Abstract

Primers were designed to amplify sequences of verocytotoxin genes and eaeA genes of Escherichia coli O26:H11, O111:H8, and O157:H7 in a multiplex PCR assay. This assay successfully detected E. coli O26:H11 in bloody stool specimens in which other enteric pathogens were not detected by culture-based methods. Rapid assays to detect non-O157:H7 verocytotoxin-producing E. coli is important to improve methods for the etiologic diagnosis of hemorrhagic colitis.

Multiple serotypes of verocytotoxin (Shiga-like toxin)-producing Escherichia coli (VTEC) have been isolated from humans, but E. coli serotype O157:H7 has been the most common (11, 14). The spectrum of disease associated with E. coli O157:H7 has been well described, but the role of non-O157 VTEC strains in causing human enteric disease has been less well defined (11, 14). Recent reports have implicated the emerging importance of multiple non-O157 VTEC serotypes as a cause of hemorrhagic colitis and hemolytic-uremic syndrome (2, 3, 17, 26), with strains belonging to serogroups O26 and O111 being the most commonly associated with human disease (6, 11, 17, 23). Failure to ferment sorbitol and serologic agglutination with specific O157 and H7 antisera allow for the rapid detection of VTEC O157:H7. Current methods for the detection of non-O157 VTEC depend primarily on the presence of verocytotoxin (VT) and strain isolation and then on serotyping. Although slide agglutination testing with enteropathogenic E. coli serogroup O26- and O111-specific antisera will result in cross-reactions with the respective VTEC serogroups (23), most clinical laboratories do not stock such antisera nor do they look for VTEC serogroups other than O157. VT or the genes that encode it can be detected by using tissue cell assays and PCR or hybridization detection of VT genes (14, 21, 24). The detection of serum antibodies to either VT or the lipopolysaccharide of the infecting strain has been available only in research settings (6, 19, 22). Commercial enzyme immunoassays (EIA) to detect VT or O157 lipopolysaccharide directly in stools may be useful especially for large-scale testing (7, 18). These kits are specific only for the genes targeted, so that the O157 EIA does not detect non-O157 VTEC strains (7). Our efforts have focused on the development of a multiplex PCR assay to detect the more common VTEC serogroups, O26, O111, and O157, directly in stool specimens. We describe here the application of this assay for detection of VTEC serotype O26:H11 directly in bloody fecal specimens from a patient with severe hemorrhagic colitis.

A previously healthy 16-year-old female was admitted to hospital with an abrupt onset of bloody diarrhea, abdominal cramps, nausea, and vomiting after a 2-day history of fever, chills, and malaise. She did not recall eating anything unusual or partially cooked foods. No other family members or friends were ill, and she had been on no medications. She had no exposures to animals or any travel history. On examination, she had generalized abdominal tenderness, with guarding in the lower quadrants bilaterally. Laboratory investigations revealed normal hemoglobin, leukocyte, and platelet counts and renal and liver function tests. Shigella spp., Salmonella spp., Campylobacter spp., and Yersinia spp. were not detected by culture in the visibly bloody stool specimens. Stool specimens were also negative for Clostridium difficile toxin. There was a heavy growth of sorbitol-negative colonies on sorbitol MacConkey agar (SMAC), but slide agglutination testing with Bacto E. coli O Antiserum O157 (Difco Laboratories, Detroit, Mich.) was negative. The persistence of bloody stools prompted in-house testing for non-O157 VTEC isolates with a multiplex PCR assay directly applied to another two fecal specimens and to colony sweeps of their 24-h-old SMAC plates.

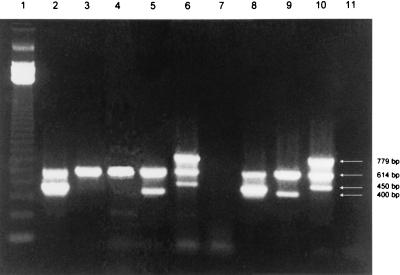

PCR performed directly on stool specimens and colony sweeps were positive for VT1 and the eaeA gene of E. coli O26:H11 but negative for VT2 and the eaeA genes of E. coli serotypes O157:H7 and O111:H8 (Fig. 1). PCR performed on multiple isolated colonies also confirmed the absence of a coinfection with strains of serogroups O111 and O157. Once the patient’s attending physician was notified of the results, considerations for further investigations such as endoscopy and laparotomy were cancelled. The patient recovered over the next several days without any complications. The sorbitol-negative isolate was identified as E. coli by using the Vitek GNI card (BioMerieux Vitek Inc., Hazelwood, Mo.) and was subsequently confirmed to be a VTEC strain of serotype O26:H11 by the Ontario Ministry of Health Reference Laboratory.

