Abstract

Introduction

It is unknown how recent changes in the tobacco product marketplace have impacted transitions in cigarette and electronic nicotine delivery system (ENDS) use.

Methods

A multistate transition model was applied to 24 242 adults and 12 067 youth in waves 2–4 (2015–2017) and 28 061 adults and 12 538 youth in waves 4 and 5 (2017–2019) of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study. Transition rates for initiation, cessation and product transitions were estimated in multivariable models, accounting for gender, age group, race/ethnicity and daily versus non-daily product use.

Results

Changes in ENDS initiation/relapse rates depended on age, including among adults. Among youth who had never established tobacco use, the 1-year probability of ENDS initiation increased after 2017 from 1.6% (95% CI 1.4% to 1.8%) to 3.8% (95% CI 3.4% to 4.2%). Persistence of ENDS-only use (ie, 1-year probability of continuing to use ENDS only) increased for youth from 40.7% (95% CI 34.4% to 46.9%) to 65.7% (95% CI 60.5% to 71.1%) and for adults from 57.8% (95% CI 54.4% to 61.3%) to 78.2% (95% CI 76.0% to 80.4%). Persistence of dual use similarly increased for youth from 48.3% (95% CI 37.4% to 59.2%) to 60.9% (95% CI 43.0% to 78.8%) and for adults from 40.1% (95% CI 37.0% to 43.2%) to 63.8% (95% CI 59.6% to 67.6%). Youth and young adults who used both products became more likely to transition to ENDS-only use, but middle-aged and older adults did not.

Conclusions

ENDS-only and dual use became more persistent. Middle-aged and older adults who used both products became less likely to transition to cigarette-only use but not more likely to discontinue cigarettes. Youth and young adults became more likely to transition to ENDS-only use.

Keywords: Electronic nicotine delivery devices, Surveillance and monitoring, Disparities

WHAT IS ALREADY KNOWN ON THIS TOPIC

Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS) use was less persistent than cigarette use before 2018, but more recent studies have suggested that ENDS use is becoming more persistent.

Observed probabilities of transitions are interdependent, so underlying transition hazard rates need to be estimated to infer changes in transition propensities.

WHAT THIS STUDY ADDS

The use of ENDS and dual use of ENDS and cigarettes became more persistent for both adults and youth after 2017.

Older adults who used both products did not become more likely to discontinue cigarette use. Youth and young adults became more likely to transition to exclusive ENDS use.

HOW THIS STUDY MIGHT AFFECT RESEARCH, PRACTICE OR POLICY

The increasing persistence of dual use should be accounted for in tobacco policies promoting harm reduction in adults and preventing initiation in youth.

Changes in transition patterns among tobacco and ENDS products need to be tracked and accounted for in models forecasting the possible impact of tobacco policies.

Introduction

Electronic nicotine delivery systems (ENDS), including e-cigarettes, have substantially changed the landscape of tobacco and nicotine products in the USA and other countries. In the USA, ENDS sales, driven by JUUL and similar products, increased dramatically over 20181,3 and fuelled concerns about a potential youth vaping epidemic.4 ENDS, as an alternative to traditional cigarettes, may create a public health benefit through harm reduction if people who use cigarettes leverage ENDS to quit or reduce smoking or if ENDS divert those who would have used cigarettes into ENDS use instead.5,8 However, the real-world impact of ENDS is uncertain, as it is unclear whether ENDS facilitate smoking cessation broadly or whether they inhibit long-term smoking cessation through continued nicotine addiction.9,11 Moreover, concerns that ENDS use by youth may lead to smoking initiation remain, despite continued declines in youth smoking.12 The impact of ENDS may depend on the product generation. Unlike newer ENDS products using nicotine salts, early freebase nicotine ENDS products were unpalatable at higher nicotine concentrations, so that different products may have substantially different impacts on tobacco use behaviours.13 These newer products also debuted new flavours, many of which appeal to youth.14 Accordingly, it is important to investigate how transitions between tobacco products (initiation, cessation and product switching) changed after 2017 and how these changes depend on age group. Previous work has highlighted increasing ENDS use among youth and decreasing ENDS cessation among adults in this period.15 16 This analysis focuses on cigarettes—the most used combustible tobacco product—and ENDS—which capture a variety of nicotine vaping products—to better understand the potential public health impact of changes in the marketplace on smoking and vaping.

Interdependencies make it difficult to interpret changes in the fraction of people transitioning from one type of product to another or to non-use. For example, an increase in the rate that people who only use cigarettes transition to dual use of cigarettes and ENDS inherently decreases the fraction of people who only use cigarettes who quit, even if the quitting rate is unchanged, because there are fewer people left to quit. Accordingly, we need to estimate the transition rates that underlie the observed transition fractions to be able to attribute changes in the fractions to changes in propensities to use or quit products. To do so, we use continuous-time multistate transition models, which are increasingly being used to analyse tobacco product transitions and to understand how sociodemographic factors impact these underlying rates.17,24 In a previous multistate transition analysis, we found that ENDS use in 2013–2017 was less persistent than cigarette use in the USA,19 but more recent work has suggested that ENDS use has become more persistent in recent years.15 In this analysis, we build on that previous work, implementing a multistate transition model using data from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study, distinguishing between waves 2–4 (2015–2017) and waves 4 and 5 (2017–2019) for adults and youth, and adjusting for demographics and frequency of product use. We also developed an approach to calculate continuous, spline-based estimates of the impact of age on tobacco product transitions, allowing a clearer picture of exactly how the rate of each transition varies by age and how these patterns changed after 2017. In addition to describing the big-picture changes in transitions, this paper specifically focuses on ENDS initiation, cigarette cessation among people who use both cigarettes and ENDS, how these transitions changed between 2015–2017 and 2017–2019, and how the changes differ by age group.

Methods

Data

The PATH Study is a national longitudinal cohort study of tobacco and nicotine product use behaviours among the civilian non-institutionalised adult (ages 18–90) and youth (ages 12–17) populations.25 The initial, nationally representative wave 1 cohort was replenished in wave 4 to form the nationally representative wave 4 cohort (about 25% of the wave 4 cohort was not in the wave 1 cohort). Our analysis compared 24 242 adults and 12 067 youth from the wave 1 cohort in waves 2–4 (October 2014–January 2018, abbreviated as 2015–2017) and 28 061 adults and 12 538 youth in the wave 4 cohort in waves 4 and 5, including wave 4.5 for youth (December 2016–November 2019, abbreviated as 2017–2019). Shadow youth (ie, youth under age 12 who were preemptively enrolled but did not participate in data collection) aged into the youth cohort in each wave, maintaining the age distribution of youth that we followed up to the subsequent wave. Transitions of youth who were age 17 were observed by determining their product use at age 18 in the adult cohort. Time between follow-up for each participant was approximately 1 year, except for the 2-year gap for adults between waves 4 and 5, as adults were not included in wave 4.5. The analytic framework explicitly accounts for the time between observations, allowing for joint analysis of data with varying follow-up times. We used information on age (both as age in years and age groups 12–14, 15–17, 18–24, 25–34, 35–54 and 55–90), gender (male and female) and race/ethnicity (Hispanic, non-Hispanic black, non-Hispanic white and other/unknown). Age was defined for each wave, so that transition rates depended on age at the most recent wave.

