Abstract

Sexual health education experienced by lesbian, gay, and bisexual (LGB) youth varies widely in relevancy and representation. However, associations among sexual orientation, type of sex education, and exposure to affirming or disaffirming content have yet to be examined. Understanding these patterns can help to address gaps in LGB-sensitive sex education. Our goal in this study was to examine the prevalence and associations among abstinence-only until marriage (AOUM) and comprehensive sex education with LGB-affirming and -disaffirming content sought/received before age 18 (from 1999–2014) by sexual orientation (completely heterosexual with same-sex contact, completely heterosexual with no same-sex contact, mostly heterosexual, bisexual, gay/lesbian) in a sample of 12,876 US young adults from the Growing Up Today Study. Compared to completely heterosexual referents, LGB participants who received AOUM sex education were more likely to encounter LGB-disaffirming content, and this effect was largest among sexual minority participants. Conversely, exposure to comprehensive sex education was associated with receipt of LGB-affirming information. Overall, participants commonly reported receiving AOUM sex education, which may lead to deficits and potential harm to sexual minorities.

Keywords: Sexual Minorities, Sex Education, Sexual Health, Adolescent Health, Stigma

Sexuality education programming in the United States

In the USA, sexuality (sex) education has historically taken the form of ‘abstinence-only until marriage’ (AOUM) curricula and programmes. AOUM curricula have stressed the benefits of postponing sex until marriage, that abstinence is necessary to prevent sexual risk outcomes like adolescent pregnancy and sexually transmitted infections (STIs), that monogamy is normative and sexual activity outside marriage is harmful (including to the children resulting from such pregnancies), how to say no to sex, and the link between risk behaviours like substance use and sexual coercion (“Social Security Act §510 Separate Programme for Abstinence Education” 1996).

Since 1981, when the U.S. federal government under the Reagan administration passed the Adolescent Family Life Act (AFLA; Santelli et al. 2006), school-based programming that centres AOUM has been especially prominent, emphasising the negative consequences of sexual behaviour and the idea that heterosexual marriage is normative and ideal (Elia and Eliason 2010b; Santelli et al., 2006; Santelli et al. 2017). However, in spite of numerous evaluation studies showing little to no efficacy for AOUM programming in improving safe-sex outcomes (Kirby 2007; CDC 2014), the approach remains a widely taught type of sex education in the USA (Weaver, Smith, and Kippax 2005; Hall and Witkemper 2019), compared to countries with more inclusive forms of sex education programming (e.g., Sweden, Denmark, the Netherlands, Australia and France). Despite these differences, many countries grapple with questions related to the source (e.g., family, peers, school), timing (e.g., primary vs. secondary school), and content (e.g., sexual minority inclusivity) of sex education (Elia & Eliason 2010a; Ellis & Bentham 2021; Epps, Markowski, & Cleaver 2021; Jones & Hillier 2012; Leung et al. 2019; Weaver, Smith, & Kippax 2005). A study conducted by Kirby, Laris, & Rolleri (2005) reviewed evaluations of 83 sex and HIV education programmes in developing and developed countries. Findings from the review revealed that while the majority of programmes encouraged abstinence many programmes also discussed the use of condoms or contraception. Among the 83 programmes, seven percent promoted abstinence only and most of these were based in the USA.

An alternative to AOUM programming is comprehensive sex education, which, like AOUM, includes content on reproductive development, pregnancy prevention, STIs and the benefits of delaying sexual debut, but also includes content on healthy relationships, communication, sexual violence, online communication, and sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) (Goldfarb and Lieberman 2021; ACOG n.d.) among other issues. Some forms of comprehensive sex education also involve content about sexual consent and decision-making, including the skills needed to negotiate or decline sex (ACOG n.d.). Notably, in the US federal government funding for AOUM programming has decreased over the past decade while funding for medically accurate, evidence-based sex education programming has increased but still varies by state and school district (Hall et al. 2016). Efficacy studies offer comprehensive sex education offer promising results. A meta-analysis by Chin and colleagues (2012) found that comprehensive sex education programming was associated with positive outcomes, including greater likelihood of contraception use, as well as less frequent unprotected sex, lower likelihood of adolescent pregnancy, and a lower risk of STI diagnosis (Denford et al. 2017; Lugo-Gil et al. 2016). Comprehensive sex education has also been linked to positive mental health outcomes such as reduced depressive symptomology and enhanced self-esteem (Fernandes and Junnarkar 2019).

LGBTQ representation in sex education

Previous qualitative studies show that AOUM sex education generally excludes mention of lesbian, ga, and bisexual (LGB) identities and relationships (Elia and Eliason 2010b; 2010a; Fisher 2009; Hoefer and Hoefer 2017; Hall and Witkemper 2019; Estes 2017; Hobaica and Kwon 2017; Currin et al. 2017; Pampati et al. 2020), and LGB youth report feeling this type of curriculum teaches them to “expect invisibility” from society (Estes 2017). LGB youth describe AOUM sex education as irrelevant to their informational needs and, as a result, often feel unprepared for sex or discussions about sex and sexuality (Hoefer and Hoefer 2017). When content relevant to sexual orientation and gender identity (SOGI) is encountered in sex education, LGB youth report that representations of LGB people/topics are often framed negatively (e.g., as abnormal, sinful or aberrant) and that peers react with homophobic commentary (Hoefer and Hoefer 2017). LGB women also are more likely than heterosexual women to seek/receive both affirming and disaffirming information from any sex education source (Tabaac et al. 2021).

AOUM messaging exists beyond school settings as young people may seek out and receive sexual health information from parents, peers, media and other sources. Notably, LGB youth describe how sex is often framed as a taboo topic for discussion by other sources as well (Hoefer and Hoefer 2017). In particular, sex education from parents often mirrors AOUM programming in schools and features heteronormative content, conveys interest in sexuality as taboo, and “pushes” heterosexuality as norm (even in interactions where young people have disclosed their own minority gender or sexuality identity; Estes 2017). Internet sources offer an alternative to AOUM, however, but these sources are not necessarily comprehensive, safe or accurate (Estes 2017; Roberts et al. 2020).

Comprehensive sex education varies widely in quality and inclusion of SOGI content, both in USA and elsewhere (Elia & Eliason, 2010a; Rabbitte, 2020). For example, in a case study of Chicago Public Schools’ implementation of SOGI-inclusive comprehensive sex education content (Jarpe-Ratner 2019), the quality, inclusivity and perceived safety of students varied greatly depending on the school, teacher, or class. Furthermore, a focus of procreation as the main purpose of sex and LGB-based stigmatisation also persist in some comprehensive sex education classrooms (Jarpe-Ratner 2019). However, comprehensive sex education curricula that engage with a variety of topics (e.g., SOGI, relationships, STIs, anatomy) have been associated with male high school students’ greater willingness to intervene in LGB name-calling at school (Baams, Dubas, and Van Aken 2017). This in turn can create a more affirming and safer school environment for LGB youth.

The present study and hypotheses

Addressing LGB inclusion in sex education is critical as research indicates that heteronormativity in sex education can adversely impact LGB youth. For instance, LGB youth who perceive sex education content as not inclusive of LGB identities report more anxiety, depression and suicidality in high school (Keiser, Kwon, and Hobaica 2019). However, representation and stigma in sex education, and their associations with particular types of sex education curricula (e.g., AOUM, comprehensive), have not been assessed. This connection is important since LGB youth may benefit more from sex education approaches that include LGB representation, particularly as young people ascribe high importance to seeing others like themselves in sex education material (Jarpe-Ratner 2019).

