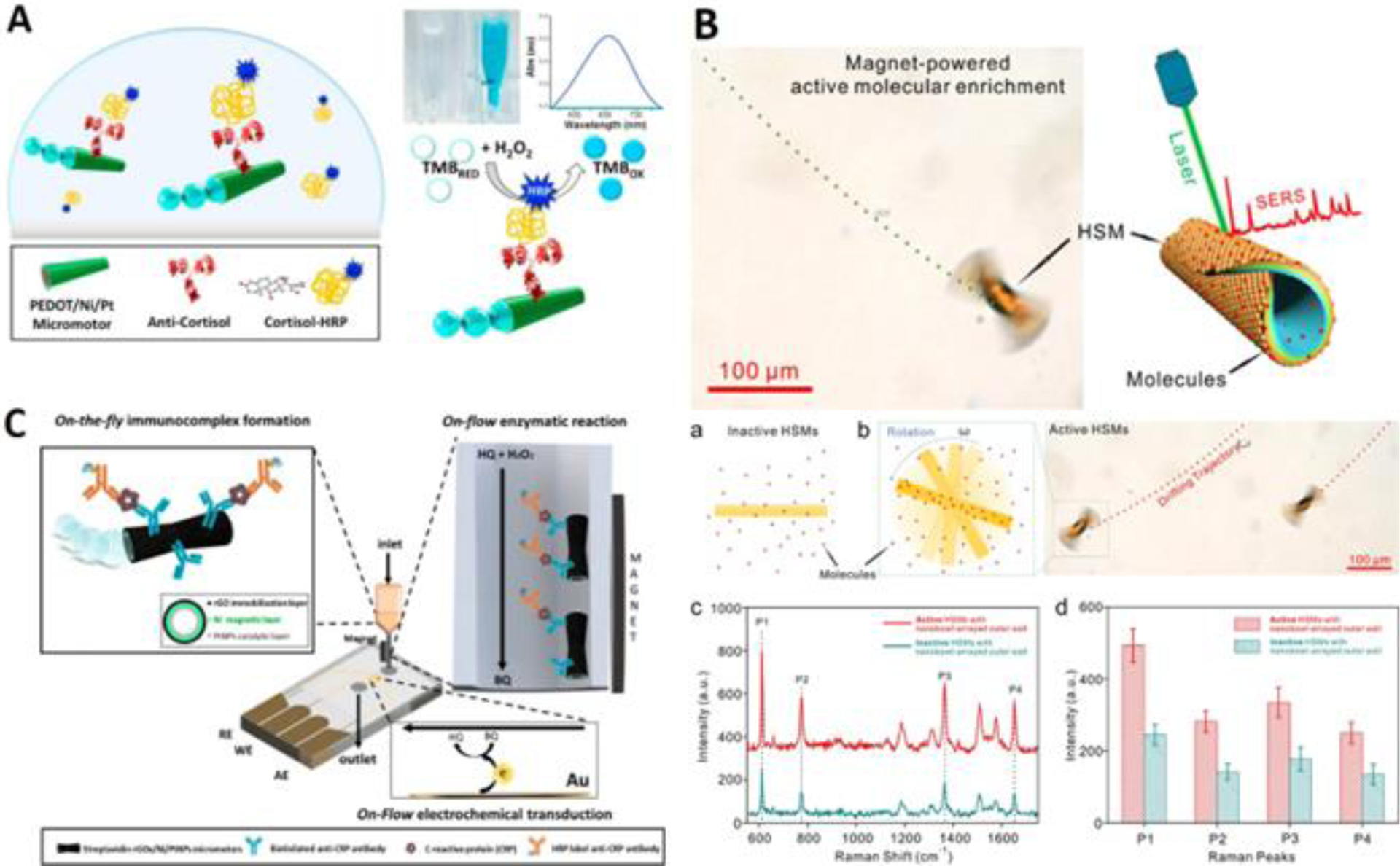

Figure 8. Colorimetric Sensing Based on Micro-/Nanorobotics.

(A) Naked-eye immunoassay of dynamic cortisol by micromotor functionalized with anti-cortisol antibody (reprinted from ref. 142 with permission, copyright 2017, Elsevier B.V.). (B) Ultrasensitive SERS detection by hotspots engineering on micromotor, scale bar: 100 m. (a), (b) illustrate the active molecular enrichment by magnet-powered rotation. (c) SERS spectra acquired from passive and active molecular enrichment. (d) SERS intensity of R6G characteristic Raman peak from (c) (reprinted from ref. 152 with permission, copyright 2020, American Chemical Society). (C) Illustration showing the electrochemical microfluidic chip for micromotor-based immunoassay of CRP. CRP was first immune-captured by antibody-functionalized micromotor, and then the micromotors were transferred to an electrode for electrochemical transduction (reprinted from ref. 145 with permission, copyright 2020, American Chemical Society).

