ABSTRACT

Sulfane sulfur, a collective term for hydrogen polysulfide and organic persulfide, often damages cells at high concentrations. Cells can regulate intracellular sulfane sulfur levels through specific mechanisms, but these mechanisms are unclear in Corynebacterium glutamicum. OxyR is a transcription factor capable of sensing oxidative stress and is also responsive to sulfane sulfur. In this study, we found that OxyR functioned directly in regulating sulfane sulfur in C. glutamicum. OxyR binds to the promoter of katA and nrdH and regulates its expression, as revealed via in vitro electrophoretic mobility shift assay analysis, real-time quantitative PCR, and reporting systems. Overexpression of katA and nrdH reduced intracellular sulfane sulfur levels by over 30% and 20% in C. glutamicum, respectively. RNA-sequencing analysis showed that the lack of OxyR downregulated the expression of sulfur assimilation pathway genes and/or sulfur transcription factors, which may reduce the rate of sulfur assimilation. In addition, OxyR also affected the biosynthesis of L-cysteine in C. glutamicum. OxyR overexpression strain Cg-2 accumulated 183 mg/L of L-cysteine, increased by approximately 30% compared with the control (142 mg/L). In summary, OxyR not only regulated sulfane sulfur levels by controlling the expression of katA and nrdH in C. glutamicum but also facilitated the sulfur assimilation and L-cysteine synthesis pathways, providing a potential target for constructing robust cell factories of sulfur-containing amino acids and their derivatives.

IMPORTANCE

C. glutamicum is an important industrial microorganism used to produce various amino acids. In the production of sulfur-containing amino acids, cells inevitably accumulate a large amount of sulfane sulfur. However, few studies have focused on sulfane sulfur removal in C. glutamicum. In this study, we not only revealed the regulatory mechanism of OxyR on intracellular sulfane sulfur removal but also explored the effects of OxyR on the sulfur assimilation and L-cysteine synthesis pathways in C. glutamicum. This is the first study on the removal of sulfane sulfur in C. glutamicum. These results contribute to the understanding of sulfur regulatory mechanisms and may aid in the future optimization of C. glutamicum for biosynthesis of sulfur-containing amino acids.

KEYWORDS: Corynebacterium glutamicum, OxyR, transcriptional regulation, sulfane sulfur removal, L-cysteine production

INTRODUCTION

Corynebacterium glutamicum is an important industrial microorganism, which has been widely used to produce various amino acids such as L-glutamate (1), L-lysine (2), and L-cysteine (3). The thiol group of L-cysteine contains a sulfur atom that shows high redox activity, which has led to the wide usage of L-cysteine in cosmetics, pharmaceuticals, agriculture, and feed industries (3 – 5). In the global market, the demand for L-cysteine is more than 4,000 tons per year and is growing rapidly (6). Most industrial production of L-cysteine is still done using the traditional production mode, hydrolysis of keratin (1), but this method has great limitations, such as low yields and high-environmental pollution. Scientists have been increasingly interested in L-cysteine production by microbial fermentation (3, 5, 7 – 9). Due to the good tolerance to L-cysteine and GRAS status (generally regarded as safe), C. glutamicum is a good chassis for L-cysteine biosynthesis (3, 10, 11). Notably, sulfur is an essential component of L-cysteine, and it participates in the biosynthesis of L-cysteine through the sulfur assimilation pathway in C. glutamicum, including sulfate and thiosulfate assimilation pathways, which will inevitably accumulate large amounts of sulfane sulfur in the production process.

Sulfane sulfur, including hydrogen polysulfide (H2Sn, n ≥ 2) and organic persulfide (RSSnH, RSSnR, n ≥ 2), is an essential element for microorganisms (12, 13) and often coexists with H2S (14, 15). Previously, H2S has been considered a signaling molecule that activates the defense system and protects cells against antibiotics (16). However, this signal function remains to be confirmed due to the lack of specific studies. Recently, scientists have identified that sulfane sulfur, rather than H2S, has this function (17, 18). In addition, sulfane sulfur can not only be used as an antioxidant to maintain cell vitality but is also essential in many physiological processes, such as cytoprotection, antiinflammatory activities, and angiogenesis (19).

Although sulfane sulfur performs important functions, it is also cytotoxic at high levels, and its mechanism of toxicity is not clear. In some microorganisms, sulfane sulfur can be generated from the metabolism of sulfur-containing amino acids or the oxidation of H2S via various enzymes. For example, sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase can oxidize H2S to form sulfane sulfur (20). Sulfane sulfur can also be produced from L-cysteine and its derivatives by cystathionine β-lyase, cystathionine γ-lyase, and 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase (21, 22). For its removal, sulfane sulfur can be oxidized by persulfide dioxygenase (PDO) to sulfite and thiosulfate and can also be reduced by thioredoxin or glutaredoxin to H2S and then released into the air (23, 24). Unless the environment changes, microorganisms can maintain homeostasis of intracellular sulfane sulfur through specific mechanisms (25).

However, few studies have focused on sulfane sulfur removal in C. glutamicum, and great efforts need to be made to better understand the defense mechanism against sulfur stress. OxyR, a transcriptional regulator responding to reactive oxygen species (ROS), is widely distributed in microorganisms, and it plays an important role in H2O2 removal (26 – 28). Previous studies have reported that OxyR functions as a transcriptional repressor of katA gene in Corynebacterium spp., but this repression is relieved in the presence of oxidative stress (29 – 32). OxyR also plays important role in the regulation of iron homeostasis and sulfur metabolism in C. glutamicum (29, 31). Furthermore, Pedre et al. (33) have successfully solved the crystal structures of C. glutamicum OxyR in both reduced and oxidized states and provided molecular insights into the peroxidatic mechanism of H2O2 sensing (33). Since sulfur and oxygen are chalcogens, OxyR may also function in sulfane sulfur removal. In this study, we first investigated the regulatory mechanism of OxyR on sulfane sulfur removal in C. glutamicum. Subsequently, we explored the effect of OxyR on the sulfur assimilation and L-cysteine biosynthesis pathways. Finally, a possible OxyR regulatory mechanism was successfully established for sulfane sulfur removal in C. glutamicum. Understanding this mechanism provides a new prospect for producing sulfur-containing amino acids using C. glutamicum.

RESULTS

C. glutamicum reduces intracellular sulfane sulfur levels

C. glutamicum cells were grown in an LBHIS medium (0.25% yeast extract, 0.5% tryptone, 0.5% NaCl, 1.85% brain heart infusion powder, and 9.1% sorbitol) with different concentrations of polysulfides added, and cell growth and intracellular sulfane sulfur levels were monitored during the growth process. As shown in Fig. 1A and B, cell growth decreased with increased polysulfides, while intracellular sulfane sulfur levels displayed opposite trends. Briefly, when the concentration of polysulfides increased from 0 to 600 µM, cell growth decreased by 60%, while the intracellular sulfane sulfur levels increased by 3.6-fold. In addition, the intracellular H2O2 and ROS levels increased by 3.6- and 2.7-fold in C. glutamicum, respectively (Fig. S1A and B). When C. glutamicum cells were induced with different concentrations of polysulfides (0, 200, 400, and 600 µM) and then incubated in fresh LBHIS medium for 1 h, their intracellular sulfane sulfur levels, respectively, decreased by 39%, 34%, 20%, and 16% with the concomitant release of H2S (3.52, 12.45, 18.24, and 21.56 µM; Fig. 1C). Therefore, our results indicated that C. glutamicum removed the sulfane sulfur from cells, but the mechanism needed to be further explored.

Fig 1.

The generation and degradation of polysulfides in C. glutamicum. (A) Effect of polysulfides on cell growth of C. glutamicum. 0: no polysulfides; 200: 200 µM polysulfides; 400: 400 µM polysulfides; 600: 600 µM polysulfides. (B) Measurement of intracellular polysulfides levels when cells treated with different concentrations of polysulfides. (C) Polysulfides-containing cells were transferred into fresh LBHIS and then determined the residue of polysulfides and the generation of H2S levels after 1 h of cultivation. The data were presented as mean ± SD of three independent biological replicates. The * and ** indicated the significant differences of P ≤ 0.05 and P ≤ 0.01, respectively.

OxyR is essential in sulfane sulfur removal

To investigate the role of OxyR in sulfane sulfur removal, a mutant C. glutamicum strain with oxyR deleted was constructed. As shown in Fig. 2A, the cell growth ability of the oxyR deletion strain was equivalent to that of the C. glutamicum WT (ATCC 13032) strain on LBHIS medium without polysulfides. However, the oxyR deletion strain was more sensitive to polysulfides at 200 µM, and cell growth decreased by 64% compared to the C. glutamicum WT strain after 12 h of cultivation. In addition, the oxyR complementary strain recovered polysulfides resistance (Fig. 2A), and the same results were observed in agar plates cultivation (Fig. S2). When cells cultivated in LBHIS medium, the oxyR deletion strain accumulated intracellular sulfane sulfur more easily than the C. glutamicum WT and oxyR complementary strains, but this difference decreased gradually with the culture process (Fig. 2B). To further explore the function of OxyR, the polysulfides-containing strains, including C. glutamicum WT, oxyR deletion, and oxyR complementary strains (Fig. 2C), were transferred into fresh LBHIS medium; the concentrations of polysulfides and H2S were measured after 1 h of cultivation. As shown in Fig. 2D, oxyR deletion resulted in a 34% increase, relative to C. glutamicum WT, in intracellular polysulfides levels, but exhibited a more than three-fold reduction in H2S release relative to C. glutamicum WT. The oxyR complementary strain showed the same phenotype as C. glutamicum WT. Therefore, our results indicated that OxyR is essential in sulfane sulfur removal in C. glutamicum.

