Abstract

The optimal duration of lenalidomide (Len) maintenance for patients with multiple myeloma (MM) after autologous stem cell transplantation (autoHCT) is unknown. We conducted a retrospective single-center analysis of adult MM patients that received upfront autoHCT between 2005-2021, followed by single-agent Len maintenance. 1167 patients were included with a median age of 61.4 (range 25.4-82.3) years, and high-risk chromosomal abnormalities in 19%. Median duration of maintenance was 22.3 (range 0.03-139.6) months. After a median follow-up of 47.9 (range 2.9 – 171.7) months, median PFS and OS for the entire cohort were 56.6 (95% CI 48.2 – 61.4) months and 111.3 (95% CI 101.7 – 121.5) months, respectively. In MVA, high-risk cytogenetics was associated with a worse PFS (HR 1.91) and OS (HR 1.73) (p<0.001 for both). Use of KRD induction and achievement of MRD-negative ≥ VGPR before autoHCT were associated with an improved PFS (HR 0.53 and HR 0.57, respectively; p<0.001 for both]. Longer maintenance duration, even with a 5-year cutoff, was associated with superior PFS and OS (HR 0.17 and 0.12, respectively; p<0.001 for both). 106 patients (9%) developed a second primary malignancy (SPM), mostly solid tumors (39%) and myeloid malignancies (30%). Longer maintenance duration was associated with a higher risk of SPM, reaching statistical significance after >2 years (odds ratio 2.25; p<0.001). In conclusion, outcomes with Len maintenance were comparable to those reported in large clinical trials. Longer duration of maintenance, even beyond 5 years, was associated with improved survival.

Keywords: Maintenance, Lenalidomide, multiple myeloma

Introduction

High-dose chemotherapy followed by autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (autoHCT) is considered standard of care for patients with multiple myeloma (MM) [1]. However, most patients eventually relapse after autoHCT. Use of the immunomodulatory drug, lenalidomide (Len), as post-transplant maintenance has shown improved outcomes in randomized clinical trials. A meta-analysis of CALGB, GIMEMA, and IFM placebo-controlled trials demonstrated improved progression-free survival (PFS) and overall survival (OS) with Len maintenance (hazard ratio (HR) 0.48 and 0.75, respectively) [2]. However, there was no OS benefit in International Staging System (ISS) stage III and high-risk MM (HRMM) patients. A subset of the Myeloma XI trial compared Len maintenance (n=730) with observation only (n=518) in transplant-eligible patients. The Len maintenance group had better median PFS (57 months vs. 30 months) and 3-year OS (87.5% vs. 80.2%) [3]. A retrospective analysis of 432 patients from The Connect MM Registry showed survival benefit with Len maintenance in the real-world setting. Patients who received Len maintenance after autoHCT had a better 3-year PFS (56% vs. 42%) and OS (85% vs. 70%) compared to patients who did not receive maintenance [4].

Based on these data, single-agent Len has been adopted as the preferred post-autoHCT maintenance regimen [1]. Recently, several groups have attempted to define the optimal duration of Len maintenance. Several analyses, including those from the Myeloma XI and STAMINA trials [5, 6], as well as several relatively small retrospective reports [7, 8], have shown continued benefit with longer duration of post-transplant Len maintenance, for up to 4 years post-autoHCT.

One concern with long-term use of Len is a potential increase in the risk of second primary malignancies (SPMs). In the phase III trial by Attal et al. the incidence of SPMs was significantly higher in the Len maintenance group, compared to the placebo group (3.1/100 patient years vs. 1.2/100 patient years, respectively; p=0.002) [9]. Several meta-analyses have since confirmed the elevated risk of SPM in patients with MM receiving Len maintenance in the post-transplant setting [2, 10].

In the current study, we describe real-world data in terms of clinical characteristics and outcomes of a large group of patients with newly-diagnosed MM who underwent upfront autoHCT and received single-agent Len maintenance with a long follow-up period. We also evaluated the impact of the duration of Len maintenance on survival outcomes and the incidence of SPM.

Materials and Methods

Study design and participants

We conducted a retrospective, single-center, chart review study of patients with newly diagnosed MM who received autoHCT between January 2005 and December 2021, followed by single-agent Len maintenance therapy. Data was retrieved from our institution’s computerized database, as well as from chart-based review. Primary endpoints were PFS and OS; secondary endpoints included hematological response and minimal residual disease (MRD) status at day 100 after autoHCT and best response after autoHCT, as well as incidence of SPM. The study was conducted following approval by our institutional review board (IRB) at The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center, and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act (HIPAA).

Response definitions and MRD evaluation

We used the International Myeloma Working Group (IMWG) criteria to evaluate response and progression [11]. Hematological responses were categorized as complete response (CR), stringent CR (sCR), very good partial response (VGPR), partial response (PR), stable disease (SD), or progressive disease (PD). MRD status was assessed using 8-color next-generation flow cytometry (NGF), with a sensitivity of 1/10-5 cells (0.001%) and a required analysis of at least 2 million events.

Fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH) analysis

We used FISH analysis to detect high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities, including translocation (t) (4;14), t(14;16), deletion (del) (17p), as well as additional copies of 1q21. The FISH probes used were: IGH::FGFR3 dual-color dual-fusion probes; IGH::MAF dual-color dual-fusion probes; TP53/CEP17 dual-color and CDKN2C/CKS1B dual-color probes. Presence of 3 copies of CKS1B was defined as 1q21 gain, whereas 1q21 amplification was defined as having ≥4 copies of CKS1B. Plasma cell enrichment was not routinely performed during this study period. Cut-off values established by our clinical cytogenetics laboratory were: 7.9% for 1q21 gain, 0% for 1q21 amplification, 4.7% for deletion of TP53, 0.4% for t(4;14), and 0% for t(14;16).

Statistical methods

PFS time was computed from maintenance start date to one of the following dates: day of disease progression (or) death, if died without disease progression (or) last follow-up date. Patients who were alive at their last follow-up without evidence of progression were censored. OS time was computed from maintenance start date to date of death or the last known date they were alive. Patients alive at their last follow-up date were censored. The Kaplan-Meier method was used to estimate PFS and OS, and differences between groups were evaluated by the log-rank test. In addition, Cox proportional hazards regression models were implemented to determine associations between PFS and OS and measures of interest. Measures that occurred after maintenance start date, including post-maintenance hematological response and MRD assessments, were included as time-dependent covariates in the regression models. For the association between duration of maintenance and survival outcomes, the start time used was the date of autoHCT, and duration of maintenance was included in the models as a time-dependent covariate. Association between duration of maintenance and incidence of SPM was evaluated using logistic regression model.

SAS 9.4 for Windows (Copyright © 2002-2012 by SAS Institute Inc., Cary, NC) was used to perform all statistical analyses. A significance level of 5% was used for all statistical tests. No adjustments for multiple testing were made.

Results

Patient and disease characteristics

Overall, 1167 patients were included in the analysis. Median age was 61.4 (range 25.4-82.3) years, and 57% were male. A majority of patients had R-ISS stage of I (28%) or II (37%), and 19% (n=222) had high-risk chromosomal abnormalities. The most common pre-transplant induction regimens used were bortezomib, Len and dexamethasone (VRD) (38%) or carfilzomib, Len and dexamethasone (KRD) (19%). Most patients received melphalan as conditioning for the autoHCT (85%, n=993). Patient characteristics are summarized in Table 1.

Table 1:

Baseline Clinical and Treatment Characteristics.

| Parameter | All (N=1167) n (%) |

|---|---|

| Gender | |

| Male | 660 (57) |

| Female | 507 (43) |

| Age at autoHCT (years) | |

| Median (Range) | 61.4 (25.4-82.3) |

| Age at autoHCT | |

| ≤ 70 years | 1021 (87) |

| > 70 years | 146 (13) |

| Race | |

| Black | 234 (20) |

| Non-black | 919 (79) |

| Unknown | 14 (1) |

| Light chain type | |

| Kappa | 766 (66) |

| Lambda | 391 (34) |

| Biclonal | 3 (<1) |

| Unknown | 7 (1) |

| High-risk chromosomal abnormality ¥ | |

| No | 880 (75) |

| Yes | 222 (19) |

| Unknown | 65 (6) |

| R-ISS | |

| I | 331 (28) |

| II | 427 (37) |

| III | 58 (5) |

| Unknown | 351 (30) |

| Bone lesions | |

| None | 214 (18) |

| 1 to 3 | 464 (40) |

| > 3 | 468 (40) |

| Unknown | 21 (2) |

| Induction treatment | |

| VRD | 441 (38) |

| VCD | 160 (14) |

| KRD | 219 (19) |

| VD | 151 (13) |

| ImiD+Dexa | 83 (7) |

| Other | 113 (10) |

| HCT-CI | |

| Median (Range) | 2 (0.0 - 14.0) |

| HCT-CI | |

| ≤ 3 | 897 (77) |

| > 3 | 268 (23) |

| Unknown | 2 (<1) |

| Conditioning regimen | |

| Mel | 993 (85) |

| BuMel based | 125 (11) |

| Mel based (other) | 28 (2) |

| Evomela | 21 (2) |

| Response prior to autoHCT | |

| sCR/CR | 165 (14) |

| VGPR | 531 (46) |

| PR | 449 (38) |

| SD | 22 (2) |

| MRD status prior to autoHCT | |

| Negative | 391 (34) |

| Positive | 505 (43) |

| NA | 271 (23) |

| History of second malignancy before autoHCT | |

| No | 1023 (88) |

| Yes | 141 (12) |

autoHCT=Autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant, HCT-CI=Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation-specific Comorbidity Index, R-ISS=Revised multiple myeloma international staging system, VRD= Bortezomib /lenalidomide /dexamethasone, VCD=Bortezomib /cyclophosphamide/dexamethasone, KRD= Carfilzomib/lenalidomide/dexamethasone, VD=Bortezomib/dexamethasone, ImiD=Immunomodulatory drugs, Mel=Melphalan, BuMel=Busulfan/Melphalan, sCR=Stringent complete response, CR=Complete response, nCR=Near complete response, VGPR=very good partial response, PR=Partial response, SD=Stable disease, Dexa=dexamethasone, MRD=Minimal residual disease, NA=not available.

Defined as del17p, t(4;14), t(14;16) or 1q21 gain or amplification by fluorescence in situ hybridization (FISH).

