Abstract

Introduction

Sessile serrated lesions (SSLs) have malignant potential for colorectal cancer in the serrated pathway. Selective endoscopic resection of SSLs would reduce medical costs and procedure-related accidents, but the accurate endoscopic differentiation of SSLs from hyperplastic polyps (HPs) is challenging. To explore the differential diagnostic performance of magnifying colonoscopy in distinguishing SSLs from HPs, we conducted a multicenter prospective validation study in clinical practice.

Methods

Considering the rarity of diminutive SSLs, all lesions ≥6 mm that were detected during colonoscopy and diagnosed as type 1 based on the Japan narrow-band imaging expert team (JNET) classification were included in this study. Twenty expert endoscopists were asked to differentiate between SSLs and HPs with high or low confidence level after conventional and magnifying NBI observation. To examine the validity of selective endoscopic resection of SSLs using magnifying colonoscopy in clinical practice, we calculated the sensitivity of endoscopic diagnosis of SSLs with histopathological findings as comparable reference.

Results

A total of 217 JNET type 1 lesions from 162 patients were analyzed, and 114 lesions were diagnosed with high confidence. The sensitivity of magnifying colonoscopy in detecting SSLs was 79.8% (95% confidence interval [CI]: 74.7–84.4%) overall, and 82.4% (95% CI: 76.1–87.7%) in the high-confidence group. These results showed that the sensitivity of this study was not high enough, even limited in the high-confidence group.

Conclusions

Accurate differential diagnosis of SSLs and HPs using magnifying colonoscopy was challenging even for experts. JNET type 1 lesions ≥6 mm are recommended to be resected because selective endoscopic resection has a disadvantage of leaving approximately 20% of SSLs on site.

Keywords: Sessile serrated lesions, Differential diagnosis, Selective endoscopic resection, Multicenter prospective study

Introduction

Colorectal cancer (CRC) is the third most common cancer worldwide [1], and adenomas were long thought to be the only precursor lesion for CRC development. However, colorectal serrated lesions have emerged as another key pathway contributing to CRC development, and it is now believed that a significant portion of sporadic CRC arises from serrated precursor lesions [2, 3]. In colorectal serrated lesions, traditional serrated adenomas, sessile serrated lesions (SSLs), and SSLs with dysplasia (SSLDs) are considered to be precursors to CRC.

Although no clear endoscopic diagnostic criteria exist for SSLs, the European Society of Gastrointestinal Endoscopy recommends in their guidelines that all polyps should be resected except for diminutive (≤5 mm) rectal and rectosigmoid polyps that are predicted to be hyperplastic with high confidence (HC) [4]. On the other hand, if SSLs could be discriminated from hyperplastic polyps (HPs) and selectively resected, it would reduce medical costs, procedure-related accidents, and the burden on patients and endoscopists. We have revealed that the percentage of SSLs in serrated lesions increases with size and that the percentage of SSLDs in SSLs also increases with the size, and all SSLDs were 6 mm or larger [5, 6]. Although several studies on the clinical and endoscopic characteristics of SSLs have been reported [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22], they were mostly designed as either single-center retrospective or prospective studies using still images. No multicenter prospective study has been performed to determine whether endoscopists can accurately differentiate between SSLs and HPs in clinical practice.

The Japan narrow-band imaging (NBI) expert team (JNET) classification, the latest magnifying NBI classification, has high diagnostic performance in differentiating neoplasm from non-neoplasm and in predicting the distance of cancer invasion [23, 24, 25]. Thus, it has been widely used for endoscopic diagnosis of colorectal lesions. Of note, JNET type 1 lesions include both SSLs and HPs, and it is still unclear whether SSLs and HPs can be distinguished. In recent years, there have been discussions that assume that SSLs can be differentiated from HPs and selectively resected. We recognize the weaknesses and limitations of endoscopic diagnosis and anticipate that accurate differential diagnosis of SSLs in JNET type 1 lesions may be challenging in clinical practice. To explore the differential diagnostic performance of magnifying colonoscopy in distinguishing SSLs from HPs, we conducted a multicenter prospective study of the differential diagnosis of SSLs in JNET type 1 lesions in clinical practice.

Materials and Methods

This prospective study was performed at four endoscopy centers (one university hospital, two regional core hospitals, and one high-volume endoscopy center) and conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Clinical Research Act. This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Review Committee on December 5th, 2019 (case number: 201912-02); it was also preregistered in UMIN-CTR (University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Research Registration System) as UMIN 000037543.

Patients

All patients aged 20 years or older with at least one JNET type 1 lesion ≥6 mm who underwent colonoscopy at one of the four endoscopy centers were included. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. Pregnant or lactating patients, patients with a history of colectomy (excluding appendicectomy), taking antiplatelet or anticoagulant medication, with inflammatory bowel disease, polyposis coli, or CRC, and other concomitant severe diseases were excluded.

