Abstract

Background:

The optimal time to initiate adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) following resection remains undefined. Herein, we investigated the impact of time to adjuvant ICI on survival in patients with stage III melanoma.

Methods:

Patients with resected stage III melanoma receiving adjuvant immune therapy were identified within a multi-institutional retrospective cohort. Patients were stratified by time to adjuvant ICI: within 6 weeks, 6–12 weeks, and greater than 12 weeks from surgery. Recurrence free survival (RFS) was compared among time strata with Kaplan Meier and Cox proportional hazards methods in the multi-institutional cohort.

Results:

Altogether, 626 patients were identified within the multi-institutional cohort: 39% of patients initiated adjuvant ICI within 6 weeks, 42.2% within 6–12 weeks, and 18.8% greater than 12 weeks from surgery. In a multivariable Cox model, adjusting for histology, nodal tumor burden, and pathologic stage, we found that increased time to adjuvant ICI was associated with improved RFS. Patients who initiated adjuvant ICI within 6 weeks of surgery had worse RFS. These findings were preserved in a conditional landmark analysis and separate subgroups of patients with 1) new melanoma diagnoses, 2) occult stage III disease, and 3) those receiving anti-PD-1 monotherapy.

Conclusions:

Outcomes for patients with stage III melanoma are not compromised when adjuvant ICI are initiated beyond 6 weeks from resection. Additional work is needed to better understand the underlying mechanisms and implications of timing of adjuvant ICI on long-term outcomes.

Introduction

Melanoma remains the most lethal form of skin cancer.1 While many patients presenting with localized melanoma will be cured with surgery alone, those with nodal involvement or the presence of satellite and in transit lesions are at high-risk for recurrence despite optimal oncologic resection.2 Historically, there were limited adjuvant therapies to mitigate the risk of recurrence in this population. However, the introduction of effective systemic therapies within the last decade, specifically immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) and targeted therapies (TT), have revolutionized the management and outcomes of high-risk resected melanoma.3–5 Accordingly, trials have demonstrated benefit in recurrence-free survival (RFS) with the use of both ICI and TT in the adjuvant setting.6–8 The FDA has approved ipilimumab, nivolumab, pembrolizumab, and combination dabrafenib/trametinib in the adjuvant setting and National Comprehensive Cancer Network (NCCN) guidelines currently recommend adjuvant therapy for those with clinically detected nodal disease, microscopic node positive disease >1mm or those with stage IIIB/C disease, as well as those with recurrent stage III/IV disease.9 Most recently, adjuvant pembrolizumab was FDA approved for patients with IIB/C melanoma and a negative sentinel lymph node (SLN) on results from KEYNOTE-716.10

Investigations into the timing of ICI have become increasingly important and the optimal interval from surgery to initiate adjuvant ICI has not been well described. Existing literature for traditional adjuvant therapies, such as those for colorectal cancer, recommend adjuvant chemotherapy 6–8 weeks following surgery.11–13 In other malignancies, studies have shown mixed relationships between timing of adjuvant chemotherapy with recurrence and survival.14, 15 For stage II/III melanoma patients, where adjuvant ICI is a relatively recent addition to management, no such recommendations exist.9 Given that surgery can generate a host immune reaction and the mechanism of ICI is to generate an immune response, the timing of adjuvant ICI for melanoma is of particular interest.16 Adjuvant clinical trials specified randomization within 12 weeks of oncologic resection; however, there is a paucity of data on the optimal time to initiate adjuvant ICI for melanoma. Therefore, we aimed to evaluate the impact of timing of adjuvant immune therapy on patterns of recurrence within a multi-institutional cohort and on overall survival (OS) within a national cancer registry.

Methods

Multi-Institutional Cohort and Patient Selection

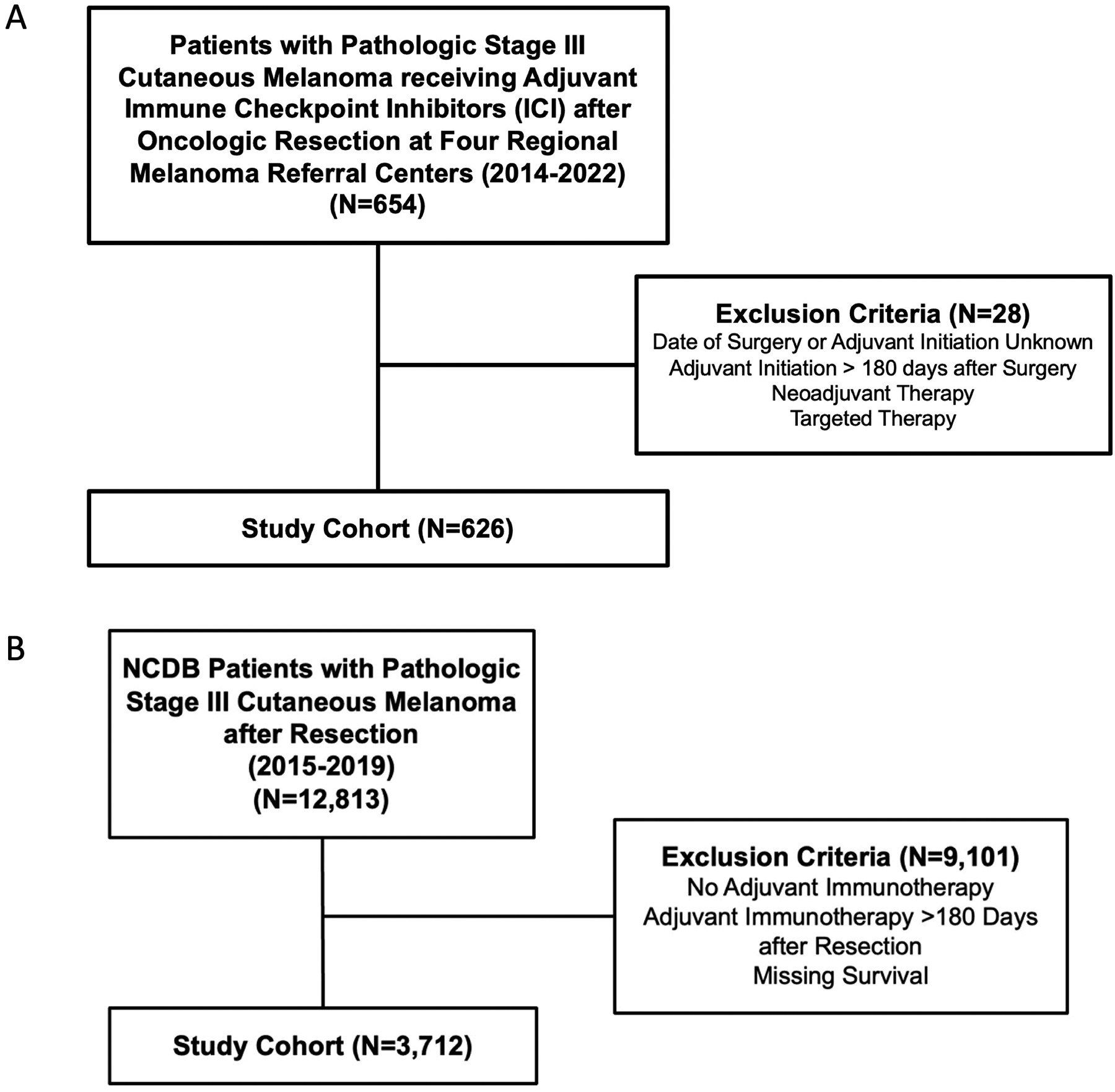

A multi-institutional retrospective cohort study was conducted amongst four regional melanoma referral centers. Institutional databases were queried for all patients with pathologic stage III melanoma diagnosed in 2014 or later, who received adjuvant ICI following oncologic resection (Figure 1A). Patients who initiated adjuvant ICI greater than 180 days from surgery, had missing date of surgery, missing date of initiation of adjuvant ICI, or missing survival were excluded. Patients who received neoadjuvant therapy (ICI or TT) or adjuvant TT were also excluded.

Figure 1.

STROBE Patient Selection Diagrams for the A) Multi-institutional and B) National Cancer Database (NCDB) Cohorts.