Len maintenance

Patients started Len maintenance a median of 112 (range 30-365) days after autoHCT. Median duration of maintenance was 22.3 (range 0.03-139.6) months. Four hundred and seventy patients (40%) continued maintenance until the last follow-up or death (without progression). Of the 697 patients (60%) who discontinued Len maintenance, disease progression was the leading cause of cessation (60%, n=416), followed by Len toxicity (20%, n=136) (Supplementary Table 1).

Responses and MRD outcomes

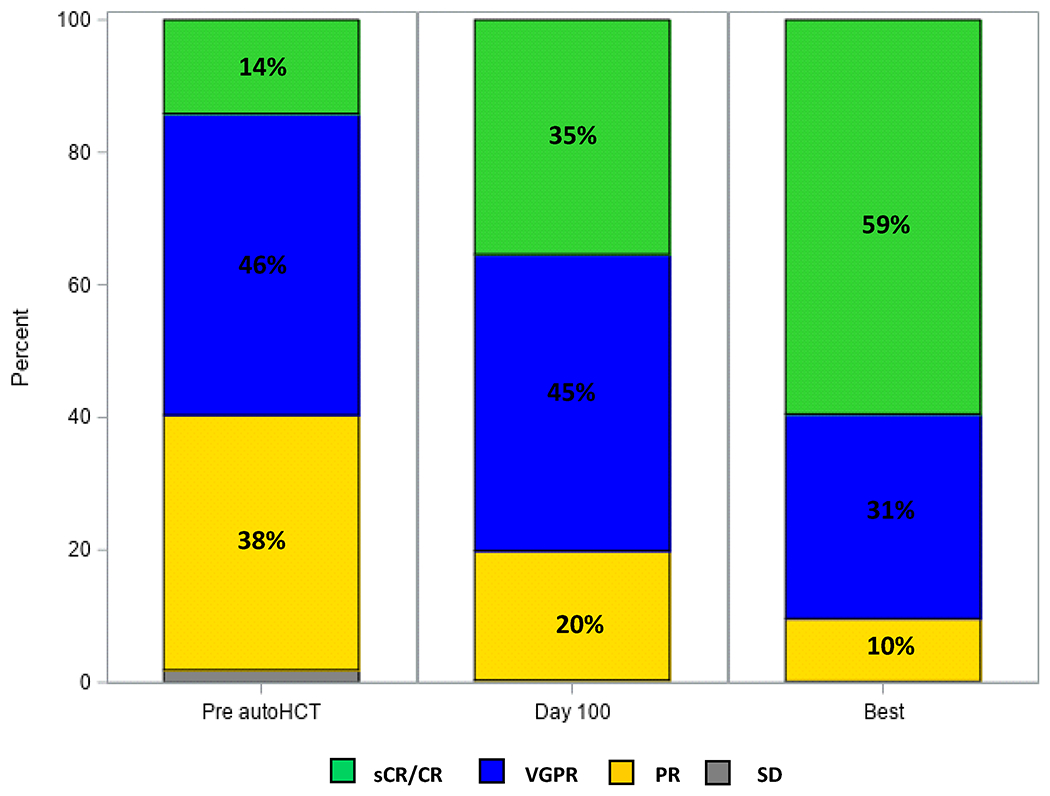

After completing induction therapy prior to autoHCT, 165 (14%) and 696 (60%) patients achieved ≥ CR and ≥ VGPR, respectively, and 334 (29%) achieved MRD-negative ≥ VGPR. Eighty percent and 90% of patients had ≥VGPR at day 100 and at best response post-autoHCT, respectively. Fifty percent (n=178) and 64% (n=230) of evaluable patients had MRD-negative ≥VGPR at day 100 and at best response after autoHCT, respectively. Pre- and post-transplant responses are depicted in Figure 1.

Figure 1.

Hematological responses, entire cohort (N=1167): prior to autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation (autoHCT), at day 100 after autoHCT and at best post-transplant response.