Endoscopists and Quality Control

Twenty expert endoscopists were involved in this study and were defined as fellows qualified by the Japan Gastroenterological Endoscopy Society, including three founding members of the JNET classification. These 20 expert endoscopists were authorized after receiving a 2-h lecture on recent reports and reviews on the endoscopic features of SSLs. No further quality control was performed because it would have taken away from the current state of actual clinical practice.

Endoscopic and Histopathological Diagnosis of SSL

Whenever the endoscopist detected a lesion ≥6 mm during colonoscopy, he or she first performed magnifying NBI and made a diagnosis according to the JNET classification. If the lesion was suspected to be JNET type 1, detailed re-evaluation with white light imaging and NBI were consecutively performed. Based on these observations, a diagnosis of SSL or HP was made and recorded. Additionally, the confidence level of the endoscopic diagnosis and the presence or absence of the findings of each of the eight candidates were recorded. The diameter and location of each lesion were also registered. Regarding the location, the right colon was defined to be proximal to the splenic flexure.

The diagnostic criteria for SSL in this study were not strictly defined. Each endoscopist diagnosed SSL or HP by considering comprehensive findings obtained through endoscopic observations because there is no consensus regarding the diagnostic criteria for SSL and because diagnosis is made based on the comprehensive judgment of each endoscopist in clinical practice.

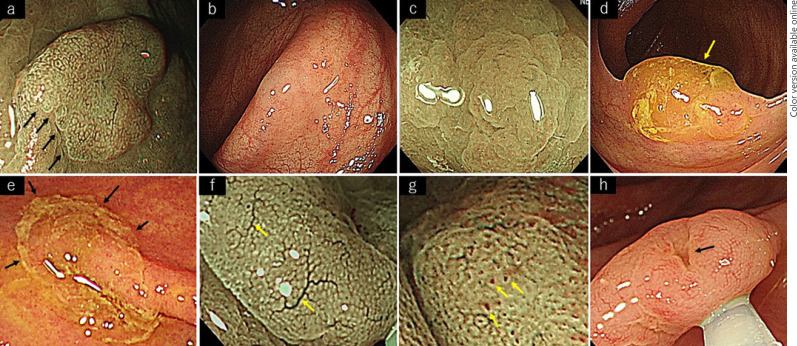

The following eight terminologies were enrolled to describe the endoscopic features suggestive of SSLs: irregular shape, indistinctive border, cloud-like surface, mucus cap, rim of debris, dilated vessels, dilated crypts, and inverted growth pattern. These eight features were the characteristic findings of sessile serrated adenoma/polyps (SSAPs) [26]. There was still no consensus regarding endoscopic findings of SSLs; the diagnosis of SSL was made based on the findings of SSAPs in clinical practice. Therefore, these eight features of SSAPs were adopted by the candidates as their characteristic findings of SSLs. These eight candidate findings of SSLs are shown in Figure 1. For each JNET type 1 lesion ≥6 mm, all eight findings had to be marked as either present or absent simultaneously. Subsequently, the endoscopic treatment was performed for all JNET type 1 lesions ≥6 mm, and the resected specimen was submitted for histopathological examination. The pathological diagnosis was made in each institution, and all pathologists were blinded to the study. These endoscopic and histopathological diagnoses were collected independently and registered in a database. Lesions for which histopathological tissue could not be retrieved and lesions with a histopathological diagnosis other than SSL or HP were excluded from the analysis.

Fig. 1.

Eight candidate findings of SSLs. a Irregular shape. b Indistinctive border. c Cloud-like surface. d Mucus cap. e Rim of debris. f Dilated vessels. g Dilated crypts. h Inverted growth pattern.

Histopathological diagnosis was based on the 5th edition of the World Health Organization (WHO) Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System, published in 2019 [27]. Histological criteria for sessile lesions and polyps: a single unequivocal distorted crypt was the only requirement for the diagnosis of a SSL. The distortion of crypt architecture can include horizontal growth along the muscularis mucosae, dilatation of the crypt base, serrations extending into the crypt base, and asymmetrical proliferation. Flat serrated lesions/polyps with no typical SSL-type crypts are diagnosed as HPs by exclusion. Mild symmetrical crypt dilatation, occasional branching, and goblet cells at the base of crypts are insufficient for the diagnosis of SSL.

Study Outcomes

For examining the validity of selective endoscopic resection of SSLs using magnifying colonoscopy in clinical practice, we used the sensitivity of endoscopic diagnosis of SSLs in JNET type 1 lesion ≥6 mm in the analysis. Since it is clinically important to prevent leaving SSLs on site, the sensitivity of endoscopic diagnosis was at most suitable measure for the description. The diagnostic performance, such as specificity, positive predictive value, and negative predictive value of SSLs in JNET type 1 lesions ≥6 mm was also calculated by comparing the endoscopic diagnosis with the histopathological diagnosis as the gold standard. The usefulness of the differential diagnosis was statistically analyzed and judged by whether the upper limit of the 95% confidence interval (CI) for sensitivity reached 90%. If the upper limit of the 95% CI for sensitivity did not reach 90%, the differential diagnosis is not sensitive enough, and selective endoscopic resection is not recommended due to the risk of leaving more than 10% SSLs on site.

