Abstract

Rapid instructed task learning (RITL) is the uniquely human ability to transform task information into goal-directed behavior without relying on trial-and-error learning. RITL is a core cognitive process supported by functional brain networks. In patients with schizophrenia, RITL ability is impaired, but the role of functional network connectivity in these RITL deficits is unknown. We investigated task-based connectivity of eight a priori network pairs in participants with schizophrenia (n = 29) and control participants (n = 31) during the performance of an RITL task. Multivariate pattern analysis was used to determine which network connectivity patterns predicted diagnostic group. Of all network pairs, only the connectivity between the cingulo-opercular network (CON) and salience network (SAN) during learning classified patients and control participants with significant accuracy (80%). CON-SAN connectivity during learning was significantly associated with task performance in participants with schizophrenia. These findings suggest that impaired interactions between identification of salient stimuli and maintenance of task goals contributes to RITL deficits in participants with schizophrenia.

Keywords: rapid instructed task learning, cognitive deficits, schizophrenia, salience network, cingulo-opercular network, MVPA

Humans have the unique ability to transfer instructions into behavior with high accuracy and fidelity. This process is both flexible and adaptive, allowing for rapid transmission of information into goal-directed behavior. Unlike trial-and-error learning, which requires sometimes hundreds of trials to accomplish desired behaviors in response to specific demands, rapid instructed task learning (RITL) can occur almost instantaneously as symbolic instructions are translated into a sequence of pragmatic motor outputs (Cole, Patrick, Meiran, & Braver, 2017; Wolfensteller & Ruge, 2012). RITL begins with a single trial; however, learning is reflected in efficiency gains as instructed rules are practiced (Chein & Schneider, 2012). Although a less frequently studied area of cognition, RITL is often a core feature of neurocognitive tasks (Cole, Laurent, & Stocco, 2013b). Schizophrenia is characterized by a generalized deficit in higher-order cognition (Heinrichs & Zakzanis, 1998), which is typically measured using instructed cognitive tasks; however, despite decades of research describing patients’ impaired performance on RITL-dependent tasks, only recently were RITL deficits identified in patients with schizophrenia (Sheffield, Ruge, Kandala, & Barch, 2018). RITL accuracy correlated with cognitive performance on a separate set of higher order cognitive tasks, which suggests that impaired RITL ability explains significant variance in the generalized cognitive deficit.

Task-based functional MRI activations during RITL revealed overall reduced activity in frontal cortex and bilateral caudate in patients with schizophrenia (Sheffield et al., 2018); however, emerging evidence suggests that patterns of network functional connectivity throughout learning are equally if not more important for understanding the cognitive processes underlying RITL (Cole, Braver, & Meiran, 2017). In a recent study using the same RITL task, several large-scale functional networks, including the default mode network (DMN), cingulo-opercular network (CON), salience network (SAN), and dorsal attention network (DAN), were found to demonstrate differential connectivity patterns between early and late learning (Mohr et al., 2016). During RITL, the CON, DAN, and SAN support tonic maintenance of task goals, orientation of top-down attention to stimuli for initial processing, and assignment of salience to stimuli for further processing, respectively. A CON–SAN connectivity increase over the course of the RITL paradigm indicates enhanced involvement of these networks during learning, whereas DMN demonstrates greater segregation from task-positive networks, reflecting greater automatization of task rules. Critically, these network changes were significantly greater than those observed during a one-back working memory task, which has similar general task characteristics, indicating learning-specific dynamics. These connectivity dynamics also occurred within the context of significantly greater improvement in reaction time (RT) for the RITL compared with the one-back task, reflecting a behavioral output of network reconfiguration during learning.

In patients with schizophrenia, functional connectivity of large-scale networks is abnormal during rest, indicating intrinsic alterations in communication within and among brain regions that support cognitive processing (Woodward, Rogers, & Heckers, 2011). Although altered resting-state connectivity of the CON, SAN, and DMN have been observed in patients with schizophrenia (Kottaram et al., 2019; Sheffield et al., 2017; Supekar, Cai, Krishnadas, Palaniyappan, & Menon, 2019) and are associated with cognitive impairment (Moran et al., 2013; Sheffield, Kandala, Burgess, Harms, & Barch, 2016; Whitfield-Gabrieli et al., 2009), the connectivity of these networks during rapid task learning has never before been investigated. Transmission of information within and between functional brain networks facilitates practice-related efficiency, which is reflected in faster RTs over the course of learning. Investigation of group differences in connectivity profiles during early-learning trials compared with late-learning trials can elucidate which networks are altered in patients with schizophrenia, providing increased insight into the cognitive processing dynamics that may be contributing to impaired task learning.

Here we aimed to test the hypothesis that connectivity of networks known to be involved in RITL is altered in patients with schizophrenia and contributes to reduced learning efficiency of instructed task rules. We specifically investigated eight network connectivity pairs that have demonstrated learning-related changes during the same RITL task in two independent samples of healthy participants (Mohr et al., 2016; Mohr, Wolfensteller, & Ruge, 2018), allowing us to test whether normative task-based connectivity changes over learning, are abnormal in participants with schizophrenia. We sought to determine whether these network connectivity profiles were abnormal in participants with schizophrenia, distinct for early (Trials 1–3) or late (Trials 8–10) learning, and associated with efficiency in task processing.

Method

Participants

Data collection is described in detail in the Supplemental Material available online. Twenty-nine participants with schizophrenia and 31 control participants (Table 1) were recruited from the St. Louis, Missouri, area and signed written informed consent before completing the study, which was approved by the Washington University Institutional Review Board. Data from these participants were previously analyzed and presented in Sheffield et al. (2018).

Table 1.

Demographics

| Demographic | Control group (n = 31) | Schizophrenia group (n = 29) | Difference between groups |

|---|---|---|---|

| Age | 34.69 years (10.47) | 37.79 years (12.47) | t = −1.03, p = .309 |

| Gender (male/female) | 23/8 | 22/7 | χ2 = 0.02, p = .881 |

| Race (White/African American/other) | 9/18/3 | 12/15/2 | χ2 = 0.89, p = .643 |

| Personal education | 16.55 years (3.05) | 12.69 years (3.65) | t = 4.46, p < .001 |

| Parental education | 14.69 years (3.31) | 14.06 years (4.14) | t = 0.65, p = .52 |

| WTAR premorbid IQ | 31.7 (11.97) | 28.45 (12.24) | t = 0.99, p = .326 |

Note: Values in parentheses are standard deviations. WTAR = Wechsler Test of Adult Reading (Wechsler, 2001).