Survival outcomes

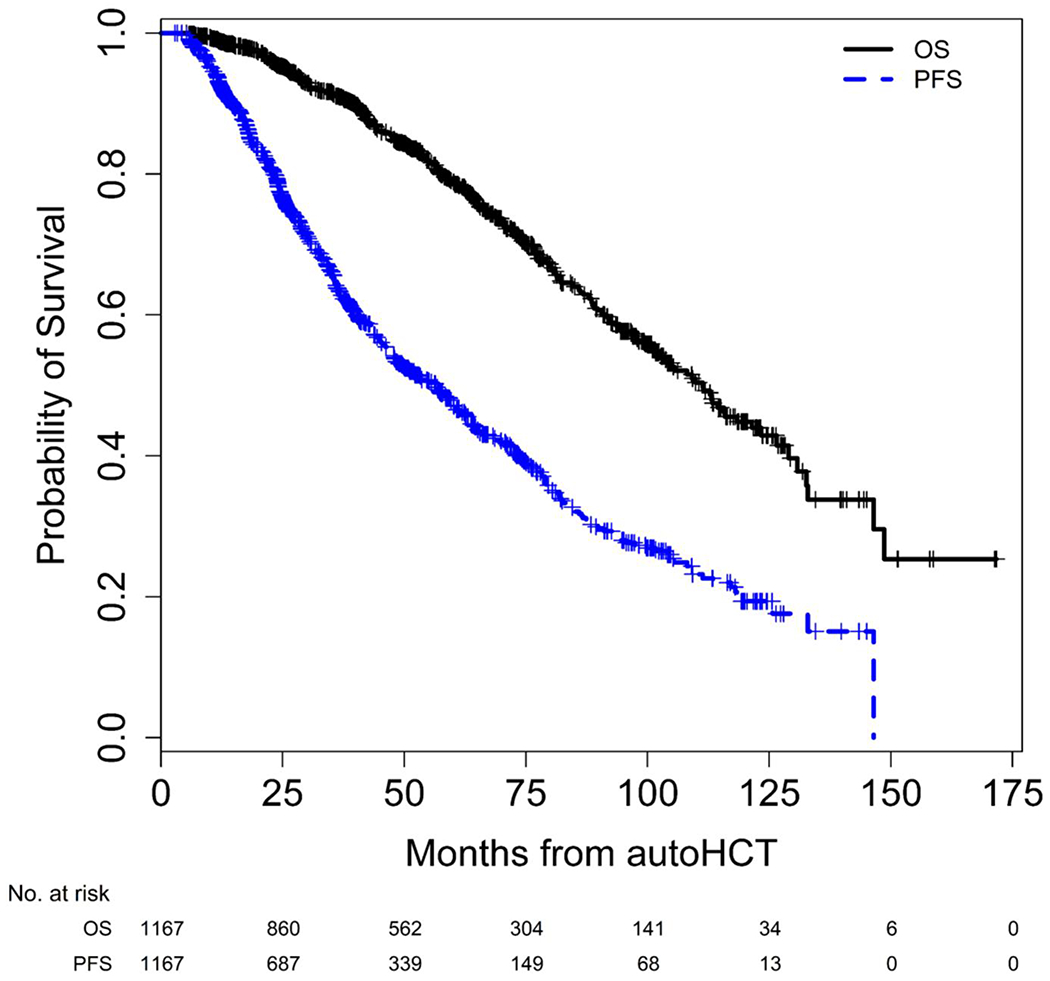

With a median follow-up of 47.9 (range 2.9 – 171.7) months from autoHCT and 43.6 (range 0.0-168.1) months from start of maintenance for the entire cohort, the median (95% CI) PFS and OS from autoHCT were 56.6 (48.2 – 61.4) months and 111.3 (101.7 – 121.5) months, respectively (Figure 2). Median PFS from start of maintenance was 29.6 (24.1 – 35.5) months for patients with HRMM, and 57.3 (50.3 – 65.6) months for standard risk MM (SRMM) patients. Median OS from start of maintenance was 84.8 (61.1 – not reached) months for patients with HRMM, and 110.1 (102.7 – 125.5) months for those with SRMM.

Figure 2.

Progression free survival and overall survival, entire cohort.

Use of KRD induction and achievement of MRD-negative ≥VGPR prior to autoHCT were associated with improved PFS in both univariate analysis (UVA) and multivariable analysis (MVA) [in MVA: (hazard ratio [95% CI]; 0.53 [0.38 – 0.74]) and (0.57 [0.45 – 0.71), respectively; p<0.001 for both]. MRD-negative ≥VGPR at best response after autoHCT was also associated with improved PFS in both UVA and MVA (in MVA: 0.68 [0.52 – 0.90; p=0.006).

As expected, patients who stopped maintenance due to progressive disease had inferior PFS and OS compared to those who stopped due to Len toxicity [(2.92 [2.26 – 3.77]) and (1.95 [1.37 – 2.77]), respectively; p<0.001 for both] in UVA. In UVA of the patients who stopped Len maintenance due to toxicity, those who stopped maintenance due to skin rash had inferior PFS than patients who stopped maintenance due to other toxicities (2.09 [1.09 – 3.99]; p=0.026). This significance was not maintained in MVA (p=0.98), and there was no significant impact on OS in UVA (p=0.40). Conversely, patients who stopped maintenance due to fatigue had superior OS, in both UVA and MVA (0.09 [0.01 – 0.68; p=0.019), without a significant impact on PFS (p=0.26). HCT-CI score >3 was associated with inferior OS in both UVA and MVA (1.85 [1.39 – 2.45]; p<0.001).

High-risk cytogenetics was associated with inferior PFS and OS in both UVA and MVA [in MVA: (2.03 [1.63 – 2.54]) for PFS and (1.77 [1.30 – 2.41]) for OS; p<0.001 for both]. Longer duration of maintenance was associated with better PFS and OS with duration cutoffs of 2-5 years: maintenance for >2 years was associated with (0.23 [0.19 – 0.27]) for PFS and (0.25 [0.19 – 0.32]) for OS; maintenance for >3 years was associated with (0.21 [0.17 – 0.26]) for PFS and (0.19 [0.14 – 0.26]) for OS; maintenance for >4 years was associated with (0.19 [0.15 – 0.24]) for PFS and (0.15 [0.10 – 0.22]) for OS; maintenance for >5 years was associated with (0.17 [0.13 – 0.23) for PFS and (0.12 [0.07 – 0.20]) for OS, p<0.001 for all, in UVA. In MVA, duration of maintenance longer than three years was associated with better PFS (0.20 [0.16 – 0.24]; p<0.001) and OS (0.19 [0.14 – 0.26]; p<0.001). Detailed MVA for both PFS and OS are presented in Table 2a and 2b, respectively. Multivariable results for maintenance duration by risk group are provided in Supplementary Table 2.

Table 2a.