4.1.2.3. Surface-enhanced Raman Spectroscopy

Surface enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SERS) is one of the most sensitive techniques in chemical and biological sensing148, where the signal intensity is amplified by the enhanced electromagnetic field generated from localized surface plasmons. Di Han et al developed a catalytic tubular micromotor to capture Rhodamine 6G along with SERS sensing149. The outer layer of the micromotor is gold, which can absorb R6G by electrostatic force and can be used as an excellent SERS substrate. Here, the signal from the moving micromotor was 5 times higher than that from a traditional static setup due to more molecules being collected by the moving micromotor. Yong Wang et al fabricated a matchlike nanomotor with a AgCl tail150. Upon UV irradiation, AgCl would be decomposed and produce H+ and Cl−. This would generate an electric field pointing towards the head of the structure, leading to light-triggered self-diffusiophoresis of the nanomotor. The body of the nanomotor was silica-coated Ag, and due to the encapsulation of the inert silica shell, shell-isolated enhanced Raman spectroscopy (SHIERS) sensing of crystal violet and MCF-7 cells was achieved. The signal compared with that from the static condition was 6.2 times higher. The Pumera group fabricated a nanomotor with simple Ag/Au core shell151, enabling real-time, sensitive detection of picric acid with detection limit of 10−7 M. Hotspot engineering – an efficient method to fabricate high-performance SERS substrates – was also applied on a magnetic micromotor152 (Figure 8B). Benefitting from both hotspot engineering and the rotation-caused active molecular enrichment, ultrasensitive sensing of R6G (detection limit 5 10−10 M) was demonstrated. Xiaojia Liu et al grafted a thermoresponsive polymer (PNIPAM) on the outer surface of hollow mesoporous silica nanoparticles153, forming a controllable “gate” for the in situ sampling. Gold nanodots were encapsulated within the nanoparticle as SERS sensing probe. When the “gate” was opened, analytes would be introduced into the hollow nanoparticles for subsequent SERS sensing.

4.1.3. Electrochemical Sensing

Electrochemical sensing is a sensitive method that is widely used, especially for analytes that can undergo redox reactions154. Reasonably, it has also seen application in sensing based on micro-/nanorobotics. In some studies, micro-/nanorobots were only used as a controllable mixer of the existing liquid-based sensing scheme. For example, the Wang group used Janus micromotors on printable sensor strips to induce mixing and improve the mass transport in the amperometric detection of nerve agent155, where the sensitivity was increased 15 times. Rojas et al used Janus micromotor in the electrochemical analysis of diphenyl phthalate (DPP) in complicated matrices156, increasing the sensitivity over around 20-fold. Lei Kong et al utilized Janus micromotors in the electrochemical detection of glucose and improved the sensitivity with respect to the concentration of micromotors introduced157.

In other studies, micro-/nanorobots were used as mobile platforms to capture analytes for subsequent electric readout. The Pumera group published work that developed the remote monitoring of micromotors using a voltametric method158, 159 and a chronoamperometric method160, which could be possibly used for electric readout of motion-based sensing. Escarpa et al functionalized a magnetic micromotor with antibodies to immunologically capture C-reactive protein in very low sample volumes and then collect the micromotors onto electrodes for sensitive amperometric readout145 (Figure 8C). Chun Mao et al proposed a Mg-based magnetic Janus micromotor for miRNA and protein detection161. Here, the micromotor was actuated by the reaction of Mg and water to generate H2 and Mg2+. The micromotor was functionalized by the trapping agent with Mg2+-induced nuclei acid fragment, when Mg2+ ions were generated, this fragment would be cut to release the target and fragments in cycles to realize signal amplification. Finally, a funnel-type electrochemical detection device was used to ensure full recovery of the recognizing agents.

4.2. Sensing-based Applications

Even though this section is primarily focused on the sensing application of micro-/nanorobotics, other interesting applications – based on and beyond sensing – are also necessary to be included and discussed here to provide a comprehensive overview and prospect. Being mobile platforms for “chemistry-on-the-fly”, the advantages in minimized sizes, large surface area, and tunable functionalization availability make micro-/nanorobotics superior in these cutting-edge applications.