Participants were classified into one of five product use patterns: never established use, non-current use, cigarette-only use, ENDS-only use or dual use of both products, as in previous work.19 In brief, participants who reported no established use of cigarettes (<100 lifetime cigarettes) or ENDS (never ‘fairly regular’ use) were classified as having never established use. The other states were defined based on both established use and past 30-day use of either or both products. Non-current use was defined as ever established use of either cigarettes or ENDS but no past 30-day use of either product. A summary of the state definitions is given in online supplemental figure 1A. Additionally, use of cigarettes or ENDS was classified as daily or non-daily, depending on whether participants reported using the product 30 out of the past 30 days or fewer than 30 (based on previous analysis of the distribution of reported use26). Like age, daily use was defined for each wave separately. Characteristics of the populations are given in the supplementary material (online supplemental table 1).

Transition modelling

We used a previously developed multistate transition model19,21 to analyse the underlying transition hazard rates between product use and covariate HRs for four different groups: youth 2015–2017 (waves 2–4), youth 2017–2019 (waves 4 and 5), adults 2015–2017 (waves 2–4) and adults 2017–2019 (waves 4 and 5). Multistate transition models are continuous time, finite-state stochastic process models that assume that transition hazard rates depend only on the current state and not on past states or transition history.27 We incorporated wave 1 and wave 4 longitudinal survey weights into the model, as described in Brouwer et al,19 which provides further technical details, and the included modelled transitions are given in online supplemental figure 1B. The model estimates instantaneous risk of transition from one state to another, that is, transition hazard rates, which collectively define the probability of transitioning from one state to any other at a future time. The transition rates were converted to per-year transition probabilities over each 2-year period. We separately estimated the transition rates for youth and adults in 2015–2017 (waves 2–4) and 2017–2019 (waves 4 and 5), adjusting for gender, age group, race/ethnicity, and daily versus non-daily cigarette and ENDS use, the effects of which were estimated as covariate HR. We estimated the effect of continuous age on the transition using cubic B splines (a kind of piecewise polynomial)28 with knots at ages 12, 18, 40 and 90.

Results

Throughout the results, we compare transition probabilities, hazard rates and HRs between 2015–2017 (waves 2–4) and 2017–2019 (waves 4 and 5).

Transition probabilities and hazard rates

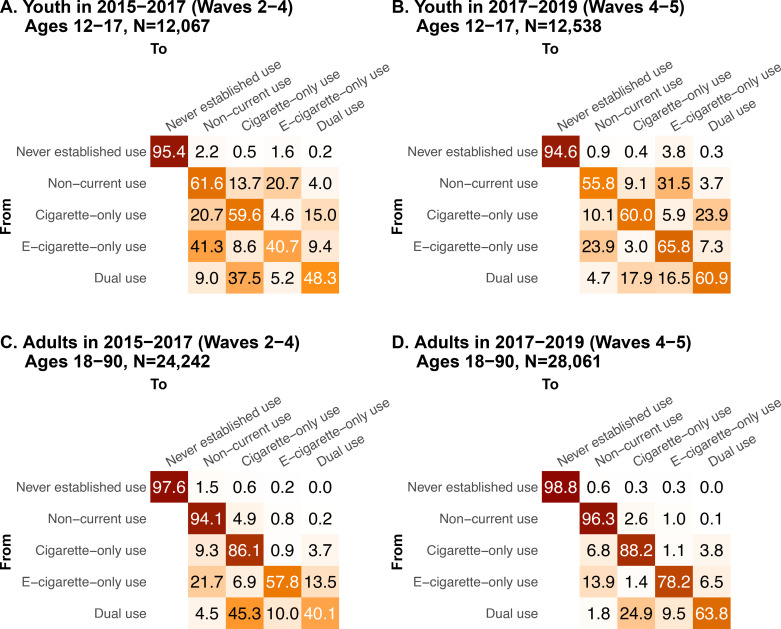

Among youth who never established use of either product, the 1-year probability of ENDS initiation increased from 1.6% (95% CI 1.4% to 1.8%) in 2015–2017 to 3.8% (95% CI 3.4% to 4.2%) in 2017–2019 (figure 1A,B). Persistence of youth ENDS-only use increased from 40.7% (95% CI 34.4% to 46.9%) to 65.8% (95% CI 60.5% to 71.1%). Youth who used cigarettes only became more likely to transition to dual use, with the 1-year transition probability increasing from 15.0% (95% CI 8.6% to 21.5%) to 23.9% (95% CI 16.0% to 31.9%). Concurrently, youth who used both products became more likely to transition to ENDS-only use, with the transition probability increasing from 5.2% (95% CI 0.8% to 9.6%) to 16.5% (95% CI 6.7% to 26.3%).

Figure 1. One-year transition probabilities for youth (A, B) and adults (C, D) in 2015–2017 (waves 2–4) (A,C) and in 2017–2019 (waves 4 and 5) (B,D). CIs are given in online supplemental figure 2.

For adults overall, there was little change after 2017 in transitions for those who only used cigarettes. Dual use became more persistent, with the 1-year probability of continuing dual use increasing from 40.1% (95% CI 37.0% to 43.2%) to 63.8% (95% CI 59.9% to 67.6%), accompanied by a decrease in transitions to cigarette-only use, which decreased from 45.3% (95% CI 42.4% to 48.3%) to 24.9% (95% CI 21.5% to 28.3%) (figure 1C,D). One-year persistence of ENDS-only use also increased from 57.8% (95% CI 54.4% to 61.3%) to 78.2% (95% CI 76.0% to 80.4%). For adults who never established use overall, there was no significant change in ENDS initiation, which remained low at 0.2% (95% CI 0.2% to 0.3%) in 2015–2017 and 0.3% (95% CI 0.3% to 0.4%) in 2017–2019.

