Abstract

The effect of low oxygen concentration on the growth of 15 strains of Mycobacterium ulcerans was evaluated in the BACTEC system. Reduced oxygen tension enhanced the growth of M. ulcerans, suggesting that this organism has a preference for microaerobic environments. Application of this observation may improve rates of isolation of M. ulcerans in primary culture from clinical samples and promote isolation of the bacterium from environmental sources.

Isolation of Mycobacterium ulcerans, the etiologic agent of Buruli ulcer (BU), in primary culture remains difficult. Some factors contributing to this problem are inappropriate decontamination methods (10), delay in setting up cultures, and a poor understanding of optimal growth requirements (12). Diagnosis of BU is usually made clinically when lesions are advanced and the prognosis is poor. Furthermore, acid-fast bacilli are not always detectable in smears, with positivity rates ranging from 33 to 65% (2, 5, 7, 14). Isolation of M. ulcerans in culture is the ultimate confirmatory test for diagnosis and is essential for drug susceptibility studies. Although antimycobacterial agents are presently ineffective in the treatment of advanced ulcerated lesions of BU, preulcerative nodular lesions and early, small ulcerations can be cured by antimicrobials (e.g., rifampin). The occurrence of metastatic disease from primary cutaneous lesions is now considered likely. Adjunct administration of oral antimycobacterials prior to surgical excision of lesions may control hematogenous dissemination and reduce severe sequelae, such as osteomyelitis and amputations (3, 6, 11).

The bacteriology and specific growth requirements of M. ulcerans are poorly understood. We recently described the adverse effects of most decontamination methods currently in use (10), particularly the harsh procedures used for heavily contaminated specimens. Other factors that might affect the isolation of M. ulcerans in primary culture remain unexplored.

Mycobacteria are generally considered to be aerobic; however, Wayne and Hayes recently reported that Mycobacterium tuberculosis can adapt to low oxygen concentrations (17), and Realini et al. showed enhanced growth of Mycobacterium genavense under microaerophilic conditions (16). Based on the rationale that low oxygen concentrations prevail in the necrotic lesions of BU and that recent observations indicate that environmental sources of M. ulcerans are most likely microaerobic (e.g., the subterranean depths of swamps), we evaluated the effects of different oxygen concentrations on the growth of M. ulcerans in the BACTEC system.

We studied 15 isolates of M. ulcerans (Table 1) from the collection of the Mycobacteriology Unit of the Institute of Tropical Medicine (ITM) in Antwerp, Belgium, including the type strain, ATCC 19423 (no. 5147); all strains were maintained on Löwenstein-Jensen slants. A loopful of bacteria from a fresh subculture was suspended in sterile saline in screw-cap tubes containing glass beads. The tubes were vortexed for 2 min and allowed to stand for 20 min, and the supernatants were adjusted to the opacity of a no. 1 McFarland tube.

TABLE 1.

M. ulcerans strains

| Strain no. | ITM no. | Origin |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | 5114 | Mexico |

| 2 | 5129 | Australia |

| 3 | 5147a | Australia |

| 4 | 5150 | Africa |

| 5 | 9146 | Africa |

| 6 | 94-339 | Australia |

| 7 | 94-511 | Africa |

| 8 | 94-886 | Africa |

| 9 | 94-1317 | Australia |

| 10 | 96-657 | Africa |

| 11 | 96-658 | Africa |

| 12 | 9550 | Australia |

| 13 | 94-1328 | Malaysia |

| 14 | 97-359 | Africa |

| 15 | 5146 | Africa |

ATCC 19423.

BACTEC 12B vials (Becton Dickinson Microbiology Systems) used in this study were prepared by first flushing them with gas mixtures containing 10% CO2 and either 21, 5, or 2.5% O2 and a balance of N2.

