Abstract

BACKGROUND

The aim of the study was to assess the relationship between performing remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic and the level of job and life satisfaction, as well as the assumed, intermediary role of the level of perceived stress and such resources as self-efficacy and self-esteem.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

The study, implemented with the use of an internet application, included 283 employees. Data were gathered using a job and life satisfaction scale, the Short Scale for Measuring General Self-Efficacy Beliefs, the Rosenberg Self-Esteem Scale, Perceived Stress Scale PSS-4 and a demographic information form.

RESULTS

The results showed the existence of a relationship between performing remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic and job and life satisfaction, and that the level of perceived stress, self-efficiency and self-esteem plays an intermediary role in this relationship. Remote working is associated with life and job satisfaction, and this relationship is mediated by levels of experienced stress, self-efficacy and self-esteem.

CONCLUSIONS

Findings indicate that remote working is associated with higher levels of job and work satisfaction. This relationship is mediated by levels of perceived stress, self-efficacy and self-esteem.

Keywords: COVID-19, home office, personal resources, stress, subjective well-being

BACKGROUND

Over the past several dozens of years there have been numerous changes in the labor sphere, which have undoubtedly influenced the style of work and contributed to the emergence of new forms of fulfilling professional duties. Technological advances have contributed to changing working conditions, including the emergence of remote work. In order to keep their jobs, employees were forced to adapt to the surrounding reality (Rożnowski et al., 2006). One of the challenges that a modern employee has recently been faced with was the implementation of new solutions as a result of the COVID-19 virus. Since March 11, 2020, when the WHO announced the outbreak of a pandemic as a result of the spread of SARS-CoV-2 disease, our functioning across all areas of life has changed. As indicated by various sources, the current epidemic situation requires personnel to make many changes in their previous behavior patterns (Finset et al., 2020). Due to the fear of an unknown disease and as a result of introduced restrictions and constraints, we had to learn to organize our personal and professional life differently than until now. One of the changes implemented by a number of employers was the transition to full-time or hybrid remote work. According to a report from the website Pracuj.pl (2020) this is how 42% of respondents are currently performing their professional duties. In the wake of the current pandemic, it seems key to identify resources that will facilitate the transition of employees, positively affect their satisfaction and reduce the costs borne by them. Given the need to adapt to new living and working conditions, the beliefs of an individual about himself and the surrounding world prove to be of paramount importance (Rożnowski & Kot, 2015). As emphasized by Bandura (1997), one of them is the belief in one’s self-efficacy; it also represents one of the resources that allow an individual to cope with a difficult situation. Due to the emergence of COVID-19, many people have developed negative emotions, stress, and decreased well-being (Grover et al., 2020); fear, anxiety, apprehension as well as a decline in the sense of control have also appeared (Finset et al., 2020). Anxiety related to the existing virus and a sense of solitude can trigger negative thoughts and even depression, while the results of the most recent studies show that self-esteem protects the individual against the effects of COVID-19, even in a situation where a high level of anxiety is accompanied by a feeling of loneliness (Rossi et al., 2020). It is precisely personal and social resources that are currently the key predictors of mental health understood as emotional, social, and psychological wellbeing (Super et al., 2020). Therefore, the aim of the study is to determine the relationship between remote work performed in the time of the COVID-19 pandemic and satisfaction with life and work, taking into account the intermediary role of the level of perceived stress, self-efficacy and self-esteem.

JOB AND LIFE SATISFACTION

The construct of well-being has been a pertinent area of study in this regard. Well-being is theorized as the presence of a state of wellness, instead of mere absence of illness. Ryff and Keyes (1995) define well-being as striving for perfection represented by recognition of an individual’s true potential. Well-being is linked to two broad perspectives, i.e., hedonic (subjective well-being) and eudemonic (psychological well-being). The former deals with dimensions pertaining to physical health, affect, and life satisfaction, to name a few (Diener & Diener, 1995), whereas the latter includes constructs such as personal development, relating to the environment and self-actualization (Kashdan et al., 2008). Life satisfaction and subjective happiness are two broad areas studied under the framework of subjective well-being (Lyubomirsky, 2001). The former refers to a cognitive evaluation about one’s life (Diener et al., 2003), whereas the latter is a subjective evaluation about whether an individual is happy or unhappy (Lyubomirsky, 2001). High well-being has been reported to influence health (Seligman, 1998) and job satisfaction (Connolly & Viswesvaran, 2000). Subjective well-being is influenced by a constellation of various components of positive psychology such as self-efficacy, resilience, hope and optimism (Culbertson et al., 2010; Luthans et al., 2007).

REMOTE WORK AND JOB AND LIFE SATISFACTION

Until recently, telework was treated as a benefit because it offered employees freedom in the organization of work. As demonstrated by research from the beginning of the 21st century, the remote implementation of professional duties may increase employee satisfaction and productivity (e.g., Bailey & Kurland, 2002; Lipińska-Grobelny, 2014). Moreover, it is associated with less role conflict, work-role stress and fatigue resulting from work, and the experienced sense of freedom affects job performance (Gajendran & Harrison, 2007). It also has a positive effect on the employees’ well-being (Anderson et al., 2015), increases the quality of life and the sense of security (Filardí et al., 2020) and lowers job-induced stress (Hayman, 2010). Control and autonomy, flexibility and the ability to concentrate seem to be the factors most significantly influencing the overall quality of life of a remote worker (Van Sell & Jacobs, 1994). That said, not all studies have confirmed the effect of such a working mode on the overall satisfaction with life, and it is even indicated that the partners of employees have experienced reduced satisfaction (Vittersø et al., 2003). In Norwegian studies, remote employees displayed an increased sense of belonging understood as being in a safe and familiar environment (physical belonging), satisfaction with relationships (social belonging) and satisfaction with access to events and the possibility of participating in educational and professional activities (community belonging) (Vittersø et al., 2003). Certain discrepancies in the assessment of remote work may be attributed to the frequency of contacts with the supervisor and colleagues, the received technical assistance and boundary management support (Oakman et al., 2020), as well as whether remote work is voluntary or imposed (Kaduk et al., 2019).

