Abstract

Background

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) are major complications after general anesthesia. Although various pathways are involved in triggering PONV, hypotension plays an important role. We hypothesized that intraoperative hypotension during general anesthesia might be responsible for the incidence of PONV.

Methods

We retrospectively investigated patients who underwent thyroidectomy. The initial blood pressure measured before induction of anesthesia was used as the baseline value. The systolic blood pressure measured during the operation from the start to the end of anesthesia was extracted from anesthetic records. The time integral value when the measured systolic blood pressure fell below the baseline value was calculated as area under the curve (AUC) of s100%.

Results

There were 247 eligible cases. Eighty-eight patients (35.6%) had PONV. There was no difference in patient background between the patients with or without PONV. Univariate analysis showed that the total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) (p = 0.02), smoking history (p = 0.02), and AUC-s100% (p = 0.006) were significantly associated with PONV. Multiple logistic regression analysis revealed that TIVA (OR: 0.54, 95% CI: 0.29...0.99), smoking history (OR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.37...0.96), and AUC-s100% (OR: 1.006, 95% CI: 1.0...1.01) were significantly associated with PONV.

Conclusion

Intraoperative hypotension evaluated by AUC-s100% was related to PONV in thyroidectomy.

Keywords: Postoperative nausea and vomiting, PONV, Hypotension, Thyroidectomy

Introduction

Postoperative nausea and vomiting (PONV) is a frequent complication of general anesthesia along with pain. PONV causes discomfort to the patient, which may be an obstacle to early recovery.1, 2 The frequency of PONV is approximately 30% in the general population but is as high as 70% in patients in the high-risk group.3, 4 Therefore, numerous studies have focused on reducing PONV in the past several decades. Risk factors such as inhaled anesthetics, nitrous oxide, and opioids have been identified to date. High-risk patients such as women, non-smokers, a history of motion sickness, and young patients5 are recommended to use these strategies to reduce the risk of PONV,6, 7 nonetheless, many patients still report PONV. Numerous patients feel that nausea is more stressful than postoperative pain, and that they would be willing to absorb the additional costs to avoid PONV,8 therefore, it is important not only to manage PONV with current well-known strategies, but also to search for additional simple and safe strategies.

Hypotension is a well-known factor that triggers nausea and vomiting regardless of anesthesia.9, 10 Many studies have evaluated the association between intraoperative nausea, vomiting, and intraoperative hypotension under spinal anesthesia, especially in the field of obstetrics.11, 12, 13 However, to date, only a few studies have evaluated the relationship between intraoperative hypotension and PONV in the setting of general anesthesia,14 and the results are controversial.15 The exact mechanism that causes PONV by hypotension is unclear, but reduction of blood flow to the brain stem and influence on the chemoreceptor trigger zone (CTZ) can cause dizziness and disturbance of the vestibular system, leading to nausea or vomiting. We hypothesized that avoiding intraoperative hypotension may reduce PONV in general anesthesia. If it is possible to reduce the risk of PONV by maintaining blood pressure during surgery, it can be widely accepted and used as PONV prophylaxis during general anesthesia, regardless of the facility or situation. In this study, we analyzed thyroidectomy cases in which the incidence of PONV is relatively high and the surgical procedure is simple. We continuously evaluated intraoperative hypotension as a time-integrated value and studied its relationship with the incidence of PONV.

Material and methods

The study was approved by the institutional review board of our university (Approval number: 2407), prior to its initiation. We retrospectively investigated patients aged 20 years and older who underwent thyroidectomy at our university between January 2016 and June 2019. We excluded patients who underwent concomitant surgery other than thyroidectomy and those with incomplete data.