Data collection included baseline patient demographics, primary tumor characteristics, surgical procedures, pathology, adjuvant therapies, recurrences, and follow-up. Time to initiation of adjuvant ICI was defined as weeks from definitive surgical resection (wide local excision or amputation, +/− lymph node dissection). Given the shift in practice away from routine completion lymph node dissection (CLND) following publication of the DeCOG-SLT and MSLT-II trials during the study period, patients were not required to undergo CLND nor were patients receiving CLND excluded.17, 18 This part of the study was approved by the Duke University Health System Institutional Review Board (IRB) (Pro0091710) and through Data Transfer Agreements and IRB approval at participating institutions.

Multi-Institutional Cohort Statistical Analysis

We first examined the relationship between time and RFS as the primary outcome that was calculated from the time of definitive surgical resection. We then stratified patients into three clinically meaningful time intervals for initiation of adjuvant ICI: within 6 weeks, 6–12 weeks, and greater than 12 weeks. The cutoff of six weeks was chosen due to its significance for initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy in other malignancies,11, 14 and that of twelve weeks was chosen because it is often the maximum timepoint at which randomization in adjuvant clinical trials can occur.6–8 Baseline demographics, tumor characteristics, treatments, and recurrence patterns were compared among the three groups using Pearson’s chi-squared test and the Kruskal-Wallis test for categorical and continuous variables, respectively. Recurrence patterns were categorized as local, regional, and distant; recognizing that some patients may recur in multiple sites.

Survival outcomes were examined using Kaplan-Meier methods and comparisons made with the log-rank test for univariate analyses, as well as Cox’s proportional hazards method for multivariate analyses. A conditional landmark analysis was performed to limit immortal time bias, including only patients with RFS greater than the 90th percentile of time to adjuvant ICI.19, 20 Additional subgroup analyses were conducted on 1) patients presenting with a new diagnosis of melanoma (excluding recurrent stage III disease); 2) patients with microscopic, occult stage III disease (SLN+ or microsatellites); and 3) patients receiving anti-PD-1 monotherapy.

Cox’s proportional hazards method was utilized to model the relationship between time to adjuvant ICI and RFS. The regression model incorporated known covariates, such as age, histology, primary tumor location, pathologic stage, adjuvant radiation, and nodal disease burden (in mm), designated a priori. Pathologic stage was chosen over clinical stage as it incorporates the quantity of lymph node metastases. Cases with missing data were excluded in multivariable regression. A two-tailed p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analysis was conducted in R version 4.1.1 (Vienna, Austria).

NCDB Data Source and Patient Selection

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) is a national clinical oncology database maintained through collaboration between the American College of Surgeons and American Cancer Society. De-identified patient-level data is entered by trained registrars from over 1,500 Commission on Cancer (CoC) accredited hospitals across the United States. Data collection includes patient demographics and tumor characteristics as well as treatments, post-operative outcomes, and OS. Altogether, the NCDB is estimated to capture 70–80% of new cancer diagnoses within the United States and provides greater statistical power to investigate the relationship of time to adjuvant immunotherapy (IO) with OS.21, 22 Of note, disease-specific and recurrence-free survival are not available in the NCDB. Patient data within the NCDB are de-identified and this part of the study was deemed exempt by the Duke University Health System IRB (Pro00111050).

The NCDB was queried for all patients with pathologic stage III cutaneous melanoma who underwent resection and received adjuvant IO between 2015–2019 (Figure 1B). Of note, the NCDB does not differentiate among IO agents and the time period of 2015–2019 was chosen to best estimate ICI compared to historic regimens (i.e. PEG-IFN, IL-2). Patients who initiated adjuvant IO greater than 180 days following surgery and those with missing survival were excluded. Time to initiation of adjuvant IO was defined as previously described.

NCDB Statistical Analysis

Patients were again stratified into three clinically meaningful time intervals for initiation of adjuvant immunotherapy: within 6 weeks, 6–12 weeks, and greater than 12 weeks. Baseline patient demographics and tumor characteristics were compared with the same methods described above. OS was calculated from the time of definitive surgical resection to limit immortal time bias. Survival analysis was performed with Kaplan-meier methods and compared among groups with the log-rank test. A two-tailed p-value less than 0.05 was considered significant. All statistical analysis was conducted in R version 4.1.1 (Vienna, Austria).

Results

Multi-Institutional Cohort: Patient, Tumor, and Treatment Characteristics

Altogether, 626 patients from four centers were identified that met study criteria. The median time to adjuvant ICI after resection was 7.1 weeks (IQR 4.8–10.6). The median follow-up was 28 months (IQR 15.4–44.3). There were 274 (39.5%) recurrence events during the follow-up period. The type of adjuvant ICI, in decreasing order of prevalence, included: nivolumab (68.1%), pembrolizumab (18.5%), ipilimumab (11%), or a combination of the three (2.1%). Five-hundred sixty-five (90.3%) patients received adjuvant ICI alone, while 51 (8.1%) patients received adjuvant ICI in combination with radiation. Two-hundred forty-six (39%) patients initiated adjuvant ICI within 6 weeks, 264 (42.2%) patients 6–12 weeks, and 118 (18.8%) patients greater than 12 weeks from surgery.

Baseline patient demographics, tumor- and treatment characteristics are shown in Table 1 stratified by time to adjuvant ICI. In summary, patients receiving ICI within 6 weeks of surgery were more likely to be older (median age 61 vs. 59 vs. 57 years), have more recent year of diagnosis (median 2019 vs. 2019 vs. 2017), and unknown BRAF status (22.9% vs. 13.7% vs. 14.4%) compared to patients starting ICI 6–12 and greater than 12 weeks after surgery, respectively (Table 1). These patients were also more likely to have macroscopic nodal disease (36.1% vs. 20.5% vs. 25.4%) and have a prior diagnosis of melanoma, now presenting with recurrent stage III disease (19.7% vs. 6.1% vs. 7.6%) (Table 1). Despite these differences, rates of lymph node dissection were similar among those initiating adjuvant ICI within 6 weeks and greater than 12 weeks from surgery (19.7% vs. 23.7%), with the lowest lymph node dissection rate among those starting therapy 6–12 weeks from surgery (12.1%) (Table 1). There was a trend towards greater nodal tumor burden (median 3.2 vs. 2.0 vs. 2.0 mm) in patients receiving ICI within 6 weeks of resection; however, there were no significant differences in pathologic stage, Breslow depth, rates of ulceration, nor greater presence of microsatellites (Table 1).

Table 1.

Baseline demographics and tumor characteristics for patients with resected, pathologic stage III cutaneous melanoma receiving adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) stratified by time to adjuvant ICI within the multi-institutional cohort.

| Variable | Overall N=626 |

Within 6 weeks N=244 |

6–12 weeks N=264 |

Greater than 12 weeks N=118 |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median [IQR]) | 60 [48, 70] | 61 [52, 70] | 59 [47, 70] | 57 [45, 66] | 0.03 |

| Sex (%) | 0.70 | ||||

| Male | 395 (63.1) | 158 (64.8) | 166 (62.9) | 71 (60.2) | |

| Female | 231 (36.9) | 86 (35.2) | 98 (37.1) | 47 (39.8) | |

| Race (%) | 0.69 | ||||

| Caucasian | 589 (94.1) | 234 (95.9) | 245 (92.8) | 110 (93.2) | |

| Black | 7 (1.1) | 1 (0.4) | 4 (1.5) | 2 (1.7) | |

| Latina | 3 (0.5) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Asian | 11 (1.8) | 4 (1.6) | 5 (1.9) | 2 (1.7) | |

| Other | 11 (1.8) | 1 (0.4) | 7 (2.7) | 3 (2.5) | |

| Missing | 5 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | 2 (0.8) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Year of Diagnosis (median [IQR]) | 2018 [2017, 2020] | 2019 [2017, 2020] | 2019 [2017, 2020] | 2017 [2016, 2018] | <0.001 |