Multivariable Analysis for Progression-Free Survival

| Measure | Progression-Free Survival | |

|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Cytogenetic risk | ||

| High vs. Standard | 2.03 (1.63, 2.54) | <0.001 |

| R-ISS | ||

| II vs. I | 1.05 (0.84, 1.32) | 0.66 |

| III vs. I | 1.72 (1.16, 2.56) | 0.007 |

| Induction regimen | ||

| KRD vs. Other | 0.53 (0.38, 0.74) | <0.001 |

| [MRD Negative ≥VGPR] at autoHCT | ||

| Yes vs. No | 0.57 (0.45, 0.71) | <0.001 |

| [MRD Negative ≥VGPR] best reponse a | ||

| Yes vs. No | 0.68 (0.52, 0.90) | 0.006 |

| Maintenance duration a | ||

| >3 years vs. ≤3 years | 0.20 (0.16, 0.24) | <0.001 |

| Reason for maintenance d/c a | ||

| Rash vs. Other | 0.99 (0.54, 1.81) | 0.98 |

Table 2b.

Multivariable Analysis for Overall Survival

| Measure | Overall Survival | |

|---|---|---|

| Hazard Ratio (95% CI) | p-Value | |

| Age at autoHCT (years) | ||

| >70 vs. ≤70 | 1.17 (0.84, 1.63) | 0.34 |

| Cytogenetic risk | ||

| High vs. Standard | 1.77 (1.30, 2.41) | <0.001 |

| R-ISS | ||

| II vs. I | 1.31 (0.93, 1.85) | 0.13 |

| III vs. I | 2.73 (1.62, 4.58) | <0.001 |

| HCT-CI Score | ||

| > 3 vs. ≤ 3 | 1.85 (1.39, 2.45) | <0.001 |

| Maintenance duration a | ||

| >3 years vs. ≤3 years | 0.19 (0.14, 0.26) | <0.001 |

| Reason for maintenance d/c a | ||

| Fatigue vs. Other | 0.09 (0.01, 0.68) | 0.019 |

Abbreviations: CI=Confidence interval, ref=Reference, AutoHCT=Autologous stem cell transplant, R-ISS= Revised International multiple myeloma staging system, KRD= Carfilzomib/Revlimid/dexamethasone, HCT-CI=Hematopoietic Cell Transplantation-specific Comorbidity Index, MRD=Minimal residual disease, VGPR=Very good partial response, CR=Complete response, d/c=discontinuation.

Included in the model as a time-dependent covariate

SPM

Overall, 106 (9%) patients developed an SPM at a median of 40.2 (range 1.8 – 141.6) months from the start of maintenance, and 43.4 (range 2.9 – 145.2) months from autoHCT (Supplementary Figure 1, Supplementary Table 3). The median number of days from autoHCT to start of maintenance was 118 (range, 68-305) days for patients who developed SPM compared to 112 (range, 30-365; p=0.06) days for patients who did not develop an SPM. As shown in Supplementary Figure 1, 41 (39%) of the SPM were solid tumors, 32 (30%) were myeloid malignancies, 26 (25%) were non-melanoma skin cancers, and 7 (7%) were lymphoid malignancies. The most common solid tumors were breast (6) and renal (6), and the most common myeloid malignancy was therapy-related myelodysplastic syndrome (t-MDS) (27). The median time from autoHCT to second myeloid malignancies [(t-MDS/acute myeloid leukemia (AML)] was 52.9 (range 7.9 – 130.3) months. Of the 28 patients with evaluable cytogenetic data, 13 patients (46%) had complex karyotype, and of the 20 patients with evaluable molecular data, 12 patients (60%) had a TP53 mutation and five patients (25%) had mutations in DNMT3A.

Patients with SPM received Len maintenance for a significantly longer duration compared to those without SPM [median 30.8 (range 0.03 – 118.1) months vs. 21.7 (range 0.03 – 139.6) months, respectively; p=0.004]. For patients who received maintenance for >1 year, the odds ratio (OR) for developing an SPM was 1.59 (95% CI 0.99 – 2.55; p=0.055), (vs. ≤1 year); for patients who received maintenance for >2 years, the OR for developing an SPM was 2.25 (95% CI 1.49 – 3.41; p<0.001), (vs. ≤2 years); for patients who received maintenance for >3 years, the OR for developing an SPM was 1.78 (95% CI 1.18 – 2.67; p=0.006), (vs. ≤3 years). SPM was the second most common cause of death (n=20/287, 7%), after progressive myeloma (n=220/287, 77%).

Discussion

To the best of our knowledge, this is the largest study with real world data on patients with MM who received upfront autoHCT followed by single-agent Len maintenance, with a median follow-up of almost 4 years. The outcomes reported here compare favorably to those reported in large randomized clinical trials [9, 12, 13], with median PFS and OS from autoHCT for the entire cohort of 56.6 months and 111.3 months, respectively. Len maintenance maintained its beneficial impact on survival outcomes even after >5 years of maintenance. Almost 1 out of 10 patients developed an SPM in our cohort, and longer duration of maintenance was associated with a higher odds of developing SPM.