Exclusion criteria included a history of neurological disorder, seizures or electroconvulsive therapy within the last 12 months, history of a serious medical illness such as cancer, loss of consciousness due to a head injury, or history of a developmental disorder. Control participants were excluded if they had a first-degree relative with a psychotic disorder diagnosis. Participants were excluded if they met criteria for current depressive episode or substance use disorder according to the Structured Clinical Interview of the DSM-5 (First, Spitzer, Gibbon, & Williams, 1995), which was also used to confirm a diagnosis of schizophrenia or schizoaffective disorder in the patient group.

RITL task

The task is a modified version of a common RITL paradigm (Ruge & Wolfensteller, 2010; see Fig. S1 in the Supplemental Material). All participants passively viewed four unique abstract shapes for 10 s (instruction phase). Under two of the shapes were the instructions “index finger,” and under the other two shapes were the instructions “middle finger.” Then, participants viewed each shape one at a time and were instructed to press the button with the finger associated with that stimulus during the instruction phase. This learning phase consisted of 40 trials (10 of each shape) randomly intermixed and included feedback following each response (“correct,” “incorrect,” or “too slow”). Stimuli were presented for 1,500 ms, followed by 500-ms feedback and then a fixation cross (1–3.5 s jittered). Six blocks were included, each with novel sets of four stimuli, totaling 240 implementation trials, and took approximately 19 min. Before entering the scanner, participants were trained on the task environment with different stimuli, ensuring knowledge of task environment (resulting in no dropouts during scanning).

The primary behavioral outcome of interest was relative RT, which measures improvement in RT over the course of the task, reflecting learning (Oishi et al., 2005). To be consistent with previous work (Mohr et al., 2016), we calculated relative RT through the following formula: 100 × (1 − late RT / early RT); early RT is the average median RT for the first, second, and third repetitions of a stimulus, whereas late RT is the average median RT for the eighth, ninth, and 10th repetitions of a stimulus, ignoring “too slow” trials. Throughout the article, early learning refers to Trials 1, 2, and 3, and late learning refers to Trials 8, 9, and 10. Stimulus-response pairs are the most novel during early trials and are most practiced (i.e., learned) during late trials. Relative RT (based on an early-late partition) therefore reflects efficiency gains during learning.

MRI data processing and general linear model

Details on MRI data acquisition (3T connectome scanner) and preprocessing using Human Connectome Project pipelines (Glasser et al., 2013) are reported in the Supplemental Material.

A voxel-wise general linear model was estimated using canonical hemodynamic response functions for each subject in SPM8 run with MATLAB (The MathWorks, Natick, MA). The design matrix of the model encompassed 10 event-related regressors corresponding to the 10 learning trials (i.e., repetitions of each stimulus), a regressor for the instruction phase with a duration of 10 s, and six movement regressors. To be consistent with prior analysis of the current task in control participants (Mohr et al., 2016, 2018), we used a previously established two-step procedure to estimate task-based connectivity (Braun et al., 2012; Cao et al., 2014). First, mean task-related activity was removed, then task-based connectivity was estimated on the basis of the residuals after mean activity was regressed out. Similar to a psychophysiological-interaction approach, this procedure controls for overall task activation while retaining sources of variance that drive connectivity effects (i.e., task-related connectivity). The high-pass filter was set to a cutoff frequency of 1/128 Hz. Modeling of temporal autocorrelations was switched off (i.e., AR[1] off) because the residual time series were subsequently used to estimate functional connectivity values. Activation contrasts were defined for early learning and late learning. Residual time series of the general linear model were used for connectivity analyses.

Functional networks

Functional networks were defined as proposed in Cole et al. (2013a). From the original 264 network nodes provided by Power et al. (2011), 227 network nodes (4-mm radius sphere, 33 voxels) were assigned to 10 functional networks. Nodes were excluded from further analyses for that subject if more than 16 voxels (i.e., more than 50% of 33 voxels) were located outside the whole-brain mask. Nodes were also excluded from further analyses if they were excluded for more than 10% of the subjects. On the basis of this procedure, 215 of the 227 nodes were included into the final analyses. Nodes were assigned to the DMN (51 nodes), the visual network (31 nodes), the auditory network (13 nodes), the CON (14 nodes), the SAN (18 nodes), and the DAN (11 nodes). As noted above, only the functional networks that had previously demonstrated connectivity changes during the RITL task, replicated across two independent data sets of healthy participants, were selected for analysis (Mohr et al., 2016, 2018). Moreover, to help control for motion (Power et al., 2014), a large region termed power complement included all voxels with a minimum distance of 8 mm to any network node. The power complement region was used to extract a time series for global signal correction to avoid circular analysis (Murphy, Birn, Handwerker, Jones, & Bandettini, 2009).

Connectivity analysis

Functional connectivity values for early and late learning were computed as Pearson correlation coefficients between residual time series of the GLM, for each region of interest, during early-learning and late-learning trials. The resulting correlation values were Fisher z transformed and averaged across blocks. For univariate connectivity analysis, mean connectivity values were computed by averaging across all connections between and within the respective networks. For multivariate pattern analysis (MVPA), the connectivity values were not averaged across connections but instead used as features for the classification procedure.

Data analysis

Univariate analysis.

Group-level analyses were conducted using a 2 × 2 analysis of variance (ANOVA) comprising the learning (late vs. early) and group (participants with schizophrenia vs. control participants) factors and the interaction between them. Connectivity analyses were constrained to networks and pairs of networks that have been associated with instruction-based learning before and replicated across two independent samples (Mohr et al., 2016, 2018): DMN–visual network, DMN–CON, DMN–SAN, DMN–auditory network, visual network–CON, CON–SAN, CON–DAN, and CON–CON (i.e., within CON). Accordingly, connectivity results were Bonferroni-corrected for eight tests (.05 / 8), and adjusted p values are presented.