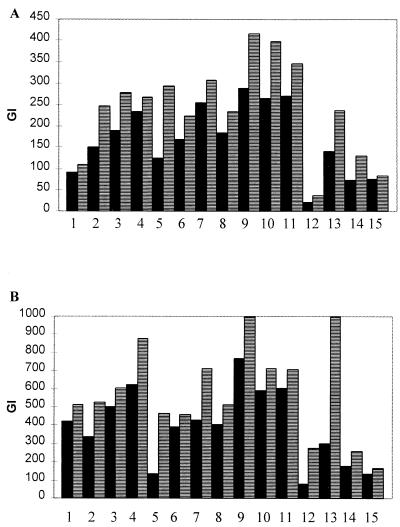

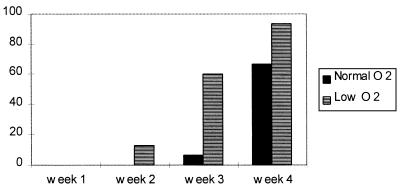

The 15 strains of M. ulcerans were initially evaluated by inoculating 106 bacilli (0.1 ml) into vials in triplicate at two different oxygen concentrations: an aerobic (AE) mixture containing 21% O2 and a low-oxygen (LO) mixture containing 2.5% O2. The vials were incubated at 33°C, and the growth index (GI) was measured at 1, 2, 3, and 4 weeks in a BACTEC 460 TB instrument (Becton Dickinson). In all instances, growth under LO conditions gave GI values higher than those under AE conditions. After 1 and 2 weeks of incubation, the median GI under LO conditions was 46.1 and 31.2% higher, respectively (Fig. 1), but this difference decreased to 26.4% after 3 weeks, and no difference was seen after 4 weeks of incubation (data not shown). When evaluating the growth of M. ulcerans in terms of the proportion of strains reaching a GI of 999 under the two oxygen concentrations, we found that the percentage of strains reaching this value increased earlier under LO conditions, and at the end of the 4-week observation period it reached 93.3%, while under AE conditions only 66.6% of the strains achieved the maximum GI (Fig. 2).

FIG. 1.

Growth of 15 strains of M. ulcerans under AE (■) and LO (▤) conditions in the BACTEC system. The numbers 1 to 15 indicate individual strains at 1 (A) and 2 (B) weeks.

FIG. 2.

Percentage of strains reaching the maximum GI of 999 after increasing length of incubation in the BACTEC system.

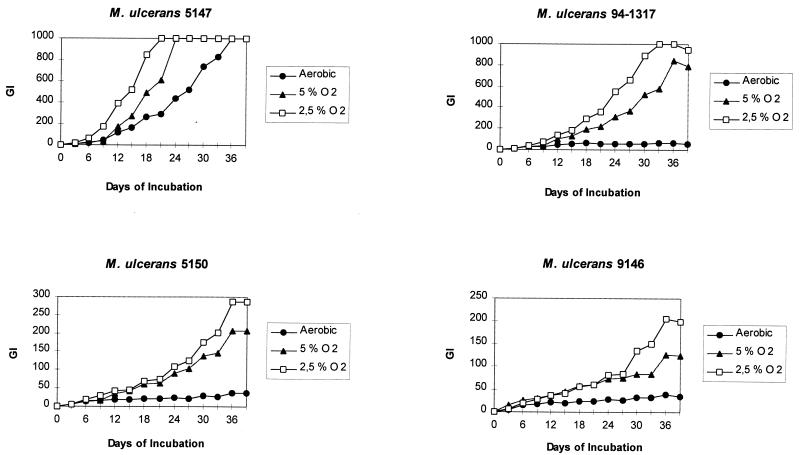

The influence of oxygen tension was studied in greater detail on three M. ulcerans isolates from the ITM collection (no. 5150, 9146, and 94-1317) and the type strain, ATCC 19423 (no. 5147). Bacterial suspensions were prepared as before and tested with an inoculum of 105 bacilli; GI measurements were made twice a week (Fig. 3). The growth of ATCC 19423 was stimulated at the lower concentration of oxygen (2.5%), reaching the maximum GI of 999 after 21 days of incubation; by contrast, under AE conditions (21% O2) the GI at that time was 295. At 5% O2 the growth reached a GI of 999 at day 24. Growth stimulation was thus directly proportional to the decrease in oxygen concentration. Experiments with the other isolates showed similar results. The growth of strain 94-1317, of Australian origin, was strongly stimulated at the lower oxygen concentrations. The African isolates, 5150 and 9146, were also stimulated at lower oxygen levels, but not as luxuriantly as were the Australian isolates. The previously described genotypic variations among M. ulcerans strains from different geographic origins (13) could explain in part some phenotypic differences, e.g., the response to external factors, such as the effects of various decontamination methods on M. ulcerans (10). Although we did not observe major strain-related differences in the effect of oxygen concentrations on M. ulcerans from different geographic origins, further study of this question is warranted because of a possible influence of oxygen tension on the successful isolation of M. ulcerans in primary culture. Krieg et al. (8) showed a salutary effect of hyperbaric oxygen on M. ulcerans infection in a murine model. One possible explanation for this effect is the suppression of growth of M. ulcerans at high oxygen tension. Very recently Cunningham and Spreadbury (4) cultivated Mycobacterium bovis BCG and M. tuberculosis H37Rv under reduced oxygen tension and found thickening of the outer layer of the cell wall and a highly expressed 16-kDa small heat shock protein, which could explain the adaptation of tubercle bacilli to a dormant state under adverse conditions. Similar observations of M. ulcerans grown under low oxygen tension would be interesting. Because of the presumed very low oxygen levels in necrotic lesions of BU, M. ulcerans may survive in a dormant form and reactivate at sites of trauma (9) after corticoid therapy (15) or other untoward events (1). Wayne and Hayes showed that, when gradually adapted to a microaerophilic environment, M. tuberculosis expressed increased tolerance to anaerobiosis and was susceptible to antibiotics normally active against anaerobic bacteria (17). There are few studies concerning the activity of antibiotics in vitro against M. ulcerans (11), and it is postulated that the unsuccessful application of some antibiotics in vivo results from poor penetration of the drugs into necrotic tissue (6). Antimicrobial therapy of M. ulcerans infection based on the assumption that M. ulcerans in necrotic tissue is microaerophilic should be pursued. This preference of M. ulcerans for low oxygen concentrations should be considered in developing improved culture methods for the isolation of the bacterium in primary culture and in attempts to isolate the bacterium from the environment.

