Abstract

Objective:

To explore patient perspectives after receiving non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) results that suggest maternal cancer.

Methods:

Individuals who received non-reportable or discordant NIPT results during pregnancy and enrolled in a study were interviewed prior to and after receiving the outcome of their clinical evaluation for cancer. Interviews were independently coded by two researchers and analyzed thematically.

Results:

Forty-nine participants were included. Three themes were identified: 1) limited pre-test awareness of maternal incidental findings caused considerable confusion for participants, whose initial concerns focused on their babies; 2) providers’ communication influenced how participants perceived their risk of cancer and the need to be evaluated; and 3) participants perceived value in receiving maternal incidental findings from NIPT despite any stress it caused during their pregnancy.

Conclusion:

Participants viewed the ability to detect occult malignancy as an added benefit of NIPT and felt strongly that these results should be disclosed. Obstetric providers need to be aware of maternal incidental findings from NIPT, inform pregnant people of the potential to receive these results during pre-test counseling, and provide accurate and objective information during post-test counseling.

Clinical Trial Registration:

Incidental Detection of Maternal Neoplasia Through Non-Invasive Cell-Free DNA Analysis (IDENTIFY), a Natural History Study, NCT4049604.

1 |. INTRODUCTION

Over the last decade, reports of maternal cancer as an explanation for unusual or discordant non-invasive prenatal testing (NIPT) results using cell-free DNA sequencing of maternal plasma have accumulated worldwide, with over 100 cases published.1–7 Although these retrospective data demonstrate that NIPT can incidentally detect cancer in asymptomatic pregnant individuals, there is currently limited prospective evidence to inform patient counseling and clinical management of NIPT results that suggest maternal cancer. Consequently, there is no standardized approach to these cases in most countries. How clinical NIPT laboratories identify and report concerns for maternal malignancy, what information clinicians disclose to pregnant individuals, and what clinical evaluation is offered varies considerably in the United States.8,9

While research on the validity and clinical utility of these results is ongoing, questions remain about whether the potential benefits of disclosing NIPT results that suggest an occult malignancy outweigh the potential harms.8–10 Although various stakeholders have offered their perspectives,8,10,11 the perspectives of pregnant people who receive these results have not been considered to date.

The objective of this analysis was to explore experiences receiving NIPT results that suggest maternal cancer and being offered a follow-up medical evaluation. We aimed to understand the needs, values, priorities, and experiences of individuals who receive these results to better inform patient counseling.

2 |. METHODS

2.1 |. Participants

The qualitative data analyzed here were collected from participants in the ongoing IDENTIFY study (Incidental Detection of Maternal Neoplasia through Non-Invasive Cell-Free DNA Analysis) (ClinicalTrials.gov Identifier: NCT04049604). IDENTIFY is a prospective, longitudinal study enrolling individuals 18 years and older who receive non-reportable or discordant NIPT results that suggest a maternal rather than a fetal finding, as determined by the clinical NIPT laboratory and/or the patient’s health care provider. It aims to identify the biological causes underlying non-reportable or discordant NIPT results and to generate prospective evidence to inform the best approach for diagnostic workup of pregnant people who receive NIPT results that suggest maternal cancer. Individuals may be pregnant or up to 2 years postpartum at the time they enroll. Participants undergo a standardized cancer screening evaluation, including whole-body magnetic resonance imaging, and repeat cell-free DNA sequencing using a common NIPT platform. Individuals who meet eligibility criteria but who have already been diagnosed with cancer can participate in cohort 2 of IDENTIFY, which involves biospecimen collection and medical record review. IDENTIFY was approved by the National Institutes of Health’s Institutional Review Board (Protocol Number: 19-C-0132). All participants provided written informed consent.

2.2 |. Qualitative data collection

This paper reports on the qualitative data collected from participants. Between April 2020 and March 2023, most participants engaged in two semi-structured telephone interviews conducted by an experienced qualitative researcher (S.M.) who was otherwise uninvolved in the participant’s clinical evaluation. Semi-structured interviews allow participants to provide in-depth responses to open-ended questions based on their experiences and perspectives, and for the interviewer to ask follow-up questions based on participants’ responses.12 The first interview (~60 min) was conducted before participants’ cancer screening evaluation and explored individuals’ decisions to pursue NIPT, experiences receiving NIPT results that suggested maternal cancer, and decisions to be evaluated for cancer. The second interview (~30 min) took place after participants learned the results of their medical evaluation and asked them to share their thoughts on their experiences and the risks and benefits of disclosing maternal incidental findings during pregnancy. Follow-up interview questions were tailored according to whether a person was diagnosed with cancer. A small subset of individuals enrolled in cohort 2 of the IDENTIFY study took part in one interview (~60 min) that encompassed the initial and follow-up interview topics. Although cohort 2 participants differed from the primary cohort in that they already had a cancer diagnosis at the time of their interview, their perspectives were included because they offered insights into why individuals may initially choose not to pursue clinical follow-up after receiving NIPT results that suggest maternal cancer.