FIG. 1.

Multiplex PCR amplification of VTEC serotypes O26:H11, O111:H8, and O157:H7 directly in clinical and seeded stool specimens. Lane 1, 123-bp DNA size markers (Gibco BRL); lanes 2 to 4, stool specimens from patient that were VT1 and eaeAO26 positive (lane 2), VT1 positive and eaeAO111 negative (lane 3), and VT1 positive and eaeAO157 negative (lane 4); lane 5, seeded stool specimen with a strain of E. coli O111:H8 that was VT1 and eaeAO111 positive; lane 6, clinical stool specimen with a strain of E. coli O157:H7 that was VT1, VT2, and eaeAO157 positive; lane 7, clinical specimen negative for VTEC and seeded with E. coli ATCC 25922; lanes 8 to 10, positive controls with E. coli O26:H11, O111:H8, and O157:H7 strains, respectively; lane 11, PCR assay reagent control (no template DNA).

For the multiplex PCR assay, fecal specimen DNA was extracted by using the XTRAX DNA extraction kit (Gull Laboratories Inc., Salt Lake City, Utah). Colony sweeps and isolated colonies from agar plates were each suspended in 100 μl of 1× PCR buffer (Perkin-Elmer Cetus, Norwalk, Conn.) and boiled for 10 min prior to use as template DNA. The multiplex PCR assay was performed as described by Paton and Paton (20) but with 5 pmol each of VT1 primers, 2.5 pmol of VT2 primers, and 20 pmol each of the eaeA gene primers (either eaeAO157:H7, eaeAO111:H8, or eaeAO26:H11 primers) (Gibco-BRL). Primers (Table 1) were designed to detect VT1 and VT2 gene sequences (9), and specific eaeA gene sequences of E. coli serotypes O157:H7 (16), O111:H8 (16), and O26:H11 (12). Each PCR amplification assay included positive controls from boiled bacterial suspensions of E. coli O157:H7 strain CL8 (positive for VT1, VT2, and eaeA), E. coli O111:H8 strain RC541 (positive for VT1 and eaeA), and E. coli O26:H11 strain RC559 (positive for VT1 and eaeA); a negative control from E. coli ATCC 25922; and a reagent control (no template DNA). Thermocycling conditions with a GeneAmp 9600 thermocycler (Perkin-Elmer Cetus) were as follows: 94°C for 40 s, 56°C for 40 s, and 72°C for 40 s, for 25 cycles, ending with a 3-min extension at 72°C. PCR products were visualized on a 1% agarose gel after staining with ethidium bromide.

TABLE 1.

Primers used in multiplex PCR for the amplification of VT1, VT2, and eaeA gene sequences

| Primer | Oligonucleotide sequence (5′→3′) | Size of amplicon product (bp) | Reference |