Fig 2.

Effects of oxyR on cell growth, intracellular polysulfides and H2S levels in C. glutamicum. (A) Measurement of cell growth in different oxyR strains when cells are treated with different concentrations of polysulfides. 0: no polysulfides; 200: 200 µM polysulfides. (B) Determination of intracellular sulfane sulfur levels in different oxyR strains when cells are cultivated with LBHIS medium. (C) Measurement of intracellular sulfane sulfur levels of different oxyR strains when cells cultivated with 200 µM polysulfides for 12 h. (D) Measurement of the residue of polysulfides and the generation of H2S in different oxyR strains when the polysulfides-containing strains were transferred into fresh LBHIS medium for 1 h of cultivation. The data were presented as mean ± SD of three independent biological replicates. The * and ** indicated the significant differences of P ≤ 0.05 and P ≤ 0.01, respectively. C. glutamicum WT, C. glutamicum ATCC 13032; △oxyR, C. glutamicum WT with oxyR deletion; △oxyR-R, △oxyR with oxyR complementation.

Comparative transcriptome profiling analyses of C. glutamicum WT and oxyR deletion strains

To better understand the effect of OxyR on sulfane sulfur removal, we performed a comparative transcriptome analysis of the C. glutamicum WT and oxyR deletion strains. The effects of OxyR on global gene expression are shown in Fig. 3. The high Pearson’s correlation coefficients between two independent bioreplicates suggested that these samples had quite similar overall expression patterns (Fig. 3A). Volcano plots were created to identify the differentially expressed genes (DEGs) in the two strains (Fig. 3B). Compared to C. glutamicum WT, a total of 302 genes were upregulated, and 173 genes were downregulated in the oxyR deletion strain, with 36 and 23 genes that were significantly upregulated and downregulated (|Log2 Fold change| > 1), respectively (Table 1). Previous researches have shown that glutaredoxin and thioredoxin can reduce intracellular sulfane sulfur levels (23, 24). Here, we selected seven DEGs (dps, katA, cydA, cydB, cydC, cydD, and nrdH) from RNA-sequencing (RNA-seq) analysis, one glutaredoxin (cg0964), and three thioredoxin genes (trxB1, trxB, and trxC) identified by Kalinowski et al. (34) to verify their sulfane sulfur removal functions. Notably, nrdH also belongs to the glutaredoxin family (34). Specifically, these genes were overexpressed in C. glutamicum WT and oxyR deletion strains, and the resulting strains were cultivated in LBHIS medium with 200 µM polysulfides induction.

Fig 3.

RNA-seq analysis of C. glutamicum WT and oxyR deletion strains with 200 µM polysulfides induction. (A) Pearson correlation coefficients between two independent bioreplicates. (B) Volcano plots of C. glutamicum WT and ΔoxyR strains. C. glutamicum WT, C. glutamicum ATCC 13032; ΔoxyR, C. glutamicum WT with oxyR deletion.

TABLE 1.

Significantly DEGs in oxyR deletion strain compared to the C. glutamicum WT a

| Accession no. | Gene | Predicted function | log2FC |

|---|---|---|---|

| CGL_RS14945 | dps | DNA starvation/stationary phase protection protein | 5.94 |

| CGL_RS01350 | katA | Catalase | 5.03 |

| CGL_RS10835 | – | Hypothetical protein | 4.01 |

| CGL_RS12610 | – | MmgE/PrpD family protein | 3.95 |

| CGL_RS12550 | – | Ferritin | 3.21 |

| CGL_RS05695 | – | NAD(P)/FAD-dependent oxidoreductase | 3.09 |

| CGL_RS05735 | cydA | Cytochrome ubiquinol oxidase subunit I | 2.88 |

| CGL_RS05730 | cydB | Cytochrome d ubiquinol oxidase subunit II | 2.84 |

| CGL_RS06145 | – | Hypothetical protein | 2.70 |

| CGL_RS07515 | – | HigA family addiction module antidote protein | 2.67 |

| CGL_RS05725 | cydD | ABC transporter ATP-binding protein/permease | 2.58 |

| CGL_RS05720 | cydC | Thiol reductant ABC exporter subunit CydC | 2.34 |

| CGL_RS12615 | – | Phospho-3-sulfolactate synthase | 2.30 |

| CGL_RS07520 | – | MFS transporter | 2.21 |

| CGL_RS15250 | – | MFS transporter | 2.19 |

| CGL_RS07765 | – | Hypothetical protein | 2.13 |

| CGL_RS07705 | – | Ferrochelatase | 2.08 |

| CGL_RS06700 | – | Hypothetical protein | 1.96 |

| CGL_RS01370 | – | Branched-chain amino acid transporter AzlD | 1.85 |

| CGL_RS09900 | – | ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | 1.59 |

| CGL_RS01365 | – | AzlC family ABC transporter permease | 1.58 |

| CGL_RS14610 | – | DUF2020 domain-containing protein | 1.45 |

| CGL_RS05700 | – | Hypothetical protein | 1.38 |

| CGL_RS09905 | – | ABC transporter permease | 1.38 |

| CGL_RS07815 | sufC | Fe-S cluster assembly ATPase SufC | 1.22 |

| CGL_RS12190 | – | Sugar ABC transporter permease | 1.21 |

| CGL_RS14950 | – | Fpg/Nei family DNA glycosylase | 1.21 |

| CGL_RS09975 | – | Hypothetical protein | 1.19 |

| CGL_RS05015 | – | Allophanate hydrolase subunit 1 | 1.15 |

| CGL_RS12580 | nrdH | Glutaredoxin-like protein NrdH | 1.11 |

| CGL_RS07030 | – | Universal stress protein | 1.08 |

| CGL_RS09910 | – | ABC transporter permease subunit | 1.07 |

| CGL_RS02540 | tuf | Elongation factor Tu | 1.03 |

| CGL_RS07930 | – | Triose-phosphate isomerase | 1.02 |

| CGL_RS09715 | – | Amino acid ABC transporter permease | 1.02 |

| CGL_RS03300 | – | Ldh family oxidoreductase | 1.01 |

| CGL_RS05705 | – | Patatin family protein | −1.02 |

| CGL_RS14780 | – | Multicopper oxidase family protein | −1.04 |

| CGL_RS14815 | cadA | Cadmium-translocating P-type ATPase | −1.10 |

| CGL_RS15425 | – | Hypothetical protein | −1.11 |

| CGL_RS05715 | – | Peptide synthetase | −1.12 |

| CGL_RS01995 | – | Hemin ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | −1.12 |

| CGL_RS14810 | – | Hypothetical protein | −1.13 |

| CGL_RS04875 | – | Hypothetical protein | −1.16 |

| CGL_RS09775 | pgsA | Magnesium chelatase subunit ChlD-like protein | −1.16 |

| CGL_RS08920 | – | Hypothetical protein | −1.17 |

| CGL_RS04985 | pabB | Aminodeoxychorismate synthase component I | −1.17 |

| CGL_RS09660 | – | Hypothetical protein | −1.26 |

| CGL_RS15410 | yidD | Membrane protein insertion efficiency factor YidD | −1.26 |

| CGL_RS00605 | – | DeoR/GlpR transcriptional regulator | −1.32 |

| CGL_RS04055 | – | Vitamin K epoxide reductase family protein | −1.37 |

| CGL_RS08420 | – | Hypothetical protein | −1.43 |

| CGL_RS10165 | – | Anion permease | −1.43 |

| CGL_RS04660 | urtA | Urea ABC transporter substrate-binding protein | −1.44 |

| CGL_RS05075 | – | Acyl-CoA dehydrogenase family protein | −1.67 |

| CGL_RS09190 | – | Pentapeptide repeat-containing protein | −1.97 |

| CGL_RS03930 | pdxS | Pyridoxal 5'-phosphate synthase lyase subunit | −2.10 |

| CGL_RS06070 | – | Thiamine-binding protein | −2.13 |

| CGL_RS03935 | pdxT | Pyridoxal 5'-phosphate synthase glutaminase subunit | −2.59 |

FC represents Fold change; Significantly DEGs represents |Log2 Fold change| > 1.

