Abstract

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is an increasingly common inflammatory allergic disease of the esophagus characterized by esophageal eosinophilia and symptoms of esophageal dysfunction. The therapeutic landscape has rapidly evolved for this emerging type 2 inflammatory disorder. We review traditional therapies including updates and expert opinions, in addition to promising therapies on the horizon and the history of therapies that failed to meet endpoints and highlight knowledge gaps for future investigations.

Keywords: Eosinophilic esophagitis, Allergy, Treatment, Updates

Introduction

Eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE) is a chronic allergic inflammatory disease that affects the esophagus. In 2018, a joint task force of allergists and gastroenterologists updated guidelines for diagnosis of EoE. One of the most significant changes from these guidelines is no longer requiring proton pump inhibition (PPI) failure for the diagnosis of EoE (1). Esophageal symptoms, in addition to finding 15 or more eosinophils per high power field (mm sq) in the absence of other causes of esophageal eosinophilia confirm the diagnosis, whether a patient has undergone a PPI trial. In addition to eosinophilic infiltration of the esophageal mucosa, there are characteristic epithelial changes and underlying lamina propria fibrosis that can be identified on histology.(2) The most classic esophageal symptom for adults in particular is dysphagia; however, EoE can manifest as heartburn, abdominal pain, failure to thrive feeding difficulties, or vomiting, the latter two of which are more common in pediatric patients.(3) Left untreated, EoE can lead to strictures and narrowing of the esophagus, which can result in food impactions requiring medical interventions and dilation highlighting the importance of addressing underlying, ongoing inflammation and to improve patient quality of life with symptom resolution.(4) For an accurate diagnosis, expert consensus recommends a minimum of 6 biopsies taken from the length of the esophagus (distal, and mid/proximal) and should be obtained in any patients where EoE is expected, regardless of the endoscopic appearance (e.g. grossly normal appearing which can occur ~30% of the time).(5) Interval endoscopies to evaluate treatment responses are required, even if patients symptoms improve. Similar to inflammatory bowel disease, symptoms alone are not sufficient to evaluate response to therapy. It is also recommended that endoscopic reference scoring (EREFS) should be performed and monitored at each exam.(4, 6)

After the diagnosis of EoE is established or the status of active EoE is confirmed, treatment is necessary to alleviate symptoms. Moreover, as touched on above, treatment of ongoing, active inflammation is necessary to prevent fibrotic complications including strictures and narrowing. Goals of treatment in EoE include inducing histologic remission (defined as less than 15 eosinophils per hpf) and relieving symptoms of esophageal dysfunction. Consequently, these two goals are often co-primary outcomes in the evaluation of new therapies.

EoE is thought to largely be food antigen-driven, given that elimination diets or elemental formula can be effective treatments, though methods to identify causative allergens other than empiric elimination diets have been elusive.(7, 8) Similar to other allergic pathologies such as asthma, EoE has been associated with a Th2 inflammatory response.(9) Characteristic Th2 cytokines such as IL-33, TSLP, IL-4, IL-5 and IL-13 have been implicated. Esophageal biopsies have elevated expression of TSLP, IL-33, and IL-13.(10, 11, 12) Genetic studies have identified susceptibility at Th2 associated genes such as TSLP, supporting the involvement of type 2 immunity.(13) IL-13 is thought to drive many of the characteristic epithelial changes seen in EoE and stimulate expression of eotaxin-3, a potent eosinophil chemoattractant.(14, 15) Esophageal tissue eosinophils have high expression of IL-4, IL5 and IL-13 as well as the IL-33 receptor in EoE patients.(16) In addition to eosinophils, other cells present in the esophagus in EoE include mast cells and pathogenic effector Th2 cells that express IL4, IL5, and IL13.(16, 17, 18, 19, 20) Defective inherited or acquired defects in esophageal innate barrier function are germane to EoE pathophysiology, perhaps promoting increase antigen uptake and stimulation of adaptive immunity.(21, 22)

Off-label, approved, and investigative treatments for EoE include PPI, topical corticosteroids, dietary therapy, and biologic and small molecule therapies, which will all be reviewed in this article. In terms of treatment guidelines, the AAAAI/ACAAI Joint Task Force on Allergy/Immunology Practice Parameters and AGA collated practice parameters that were published in 2020 and will be reviewed as appropriate regarding therapy here.(23) Importantly, many of these recommendations were made compared to no therapy instead of comparing treatments head-to-head, and therefore the recommendations should be interpreted with this in mind.

Therapeutic approaches

Proton pump inhibition

Proton pump inhibitors represent one of the earliest treatment modalities for EoE given the disease previously required PPI treatment failure and its early association with reflux symptoms.(24) PPIs are used at high doses in EoE (generally omeprazole 40 mg BID in adults and 1-2 mg/kg/day in children) and in general have approximately 30-50% efficacy inducing remission. PPIs in general are very safe medications, with few and rare risks including potential for infections, decreased vitamin and nutrient absorption or renal injury.(25, 26) While concerns regarding the safety of PPIs has been postulated, most studies examining negative effects of PPIs have been using retrospective and claims-based data, which is subject to profound confounding and bias and conflicts with high quality randomized trial data.

Several studies have shown that endoscopic, genetic, and transcriptional phenotypes are largely indistinguishable between PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia and PPI-non-responsive EoE.(27, 28, 29) Mechanisms for PPIs effectiveness is thought to be related in part to inhibition of eotaxin via K+/H+ ATPase on esophageal epithelial cells in a calcium channel dependent manner.(30) It is important to note this property is intrinsic only to PPIs, and not for example other methods of acid suppression such as histamine blockade suggesting it is not merely acid neutralization but a property of ATPase inhibition. Other investigators performing transcriptional analyses on PPI treated esophageal epithelial cells suggest inhibition of IL-13 and its downstream effector cascades may also be at play, particularly by activation of the aryl hydrocarbon receptor by PPIs.(31)

In general, the field has evolved from mutual exclusivity of gastroesophageal reflux disease (GERD) and EoE to recognizing a patient can have both. Some experts believe that low eosinophil numbers between 0-15 in the esophagus are suggestive of GERD induced injury resulting in esophageal eosinophilia or evolving EoE, though data for distinguishing is sparse and both may be true.

Recent updates in both long-term efficacy of PPI as well as re-trial of PPI after a steroid induction have shown promising results. In a single center study of adults with EoE, long term clinical and histologic remission rates measured at a mean of 3.6 years post introduction was around 60% rendering it an effective long-term therapy.(32) In addition, a retrospective review of 18 patients who were initially refractory to PPI then were treated with topical corticosteroids that induced remission were again later treated with PPI as a maintenance therapy.(33)

Investigators looked at 12 weeks post PPI re-introduction and found sustained remission on PPI at this time point. Further investigation into the duration of remission is warranted. Though this is an interesting approach, a 12-week post-PPI reintroduction follow up timeline may be confounded by lasting effects of topical corticosteroids as some patients have sustained remission post topical steroid removal for 3-6 months, where by 9 months, many patients will have recurrence.(34) However, head-to-head and combination therapy trials have not been carried out and are urgently needed.

There is no specific data on the use of PPIs in pregnant patients with EoE. In general, most PPIs are rated as Category B (No risk in animal studies [there are no adequate studies in humans, but animal studies did not demonstrate a risk to the fetus]), except for omeprazole which is rated Category C (Risk cannot be ruled out. There are no satisfactory studies in pregnant women, but animal studies demonstrated a risk to the fetus; potential benefits of the drug may outweigh the risks.) It has been previously recommended that patients actively seeking to conceive be counseled about a small but modestly increased risk of major birth defects with PPI use in the 4 weeks before conception, but large meta-analyses and cohort studies have otherwise not found an association between PPI use during pregnancy and adverse pregnancy outcomes.(35, 36) PPIs are known to be excreted in breastmilk and there is limited data regarding the effects of the high doses used in EoE, though there are no reports of adverse effects in infants.(37, 38)

In summary, PPIs are generally very safe therapeutic options for all patients.