STRESS DURING THE PANDEMIC AND JOB AND LIFE SATISFACTION

The COVID-19 pandemic was surprising for everyone and impacted not just our professional functioning but also satisfaction in various areas of life and ways of coping with a difficult situation. The evaluation of the situation as stressful is associated with the experience of suffering harm or loss, a perception of threat or a challenge, and depends on the current characteristics of the event, i.e., novelty, controllability and predictability (Lazarus & Folkman, 1984). These elements are undoubtedly determinants of what the pandemic situation has brought us – it has disturbed the balance between the needs of the individual and the conditions for their implementation. An individual may find it stressful to introduce changes in work procedures, as well as to perform tasks inconsistent with his expectations and values (Schultz & Schultz, 2002). A large share of these stressors have emerged from the need to continue working from home during the pandemic. Perceived stress reduces satisfaction with life (e.g., Lazarus & Folkman, 1984) and self-esteem, and worsens somatic problems and emotional discomfort (Schultz & Schultz, 2002). However, the severity of a stressor is influenced not only by its harmfulness, but also by the individual’s resources and properties, and the support received, conditioning the reaction to the stressor and the process of coping with a difficult situation, as well as the individual’s attitude and experience.

During the pandemic, over 74% of respondents reported an average level of stress, and well-being decreased by over 71% (Grover et al., 2020). Stress and the accompanying negative emotions increased with increasing duration of isolation (Grover et al., 2020), and satisfaction with life deteriorated especially in March and May 2020, when many countries introduced lockdowns (Zacher & Rudolph, 2021). This is understandable, as staying in isolation for even a few days can lead to anxiety, fear, loneliness, anger, and symptoms of depression (Reynolds et al., 2008), as well as boredom and sadness (Droit-Volet et al., 2020).

Experiencing the threat of fear of coronavirus transmission has an impact on the assessment of health-related quality of life. The most common manifestations are pain and discomfort, as well as depression and anxiety, which increase with age, especially in people with a reduced income, chronically ill, or facing the consequences of the pandemic (Ping et al., 2020). However, research shows that the imposed quarantine was conducive to the improvement of family relations (Grover et al., 2020), which can be a springboard from difficulties and thus increase our comfort.

On the other hand, continuing remote work was associated with an increase in motivation, satisfaction and greater enjoyment, which ultimately translated into productivity (Susilo, 2020). This could have been partly due to less fear of job loss as well as an increased sense of control over one’s life. Moreover, access to technology can help to overcome the negative symptoms of the experienced difficult situation related to social isolation (Smith et al., 2018). Therefore, it can be assumed that telework will have positive effects on overall satisfaction, even though employees may experience technostress due to the need to use information and communication technologies. Interestingly, there is a correlation between technostress and behavioral stress and role conflict, but in the case of remote work, paradoxically, this correlation was negative (Molino et al., 2020). However, research shows that there are considerable differences between the levels of perceived stress depending on culture and living conditions. Research conducted during the lockdown among representatives of the French population demonstrated that working from home was associated with lower levels of stress, while in China remote work actually increased stress (Droit-Volet et al., 2020).

SELF-EFFICACY AND JOB AND LIFE SATISFACTION

The ability to exercise control over the nature and quality of one’s life is the essence of humanity (Bandura, 1977, 2001). Self-efficacy begins with the concept of Albert Bandura (1977) and plays a key role in socio-cognitive theory. Following this theory, the variability of an individual’s behavior is caused by changes taking place in the environment. It is assumed that the belief in self-efficacy influences the adaptation of the individual and the changes made by him (Bandura, 2001). In line with the approach of Bandura (1997), self-efficacy means how an individual perceives their ability to cope with certain situations. Moreover, it concerns the belief of an individual about having the ability to carry out certain actions that are necessary to achieve a concrete result (Bandura, 1977, 1997), as well as to engage in problem-solving behavior and strategies that help in coping with life changes. Further, the sense of self-efficacy represents one of the resources that allow an individual to cope with a challenging situation (Bańka & Orłowski, 2014) and stress at work (Maggiori et al., 2016); it also influences whether an individual thinks optimistically or pessimistically (Bandura, 2001). In the context of work, self-efficacy is particularly important because it gives employees confidence in taking control over various aspects of life (Bargsted et al., 2019), including professional life. Self-efficacy plays a vital role in examining the functioning of employees in an organization, assuming a predictive function in connection with various aspects of professional activity and job satisfaction (cf. Stajkovic & Luthans, 1998). People characterized by a high level of self-efficacy enjoy better health (Bandura, 1997) compared to individuals with a low level of self-efficacy. High self-efficacy has been reported as a predictor of well-being (Bandura, 2006). Results of numerous studies indicate that self-efficacy increases the level of perceived job satisfaction (Judge et al., 2005; Mishra et al., 2016; Peng & Mao, 2015). Evidence also demonstrated the intermediary role of self-efficacy in the relationship between personality traits and satisfaction (Maggiori et al., 2016), person-job fit and job satisfaction (Peng & Mao, 2015), perceived work environment and lack of job satisfaction (Zhang et al., 2020). There exists a negative relationship between perceived stress and self-efficacy, and a positive relationship between self-esteem and self-efficacy (Rayle et al., 2005).

SELF-ESTEEM AND JOB AND LIFE SATISFACTION

Self-esteem is another important aspect of one’s emotional health and plays a vital role in subjective well-being. It refers to one’s sense or assessment of one’s own value and worth. Self-esteem can be understood as the degree to which individuals appreciate, approve of or even values themselves (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1991). Rosenberg (1965) defined self-esteem as an attitude that an individual has towards their own self, which may be positive or negative. It is the evaluation part of the self-concept, and a broad representation of one’s self which includes behavioral, cognitive, emotional and evaluative aspects (Blascovich & Tomaka, 1991). Self-esteem has considerable implications for mental health and well-being due to its association with happiness (Diener & Diener, 1995). Furthermore, it is correlated with subjective well-being, namely high positive affect, low negative affect, and high life satisfaction (Diener & Diener, 1995). Many studies conducted to date indicate a positive relationship between the level of self-esteem and satisfaction with life and work (Liu et al., 2017; Rossi et al., 2020). Individuals with high self-esteem have reported fewer symptoms of depression and anxiety (Solomon et al., 1991). In sum, both self-efficacy and self-esteem are constituents of core self-evaluation, which has been shown to increase the level of employee satisfaction with life and work (Judge et al., 2005). Therefore, this study consisted in testing the significance of these two internal resources of employees.

