Abstract

Background:

Although pitch count and rest guidelines have been promoted for youth and adolescent baseball players for nearly 2 decades, compliance with guidelines remains poorly understood.

Purpose/Hypothesis:

The purpose of this study was to determine the frequency of compliance with Major League Baseball (MLB) Pitch Smart guidelines as well as the association between compliance and range of motion (ROM), strength, velocity, injury, and pitcher utilization. It was hypothesized that pitchers in violation of current recommendations would have increased strength, velocity, and injury.

Study Design:

Case-control study; Level of evidence, 3.

Methods:

This was a prospective, multicenter study of 115 high school pitchers throughout the United States. Pitchers were surveyed about their compliance with current off-season, rest-related guidelines, and history of injury. During the preseason, pitchers underwent standardized physical examinations, and pitch velocity was measured. Pitch counts were collected during the baseball season that followed. Dynamometer strength testing of shoulder forward flexion, and external rotation as well as grip strength was recorded. We compared pitchers who were compliant with recommendations with those who were noncompliant using Student t and Mann-Whitney U tests.

Results:

Based on preseason data, 84% of pitchers had violated current Pitch Smart guidelines. During the season, 14% had at least 1 violation of the Pitch Smart guidelines. Across both the preseason survey and in-season pitch counts, 89% of players had at least 1 violation of the Pitch Smart guidelines. While there were no significant differences in ROM or strength, the noncompliant group had higher maximum pitch velocity than the compliant group (74 ± 8 vs 69 ± 5 mph [119 ± 13 vs 111 ± 8 kph], respectively; P = .009). Players’ self-reported velocity differed significantly from the direct measurement, for both peak velocity (80 ± 6 vs 73 ± 8 mph [129 ± 9 vs 117 ± 13 kph], respectively; P < .001) and mean velocity (73 ± 8 vs 53 ± 27 mph [117 ± 13 vs 85 ± 43 kph], respectively; P < .001).

Conclusion:

Most high school pitchers were not fully compliant with current Pitch Smart guidelines, and they tended to overestimate their peak velocity by 7 mph (11 kph). Pitchers who threw with greater velocity were at higher risk for violating Pitch Smart recommendations.

Keywords: baseball, guidelines, injury, overhead throwing, pitch count, pitching, shoulder, youth

In youth and adolescent athletes, baseball pitching is a frequent cause of shoulder and elbow injuries.8,12,13 The incidence of these injuries appears to be increasing with time.10,18,23 These injuries are multifactorial, with multiple contributing factors, such as increasing single-sport specialization1,31,36 and the increasing use of weighted ball programs.19,27,30

Pitcher workload is also thought to contribute to injuries. 15 The relationship between pitch counts and arm pain was originally demonstrated in a large community study performed through the American Sports Medicine Institute. 22 Multiple subsequent studies have confirmed the relationship between workload and arm pain.6,7,12,20,25,26,35 This relationship may be driven by changes in mechanics with fatigue.9,14,28 However, although there is a clear relationship between pain and workload, not all studies have confirmed a relationship between injury and workload.8,25,32 This may be because workload is a complex concept: for instance, not all pitches are equivalent, with higher velocity pitches potentially placing players at increased risk for injury. 4 Intuitively, pitchers who throw with high velocity are more likely to be heavily utilized; thus, velocity and workload interact. In addition, variability in strength and condition can affect how workload is tolerated between pitchers.

While previous studies have demonstrated that compliance with pitch count recommendations remains variable,11,17,21,37 compliance with other guidelines, such as rest between seasons, not pitching and playing catcher during the same season, and not playing for multiple teams simultaneously, is unknown. Thus, it remains unclear whether injury risk is driven more by in-season or offseason violations of current recommendations. This may be why, even with 100% compliance with current pitch count guidelines, pain and abnormalities on magnetic resonance imaging (MRI) scans remain common. 29 Furthermore, pitching leads to multiple adaptive, potentially protective changes,3,34 and thus, the role of rest during the offseason in injury risk remains unclear.

