Abstract

We investigated the extent to which parents’ prosocial talk and negations relate to the quantity and diversity of parents’ spatial language production. We also examined similar associations among children. Participants included 51 four- to seven-year-old children and their parents recruited from South Florida. Most of the dyads included mothers and were Hispanic and bilingual. Dyads constructed a Lego house for 10 minutes. Sessions were transcribed and coded for instances of parent prosocial talk (praises, reflective statements, and behavior descriptions), child general positive statements (all positive contributions to the interaction), and parent and child negations (criticisms, corrections, and disapprovals) using the Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System. Transcripts were also coded for quantity and diversity of spatial language including shape terms (e.g., square), dimensional adjectives (e.g., little), orientations (e.g., turn), locations (e.g., middle), spatial features/properties (e.g., edge). Parents’ prosocial language, but not negations, were significantly associated with the quantity and diversity of parents’ spatial language. Children’s general positive statements were significantly associated with children’s spatial language quantity. Exploratory data analyses also revealed significant associations between parent-child talk about shapes, dimensions, and spatial features and properties. Findings suggest that variability in parent-child prosocial and spatial talk during collaborative spatial play relates to aspects of their own – and each other’s – spatial language production.

Keywords: spatial language, prosocial behavior, language quality and quantity

Spatial thinking, or the ability to understand and mentally transform 2-D and 3-D information (Levine et al., 1999; Uttal et al., 2013) is foundational for managing ordinary tasks such as assembling a child’s toy and accomplishing extraordinary tasks such as visualizing yet-to-be-discovered chemical compounds. Given that spatial thinking has generally been linked to entry and success in Science, Technology, Engineering and Mathematics (STEM; Eilam & Alon, 2019; Lauer & Lourenco, 2016; Verdine et al., 2014; Wai et al., 2009), and can be improved through intervention (Casasola et al., 2020; Eilam & Alon, 2019; Hawes et al., 2017), it is important to understand what factors and processes promote children’s development of these skills. One candidate factor is spatial language, or the lexicon of words used to describe the shapes, sizes, locations, and features of objects, people, and spaces. There is robust evidence that broadly links variability in spatial language that children hear and produce with their spatial abilities using cross-sectional (Miller et al., 2017; Polinsky et al., 2017), longitudinal (Pruden et al., 2011), and experimental (Casasola et al., 2020) designs. Although these prior studies have assessed spatial language quality through an examination of the lexical diversity, or the number of different spatial words spoken (calculated as spatial types), domain-general language research (Beals & Tabors, 1993; Distefano et al., 2018); Fisher et al., 2013; Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2015; Romeo et al., 2018; Rowe, 2012; Weizman & Snow, 2001) shows that an examination of additional measures of spatial language quality are necessary to paint a more complete picture of the role that spatial language might play in children’s spatial thinking. The present study addresses this gap by investigating the extent to which the quality of the parent-child interaction is associated with spatial language production. Specifically, we look at whether two components of parent-child social behavior, prosocial talk (e.g., praises, reflective statements, and behavior descriptions) and negations (e.g., criticisms, disapprovals, or highlighting incorrect choices the other person has made) relate to parents’ and children’s spatial language production. Our interest in these two factors is rooted in theoretical and empirical research that suggests parents operate in profiles of parenting behaviors such that parents who make more investments in one process of the child’s life are more likely to also do so in another process (Bradley & Corwyn, 2004; Clements et al., 2021). For instance, parents produce different amounts of praise (one component of prosocial talk) and spatial language with their children during different tasks (Ren et al., 2022), yet parents who invest more in their children’s socioemotional support in the form of prosocial parenting behaviors have also been shown to invest more in their children’s cognitive stimulation in the form of richer language input (Heymann et al., 2020) and a higher quantity of number language input (Clements et al., 2021).

More specifically, research in the areas of number talk and literacy has found a unique role for aspects of parents’ positive verbal behaviors (e.g., prosocial talk and autonomy supportive language) on language, literacy, and math outcomes. For example, parents who used more autonomy supportive language also produced more number talk during collaborative play with their children (Clements et al., 2021). Garcia et al. (2019) demonstrated that infants whose parents produced more praises, reflective statements, and behavior descriptions following an intervention showed larger increases in language production, and Dodici et al. (2003) found that the quality of parent-infant interactions (as measured by the Parent Infant/Toddler Interaction Coding System; Dodici & Draper, 2001) was strongly related to early literacy skills. We predict that parents’ prosocial talk may cluster with the quantity and diversity of parents’ advanced language production (i.e., spatial language). We also predict that parents’ prosocial talk may elicit a higher quantity and diversity of advanced language (i.e., spatial language) from children. This hypothesis is rooted in sociocultural theory whereby children’s cognitive and language ability, including advanced or academic language use, is socially mediated (Vygotsky, 1978). Given the links found in related domains such as math and literacy, we sought to explore whether similar relations between parent prosocial language and parent and child language outcomes exist in the spatial language domain.

Should we find that parents’ prosocial language use is related to their own and their children’s spatial talk, this would add to the literature on factors that influence individual differences in parent and child spatial language output. Such findings would also advance developmental theory by examining parent-to-child intergenerational associations of prosocial talk and spatial language. Grounded in a Relational Developmental Systems framework, we maintain that spatial development emerges from complex co-acting systems at the biological, psychological, and cultural levels across time (Odean & Pruden, 2016; Overton & Lerner, 2014; Pruden et al., 2020). Results from this study would provide support for how one system, the spatial-relational language system, develops. Specifically, the current work advances what we know about the role of the cultural level on the development of spatial talk by examining a potential role for parent prosocial language.

Finally, the present study is one of only a few that investigates the development of children’s spatial language within a majority Hispanic and Spanish-English bilingual sample (e.g., Odean et al., 2021). The U.S. Hispanic population is the country’s second largest racial or ethnic group at over 60 million (U.S. Census Bureau, 2020), most of whom are bilingual (Pew Research Center, 2017). This study includes a more representative sample, which may result in more generalizable findings. Should parent prosocial language significantly relate to child positive statements and spatial language in this linguistically diverse sample, this would corroborate what we already know about intergenerational influences of spatial language production in monolingual English-speaking samples (Pruden et al., 2011).

Quality of language production

Although the quantity of words produced is an important component of children’s language development (Hart & Risley, 1995), investigating language quality has been crucial to better understand the extent to which parents’ language production relates with children’s later literacy skills (Beals & Tabors, 1993; Hirsh-Pasek et al., 2015; Rowe, 2012; Weizman & Snow, 2001), math abilities (Fisher et al., 2013; Levine et al., 2010), executive functioning (EF; Distefano et al., 2018), and neural language processing (Romeo et al., 2018). For instance, Romeo et al., (2018) recorded home language interactions between parents and their 4- to 6-year-old children. Children also completed a functional MRI (Magnetic Resonance Imaging) task to measure brain activation while they listened to stories. Children who had experienced more conversational turns with adults at home had greater activation in the area formally known as Broca’s area while listening to the stories. Critically, it was conversational turns, a measure of language quality, and not the quantity of adult word tokens, that significantly explained the relation between children’s language exposure and verbal skill.

Likewise, Rowe (2012) conducted a longitudinal study examining the extent to which quantity and quality of parent language input to their children when they were 18, 30, and 42 months (about 3 and a half years) related to children’s vocabulary. After also controlling for socioeconomic status (SES), quantity of parent language input, and children’s previous vocabulary skill in the regression model, Rowe (2012) found that parent language quality, in this case parents’ production of sophisticated vocabulary and decontextualized language, significantly explained additional variation in predicting children’s later vocabulary ability. Rowe (2012) asserted:

While quantity is certainly part of the story, the results presented here show that there is much to gain from looking at quality, both in terms of predicting children’s language development and in terms of understanding the mechanisms through which input might affect language. (p. 1773)

In the spatial language domain, there is evidence that the diversity and quantity of spatial language that children hear and produce relates to, and even predicts their individual differences in mental translation and rotation skills (Casasola et al., 2020; Miller et al., 2017; Polinsky et al., 2017; Pruden et al., 2011). In a longitudinal study, caregivers who produced a higher quantity of spatial language over time had children who also produced a higher quantity of spatial language (Pruden et al., 2011). Importantly, the authors noted that they used spatial quantity for analyses though spatial diversity resulted in the same overall pattern of findings. In an investigation of parent-child spatial language use at a children’s museum exhibit, Polinsky et al. (2017) demonstrated that the diversity of children’s spatial language production predicted their success when completing a puzzle that required rotation.