Multivariate pattern analysis.

In contrast to the univariate analysis, which was based on mean connectivity values obtained by averaging across all connections between network pairs, we conducted MVPA (Pereira, Mitchell, & Botvinick, 2009) to detect distributed patterns of connectivity changes. The MVPA aimed at predicting the group label (participants with schizophrenia or control participants) for each subject according to the connectivity changes from early to late learning. To this end, the difference between early and late connectivity was computed for each pair of network nodes, and connectivity values were not averaged but instead used as high-dimensional input features for MVPA. For example, the CON consisted of 14 nodes and the SAN of 18 nodes; thus, there were 14 × 18 = 252 connections between these two networks. In the MVPA, the late-early connectivity differences were not averaged but instead used as a 252-dimensional feature vector to predict the group labels of the subjects.

A linear support-vector machine (SVM) was trained using Libsvm (Chang & Lin, 2012) on late-early connectivity values from all but two left-out subjects (one from each group). The analysis was implemented using MATLAB (Version 2018; The MathWorks, Natick, MA) on Windows 7 together with Libsvm 3.23. The code is available on Github: https://github.com/holger-m/MVPA-cross-validation/tree/master/Model_CON_SAN. The trained classifier was tested by predicting the group labels of the two left-out subjects. The leave-two-subjects-out cross-validation included all possible leave-two-subjects-out (one per group) combinations (31 × 29 SVM models). Individuals with schizophrenia were labeled with +1 and control participants with −1. The C-parameter of the SVM was optimized along the range {2−5, 2−4, …, 21}. A leave-two-subjects-out cross-validation was performed on the training data for parameter optimization in the same way as in the outer loop (i.e., using all possible pairs with one subject from each group as test sets). Overall, (31 × 30 / 2) × (29 × 28 / 2) = 188,790 models were fitted during this process. For details, see the MVPA code on Github: https://github.com/holger-m/MVPA-cross-validation. This computationally demanding procedure was implemented to optimize the C-parameter in an unbiased way (Kriegeskorte, Simmons, Bellgowan, & Baker, 2009). Classification accuracies were computed by averaging across all cross-validation folds using the respective optimized C-parameter.

As a first stage, classification accuracies were tested for statistical significance (i.e., against the chance level of 50%) using a binomial test. If the p value of the binomial test was significant after Bonferroni correction for eight tests, a second-stage, more conservative permutation test was implemented for the respective pair of networks (Winkler, Ridgway, Webster, Smith, & Nichols, 2014) because the binomial test is known to be too optimistic for MVPA cross-validation schemes (Schreiber & Krekelberg, 2013). For permutation testing, the null distribution of the classification accuracy was sampled by randomly permuting group labels 10,000 times, followed by a complete run of the cross-validation scheme including nested cross-validations.

Brain–behavior analysis

Relationships between rapid task learning and network connectivity were investigated in linear regressions with group, network connectivity, and a Group × Connectivity interaction term predicting relative RT. Relationships were investigated only for network measures demonstrating a significant group interaction, reflecting differential connectivity during learning in participants with schizophrenia. Significant group interactions were followed up by comparing magnitude of Pearson’s correlation coefficient between groups using Fisher’s r-to-z transform and subsequent z test.

Results

Task behavior

The number of too-slow trials was similar between groups, t(58) = 1.64, p = .121. As previously reported (Sheffield et al., 2018), participants with schizophrenia were significantly impaired on RITL performance, reflected in significantly reduced relative RT, F(1, 58) = 10.22, p = .002, Cohen’s d = −0.82. This indicated that the relative improvement in RT between early and late trials in the participants with schizophrenia was almost 1 SD below the relative improvement seen in control participants even within the context of similar premorbid IQ.