The goal of the present study was to investigate: how type of sex education curriculum is associated with differences in LGB-affirming (i.e., content that depicts LGB people as natural/normal) or –disaffirming (i.e., content that depicts LGB people as abnormal/sinful) content for young people of different sexual orientations. We also sought to investigate how type of sex education curriculum and the presence of LGB-affirming and -disaffirming content are experienced across different sources (e.g., schools, media) in the USA and by sexual orientation. This study expands on previous work that only examined sexual orientation differences in individual sexual and reproductive health topic exposures in a sample a LGB women (Tabaac et al. 2021).

We hypothesised that LGB youth would be more likely than heterosexual youth to ‘seek/receive’ (i.e., experience) either LGB-affirming or -disaffirming sex education, and that this association would be modified by curriculum type. For example, we expected that receipt of AOUM sex education would be associated with greater odds of reporting LGB-disaffirming and lower odds of reporting LGB-affirming sex education, and that these effects would be larger for LGB youth than for heterosexual youth.

Method

Study procedure and population

Data came from participants in the Growing Up Today Study (GUTS), a longitudinal cohort study, for which enrollment took place in 1996 (GUTS1) and 2004 (GUTS2). At baseline, a total of 27,789 participants were recruited. GUTS consists of participants from all 50 US states, with the most recent questionnaire being administered in 2016. Information on the GUTS study protocol, including enrollment procedures, is published elsewhere (Field et al. 1999). The study protocol was approved by the Institutional Review Boards of the Brigham and Women’s Hospital and the Harvard T.H. Chan School of Public Health.

The present study included participants aged 22–35 years surveyed in 2016. Participants were excluded if they were missing a response for or reported an unsure sexual orientation (n = 4,738); were transgender (baseline sex designated-at-birth and 2016 gender were different, n = 75); and if all information on LGB-affirming and -disaffirming information variables was missing (n = 10,100, primarily due to longitudinal attrition and non-response in the 2016 questionnaire). Transgender participants were excluded due to the small sub-sample size that would not allow for nuanced gender-based analyses and to keep findings generalisable to cisgender sexual minorities. Following exclusions, the final analytical sample consisted of N=12,876 cisgender men and women.

Participant Demographics

In this sample, most of the participants reported they were completely heterosexual without same-sex contact (72%), white (95%), female (66%), and lived in either the Midwest (31%) or Northeast (30%). Complete participant demographics are provided in Table 1.

Table 1.

Frequency of demographics and sex education during adolescence, by sexual orientation (N=12,876)a

| Completely Heterosexual without same-sex contact | Completely Heterosexual with same-sex contact | Mostly Heterosexual | Bisexual | Gay/Lesbian | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

|||||

| (n=9,275, 72%) | (n=466, 4%) | (n=2,402, 19%) | (n=336, 3%) | (n=397, 3%) | |

|

| |||||

| Age in 2016 (range: 22–35 years), Median (IQRb) | 30 (27–32) | 32 (30–33) | 30 (27–32) | 29 (25–32) | 31 (28–32) |

| White race/ethnicity, % (n) | 96 (8,787) | 92 (422) | 94 (2,242) | 96 (320) | 91 (360) |

| Female, % (n) | 63 (5,801) | 73 (339) | 79 (1,902) | 90 (302) | 45 (179) |

| Region | |||||

| Midwest | 32 (3,003) | 27 (123) | 29 (684) | 23 (77) | 25 (97) |

| Northeast | 30 (2,808) | 30 (137) | 30 (728) | 29 (96) | 34 (133) |

| South | 19 (1,760) | 22 (101) | 17 (401) | 17 (58) | 18 (70) |

| West | 18 (1,681) | 22 (103) | 24 (579) | 31 (102) | 24 (94) |

| Sex education topic, % (n) | |||||

| Abstinence-until-marriage sex educationc | 40 (3,687) | 36 (167) | 36 (860) | 40 (133) | 36 (141) |

| Sex refusal sex educationd | 11 (1,062) | 10 (47) | 11 (265) | 13 (43) | 12 (47) |

| Comprehensive sex educationc | 28 (2,570) | 26 (121) | 34 (809) | 32 (109) | 34 (134) |

| Sexuality Topics | |||||

| LGBd people/relationships are normal/natural |

49 (4,133) | 49 (213) | 66 (1,492) | 72 (234) | 64 (247) |

| LGBd people/relationships are abnormal/sinful |

51 (4,377) | 45 (197) | 53 (1,190) | 66 (210) | 72 (279) |

GUTS 1 participants were born 1982–1987, GUTS 2 1987–1994. Age and sexual orientation are reported for year of survey submission. Questions on sex education were retrospectively reported for exposures occurring before age 18.

IQR is “inter-quartile range.”

Abstinence-only until marriage sex education was coded as “yes” if a participant reported seeking/receiving information about “waiting until marriage to have sex while not endorsing seeking/receiving information about “methods of birth control”, “where to get birth control”, “how to use condoms”, and “how to say no to sex.” Sex refusal skills sex education was coded as “yes” if a participant reported seeking/receiving information about “how to say no to sex” while not endorsing seeking/receiving information about “methods of birth control”, “where to get birth control”, “how to use condoms”, and “waiting until marriage to have sex.” Comprehensive sex education was coded as “yes” if a participant reported seeking/receiving information about “how to say no to sex” while endorsing seeking/receiving information about at least one of the following topics: “methods of birth control”, “where to get birth control”, or “how to use condoms.”

LGB is “lesbian, gay, bisexual.”

Measures

Demographics

Age in years in 2016, designated sex at birth (male; female) as reported by mothers at time of study enrollment, race/ethnicity as reported at baseline (white; Black, Indigenous, and people of colour [BIPOC]), region of residence in 2016 (Northeast, Midwest, West, South) and study cohort (GUTS1, GUTS2) were included as covariates. Due to minimal missing data on race/ethnicity (n = 121) and region of residence (n = 41), we used listwise deletion methods.

Sexual orientation

Information on sexual orientation was collected regularly starting in 1999. The sexual orientation item was adapted from the Minnesota Adolescent Health Survey (Remafedi et al. 1992), which assessed feelings of attraction and identity using six mutually exclusive response options: completely heterosexual, mostly heterosexual, bisexual, mostly homosexual, completely homosexual, and unsure. An additional item asked about the sex of sexual partners (male, female, both male and female). Using responses to these two items, we classified study participants as follows: completely heterosexual without same-sex contact (reference); completely heterosexual with same-sex contact (i.e., participants who identified as ‘completely heterosexual’ who also indicated past same-sex contact), mostly heterosexual; bisexual; and lesbian/gay (combination of mostly and completely homosexual subgroups). We used participants’ report of sexual orientation from the same year as the sex education outcomes (2016) and carried forward responses from the most recent previous questionnaire responses if 2016 sexual orientation data were missing.

Sex education.

The 2016 questionnaire included items about the ‘seeking/receipt’ of various sex education topics from different sources by age 17 or younger. Topics included LGB people and relationships as ‘normal’; LGB people and relationships as ‘abnormal/sinful’; how to say no to sex; waiting until marriage to have sex; and contraceptive use (condom use, birth control methods, where to get birth control). Sources for each information type include none, school, church/temple/etc., parent/guardian, peers, media (TV, Internet, magazines), elsewhere, and not sure (coded as missing for ‘abnormal/sinful’ and ‘normal’ topics; n=1,803).

