Abstract

An association between Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) and gastric carcinoma has been studied through the EBV genome present in the carcinoma cells. Recently, we found that EBV DNA in paraffin-embedded gastric carcinoma tissue was detected effectively by PCR after pretreatment of the extracted DNA with a restriction enzyme, BamHI or EcoRI. Here, we show that the PCR amplification was also enhanced by pretreatment of the DNA with other restriction enzymes or with bovine serum albumin and several other proteins. Treatment with these proteins may remove a PCR inhibitor(s) in the DNA samples extracted from the paraffin blocks.

Epstein-Barr virus (EBV) infection was observed in 7% of gastric carcinoma patients in Japan (6, 8, 15, 24) and was detected with high frequency in gastric carcinoma with lymphoid stroma (15, 16, 21), suggesting that EBV may be associated with pathogenesis. Recent studies of EBV-associated early gastric carcinoma have suggested that EBV infection may occur in the atrophic gastric epithelial cells associated with intestinal metaplasia and in the nonneoplastic gastric epithelium (3, 10). To address the question of when EBV infection occurs in the development of EBV-associated gastric carcinoma, retrospective detection of EBV genomes becomes more important. Paraffin-embedded tissue is excellent material for identifying the presence of viral genes or mutated oncogenes in carcinomas, since the tissue has been kept for many years and can easily be retested. It has been reported that DNA extracted from paraffin blocks was usable for the amplification of β-globin gene alleles (9), papillomavirus DNA (22), and EBV DNA (17) by PCR. On the other hand, DNA from paraffin blocks has been reported to be unsuitable material for PCR, because it was not intact (7), had compromised efficiency of amplification (4), and contained PCR inhibitors (2, 13). Several methods to remove (2, 5, 12) or dilute (1, 14) the inhibitors and rapid methods to prepare DNA for PCR (11, 20) have been reported. We observed that EBV DNA was not well amplified from DNA extracted from paraffin-embedded gastric carcinoma tissue, for unknown reasons; however, amplification was achieved by pretreating the DNA with BamHI or EcoRI restriction enzyme (23). Here, we have extended the effective detection of EBV DNA on PCR by pretreatment of the extracted DNA with other restriction enzymes, bovine serum albumin (BSA), and several other proteins.

Specimens of paraffin-embedded gastric carcinoma tissue from different patients were used for this study. Some of them were derived from gastric carcinoma with lymphoid stroma (16). Twenty 10-μm slices were deparaffinized, and DNA was prepared by proteinase K digestion, phenol-chloroform extraction, and ethanol precipitation and dissolved in 1 ml of TE (10 mM Tris-HCl, pH 8.0, 1 mM EDTA). Primers (5′CCAGACAGCAGCCAATTGTC and 5′GGTAGAAGACCCCCTCTTAC) were used to amplify a 129-bp fragment of the BamHI-W region of EBV DNA (25). The PCR products were detected by Southern blot analysis according to the described method (23) with a sequence-specific oligonucleotide probe (5′CCCTGGTATAAAGTGGTCCTGCAGCTATTTCTGGTCGCATC) 5′ end labeled with [γ-32P]ATP (26).

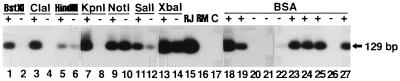

We tested whether the EBV DNA was amplified by pretreatment of the extracted DNA with the restriction enzymes BstXI, ClaI, HindIII, KpnI, NotI, SalI, and XbaI (Fig. 1). Five microliters (1.8 μg) of DNA from a patient with EBV-encoded small RNA (EBER)-positive gastric carcinoma (16) was incubated at 37°C for 1 h with each enzyme (10 U; Takara Shuzo Co., Ltd., Kyoto, Japan) in 10 μl of a mixture containing 50 mM Tris-HCl (pH 7.5), 10 mM MgCl2, 1 mM dithiothreitol and 100, 50, or 0 mM NaCl. The control was incubated without the enzyme. The mixture was incubated at 60°C for 15 min to inactivate the enzyme, and the DNA was ethanol precipitated, dissolved in 5 μl of TE, and subjected to PCR in a 50-μl mixture.

