Abstract

The past four decades have seen a steady rise of references to ‘security’ by health academics, policy-makers and practitioners, particularly in relation to threats posed by infectious disease pandemics. Yet, despite an increasingly dominant health security discourse, the many different ways in which health and security issues and actors intersect have remained largely unassessed and unpacked in current critical global health scholarship. This paper discusses the emerging and growing health-security nexus in the wake of COVID-19 and the international focus on global health security. In recognising the contested and fluid concept of health security, this paper presents two contrasting approaches to health security: neocolonial health security and universal health security. Building from this analysis, we present a novel heuristic that delineates the multiple intersections and entanglements between health and security actors and agendas to broaden our conceptualisation of global health security configurations and practices and to highlight the potential for harmful unintended consequences, the erosion of global health norms and values, and the risk of health actors being co-opted by the security sector.

Keywords: public health, health policy

SUMMARY BOX.

Dominant understandings of health security have traditionally focused on the threat of infectious disease outbreaks with overconsideration to the security of populations and economic systems in high-income states.

COVID-19 has once again exposed global inequities in health security practices as has served as a catalyst for readdressing understandings of health and security in the wake of the pandemic.

Critical analyses of perspectives of health and security have remained scant in global health scholarship, despite ubiquity of the term health security.

By addressing the contested and fluid concept of health security, this paper conceptualises two contrasting approaches to global health security and their impacts on global health security systems and outcomes.

We present a novel heuristic framework for describing the different entanglements of health and security agendas and actors and how these present both threats and opportunities for better and fairer global health security.

In the wake of COVID-19 and with calls to collectively restructure the global health security agenda and apparatus, sustained critical research is needed to align health security practices towards equitable, inclusive and decolonial approaches in global health.

Introduction

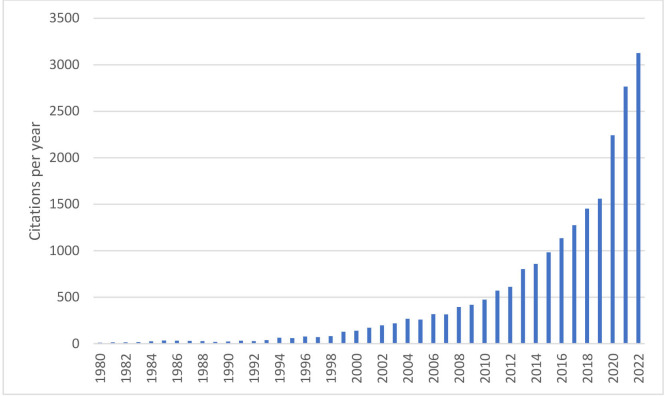

The past four decades have seen a rise in the frequency of references to ‘security’ by health academics. The number of publications in the PubMed database that mention both ‘health’ and ‘security’ in the title or abstract has risen exponentially between 1980 and 2022 (figure 1). This is consistent with a growing tendency in policy circles and the general media to frame various health problems as security threats. Infectious diseases have dominated health security discourses with HIV/AIDS,1 H1N1 ‘swine influenza’,2 polio,3 Ebola,4 Zika5 and most recently, COVID-19,6 all presented as threats to international security and stability.7

Figure 1.

Line graph of the number of publications mentioning ‘health’ and ‘security’ in the title or abstract, 1980–2022.

This paper discusses the growing importance and place of ‘security’ in global health and considers the implications.8 It sets out to question the assumption that using a security lens to discuss health challenges brings net benefits to the health sector because of the increased policy attention, financing and allocation of other resources.9 10 We first provide an overview of the expanding discourses of the past four decades which have presented public health challenges as national and global security threats. We then discuss the origins and definition of health security as a contested and fluid concept and note other ways by which health and security concerns intersect and are operationalised towards different ends.

In doing so, we highlight how processes and understandings of health security are politically constructed and heavily contingent on the type of health challenge that is framed as a security threat, who does the framing and what motivations are associated with the framing of these threats. We also discuss contrasting forms of health security, noting tensions between the aims and outcomes of alternative health security perspectives with paradigms. Building from this analysis, we present a heuristic framework for describing, monitoring and evaluating the growing and varied entanglements of health and security agendas and actors. We argue that this framework can help describe and analyse how certain forms of association between health and security can produce negative health effects and outcomes that should be avoided in preparedness and response activities for ongoing and future health emergencies and global health practices.

The rise of a global health security agenda

Although security measures to protect communities and populations from the spread of infectious disease date back thousands of years, we trace the current framing and rationalisation of global health security back to the late 1980s. Then, infectious disease experts and journalists began writing about a dangerous future of deadly pandemics with dire scenarios due to rising levels of international travel and trade, the growth of mega-cities with enormous populations living in crowded and insanitary conditions, and increased opportunities for zoonotic disease transmission due to encroachment on new habitats and industrial scale factory farming.11 12

In the USA, national security actors took note and called for stronger disease control capacity, more biomedical research and the incorporation of institutions from the life sciences and public health into the national security establishment. A report published in 1992 by the Institute of Medicine, Emerging Infections: Microbial Threats to Health in the USA referred to HIV/AIDS, mutating influenza strains, haemorrhagic fevers (such as Ebola and Lassa fevers), and the reintroduction of cholera into the Western Hemisphere as grave national and international security challenges. Using explicitly militaristic language, the report presented drugs, vaccines and pesticides as ‘weapons’ in a battle against infectious diseases.13