Swallowed topical corticosteroids

Swallowed topical corticosteroids are among the best evaluated drugs regarding efficacy and safety for EoE, and their use over no treatment is recommended strongly with a moderate level of evidence in the 2020 AGA/Joint Task Force treatment guidelines.(39) A technical review accompanying these guidelines found that after aggregating 8 studies with 437 enrolled patients, treatment with topical budesonide or fluticasone had a histologic response rate of approximately two-thirds of subjects, though recent trials of budesonide orodispersible tablets response rates up to greater than 90% at 6 weeks.(40, 41, 42). Rate of symptomatic response varies between studies, and there appears to be an endotype of eosinophilic esophagitis that is resistant to topical steroid treatment.(43, 44, 45) Factors that predict non-response to steroids include dilation at baseline prior to initiation of steroids, edema/decreased vascularity seen on baseline endoscopy, hiatal hernia, and increased BMI.(46, 47, 48) Factors that have been associated with response to steroids include older age and the presence of food allergies.(47) Topical corticosteroids are also conditionally recommended as a long-term treatment with very low-quality evidence in the 2020 treatment guidelines. It is noted that after initial remission, there are some patients who might prefer avoidance of long-term steroid use over recurrence of symptoms, and continued monitoring is recommended.(39)

Currently in the United States, topical corticosteroids are used off-label, either by repurposing corticosteroid inhalers used for asthma or as compounded slurries. Initial treatment with either oral viscous budesonide (OVB) or a fluticasone metered dose inhaler (MDI) has been shown to be equivalent in a double-blind, double-dummy trial.(49) Optimal doses for induction and maintenance for these medications have not yet been determined and typical initial dosing varies (adults: fluticasone MDI 440-880 mcg twice daily or OVB 2 mg daily; children: fluticasone MDI 88-440 mcg twice to four times daily or OVB 1 mg daily).(50) Previous studies have indicated that a 50% dose reduction after initial induction therapy can remain effective in 73-93% of subjects, though more recent data suggests that loss of steroid response is common in adult patients responding to topical steroids and is associated with dose reduction.(44, 51) When using topical corticosteroids to treat EoE, we recommend repeat endoscopy after 8-12 weeks of induction therapy to evaluate for histologic response. If induction is successful, a reduction in the dose of steroids can be considered, considering patient response, patient preference, and potential side effects.

Though topical corticosteroids are subject to first-pass hepatic metabolism, adrenal suppression has been reported in individuals on topical corticosteroid therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis.(52) Guidelines for screening have not been established. Previous work has suggested that lower BMI and increased steroid dosage increases risk for adrenal suppression in EoE patients on topical corticosteroids.(53, 54) In a recent report, there was no difference in the daily steroid dose between those who did and did not develop adrenal insufficiency while on swallowed topical corticosteroids, suggesting that other unknown factors are more important and that all patients may benefit from screening.(55) Esophageal candidiasis has been reported in up to 30% of subjects on topical corticosteroid therapy for EoE, and patients with suspicious symptoms should be evaluated and treated.(56, 57) Beyond treatment with fluconazole for 14-21 days, management of steroid doses after an episode of candida is less well-defined. While there is little data, expert opinion supports a patient-level discussion regarding the role of steroid reduction in asymptomatic patients versus continuation at current dosing. Growth suppression is also a concern with long-term steroid use in children. In a 24-week open label extension study of budesonide after a 12-week randomized double-blind study, there was a trend towards decreased growth velocity but no decrease in sex-matched height for age Z-score in the 14 subjects aged 11-18.(58) Conversely, a study of 54 children on long-term swallowed fluticasone (mean follow-up 20.4 months) found no effect on growth and only 3 cases of asymptomatic Candida which resolved after fluticasone treatment.(59) Though the risk of growth suppression is likely small, height and growth velocity should be monitored in children on swallowed steroid treatment for EoE.

There is no specific data on swallowed corticosteroids in pregnant patients with EoE. Corticosteroids are classified as Category C during pregnancy and have been associated with small increased risks of adrenal insufficiency, premature rupture of membranes, and cleft palate. In asthma, budesonide is the maintenance inhaled corticosteroid of choice due to reassuring prior studies, though national guidelines note that other formulations of inhaled steroids have not been shown to be harmful.(60) In IBD, higher doses of budesonide than in EoE are often used in pregnant patients safely.(35) In breastfeeding, nasal, oral, and inhaled corticosteroids are considered acceptable, though there is evidence that very small amounts may be excreted in breast milk.(37)

Several formulations of topical steroids are being evaluated in formal clinical trials. In Europe, Canada, and Australia, topical budesonide as an orodispersible tablet (BOT) is approved for adults with EoE and is widely and safely used. In two recent phase III trials of this formulation of budesonide, clinical and histologic remission were superior with BOT compared to placebo in both short- and long-term uses of this medication.(41, 42) Notably, more patients experienced histologic remission compared to clinical remission, but in the largest study of 204 subjects greater than 70% of those on one of two BOT doses (0.5 mg BID or 1 mg BID) experienced both clinical and histologic remission.(41) A fluticasone orodispersible tablet (ODT) has also recently been evaluated. In a phase IIb trial of 106 adults with EoE, histologic response rates at 12 weeks were 80% for 3 mg twice daily, 67% for 3 mg at bedtime, 86% for 1.5 mg twice daily, 48% for 1.5 mg at bedtime, compared to 0% for placebo. EREFS and dysphagia frequency also improved with treatment compared to placebo.(61) A phase III trial of budesonide oral suspension (BOS) has also recently been reported which randomized 318 subjects with EoE to either BOS or placebo in a 2:1 ratio. At 12 weeks, 53% on BOS had a histologic response to treatment (compared to 1% on placebo) and 52.6% on BOS had a dysphagia symptom response (compared to 39.1% on placebo).(62) A small minority of subjects in these trials experienced oral/esophageal candidiasis or adrenal suppression but overall these medications were very well-tolerated.(41, 61, 62)

In summary, corticosteroids remain an excellent option for EoE treatment, and these new formulations may make it easier to facilitate treatment if they are approved by US regulatory authorities in the near future.

Systemic Immunosuppression

Prednisone has been shown to induce both histologic and symptomatic improvement in eosinophilic esophagitis. In a trial comparing prednisone to swallowed fluticasone, prednisone led to a greater degree of histologic improvement, but did not have a greater effect on symptom improvement compared to fluticasone.(56) Given the potential for greater systemic side effects, it has been suggested to reserve oral prednisone for patients with EoE who either do not respond to all other treatments or who require rapid symptom relief, particularly in the setting of pregnancy where prednisone has a longer history than newer medications such as dupilumab(57) With the new approval of dupilumab and other biologics on the horizon, the role of systemic corticosteroids for patients refractory to initial treatment with PPI, dietary elimination, or swallowed corticosteroids is likely to diminish.

Azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine have also been used to treat steroid-dependent EoE in a case report of 3 patients, but their safety and efficacy have not been studied in a larger population.(57, 63)

Due to their unfavorable side effect profile compared to other available treatments, we suggest against using non-specific systemic immunosuppressive medications except in extremely refractory patients.

Dietary Therapies

EoE is generally thought to be a non-IgE driven food allergy and dietary elimination has long been a staple of treatment. Historically, much of the data for EoE as a food allergy is based on indirect evidence such as stepwise diet elimination. However, this landscape is beginning to change with recent studies identifying peripherally circulating food antigen-specific T cells and mucosal associated food-specific antibodies in patients with EoE.(18, 64, 65) While early, these explorations pose exciting new endeavors for identifying triggers for patients.