FIG. 1.

Enhancement of PCR amplification of the EBV genome by pretreatment of the extracted DNA with a restriction enzyme or BSA. The extracted DNA from paraffin-embedded gastric carcinoma tissue was (+) or was not (−) pretreated with a restriction enzyme (lanes 1 to 14) or BSA (lanes 18 to 27), as described in the text. The DNA was subjected to PCR-Southern analysis of the BamHI-W region. EBV genome-positive Raji cell DNA (RJ) (lane 15), EBV genome-negative Ramos cell DNA (RM) (lane 16), and nonpretreated DNA (C) (lane 17) were subjected to PCR as controls. The 129-bp PCR product is indicated by an arrow.

Pretreatment of the extracted DNA with BstXI (Fig. 1, lane 1), ClaI (lane 3), HindIII (lane 5), KpnI (lane 7), or SalI (lane 11) resulted in positive PCR, while the control without enzyme showed either no signal of amplification (Fig. 1, lanes 2, 4, and 8) or a faint one (lanes 6 and 12). PCR of DNA pretreated with NotI (Fig. 1, lane 9) and XbaI (lane 13) showed amplification; however, in both cases, to our surprise the signal was also observed in the controls (lanes 10 and 14). As for reasons for the amplification, we noticed that BSA was contained in the original buffers for NotI and XbaI alone, according to the manufacturer’s recommendation. When the BSA was excluded from the buffers, either no signal or a faint one was observed in the samples (data not shown). These results indicated that the amplification was induced by not only BamHI or EcoRI but also by the other restriction enzymes or BSA.

The effect of BSA pretreatment on PCR was analyzed in more detail. Amplification was improved with BSA (0.01%; Takara Shuzo Co., Ltd.) (Fig. 1, lanes 18, 19, and 23) compared to amplification of the controls without BSA (lanes 20 to 22). The effect of BSA was confirmed by using another BSA (Fig. 1, lane 24) from a different company (Wako Pure Chemical Ind., Ltd., Osaka, Japan). The effect was also observed with DNase- and RNase-free BSA (Pharmacia Biotech, Uppsala, Sweden) (Fig. 1, lane 25) and in a TE buffer which lacked MgCl2, an essential element for DNase activity (lane 27), while no signal was observed in the control without BSA (lane 26). These results indicated that the effect of BSA was not due to the contamination of nuclease in BSA. The effect (Fig. 1, lane 18) was observed even if the BSA was removed after the pretreatment (lane 19). On the other hand, the addition of BSA to the PCR mixture of the DNA sample which was not pretreated with BSA did not show the amplification signal (Fig. 1, lane 21). These results indicated that BSA exerted its action in pretreatment but not in the PCR itself.

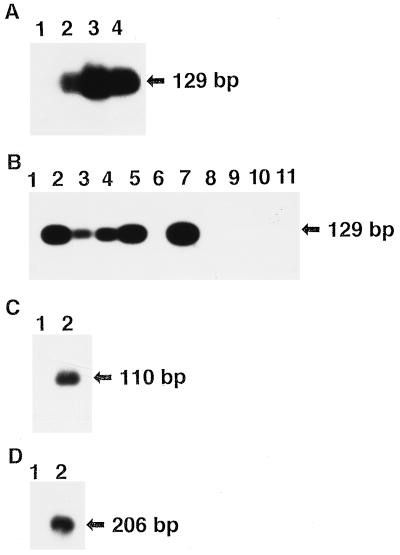

We hypothesized that an inhibitor(s) of PCR may exist in the extracted DNA and may be removed by BSA treatment. When the DNA extracted from the paraffin-embedded gastric carcinoma tissue was purified by adsorption to silica (27), the amplification of EBV DNA was greatly improved (Fig. 2A, lane 3) over that of the nonpurified DNA (lane 1). However, further enhancement of amplification was not observed with BSA pretreatment of the purified DNA (Fig. 2A, lane 4), while it was observed in the unpurified DNA (lane 2). This result is consistent with the conclusion that the DNA extracted from paraffin blocks contains a PCR inhibitor(s) whose action is overcome by preincubation with BSA.

FIG. 2.