Part of the fear of infectious diseases lay in the recognition that a deadly epidemic could disrupt global supply and value chains and pose an economic threat to countries and populations that were relatively unaffected by the disease itself. Thus, when some scholars predicted that HIV/AIDS could destabilise societies in Africa by the end of the 20th century,14,15 the US State Department identified the disease as a security threat.16 This led to the US establishing PEPFAR, enabling the creation of the Global Fund to Fight AIDS, TB and Malaria, and supporting a UN Security Council Resolution in 2000 to wage a war against HIV/AIDS,17 making it the first disease to be recognised by the Security Council as a threat to international security.18

The SARS (2003), H5N1 avian influenza (2005) and H1N1 swine influenza (2009) outbreaks and pandemic, accompanied by a steady flow of stories about apocalyptic future scenarios in the media and popular culture, further elevated infectious diseases as international security threats, a trend also encouraged by transnational corporations concerned about the potential disruption of global supply chains and revenue streams.19

In parallel, growing anxieties surrounding terrorism also brought security and health actors together around the need to strengthen the ability of health systems to respond to sudden, unpredictable and fabricated public health emergencies.20,21 Incidents such as the 1995 sarin gas attack on the Tokyo subway and the mailing of anthrax spores to members of the US Congress in 2001 solidified the importance of health protection capabilities as a national security measure in the minds of politicians and public.

Inevitably, the transnational and highly networked nature of these threats has resulted in health protection becoming a priority for intergovernmental organisations. A High-Level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change convened by the UN Secretary General in 2004 signalled a turning point for global health because it considered acts of bioterrorism and naturally occurring outbreaks from the same security perspective and called for improvements in health protection capabilities globally.22

Consequently, the scope of the International Health Regulations (IHRs) was substantially revised in 2005 to extend its remit to cover the intentional release of biological, chemical and radiological agents, in addition to naturally occurring disease outbreaks. The hand of WHO was also strengthened by giving the director general the authority to declare a Public Health Emergency of International Concern (PHEIC) whenever the international spread of an infectious disease is deemed ‘serious, unusual or unexpected’ and requiring ‘immediate international action’.23 Although the WHO can only issue states with non-binding recommendations, the revised IHRs have institutionalised some legal obligations on states to improve infectious disease surveillance and control capacity and accept external intervention when the international world order is believed to be under threat.24,25

Because progress in achieving an effective global health security regimen through the mechanisms and stipulations of the IHR has been slow, some countries, and the USA in particular, have established alternative initiatives including the Global Health Security Agenda (GHSA) which was launched in 2014 to monitor and hasten the strengthening of a global health security infrastructure, and bring the World Organisation for Animal Health, the Food and Agriculture Organisation, Interpol and the UN Office for Disaster Risk Reduction into the ambit of global health security.

The emergence of the GHSA coincided with the 2014/2015 West African Ebola epidemic which marked another key chapter in the framing of a disease as a foreign policy issue and international security concern.26 Not only did Ebola become the second disease to be declared a threat to international peace and security by the Security Council (on the grounds that it risked reversing prior peacebuilding and development gains in the affected countries),27 it also resulted in the first-ever UN emergency health mission: the UN Mission for Ebola Emergency Response (UNMEER).28 The Zika virus epidemic coinciding with the Olympics in Brazil in 2016 produced another episode where ‘global health security’ hit the front pages of mainstream newspapers as constituting a collective security risk to humanity.29

COVID-19 represents the latest critical juncture in the evolution of the health-security nexus. To legitimise the measures implemented to contain the outbreak, many states adopted a martial rhetoric positing COVID-19 as a high-level threat while implementing unprecedented surveillance and mobility restrictions,30 sometimes in ways that were undemocratic (or perceived as such), or an overextension of governmental powers. As Gibson-Fall31 has argued, COVID-19 has come to represent a pivotal moment in global health security practices, whereby militaries have featured as key responding actors, ranging from setting up field hospitals in Serbia, Russia or France, to delivering protective equipment or enforcing lockdowns in South Africa, Spain or Italy. Elsewhere, Luscombe and McClelland have drawn critical attention to the elevated role of law enforcement agencies during COVID-19 and warned of the extraordinary expansions of police power and the unequal patterns of enforcement which they have produced.32

It is worth noting also that many other issues have been securitised in efforts to integrate public health as a component of international and national security agendas. The securitisation of the ‘refugee crisis’,33 for instance, is an example of the expanding range of ‘hot issues’ considered under the health security umbrella, by framing unregulated flows of people as a threat to local health systems. Antimicrobial resistance34 has also contributed to elevating global health as a pressing international priority and was one of the main topics at the G20 meeting in Hamburg in 2017 following which there have also been calls for the UN Security Council to play a stronger role in policing national obligations towards global health security, and having the mandate to impose trade sanctions on countries that fail to improve their health protection capacity.35

Elsewhere, even the rising cost of treating chronic diseases,36 obesity37 and the current opioid crisis in the USA38 have been identified as either national or international security challenges, contributing to an expansion of the range of public health challenges incorporated into the language and perspective of security. Though some scholars argue that global health has been oversecuritised, what is clear is that the past four decades have seen a deepening and broadening of concern attached to certain health threats (largely infectious disease outbreaks) by both health and security actors, that have connected health and security practices to each other, and turned ‘health security’ into the dominant narrative within global health over the past four decades.8