Much of the dietary studies performed in EoE have been carried out in Spain and the United States with response rates varying from ~60% to greater than 90% for broad elimination and elemental diets.(66, 67, 68, 69) Historically, EoE was managed either with elemental diets removing all complex molecular structures including proteins and later with six food elimination diets.(70) Elemental diet success ranges from roughly 70-90% in children and adults, however the logistical and palatable challenges particularly for adults tend to make it an uncommon therapy.(7, 71, 72) Six food elimination diets (6FED) target removal of the most common food allergens: dairy, wheat, eggs, soy, peanuts and tree nuts, and fish and shellfish. Dairy is the most common trigger for pediatric patients ranging from ~50-70% of patients, whereas wheat is the most common allergen for adults 40-50%.(73, 74) These foods are then slowly reintroduced one or two at a time with interval upper endoscopy and biopsies to determine response and identify food triggers. A notable consideration particularly for empiric diet elimination in pediatric patients is the repetitive nature of endoscopy and sedation. This may influence patients, parents, and providers in which foods and how many are chosen, or pursuit of elemental diets, which tend to have relative ease in pediatric populations. Additionally, considerations regarding growth and nutrition may influence the risk-benefit calculation for elimination diets in children with eosinophilic esophagitis presenting with failure-to-thrive.

In 2018, Molina-Infante et al performed the “Step-up Diet Elimination” study which changed the way many approach diet therapy beginning with the two most common allergen triggers, wheat and dairy.(73) In their study, 43% of patients responded to elimination of these foods, while non responders went on to add eggs and soy to elimination. Similarly, if there was a lack of response to four food elimination diet (4FED), nuts and shellfish were added to the elimination to complete the full 6FED. More recently in the United States, Zalewski et al published long-term results for real world 6FED being lower at 54%.(67)

It is worth noting that most dietary studies have not had a control comparator arm until recently. In a multi-center study led by the Consortium for Eosinophilic GI disease Researchers (CEGIR) investigators and sites, children were randomized to undergo a 1 food elimination diet (1FED) with dairy versus 4FED. Interestingly, 1FED had similar response rates to 4FED (44.1% vs 41.2%; p=1.0), although 1FED had significantly better quality of life metrics than 4FED.(75) In a similar vein, CEGIR later conducted another multi-site study (SOFEED) including adults with 1FED versus 6FED.(76) Once again, 1FED had similar response rates to 6FED (34% vs 40%; p=0.58), where the 6FED remission rate was notably low. Additionally, both diets had comparable improvements in peak eosinophil counts, EoE histologic severity scores, EREFS scores, EoE symptom severity scores, and quality of life measures. Similarly, Wechsler et al reported 51% remission rate with dairy elimination.(74) These variable broad elimination diet results suggest that extensive education and support is required for successful implementation and maintenance of diet eliminations.(77)

Regarding options after unsuccessful dietary elimination, in the SOFEED study comparing 1FED to 6FED, subjects who failed the 1FED had the option to transition to 6FED, and 43% of the subjects who transitioned from 1FED to 6FED had histologic response. Subjects who failed the 6FED had the option to transition to swallowed fluticasone, and 82% of the subjects who elected to do so had histologic response. This study also identified predictive value of baseline milk-specific IgG4 in predicting responsiveness to 1FED.

Overall, these studies suggest dietary elimination trending towards less restrictive diets such as 1FED or 2FED may be as successful as broader elimination diets and feasible options for patients with EoE, though having the dietician support and education is paramount to execute successfully. We suggest at least considering eliminating fewer foods such as 1FED particularly for pediatric patients or 2FED considering this recent data and a recent systematic review.(78) No matter the dietary consideration, as with all dietary therapies we recommend involvement of a Registered Dietician or other dedicated educational resources directed towards guidance for patients.

There is no data on elimination diet in pregnant patients with EoE. In a Cochrane review of women avoiding dietary antigens during pregnancy, the avoidance diet was associated with lower weight gain during pregnancy. There was also a nonsignificant association with higher preterm birth and with lower birth weight.(79) This certainly underscores the importance of involving a dietician with pregnant patients interested in an elimination diet.

A growing but poorly understood aspect of dietary therapy includes oral immunotherapy (OIT). While this is not a therapy for EoE, increasingly, providers have noted the association of EoE in patients undergoing OIT. Estimates for the rate of EoE during OIT ranges from 5.1% (confirmed cases) to 34% (symptoms possibly related to EoE during OIT), but the true prevalence is difficult to estimate given that most patients with significant gastrointestinal symptoms during OIT stop therapy without undergoing endoscopy.(80) Though symptoms and histological abnormalities typically remit with cessation of OIT, in some patients EoE continues. Whether this represents worsening of unknown, pre-existing EoE or the induction of EoE by OIT remains an area under investigation. It is recommended that OIT providers perform a detailed gastrointestinal history prior to initiation of OIT and discuss the potential for development of EoE.

In summary, dietary interventions remain a common and effective therapy for patients with EoE, and implementation should occur with considerations of age, patient motivation and educational resources.

Dilation

While esophageal dilation does not treat the underlying inflammation driving fibrosis and stricturing, we do recommend dilation to a goal of 15-18mm in patients with clinically significant esophageal stricture.(81) The timing of dilation is not well established, in an ideal scenario inflammation is controlled though this is not always possible. Dilation in general is safe, and risk of perforation and bleeding is very rare.(82)

Biologic and small molecule therapies

Dupilumab

Dupilumab is a monoclonal antibody against the alpha subunit of the IL-4 receptor, which is shared by the IL-13 receptor. Blockade of this subunit effectively blocks signaling from both cytokines, which are key to the pathogenesis of EoE.(83, 84) Dupilumab has recently become the first Federal Drug Administration (FDA)-approved treatment for eosinophilic esophagitis in May 2022. In the phase III, three-part LIBERTY-EoE-TREET trial which included adults and adolescents, weekly subcutaneous dupilumab 300 mg resulted in significant histologic remission (<6 eos/hpf in 59.9% vs 5.1% placebo in part A, 58.8% vs 6.3% placebo in part B) and significant decreases in dysphagia scores compared to placebo. The most common side effects were injection site reaction (16-37.5%), nasopharyngitis (11.9% in part A), and fever (6.3% in part B). Conjunctivitis, a notable side effect in atopic dermatitis patients treated with dupilumab, occurred at a low rate. Blood eosinophil counts did not increase. Of note, part B of this study did evaluate every 2-week dosing, as is used in asthma and eczema, and though this dose induced histologic remission at a rate similar to weekly dosing, it did not meet endpoints related to the dysphagia score.(85) In children, there is evidence that dupilumab prescribed for asthma, atopic dermatitis, or nasal polyposis leads to histologic and symptomatic improvement in patients with EoE.(84) There is an ongoing phase III trial in children (NCT04394351), with preliminary results reporting 68% (higher dose) and 58% (lower dose) of pediatric subjects achieving histologic remission after 16 weeks of treatment. In this initial analysis, there was no difference in symptomatic improvement at 16 weeks with dupilumab compared to placebo.(5, 86) At this time, dupilumab is approved for patients aged 12 years and older for eosinophilic esophagitis.

Where dupilumab fits into the treatment algorithm for EoE is not currently established; as approved, it could be used as first line, “top-down” treatment or as a secondary treatment for those who have failed other therapies. Its use in pregnant patients is not known at this time. In a recent expert opinion piece, Aceves et al suggest that dupilumab should be considered for the below situations: (87)

Patients who also have asthma, atopic dermatitis, or chronic rhinosinusitis with polyposis meeting criteria for biologic therapy

Patients with strictures

Patients with failure to thrive, weight loss, or growth impairment due to EoE

Patients who require elemental formula for 50+% of their daily caloric intake due to EoE

Patients with severe inflammation requiring frequent oral glucocorticoids

Patients who have failed first line (topical corticosteroid, PPI, diet) therapy

Patients who have experienced adverse effects from other therapies

Lirentelimab

Lirentelimab is a monoclonal antibody against Siglec-8, which is expressed on the surface of eosinophils and mast cells. Because lirentelimab facilitates depletion of eosinophils via antibody-dependent cellular cytotoxicity (ADCC) and inactivates mast cells, its use has been studied in EoE. (88, 89) While early studies were very promising for lirentelimab, in a phase II/III study of the drug in 276 subjects with EoE, treatment with lirentelimab resulted in histologic improvement (>85% in both treatment groups compared to 11% of placebo) but did not result in a significant change in the Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire, failing to meet its co-primary endpoints.(90)