CURRENT STUDY

The implementation of remote work as a way to cope with a difficult situation, such as the threat of a new virus, was a trying challenge for employees and organizations. It required flexibility and the ability to quickly adapt to new solutions. The experience of a new situation influenced various areas of our lives and our satisfaction with them.

The conducted research aimed to provide an answer to the question: How did the level of perceived stress, self-efficacy and self-esteem mediate the relationship between remote work during the coronavirus pandemic and satisfaction with work and personal life?

Taking into consideration the previous research, it can reasonably be assumed that teleworking positively affects employees’ well-being (e.g., Anderson et al., 2015; Bailey & Kurland, 2002) and reduces stress (cf. Hayman, 2010); however, this relationship can be modified by the share of perceived stress (e.g., Lazarus & Folkman, 1984), self-efficacy (e.g., Judge et al., 2005) and self-esteem (e.g., Baumeister et al., 2003; Diener & Diener, 1995) as variables affecting satisfaction. That said, teleworking was a solution resulting from necessity, so its impact on employee satisfaction may be limited (cf. Kaduk et al., 2019).

Based on the literature, the following research hypotheses were advanced:

H1: The level of perceived stress and self-efficacy constitute the intermediary variables of the relationship between remote work and satisfaction with life and work.

H2: The level of perceived stress and self-esteem constitute intermediary variables in the relationship between remote work and satisfaction with life and work.

PARTICIPANTS AND PROCEDURE

PARTICIPANTS

The study covered 283 employees (aged M = 30.86, SD = 11.33). The youngest respondent was 19 years old and the oldest was 62. The typical subject was between 23 and 40 years old, with a median age of 25. Women were in the majority, with 195 employees (approx. 69%), while the number of men was 88 (approx. 31%). The majority of participants were employees working under an employment contract – 58.1%. Individuals employed on the basis of a civil law contract accounted for 29.2%, under a contractual agreement 5%, while the self-employed represented 7.6%. 54.5% of the respondents had never worked remotely before, 34.8% rarely, while 10.7% worked in remote mode occasionally.

PROCEDURE

The study was conducted online using the MS Office package. It was voluntary and anonymous. The link to the questionnaires was made available to people employed in various industries and organizations. The study lasted from the end of March to the end of April 2020, during the total national lockdown introduced in Poland.

MEASURES

The following were used:

A self-designed questionnaire used to measure satisfaction with professional and personal life. The basis for the construction of the tool is the results of exploratory factor analysis carried out with the SPSS 26 package, which allowed us to identify 3 factors: job satisfaction (e.g., relations with the supervisor and colleagues), satisfaction with employment conditions (e.g., employment stability, salary level and personal development opportunities) and satisfaction with personal life (e.g., personal/family life, health status, relationship with a partner/spouse). These factors explain more than 40% of the total variance. The test consists of 12 items. The respondents answered on a scale from 0 to 10 regarding their satisfaction (0 – dissatisfied and 10 – satisfied) with particular areas of life in accordance with the assumptions of Cantril’s Ladder (1965). The tool proved to be reliable (Cronbach’s α for all factors above .7) and accurate.

The Short Scale for Measuring General Self-Efficacy Beliefs (Atroszko et al., 2017), which contains 2 statements – “Usually, I am able to cope with what happens to me” and “I can solve most problems if I put enough effort into it”. The research provided answers to what extent the statements were true on a scale from 1 to 9 (1 – no and 9 – yes).

Self-Esteem Scale (SES; Rosenberg, 1965, in the Polish adaptation by Dzwonkowska et al., 2008). The scale consists of 10 statements regarding beliefs about oneself, and the respondent’s task is to determine on a 4-point scale (from 1 – strongly agree to 4 – strongly disagree) how much they agree with them. The scale is a one-dimensional method.

Perceived Stress Scale (PSS-4; Cohen et al., 1983, in the Polish adaptation of Atroszko, 2015). Here, the questions concern recent feelings and thoughts, and the respondent’s task is to determine the frequency of their occurrence on a 5-point scale from 1 (never) to 5 (very often).

The particulars contained demographic questions and included questions about the consequences of experiencing a pandemic situation, including the implementation of remote work and previous experience related to it. The respondents answered the question about frequency of remote work on a five-point scale (1 – not at all, 2 – seldom, 3 – sometimes, 4 – often, 5 – always).

RESULTS

The means, standard deviations and reliabilities for all the tested variables are shown in Table 1.

Table 1.

Means, standard deviations and reliabilities for the tested variables

| Variables | M | SD | α |

|---|---|---|---|

| Job satisfaction | 7.36 | 1.94 | .89 |

| Satisfaction with employment conditions | 6.02 | 2.29 | .81 |

| Life satisfaction | 7.38 | 1.58 | .73 |

| Perceived stress | 11.33 | 2.98 | .75 |

| Self-efficacy | 13.35 | 1.97 | .82 |

| Self-esteem | 25.76 | 3.54 | .88 |

To verify the models regarding the hypotheses on the relationship between performing remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic and the level of satisfaction with life and work among the respondents, as well as the assumed, intermediary role in this respect, the level of perceived stress and the sense of self-efficacy and self-esteem, we conducted an analysis of direct and indirect effects in SEM models using the Amos 26 package.

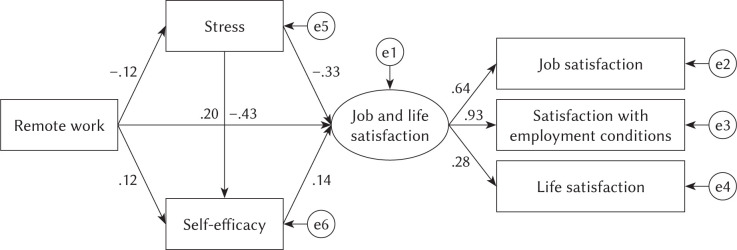

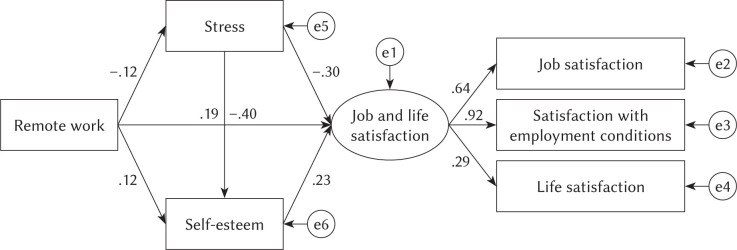

The obtained results of the strength of the relationship between the variables as well as the fit of the models are presented in Figures 1 and 2.