As shown in Fig. 4A and B, the intracellular sulfane sulfur levels significantly decreased by 37% and 22% in C. glutamicum WT with katA and nrdH after 8 h of cultivation, respectively, 1.4- and 1.7-fold lower than that of the oxyR deletion strain (decreased by 27% and 13%). In addition, glutaredoxin (cg0964), and thioredoxin (trxB1, trxB, and trxC) also reduced the intracellular sulfane sulfur levels in C. glutamicum WT by 9%, 10%, 12%, and 11%, respectively (Fig. 4A). To further confirm the change in intracellular sulfane sulfur, we selected six overexpression strains (katA, nrdH, cg0964, trxB1, trxB, and trxC) to cultivate in LBHIS medium with 200 µM polysulfides. As shown in Fig. S3, the H2S levels of all overexpression strains increased except katA, suggesting that glutaredoxin (nrdH and cg0964) and thioredoxin (trxB1, trxB, and trxC) participated in reducing intracellular sulfane sulfur to H2S in C. glutamicum.

Fig 4.

Measurement of intracellular sulfane sulfur in C. glutamicum WT (A) and △oxyR (B) strains when overexpressing different candidate genes. The data were presented as mean ± SD of three independent biological replicates. The * and ** indicated the significant differences of P ≤ 0.05 and P ≤ 0.01, respectively. C. glutamicum WT, C. glutamicum ATCC 13032; △oxyR, C. glutamicum WT with oxyR deletion.

OxyR regulates the expression of katA and nrdH in the presence of polysulfides

To clarify the regulatory mechanism of OxyR in the removal of sulfane sulfur in C. glutamicum, real-time quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR) was used to further verify its function. As shown in Fig. 5A, when C. glutamicum WT cells were treated with 200 µM polysulfides, the expression levels of katA and nrdH improved by 3.3- and 2.2-fold compared to the non-polysulfides addition groups. However, the oxyR deletion strain showed no significant difference in nrdH expression levels (Fig. 5B). In addition, complementation of the oxyR strain regained the function of the response to polysulfides (Fig. 5C).

Fig 5.

Effects of OxyR on the endogenous genes of katA and nrdH in C. glutamicum. Measurement of the relative expression levels of katA and nrdH in C. glutamicum WT (A), △oxyR, (B) and △oxyR-R (C) strains with 200 µM polysulfides addition. Three strains C. glutamicum WT, △oxyR, and △oxyR-R cultivated without polysulfides addition groups were used as the reference samples. (D) SDS-PAGE of OxyR protein. EMSA for exploring the effects of polysulfides on the DNA-binding activity of OxyR with katA (E) and nrdH (F) groups without or with 200 µM polysulfides addition. The data were presented as mean ± SD of three independent biological replicates. The * and ** indicated the significant differences of P ≤ 0.05 and P ≤ 0.01, respectively. C. glutamicum WT, C. glutamicum ATCC 13032; △oxyR, C. glutamicum WT with oxyR deletion; △oxyR-R, △oxyR with oxyR complementation.

In order to further explore the regulatory mechanism of OxyR, in vitro electrophoretic mobility shift assay (EMSA) analysis was carried out with or without polysulfides. The purified OxyR protein was prepared for EMSA analysis (Fig. 5D). As shown in Fig. 5E, the DNA-protein complex of katA gradually increased with an increased amount of the OxyR protein in the absence of polysulfides, while this complex decreased with 200 µM polysulfides induced. There were no shifted probes in the nrdH groups in the absence of polysulfides (Fig. 5F). When the EMSA reaction mixtures were induced with 200 µM polysulfides, the DNA-protein complex of nrdH gradually increased with an increased amount of the OxyR protein, while no DNA-protein complex was formed in the negative control. In addition, we also examined the effects of H2O2 on the DNA-binding activity of OxyR with katA and nrdH. The amount of DNA-protein complex of katA was reduced with H2O2 addition (Fig. S4A), However, no DNA-protein complex of nrdH was observed regardless of the presence or absence of H2O2 (Fig. S4B). These results indicated OxyR could directly bind the promoter regions of the katA and nrdH genes. The DNA-binding activity of OxyR with katA was reduced in the presence of either H2O2 or polysulfides, implying that the transcriptional repression of katA by OxyR may be alleviated by either H2O2 or polysulfides induction, while the DNA-binding activity of OxyR with nrdH was enhanced by polysulfides induction.

Bioinformatic analysis revealed that the amino acid sequence of OxyR contains four cysteine residues. A previous study showed that two of them (located at positions 206 and 215) provided free thiol groups for redox response (29). To verify the functional site of OxyR in sulfane sulfur regulation, we constructed three recombinant strains with C206S, C215S, and C206S-C215S double mutations. Then, two reporting plasmids were transferred into six strains (C. glutamicum WT, oxyR deletion, oxyR complementation, OxyRC206S, OxyRC215S, and OxyRC206S-C215S), and the protein expression levels of green fluorescent protein (GFP) were used as an indicator to quantify their function (Fig. S5A). As shown in Fig. S5B, the C. glutamicum WT strains containing two reporting plasmids exhibited lower GFP expression without polysulfides addition, but achieved obviously higher expression in the presence of polysulfides after 8 h of cultivation. When the concentrations of polysulfides increased from 0 to 400 µM, the expression levels improved by 2.1- and 1.4-fold in the PkatA and PnrdH reporting groups, respectively. However, the two promoters led to constant, low expression of GFP in the oxyR deletion strain, regardless of the presence or absence of polysulfides (Fig. S5C). The complementation of oxyR regained the function of response to polysulfides (Fig. S5D). Notably, strains OxyRC206S, OxyRC215S, and OxyRC206S-C215S exhibited a similar phenotype to the oxyR deletion strain (Fig. S5E-G), suggesting that the positions of C206 and C215 may be the functional sites of OxyR in C. glutamicum. In addition, cell growth of the six OxyR strains showed no obvious difference without added polysulfides, but the OxyR-deficient strains, including oxyR deletion, OxyRC206S, OxyRC215S, and OxyRC206S-C215S, exhibited lower cell growth when treated with polysulfides (Fig. S6).

Effect of OxyR on the L-cysteine biosynthesis pathway in C. glutamicum

In order to explore the effect of OxyR on the L-cysteine biosynthesis pathway in C. glutamicum, we summarized expression profiles of genes related to the L-cysteine biosynthesis pathway (including sulfur assimilation pathway) through transcriptome analysis (Fig. 6). As shown in Fig. 6A, the expression levels of cysI and cysJ (key genes for reducing SO32− to S2−) in oxyR deletion strain were significantly decreased, which reduces H2S production. Moreover, the expression of sulfur-related transcription factors (mcbR, cysR, and ssuR) was obviously decreased (Fig. 6B). In particular, the expression level of cysR (a transcription activator for the sulfate pathway) decreased by 46%, which will greatly reduce the sulfate assimilation rate, resulting in an obvious decrease in H2S generated. On the other hand, expression of cysE (a key gene in the L-cysteine synthesis pathway) was also significantly downregulated (about 40%; Fig. 6A), which may reduce the production of O-acetyl-serine (OAS). OAS is the precursor of L-cysteine and often combines with H2S to synthesize L-cysteine. Therefore, the lower accumulation of OAS and H2S may decrease the production of L-cysteine.

Fig 6.

Differential expression of genes involved in the L-cysteine biosynthesis pathway in oxyR deletion strain. (A) An overview of the L-cysteine biosynthesis pathway. Up- and downregulated genes are indicated with a red and blue box, respectively. The color boxes represent the fold change for the genes shown. (B) Fragments per kilobase per million of relative genes or transcription factors in the sulfur assimilation pathway. Glucose-6-P, Glucose-6-phosphate; F-6-P, fructose 6-phosphate; F-1,6-BP, fructose 1,6-bisphosphate; DHAP, dihydroxyacetone phosphate; GA3P, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate; 1,3-BPG, 1,3-bisphosphoglycerate; 3 PG, 3-phosphoglycerate; 2 PG, 2-phosphoglycerate; PEP, phosphoenolpyruvic acid; PYR, pyruvate; Ac-CoA, acetyl coenzyme A; L-SER, L-serine; OAS, O-acetyl-serine; L-CYS, L-cysteine; SSC, S-sulfocysteine; APS, adenosine-5’-phosphosulfate; PAPS, 3’-phosphoadenosine-5’-phosphosulfate. pgi, glucose-6-phosphate isomerase; pfkA, 6-phosphofructokinase; fda, fructosebisphosphate aldolase; tpi, triosephosphate isomerase; gap, glyceraldehyde 3-phosphate dehydrogenase; pgk, phosphoglycerate kinase; gpmA, phosphoglyceromutase; eno, enolase; pyk, pyruvate kinase; aceE, pyruvate dehydrogenase E1 component; gltA, citrate synthase; acn, aconitate hydratase; icd, isocitrate dehydrogenase; odhA, 2-oxoglutarate dehydrogenase; sucDC, succinyl-coA synthetase; sdhCDAB, succinate dehydrogenase CDAB; fum, fumarate hydratase; mdh, malate dehydrogenase; mqo, malate dehydrogenase; cysDN, sulfate adenyltransferase subunit 1,2; cysH, phosphoadenosine-phosphosulfate reductase; cysIJ, sulfite reductase; sseA1, thiosulfate/3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase; serA, phosphoglycerate dehydrogenase; serC, phosphoserine transaminase; serB, phosphoserine phosphatase; cysE, serine acetyltransferase; cysK, cysteine synthase A. C. glutamicum WT, C. glutamicum ATCC 13032; △oxyR, C. glutamicum WT with oxyR deletion.