Benralizumab

Benralizumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody specific for the IL-5 receptor α and is used in cases of severe asthma, particularly those with peripheral eosinophilia. Benralizumab induces ADCC via natural killer cells and IL-5 is critical for the development and maturation of eosinophils and therefore was studied in EoE most recently in the MESSINA phase III trial. The MESSINA study consisted of 210 patients aged 12-65 and did not meet the symptomatic component (dysphagia) of the dual-primary endpoints but did significantly reduce tissue eosinophilia.(91)

Mepolizumab and Reslizumab

Mepolizumab and reslizumab are monoclonal antibodies directed against IL-5, preventing binding of the cytokine to its receptor on eosinophils. Both therapies have been previously trialed in eosinophilic esophagitis. In trials of mepolizumab, esophageal eosinophil counts have significantly decreased, but symptomatic outcomes have been variable, with some studies reporting symptomatic improvement in only a minority of subjects despite consistent histologic improvement.(92, 93, 94) These studies have been limited by their employment of non-validated EoE symptom score metrics, and variable severity of enrolled patients compared with the recent successful dupilumab EoE study. A multi-center double-blind randomized clinical trial of mepolizumab 300 mg monthly vs mepolizumab 100 mg monthly vs placebo has recently been completed but results have not yet been reported (NCT03656380).

In a randomized trial of reslizumab in 227 children and adolescents with EoE, eosinophil counts were significantly reduced (though very few reached true histologic remission after 4 months of treatment), but symptom scores improved equally across all groups in the study.(95)

Omalizumab

Omalizumab, the monoclonal antibody against IgE, has also been trialed in eosinophilic esophagitis. In a small randomized controlled trial of omalizumab in 30 patients with EoE, there was no histologic or symptomatic improvement in treated subjects compared to placebo.(96)

Therapies on the horizon

Targeting type 2 inflammatory cytokines

As EoE is a type 2 allergic response, therapies continue to explore interventions in these pathways. Early data in monoclonal antibody targeting of IL-13 has been promising histologically where dectrekumab had improved esophageal eosinophilia but did not meet remission levels, whereas later cendakimab did meet histologic endpoint (97, 98). Upstream of IL-13 are epithelial alarmins such as thymic stromal lymphopoietin (TSLP), IL-33 and IL-25. Tezepelumab is a fully humanized monoclonal antibody targeting TSLP and gained FDA orphan drug status in 2021 and is actively recruiting for a phase 3 study in EoE.

Targeting cellular migration and immunomodulation

Vedolizumab is a humanized monoclonal antibody specific for the integrin α4β7, which many immune cells express and is specific for migration into the gastrointestinal tract. Blockade of this integrin is thought to impair trafficking of pathogenic cells to the gut. It is used primarily in Crohn’s disease and ulcerative colitis and has been described in case reports for use in eosinophilic gastrointestinal diseases (99, 100). Etrasimod is an oral small molecule that modulates the S1P receptor, impairing lymphocyte egress from lymph nodes and is in phase II in adults with EoE. Interestingly, this mechanism of action in recently gained FDA approval for ulcerative colitis for the medication Ozanimod. Lastly, a first-in-class peptide that was derived from a nature immunoregulatory protein in mycobacteria tuberculosis (mTB Chaperonin 60.1) recently completed enrollment for its phase II trials in EoE.(101) The chaperonin protein has been described to “reset” the immune system and formulations are being studied in both allergy and autoimmunity.

It should be noted that many biologic and small molecule trials are designed to evaluate therapies as monotherapy as opposed to add-on therapies, though many trials do permit the use of ongoing therapies that did not result in disease remission at the time of screening. These therapies are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1.

Biologics and EoE

| Name | Target | Study Population | Successful Primary Endpoints | Unsuccessful Primary Endpoints | Reported adverse effects |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Dupilumab (83) | IL-4Rα | 12y and up (321 subjects) Active EoE (>15 eos/hpf) on biopsy despite 8 weeks HD PPI DSQ 10+ |

Histologic remission (<=6 eos/hpf) at week 24 Change in DSQ from baseline at week 24* |

N/A | Injection site reaction, erythema, pain, or swelling Nasopharyngitis |

| Lirentelimab (88) | Siglec-8 | 12-80y (276 subjects) Active EoE (15 eos/hpf) on biopsy DSQ 12+ |

Histologic remission (<=6 eos/hpf) at week 24 | Change in DSQ from baseline at week 24 | Infusion-related reactions |

| Benralizumab (89) | IL-5Rα | 12-65y (210 subjects) Active EoE (15 eos/hpf) on biopsy Average of 2 days/week with daily DSQ 2+ |

Histologic remission (<=6 eos/hpf) at week 24 | Change in DSQ from baseline at week 24 | Results not yet formally published; safety and tolerability profile reportedly “consistent with known profile of the medicine” |

| Mepolizumab (92) | IL-5 | Largest trial enrolled 2-17y (59 subjects, no placebo) Active EoE (>20 eos/hpf) on biopsy Inadequate response or intolerance to prior therapy No symptom requirement |

Histologic remission (<5 eos/hpf) at week 12 | Secondary endpoint of change in frequency and severity of symptoms | Vomiting, diarrhea, upper abdominal pain |

| Reslizumab (93) | IL-5 | 5-18y (227 subjects) Active EoE (>24 eos/hpf) on biopsy 1 symptom of moderate severity or worse in week before randomization Continued symptoms despite 4 weeks PPI |

Percentage change in peak eosinophil count from baseline to week 15 (though most did not achieve remission) | Change in physician’s eosinophilic esophagitis global assessment score (evaluation of symptom severity) from baseline to week 15 | Headache, cough, mild infusion site reaction |

| Omalizumab (94) | IgE | 15y and up (30 subjects) Active EoE (>15 eos/hpf) on biopsy despite HD PPI |

-- | Reduction in esophageal eosinophils at week 16 | Not specifically reported |

| Dectrekumab (95) | IL-13 | 18-50y (25 subjects) Active EoE (>24 eos/hpf) despite 2 months of HD PPI and previous trial of elimination diet |

-- | Responder rate for >75% decrease in peak eosinophil counts at week 12 (mean decrease was 60%) Change in symptoms by MDQ (trend towards improvement but not adequately powered) |

Cough, reflux symptoms (not more common in active treatment group) |

| Cendakimab (96) | IL-13 | 18-65y (90 subjects) Active EoE (>15 eos/hpf) despite previous treatment with PPI Dysphagia symptoms for at least 4 days over 2 weeks |

Change in mean eosinophil count in 5 hpfs with highest eosinophil count | Secondary endpoint of change in dysphagia symptoms as assessed by DSD composite score and EEsAI PRO score (trend towards improvement in higher-dose treatment group) | Headache, upper respiratory tract infection, arthralgia (more common in higher-dose treatment group) |

only at the 300 mg weekly dosing frequency in adults | eos/hpf = eosinophils per high-power field; HD PPI = high-dose PPI; DSQ = Dysphagia Symptom Questionnaire; MDQ = Mayo Dysphagia questionnaire; DSD = dysphagia symptom diary; EEsAI PRO = eosinophilic esophagitis activity index patient-reported outcome

Knowledge Gaps

Despite the significant strides made in the last few years within the therapeutic world of EoE, knowledge gaps remain. A non-exhaustive list is provided here where further study would be particularly helpful.

Intentional exposures to allergens (“cheat days”) and the use of topical corticosteroids during this time.

Switching between therapies and timing surrounding this approach such as wash out time of one therapy to another.

Topical corticosteroid induction followed by alternative maintenance therapy such as PPI or diet elimination.

Timeline of return to disease after cessation of therapies beyond steroids.

Liberalizing diet once initiating dupilumab.

Laboratory monitoring on therapies, particularly dupilumab

Head-to-head quality of life comparisons of different first line therapies

Studies focused on pregnant patients with EoE.