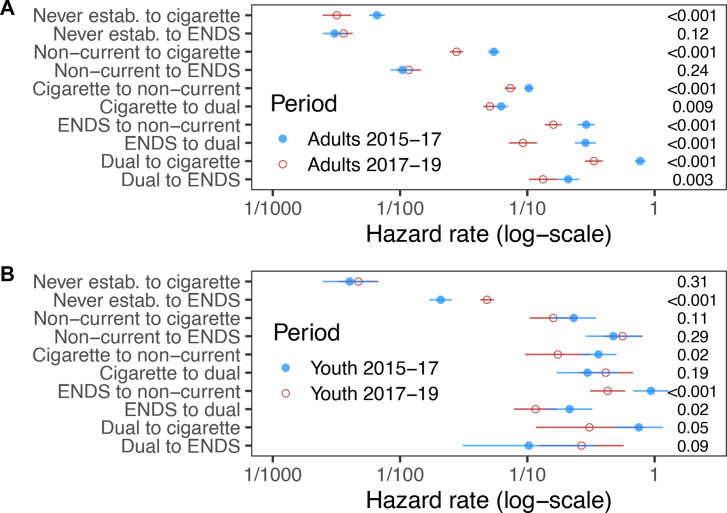

Because the transition probabilities, which must sum to one, are interdependent, they do not directly indicate whether propensities to initiate, quit or change products are increasing or decreasing. Instead, the underlying transition hazard rates reflect these propensities. We find that transition hazard rates decreased significantly among adults from 2015 to 2017 to 2017–2019, except for never established or non-current to ENDS-only use (figure 2A); that is, increases in ENDS and dual use persistence are driven by decreases in other transitions in the cohort, while never or non-current to ENDS-only use transitions stayed constant. Among youth, fewer changes in the transition rates were statistically significant (figure 2B). Exceptions included the increase in initiation from never to ENDS-only use and the decreases in the transition hazard rates from ENDS-only use to either non-current or dual use.

Figure 2. Transition hazard rates among adults and youth in 2015–2017 (waves 2–4) (A) and 2017–2019 (waves 4 and 5) (B). Values on the right-hand side are the p-values for difference in rates between the two periods. This analysis includes 24 242 adults (ages 18–90 years) and 12 067 youth (ages 12–17 years) in waves 2–4 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study and 28 061 adults and 12 538 youth in waves 4 and 5.

Sociodemographic transition HRs

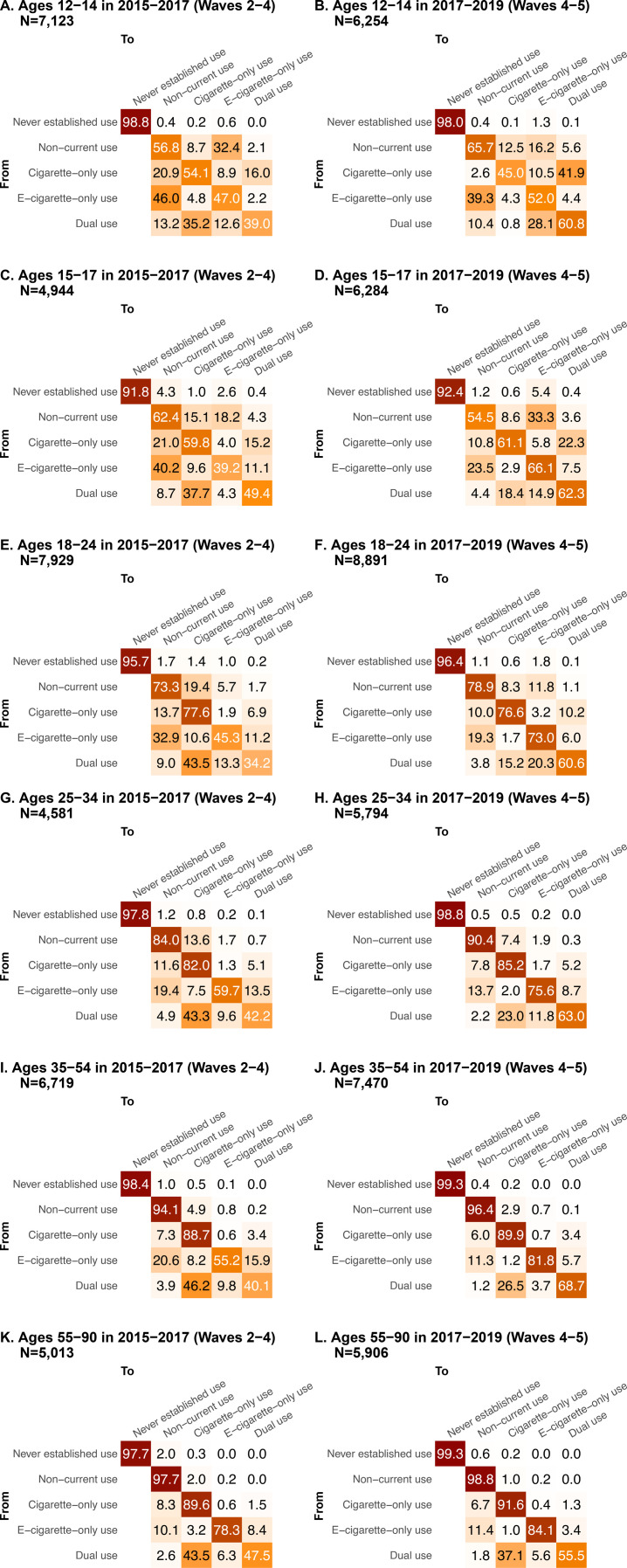

There were few changes in transition patterns by gender or race/ethnicity for adults or youth, and the impacts of non-daily versus daily use of cigarettes or ENDS were often difficult to interpret because of high variance of the estimates in many instances (table 1). Compared with youth ages 15–17, youth ages 12–14 had a lower initiation rate of cigarettes and ENDS from never use as well as a higher rate of ENDS cessation. However, the HRs comparing the two age groups for most transitions for youth did not change significantly from 2015 to 2017 to 2017–2019 even when the absolute transition rates did (figure 2). Thus, differences in transition probabilities over time for the two youth age groups (figure 3A–D) reflected changing absolute transition rates overall but stable relative transition rates.