Unpacking health security

Despite its frequent use, the term health security remains fluid and contested. For example, Moodie and D’Alessandra39 note that there is ‘no agreement on the definition of ‘security’ let alone how this term should be applied in a health context’, while Davies draws attention to conceptual inconsistencies ‘between an impulse to elevate health by portraying aspects of it as security concerns equivalent to nuclear proliferation or terrorism, and a realisation that security may not be a useful language for describing and institutionalising effective responses to health problems’.40

Here, we present two alternative conceptualisations of health security as a way to contrast different approaches to health security and key tensions that lie between them. For brevity, we label these contrasting approaches neocolonial health security and universal health security. The former describes an approach to health security that privileges the well-being and interests of the wealthy and healthy, while typically identifying poor countries and populations as the threat source, usually via the vector of naturally occurring disease outbreaks.41,42 Arguably, this is the dominant contemporary form of global health security and is observable in a comment by the UN High-Level Panel on Threats, Challenges and Change on how affluent states ‘can be held hostage to the ability of the poorest State to contain an emerging disease.’22

An important feature of neocolonial health security is its focus on preventing or mitigating future or potential threats, especially by improving communicable disease surveillance and increasing investments in research and development for new biosecurity technologies including diagnostics, vaccines and medicines.43–45 Indeed, an emphasis on biomedical interventions and technological solutions is a feature of neocolonial health security and is often accompanied by a neglect of the social interventions required to reduce the heightened vulnerability of poorer and more marginalised communities.46,47

In contrast, universal health security represents an approach to health security that is inclusive of the needs of all people, and which accommodates a broader range of threats to health. Crucially, it accommodates the threats to health endured by those already living in insecure conditions and emphasises poverty, hunger, poor access to healthcare and human rights abuses as current health threats. By being concerned with the underlying causes of ill health, universal health security is also more likely to pose disease as an outcome of insecurity than as a threat to security. This approach echoes the concept of ‘human security’ promoted by the UNDP in the 1990s to counter the dominant state-centric discourse of national security and focus instead on the protection of human life and dignity.48,49

A key distinction between these alternative conceptualisations of health security is that they prioritise different segments of global society. Neocolonial health security privileges the security of wealthier populations and countries and aims to manage, isolate and contain the consequences of poverty, while universal health security emphasises the social and health needs of low-income populations in under-resourced settings and sees this as fundamental to eradicating the root causes of health insecurity. Dominant global health security discourses tend to gloss over these contrasting conceptualisations by presenting health security as a global good that benefits all peoples and countries,50 or by arguing that even if global health security arrangements privilege wealthy countries and populations, there will be some trickle-down benefits to low-income states and populations. However, the rhetoric of a common global security agenda has often failed to be matched by the practice of global health security.

For example, when the West African Ebola outbreak prompted the declaration of a PHEIC, vast amounts of funding and effort were directed at preventing entry of the disease into Northern and Western countries, while the affected populations in West Africa were faced with inadequately resourced health systems and draconian lockdown measures, including punishment for non-compliance.51 Others noted also how biomedicalised and technological approaches during the outbreak came at the expense of more holistic understandings of health challenges.52 Indeed, although the West African Ebola outbreak killed over 11 000 people, these figures pale in comparison to the hundreds of thousands premature deaths every year due to malaria, diarrhoeal disease, and undernutrition which have been largely neglected due to their location and prevalence in low-income countries.53,54

The H5N1 virus-sharing dispute between WHO and Indonesia in 2007 is another case in point. The declaration of viral sovereignty by the Indonesian Health Minister can be viewed as an act of resistance against a global health security regime that expects developing countries to participate in a global viral surveillance system without benefiting from the ensuing development of vaccines and other medical technologies that would protect populations from any future influenza epidemic.55,56 Finally, neocolonial health security responses were evident with COVID-19, most glaringly in the vaccine hoarding and vaccine nationalism by high-income states,57,58 in the refusal to waive intellectual property rights for COVID-19 tools and resources by private corporations,59 and in the biosecurity-centric responses to the pandemic that exacerbated individual and communal vulnerabilities associated with poverty and other pre-existing socioeconomic insecurities.60,61

Beyond ‘health security’: deconstructing the health-security nexus

In general, dominant practices of health security assume a convergence between the objectives of the security and health sectors, and that cooperation between security and health actors is a means to their achievement. By security actors, we mean government agencies responsible for national security (eg, the executive branch of government, the military, the police and intelligence agencies); multilateral institutions like the UN Security Council, the G7 and NATO; as well as influential private corporations and military-industrial complexes which operate and drive interests and investments within the security sector.