| Primary Tumor Location (%) | 0.07 | ||||

| Head/Neck | 105 (16.8) | 37 (15.2) | 54 (20.5) | 14 (11.9) | |

| Trunk | 175 (28.0) | 65 (26.6) | 82 (31.1) | 28 (23.7) | |

| Upper Extremity | 122 (19.5) | 57 (23.4) | 43 (16.3) | 22 (18.6) | |

| Lower Extremity | 168 (26.8) | 61 (25.0) | 66 (25.0) | 41 (34.7) | |

| Unknown | 56 (8.9) | 24 (9.8) | 19 (7.2) | 13 (11.0) | |

| Histology (%) | 0.69 | ||||

| Superficial Spreading | 207 (33.1) | 74 (30.3) | 93 (35.2) | 40 (33.9) | |

| Nodular | 138 (22.0) | 55 (22.5) | 57 (21.6) | 26 (22.0) | |

| Acral Lentiginous | 61 (9.7) | 22 (9.0) | 26 (9.8) | 13 (11.0) | |

| Other | 220 (35.2) | 93 (38.1) | 88 (33.3) | 39 (33.1) | |

| Breslow Depth (mm, median [IQR]) | 3.1 [2.0, 5.0] | 2.9 [1.8, 5.0] | 3.3 [2.0, 5.5] | 3.0 [2.1, 4.5] | 0.40 |

| Ulceration (%) | 0.47 | ||||

| Absent | 259 (41.4) | 109 (44.7) | 106 (40.2) | 44 (37.3) | |

| Present | 304 (48.6) | 110 (45.1) | 135 (51.1) | 59 (50.0) | |

| Missing | 63 (10.1) | 25 (10.2) | 23 (8.7) | 15 (12.7) | |

| Microsatellites (%) | 0.328 | ||||

| Absent | 458 (73.2) | 171 (70.1) | 198 (75.0) | 89 (75.4) | |

| Present | 103 (16.5) | 40 (16.4) | 45 (17.0) | 18 (15.3) | |

| Missing | 65 (10.4) | 33 (13.5) | 21 (8.0) | 11 (9.3) | |

| BRAF Status (%) | 0.04 | ||||

| Unknown | 109 (17.5) | 56 (22.9) | 36 (13.7) | 17 (14.4) | |

| Negative | 358 (57.2) | 139 (57.0) | 150 (56.8) | 69 (58.5) | |

| Positive | 159 (25.4) | 49 (20.1) | 78 (29.5) | 32 (27.1) | |

| Presentation (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| New diagnosis | 552 (88.2) | 196 (80.3) | 248 (93.9) | 108 (91.5) | |

| Recurrence | 73 (11.7) | 48 (19.7) | 16 (6.1) | 9 (7.6) | |

| Missing | 1 (0.2) | 0 (0.0) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Nodal Disease Status (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Microscopic | 454 (72.5) | 156 (63.9) | 210 (79.5) | 88 (74.6) | |

| Macroscopic | 172 (27.5) | 88 (36.1) | 54 (20.5) | 30 (25.4) | |

| Insurance Status (%) | 0.75 | ||||

| None | 27 (4.3) | 7 (2.9) | 12 (4.5) | 8 (6.8) | |

| Government | 252 (40.3) | 100 (41.0) | 106 (40.2) | 46 (39.0) | |

| Private | 332 (53.0) | 130 (53.3) | 140 (53.0) | 62 (52.5) | |

| Missing | 15 (2.4) | 7 (2.9) | 6 (2.3) | 2 (1.7) | |

| Clinical Stage (%) | <0.01 | ||||

| IA | 7 (1.1) | 3 (1.2) | 4 (1.5) | 0 (0.0) | |

| IB | 76 (12.1) | 31 (12.7) | 33 (12.5) | 12 (10.2) | |

| IIA | 128 (20.4) | 39 (16.0) | 67 (25.4) | 22 (18.6) | |

| IIB | 147 (23.5) | 49 (20.1) | 60 (22.7) | 38 (32.2) | |

| IIC | 96 (15.3) | 34 (13.9) | 46 (17.4) | 16 (13.6) | |

| III | 172 (27.5) | 88 (36.1) | 54 (20.5) | 30 (25.4) | |

| Pathologic Stage (%) | 0.84 | ||||

| IIIA | 56 (8.9) | 23 (9.4) | 23 (8.7) | 10 (8.5) | |

| IIIB | 192 (30.7) | 74 (30.3) | 80 (30.3) | 38 (32.2) | |

| IIIC | 355 (56.7) | 139 (57.0) | 148 (56.1) | 68 (57.6) | |

| IIID | 23 (3.7) | 8 (3.3) | 13 (4.9) | 2 (1.7) | |

| Extent of Nodal Surgery (%) | <0.01 | ||||

| SLNB alone | 471 (75.2) | 172 (70.5) | 213 (80.7) | 86 (72.9) | |

| LND | 108 (17.3) | 48 (19.7) | 32 (12.1) | 28 (23.7) | |

| Not Specified | 47 (7.5) | 24 (9.8) | 19 (7.2) | 4 (3.4) | |

| Nodal Tumor Burden (mm) (median [IQR]) | 2.2 [0.7, 9.0] | 3.2 [1.0, 13.0] | 2.0 [0.5, 8.5] | 2.0 [0.9, 10.0] | 0.05 |

| Nodes Positive (median [IQR]) | 1.0 [1.0, 2.0] | 1 [1, 2] | 1 [1, 2] | 1 [1, 2] | 0.14 |

| Type of Adjuvant ICI (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Nivolumab | 426 (68.1) | 169 (69.3) | 192 (72.7) | 65 (55.1) | |

| Pembrolizumab | 116 (18.5) | 53 (21.7) | 38 (14.4) | 25 (21.2) | |

| Ipilimumab | 69 (11.0) | 13 (5.3) | 30 (11.4) | 26 (22.0) | |

| Combination | 13 (2.1) | 8 (3.3) | 3 (1.1) | 2 (1.7) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Cycles of Adjuvant ICI (median [IQR]) | 10 [4, 13] | 11 [5, 13] | 10 [4, 13] | 8 [3.5, 13] | 0.05 |

| Adjuvant Radiation (%) | 51 (8.1) | 11 (4.5) | 23 (8.7) | 17 (14.4) | <0.01 |

| Distance Travelled to Treating Facility (%) | <0.01 | ||||

| Within 30 miles | 251 (40.1) | 121 (49.6) | 90 (34.1) | 40 (33.9) | |

| 30–90 miles | 197 (31.5) | 73 (29.9) | 87 (33.0) | 37 (31.4) | |

| Greater than 90 miles | 176 (28.1) | 49 (20.1) | 86 (32.6) | 41 (34.7) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | |

| Care Structure (%) | <0.01 | ||||

| Fragmented | 178 (28.4) | 51 (20.9) | 82 (31.1) | 45 (38.1) | |

| Coordinated | 446 (71.2) | 192 (78.7) | 182 (68.9) | 72 (61.0) | |

| Missing | 2 (0.3) | 1 (0.4) | 0 (0.0) | 1 (0.8) | |

| Timing of Radiographic Axial Staging (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Preop | 197 (31.5) | 110 (45.1) | 65 (24.6) | 22 (18.6) | |

| Postop | 406 (64.9) | 123 (50.4) | 194 (73.5) | 89 (75.4) | |

| Not Specified | 23 (3.7) | 11 (4.5) | 5 (1.9) | 7 (5.9) | |

| Timing of Radiographic Intracranial Staging (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| Preop | 67 (10.7) | 39 (16.0) | 21 (8.0) | 7 (5.9) | |

| Postop | 350 (55.9) | 88 (36.1) | 181 (68.6) | 81 (68.6) | |

| Not Specified | 209 (33.4) | 117 (48.0) | 62 (23.5) | 30 (25.4) | |

| Time from Axial Staging to Adjuvant (days, median [IQR]) | 35 [17, 61] | 22 [11, 46] | 38 [21, 56] | 71 [39, 103] | <0.001 |

| Time from Intracranial Staging to Adjuvant (days, median [IQR]) | 27 [12, 52] | 15 [6, 32.5] | 27 [15, 45] | 60.5 [33.25, 84] | <0.001 |

| Second Primary Melanoma (%) | 18 (2.9) | 7 (2.9) | 8 (3.0) | 3 (2.5) | 0.97 |

Patients receiving adjuvant ICI within 6 weeks of surgery were more likely to travel shorter distances for treatment (49.6% vs. 34.1% vs. 33.9% < 30 miles) and receive adjuvant ICI at the same center as their surgical resection (78.7% vs. 68.9% vs. 61% coordinated care) compared to patients starting ICI 6–12 and greater than 12 weeks after surgery, respectively (Table 1). While post-operative radiographic staging was most common among all three groups, there was a greater proportion of patients with pre-operative staging among those with early initiation of ICI, although these patients had a shorter median time interval from staging to the start of therapy (Table 1). Nivolumab was the most common type of adjuvant ICI among all three groups and patients initiating ICI within 6 weeks of surgery had lower rates of ipilimumab than later timepoints (5.3% vs. 11.4% vs. 22.0%) (Table 1).