These real-world data on the benefit of longer maintenance duration complement several previous reports, mostly from large, randomized clinical trials. A follow-up report from the STAMINA trial showed that discontinuation of Len maintenance after 38 months was associated with inferior 5-year PFS (79.5% vs. 61%, HR = 1.91, p = 0.0004) but similar OS [5]. Results from the Myeloma XI trial showed a significant PFS improvement when Len maintenance was given for up to 4 years (HR 0.56, p=0.031), with diminished benefit thereafter [6]. A retrospective analysis from The Mayo Clinic showed that receiving Len maintenance for at least 3 years was associated with improved median PFS (7.2 years vs. 4.4 years; p<0.0001) and 5-year OS (100% vs. 85%; p = 0.011) compared to a shorter maintenance period [7]. Another retrospective analysis that included 340 patients, who received various post-autoHCT maintenance regimens (Len in 89%) also found that maintenance for more than 3 years was associated with superior estimated 5-year PFS (80% vs. 50%) and OS (96% vs. 79%) compared to maintenance for less than 3 years [14]. In the present study, we found that longer duration of Len maintenance was associated with improved PFS and OS even after >5 years of maintenance, suggesting continued benefit with indefinite post-transplant maintenance.

Joseph et al. described outcomes of 1000 MM patients treated with VRD induction at the Emory University in Atlanta between 2007 and 2016[15]. Overall, 753 patients received maintenance, including single-agent lenalidomide in 60.7%. The median duration of maintenance was 59 (range 50.4-67.6) months, longer than the duration in our cohort [22.3 (range 0.03-139.6) months]. Patients who received single-agent lenalidomide maintenance in the report from Emory University all had standard-risk disease, per institutional policy, whereas in our cohort almost one fifth of patients had high-risk cytogenetics. That could partially explain the differences in maintenance duration between the two cohorts, since patients with HRMM tend to progress earlier. Furthermore, all patients in the report by Joseph et al. received at least 4 years of maintenance, suggesting there were no early discontinuations due to toxicity, perhaps owing to the previous exposure to lenalidomide in the VRD induction regimen received by all patients in that cohort. Importantly, in the study by Joseph et al., only 75% of the entire cohort received upfront autoHCT, yet data on maintenance included patients who did not undergo transplant or received autoHCT only at relapse, and also patients who received maintenance regimens other than single-agent lenalidomide[15]. Of note, the median duration of maintenance in our study is almost identical to that reported in the Mayo Clinic experience with lenalidomide maintenance, of 21.6 (range 1.2-121.2) months[7].

In our cohort, 20% of patients discontinued Len maintenance due to toxicity. This is lower than the 29.1% discontinuation rate due to toxicity in the two randomized trials included in the Len post-transplant maintenance meta-analysis [2]. We found that the reason for discontinuation of Len maintenance had prognostic significance. Patients who discontinued Len maintenance due to fatigue had superior OS compared to those who stopped maintenance due to other toxicities. To the best of our knowledge, this association has not previously been described, and warrants additional studies for confirmation.

In the current study 9% of patients developed SPM, with solid tumors (3.5%) and myeloid hematological malignancies (2.7%) being most common. In a meta-analysis of newly-diagnosed MM patients who received Len maintenance, the cumulative incidence of SPM at 5 years was lower (6.9%: 3.1% hematological, 3.8% solid) than what we observed [10]. However, that analysis included both transplant-eligible and ineligible patients. In the meta-analysis of the three major post-transplant Len maintenance trials, the cumulative incidence of SPM was higher (13.4%: 6.1% hematological malignancies and 7.3% solid tumors) [2]. Similarly, in transplant-eligible patients who received Len maintenance in the Myeloma XI trial [16], 12.2% developed SPM, which accounted for 1.8% of deaths in the transplant-eligible group, lower than the 7% we observed in the current study. Of note, in a previous analysis from our institution with a smaller cohort of patients (n=464) and a shorter follow-up (26.6 months), the incidence of SPM was 3% (n=12) [8]. This underscores the need for a longer follow-up and continued surveillance for possible secondary malignancies.

A recent meta-analysis evaluated the risk of SPM in patients receiving Len for various malignancies [17]. An increased risk ratio (RR) for developing SPM with Len treatment was observed only in patients who received this agent for MM (RR 1·42, 95% Confidence Interval 1.09–1.84). In the present study we found that a longer duration of Len maintenance was associated with a higher odds of developing SPM, reaching statistical significance after 2 years. A report by the Center for International Blood and Marrow Transplant Research (CIBMTR) evaluated the impact of SPM on survival outcomes of almost 4000 patients who received autoHCT for MM followed by post-transplant maintenance, which was mostly Len-based [18]. The authors found that the occurrence of SPM was associated with inferior PFS (HR 2.62) and OS (HR 3.85). Nonetheless, similar to the present study, the CIBMTR report showed that the leading cause of death was progression of MM, even in patients who developed SPM. In our analysis, although longer duration of maintenance was associated with an increased risk of SPM, the net effect of prolonged maintenance was improved PFS and OS.

Approximately a third of the SPM observed in the current study were hematological malignancies, mostly myeloid malignances. Almost half of the patients with t-MDS/AML had complex karyotype and 60% had mutated TP53. A study from the Mayo clinic included 43 patients who developed secondary myeloid malignancies (t-MDS, n=36; t-AML, n=7) after autoHCT [19]. In that study, lenalidomide maintenance was associated with increased risk of secondary myeloid malignancies (χ2 Yate’s correction 5.6, P = 0.002). In line with our findings, most patients in the Mayo Clinic study also had complex karyotype (72%), and 50% had mutated TP53 [19]. Indeed, prior exposure to lenalidomide has been shown to be significantly associated with the development of TP53-mutated t-MDS/AML [20].