We also analyzed to what extent the combined use of confidence levels contributed to improving the diagnostic performance. The diagnostic performance in the HC group, low confidence group, and overall were compared. In addition, the appearance ratio of the eight characteristic findings in the SSL and HP groups was calculated. Furthermore, multivariate logistic regression analysis was performed to determine the usefulness of the eight characteristic findings in the differential diagnosis of SSL.

Sample Size Calculation

We tried to set a sample size to get a reasonable width of CI of sensitivity. This calculation was based on earlier studies [7, 8, 9, 10, 11, 12, 13, 14, 15, 16, 17, 18, 19, 20, 21, 22, 26]. The earlier study of Yamashina et al. reported the diagnostic performance: sensitivity of 0.84 (0.71–0.93) for SSL diagnosis based on dilated crypts [20]. Based on this report, we calculated the sample size that the sensitivity was 0.84 and their upper 95% confidence limit was 90% (n = 144). In this calculation, no multiple lesions in the same cases were admitted. Considering the potential case of multiple lesions in 1 case, we finally set 180 lesions for the required numbers for enrollment in this study.

Statistical Analyses

For the sensitivity, the Fisher's exact test for binary data and the Mann-Whitney U test for countable data were used. For exploring the usefulness of the eight characteristic findings, a multivariate logistic regression model was used to estimate odds ratios and 95% CIs. This model included the following eight variables: irregular shape, indistinct border, cloud-like surface, mucus cap, rim of debris, dilated vessels, dilated crypts, and inverted growth pattern. R Version 4.0.0 (R Core Team 2020, Vienna, Austria) was used for the statistical analysis in this study. p < 0.05 was considered statistically significant.

Results

Study Population

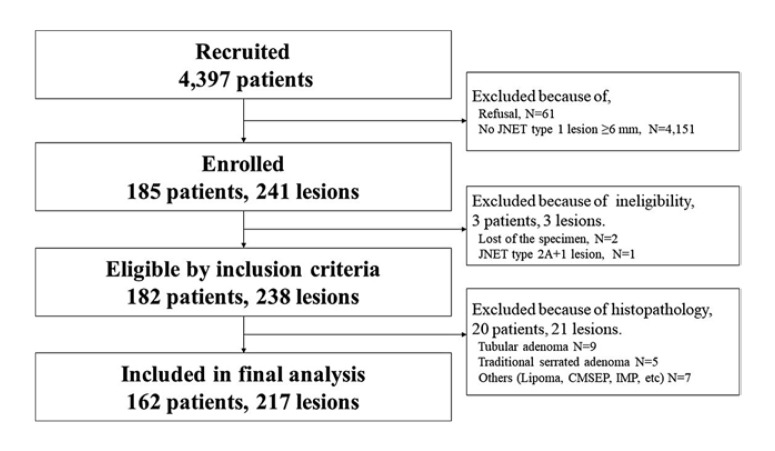

In four institutions, 4,397 and 4,336 patients were recruited and admitted, respectively, between December 2019 and October 2020. Among them, 241 lesions from 185 cases were enrolled and no cases were denied enrollment. One lesion was excluded due to ineligibility, and 23 lesions were excluded due to nonserrated histology, eventually including 217 JNET type 1 lesions from 162 cases in the final analysis. The study flowchart is shown in Figure 2.

Fig. 2.

Flowchart. In four institutions, a total of 241 lesions from 185 cases were enrolled between December 2019 and October 2020, and no cases were denied enrollment. One lesion was excluded due to ineligibility, and 23 lesions were excluded due to nonserrated histology, eventually including 217 JNET type 1 lesions from 162 cases in the final analysis.

As shown in Table 1, the patients' mean age was 65.7 ± 10.3 years, and the male/female ratio was 89/73. A total of 146 lesions (67.3%) were in the right colon. The mean diameter of JNET type 1 lesions was 9.5 ± 5.0 mm, and 148 lesions (68.2%) were between 6 and 9 mm. Pathologically, 129 lesions were diagnosed as SSLs and 88 lesions as HPs. The percentage of pathological SSLs was 49.3% in 6–9 mm JNET type 1 lesions and 81.1% in >10 mm JNET type 1 lesions. Between SSLs and HPs, there were no significant differences in age; however, there were significant differences in sex ratio, location, and size.

Table 1.

Baseline characteristics

| Overall | SSL | HP | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Patients | 162 | 103 | 72 | |

| Age, years | 65.7±10.3 | 65.4±10.9 | 66.1±9.6 | 0.571 |

| Sex ratio (male/female) | 89/73 | 44/59 | 49/23 | <0.01 |

| Lesions | 217 | 129 | 88 | |

| Right colon, % | 67.3 | 80.6 | 47.7 | <0.01 |

| Mean size, mm | 9.5±5.0 | 10.8±5.9 | 7.6±2.8 | <0.01 |

| Size: 6–9 mm | 148 | 73 | 75 | <0.01 |

| Size: >10 mm | 69 | 56 | 13 | <0.01 |

HP, hyperplastic polyp; SSL, sessile serrated lesion.