|---|---|---|---|

| VT1 (SLT I)-F | ACA CTG GAT GAT CTC AGT GG | 614 | 9 |

| VT1 (SLT I)-R | CTG AAT CCC CCT CCA TTA TG | ||

| VT2 (SLT II)-F | CCA TGA CAA CGG ACA GCA GTT | 779 | 9 |

| VT2 (SLT II)-R | CCT GTC AAC TGA GCA CTT TG | ||

| eaeAO157:H7-F | AAG CGA CTG AGG TCA CT | 450 | 16 |

| eaeAO157:H7-R | ACG CTG CTC ACT AGA TGT | ||

| eaeAO111:H8-F | ACG TTA CTG GTG ACT TA | 400 | 16 |

| eaeAO111:H8-R | TAT TTT ATC AGC TTC AGT | ||

| eaeAO26:H11-F | CAG AAT GGT TAT GCT ACT GT | 450 | 12 |

| eaeAO26:H11-R | CTT ACA TTT GTT TTC GGC ATC |

The gene sequence variations in the 3′ end of eaeA gene homologues of VTEC serotypes O157:H7 and O111:H8 allowed the development of primers with sufficient serotype specificity to be used in multiplex PCR assays (16). Hii et al. sequenced the 3′ end of the E. coli O26:H11 eaeA gene and demonstrated preliminary data for detecting E. coli O26:H11 strains (12). The specificity of the eaeAO26:H11, eaeAO111:H8, and eaeAO157:H7 primers were tested on 199 human and cattle VTEC isolates of diverse serotypes (Table 2). These isolates were known to possess VT genes and the highly conserved central region of the eaeA gene (16). Of the 30 different VTEC serotypes, serotypes O5:NM, O69:H11, O98:NM, O118:NM, and O118:H16 were detected by PCR by using the eaeAO26:H11 primers in addition to strains of serogroup O26. The eaeAO111:H8 primers detected strains of serotypes O76:H25 and O156:H25 in addition to O111:H8 and O111:NM strains. The eaeAO157:H7 primers detected strains of serotypes O145:H8 and O145:NM in addition to O157:H7 strains. Although there was cross-detection of serotypes when these primers were used, the most frequent VTEC serotypes associated with bloody diarrhea in cattle include serotypes O5:NM, O26:H11, O103:H2, O111:H8, O111:H11, O111:NM, and O118:H16 (5). Thus, the eaeAO26 and eaeAO111 primers would be useful in screening fecal samples from calves with hemorrhagic colitis since most of these serotypes except for O103:H2 and O111:H11 would be detected. In humans, these cross-reactions may also not be problematic since VTEC strains of serotypes O69:H11, O76:H25; O118:NM, O145:H8, and O156:H25 have not been implicated in causing human disease (10, 14, 27). Strains of serotype O5 have been associated with human disease only infrequently (11, 14, 27). Therefore, eaeAO26 and eaeAO111 primers would be useful in screening human fecal samples, even though they may also detect VTEC strains of a few other serotypes that are rarely associated with human disease.

TABLE 2.

Serotype specificity of the eaeAO26, eaeAO111, and eaeAO157 primers in a multiplex PCR assay of 199 VTEC isolatesa of diverse serotypes

| Serotype | No. of isolates | No. of isolates positive by PCR by using primers for:

|

||

|---|---|---|---|---|

| eaeAO26 | eaeAO111 | eaeAO157 | ||

| O5:NM | 18 | 18 | ||

| O5:H11 | 1 | |||

| O26:NM | 2 | 2 | ||

| O26:H11 | 26 | 26 | ||

| O49:NM | 1 | |||

| O69:H11 | 2 | 2 | ||

| O74:NM | 1 | |||

| O76:H25 | 1 | 1 | ||

| O80:NM | 3 | |||

| O84:NM | 9 | |||

| O98:NM | 1 | 1 | ||

| O98:H25 | 2 | |||

| O103:NM | 1 | |||

| O103:H2 | 23 | |||

| O111:NM | 22 | 22 | ||

| O111:H8 | 7 | 7 | ||

| O111:H11 | 6 | |||

| O115:H18 | 3 | |||

| O118:NM | 1 | 1 | ||

| O118:H16 | 1 | 1 | ||

| O119:NM | 1 | |||

| O119:H25 | 3 | |||

| O139:H19 | 1 | |||

| O145:NM | 12 | 9 | ||

| O145:H8 | 1 | 1 | ||

| O153:H31 | 1 | |||

| O156:H25 | 2 | 2 | ||

| O156:H35 | 1 | |||

| O157:H7 | 45 | 45 | ||

| O172:NM | 1 | |||

All VTEC isolates are known to possess the highly conserved central region of the eaeA gene.

Recognition of the frequency and significance of non-O157 VTEC-associated infections has been hampered by the lack of specific diagnostic tools for rapid detection in the clinical laboratory (3, 26). Culture methods do not readily detect non-O157 VTEC strains since not all VTEC strains are sorbitol negative (15, 26). Direct fecal VT cytotoxicity assays are more sensitive, while the testing of individual isolates results in lower sensitivity unless large numbers are screened (21, 24). Detection of VT genes alone may not suffice, since it is not yet known which VT-producing bacteria are truly pathogenic in humans (26). There is also the potential for strains to lose their VT genes upon serial passage or subculture (13).

Various PCR-based strategies to look for E. coli O157:H7 and other VTEC serogroups have been developed (8, 16, 20, 21). Paton et al. initially incubated feces in an overnight broth culture, prior to PCR amplification, which resulted in a delay in detection (20, 21). Most recently, they first used a two-step multiplex PCR assay to detect VT1, VT2, eaeA, and hlyA (enterohemolysin) gene sequences and then a second multiplex assay to detect the O antigen-encoding regions of E. coli O157 (rfbO157) and O111 (rfbO111) (20). Their generic eaeA primers detected a conserved region of the eaeA gene in both enteropathogenic E. coli and VTEC, and their hlyA primers were also not serotype specific (25). The combination of primers to detect VT1, VT2, and the rfbO157 and rfbO111 regions might be more serotype specific; however, the amplified fragments of rfbO157 and VT2 were too similar in size to be easily discernible by gel visualization. Unlike these previous studies, in which PCR was performed on crude DNA extracts from primary fecal broth cultures, our multiplex PCR assay detected VT genes and provided specific serotype identification directly in fecal samples within 2 to 3 h of specimen receipt.