Our results again highlight that Len maintenance alone may not be sufficient for patients with HRMM. These patients had inferior PFS (29.6 months) and OS (84.8 months) even with the use of mostly novel induction regimens and single-agent Len maintenance. Attempts have been made to intensify maintenance with Len-based combinations. In the second randomization of the FORTE trial, patients who received Len plus carfilzomib maintenance after autoHCT had superior 3-year PFS compared to patients who received single-agent Len (75% vs. 65%, p=0.023) [21]. However, other clinical trials did not observe a benefit with addition of ixazomib [22] or vorinostat [23] to post-transplant maintenance. An ongoing randomized trial is examining the addition of daratumumab to Len maintenance (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04071457). A recent analysis by our group showed a lack of benefit for Len-based combinations as maintenance for HRMM patients, although there was a trend towards a longer PFS in patients with high-risk cytogenetic abnormalities other than 1q gain or amplification [24].

Patients in our study that received KRD induction had better PFS (HR 0.53), compared to other induction regimens, mostly VRD. The ENDURANCE trial did not show a difference in survival outcomes between patients who received induction with either VRD or KRD [25]. However, that trial included patients without the intent for upfront autoHCT, and excluded most patients with high-risk cytogenetics (t(4;14) was allowed). A retrospective study by our group also did not observe a difference in 3-year PFS (p=0.25) or OS (p=0.30) between patients who received KRD or VRD induction followed by autoHCT [26]. Although most patients in the report by Gaballa et al. received post-transplant maintenance (93%), regimens varied, and only 25 patients (40%) of the KRD group received Len maintenance. In the present study, only patients that received single-agent Len maintenance after autoHCT were included, and the cohort was larger. Importantly, the present study also included patients that received other induction regimens besides KRD and VRD. Similar to our finding, a recent retrospective study observed improved 5-year PFS in patients with newly-diagnosed MM who received KRD, compared to those who received VRD (67% vs. 56%, respectively; p=0.027), with a trend towards improved 5-year OS (90% vs. 80%, respectively; p=0.053) [27]. Approximately half of the patients in both induction groups underwent upfront autoHCT in that study, though data on maintenance therapy was not provided.

Our study has several limitations inherent to a retrospective analysis, including selection bias and missing data. Decisions regarding specific induction regimens were at the discretion of the treating physician, and based on various parameters, including patient and disease characteristics, comorbidities and insurance coverage. Recent prospective trials have demonstrated a putative role for serial MRD testing during post-transplant Len maintenance to decide the maintenance duration [28, 29]. Unfortunately, we did not have serial MRD data for this retrospective analysis.

In conclusion, we report real-world data on a large cohort of patients with MM who received upfront autoHCT followed by single-agent Len maintenance, with a follow-up exceeding 4 years. PFS and OS were comparable to those reported in large clinical trials. High-risk cytogenetic abnormalities were associated with worse PFS and OS. SPM were seen in 9% of patients and were the second most common cause of death after recurrent myeloma. Continuation of Len maintenance for 3 or more years was associated with improved survival outcomes. We did not observe an upper limit of duration of maintenance for survival benefit, suggesting that for some patients indefinite post-transplant maintenance could be considered.

Supplementary Material

Supplementary Figure 1. Second primary malignancies (N=106).

Funding statement:

This work was supported in part by the Cancer Center Support Grant (NCI Grant P30 CA016672); RZO, the Florence Maude Thomas Cancer Research Professor, would like to acknowledge support from the Leukemia & Lymphoma Society (SCOR-12206-17), the Dr. Miriam and Sheldon G. Adelson Medical Research Foundation, and the Riney Family Multiple Myeloma Research Fund at MD Anderson from the Paula and Rodger Riney Foundation.

Footnotes

Conflict of interest disclosure: All authors have not declared a conflict of interest.

Ethics approval statement: The University of Texas MD Anderson Cancer Center Institutional Review Board approved this retrospective study. The research was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the 1996 Health Insurance Portability and Accountability Act guidelines.

Patient consent statement: Not applicable (retrospective analysis).

Permission to reproduce material from other sources: Not applicable.

Clinical trial registration: Not applicable.

Data availability statement:

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.