2.3 |. Data analysis

Data analysis followed the six phases for thematic analysis.13 Audio-recordings of the interviews were transcribed verbatim and read repeatedly by one researcher (A.T.) to become familiar with the data and to generate initial key topics (codes). Two researchers (A.T. and S. M.) independently coded each interview using NVivo 11 (Lumivero. com), compared codes and identified themes. A.T. and S.M. met biweekly to discuss coding and the meaning and implications of the themes. Selected quotes, followed by participant identification numbers, are presented to illustrate identified themes. Quotes from follow-up interviews also indicate whether the participant was diagnosed with cancer.

3 |. RESULTS

3.1 |. Participant characteristics

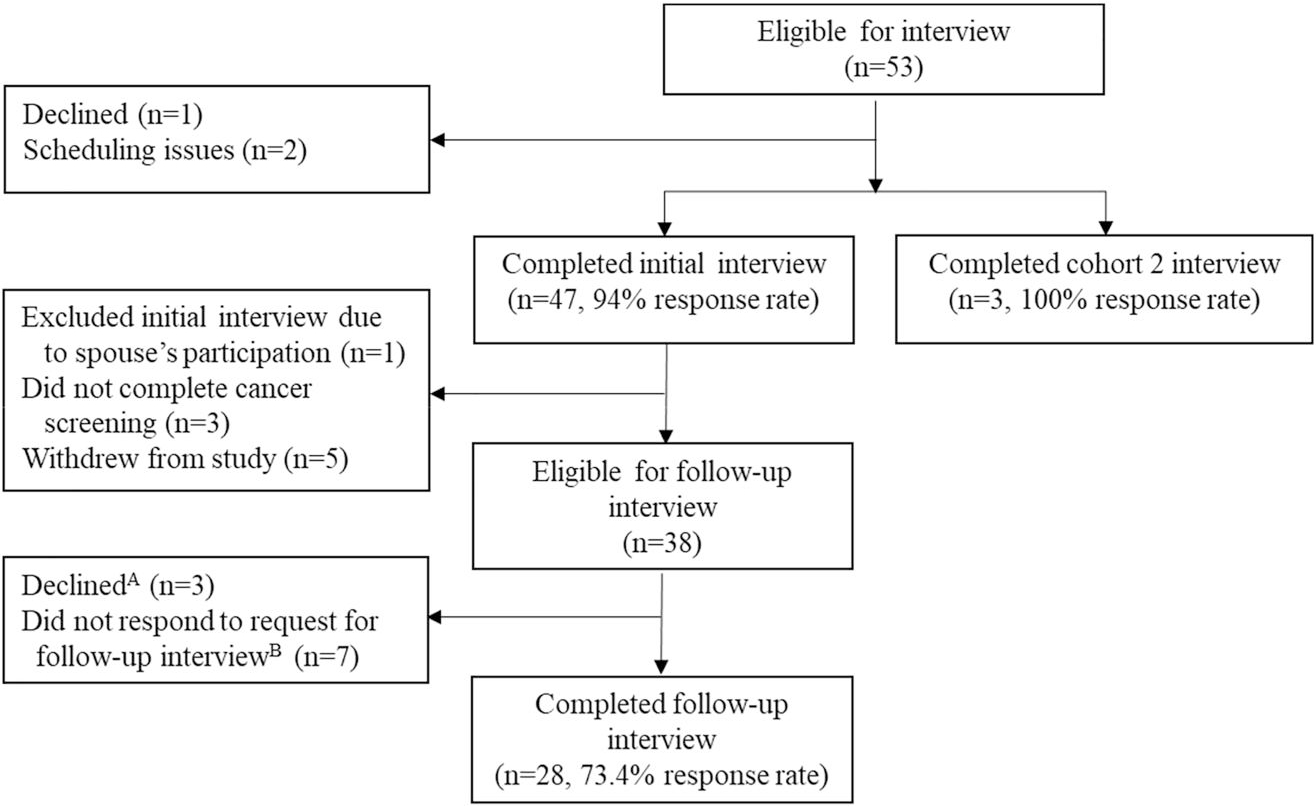

The perspectives of 49 individuals were included (Figure 1). Forty-six participants were enrolled in the primary IDENTIFY cohort, and three participants were enrolled in cohort 2. Follow-up interviews were conducted with 28 participants; half (14/28) were diagnosed with cancer. Participant characteristics are presented in Table 1.