Table 1. Covariate HRs for adults and youth in 2015–2017 and 2017–2019 in multivariable multistate transition models.

| Male versus female | Age 12–14 years vs 15–17 years | Age 18–24 years vs 35–54 years | Age 25–34 years vs 35–54 years | Age 55–90 years vs 35–54 years | Non-Hispanic black versus non-Hispanic white | Hispanic versus Non-Hispanic white | Non-daily versus daily cigarette use | Non-daily versus daily ENDS use | |

| Never to cigarette | |||||||||

| Adults 2015–2017 | 1.74 (1.29 to 2.35) | – | 2.13 (1.41 to 3.23) | 1.32 (0.84 to 2.06) | 0.71 (0.43 to 1.16) | 2.97 (1.92 to 4.61) | 3.61 (2.31 to 5.65) | – | – |

| Adults 2017–2019 | 1.23 (0.69 to 2.20) | – | 2.58 (1.32 to 5.05) | 2.11 (0.84 to 5.31) | 0.81 (0.25 to 1.87) | 0.69 (0.32 to 1.50) | 1.93 (0.97 to 3.86) | – | – |

| Youth 2015–2017 | 0.63 (0.24 to 1.62) | 0.26 (0.08 to 0.91) | – | – | – | 0.98 (0.39 to 2.48) | * | – | – |

| Youth 2017–2019 | 0.42 (0.12 to 1.56) | 0.26 (0.07 to 0.99) | – | – | – | 0.59 (0.20 to 1.78) | * | – | – |

| Never to ENDS | |||||||||

| Adults 2015–2017 | 2.61 (1.63 to 4.19) | – | 20.1 (4.59 to 87.6) | 4.18 (1.02 to 17.1) | * | 1.31 (0.74 to 2.30) | 1.12 (0.53 to 2.37) | – | – |

| Adults 2017–2019 | 1.97 (1.41 to 2.76) | – | 82.2 (13.3 to 509) | 8.95 (1.31 to 61.3) | * | 0.57 (0.37 to 0.88) | 0.74 (0.35 to 1.59) | – | – |

| Youth 2015–2017 | 1.83 (1.19 to 2.81) | 0.30 (0.05 to 1.78) | – | – | – | 0.55 (0.34 to 0.91) | * | – | – |

| Youth 2017–2019 | 1.44 (1.17 to 1.78) | 0.26 (0.20 to 0.33) | – | – | – | 0.35 (0.26 to 0.46) | 0.33 (0.19 to 0.59) | – | – |

| Non-current to cigarette | |||||||||

| Adults 2015–2017 | 0.90 (0.73 to 1.10) | – | 4.77 (3.66 to 6.21) | 3.02 (2.38 to 3.85) | 0.40 (0.29 to 0.56) | 1.08 (0.85 to 1.37) | 1.19 (0.91 to 1.55) | – | – |

| Adults 2017–2019 | 0.85 (0.68 to 1.07) | – | 3.20 (2.40 to 4.27) | 2.60 (1.94 to 3.49) | 0.34 (0.24 to 0.47) | 1.16 (0.76 to 1.76) | 1.58 (1.14 to 2.20) | – | – |

| Youth 2015–2017 | * | * | – | – | – | * | * | – | – |

| Youth 2017–2019 | 1.12 (0.48 to 2.60) | 2.35 (0.61 to 9.14) | – | – | – | 0.87 (0.22 to 3.53) | * | – | – |

| Non-current to ENDS | |||||||||

| Adults 2015–2017 | 0.98 (0.60 to 1.62) | – | 9.48 (5.48 to 16.4) | 2.24(1.13to4.47) | 0.25 (0.11 to 0.54) | 1.03 (0.55 to 1.94) | 2.16 (1.00 to 4.66) | – | – |

| Adults 2017–2019 | 0.81 (0.52 to 1.25) | – | 22.2 (14.0 to 35.2) | 2.98 (1.80 to 4.95) | 0.36 (0.12 to 1.10) | 0.88 (0. 50 to 1.53) | 0.90 (0.42 to 1.94) | – | – |

| Youth 2015–2017 | 1.02 (0.29 to 3.57) | * | – | – | – | * | * | – | – |

| Youth 2017–2019 | 2.28 (0.90 to 5.75) | 0.43 (0.09 to 2.11) | – | – | – | 0.58 (0.26 to 1.32) | * | – | – |

| Cigarette to non-current | |||||||||

| Adults 2015–2017 | 1.01 (0.85 to 1.21) | – | 1.75 (1.44 to 2.13) | 1.49 (1.23 to 1.82) | 1.22 (0.98 to 1.54) | 1.07 (0.85 to 1.35) | 0.67 (0.53 to 0.85) | 4.69 (4.08 to 5.39) | – |

| Adults 2017–2019 | 1.01 (0.84 to 1.22) | – | 1.49 (1.14 to 1.96) | 1.16 (0.94 to 1.45) | 1.11 (0.85 to 1.45) | 1.06 (0.83 to 1.36) | 0.57 (0.43 to 0.76) | 4.32 (3.66 to 5.11) | – |

| Youth 2015–2017 | 1.36 (0.24 to 7.67) | * | – | – | – | * | 0.92 (0.17 to 4.88) | 2.02 (0.42 to 9.66) | – |

| Youth 2017–2019 | 0.73 (0.11 to 4.75) | * | – | – | – | 1.12 (0.12 to 10.3) | * | * | – |

| Cigarette to dual | |||||||||

| Adults 2015–2017 | 0.90 (0.72 to 1.14) | – | 2.50 (1.65 to 3.76) | 1.64 (1.25 to 2.15) | 0.40 (0.26 to 0.61) | 0.68 (0.47 to 0.98) | 0.48 (0.32 to 0.72) | * | – |

| Adults 2017–2019 | 0.90 (0.71 to 1.15) | – | 3.17 (2.20 to 4.55) | 1.57 (1.02 to 2.41) | 0.38 (0.21 to 0.70) | 0.75 (0.47 to 1.20) | 0.61 (0.33 to 1.14) | * | – |

| Youth 2015–2017 | * | * | – | – | – | * | * | * | – |

| Youth 2017–2019 | * | * | – | – | – | * | * | * | – |

| ENDS to non-current | |||||||||

| Adults 2015–2017 | 0.60 (0.43 to 0.83) | – | 2.16 (1.46 to 3.20) | 1.05 (0.68 to 1.59) | 0.42 (0.23 to 0.77) | 2.32 (1.69 to 3.18) | 2.67 (1.63 to 4.39) | – | 1.13 (0.22 to 5.79) |

| Adults 2017–2019 | 0.80 (0.56 to 1.13) | – | 2.20 (1.33 to 3.64) | 1.32 (0.73 to 2.39) | 1.01 (0.52 to 1.98) | 1.43 (0.89 to 2.28) | 1.59 (0.89 to 2.85) | – | 1.39 (0.61 to 3.18) |

| Youth 2015–2017 | 1.14 (0.46 to 2.79) | 1.42 (0.22 to 9.2) | – | – | – | * | * | – | 9.52 (1.56 to 58.0) |

| Youth 2017–2019 | 1.66 (0.94 to 2.92) | 1.84 (1.07 to 3.17) | – | – | – | 1.00 (0.48 to 1.71) | 1.86 (0.28 to 12.5) | – | * |