References

- 1.Kumar SK, et al. , NCCN Guidelines Insights: Multiple Myeloma, Version 1.2020. J Natl Compr Canc Netw, 2019. 17(10): p. 1154–1165. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.McCarthy PL, et al. , Lenalidomide Maintenance After Autologous Stem-Cell Transplantation in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: A Meta-Analysis. J Clin Oncol, 2017. 35(29): p. 3279–3289. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Jackson GH, et al. , Lenalidomide maintenance versus observation for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (Myeloma XI): a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase 3 trial. Lancet Oncol, 2019. 20(1): p. 57–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jagannath S, et al. , Impact of post-ASCT maintenance therapy on outcomes in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma in Connect MM. Blood Adv, 2018. 2(13): p. 1608–1615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Hari P, et al. , Long-term follow-up of BMT CTN 0702 (STaMINA) of postautologous hematopoietic cell transplantation (autoHCT) strategies in the upfront treatment of multiple myeloma (MM). Journal of Clinical Oncology, 2020. 38(15_suppl): p. 8506–8506. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Pawlyn C, et al. , Defining the Optimal Duration of Lenalidomide Maintenance after Autologous Stem Cell Transplant - Data from the Myeloma XI Trial. Blood, 2022. 140(Supplement 1): p. 1371–1372. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ho M, et al. , The Effect of Duration of Lenalidomide Maintenance and Outcomes of Different Salvage Regimens in Patients with Multiple Myeloma (MM). Blood Cancer J, 2021. 11(9): p. 158. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Mian I, et al. , Prolonged survival with a longer duration of maintenance lenalidomide after autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Cancer, 2016. 122(24): p. 3831–3837. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Attal M, et al. , Lenalidomide maintenance after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med, 2012. 366(19): p. 1782–91. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palumbo A, et al. , Second primary malignancies with lenalidomide therapy for newly diagnosed myeloma: a meta-analysis of individual patient data. Lancet Oncol, 2014. 15(3): p. 333–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kumar S, et al. , International Myeloma Working Group consensus criteria for response and minimal residual disease assessment in multiple myeloma. Lancet Oncol, 2016. 17(8): p. e328–e346. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.McCarthy PL, et al. , Lenalidomide after stem-cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med, 2012. 366(19): p. 1770–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Palumbo A, et al. , Autologous transplantation and maintenance therapy in multiple myeloma. N Engl J Med, 2014. 371(10): p. 895–905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Nunnelee J, et al. , Early versus Late Discontinuation of Maintenance Therapy in Multiple Myeloma. J Clin Med, 2022. 11(19). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Joseph NS, et al. , Long-Term Follow-Up Results of Lenalidomide, Bortezomib, and Dexamethasone Induction Therapy and Risk-Adapted Maintenance Approach in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. J Clin Oncol, 2020. 38(17): p. 1928–1937. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Jones JR, et al. , Second Primary Malignancy Incidence in Patients Receiving Lenalidomide at Induction and Maintenance; Long-Term Follow up of 4358 Patients Enrolled to the Myeloma XI Trial. Blood, 2022. 140(Supplement 1): p. 1823–1825. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Saleem K, et al. , Second primary malignancies in patients with haematological cancers treated with lenalidomide: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Haematol, 2022. 9(12): p. e906–e918. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ragon BK, et al. , Impact of Second Primary Malignancy Post-Autologous Transplantation on Outcomes of Multiple Myeloma: A CIBMTR Analysis. Blood Adv, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nadiminti K, et al. , Characteristics and outcomes of therapy-related myeloid neoplasms following autologous stem cell transplantation for multiple myeloma. Blood Cancer J, 2021. 11(3): p. 63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sperling AS, et al. , Lenalidomide promotes the development of TP53-mutated therapy-related myeloid neoplasms. Blood, 2022. 140(16): p. 1753–1763. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gay F, et al. , Carfilzomib with cyclophosphamide and dexamethasone or lenalidomide and dexamethasone plus autologous transplantation or carfilzomib plus lenalidomide and dexamethasone, followed by maintenance with carfilzomib plus lenalidomide or lenalidomide alone for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma (FORTE): a randomised, open-label, phase 2 trial. Lancet Oncol, 2021. 22(12): p. 1705–1720. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rosinol L, et al. , Ixazomib Plus Lenalidomide/Dexamethasone (IRd) Versus Lenalidomide /Dexamethasone (Rd) Maintenance after Autologous Stem Cell Transplant in Patients with Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma: Results of the Spanish GEM2014MAIN Trial. Blood, 2021. 138(Supplement 1): p. 466–466. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Jenner MW, et al. , The addition of vorinostat to lenalidomide maintenance for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma of all ages: results from ‘Myeloma XI’, a multicentre, open-label, randomised, phase III trial. Br J Haematol, 2023. 201(2): p. 267–279. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Pasvolsky O, et al. , Lenalidomide-Based Maintenance after Autologous Hematopoietic Stem Cell Transplantation for Patients with High-Risk Multiple Myeloma. Transplant Cell Ther, 2022. 28(11): p. 752 e1–752 e6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kumar SK, et al. , Carfilzomib or bortezomib in combination with lenalidomide and dexamethasone for patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma without intention for immediate autologous stem-cell transplantation (ENDURANCE): a multicentre, open-label, phase 3, randomised, controlled trial. Lancet Oncol, 2020. 21(10): p. 1317–1330. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Gaballa MR, et al. , KRD vs. VRD as induction before autologous hematopoietic progenitor cell transplantation for high-risk multiple myeloma. Bone Marrow Transplant, 2022. 57(7): p. 1142–1149. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Tan CR, et al. , Bortezomib, Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone (VRd) vs Carfilzomib, Lenalidomide and Dexamethasone (KRd) as Induction Therapy in Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma. Res Sq, 2023. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.de Tute RM, et al. , Minimal Residual Disease After Autologous Stem-Cell Transplant for Patients With Myeloma: Prognostic Significance and the Impact of Lenalidomide Maintenance and Molecular Risk. J Clin Oncol, 2022. 40(25): p. 2889–2900. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Diamond B, et al. , Dynamics of minimal residual disease in patients with multiple myeloma on continuous lenalidomide maintenance: a single-arm, single-centre, phase 2 trial. Lancet Haematol, 2021. 8(6): p. e422–e432. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Figure 1. Second primary malignancies (N=106).

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author.