Abstract

Live Ixodes ricinus ticks attached to humans residing in Germany were examined for borreliae by dark-field microscopy and PCR. Borrelia species were identified by 16S rRNA sequence analysis, which showed the presence of several species, some not yet defined, and a high prevalence of multiply infected ticks.

Lyme disease is a multisystem disorder involving the skin, joints, heart, and nervous system (1, 6, 20, 21). The etiological agent is a spirochete species complex, Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, which is transmitted via infected ticks of the Ixodes ricinus species complex (5, 17). B. burgdorferi sensu lato has been found in other ticks, as well, like Ixodes hexagonus, Ixodes canisuga, and Dermacentor reticulatus (9–12), whose epidemiological relevance to human Lyme disease transmission is not entirely clear at the moment.

European B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates have been divided into several genospecies based on phenotypic analysis, as well as sero- and genotyping, i.e., B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, the predominant species found in North America, Borrelia afzelii, and Borrelia garinii (3, 13, 16, 19, 25, 26). There is some evidence that this division is of relevance to the clinical presentation of Lyme disease in Europe: several studies have revealed an association between the presence of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto and arthritis and between B. afzelii and acrodermatitis chronica atrophicans (23). This picture, however, is still not complete, since other B. burgdorferi sensu lato isolates, VS116 and PotiB2, that cannot easily be attributed to the three known pathogenic species and whose pathological relevance is currently completely unclear have recently been described (18, 22). Accordingly, the prevalence of the different genospecies of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in infected ticks should be the prime determinant for the risk of acquiring Lyme disease and its clinical presentation.

We therefore analyzed live ticks (nymphal, larval, and adult stages), which had been found attached to human skin and submitted by patients during the period 1995 to 1996 from all parts of Lower Saxony, Germany, for the presence of four genospecies of B. burgdorferi sensu lato, i.e. B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii, B. garinii, and isolate VS116. (B. afzelii NE 632 [7] was kindly donated by L. Gern, Neuchatel, Switzerland, B. garinii N 34 was donated [2] by G. Baranton, Paris, France, B. burdorferi sensu stricto B31 [4] was donated by W. Burgdorfer, Hamilton, Mont., and VS116 [18] was donated by O. Peter, Sion, Switzerland.) The ticks were identified to the species level by standard morphological criteria. Altogether, 2,421 ticks, of which the overwhelming majority belonged to the species I. ricinus, had been submitted for analysis (2,399 I. ricinus, 11 I. hexagonus, 6 Rhicicephalus sanguineus, 2 Dermacentor marginatus, 1 D. reticulatus, 1 Amblyomma cajannense, and 1 Argas reflexus tick), but only some of these (1,654 ticks, all of the I. ricinus species, confirming that this tick is the predominant vector for human Lyme disease) were still alive on arrival and were included in this study.

To determine Borrelia infection of the ticks, the midgut of each tick was removed under a stereomicroscope and homogenized in a 0.9% NaCl solution (ca. 100 μl for larvae, 150 μl for nymphs, and 300 μl for engorged adults). Ten microliters of this homogenate was then quantitatively analyzed for the presence of borreliae by dark-field microscopy. One hundred fifty-three tick homogenates (9.3%) were found to be infected by Borrelia species, with numbers ranging from 1 to >3,000 borreliae per 10-μl aliquot. One hundred nineteen homogenates were further analyzed by PCR (see below); 34 homogenates were excluded from the analysis due to insufficient material (mainly larval stages of I. ricinus). The final sample collection consisted of borrelia-positive midgut homogenates from 61 adults, 57 nymphs, and 1 larval stage of I. ricinus.