FIGURE 1.

Flowchart of participant inclusion. AThese individuals had advanced cancer and were dealing with medical challenges at the time they were approached for a follow-up interview. BThree individuals with cancer and four individuals without cancer could not be reached for a follow-up interview.

TABLE 1.

Selected participant characteristics.

| Characteristic | Value (n = 49) |

|---|---|

| Age | |

| Mean ± SD, years | 32.4 ± 6.2 |

| Range, years | 21–53 |

| Self-reported race, ethnicity | |

| Asian or Pacific Islander | 2 (4.1%) |

| Black or African American | 3 (6.1%) |

| White, Hispanic | 3 (6.1%) |

| White, non-Hispanic | 41 (83.7%) |

| Geographic region | |

| Canada | 2 (4.1%) |

| United States | 47 (95.9%) |

| Northeast | 9 (18.4%) |

| Southeast | 23 (46.9%) |

| Midwest | 8 (16.3%) |

| Southwest | 4 (8.2%) |

| West | 7 (14.3%) |

| Health care provider or personal connectiona | 17 (34.7%) |

| Health care provider | 9 (18.4%) |

| Close connection (spouse, parent, sibling) | 8 (16.3%) |

| Pregnancy status at time of enrollment | |

| Pregnant | 39 (79.6%) |

| Postpartum | 10 (20.4%) |

| Primigravida | 22 (44.9%) |

| NIPT results | |

| Non-reportable or atypical finding | 33 (67.3%) |

| 2 or more abnormalities reported | 13 (26.5%) |

| 1 abnormality reported, discordant | 3 (6.1%) |

| Time elapsed from initial NIPT results to study enrollment | |

| Mean ± SD, weeks | 14.4 ± 23.8 |

| Range, weeks | 0.3–111.9 |

| Clinical outcome | |

| Cancer | 24 (49.0%) |

| No cancer | 22 (44.9%) |

| Did not complete clinical evaluation | 3 (6.1%) |

Abbreviations: SD, standard deviation; NIPT, non-invasive prenatal testing.

We did not systematically inquire about occupation or connection to healthcare. This reflects people who mentioned being a health care provider or being closely connected to a health care provider as important to their experiences

Nearly all participants were referred to the IDENTIFY study by a health care provider (47/49, 95.9%). One participant who is a genetic counselor referred herself, and another participant in cohort 2 also referred herself after learning about the study from a National Public Radio broadcast (https://www.npr.org/sections/health-shots/2022/12/23/1141679898/a-new-kind-of-blood-test-can-screen-for-many-cancers-as-some-pregnant-people-lea). Approximately 80% of participants (39/49) enrolled in the study while they were pregnant, and 10 participants (20.4%) enrolled when they were postpartum. Participants’ initial testing was performed by one of eight different clinical laboratories that offer NIPT in the United States. The amount of information included in the written laboratory report varied, reflecting the lack of a uniform approach to reporting these cases. In approximately two-thirds of the cases (33/49, 67.3%) participants received either “non-reportable” results or results that suggested an “atypical finding, likely maternal in origin.”

3.2 |. Themes

Three themes emerged from the qualitative analysis: 1) limited pre-test awareness of maternal incidental findings caused considerable confusion for participants, whose initial concerns focused on their babies; 2) providers’ communication influenced how participants perceived their risk of cancer and the need to be evaluated; and 3) participants perceived value in receiving maternal incidental findings from NIPT despite any stress it caused during their pregnancy.

3.2.1 |. Limited pre-test awareness

Participants pursued NIPT hoping to receive reassuring information about their pregnancy, and many were excited to learn the sex of their baby. The potential to receive inconclusive or non-reportable results that could suggest a maternal health condition was unknown to all but one participant, who is a genetic counselor. As a result, participants reported feeling “blindsided,” “shocked,” and “confused” when they received their results.

“Even though I’m a nurse, it was still like super confusing cause I didn’t realize this test had anything to do with me. I thought it was just the baby.” (028)

Compounding the participants’ confusion was their providers’ lack of familiarity with non-reportable results and their potential significance for maternal health.

“They [the obstetric providers] stressed over and over again that they had not seen this result before, did not know what it meant.” (050)

In some cases, participants reported that they were counseled by their obstetric provider that the non-reportable result was due to insufficient fetal fraction, a sample-related issue, or a laboratory error. Approximately one-third of the participants repeated their NIPT, and several participants had the test performed three times.

“I didn’t even know that it was not reportable the first time. I thought it was just a bad sample, is what I had been told.” (021)

Once participants realized that the non-reportable result was not a testing error, they worried that the results indicated a problem with their pregnancy. Participants reported feeling “devastated,” “terrified,” and some feared that they were losing their pregnancy. This concern for the fetus’ health persisted even for those who were informed that the NIPT was likely detecting a maternal, rather than a fetal, health condition.