Major League Baseball (MLB) has developed a set of guidelines for youth pitchers in the United States (US) based on age (Pitch Smart; https://www.mlb.com/pitch-smart/pitching-guidelines). The MLB Pitch Smart guidelines are the current standard for pitch count recommendations in youth baseball. Based on the current literature, it remains unclear how frequently pitchers are fully compliant with current recommendations; whether full compliance with rest recommendations is associated with range of motion (ROM), strength, and pitch velocity at the beginning of the season, and whether full compliance with current recommendations is associated with a decreased history of or risk for injury.

The objective of this study was to address: (1) how frequent are violations of current recommendations; and (2) whether better ROM/strength, higher pitch velocity, or history of injury is associated with more frequent violations of current Pitch Smart recommendations. We hypothesized that pitchers in violation of current recommendations would have increased strength, velocity, and injury.

Methods

Institutional review board approval was obtained for the study protocol. We prospectively recruited high school pitchers within the Northeastern, Southeastern, Midwestern, and Western regions of the United States (US) into a single-season, multicenter prospective study. The study was started and cancelled in both 2020 and 2021 due to the coronavirus pandemic and completed in 2022, as that season proceeded without interruption by the pandemic in each region. Included were students who participated in baseball at schools at which the study authors were affiliated. Excluded were pitchers with a current injury precluding their ability to throw, pitchers older than 18 years without consent, and pitchers younger than 18 years without both parental consent and player assent. Each participating school approved the study via their athletic directors or district research officials as appropriate depending upon the school protocol.

Baseline survey data were collected from all participating players within the 2 weeks before the initial game of the season (Appendix Table A1). At the same time point, a standardized physical examination was performed on all players. Because the study took place across multiple centers with multiple examiners, we first conducted a reliability study for the steps to include in the physical examination. In this reliability study, which was conducted at a single institution with 5 research assistants on 30 collegiate baseball players, the examiners received no training so as to replicate the situation within the study. Intraclass correlation coefficients were calculated from the continuous data, with 0.75 considered as the lower limit of acceptable. From the discrete data, the Cohen kappa values were calculated, with 0.6 considered as the lower limit of acceptable. The results of the reliability study are shown in Appendix Table A2.

Only physical examination maneuvers that could be performed reliably with no training were performed; thus, based on the reliability study, we included shoulder and elbow ROM, dynamometer strength testing of shoulder forward flexion and external rotation, grip strength, plank-hold time, and single-leg squat (Appendix Table A2). Pitch velocity was recorded as the mean of 5 fastballs thrown after completing their standard warm-up via radar gun (Stalker Sport 2, Stalker).

During the course of a single season, the athletic trainers for each participating school were contacted weekly for pitch counts and injury data. All injuries were categorized using the MLB Health Information Tracking System. 2 Athletic trainers were told that an injury was either (1) the development of pain that led to cessation of participation in a game or practice preventing return to that game or practice session or (2) a pain leading to cessation of a player's customary participation. 33

Sample Size Calculation

Velocity and injury rates were used to power the study, as our initial study purpose was to examine the associations between pitch counts, pitch velocity, and injury. To allow a power analysis, 3 high schools, with 83 pitchers, participated in a pilot study. These pitchers exhibited a mean (±SD) velocity of 74 ± 6.6 miles per hour (mph; 119.1 ± 10.6 kph). Based upon a previous study, 8 mph (12.9 kph) was felt to be a clinically significant difference between injured and uninjured. 8 A 10% injury rate was assumed based on the clinical experience of the senior author (P.N.C.). Assuming a non-normal distribution and P value of .05 as significant, 90 players would be necessary to achieve 80% power.

Compliance With MLB Pitch Smart Guidelines

Each player was evaluated for compliance with the following guidelines according to the MLB Pitch Smart program 24 : taking at least 3 consecutive months off overhead throwing each year, avoiding playing for multiple teams, and avoiding playing catcher while pitching. In-season pitch counts were compared with the following guidelines according to age group.

For 14- to 16-year-olds: Per day: maximum, 95 pitches

With 0 days of rest: maximum 30 pitches

With 1 day of rest: maximum 45 pitches

With 2 days of rest: maximum 60 pitches

With 3 days of rest: maximum 75 pitches

With 4 days of rest: maximum 95 pitches

For 17- to 18-year-olds:

Per day: maximum 105

With 0 days of rest: maximum 30 pitches

With 1 day of rest: maximum 45 pitches

With 2 days of rest: maximum 60 pitches

With 3 days of rest: maximum 80 pitches

With 4 days of rest: maximum 105 pitches

Any pitcher who pitched for 3 consecutive days or violated the Pitch Smart recommendations was considered to be noncompliant.