4.2.1. Target Isolation, Transport, and Delivery

Resulting from controlled motion, micro-/nanorobots can be further used for isolation, transport, or delivery after recognition of target analytes, which is the most extensively studied application162. The Wang group have developed a series of micromotors functionalized with specific receptors for the isolation of bacteria163, protein164, nucleic acids165, and cancer cells166. Other than receptors, molecularly imprinted polymers (MIPs) were also used for target recognition and transport167, 168. They also fabricated a helical nanomotor coated with a layer of natural platelet membrane, which had anti-fouling capability in biological environment and was used to capture and transport platelet-specific toxins and pathogens169. Another similar work was the coating of a hybrid membrane on an acoustically-actuated nanomotor for recognition and detoxification of different biocontaminants170.

More important is the ability of micro-/nanorobots to controllably deliver target (e.g., genes, drugs, imaging agents) into tissues or cells. Nelson et al functionalized magnetic helical micromotor with lipoplexes, which could be loaded with plasmid DNA. The micromotor was steered wirelessly to come into contact with cells and could easily fuse or incorporate into cells, allowing the transport of DNA as gene therapy agents171. Peer Fischer et al fabricated a nontoxic and biocompatible nanomotor with a helical silica body and ferromagnetic FePt tail and functionalized it with polyethyleneimine172. This allowed the nanomotor to carry plasmid DNA and transfect target cells. Renfeng Dong et al used an ultrasonically-propelled gold nanomotor to deliver model antigen (ovalbumin) into cells to trigger an immune response173. Previously, the acquired response was limited since the internalized exogenous antigens are mostly degraded by lysosome. However, in this case, the controlled nanomotor could be controlled to escape capture via lysosome, which improved the expression level of antibody. The Wang group also used RBC-PFC (red blood cell membrane-coated perfluorocarbon nanoemulsion) to coat acoustically-driven gold nanomotors for active intracellular oxygen delivery, which found application in maintaining the viability of cells174 (Figure 9A). The oxygen release rate could also be tuned by ultrasound intensity, and this model could be used for the delivery of other therapeutic gas molecules.