Recommended Treatment Algorithm

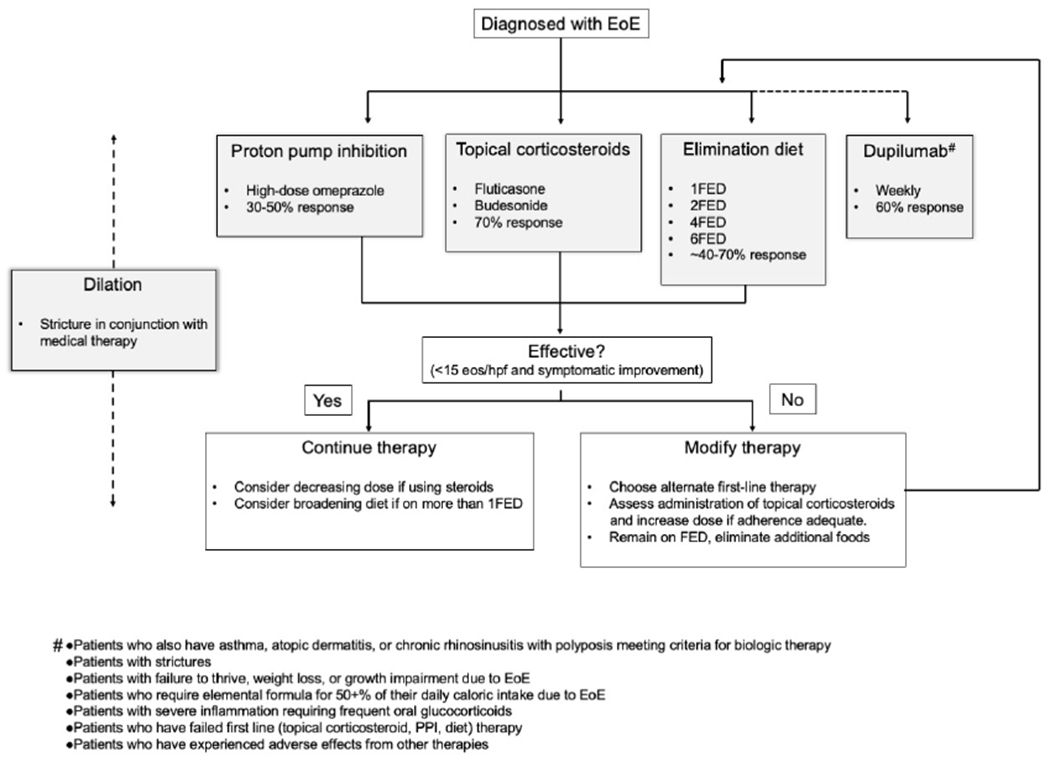

In a patient with newly-diagnosed eosinophilic esophagitis, we suggest that either PPI, topical corticosteroids, dietary therapy, or dupilumab could be used as first-line therapy (Figure 1). The decision to use one therapy over the other should be tailored to the individual patient, as there is currently not evidence to support one treatment over the others. Some patients may want to avoid the use of steroids or PPIs, while others may have difficulty restricting diet. In the case of dupilumab, cost is a consideration, given that therapy for EoE is likely to be lifelong and we do not have data regarding switching between therapies.

Figure 1.

Proposed treatment algorithm. *Dupilumab has been suggested for the following groups of patients87: Patients who also have asthma, atopic dermatitis, or chronic rhinosinusitis with polyposis meeting criteria for biologic therapy; Patients with strictures; Patients with failure to thrive, weight loss, or growth impairment due to EoE; Patients who require elemental formula for 50+% of their daily caloric intake due to EoE; Patients with severe inflammation requiring frequent oral glucocorticoids; Patients who have failed first line (topical corticosteroid, PPI, diet) therapy; Patients who have experienced adverse effects from other therapies, eos/hpf, Eosinophils per high-power field.

After initiating a therapy for EoE, we recommend endoscopic evaluation of response after 8-12 weeks of initiation of therapy. If the patient is in histologic remission (defined as <15 eos/hpf though increasingly providers consider lower thresholds such as <6 eos/hpf given that eosinophils are devoid in a healthy esophagus), we recommend continuing the currently effective therapy. If the patient is on topical corticosteroids, a dose reduction of 50% can be considered with follow-up evaluation to ensure continued response. If the patient is on dietary elimination of more than one food, reintroduction of one or more foods can be considered. We recommend reevaluation in 8-12 weeks after making these changes. If the patient continues to have active eosinophilic esophagitis, therapy should be modified. This could include increasing the dose of topical corticosteroids if an initial dose less than the maximum was selected, increasing the number of foods eliminated in an elimination diet, or switching to an alternate therapy for EoE. This can be repeated with reevaluation every 8-12 weeks until an effective therapy is determined. When patients become pregnant or are trying to become pregnant, discussion of risks and benefits of medications specific to pregnancy is an important consideration.

Funding:

This study was supported by Consortium of Eosinophilic Gastrointestinal Disease Researchers (CEGIR; U54 AI117804), which is part of the Rare Diseases Clinical Research Network (RDCRN), an initiative of the Office of Rare Diseases Research (ORDR), National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS), and is cofounded by the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases (NIAID), National Institute of Diabetes and Digestive and Kidney Diseases (NIDDK), and National Center for Advancing Translational Sciences (NCATS). CEGIR is also supported by patient advocacy groups including the American Partnership for Eosinophilic Disorders (APFED), Campaign Urging Research for Eosinophilic Disease (CURED), and Eosinophilic Family Coalition (EFC). CMB is additionally supported by T32-HL116275. MER is additionally supported by U19 AI070235, R01 AI045898, R01 AI148138, R01 AI124355, and R01 AI139126. GTF is supported by the LaCache Chair in GI and Allergic Diseases from Children’s Hospital Colorado.

COI:

A.M.U. is a medical advisor for Regeneron/Sanofi and AstraZeneca. C.M.B. has no conflicts of interest to disclose. M.E.R. is a consultant for Pulm One, Spoon Guru, ClostraBio, Serpin Pharm, Allakos, Celldex, Nextstone One, Bristol Myers Squibb, Astra Zeneca, Ellodi Pharma, GlaxoSmith Kline, Regeneron/Sanofi, Revolo Biotherapeutics, and Guidepoint and has an equity interest in the first seven listed, and royalties from reslizumab (Teva Pharmaceuticals), PEESSv2 (Mapi Research Trust) and UpToDate. M.E.R. is an inventor of patents owned by Cincinnati Children’s Hospital. G.T.F. is a consultant for Takeda, has received research support from Holoclara and Arena/Pfizer and is Chief Medical Officer of EnteroTrack. J.M.S. is a consultant for Allakos, ReadySetFood, Rengeneron/Sanofi, Allakos and ARS Pharmaceuticals. He has grant support from Regeneron/Sanofi, Bristol Myers Squibb, and Novartis.

Footnotes

Publisher's Disclaimer: This is a PDF file of an unedited manuscript that has been accepted for publication. As a service to our customers we are providing this early version of the manuscript. The manuscript will undergo copyediting, typesetting, and review of the resulting proof before it is published in its final form. Please note that during the production process errors may be discovered which could affect the content, and all legal disclaimers that apply to the journal pertain.