We extracted patient details, such as age, sex, height, weight, presence of hypertension, and smoking habits, as preoperative factors. For intraoperative variables, the method of anesthesia ... whether inhalation or total intravenous anesthesia (TIVA) ..., anesthesia time, intraoperative fluid balance, total amount of fentanyl, use of intraoperative prophylactic drugs (steroid, metoclopramide, droperidol, and atropine sulfate) were extracted. The presence of PONV was extracted from the electronic medical records from face-to-face medical examination by anesthesiologists after surgery, which is usually performed around seven days after surgery. The severity of PONV is clinically evaluated as 0 (none), 1 (mild to moderate), and 2 (severe). In this study, grade 0 was classified as the PONV (-) group, while grades 1 and 2 were classified as the PONV (+) group.

Intraoperative blood pressure evaluation

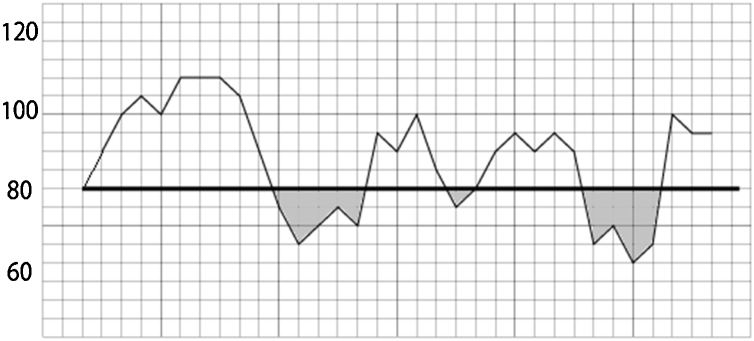

All blood pressures were measured using our standard bedside monitor (Life Scope.½ G9 Bedside Monitor, Nihon Koden, Japan) with inflation-based noninvasive blood pressure measurement. The initial systolic blood pressure measured before induction of anesthesia was defined as the baseline blood pressure and used as a baseline value. The systolic blood pressure measured during the operation, from the start of the anesthesia to the end of the operation, was extracted from anesthetic records. Typically, blood pressures were measured at 1-minute intervals during anesthetic induction and at 2.5-minute intervals during surgery. The time integral values of intraoperative hypotension were calculated if the blood pressure fell below the baseline value and were summed as AUC-s100% (Fig. 1). Since this was a retrospective study, all anesthetic managements, including fluid administration and management of blood pressure, were dependent on the anesthesiologists... discretion, taken during surgery.

Figure 1.

Calculation of AUCs. AUC, Area under curve. The time and intensity below the reference value were calculated as the time-integrated values. As an example, when the systolic blood pressure at admission was 80 mmHg, the portion surrounded by the systolic blood pressure curve and the reference line of 80 mmHg was calculated as AUC-100% (corresponding to the gray portion in the figure).

Statistical analysis

From our preliminary investigation, we presumed that the incidence of PONV after thyroidectomy was 30%. We decided to include six well-known PONV factors (age, smoking habits, anesthesia drugs, total fluid balance, gender, and anesthesia time) with degree of intraoperative hypotension, making seven explanatory variables in the multiple logistic regression model. Based on prior studies, the required sample size was estimated to be 231.

Based on the presence of PONV, the results were classified into two groups. For continuous variables, the parametric variables were expressed as mean .. standard deviation, and the nonparametric variables were expressed as the median (first quartile, third quartile) according to the data distribution. Categorical variables are expressed as the number of cases (%). As a univariate analysis, Student's t-test or Mann...Whitney test was performed, and the ..2 test was performed for categorical variables. Finally, multivariate analysis with stepwise selection was performed with factors that had univariate p-values < 0.20 on logistic regression. Explanatory variables were evaluated using the Kolmogorov...Smirnov test, and the variables were power-transformed according to the obtained results, so that the explanatory variables were normally distributed. All analyses were performed using Statflex version 7.0 (Artech Corp., Osaka, Japan). A p-value < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