Statistical Analysis

All analysis were conducted in Excel Version 16 (Microsoft) and SPSS 24 (IBM). Descriptive statistics were calculated and are presented as means and standard deviations with ranges or as percentages with numerical values. We compared pitchers who were compliant with recommendations with those who were noncompliant, with continuous variables compared using the Student t test or Mann-Whitney U test as appropriate depending upon data normality as defined using the Kolmogorov-Smirnov test, and discrete variables compared using the chi-square test or Fisher exact test as appropriate depending upon cell populations. Whereas we had initially planned to compare between groups in injury incidence during the season, these analyses were not conducted, as only a single injury occurred.

We also evaluated the association between self-reported (as indicated on the preseason survey) and radar gun-measured peak and mean pitch velocities using the Spearman correlation coefficient. A Spearman r value of 1.0 was considered a perfect association of rank; 0 was considered no association between ranks, and -1.0 was considered a perfect negative association of rank.

Results

How Frequent Are Violations of Current Recommendations?

A total of 115 pitchers from 10 high schools participated in the study. The mean ± SD (range) age of the participants was 16.3 ± 1.4 years (14-18 years). These pitchers started pitching at 9 ± 2 years and had 7.2 ± 2.8 years of pitching experience, but they reported starting pitching as early as age 4 years and as late as age 17 years. When surveyed, these pitchers estimated that within a mean game they threw 58 ± 17 (0-90) pitches per game, and 23 ± 13 (0-80) pitches within a mean warm-up. In the season before data collection, they reported playing 48 ± 30 (0-180) games. They reported playing baseball 6 ± 1 (2-7) days per week and 9 ± 3 (3-12) months per year. Based upon the history collected, 84% (97/115) of pitchers were noncompliant with at least 1 of the current Pitch Smart guidelines. In particular, 12% (14/115) of pitchers also played catcher, 65% (75/115) of players reported playing for multiple teams, and 67% (77/115) of players reported taking less than 3 consecutive months off overhead throwing each year.

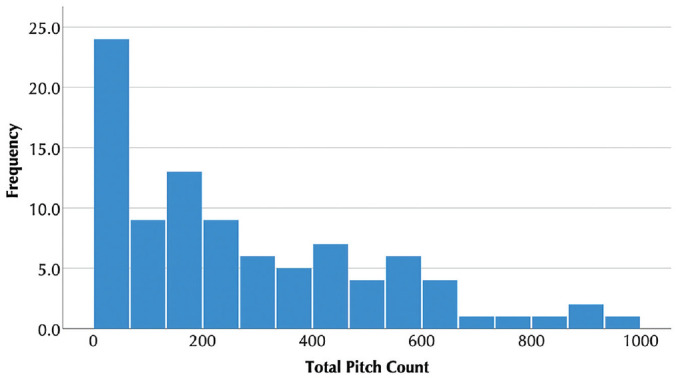

Examining in-game pitch count data collected during the season, 14% (9 of 63) had at least 1 violation of the current pitch counts within the Pitch Smart guidelines, with some players having as many as 5 violations of the pitch count guidelines. Total pitch count for the season was 266 ± 245 (0-959), with 30 ± 28 (0-128) pitches per week, and 26 ± 28 (0-106) pitches per game. Combing the preseason survey and in-season in-game pitch counts, 89% of players (102/115) had at least 1 violation of the current Pitch Smart guidelines, suggesting that few pitchers are in compliance. Pitch counts were distributed unevenly between pitchers, with most pitchers having low utilization and a small number of pitchers having very high utilization (Figure 1). Many teams had 1 pitcher who routinely pitched more than 100 pitches each outing, with 1 included pitcher throwing 120 pitches in a single outing.

Figure 1.

Histogram of total pitch count during the season for the included pitchers.

Is Better ROM/Strength or Higher Velocity Associated With More Frequent Violations of Current Pitch-Smart Recommendations?