Figure 1.

Resulting path diagram of the stress and self-efficacy model as mediators between remote work and aspects of job and life satisfaction

Figure 2.

Resulting path diagram of the model of stress and self-esteem as mediators between remote work and aspects of job and life satisfaction

The assumed free-form models for the dependent variable “subjective well-being” proved to be acceptably fitted to the data (Konarski, 2010) and interpretable (Tables 2 and 3). All relations were statistically significant.

Table 2.

Goodness of fit indices for the assumed system of variables “remote work – stress, self-efficacy – job and life satisfaction”

| CMIN (df) | RMSEA (90% CI) | GFI | CFI | RMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 17.50 (6) | .082 (.039-.139) | .980 | .959 | .198 |

| p = .008 | p = .091 |

Note. CMIN – chi-square statistic; RMSEA – root mean square error of approximation; GFI – goodness of fit index; CFI – comparative fit index; RMR – root mean square residuals.

Table 3.

Goodness of fit indices for the assumed system of variables “remote work – stress, self-esteem – job and life satisfaction”

| CMIN (df) | RMSEA (90% CI) | GFI | CFI | RMR |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| 26.29 (6) | .091 (.059-.154) | .971 | .930 | .238 |

| p = .001 | p = .011 | |||

Note. CMIN – chi-square statistic; RMSEA – root mean square error of approximation; GFI – goodness of fit index; CFI – comparative fit index; RMR – root mean square residuals.

It was determined that the mere fact of performing remote work (Figures 1 and 2) is statistically significantly (β = .20, B = .19, p < .01) and positively related to aspects of job and life satisfaction. Therefore, respondents who work remotely more often display a higher level of general satisfaction (direct effect). That said, through the outcomes of analyses of direct and indirect effects for both models of dependence (indirect effect), this result turned out to be significantly (directly) mediated by the level of perceived stress and (indirectly) by the sense of self-efficacy and self-esteem. For both models, the intermediary relationship turned out to be complete mediation (Tables 4 and 5).

Table 4.

Stress and self-efficacy mediation parameters in the relation of the independent and dependent variable in the assumed model

| Hypothesis | Direct effect (SE) | Indirect effect (SE) | Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remote work → Stress, Self-efficacy | .20** (.05) | .06 (.02) | Full mediation |

| → Job and life satisfaction | 90% CI (.101-.286) | 90% CI (.018-.097) |

Note. **p < .01.

Table 5.

Stress and self-esteem mediation parameters in the relation of the independent and dependent variable in the assumed model

| Hypothesis | Direct effect (SE) | Indirect effect (SE) | Mediation |

|---|---|---|---|

| Remote work → Stress, Self-esteem | .19** (.05) | .07 (.03) | Full mediation |

| → Job and life satisfaction | 90% CI (.095-.273) | 90% CI (.031-.117) |

Note. **p < .01.

Therefore, the respondents who work remotely during the COVID-19 pandemic show a certain level of satisfaction with their work and aspects of assessing their lives, but this relationship should be interpreted through the prism of how the level of stress perceived during the last month is assessed, which also indirectly affects the sense of self-efficacy and self-esteem of the respondents. Severe stress experienced during the lockdown along with the resulting, decreased self-esteem and level of self-efficacy could reduce satisfaction with work and the aspects of one’s life. In such a case, the direct relation between performing remote work and the aspects of job and life satisfaction ceases to be relevant in favor of the intermediary variables included.

Therefore, all the assumed hypotheses were confirmed.

DISCUSSION

The purpose of this study was to determine the relationship between performing remote work during the COVID-19 pandemic and the level of job and life satisfaction. Furthermore, we tested the assumed, intermediary role in this respect of the level of perceived stress and such resources as the sense of self-efficacy and self-esteem. From the perspective of the still prevailing COVID-19 pandemic, the most important result is the demonstration of the role of the employees’ internal resources: the level of self-efficacy and self-esteem in the relationship between remote work and job and life satisfaction.

Remote work increases job and life satisfaction, which is consistent with the results of previous studies (cf. Anderson et al., 2015; Bailey & Kurland, 2002). Interestingly, the obtained outcomes show that despite the fact that remote work is imposed from above, it leads to an increase in the level of satisfaction (cf. Kaduk et al., 2019). It is possible that employees who have made a shift to remote work felt a greater sense of safety and stability, as well as belonging (cf. Fílardí et al., 2020; Vittersø et al., 2003). This could be due to the perception of the situation as a prophylaxis against coronavirus infection. In addition, performing one’s professional duties, even if remotely, as well as staying busy, allowed them to avoid persistent thinking about COVID-19, which protects against anxiety and trauma effects (cf. Skalski et al., 2020). On top of that, telework is associated with the assumption that the greater the possibility of controlling one’s working time, the greater the satisfaction (Lipińska-Grobelny, 2014). The advantage of the home office is also saving time, which can be used to build relationships with loved ones. This in turn translates into satisfaction with this area of life (cf. Grover et al., 2020).

Additionally, attention should be given to the fact that the present economy is based on a flexible employment system, and not on a long-lasting relationship with the company as before. Perhaps that is why the need to switch to remote work during the pandemic did not decrease the level of employee life satisfaction. Bańka (2002) also draws attention to the fact that a modern employee feels little attachment to the workplace; he can perform his duties both at home or in a restaurant, on a train or a plane. Consequently, he does not feel discomfort associated with staying outside of his workplace.