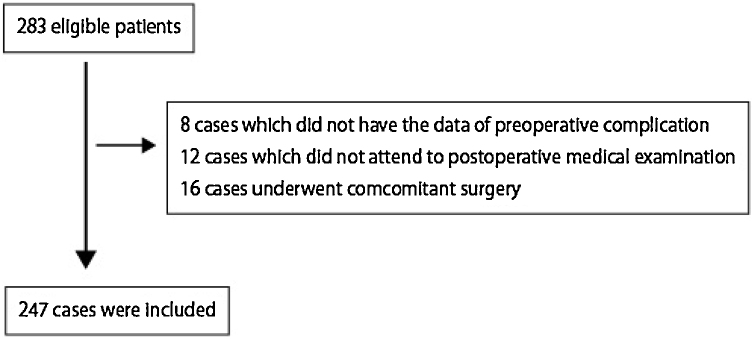

There were 283 cases during this period. Thirty-six cases were excluded due to different surgical procedures or insufficient data such as unknown preoperative complications; therefore, 247 cases were included (Fig. 2). Of the 247 patients, 88 (35.6%) had PONV. Table 1 shows the univariate analysis results with and without PONV.

Figure 2.

Study flow diagram.

Table 1.

Univariate analysis among PONV(-) and PONV (+) groups.

| PONV (-) (n = 159) | PONV (+) (n = 88) | p-value | |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age (in years)a | 57.8 .. 15.6 | 61.6 .. 12.6 | 0.052 |

| Male (%) | 34 (21.4) | 16 (18.2) | 0.54 |

| Height (cm)a | 158.0 .. 7.8 | 157.2 .. 8.4 | 0.45 |

| Weight (kg)a | 58.9 .. 11.2 | 60.1 .. 14.6 | 0.47 |

| BMI (kg.m-2)a | 23.6 .. 3.9 | 24.1 .. 4.6 | 0.29 |

| Smoker | 0.02 | ||

| Never (%) | 93 (58.5) | 65 (73.9) | |

| Past (%) | 47 (29.6) | 17 (19.3) | |

| Current (%) | 19 (12.0) | 6 (6.8) | |

| Hypertension (%) | 55 (34.6) | 34 (38.6) | 0.53 |

| Steroid medication (%) | 4 (2.5) | 1 (1.1) | 0.46 |

| TIVA (%) | 62 (39.0) | 21 (23.9) | 0.02 |

| Fluid balance (mL)a | 717.6 .. 439.1 | 814.0 .. 366.3 | 0.08 |

| Anesthesia time (min)a | 196.3 .. 91.8 | 216.3 .. 101.7 | 0.12 |

| Total dose of fentanyl (mcg.mL-1)b | 200 [150,300] | 200 [200,300] | 0.13 |

| Metoclopramide (%) | 29 (18.2) | 11 (12.5) | 0.24 |

| Droperidol (%) | 17 (10.7) | 4 (4.6) | 0.10 |

| Steroid (%) | 12 (7.6) | 3 (3.4) | 0.19 |

| Atropine (%) | 11 (6.9) | 6 (6.8) | 0.97 |

| AUC-s100%b | 3975 [2107,6811] | 5038 [3188,8510] | 0.007 |

PONV, postoperative nausea and vomiting; BMI, body mass index; TIVA, total intravenous anesthesia; AUC, area under curve.

The values are expressed as mean .. standard deviation.

Values expressed as median (first quartile, third quartile).

There was no difference in patient background between the two groups. Univariate analysis showed that TIVA (p = 0.02), smoking history (p = 0.02), and AUC-s100% (p = 0.007) were significantly associated with PONV. Multiple logistic regression analysis revealed that TIVA (OR: 0.54, 95% CI: 0.29...0.99), smoking history (OR: 0.60, 95% CI: 0.37...0.96), and AUC-s100% (OR: 1.006, 95% CI: 1.0...1.01) were significantly associated with PONV.