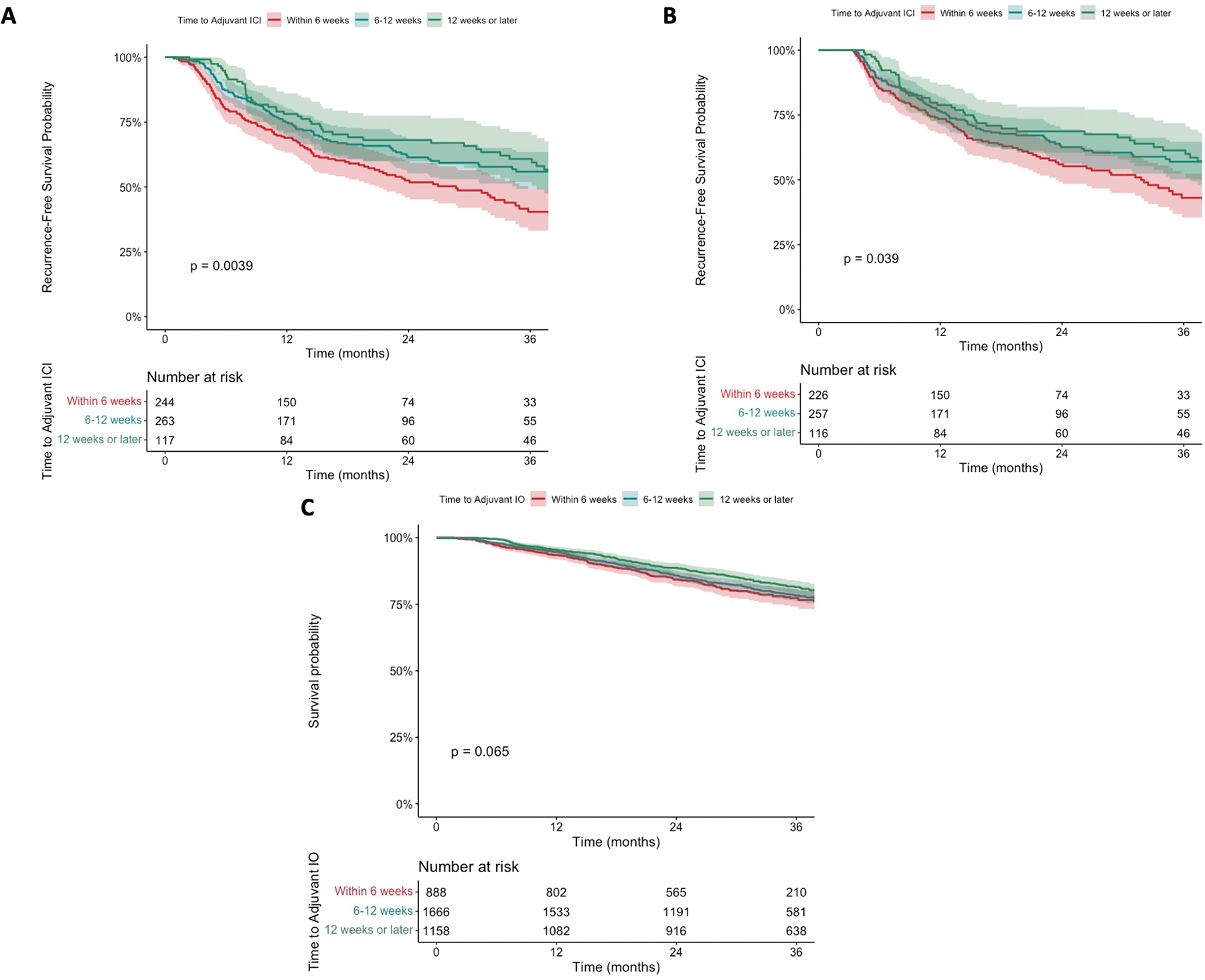

Multi-Institutional Cohort: Recurrence-Free Survival

Median RFS in the overall cohort was 37.9 months (95% CI 32.5–51.3) and 36-month RFS was 51.3% (95% CI 46.8–56.2). Patients who initiated adjuvant ICI within 6 weeks of surgery had worse RFS compared to patients starting therapy 6–12 and greater than 12 weeks from surgery (40.4% vs. 55.9% vs. 60.8% 36-month RFS, respectively; p=0.0039) (Figure 2A). Pairwise comparison of the Kaplan-meier curves revealed a significant difference in RFS for patients initiating adjuvant ICI within 6 weeks compared to both 6–12 weeks and greater than 12 weeks from surgery (p=0.009 and p=0.004, respectively); however, there was no significant difference in RFS between patients initiating adjuvant ICI 6–12 and greater than 12 weeks following resection (p=0.45). In a conditional landmark analysis excluding patients with a recurrence event prior to the 90th percentile of time to adjuvant ICI (104 days, landmark cohort N=599), the survival disadvantage for early initiation of therapy was preserved (Figure 2B). In prespecified subgroup analyses, earlier time to adjuvant ICI was associated with worse RFS in a subgroup of patients with new melanoma diagnoses (Supplemental Figure 1) as well as those with microscopic, occult stage III disease (Supplemental Figure 2). Among patients receiving anti-PD-1 monotherapy, this relationship was preserved (Supplemental Figure 3).

Figure 2.

Kaplan-meier curves for recurrence-free survival in patients with resected, pathologic stage III cutaneous melanoma stratified by time to adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) within the multi-institutional cohort. A) Entire cohort; B) Conditional landmark analysis. C) Kaplan-meier curves for overall survival in patients with resected, pathologic stage III cutaneous melanoma stratified by time to adjuvant immunotherapy (IO) within the National Cancer Database (NCDB) cohort.

Univariable and multivariable Cox regression models for RFS are shown in Table 2. In a multivariable Cox regression model, adjusting for age, histology, primary tumor location, adjuvant radiation, nodal tumor burden (mm), and pathologic stage, increased time to adjuvant ICI (per week) was associated with improved RFS (HR 0.96, 95% CI 0.93–0.99; p=0.01). Age, primary tumors of the trunk, increasing pathologic stage (IIIC/IIID vs. IIIA), and nodal burden (mm) were also independently associated with greater hazard of recurrence (Table 2).

Table 2.