Casasola et al. (2020) utilized an experimental design to better understand the extent to which the diversity and quantity of spatial language that children hear impact the development of their MR skills. Indeed, children who heard richer spatial language (increased diversity and quantity) had statistically significant gains in MR when compared to the children in the control group. Taken together, these studies suggest that hearing and producing a higher quantity and richer diversity of spatial language assists in the development of children’s MR skills (Casasola et al., 2020; Polinsky et al., 2017; Pruden et al., 2011), yet questions remain concerning which qualities of parents’ and children’s language use during spatial tasks might also contribute to these associations.

We espouse Rowe’s (2012) view that both the quantity and quality of parents’ language input contributes to children’s language development. Despite evidence that parent social behavior relates to child domain-general language outcomes (e.g., Heymann et al., 2020; Madigan et al., 2019), studies have yet to look at the extent to which social behaviors during collaborative spatial play may relate to production of spatial language in parent-child dyads. It is plausible that parents who use more prosocial talk during spatial play might contribute to social contexts that are more inviting of spatial concept exploration and spatial language use compared with those who use less prosocial talk or more negations. In the present study, we examine the extent to which parents’ production of prosocial talk and negations during a structured block building task relates to the quantity and diversity of their spatial language production. We also examine similar associations in children.

Parent social behavior and language production

As recent research has shown, parents’ social behaviors, including parenting practices and language production, also play a role in children’s domain-general language development (Garcia et al., 2015; 2019; Heymann et al., 2020; Madigan et al., 2019). In a meta-analysis of 37 studies, a significant association between aspects of parent prosocial behaviors and children’s language abilities was found in children ranging from 12 to 71 months old (Madigan et al., 2019). Parenting intervention research shows parents’ praises, reflective statements, and behavior descriptions are positive parent verbal behaviors (Bagner, Garcia et al., 2016; Garcia et al., 2015; 2019; Heymann et al., 2020). For instance, Parent-Child Interaction Therapy (PCIT; Zisser & Eyberg, 2010) is a parent-training intervention aimed at enhancing the parent-child relationship to improve child externalizing behavior problems. In PCIT, trained therapists teach parents to use verbal behaviors such as praises (utterances expressing a favorable judgment of an “attribute, product, or behavior of the child”), reflective statements (declarative utterances that have the same meaning as the child’s verbalization), and behavior descriptions (non-evaluative, declarative utterances that describe the child’s ongoing or immediately completed behavior), and to avoid negations that criticize or point out children’s mistakes (Zisser & Eyberg, 2010). Our choice for conceptualization and coding of dyadic prosocial talk and negations was adapted from the Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System (DPICS-IV; Eyberg et al., 2013), a widely used behavioral coding system in clinical psychology. The three components that comprise parents’ “prosocial talk” are believed to enhance parent-child interactions by providing positive attention and support to the child. For instance, parents’ praises have been shown to relate to children’s self-esteem (Eyberg, 1988; 2013) and later motivation and academic achievement (e.g., Gunderson et al., 2013, 2018). Likewise, behavior descriptions demonstrate adult attention, interest, and approval, while modeling speech and vocabulary (Eyberg, 1988; 2013; Herschell et al., 2002); and reflective statements demonstrate that the parent is listening to the child, assist children with expressing their thoughts, and teach language by reinforcing children’s use of vocabulary, grammar, and pronunciation (Eyberg, 1988; 2013; Herschell et al., 2002).

Alternatively, negations are descriptions that correct the child’s behavior by pointing out what the child has done wrong (even if delivered in honeyed or playful tones; Eyberg et al., 2013). In other words, negations provide attention that is critical or highlights a child’s mistakes. Importantly, statements that simply provide correct information without directly negating the child or the child’s words or choices were not coded as negations. For instance, if a child incorrectly places a block while building a Lego house with a parent, the phrases “that block does not go on top of the house” and “that block goes on the side of the house” can both provide corrective feedback to a child. The difference, however, is that the former phrase points out what the child has done incorrectly while the latter phrase offers correction without pointing out that the child has made a mistake or an incorrect choice.

Studies have found a mediating effect of parents’ use of (i.e., prosocial talk) on their children’s domain-general language production for dyads who received PCIT (Garcia et al., 2015) and an adaptation of PCIT for infants – the Infant Behavior Program (IBP; Bagner, Garcia et al., 2016; Garcia et al., 2019). Moreover, one study found direct effects of IBP on the richness and complexity of maternal language (e.g., more conjunctions, adjective phrases, noun phrases and prepositional phrases), which in turn, indirectly led to improvements in their 12- to 15-month-old infants’ language development (Heymann et al., 2020). Taken together, this evidence suggests that: a.) parent social behavior is a key component in parent-child domain-general language production, and b.) the DPICS-IV is an effective system for coding parent and child social behavior.

A recently published study examining number talk suggests that this may also be the case for domain-specific language. Clements et al. (2021) examined the associations between parent management language (i.e., the use of controlling vs. autonomy granting language) and production of number talk. Forty-nine parents and their preschool-age (2 to 4.83 years) children played with Duplo blocks and a toy kitchen set for five minutes each. Transcripts were coded for six types of parent management language (e.g., explicit and qualified directives, ambiguous suggestions, choice questions; Bindman et al., 2013) that were aggregated into two composites: directive (i.e., controlling) language and autonomy supportive language. Transcripts were also coded for instances of parent number talk (e.g., counting, cardinal values, quantity comparisons, number identification, and arithmetic; Ramani et al., 2015). Parent number talk was significantly related to parent management language, such that parents who used more controlling language produced less number talk and those who used more autonomy supportive language produced more number talk (Clements et al., 2021). Given the associations of a) a critical family environment to controlling parent behavior (Segrin et al., 2015), and b) spatial language and spatial ability to math language and math ability (Dearing et al., 2012; Eilam & Alon, 2019; Purpura et al., 2017), we suspect there are similar links between the use of prosocial talk and negations and the production of spatial language in parent-child dyads. In the present study, we use the same standardized and well-validated behavior coding system from PCIT and IBP, the Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System (DPICS-IV; Eyberg et al., 2013), to test the hypothesis that parent and child social behavior during a structured Lego-building task predicts the quantity and diversity of their spatial language production.

The present study

In the present study, we investigated the extent to which parents’ prosocial talk and negations predict the diversity and quantity of parents’ spatial language production. We also examined similar intraindividual relations among children, and the intergenerational association between parents’ and children’s prosocial talk and spatial language. One proxy for the diversity of spatial language is spatial types, or the number of unique spatial words produced. For instance, the utterance “Put the short, skinny Lego on top of the short, fat Lego.” has four spatial types because there are four unique spatial words (“short,” “skinny,” “[on] top,” and “fat”). The quantity of spatial language production, however, is often measured in tokens. The above utterance has five spatial tokens because five total spatial words, regardless of uniqueness, are produced (“short” was produced twice). We investigated spatial language production and social behavior while dyads engaged in collaborative Lego-building as there is evidence to suggest that playing with Legos, a spatial toy/activity, provides opportunity for the production spatial language (Abad et al., 2018; Ferrara et al., 2011). In this study, we asked parent-child dyads to use pictographic instructions to collaboratively build a Lego house for 10 minutes as this task would likely yield a variety of spatial language and social behaviors. We coded the interactions for instances of observed parent prosocial talk, child general positive statements and parent-child negations and recorded both the diversity (types) and the total quantity (tokens) of spatial words produced. We hypothesized that parents who produced more prosocial talk during block play would also produce a richer diversity (types) and larger quantity (tokens) of spatial language. Conversely, we hypothesized that parents who produced more negations with their children during block play would produce a lesser diversity and quantity of spatial language. Finally, we explored the extent to which parents’ social behavior and spatial language were associated with the diversity and quantity of children’s spatial language production. Prior research has shown that children’s patterns of language production is similar to their parents (Pruden et al., 2011; Levine et al., 2010) so we expected to see associations between children’s social behaviors and spatial language that followed similar patterns of parents’.

Method

This study was approved by a university’s Institutional Review Board prior to data collection.