Discussion

In this study, multiple logistic regression analysis showed that the use of inhaled anesthetics, smoking habits, and time integral of intraoperative hypotension were associated with PONV. Although many studies have concluded that TIVA tends to reduce PONV, its impact varies among studies. This is because PONV is multifactorial and its occurrence varies depending on the surgical procedure, effect of postoperative pain, and patient's mental state. Furthermore, there are various evaluation methods, such as evaluation of nausea and vomiting separately, the evaluation method using VAS, and the examination of the need for antiemetic drugs.

RCTs performed on inhalation anesthesia and TIVA in patients undergoing laparotomic abdominal surgery reported that PONV was significantly lower in the TIVA group; however, there was no difference in vomiting rates16 (Amiri et al.). Visser et al. reported that the need for antiemetic medication is not significant among the two groups.17 In our study, PONV was evaluated by recall of the patient 7 days after the operation and resulted in a significantly lower PONV rate in the TIVA group. The second factor associated with PONV was smoking status. Yamada et al. classified the smoking status according to the time of smoking cessation, rather than evaluating it in a dichotomous manner, and reported that PONV and smoking cessation period were inversely correlated.7 This is consistent with the results of our study, which evaluated PONV by classifying it into three stages: never, past, and current finding a correlation between PONV and the smoking cessation period.

Other well-known risk factors of PONV, such as opioid use, anesthesia time, and sex were not related in our study since surgical and anesthesia procedures were uniform and the patient characteristics were comparable among groups. In addition, this study showed that the higher the intraoperative hypotension time integrated value, the higher the incidence of PONV. To the best of our knowledge, this is the first study to identify the relationship between intraoperative hypotension and PONV using the time integral value. Our results suggest that maintaining baseline blood pressure may reduce PONV.

Various definitions have been proposed to define intraoperative hypotension. Several studies defined intraoperative hypotension using systolic blood pressure, while mean arterial pressure has also been widely used in recent years.18 The cut-off value was also evaluated in various manners using an absolute value (i.e., systolic blood pressure < 80 mmHg) or as a relative value (i.e., 80% of the baseline mean arterial pressure). Furthermore, diversity in the statistical process is observed, such as expressing the results in notation in seconds or frequency.19 Jilles et al. reported in a systematic review that there were 140 definitions of intraoperative hypotension in 130 studies.20 Walsh et al. retrospectively reviewed intraoperative hypotension in 33,000 patients for non-cardiac surgery; they concluded that using a mean blood pressure of 55 mmHg as a cutoff value of intraoperative hypotension increased the risk of acute kidney injury (AKI) and cardiovascular events.21 On the other hand, a similar large cohort study by Kheterpal et al. concluded that a mean arterial pressure below 40 mmHg was a cutoff value for increased risk of AKI.22 In addition to the different clinical settings, the discrepancy in cut-off values observed in many studies is partially explained by differences in the evaluation methods. The strength of our study is that it evaluates intraoperative hypotension using time-integrated values to overcome the aforementioned issues. To this end, we evaluated systolic blood pressure, since systolic blood pressure is clinically simple to measure; however, similar results were also obtained using other criteria such as 90% of the baseline systolic pressure or by using mean arterial pressure (Table 2). The multiple logistic regression model using 100% of the baseline systolic pressure best fitted the model, and the result might indicate that strict maintenance of blood pressure at the time of admission may lead to a decrease in PONV. Further, no correlation with PONV was found when the evaluations were performed by absolute value in both cases of systolic blood pressure and mean arterial pressure, indicating that tailor-made anesthetic management of individual patients is mandatory.

Table 2.

