Abstract

Outbreaks of anthrax zoonose occurred in two regions of France in 1997. Ninety-four animals died, and there were three nonfatal cases in humans. The diagnosis of anthrax was rapidly confirmed by bacteriological and molecular biological methods. The strains of Bacillus anthracis in animal and soil samples were identified by a multiplex PCR assay. They all belonged to the variable-number tandem repeat (VNTR) group (VNTR)3. A penicillin-resistant strain was detected. Nonvirulent bacilli related to B. anthracis, of all VNTR types, were also found in the soil.

Bacillus anthracis is the causal agent of anthrax, a serious, often fatal infection in both livestock and humans. Animals are infected by contact with soilborne spores. Humans are infected only incidentally, via contact with diseased animals or their waste products. Virulent strains of B. anthracis produce toxins and are encapsulated. These strains have two virulence plasmids: pXO1, which encodes the toxins, and pXO2, which encodes the capsule (3, 10). For the genotyping of strains, we have developed a multiplex PCR assay (12) using primers specific for pXO1 (toxin genes pag, lef, and cya), pXO2 (the capsule operon, cap), and a chromosomal marker (Ba813) specific to B. anthracis strains (11). To our knowledge, B. anthracis is one of the most molecularly monomorphic bacteria. However, vrrA, a gene containing a variable-number tandem repeat (VNTR) region, was recently described (6). In this VNTR region, a polymorphism involving five variants, differing in the number of copies (two to six) of the 12-bp tandem repeat, has been described. Rapid PCR analysis can be used to distinguish the five types. This makes it possible to classify the various strains on the basis of the number of VNTRs present. This characteristic varies with the geographic origin of the isolates, with the (VNTR)4 and (VNTR)3 types being most common in Europe. Two field outbreaks of anthrax occurred in the summer and fall of 1997 in France. These new molecular tools (multiplex PCR and VNTR analysis) were used to characterize B. anthracis strains isolated from animals and to analyze samples from the environment.

Case reports.

The first outbreak occurred in the Pyrenees. The most recent previous outbreak in this area occurred in 1994, but not in the same pastures. The first cases appeared toward the end of May at 1,000 m above sea level, in very humid areas. The outbreak began after a period of heavy rain that followed a very dry spring, and it lasted from the end of May to July, occurring in several places. Thirty-five cows died, and 82 herds, or some 1,800 cows in total, were vaccinated. A dog which had eaten contaminated cow carcasses developed septicemia with B. anthracis but recovered after treatment (14).

The second outbreak occurred in the Alps. It began at the end of July and lasted until October. The most recent previous outbreak in this region occurred during the 1980s. As in the Pyrenees, the first cases appeared after a long period of drought followed by torrential rain at the beginning of July. A similar weather pattern was also reported for the Etosha National Park outbreaks (9).

The livestock of 15 farms in the Alps was affected. Fifty-eight of 381 cows died, 2 of them 8 and 18 days after vaccination, when protection was probably not yet established. A 1-month-old calf, suckled by hand and reared outdoors, died suddenly of anthrax. On autopsy were found four stomach ulcers, probably the route of entry of the bacteria. The cattle in this area were vaccinated, with the vaccination program covering 35 farms and 750 animals (14).

Three human cases of anthrax occurred in the Pyrenees; these involved a veterinarian, a farmer, and a young boy, all infected via wounds after contact with infected animals. All were treated and subsequently recovered.

No human cases were reported in the Alps, but antibiotics were given as a preventive measure.

Diagnosis and identification of B. anthracis.

All deaths in the contaminated area were recorded. Whenever a carcass was found, blood and/or tissue specimens were collected immediately, and the bacterium involved was identified if the sample was taken early enough. Classical bacteriological tests, guinea pig inoculation, and PCR were carried out simultaneously (Table 1). A total of 11 strains were identified. This relatively small number could be explained by the fact that (i) no more than one dead animal was sampled in each affected farm and (ii) most animals were in mountain pastures, thus preventing rapid autopsy of carcasses.

TABLE 1.