| ENDS to dual | |||||||||

| Adults 2015–2017 | 1.25 (0.87 to 1.83) | – | 0.82 (0.48 to 1.39) | 0.78 (0.48 to 1.24) | 0.41 (0.21 to 0.83) | 0.85 (0.49 to 1.49) | 0.61 (0.24 to 1.52) | – | * |

| Adults 2017–2019 | 0.97 (0.60 to 1.55) | – | 1.20 (0.62 to 2.34) | 1.54 (0.69 to 3.42) | 0.67 (0.24 to 1.87) | 0.99 (0.52 to 1.89) | * | – | * |

| Youth 2015–2017 | 0.90 (0.24 to 3.28) | * | – | – | – | 0.72 (0.14 to 3.84) | * | – | * |

| Youth 2017–2019 | 1.49 (0.58 to 3.87) | * | – | – | – | * | 3.47 (0.64 to 18.6) | – | * |

| Dual to cigarette | |||||||||

| Adults 2015–2017 | 1.07 (0.87 to 1.32) | – | 1.18 (0.90 to 1.57) | 0.98 (0.76 to 1.26) | 0.84 (0.64, 1.09) | 1.17 (0.83 to 1.64) | 0.98 (0.62 to 1.55) | 0.57 (0.41 to 0.80) | 0.98 (0.69 to 1.41) |

| Adults 2017–2019 | 0.90 (0.63 to 1.26) | – | 0.73 (0.47 to 1.14) | 0.93 (0.60 to 1.46) | 1.42 (0.92 to 2.19) | 1.11 (0.71 to 1.74) | 0.99 (0.55 to 1.77) | 0.97 (0.59 to 1.58) | 0.53 (0.36 to 0.78) |

| Youth 2015–2017 | * | * | – | – | – | * | * | * | * |

| Youth 2017–2019 | * | * | – | – | – | * | * | * | * |

| Dual to ENDS | |||||||||

| Adults 2015–2017 | 0.98 (0.49 to 1.95) | – | 1.32 (0.64 to 2.71) | 0.94 (0.50 to 1.76) | 0.57 (0.16 to 2.07) | 0.91 (0.48 to 1.71) | 0.87 (0.27 to 2.82) | * | * |

| Adults 2017–2019 | 1.01 (0.55 to 1.87) | – | 5.48 (2.40 to 12.5) | 3.37 (1.28 to 8.89) | 1.62 (0.41 to 6.43) | 0.65 (0.24 to 1.76) | 1.47 (0.49 to 4.40) | 1.20 (0.43 to 3.33) | 3.70 (1.29 to 10.6) |

| Youth 2015–2017 | * | * | – | – | – | * | * | * | * |

| Youth 2017–2019 | * | * | – | – | – | * | * | * | * |

Boldfaced values are statistically significantly different from 1.0 at level of significance 0.05.

Estimate suppressed because of high variance (variance of log(HR) >1).

ENDSelectronic nicotine delivery system

Figure 3. One-year transition probabilities by age group in 2015–2017 (waves 2–4) (A,C,E,G,I,K) and 2017–2019 (waves 4 and 5) (B,D,F,H,J,L). CIs are given in online supplemental figure 3.

Unlike for youth, HRs comparing adult age groups did change for several transitions. For example, there was a statistically significant increase after 2017 in the HR of transitioning from non-current to ENDS-only use, with an HR of 9.48 (95% CI 5.48 to 16.4) for ages 18–24 vs 35–54 in 2015–2017 compared with 22.2 (95% CI 14.0 to 35.2) in 2017–2019 (p=0.01 for test of difference of means of the log HRs). The change in the HR for transitions from never established use to ENDS-only use for young adults (ages 18–24) versus middle-aged adults (35–54) had a large point estimate but was not statistically significant, with an HR of 20.5 (95% CI 4.59 to 87.6) for ages 18–24 vs 35–54 in 2015–2017 compared with 82.2 (95% CI 13.3 to 509) in 2017–2019 (p=0.12). Other HRs are given in table 1. The changing HRs by age drove the statistically significant increase in the probability of transitioning from non-current use to ENDS-only use among ages 18–24, accompanied by a decrease in the relapse to cigarettes (figure 3E,F). Specifically, for ages 18–24, the probabilities of transitioning from non-current use to cigarette-only and to ENDS-only use, respectively, were 19.4% (95% CI 16.5% to 22.3%) and 5.7% (95% CI 4.1% to 7.3%) in 2015–2017 and 8.3% (95% CI 6.7% to 9.9%) and 11.8% (95% CI 9.4% to 14.2%) in 2017–2019. For ages 35–54, these transition probabilities were 4.9% (95% CI 3.9% to 5.8%) and 0.8% (95% CI 0.4% to 1.1%) in 2015–2017 and 2.9% (95% CI: 0.7% to 1.3%) and 0.7% (95% CI 0.4% to 0.9%) in 2017–2019.

The HR for ages 18–24 vs ages 35–54 for the transition from dual use to ENDS-only use also increased (p=0.005) after 2017 from HR 1.32 (95% CI 0.64 to 2.71) to 5.48 (95% CI 2.40 to 12.5). These changes in the transition HRs resulted in differential changes in transition probabilities by age (figure 3). Young adults (ages 18–24) who used both products became much more likely to continue using both products (34.2% (95% CI 28.5% to 39.9%) in 2015–2017 to 60.6% (95% CI 54.1% to 67.2%) in 2017–2019), less likely to transition to cigarette-only use (43.5% (95% CI 38.2% to 48.8%) to 15.2% (95% CI 10.6% to 19.9%)) and marginally more likely to transition to ENDS-only use (13.3% (95% CI 10.0% to 16.5%) to 20.3% (95% CI 15.0% to 25.7%)). Middle-aged adults (ages 35–54) who used both products also became more likely to continue using both products (40.1% (95% CI 34.7% to 45.5%) in 2015–2017 to 68.7% (95% CI 62.3% to 75.1%) in 2017–2019) and less likely to transition to cigarette-only use (46.2% (95% CI 40.8% to 51.5%) to 26.5% (95% CI 20.8% to 32.2%)), but they became less likely to transition to ENDS-only use (9.8% (95% CI 6.5% to 13.1%) to 3.7% (95% CI 1.4% to 5.9%)).