Intraoperative hypotension with different criteria.

| Criteria | PONV (-) | PONV (+) | p-value |

|---|---|---|---|

| AUC-s100% | 3975 [2107,6811] | 5038 [3188,8510] | 0.007 |

| AUC-s90% | 2231 [935,4376] | 3018 [1600,5873] | 0.01 |

| AUC-s80% | 960 [210,2240] | 1227 [551,3282] | 0.02 |

| AUC-s100 | 1194 [740,1709] | 1252 [786,2020] | 0.24 |

| AUC-s90 | 372 [204,628] | 421 [205,748] | 0.17 |

| AUC-s80 | 71.4 [44.2, 136.8] | 89.0 [57.6, 151.0] | 0.05 |

| AUC-m100% | 2880 [1638,4773] | 3561 [2107,5499] | 0.04 |

| AUC-m90% | 1582 [821,3086] | 2037 [1037,3698] | 0.06 |

| AUC-m80% | 592 [161,1541] | 768 [313,1914] | 0.04 |

| AUC-m80 | 1614 [1078,2199] | 1752 [1196,2704] | 0.18 |

| AUC-m70 | 498 [275,823] | 552 [321,1075] | 0.08 |

| AUC-m60 | 60.0 [33.4, 132.6] | 96.6 [47.7, 202.1] | 0.01 |

AUC, area under curve.

Various baseline criteria were evaluated for AUC. For criteria described as AUC-s**, systolic blood pressures were evaluated while mean arterial pressures were evaluated for criteria described as AUC-m**. The percentage with % indicates that the relative value from the baseline blood pressure was used as a criterion, while the number without % indicates that the absolute values were used as criteria. [All AUC values expressed as median (first quartile, third quartile)].

Although the mechanism of nausea and vomiting has not been completely elucidated, PONV is thought to be induced by stimulation of the vomiting center from the vestibular organ, peripheral region, or CTZ. The main inputs in the CTZ are those from the sympathetic nervous system and stimulation from neurotransmitters, such as serotonin, dopamine, and substance P. Among them, serotonin and the sympathetic nervous system are considered as important input pathways. In fact, 5-hydroxyl tryptamine (HT3) inhibitors, such as ondansetron and granisetron, have been shown to decrease PONV in many studies.23, 24 However, many studies have failed to identify an association between intraoperative serum serotonin levels and the risk of PONV. Lim et al. examined serum serotonin levels during epidural anesthesia in obstetric parturients and found no relationship between nausea and vomiting and serum serotonin concentration.25 These reports support the evidence that serotonin released during surgery might not be responsible for PONV. Serotonin itself has a short half-life and is eliminated from blood in several minutes, and it is speculated that serotonin released during intraoperative hypotensive events does not remain after surgery.26 However, serotonin transporter, which is the main pathway for eliminating serotonin from blood, has been shown to slow uptake of serotonin when exposed to high concentrations of serotonin.27 Therefore, it may be partly explained that high serotonin levels during intraoperative hypotension may alter the uptake of serotonin after surgery and result in high serotonin levels in the postoperative phase. A recently published study by Guimar.·es et al. examined the risk factors for PONV in pregnant women undergoing cesarean section, in which hypotension caused intraoperative nausea and vomiting (IONV)and IONV was well correlated with PONV.28

As this is a retrospective study, it is difficult to clarify the mechanism of association between hypotension and PONV. We must emphasize that there might be a possibility that intraoperative hypotension is a confounder of other true factors. For example, it is necessary to consider that those with a high AUC in this study are relatively in a hypovolemic state, and therefore are potentially at a risk of intraoperative hypotension, and thus prone to face the PONV.29 In order to verify this possibility, we examined blood pressure in the postoperative ward after 1, 3, and 6 hours of the return to the general ward. Surprisingly, the blood pressure was significantly higher in the group with PONV at all points, despite the fact that the proportion of patients diagnosed with hypertension preoperatively did not differ significantly between the two groups. Although the exact mechanism is unknown, the sympathetic nervous system, which is another afferent pathway besides serotonin activation, may play an important role in PONV.

Finally, the study has some limitations. First, the important confounding factors related to PONV might not have been evaluated. For example, motion sickness could not be evaluated in this study. Inclusion of these factors in a multiple logistic regression model may yield different results. Second, PONV is a self-reported outcome, and the events were picked up from the electronic medical records. Since the definition of PONV is ambiguous, there may be underlying PONV that could not be extracted. Third, since this study is retrospective, causality may be reversed. In other words, people who are prone to PONV may be more likely to have lower blood pressure. Therefore, prospective intervention studies need to be validated with and without normal blood pressure. In conclusion, intraoperative hypotension evaluated by AUC-s100% was related to PONV in patients undergoing thyroidectomy in our study. Further studies are expected to integrate this evidence.