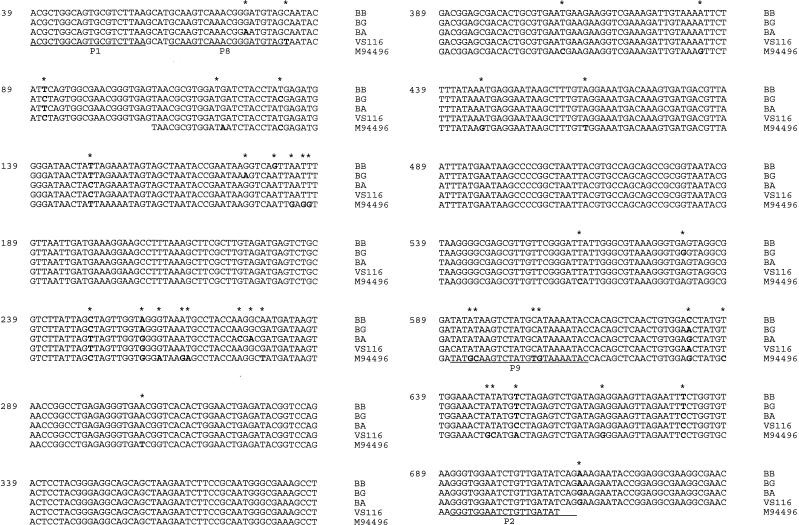

To identify the pathogenic species of the B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex within these homogenates by PCR, we used the 16S rRNA PCR primer pairs originally described by Marconi and Garon (14, 15). The homogenates were first incubated with 200 μg of proteinase K per ml at 60°C overnight to release the DNA, and the reaction was stopped by 10 min of boiling. Five microliters of the supernatant was subjected to 40 cycles of PCR amplification (94°C for 1.5 min, 42 to 64°C for 2 min, 72°C for 2 min) using Taq polymerase, 1 μM oligonucleotide primers, and 1.5 mM MgCl2 under standard conditions. PCR products were separated on a 1% (wt/vol) agarose gel and visualized under UV light after ethidium bromide staining. To analyze for the presence of inhibitory substances in PCR-negative homogenates, DNA equivalent to 20 genomes of B. afzelii (grown in BSK-H medium supplemented with 6% rabbit serum [Sigma] at 33°C) was added to one sample of the homogenate and amplified under the conditions specified above for B. afzelii. In our hands, the species-specific primer pairs for B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii, and B. garinii were quite effective, with a sensitivity of ca. 10 borreliae/PCR mixture (i.e., 50 μl). In contrast, the genus-specific primer pair for the B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex was about fivefold less sensitive in our hands, which prompted us to develop new genus-specific primers which allowed amplification of all four genospecies of B. burgdorferi analyzed in this study (i.e., B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, B. afzelii, B. garinii, and isolate VS116) with a similar sensitivity of ca. 10 borreliae/PCR mixture and no amplification of other bacteria, like Escherichia coli, Enterococcus faecalis, and Staphylococcus aureus (data not shown). Furthermore, this repertoire of primers did not allow detection of strain VS116, a novel species within the B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex which seems to be present in I. ricinus ticks in a remarkable proportion of cases (8). We therefore amplified a 1.5-kbp DNA fragment encompassing the almost complete 16S rRNA locus of strain VS116 and sequenced both strands (Fig. 1). Sequence analysis confirmed the presence of several single base changes in VS116 in comparison to the other genospecies of B. burgdorferi sensu lato, which allowed for the construction of a VS116-specific primer pair. Again, a VS116-specific amplification product was obtained with no apparent cross-binding to the other three genospecies or other bacterial genomes (as exemplified by PCRs with E. coli, E. faecalis, and S. aureus; data not shown) and a sensitivity similar to that of the other primer pairs used in this study. Oligonucleotide sequences and annealing temperatures are listed in Table 1.

FIG. 1.

Alignment of the 16S rRNA sequences of B. burgdorferi: sensu stricto (BB), B. afzelii (BA), B. garinii (BG), strain VS116, and sample M94496. Only parts of the 16S rRNA sequences (from position 39 to position 735) are shown. Variant base positions are indicated by an asterisk and boldface type; the positions of the genus-specific (P1 and P2) and VS116-specific (P8 and P9) primer pairs are underlined.

TABLE 1.

Oligonucleotide primers used in this study

| Strain | Primer sequences (5′→3′) | Position(s)a | Annealing, temp (°C) | Reference(s) |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| B. afzelii | GCATGCAAGTCAAACGGA | 59–76 | 42 | 14, 15 |

| ATATAGTTTCCAACATAGC | 648–630 | |||

| B. garinii | GGGATGTAGCAATACATCT | 74–92 | 44 | 14, 15 |

| ATATAGTTTCCAACATAGT | 648–630 | |||

| B. burgdorferi | GGGATGTAGCAATACATTC | 74–92 | 48 | 14, 15 |

| ATATAGTTTCCAACATAGG | 648–630 | |||

| VS116 | GCAAGTCAAACGGGATGTAGT (P8) | 63–83 | 52 | This study |

| GTATTTTATGCATAGACTTATATG (P9) | 612–589 | |||

| B. burgdorferi sensu lato | ACGCTGGCAGTGCGTCTTAA (P1) | 39–58 | 64 | This study |

| CTGATATCAACAGATTCCACCC (P2) | 708–687 |

In the 16S rRNA sequence of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto (in nucleotides).