References:

- 1.Dellon ES, Liacouras CA, Molina-Infante J, Furuta GT, Spergel JM, Zevit N, et al. Updated International Consensus Diagnostic Criteria for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Proceedings of the AGREE Conference. Gastroenterology. 2018;155(4):1022–33 e10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Collins MH, Martin LJ, Alexander ES, Boyd JT, Sheridan R, He H, et al. Newly developed and validated eosinophilic esophagitis histology scoring system and evidence that it outperforms peak eosinophil count for disease diagnosis and monitoring. Dis Esophagus. 2017;30(3):1–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Furuta GT, Katzka DA. Eosinophilic Esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 2015;373(17):1640–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dellon ES, Kim HP, Sperry SL, Rybnicek DA, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ. A phenotypic analysis shows that eosinophilic esophagitis is a progressive fibrostenotic disease. Gastrointest Endosc. 2014;79(4):577–85 e4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aceves SS, Alexander JA, Baron TH, Bredenoord AJ, Day L, Dellon ES, et al. Endoscopic approach to eosinophilic esophagitis: American Society for Gastrointestinal Endoscopy Consensus Conference. Gastrointest Endosc. 2022;96(4):576–92 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hirano I, Moy N, Heckman MG, Thomas CS, Gonsalves N, Achem SR. Endoscopic assessment of the oesophageal features of eosinophilic oesophagitis: validation of a novel classification and grading system. Gut. 2013;62(4):489–95. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Peterson KA, Byrne KR, Vinson LA, Ying J, Boynton KK, Fang JC, et al. Elemental diet induces histologic response in adult eosinophilic esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(5):759–66. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Spergel JM. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults and children: evidence for a food allergy component in many patients. Curr Opin Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;7(3):274–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yan BM, Shaffer EA. Eosinophilic esophagitis: a newly established cause of dysphagia. World J Gastroenterol. 2006;12(15):2328–34. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Noti M, Wojno ED, Kim BS, Siracusa MC, Giacomin PR, Nair MG, et al. Thymic stromal lymphopoietin-elicited basophil responses promote eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat Med. 2013;19(8):1005–13. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Judd LM, Heine RG, Menheniott TR, Buzzelli J, O’Brien-Simpson N, Pavlic D, et al. Elevated IL-33 expression is associated with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis, and exogenous IL-33 promotes eosinophilic esophagitis development in mice. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2016;310(1):G13–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Travers J, Rochman M, Caldwell JM, Besse JA, Miracle CE, Rothenberg ME. IL-33 is induced in undifferentiated, non-dividing esophageal epithelial cells in eosinophilic esophagitis. Sci Rep. 2017;7(1):17563. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Rothenberg ME, Spergel JM, Sherrill JD, Annaiah K, Martin LJ, Cianferoni A, et al. Common variants at 5q22 associate with pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat Genet. 2010;42(4):289–91. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Blanchard C, Mingler MK, Vicario M, Abonia JP, Wu YY, Lu TX, et al. IL-13 involvement in eosinophilic esophagitis: transcriptome analysis and reversibility with glucocorticoids. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2007;120(6):1292–300. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Wu L, Oshima T, Li M, Tomita T, Fukui H, Watari J, et al. Filaggrin and tight junction proteins are crucial for IL-13-mediated esophageal barrier dysfunction. Am J Physiol Gastrointest Liver Physiol. 2018;315(3):G341–G50. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Uchida AM, Lenehan PJ, Vimalathas P, Miller KC, Valencia-Yang M, Qiang L, et al. Tissue eosinophils express the IL-33 receptor ST2 and type 2 cytokines in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Allergy. 2022;77(2):656–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Mulder DJ, Mak N, Hurlbut DJ, Justinich CJ. Atopic and non-atopic eosinophilic oesophagitis are distinguished by immunoglobulin E-bearing intraepithelial mast cells. Histopathology. 2012;61(5):810–22. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Morgan DM, Ruiter B, Smith NP, Tu AA, Monian B, Stone BE, et al. Clonally expanded, GPR15-expressing pathogenic effector T(H)2 cells are associated with eosinophilic esophagitis. Sci Immunol. 2021;6(62). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ben-Baruch Morgenstern N, Ballaban AY, Wen T, Shoda T, Caldwell JM, Kliewer K, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing of mast cells in eosinophilic esophagitis reveals heterogeneity, local proliferation, and activation that persists in remission. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;149(6):2062–77. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wen T, Aronow BJ, Rochman Y, Rochman M, Kc K, Dexheimer PJ, et al. Single-cell RNA sequencing identifies inflammatory tissue T cells in eosinophilic esophagitis. J Clin Invest. 2019;129(5):2014–28. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shoda T, Kaufman KM, Wen T, Caldwell JM, Osswald GA, Purnima P, et al. Desmoplakin and periplakin genetically and functionally contribute to eosinophilic esophagitis. Nat Commun. 2021;12(1):6795. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Underwood B, Troutman TD, Schwartz JT. Breaking down the complex pathophysiology of eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2023;130(1):28–39. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Hirano I, Chan ES, Rank MA, Sharaf RN, Stollman NH, Stukus DR, et al. AGA Institute and the Joint Task Force on Allergy-Immunology Practice Parameters Clinical Guidelines for the Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;158(6):1776–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Winter HS, Madara JL, Stafford RJ, Grand RJ, Quinlan JE, Goldman H. Intraepithelial eosinophils: a new diagnostic criterion for reflux esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 1982;83(4):818–23. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Nehra AK, Alexander JA, Loftus CG, Nehra V. Proton Pump Inhibitors: Review of Emerging Concerns. Mayo Clin Proc. 2018;93(2):240–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Jaynes M, Kumar AB. The risks of long-term use of proton pump inhibitors: a critical review. Ther Adv Drug Saf. 2019;10:2042098618809927. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Peterson KA, Yoshigi M, Hazel MW, Delker DA, Lin E, Krishnamurthy C, et al. RNA sequencing confirms similarities between PPI-responsive oesophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2018;48(2):219–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Dellon ES, Speck O, Woodward K, Gebhart JH, Madanick RD, Levinson S, et al. Clinical and endoscopic characteristics do not reliably differentiate PPI-responsive esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis in patients undergoing upper endoscopy: a prospective cohort study. Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(12):1854–60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Wen T, Dellon ES, Moawad FJ, Furuta GT, Aceves SS, Rothenberg ME. Transcriptome analysis of proton pump inhibitor-responsive esophageal eosinophilia reveals proton pump inhibitor-reversible allergic inflammation. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(1):187–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Odiase E, Zhang X, Chang Y, Nelson M, Balaji U, Gu J, et al. In Esophageal Squamous Cells From Eosinophilic Esophagitis Patients, Th2 Cytokines Increase Eotaxin-3 Secretion Through Effects on Intracellular Calcium and a Non-Gastric Proton Pump. Gastroenterology. 2021;160(6):2072–88 e6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Rochman M, Xie YM, Mack L, Caldwell JM, Klingler AM, Osswald GA, et al. Broad transcriptional response of the human esophageal epithelium to proton pump inhibitors. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2021;147(5):1924–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Thakkar KP, Fowler M, Keene S, Iuga A, Dellon ES. Long-term efficacy of proton pump inhibitors as a treatment modality for eosinophilic esophagitis. Dig Liver Dis. 2022;54(9):1179–85. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Visaggi P, Baiano Svizzero F, Del Corso G, Bellini M, Savarino E, de Bortoli N. Efficacy of a Second PPI Course After Steroid-Induced Remission in Eosinophilic Esophagitis Refractory to Initial PPI Therapy. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(10):1702–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Philpott H, Dellon ES. The role of maintenance therapy in eosinophilic esophagitis: who, why, and how? J Gastroenterol. 2018;53(2):165–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Burk CM, Long MD, Dellon ES. Management of Eosinophilic Esophagitis During Pregnancy. Dig Dis Sci. 2016;61(7):1819–25. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Choi A, Noh Y, Jeong HE, Choi EY, Man KKC, Han JY, et al. Association Between Proton Pump Inhibitor Use During Early Pregnancy and Risk of Congenital Malformations. JAMA Netw Open. 2023;6(1):e2250366. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Drugs and Lactation Database (LactMed®) [Internet]. Bethesda (MD): National Institute of Child Health and Human Development; 2006-. Available from: https://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK501922/. Accessed February 16, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Isaacs KL, Long MD. GI and liver disease during pregnancy: a practical approach. Thorofare (NJ): SLACK Incorporated; 2013. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Hirano I, Chan ES, Rank MA, Sharaf RN, Stollman NH, Stukus DR, et al. AGA institute and the joint task force on allergy-immunology practice parameters clinical guidelines for the management of eosinophilic esophagitis. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;124(5):416–23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Rank MA, Sharaf RN, Furuta GT, Aceves SS, Greenhawt M, Spergel JM, et al. Technical review on the management of eosinophilic esophagitis: a report from the AGA institute and the joint task force on allergy-immunology practice parameters. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2020;124(5):424–40 e17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Straumann A, Lucendo AJ, Miehlke S, Vieth M, Schlag C, Biedermann L, et al. Budesonide Orodispersible Tablets Maintain Remission in a Randomized, Placebo-Controlled Trial of Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2020;159(5):1672–85 e5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lucendo AJ, Miehlke S, Schlag C, Vieth M, von Arnim U, Molina-Infante J, et al. Efficacy of Budesonide Orodispersible Tablets as Induction Therapy for Eosinophilic Esophagitis in a Randomized Placebo-Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(1):74–86 e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Alexander JA, Jung KW, Arora AS, Enders F, Katzka DA, Kephardt GM, et al. Swallowed fluticasone improves histologic but not symptomatic response of adults with eosinophilic esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2012;10(7):742–9 e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Butz BK, Wen T, Gleich GJ, Furuta GT, Spergel J, King E, et al. Efficacy, dose reduction, and resistance to high-dose fluticasone in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(2):324–33 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Shoda T, Wen T, Aceves SS, Abonia JP, Atkins D, Bonis PA, et al. Eosinophilic oesophagitis endotype classification by molecular, clinical, and histopathological analyses: a cross-sectional study. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;3(7):477–88. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Wolf WA, Cotton CC, Green DJ, Hughes JT, Woosley JT, Shaheen NJ, et al. Predictors of response to steroid therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis and treatment of steroid-refractory patients. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015;13(3):452–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Eluri S, Selitsky SR, Perjar I, Hollyfield J, Betancourt R, Randall C, et al. Clinical and Molecular Factors Associated With Histologic Response to Topical Steroid Treatment in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(6):1081–8 e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Ketchem CJ, Ocampo AA, Xue Z, Chang NC, Thakkar KP, Reddy S, et al. Higher Body Mass Index Is Associated With Decreased Treatment Response to Topical Steroids in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Dellon ES, Woosley JT, Arrington A, McGee SJ, Covington J, Moist SE, et al. Efficacy of Budesonide vs Fluticasone for Initial Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in a Randomized Controlled Trial. Gastroenterology. 2019;157(1):65–73 e5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Liacouras CA, Furuta GT, Hirano I, Atkins D, Attwood SE, Bonis PA, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis: updated consensus recommendations for children and adults. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2011;128(1):3–20 e6; quiz 1-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Eluri S, Runge TM, Hansen J, Kochar B, Reed CC, Robey BS, et al. Diminishing Effectiveness of Long-Term Maintenance Topical Steroid Therapy in PPI Non-Responsive Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Transl Gastroenterol. 2017;8(6):e97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harel S, Hursh BE, Chan ES, Avinashi V, Panagiotopoulos C. Adrenal Suppression in Children Treated With Oral Viscous Budesonide for Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2015;61(2):190–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Golekoh MC, Hornung LN, Mukkada VA, Khoury JC, Putnam PE, Backeljauw PF. Adrenal Insufficiency after Chronic Swallowed Glucocorticoid Therapy for Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Pediatr. 2016;170:240–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bose P, Kumar S, Nebesio TD, Li C, Hon EC, Atkins D, et al. Adrenal Insufficiency in Children With Eosinophilic Esophagitis Treated With Topical Corticosteroids. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2020;70(3):324–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Nistel M, Furuta GT, Pan Z, Hsu S. Impact of Dose Reduction of Topical Steroids to Manage Adrenal Insufficiency in Pediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Pediatr Gastroenterol Nutr. 2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Schaefer ET, Fitzgerald JF, Molleston JP, Croffie JM, Pfefferkorn MD, Corkins MR, et al. Comparison of oral prednisone and topical fluticasone in the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis: a randomized trial in children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2008;6(2):165–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Dellon ES, Gonsalves N, Hirano I, Furuta GT, Liacouras CA, Katzka DA, et al. ACG clinical guideline: Evidenced based approach to the diagnosis and management of esophageal eosinophilia and eosinophilic esophagitis (EoE). Am J Gastroenterol. 2013;108(5):679–92; quiz 93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Dellon ES, Katzka DA, Collins MH, Gupta SK, Lan L, Williams J, et al. Safety and Efficacy of Budesonide Oral Suspension Maintenance Therapy in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2019;17(4):666–73 e8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59.Andreae DA, Hanna MG, Magid MS, Malerba S, Andreae MH, Bagiella E, et al. Swallowed Fluticasone Propionate Is an Effective Long-Term Maintenance Therapy for Children With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2016;111(8):1187–97. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.National Asthma Education and Prevention Program, Third Expert Panel on the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Expert Panel Report 3: Guidelines for the Diagnosis and Management of Asthma. Bethesda (MD): National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute (US). 2007. [Google Scholar]