“I’m, like, worried about the baby now because although they’re saying there’s probably nothing wrong, I just feel like my doctor doesn’t really even know what’s wrong, so how can she even know that for sure?” (017)

After receiving reassuring information about their fetus through ultrasound examination or diagnostic testing, many participants remained focused on their fetus’ health and did not readily shift their focus to their own health.

“The only thing I cared about was the health of my baby. I was like, whatever happens to me, I don’t care.” (019)

When participants considered a potential problem with their own health, they often spoke pragmatically. Sentiments such as “it is what it is, I have no control over it” (039) and “whatever happens, happens and we’ll figure it out from there” (032) were common across participants. This pragmatic approach to their own health was noticeably different from how participants, often emotionally, discussed their concerns about their baby’s health.

Those participants who expressed more concern about their health often had other children at home who served as acute reminders of their need to be healthy and alive.

“I feel like if I didn’t have children, I mean, I think it would, of course, still be scary, but to think about my kids, I don’t want to leave them without a mother.” (027)

3.2.2 |. Providers’ communication

Although having children motivated some participants to be evaluated for cancer, many participants were ambivalent about pursuing an evaluation. They were young, asymptomatic, and had unremarkable family histories, making it difficult to imagine that they could have cancer. Therefore, providers’ communication became an important factor in participants’ decisions to be evaluated for cancer.

Many participants reported that their providers “brushed off,” “glossed over” or “downplayed” their risk of cancer, or even reassured them that it was very unlikely that they had cancer. Consequently, some participants in the primary IDENTIFY cohort, as well as in cohort 2, initially chose not to pursue an evaluation because it did not seem necessary.

“I think that the parties [OB and hematologist] that were discussing my test results with me were trying to make sure, as a pregnant woman, I was not overly stressed. And as a result, I downplayed it, as well.” (037)

Contradictory messages, insufficient information, including whether it was safe to be evaluated during pregnancy, and a lack of guidance regarding next steps were sources of stress and confusion for participants, and ultimately barriers to a timely evaluation.

“The back and forth and contradictory messages between physicians, starting from the OB who said it was nothing and their MFM department that said it was nothing, to [a different MFM] saying it was potentially something, to then the oncologist saying it was potentially nothing…I think it just adds to the like, this general feeling around all of this of, like, I’m floating in outer space, and I can’t land somewhere.” (039)

Participants appreciated when their providers actively sought information about the NIPT results, communicated information in a direct and objective way, and established a plan for follow-up.

“I felt very comforted knowing that when my OB had gotten those results she immediately consulted with the other doctors at the practice, and then consulted with the [NIPT] lab, and then with the genetic counselor…[I appreciated] that everyone’s getting their minds together versus having the experience where they’re just like, I don’t know, you’re going to have to go to someone else to figure it out.” (021)

In some cases, participants reported that their provider was the main reason they decided to be evaluated for cancer.

“It [the non-reportable result] could be so many different things, I wasn’t like very stressed about it. I wouldn’t have pursued anything on my own to figure out those answers, but the genetic counselor, she told me about the [IDENTIFY] study and said it would be beneficial to me, if I was interested, because then I could find out if there was anything…So that’s when I started thinking, let’s see what’s going on.” (013)

Individuals described benefitting from speaking with genetic counselors and maternal fetal medicine specialists, and many participants wished that they had access to these providers sooner.

“The single most helpful conversation was the one with the genetic counselor.” (002)

They also often noted how the provider’s knowledge and the delivery of the information impacted their decisions to be evaluated. Suggestions for post-test counseling are presented in Table 2.

TABLE 2.

Post-test counseling considerations.

| Suggestion | Quotation |

|---|---|

| Ensure primary provider has sufficient knowledge of the results or involves a knowledgeable provider in results disclosure | “Women should 100% be told by someone who really understands what this means and can really talk a woman through it.” (040) |

| Consider practical and affective quality aspects of the results disclosure | “The information is not going to be different, but the way that you deliver it is so important. Like, are you somewhere that you can really listen? Is there someone [who] can be with you? All of the things to kind of help a pregnant person process this emotionally and intellectually, I think should be put in place.” (040) |

| • Timing, setting, whether patient wants to include another person in the discussion | |

| • Tone of voice, empathy | |

| Be transparent about the uncertainty of the results and present a plan for follow-up | “I would’ve wanted them to say…here’s what we know. Here’s what we don’t know. Here’s where it just is in your best interest to follow-up, but we’re not going to know until we know. And that’s it. That, to me, feels like the most honest answer about all of this.” (043) |