Nucleotide sequence accession numbers.

16S rRNA sequences for the following strains have been submmitted to GenBank: VS116, under accession no. AJ 225165, identical to the recently published sequence of Wang et al. (24), and M94496, under accession no. AJ 229044.

Of 119 samples tested by PCR, only 50 gave a positive result and 69 samples were PCR negative despite the microscopy-determined presence of borreliae. As shown in Table 2, about one in three samples contained inhibitory factors preventing proper PCR amplification, which accounted for 42% of the borrelia-positive homogenates with negative PCR results. Another 40.5% of these homogenates are probably accounted for by insufficient sensitivity of the PCR, since a considerable number of the positive homogenates contained only low numbers of borreliae (equivalent to 1 to 10 borreliae/PCR mixture) which were below or at the detection limits of this PCR procedure. However, two samples failed to produce a PCR product despite the microscopy-determined presence of high numbers of borreliae and the absence of inhibitory substances in the PCR mixture. This would indicate the presence of still other Borrelia species, either novel as-yet-undescribed species of the B. burgdorferi complex or non-B. burgdorferi species, which do not properly bind any of the species-specific or genus-specific primers.

TABLE 2.

PCR results and number of borreliae as detected by dark-field microscopy

| No. of borreliaea | Total no. of homogenates | No. (%) of homogenates with indicated PCR result

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Positive | Negative | Inhibitedb | ||

| 0 | 30 | 0 | 30 (100) | 12 (40) |

| 1–10 | 72 | 18 (25) | 54 (75) | 26 (49) |

| >10 | 47 | 32 (68) | 15 (32) | 13 (87) |

By dark-field microscopy.

Containing inhibitory factors preventing proper PCR amplification.

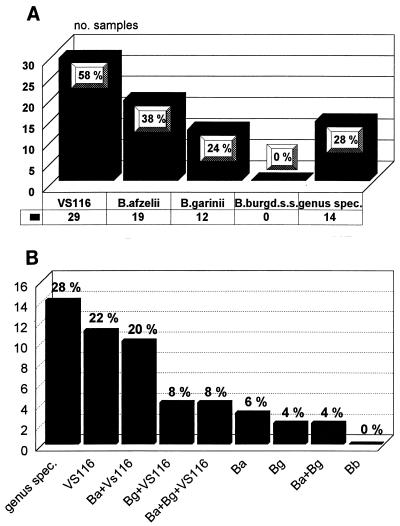

The PCR results of the noninhibited samples are shown in Fig. 2. A genospecies identification was considered definite when both PCR mixtures (that with the genus-specific primers and that with the species-specific primers) were positive and yielded DNA fragments of the correct size. Several amplification products (at least two of each group, i.e., fragments specific for B. afzelii, B. garinii, and isolate VS116, as well as those reacting only with the genus-specific primers) were also partially sequenced, and this confirmed the presence of Borrelia 16S rRNA sequences in all cases tested. Samples reacting only with the genus-specific primers (14 of 50 or 28%) are indicated in Fig. 2 as “genus spec.” DNA sequence analysis could be performed for 7 of the 14 samples, and this revealed the presence of one additional B. garinii sequence and two novel partial 16S rRNA sequences of as-yet-unknown Borrelia species. Five of the six PCR fragments with novel 16S rRNA sequences were almost identical to each other but were rather distinct from the other B. burgdorferi sensu lato sequences. Their sequences are shown in Fig. 1 for sample M94496.

FIG. 2.

Typing results of the PCR-positive tick homogenates. (A) Number of homogenates harboring the different genospecies; (B) combined analysis of the PCR typing results. B. burgd. s.s., B. burgdorferi sensu stricto; genus spec., genus specific; Ba, B. afzelii; Bg, B. garinii; Bb, B. burgdorferi sensu stricto.