Univariable and Multivariable Cox proportional hazards models of factors associated with recurrence free survival (RFS) in patients with resected pathologic III cutaneous melanoma receiving adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI). The adjusted multivariable model includes Age, Histology, Primary Tumor Location, Pathologic Stage, Nodal Burden (mm), Adjuvant Radiation, and Time to Adjuvant ICI. Pathologic stage incorporates clinical stage and nodes positive, to limit multicollinearity these variables were not included in the multivariable model. Complete case analysis was used with 464 complete cases with 203 recurrence events.

| Variable | Unadjusted Models | Adjusted Model | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| HR | 95% CI | p-value | HR | 95% CI | p-value | |

| Age (per 5 years) | 1.08 | 1.04–1.13 | <0.001 | 1.07 | 1.02–1.13 | <0.01 |

| Insurance Status (ref: none) | ||||||

| Government | 1.09 | 0.62–1.94 | 0.76 | |||

| Private | 0.78 | 0.44–1.38 | 0.40 | |||

| Coordinated Care (ref: fragmented) | 1.01 | 0.78–1.31 | 0.94 | |||

| Histology (ref: superficial spreading) | ||||||

| Nodular | 1.05 | 0.76–1.47 | 0.76 | 0.81 | 0.56–1.18 | 0.27 |

| Acral | 1.74 | 1.16–2.60 | 0.01 | 1.23 | 0.73–2.07 | 0.43 |

| Other | 0.95 | 0.71–1.27 | 0.70 | 0.83 | 0.56–1.22 | 0.34 |

| Primary Tumor Location (ref: head/neck) | ||||||

| Trunk | 1.38 | 0.94–2.02 | 0.10 | 1.82 | 1.13–2.92 | 0.01 |

| Upper Extremity | 1.13 | 0.75–1.71 | 0.56 | 1.38 | 0.82–2.32 | 0.23 |

| Lower Extremity | 1.43 | 0.98–2.10 | 0.07 | 1.58 | 0.94–2.67 | 0.09 |

| Unknown Primary | 0.56 | 0.30–1.03 | 0.06 | 0.30 | 0.11–0.80 | 0.02 |

| Pathologic Stage (ref: IIIA) | ||||||

| IIIB | 1.87 | 1.06–3.30 | 0.03 | 1.58 | 0.84–3.00 | 0.16 |

| IIIC | 2.48 | 1.44–4.28 | <0.01 | 2.23 | 1.21–4.10 | 0.01 |

| IIID | 5.90 | 2.80–12.43 | <0.001 | 4.91 | 2.15–11.24 | <0.001 |

| Nodal Tumor Burden (per mm) | 1.00 | 0.99–1.01 | 0.99 | 1.01 | 1.00–1.02 | 0.02 |

| Nodes Positive (per node) | 1.05 | 0.99–1.11 | 0.12 | |||

| Adjuvant Radiation (ref: none) | 1.03 | 0.68–1.57 | 0.89 | 1.43 | 0.85–2.41 | 0.18 |

| Time to Adjuvant ICI (per week) | 0.96 | 0.93–0.98 | <0.001 | 0.96 | 0.93–0.99 | 0.01 |

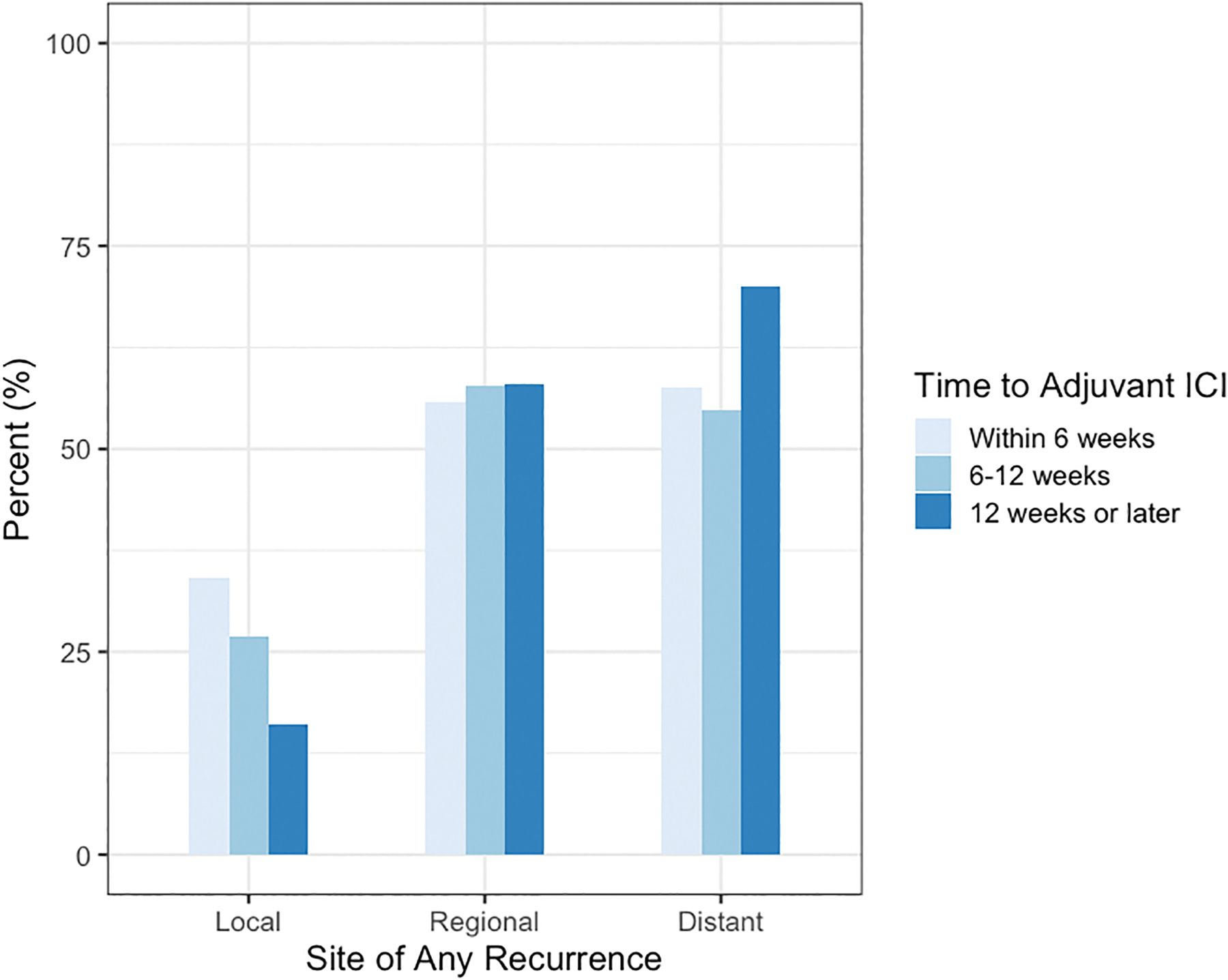

Multi-Institutional Cohort: Recurrence Patterns

Overall, 274 patients within the multi-institutional cohort had a recurrence event during follow-up. Recurrences were observed in the following distributions: 77 (28.1%) local, 156 (56.9%) regional, and 161 (58.8%) distant. 109 (39.8%) patients experienced recurrence at more than one site during follow-up. Among patients who recurred, there was a trend towards higher rates of local recurrence for patients receiving adjuvant ICI within 6 weeks (34.2% vs. 26.9% vs 16%) compared to patients starting therapy 6–12 and greater than 12 weeks from surgery (Figure 3, Supplemental Table 1). There was a trend towards local recurrence being the most common initial site of recurrence as well as the site of subsequent recurrences (Supplemental Figure 4). There were no difference in rates of regional or distant recurrences (Figure 3) nor second primary melanomas among groups (Table 1).

Figure 3.

Recurrence patterns stratified by time to adjuvant immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) and categorized into local, regional, and distant sites. Patients recurring in multiple sites are included in each respective category to preserve granularity.

NCDB Cohort and Overall Survival

Altogether, 3,712 patients were identified in the NCDB that met study criteria. The median time to adjuvant IO after oncologic resection was 9.1 weeks (IQR 6.1–13.4). The median follow-up was 32.7 months (IQR 23.9–45.3). There were 756 survival events during the follow-up period. Eight hundred eighty-eight (23.9%) patients initiated adjuvant IO within 6 weeks, 1,666 (44.9%) patients 6–12 weeks, and 1,158 (31.2%) patients greater than 12 weeks from surgery.

Baseline demographics and tumor characteristics are shown in Table 3. Similar to the multi-institutional cohort, patients receiving adjuvant IO within 6 weeks of surgery were older (median 61 vs. 58 vs. 57 years) and had more recent year of diagnosis (median 2018 vs. 2017 vs. 2016) compared to 6–12 and greater than 12 weeks of surgery. Patients receiving adjuvant IO within 6 weeks of surgery were more likely to have insurance (98.1% vs. 97.1% vs. 96.8%), receive treatment at a nonacademic center (61.8% vs. 61.9% vs. 53.9%), and travel shorter distances for treatment (median 14.9 vs. 14.8 vs. 17.3 miles) compared to those starting therapy beyond 12 weeks. Within this cohort, patients initiating adjuvant IO within 6 weeks of surgery were more likely to have pathologic stage IIIC disease (44.7% vs. 40.9% vs. 38.5%) and sentinel lymph node biopsy (SLNB) alone for regional nodal surgery (61% vs. 46.5% vs. 21.8%). On survival analysis, there was a trend towards worse OS for patients receiving adjuvant IO within 6 weeks compared to 6–12 and greater than 12 weeks (77.4% vs. 78.3% vs. 81.5% 36-month OS, p=0.065) (Figure 2C).