Comparison of SSL and HP.

Study Outcomes

Diagnostic Performance in Discriminating SSLs from HPs

Endoscopically, 139 lesions were diagnosed as SSLs and 78 lesions as HPs, and histopathologically, 129 lesions were diagnosed as SSLs and 88 lesions as HPs, as shown in Table 2. Table 3 shows that the diagnostic performance for SSLs in JNET type 1 lesions ≥6 mm was as follows: sensitivity 79.8% (95% CI 74.7–84.4), specificity 59.1% (49.8–62.4), accuracy 71.4% (65.3–76.9), positive predictive value 74.1% (69.3–78.4), and negative predictive value 66.7% (58.1–74.3). The sensitivity of each institution was 75.0%, 79.2%, 80.0%, and 80.4%, respectively, with no significant variations among the institutions.

Table 2.

Differential diagnosis of SSLs and HPs in JNET type 1 lesions

| Endoscopic diagnosis | Pathological diagnosis |

|

|---|---|---|

| SSL | HP | |

| SSL | 103 (61) | 36 (14) |

| HP | 26 (13) | 52 (26) |

SSL, sessile serrated lesion; HP, hyperplastic polyp. High confidence cases are given in parentheses.

Table 3.

Diagnostic performance of expert endoscopists in discriminating SSLs from HPs

| Overall (N = 217) | High confidence (N = 114) | |

|---|---|---|

| Sensitivity | 79.8% (74.7–84.4) | 82.4% (76.1–87.7) |

| Specificity | 59.1% (49.8–62.4) | 65.0% (53.3–74.7) |

| Accuracy | 71.4% (65.3–76.9) | 76.3% (68.1–83.1) |

| PPV | 74.1% (69.3–78.4) | 81.3% (75.1–86.5) |

| NPV | 66.7% (58.1–74.3) | 66.7% (54.6–76.6) |

PPV, positive predict value; NPV, negative predict value. 95% confidence interval is given in parentheses.

Diagnostic Performance and Confidence Levels

A total of 114 lesions (52.5%) were endoscopically diagnosed with high confidence and 103 lesions (47.5%) were diagnosed with low confidence. In the high-confidence group, 75 lesions were diagnosed as SSLs and 39 as HPs endoscopically, whereas 74 lesions were diagnosed as SSLs and 40 lesions as HPs histopathologically. The diagnostic performance of the high-confidence group was 82.4% (76.1–87.7) for sensitivity, 65.0% (53.3–74.7) for specificity, and 76.3% (68.1–83.1) for accuracy. The upper limit of the 95% CI for sensitivity was 87.7%.

Appearance Ratio of the Eight Endoscopic Findings

As shown in Table 4, the mean number of the eight endoscopic findings recognized in the SSL and HP groups was 2.76 and 1.52, respectively. The appearance rates of the eight findings in the SSL versus HP groups were: irregular shape 41.9% versus 23.9%, indistinct border 38.0% versus 20.5%, cloud-like surface 20.9% versus 8.0%, mucus cap 62.0% versus 33.0%, rim of debris 16.3% versus 9.1%, dilated vessels 51.9% versus 34.1%, dilated crypts 44.2% versus 20.5%, and inverted growth pattern 0.78% versus 3.4%. Table 5 shows the appearance ratio of the eight findings in SSLs and HPs and the p value between them. Except for inverted growth, seven of the eight endoscopic findings were more frequently observed in SSLs, and the appearance rates of six findings (irregular shape, indistinct border, cloud-like surface, mucus cap, dilated vessels, and dilated crypts) were significantly higher in SSLs.

Table 4.

Distribution of recognized endoscopic findings in SSLs and HPs

| Recognized endoscopic findings | SSL (N = 129) | HP (N = 88) |

|---|---|---|

| 0 | 6 | 18 |

| 1 | 21 | 31 |

| 2 | 36 | 20 |

| 3 | 33 | 15 |

| 4 | 13 | 2 |

| 5 | 13 | 2 |

| 6 | 3 | 0 |

| 7 | 3 | 0 |

| 8 | 1 | 0 |

| Average | 2.76 | 1.52 |

SSL, sessile serrated lesion; HP, hyperplastic polyp.

Table 5.

Appearance ratio of the eight findings in SSLs and HPs

| Endoscopic findings | SSL (N = 129) | HP (N = 88) | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Irregular shape | 41.9% | 23.9% | <0.01 |

| Indistinctive border | 38.0% | 20.5% | <0.01 |

| Cloud-like surface | 20.9% | 8.0% | <0.01 |

| Mucus cap | 62.0% | 33.0% | <0.01 |

| Rim of debris | 16.3% | 9.1% | 0.13 |

| Dilated vessel | 51.9% | 34.1% | <0.01 |

| Dilated crypt | 44.2% | 20.5% | <0.01 |

| Inverted growth pattern | 0.78% | 3.4% | 0.16 |

SSL, sessile serrated lesion; HP, hyperplastic polyp.