The results obtained in our research confirmed that remote work reduces stress and increases self-efficiency and self-esteem. Previous research drew attention to the fact that remote work reduces stress (e.g., Hayman, 2010), which could be the result of functioning at home, i.e., in familiar, favorable conditions but also, despite isolation, it allows one to maintain contact with others through the use of modern technology (cf. Smith et al., 2018). Moreover, the home office may be associated with the possibility of keeping a number of resources that are important from the perspective of the conservation of resource theory, such as the possibility of achieving goals, having permanent employment, a sense of control over one’s life, the ability to organize work or a sense of independence (cf. Hobfoll, 2006). Working from home, the individual does not experience the risk of losing the above, and therefore he does not feel threatened. Moreover, the greater sense of freedom and autonomy translates into the manner of organizing working time and increases self-confidence (cf. Gajendran & Harrison, 2007; Van Sell & Jacobs, 1994). The result showing that the level of perceived stress weakens the level of self-efficacy and self-esteem is consistent with prior reports (cf. Rayle et al., 2005). It is related to the fact that as a result of the perceived stress, the individual loses faith in the hope of success (Kivimäki & Kalimo, 1996).

In line with the expectations, the results of the described research show that the level of stress weakens, and self-efficacy and self-esteem strengthen the relationship between remote work and satisfaction with life and work. Self-efficacy is a quintessential construct impacting subjective well-being (Bandura, 2001). It is defined as an individual’s belief in their ability to work in a direction that helps them achieve their goals (Bandura, 1997), which impacts the kind of activities and efforts that an individual engages in to fulfill their goals (Pajares, 2002). People with low self-efficacy often tend to avoid tasks, anticipating that they will fail, while those with high self-efficacy are more likely to attempt difficult tasks (Bandura, 1997). Given the above, we can deduce that self-efficacy will strengthen the relationship between the need to work remotely, treating it as a challenge, and satisfaction in various areas of life will increase. Lower self-efficacy tends to be related to lower subjective well-being (Bandura, 2006) as well as more symptoms of depression and anxiety. Hence, individuals with high self-efficacy have reported higher levels of subjective well-being as compared to those with a low propensity to believe that they can influence the outcome of their actions (Ryan & Deci, 2001). As mentioned earlier, the possibility of performing work remotely requires taking control over one’s organization of time and pursuing effective action. Self-efficacy influences how an individual thinks and the behaviors they are likely to indulge in, as well as their judgements about how individuals act in stressful situations and cope with adversities (Bandura, 1997). Well-being, on the other hand, is a subjective experience that emerges out of different perceptions pertaining to one’s emotional states or quality of life, according to individuals themselves (Diener, 1984). Higher self-efficacy also helps individuals mediate the stressors faced at work in a more adept manner (Çakar, 2012). On the other hand, a switch to remote work could be stressful due to the coexistence of several stressors simultaneously. Individuals with lower self-efficacy can easily feel overwhelmed at work when faced with harsh situations that tend to increase anxiety and stress, thus narrowing down their problem-solving abilities (Pajares, 2002). Lyubomirsky et al. (2005) found that characteristics such as self-efficacy and optimism encourage more active involvement in pursuing one’s goals. Having high self-efficacy corresponds to better well-being, stress regulation, higher self-esteem as well as greater physical health (Bandura, 1997).

Previous studies show that self-esteem is an intermediary variable between the sense of stress and mental health (Kivimäki & Kalimo, 1996), and that perceived stress has a negative impact on the feeling of happiness (Schiffrin & Nelson, 2010). Lastly, there is a very substantial contribution from the strong relationship of self-esteem with well-being (Bosson et al., 2000) and happiness (Baumeister et al., 2003). Both well-being and self-esteem are important constructs with regard to positive health. It can furthermore be concluded that self-esteem is a quintessential part of one’s notion about the quality of life and thus strongly related to life satisfaction (Diener 1984). The obtained results are in line with previous observations showing that high self-esteem is associated with the feeling of being the right person in the right place (cf. Rossi et al., 2020; Schultz & Schultz, 2002). Therefore, it can be considered that an employee with high self-esteem will be better able to accept the necessity to work remotely and will show greater satisfaction. He will have a positive attitude towards himself and his competences, and employ more effective strategies of self-regulation in a difficult situation or be quicker in implementing alternative solutions if the previous ones have not been effective (cf. Baumeister et al., 2003). Self-esteem protects the individual from the effects of COVID-19, even when a high level of anxiety is accompanied by a feeling of loneliness (Rossi et al., 2020) and related anxiety.

CONCLUSIONS

The research results described above demonstrate that remote work is associated with higher job and work satisfaction. This dependence is mediated by the level of perceived stress, self-efficacy and self-esteem. Probably due to the positive impact of home office work on life and job satisfaction and reducing the level of stress, as many as 87% of employees would like to continue this mode of work after the end of the pandemic (Pracuj.pl, 2020) for employees; despite the pandemic and the need to work from home, remote work brings benefits both to the individual and the company.

Because the feelings of self-efficacy and self-esteem have a major impact on job satisfaction, it would be worthwhile implementing psychological procedures amplifying their level and strength among employees (cf. Bandura, 1977), especially as self-esteem is a predictor of life success (Orth & Robins, 2014), while self-efficacy can help in increasing enthusiasm at work (cf. Laguna et al., 2017) or gaining an advantage against competitors (cf. Mishra et al., 2016). High well-being has been reported to influence health (Seligman, 1998). On the other hand, job satisfaction is also related to a number of variables important for the business, including identification with the company, employee effectiveness and readiness to leave the organization (cf. Zhang et al., 2018). It has a negative effect on the phenomenon of organizational silence and a positive impact on commitment (Peplińska et al., 2020). The strengthening of these variables by the organization is particularly important during the COVID-19 pandemic, when many companies are struggling with problems resulting from the restrictions and are afraid of further consequences for their functioning.

LIMITATIONS AND DIRECTIONS FOR FURTHER RESEARCH

The study group was heterogeneous – because of the lockdown it was difficult to test more specific groups. That is why we could not compare such variables as types of employment or previous experience of remote work. In the future, account must also be taken of demographic variables such as gender, role and age, as we observe differences in the assessment of a difficult situation and the manner of coping with problems depending on gender, the roles performed (see Alon et al., 2020; Harth & Mitte, 2020), and age (cf. Beam & Kim, 2020).

In the future, it would be worth broadening the analyzed variables and considering examining the intermediary role of characteristics of job design in the relationship between self-efficacy and job satisfaction (cf. Bargsted et al., 2019). It would be worth considering the frequency of contacts with the supervisor and colleagues during remote work (cf. Oakman et al., 2020).