Participants

Participants included 51 parents and their 4- to 7-year-old children (M=5.12 years; SD=.43; 25 female) recruited from South Florida. Of the parents who reported their caregiver relationship (n=50), 47 (92%) were mothers and three (6%) fathers. On average, our sample was highly educated: one parent (2%) had a high school diploma/GED, four (8%) parents completed at least one year of college, 12 (24%) parents had an associate degree, 14 (27%) had a bachelor’s degree, one parent (2%) had some graduate training, and 19 parents (37%) had a graduate degree. Household income was reported by 51 families and served as our proxy for socioeconomic status: 12 (24%) reported household income of $15,000-$34,999, two (4%) reported $35,000-$49,999, 11 (22%) reported $50,000-$74,999, 15 parents (29%) reported household incomes of $75,000-$99,000, and 11 (22%) reported incomes over $100,000. Of the parents that reported their child’s ethnicity (n=50), the majority were Spanish/Hispanic/Latino (80%). Dyads spoke English only (n=28), Spanish only (n=1), or both English and Spanish (n=22) during the collaborative spatial task.

Procedure

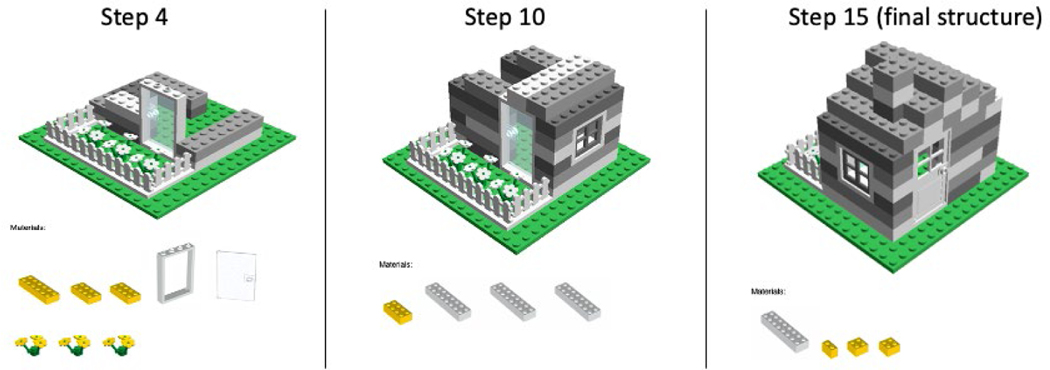

Dyads completed the study in the laboratory during one visit. After parents completed the consent form and demographic questionnaire, parent-child pairs engaged in a collaborative Lego-building task where they were given a 15-step pictographic instruction booklet and asked to build a target house (Figure 1). Dyads were given more Legos than needed to complete the task, and the Legos were multicolored which provided dyads with opportunities to talk about color should they prefer. Dyads were encouraged to build together for 10-minutes. The researchers explained to the dyads that they would be video recorded, but to play as they normally would if they were at home. The researchers then stepped out of the room, closed the door, and reentered after 10 minutes. Children received a certificate of completion and chose a small toy as compensation for their participation in the study.

Figure 1.

Steps 4, 10, and 15 from the instruction manual for the block play task.

Measures and Coding

Two research assistants (RAs) used the Child Language Data Exchange System (CHILDES; MacWhinney, 2000) to transcribe language produced by parent and child during the collaborative spatial task. CHILDES includes the CHAT program which provides a standard protocol for transcribing parent-child interactions and the CLAN program which allows researchers to analyze transcripts that are in CHAT format. For all coding, two Spanish-English bilingual RAs, unaware of the specific hypotheses of the study, were trained to at least 80% agreement using 10 randomly chosen transcripts and video-recordings, then independently coded the remaining interactions. Transcriptions were checked for accuracy during the spatial talk coding by coding transcripts while watching the original video recordings. We used different primary coders for coding. During year 1, coder A was the primary coder for spatial talk and coder B’s codes were used to check percent agreement between coders. In year 2, coder B was the primary coder for social behaviors and coder A’s codes were used to check percent agreement. Inter-rater reliability was high; the percent agreement between coders was 96% for spatial language and 94% for DPICS-IV coding. Disagreements were discussed among the coders and in cases where an agreement could not be reached, the first author reconciled the disagreement.

Spatial language production

Using CHAT format, transcripts were coded at the word level for 8 spatial language categories (Cannon et al. 2007): dimension terms (e.g., “big,” “narrow”), shape terms ( e.g., “triangle,” the word “shape”), features and properties (e.g., “round,” “corner” ), location and direction terms (e.g., “in back,” “on top”), orientation and transformation terms (e.g., “upsidedown,” “turn”), continuous amounts (e.g., “part,” “area”), deictic words (e.g., “here,” “there”), and pattern terms (e.g., “pattern,” “order”). Because we were interested in the usage of spatial terms from these categories regardless of the language spoken, two bilingual coders applied the same coding system (currently available only in English) to the English, Spanish, and Bilingual transcripts (See coding examples in Supplemental Table S1).

Although we do not address cross-linguistic differences in this study, there are two Spanish grammar rules that could have implications for the dimension category of spatial terms. Spanish dimension terms agree in both gender and number with the noun they modify. For example, an English speaker may use the dimensional term “small” while a Spanish speaker could use any one of four translations of small – “pequeño,” “pequeña,” “pequeños,” or “pequeñas” – depending on the gender and number of the referent noun(s). Moreover, bilingual dyads could use a combination of English and/or Spanish words for “small.” We decided to account for this linguistic diversity by including Spanish types and tokens as covariates in the regression models. Importantly, the significance of our findings did not change with and without Spanish types/tokens in the models. The quantity of parent and child spatial language production (spatial tokens) was measured by summing all spatial words spoken from the eight categories and the diversity of spatial language (spatial types) was calculated by summing the number of unique spatial words spoken from the eight categories. For analyses, child spatial types, child spatial tokens, parent spatial types and parent spatial tokens were used as our outcome variables. Please see the appendix (Table A1) for definitions and examples of coded spatial language).[1]

Social behaviors

Parent and child social behaviors (i.e., prosocial talk and negations) were measured using the Dyadic Parent–child Interaction Coding System-Fourth Edition (DPICS-IV; Eyberg et al., 2013). The DPICS-IV is a valid and reliable (Eyberg et al. 2013) coding system used to assess observed parent and child behaviors. Transcripts were coded at the utterance level by the same coders of spatial language (who were unaware of the hypotheses at the time of coding) whereby a meaningful thought or a 2-second pause signaled the completion of the utterance. Parents’ prosocial talk was a composite variable that consisted of praises (e.g., “Great job!”), reflective statements (e.g., child: “I’m making more.” Parent: “Okay, you’re making a lot more.”), and behavior descriptions (e.g., “I see you are stacking those.”). There were significant, strong positive correlations between all individual variables of the parent prosocial talk variable (Supplemental Table S6), a common composite variable indicative of parents’ verbal prosocial behavior with their children (Eyberg et al. 2013). Children’s general positive statements were coded differently than parents’ prosocial talk (Eyberg et al. 2013) and included all positive contributions to the dyadic interaction (e.g., “Oh that’s where it goes,” “these are pretty flowers”). Parent and child negations included corrections or verbal expressions of disapproval of the other person’s action or choices (e.g., “no, that doesn’t go there,” “wait, that’s wrong”). The DPICS uses the term ‘negative talk’ to refer to what we call ‘negations’ . We refrain from using the term ‘negative talk’ because the types of mild corrective language and criticisms that we examine in the present study do not universally have ‘negative’ connotations (e.g., Neale & Whitebread, 2019), nor is there research to suggest that they lead to negative child outcomes. Please see the appendix (Table A2) for definitions and examples of coded social behaviors).

Identical to the spatial language coding process, the bilingual coders applied the same behavioral coding system (also only available in English) to the English, Spanish, and Bilingual transcripts (Supplemental Table S1). Because so few spatial utterances contained the social behaviors of interest, all prosocial talk and negations during the 10-minute spatial task were included in analyses regardless of whether the utterances contained spatial language. For analyses, parent prosocial talk, child general positive statements, parent negations and child negations served as our independent variables (see footnote 1).