Table 3.

Baseline demographics and tumor characteristics for patients with resected, pathologic stage III cutaneous melanoma receiving adjuvant immunotherapy (IO) stratified by time to adjuvant IO within the National Cancer Database (NCDB) cohort.

| Variable | Overall N=3712 |

Within 6 Weeks N=888 |

6–12 Weeks N=1666 |

Greater than 12 Weeks N=1158 |

p-value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Age (median [IQR]) | 59 [47, 68] | 61 [49, 70] | 58 [46, 68] | 57 [46, 67] | <0.001 |

| Sex (%) | 0.82 | ||||

| Male | 2273 (61.2) | 547 (61.6) | 1011 (60.7) | 715 (61.7) | |

| Female | 1439 (38.8) | 341 (38.4) | 655 (39.3) | 443 (38.3) | |

| Race (%) | 0.69 | ||||

| White | 3592 (96.8) | 858 (96.6) | 1619 (97.2) | 1115 (96.3) | |

| Black | 31 (0.8) | 9 (1.0) | 12 (0.7) | 10 (0.9) | |

| Other | 89 (2.4) | 21 (2.4) | 35 (2.1) | 33 (2.8) | |

| Year of Diagnosis (median [IQR]) | 2017 [2016, 2018] | 2018 [2017, 2018] | 2017 [2016, 2018] | 2016 [2016, 2017] | <0.001 |

| Breslow Depth (median [IQR]) | 3.2 [1.8, 5.5] | 3.2 [1.7, 5.5] | 3.2 [1.9, 5.6] | 3.1 [1.8, 5.2] | 0.38 |

| Ulceration (%) | 1895 (51.1) | 448 (50.5) | 835 (50.1) | 612 (52.8) | 0.33 |

| Histology (%) | 0.21 | ||||

| Superficial Spreading | 2315 (62.4) | 535 (60.2) | 1041 (62.5) | 739 (63.8) | |

| Nodular | 1078 (29.0) | 273 (30.7) | 488 (29.3) | 317 (27.4) | |

| Acral | 153 (4.1) | 31 (3.5) | 66 (4.0) | 56 (4.8) | |

| Other | 166 (4.5) | 49 (5.5) | 71 (4.3) | 46 (4.0) | |

| Site (%) | 0.002 | ||||

| Head/Neck | 624 (16.8) | 171 (19.3) | 263 (15.8) | 190 (16.4) | |

| Trunk | 1392 (37.5) | 314 (35.4) | 659 (39.6) | 419 (36.2) | |

| Upper Extremity | 718 (19.3) | 191 (21.5) | 319 (19.1) | 208 (18.0) | |

| Lower Extremity | 940 (25.3) | 208 (23.4) | 401 (24.1) | 331 (28.6) | |

| Other | 38 (1.0) | 4 (0.5) | 24 (1.4) | 10 (0.9) | |

| Charlson-Deyo Comorbidity Score (%) | 0.49 | ||||

| 0 | 3010 (81.1) | 711 (80.1) | 1350 (81.0) | 949 (82.0) | |

| 1 | 500 (13.5) | 132 (14.9) | 213 (12.8) | 155 (13.4) | |

| 2 | 111 (3.0) | 24 (2.7) | 56 (3.4) | 31 (2.7) | |

| 3+ | 91 (2.5) | 21 (2.4) | 47 (2.8) | 23 (2.0) | |

| Insurance Status (%) | 0.002 | ||||

| None | 102 (2.8) | 17 (1.9) | 48 (2.9) | 37 (3.2) | |

| Government | 1526 (41.6) | 408 (46.6) | 685 (41.6) | 433 (37.8) | |

| Private | 2037 (55.6) | 451 (51.5) | 912 (55.4) | 674 (58.9) | |

| Medicaid Expansion State (%) | 2001 (63.4) | 481 (62.3) | 920 (65.9) | 600 (60.9) | 0.04 |

| Patient Residence (%) | 0.33 | ||||

| Rural | 55 (1.5) | 8 (0.9) | 31 (1.9) | 16 (1.4) | |

| Urban | 610 (17.0) | 150 (17.4) | 281 (17.4) | 179 (16.1) | |

| Metropolitan | 2923 (81.5) | 702 (81.6) | 1306 (80.7) | 915 (82.4) | |

| Distance Traveled (median [IQR]) | 15.8 [7.3, 35.8] | 14.9 [7.3, 31.2] | 14.8 [6.7, 35.1] | 17.3 [8.0, 39.3] | 0.01 |

| Academic Center (%) | 1507 (40.6) | 339 (38.2) | 634 (38.1) | 534 (46.1) | <0.001 |

| Education Quartile (% not finishing high school) | 0.73 | ||||

| > 17.5% | 472 (15.1) | 110 (14.7) | 208 (15.0) | 154 (15.4) | |

| 10.9–17.5% | 806 (25.8) | 198 (26.5) | 355 (25.7) | 253 (25.4) | |

| 6.3–10.8% | 986 (31.5) | 218 (29.1) | 446 (32.2) | 322 (32.3) | |

| < 6.3% | 864 (27.6) | 222 (29.7) | 374 (27.0) | 268 (26.9) | |

| Income Quartile (%) | 0.90 | ||||

| < $40,227 | 412 (13.2) | 101 (13.5) | 176 (12.7) | 135 (13.5) | |

| $40,227 – $50,353 | 703 (22.5) | 162 (21.7) | 322 (23.3) | 219 (22.0) | |

| $50,354 – $63,332 | 821 (26.3) | 188 (25.2) | 370 (26.8) | 263 (26.4) | |

| > $63,332 | 1190 (38.1) | 295 (39.5) | 515 (37.2) | 380 (38.1) | |

| Clinical Stage (%) | 0.34 | ||||

| I | 545 (20.2) | 127 (19.7) | 248 (20.3) | 170 (20.5) | |

| II | 1339 (49.7) | 316 (49.1) | 629 (51.5) | 394 (47.5) | |

| III | 810 (30.1) | 201 (31.2) | 344 (28.2) | 265 (31.9) | |

| Path Sub-Stage (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| IIIA | 874 (23.9) | 203 (23.0) | 398 (24.2) | 273 (24.2) | |

| IIIB | 1216 (33.2) | 262 (29.7) | 539 (32.8) | 415 (36.7) | |

| IIIC | 1503 (41.1) | 395 (44.7) | 673 (40.9) | 435 (38.5) | |

| IIID | 65 (1.8) | 23 (2.6) | 35 (2.1) | 7 (0.6) | |

| Surgery (%) | 0.34 | ||||

| Wide Local Excision | 3592 (96.8) | 856 (96.4) | 1620 (97.2) | 1116 (96.4) | |

| Amputation | 120 (3.2) | 32 (3.6) | 46 (2.8) | 42 (3.6) | |

| Regional Nodal Surgery (%) | <0.001 | ||||

| SLNB alone | 1522 (42.2) | 520 (61.0) | 755 (46.5) | 247 (21.8) | |

| TLND, no SLNB | 1392 (38.6) | 231 (27.1) | 577 (35.6) | 584 (51.5) | |

| CLND after SLNB | 694 (19.2) | 102 (12.0) | 290 (17.9) | 302 (26.7) | |

| Nodes Examined (median [IQR]) | 5 [2, 17] | 3 [1, 8] | 4 [2, 15] | 12 [4, 22] | <0.001 |

| Nodes Positive (median [IQR]) | 1 [1, 2] | 1 [1, 2] | 1 [1, 2] | 1 [1, 2] | <0.001 |

| Adjuvant Radiation (%) | 235 (6.3) | 37 (4.2) | 84 (5.0) | 114 (9.8) | <0.001 |

Discussion

Immune checkpoint inhibitors (ICI) are becoming increasingly utilized in the adjuvant setting for cutaneous melanoma. This dual registry analysis is the first study, to our knowledge, to investigate the impact of timing of adjuvant ICI on survival and recurrence patterns in resected stage III melanoma. In a multi-institutional cohort, we observed an inverse relationship between time to ICI and RFS. Our findings indicate that patients initiating therapy within 6 weeks of surgery may have worse outcomes compared to those starting therapy at least 6 weeks after resection. Importantly, there was no difference in recurrence outcomes for patients starting therapy later than 12 weeks from surgery compared to those within 6–12 weeks. A similar trend was observed when we examined OS in a large national cohort from the NCDB. Altogether, these findings suggest that patients with resected, stage III melanoma can wait at least 6 weeks to begin adjuvant ICI and that similar efficacy is observed in patients initiating ICI 12 weeks or later from surgery.