Network connectivity

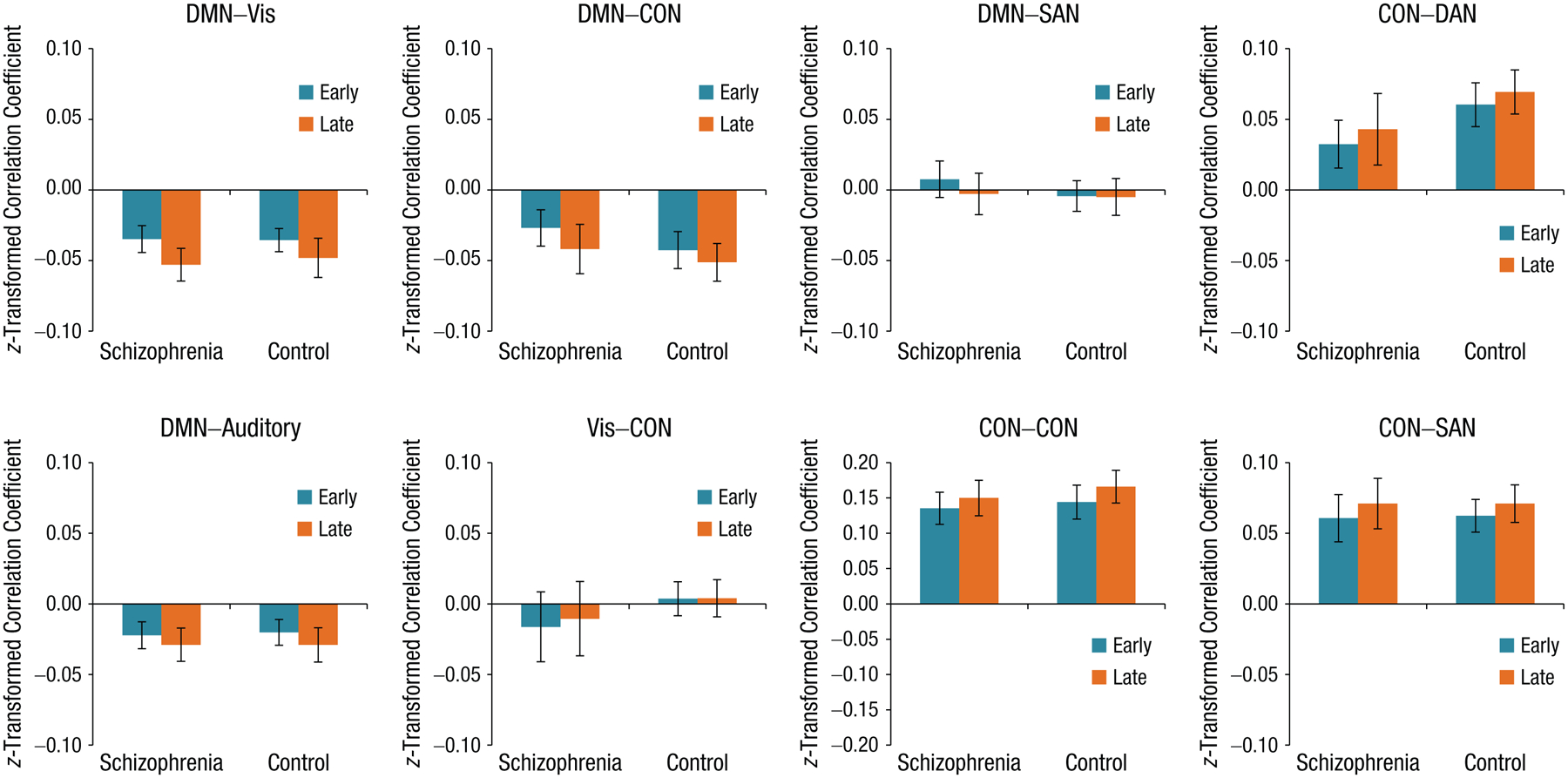

Connectivity was investigated for the CON–CON pair and the other seven network pairs recently reported to be involved in task learning (Mohr et al., 2016), which allowed direct assessment of group differences for networks known to be engaged during the RITL task (Mohr et al., 2018; Fig. 1). Connectivity within the CON increased from early to late trials, F(1, 56) = 14.14, p = .003, across all participants, which replicates previous findings in an independent group. No group difference, F(1, 56) = −0.61, p = 1.00, or significant interaction with group, F(1, 56) = 0.57, p = 1.00, was found for CON–CON connectivity.

Fig. 1.

Connectivity between a priori network pairs from early and late trials for participants with schizophrenia and control participants, calculated using a univariate approach. Average task-based functional connectivity of a priori networks previously found to demonstrate significant changes in connectivity during the RITL task, in an independent data set (Mohr et al. 2016). Using analysis of variance, we observed Bonferroni-corrected significant changes in connectivity between early and late learning trials across all participants, as follows: DMN-visual (t = −4.69, p < .001), DMN–CON (t = −3.27, p = .014), and CON–CON (t = 3.77, p = .003). No significant group differences in connectivity were observed using this univariate approach. Early trials = Trials 1 through 3; late trials = Trials 8 through 10; DMN = default mode network; CON = cingulo-opercular network; SAN = salience network; DAN = dorsal attention network; patient = participants with schizophrenia; control = control participants.

Coupling between networks also exhibited changes over the course of learning. The DMN was more decoupled from the CON, F(1, 56) = 10.65, p = .015, and visual network, F(1, 56) = 21.87, p < .001, during late compared with early-learning trials, in line with previous findings (Mohr et al., 2016) in a separate sample. Furthermore, CON–SAN connectivity increased during learning, F(1, 56) = 7.73, p = .059, also consistent with prior results in healthy participants. Connectivity changes over the course of learning between DMN–auditory, F(1, 56) = 6.79, p = .096; DMN–SAN, F(1, 56) = 3.62, p = .498; CON–DAN, F(1, 56) = 5.92, p = .145; and CON–visual, F(1, 56) = 0.59, p = 1.00, were all nonsignificant after correcting for multiple comparisons.

Although connectivity between multiple networks significantly changed during task learning, no significant group differences in the magnitude of network connectivity during the task were observed. Furthermore, according to results of univariate ANOVA, there were no significant group-by-learning interactions (see Table S1 in the Supplemental Material). These findings suggest that, on average, connectivity between DMN, CON, SAN, and visual networks all changed in strength over the course of learning to a similar degree in participants across both groups.