Covariates

We were interested in individual differences in child spatial language outcomes which necessitated controlling for child age. Thus, we included child age in months as a covariate. Furthermore, prior research suggests family socioeconomic status (SES) is a factor affecting spatial language development (Casasola et al., 2020), so we used household annual income as a proxy for family SES and included SES as a covariate in our models. As discussed above, we did not address cross-linguistic differences in this study, so we accounted for either Spanish types or Spanish tokens spoken by parents or children in our analyses. To account for parent and child non-spatial language production (overall talkativeness), we measured the number of non-spatial types (unique non-spatial words) and non-spatial tokens (total non-spatial words). We entered these variables as covariates in their respective regression models depending on the outcome variable. For instance, the model with parent spatial tokens as the outcome variable included parent Spanish tokens and parent non-spatial tokens as covariates and the model with child spatial types as the outcome variable included child Spanish types and child non-spatial types as covariates.

Transparency and Openness

We report how we determined our sample size, all data exclusions (if any), all manipulations, and all measures in the study, and we follow JARS (Kazak, 2018). All data, analysis code, and research materials are available by emailing the corresponding author. Data were analyzed using R, version 4.0.0 (R Core Team, 2021) and the ggplot (v3.2.1; Wickham, 2016), gvlma (v1.0.0.3; Pena & Slate, 2019), MASS (Venables & Ripley, 2002), and lm.beta (v1.5–1; Behrendt, 2014) packages. This study’s design and its analysis were not pre-registered.

Results

Power Analysis

To estimate power, we conducted a sensitivity analysis in G*Power 3.1 (Faul et al., 2009) for linear multiple regressions (F tests) with the parameters a = .05, power = .80, sample size = 51, and number of predictors = 6 (the maximum number of predictors used in any of our regressions). With these parameters, the smallest detectable effect size is f2 = .31, an effect size similar to that reported in Clements et al. (2021).

Outlier Detection and Correction

To check for outliers, Z-scores were computed for all variables of interest. Outliers were not removed; instead, their influence was down weighted using 90% Winsorization and robust statistical procedures (Leroy & Rousseeuw, 1987). Data that were Winsorized included parent prosocial talk and child general positive statements, parent and child negations, and child spatial tokens (See Supplemental Table S2 for the range, mean, and standard deviation for these data before and after Winsorization). With the inclusion of one observation where parent prosocial talk was more than 5 standard deviations (SD) above the mean, many results did not reach statistical significance, however removal of the one observation resulted in the same significance of findings as Winsorization, thus we opted to maintain as much power as possible and Winsorize outliers.

Descriptive analyses

Using R software (R Core Team, 2021), we examined descriptive statistics for parent prosocial talk and child general positive statements, negations, spatial language, and non-spatial language (Supplemental Table S3). Parent prosocial talk was a composite of behavior descriptions, praises, and reflective statements, so we also included statistics for each individual component, as well as the composite score. In terms of observed parent social behaviors, behavior descriptions (M = 1.24, SD = 1.77) and reflective statements (M = 1.25, SD = 1.78) were rarely observed. However, there was considerable variability in parents’ production of negations, (M = 9.93, SD = 7.14, Range = 1–26.5), parent praise (M = 7.88, SD = 8.01, Range = 0–48), and child general positive statements (M = 73.18, SD = 26.28, Range = 30.5–128.5), even after Winsorization.

Regarding parent and child production of spatial and non-spatial language, parents produced an average of 19.67 (SD = 6.86) spatial types (i.e., unique spatial words) and 70.80 (SD = 33.42) spatial tokens (i.e., total spatial words) during this 10-minute Lego building task. Children produced an average of 8.43 (SD = 4.51) spatial types and 70.80 (SD = 33.42) spatial tokens. However, there was a substantial amount of variability. Parents ranged from producing five to 34 spatial types and from producing only 14 to a sizeable 125 total spatial tokens during the 10-minute task. Child production of spatial language had the same pattern of results, ranging from one to 20 spatial types and from five to 52.5 spatial tokens. The results from Welch’s unequal variances t-tests revealed no significant child gender differences for children’s or parents’ production of spatial types, spatial tokens, prosocial talk or negations (Supplemental Table S4). Thus, child gender was not included in any of our further analyses.

We examined zero-order correlations for all variables (Supplemental Table S5). For these analyses, we aggregated parent behavior descriptions, praises, and reflective statements for the parent prosocial talk variable. Overall, parents’ prosocial talk was significantly positively correlated with parents’ spatial types [r(49) = .61, p <.001] and spatial tokens [r(49) = .67, p <.001] and children’s general positive statements were significantly positively correlated with children’s spatial types [r(49) = .62, p <.001] and spatial tokens [r(49) = .75, p <.001]. We did not find evidence that parents’ negations were significantly correlated with any parent variables; however, children’s negations were significantly positively correlated with children’s non-spatial types [r(49) = .42, p = .002] and non-spatial tokens [r(49) = .38, p = .006]. We also did not find any evidence of parent-child cross correlations for prosocial talk/general positive statements, negations, spatial types, or spatial tokens.

Then, we estimated a series of regressions to examine the extent to which these relations existed after controlling for a variety of covariates. We formally tested the regression models for violations of important assumptions using the gvlma() function from the gvlma package. There was some heteroscedasticity and skewness present in our data, so robust statistical models and bootstrapping were implemented to mitigate issues stemming from violations. Specifically, we fitted robust linear regressions to address outliers and violations of heteroscedasticity and skewness. Robust regressions use Iteratively Reweighted Least Squares (IRLS) for Maximum Likelihood Estimation (MLE) as opposed to Ordinary Least Squares (OLS) which is influenced by outliers and violations of assumptions (Rousseeuw, & Leroy, 2005). As such, we do not report R2 statistics as it is not an appropriate measure to assess fit of robust linear regressions (Willett & Singer, 1988). Furthermore, we used a Huber loss function, conducted a parametric bootstrap with 10,000 bootstrap replicates, and we determined the significance of the associations using bootstrapped 95% confidence intervals (CI).

The regression model that examined parent spatial types included parent non-spatial types, parent Spanish types, child age, and family SES (household income) as covariates, while the regression model that examined child spatial types included child non-spatial types, child Spanish types, child age, and family SES (household income) as covariates. This was repeated for models that examined spatial tokens. Six main analyses were conducted. First, we tested the extent to which parents’ prosocial talk and negations are associated with parents’ spatial language diversity (i.e., spatial types). Second, we tested the extent to which parents’ prosocial talk and negations are associated with parents’ spatial language quantity (i.e., spatial tokens). Third, we tested the extent to which child general positive statements and negations are associated with child production of spatial types. Then, we tested the extent to which child general positive statements and negations are associated with child production of spatial tokens. Based off the results of these analyses, we examined the relations between parents’ production of prosocial talk, spatial types, and spatial tokens and children’s production of spatial types and tokens, controlling for relevant covariates. See Supplemental Figure S1 for added variable plots depicting the relations between the predictors and outcomes of interest.

Are parents’ prosocial talk and negations associated with the diversity of their spatial language production?

A robust multiple regression model was estimated to examine the association between parents’ production of prosocial talk and negations and their diversity of spatial language production (i.e., spatial types) after controlling for parent non-spatial types, parent Spanish types, child age, and family SES (see Table 1, Model 1). There was no evidence of a relation between parent negations and parent production of spatial types, [t(44) = −1.10, p = 0.277, b = −0.09, 95% CI (−0.250, 0.070)], however, there was a significant positive association between parent prosocial talk and parent spatial types, [t(44) = 3.44, p = 0.001, b = 0.38, 95% CI (0.163, 0.596)], such that parents who produced more prosocial talk also produced more spatial types. Thus, even after controlling for a variety of relevant variables, we see that parent prosocial talk is associated with increased diversity of spatial language use in parents.

Table 1.