To assess exposure to LGB-affirming and LGB-disaffirming content, two binary variables were created for: sought/received any information that lesbian, gay, and bisexual people/relationships are ‘normal/natural’ (i.e., affirming sex education), and sought/received any information that lesbian, gay, and bisexual people/relationships are abnormal/sinful (i.e., disaffirming sex education) from any source. Sensitivity analyses were conducted to see if modelling ‘not sure’ as a ‘yes’ or ‘no’ category affected analyses, and chi-square and frequency statistics were examined, but there were not meaningful changes when coding was altered. In order to avoid incorrectly inferring what participants meant, the ‘not sure’ responses were left as missing. As sex education items in the 2016 questionnaire were presented as a check-all-that-apply grid, the affirming and disaffirming sex education variables were not mutually exclusive, and participants could report both topics.

To assess the type of sex education curriculum received, we created three variables based on definitions offered by the American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists (ACOG, n.d.) and descriptions of how curricula are usually taught in the USA (Santelli et al. 2017; Chen 2020):

1. Abstinence-only-until-marriage sex education (AOUM) was coded as ‘yes’ if a participant reported seeking/receiving information about ‘waiting until marriage to have sex’ while not endorsing seeking/receiving information about ‘methods of birth control’, ‘where to get birth control,’, ‘how to use condoms,’, or ‘how to say no to sex.’

2. Sex refusal skills sex education (a variation of AOUM sex education) included abstinence-focused sex education that emphasised sex refusal skills (instead of delaying sex until marriage), was coded as ‘yes’ if a participant reported seeking/receiving information about ‘how to say no to sex’ while not endorsing seeking/receiving information about ‘methods of birth control’, ‘where to get birth control’, ‘how to use condoms,’, and ‘waiting until marriage to have sex.’

3. Comprehensive sex education was coded as ‘yes’ if a participant reported seeking/receiving information about ‘how to say no to sex’ while endorsing seeking/receiving information about at least one of the following topics: ‘methods of birth control’, ‘where to get birth control’, or ‘how to use condoms.’

The curriculum types AOUM, sex refusal skills, and comprehensive sex education were all mutually exclusive of each other. Overall, 4,713 (36.6%) participants in the analytical sample did not report any AOUM, sex refusal skills, or comprehensive sex education; these individuals were retained in the “no” reference groups for each variable.

Data analysis

First, proportions, frequencies, means, and interquartile ranges were reported for study variables (Table 1). Then, chi-square analyses were used to examine the association between sexual orientation and the source of abstinence-until-marriage sex education, sex refusal skills sex education, comprehensive sex education, LGB-affirming content, and LGB-disaffirming content (Table 2). Multivariate analyses were conducted by fitting a series of modified Poisson regression models to an identity link and using generalised estimating equations (to account for sibling clusters) with robust standard errors and a compound symmetric working correlation structure (Fitzmaurice, Laird, and Ware 2004).

Table 2.

Frequencies and correlations for source of abstinence-only until marriage, sex refusal skills, comprehensive, LGBa-affirming, LGBa-disaffirming sex education, by sexual orientation (N=12,876)

| Completely Heterosexual with no same-sex partners (Reference) | Completely Heterosexual with same-sex partners | Mostly Heterosexual | Bisexual | Gay/Lesbian | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

|

|

||||||

| (n=9,275, 72%) | (n=466, 4%) | (n=2,402, 19%) | (n=336, 3%) | (n=397, 3%) | p d | |

|

| ||||||

| Source of Abstinence-Only Until Marriage Sex Educationb, % (N) | ||||||

| School | 4 (378) | 5 (21) | 5 (113) | 7 (22) | 7 (28) | .01 |

| Church/Temple/Etc. | 31 (2,916) | 27 (125) | 29 (697) | 30 (102) | 26 (104) | .01 |

| Parent or Guardian | 11 (1,011) | 10 (48) | 8 (195) | 8 (28) | 10 (40) | .002 |

| Peers | 3 (295) | 3 (12) | 2 (45) | 1 (4) | 2 (9) | .003 |

| Media | 1 (137) | 1 (6) | 2 (43) | 3 (10) | 2 (9) | .14 |

| Elsewhere (e.g., club, community center) | 1 (138) | 2 (8) | 2 (46) | 1 (2) | 3 (10) | N/A* |

| Source of Sex Refusal Sex Educationb, % (N) | ||||||

| School | 4 (353) | 3 (15) | 3 (73) | 2 (8) | 3 (12) | .25 |

| Church/Temple/Etc. | <1 (40) | <1 (2) | 1 (16) | 1 (3) | 1 (3) | N/A* |

| Parent or Guardian | 3 (232) | 2 (8) | 2 (48) | 5 (17) | 3 (13) | .008 |

| Peers | 2 (143) | 2 (7) | 2 (56) | 1 (4) | 4 (16) | .0006 |

| Media | 3 (303) | 3 (15) | 3 (67) | 3 (11) | 3 (11) | .80 |

| Elsewhere (e.g., club, community center) | 2 (163) | 2 (7) | 2 (45) | 2 (8) | 3 (10) | .70 |

| Source of Comprehensive Sex Educationb, % (N) | ||||||

| School | 21 (1,922) | 18 (86) | 22 (527) | 18 (62) | 22 (86) | .31 |

| Church/Temple/Etc. | <1 (29) | <1 (1) | 1 (16) | 1 (3) | <1 (1) | N/A* |

| Parent or Guardian | 6 (524) | 6 (30) | 8 (184) | 7 (24) | 8 (31) | .003 |

| Peers | 4 (353) | 5 (23) | 6 (154) | 5 (16) | 4 (16) | <.0001 |

| Media | 5 (496) | 7 (31) | 10 (242) | 11 (37) | 12 (47) | <.0001 |

| Elsewhere (e.g., club, community center) | 1 (78) | 2 (8) | 1 (32) | 1 (5) | 3 (12) | N/A* |

| Source of LGBa-Affirming Contentc, % (N) | ||||||

| School | 17 (1,476) | 15 (64) | 20 (436) | 16 (50) | 19 (70) | .05 |

| Church/Temple/Etc. | 2 (196) | 2 (9) | 4 (96) | 4 (13) | 3 (11) | <.0001 |

| Parent or Guardian | 23 (1,973) | 27 (116) | 36 (803) | 35 (111) | 24 (88) | <.0001 |

| Peers | 24 (2,019) | 27 (118) | 41 (919) | 43 (137) | 39 (146) | <.0001 |

| Media | 30 (2,542) | 29 (123) | 42 (942) | 46 (144) | 50 (189) | <.0001 |

| Elsewhere (e.g., club, community center) | 5 (457) | 7 (32) | 11 (234) | 15 (47) | 13 (50) | <.0001 |

| Source of LGBa-Disaffirming Contentc, % (N) | ||||||

| School | 12 (1,025) | 12 (51) | 13 (281) | 19 (59) | 25 (93) | <.0001 |

| Church/Temple/Etc. | 40 (3,477) | 36 (160) | 39 (863) | 50 (157) | 50 (192) | <.0001 |

| Parent or Guardian | 21 (1,775) | 18 (81) | 17 (381) | 27 (83) | 24 (91) | <.0001 |

| Peers | 12 (1,022) | 10 (45) | 15 (341) | 20 (62) | 23 (88) | <.0001 |

| Media | 13 (1,086) | 10 (45) | 19 (412) | 25 (77) | 37 (143) | <.0001 |

| Elsewhere (e.g., club, community center) | 4 (346) | 4 (18) | 6 (131) | 12 (36) | 21 (79) | <.0001 |

Denotes cell sizes too small (=<5) to compute a chi-square statistic.