To our knowledge, this report illustrates the first description of serotype O26 primers used in a multiplex PCR assay directly on stool specimens to provide an etiologic diagnosis of hemorrhagic colitis. Many cases of non-O157 VTEC-associated disease are being diagnosed only fortuitously (1, 15, 23). The development of methods for rapid and accurate diagnosis will enhance studies on the epidemiology of VTEC-associated disease, prevent the use of unnecessary antibiotics and investigative procedures, allow the use of novel treatment modalities (2, 4, 26) which may prevent the development of hemolytic-uremic syndrome, and reduce public health risks by identifying potential sources more quickly. VTEC, especially non-O157:H7 VTEC, must be considered a possible cause of bloody diarrhea, regardless of whether the organism isolated from SMAC plates is sorbitol fermenting or non-sorbitol fermenting (2, 23, 26). Although we used a multiplex PCR assay, clinical laboratories may consider the use of commercially available EIA assays as an initial rapid screen for VTEC. Clinical laboratories should be vigilant of the potential for non-O157 VTEC to cause enteric disease.

Acknowledgments

This work was supported by the Physicians’ Services Incorporated Foundation (grant 94-5).

REFERENCES

- 1.Abbott S L, Sowers E G, Aleksic S, Janda J M. A case of bloody diarrhea due to shiga-like toxin II-producing Escherichia coli serotype O48:H21. Clin Microbiol Newsl. 1996;18:22–23. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Acheson D W K, Keusch G T. Editorial response: Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli serotype OX3:H21 as a cause of hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1280–1282. doi: 10.1086/513668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Acheson D W K, Keusch G T. Which Shiga toxin-producing types of E. coli are important? ASM News. 1996;62:302–306. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Armstrong G D, Rowe P C, Goodyer P, Orrbine E, Klassen T P, Wells G, MacKenzie A, Lior H, Blanchard C, Auclair F, Thompson B, Rafter D J, McLaine P N. A phase I study of chemically synthesized verotoxin (Shiga-like toxin) pk-trisaccharide receptors attached to Chromosorb for preventing hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1995;171:1042–1045. doi: 10.1093/infdis/171.4.1042. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Butler D G, Clarke R C. Diarrhea and dysentery in calves. In: Gyles C L, editor. Escherichia coli in domestic animals and humans. Wallingford, United Kingdom: CAB International; 1994. pp. 91–116. [Google Scholar]