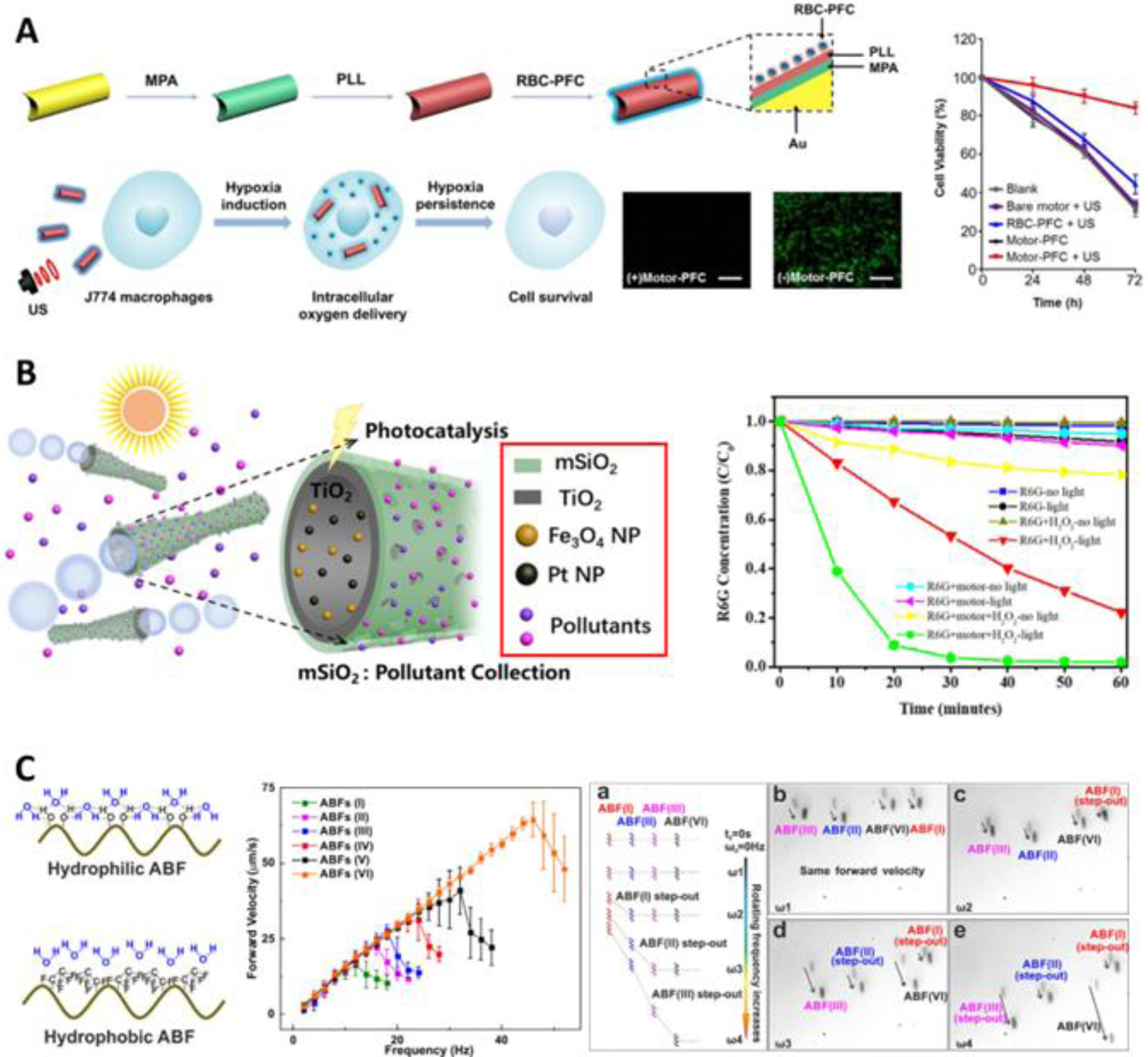

Figure 9. Sensing-based Applications.

(A) Active intracellular oxygen transport by nanomotor. The green fluorescence in the microscope images indicated the intracellular hypoxia stress, indicating that cells treated by the nanomotor maintain low hypoxia stress. Scale bar: 100 m. The plot shows viability of J774 cells incubated with different concentrations of nanomotor and then subjected to hypoxia (reprinted from ref. 174 with permission, copyright 2019, American Chemical Society). (B) Bilayer tubular micromotor for contaminant monitoring and remediation. The outer layer of mesoporous SiO2 was used for adsorption, and the inner layer of photocatalytic TiO2 was used for contaminant degradation. The plot shows the degradation of R6G under different conditions (reprinted from ref. 187 with permission, copyright 2018, American Chemical Society). (C) Selective manipulation of helical micromotors with different surface hydrophobicity in a swarm. The plot shows the relationship between forward velocity and the rotating frequency of the applied magnetic field for different micromotors. (a) illustrates the selective control of different micromotors, (b) to (e) screenshots of movement of 4 different micromotors in specific magnetic fields (reprinted from ref. 202 with permission, copyright 2018, American Chemical Society).

Due to the ability to penetrate deep tissues and complex structures, researchers have also functionalized micro-/nanorobots with imaging agents for applications in medical imaging162, 175. For example, Xiaoyuan Chen et al fabricated a helical magnetic microswimmer coated with polydopamine (PDA)176. The PDA coating enhanced the photoacoustic signal and photothermal effect, and meanwhile, it also had an innate fluorescence quenching property that led to diagnosis with fluorescence probes. Combined, the microswimmer had real-time photoacoustic image tracking and theragnostic capabilities for the treatment of pathogenic bacterial infection. Li Zhang et al proposed a biohybrid magnetic microrobot based on microalgae177, which had desirable functional attributes from two elements: on one hand, the inherent property of microalgae led to in vivo fluorescence imaging and remote sensing; on the other hand, the coated magnetite (Fe3O4) allowed for precise motion control as well as deep in vivo magnetic resonance imaging where fluorescence imaging is not possible. This biohybrid magnetic microrobot could therefore be used in imaging-guided therapies. Further, intelligent self-guided micro-/nanorobots that can respond to different taxis are being developed178, and they are specifically appealing in applications involving tumor tissues that can establish chemical taxis in their surroundings. The targeting process includes carrier penetration through various biological barriers, such as blood-brain barrier, gastric mucosal barrier and cell membrane barrier2. Using a biohybrid microrobot, Schuerle et al developed a magnetic bacteria-based micromotor179. Using Magnetospirillum magneticum strain as a model organism, the microrobot can undergo magnetic torque-driven motion followed by spontaneous taxis-based navigation, which can improve the infiltration through tissue barrier to deliver liposomes. Here, the rotating magnetic field showed several advantages over a conventional directional magnetic field - including moderate strength at clinical scales, better motion control, improved translocation, increased extravasation of liposome conjugate and enhanced intratumoral transport. The Gao group developed a photoacoustic computed tomography (PACT) microrobotic system, where micromotors were first enveloped in a microcapsule180. Due to the protection of the microcapsule, it can withstand the erosion of the stomach fluid, and the motion in vivo can be visualized using PACT. The release of the drug-loaded micromotors can be triggered by near-infrared irradiation, making this system dually capable of imaging and controlled delivery of drugs.

To conclude, micro-/nanorobotics offer multiple advantages compared to conventional methods and platforms in targeted isolation, transport, and delivery, and some of these aspects are still not fully discovered. In the next few years, more significant applications can be expected to fundamentally promote the development of precision medicines108.

4.2.2. Pollutant Removal