LGB is “lesbian, gay, bisexual.”

Abstinence-only until marriage sex education was coded as “yes” if a participant reported seeking/receiving information about “waiting until marriage to have sex while not endorsing seeking/receiving information about “methods of birth control”, “where to get birth control”, “how to use condoms”, and “how to say no to sex.” Sex refusal skills sex education was coded as “yes” if a participant reported seeking/receiving information about “how to say no to sex” while not endorsing seeking/receiving information about “methods of birth control”, “where to get birth control”, “how to use condoms”, and “waiting until marriage to have sex.” Comprehensive sex education was coded as “yes” if a participant reported seeking/receiving information about “how to say no to sex” while endorsing seeking/receiving information about at least one of the following topics: “methods of birth control”, “where to get birth control”, or “how to use condoms.”

Participants reported all of the sex education sources they encountered, so some percentages sum to more than 100%.

Pearson’s chi-square tests were used to calculate the p-value for dichotomous outcomes.

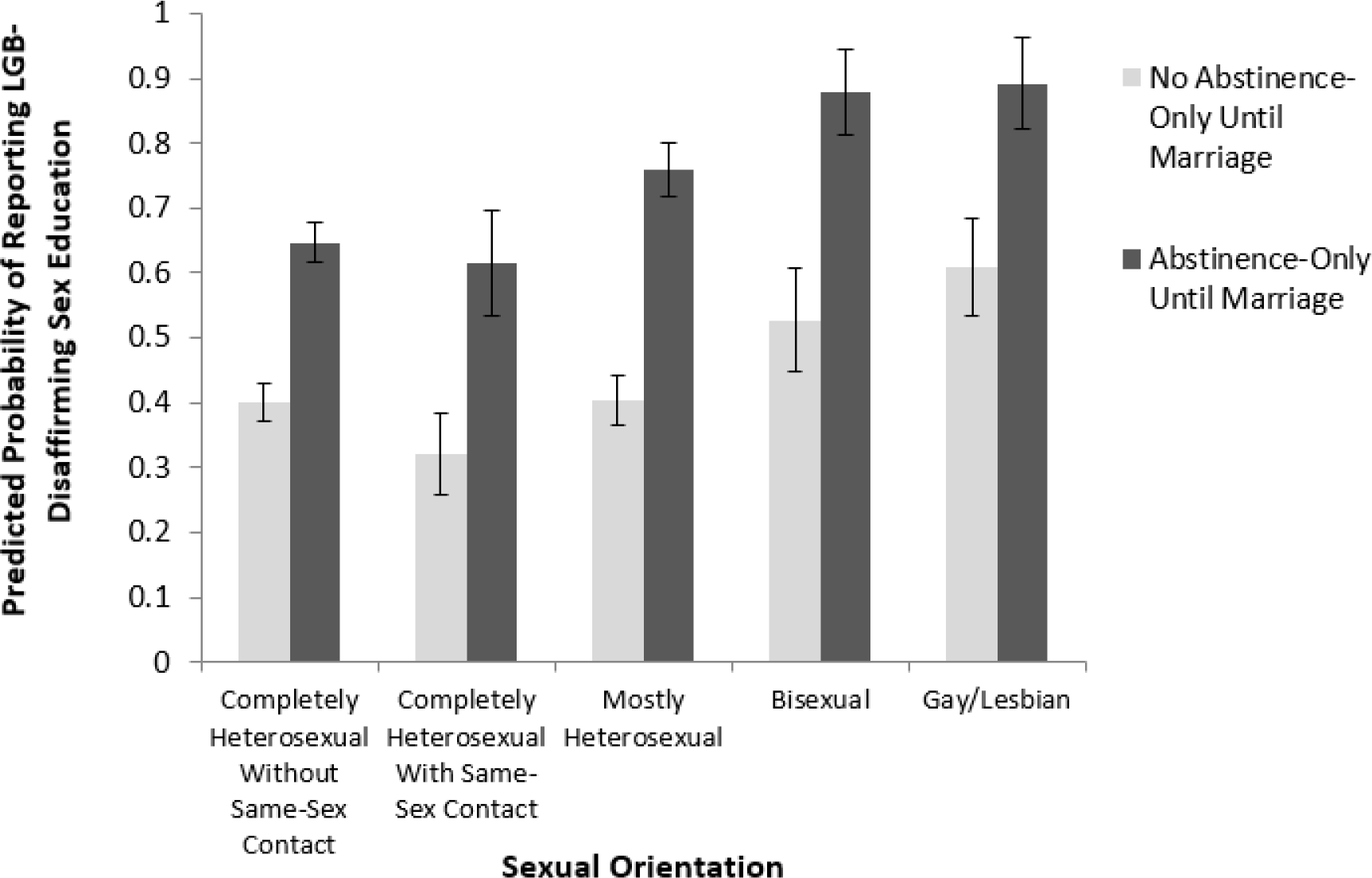

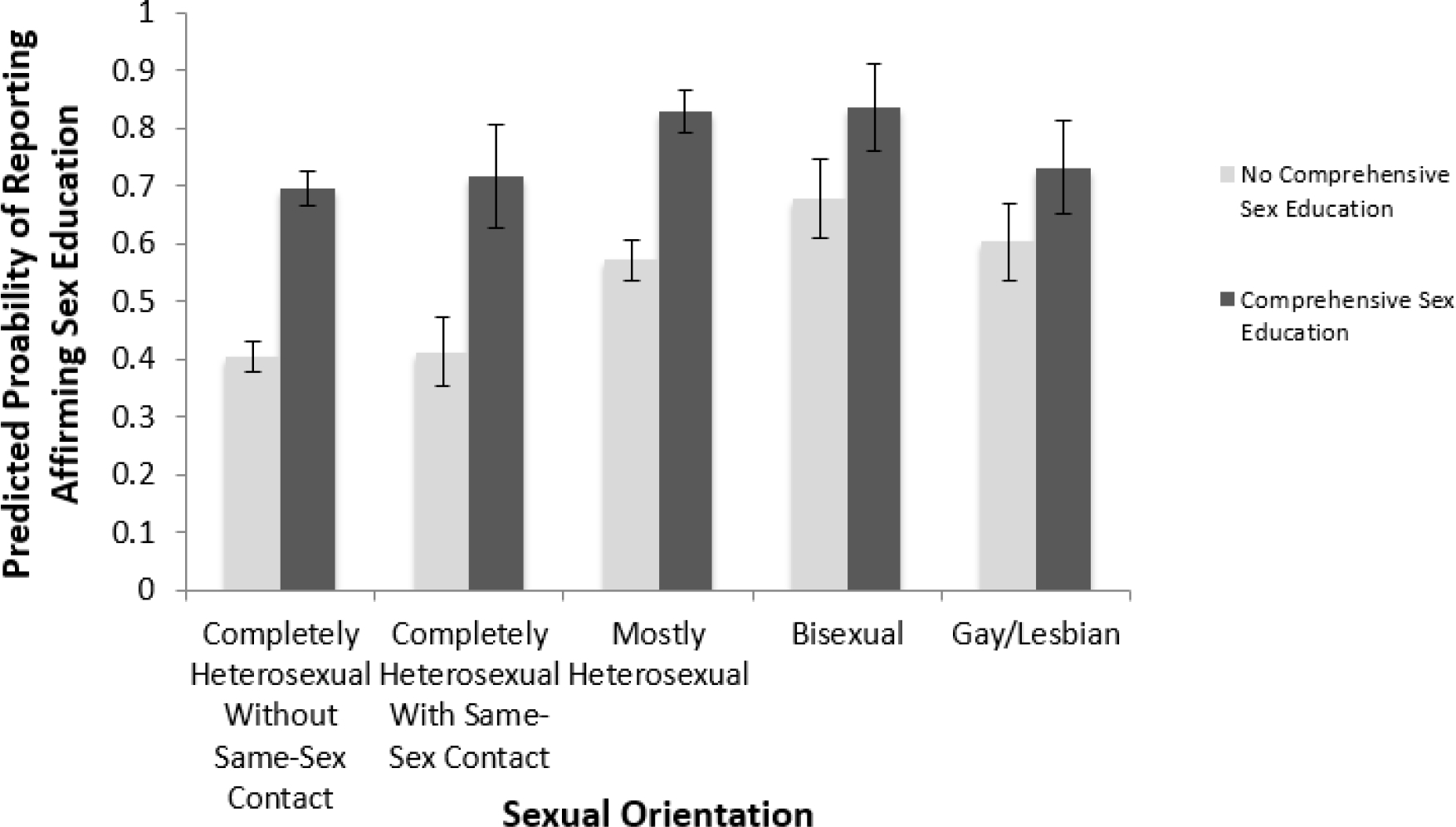

With these methods, we examined associations between sexual orientation, type of sex education curriculum, and probability of seeking/receiving affirming or disaffirming content (Table 3). Finally, in order to examine whether type of sex education curriculum (AOUM, sex refusal skills, comprehensive) modified the association between sexual orientation and seeking/receipt of LGB-affirming or -disaffirming content, interactions terms were added to each regression model (non-significant interactions not reported; see online supplemental tables 1–3). For significant interactions, we then modelled their predicted probabilities (Figures 1–2). All analyses were conducted in SAS version 9.4 (“SAS Statistical Software, Release 9.4,” n.d.).

Table 3.

Adjusteda modified Poisson models of the associations between sexual orientation and exposure to abstinence-only and comprehensive sex education on LGB-affirming and -disaffirming content (N=12,876)

| Outcome: Affirming Sex Education | |||

| Model | RDb | (95% CI) | p c |

|

| |||

| Sexual Orientation | |||

| Completely Heterosexual with No Same-Sex Partners (Ref.) | -- | -- | -- |

| Completely Heterosexual with Same-Sex Partners | 0.05 | (0.001, 0.10) | .047 |

| Mostly Heterosexual | 0.18 | (0.15, 0.20) | <.0001 |

| Bisexual | 0.23 | (0.17, 0.28) | <.0001 |

| Gay/Lesbian | 0.12 | (0.06, 0.18) | <.0001 |

| Abstinence-Only Until Marriage Sex Education | −.04 | (−0.06, −0.02) | <.0001 |

| Sex Refusal Sex Education | 0.10 | (.07, .13) | <.0001 |

| Comprehensive Sex Education | 0.27 | (0.25, 0.29) | <.0001 |

|

| |||

| Outcome: Disaffirming Sex Education | |||

| Model | RDb | (95% CI) | p c |

|

| |||

| Sexual Orientation | |||

| Completely Heterosexual with No Same-Sex Partners (Ref.) | -- | -- | -- |

| Completely Heterosexual with Same-Sex Partners | −0.06 | (−0.11, −0.01) | .02 |

| Mostly Heterosexual | 0.04 | (0.01, 0.07) | .002 |

| Bisexual | 0.17 | (0.12, 0.23) | <.0001 |

| Gay/Lesbian | 0.21 | (0.15, 0.26) | <.0001 |

| Abstinence-Only Until Marriage Sex Education | 0.27 | (0.25, 0.28) | <.0001 |

| Sex Refusal Sex Education | 0.01 | (−.02, 0.04) | .35 |