Results of the multiple regression models examining the associations between parent prosocial talk, parent negations, and parent spatial types/tokens, controlling for parent non-spatial types/tokens, parent Spanish types/tokens, child age, and family SES (N=51).

| b | β | t | LL to UL 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Parent Predictors of Parent Spatial Types | |||||

| Parent prosocial talk | 0.38 | 0.36 | 3.44 | 0.16 to 0.60 | 0.001** |

| Parent negations | −0.09 | −0.09 | −1.10 | −0.25 to 0.07 | 0.277 |

| Covariates | |||||

| Parent non-spatial types | 0.10 | 0.48 | 4.53 | 0.05 to 0.14 | <001*** |

| Parent Spanish types | −0.01 | −0.08 | −0.84 | −0.04 to 0.01 | 0.403 |

| Child age | −0.06 | −0.05 | −0.55 | −0.29 to 0.16 | 0.584 |

| Family SES | 0.74 | 0.16 | 1.82 | −0.06 to 1.54 | 0.076 |

| Model 2: Parent Predictors of Parent Spatial Tokens | |||||

| Parent prosocial talk | 1.36 | 0.27 | 2.79 | 0.40 to 2.31 | 0.008** |

| Parent negations | <0.001 | <0.001 | <0.001 | −0.70 to 0.70 | 1.00 |

| Covariates | |||||

| Parent non-spatial tokens | 0.09 | 0.69 | 7.05 | 0.06 to 0.11 | <001*** |

| Parent Spanish tokens | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.71 | −0.02 to 0.04 | 0.479 |

| Child age | −0.45 | −0.07 | −0.93 | −1.40 to 0.50 | 0.358 |

| Family SES | 0.11 | <0.001 | 0.07 | −3.27 to 3.50 | 0.948 |

Note:

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Are parents’ prosocial talk and negations associated with the quantity of their spatial language production?

We estimated a robust multiple regression model to examine the extent to which parents’ production of prosocial talk and negations were associated with their production of spatial tokens (spatial language quantity) after controlling for parent non-spatial tokens, parent Spanish tokens, child age, and family SES. As Table 1 (Model 2) shows, there was a significant positive association between parents’ prosocial talk and parents’ spatial tokens, [t(44) = 2.79, p = 0.008, b = 1.36, 95% CI (0.403, 2.315)], such that parents who produced more prosocial talk also produced more spatial words. Parallel to our analysis on parent negations and spatial types, we did not find evidence of a significant association between parent negations and parent spatial tokens, [t(44) <0.001, p = 1.000, b < 0.001, 95% CI (−0.698, 0.698)].

Are children’s general positive statements and negations associated with the diversity of their spatial language production?

A robust multiple regression model was estimated to examine the association between children’s production of general positive statements and negations and children’s diversity of spatial language production (i.e., spatial types), after controlling for several covariates (Table 2, Model 1). Although we initially saw a significant correlation between children’s general positive statements and children’s spatial types, after accounting for the covariates, this significant relation did not hold in the regression analysis, [t(44) = 1.30, p = 0.201, b = 0.04, 95% CI (−0.022, 0.109)]. Similar to the finding among parents’ negations and spatial types, we also found no evidence that child negations was significantly related to child production of spatial types, [t(44) = −1.50, p = 0.140, b = −0.38 95% CI (−0.868, 0.115)]. The only significant association we found was between child non-spatial types and child spatial types, a finding not entirely surprising given that children who have diverse domain-general lexicons are likely to also have more diverse domain-specific lexicons such as spatial types (Pruden et al., 2011).

Table 2.

Results of the multiple regression models examining the associations between child general positive statements, child negations, and child spatial types/tokens, controlling for child non-spatial types/tokens, child Spanish types/tokens, child age, and family SES (N=51).

| b | β | t | LL to UL 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Child Predictors of Child Spatial Types | |||||

| Child general positive statements | 0.04 | 0.25 | 1.30 | −0.02 to 0.11 | 0.201 |

| Child negations | −0.38 | −0.18 | −1.50 | −0.87 to 0.11 | 0.140 |

| Covariates | |||||

| Child non-spatial types | 0.07 | 0.50 | 2.05 | 0.00 to 0.14 | 0.046* |

| Child Spanish types | −0.01 | −0.04 | −0.32 | −0.05 to 0.03 | 0.748 |

| Child age | 0.07 | 0.08 | 0.68 | −0.14 to 0.28 | 0.500 |

| Family SES | 0.57 | 0.19 | 1.61 | −0.12 to 1.27 | 0.114 |

| Model 2: Child Predictors of Child Spatial Tokens | |||||

| Child general positive statements | 0.26 | 0.52 | 2.83 | 0.08 to 0.45 | 0.007** |

| Child negations | −0.39 | −0.06 | −0.61 | −1.64 to 0.86 | 0.546 |

| Covariates | |||||

| Child non-spatial tokens | 0.03 | 0.26 | 1.28 | −0.02 to 0.07 | 0.206 |

| Child Spanish tokens | 0.01 | 0.05 | 0.49 | −0.03 to 0.04 | 0.625 |

| Child age | 0.29 | 0.11 | 1.04 | −0.26 to 0.84 | 0.303 |

| Family SES | 2.15 | 0.23 | 2.24 | 0.27 to 4.03 | 0.030* |

Are children’s general positive statements and negations associated with the quantity of their own spatial language production?

We estimated a robust regression model to determine the extent to which children’s general positive statements and negations were associated with the quantity of children’s spatial language production (i.e., spatial tokens) after accounting for relevant covariates (see Table 2, Model 2). After controlling for child non-spatial tokens, child Spanish tokens, child age, and family SES, there was a significant, positive association between child general positive statements and child spatial tokens, t(44) = 2.83, p = .007, b = 0.26, 95% CI [0.08, 0.45], such that children who produced more general positive statements also produced more spatial tokens. We did not, however, find evidence of a significant association between child negations and child spatial tokens, t(44)= −0.61, p = 0.546, b = −0.39, 95% CI [−1.64, 0.86]. Thus, like our findings with parents, we see that children’s quantity of general positive statements is related to their production of spatial language, even after controlling for general talkativeness of the child (as estimated by our non-spatial token variable).

Are parents’ prosocial talk and spatial language diversity associated with children’s spatial language diversity?

To determine the extent to which parents’ prosocial talk and spatial language were associated with the diversity of children’s spatial language production, we estimated a robust regression model examining the associations between child spatial types, parent prosocial talk and parent spatial types shown in Table 3, Model 1. Because parent and child non-spatial types and tokens were the only consistently significant covariates in prior models, we entered parent and child non-spatial types as covariates. The only significant associations we found were between child spatial types, parent non-spatial types, and child non-spatial types. This was surprising given prior literature that has shown significant associations between parent and child production of spatial language (Polinsky et al., 2017; Pruden et al., 2011).

Table 3.

Results of the multiple regression examining the association between parent prosocial talk, parent spatial types/tokens, and child spatial types/tokens, controlling for parent and child non-spatial types/tokens (N=51).

| b | β | t | LL to UL 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Parent Predictors of Child Spatial Types | |||||

| Parent prosocial talk | −0.01 | −0.02 | −0.12 | −0.20 to 0.17 | 0.905 |

| Parent spatial types | 0.15 | 0.22 | 1.39 | −0.06 to 0.35 | 0.171 |

| Covariates | |||||

| Parent non-spatial types | −0.04 | −0.30 | −2.01 | −0.08 to <−0.00 | 0.05* |

| Child non-spatial types | 0.10 | 0.70 | 6.25 | 0.07 to 0.13 | <.001*** |

| Model 2: Parent Predictors of Child Spatial Tokens | |||||

| Parent prosocial talk | 0.09 | 0.04 | 0.29 | −0.51 to 0.69 | 0.772 |

| Parent spatial tokens | 0.02 | 0.05 | 0.23 | −0.14 to 0.18 | 0.822 |

| Covariates | |||||

| Parent non-spatial tokens | −0.01 | −0.17 | −0.88 | −0.03 to 0.01 | 0.382 |

| Child non-spatial tokens | 0.09 | 0.77 | 7.00 | 0.067 to 0.12 | <.001*** |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Are parents’ prosocial talk and spatial language quantity associated with children’s spatial language quantity?

To determine the extent to which parents’ prosocial talk and spatial language were associated with the quantity of children’s spatial language production, we estimated a robust regression model predicting child spatial tokens from parent prosocial talk and parent spatial tokens, accounting for parent and child non-spatial tokens shown in Table 3, Model 2. The only significant association we found here was between child spatial tokens and child non-spatial tokens. Again, prior literature that has shown significant associations between parent and child production of spatial language (Polinsky et al., 2017; Pruden et al., 2011), so this finding was surprising.