There were no significant differences in preseason ROM or strength between players who were compliant with the Pitch Smart between-season rest guideline (n = 38) and those who were noncompliant (n = 77) (P > .072) (Table 1). However, those pitchers who were noncompliant with rest guideline had higher-starting self-reported peak pitch velocity versus those who were compliant (80 ± 6 vs 78 ± 6 mph, respectively; P = .039). In addition, directly measured maximum pitch velocity was significantly higher in pitchers who were noncompliant with the rest guideline than those who were compliant (74 ± 8 vs 69 ± 5 mph, respectively; P = .009).

Table 1.

Comparison of Physical Examination Characteristics and Pitch Velocity According to Compliance With the Between-Season Rest Guidelines a

| Variable | Noncompliant (n = 77) | Compliant (n = 38) | P |

|---|---|---|---|

| Right shoulder flexion, deg | 166 ± 10 | 165 ± 9 | .821 |

| Left shoulder flexion, deg | 167 ± 10 | 167 ± 8 | .860 |

| Right elbow extension, deg | 0 ± 5 | -1 ± 5 | .775 |

| Left elbow extension, deg | 0 ± 5 | -1 ± 6 | .672 |

| Right shoulder abduction strength, kg | 13 ± 5 | 17 ± 8 | .072 |

| Left shoulder abduction strength, kg | 13 ± 4 | 16 ± 7 | .075 |

| Right shoulder external rotation strength, kg | 12 ± 3 | 13 ± 4 | .541 |

| Left shoulder external rotation strength, kg | 12 ± 3 | 12 ± 4 | .256 |

| Right grip strength, kg | 37 ± 12 | 42 ± 14 | .096 |

| Left grip strength, kg | 35 ± 13 | 38 ± 14 | .300 |

| Self-reported mean fastball velocity, mph (kph) | 77 ± 6 (123 ± 9) | 74 ± 6 (119 ± 9) | .057 |

| Self-reported peak fastball velocity, mph (kph) | 80 ± 6 (128 ± 9) | 78 ± 6 (125 ± 9) | .039 |

| Directly measured mean fastball velocity, mph (kph) | 74 ± 8 (119 ± 13) | 69 ± 5 (111 ± 8) | .009 |

| Directly measured peak fastball velocity, mph (kph) | 51 ± 28 (82 ± 45) | 64 ± 15 (103 ± 24) | .609 |

Data are reported as mean ± SD. Boldface P values indicate statistically significant difference between groups (P < .05).

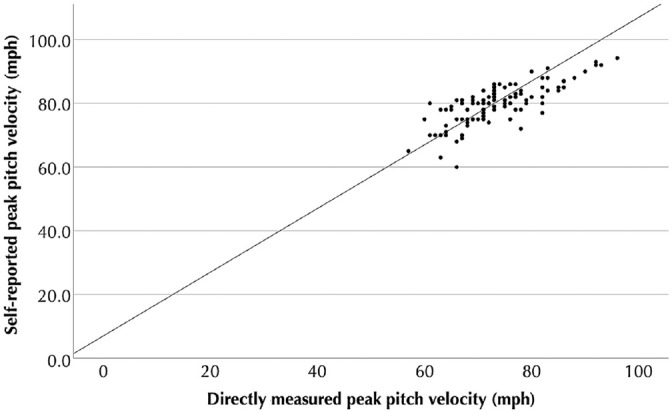

Pitching velocities for all study participants differed significantly between self-reported and directly measured values, for both peak velocity (80 ± 6 vs 73 ± 8 mph [129 ± 9 vs 117 ± 13 kph], respectively; P < .001) and mean velocity (73 ± 8 vs 53 ± 27 mph [117 ± 13 vs 85 ± 43 kph], respectively; P < .001). However, self-reported peak velocity and directly measured peak velocity were highly correlated (r = 0.738, P < .001) (Figure 2). For peak velocity, if it was assumed that each player had exaggerated their velocity by 7 mph (11.3 kph), there were no significant differences between self-reported and directly measured values (P = .280). However, for mean velocity, self-reported and directly measured values were not correlated (r = 0.175, P = .068).

Figure 2.

Scatterplot of directly measured versus self-reported peak pitch velocity. The line demonstrates directly measured peak pitch velocity minus 7 mph (ie, 7 mph of pitcher velocity exaggeration).