- 61.Dellon ES, Lucendo AJ, Schlag C, Schoepfer AM, Falk GW, Eagle G, et al. Fluticasone Propionate Orally Disintegrating Tablet (APT-1011) for Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Randomized Controlled Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(11):2485–94 e15. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Hirano I, Collins MH, Katzka DA, Mukkada VA, Falk GW, Morey R, et al. Budesonide Oral Suspension Improves Outcomes in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis: Results from a Phase 3 Trial. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(3):525–34 e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Netzer P, Gschossmann JM, Straumann A, Sendensky A, Weimann R, Schoepfer AM. Corticosteroid-dependent eosinophilic oesophagitis: azathioprine and 6-mercaptopurine can induce and maintain long-term remission. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2007;19(10):865–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Ruffner MA, Hu A, Dilollo J, Benocek K, Shows D, Gluck M, et al. Conserved IFN Signature between Adult and Pediatric Eosinophilic Esophagitis. J Immunol. 2021;206(6):1361–71. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Pyne AL, Hazel MW, Uchida AM, Qeadan F, Jordan KC, Holman A, et al. Oesophageal secretions reveal local food-specific antibody responses in eosinophilic oesophagitis. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2022;56(9):1328–36. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Arias A, Gonzalez-Cervera J, Tenias JM, Lucendo AJ. Efficacy of dietary interventions for inducing histologic remission in patients with eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Gastroenterology. 2014;146(7):1639–48. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Zalewski A, Doerfler B, Krause A, Hirano I, Gonsalves N. Long-Term Outcomes of the Six-Food Elimination Diet and Food Reintroduction in a Large Cohort of Adults With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(12):1963–70. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Gonsalves N, Yang GY, Doerfler B, Ritz S, Ditto AM, Hirano I. Elimination diet effectively treats eosinophilic esophagitis in adults; food reintroduction identifies causative factors. Gastroenterology. 2012;142(7):1451–9 e1; quiz e14-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Lucendo AJ, Arias A, Gonzalez-Cervera J, Yague-Compadre JL, Guagnozzi D, Angueira T, et al. Empiric 6-food elimination diet induced and maintained prolonged remission in patients with adult eosinophilic esophagitis: a prospective study on the food cause of the disease. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2013;131(3):797–804. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Kelly KJ, Lazenby AJ, Rowe PC, Yardley JH, Perman JA, Sampson HA. Eosinophilic esophagitis attributed to gastroesophageal reflux: improvement with an amino acid-based formula. Gastroenterology. 1995;109(5):1503–12. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Henderson CJ, Abonia JP, King EC, Putnam PE, Collins MH, Franciosi JP, et al. Comparative dietary therapy effectiveness in remission of pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(6):1570–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Warners MJ, Vlieg-Boerstra BJ, Verheij J, van Rhijn BD, Van Ampting MT, Harthoorn LF, et al. Elemental diet decreases inflammation and improves symptoms in adult eosinophilic oesophagitis patients. Aliment Pharmacol Ther. 2017;45(6):777–87. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Molina-Infante J, Arias A, Alcedo J, Garcia-Romero R, Casabona-Frances S, Prieto-Garcia A, et al. Step-up empiric elimination diet for pediatric and adult eosinophilic esophagitis: The 2–4-6 study. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2018;141(4):1365–72. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Wechsler JB, Schwartz S, Arva NC, Kim KA, Chen L, Makhija M, et al. A Single-Food Milk Elimination Diet Is Effective for Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis in Children. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2022;20(8):1748–56 e11. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Kara Kliewer SSA, Dan Atkins, Bonis Peter A., Mirna Chehade, Collins Margaret H., Dellon Evan S., Lin Fei, Gupta Sandeep K., Kagalwalla Amir F., Sabina Mir, Mukkada Vincent A., Robbie Pesek, Jonathan Spergel, Guang-Yu Yang, Rothenberg Marc E.. Efficacy of 1-food and 4-food elimination diets for pediatric eosinophilic esophagitis in a randomized multisite study. Gastroenterology. 2019. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Kara L Kliewer NG, Dellon Evan S, Katzka David A, Abonia Juan P, Aceves Seema S, Arva Nicoleta C, Besse John A, Bonis Peter A, Caldwell Julie M, Capocelli Kelley E, Mirna Chehade, Antonella Cianferoni, Collins Margaret H, Falk Gary W, Gupta Sandeep K, Ikuo Hirano, Krischer Jeffrey P, John Leung, Martin Lisa J, Paul Menard-Katcher, Mukkada Vincent A, Peterson Kathryn A, Tetsuo Shoda, Rudman Spergel Amanda K, Spergel Jonathan M, Guang-Yu Yang, Xue Zhang, Furuta Glenn T, Rothenberg Marc E. One Food versus Six Food Elimination Diet Therapy for Treatment of Eosinophilic Esophagitis: A Multicenter Randomized Clinical Trial. Lancet Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023;In Press. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Chang JW, Kliewer K, Katzka DA, Peterson KA, Gonsalves N, Gupta SK, et al. Provider Beliefs, Practices, and Perceived Barriers to Dietary Elimination Therapy in Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Am J Gastroenterol. 2022;117(12):2071–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Mayerhofer C, Kavallar AM, Aldrian D, Lindner AK, Muller T, Vogel GF. Efficacy of elimination diets in eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2023. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Kramer MS, Kakuma R. Maternal dietary antigen avoidance during pregnancy or lactation, or both, for preventing or treating atopic disease in the child. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2012;2012(9):CD000133. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 80.Petroni D, Spergel JM. Eosinophilic esophagitis and symptoms possibly related to eosinophilic esophagitis in oral immunotherapy. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2018;120(3):237–40 e4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Dellon ES, Speck O, Woodward K, Covey S, Rusin S, Shaheen NJ, et al. Distribution and variability of esophageal eosinophilia in patients undergoing upper endoscopy. Mod Pathol. 2015;28(3):383–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Dougherty M, Runge TM, Eluri S, Dellon ES. Esophageal dilation with either bougie or balloon technique as a treatment for eosinophilic esophagitis: a systematic review and metaanalysis. Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;86(4):581–91 e3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Rothenberg ME. Scientific journey to the first FDA-approved drug for eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2022;150(6):1325–32. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Spergel BL, Ruffner MA, Godwin BC, Liacouras CA, Cianferoni A, Gober L, et al. Improvement in eosinophilic esophagitis when using dupilumab for other indications or compassionate use. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022;128(5):589–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Dellon ES, Rothenberg ME, Collins MH, Hirano I, Chehade M, Bredenoord AJ, et al. Dupilumab in Adults and Adolescents with Eosinophilic Esophagitis. N Engl J Med. 2022;387(25):2317–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Press Release: Dupixent® (dupilumab) Phase 3 trial shows positive results in children 1 to 11 years of age with eosinophilic esophagitis. 2022. Available at:https://www.sanofi.com/en/media-room/press-releases/2022/2022-07-14-05-00-00-2479427. Accessed February 16, 2023.