Effect of purification of extracted DNA, BSA, and various proteins on the PCR in DNA from a gastric carcinoma. The extracted DNA in Fig. 1 was used for these experiments. (A) DNA was purified by binding to and elution from silica membrane (SpinBind DNA recovery system; FMC Bioproducts, Rockland, Maine). The nonpurified DNA (lanes 1 and 2) and the purified DNA (lanes 3 and 4) were not pretreated (lanes 1 and 3) or were pretreated with BSA (lanes 2 and 4) and were subjected to PCR of the BamHI-W region of EBV. The PCR product is detected at 129 bp. (B) DNA was not pretreated (lane 1) or was pretreated with BSA (lane 2), α2 macroglobulin (lane 3), phosphorylase b (lane 4), lactate dehydrogenase (lane 5), soybean trypsin inhibitor (lane 6), lysozyme (lane 7), proteinase K (lane 8), S. caespitosus protease (lane 9), C. histolyticum collagenase (lane 10), or lima bean trypsin inhibitor (lane 11) and was subjected to PCR analysis. The PCR product is shown at 129 bp. (C) DNA was subjected to PCR of the β-globin gene (the arrow indicates the 110-bp PCR product of the β-globin gene) (18), without pretreatment (lane 1) or with pretreatment with BSA (lane 2). (D) DNA was subjected to PCR for the EGF receptor gene (the arrow indicates the 206-bp PCR product of the EGF receptor gene) (19), without pretreatment (lane 1) or with pretreatment with BSA (lane 2).

We also tested the effect of the pretreatment of DNA with several other proteins at 0.01%, which were selected from the categories of protease inhibitors, carrier proteins like BSA, and enzymes other than nuclease. We found that the four proteins equine plasma α2 macroglobulin (Boehringer Mannheim, Mannheim, Germany) (Fig. 2B, lane 3), rabbit muscle phosphorylase b (Boehringer Mannheim) (Fig. 2B, lane 4), rabbit muscle lactate dehydrogenase (Boehringer Mannheim) (Fig. 2B, lane 5), and chicken egg white lysozyme (Wako Pure Chemical Ind., Ltd.) (Fig. 2B, lane 7) had effects similar to those of BSA (Fig. 2B, lane 2). The chicken egg white trypsin inhibitor (Sigma, St. Louis, Mo.) (not shown) had a much smaller effect than BSA. On the other hand, the five proteins soybean trypsin inhibitor (Boehringer Mannheim) (Fig. 2B, lane 6), lima bean trypsin inhibitor (Worthington Biochemical Corp., Freehold, N.J.) (Fig. 2B, lane 11), Tritirachium album proteinase K (Merck KGaA, Darmstadt, Germany) (Fig. 2B, lane 8), Streptomyces caespitosus protease (Sigma) (Fig. 2B, lane 9), and Clostridium histolyticum collagenase (Sigma) (Fig. 2B, lane 10) had no effect. Thus, the five animal proteins—albumin, lysozyme, lactate dehydrogenase, phosphorylase b, and α2 macroglobulin—may have an affinity for the removal of the putative inhibitor(s), while plant or microbial proteins may not have the affinity. BSA also enhanced the amplification of cellular genes for β-globin (Fig. 2C, lane 2) and epidermal growth factor (EGF) receptor (Fig. 2D, lane 2).

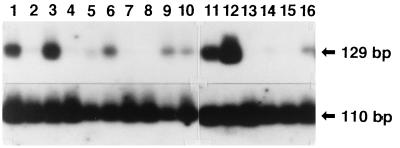

Using BSA pretreatment, we detected EBV DNA in 9 of 16 specimens of gastric carcinoma, while the β-globin gene was well amplified for all of the specimens (Fig. 3). The specimens were tested for the expression of EBER by in situ hybridization (16). The PCR-negative specimens were negative for EBER. The PCR-positive specimens shown in Fig. 3, lanes 1, 3, 11, and 12, were positive for EBER, and those in lanes 5, 6, 9, 10, and 16 were negative for EBER. Therefore, we concluded that the four EBER-positive specimens (Fig. 3, lanes 1, 3, 11, and 12) were from EBV-infected gastric carcinomas.