Molecular characterization of B. anthracis strains collected from animals

| Strain | Regiona | Animal or strain of origin | Detection ofb:

|

VNTR categoryc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pXO1 | pXO2 | Ba813 | ||||

| 6291 | P | Cow, spleen | + | + | + | 3 |

| 6445/RA3 | P | Cow, spleen | + | + | + | 3 |

| 6445/RA3Rd | P | 6445/RA3 | + | − | + | 3 |

| 6445/RA4 | P | Cow, spleen | + | + | + | 3 |

| 6687/5088 | P | Cow, spleen | + | + | + | 3 |

| 6687/5088/L | P | Cow, milk | + | + | + | 3 |

| 6687/4896/L | P | Cow, milk | + | + | + | 3 |

| 6769 | P | Dog, blood | + | + | + | 3 |

| 6687/V | P | Vaccine strain | + | − | + | 4 |

| 7611 | A | Cow | + | + | + | 3 |

| 7611Rd | A | 7611 | + | − | + | 3 |

| 8490e | A | Cow, spleen | + | + | + | 3 |

| 9240 | A | Cow, milk | + | + | + | 3 |

| 10517 | A | Calf, spleen | + | + | + | 3 |

| 8661/V | A | Vaccine strain | + | − | + | 4 |

All of the B. anthracis strains isolated were nonmotile, penicillin sensitive (except one), glucose positive, and nonhemolytic. The virulence of the strains was tested by subcutaneous injection of 0.3 to 0.5 ml of culture (0.5 McFarland units) into guinea pigs. The guinea pigs died within 48 to 72 h, with edema occurring at the inoculation point. Bacteria were recovered from the spleen or liver, and PCR analysis demonstrated the presence of the virulence plasmids, pXO1 and pXO2. The DNA amplification procedure was performed as previously described (12). The DNA template was prepared by boiling a fresh colony for 15 min in sterile distilled water. Thus, all of the results obtained by these methods were consistent. The Sterne samples used for vaccination in both regions were also tested; as expected, they were found to contain only pXO1.

One strain, 8490, isolated from a cow in the Alps, was unexpectedly found to be resistant to penicillins (A and M), ampicillins, and cephalosporins but sensitive to tetracyclines and aminoglycosides, macrolides, and quinolones (as determined by disc diffusion). The presence of beta-lactamase was indicated by the Cefinase test (Biomerieux). Penicillin-resistant B. anthracis strains are rare (about 3% of anthrax strains) but have been reported in various countries (2, 8). However, to our knowledge, this was the first report of such a strain in France. Preventive strategies involving the use of antibiotics should take the possibility of resistance into account.

B. anthracis was detected in the milk of three infected animals shortly before, or just after, their death. Such cases of milkborne anthrax infection in dairy herds have been described before (1).

The number of VNTRs was determined by PCR for each isolate, using the EWA1 and EWA2 primers and reference VNTR DNAs (kindly provided by P. Jackson) (Table 1). All isolates from both regions had (VNTR)3, thus supporting previous reports that the VNTR number is stable in vivo during an outbreak (5). The two Sterne strains used for vaccination in these outbreaks had (VNTR)4, as reported by Jackson et al. (6).

The capsulation state of the strains was investigated by growing B. anthracis cells on CAP plates in an atmosphere of 5% CO2–95% air (13). For two isolates, one from the Pyrenees (RA3R) and one from the Alps (7611R), a rough colony was detected among the smooth, encapsulated colonies on CAP plates. This suggested that the clone had spontaneously lost the pXO2 plasmid of the virulent parental strain. PCR analysis showed that these were (VNTR)3 but had no cap markers, consistent with the loss of pXO2.

Environmental survey.

Forty-five soil and water samples were collected from the sites at which carcasses were found; two springs, stream water, mud and effluent from a clearing station, and the straw used to feed the infected calf were sampled. Some carcasses were in an advanced stage of decomposition when they were found, and two cows were found dead in stream water. The soil and water samples were heated at 65°C for 15 min and then plated on PLET medium, which is selective for B. anthracis (7, 9). Samples from areas used for feeding vultures in the Pyrenees were also analyzed. No B. anthracis was isolated, although some of these areas were used to lay out carcasses found in mountain pastures at the start of the outbreak, prior to anthrax diagnosis. However, the possibility of a role for vultures in dissemination has to be taken into account because anthrax spores are found in scavenger feces (4, 9). B. anthracis was detected in one Pyrenees soil sample (6687/5107), collected in the vicinity of a carcass. This sample contained 3,000 spores/g of soil, and the isolate had (VNTR)3 (Table 2). All other samples tested negative for B. anthracis. A similarly low level of anthrax spore isolation from a contaminated area was also reported in the Etosha National Park (9).