| “I just think that some reassurance of like, this is an unknown, and these are the exact steps we’re going to follow to figure out what it is, if you want to, can be such a grounding force in that moment.” (040) | |

| Provide sufficient information to facilitate informed decision-making about pursuing an evaluation | “We decided to [delay my evaluation until after delivering my baby]. I only met with [the oncologist] to establish care and have his direction. He was semi-familiar with the test [NIPT]. He said, I’ve seen a lot of flukes, I’ve seen some malignancies, but, you know, this really could be nothing. So, I was holding on to that. There was always a slight possibility [of cancer], but I didn’t know how great it was. I still don’t.” (043) |

| • Current understanding of the risk for cancer | |

| • Ability to be screened safely during pregnancy | “If there’s a safe strategy to find out whether or not an individual has cancer [during pregnancy, providers] need to really make sure that their patients are aware of that fact, because I probably would have opted to do anything that was safe to do while I was pregnant.” (037) |

| Present information in a direct and objective way | “[I appreciated] that she [the genetic counselor] was very direct. I Feel like sugarcoating is not the best way of going about telling someone bad news, and I don’t feel like she did that at all. She was very clear cut about what the results meant and how they were obtained.” (027) |

| Avoid statements that may create a false sense of certainty | “They shouldn’t be giving that false sense of security of like, [your NIPT] isn’t abnormal enough to be cancer. Like, okay, tell that to the 10-cm tumor in my chest.” (015) |

| “[The specialist] was explaining it to me and he was just like there’s no way [it’s cancer], like, he just acted like it would literally be impossible, and that’s not the case.” (065) | |

| Personalize information based on what is known about the NIPT results and/or the patient’s history | “I was given very vague options between this could be cancer or this could be nothing. And I understand that they don’t want to put ideas in your head if they aren’t likely, but in my situation, looking back on it…everything [they knew about the NIPT result] was kind of screaming, hey this is cancer, or this is a tumor, um, and I was given very vague, like, oh, well, you know, it could be nothing.” (010) |

| “At the beginning they suggested maybe I had a fibroid. I was, like, very adamant, like, no, there’s no way it’s a fibroid, and they kept using that example…I used to go every day or every other day for ultrasounds before my egg retrieval, so I knew what was in there.” (028) | |

| Help patients consider both the potential benefits of pursuing cancer screening and anticipated regret | “You never really want those answers, but you need them, even if for peace of mind that everything is okay…I think it’s definitely worth doing especially because it’s not an invasive workup…I think it’s worth anybody’s time if they find something that needs to be found.” (032) |

| “In that moment, when I was so sick and really not thinking that I was going to be okay, I was filled with a lot of regret that I had let [my daughter] down [by not pursuing an evaluation sooner].” (065) |

3.2.3 |. Perceived value receiving maternal incidental findings

Although the experience of receiving unexpected NIPT results was stressful and the decision to be evaluated for cancer was rarely straightforward, all participants felt strongly that NIPT results that suggest a maternal health condition should be disclosed to pregnant people.

“I’m definitely grateful that I received the result. I think not telling the mother that there could potentially be something wrong with her is ethically wrong, in my opinion.” (054, no cancer)

Furthermore, most participants felt strongly that the potential to receive maternal incidental findings should be mentioned during pre-test counseling. Participants indicated that knowing that NIPT results can sometimes raise concerns for maternal health would not have deterred them from proceeding with NIPT but would have “planted the seed” (044) that this outcome is possible. They thought that this knowledge would have helped them understand the implications of the results for their baby and for themselves sooner.

“I still would have gotten it [NIPT]. I think I would have pursued workup sooner if I had known. I didn’t even know at that point that NIPT could pick up things like fibroids and other tumors.” (015)

Few participants expressed regret about pursuing NIPT during their initial interview and no participant expressed regret about NIPT in their follow-up interview. This was true for individuals diagnosed with cancer and for those who were not. The ability of NIPT to detect an occult malignancy was perceived as an added benefit of the test.

“If this did unearth cancer, it is in a way, like, such an amazing tool to maybe find something early, or find something that you might not otherwise find until it’s too late.” (040)

During the follow-up interviews, participants reiterated that the potential benefits of receiving medically actionable information outweighed any of the stress or anxiety they experienced. Individuals who were diagnosed with cancer were universally grateful for their NIPT results.