To verify whether OxyR affected the sulfate or thiosulfate assimilation pathway, three strains of C. glutamicum WT, oxyR deletion, and oxyR complementation were cultivated in LBHIS medium with different concentrations of Na2SO4 and Na2S2O3. After 6 h of cultivation, cell growth, intracellular sulfane sulfur, and H2S levels were measured (Fig. S7). As shown in Fig. S7A and D, when cells were cultivated without Na2SO4 or Na2S2O3, there was no obvious difference in cell growth among the three oxyR strains, but cell growth was gradually reduced with increased Na2SO4 or Na2S2O3 in the oxyR deletion strain. However, the oxyR deletion strain easily accumulated more sulfane sulfur and released less H2S compared with the C. glutamicum WT strain (Fig. S7B and C, Fig. S7E and F). Using the 40 g/L Na2SO4 or Na2S2O3 groups as examples, the sulfane sulfur level of the oxyR deletion strain increased by 35% and 24% in Na2SO4 and Na2S2O3 groups, respectively, but the H2S concentrations decreased by 47% and 36% compared with the C. glutamicum WT strains. After complementation, the oxyR complementary strain restored its function and exhibited the same trends as the C. glutamicum WT strain. Therefore, our results indicated that OxyR could affect sulfate or thiosulfate assimilation rate, consistent with our transcriptome data (Fig. 6; Fig. S7).

Overexpression of oxyR increases L-cysteine production in C. glutamicum

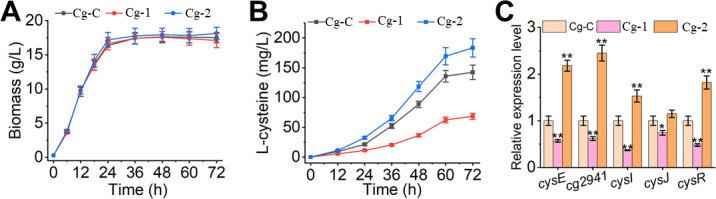

To investigate the effect of oxyR on L-cysteine synthesis, three strains, Cg-C (sdaA::serA, aecD::bcr), Cg-1 (Cg-C deleting oxyR), and Cg-2 (Cg-C overexpressing oxyR), were constructed, and their fermentation profiles were analyzed after 72 h of cultivation (Fig. 7). As shown in Fig. 7A and B, there was no significant difference in the cell growth of the three strains, but the production of L-cysteine was significantly different. Specifically, the L-cysteine production of Cg-2 reached 183 mg/L, a 29% increase compared with the control Cg-C (142 mg/L), while Cg-1 only accumulated 68 mg/L and decreased by 52% after 72 h of fermentation. Furthermore, the expression levels of some key genes in the L-cysteine pathway were determined by RT-qPCR. As expected, compared with the control strain Cg-C, expression levels of the key genes cysE, cg2941, cysI, cysJ, and cysR were all increased by 2.2-, 2.5-, 1.5-, 1.2-, and 1.8-fold in the oxyR overexpressing strain Cg-2 but decreased by 43%, 38%, 63%, 26%, and 52% in the oxyR deletion strain Cg-1, respectively (Fig. 7C). Therefore, our results suggested that OxyR promoted L-cysteine biosynthesis in C. glutamicum via upregulating some pathway-related genes.

Fig 7.

Fermentation profiles of the engineered strains were analyzed in the fermentation medium. Effects of OxyR on cell growth (A), L-cysteine production (B), and key genes expression of L-cysteine biosynthesis pathway (C) were shown. The data were presented as mean ± SD of three independent biological replicates. The * and ** indicated the significant differences of P ≤ 0.05 and P ≤ 0.01, respectively. Cg-C, C. glutamicum deleting sdaA and aecD, and overexpressing serA and bcr; Cg-1, Cg-C deleting oxyR; Cg-2, Cg-C overexpressing oxyR.

DISCUSSION

In recent years, C. glutamicum has been extensively used for the fermentative production of various chemicals (1 – 3, 35). In developing efficient microbial cell factories, high-level accumulation of desired products often brings a variety of intracellular stresses, such as pH, osmotic, and sulfur stress (36 – 39). Sulfur is an essential element in L-cysteine biosynthesis, and it easily accumulates high levels of intracellular sulfane sulfur during this process, which will adversely affect the physiological status of cells. In this study, we observed that high levels of sulfane sulfur (including polysulfides) damaged cells (Fig. 1A), but C. glutamicum can decrease this toxicity through some mechanisms (Fig. 1B and C). However, the complex mechanisms are still unclear in C. glutamicum.

A major finding of the current work was that OxyR regulated the intracellular sulfane sulfur levels in C. glutamicum. OxyR, a LysR family transcription factor, widely exists in bacteria, and its initial function is as an H2O2 sensor to regulate intracellular ROS levels (26, 27). Cells continuously accumulate ROS during the process of growth. Increasing ROS levels may damage cells (40). Due to the defense mechanism, OxyR functions and controls many genes, including katG (catalase/hydroperoxidase I), ahpCF (alkyl hydroperoxide reductase), dps (DNA protection protein), hemH (ferrochelatase), and sufABCDSE (proteins involved in Fe-S cluster assembly and repair), to protect cells against H2O2 toxicity (41). In addition, OxyR acts as a repressor of catalase expression in Corynebacterium spp., but this transcriptional repression by OxyR is alleviated when cells are exposed to oxidative stress (30 – 32). Notably, sulfur and oxygen belong to the same family, and the removal of intracellular sulfane sulfur may be similar to the removal of ROS (42). In this study, we found that the oxyR deletion strain was more sensitive to polysulfides stress (Fig. 2A; Fig. S2), and more easily accumulated intracellular sulfane sulfur than C. glutamicum WT (Fig. 2B), suggesting that OxyR participated in the regulation of intracellular sulfane sulfur.

Some enzymes were reported to be involved in sulfane sulfur removal, such as glutaredoxin and thioredoxin (23, 24), which could convert sulfane sulfur to H2S and release it into the air to relieve sulfur stress. A recent study also revealed that H2S was oxidized to produce octasulfur globules in C. vitaeruminis (43). In this study, overexpression of glutaredoxins (cg0964 and nrdH) and thioredoxins (trxB1, trxB, and trxC) also decreased the intracellular sulfane sulfur via forming H2S in C. glutamicum (Fig. 4A and B; Fig. S3), suggesting that glutaredoxin and thioredoxin act directly in sulfane sulfur detoxification of C. glutamicum, which was consistent with previous studies (23 – 25). In addition, katA and nrdH exhibited an OxyR-related characteristic in the removal of intracellular sulfane sulfur (Fig. 4A and B). To further investigate this regulatory mechanism, RT-qPCR, in vitro EMSA, and reporting system were used and jointly demonstrated that OxyR increased the expression of katA and nrdH in the presence of polysulfides (Fig. 5; Fig. S5). KatA and NrdH were identified to participate in the removal of intracellular sulfane sulfur in C. glutamicum (Fig. 4A and B). NrdH reduced intracellular sulfane sulfur by converting it to H2S (Fig. S3), while KatA might eliminate H2Sn by oxidizing H2Sn to sulfur oxides in C. glutamicum as described by Olson et al. (44). In addition, KatA played a role in intracellular redox homeostasis, which was consistent with previous studies (45 – 47). Finally, we speculated that the two Cys residues (Cys206 and Cys215) might be the functional sites of OxyR because if one or two of them were mutated to serine, the regulatory function would be lost (Fig. S5).

The second finding was that OxyR facilitated the sulfur assimilation and L-cysteine biosynthesis pathways in C. glutamicum. Previously, cysI and cysJ, which could convert sulfite to H2S, were reported as key genes in the sulfate assimilation pathway (48, 49). Yang et al. (50) revealed that the cysS gene played important roles in sulfur assimilation and cysteine import under oxidative stress in C. glutamicum (50). In this study, the expression levels of cysI and cysJ genes in the oxyR deletion strain were significantly decreased (Fig. 6), which might reduce the sulfur assimilation rate. CysR was reported as a transcriptional activator in the sulfate assimilation pathway of C. glutamicum (49). In the oxyR deletion strain, the expression of cysR also decreased by 46% compared with the C. glutamicum WT strain at the transcription level, which may be another reason for the reduced sulfur assimilation rate. Therefore, these results showed that OxyR could affect the assimilation rate of sulfur at the transcriptional level.