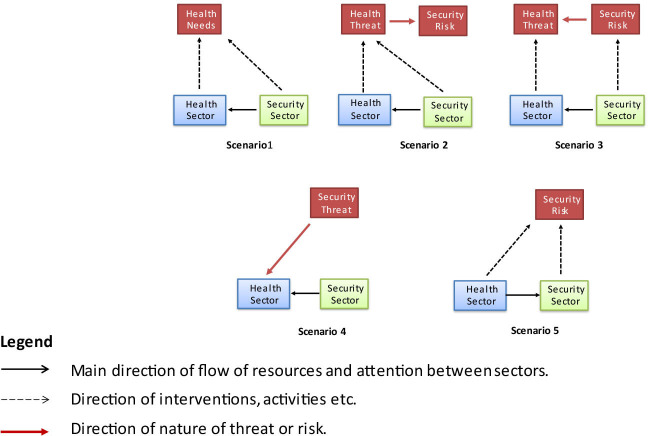

However, security actors may interact with the health sector in several ways, including in ways that produce tensions between security concerns and objectives, and those of the health sector. In this section, we describe how health and security issues may overlap and interact in different ways within a multidimensional security-health nexus. Figure 2 presents this multidimensionality in the form of five scenarios in which health sector and security actors interact with varying purposes and implications for health, security and affected populations.

Figure 2.

Scenarios in which health and security sectors interact.

The first scenario is one where the health sector receives assistance from the security sector in responding to health needs that do not constitute a security threat or risk. Despite there being no intersecting security agenda or explicit construction of a security threat, security sector actors are deployed to assist health sector actors, for example, by offering military medical services for civilian patients or providing logistical support to the health sector. This is often seen in humanitarian emergency settings, but there are also instances of security sector actors providing non-urgent support to non-military healthcare programmes such as mass immunisation campaigns. Contributions made by the security sector to the health sector may also come in the form of research and knowledge generated from military experiences as evidenced by a long history of military health scientists and practitioners having been at the forefront of key advances in public health since the 18th century.62

The second scenario is the one which dominates current discussions about global health security and is where the security sector is mobilised and deployed to address a health problem that is also deemed to be a security threat.63 In this scenario, security sector actors may enhance the authority of health actors to address the perceived health threat or may themselves be given enhanced or extraordinary powers and/or resources to help contain and mitigate health emergencies,64 as seen most vividly in response to the 2014/15 EVD outbreak in West Africa and COVID-19. In the case of both, national security agencies were central to the enforcement of lockdown, social distancing and restricted travel measures within and between countries. In the case of the 2014 Ebola outbreak, there were also striking examples of international security mobilisation with the establishment of the UN Security Council mission (UNMEER) and the deployment of troops from the USA, the UK and France in Liberia, Sierra Leone and Guinea, respectively.65–67

The third scenario, like the second, involves an overlap between a health threat and security threat except that in this case, the security threat is the source of a health threat rather than vice versa. Threats or acts of war and terrorism have intensified levels of engagement between security sector actors and the health sector, usually to ensure that health systems and populations are optimally prepared to respond to and mitigate the intentional release of biological and chemical agents.

In the fourth scenario, increased engagement between health and security actors occurs when the health sector is under attack68 and has to rely on security sector actors for protection. Examples of this include the need for health workers to have the protection and security of police officers in order to conduct immunisations in parts of Pakistan where healthcare staff and police officers have been killed or injured by armed groups and insurgents.69 This scenario is also observed in the need for health workers to be protected in active conflict-zones including Afghanistan, Syria and Yemen following deliberate and targeted attacks on health facilities and health workers.70–72

The fifth scenario involves security sector actors mobilising the health sector to perform a security function in a situation where there is no health threat. This includes examples of health actors being asked or co-opted to perform surveillance or intelligence gathering activities, sometimes in violation of ethical, legal and normative standards concerning confidentiality, trust, impartiality and neutrality. In this scenario, health sector resources are used to expand the capacity of the security sector, unlike the first four scenarios where the security sector typically extends the capacity of the health sector either directly or indirectly by generating financial or political support for the health sector.

While these five scenarios represent different ways in which health and security agendas and actors may interact, they need also to be considered in relation to two cross-cutting tensions. First, is the tension between national and international or global forces and approaches to security. Historically, security concerns have tended to be shaped by national actors and perspectives and are reflected in the dominant neocolonial approach to health security despite recognition of the borderless threats of infectious diseases, nuclear war and global warming and the increasing need for collective or global security. Incompatibilities or trade-offs between national and global security become more acute in the context of rising tensions and conflict between and within nation states, producing more entanglements in the form of scenarios 3, 4 and 5 as national security threats and agendas take priority over global health threats and agendas. In this regard, health actors may have an important role in actively promoting expansive and collective visions of global security over more parochial and partial visions of national security.

The second cross-cutting tension is that between public interest actors and private commercial actors, a tension that exists within both the security and health sectors. Powerful corporations have a vested interest in shaping the way that health and security threats are defined, framed and perceived, and in influencing the subsequent policy response in both sectors. In the health sector, both ‘Big Pharma’ and ‘Big Tech’ are influential actors given their control over the production of biosecurity technologies and the increasing use and dependence on digital surveillance systems for responses to both infections disease threats and the perceived security threats posed by cross-border migration.73 Across all five scenarios, there is therefore a need to interrogate the involvement and impact of corporate actors within the health-security nexus and the tension between private commercial interests and the wider public interest. It is also important to note the influence of powerful private foundations that espouse market-led and privatised approaches to global health and development. Often labelled ‘new philanthropy’ or ‘philanthrocapitalism’,74 such approaches strongly emphasise proprietary technological and biomedical solutions that not only serve commercial interests but also reinforce neocolonial approaches to health security.75

Consequences and implications for the health sector

The increasingly entangled health-security nexus, globally and nationally, has been encouraged by health actors because some health threats are correctly seen as needing the involvement of security actors and because the elevation of health to the ‘high politics’ of governments offers the hope of additional resources being made available for the health sector. However, health and security actors may also interact in ways that could undermine health objectives, agendas and interests. This could occur in three ways: first, in ways that are unintended; second, through an erosion of health sector norms, values and approaches; and third through health actors being co-opted into serving security sector agendas and interests in ways that may be malign or inappropriate.