“Even though it added that stress, it was a very positive thing for me, because it was the only thing that led me to a diagnosis.” (010, advanced cancer)

“Maybe in theory everything would have been fine, and I would have found out after my baby was born, and maybe all that stress while pregnant would have just happened a year later, but I just can’t help but think that the stress still would have happened. And if anything, my cancer would have been more progressed.” (017, early-stage cancer)

Participants who were not diagnosed with cancer at the time of their evaluation felt significant relief. All indicated that they had peace of mind and none expressed ongoing concerns or anxiety about their health. Although some articulated that the NIPT results caused unnecessary stress, they still thought this information should be disclosed to pregnant people.

“I feel like that stress [of the NIPT results] is not like that big of a negative impact…I would still want to know.” (018, no cancer)

“I can only imagine if this did find some sort of cancer that I would be, like, incredibly grateful for the experience.” (051, no cancer)

The challenges that participants faced and their initial reluctance to be evaluated for cancer were frequent topics brought up by participants during their follow-up interviews. Their advice to other pregnant people who received these results was to seek answers.

“I would encourage them to proceed with the evaluation for cancer. It doesn’t hurt…And if it all turns out to be nothing then amazing, that’s wonderful…In my case, the outcome wasn’t so rosy, so I would advise any woman to take the test [NIPT], and if they get abnormal results, to go down every path to try and figure out what the answers might be.” (056, early-onset cancer)

4 |. DISCUSSION

Receiving prenatal screening results that suggest maternal cancer was described as a disorienting experience, exacerbated by participants’ lack of awareness that NIPT could reveal anything about maternal health. Most participants initially feared there was a problem with their baby and were relieved to learn that the results suggested a maternal condition. Participants described numerous barriers to seeking a timely clinical evaluation, including an absence of symptoms, insufficient information to make informed choices about pursuing an evaluation, and a lack of clear concern and guidance from their providers. Participants viewed NIPT results that suggest maternal cancer as potentially lifesaving and thought that it would be unethical not to disclose this information to pregnant people. However, participants indicated that improvements to pre- and post-test counseling were needed.

Recent retrospective studies2,3,7 have reported high rates of cancer detection (67%–73%) in asymptomatic pregnant people when NIPT results were classified as malignancy suspicious, highlighting the importance of facilitating a timely clinical evaluation for pregnant people who receive these results.14 However, the average amount of time that elapsed between when participants received their NIPT results and enrolled in the IDENTIFY study (the first step to pursuing cancer screening) was 3 months (Table 1). The experiences of this study’s participants shed light on numerous barriers that prevent timely evaluation and highlight ways in which health care providers can help reduce them and improve care.

Beginning with pre-test counseling, participants indicated they would have benefited from knowing that NIPT can reveal information about maternal health. Although professional society statements recommend that pre-test counseling for NIPT include the possibility of incidental findings,15,16 our participants’ experiences indicate that this is still not the standard practice in the US. Now that NIPT is routinely offered to all pregnant people,16 primary obstetric providers are on the front lines of counseling for NIPT. Although it is unknown how often they mention the possibility of incidental findings during pre-test counseling, prior studies suggest that gaps in knowledge, particularly pertaining to topics not commonly encountered, and time constraints may limit pre-test discussions.17–19 Our data suggest that informing patients of the potential to receive unexpected results that could suggest a maternal health condition during pre-test counseling would reduce confusion and improve understanding at the time of results disclosure.

Prior studies of genetic counselors have found that many feel uncomfortable and/or unprepared to counsel patients who receive NIPT results that suggest maternal malignancy.9,20,21 Pregnant people and their providers face significant uncertainty when NIPT results are discordant or non-reportable due to a wide range of possibilities that must be considered,22 limited information on the probability of each possible outcome, and insufficient evidence to guide maternal evaluation.15 Research on genomic sequencing in the prenatal setting has found that providers are often reluctant to disclose uncertain results due to concerns that they may create unnecessary patient anxiety.23 Participants reported that their providers downplayed their risk of cancer because they were trying not to alarm them when disclosing their results. This approach to counseling, however, made participants question their need to be evaluated, particularly in the absence of symptoms.

The important role that obstetric providers played in participants’ experiences and their decisions to pursue cancer screening highlights the critical need for providers to be aware of maternal incidental findings from NIPT and to effectively communicate accurate information. Participants’ preferences for post-test counseling align with published frameworks for communicating uncertainty24,25 and delivering bad news.26 Participants valued their providers’ transparency about the uncertainty of the results and their efforts to facilitate shared decision-making. They benefited from the compassionate delivery of objective information and a clear plan for next steps. However, there are currently numerous challenges to facilitating an efficient and thorough maternal workup in an asymptomatic pregnant person in the United States.14 Evidence-based practice guidelines for maternal evaluation following unexpected NIPT results will be critical for providers to facilitate maternal follow-up.