TABLE 2.

Analysis of PLET-positive Bacillus strains from the environment

| Strain | Regiona | Sample of origin | Detection ofb:

|

VNTR categoryc | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| pXO1 | pXO2 | Ba813 | ||||

| 6687/5107 | P | Soil | + | + | + | 3 |

| 6684 | P | Soil | − | − | + | 5-like |

| T2/9776 | P | Soil | − | − | + | 3-like |

| T5/9777 | P | Soil | − | − | + | 5-like |

| T6/9778 | P | Soil | − | − | + | 5-like |

| T11/9779 | P | Soil | − | − | + | 5-like |

| 8734/74 | A | Soil | − | − | + | 5-like |

| I1 | A | Soil | − | − | + | 5-like |

| II5 | A | Soil | − | − | + | 5-like |

| II4 | A | Soil | − | − | + | 6-like |

| I2 | A | Soil | − | − | + | ≤2-like |

| II3 | A | Soil | − | − | + | ≤2-like |

| III8 | A | Soil | − | − | + | ≤2-like |

| 9594/3 | A | Station effluent | − | − | + | 4-like |

| S8553 | A | Station mud | − | − | + | 2-like |

| PC1 | A | Straw extract | − | − | + | 5-like |

P, Pyrenees; A, Alps.

Plasmids and chromosomal marker Ba813 were detected by PCR. +, detected; −, not detected.

Determined by PCR.

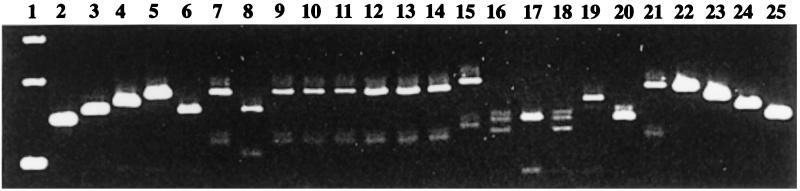

The Ba813 marker was detected by PCR in several colonies initially thought to be B. anthracis, since they grew on PLET medium (Table 2). However, these isolates were motile, hemolytic Bacillus species, and most were penicillin resistant. They appeared to be B. cereus strains and were found in various samples from both regions. The Ba813 marker had never before been found in the closely related species B. cereus and B. thuringiensis and was thus far considered to be specific for B. anthracis. VNTR analysis of these isolates was performed, and amplicons were detected for most (Fig. 1). The PCR amplicons were analyzed by electrophoresis through 3.5% (wt/vol) Metaphor agarose gels (FMC; Sigma) in 0.5× Tris-borate-EDTA containing ethidium bromide. Electrophoresis was carried out for 4 h at 80 V. We did not determine the entire sequences of these amplicons, so we defined VNTR-like categories. In contrast to the virulent B. anthracis strains of this study, which all had (VNTR)3, all five VNTR categories (2 to 6) described for B. anthracis were found among the Bacillus sp. strains, which were therefore deemed more polymorphic. The overall characteristics of these Ba813-positive strains isolated from soil ruled out the possibility that they were simply derived from B. anthracis by spontaneous curing of the virulence plasmids. Further studies are required to assess how closely related these strains are to B. anthracis.

FIG. 1.

Agarose gel electrophoresis of the B. anthracis VNTR-like amplicons in DNA extracted from PLET-positive (Ba813+) Bacillus strains isolated from the environment. Lanes: 1, 1-kb DNA ladder marker (from bottom to top, 154, 201, and 220 bp); 2 and 25, reference B. anthracis (VNTR)2 strain; 3 and 24, reference (VNTR)3 strain; 4 and 23, reference (VNTR)4 strain; 5 and 22, reference B. anthracis (VNTR)5 strain; 6, B. anthracis 6687/5107, from soil; 7, strain 6684; 8, strain T2/9776; 9, strain T5/9777; 10, strain T6/9778; 11, strain T11/9779; 12, strain 8734/74; 13, strain I1; 14, strain II5; 15, strain II4; 16, strain I2; 17, strain II3; 18, strain III8; 19, strain 9594/3; 20, strain S8553; 21, strain PC1. Reference VNTR category DNAs were provided by P. Jackson.

Thus, the methods used in this field survey made it possible to rapidly detect and determine the genotype of B. anthracis in various samples from animals and soil.