Examples of unintended consequences include security actors unintentionally undermining health programmes or delivery through being inadequately equipped or skilled, or by inadvertently creating excessive fear or panic,76 or provoking civilian resistance to public health measures. For example, the use of the police and armed forces to impose quarantine measures during the 2014 Ebola Virus Disease (EVD) outbreak in West Africa resulted in protest and acts of civil disobedience due to a lack of trust in the police and army, influenced in part by a violent history of armed conflict. This in turn led to an even more heavy-handed security sector response, making it harder to contain the very threat that security sector actors had been deployed to mitigate.77 The association of polio vaccinators with the police and army in northern Pakistan that led to a belief that vaccination campaigns were a cover for spying by the Pakistani and the US governments is another example of security sector involvement in health having a negative impact.78

Neocolonial approaches to global health security that stress security sector norms and values around maintaining order and preserving state control through coercive force may also undermine public health values and approaches that place greater emphasis on equity, human rights and participatory approaches to health improvement. Indeed, the draconian and at times violent imposition of lockdown measures by armed forces and police during COVID-19 led UN Secretary Antonio Guterres to warn of a ‘pandemic of human rights abuses.79 Claims that security forces are necessary or indispensable to responses to outbreaks and public health emergencies should be interrogated carefully for these reasons, especially if it leads to civilian and public health agencies being undermined in the process.80

The configurations represented in scenario 3 can also result in unintended harms and the erosion of public health values. For example, the rise of concerns over bioterrorism has added to public health arguments in favour of expanded surveillance technologies that threaten rights to privacy and trust in public health authorities. The harvesting of personal data through multiple digital platforms, including those specifically designed for medical or public health purposes, poses profound challenges to the preservation of not just privacy, but also liberty and autonomy. A further concern about expanded surveillance and personal data capture systems, is the heavy involvement of powerful ‘Big Tech’ companies seeking to expand their own markets and control and use of data for commercial manipulation and exploitation.81,82

The growing influence and involvement of security sector actors in global health may also reinforce neocolonial approaches to global health security at the expense of those that place a greater premium on equity and global solidarity. For example, the imposition of trade and travel restrictions on West Africa during the Ebola crisis to prevent the spread of the virus to the Global North also hindered the flow of health workers and medical supplies to the worst-affected areas of the outbreak. Similarly the knee-jerk imposition of travel bans on countries in southern Africa by Northern and Western countries following South Africa’s identification of the Omicron variant in 2021 and its sharing of data with the international community was widely condemned for undermining the very kind of international trust and cooperation needed to control the spread of new COVID-19 variants or future dangerous pathogens.83

Finally, the increasing entanglement of health and security actors and agendas may undermine health if it leads to health actors and programmes being co-opted by the security sector for inappropriate or malign purposes. Past examples include the use of health actors to gather intelligence for questionable reasons such as in USAID-sponsored HIV projects being used as a cover for covert foreign policy operations in Cuba,84 the deployment of polio eradication initiatives to gather intelligence on militant groups in northwest Pakistan,78 and the obligation placed on healthcare professionals in the UK to identify and report ‘potential’ extremists or terrorists on the basis of criteria and practices that have been deemed both ineffective and racist.85

Conclusions

Present systems of global health security are mired by tensions between competing and conflicting perspectives on the nature of and response to public health crises, and the ways in which these perspectives intersect and interact with perceived security threats. In tracing the genealogy of the GHSA over the past four decades, we describe how the health and security nexus has mostly been framed by security-first logics that have ascribed greater weight to the interests of high-income countries and global supply chains rather than to individual human security, or populations in low-income and-middle-income countries. Furthermore, we note the tendency to adopt measures that reflect, replicate and entrench power asymmetries.

While acknowledging the still fluid and contested concept of health security, we have presented two contrasting conceptualisations of health security: neocolonial health security and universal health security. Building from the distinctions between these two approaches to health security, we have presented a novel, heuristic framework of five scenarios for describing the growing and varied entanglements between health and security agendas and actors, each with a range of implications for the health sector including unintended operational harms, the erosion of public health norms, values and objectives and in the inappropriate or malign co-option of health actors.

Finally, we highlight concerns about the potential for a ‘security industrial complex’ to establish global and national public health regimes rooted in biotechnological, neocolonial and coercive and authoritarian approaches to health security that would threaten human rights and negate efforts to alleviate poverty, inequality and other structural drivers of human insecurity. The risk of the multibillion dollar global and national health security budgets to be driven by the interests of powerful corporate actors should also provoke stronger calls for detailed financial reporting and political economy analyses of developments taking place through the pandemic fund, pandemic treaty and medical countermeasures platform, among other things.

It is vital that a more critical approach is applied to the use of health security discourses and that this is combined with an ongoing monitoring and evaluation of the evolving and deepening health security, and restructuring of the GHSA.86

Footnotes

Handling editor: Seye Abimbola

Twitter: @dcmccoy11, @J_J_Kennedy

Contributors: DM initiated and led the writing of the paper. SR, SD and JK reviewed drafts and contributed to the intellectual content and writing of the paper.