Footnotes

TO CITE THIS ARTICLE – Kondratowicz, B., Godlewska-Werner, D., Połomski, P., & Khosla, M. (2022). Satisfaction with job and life and remote work in the COVID-19 pandemic: the role of perceived stress, self-efficacy and self-esteem. Current Issues in Personality Psychology, 10(1), 49–60.

References

- Alon, T., Doepke, M., Olmstead-Rumsey, J., & Tertilt, M. (2020). The impact of COVID-19 on gender equality. CEPR COVID Economics, 4, 62–85. 10.3386/w26947 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Anderson, A. J., Kaplan, S. A., & Vega, R. P. (2015). The impact of telework on emotional experience: When, and for whom, does telework improve daily affective well-being? European Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 24, 882–897. 10.1080/1359432X.2014.966086 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Atroszko, B., Swarra, A., & Sendal, L. (2017). A comparison of general education students and special education students in terms of self-efficacy and hopelessness. In M. McGreevy & R. Rita (eds.), CER Comparative European Research 2017: Proceedings, Research Track of the 7th Biannual CER Comparative European Research Conference (pp. 124–127). Sciemcee Publishing. [Google Scholar]

- Atroszko, P. A. (2015). The structure of study addiction: Selected risk factors and the relationship with stress, stress coping and psychosocial functioning (Unpublished doctoral thesis). University of Gdansk. [Google Scholar]

- Bailey, D., & Kurland, N. (2002). A review of telework research: Findings, new directions, and lessons for the study of modern work. Journal of Organizational Behavior, 23, 383–400. 10.1002/job.144 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1977). Self-efficacy: Toward a unifying theory of behavioral change. Psychological Review, 84, 191–215. 10.1037//0033-295X.84.2.191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (1997). Self-efficacy: The exercise of control. W. H. Freeman Company. [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (2001). Social cognitive theory: an agentic perspective. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 1–26. 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bandura, A. (2006). Toward a psychology of human agency. Perspectives on Psychological Science, 1, 164–180. 10.1111/j.1745-6916.2006.00011.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bańka, A. (2002). Społeczna psychologia środowiskowa [Environmental social psychology]. Scholar.

- Bańka, A., & Orłowski, K. (2014). Makiawelizm nauczycieli jako przyczyna i skutek kryzysu zawodowego oraz funkcjonalnego szkoły [Machiavellianism of teachers as a cause and effect of professional and functional school crisis]. In K. Popiołek, A. Bańka, & K. Balawajder (eds.), Społeczna psychologia stosowana. Człowiek w obliczu zagrożeń współczesnej cywilizacji [Applied social psychology. Human being in the face of threats of contemporary civilization] (pp. 196–209). Stowarzyszenie Psychologia i Architektura. [Google Scholar]

- Bargsted, M., Ramírez-Vielma, R., & Yeves, J. (2019). Professional self-efficacy and job satisfaction: The mediator role of work design. Journal of Work and Organizational Psychology, 35, 157–163. 10.5093/jwop2019a18 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Baumeister, R., Campbell, J., Krueger, J., & Vohs, K. (2003). Does high self-esteem cause better performance, interpersonal success, happiness, or healthier lifestyles? Psychological Science in the Public Interest, 4, 1–44. 10.1111/1529-1006.01431 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beam, C., & Kim, A. (2020). Psychological sequelae of social isolation and loneliness might be a larger problem in young adults than older adults. Psychological Trauma: Theory, Research, Practice, and Policy, 12, 58–60. 10.1037/tra0000774 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Blascovich, J., & Tomaka, J. (1991). Measures of self-esteem. In J. P. Robinson, P. R. Shaver, & L. S. Wrightsman (eds.), Measures of social psychological attitudes, Vol. 1. Measures of personality and social psychological attitudes (pp. 115–160). Academic Press. [Google Scholar]

- Bosson, J. K., Swann, W. B, Jr., & Pennebaker, J. W. (2000). Stalking the perfect measure of implicit self-esteem: The blind men and the elephant revisited? Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 79, 631–643. 10.1037/0022-3514.79.4.631 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Çakar, F. S. (2012). The relationship between the self-efficacy and life satisfaction of young adults. International Education Studies, 5, 123–130. 10.5539/ies.v5n6p123 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cantril, H. (1965). Pattern of human concerns. Rutgers University Press.

- Cohen, S., Kamarck, T., & Mermelstein, R. (1983). A global measure of perceived stress. Journal of Health and Social Behavior, 24, 385–396. 10.2307/2136404 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Connolly, J. J., & Viswesvaran, C. (2000). The role of affectivity in job satisfaction: a meta-analysis. Personality and Individual Differences, 29, 265–281. 10.1016/S0191-8869(99)00192-0 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Culbertson, S., Fullagar, C., & Mills, M. (2010). Feeling good and doing great: The relationship between psychological capital and well-being. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 15, 421–433. 10.1037/a0020720 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E. (1984). Subjective well-being. Psychological Bulletin, 95, 542–575. 10.1037/0033-2909.95.3.542 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E., & Diener, C. (1995). The wealth of nations revisited: Income and quality of life. Social Indicators Research, 36, 275–286. 10.1007/BF01078817 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Diener, E., Oishi, S., & Lucas, R. E. (2003). Personality, culture, and subjective well-being: Emotional and cognitive evaluations of life. Annual Review of Psychology, 54, 403–425. 10.1146/annurev.psych.54.101601.145056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Droit-Volet, S., Gil, S., Martinelli, N., Andant, N., Clinchamps, M., Parreira, L., Rouffiac, K., Dambrun, M., Muguet, P., Dubuis, B., Pereira, B., COVISTRESS network, Bouillon, J. B., & Dutheil, F. (2020). Time and COVID-19 stress in the lockdown situation: Time free, “dying” of boredom and sadness. PLoS One, 15, e0236465. 10.1371/journal.pone.0236465 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dzwonkowska, I., Lachowicz-Tabaczek, K. & Łaguna, M. (2008). Samoocena i jej pomiar. Polska adaptacja skali SES M. Rosenberga [Self-esteem and its measurement. Polish adaptation of Rosenberg’s SES scale]. Pracownia Testów Psychologicznych. [Google Scholar]