| Comprehensive Sex Education | 0.05 | (0.03, 0.07) | <.0001 |

Note. LGB=lesbian, gay, bisexual; RD=risk difference; CI=confidence interval. Individual adjusted models were run with sexual orientation (ref: completely heterosexual with no same-sex partners), abstinence-until-marriage sex education (ref: none), sex refusal skills sex education (ref: none), and comprehensive sex education (ref: none) as predictors in their respective model.

Models adjusted for race/ethnicity, study cohort, geographic region of residence, and age.

Bolded values indicate relative difference ratios with significance at p < .05 and 95% confidence intervals that do not cross 0.

Values of p estimated by log-linear generalised estimating equation regression. Completely heterosexual without same-sex contact is the reference group.

Figure 1.

Predicted probability of exposure to disaffirming sex education by “abstinence-only until marriage” sex education and sexual orientation (p<.0001); “abstinence-only until marriage” sex education was coded as “yes” if a participant endorsed seeking/receiving information on “waiting until marriage to have sex” while not reporting “methods of birth control”, “where to buy birth control”, “how to use condoms”, or “how to say no to sex”

Figure 2.

Predicted probability of exposure to affirming sex education by comprehensive sex education and sexual orientation (p=.01); “comprehensive sex education” was coded as “yes” if participants endorsed “how to say no to sex” and at least one birth control information variable

Results

Source of sex education

Table 2 displays frequencies and unadjusted chi-square comparisons for curriculum and content by source of sex education. Overall, AOUM was reported most frequently in religious institutions, followed by parents/guardians and schools. All LGB subgroups were more likely than completely heterosexuals with no same-sex contact to report receiving AOUM sex education from schools (p=.01) and slightly less likely to report receiving AOUM sex education from religious institutions (p=.01) or parents/guardians (ps=.002). Sex refusal sex education was rarely reported by participants, but was most commonly reported from schools, parents and the media. Schools were the most commonly reported source of comprehensive sex education for all sexual orientation subgroups, though frequency did not differ by sexual orientation.

Sources of LGB-affirming content most frequently reported were media and peers. In contrast, religious institutions were the most frequently reported source of LGB-disaffirming content. Further, both bisexual and gay/lesbian adolescents were most likely to report receiving disaffirming sex education from schools or religious institutions (p<.0001); gay/lesbian adolescents were twice as likely as completely heterosexuals with no same-sex contact to report receiving LGB-disaffirming content from schools or from peers (p<.0001). Notably, gay/lesbian adolescents were also nearly 3–5 times as likely as completely heterosexuals with no same-sex contact to report receiving LGB-disaffirming content from media or elsewhere (ps<.0001).

Multivariate analyses of LGB-affirming and -disaffirming content

Modified Poisson regression models adjusted for age, race/ethnicity, sex and region were examined in order to assess overall associations between sexual orientation and sex education (Table 3). Risk differences (RD) with 95% confidence intervals (CI) were reported.