Multivariate Logistic Regression Analysis of the Eight Endoscopic Findings for SSLs

Multivariate logistic regression analysis was used to evaluate how useful each of the eight endoscopic findings (irregular shape, indistinct border, cloud-like surface, mucus cap, rim of debris, dilated vessels, dilated crypts, inverted growth pattern) were in the differential diagnosis, with each finding as an independent factor. As shown in Table 6, the odds ratios for the eight endoscopic findings were 1.884, 1.811, 2.543, 2.262, 1.760, 1.997, 1.819, and 0.085, respectively. Only two findings, mucus cap and dilated vessel, were statistically significant. The area under the receiver operating characteristic curve using the eight findings was 0.727, and that of only the mucus cap and dilated vessel was 0.664.

Table 6.

Multivariate logistic regression analysis of eight endoscopic findings for SSLs

| Endoscopic findings | OR | 95% CI | p value |

|---|---|---|---|

| Irregular shape | 1.884 | 0.959–3.698 | 0.066 |

| Indistinctive border | 1.811 | 0.895–3.667 | 0.099 |

| Cloud-like surface | 2.543 | 0.964–6.707 | 0.059 |

| Mucus cap | 2.262 | 1.212–4.223 | <0.05 |

| Rim of debris | 1.760 | 0.652–4.750 | 0.265 |

| Dilated vessel | 1.997 | 1.062–3.756 | <0.05 |

| Dilated crypt | 1.819 | 0.906–3.652 | 0.092 |

| Inverted growth pattern | 0.085 | 0.003–2.534 | 0.155 |

OR, odds ratio; CI, confidence interval.

Discussion/Conclusion

This is the first multicenter prospective study to clarify the differential diagnostic performance of magnifying colonoscopy in distinguishing SSLs from HPs in clinical practice. In the present study, the sensitivity of the endoscopic diagnosis of SSLs in JNET type 1 lesions ≥6 mm was 79.8% (95% CI, 74.7–84.4). The upper limit of the 95% CI for sensitivity was less than 90%. This result statistically showed that the probability of sensitivity exceeding 90% is less than 2.5%. The differential diagnosis of SSLs in JNET type 1 lesions ≥6 mm was suggested to be challenging even by expert endoscopists. If selective endoscopic resection is performed based on endoscopic diagnosis, 20.2% of SSLs are potentially misdiagnosed as HPs and left on site. The diagnostic performance using magnifying colonoscopy is considered inadequate for selective endoscopic resection of SSLs.

There are two hypotheses as to why the SSL differentiation was not sufficiently sensitive. First, histopathological features of SSLs are difficult to observe endoscopically. Unlike adenomatous lesions, the histopathological feature of SSLs is “distorted crypt” that refers to horizontal growth along the muscularis mucosae, dilatation of the crypt base, serrations extending into the crypt base, and asymmetrical proliferation [27]. Since all these histopathological features are expressed in the crypt base, distorted crypts are difficult to detect by colonoscopy, which primarily observes surface structures. This hypothesis is supported by Table 4 showing that 48.8% of the SSLs had only two or fewer findings and six SSLs had no findings. Furthermore, the 5th edition of the WHO Classification of Tumors of the Digestive System allows for the diagnosis of SSL even if there is one obvious distorted crypt. In practice, it would be challenging to confirm by colonoscopy that there is not a single distorted crypt within the lesion. Close examination of the pathology specimens in this study revealed 11 lesions (8.5%) with only a small number of distorted crypts. Of these 11 lesions, only six could be diagnosed as SSL even by magnifying colonoscopy.

The eight characteristic endoscopic findings of SSAPs were not specific to SSLs and they were often observed in SSLs and HPs. Table 4 shows that while an average of 2.76 endoscopic findings were noted in SSLs, an average of 1.52 findings were also recognized in HPs, and 79.5% of HPs showed at least one of the eight findings. Although six of the eight findings were statistically more frequent in SSLs, these results only showed the difference in frequency and did not indicate that a differential diagnosis was possible.

Second, the study was conducted as a prospective study in clinical practice. Unlike studies using static images, the endoscopist must manage the patient, operate the colonoscope, observe the lesion in detail, and make a diagnosis and treatment plan in a short period of time. Inadequate bowel preparation or excessive intestinal peristalsis makes detailed observation difficult. Therefore, the accuracy of the differential diagnosis in actual clinical practice is lower than that in the previously reported idealistic static images that were used.