Multivariate pattern analysis

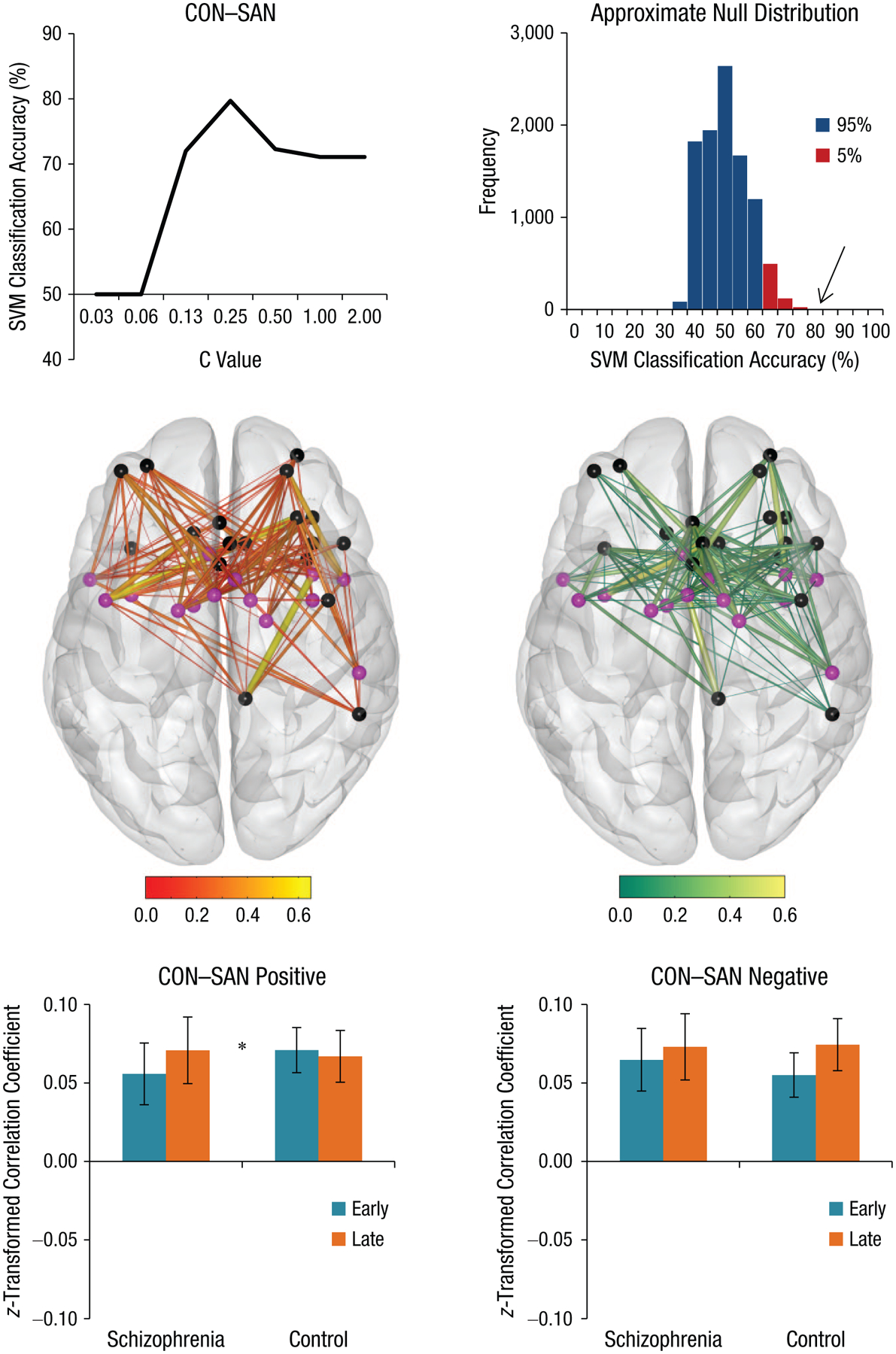

Although multiple networks demonstrated increased connectivity strength over the course of learning, no significant interactions with group were detected using mean connectivity values. Univariate analysis on averaged connectivity values may not be sufficiently sensitive to detect interactions with group, and therefore, as has been done previously (Mohr et al., 2018), we conducted MVPA analysis on the eight network connections of interest using individual connections between and within networks as predictive features. These results (Fig. 2) demonstrate that connectivity CON–SAN predicted group labels with high accuracy (79.59%, p = .0016 correct for eight tests, chance-level accuracy 50%). See Figure S3 in the Supplemental Material for a histogram of probability outcomes. In addition, statistical significance of the finding was confirmed with a more conservative threefold cross-validation (see Fig. S3 in the Supplemental Material). For a discussion of the impact of different test set sizes on classification accuracy, also see Figure S4 in the Supplemental Material. This result is highly specific for the CON–SAN connections given that no other network connections were able to classify participant group with significant accuracy (all accuracies < 60%; see Table S1 in the Supplemental Material). For a 3D visualization of the SVM weights, see video files in the Supplemental Material.

Fig. 2.

Results of multivariate pattern analysis. Cingulo-opercular network (CON) and salience network (SAN) connectivity during early- and late-learning trials significantly classified participants with schizophrenia and control participants. A support-vector machine (SVM) was used to classify individual connectivity profiles into two groups (schizophrenia or control). CON–SAN connectivity profiles classified participants with significant accuracy (79.59%, p = .002), and accuracy can be seen across different cost constants (C value). Transparent brains depict connectivity between nodes of the CON (purple) and SAN (black) for positively and negatively weighted SVMs. Of the 252 connections between the CON and SAN, 124 were positively weighted (49.2%) and 128 were negatively weighted (50.8%) by the SVM. A significant Group × Practice (early or late) interaction was observed for the positively weighted SVM (t = 2.10, p = .04), reflecting relatively stronger connectivity of CON–SAN during late compared with early-learning trials in participants with schizophrenia. Early = Trials 1 through 3; late = Trials 8 through 10. The asterisk indicates a significant difference between groups (*p < .05).