Completely heterosexuals with same-sex contact (RD=0.05, 95% CI [.001, .10]), mostly heterosexual (RD=0.18, 95% CI [.15, .20]), bisexual (RD=0.23, 95% CI [.17, .28]), and gay/lesbian (RD=.12, 95% CI [.06, .18]) participants were all significantly more likely than completely heterosexual referents to report encountering LGB-affirming content from any source during adolescence. Similarly, mostly heterosexual (RD=.04, 95% CI [.01, .07]), bisexual (RD=.17, 95% CI [.12, .23]), and gay/lesbian (RD=.21, 95% CI [.15, .26]) participants were more likely than completely heterosexuals with no same-sex contact to report LGB-disaffirming content during adolescence, while completely heterosexuals with same-sex contact (RD=−0.06, 95% CI [−0.11, −0.01]) were slightly less likely to report this type of content.

For all participants, receipt of AOUM sex education was negatively associated with LGB-affirming content (RD=−0.04, 95% CI [−0.06, −0.02]), and positively associated with LGB-disaffirming content (RD=0.27, 95% CI [0.25, 0.28]). In contrast, sex refusal skills sex education was positively associated with LGB-affirming content (RD=0.10, 95% CI [0.07, 0.13]), but did not show a statistically significant relationship with LGB-disaffirming content. Finally, participants who reported comprehensive sex education were more likely than those without comprehensive sex education to report encountering LGB-affirming content (RD=0.27, 95% CI [0.25, 0.29]).

Figure 1 displays the predicted probability of being exposed to LGB-disaffirming content, stratified jointly by participants’ sexual orientation and whether they received AOUM sex education. Within each sexual orientation group, LGB-disaffirming content was more likely to be reported by participants who reported AOUM sex education than those who did not. These associations were further by sexual orientation, with mostly heterosexual, bisexual, and gay/lesbian participants being significantly more likely than completely heterosexuals with no same-sex contact to report LGB-disaffirming content. Overall, we estimate that LGB young adults who reported AOUM sex education during adolescence were much more likely to report LGB-disaffirming content than other participants.

Finally, within all sexual orientation groups, participants who reported comprehensive sex education were more likely than those without comprehensive sex education to seek/receive LGB-affirming content (Figure 2). This pattern was also strengthened by sexual orientation: mostly heterosexual and bisexual participants who reported comprehensive sex education were significantly more likely to report LGB-affirming content than completely heterosexuals with no same-sex contact. Completely heterosexuals with same-sex contact and gay/lesbian participants who reported comprehensive sex education did not significantly differ from completely heterosexuals with no same-sex contact.

No other interactions between sexual orientation and type of sex education on the probability of reporting LGB-affirming/-disaffirming content were significant (results not shown).

Discussion

Our first finding was that comprehensive sex education and sex refusal skills sex education were associated with a greater likelihood of receiving LGB-affirming content exposure. In the USA, as well as countries including the UK and Australia, comprehensive sex education has been suggested but not consistently and explicitly associated with greater likelihood of LGB-affirming content exposure (Abbott, Ellis, & Abbott 2015; Elia & Eliason 2010b; Formby 2011; Grant & Nash 2019). Our second key finding was that AOUM sex education was associated with greatly increased likelihood of receiving LGB-disaffirming content. This finding is congruent with multiple qualitative studies that describe AOUM as stigmatising of LGB identities (Chen 2020; Currin et al. 2017; Elia & Eliason 2010a, 2010b; Estes 2017; Fisher 2009; Hall & Witkemper 2019; Hobaica & Kwon 2017; Hoefer & Hoefer 2017). That this association varied among different LGB groups is a novel finding and may be due to to differences in both memory saliency as well as perceptual differences between heterosexual and LGB youth in their sex education experiences (Jarpe-Ratner 2019). Additional work to identify how to make sexual health content not only inclusive, but memorable, to LGBTQ students is warranted.

We also explored differences in seeking/receipt of each type of sex education by both sexual orientation and source. Overall, schools were the most commonly reported source of comprehensive sex education for all sexual orientation subgroups, which is unsurprising given the USA’s historical focus on school-based sex education policy (Santelli et al. 2017) and the amount of time young people may spend in school. In addition, religious institutions were the most commonly reported source of AOUM sex education across all sexual orientation subgroups, which supports previous research that found that New Zealand students who attended religious schools were more likely than those attending non-religious schools to receive sex education programming discussing abstinence (Ellis & Bentham 2021). Since our study was unable to disambiguate whether the relationship between LGB-affirming content exposure and curriculum type was driven by source, future research is needed to expand on our finding and determine if certain sources (like schools) have a greater effect on LGB students’ sex education exposures and related health outcomes.

We also examined differences in LGB-affirming/-disaffirming content by source. In this study, the most common sources of affirming sex education were media and peer sources, which may indicate school-based AOUM and comprehensive sex education are currently insufficient for LGB youth. In other words, consistent with descriptive qualitative research, even though young may receive more comprehensive content in schools (Jarpe-Ratner 2019; Estes 2017), they rely on other sources such as media for LGB-applicable content (Estes 2017; Flanders et al. 2017). LGB-affirming content is often excluded or inadequate in relation to students’ needs (Ellis & Bentham 2021; Ezer, Kerr, & Fisher 2019; Shannon & Smith 2015; Stonewall 2017). LGB-disaffirming sex education was most common among religious sources, which is unsurprising given the traditional moral and religious framing of abstinence in US sex education policy (Santelli et al. 2017), as well as the homophobia reflected in our item “LGB people/relationships are abnormal and sinful.”

Multivariate findings shed light on how sexual orientation adds nuance to these relationships among sexuality, sex education topic, and curriculum. For instance, both comprehensive sex education and sex refusal skills sex education, were both associated with participants of all sexual orientations being more likely to seek/receive affirming LGB content. This finding is perhaps unsurprising, given that a hallmark of comprehensive sexuality education is its breadth of content and its normalization of diversity in human sexuality (ACOG n.d.). Findings also indicate that the inclusion of LGB-affirming content does not necessarily indicate the inclusion of other topics such as contraceptive use. This finding is novel, as existing research has not examined associations between curricula type (broken down by inclusion of contraceptive topics) and type of LGB content.

Further, when compared to completely heterosexual referents in effect modification models, the association between comprehensive sex education and exposure to LGB-affirming sex education was largest for mostly heterosexual and bisexual participants while gay/lesbian participants did not differ from referents. This may be due in part to content relevancy and expectations of gay/lesbian youth influencing recall bias, such that if past experiences or expectations of LGB-inclusivity are low, gay/lesbian youth may be less likely than other sexual minorities (who may be attracted to multiple genders) to engage with comprehensive sex education curricula, or find it as useful relative to their sexual health questions. In contrast, there were sexual orientation differences when examining the association between AOUM sex education exposure and LGB-disaffirming information, such that youth of any sexual orientation who had received AOUM sex education also reported exposure to LGB-disaffirming content, and this association was stronger for mostly heterosexual, bisexual, and gay/lesbian.