This study also investigated the efficacy of concomitant use of confidence levels in the differential diagnosis of SSLs as a secondary analysis. As shown in Table 3, the sensitivity in the HC group was 82.4% and the upper limit of the 95% CI for sensitivity was 87.7%, indicating that sensitivity was unlikely to exceed 90%, even in the HC group. The multivariate logistic regression analysis of the usefulness of the eight endoscopic findings showed that mucus cap and dilated vessel were statistically significant findings. If mucus cap and dilated vessel are recognized with high confidence, the likelihood of SSLs may be high. Furthermore, if SSL had been diagnosed when any of the eight characteristic endoscopic findings were positive, the sensitivity would have been 123/129 (95%), which is sufficiently high. However, with a specificity of 20.5% and a negative predictive value of 75.0%, one in four lesions diagnosed during colonoscopy as HPs will be histopathologically diagnosed as SSL. It may be difficult to use this criterion as a differential diagnosis in clinical practice. Unfortunately, these are based on the results of secondary analysis. Additional validation studies would be necessary.

The use of artificial intelligence (AI) to assist in the endoscopic diagnosis of SSLs is also being investigated [28, 29, 30]. A recent analysis of the diagnostic performance of AI reported sensitivity and specificity for SSLs of 80.9% and 62.1%, respectively [31]. Although these levels are similar to the results of this study and appear to be lower than expected, similar systems to date have sometimes excluded SSLs or failed to distinguish between SSLs and HPs [32, 33]. Currently, even with AI, accurate differential diagnosis between SSLs and HPs is expected to be difficult.

The present study had some limitations. First, when performing selective resection of SSLs, it is necessary to consider the diagnostic potential of including lesions other than serrated lesions, such as adenomas; however, lesions other than serrated lesions were excluded in this study. When excluded lesions are included, the diagnostic performance for SSLs in JNET type 1 lesions ≥6 mm was as follows: sensitivity, 79.8% (95% CI 74.7–84.4); specificity, 53.2% (46.8–59.0); accuracy, 67.6% (61.7–72.9); positive predictive value, 66.9% (62.3–71.0); and negative predictive value, 69.0% (60.7–76.5). The addition of the 21 excluded lesions does not affect the sensitivity of SSLs. In addition, this study excluded patients with serrated polyposis. Second, since the diagnosis of SSLs was defined based on an overall evaluation that included white light imaging, NBI, and magnified NBI, it was not possible to assess the extent to which these modalities affected the diagnosis. Lastly, the criteria for endoscopic findings were all subjective and vague. For example, it is not specified what degree of irregularity should be considered as “irregular” or “indistinct border.” Thus, at present, there are no clear criteria for each finding. This point has been pointed out in earlier studies as a possible cause of inconsistency in judgments by the same observer or other observers [19]. Since this study was intended for the actual clinical setting, no ex post analysis of these discrepancies was conducted.

In conclusion, the results of this study showed that the sensitivity of the differential diagnosis of SSLs was very unlikely to exceed 90% of the threshold value. Therefore, accurate differential diagnosis of SSLs and HPs using magnifying colonoscopy was challenging even for experts. JNET type 1 lesions ≥6 mm are recommended to be resected because selective endoscopic resection has a disadvantage of leaving approximately 20% of SSLs on site. Future advances are expected in the endoscopic differential diagnosis between SSLs and HPs.

Statement of Ethics

This study was conducted in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki and the Clinical Research Act. This study protocol was reviewed and approved by the Research Ethics Review Committee in Sano Hospital on December 5th, 2019, approval number 201912-02; it was also preregistered in UMIN-CTR (University Hospital Medical Information Network Clinical Research Registration System) as UMIN ID: 000037543. Written informed consent was obtained from all participants.

Conflict of Interest Statement

The authors have no conflicts of interest to declare.

Funding Sources

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

Author Contributions

Daizen Hirata, Akira Teramoto, Mineo Iwatate, Wataru Sano, Hiroshi Kashida, Yasushi Sano, and Yoshitaka Murakami designed the study; Daizen Hirata, Akira Teramoto, Mineo Iwatate, Santa Hattori, Mikio Fujita, Tsuguhiro Matsumoto, Chikara Ebisutani, Wataru Sano, Yoriaki Komeda, Hiroshi Kashida, Yasushi Sano, and Masatoshi Kudo recruited participants and data collection; Daizen Hirata, Mineo Iwatate, and Wataru Sano interpreted the data and performed statistical analysis; Daizen Hirata drafted the manuscript; Mineo Iwatate, Wataru Sano, Hiroshi Kashida, Yasushi Sano, Yoshitaka Murakami, and Masatoshi Kudo critically revised the manuscript for intellectual content; all authors approved the final version of the manuscript.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.

Acknowledgments

We would like to thank Honyaku Center Inc. for English language editing, Drs. Fumihiro Inoue, Hajime Honjo, Tomoyuki Nagai, Tomohiro Soda, Saori Kashiwagi, and Yoshio Sakamoto for their dedicated cooperation and high-quality colonoscopies.

Funding Statement

This research received no specific grant from any funding agency in the public, commercial, or not-for-profit sectors.