The sulfur assimilation pathway is an important part of the L-cysteine biosynthesis (51, 52). Higher assimilation rate may be why L-cysteine production increased. To test this hypothesis, we overexpressed oxyR gene in a cysteine-producing chassis cell of Cg-C (Fig. 7). Expression levels of the sulfur assimilation pathway-related genes (cysI and cysJ) and its transcription factor (CysR) were significantly upregulated in the oxyR overexpression strain Cg-2, suggesting that OxyR improved the sulfur assimilation rate during the fermentation process (Fig. 7C). Moreover, overexpression of oxyR also increased the expression level of cysE, which is the limiting enzyme in L-cysteine biosynthesis to supply more precursor (OAS). Adequate supply of precursor is an effective strategy for the synthesis of target products (3, 5, 7, 53, 54), and a higher OAS supply also promoted the biosynthesis of L-cysteine. Furthermore, the efflux system is considered an effective measure to reduce the cytotoxicity of L-cysteine and increase L-cysteine production (3, 4, 55, 56). Cg2941 was identified as a native L-cysteine transport protein in C. glutamicum (57), and its higher expression in Cg-2 strain also increased L-cysteine production. Finally, the oxyR overexpressing strain Cg-2 exhibited higher L-cysteine production capacity and was increased by approximately 30% compared with the control Cg-C. Therefore, OxyR promoted the biosynthesis of L-cysteine in C. glutamicum, indicating that OxyR can be applied as a new target for the construction of efficient cell factories to produce sulfur-containing amino acids and their derivatives.

Finally, we proposed a model to illustrate the mechanism of OxyR regulating the removal of sulfane sulfur and the biosynthesis pathway of L-cysteine in C. glutamicum (Fig. 8). OxyR directly binds to the DNA-binding sites of the katA and nrdH genes and regulates their expression in the presence of sulfane sulfur. The expressed NrdH reduces intracellular sulfane sulfur levels by forming of H2S. KatA may reduce intracellular sulfane sulfur levels by oxidizing H2Sn to sulfur oxides in C. glutamicum. In addition, the transcriptional repression of katA by OxyR is alleviated under sulfur stress conditions, thereby maintaining intracellular redox homeostasis. Our results indicate that OxyR acts as not only an activator of nrdH but also as a repressor of katA. Meanwhile, OxyR is also involved in L-cysteine biosynthesis pathway. Understanding this mechanism will provide good guidance for the production of sulfur-containing amino acids in the future.

Fig 8.

A possible regulatory mechanism of OxyR on the removal of sulfane sulfur and the biosynthesis pathway of L-cysteine in C. glutamicum.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Strains and growth conditions

The strains used in this study were listed in (Table 2). Escherichia coli DH5α and MG1655 were used as host cells for plasmids construction and genes cloning, respectively. C. glutamicum WT was used as the starting strain for genetic manipulation and functional analysis. Unless otherwise specified, E. coli was routinely cultured at 37°C in LB medium (0.5% yeast extract, 1% tryptone, and 1% NaCl), and C. glutamicum cells were grown at 30°C in LBHIS medium (0.25% yeast extract, 0.5% tryptone, 0.5% NaCl, 1.85% brain heart infusion powder, and 9.1% sorbitol). If necessary, 15 µg/L chloramphenicol or 25 µg/L kanamycin was added to the medium for C. glutamicum cultivation.

TABLE 2.

Strains used in this study

| Strains | Characteristics | Source |

|---|---|---|

| E. coli DH5α | Host for plasmids construction | Invitrogen |

| E. coli MG1655 | Host for genes cloning | Lab storage |

| E. coli BL21 (DE3) | Host for protein expression | Lab storage |

| C. glutamicum WT | Wild-type, ATCC 13032 | Lab storage |

| △oxyR | C. glutamicum WT with oxyR deletion | This study |

| △oxyR-R | △oxyR with oxyR complementation | This study |

| OxyRC206S | C. glutamicum WT with OxyR (C206S) | This study |

| OxyRC215S | C. glutamicum WT with OxyR (C215S) | This study |

| OxyRC206S-C215S | C. glutamicum WT with OxyR (C206S and C215S) | This study |

| Cg-C | C. glutamicum WT with sdaA:: P H7-serA△197AA, aecD :: P H7-bcr | This study |

| Cg-1 | Cg-C with oxyR deletion | This study |

| Cg-2 | Cg-C with plasmid pXMJ-oxyR | This study |

Plasmids and strains construction

All plasmids used in this study were listed in Table 3. The E. coli-C. glutamicum shuttle vectors pXMJ19 and pCRD206 were employed for the plasmids construction of genes overexpression and deletion, respectively. The target regions were cloned from the genomic DNA of E. coli or C. glutamicum by using specific primers (Table S1). The amplified DNA fragments were subcloned into the target vector by the Gibson assembly method (58), and the recombinant plasmids were obtained accordingly. The recombinant expression vectors were used for functional analysis, and the deletion vectors were used for gene deletion. The deletion method was based on the standard protocols by two-step homologous recombination (59).

TABLE 3.

Plasmids used in this study

| Plasmids | Relevant characteristics | Sources |

|---|---|---|

| pCRD206 | KanR , gene deletion plasmid | Lab storage |

| pCRD-oxyR | pCRD206 derivate, deleting oxyR gene | This study |

| pCRD-oxyRC206S | pCRD206 derivate, replacing oxyR gene with OxyR (C206S) | This study |

| pCRD-oxyRC215S | pCRD206 derivate, replacing oxyR gene with OxyR (C215S) | This study |

| pCRD-oxyRC206S-C215S | pCRD206 derivate, replacing oxyR gene with OxyR (C206S and C215S) | This study |

| pCRD-sdaA-PH7-serA | pCRD206 derivate, deleting sdaA, overexpressing serA△197AA from C. glutamicum | This study |

| pCRD-aecD-PH7-bcr | pCRD206 derivate, deleting aecD, overexpressing bcr from E. coli | This study |

| pET21b-OxyR | pET21b derivate, expressing oxyR | This study |

| pXMJ19 | CmR , C. glutamicum-E. coli shuttle vector | Invitrogen |

| pXMJ20 | pXMJ19 derivate, removing BsaI recognition site | Lab storage |

| pXMJ21 | pXMJ 20 derivate, removing lacIq and Ptac promoter and inserting GFP | Lab storage |

| pXMJ-dps | pXMJ19 derivate, inserting dps at MCS | This study |

| pXMJ-katA | pXMJ19 derivate, inserting katA at MCS | This study |

| pXMJ-cydA | pXMJ19 derivate, inserting cydA at MCS | This study |

| pXMJ-cydB | pXMJ19 derivate, inserting cydB at MCS | This study |

| pXMJ-cydC | pXMJ19 derivate, inserting cydC at MCS | This study |

| pXMJ-cydD | pXMJ19 derivate, inserting cydD at MCS | This study |

| pXMJ-nrdH | pXMJ19 derivate, inserting nrdH at MCS | This study |

| pXMJ-cg0964 | pXMJ19 derivate, inserting cg0964 at MCS | This study |

| pXMJ-trxB1 | pXMJ19 derivate, inserting trxB1 at MCS | This study |

| pXMJ-trxB | pXMJ19 derivate, inserting trxB at MCS | This study |

| pXMJ-trxC | pXMJ19 derivate, inserting trxC at MCS | This study |

| pkatA-GFP | pXMJ21 derivate, inserting PkatA before GFP | This study |

| pnrdH-GFP | pXMJ21 derivate, inserting PnrdH before GFP | This study |

| pXMJ-oxyR | pXMJ19 derivate, inserting oxyR at MCS | This study |

Polysulfides inhibition analysis

For the growth inhibition analysis, overnight cultures of C. glutamicum were incubated into fresh LBHIS medium containing different concentrations of polysulfides with an initial OD600 of 0.1. For agar plates analysis, the overnight C. glutamicum cells were washed and resuspended to OD600 = 1, then diluted and dripped in freshly prepared LBHIS agar plates containing 0 or 200 µM polysulfides for 24 h of cultivation. All C. glutamicum cells were cultivated at 30°C, and the cell growth was then measured during the cultivation process.

Intracellular H2O2 and ROS assay

For the H2O2 assay, C. glutamicum cells were cultivated in an LBHIS medium with different concentrations of polysulfides, harvested, and resuspended in acetone (final OD600 = 1). The tubes were sonicated for 15 min by using an ultrasonic crusher (Sonics VibraCell VCX-130) with an ice bath (20% effective power; 3 s work and 10 s interval). Then, the suspensions were centrifuged at 8000× g, 4°C for 10 min. Finally, the intracellular H2O2 levels of C. glutamicum were assayed by using a Hydrogen Peroxide (H2O2) content Assay Kit (Beijing Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd, China) according to the manufacturer’s instruction.

The intracellular ROS levels of C. glutamicum were analyzed by the fluorogenic probe 2’, 7’-dichlorofluorescein diacetate (DCFH-DA) as described previously (60, 61), with some modifications. Briefly, cells were collected and resuspended in phosphate buffered solution (PBS; pH 7.4) buffer. The suspensions (OD600 = 1) were preincubated with 10 µM DCFH-DA at 30°C for 20 min. The mixtures were incubated with 3 mM ferulic acid for another 30 min. Next, the cells were centrifuged and resuspended in PBS buffer for determination. Finally, the fluorescence was measured using a synergy neo2 multimode microplate reader (BioTek, VT, USA) with excitation and emission wavelengths of 502 and 521 nm, respectively.