While the timing of adjuvant therapy has not been well studied for immunotherapies, similar questions have been asked for systemic chemotherapy and radiation. For these treatment modalities, consensus recommendations favor optimal recovery from surgery before initiating adjuvant therapy. These periods, often 6–8 weeks, allow for wound healing and rehabilitation.11, 13, 14 Within the colorectal cancer literature, there is evidence of worse outcomes with delayed initiation of adjuvant therapy beyond this time. Our study found similar characteristics related with delays in initiation of therapy, including lack of insurance, greater travel distance from the treatment facility, and fragmented care.12, 14, 15, 23, 24 While delays in initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy are largely viewed as detrimental to outcomes, we did not observe any meaningful difference in RFS, OS, nor recurrence patterns for delays beyond 12 weeks. These findings suggest preserved utility for adjuvant ICI in patients who may experience delays from surgical complications, poor wound healing, cracks in the referral system, or lack of access to care.

The underlying mechanisms for these findings are unclear. Our cohort did have lower 3-year RFS compared to the Keynote-054 trial (51.3% vs. 63.7%); however, our sample had a larger proportion of patients with pathologic stage IIIC disease (56.7% vs. 38.3–39%).6 We attempted to account for differences in disease specific variables including overall stage, nodal burden, and microsatellites that could explain our results, although, it is possible there were unmeasured confounders or differences in disease biology between the three groups that account for our findings. Indeed, there were more patients with macroscopic stage III disease in the early group, although final pathologic stage did not differ. There is also the possibility that surgery itself may have an immunosuppressive effect that limits the efficacy of adjuvant ICI if started in close proximity. Immunosuppression from surgical procedures has been described, and although surgery for melanoma can be less invasive than other oncologic procedures, we should not disregard its potential impact on the immune system.16, 25 The inflammation imposed by surgical insult may alter response to ICI. Some have proposed that the timing of such inflammation in relation to PD-1 blockade can dictate differentiation of precursor exhausted CD8+ T cells into terminally exhausted CD8+ T cells without the capability of responding to PD-1 blockade.26, 27 Hill et al suggest that inflammation predating PD-1 blockade may direct CD8+ T cells toward terminal exhaustion, resulting in greater tumor growth rather than control.26 These claims may support why we observed greater rates of local recurrence among patients receiving earlier ICI; however, if this is the primary mechanism, we would have expected to see differences in recurrence at the regional surgical site as well. Greater mechanistic study is needed to confirm such hypotheses, although, the clinical findings in our study align with such underpinnings. Further, our study is not the first to detect such differences in outcomes by timing of adjuvant ICI. Similar to our study, subgroup analyses of CheckMate 577 for esophageal cancer, favored adjuvant nivolumab in patients initiating therapy greater than 10 weeks from randomization compared to those initiating adjuvant nivolumab closer to surgery.28 Together, these observations support the need for further investigation into the implications of timing of adjuvant ICI on outcomes.

Timing of such therapies is being investigated on a larger scale by examining differences in neoadjuvant and adjuvant ICI. Findings from the SWOG S1801 trial comparing neoadjuvant and adjuvant pembrolizumab in patients with stage IIIB-IV melanoma, demonstrated longer event-free survival for patients receiving pembrolizumab in the neoadjuvant setting compared to adjuvant.29 These results strengthen the hypothesis that ICI may have greater effect when tumor cells and their infiltrating lymphocytes remain in vivo.30, 31 While neoadjuvant therapy may become standard of care for patients with macroscopic, clinically apparent stage III and IV melanoma, the timing of adjuvant ICI will remain relevant for patients with newly diagnosed microscopic, occult stage III disease and in patients with stage IIB/C melanoma for whom adjuvant therapy may be beneficial. Indeed, in a subgroup of patients with occult, microscopic stage III melanoma, we observed greater RFS if initiating adjuvant ICI at least six weeks from surgery. The clinical significance of the effect size with later initiation of therapy may be marginal and further study is needed prior to drawing definitive conclusions; however, these findings provide reassurance that starting adjuvant therapy beyond 6 weeks of surgery is safe and reasonable, particularly for patients who experience delays in care or among special populations (i.e. pregnancy). Further, these findings can be used to reassure patients that they do not need to start adjuvant therapy as soon as they receive their pathology report.

This study has several limitations. Similar to other retrospective studies there is selection bias for which we cannot fully adjust. For instance, we cannot account for patient and provider preferences in the timing of their care. Additionally, by investigating time to adjuvant ICI we introduce immortal time bias.20 For instance, patients initiating ICI greater than 12 weeks after surgery could not have experienced a recurrence event before that timepoint to be included in the study, which may inflate that group’s RFS. To limit this immortal time bias, we defined RFS from the time of surgery rather than diagnosis. Further, we conducted a conditional landmark subgroup analysis.19 This analysis excluded patients with early recurrence events that may bias survival outcomes. Importantly, the conditional landmark analysis was consistent with the overall cohort. Additionally, our multi-institutional cohort was not powered to detect differences in OS; therefore, we performed a separate analysis of OS in a larger cohort from the NCDB. While, the NCDB lacks granularity, such as the inability to differentiate IO regimens and determine recurrence, the trends we observed for OS were consistent with our findings for RFS within the more granular multi-institutional cohort. Of note, all four centers also contribute data to the NCDB so it is probable that some patients were included in both groups. Given the limited median follow-up of 33 months in the NCDB, it is possible that an insufficient number of events occurred to draw meaningful conclusions, and it is also possible these trends occurred due to chance. Attention to long-term follow-up with OS and melanoma-specific survival in our multi-institutional cohort will be important. Finally, our study did not include patients receiving adjuvant TT and these results should not be applied to that population. Despite these limitations, the strength of our study is the use of two registries to investigate an important question that would be unlikely to garner equipoise as the subject of a large, randomized clinical trial.

Altogether, this dual registry analysis reveals complexity in the relationship between the time interval from oncologic resection to adjuvant ICI and outcomes in stage III cutaneous melanoma. Our observations indicate that patients, particularly those with occult nodal disease who will not be identifiable preoperatively for neoadjuvant therapy, may benefit from waiting at least 6 weeks after resection before initiating adjuvant ICI. Further, adjuvant ICI may remain efficacious in patients who experience delays in care beyond 12 weeks from surgery, a population traditionally excluded from clinical trials. Additional work is needed to clarify the mechanisms of these observed findings. Ultimately, the timing of therapy should remain at the discretion of patients and their multidisciplinary care team with an emphasis on appropriate patient selection.

Supplementary Material

Synopsis.

In this dual registry analysis, increased time to adjuvant immune therapy was associated with improved recurrence-free survival for resected stage III melanoma. There was no difference in outcomes for patients starting adjuvant therapy 6–12 and > 12 weeks from resection.

Acknowledgements

The National Cancer Database (NCDB) is a joint project of the Commission on Cancer (CoC) of the American College of Surgeons and the American Cancer Society. The CoC’s NCDB and the hospitals participating in the CoC’s NCDB are the source of the de-identified data used herein; they have not verified and are not responsible for the statistical validity of the data analysis or the conclusions derived by the authors.