Is a History of Injury Associated With More Frequent Violations of Current Pitch Smart Recommendations?

Although we had initially planned to compare in-season injury rates between pitchers who complied with Pitch Smart guidelines and those who were noncompliant, only a single injury occurred during the season and thus this analysis was not conducted. There were no significant differences in the incidence of a history of injury between pitchers who were noncompliant with the between-season rest guideline (31%, 30/97) and those who were compliant (41%, 7/17; P = .285).

Discussion

In this prospective study, most high school pitchers were not fully compliant with current MLB Pitch Smart guidelines. In particular, very few players have 3 months of consecutive rest per year. Pitchers with higher peak velocity were at greater risk of being noncompliant with recommended Pitch Smart guidelines. Noncompliance with the between-season rest guideline was not associated with a history of injury or with differences in ROM or strength during the season or to this point in the players’ career. Noncompliance with the pitch count guidelines was less common, only 14% of players during the season studied. Self-reported peak pitch velocity, after accounting for a 7-mph mean “exaggeration,” suggested that future research should examine the Pitch Smart rest-related guidelines more closely to better understand their role in injury prevention, as pitchers are frequently noncompliant, probably because of the competitive advantage associated with noncompliance.

Within our study, noncompliance with the Pitch Smart guidelines was common. In particular, 12% of pitchers also played the catcher position, 65% of players played for multiple teams, and 67% of players did not take at least 3 consecutive months off overhead throwing of a baseball each year. Playing for multiple teams has been associated with a history of injury in a previous study. 8 Year-round play has also been associated with MRI scan abnormalities despite compliance with pitch count guidelines. 29 However, year-round play may also have some benefits, as a previous study did demonstrate that during the offseason there is thinning and shortening of the ulnar collateral ligament, while during the season there is thickening and lengthening of the ligament. 3 So potentially, rest may lead to deadaptation that could contribute to injury. In a previous study, playing catcher was not a significant risk factor for injury. 16 However, within our own study, only a single injury occurred in the 115 included pitchers despite widespread noncompliance. If noncompliance provides a competitive advantage in the form of increased peak pitch velocity, and without a directly visible downside, as at least within our study injury rates were low, pitchers will almost certainly require more persuasion than suggested guidelines to achieve higher rates of compliance.

Within this study, most athletes were compliant with current pitch count recommendations during the season. Of note, our study is specific to the high school season, where a specific schedule helps teams to follow the guidelines. This is in contrast to a tournament situation, where multiple games are played in a concentrated period of time. A previous retrospective study shows that 50% of players and 90% of teams were in violation of pitch count guidelines in that setting. 17 Another survey study demonstrated that only 60% of players are familiar with guidelines, suggesting that noncompliance should be very common. 11 This matches with a coach survey study, showing that more than half of all coaches admitted to noncompliance with guidelines. 21 Our own study suggests that, at least within the isolated context of the high school season, pitch count violations were uncommon. However, most (65%) players within our study reported that they played for multiple teams, and previous studies have demonstrated that in-game pitches do not capture the entirety of pitch volume. 37 Thus, the actual workload may be higher than measured. Given the substantial evidence connecting workload with injury, ‡‡ our results should not be interpreted to suggest that continued advocacy for pitch counts is unnecessary. However, what may be necessary moving forward is understanding how to individualize workload to each pitcher and what other metrics should be included in workload to further define this term.

Limitations

This study has several limitations. First, recall bias could have influenced player self-reporting on the preseason surveys. Second, this study only covered a single-season, and a multiseason study could find different results, especially as some workload-related effects are cumulative. Third, this was a multicenter study involving multiple examiners across these centers. To mitigate this limitation, only physical examination variables that could be collected reliably without training were collected. Fourth, this study has a limited sample size and may thus be underpowered for some comparisons. Fifth, pitch counts included only the high school teams and thus may be undercounts for those players involved with multiple teams. This study was conducted over the short term. As such, noncompliance over time could lead to cumulative damage and eventual injury that did not occur in this study. Finally, compliance was defined by several metrics, so some players may have complied with some Pitch Smart guidelines and not others but were still considered noncompliant to avoid any confusion.