FIG. 3.

Effect of different oxygen concentrations on strains of M. ulcerans in the BACTEC system.

Acknowledgments

This study was partly supported by the Fonds National de la Recherche Scientifique, Belgium (grant no. 15.192.95F), and by the Damien Foundation, Belgium. J. C. Palomino was financially supported by the European Commission through contract CI1*-CT94-0556 and by the Damien Foundation, Belgium. L. Realini was supported by a grant from the Fonds National Suisse de la Recherche Scientifique (grant 3139-039166) and by the Damien Foundation, Belgium.

We thank Becton Dickinson for use of the BACTEC 460 TB instrument and for culture media used in this study.

REFERENCES

- 1.Aguiar J, Domingo M C, Guedenon A, Meyers W, Steunou C, Portaels F. L’ulcère de Buruli, une maladie mycobactérienne importante et en recrudescence au Benin. Bull Séanc Acad Sci Outre-Mer. 1997;43:325–356. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Clancey J K, Dodge O G, Lunn H F, Odouri M L. Mycobacterial skin ulcers in Uganda. Lancet. 1961;i:951–954. doi: 10.1016/s0140-6736(61)90793-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Cornet L, Richard-Kadio M, N’Guessan H A, Yapo P, Hossoko H, Dick R, Casanelli J M. Treatment of Buruli ulcers by excision-graft. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1992;85:355–358. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Cunningham A F, Spreadbury C L. Mycobacterial stationary phase induced by low oxygen tension: cell wall thickening and localization of the 16-kilodalton α-crystallin homolog. J Bacteriol. 1998;180:801–808. doi: 10.1128/jb.180.4.801-808.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Darie H, Le Guyadec T, Touze J E. Epidemiological and clinical aspects of Buruli ulcer in Ivory Coast. 124 recent cases. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1993;86:272–276. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Goutzamanis J J, Gilbert G L. Mycobacterium ulcerans infection in Australian children: report of eight cases and review. Clin Infect Dis. 1995;21:1186–1192. doi: 10.1093/clinids/21.5.1186. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Josse R, Guedenon A, Aguiar J, Anagonou S, Zinsou C, Prost C, Foundohou J, Touze J E. Buruli ulcer, a pathology little known in Benin. Apropos of 227 cases. Bull Soc Pathol Exot. 1994;87:170–175. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Krieg R E, Wolcott J H, Meyers W M. Mycobacterium ulcerans infection: treatment with rifampin, hyperbaric oxygenation and heat. Aviat Space Environ Med. 1979;50:888–892. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Lindo S D, Daniels S F. Buruli ulcer in New York City. JAMA. 1974;228:1138–1139. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Palomino J C, Portaels F. Effect of decontamination methods and culture conditions on viability of Mycobacterium ulcerans in the BACTEC system. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:402–408. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.2.402-408.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Portaels F, Traore H, De Ridder K, Meyers W M. In vitro susceptibility of Mycobacterium ulcerans to clarithromycin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1998;42:2070–2073. doi: 10.1128/aac.42.8.2070. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Portaels F, Aguiar J, Fissette K, Fonteyne P A, De Beenhouwer H, de Rijk P, Guedenon A, Lemans R, Steunou C, Zinsou C, Dumonceau J M, Meyers W M. Direct detection and identification of Mycobacterium ulcerans in clinical specimens by PCR and oligonucleotide-specific capture plate hybridization. J Clin Microbiol. 1997;35:1097–1100. doi: 10.1128/jcm.35.5.1097-1100.1997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Portaels F, Fonteyne P-A, de Beenhouwer H, de Rijk P, Guédénon A, Hayman J, Meyers W M. Variability in 3′ end of 16S rRNA sequence of Mycobacterium ulcerans is related to geographic origin of isolates. J Clin Microbiol. 1996;34:962–965. doi: 10.1128/jcm.34.4.962-965.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Portaels, F., A. Guimaraes Peres, J. Aguiar, M. C. Domingo, P. de Rijk, A. Guédénon, K. Fissette, P. A. Fonteyne, C. Van Schaverbeeck, C. Steunou, and W. M. Meyers. Unpublished data.

- 15.Prasad R. Pulmonary sarcoidosis and chronic cutaneous atypical mycobacterium ulcer. Aust Fam Physician. 1993;22:755–758. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Realini L, De Ridder K, Palomino J-C, Hirschel B, Portaels F. Microaerophilic conditions promote growth of Mycobacterium genavense. J Clin Microbiol. 1998;36:2565–2570. doi: 10.1128/jcm.36.9.2565-2570.1998. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Wayne L G, Hayes L G. An in vitro model for sequential study of shiftdown of Mycobacterium tuberculosis through two stages of nonreplicating persistence. Infect Immun. 1996;64:2062–2069. doi: 10.1128/iai.64.6.2062-2069.1996. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]