Conflicts of interest

The authors declare no conflicts of interest.

References

- 1.Eberhart L.H., Hogel J., Seeling W., et al. Evaluation of three risk scores to predict postoperative nausea and vomiting. Acta Anaesthesiol Scand. 2000;44:480–488. doi: 10.1034/j.1399-6576.2000.440422.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Glass P.S., White P.F. Practice guidelines for the management of postoperative nausea and vomiting: past, present, and future. Anesth Analg. 2007;105:1528–1529. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000295854.53423.8A. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Gan T.J. Postoperative nausea and vomiting--can it be eliminated? Jama. 2002;287:1233–1236. doi: 10.1001/jama.287.10.1233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Phillips C., Brookes C.D., Rich J., et al. Postoperative nausea and vomiting following orthognathic surgery. Int J Oral Maxillofac Surg. 2015;44:745–751. doi: 10.1016/j.ijom.2015.01.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Apfel C.C., Laara E., Koivuranta M., et al. A simplified risk score for predicting postoperative nausea and vomiting: conclusions from cross-validations between two centers. Anesthesiology. 1999;91:693–700. doi: 10.1097/00000542-199909000-00022. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Obrink E., Jildenstal P., Oddby E., et al. Post-operative nausea and vomiting: update on predicting the probability and ways to minimize its occurrence, with focus on ambulatory surgery. Int J Surg. 2015;15:100–106. doi: 10.1016/j.ijsu.2015.01.024. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Yamada L.A.P., Guimar.·es G.M.N., Silva M.A.S., et al. Development of a multivariable predictive model for postoperative nausea and vomiting after cancer surgery in adults. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2019;69:342–349. doi: 10.1016/j.bjane.2019.03.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Sizemore D.C., Grose B.W. In: Postoperative Nausea. StatPearls, editor. StatPearls Publishing; Treasure Island (FL): 2020. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Singh P., Yoon S.S., Kuo B. Nausea: a review of pathophysiology and therapeutics. Therap Adv Gastroenterol. 2016;9:98–112. doi: 10.1177/1756283X15618131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Rack.. K., Schw..rer H. Regulation of serotonin release from the intestinal mucosa. Pharmacol Res. 1991;23:13–25. doi: 10.1016/s1043-6618(05)80101-x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Lee J.E., George R.B., Habib A.S. Spinal-induced hypotension: Incidence, mechanisms, prophylaxis, and management: summarizing 20 years of research. Best Pract Res Clin Anaesthesiol. 2017;31:57–68. doi: 10.1016/j.bpa.2017.01.001. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.George R.B., McKeen D.M., Dominguez J.E., et al. A randomized trial of phenylephrine infusion versus bolus dosing for nausea and vomiting during Cesarean delivery in obese women. Can J Anaesth. 2018;65:254–262. doi: 10.1007/s12630-017-1034-6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Ortiz-Gomez J.R., Palacio-Abizanda F.J., Morillas-Ramirez F., et al. Reducing by 50% the incidence of maternal hypotension during elective caesarean delivery under spinal anesthesia: Effect of prophylactic ondansetron and/or continuous infusion of phenylephrine - a double-blind, randomized, placebo controlled trial. Saudi J Anaesth. 2017;11:408–414. doi: 10.4103/sja.SJA_237_17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Pusch F., Berger A., Wildling E., et al. The effects of systolic arterial blood pressure variations on postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2002;94:1652–1655. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200206000-00054. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kranke P., Roewer N., Rusch D., et al. Arterial hypotension during induction of anesthesia may not be a risk factor for postoperative nausea and vomiting. Anesth Analg. 2003;96:302–303. doi: 10.1097/00000539-200301000-00064. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ahmadzadeh Amiri A., Karvandian K., Ashouri M., et al. Comparison of post-operative nausea and vomiting with intravenous versus inhalational anesthesia in laparotomic abdominal surgery: a randomized clinical trial. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2020;70:471–476. doi: 10.1016/j.bjane.2020.08.004. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Visser K., Hassink E.A., Bonsel G.J., et al. Randomized controlled trial of total intravenous anesthesia with propofol versus inhalation anesthesia with isoflurane-nitrous oxide: postoperative nausea with vomiting and economic analysis. Anesthesiology. 2001;95:616–626. doi: 10.1097/00000542-200109000-00012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Hallqvist L., Granath F., Huldt E., et al. Intraoperative hypotension is associated with acute kidney injury in noncardiac surgery: an observational study. Eur J Anaesthesiol. 2018;35:273–279. doi: 10.1097/EJA.0000000000000735. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sessler D.I., Bloomstone J.A., Aronson S., et al. Perioperative Quality Initiative consensus statement on intraoperative blood pressure, risk and outcomes for elective surgery. Br J Anaesth. 2019;122:563–574. doi: 10.1016/j.bja.2019.01.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Bijker J.B., van Klei W.A., Kappen T.H., et al. Incidence of intraoperative hypotension as a function of the chosen definition: literature definitions applied to a retrospective cohort using automated data collection. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:213–220. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000270724.40897.8e. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Walsh M., Devereaux P.J., Garg A.X., et al. Relationship between intraoperative mean arterial pressure and clinical outcomes after noncardiac surgery: toward an empirical definition of hypotension. Anesthesiology. 2013;119:507–515. doi: 10.1097/ALN.0b013e3182a10e26. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Kheterpal S., Tremper K.K., Englesbe M.J., et al. Predictors of postoperative acute renal failure after noncardiac surgery in patients with previously normal renal function. Anesthesiology. 2007;107:892–902. doi: 10.1097/01.anes.0000290588.29668.38. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Park S.K., Cho E.J. A randomized, double-blind trial of palonosetron compared with ondansetron in preventing postoperative nausea and vomiting after gynaecological laparoscopic surgery. J Int Med Res. 2011;39:399–407. doi: 10.1177/147323001103900207. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.White P.F., Tang J., Hamza M.A., et al. The use of oral granisetron versus intravenous ondansetron for antiemetic prophylaxis in patients undergoing laparoscopic surgery: the effect on emetic symptoms and quality of recovery. Anesth Analg. 2006;102:1387–1393. doi: 10.1213/01.ane.0000208967.94601.cd. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Lim B.G., Choi S.S., Jeong Y.J., et al. The relationship between perioperative nausea and vomiting and serum serotonin concentrations in patients undergoing cesarean section under epidural anesthesia. Korean J Anesthesiol. 2014;67:384–390. doi: 10.4097/kjae.2014.67.6.384. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Mohammad-Zadeh L.F., Moses L., Gwaltney-Brant S.M. Serotonin: a review. J Vet Pharmacol Ther. 2008;31:187–199. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2885.2008.00944.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Brenner B., Harney J.T., Ahmed B.A., et al. Plasma serotonin levels and the platelet serotonin transporter. J Neurochem. 2007;102:206–215. doi: 10.1111/j.1471-4159.2007.04542.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Guimar.·es G.M.N., Silva H., Ashmawi H.A. Risk factors for post-caesarean nausea and vomiting: a prospective prognostic study. Rev Bras Anestesiol. 2020;70:457–463. doi: 10.1016/j.bjane.2020.08.006. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Apfel C.C., Meyer A., Orhan-Sungur M., et al. Supplemental intravenous crystalloids for the prevention of postoperative nausea and vomiting: quantitative review. Br J Anaesth. 2012;108:893–902. doi: 10.1093/bja/aes138. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]