Conclusion

Most high school pitchers were not fully compliant with current Pitch Smart guidelines, and they tend to overestimate their peak velocity by 7 mph. Pitchers who threw with greater velocity were at higher risk for violating Pitch Smart recommendations.

Appendix

Appendix Table A1.

Preseason Survey a

| Questions | Potential Answers/Units |

|---|---|

| Which hand do you use to pitch with? | Right, left |

| What is your height? | Feet, inches |

| What is your weight? | lb |

| What is your mean fastball velocity? | Miles per hour |

| What is your peak fastball velocity? | Miles per hour |

| At what age did you start pitching? | Years |

| How long have you been pitching? | Years |

| How many pitches do you throw in the mean game? Warm-up? | NA |

| Do you play for any other teams? | Yes, no |

| How many games did you play last season? | NA |

| How many games did you pitch last season? | NA |

| How many days a week do you play baseball? | Days |

| How many months per year do you play baseball? | Months |

| How many consecutive months off throwing did you have last year? | Months |

| Have you ever participated in a “showcase”? | Yes, no |

| Have you ever returned to the mound after being removed? | Yes, no |

| Do you play any positions other than pitcher? | Yes, no |

| Which positions? | Fielding |

| How many innings do you play these other positions each game? | NA |

| Do you play other sports? | Yes, no |

| Which other sports? | NA |

| Have you ever participated in a weighted ball program? | Yes, no |

| With which weight ball? | Heavier, lighter |

| Have you used any other programs to increase your velocity? | Yes, no |

| Which programs? | NA |

| Have you ever been diagnosed with a pitching-related injury? | Yes, no |

| Describe the injury and treatment. | NA |

NA, not applicable.

Appendix Table A2.

Results of Reliability Study for the Physical Examination a

| Variable | ICC [95% CI] | Included? |

|---|---|---|

| External rotation motion in abduction, deg | 0.629 [0.379-0.779] | No |

| Internal rotation motion in abduction, deg | 0.432 [0.049-0.661] | No |

| Active forward elevation motion, deg | 0.772 [0.619-0.864] | Yes |

| Elbow extension motion, deg | 0.848 [0.746-0.909] | Yes |

| Elbow flexion, deg | 0.55 [0.246-0.731] | No |

| Elbow carrying angle, deg | 0.759 [0.597-0.856] | Yes |

| Shoulder abduction strength, kg b | 0.993 [0.989-0.996] | Yes |

| Shoulder external rotation strength, kg c | 0.986 [0.977-0.992] | Yes |

| Grip strength, kg | 0.939 [0.898-0.964] | Yes |

| Plank time, seconds d | 0.487 [0.141-0.693] | No |

| Crossed single-leg toe-touch test, normal/abnormal e | κ = 0.305 | No |

All ROM variables were active ROM. CI, confidence interval; ICC, intraclass correlation coefficient; ROM, range of motion.

Data collected with the shoulder at 30° of abduction, 30° of flexion, and neutral rotation.

Data collected with the shoulder in full adduction, neutral flexion/extension, and neutral rotation.

Players were asked to assume a plank position and a timer was set to determine time between when the player assumed the position and when the player was no longer able to maintain their body as a flat plane.

Players were asked to stand on their right foot, touch their right hallux with their left index finger, and vice versa. If the player was unable to complete both sides without a Trendelenburg shift of the hips, the test was considered normal.

Footnotes

Final revision submitted April 27, 2023; accepted May 19, 2023.

One or more of the authors has declared the following potential conflict of interest or source of funding: funding was provided by a grant from Major League Baseball. B.J.E. has received research/grant support from Arthrex, Depuy, Linvatec, Smith & Nephew, and Stryker; nonconsulting fees from Arthrex; consulting fees from Arthrex and DePuy; and education payments from Pinnacle, Arthrex, and Smith & Nephew. E.N.B. has received grant support from DJO; education payments from Alpha Orthopedic Systems, Smith & Nephew, and Arthrex; and hospitality payments from Stryker. C.C. has received consulting fees, nonconsulting fees, education payments, and royalties from Arthrex. M.T.F. has received research/grant support from Encore Medical, Major League Baseball, Regeneration Technologies, and Smith & Nephew; education payments from Evolution Surgical; consulting fees from Smith & Nephew and Stryker; nonconsulting fees from Smith & Nephew and Integra LifeSciences; royalties from Smith & Nephew; hospitality payments from Wright Medical; and has stock/stock options in Sparta. M.V.S. has received research support from Arthrex; education payments from Arthrex; consulting fees from Flexion Therapeutics and Stryker; and nonconsulting fees from Arthrex. P.N.C. has received education payments from Active Medical; consulting fees from DePuy/Medical Device Business Services, DJO, and Responsive Arthroscopy; nonconsulting fees from Arthrex; royalties from DePuy and Responsive Arthroscopy; and has stock/stock options in Titin KM Biomedical. AOSSM checks author disclosures against the Open Payments Database (OPD). AOSSM has not conducted an independent investigation on the OPD and disclaims any liability or responsibility relating thereto.