Exploratory Data Analyses

Given that previous studies that have shown parent spatial language use predicts child spatial language use (Polinsky et al., 2017; Pruden et al., 2011), it was unexpected that the present study found no evidence for a significant relation between parent and child spatial types or spatial tokens. Although Polinsky et al. (2017) coded the same seven categories of spatial language as the present study, Pruden et al., (2011) identified the unique ‘what’ aspects of spatial language - shapes, dimensions, and features/properties. We were interested in the extent to which children’s ‘what’ spatial language may be uniquely related to our variables of interest. Thus, we conducted an exploratory data analysis that examined the relation between parent and child “what” spatial language (Pruden et al., 2011; Pruden & Levine, 2017).

First, we estimated a robust multiple regression that assessed the relations between child ‘what’ spatial types, parents’ ‘what’ spatial types, and parents’ prosocial talk, controlling for parent and child non-spatial types. As seen in Table 4 (Model 1), there was a significant positive association between child ‘what’ spatial types and parent ‘what’ spatial types, [t(46) = 2.73, p = 0.009, b = 0.20, 95% CI (0.06, 0.35)], such that parents who used more ‘what’ spatial types had children who also used more ‘what’ spatial types. This replicated Pruden et al.’s (2011) findings that parent ‘what’ spatial talk predicted child ‘what’ spatial talk. There was also a significant positive association between child ‘what’ spatial types and parent prosocial talk, [t(46) = 2.18, p = 0.03, b = 0.09, 95% CI (0.01, 0.17)] which was interesting since we did not see evidence of a significant association between parents’ prosocial talk and all categories of children’s spatial types. See Supplemental Figure S1 for scatterplots depicting the relations between parent and child ‘what’ spatial types and tokens, controlling for parent and child non-spatial types and tokens.

Table 4.

Results of the multiple regression models examining the association between child ‘what’ spatial types/tokens, parent ‘what’ spatial types/tokens, and parent prosocial talk, controlling for parent and child non-spatial types/tokens (N=51).

| b | β | t | LL to UL 95% CI | p | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Model 1: Predictors of Child ‘What’ Spatial Types | |||||

| Parent ‘what’ spatial types | 0.20 | 0.35 | 2.73 | 0.06 to 0.35 | 0.009** |

| Parent prosocial talk | 0.09 | 0.29 | 2.18 | 0.01 to 0.17 | 0.03* |

| Covariates | |||||

| Parent non-spatial types | −0.02 | −0.31 | −2.19 | −0.03 to −0.002 | 0.03* |

| Child non-spatial types | 0.03 | 0.43 | 3.74 | 0.01 to 0.04 | 0.001** |

| Model 2: Predictors of Child ‘What’ Spatial Tokens | |||||

| Parent ‘what’ spatial tokens | 0.15 | 0.48 | 4.40 | 0.09 to 0.22 | < .001*** |

| Parent prosocial talk | 0.01 | 0.02 | 0.18 | −0.12 to 0.15 | 0.86 |

| Covariates | |||||

| Parent non-spatial tokens | −0.001 | −0.03 | −0.22 | −0.01 to 0.003 | 0.83 |

| Child non-spatial tokens | 0.02 | 0.42 | 4.74 | 0.01 to 0.02 | <.001*** |

Note.

p < .05,

p < .01,

p < .001

Then, we estimated a robust multiple regression that assessed the relations between child ‘what’ spatial tokens, parents’ ‘what’ spatial tokens, and parents’ prosocial talk, controlling for parent and child non-spatial tokens. As seen in Table 4 (Model 2), there was a significant positive association between child ‘what’ spatial tokens and parent ‘what’ spatial tokens, [t(46) = 4.40, p < 0.001, b = 0.15, 95% CI (0.09, 0.22)], such that parents who used more ‘what’ spatial tokens had children who also used more ‘what’ spatial tokens. This also replicated Pruden et al.’s (2011) findings that parents’ ‘what’ spatial talk predicted children’s ‘what’ spatial talk.

Discussion

Prior spatial language studies have looked at the diversity of spatial language as a measure of language quality (Casasola et al., 2020; Polinsky et al., 2017; Pruden et al., 2011). However, domain-general language research suggests that additional measures of spatial language quality may paint a more complete picture of the role that spatial language might play in the development of children’s spatial thinking (Fisher et al., 2013; Levine et al., 2010; Rowe et al., 2012). In the present study, we investigated the intraindividual relations between parents’ production of prosocial talk/negations and parents’ production of spatial language. We also looked at similar relations in children. Finally, we looked at the extent to which parents’ prosocial talk and spatial language relate to the quantity and diversity of children’s spatial language production. Our findings provide initial support for both the intra-individual and inter-individual links between social behaviors and aspects of spatial language production among parents’ and children.

Consistent with our hypothesis, results indicated that production of prosocial talk and general positive statements are associated with the quantity of spatial language production in parents and children respectively, even after accounting for relevant covariates such as overall language production, child age, family SES, and the amount of Spanish spoken. Many of the significant associations that were observed occurred within a person. In parents, this finding is aligned with research on the intraindividual clustering of parenting behaviors (Bradley & Corwyn, 2004; Clements et al., 2021). In children, this is in line with work that suggests children’s language ability is socially mediated and often follows similar patterns as their caregivers (Heymann et al., 2020; Levine et al., 2010; Pruden et al., 2011; Vygotsky, 1978). Two of the observed behaviors that comprised prosocial talk in this study –descriptions, and reflective statements – do not appear to occur frequently in the absence of a parent training program such as PCIT (e.g., Garcia et al., 2019). So, one possible explanation for the demonstrated relations is that prosocial talk is indicative of higher quality parenting skills/behaviors (e.g., warmth, sensitivity, praises, positive affect), and parents who have (or develop) higher quality skills produce more advanced language (Garcia et al., 2015; 2019; Heymann et al., 2020). It is also possible that child factors such as temperament may elicit certain parenting behaviors as systems theories maintain that parent-child caregiving interactions are mutually regulated (Bradley & Corwyn, 2004; Overton & Lerner, 2014). Our future work will attempt to unpack the mechanisms and processes underlying the relations between prosocial talk and spatial language by examining the effects of PCIT on parents’ production of domain-specific language such as number and spatial talk.

We also found significant associations between parents’ prosocial talk and parents’ spatial language diversity, but similar results were not found in children.

One possible explanation for the significant relation between children’s general positive statements and quantity of children’s spatial language but not the diversity, is a limited vocabulary of spatial words. While playing with blocks is likely to elicit spatial vocabulary above and beyond what is used in other types of play (Ferrera et al., 2011), our descriptive statistics revealed that children only produced an average of 8 spatial types even though they produced an average of 82 non-spatial types during the 10-minute task. Similarly, Pruden et al. (2011) found that after analyzing over 13 hours of longitudinal spatial language data from three categories (shape, dimension, and spatial feature terms), children still only produced an average of 11 spatial types although they produced an average of 765 non-spatial types. Thus, our finding that production of prosocial talk is related to the diversity of spatial language production for parents, but not for children, could be because young children have not developed a large enough lexicon from which to produce a wide variety of spatial words. Future studies could investigate the age at which child diversity of spatial language production develops into more adult-like production, and whether a focused intervention to increase children’s spatial vocabulary leads to a significant increase in the variety of spatial words produced (and the role this may play in the development of spatial abilities).

In none of our analyses did we find evidence that negations (i.e., criticisms and corrections) significantly related to the quantity or diversity of spatial language in parents or children. Recent research has demonstrated significant associations between parent controlling behavior in relation to math talk (Clements et al., 2021). So, given the association between a critical family environment and controlling parent behavior (Segrin et al., 2015), these results were surprising. Our descriptive statistics suggest that negations occurred infrequently during our 10-minute task, so it is possible that a longer language sample, or a sample from parent-child dyads who are enrolled in a parent training program would contain more negations. It is also possible that the lack of significance might be due to the relatively small sample size, or the presence of an interaction effect. Nevertheless, this is the first study to examine parent-child negations (i.e., criticisms and disapprovals) in the context of math or spatial development, so this provides an important first step into understanding the extent to which negations may play a role in spatial language production and spatial ability. Future work with a larger sample (to be able to detect possible moderating effects) is needed to build this new body of knowledge.