References

- 1.Sung H, Ferlay J, Siegel RL, Laversanne M, Soerjomataram I, Jemal A, et al. Global cancer statistics 2020: GLOBOCAN estimates of incidence and mortality worldwide for 36 cancers in 185 countries. CA Cancer J Clin. 2021 May;71((3)):209–249. doi: 10.3322/caac.21660. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Leggett B, Whitehall V. Role of the serrated pathway in colorectal cancer pathogenesis. Gastroenterology. 2010 Jun;138((6)):2088–2100. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2009.12.066. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.IJspeert JEG, Vermeulen L, Meijer GA, Dekker E. Serrated neoplasia: role in colorectal carcinogenesis and clinical implications. Nat Rev Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Jul;12((7)):401–409. doi: 10.1038/nrgastro.2015.73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Ferlitsch M, Moss A, Hassan C, Bhandari P, Dumonceau JM, Paspatis G, et al. Colorectal polypectomy and endoscopic mucosal resection (EMR): European society of gastrointestinal endoscopy (ESGE) clinical guideline. Endoscopy. 2017 Mar;49((3)):270–297. doi: 10.1055/s-0043-102569. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Sano W, Sano Y, Iwatate M, Hasuike N, Hattori S, Kosaka H, et al. Prospective evaluation of the proportion of sessile serrated adenoma/polyps in endoscopically diagnosed colorectal polyps with hyperplastic features. Endosc Int Open. 2015 Aug;3((4)):E354–8. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1391948. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Sano W, Fujimori T, Ichikawa K, Sunakawa H, Utsumi T, Iwatate M, et al. Clinical and endoscopic evaluations of sessile serrated adenoma/polyps with cytological dysplasia. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2018 Aug;33((8)):1454–1460. doi: 10.1111/jgh.14099. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Hasegawa S, Mitsuyama K, Kawano H, Arita K, Maeyama Y, Akagi Y, et al. Endoscopic discrimination of sessile serrated adenomas from other serrated lesions. Oncol Lett. 2011 Sep 1;2((5)):785–789. doi: 10.3892/ol.2011.341. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Kashida H, Ikehara N, Hamatani S, Kudo SE, Kudo M. Endoscopic characteristics of colorectal serrated lesions. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011 Jul-Aug;58((109)):1163–1167. doi: 10.5754/hge10093. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Yamada M, Sakamoto T, Otake Y, Nakajima T, Kuchiba A, Taniguchi H, et al. Investigating endoscopic features of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps by using narrow-band imaging with optical magnification. Gastrointest Endosc. 2015 Jul;82((1)):108–117. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2014.12.037. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Yamada A, Notohara K, Aoyama I, Miyoshi M, Miyamoto S, Fujii S, et al. Endoscopic features of sessile serrated adenoma and other serrated colorectal polyps. Hepatogastroenterology. 2011 Jan-Feb;58((105)):45–51. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ishigooka S, Nomoto M, Obinata N, Oishi Y, Sato Y, Nakatsu S. Evaluation of magnifying colonoscopy in the diagnosis of serrated polyps. World J Gastroenterol. 2012 Aug 28;18((32)):4308–4316. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v18.i32.4308. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Tadepalli US, Feihel D, Miller KM, Itzkowitz SH, Freedman JS, Kornacki S, et al. A morphologic analysis of sessile serrated polyps observed during routine colonoscopy (with video) Gastrointest Endosc. 2011 Dec;74((6)):1360–1368. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2011.08.008. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Bouwens MW, van Herwaarden YJ, Winkens B, Rondagh EJ, de Ridder R, Riedl RG, et al. Endoscopic characterization of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps with and without dysplasia. Endoscopy. 2014 Mar;46((3)):225–235. doi: 10.1055/s-0034-1364936. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Lee EJ, Kim MJ, Chun SM, Jang SJ, Kim DS, Lee DH, et al. Sessile serrated adenoma/polyps with a depressed surface: a rare form of sessile serrated adenoma/polyp. Diagn Pathol. 2015 Jun 20;10((1)):75. doi: 10.1186/s13000-015-0325-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kawasaki K, Kurahara K, Oshiro Y, Yanai S, Kobayashi H, Nakamura S, et al. Clinicopathologic features of inverted serrated lesions of the large bowel. Digestion. 2016;93((4)):280–287. doi: 10.1159/000446394. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Hazewinkel Y, López-Cerón M, East JE, Rastogi A, Pellisé M, Nakajima T, et al. Endoscopic features of sessile serrated adenomas: validation by international experts using high-resolution white-light endoscopy and narrow-band imaging. Gastrointest Endosc. 2013 Jun;77((6)):916–924. doi: 10.1016/j.gie.2012.12.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.IJspeert JEG, Bastiaansen BAJ, van Leerdam ME, Meijer GA, van Eeden S, Sanduleanu S, et al. Development and validation of the WASP classification system for optical diagnosis of adenomas, hyperplastic polyps and sessile serrated adenomas/polyps. Gut. 2016 Jun;65((6)):963–970. doi: 10.1136/gutjnl-2014-308411. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Nakao Y, Saito S, Ohya T, Aihara H, Arihiro S, Kato T, et al. Endoscopic features of colorectal serrated lesions using image-enhanced endoscopy with pathological analysis. Eur J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2013 Aug;25((8)):981–988. doi: 10.1097/MEG.0b013e3283614b2b. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Uraoka T, Higashi R, Horii J, Harada K, Hori K, Okada H, et al. Prospective evaluation of endoscopic criteria characteristic of sessile serrated adenomas/polyps. J Gastroenterol. 2015 May;50((5)):555–563. doi: 10.1007/s00535-014-0999-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Yamashina T, Takeuchi Y, Uedo N, Aoi K, Matsuura N, Nagai K, et al. Diagnostic features of sessile serrated adenoma/polyps on magnifying narrow band imaging: a prospective study of diagnostic accuracy. J Gastroenterol Hepatol. 2015 Jan;30((1)):117–123. doi: 10.1111/jgh.12688. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Kimura T, Yamamoto E, Yamano HO, Suzuki H, Kamimae S, Nojima M, et al. A novel pit pattern identifies the precursor of colorectal cancer derived from sessile serrated adenoma. Am J Gastroenterol. 2012 Mar;107((3)):460–469. doi: 10.1038/ajg.2011.457. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sano W, Hirata D, Teramoto A, Iwatate M, Hattori S, Fujita M, et al. Serrated polyps of the colon and rectum: remove or not? World J Gastroenterol. 2020 May 21;26((19)):2276–2285. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v26.i19.2276. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Sano Y, Tanaka S, Kudo SE, Saito S, Matsuda T, Wada Y, et al. Narrow-band imaging (NBI) magnifying endoscopic classification of colorectal tumors proposed by the Japan NBI Expert Team. Dig Endosc. 2016 Jul;28((5)):526–533. doi: 10.1111/den.12644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Iwatate M, Sano Y, Tanaka S, Kudo SE, Saito S, Matsuda T, et al. Validation study for development of the Japan NBI Expert Team classification of colorectal lesions. Dig Endosc. 2018 Sep;30((5)):642–651. doi: 10.1111/den.13065. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hirata D, Kashida H, Iwatate M, Tochio T, Teramoto A, Sano Y, et al. Effective use of the Japan Narrow Band Imaging Expert Team classification based on diagnostic performance and confidence level. World J Clin Cases. 2019 Sep 26;7((18)):2658–2665. doi: 10.12998/wjcc.v7.i18.2658. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Kashida H. Endoscopic diagnosis of sessile serrated polyp: a systematic review. Dig Endosc. 2019 Jan;31((1)):16–23. doi: 10.1111/den.13263. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Pai RK, Mäkinen MJ, Rosty C, Colorectal serrated lesions and polyps . WHO classification of tumours of the digestive system. In: Nagtegaal ID, Arends MJ, Odze RD, Lam AK, editors. Lyon, France: IARC Press; 2019. pp. p. 163–169. [Google Scholar]