- 87.Aceves SS, Dellon ES, Greenhawt M, Hirano I, Liacouras CA, Spergel JM. Clinical guidance for the use of dupilumab in eosinophilic esophagitis: A yardstick. Ann Allergy Asthma Immunol. 2022. Dec 13;S1081-1206(22)01997-4. [E-pub ahead of print] [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Korver W, Wong A, Gebremeskel S, Negri GL, Schanin J, Chang K, et al. The Inhibitory Receptor Siglec-8 Interacts With FcepsilonRI and Globally Inhibits Intracellular Signaling in Primary Mast Cells Upon Activation. Front Immunol. 2022;13:833728. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Youngblood BA, Brock EC, Leung J, Falahati R, Bryce PJ, Bright J, et al. AK002, a Humanized Sialic Acid-Binding Immunoglobulin-Like Lectin-8 Antibody that Induces Antibody-Dependent Cell-Mediated Cytotoxicity against Human Eosinophils and Inhibits Mast Cell-Mediated Anaphylaxis in Mice. Int Arch Allergy Immunol. 2019;180(2):91–102. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Dellon EC, Mirna Genta, Robert M; Leiman David A.; Peterson Kathryn A.; Spergel Jonathan; Wechsler Joshua; Bortey Enoch; Chang Alan T.; Hirano Ikuo. Results from KRYPTOS, a Phase 2/3 Study of Lirentelimab (AK002) in Adults and Adolescents With EoE. American Journal of Gastroenterology. 2022;117(10S):e316–e317. [Google Scholar]

- 91.Update on the MESSINA Phase III trial for Fasenra in eosinophilic esophagitis. 2022. Available from: https://www.astrazeneca.com/media-centre/press-releases/2022/update-on-messina-phase-iii-trial.html. Accessed February 16, 2023.

- 92.Stein ML, Collins MH, Villanueva JM, Kushner JP, Putnam PE, Buckmeier BK, et al. Anti-IL-5 (mepolizumab) therapy for eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2006;118(6):1312–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Straumann A, Conus S, Grzonka P, Kita H, Kephart G, Bussmann C, et al. Anti-interleukin-5 antibody treatment (mepolizumab) in active eosinophilic oesophagitis: a randomised, placebo-controlled, double-blind trial. Gut. 2010;59(1):21–30. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Assa’ad AH, Gupta SK, Collins MH, Thomson M, Heath AT, Smith DA, et al. An antibody against IL-5 reduces numbers of esophageal intraepithelial eosinophils in children with eosinophilic esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2011;141(5):1593–604. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.JM Spergel, Rothenberg ME Collins MH, Furuta GT Markowitz JE, Fuchs G 3rd, et al. Reslizumab in children and adolescents with eosinophilic esophagitis: results of a double-blind, randomized, placebo-controlled trial. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2012;129(2):456–63, 63 e1-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Clayton F, Fang JC, Gleich GJ, Lucendo AJ, Olalla JM, Vinson LA, et al. Eosinophilic esophagitis in adults is associated with IgG4 and not mediated by IgE. Gastroenterology. 2014;147(3):602–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Rothenberg ME, Wen T, Greenberg A, Alpan O, Enav B, Hirano I, et al. Intravenous anti-IL-13 mAb QAX576 for the treatment of eosinophilic esophagitis. J Allergy Clin Immunol. 2015;135(2):500–7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Hirano I, Collins MH, Assouline-Dayan Y, Evans L, Gupta S, Schoepfer AM, et al. RPC4046, a Monoclonal Antibody Against IL13, Reduces Histologic and Endoscopic Activity in Patients With Eosinophilic Esophagitis. Gastroenterology. 2019;156(3):592–603 e10. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Nhu QM, Chiao H, Moawad FJ, Bao F, Konijeti GG. The Anti-alpha4beta7 Integrin Therapeutic Antibody for Inflammatory Bowel Disease, Vedolizumab, Ameliorates Eosinophilic Esophagitis: a Novel Clinical Observation. Am J Gastroenterol. 2018;113(8): 1261–3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Taft TH, Mutlu EA. The Potential Role of Vedolizumab in Concomitant Eosinophilic Esophagitis and Crohn’s Disease. Clin Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018;16(11):1840–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Revolo Biotherapeutics Completes Enrollment in Phase 2 Trial of ‘1104 in Allergic Disease. 2023. Available from: https://revolobio.com/2023/01/05/revolo-biotherapeutics-completes-enrollment-in-phase-2-trial-of-1104-in-allergic-disease/ Accessed February 16, 2023. [Google Scholar]