Limitations and Future Directions

This study has a number of limitations. First, the sample was over 90% white and findings do not reflect the sex education experiences of LGB youth of colour in the USA, who contend with systemic racism in educational settings that often results in alienation, negative stereotyping, biased interactions with sex education, and lack of representation in most sources (Hoefer and Hoefer 2017). Second, gender minority experiences were not represented in our questionnaire and gender minority individuals were very few in our sample, thus we cannot generalise from our research to transgender and gender minority topics or populations. Third, data were self-reported and recalled by adult participants (some reporting ten years into the past), thus estimates may be under- or over-reported due to recall bias or may reflect older variants of sex education curricula and messaging. Furthermore, the sex education questionnaire combined ‘seeking/receiving’ into a single construct, thus we were unable to disentangle self-reported seeking and receiving of sex education. Fourth, differences by sexual orientation may in part be due to self-report bias: LGB sex education content may be more salient and easier for sexual minorities to recall. Fifth, history effects may be present for older participants (e.g., those whose sex education experiences preceded the 2013 same-sex marriage ruling by the US Supreme Court and/or those whose sex education took place before the development and implementation of comprehensive sex education curricula; and those who experienced older versions of AOUM curricula). Future research seeking to disentangle the potential causal mechanisms present in these history effects, like public policy, religious, and other environmental factors would shed more light on such influences.

Conclusion

The findings from this study lend further support to the literature that emphasises the benefits of comprehensive sex education. The link between comprehensive sexuality education and LGB-affirming content further supports how LGB youth may benefit from comprehensive sexual health education curricula more than other approaches. Stigma against sexual minorities is one of the key drivers of health disparities among LGB youth, and comprehensive sexuality education may be an important tool for combatting that stigma among school age youth. Future research exploring the links among potential causal mechanisms (e.g., policy, religious, and other environmental factors) and health-related outcomes (e.g., sexual health) is needed in order to quantify the why and how sex education exposure is impactful for LGB students. Moving forward, striving to name and evaluate the core components of an inclusive, comprehensive sexuality education curriculum is essential so that schools, media, parents and other sources of sexual health information can be better equipped to address the needs of students with diverse sexual orientations.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

This research was supported by grant U01 HL145386 from the National Heart, Lung, and Blood Institute of the US National Institutes of Health, and by grant F32HD100081 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development of the US National Institutes of Health.

The first author (AT) was supported by grant F32HD100081 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, US National Institutes of Health. SBA was supported by grants R01HD057368 and R01HD066963 from the Eunice Kennedy Shriver National Institute of Child Health and Human Development, US National Institutes of Health, and by grants T71MC00009 and T76MC00001 from the Maternal and Child Health Bureau, Health Resources and Services Administration, US Department of Health and Human Services. BMC was supported by grant MRSG CPHPS 130006 from the American Cancer Society.

Footnotes

Disclaimer

The findings and conclusions in this report are those of the authors and do not necessarily represent the official position of the US Centers for Disease Control and Prevention or the views of the US National Institutes of Health.

References

- Abbott Keeley, Ellis Sonja, & Abbott Rachel. 2015. “We Don’t Get Into All That”: An Analysis of How Teachers Uphold Heteronormative Sex and Relationship Education.” Journal of Homosexuality 62 (12): 1638–1659. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. (n.d.). Comprehensive Sexuality Education. Retrieved March 26, 2020, from https://www.acog.org/clinical/clinical-guidance/committee-opinion/articles/2016/11/comprehensive-sexuality-education

- Baams Laura, Dubas Judith Semon, and Van Aken Marcel A G. 2017. “Comprehensive Sexuality Education as a Longitudinal Predictor of LGBTQ Name-Calling and Perceived Willingness to Intervene in School.” Journal of Youth and Adolescence 46: 931–42. 10.1007/s10964-017-0638-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC). 2014. “Results from the School Health Policies and Practices Study 2014.” Retrieved on March 26, 2020, from https://www.cdc.gov/healthyyouth/data/shpps/pdf/shpps-508-final_101315.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Chen Xiyuan. 2020. No Turning Back: Exploring Sex Education in the United States. Ontario: University of Windsor. [Google Scholar]

- Chin Helen B., Sipe Theresa Ann, Elder Randy, Mercer Shawna L., Chattopadhyay Sajal K., Jacob Verughese, Wethington Holly R., et al. 2012. “The Effectiveness of Group-Based Comprehensive Risk-Reduction and Abstinence Education Interventions to Prevent or Reduce the Risk of Adolescent Pregnancy, Human Immunodeficiency Virus, and Sexually Transmitted Infections: Two Systematic Reviews for the Guide to Community Preventive Services.” American Journal of Preventive Medicine 42 (3): 272–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Currin Joseph M., Hubach Randolph D., Durham André R., Kavanaugh Katherine E., Vineyard Zachary, and Croff Julie M.. 2017. “How Gay and Bisexual Men Compensate for the Lack of Meaningful Sex Education in a Socially Conservative State.” Sex Education 17 (6): 667–81. [Google Scholar]

- Denford Sarah, Abraham Charles, Campbell Rona, and Busse Heide. 2017. “A Comprehensive Review of Reviews of School-Based Interventions to Improve Sexual-Health.” Health Psychology Review 11 (1): 33–52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Elia John P., and Eliason Mickey. 2010a. “Discourses of Exclusion: Sexuality Education’s Silencing of Sexual Others.” Journal of LGBT Youth 7 (1): 29–48. [Google Scholar]

- Elia John P., and Eliason Mickey J.. 2010b. “Dangerous Omissions: Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage School-Based Sexuality Education and the Betrayal of LGBTQ Youth.” American Journal of Sexuality Education 5 (1): 17–35. [Google Scholar]

- Ellis Sonja J., and Bentham Ryan M.. 2021. “Inclusion of LGBTIQ Perspectives in School-Based Sexuality Education in Aotearoa/New Zealand: An Exploratory Study. Sexuality, Society, and Learning 21 (6): 708–722. [Google Scholar]

- Epps Beth, Markowski Marianne, & Cleaver Karen. 2021. “A Rapid Review and Narrative Synthesis of the Consequences of Non-Inclusive Sex Education in UK Schools on Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Transgender, and Questioning Young People.” The Journal of School Nursing. 10.1177/10598405211043394 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Estes Michelle L. 2017. “‘If There’s One Benefit, You’re Not Going to Get Pregnant’: The Sexual Miseducation of Gay, Lesbian, and Bisexual Individuals.” Sex Roles 77: 615–27. [Google Scholar]

- Ezer Paulina, Kerr Lucille, & Fisher Christopher M.. (2019). “Australian Students’ Experiences of Sexuality Education at School.” Sex Education 19 (5): 597–613. [Google Scholar]

- Fernandes Danielle, and Junnarkar Mohita. 2019. “Comprehensive Sex Education: Holistic Approach to Biological, Psychological and Social Development of Adolescents.” International Journal School Health 6 (2): 63959. [Google Scholar]

- Field Alison E, Camargo Carlos A, Taylor C Barr, Berkey Catherine S, Frazier Lindsay, Gillman Matthew W, and Colditz Graham A. 1999. “Overweight, Weight Concerns, and Bulimic Behaviors among Girls and Boys.” Journal of the American Academy of Child & Adolescent Psychiatry 38 (6): 754–60. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher CM. 2009. “Queer Youth Experiences with Abstinence-Only-until-Marriage Sexuality Education: ‘I Can’t Get Married so Where Does That Leave Me?’” Journal of LGBT Youth 6 (1): 61–79. [Google Scholar]