Funding: The authors have not declared a specific grant for this research from any funding agency in the public, commercial or not-for-profit sectors.

Competing interests: None declared.

Provenance and peer review: Not commissioned; externally peer reviewed.

Data availability statement

No data are available.

Ethics statements

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

References

- 1.Elbe S. Should HIV/AIDS be Securitized? the ethical dilemmas of linking HIV/AIDS and security. Int Studies Q 2006;50:119–44. 10.1111/j.1468-2478.2006.00395.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Ingram A. Swine flu calls into question the meaning of global health security. E-International Relations 2009. Available: https://www.e-ir.info/2009/04/29/swine-flu-calls-into-question-the-meaning-of-global-health-security/ [Google Scholar]

- 3.Taylor S. In pursuit of zero: polio, global health security and the politics of eradication in Peshawar, Pakistan. Geoforum 2016;69:106–16. 10.1016/j.geoforum.2016.01.004 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Fidler D. Epic failure of ebola and global health security. Articles by Maurer Faculty 2015;179–97. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Gostin LO, Hodge JG. Zika virus and global health security. Lancet Infect Dis 2016;16:1099–100. 10.1016/S1473-3099(16)30332-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Kuteleva A, Clifford SJ. Gendered securitisation: Trump’s and Putin’s Discursive politics of the COVID-19 pandemic. Eur J of Int Secur 2021;6:301–17. 10.1017/eis.2021.5 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Singh S. Infectious diseases national security and globalisation. World Affairs: J Inter Issue 2019;23:10–23. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Wenham C. The Oversecuritization of global health: changing the terms of debate. Int Aff 2019;95:1093–110. 10.1093/ia/iiz170 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Fidler D. A pathology of public health Securitism: approaching Pandemics as security threats. In: Cooper A, Kirton J, eds. Governing Global Health: Challenge, Response, Innovation. Farnham, England: Ashgate Publishing, 2007: 41–64. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Peterson S. Epidemic disease and national security. Security Studies 2002;12:43–81. 10.1080/0963-640291906799 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 11.King NB. Security, disease, commerce: ideologies of postcolonial global health. Soc Stud Sci 2002;32:763–89. 10.1177/030631202128967406 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Garrett L. The coming plague: Newly emerging diseases in a world out of balance. Royal Tunbridge Wells, England: Atlantic Books, 1994. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Lederberg J, Shope RE, Oaks SC. Emerging infections: Microbial threats to health in the United States. Washington, DC: National Academies Press, 1992. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Elbe S. HIV/AIDS and the changing landscape of war in Africa. International Security 2002;27:159–77. 10.1162/016228802760987851 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Mcinnes C. HIV/AIDS and security. Int Aff 2006;82:315–26. 10.1111/j.1468-2346.2006.00533.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Sjöstedt R. Health issues and securitization: the construction of HIV/AIDS as a US national security threat. In: Balzacq T, ed. Securitization Theory, 1st edn. London: Routledge, 2010: 164–83. 10.4324/9780203868508 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Rushton S. AIDS and international security in the United Nations system. Health Policy Plan 2010;25:495–504. 10.1093/heapol/czq051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.United Nations Security Council . In: Resolution 1308 on the Responsibility of the Security Council in the Maintenance of International Peace and Security: HIV/AIDS and International Peacekeeping Operations. 2000. [Google Scholar]

- 19.Tan W-J, Enderwick P. Managing threats in the global era: the impact and response to SARS. Thunderbird Int’l Bus Rev 2006;48:515–36. 10.1002/tie.20107 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fidler DP. Governing catastrophes: security, health, and humanitarian assistance. Int Rev Red Cross 2007;89:247–70. 10.1017/S1816383107001105 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Wright S. Terrorists and biological weapons: forging the linkage in the Clinton administration. Politics Life Sci 2006;25:57–115. 10.2990/1471-5457(2006)25[57:TABW]2.0.CO;2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.United Nations . A more secure world - our shared responsibility – report of the high-level panel on threats, challenges and change. 2004. 10.1163/ej.9789004151314.i-531

- 23.World Health Organization . International health regulations. Available: https://www.who.int/health-topics/international-health-regulations#tab=tab_1

- 24.Fidler DP, Gostin LO. The new International health regulations: an historic development for international law and public health. J Law Med Ethics 2006;34:85–94, 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2006.00011.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Kamradt-Scott A. New powers for a new age? revising and updating the IHR. In: Kamradt-Scott A, ed. Managing Global Health Security. Palgrave Macmillan, 2015. 10.1057/9781137520166 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Fidler D. Health as foreign policy: between principle and power. Articles by Maurer Faculty 2005;525:179–94. [Google Scholar]

- 27.Burci GL. Ebola, the Security Council and the securitization of public health. Questions of International Law 2014. Available: http://www.qil-qdi.org/ebola-security-council-securitization-public-health/ [Google Scholar]

- 28.UN Mission for Ebola emergency response (UNMEER) . Global Ebola response. 2014. Available: https://ebolaresponse.un.org/un-mission-ebola-emergency-response-unmeer

- 29.Hajra A, Bandyopadhyay D, Hajra SK. Zika virus: a global threat to humanity: a comprehensive review and current developments. N Am J Med Sci 2016;8:123–8. 10.4103/1947-2714.179112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Daoudi S. The war on COVID-19: the 9/11 of health security? Policy Centre for the New South 2020:1–15. [Google Scholar]