- Fílardí, F., de Castro, R. M., & Zaníní, M. T. F. (2020). Advantages and disadvantages of teleworking in Brazilian public administration: Analysis of SERPRO and federal revenue experiences. Cadernos EBAPE.BR, 18, 28–46. 10.1590/1679-395174605x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Finset, A., Bosworth, H., Butow, P., Gulbrandsen, P., Hulsman, R. L., Pieterse, A. H., & van Weert, J. (2020). Effective health communication–a key factor in fighting the COVID-19 pandemic. Patient Education and Counseling, 103, 873–876. 10.1016/j.pec.2020.03.027 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gajendran, R. S., & Harrison, D. A. (2007). The good, the bad, and the unknown about telecommuting: Meta-analysis of psychological mediators and individual consequences. Journal of Applied Psychology, 92, 1524–1541. 10.1037/0021-9010.92.6.1524 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grover, S., Sahoo, S., Mehra, A., Avasthi, A., Tripathi, A., Subramanyan, A., Pattojoshi, A., Rao, G., Saha, G., Mishra, K., Chakraborty, K., Rao, N., Vaishnav, M., Singh, O., Dalal, P., Chadda, R., Gupta, R., Gautam, S., Sarkar, S., & Rao, T. (2020). Psychological impact of COVID-19 lockdown: an online survey from India. Indian Journal of Psychiatry, 62, 354–362. 10.4103/psychiatry.IndianJPsychiatry_427_20 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harth, N. S., & Mitte, K. (2020). Managing multiple roles during the COVID-19 lockdown: Not men or women, but parents as the emotional “loser in the crisis”. Social Psychological Bulletin, 15, 1–17. 10.32872/spb.4347 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hayman, J. (2010). Flexible work schedules and employee well-being. New Zealand Journal of Employment Relations, 35, 76–87. [Google Scholar]

- Hobfoll, S. E. (2006). Stres, kultura i społeczność. Psychologia i filozofia stresu [Stress, culture and community. Psychology and philosophy of stress]. Gdańskie Wydawnictwo Psychologiczne. [Google Scholar]

- Judge, T. A., Bono, J. E., Erez, A., & Locke, E. (2005). Core self-evaluations and job and life satisfaction: The role of self-concordance and goal attainment. Journal of Applied Psychology, 90, 257–268. 10.1037/0021-9010.90.2.257 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaduk, A., Genadek, K., Kelly, E. L., & Moen, P. (2019). Involuntary vs. voluntary flexible work: Insights for scholars and stakeholders. Community, Work & Family, 22, 412–442. 10.1080/13668803.2019.1616532 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kashdan, T. B., Biswas-Diener, R., & King, L. A. (2008). Reconsidering happiness: The costs of distinguishing between hedonics and eudaimonia. The Journal of Positive Psychology, 3, 219–233. 10.1080/17439760802303044 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Kivimäki, M., & Kalimo, R. (1996). Self-esteem and the occupational stress process: Testing two alternative models in a sample of blue-collar workers. Journal of Occupational Health Psychology, 1, 187–196. 10.1037/1076-8998.1.2.187 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Konarski, R. (2010). Modele równań strukturalnych. Teoria i praktyka [Structural equation models. Theory and practice]. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN. [Google Scholar]

- Laguna, M., Razmus, W., & Żaliński, A. (2017). Dynamic relationships between personal resources and work engagement in entrepreneurs. Journal of Occupational and Organizational Psychology, 90, 248–269. 10.1111/joop.12170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lazarus, R. S., & Folkman, S. (1984). Stress, appraisal and coping. Springer. [Google Scholar]

- Lipińska-Grobelny, A. (2014). Psychological determinants of portfolio workers’ satisfaction with life. Health Psychology Report, 2, 280–290. 10.5114/hpr.2014.46696 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Liu, H., Zhang, X., Chang, R., & Wang, W. (2017). A research regarding the relationship among intensive care nurses’ self-esteem, job satisfaction and subjective well-being. International Journal of Nursing Sciences, 4, 291–295. 10.1016/j.ijnss.2017.06.008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Luthans, F., Avolio, B. J., Avey, J. B., & Norman, S. M. (2007). Positive psychological capital: Measurement and relationship with performance and satisfaction. Personnel Psychology, 60, 541–572. 10.1111/j.1744-6570.2007.00083.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky, S. (2001). Why are some people happier than others? The role of cognitive and motivational processes in well-being. American Psychologist, 56, 239–249. 10.1037/0003-066X.56.3.239 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lyubomirsky, S., King, L., & Diener, E. (2005). The benefits of frequent positive affect: Does happiness lead to success? Psychological Bulletin, 131, 803–855. 10.1037/0033-2909.131.6.803 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maggiori, C., Johnston, C. S., & Rossier, J. (2016). Contribution of personality, job strain, and occupational self-efficacy to job satisfaction in different occupational contexts. Journal of Career Development, 43, 244–259. 10.1177/0894845315597474 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mishra, U. S., Patnaik, S., & Mishra, B. B. (2016). Augmenting human potential at work: an investigation on the role of self-efficacy in workforce commitment and job satisfaction. Polish Journal of Management Studies, 13, 134–144. 10.17512/pjms.2016.13.1.13 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Molino, M., Ingusci, E., Signore, F., Manuti, A., Giancaspro, M. L., Russo, V., Zito, M., & Cortese, C. G. (2020). Wellbeing costs of technology use during COVID-19 remote working: an investigation using the Italian translation of the Technostress Creators Scale. Sustainability, 12, 5911. 10.3390/su12155911 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Oakman, J., Kinsman, N., Stuckey, R., Graham, M., & Weale, V. (2020). A rapid review of mental and physical health effects of working at home: How do we optimise health? BMC Public Health, 20, 1825. 10.1186/s12889-020-09875-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Orth, U., & Robins, R. W. (2014). The development of self-esteem. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 23, 381–387. 10.1177/0963721414547414 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pajares, F. (2002). Gender and perceived self-efficacy in self-regulated learning. Theory into Practice, 41, 116–125. 10.1207/s15430421tip4102_8 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peng, Y., & Mao, C. (2015). The impact of person-job fit on job satisfaction: The mediator role of self-efficacy. Social Indicators Research, 121, 805–813. 10.1007/s11205-014-0659-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Peplińska, A., Kawalec, K., Godlewska-Werner, D., & Połomski, P. (2020). Work engagement, organizational commitment and the work satisfaction of tax administration employees: The intermediary role of organizational climate and silence in the organizations. Human Resources Management, 3–4, 127–151. 10.5604/01.3001.0014.1678 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Ping, W., Zheng, J., Niu, X., Guo, C., Zhang, J., Yang, H., & Shi, Y. (2020). Evaluation of health-related quality of life using EQ-5D in China during the COVID-19 pandemic. PLoS One, 15, e0234850. 10.1371/journal.pone.0234850 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pracuj.pl . (2020). Pół roku nowej normalności. Pracownicy i kandydaci o rynku pracy [Six months of a new normal. Workers and candidates on the labour market]. Retrieved from https://prowly-uploads.s3.eu-west-1.amazonaws.com/uploads/4091/assets/244900/original-b2ad8a15654b658a9a3f5e09c22c505d.pdf