- Fitzmaurice Garrett M., Laird Nan M., and Ware James H.. 2004. Applied Longitudinal Analysis. Wiley Series in Probability and Statistics. Hoboken, N.J.: John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Flanders Corey E., Pragg Lauren, Dobinson Cheryl, and Logie Carmen. 2017. “Young Sexual Minority Women’s Use of the Internet and Other Digital Technologies for Sexual Health Information Seeking.” Canadian Journal of Human Sexuality 26 (1): 17–25. [Google Scholar]

- Formby Eleanor. 2011. “Sex and Relationships Education, Sexual Health, and Lesbian, Gay and Bisexual Sexual Cultures: Views from Young People.” Sex Education 11 (3): 255–266. [Google Scholar]

- Goldfarb Eva S., and Lieberman Lisa D.. 2021. “Three Decades of Research: The Case for Comprehensive Sex Education.” Journal of Adolescent Health 68 (1): 13–27. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grant Ruby, and Nash Meredith. 2019. “Education Queer Sexual Citizens? A Feminist Exploration of Bisexual and Queer Young Women’s Sex Education in Tasmania, Australia.” Sex Education 19 (3): 313–328. [Google Scholar]

- Hall William, and Witkemper Kristen. 2019. “State Policy on School-Based Sex Education: A Content Analysis Focused on Sexual Behaviors, Relationships, and Identities.” American Journal of Health Behavior 43 (3): 506–519. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hall Kelli Stidham, Jessica McDermott Sales Kelli A. Komro, and Santelli John. 2016. “The State of Sex Education in the United States.” Journal of Adolescent Health 58 (6): 595–597. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hobaica Steven, and Kwon Paul. 2017. “‘This Is How You Hetero:’ Sexual Minorities in Heteronormative Sex Education.” American Journal of Sexuality Education 12 (4): 423–50. [Google Scholar]

- Hoefer Sharon E., and Hoefer Richard. 2017. “Worth the Wait? The Consequences of Abstinence-Only Sex Education for Marginalized Students.” American Journal of Sexuality Education, 1–20. 10.1080/15546128.2017.1359802. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Jarpe-Ratner Elizabeth. 2019. “How Can We Make LGBTQ+-Inclusive Sex Education Programmes Truly Inclusive? A Case Study of Chicago Public Schools’ Policy and Curriculum.” Sex Education 20 (3): 283–299. [Google Scholar]

- Jones Tiffany M., and Hillier Lynne. 2012. “Sexuality education school policy for Australian GLBTIQ students.” Sex Education 12 (4): 437–454. [Google Scholar]

- Keiser Gregory H., Kwon Paul, and Hobaica Steven. 2019. “Sex Education Inclusivity and Sexual Minority Health: The Perceived Inclusivity of Sex Education Scale.” American Journal of Sexuality Education 14 (3): 388–415. [Google Scholar]

- Kirby Douglas, Laris BA, and Rolleri Lori. 2005. “Impact of Sex and HIV Education Programs on Sexual Behaviors of Youth in Developing and Developed Countries.” Retrieved December 10th, 2020, from http://www.ibe.unesco.org/fileadmin/user_upload/HIV_and_AIDS/publications/DougKirby.pdf

- Kirby Douglas. 2007. “Emerging Answers 2007: Research Findings on Programs to Reduce Teen Pregnancy and Sexually Transmitted Diseases. Full Report.” Retrieved March 26, 2020, from https://powertodecide.org/sites/default/files/resources/primary-download/emerging-answers.pdf

- Leung Hildie, Shek Daniel TL, Leung Edvina, and Shek Esther YW. 2019. “Development of Contextually-relevant Sexuality Education: Lessons from a Comprehensive Review of Adolescent Sexuality Education Across Cultures.” International Journal of Research in Public Health 20 (16): 621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lugo-Gil Julieta, Lee Amanda, Vohra Divya, Adamek Katie, Lacoe Johanna, and Goesling Brian. 2016. “Updated Findings from the HHS Teen Pregnancy Prevention Evidence Review: July 2014 through August.” Retrieved on March 26, 2020, from https://tppevidencereview.youth.gov/pdfs/Summary_of_findings_2015.pdf

- Pampati Sanjana, Johns Michelle M., Szucs Leigh E., Bishop Meg D., Mallory Allen B., Barrios Lisa C., and Russell Stephen T.. 2020. “Sexual and Gender Minority Youth and Sexual Health Education: A Systematic Mapping Review of the Literature.” Journal of Adolescent Health 68 (6): 1040–1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rabbitte Maureen. 2020. “Sex Education in Scool, Are Gender and Sexual Minority Youth Included?: A Decade in Review.” American Journal of Sexuality Education 15 (4): 530–542. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Remafedi Gary, Resnick Michael, Blum Robert, and Harris Linda. 1992. “Demography of Sexual Orientation in Adolescents.” Pediatrics 89 (4): 714–21. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Roberts Calpurnyia, Shiman Lauren J., Dowling Erin A., Tantay L, Masdea Jennifer, Pierre Jennifer, Lomax Deborah, and Bedell Jane. 2020. “LGBTQ+ Students of Colour and Their Experiences and Needs in Sexual Health Education: ‘You Belong Here Just as Everybody Else.’” Sex Education 20 (3): 267–282. [Google Scholar]

- Santelli John, Ott Mary A., Lyon Maureen, Rogers Jennifer, Summers Daniel, and Schleifer Rebecca. 2006. “Abstinence and abstinence-only education: A review of U.S. policy and programs.” Journal of Adolescent Health 38: 72–81. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Santelli John S., Kantor Leslie M., Grilo Stephanie A., Speizer Ilene S., Lindberg Laura D., Heitel Jennifer, Schalet Amy T., et al. 2017. “Abstinence-Only-Until-Marriage: An Updated Review of U.S. Policies and Programs and Their Impact.” Journal of Adolescent Health 61: 273–280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- “SAS Statistical Software, Release 9.4.” n.d. Cary, NC: SAS Institute Inc. [Google Scholar]

- Shannon Barrie, & Smith Stephen J.. 2015. “A lot More to Learn than Where Babies Come From”: The Controversy, Language and Agenda Setting in the Framing of School-based Sexuality Education Curricula in Australia. Sex Education 15 (6): 641–654. [Google Scholar]

- “Social Security Act §510 Separate Program for Abstinence Education.” 1996. Social Security Administration. United States. 1996. Retrieved on March 26, 2020, from https://www.ssa.gov/OP_Home/ssact/title05/0510.htm. [Google Scholar]

- Stonewall. 2017. “School Report: The Experiences of Lesbian, Gay, Bi, and Trans Young People in Britain’s Schools in 2017.” Retrieved on December 10th, 2021, from https://www.stonewall.org.uk/sites/default/files/the_school_report_2017.pdf

- Tabaac Ariella R., Haneuse Sebastien, Johns Michelle, Tan Andy S.L., Austin S. Bryn, Potter Jennifer, Lindberg Laura, and Charlton Brittany M.. 2021. “Sexual and Reproductive Health Information: Disparities Across Sexual Orientation Groups in Two Cohorts of US Women.” Sexuality Research & Social Policy 18: 612–620. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Weaver Heather, Smith Gary, and Kippax Susan. 2005. “School-Based Sex Education Policies and Indicators of Sexual Health among Young People: A Comparison of the Netherlands, France, Australia and the United States.” Sex Education 5 (2): 171–88. [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.