Ethical approval for this study was obtained from the University of Utah (No. IRB 00112443), Vanderbilt University Medical Center (No. 212376), Mayo Clinic (No. 19-012432), and Philadelphia University/Thomas Jefferson University (No. 19D.916).

References

- 1. Bell DR, Post EG, Trigsted SM, Hetzel S, McGuine TA, Brooks MA. Prevalence of sport specialization in high school athletics. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(6):1469-1474. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Camp CL, Dines JS, List JP, van der, et al. Summative report on time out of play for Major and Minor League Baseball: an analysis of 49,955 injuries from 2011 through 2016. Am J Sports Medicine. 2018;46(7):1727-1732. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Chalmers P, English J, Cushman DM, et al. The ulnar collateral ligament responds to stress in professional pitchers. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2021;30(3):495-503. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Chalmers PN, Erickson BJ, Ball B, Romeo AA, Verma NN. Fastball pitch velocity helps predict ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in Major League Baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Medicine. 2016;44(8):2130-2135. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Chalmers PN, Mcelheny K, D’Angelo J, et al. Effect of weather and game factors on injury rates in professional baseball players. Am J Sports Medicine. 2022;50(4):1130-1136. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Chalmers PN, Mcelheny K, D’Angelo J, et al. Is workload associated with latissimus dorsi and teres major tears in professional baseball pitchers? An analysis of days of rest, innings pitched and batters faced. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2022;31(5):957-962. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Chalmers PN, Mcelheny K, D’Angelo J, Ma K, Rowe D, Erickson BJ. Is workload associated with hamstring and calf strains in professional baseball players? An analysis of days of rest, innings fielded, and plate appearances. Sports Health. 2023;15(4):479-485. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Chalmers PN, Sgroi T, Riff AJ, et al. Correlates with history of injury in youth and adolescent pitchers. Arthroscopy. 2015;31(7):1349-1357. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Darke JD, Dandekar EM, Aguinaldo AL, Hazelwood SJ, Klisch SM. Effects of game pitch count and body mass index on pitching biomechanics in 9- to 10-year-old baseball athletes. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(4):2325967118765655. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. DeFroda SF, Goodman AD, Gil JA, Owens BD. Epidemiology of elbow ulnar collateral ligament injuries among baseball players: National Collegiate Athletic Association Injury Surveillance Program, 2009-2010 through 2013-2014. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(9):2142-2147. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Eichinger JK, Goodloe JB, Lin JJ, et al. Pitch count adherence and injury assessment of youth baseball in South Carolina. J Orthop. 2020;21:62-68. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Erickson BJ, Chalmers PN, Axe MJ, Romeo AA. Exceeding pitch count recommendations in little league baseball increases the chance of requiring Tommy John surgery as a professional baseball pitcher. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(3):2325967117695085. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Erickson BJ, Chalmers PN, Bush-Joseph CA, Romeo AA. Predicting and preventing injury in Major League Baseball. Am J Orthop (Belle Mead NJ). 2016;45(3):152-156. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Erickson BJ, Sgori T, Chalmers PN, et al. The impact of fatigue on baseball pitching mechanics in adolescent male pitchers. Arthroscopy. 2016;32(5):762-771. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Feeley BT, Schisel J, Agel J. Pitch counts in youth baseball and softball. Clin J Sport Med. 2018;28(4):401-405. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Cutter GR, et al. Risk of serious injury for young baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2011;39(2):253-257. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Greiner JJ, Trotter CA, Walczak BE, Hetzel SJ, Baer GS. Pitching behaviors in youth baseball: comparison with the Pitch Smart guidelines. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021;9(11):23259671211050130. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Hodgins JL, Vitale M, Arons RR, Ahmad CS. Epidemiology of medial ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(3):729-734. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Kaizu Y, Sato E, Yamaji T. Biomechanical analysis of the pitching characteristics of adult amateur baseball pitchers throwing standard and lightweight balls. J Phys Ther Sci. 2020;32(12):816-822. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Keller RA, Mehran N, Khalil LS, Ahmad CS, ElAttrache N. Relative individual workload changes may be a risk factor for rerupture of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2017;26(3):369-375. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Knapik DM, Continenza SM, Hoffman K, Gilmore A. Youth baseball coach awareness of Pitch Count guidelines and overuse throwing injuries remains deficient. J Pediatr Orthop. 2018;38(10):e623-e628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Lyman S, Fleisig GS, Andrews JR, Osinski ED. Effect of pitch type, pitch count, and pitching mechanics on risk of elbow and shoulder pain in youth baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2002;30(4):463-468. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Mahure SA, Mollon B, Shamah SD, Kwon YW, Rokito AS. Disproportionate trends in ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction: projections through 2025 and a literature review. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2016;25(6):1005-1012. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Major League Baseball. Pitch Smart guidelines. Accessed January 7, 2023. https://www.mlb.com/pitch-smart/pitching-guidelines.