- 31.Gibson-Fall F. Military responses to COVID-19, emerging trends in global civil-military engagements. Rev Int Stud 2021;47:155–70. 10.1017/S0260210521000048 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Luscombe A, McClelland A. Policing the pandemic: tracking the policing of covid-19 across canada. SocArXiv [Preprint] 2020. 10.31235/osf.io/9pn27 [DOI]

- 33.Abbas M, Aloudat T, Bartolomei J, et al. Migrant and refugee populations: a public health and policy perspective on a continuing global crisis. Antimicrob Resist Infect Control 2018;7:113. 10.1186/s13756-018-0403-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.UNEP - UN Environment Programme . Antimicrobial resistance: a global threat. 2020. Available: https://www.unep.org/explore-topics/chemicals-waste/what-we-do/emerging-issues/antimicrobial-resistance-global-threat [Google Scholar]

- 35.Kickbush I. Governing the global health security domain. Graduate Institute Geneva, 2016: 1–23. [Google Scholar]

- 36.Popkin BM. Is the obesity epidemic a national security issue around the globe? Curr Opin Endocrinol Diabetes Obes 2011;18:328–31. 10.1097/MED.0b013e3283471c74 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Ingram A. Pandemic Anxiety and Global Health Security. Fear: Critical Geopolitics and Everyday Life. Routledge, 2008: 75–85. [Google Scholar]

- 38.Owotomo O. Opioid epidemic and homeland security: an integrative framework of intricacies and proposed solutions. In: Decadal Survey of Social and Behavioral Sciences for Applications to National Security, National Academies of Sciences, Engineering, and Medicine. 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 39.Moodie A, D’Alessandra NGW. Rethinking health security after COVID-19. Oxford Institute for ethics, law and armed conflict. 2021:1–23. Available: https://www.elac.ox.ac.uk/wp-content/uploads/2023/04/ELAC-Policy-Paper_Rethinking-Health-Security.pdf-.pdf

- 40.Davies SE. What contribution can international relations make to the evolving global health agenda? Int Aff 2010;86:1167–90. 10.1111/j.1468-2346.2010.00934.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Bhattacharya D. An exploration of conceptual and temporal fallacies in international health law and promotion of global public health preparedness. J Law Med Ethics 2007;35:588–98. 10.1111/j.1748-720X.2007.00182.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Aldis W. Health security as a public health concept: a critical analysis. Health Policy Plan 2008;23:369–75. 10.1093/heapol/czn030 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Roberts SL, Elbe S. Catching the flu: syndromic surveillance, algorithmic governmentality and global health security. Security Dialogue 2017;48:46–62. 10.1177/0967010616666443 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Lakoff A. The risks of preparedness: mutant bird flu. Public Culture 2012;24:457–64. 10.1215/08992363-1630636 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 45.David P-M, Le Dévédec N. Preparedness for the next epidemic: health and political issues of an emerging paradigm. Critical Public Health 2019;29:363–9. 10.1080/09581596.2018.1447646 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Holst J, Razum O. Global health and health security – conflicting concepts for achieving stability through health Glob Public Health 2022;17:3972–80. 10.1080/17441692.2022.2049342 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Holst J, van de Pas R. The BIOMEDICAL securitization of global health. Global Health 2023;19. 10.1186/s12992-023-00915-y [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.United Nations Development Programme. New dimensions of human security. Human Development Report 1994. 10.18356/87e94501-en [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Ogata S, Cels J. Human security—protecting and empowering the people. GG 2003;9:273–82. 10.1163/19426720-00903002 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Horton R. Offline: global health security-smart strategy or naive tactics? Lancet 2017;389. 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30637-2 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Horton R. Offline: the mistakes we made over ebola. Lancet 2019;394:10208. 10.1016/S0140-6736(19)32634-0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Wenham C. Ebola Respons-Ibility: moving from shared to multiple responsibilities. Third World Quarterly 2016;37:436–51. 10.1080/01436597.2015.1116366 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Pagnoni F, Bosman A. Malaria kills more than ebola virus disease. Lancet Infect Dis 2015;15:988–9. 10.1016/S1473-3099(15)00075-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Binns CW, Low WY. A simple solution that saves lives: overcoming diarrheal disease in the age of universal health coverage. Asia Pac J Public Health 2018;30:604–6. 10.1177/1010539518809444 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Hameiri S. Avian influenza, ‘viral sovereignty’, and the politics of health security in Indonesia. The Pacific Review 2014;27:333–56. 10.1080/09512748.2014.909523 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Elbe S. Who owns a deadly virus? Viral sovereignty, global health emergencies, and the matrix of the International. Int Polit Sociol 2022;16. 10.1093/ips/olab037 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Daoudi S. Vaccine nationalism in the context of COVID-19: an obstacle to the containment of the pandemic. Policy Centre for the New South 2020:1–10. [Google Scholar]

- 58.Oxfam International . G7 vaccines failures contribute to 600,000 preventable deaths. 2022. Available: https://www.oxfam.org/en/press-releases/g7-vaccines-failures-contribute-600000-preventable-deaths