FIG. 3.

Detection of EBV DNA in samples extracted from paraffin blocks containing gastric carcinoma tissue from different patients. DNAs extracted from 16 specimens (lanes 1 to 16) were treated with BSA and subjected to PCR for EBV DNA (top) and the β-globin gene (bottom). The specimen in lane 1 was also used in the experiments shown in Fig. 1 and 2. No PCR amplification was observed in any of the specimens which did not have BSA treatment (data not shown).

In conclusion, BSA pretreatment is a useful method for the detection of EBV DNA by PCR of the DNA extracted from paraffin blocks and could be applicable in the detection of other viral and cellular DNAs.

REFERENCES

- 1.Abe K. Kangan parafin houmai byouri kentai yorino Bgata, Cgata kan-en uirusu no kenshyutu. Byouri To Rinshyou. 1996;14:276–280. . (In Japanese.) [Google Scholar]

- 2.An S F, Fleming K A. Removal of inhibitor(s) of the polymerase chain reaction from formalin fixed, paraffin wax embedded tissues. J Clin Pathol. 1991;44:924–927. doi: 10.1136/jcp.44.11.924. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Arikawa J, Tokunaga M, Satoh E, Tanaka S, Land C E. Morphological characteristics of Epstein-Barr virus-associated early gastric carcinoma: a case-control study. Pathol Int. 1997;47:360–367. doi: 10.1111/j.1440-1827.1997.tb04509.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Coates P J, d’Ardenne A J, Khan G, Kangro H O, Slavin G. Simplified procedures for applying the polymerase chain reaction to routinely fixed paraffin wax sections. J Clin Pathol. 1991;44:115–118. doi: 10.1136/jcp.44.2.115. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.de Franchis R, Cross N C, Foulkes N S, Cox T M. A potent inhibitor of Taq polymerase copurifies with human genomic DNA. Nucleic Acids Res. 1988;16:10355. doi: 10.1093/nar/16.21.10355. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Fukayama M, Hayashi Y, Chong J, Ooba T, Takizawa T, Koike M, Mizutani S, Miyaki M, Hirai K. Epstein-Barr virus-associated gastric carcinoma and Epstein-Barr virus infection of the stomach. Lab Investig. 1994;71:73–81. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Goelz S E, Hamilton S R, Vogelstein B. Purification of DNA from formaldehyde fixed and paraffin embedded human tissue. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1985;130:118–126. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(85)90390-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Imai S, Koizumi S, Sugiura M, Tokunaga M, Uemura Y, Yamamoto N, Tanaka S, Sato E, Osato T. Gastric carcinoma: monoclonal epithelial malignant cells expressing Epstein-Barr virus latent infection protein. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1994;91:9131–9135. doi: 10.1073/pnas.91.19.9131. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Impraim C C, Saiki R K, Erlich H A, Teplitz R L. Analysis of DNA extracted from formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues by enzymatic amplification and hybridization with sequence-specific oligonucleotides. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 1987;142:710–716. doi: 10.1016/0006-291x(87)91472-0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Jing X, Nakamura Y, Nakamura M, Yokoi T, Shan L, Taniguchi E, Kakudo K. Detection of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in gastric carcinoma with lymphoid stroma. Viral Immunol. 1997;10:49–58. doi: 10.1089/vim.1997.10.49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kiene P, Milde-Langosch K, Runkel M, Schulz K, Löning T. A simple and rapid technique to process formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded tissues for the detection of viruses by the polymerase chain reaction. Virchows Arch A Pathol Anat Histopathol. 1992;420:269–273. doi: 10.1007/BF01600280. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Lampertico P, Malter J S, Colombo M, Gerber M A. Detection of hepatitis B virus DNA in formalin-fixed, paraffin-embedded liver tissue by the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Pathol. 1990;137:253–258. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lo Y-M D, Mehal W Z, Fleming K A. In vitro amplification of hepatitis B virus sequences from liver tumor DNA and from paraffin wax embedded tissues using the polymerase chain reaction. J Clin Pathol. 1989;42:840–846. doi: 10.1136/jcp.42.8.840. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lo Y-M D, Lo E S-F, Mehal W Z, Sampietro M, Fiorelli G, Ronchi G, Tse C H. Geographical variation in prevalence of hepatitis B virus DNA in DNA in HBsAg negative patients. J Clin Pathol. 1993;46:304–308. doi: 10.1136/jcp.46.4.304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Min K W, Holmquist S, Peiper S C, O’Leary T J. Poorly differentiated adenocarcinoma with lymphoid stroma (lymphoepithelioma-like carcinomas) of the stomach. Report of three cases with Epstein-Barr virus genome demonstrated by polymerase chain reaction. Am J Clin Pathol. 1991;96:219–227. doi: 10.1093/ajcp/96.2.219. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ohfuji S, Osaki M, Tsujitani S, Ikeguchi M, Sairenji T, Ito H. Low frequency of apoptosis in Epstein-Barr virus associated gastric carcinoma with lymphoid stroma. Int J Cancer. 1996;68:710–715. doi: 10.1002/1097-0215(19961211)68:6<710::aid-ijc2910680602>3.0.co;2-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rogers B B, Alpert L C, Hine E A S, Buffone G J. Analysis of DNA in fresh and fixed tissue by the polymerase chain reaction. Am J Pathol. 1990;136:541–548. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Saiki R K, Bugawan T L, Horn G T, Mullis K B, Erlich H A. Analysis of enzymatically amplified β-globin and HLA-DQ α DNA with allele-specific oligonucleotide probes. Nature. 1986;324:163–166. doi: 10.1038/324163a0. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Satoh Y, Oomae M, Hoshikawa Y, Izawa M, Sairenji T, Ichii S. The truncated epidermal growth factor receptor mRNA is more stable than full-length receptor mRNAs in rat hepatoma cells. Endocr J. 1997;44:403–408. doi: 10.1507/endocrj.44.403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Sepp R, Szabo I, Uda H, Sakamoto H. Rapid techniques for DNA extraction from routinely processed archival tissue for use in PCR. J Clin Pathol. 1994;47:318–323. doi: 10.1136/jcp.47.4.318. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Shibata D, Tokunaga M, Uemura Y, Sato E, Tanaka S, Weiss L M. Association of Epstein-Barr virus with undifferentiated gastric carcinomas with intense lymphoid infiltration. Lymphoepithelioma-like carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1991;139:469–474. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Shibata D K, Arnheim N, Martin W J. Detection of human papilloma virus in paraffin-embedded tissues using the polymerase chain reaction. J Exp Med. 1988;167:225–230. doi: 10.1084/jem.167.1.225. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Takasaka N, Satoh Y, Hoshikawa Y, Osaki M, Ito H, Chen J-Y, Sairenji T. Improvements in the detection of Epstein-Barr virus DNA on paraffin-embedded gastric carcinoma tissues: treatment of extracted cellular DNA with a restriction enzyme prior to polymerase chain reaction. Yonago Acta Med. 1996;39:171–176. [Google Scholar]

- 24.Tokunaga M, Land C E, Uemura Y, Tokudome T, Tanaka S, Sato E. Epstein-Barr virus in gastric carcinoma. Am J Pathol. 1993;143:1250–1254. [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Tomita Y, Ohsawa M, Mishiro Y, Kubo T, Maeshiro N, Kojya S, Noda Y, Aozasa K. The presence and subtype of Epstein-Barr virus in B and T cell lymphomas of the sino-nasal region from the Osaka and Okinawa districts of Japan. Lab Investig. 1995;73:190–196. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Uhara H, Sato Y, Mukai K, Akao I, Matsuno Y, Furuya S, Hoshikawa T, Shimosato Y, Saida T. Detection of Epstein-Barr virus DNA in Reed-Sternberg cells of Hodgkin’s disease using polymerase chain reaction and in situ hybridization. Jpn J Cancer Res. 1990;81:272–278. doi: 10.1111/j.1349-7006.1990.tb02561.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vogelstein B, Gillespie D. Preparative and analytical purification of DNA from agarose. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 1979;76:615–619. doi: 10.1073/pnas.76.2.615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]