- 25. Matsuura T, Takata Y, Iwame T, et al. Limiting the pitch count in youth baseball pitchers decreases elbow pain. Orthop J Sports Med. 2021;9(3):2325967121989108. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Mehta S, Tang S, Rajapakse C, Juzwak S, Dowling B. Chronic workload, subjective arm health, and throwing injury in high school baseball players: 3-year retrospective pilot study. Sports Health. 2022;14(1):119-126. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Melugin HP, Smart A, Verhoeven M, Dines JS, Camp CL. The evidence behind weighted ball throwing programs for the baseball player: do they work and are they safe? Curr Rev Musculoskelet Med. 2021;14(1):88-94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Okoroha KR, Meldau JE, Lizzio VA, et al. Effect of fatigue on medial elbow torque in baseball pitchers: a simulated game analysis. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(10):2509-2513. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Pytiak AV, Stearns P, Bastrom TP, et al. Are the current Little League Pitching Guidelines adequate? A single-season prospective MRI study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(5):2325967117704851. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Reinold MM, Macrina LC, Fleisig GS, Aune K, Andrews JR. Effect of a 6-week weighted baseball throwing program on pitch velocity, pitching arm biomechanics, passive range of motion, and injury rates. Sports Health. 2018;10(4):327-333. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Rugg C, Kadoor A, Feeley BT, Pandya NK. The effects of playing multiple high school sports on National Basketball Association players’ propensity for injury and athletic performance. Am J Sports Med. 2018;46(2):402-408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Saltzman BM, Mayo BC, Higgins JD, et al. How many innings can we throw: does workload influence injury risk in Major League Baseball? An analysis of professional starting pitchers between 2010 and 2015. J Shoulder Elbow Surg. 2018;27(8):1386-1392. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Smith MV, Davis R, Brophy RH, Prather H, Garbutt J, Wright RW. Prospective player-reported injuries in female youth fast-pitch softball players. Sports Health. 2015;7(6):497-503. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Warden SJ, Roosa SMM, Kersh ME, et al. Physical activity when young provides lifelong benefits to cortical bone size and strength in men. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2014;111(14):5337-5342. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Whiteside D, Martini DN, Lepley AS, Zernicke RF, Goulet GC. Predictors of ulnar collateral ligament reconstruction in Major League Baseball pitchers. Am J Sports Med. 2016;44(9):2202-2209. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Wilhelm A, Choi C, Deitch J. Early sport specialization: effectiveness and risk of injury in professional baseball players. Orthop J Sports Med. 2017;5(9):2325967117728922. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Zaremski JL, Zeppieri G, Jr, Jones DL, et al. Unaccounted workload factor: game-day pitch counts in high school baseball pitchers - an observational study. Orthop J Sports Med. 2018;6(4):2325967118765255. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]