Impact of age on transition rates

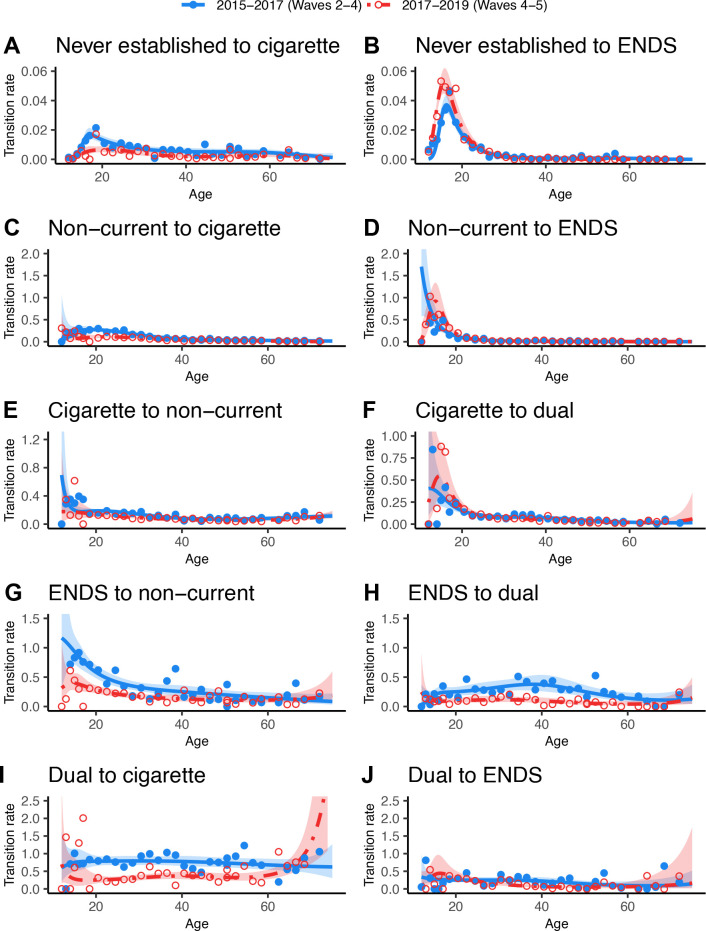

Spline estimates of transition rates as a function of age in years rather than age group are given in figure 4. ENDS initiation or relapse from never use, non-current use or cigarette-only use (to dual use) occurred primarily among youth and young adults, peaking in the late teen years. The rate of transitioning from ENDS-only to non-current use was also higher among youth and young adults, compared with older individuals. Other transitions show comparatively smaller age differences. The transitions that changed the most overall after 2017 were the ENDS-only to non-current use, ENDS-only to dual use and dual to cigarette-only use transitions; rates for each of these transitions decreased for most ages (figure 4).

Figure 4. Transition rates as a function of age for ten transitions of interest (A-J). Points are observed rates for participants in small age ranges, and the lines are continuous splines. Because overall transition rates depend on the persistence of each product use state, the vertical scale of each graph depends on the starting use state. This analysis includes 24 242 adults (ages 18–90 years) and 12 067 youth (ages 12–17 years) in waves 2–4 of the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study and 28 061 adults and 12 538 youth in waves 4 and 5. ENDS, electronic nicotine delivery system.

Discussion

We estimated how patterns of initiation, cessation and tobacco product switching changed between 2015–2017 and 2017–2019 for different age groups of youth and adults. During the latter period, there was an increase in ENDS sales driven by the uptake of JUUL and other pod-based nicotine salt systems.2 Consistent with Pierce et al,16 we found that ENDS initiation was primarily by youth and young adults, but our work also suggests that relapse among youth and young adults not currently using cigarettes or ENDS has shifted toward ENDS rather than cigarette use. Moreover, ENDS use became more persistent, both for those who used ENDS only and those who used both products, consistent with findings from Kasza et al.15 However, among adults overall, there has not been an increase in transitions from cigarette-only to ENDS-only or dual use. Additionally, adults who used both products were more likely to remain so (instead of transitioning to cigarette-only use) and overall did not become more likely to transition to ENDS-only use. However, there are important heterogeneities in ENDS use across the adulthood spectrum,29 from young adult to middle-aged adult to older adult, with young adults who had ever used cigarettes increasingly initiating ENDS. At the same time, youth of all use categories became more likely to transition to ENDS-only use, including those who used both products.

Evidence from clinical trials has suggested the ENDS can be used as a smoking cessation aid, which could have a potentially large positive public health impact.5,8 However, evidence has been mixed about whether ENDS facilitate smoking cessation when used outside of a clinical trial context.9,11 We found little evidence of large changes in the probability of adults who only use cigarettes initiating ENDS or transitioning to ENDS-only use, regardless of age group. Our previous analysis suggested that dual use is a typical transitional step between cigarette-only and ENDS-only use for those who do ultimately transition to full substitution of ENDS for cigarettes.19 Our results here show that adults who used both products increasingly remained doing so and that middle-aged and older adults did not become more likely to transition to ENDS-only use. Previous analyses of PATH Study data have raised concerns about smoking relapse among those who use ENDS,30 31 which may suggest that continued nicotine addiction through ENDS use promotes dual use. However, our analysis also showed a decrease in the probability that youth or adults who use ENDS only transition to either dual or cigarette-only use. So, while most of those who used cigarettes only were not transitioning to dual or ENDS-only use and those who used both products were not transitioning to ENDS-only use, those who used ENDS only were increasingly less likely to transition to dual or cigarette-only use. Those who used ENDS only became more settled in their use over time. There is substantial heterogeneity among people who use both products,21 so future research should seek to better understand how the ENDS initiation among people who use cigarettes impacts frequency and intensity of smoking, as well as cessation.

There were large differences by age group among adults for ENDS-related product use transitions, with transitions more likely among younger adults. While middle-aged and older adults did not become more likely to transition from dual use to ENDS-only use, younger adults became more likely to completely substitute ENDS for cigarettes. We also found little evidence for increased ENDS initiation over time among adults, with the exception of young adults; ENDS use among middle-aged and older adults appears to be almost entirely among those who ever used cigarettes. We also found that young adults relapsing from non-current use were increasingly likely to use ENDS rather than cigarettes. Our results emphasise that pooling all adults together based on an age 18 cut-off masks critical, public health-relevant heterogeneities in behaviour across the adult developmental spectrum.

Unlike among adults overall, there was an increase in ENDS initiation among youth who had never established use, roughly doubling the fraction of those initiating regular ENDS use in 1 year (to nearly 4% overall). Though not high and decreasing over the time periods we considered, we did find some probability of youth transitioning from ENDS-only use to cigarette use (only or dual); ENDS use became more persistent, but the likelihood of transition to dual use did not increase. This result is consistent with other work that has found no increase in youth cigarette use,12 although lack of an increase does not mean that ENDS are not slowing the decreasing trend in cigarette use.