Numerous factors (e.g., clinical utility, cost of the subsequent work-up that may not be covered by insurance) must be considered when evaluating the potential benefits and risks of disclosing NIPT results that suggest maternal cancer, including the essential perspectives of pregnant people who receive these results. Strengths of our study include the in-depth understanding of participants’ experiences captured by qualitative interviews and the prospective longitudinal study design. We were able to capture a variety of experiences, ranging from individuals who sought medical follow-up immediately, to individuals who delayed their evaluation until after they had delivered their baby, and to individuals in cohort 2 who did not initially pursue a cancer evaluation but were ultimately diagnosed with cancer when they became symptomatic.

Our study does not capture the experiences of people who were not referred to the IDENTIFY study or who were referred to the IDENTIFY study and chose not to enroll and be evaluated for cancer. Most participants were White and non-Hispanic. Over one-third of the participants were health care providers themselves or had a personal connection to one (Table 1). It is possible that they think about incidental findings differently and/or can access information and navigate the health care system more easily. If people without similar occupations or personal connections are less likely or less able to pursue an evaluation, this has the potential to increase disparities in cancer screening.

In conclusion, non-reportable or discordant NIPT results that suggest a maternal health condition should not be dismissed. They may be the only indication that a pregnant person has cancer. Participants felt strongly that this information should be disclosed. Effective communication of accurate information is critical to pregnant people pursuing a timely evaluation.

Key points.

What’s already known about this topic?

Non-invasive prenatal screening (NIPT) using cell-free DNA sequencing of maternal plasma can incidentally detect maternal cancer.

A “non-reportable” test result may be generated when the sequencing results do not conform to an individual laboratory’s proprietary analytic algorithm. There are both technical (e.g., insufficient DNA or low fetal fraction) and biological (e.g., vanishing twin, confined placental mosaicism, maternal incidental finding) reasons for this to occur. NIPT results that suggest maternal cancer are often non-reportable.

There is limited prospective evidence to inform patient counseling and medical management of NIPT results that suggest maternal cancer.

In the United States, how NIPT laboratories report malignancy suspicious results, what information clinicians disclose to pregnant individuals, and what clinical evaluation is offered varies.

What does this study add?

This study describes patients’ perspectives on receiving NIPT results that suggest maternal cancer.

Pre- and post-test counseling recommendations were made based on participants’ experiences.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors thank the participants for sharing their experiences and the many clinicians and laboratories who refer patients to the IDENTIFY study. We thank Benjamin Berkman, JD, MPH, for his feedback on the qualitative interview guide. This research was funded by the NIH Intramural Research Programs HG200400-04 and BC011584 (2020).

Funding information

NIH Intramural Research Program, Grant/Award Numbers: BC011584 (2020), HG200400-04

Footnotes

CONFLICT OF INTEREST STATEMENT

The authors have no conflicts of interest to disclose.

These data were presented in part at the 26th International Conference on Prenatal Diagnosis and Therapy, June 19–23, 2022, Montreal, Canada.