Fluorescence assay

Two reporting plasmids (GFP driven by the promoters of PkatA and PnrdH, Fig. S5A) were created and transferred into strains C. glutamicum WT, oxyR deletion, oxyR complementation, OxyRC206S, OxyRC215S, and OxyRC206S-C215S. GFP intensity was measured using a microplate multi-mode Reader (BIOTEK, Cytation) with excitation at 488 nm and emission at 520 nm to quantify their function. Briefly, cells were incubated in LBHIS medium at 30°C, 220 rpm for overnight, and then samples were collected, washed twice with PBS (pH = 7.4; 8 g/L NaCl, 0.2 g/L KH2PO4, 2.9 g/L Na2HPO4 • 12H2O, and 0.2 g/L KCl) and resuspended in PBS buffer at OD600 of 10. The prepared cultures were inoculated to fresh LBHIS medium with 0, 200, and 400 µM polysulfides induction and maintained the final OD600 of 0.1. Finally, the fluorescence intensities and OD600 were detected after 8 h of induction.

Transcriptome analysis

C. glutamicum WT and oxyR deletion strains were prepared for transcriptome sequencing. Samples were cultivated in LHBIS medium with 200 µM polysulfides induction and collected at mid-log phase (OD600 = 1) for RNA extraction. RNA-seq library was constructed at Beijing Novogene Bioinformatics Technology Co., Ltd. Raw reads were filtered by removing reads containing adapters or poly-N and low-quality reads. The reference genome was obtained using C. glutamicum ATCC 13032 (https://www.genome.jp/dbget-bin/get_linkdb?-t+genes+gn:T00244), and fragments per kilobase per million mapped reads were used to quantify genes expression. The DESeq2 R package was used for RNA-seq differential expression analysis between two groups (2, 62). The Benjamini-Hochberg method was used to adjust the P-value with a false discovery rate of 5% for multiple testing to generate padj, and padj <0.05 and |log2 (Fold change)| >0 was set as the threshold for significant DEGs.

RT-qPCR analysis

RNA samples were prepared by using the RNAprep Pure Cell/Bacteria Kit (Tiangen Biotech, China) according to the manufacturer’s protocol. Total cDNA was synthesized using a FastKing RT Kit (Tiangen Biotech, China). The primers for RT-qPCR were synthesized by GENEWIZ (China) and listed in Table S1, and the samples were analyzed by using an ABI 7500 fast real-time PCR system (Applied Biosystems, USA) with SYBR Premix ExTaq (TaKaRa, China). The 16S rRNA gene was used as the control, and the 2− ΔΔCT method was performed to calculate the relative expression values (63).

Expression and purification of OxyR

The expression and purification of OxyR were carried out according to the previous protocol (64, 65). The E. coli BL21 (DE3) strain containing the expression plasmid pET21b-OxyR was cultivated at 37°C and 220 rpm in an LB medium. When OD600 reached at 0.6–0.8, 500 µM isopropyl-β-D-thiogalactopyranoside was added to induce the protein expression, and cells were further cultivated at 16°C, 220 rpm for 16 h. The cells were harvested by centrifugation at 4°C, 8,000 × g for 10 min and then resuspended in lysis buffer (20 mM Na2HPO4, 200 mM NaCl, and pH 7.5). Next, the resuspended culture was sonicated for 20 min by using an ultrasonic crusher (Sonics VibraCell VCX-130) in an ice bath and then centrifuged at 8,000× g, 4°C for 10 min. The collected supernatant was purified via the nickel-nitrilotriacetate column and eluted with elution buffer (20 mM Na2HPO4, 200 mM NaCl, 500 mM imidazole, and pH 7.5). Finally, the purified enzyme was condensed by using the Amicon Ultra 15 (Millipore, MA, 10 kDa, USA) and determined by SDS-PAGE.

Electrophoretic mobility shift assay

The probe for EMSA was prepared by PCR using C. glutamicum genomic DNA as the template, and a DNA fragment without the regulatory region was prepared as the negative control. The primers of each probe were listed in Table S1. The EMSA was performed as described previously (64). Briefly, the EMSA reaction mixtures (20 µL) were prepared as follows: 9 µL distilled deionized water (ddH2O), 1 µL 400 mM Tris-HCl (pH7.5), 1 µL 40 mM DTT, 2 µL 1 M KCl, 2 µL 50 mM MgCl2, 1 µL 10 mg/mL BSA, 2 µL 50% glycerol, 1 µL protein (0–5 μg), and 1 µL probe (50 ng). The system was then co-incubated (with or without 200 µM polysulfides) at 25°C for 30 min in the dark. Finally, the prepared reactions were electrophoresed in a 5% native polyacrylamide gel with 0.5 × Tris-borate-ethylenediaminetetraacetic acid buffer at 100 V for 50 min. Images were detected by a Tanon 5200 imaging system.

Batch fermentation

For batch fermentation, the engineered strains were carried out in 250 mL flasks. Cells were cultivated overnight in LBHIS medium and incubated in seed medium at a 5% vol ratio for 12 h of cultivation. Subsequently, the seed cultures were inoculated into 20 mL of fermentation medium, and the cultures were cultivated for 72 h at 30°C, 220 rpm. In addition, the main components of the seed medium contained 30 g/L glucose, 20 g/L corn steep liquor, 5 g/L (NH4)2SO4, 2 g/L urea, 0.5 g/L MgSO4, and 0.5 g/L KH2PO4. The main components of the fermentation medium contained 80 g/L glucose, 30 g/L corn steep liquor, 20 g/L (NH4)2SO4, 10 g/L Na2S2O3, 1 g/L KH2PO4, 0.5 g/L MgSO4, 0.01 g/L MnSO4, 0.01 g/L FeSO4, 1 mg/L vitamin B1, 0.2 mg/L biotin, and 20 g/L CaCO3.

Analytical methods

The cell growth was determined by the OD600 using an ultraviolet spectrophotometer (Xinmao Instrument, Shanghai, China). For the determination of H2S, samples were derivatized by mBBr and analyzed using the high-performance liquid chromatography (HPLC, Ultimate 3000) equipped with a fluorescence detector and C18 reverse phase column according to the previous method of Kimura et al. (66). The intracellular sulfane sulfur was measured using Sulfane sulfur probe 4 (SSP4) following the reported method (15). The concentration of L-cysteine was determined by using the standard method described previously (67).

Statistical analysis

Three independent biological replicates were used for each experiment, and the data were presented as the mean ± SE. Statistical analyses were performed with Student’s t-test. For all the data analyses, P ≤ 0.05 and P ≤ 0.01 were regarded as statistically significant and indicated by * and ** in the figures, respectively.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

This study was supported by the National Key Research and Development Program of China (Grants No. 2021YFC2100700), National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grants No. 32001671 and No. 31972061), and Tianjin Synthetic Biotechnology Innovation Capacity Improvement Project (Grants No. TSBICIP-KJGG-010).

Contributor Information

Jun Liu, Email: liu_jun@tib.cas.cn.

Haruyuki Atomi, Kyoto University, Kyoto, Japan .

DATA AVAILABILITY

All data sets generated for this study are included in the manuscript and/or the supplemental files. RNA-seq raw data are deposited into the NCBI SRA database under BioProject accession number PRJNA889357.

SUPPLEMENTAL MATERIAL

The following material is available online at https://doi.org/10.1128/aem.00904-23.

Supplemental material.

ASM does not own the copyrights to Supplemental Material that may be linked to, or accessed through, an article. The authors have granted ASM a non-exclusive, world-wide license to publish the Supplemental Material files. Please contact the corresponding author directly for reuse.