Acknowledgments

G.P. was supported by postdoctoral research grant no. 96/44133/DGA from DGA.

We thank A. Valognes, D. Grenouillat, I. Pion, D. Gauthier, and J. Ricart for supplying strains. We also thank J. Fleury for the beta-lactamase assay; F. Pedaille, R. Patty, C. Prudhomme, and Y. Game for excellent technical assistance; and V. Ramisse for helpful discussion about the analysis of soil samples with PLET medium. We are grateful to A. Fouet and C. Guidi-Rontani for critical reading of the manuscript and to R. Lambrecht for typing the manuscript.

REFERENCES

- 1.Baxter R G. Anthrax in the dairy herd. J S Afr Vet Assoc. 1977;48:293–295. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bradaric N, Punda-Polic V. Cutaneous anthrax due to penicillin resistant Bacillus anthracis transmitted by an insect bite. Lancet. 1992;340:306–307. doi: 10.1016/0140-6736(92)92395-v. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Green B D, Battisti L, Koehler T M, Thorne C B, Ivins B E. Demonstration of a capsule plasmid in Bacillus anthracis. Infect Immun. 1985;49:291–297. doi: 10.1128/iai.49.2.291-297.1985. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Houston D C, Cooper J E. The digestive tract of the whitebacked griffon vulture and its role in disease transmission among wild ungulates. J Wildl Dis. 1975;11:306–313. doi: 10.7589/0090-3558-11.3.306. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Jackson P J, Hugh-Jones M E, Adair D M, Green G, Hill K K, Kuske C R, Grinberg L M, Abramova F A, Keim P. PCR analysis of tissue samples from the 1979 Sverdlovsk anthrax victims: the presence of multiple Bacillus anthracis strains in different victims. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1998;95:1224–1229. doi: 10.1073/pnas.95.3.1224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Jackson P J, Walthers E A, Kalif A S, Richmond K L, Adair D M, Hill K K, Kuske C R, Andersen G L, Wilson K H, Hugh-Jones M E, Keim P. Characterization of the variable-number tandem repeats in vrrA from different Bacillus anthracis isolates. Appl Environ Microbiol. 1997;63:1400–1405. doi: 10.1128/aem.63.4.1400-1405.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Knisely R F. Differential media for the identification of Bacillus anthracis. J Bacteriol. 1965;90:1778–1783. doi: 10.1128/jb.90.6.1778-1783.1965. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Lightfoot N F, Scott R J D, Turnbull P C B. Antimicrobial susceptibility of Bacillus anthracis. In: Turnbull P C B, editor. Proceedings of the International Workshop on Anthrax. Salisbury Medical Bulletin, special supplement no. 68. Wiltshire, United Kingdom: Salisbury Medical Society; 1990. pp. 95–98. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindeque P M, Turnbull P C. Ecology and epidemiology of anthrax in the Etosha National Park, Namibia. Onderstepoort J Vet Res. 1994;61:71–83. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Mikesell P, Ivins B E, Ristroph J D, Dreier T M. Evidence for plasmid-mediated toxin production in Bacillus anthracis. Infect Immun. 1983;39:371–376. doi: 10.1128/iai.39.1.371-376.1983. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Patra G, Sylvestre P, Ramisse V, Thérasse J, Guesdon J-L. Isolation of a specific chromosomic DNA sequence of Bacillus anthracis and its possible use in diagnosis. FEMS Immunol Med Microbiol. 1996;15:223–231. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-695X.1996.tb00088.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Ramisse V, Patra G, Garrigue H, Guesdon J-L, Mock M. Identification and characterization of Bacillus anthracis by multiplex PCR analysis of sequences on plasmids pXO1 and pXO2 and chromosomal DNA. FEMS Microbiol Lett. 1996;145:9–16. doi: 10.1111/j.1574-6968.1996.tb08548.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sirard J-C, Mock M, Fouet A. Molecular tools for the study of transcriptional regulation in Bacillus anthracis. Res Microbiol. 1995;146:729–737. doi: 10.1016/0923-2508(96)81069-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Vaissaire J, Mock M, Patra G, Valognes A, Grenouillat D, Pion I, Gauthier D, Ricart J. Cas de charbon bactéridien en France en 1997 chez différentes espèces animales et chez l’homme. Applications de nouvelles méthodes de diagnostic. Bull Acad Vet Fr. 1997;70:445–456. [Google Scholar]