DATA AVAILABILITY STATEMENT

It is not possible to completely remove identifying information from the qualitative data, so these data are not available for public use. The interview guide is available upon request.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bianchi DW, Chudova D, Sehnert AJ, et al. Noninvasive prenatal testing and incidental detection of occult maternal malignancies. JAMA. 2015;314(2):162–169. 10.1097/01.ogx.0000473791.14913.b7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Heesterbeek CJ, Aukema SM, Galjaard RH, et al. Noninvasive prenatal test results indicative of maternal malignancies: a nationwide genetic and clinical follow-up study. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(22):2426–2435. 10.1200/jco.21.02260 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Lenaerts L, Brison N, Maggen C, et al. Comprehensive genome-wide analysis of routine non-invasive test data allows cancer prediction: a single-center retrospective analysis of over 85,000 pregnancies. EClinicalMedicine. 2021;35:100856. 10.1016/j.eclinm.2021.100856 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Dow E, Freimund A, Smith K, et al. Cancer diagnoses following abnormal noninvasive prenatal testing: a case series, literature review, and proposed management model. JCO Precis Oncol. 2021;5:1001–1012. 10.1200/po.20.00429 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Li J, Ju J, Zhao Q, et al. Effective identification of maternal malignancies in pregnancies undergoing noninvasive prenatal testing. Front Genet. 2022;13:802865. 10.3389/fgene.2022.802865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Osborne CM, Hardisty E, Devers P, et al. Discordant noninvasive prenatal testing results in a patient subsequently diagnosed with metastatic disease. Prenat Diagn. 2013;33(6):609–611. 10.1002/pd.4100 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goldring G, Trotter C, Meltzer JT, et al. Maternal malignancy after atypical findings on single-nucleotide polymorphism-based prenatal cell-free DNA screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2023;141(4):791–800. 10.1097/aog.0000000000005107 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Rink BD, Stevens BK, Norton ME. Incidental detection of maternal malignancy by fetal cell-free DNA screening. Obstet Gynecol. 2022;140(1):121–131. 10.1097/aog.0000000000004833 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Giles ME, Murphy L, Krstić N, et al. Prenatal cfDNA screening results indicative of maternal neoplasm: survey of current practice and management needs. Prenat Diagn. 2017;37(2):126–132. 10.1097/01.ogx.0000515493.54328.24 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Benn P, Plon SE, Bianchi DW. Current Controversies in Prenatal Diagnosis 2: NIPT results suggesting maternal cancer should always be disclosed. Prenat Diagn. 2019;39(5):339–343. 10.1002/pd.5379 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Non-invasive Prasad V., serum DNA pregnancy testing leading to incidental discovery of cancer: a good thing? Eur J Cancer. 2015; 51(16):2272–2274. 10.1016/j.ejca.2015.07.029 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Weiss RS. Learning from Strangers: The Art and Method of Qualitative Interview Studies. Free Press; 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Braun V, Clarke V. Using thematic analysis in psychology. Qual Res. 2006;3(2):77–101. 10.1191/1478088706qp063oa [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Turriff AE, Annunziata CM, Bianchi DW. Prenatal DNA sequencing for fetal aneuploidy also detects maternal cancer: importance of timely workup and management in pregnant women. J Clin Oncol. 2022;40(22):2398–2401. 10.1200/jco.22.00733 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dungan JS, Klugman S, Darilek S, et al. Noninvasive prenatal screening (NIPS) for fetal chromosome abnormalities in a general-risk population: an evidence-based clinical guideline of the American College of Medical Genetics and Genomics (ACMG). Genet Med. 2023;25(2):100336. 10.1016/j.gim.2022.11.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. ACOG Practice Bulletin No 226. Obstetrics Committee on Genetics Society for Maternal-Fetal Medicine. Screening for fetal chromosomal abnormalities. Obstet Gynecol. 2020;136(4):e48–e69. 226. 10.1097/aog.0000000000004084 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Oxenford K, Daley R, Lewis C, et al. Development and evaluation of training resources to prepare health professionals for counselling pregnant women about non-invasive prenatal testing for Down syndrome: a mixed methods study. BMC Pregnancy Childbirth. 2017;17(1):132. 10.1186/s12884-017-1315-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Martin L, Gitsels-van der Wal JT, Bax CJ, et al. Nationwide implementation of the non-invasive prenatal test: evaluation of a blended learning program for counselors. PLoS One. 2022;17(5):e0267865. 10.1371/journal.pone.0267865 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Farrell RM, Agatisa PK, Mercer MB, et al. The use of noninvasive prenatal testing in obstetric care: educational resources, practice patterns, and barriers reported by a national sample of clinicians. Prenat Diagn. 2016;36(6):499–506. 10.1002/pd.4812 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Orta AS. NIPT – Emerging Issues: Genetic Counselors’ Experiences and Perspectives with Incidental Findings: Graduate Program in Genetic Counseling. Brandeis University; 2016. https://hdl.handle.net/10192/32288 [Google Scholar]

- 21.Case J, Hazelton P. Genetic counselors’ preparedness for incidental findings from non-invasive prenatal testing. Human Genetics Theses. 2018;47. https://digitalcommons.slc.edu/genetics_etd/47 [Google Scholar]

- 22.Bianchi DW. Cherchez la femme: maternal incidental findings can explain discordant prenatal cell-free DNA sequencing results. Genet Med. 2018;20(9):910–917. 10.1038/gim.2017.219 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.HornR, Parker M. Health professionals’ and researchers’ perspectives on prenatal whole genome and exome sequencing: ‘we can’t shut the door now, the genie’s out, we need to refine it’. PLoS One. 2018;13(9):e0204158. 10.1371/journal.pone.0204158 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Simpkin AL, Armstrong KA. Communicating uncertainty: a narrative review and framework for future research. J Gen Intern Med. 2019;34(11):2586–2591. 10.1007/s11606-019-04860-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Harding E, Hammond J, Chitty LS, et al. Couples experiences of receiving uncertain results following prenatal microarray or exome sequencing: a mixed-methods systematic review. Prenat Diagn. 2020;40(8):1028–1039. 10.1002/pd.5729 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Baile WF, Buckman R, Lenzi R, et al. SPIKES-A six-step protocol for delivering bad news: application to the patient with cancer. Oncol. 2000;5(4):302–311. 10.1634/theoncologist.5-4-302 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

It is not possible to completely remove identifying information from the qualitative data, so these data are not available for public use. The interview guide is available upon request.