Our results have important implications for both researchers and regulators. Empirical studies of transitions at one time period may not be relevant at another time period, and studies, especially those that incorporate multiple years of data, should consider whether their underlying transition rates may be time-varying. For example, research developing model-based projections calibrated to transition rates estimated for specific years may not provide good projections because of this time variation, and so potential time variation should be recognised as a limitation in modelling studies. Similarly, policy recommendations can be based on both historical and the most recently available data, accounting for previous changes over time as well as uncertainty in how transitions may continue to change in the future.

The strengths of this analysis are in the high-quality, nationally representative data of the PATH Study on both youth and adults and in the multistate modelling framework that allows observed transitions to be connected to underlying transition rates. However, this work represents only a snapshot of transition behaviours in two time periods, 2015–2017 and 2017–2019. It is unclear how transition behaviours will change after this period, given the EVALI (e-cigarette or vaping use-associated lung injury) outbreak of late 2019,32 the COVID-19 pandemic,33 the shifts in the tobacco and nicotine product marketplace,1 2 34 the emerging restrictions on flavoured tobacco and ENDS products at the federal, state and local level,35 36 and the Food and Drug Administration (FDA) decisions on millions of e-cigarette product market authorisation applications. Moreover, because the PATH Study is a longitudinal cohort study, some of the changes in the transition rates may in part be due to individuals settling into longer-term patterns. This concern should be somewhat alleviated by the replenishment in wave 4 and the ageing of shadow youth into the cohort. Other limitations of the method include the lack of accounting for individuals’ longer-term product trajectories (Markov assumption) and our inability to make causal inferences (eg, differences in cigarette initiation between those who never established use and those who use ENDS only may be caused by underlying demographic differences in the two populations, not the ENDS use itself). Additionally, while the model does account for the possibility of multiple transitions between follow-up points, yearly data (and, for adults in waves 4 and 5, every other year) are not sufficient to capture shorter-term transitions in past 30-day use22 or the dynamics of experimentation with smoking or vaping. We also did not account for ENDS flavouring in this analysis.

Our work highlights both the difference in ENDS use patterns by age, with uptake primarily among youth and young adults, and in changes between 2015–2017 and 2017–2019, which may be attributed to changes in the ENDS marketplace and the ability of products to deliver nicotine.13 37 Newer generations of ENDS products have higher nicotine content without being unpalatable and are more efficient at nicotine delivery, which likely explain the increased persistence of ENDS use since 2017. However, adults who use cigarettes and ENDS, particularly older adults (ages 55+), appear to be at a higher likelihood of continuing to use both products and not quitting cigarettes. Younger adults (ages 18–24) who use both products were more successful over time at transitioning to ENDS-only use, and young adults who currently use neither product were increasingly relapsing to ENDS rather than cigarette use. Youth who never established use were initiating ENDS use more in 2017–2019 than in 2015–2017, but this change does not appear to have increased smoking initiation. Altogether, these results reveal a complicated picture of the potential public health impact of ENDS in the USA.

While the long-term public health impact of ENDS remains to be seen, it will be shaped by public perceptions of ENDS, changes in the tobacco and nicotine product marketplace and marketing strategies, and changes in the regulatory environment. Major national public education campaigns led by the FDA and public health advocacy organisations have highlighted the dangers of ENDS use, while the ENDS industry has marketed their products’ purported benefits, influencing both youth and adult harm perceptions of ENDS. The prevention of ENDS initiation among those who have never used cigarettes is an important regulatory goal, but so is the promotion of harm reduction among those who currently use cigarettes who are not yet willing or able to quit smoking completely. The US FDA has recently deemed some tobacco-flavoured ENDS ‘appropriate for the protection of public health’ while issuing market denial orders for most flavoured ENDS products. These regulatory actions will impact the availability of ENDS in the US marketplace and ultimately impact transitions in tobacco and nicotine product use in the future.

supplementary material

Footnotes

Funding: This project was funded through National Cancer Institute and Food and Drug Administration (grant U54CA229974). The opinions expressed in this article are the authors’ own and do not reflect the views of the National Institutes of Health, the Department of Health and Human Services or the US government.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Patient consent for publication: Not applicable.

Data availability free text: Public Use Files from the Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health Study are available for download from an open access repository (https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36498.v17). Restricted-use files (https://doi.org/10.3886/ICPSR36231.v31) require a restricted data use agreement. Conditions of use are available on the aforementioned websites.

Ethics approval: This analysis was deemed exempt from regulation as human subjects research (University of Michigan Institutional Review Board HUM00162265).

Contributor Information

Andrew F Brouwer, Email: brouweaf@umich.edu.

Jihyoun Jeon, Email: jihjeon@umich.edu.

Evelyn Jimenez-Mendoza, Email: evelynjm@umich.edu.

Stephanie R Land, Email: stephanie.land@nih.gov.

Theodore R Holford, Email: theodore.holford@yale.edu.

Abigail S Friedman, Email: abigail.friedman@yale.edu.

Jamie Tam, Email: jamie.tam@yale.edu.

Ritesh Mistry, Email: riteshm@umich.edu.

David T Levy, Email: dl777@georgetown.edu.

Rafael Meza, Email: rmeza@umich.edu.

Data availability statement

Most data are available in a public, open access repository. Other data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.