Our results show that B. burgdorferi sensu stricto was not identified once among 50 positive samples. This result confirms that this species is probably of minor importance in Germany. At least in our series, a prevalence of <1/50 indicates that in northern Germany only a very small percentage of the infecting ticks transmit B. burgdorferi sensu stricto, although this species is not absent in Europe (26). Notably, a recent report on the distribution and prevalence of B. burgdorferi sensu lato genospecies in field-collected I. ricinus ticks (8) indicated a higher incidence of B. burgdorferi sensu stricto than of B. afzelii (ca. 18% versus ca. 8%), which is in striking contrast to our own observations (0% versus 38%) (Fig. 2A). The reason for this discrepancy is unknown and may either reflect local variations in the distribution of the different genospecies of B. burgdorferi sensu lato in Europe or else be related to the fact that in our series ticks that were already attached to human skin were being evaluated. Thus, our data should provide the first reliable risk assessment of acquiring one or several of the different genospecies of the B. burgdorferi sensu lato complex by tick bites rather than an estimation of the distribution and prevalence of the different genospecies in I. ricinus ticks in Germany. Strain VS116 was the most common Borrelia species identified in our infected tick collection, with 58% of all ticks harboring this strain, which is in good agreement with the aforementioned field study (8). Furthermore, there are probably several additional Borrelia species involved in tick bites, as shown by analyses of M94496 (Fig. 1) and the two tick homogenate samples that remained PCR negative despite the microscopic presence of many borreliae and the lack of inhibition. These results confirm the remarkable heterogeneity among European Lyme disease agents with possible clinical significance for human disease. And finally, despite the fact that fewer than 10% of all skin-attached ticks were infected by Borrelia species, a large proportion of the infected ticks were simultaneously positive for several genospecies of B. burgdorferi sensu lato (at least 20 of 50 or 40%; Fig. 2B). Thus, the simultaneous presence of multiple B. burgdorferi sensu stricto species is probably the rule rather than the exception in European Lyme disease, a notion of considerable importance for all clinical studies. The reason for this strain clustering must reside in the ecology of the borrelia-tick-host relationship. Further investigations are required to solve these issues.

Acknowledgments

We thank the heads of our departments, A. Liebisch and D. Bitter-Suermann, Hannover, Germany, for their continuous strong support and M. Frosch, Würzburg, Germany, for his help in the organization of this project. We also acknowledge the donations of strains by L. Gern, G. Baranton, W. Burgdorfer, and O. Peter.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aberer E, Kersten A, Klade H, Poitschek C, Jurecka W. Heterogeneity of Borrelia burgdorferi in the skin. Am J Dermatopathol. 1996;18:571–579. doi: 10.1097/00000372-199612000-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Baranton G, Postic D, Saint Girons I, Boerlin P, Piffaretti J C, Assous M, Grimont P A D. Delineation of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu stricto, Borrelia garinii sp. nov., and group VS461 associated with Lyme borreliosis. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1992;42:378–383. doi: 10.1099/00207713-42-3-378. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Barbour A G, Heiland R A, Howe T R. Heterogeneity of major proteins in Lyme disease borreliae: a molecular analysis of North American and European isolates. J Infect Dis. 1985;152:478–484. doi: 10.1093/infdis/152.3.478. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burgdorfer W. Discovery of the Lyme disease spirochete and its relation to tick vectors. Yale J Biol Med. 1984;57:515–520. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gern L, Zhu Z, Aeschlimann A. Development of Borrelia burgdorferi in Ixodes ricinus females during blood feeding. Ann Parasitol Hum Comp. 1990;65:89–93. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Halperin J J. Neuroborreliosis. Am J Med. 1995;98:52S–59S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80044-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hu C M, Leuba-Garcia S, Kramer M D, Aeschlimann A, Gern L. Comparison in the immunological properties of Borrelia burgdorferi isolates from Ixodes ricinus derived from three endemic areas in Switzerland. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;112:533–542. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800051232. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kirtstein F, Rijpkema S, Molkenboer M, Gray J S. Local variations in the distribution and prevalence of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato genomospecies in Ixodes ricinus ticks. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1102–1106. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.3.1102-1106.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Liebisch A, Olbrich S. The hedgehog tick, Ixodes hexagonus Leach, 1815, as a vector of Borrelia burgdorferi in Europe. In: Dusbabek F, Bukva V, editors. Modern acarology. Vol. 2. The Hague, The Netherlands: Academia Prague and SPB Academic Publishing bv; 1991. pp. 67–71. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liebisch, G., B. Dimpfl, B. Finkbeiner-Weber, A. Liebisch, and M. Frosch. The red fox (Vulpes vulpes), a reservoir competent host for Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato, p. 238. In Abstracts of the Second International Conference on Tick Borne Pathogens at the Host Vector Interface (THPI), 28 August to 1 September 1995, Krüger National Park, South Africa.