- Rossi, A., Panzeri, A., Pietrabissa, G., Manzoni, G. M., Castelnuovo, G., & Mannarini, S. (2020). The anxiety-buffer hypothesis in the time of COVID-19: When self-esteem protects from the impact of loneliness and fear on anxiety and depression. Frontiers in Psychology, 11, 2177. 10.3389/fpsyg.2020.02177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rożnowski, B., Biela, A., & Bańka, A. (2006). Praca i organizacja w procesie zmian [Work and organisation in the change process]. Stowarzyszenie Psychologia i Architektura.

- Rożnowski, B., & Kot, P. (2016). Przenoszenie przekonania o własnej skuteczności w nową rolę życiową: model moderacyjny i mediacyjny [Projecting self-efficacy beliefs to a new role in life: mediation model]. Czasopismo Psychologiczne, 22, 205–218. 10.14691/CPPJ.22.2.205 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Rayle, A. D., Arredondo, P., & Kurpius, S. E. R. (2005). Educational self-efficacy of college women: Implications for theory, research, and practice. Journal of Counseling and Development, 83, 361–366. 10.1002/j.1556-6678.2005.tb00356.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Reynolds, D. L., Garay, J. R., Deamond, S. L., Moran, M. K., Gold, W., & Styra, R. (2008). Understanding, compliance and psychological impact of the SARS quarantine experience. Epidemiology and Infection, 136, 997–1007. 10.1017/S0950268807009156 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rosenberg, M. (1965). Society and the adolescent self-image. Princeton University Press.

- Ryan, R. M., & Deci, E. L. (2001). On happiness and human potentials: a review of research on hedonic and eudaimonic well-being. Annual Review of Psychology, 52, 141–166. 10.1146/annurev.psych.52.1.141 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ryff, C. D., & Keyes, C. L. M. (1995). The structure of psychological well-being revisited. Journal of Personality and Social Psychology, 69, 719–727. 10.1037/0022-3514.69.4.719 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schiffrin, H., & Nelson, S. (2010). Stressed and happy? Investigating the relationship between happiness and perceived stress. Journal of Happiness Studies, 11, 33–39. 10.1007/s10902-008-9104-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Schultz, D. P., & Schultz, S. E. (2002). Psychologia a wyzwania dzisiejszej pracy [Psychology and the challenges of today’s work]. Wydawnictwo Naukowe PWN.

- Seligman, M. E. P. (1998). Building human strength: Psychology’s forgotten mission. APA Monitor, 29, 2. [Google Scholar]

- Skalski, S., Uram, P., Dobrakowski, P., & Kwiatkowska, A. (2020). Thinking too much about the novel coronavirus. The link between persistent thinking about COVID-19, SARS-CoV-2 anxiety and trauma effects. Current Issues in Personality Psychology, 8, 169–174. 10.5114/cipp.2020.100094 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Smith, B. G., Smith, S. B., & Knighton, D. (2018). Social media dialogues in a crisis: a mixed-methods approach to identifying publics on social media. Public Relations Review, 44, 562–573. 10.1016/j.pubrev.2018.07.005 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Solomon, S., Greenberg, J., & Pyszczynski, T. (1991). Terror management theory of self-esteem. In C. R. Snyder & D. R. Forsyth (eds.), Handbook of social and clinical psychology: The health perspective (pp. 21–40). Pergamon Press. [Google Scholar]

- Stajkovic, A. D., & Luthans, F. (1998). Self-efficacy and work-related performance: a meta-analysis. Psychological Bulletin, 124, 240–261. 10.1037/0033-2909.124.2.240 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Super, S., Pijpker, R., & Polhuis, K. (2020). The relationship between individual, social and national coping resources and mental health during the COVID-19 pandemic in the Netherlands. Health Psychology Report, 9, 186–192. 10.5114/hpr.2020.99028 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Susilo, D. (2020). Revealing the effect of work-from-home on job performance during the COVID-19 crisis: Empirical evidence from Indonesia. Journal of Contemporary Issues in Business & Government, 26, 23–40. 10.47750/cibg.2020.26.01.002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Van Sell, M., & Jacobs, S. M. (1994). Telecommuting and the quality of life: a review of the literature and a model for research. Telematics and Informatics, 11, 81–95. 10.1016/0736-5853(94)90033-7 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Vittersø, J., Akselsen, S., Evjemo, B., Julsrud, T. E., Yttri, B., & Bergvik S. (2003). Impacts of home-based telework on quality of life for employees and their partners. Quantitative and qualitative results from a European survey. Journal of Happiness Studies, 4, 201–233. 10.1023/A:1024490621548 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zacher, H., & Rudolph, C. (2021). Individual differences and changes in subjective wellbeing during the early stages of the COVID-19 pandemic. American Psychologist, 76, 50–62. 10.1037/amp0000702 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, L. F., Fu, M., & Li, D. T. (2020). Hong Kong academics’ perceived work environment and job dissatisfaction: The mediating role of academic self-efficacy. Journal of Educational Psychology, 112, 1431–1443. 10.1037/edu0000437 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang, W., Meng, H., Yang, S., & Liu, D. (2018). The influence of professional identity, job satisfaction, and work engagement on turnover intention among township health inspectors in China. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 15, 988. 10.3390/ijerph15050988 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]