Brain–behavior relationships

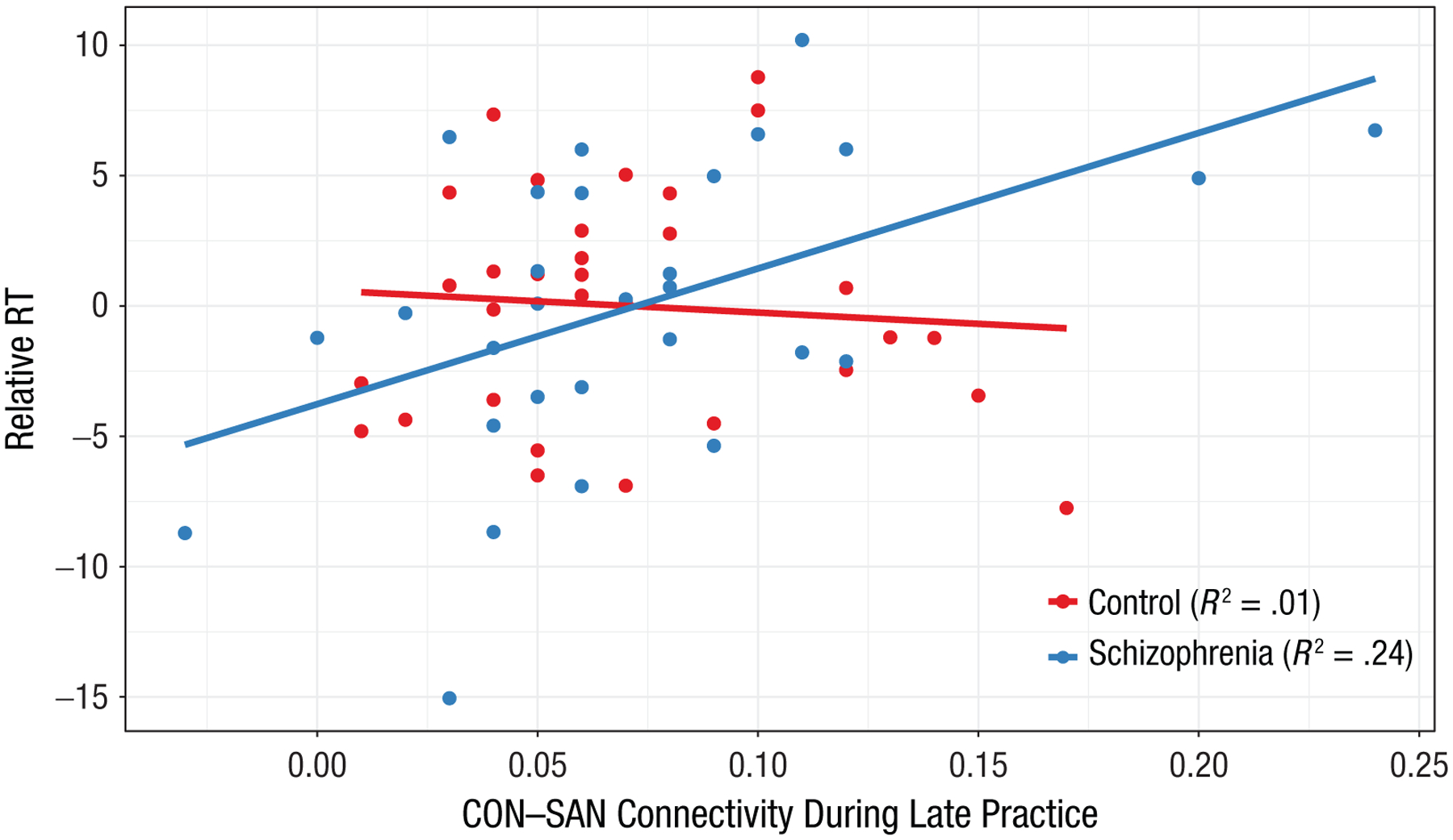

Because CON–SAN connectivity was the only network measure with significant classification accuracy and a significant group interaction, indicating differential network connectivity over the course of learning in participants with schizophrenia, MVPA results were investigated for associations with task-learning efficiency (i.e., relative RT) in two separate regressions for early and late connections. Analysis of early-learning trials compared with late-learning trials allows for inference of the time course of cognitive processing deficits in participants with schizophrenia (i.e., whether it is initial CON–SAN connectivity following instruction that contributes to lower learning-related efficiency or whether divergence from a healthy pattern throughout learning contributes to impaired task learning).

A significant group interaction for the relationship between CON–SAN connectivity and task-learning efficiency was observed for late trials (t = −2.27, p = .027) but not for early trials (t = −0.96, p = .342), which suggests that CON–SAN connectivity late in learning was differentially associated with relative improvement in task efficiency in patients and control participants (for full statistics, see Table S2 in the Supplemental Material). Follow-up correlation for late learning (Fig. 3) revealed that task-learning efficiency significantly correlated with CON–SAN connectivity in patients (r = .49, p = .007) but not control participants (r = −.08, p = .659). These associations were significantly stronger in patients than control participants (z = 2.26, p = .024). Correlations remained when controlling for cognitive abilities that may also be used during RITL (processing speed, working memory, executive functioning; see Table S3 in the Supplemental Material), which suggests learning-specific associations. These findings suggest that connectivity between the CON and SAN during late learning more robustly predicts improvement in rapid task learning in patients with schizophrenia than control participants.

Fig. 3.

Scatterplot (with best-fitting regression lines) of the relationship between task-learning performance and cingulo-opercular network (CON) and salience network (SAN) in participants with schizophrenia. Connectivity between CON–SAN during late-learning trials was associated with improvement in reaction time (relative RT) within the schizophrenia group, explaining 24% of the variance in RT improvement in patients. These findings suggest that CON–SAN connectivity during late learning contributes to relative improvement in learning-related efficiency of task performance in participants with schizophrenia.

Discussion

These findings are the first to demonstrate that connectivity between the CON and SAN during RITL is abnormal in patients with schizophrenia and relates to reduced efficiency of task performance. Both patients and control participants exhibited canonical connectivity patterns that replicate previous findings in an independent sample (Mohr et al., 2016, 2018). These patterns, focused mostly around the CON, reflect stronger within- and between-network connectivity over the course of learning in all participants. Although patients did not show differential average connectivity compared with control participants, accounting for individual network connections in multivariate analysis revealed a specific CON–SAN abnormality in patients with schizophrenia such that connectivity between these networks during learning could discriminate between groups with significant accuracy (80%). Brain–behavior relationships revealed that late-learning trials were driving differential associations between CON–SAN connectivity and performance. In patients, stronger CON–SAN connectivity during late trials was associated with greater improvement in RT, whereas this relationship was not observed in control participants. These data suggest that task learning is facilitated by increased CON–SAN connectivity in patients with schizophrenia over the course of practice.

RITL involves both the initial configuration of instruction into motor output and gains in efficiency of task performance. Comparison of RT and network connectivity between early and late trials therefore measures learning-related changes that are specific to RITL (Mohr et al., 2016). Early-learning trials depend on high-level computation and use of working memory (Hampshire et al., 2019), which are less necessary in later learning trials as task rules and behavior become more automated (Ruge & Wolfensteller, 2016). RITL depends on maintenance of current task context (i.e., instructed rules) and identification of salient stimuli within that task context to guide behavior. These attentional demands are supported by the CON and SAN, respectively, both of which exhibit increased within-network connectivity between early- and late-learning trials (Mohr et al., 2016). The CON is believed to integrate task information in a protracted iterative fashion (Dosenbach et al., 2007), allowing for tonic maintenance of task context. The SAN, on the other hand, mediates information processing between large-scale networks and is theorized to mark stimuli as salient for attention and additional processing (Menon & Uddin, 2010). Previous work has demonstrated not only increased within-network connectivity of these networks during RITL but also increased CON–SAN between-network connectivity, suggesting that identification of goal-relevant (i.e., salient) stimuli and information on task context interact to guide successful learning (Mohr et al., 2016).