- 11.Liebisch G, Finkbeiner-Weber B, Liebisch A. The infection with Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. in the European hedgehog (Erinaceus europaeus) and its ticks. Parassitologia (Rome) 1996;38:385. . (Abstract.) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Liebisch G, Hoffmann L, Pfeiffer F, Liebisch A. The infection with Borrelia burgdorferi s.l. in the red fox (vulpes vulpes) and its ticks. Parassitologia (Rome) 1996;38:386. . (Abstract.) [Google Scholar]

- 13.Marconi R T, Garon C F. Identification of a third genomic group of Borrelia burgdorferi through signature nucleotide analysis and 16S rRNA sequence determination. J Gen Microbiol. 1992;138:533–536. doi: 10.1099/00221287-138-3-533. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Marconi R T, Garon C. Development of polymerase chain reaction primer sets for diagnosis of Lyme disease and for species-specific identification of Lyme disease isolates by 16S rRNA signature nucleotide analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:2830–2834. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.11.2830-2834.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Marconi R T, Garon C F. J. Clin Microbiol. 1992;31:1026. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.11.2830-2834.1992. . (Erratum.) [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Marconi R T, Lubke L, Hauglum W, Garon C F. Species-specific identification of and distinction between Borrelia burgdorferi genomic groups by using 16S rRNA-directed oligonucleotide probes. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:628–632. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.3.628-632.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Monin R, Gern L, Aeschlimann A. A study of the different modes of transmission of Borrelia burgdorferi by Ixodes ricinus. Zentbl Bakteriol Suppl. 1989;18:14–20. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Peter O, Bretz A-G, Bee D. Occurrence of different genospecies of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in ixodid ticks of Valais, Switzerland. Eur J Epidemiol. 1995;11:463–467. doi: 10.1007/BF01721234. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Rijpkema S G T, Molkenboer M J C H, Schouls L M, Jongejan F, Schellekens J F P. Simultaneous detection and genotyping of three genomic groups of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato in Dutch Ixodes ricinus ticks by characterization of the amplified intergenic spacer region between 5S and 23S rRNA genes. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:3091–3095. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.12.3091-3095.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sigal L H. Early disseminated Lyme disease: cardiac manifestations. Am J Med. 1995;98:25S–29S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80041-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Steere A C. Musculoskeletal manifestations of Lyme disease Am. J Med. 1995;98:44S–51S. doi: 10.1016/s0002-9343(99)80043-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Valsangiacomo C, Balmelli T, Piffaretti J C. A phylogenetic analysis of Borrelia burgdorferi sensu lato based on sequence information from the hbb gene, coding for a histone-like protein. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:1–10. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-1-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Van Dam A P, Kuiper H, Vos K, Widjojokusomo A, De Jongh B M, Spanjaard L, Ramselaar A C P, Kramer M D, Dankert J. Different genospecies of Borrelia burgdorferi are associated with distinct clinical manifestations of Lyme borreliosis. Clin Infect Dis. 1993;17:708–717. doi: 10.1093/clinids/17.4.708. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wang G, van Dam A P, Fleche A L, Postic D, Peter O, Baranton G, de Boer R, Spanjaard L, Dankert J. Genetic and phenotypic analysis of Borrelia valaisiana sp. nov. Int J Syst Bacteriol. 1997;47:926–932. doi: 10.1099/00207713-47-4-926. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Wilske B, Busch U, Fingerle V, Jauris-Heipke S, Preac-Mursic V, Rössler D, Will G. Immunological and molecular variability of OspA and OspC. Implications for Borrelia vaccine development. Infection. 1996;24:208–212. doi: 10.1007/BF01713341. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Wilske B, Preac-Mursic V, Göbel U B, Graf B, Jauris S, Soutschek E, Schwab E, Zumstein G. An OspA serotyping system for Borrelia burgdorferi based on reactivity with monoclonal antibodies and OspA sequence analysis. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:340–350. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.2.340-350.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]