Although main analyses did not find evidence of significant associations between a.) parents’ spatial language from all categories and children’s spatial language from all categories, or b.) parents’ prosocial talk and children’s production of all categories of spatial types, exploratory data analyses revealed significant associations between parents’ prosocial talk and children’s production of “what” spatial types, as well as parents’ and children’s production of ‘what’ spatial types and tokens. This is consistent with Pruden et al.’s (2011) longitudinal investigation that demonstrated parents who produce talk about the shapes, dimensions, and spatial features of objects have children who do the same. Along these lines, the present study also contributes to the advancement of developmental theory. The Relational Developmental Systems framework maintains that development emerges from complex co-acting systems at the biological, psychological, and cultural level (Overton & Lerner, 2014; Pruden et al., 2020). Our study is the first to begin to look at the social-cultural contexts of spatial language production for parents and children. The finding that parent and child ‘what’ spatial language is significantly related supports the view that parent-child spatial talk is bidirectional and co-acting (Pruden et al., 2011). Further work should unpack the roles that these particular types of spatial language play in spatial development.

Limitations and Future Directions

In interpreting the findings of the current study, it is important to also consider the limitations. Our study has limited the generalizability due to our small sample size (n = 51 dyads) and the short duration of the activity observed. We also cannot determine if there is a causal impact of prosocial talk on spatial language production, or vice versa. To test this causal question, a future experiment may longitudinally observe if an increase in parent prosocial talk contributes to increased child general positive statements and spatial language. This work could be extended to observations with a wider age range of children to determine how age may moderate changes in the amount of parent prosocial language.

Future work should also examine how specific types of parent praise and other social behaviors during spatial tasks might be associated with child spatial anxiety and spatial confidence – two factors that contribute to spatial development (Gabriel et al., 2011; Lauer et al., 2018; Ramirez et al., 2012). Prior research has found that distinct types of parent praise (e.g., praise for “working hard” versus praise for “being smart”) influence children’s beliefs about whether their own abilities are fixed or malleable (Gunderson et al., 2013). The coding system we used aggregated parent labeled praise (e.g., “good job putting that window piece on”) and unlabeled praise (e.g., “great job”) as a component of prosocial talk, however, future work can help to determine the extent to which different forms of praise contribute to children’s mindset and language production.

Another limitation in our study is that we did not examine differences between English and Spanish speakers. Some research has shown that Spanish-speaking mothers use more questions and commands overall compared to mothers speaking English during play interactions (Ramos, Blizzard, Barroso, & Bagner, 2018), so it is possible that there are differences between English and Spanish speakers’ production of prosocial talk and negations. Future studies should address cross-linguistic differences in both prosocial language use and spatial language. Such studies could observe how bilingual or multi-lingual parents use prosocial talk differently depending on the language they are encouraged to use, allowing for within dyad comparisons.

The current study used a standardized and well-validated measure to code observed parent prosocial talk and negations (DPICS-IV; Bagner & Eyberg, 2007), but as we noted in the introduction, we did not look at commands and questions given the mixed nature of existing literature on these categories. Some research suggests that direct parent commands are associated with child noncompliance and defiance and are often seen as parent behaviors to avoid because the lead is taken away from the child (Bagner & Eyberg, 2007; Heflin et al., 2020; Kuczynski et al., 1987; Xu et al., 2021). Other research shows that providing commands through management language, such as using suggestions, is positively associated with children’s number talk (Clements et al., 2021). In contrast to directive language, suggestive language is positively related to executive function at 36 months of age (Bindman et al., 2013). Overall, parent’s child-directed speech positively relates to child vocabulary production across the first 54 months of life (Rowe et al., 2017). It is possible that commands and questions in the context of spatial play may play unique roles in the development of children’s spatial language and abilities. While the coding system applied in the present study is widely used, it may not provide the most representative coding of commands and questions during spatial activities. Take the parent utterance, “this shorter piece goes on top,” for instance. Although the child may interpret this as a command and put the shorter piece on top, it is not coded as a command with DPICS-IV because there is technically no request for behavior. However, if the parent said, “put this shorter piece on top,” it would be coded as a command with DPICS-IV. To fully capture the represented constructs, future studies might explore other coding systems or modifying this aspect of DPICS-IV when examining the role that questions and commands play in parent-child production of spatial language.

In summary, the present findings suggest that parents’ prosocial talk is significantly associated with the quantity of parents’ spatial language production. Similarly, there is evidence that children’s general positive statements are significantly related to children’s spatial language quantity. Findings also indicate that parents’ prosocial talk is significantly associated with parents’ spatial language diversity and children’s “what” spatial language diversity. Although we did not find evidence that the quantity and diversity of parent spatial language from all categories relate to those of children, we did find significant associations between parent and child production of ‘what’ spatial language. This suggests that aspects of parents’ social behaviors and spatial language production relate to aspects of their own – and their children’s – spatial language production. Importantly, we did not find evidence that negations (defined in this study as language that is critical or highlights incorrect choices of the child; Eyberg et al., 2013) relate to the quantity or diversity of spatial language for parents or children. Should further research demonstrate that there is truly not a significant association between negations and spatial language, this could have implications for the way parents engage children in spatial play. In this regard, such findings would suggest that it is less crucial to avoid mild corrections and negations and parents should be encouraged to use prosocial talk with their children during engagement with spatial toys and activities.

Supplementary Material

Public Significance Statement.

The present study suggests that aspects of the parent-child social context are related to parents’ and children’s production of spatial talk (e.g., talk about shapes, dimensions, and locations), language that is relevant for entry and success in Science, Technology, Engineering, and Mathematics (STEM) fields. This offers new perspectives and possible outcomes for parenting interventions that aim to improve the parent-child relationship.

Acknowledgments

Author Note: Latreese V. Hall was supported by a Florida International University Inclusion Fellowship. Daniela Alvarez-Vargas was supported by the National Institutes of General Medical Sciences of the National Institutes of Health under award number T34GM083688. Carla Abad was supported by the National Science Foundation Graduate Research Fellowship under Grant No. DGE-1038321. The content is solely the responsibility of the authors and does not necessarily represent the official views of Florida International University, the National Institutes of Health or the National Science Foundation.

Appendix

Table A1.

Spatial language coding scheme adapted from Canon et al. (2007).

| Category | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| *Dimension | Words that describe the size of two- and three-dimensional objects and spaces. | Big Narrow |

| *Shape | Words that describe the standard or universally recognized form of enclosed two- and three-dimensional objects and spaces. | Triangle Shape |

| *Feature/property | Words that describe the features and properties of two- and three-dimensional objects and spaces, as well as the properties of their features. | Side Corner |

| Location/Direction | Words that describe the relative position of objects, people, and points in space. | Top Next to |

| Orientation | Words that describe the relative orientation or transformation of objects and people in space. | Rotate Turn |

| Continuous Amount | Words that describe amount (including relative amount) of continuous quantities (including extent of an object, space, liquid, etc.). | Part Area |

| Deictic | Words that are place deictics/ pro-forms (i.e., these words rely on context to understand their referent). | Here Where |

| Pattern | Words that indicate a person may be talking about a spatial pattern. | Pattern Order |

Denotes the “what” spatial words researched by Pruden et al. (2011).

Table A2.

Social behavior coding scheme adapted from the Dyadic Parent-Child Interaction Coding System (DPICS-IV; Eyberg et al., 2013).

| Parent Categories | Definition | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Behavior Description | A non-evaluative, declarative sentence or phrase in which the subject is the other person, and the verb describes that person’s ongoing or immediately completed (< 5 sec.) observable verbal or nonverbal behavior. | You’re building a truck. You’re putting (4 sec.) the green block on. |

| Praise | A verbalization expressing a favorable judgment of an attribute, product, or behavior of the child. | You did a great job of building the tower. Nice job, honey! |

| Reflective Statement | A declarative phrase or statement that has the same meaning child verbalization. The reflection may paraphrase or elaborate upon the child’s verbalization but may not change the meaning of the child’s statement or interpret unstated ideas. | [Child: I put the window and the flower here.] Parent: You put the window and the flower beside each other. |

| Negation | A verbal expression of disapproval of the child or the child’s attributes, activities, products, or choices. This also includes sassy, sarcastic, rude, or impudent speech. | That’s not quite right, sweetie. You’re working too slowly. Uh oh, you put it on the wrong side. |

| Child Categories | Definition | Examples |

|

| ||

| Positive statement | A verbalization that contributes positively to the parent-child interaction. This includes all statements that positively evaluate an attribute, product, or behavior of the parent (specifically or generally); describe the parent’s behavior; provide neutral information; reflect the parent’s verbalizations; or acknowledge the parent. | I know you’re building a square thing. We made it look perfect. That’s where it goes. It goes on top. |

| Negation | A verbal expression of disapproval of the parent or the parent’s attributes, activities, products, or choices. This also includes sassy, sarcastic, rude, or impudent speech. | We did that wrong. It doesn’t look like the picture. No, that’s the wrong spot. |

Footnotes

Issues of directionality are beyond the scope of this correlational study, so the choice of the predictor and outcome variables are theoretically based on the premise that parents who demonstrate a larger amount of positive parenting behaviors may also use richer spatial language, yet they are methodologically arbitrary. We could have also used parent prosocial talk and child general positive statements and negations as the outcomes.