Disclosures:

K. Rhodin is supported by NIH 1R38AI140297. G. Beasley has received clinical trial funding paid to Duke University from Delcath, Istari, Replimune, Oncosec, Checkmate. G. Beasley has done one-time advisory board for Cardinal Health, Regeneron. G. Beasley is supported by NIH K08 CA237726-01A1. A. Salama discloses Research Funding (paid to institution): Ascentage, BMS, Ideaya, Immunocore, Merck, Olatec Therapeutics, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Replimune, Seattle Genetics; Advisory Boards: BMS, Iovance Biotherapeutics, Novartis, Pfizer, Regeneron Pharmaceuticals, Replimune. E. Bartlett discloses institutional research funding from Skyline Dx and honorarium from Excite International. G. Karakousis discloses institutional research support from and advisory board for Merck. J. Zager has done advisory board for Merck.

References

- 1.Siegel RL, Miller KD, Jemal A. Cancer statistics, 2020. CA Cancer J Clin. Jan 2020;70(1):7–30. doi: 10.3322/caac.21590 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Gershenwald JE, Scolyer RA, Hess KR, et al. Melanoma staging: Evidence-based changes in the American Joint Committee on Cancer eighth edition cancer staging manual. CA Cancer J Clin. Nov 2017;67(6):472–492. doi: 10.3322/caac.21409 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Huang AC, Zappasodi R. A decade of checkpoint blockade immunotherapy in melanoma: understanding the molecular basis for immune sensitivity and resistance. Nature Immunology. 2022/05/01 2022;23(5):660–670. doi: 10.1038/s41590-022-01141-1 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Carlino MS, Larkin J, Long GV. Immune checkpoint inhibitors in melanoma. The Lancet. 2021;398(10304):1002–1014. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(21)01206-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Seth R, Messersmith H, Kaur V, et al. Systemic Therapy for Melanoma: ASCO Guideline. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2020/11/20 2020;38(33):3947–3970. doi: 10.1200/JCO.20.00198 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Eggermont AMM, Blank CU, Mandala M, et al. Adjuvant Pembrolizumab versus Placebo in Resected Stage III Melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2018;378(19):1789–1801. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1802357 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Eggermont AMM, Chiarion-Sileni V, Grob J-J, et al. Prolonged Survival in Stage III Melanoma with Ipilimumab Adjuvant Therapy. New England Journal of Medicine. 2016;375(19):1845–1855. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1611299 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weber J, Mandala M, Del Vecchio M, et al. Adjuvant Nivolumab versus Ipilimumab in Resected Stage III or IV Melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;377(19):1824–1835. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1709030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Melanoma Cutaneous. Updated April 11, 2022. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/cutaneous_melanoma.pdf

- 10.Luke JJ, Rutkowski P, Queirolo P, et al. Pembrolizumab versus placebo as adjuvant therapy in completely resected stage IIB or IIC melanoma (KEYNOTE-716): a randomised, double-blind, phase 3 trial. Lancet (London, England). Apr 30 2022;399(10336):1718–1729. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(22)00562-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.National Comprehensive Cancer Network. NCCN Clinical Practice Guidelines in Oncology: Colon Cancer. Accessed August 31, 2022. https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/colon.pdf [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Turner MC, Farrow NE, Rhodin KE, et al. Delay in Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Survival Advantage in Stage III Colon Cancer. J Am Coll Surg. Apr 2018;226(4):670–678. doi: 10.1016/j.jamcollsurg.2017.12.048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Biagi JJ, Raphael MJ, Mackillop WJ, Kong W, King WD, Booth CM. Association Between Time to Initiation of Adjuvant Chemotherapy and Survival in Colorectal Cancer: A Systematic Review and Meta-analysis. JAMA. 2011;305(22):2335–2342. doi: 10.1001/jama.2011.749 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Salazar MC, Rosen JE, Wang Z, et al. Association of Delayed Adjuvant Chemotherapy With Survival After Lung Cancer Surgery. JAMA Oncol. May 1 2017;3(5):610–619. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.5829 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Rhodin KE, Raman V, Jawitz OK, Tong BC, Harpole DH, D’Amico TA. The Effect of Timing of Adjuvant Therapy on Survival After Esophagectomy. Ann Thorac Surg. Sep 2020;110(3):1023–1029. doi: 10.1016/j.athoracsur.2020.03.040 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Bakos O, Lawson C, Rouleau S, Tai L-H. Combining surgery and immunotherapy: turning an immunosuppressive effect into a therapeutic opportunity. Journal for ImmunoTherapy of Cancer. 2018/09/03 2018;6(1):86. doi: 10.1186/s40425-018-0398-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Leiter U, Stadler R, Mauch C, et al. Complete lymph node dissection versus no dissection in patients with sentinel lymph node biopsy positive melanoma (DeCOG-SLT): a multicentre, randomised, phase 3 trial. The Lancet Oncology. 2016;17(6):757–767. doi: 10.1016/S1470-2045(16)00141-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Faries MB, Thompson JF, Cochran AJ, et al. Completion Dissection or Observation for Sentinel-Node Metastasis in Melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2017;376(23):2211–2222. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1613210 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Dafni U Landmark analysis at the 25-year landmark point. Circ Cardiovasc Qual Outcomes. May 2011;4(3):363–71. doi: 10.1161/circoutcomes.110.957951 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Giobbie-Hurder A, Gelber RD, Regan MM. Challenges of guarantee-time bias. J Clin Oncol. Aug 10 2013;31(23):2963–9. doi: 10.1200/jco.2013.49.5283 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Raval MV, Bilimoria KY, Stewart AK, Bentrem DJ, Ko CY. Using the NCDB for cancer care improvement: an introduction to available quality assessment tools. J Surg Oncol. Jun 15 2009;99(8):488–90. doi: 10.1002/jso.21173 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Boffa DJ, Rosen JE, Mallin K, et al. Using the National Cancer Database for Outcomes Research: A Review. JAMA Oncol. Dec 1 2017;3(12):1722–1728. doi: 10.1001/jamaoncol.2016.6905 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Haynes AB, Chiang YS, Boland GM, et al. Socioeconomic and clinical factors associated with delayed initiation of adjuvant chemotherapy for stage III colon cancer. Journal of Clinical Oncology. 2012/12/01 2012;30(34_suppl):173–173. doi: 10.1200/jco.2012.30.34_suppl.173 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Cham S, Huang Y, Melamed A, et al. Fragmentation of surgery and chemotherapy in the initial phase of ovarian cancer care and its association with overall survival. Gynecol Oncol. Jul 2021;162(1):56–64. doi: 10.1016/j.ygyno.2021.04.032 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tang F, Tie Y, Tu C, Wei X. Surgical trauma-induced immunosuppression in cancer: Recent advances and the potential therapies. Clinical and Translational Medicine. 2020;10(1):199–223. doi: 10.1002/ctm2.24 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hill M, Segovia M, Russo S, Girotti MR, Rabinovich GA. The Paradoxical Roles of Inflammation during PD-1 Blockade in Cancer. Trends in Immunology. 2020;41(11):982–993. doi: 10.1016/j.it.2020.09.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Miller BC, Sen DR, Al Abosy R, et al. Subsets of exhausted CD8(+) T cells differentially mediate tumor control and respond to checkpoint blockade. Nat Immunol. Mar 2019;20(3):326–336. doi: 10.1038/s41590-019-0312-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Kelly RJ, Ajani JA, Kuzdzal J, et al. Adjuvant Nivolumab in Resected Esophageal or Gastroesophageal Junction Cancer. New England Journal of Medicine. 2021;384(13):1191–1203. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2032125 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Patel S, Othus M, Chen Y, et al. Neoadjuvant-Adjuvant or Adjuvant-Only Pembrolizumab in Advanced Melanoma. New England Journal of Medicine. 2023;388: 813–823. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2211437. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Sarver M, Brown MC, Rhodin KE, Salama AKS, Beasley GM. Predictive factors of neoadjuvant immune checkpoint blockade in melanoma. Hum Vaccin Immunother. May 31 2022;18(3):1943987. doi: 10.1080/21645515.2021.1943987 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Robert C Is earlier better for melanoma checkpoint blockade? Nat Med. Nov 2018;24(11):1645–1648. doi: 10.1038/s41591-018-0250-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.