References

- 1.Huang J, Duan Z, Kwok J, et al. Vaping versus juuling: how the extraordinary growth and marketing of JUUL transformed the US retail e-cigarette market. Tob Control. 2019;28:146–51. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2018-054382. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ali FRM, Diaz MC, Vallone D, et al. E-Cigarette unit sales, by product and flavor type-United States, 2014-2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep . 2020;69:1313–8. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6937e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Hammond D, Reid JL, Burkhalter R, et al. Trends in e-cigarette brands, devices and the nicotine profile of products used by youth in England, Canada and the USA: 2017-2019. Tob Control. 2023;32:19–29. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-056371. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farzal Z, Perry MF, Yarbrough WG, et al. The adolescent vaping epidemic in the United states-how it happened and where we go from here. JAMA Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg . 2019;145:885–6. doi: 10.1001/jamaoto.2019.2410. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bullen C, Howe C, Laugesen M, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation: a randomised controlled trial. Lancet. 2013;382:1629–37. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(13)61842-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hajek P. Electronic cigarettes have a potential for huge public health benefit. BMC Med. 2014;12:225. doi: 10.1186/s12916-014-0225-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.McNeill A. Should clinicians recommend e-cigarettes to their patients who smoke? Yes. Ann Fam Med. 2016;14:300–1. doi: 10.1370/afm.1962. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Hartmann-Boyce J, McRobbie H, Lindson N, et al. Electronic cigarettes for smoking cessation. Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2021;4:CD010216. doi: 10.1002/14651858.CD010216.pub5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Kalkhoran S, Glantz SA. E-cigarettes and smoking cessation in real-world and clinical settings: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Respir Med. 2016;4:116–28. doi: 10.1016/S2213-2600(15)00521-4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Bhatnagar A, Payne TJ, Robertson RM. Is there a role for electronic cigarettes in tobacco cessation? J Am Heart Assoc. 2019;8:e012742. doi: 10.1161/JAHA.119.012742. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Wang RJ, Bhadriraju S, Glantz SA. E-Cigarette use and adult cigarette smoking cessation: a meta-analysis. Am J Public Health. 2021;111:230–46. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2020.305999. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Johnston LD, Miech RA, O’Malley PM, et al. Monitoring the future national survey results on drug use 1975-2021: overview, key findings on adolescent drug use. Ann Arbor: Institute for Social Research, University of Michigan; 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Leventhal AM, Madden DR, Peraza N, et al. Effect of exposure to e-cigarettes with salt vs free-base nicotine on the appeal and sensory experience of vaping: a randomized clinical trial. JAMA Netw Open. 2021;4:e2032757. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.32757. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.McKelvey K, Baiocchi M, Ramamurthi D, et al. Youth say ads for flavored e-liquids are for them. Addict Behav. 2019;91:164–70. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2018.08.029. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kasza KA, Tang Z, Xiao H, et al. National longitudinal tobacco product cessation rates among US adults from the path study: 2013-2019 (waves 1-5) Tob Control. 2024;33:186–92. doi: 10.1136/tc-2022-057323. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Pierce JP, Zhang J, Crotty Alexander LE, et al. Daily e-cigarette use and the surge in JUUL sales: 2017-2019. Pediatrics. 2022;149:e2021055379. doi: 10.1542/peds.2021-055379. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Hair EC, Romberg AR, Niaura R, et al. Longitudinal tobacco use transitions among adolescents and young adults: 2014-2016. Nicotine Tob Res. 2019;21:458–68. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntx285. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Niaura R, Rich I, Johnson AL, et al. Young adult tobacco and e-cigarette use transitions: examining stability using multistate modeling. Nicotine Tob Res. 2020;22:647–54. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntz030. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Brouwer AF, Jeon J, Hirschtick JL, et al. Transitions between cigarette, ends and dual use in adults in the path study (waves 1-4): multistate transition modelling accounting for complex survey design. Tob Control. 2020;31:424–31. doi: 10.1136/tobaccocontrol-2020-055967. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Brouwer AF, Jeon J, Cook SF, et al. The impact of menthol cigarette flavor in the U.S.: cigarette and ends transitions by sociodemographic group. Am J Prev Med. 2022;62:243–51. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2021.08.007. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Brouwer AF, Levy DT, Jeon J, et al. The impact of current tobacco product use definitions on estimates of transitions between cigarette and ends use. Nicotine Tob Res . 2022;24:1756–62. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntac132. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shafie-Khorassani F, Piper ME, Jorenby DE, et al. Associations of demographics, dependence, and biomarkers with transitions in tobacco product use in a cohort of cigarette users and dual users of cigarettes and e-cigarettes. Nicotine Tob Res . 2023;25:462–9. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntac207. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mantey DS, Harrell MB, Chen B, et al. A longitudinal examination of behavioral transitions among young adult menthol and non-menthol cigarette smokers using a three-state Markov model. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23:1047–54. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntaa240. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Loukas A, Marti CN, Harrell MB. Electronic nicotine delivery systems use predicts transitions in cigarette smoking among young adults. Drug Alcohol Depend. 2022;231:109251. doi: 10.1016/j.drugalcdep.2021.109251. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.National Institute on Drug Abuse, Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products . Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study [United States] Public-Use Files. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Institute on Drug Abuse, Food and Drug Administration Center for Tobacco Products . Population Assessment of Tobacco and Health (PATH) Study [United States] Restricted-Use Files. Inter-university Consortium for Political and Social Research. 2022. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Durrett R. Essentials of stochastic processes. Springer; 1999. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wang W, Yan J. Shape-restricted regression splines with R package splines2. J Data Sci. 2021;19:498–517. doi: 10.6339/21-JDS1020. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Alexander CN, Langer EJ. Higher stages of human development: perspectives on adult growth. Oxford University Press; 1990. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Azagba S, Qeadan F, Shan L, et al. E-cigarette use and transition in adult smoking frequency: a longitudinal study. Am J Prev Med. 2020;59:367–76. doi: 10.1016/j.amepre.2020.02.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Everard CD, Silveira ML, Kimmel HL, et al. Association of electronic nicotine delivery system use with cigarette smoking relapse among former smokers in the United States. JAMA Netw Open. 2020;3:e204813. doi: 10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2020.4813. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Krishnasamy VP, Hallowell BD, Ko JY, et al. Update: characteristics of a nationwide outbreak of e-cigarette, or vaping, product use-associated lung injury-United States, August 2019-january 2020. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep . 2020;69:90–4. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6903e2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.White AM, Li D, Snell LM, et al. Perceptions of tobacco product-specific COVID-19 risk and changes in tobacco use behaviors among smokers, e-cigarette users, and dual users. Nicotine Tob Res. 2021;23:1617–22. doi: 10.1093/ntr/ntab053. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Hammond D, Reid JL, Burkhalter R, et al. E-Cigarette flavors, devices, and brands used by youths before and after partial flavor restrictions in the United States: Canada, England, and the United States, 2017‒2020. Am J Public Health. 2022;112:1014–24. doi: 10.2105/AJPH.2022.306780. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Rose SW, Amato MS, Anesetti-Rothermel A, et al. Characteristics and reach equity of policies restricting flavored tobacco product sales in the united states. Health Promot Pract. 2020;21(1_suppl):44S–53S. doi: 10.1177/1524839919879928. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Gravely S, Smith DM, Liber AC, et al. Responses to potential nicotine vaping product flavor restrictions among regular vapers using non-tobacco flavors: findings from the 2020 ITC smoking and vaping survey in canada, england and the united states. Addict Behav. 2022;125:107152. doi: 10.1016/j.addbeh.2021.107152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Gholap VV, Kosmider L, Golshahi L, et al. Nicotine forms: why and how do they matter in nicotine delivery from electronic cigarettes? Expert Opin Drug Deliv. 2020;17:1727–36. doi: 10.1080/17425247.2020.1814736. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Most data are available in a public, open access repository. Other data may be obtained from a third party and are not publicly available.