References

- Abad C, Odean R, & Pruden SM (2018). Sex differences in gains among Hispanic pre-kindergartners’ mental rotation skills. Frontiers in psychology, 9, 2563. 10.3389/fpsyg.2018.02563 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM, Coxe S, Hungerford GM, Garcia D, Barroso NE, Hernandez J, … Rosa-Olivares J. (2016). Behavioral parent training in infancy: A window of opportunity for high risk families. Journal of Abnormal Child Psychology, 44, 901–912. 10.1007/s10802-015-0089-5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM, & Eyberg SM (2007). Parent–child interaction therapy for disruptive behavior in children with mental retardation: A randomized controlled trial. Journal of Clinical Child and Adolescent Psychology, 36(3), 418–429. 10.1080/15374410701448448 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bagner DM, Garcia D, & Hill R. (2016). Direct and indirect effects of behavioral parent training on infant language production. Behavior Therapy, 47(2), 184–197. 10.1016/j.beth.2015.11.001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beals DE, & Tabors PO (1993). Arboretum, Bureaucratic, and Carbohydrates: Preschoolers’ Exposure to Rare Vocabulary at Home. Paper presented at the Biennial Meeting of the Society for Research in Child Development (New Orleans, 1993). https://files.eric.ed.gov/fulltext/ED356057.pdf

- Behrendt S. (2014). lm. beta: Add standardized regression coefficients to lm-Objects. R package version, 1–5. [Google Scholar]

- Bindman SW, Hindman AH, Bowles RP, & Morrison FJ (2013). The contributions of parental management language to executive function in preschool children. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 28(3), 529–539. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2013.03.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bradley RH, & Corwyn RF (2004). “Family process” investments that matter for child well-being. In Kalil A, & DeLeire T (Eds.), Family investments in children’s potential: Resources and parenting behaviors that promote success (pp. 1–32). Lawrence Erlbaum Associates Publishers. 10.4324/9781410610874 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Caldera YM, Culp AM, O’Brien M, Truglio RT, Alvarez M, & Huston AC (1999). Children’s play preferences, construction play with blocks, and visual-spatial skills: Are they related? International Journal of Behavioral Development, 23(4), 855–872. 10.1080/25/016502599383577 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cannon J, Levine S, & Huttenlocher J. (2007). A system for analyzing children and caregivers’ language about space in structured and unstructured contexts. Spatial Intelligence and Learning Center (SILC) technical report.

- Casey BM, Andrews N, Schindler H, Kersh JE, Samper A, & Copley J. (2008). The development of spatial skills through interventions involving block building activities. Cognition and Instruction, 26(3), 269–309. 10.1080/07370000802177177 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Casasola M, Wei WS, Suh DD, Donskoy P, & Ransom A. (2020). Children’s exposure to spatial language promotes their spatial thinking. Journal of Experimental Psychology: General, 149(6), 1116. https://psycnet.apa.org/doi/10.1037/xge0000699 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clements LJ, LeMahieu RA, Nelson AE, Eason SH, & Dearing E. (2021). Associations between parents number talk and management language with young children. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 73, 101261. 10.1016/j.appdev.2021.101261 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dearing E, Casey BM, Ganley CM, Tillinger M, Laski E, & Montecillo C. (2012). Young girls’ arithmetic and spatial skills: The distal and proximal roles of family socioeconomics and home learning experiences. Early Childhood Research Quarterly, 27, 458–470. 10.1016/j.ecresq.2012.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Distefano R, Galinsky E, McClelland MM, Zelazo PD, & Carlson SM (2018). Autonomy-supportive parenting and associations with child and parent executive function. Journal of Applied Developmental Psychology, 58, 77–85. 10.1016/j.appdev.2018.04.007 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dodici BJ, & Draper DC (2001). Parent-infant/toddler interaction coding system. Ames: Iowa State University [Google Scholar]

- Dodici BJ, Draper DC, & Peterson CA (2003). Early parent—child interactions and early literacy development. Topics in Early Childhood Special Education, 23(3), 124–136. 10.1177/02711214030230030301 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eilam B, & Alon U. (2019). Children’s object structure perspective-taking: training and assessment. International Journal of Science and Mathematics Education, 17(8), 1541–1562. 10.1007/s10763-018-9934-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg S. (1988). Parent-child interaction therapy: Integration of traditional and behavioral concerns. Child & Family Behavior Therapy, 10(1), 33–46. 10.1300/J019v10n01_04 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Eyberg SM, Nelson MM, Ginn NC, Bhuiyan N, & Boggs SR (2013). Dyadic parent–child interaction coding system, 4th edition (DPICS-IV) comprehensive manual for research and training. Gainesville, FL: PCIT International. [Google Scholar]

- Faul F, Erdfelder E, Lang AG, & Buchner A. (2007). G* Power 3: A flexible statistical power analysis program for the social, behavioral, and biomedical sciences. Behavior research methods, 39(2), 175–191. 10.3758/BF03193146 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ferrara K, Hirsh‐Pasek K, Newcombe NS, Golinkoff RM, & Lam WS (2011). Block talk: Spatial language during block play. Mind, Brain, and Education, 5(3), 143–151. 10.1111/j.1751-228X.2011.01122.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Fisher KR, Hirsh‐Pasek K, Newcombe N, & Golinkoff RM (2013). Taking shape: Supporting preschoolers’ acquisition of geometric knowledge through guided play. Child development, 84(6), 1872–1878. 10.1111/cdev.12091 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gabriel KI, Hong SM, Chandra M, Lonborg SD, & Barkley CL (2011). Gender differences in the effects of acute stress on spatial ability. Sex Roles, 64(1–2), 81–89. https://link.springer.com/content/pdf/10.1007/s11199-010-9877-0.pdf [Google Scholar]

- Garcia D, Rodriquez GM, Hill RM, Lorenzo NE, & Bagner DM (2019). Infant language production and parenting skills: a randomized controlled trial. Behavior therapy, 50(3), 544–557. 10.1016/j.beth.2018.09.003 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Garcia D, Bagner DM, Pruden SM, & Nichols-Lopez K. (2015). Language production in children with and at risk for delay: Mediating role of parenting skills. Journal of Clinical Child & Adolescent Psychology, 44(5), 814–825. 10.1080/15374416.2014.900718 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson EA, Gripshover SJ, Romero C, Dweck CS, Goldin-Meadow S, & Levine SC (2013). Parent praise to 1- to 3-year-olds predicts children’s motivational frameworks 5 years later. Child Development,84(5), 1526–1541. 10.1111/cdev.12064 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gunderson EA, Sorhagen NS, Gripshover SJ, Dweck CS,Goldin-Meadow S, & Levine SC (2018). Parent praise to toddlers predicts fourth grade academic achievement via children’s incremental mindsets. Developmental Psychology,54(3), 397–409. 10.1037/dev0000444 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hart B, & Risley TR (1995). Meaningful differences in the everyday experience of young American children. Paul H Brookes Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Hawes Z, Moss J, Caswell B, Naqvi S. & MacKinnon S. (2017). Enhancing children’s spatial and numerical skills through a dynamic spatial approach to early geometry instruction: Effects of a 32-week intervention. Cognition and Instruction, 35(3), 236–264. 10.1080/07370008.2017.1323902 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Heflin BH, Heymann P, Coxe S, & Bagner DM (2020). Impact of Parenting Intervention on Observed Aggressive Behaviors in At-Risk Infants. Journal of Child and Family Studies, 29, 2234–2245. 10.1007/s10826-020-01744-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]