Abnormalities in both the CON and SAN have been identified in patients with schizophrenia. Global efficiency of the CON is reduced in patients with schizophrenia and associated with cognitive ability, indicating less optimally organized resting-state connectivity (Sheffield et al., 2017). Although reduced during rest, the CON has increased functional connectivity during tasks in patients with schizophrenia, with greater average connectivity during performance of a working memory (two-back) task than is seen in control participants (Godwin, Ji, Kandala, & Mamah, 2017). Aberrant connectivity of the CON in patients with schizophrenia may therefore require increased neural processing to engage working memory—a critical facet of RITL given that task instruction must be maintained in working memory (Hampshire et al., 2019). The SAN also demonstrates aberrant functional connectivity in patients with schizophrenia, with altered dynamic resting-state connectivity patterns, which are less persistent and more variable over time (Supekar, Cai, Krishnadas, Palaniyappan, & Menon, 2019). These altered SAN dynamics in patients with schizophrenia may contribute to difficulties flexibly allocating cognitive-processing resources needed to drive goal-directed behavior. The current data add to the body of research on CON and SAN alterations in patients with schizophrenia by suggesting that connectivity between these networks is abnormal during learning of a simple instructed task; this abnormality may lead to less optimal interactions between maintenance of task instructions and allocation of attentional resources to stimuli salient in the current task context, contributing to impaired RITL ability.

Although CON and SAN connectivity dynamics could be used to discriminate participants with schizophrenia from control participants, it was connectivity during late-learning trials that was most strongly related to task performance, which suggests impaired integration of task context and salience signaling throughout learning of stimulus–response pairs. Studies on learning deficits in patients with schizophrenia have largely focused on reinforcement learning, which requires the incremental encoding of probabilistic reward to form an internal representation of task context (Waltz & Gold, 2016). Although the current RITL task did not involve reinforcement learning, feedback was provided throughout the task regarding whether the behavior on each trial was correct or incorrect, allowing for updating of the task instructions. A recently published experimental protocol designed to disentangle working memory from reinforcement learning also demonstrated slowed learning in patients with schizophrenia (Collins, Albrecht, Waltz, Gold, & Frank, 2017). Furthermore, experimenters identified working memory deficits, not deficits in encoding expected value, as explaining this slowed learning, suggesting that maintenance of task rules is a critical facet underlying behavioral learning deficits observed in patients with schizophrenia. Given that the CON maintains task context and the SAN modulates attentional resources according to task demand and that patients had stronger connectivity during late trials than did control participants, it is possible that patients with schizophrenia do not initially encode instruction as robustly in CON, and through the course of feedback, the CON and SAN increase connectivity, leading to improved task efficiency.

Several limitations of the current results should be noted. First, the observed association between CON–SAN connectivity and learning was relatively large in the context of a small sample. Although connectivity of these networks contributes to learning-related efficiency in patients with schizophrenia, the observed effect size may be inflated relative to the “true” effect size (Yarkoni, 2009). Furthermore, smaller samples allow for more homogeneous participants, limiting generalizability (Schnack & Kahn, 2016) and necessitating replication (Beleites, Neugebauer, Bocklitz, Krafft, Popp, 2013). Although this does not alter the interpretation of our results, it is a critical caveat when considering brain–behavior associations within neuroimaging studies. Second, because of the relatively small sample sizes, we investigated a priori networks that showed significant learning-related connectivity changes in two independent samples of control participants (Mohr et al., 2016, 2018). Subcortical nodes did not show significant learning-related connectivity and therefore were not included in the current analysis despite their common involvement in learning processes. Third, a recent analysis of task-based functional connectivity revealed potential inflation of connectivity estimates when using canonical hemodynamic response functions (Cole et al., 2019), and our results may have been subject to this bias; however, this bias would be expected to affect both groups and all investigated networks equally, suggesting similar interpretation of the significant and specific group difference in CON–SAN connectivity. Fourth, the majority of patients were taking antipsychotic medications at the time of the study. Studies have shown that individuals with schizophrenia have similar pattern and magnitude of cognitive impairment regardless of medication history or current use (Saykin et al., 1994; Torrey, 2002); however, it is possible that medication status affected our findings. Finally, although data on race were collected as part of this study (Table 1), data on ethnicity and culture were not explicitly assessed.

This study is the first to demonstrate that CON-SAN connectivity during task-learning trials is altered in patients with schizophrenia and predicts behavioral performance. Connectivity differences were revealed using an MVPA approach, which (unlike averaged univariate analyses) considers the entire connectivity profile. Examination of RITL in patients with schizophrenia is still in its infancy, and therefore, the limits of RITL deficits and their associated connectivity abnormalities are not yet known. RITL tasks with a larger number of trials could reveal even stronger abnormalities than those observed in the current study, and the specificity of RITL to patients with schizophrenia (vs. other psychiatric disorders) has yet to be tested. Together, these data suggest that abnormal maintenance of task context and detection of goal-relevant stimuli leads to impaired learning in patients with schizophrenia even when explicit instructions and reliable feedback on performance are provided. In light of these findings, it is encouraged that RITL ability is considered when assessing cognitive deficits in instructed laboratory tasks in patients with schizophrenia and that altered CON–SAN connectivity is considered a vulnerability for poor skills learning in the daily life of individuals managing schizophrenia.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgments

We thank the Center for Information Services and High Performance Computing (ZIH) at Technische Universitaet Dresden for generously providing computing resources.

Funding

This work was supported by Washington University and the German Research Foundation (DFG), Grant CRC 940, Projects A2 and Z2.

Footnotes

Declaration of Conflicting Interests

The author(s) declared that there were no conflicts of interest with respect to the authorship or the publication of this article.