- 59.Amin T, Kesselheim AS. A global intellectual property waiver is still needed to address the inequities of COVID-19 and future pandemic preparedness. Inquiry 2022;59:00469580221124821. 10.1177/00469580221124821 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Newman E. Covid-19: a human security analysis. Global Society 2022;36:431–54. 10.1080/13600826.2021.2010034 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Rangel JC, Ranade S, Sutcliffe P, et al. COVID ‐19 policy measures—advocating for the inclusion of the social determinants of health in modelling and decision making. J Eval Clin Pract 2020;26:1078–80. 10.1111/jep.13436 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Michaud J, Moss K, Licina D, et al. Militaries and global health: peace, conflict, and disaster response. Lancet 2019;393:276–86. 10.1016/S0140-6736(18)32838-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 63.Buzan B, Wæver O, de Wilde J. Security: A new framework for analysis. Boulder, CO: Lynne Rienner, 1997. 10.1515/9781685853808 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Hanrieder T, Kreuder-Sonnen C. WHO decides on the exception? securitization and emergency governance in global health. Security Dialogue 2014;45:331–48. 10.1177/0967010614535833 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Kamradt-Scott A, Harman S, Wenham C, et al. Civil-military cooperation in ebola and beyond. Lancet 2016;387:104–5. 10.1016/S0140-6736(15)01128-9 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Harman S, Wenham C. Governing ebola: between global health and medical humanitarianism. Globalizations 2018;15:362–76. 10.1080/14747731.2017.1414410 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Eba PM. Ebola and human rights in West Africa. Lancet 2014;384:2091–3. 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)61412-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Vaughn J. The unlikely securitizer: humanitarian organizations and the securitization of Indistinctiveness. Security Dialogue 2009;40:263–85. 10.1177/0967010609336194 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Larson HJ, Bhutta ZA. Security, insecurity, and health workers: the case of polio. JAMA Intern Med 2013;173:1393–4. 10.1001/jamainternmed.2013.7191 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Bouchet-Saulnier F, Whittall J. An environment conducive to mistakes? lessons learnt from the attack on the Médecins Sans Frontières hospital in Kunduz, Afghanistan. Int Rev Red Cross 2018;100:337–72. 10.1017/S1816383118000619 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Zarocostas J. Attacks on healthcare professionals risk health of millions, says red cross. BMJ 2011;343:bmj.d5118. 10.1136/bmj.d5118 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Haar RJ, Read R, Fast L, et al. Violence against healthcare in conflict: a systematic review of the literature and agenda for future research. Confl Health 2021;15:37. 10.1186/s13031-021-00372-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Madianou M. Technocolonialism: digital innovation and data practices in the humanitarian response to refugee crises. Social Media + Society 2019;5:205630511986314. 10.1177/2056305119863146 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 74.Bishop M, Philanthrocapitalism GM. How the Rich Can Save the World and Why We Should Let Them. London: A & C Black, 2008. [Google Scholar]

- 75.McCoy D, McGoey L. Global health and the gates foundation—in perspective. In: O W, S R, eds. Health Partnerships and Private Foundations: New Frontiers in Health and Health Governance. London: Palgrave, 2011: 143–63. [Google Scholar]

- 76.Glassner B. The culture of fear: Why Americans are afraid of the wrong things: Crime, drugs, minorities, teen moms, killer kids. Perseus Books, 2010. [Google Scholar]

- 77.Wilkinson A, Fairhead J. Comparison of social resistance to ebola response in Sierra Leone and guinea suggests explanations lie in political configurations not culture. Crit Public Health 2017;27:14–27. 10.1080/09581596.2016.1252034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Kennedy J. How drone strikes and a fake vaccination program have inhibited polio eradication in Pakistan: an analysis of national level data. Int J Health Serv 2017;47:807–25. 10.1177/0020731417722888 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 79.Guterres A. The world faces a pandemic of human rights abuses in the wake of COVID-19. 2021. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/global-development/2021/feb/22/world-faces-pandemic-human-rights-abuses-covid-19-antonio-guterres

- 80.Levy Y. “The people’s army “Enemising” the people: the COVID-19 case of Israel”. Eur J of Int Secur 2022;7:104–23. 10.1017/eis.2021.33 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Sharon T. Blind-sided by privacy? Digital contact tracing, the apple/Google API and big Tech's newfound role as global health policy makers. Ethics Inf Technol 2021;23:45–57. 10.1007/s10676-020-09547-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.French M, Guta A, Gagnon M, et al. Corporate contact tracing as a pandemic response. Critical Public Health 2022;32:48–55. 10.1080/09581596.2020.1829549 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 83.UN News . Omicron COVID variant underlines need for global ‘pandemic treaty. 2021. Available: https://news.un.org/en/story/2021/11/1106722

- 84.Associated Press . USAID programme used young Latin Americans to incite Cuba rebellion. 2014. Available: https://www.theguardian.com/world/2014/aug/04/usaid-latin-americans-cuba-rebellion-hiv-workshops

- 85.Heath-Kelly C. Algorithmic Autoimmunity in the NHS: Radicalisation and the clinic. Security Dialogue 2017;48:29–45. 10.1177/0967010616671642 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Legido-Quigley H, Clark H, Nishtar S, et al. Reimagining health security and preventing future Pandemics: the NUS-lancet pandemic readiness, implementation, monitoring, and evaluation Commission. Lancet 2023;401:2021–3. 10.1016/S0140-6736(23)00960-1 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

No data are available.