- 6.Caprioli A, Luzzi I, Rosmini F, Pasquini P, Cirrincione R, Gianviti A, Matteucci M C, Rizzoni G the HUS Italian Study Group. Hemolytic-uremic syndrome and Vero cytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli infection in Italy. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:154–158. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.1.154. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Dylla B L, Vetter E A, Hughes J G, Cockerill F R., III Evaluation of an immunoassay for direct detection of Escherichia coli O157 in stool specimens. J Clin Microbiol. 1995;33:222–224. doi: 10.1128/jcm.33.1.222-224.1995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Gannon V P J, Rashed M, King R K, Goldsteyn Thomas E J. Detection and characterization of the eae gene of Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli using polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:1268–1274. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.5.1268-1274.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gannon V P J, King R K, Kim J Y, Goldsteyn Thomas E J. Rapid and sensitive method for detection of Shiga-like toxin-producing Escherichia coli in ground beef using the polymerase chain reaction. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1992;58:3809–3815. doi: 10.1128/aem.58.12.3809-3815.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Goldwater P N, Bettelheim K A. The role of enterohaemorrhagic E. coli serotypes other than O157:H7 as causes of disease. In: Karmali M A, Goglio A G, editors. Recent advances in verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli infections. Amsterdam, The Netherlands: Elsevier Science B.V.; 1994. pp. 57–60. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Griffin P M, Tauxe R V. The epidemiology of infections caused by Escherichia coli O157:H7, other enterohemorrhagic E. coli, and the associated hemolytic uremic syndrome. Epidemiol Rev. 1991;13:60–98. doi: 10.1093/oxfordjournals.epirev.a036079. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hii J H, De Azavedo J, Louie M, Brunton J L. Abstracts of the 93rd General Meeting of the American Society for Microbiology 1993. Washington, D.C: American Society for Microbiology; 1993. The nucleotide sequence of the three prime end of the eae gene homologue of verotoxin-producing E. coli (VTEC) serotype O26:H11 differs from VTEC serotype O157:H7, abstr. D-197; p. 130. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Karch H, Meyer T, Russmann H, Heesemann J. Frequent loss of Shiga-like toxin genes in clinical isolates of Escherichia coli upon subcultivation. Infect Immun. 1992;60:3464–3467. doi: 10.1128/iai.60.8.3464-3467.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Karmali M A. Infection by verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli. Clin Microbiol Rev. 1989;2:15–38. doi: 10.1128/cmr.2.1.15. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Keskimaki M, Ikaheimo R, Karkkainen P, Scheutz F, Ratiner Y, Puohiniemi R, Siitonen A. Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli and serotype OX3:H21 as a cause of hemolytic-uremic syndrome. Clin Infect Dis. 1997;24:1278–1279. doi: 10.1086/513668. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Louie M, De Azavedo J, Clarke R, Borczyk A, Lior H, Richter M, Brunton J. Sequence heterogeneity of the eae gene and detection of verotoxin-producing Escherichia coli using serotype-specific primers. Epidemiol Infect. 1994;112:448–461. doi: 10.1017/s0950268800051153. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Ludwig K, Bitzan M, Zimmermann S, Kloth M, Ruder H, Muller-Wiefel D E. Immune response to non-O157 Vero toxin-producing Escherichia coli in patients with hemolytic uremic syndrome. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:1028–1039. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.1028. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.MacKenzie A M R, Lebel P, Orrbine E, Rowe P C, Hyde L, Chan F, Johnson W, McLaine P N the Synsorb Pk Study Investigators. Sensitivities and specificities of Premier E. coli O157 and Premier EHEC enzyme immunoassays for diagnosis of infection with verotoxin (Shiga-like toxin)-producing Escherichia coli. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:1608–1611. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.6.1608-1611.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Padhye N V, Doyle M P. Production and characterization of a monoclonal antibody specific for enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli of serotypes O157:H7 and O26:H11. J Clin Microbiol. 1991;29:99–103. doi: 10.1128/jcm.29.1.99-103.1991. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Paton A W, Paton J C. Detection and characterization of Shiga toxigenic Escherichia coli by using multiplex PCR assays for stx1, stx2, eaeA, enterohemorrhagic E. coli hlyA, rfbO111, and rfbO157. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:598–602. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.598-602.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Paton A W, Paton J C, Goldwater P N, Manning P A. Direct detection of Escherichia coli Shiga-like toxin genes in primary fecal cultures by polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Microbiol. 1993;31:3063–3067. doi: 10.1128/jcm.31.11.3063-3067.1993. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Reymond D, Johnson R P, Karmali M A, Petric M, Winkler M, Johnson S, Rahn K, Renwick S, Wilson J, Clarke R C, Spika J. Neutralizing antibodies to Escherichia coli O157 lipopolysaccharide in healthy farm family members and urban residents. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2053–2057. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.9.2053-2057.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Ricotti G C, Buonomini M I, Merlitti A, Karch H, Luzzi I, Caprioli A. A fatal case of hemorrhagic colitis, thrombocytopenia, and renal failure associated with verocytotoxin-producing, non-O157 Escherichia coli. Clin Infect Dis. 1994;19:815–816. doi: 10.1093/clinids/19.4.815. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Ritchie M, Partington S, Jessop J, Kelly M T. Comparison of a direct fecal Shiga-like toxin assay and sorbitol-MacConkey agar culture for laboratory diagnosis of enterohemorrhagic Escherichia coli infection. J Clin Microbiol. 1992;30:461–464. doi: 10.1128/jcm.30.2.461-464.1992. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Schmidt H, Karch H. Enterohemolytic phenotypes and genotypes of Shiga toxin-producing Escherichia coli O111 strains from patients with diarrhea and hemolytic-uremic syndrome. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:2364–2367. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.10.2364-2367.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tarr P I, Neill M A. Perspective: the problem of non-O157:H7 Shiga toxin (verocytotoxin)-producing Escherichia coli. J Infect Dis. 1996;174:1136–1139. doi: 10.1093/infdis/174.5.1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Willshaw G A, Scotland S M, Smith H R, Rowe B. Properties of verocytotoxin-producing Escherichia coli of human origin of O serogroups other than O157. J Infect Dis. 1992;166:797–802. doi: 10.1093/infdis/166.4.797. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]