REFERENCES

- 1. Wendisch VF. 2020. Metabolic engineering advances and prospects for amino acid production. Metab Eng 58:17–34. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2019.03.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2. Wang J, Yang J, Shi G, Li W, Ju Y, Wei L, Liu J, Xu N. 2022. Transcriptome profiles of high-lysine adaptation reveal insights into osmotic stress response in Crynebacterium glutamicum. Front Bioeng Biotechnol 10:933325. doi: 10.3389/fbioe.2022.933325 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3. Wei L, Wang H, Xu N, Zhou W, Ju J, Liu J, Ma Y. 2019. Metabolic engineering of Corynebacterium glutamicum for L-cysteine production. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 103:1325–1338. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9547-7 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4. Takagi H, Ohtsu I. 2017. L-cysteine metabolism and fermentation in microorganisms. Adv Biochem Eng Biotechnol 159:129–151. doi: 10.1007/10_2016_29 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5. Liu H, Wang Y, Hou Y, Li Z. 2020. Fitness of chassis cells and metabolic pathways for L-cysteine overproduction in Escherichia Coli. J Agric Food Chem 68:14928–14937. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.0c06134 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Jones CM, Hernández Lozada NJ, Pfleger BF. 2015. Efflux systems in bacteria and their metabolic engineering applications. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 99:9381–9393. doi: 10.1007/s00253-015-6963-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Liu H, Hou Y, Wang Y, Li Z. 2020. Enhancement of sulfur conversion rate in the production of L-cysteine by engineered Escherichia coli. J Agric Food Chem 68:250–257. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.9b06330 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Liu H, Fang G, Wu H, Li Z, Ye Q. 2018. L-cysteine production in Escherichia coli based on rational metabolic engineering and modular strategy. Biotechnol J 13:e1700695. doi: 10.1002/biot.201700695 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9. Takumi K, Ziyatdinov MK, Samsonov V, Nonaka G. 2017. Fermentative production of cysteine by Pantoea ananatis. Appl Environ Microbiol 83:e02502-16. doi: 10.1128/AEM.02502-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10. Kondoh M, Hirasawa T. 2019. L-cysteine production by metabolically engineered Corynebacterium glutamicum. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 103:2609–2619. doi: 10.1007/s00253-019-09663-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11. Joo YC, Hyeon JE, Han SO. 2017. Metabolic design of Corynebacterium glutamicum for production of L-cysteine with consideration of sulfur-supplemented animal feed. J Agric Food Chem 65:4698–4707. doi: 10.1021/acs.jafc.7b01061 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Lu T, Cao Q, Pang X, Xia Y, Xun L, Liu H. 2020. Sulfane sulfur-activated actinorhodin production and sporulation is maintained by a natural gene circuit in Streptomyces coelicolor. Microb Biotechnol 13:1917–1932. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.13637 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Li K, Xin Y, Xuan G, Zhao R, Liu H, Xia Y, Xun L. 2019. Escherichia coli uses separate enzymes to produce H2S and reactive sulfane sulfur from L-cysteine. Front. Microbiol 10:298. doi: 10.3389/fmicb.2019.00298 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Ran M, Wang T, Shao M, Chen Z, Liu H, Xia Y, Xun L. 2019. Sensitive method for reliable quantification of sulfane sulfur in biological samples. Anal Chem 91:11981–11986. doi: 10.1021/acs.analchem.9b02875 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Liu H, Fan K, Li H, Wang Q, Yang Y, Li K, Xia Y, Xun L. 2019. Synthetic gene circuits enable Escherichia coli to use endogenous H2S as a signaling molecule for quorum sensing. ACS Synth Biol 8:2113–2120. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00210 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Xuan G, Lü C, Xu H, Chen Z, Li K, Liu H, Liu H, Xia Y, Xun L. 2020. Sulfane sulfur is an intrinsic signal activating MexR-regulated antibiotic resistance in Pseudomonas aeruginosa. Mol Microbiol 114:1038–1048. doi: 10.1111/mmi.14593 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Luebke JL, Shen J, Bruce KE, Kehl-Fie TE, Peng H, Skaar EP, Giedroc DP. 2014. The CsoR-like sulfurtransferase repressor (CstR) is a persulfide sensor in Staphylococcus aureus. Mol Microbiol 94:1343–1360. doi: 10.1111/mmi.12835 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Li H, Li J, Lü C, Xia Y, Xin Y, Liu H, Xun L, Liu H. 2017. FisR activates σ54-dependent transcription of sulfide-oxidizing genes in Cupriavidus pinatubonensis Jmp134. Mol Microbiol 105:373–384. doi: 10.1111/mmi.13725 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Lau N, Pluth MD. 2019. Reactive sulfur species (RSS): persulfides, polysulfides, potential, and problems. Curr Opin Chem Biol 49:1–8. doi: 10.1016/j.cbpa.2018.08.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Xin Y, Liu H, Cui F, Liu H, Xun L. 2016. Recombinant Escherichia coli with sulfide:quinone oxidoreductase and persulfide dioxygenase rapidly oxidises sulfide to sulfite and thiosulfate via a new pathway. Environ Microbiol 18:5123–5136. doi: 10.1111/1462-2920.13511 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Ida T, Sawa T, Ihara H, Tsuchiya Y, Watanabe Y, Kumagai Y, Suematsu M, Motohashi H, Fujii S, Matsunaga T, Yamamoto M, Ono K, Devarie-Baez NO, Xian M, Fukuto JM, Akaike T. 2014. Reactive cysteine persulfides and S-polythiolation regulate oxidative stress and redox signaling. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A 111:7606–7611. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1321232111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Nagahara N, Koike S, Nirasawa T, Kimura H, Ogasawara Y. 2018. Alternative pathway of H2S and polysulfides production from Sulfurated catalytic-cysteine of reaction intermediates of 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase. Biochem Biophys Res Commun 496:648–653. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.01.056 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Dóka É, Pader I, Bíró A, Johansson K, Cheng Q, Ballagó K, Prigge JR, Pastor-Flores D, Dick TP, Schmidt EE, Arnér ESJ, Nagy P. 2016. A novel persulfide detection method reveals protein persulfide- and polysulfide-reducing functions of thioredoxin and glutathione systems. Sci. Adv 2. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.1500968 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Wedmann R, Onderka C, Wei S, Szijártó IA, Miljkovic JL, Mitrovic A, Lange M, Savitsky S, Yadav PK, Torregrossa R, Harrer EG, Harrer T, Ishii I, Gollasch M, Wood ME, Galardon E, Xian M, Whiteman M, Banerjee R, Filipovic MR. 2016. Improved tag-switch method reveals that thioredoxin acts as depersulfidase and controls the intracellular levels of protein persulfidation. Chem Sci 7:3414–3426. doi: 10.1039/c5sc04818d [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25. Hou N, Yan Z, Fan K, Li H, Zhao R, Xia Y, Xun L, Liu H. 2019. OxyR senses sulfane sulfur and activates the genes for its removal in Escherichia coli. Redox Biol 26:101293. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2019.101293 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Christman MF, Morgan RW, Jacobson FS, Ames BN. 1985. Positive control of a regulon for defenses against oxidative stress and some heat-shock proteins in Salmonella typhimurium. Cell 41:753–762. doi: 10.1016/s0092-8674(85)80056-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Storz G, Tartaglia LA, Ames BN. 1990. Transcriptional regulator of oxidative stress-inducible genes direct activation by oxidation. Science 248:189–194. doi: 10.1126/science.2183352 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Tanner JR, Patel PG, Hellinga JR, Donald LJ, Jimenez C, LeBlanc JJ, Brassinga AKC. 2017. Legionella pneumophila OxyR is a redundant transcriptional regulator that contributes to expression control of the two-component CpxRA system. J Bacteriol 199:e00690-16. doi: 10.1128/JB.00690-16 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Milse J, Petri K, Rückert C, Kalinowski J. 2014. Transcriptional response of Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 to hydrogen peroxide stress and characterization of the OxyR regulon. J Biotechnol 190:40–54. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiotec.2014.07.452 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Cappelli EA, do Espírito Santo Cucinelli A, Simpson-Louredo L, Canellas MEF, Antunes CA, Burkovski A, da Silva JFR, Mattos-Guaraldi AL, Saliba AM, Dos Santos LS. 2022. Insights of OxyR role in mechanisms of host-pathogen interaction of Corynebacterium diphtheriae. Braz J Microbiol 53:583–594. doi: 10.1007/s42770-022-00710-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Teramoto H, Inui M, Yukawa H. 2013. Oxyr acts as a transcriptional repressor of hydrogen peroxide-inducible antioxidant genes in Corynebacterium glutamicum R. FEBS J 280:3298–3312. doi: 10.1111/febs.12312 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Kim JS, Holmes RK. 2012. Characterization of OxyR as a negative transcriptional regulator that represses catalase production in Corynebacterium diphtheriae. PLoS One 7:e31709. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0031709 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Pedre B, Young D, Charlier D, Mourenza A, Rosado LA, Marcos-Pascual L, Wahni K, Martens E, Belousov VV, Mateos LM, Messens J. 2018. Structural snapshots of OxyR reveal the peroxidatic mechanism of H2O2 sensing. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A:115–E11632. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1807954115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Kalinowski J, Bathe B, Bartels D, Bischoff N, Bott M, Burkovski A, Dusch N, Eggeling L, Eikmanns BJ, Gaigalat L, Goesmann A, Hartmann M, Huthmacher K, Krämer R, Linke B, McHardy AC, Meyer F, Möckel B, Pfefferle W, Pühler A, Rey DA, Rückert C, Rupp O, Sahm H, Wendisch VF, Wiegräbe I, Tauch A. 2003. The complete Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 genome sequence and its impact on the production of L-aspartate-derived amino acids and vitamins. J Biotechnol 104:5–25. doi: 10.1016/S0168-1656(03)00154-8 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35. Liu C, Zhang B, Liu YM, Yang KQ, Liu SJ. 2018. New intracellular shikimic acid biosensor for monitoring shikimate synthesis in Corynebacterium glutamicum. ACS Synth Biol 7:591–601. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.7b00339 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36. Ko YS, Kim JW, Lee JA, Han T, Kim GB, Park JE, Lee SY. 2020. Tools and strategies of systems metabolic engineering for the development of microbial cell factories for chemical production. Chem Soc Rev 49:4615–4636. doi: 10.1039/d0cs00155d [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37. Mukhopadhyay A. 2015. Tolerance engineering in bacteria for the production of advanced biofuels and chemicals. Trends Microbiol 23:498–508. doi: 10.1016/j.tim.2015.04.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38. Liu H, Qi Y, Zhou P, Ye C, Gao C, Chen X, Liu L. 2021. Microbial physiological engineering increases the efficiency of microbial cell factories. Crit Rev Biotechnol 41:339–354. doi: 10.1080/07388551.2020.1856770 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39. Mohedano MT, Konzock O, Chen Y. 2022. Strategies to increase tolerance and robustness of industrial microorganisms. Synth Syst Biotechnol 7:533–540. doi: 10.1016/j.synbio.2021.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40. Imlay JA. 2008. Cellular defenses against superoxide and hydrogen peroxide. Annu Rev Biochem 77:755–776. doi: 10.1146/annurev.biochem.77.061606.161055 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41. Chiang SM, Schellhorn HE. 2012. Regulators of oxidative stress response genes in Escherichia coli and their functional conservation in bacteria. Arch Biochem Biophys 525:161–169. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2012.02.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42. DeLeon ER, Gao Y, Huang E, Arif M, Arora N, Divietro A, Patel S, Olson KR. 2016. A case of mistaken identity: are reactive oxygen species actually reactive sulfide species Am J Physiol Regul Integr Comp Physiol 310:R549–60. doi: 10.1152/ajpregu.00455.2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43. Wang T, Ran M, Li X, Liu Y, Xin Y, Liu H, Liu H, Xia Y, Xun L, Bose A. 2022. The pathway of sulfide oxidation to octasulfur globules in the cytoplasm of aerobic bacteria. Appl Environ Microbiol 88. doi: 10.1128/aem.01941-21 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44. Olson KR, Gao Y, DeLeon ER, Arif M, Arif F, Arora N, Straub KD. 2017. Catalase as a sulfide-sulfur oxido-reductase: an ancient (and modern?) regulator of reactive sulfur species (RSS). Redox Biol 12:325–339. doi: 10.1016/j.redox.2017.02.021 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45. Champion CJ, Xu J. 2017. The impact of metagenomic interplay on the mosquito redox homeostasis. Free Radic Biol Med 105:79–85. doi: 10.1016/j.freeradbiomed.2016.11.031 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46. Salehi SS, Mirmiranpour H, Rabizadeh S, Esteghamati A, Tomasello G, Alibakhshi A, Najafi N, Rajab A, Nakhjavani M. 2021. Improvement in redox homeostasis after cytoreductive surgery in colorectal adenocarcinoma. Oxid Med Cell Longev 2021:8864905. doi: 10.1155/2021/8864905 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47. Bhattacharyya A, Chattopadhyay R, Mitra S, Crowe SE. 2014. Oxidative stress: an essential factor in the pathogenesis of gastrointestinal mucosal diseases. Physiol Rev 94:329–354. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00040.2012 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48. Rückert C, Koch DJ, Rey DA, Albersmeier A, Mormann S, Pühler A, Kalinowski J. 2005. Functional genomics and expression analysis of the Corynebacterium glutamicum fpr2-cysIXHDNYZ gene cluster involved in assimilatory sulphate reduction. BMC Genomics 6:121. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-6-121 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49. Rückert C, Milse J, Albersmeier A, Koch DJ, Pühler A, Kalinowski J. 2008. The dual transcriptional regulator CysR in Corynebacterium glutamicum ATCC 13032 controls a subset of genes of the McbR regulon in response to the availability of sulphide acceptor molecules. BMC Genomics 9:483. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-9-483 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50. Yang HD, Jeong H, Kim Y, Lee HS. 2022. The cysS gene (ncgl0127) of Corynebacterium glutamicum is required for sulfur assimilation and affects oxidative stress-responsive cysteine import. Res Microbiol 173:103983. doi: 10.1016/j.resmic.2022.103983 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51. Kawano Y, Suzuki K, Ohtsu I. 2018. Current understanding of sulfur assimilation metabolism to biosynthesize L-cysteine and recent progress of its fermentative overproduction in microorganisms. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 102:8203–8211. doi: 10.1007/s00253-018-9246-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52. Kawano Y, Onishi F, Shiroyama M, Miura M, Tanaka N, Oshiro S, Nonaka G, Nakanishi T, Ohtsu I. 2017. Improved fermentative L-cysteine overproduction by enhancing a newly identified thiosulfate assimilation pathway in Escherichia coli. Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 101:6879–6889. doi: 10.1007/s00253-017-8420-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53. Zhang Y, Wei M, Zhao G, Zhang W, Li Y, Lin B, Li Y, Xu Q, Chen N, Zhang C. 2021. High-level production of L-homoserine using a non-induced, non-auxotrophic Escherichia coli chassis through metabolic engineering. Bioresource Technology 327:124814. doi: 10.1016/j.biortech.2021.124814 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54. Liu Y, Yasawong M, Yu B. 2021. Metabolic engineering of Escherichia coli for biosynthesis of beta-nicotinamide mononucleotide from nicotinamide. Microb Biotechnol 14:2581–2591. doi: 10.1111/1751-7915.13901 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55. Wiriyathanawudhiwong N, Ohtsu I, Li ZD, Mori H, Takagi H. 2009. The outer membrane TolC is involved in cysteine tolerance and overproduction in Escherichia coli . Appl Microbiol Biotechnol 81:903–913. doi: 10.1007/s00253-008-1686-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56. Kawano Y, Ohtsu I, Takumi K, Tamakoshi A, Nonaka G, Funahashi E, Ihara M, Takagi H. 2015. Enhancement of L-cysteine production by disruption of yciW in Escherichia coli. J Biosci Bioeng 119:176–179. doi: 10.1016/j.jbiosc.2014.07.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57. Kishino M, Kondoh M, Hirasawa T. 2019. Enhanced L-cysteine production by overexpressing potential L-cysteine exporter genes in an L-cysteine-producing recombinant strain of Corynebacterium glutamicum Biosci Biotechnol Biochem 83:2390–2393. doi: 10.1080/09168451.2019.1659715 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58. Li L, Zhao Y, Ruan L, Yang S, Ge M, Jiang W, Lu Y. 2015. A stepwise increase in pristinamycin II biosynthesis by Streptomyces pristinaespiralis through combinatorial metabolic engineering. Metab Eng 29:12–25. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2015.02.001 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 59. Okibe N, Suzuki N, Inui M, Yukawa H. 2011. Efficient Markerless gene replacement in Corynebacterium glutamicum using a new temperature-sensitive plasmid. J Microbiol Methods 85:155–163. doi: 10.1016/j.mimet.2011.02.012 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60. Chen C, Pan J, Yang X, Xiao H, Zhang Y, Si M, Shen X, Wang Y. 2017. Global transcriptomic analysis of the response of Corynebacterium glutamicum to ferulic acid. Arch Microbiol 199:325–334. doi: 10.1007/s00203-016-1306-5 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61. Si M, Wang J, Xiao X, Guan J, Zhang Y, Ding W, Chaudhry MT, Wang Y, Shen X. 2015. Ohr protects Corynebacterium glutamicum against organic hydroperoxide induced oxidative stress. PLoS One 10:e0131634. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0131634 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62. Love MI, Huber W, Anders S. 2014. Moderated estimation of fold change and dispersion for RNA-Seq data with DESeq2. Genome Biol 15:550. doi: 10.1186/s13059-014-0550-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63. Du H, Liao X, Gao Z, Li Y, Lei Y, Chen W, Chen L, Fan X, Zhang K, Chen S, Ma Y, Meng C, Li D, Cann I. 2019. Effects of methanol on carotenoids as well as biomass and fatty acid biosynthesis in Schizochytrium limacinum B4D1 . Appl Environ Microbiol 85. doi: 10.1128/AEM.01243-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64. Gao J, Du M, Zhao J, Xu N, Du H, Ju J, Wei L, Liu J. 2022. Design of a genetically encoded biosensor to establish a high-throughput screening platform for L-cysteine overproduction. Metab Eng 73:144–157. doi: 10.1016/j.ymben.2022.07.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65. Wei L, Wang Q, Xu N, Cheng J, Zhou W, Han G, Jiang H, Liu J, Ma Y. 2019. Combining protein and metabolic engineering strategies for high-level production of O -Acetylhomoserine in Escherichia coli . ACS Synth. Biol 8:1153–1167. doi: 10.1021/acssynbio.9b00042 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66. Kimura Y, Toyofuku Y, Koike S, Shibuya N, Nagahara N, Lefer D, Ogasawara Y, Kimura H. 2015. Identification of H2S3 and H2S produced by 3-mercaptopyruvate sulfurtransferase in the brain. Sci Rep 5:14774. doi: 10.1038/srep14774 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67. Gaitonde MK. 1967. A spectrophotometric method for the direct determination of cysteine in the presence of other naturally occurring amino acids. Biochem J 104:627–633. doi: 10.1042/bj1040627 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplemental material.

Data Availability Statement

All data sets generated for this study are included in the manuscript and/or the supplemental files. RNA-seq raw data are deposited into the NCBI SRA database under BioProject accession number PRJNA889357.