- 28.Mori Y, Kudo SE, Ogawa Y, Misawa M, Takeda K, Kudo T, et al. Mo1991 can artificial intelligence correctly diagnose sessile serrated adenomas/polyps? Gastrointest Endosc. 2017;85((5)):AB510. [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu X, Nemoto D, Wang Y, Guo Z, Shen Y, Aizawa M, et al. Sa1923 detection and diagnosis of sessile serrated adenoma/polyps using convolutional neural network (artificial intelligence) Gastrointest Endosc. 2018;87((6)):AB251. [Google Scholar]

- 30.Lafeuille P, Lambin T, Yzet C, Latif EH, Ordoqui N, Rivory J, et al. Flat colorectal sessile serrated polyp: an example of what artificial intelligence does not easily detect. Endoscopy. 2022 May;54((5)):520–521. doi: 10.1055/a-1486-6220. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Minegishi Y, Kudo SE, Miyata Y, Nemoto T, Mori K, Misawa M, et al. Comprehensive diagnostic performance of real-time characterization of colorectal lesions using an artificial intelligence-assisted system: a prospective study. Gastroenterology. 2022 Jul;163((1)):323–5.e3. doi: 10.1053/j.gastro.2022.03.053. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mori Y, Kudo SE, Misawa M, Saito Y, Ikematsu H, Hotta K, et al. Real-time use of artificial intelligence in identification of diminutive polyps during colonoscopy: a prospective study. Ann Intern Med. 2018 Sep 18;169((6)):357–366. doi: 10.7326/M18-0249. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Zachariah R, Samarasena J, Luba D, Duh E, Dao T, Requa J, et al. Prediction of polyp pathology using convolutional neural networks achieves “resect and discard” thresholds. Am J Gastroenterol. 2020 Jan;115((1)):138–144. doi: 10.14309/ajg.0000000000000429. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

All data generated or analyzed during this study are included in this article. Further inquiries can be directed to the corresponding author.