Supplemental Material

Additional supporting information can be found at http://journals.sagepub.com/doi/suppl/10.1177/2167702620959341

References

- Beleites C, Neugebauer U, Bocklitz T, Krafft C, & Popp J (2013). Sample size planning for classification models. Analytica Chimica Acta, 760, 25–33. doi: 10.1016/j.aca.2012.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Braun U, Plichta MM, Esslinger C, Sauer C, Haddad L, Grimm O, … Meyer-Lindenberg A (2012). Test-retest reliability of resting-state connectivity network characteristics using fMRI and graph theoretical measures. NeuroImage, 59, 1404–1412. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2011.08.044 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao H, Plichta MM, Schäfer A, Haddad L, Grimm O, Schneider M, … Tost H (2014). Test–retest reliability of fMRI-based graph theoretical properties during working memory, emotion processing, and resting state. NeuroImage, 84, 888–900. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2013.09.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chang CC, & Lin CJ (2012). LIBSVM: A library for support vector machines. ACM Transactions on Intelligent Systems and Technology, 2, Article 27. doi: 10.1145/1961189.1961199 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Chein JM, & Schneider W (2012). The brain’s learning and control architecture. Current Directions in Psychological Science, 21, 78–84. doi: 10.1177/0963721411434977 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Cole MW, Braver TS, & Meiran N (2017). The task novelty paradox: Flexible control of inflexible neural pathways during rapid instructed task learning. Neuroscience and Biobehavioral Reviews, 81, 4–15. doi: 10.1016/j.neubiorev.2017.02.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole MW, Ito T, Schultz D, Mill R, Chen R, & Cocuzza C (2019). Task activations produce spurious but systematic inflation of task functional connectivity estimates. NeuroImage, 189, 1–18. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2018.12.054 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole MW, Laurent P, & Stocco A (2013a). Multi-task connectivity reveals flexible hubs for adaptive task control. Nature Neuroscience, 16, 1348–1355. doi: 10.1038/nn.3470 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole MW, Laurent P, & Stocco A (2013b). Rapid instructed task learning: A new window into the human brain’s unique capacity for flexible cognitive control. Cognitive, Affective, & Behavioral Neuroscience, 13, 1–22. doi: 10.3758/s13415-012-0125-7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cole MW, Patrick LM, Meiran N, & Braver TS (2017). A role for proactive control in rapid instructed task learning. Acta Psychologica, 184, 20–30. doi: 10.1016/j.actpsy.2017.06.004 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Collins AGE, Albrecht MA, Waltz JA, Gold JM, & Frank MJ (2017). Interactions among working memory, reinforcement learning, and effort in value-based choice: A new paradigm and selective deficits in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry, 82, 431–439. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2017.05.017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dosenbach NU, Fair DA, Miezin FM, Cohen AL, Wenger KK, Dosenbach RA, … Petersen SE (2007). Distinct brain networks for adaptive and stable task control in humans. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 104, 11073–11078. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0704320104 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- First MB, Spitzer RL, Gibbon M, & Williams JBW (1995). Structured Clinical Interview for DSM-IV Axis I Disorders–Non-Patient Edition (SCID-I/NP, Version 2.0). New York, NY: Biometrics Research Department, New York State Psychiatric Institute. [Google Scholar]

- Glasser MF, Sotiropoulos SN, Wilson JA, Coalson TS, Fischl B, Andersson JL, … Jenkinson M (2013). The minimal preprocessing pipelines for the Human Connectome Project. NeuroImage, 80, 105–124. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.04.127 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Godwin D, Ji A, Kandala S, & Mamah D (2017). Functional connectivity of cognitive brain networks in schizophrenia during a working memory task. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 8, Article 294. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2017.00294 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hampshire A, Daws RE, Neves ID, Soreq E, Sandrone S, & Violante IR (2019). Probing cortical and sub-cortical contributions to instruction-based learning: Regional specialisation and global network dynamics. NeuroImage, 192, 88–100. doi: 10.1016/J.NEUROIMAGE.2019.03.002 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Heinrichs RW, & Zakzanis KK (1998). Neurocognitive deficit in schizophrenia: A quantitative review of the evidence. Neuropsychology, 12, 426–445. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kottaram A, Johnston LA, Cocchi L, Ganella EP, Everall I, Pantelis C, … Zalesky A (2019). Brain network dynamics in schizophrenia: Reduced dynamism of the default mode network. Human Brain Mapping, 40, 2212–2228. doi: 10.1002/hbm.24519 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kriegeskorte N, Simmons WK, Bellgowan PS, & Baker CI (2009). Circular analysis in systems neuroscience: The dangers of double dipping. Nature Neuroscience, 12, 535–540. doi: 10.1038/nn.2303 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Menon V, & Uddin LQ (2010). Saliency, switching, attention and control: A network model of insula function. Brain Structure and Function, 214, 655–667. doi: 10.1007/s00429-010-0262-0 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr H, Wolfensteller U, Betzel RF, Misic B, Sporns O, Richiardi J, & Ruge H (2016). Integration and segregation of large-scale brain networks during short-term task automatization. Nature Communications, 7, Article 13217. doi: 10.1038/ncomms13217 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mohr H, Wolfensteller U, & Ruge H (2018). Large-scale coupling dynamics of instructed reversal learning. NeuroImage, 167, 237–246. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2017.11.049 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moran LV, Tagamets MA, Sampath H, O’Donnell A, Stein EA, Kochunov P, & Hong LE (2013). Disruption of anterior insula modulation of large-scale brain networks in schizophrenia. Biological Psychiatry, 74, 467–474. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2013.02.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Murphy K, Birn RM, Handwerker DA, Jones TB, & Bandettini PA (2009). The impact of global signal regression on resting state correlations: Are anti-correlated networks introduced? NeuroImage, 44, 893–905. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.09.036 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Oishi K, Toma K, Bagarinao ET, Matsuo K, Nakai T, Chihara K, & Fukuyama H (2005). Activation of the precuneus is related to reduced reaction time in serial reaction time tasks. Neuroscience Research, 52, 37–45. doi: 10.1016/J.NEURES.2005.01.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pereira F, Mitchell T, & Botvinick M (2009). Machine learning classifiers and fMRI: A tutorial overview. NeuroImage, 45, S199–S209. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2008.11.007 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power JD, Cohen AL, Nelson SM, Wig GS, Barnes KA, Church JA, … Petersen SE (2011). Functional network organization of the human brain. Neuron, 72, 665–678. doi: 10.1016/j.neuron.2011.09.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Power JD, Mitra A, Laumann TO, Snyder AZ, Schlaggar BL, & Petersen SE (2014). Methods to detect, characterize, and remove motion artifact in resting state fMRI. NeuroImage, 84, 320–341. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2013.08.048 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruge H, & Wolfensteller U (2010). Rapid formation of pragmatic rule representations in the human brain during instruction-based learning. Cerebral Cortex, 20, 1656–1667. doi: 10.1093/cercor/bhp228 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ruge H, & Wolfensteller U (2016). Towards an understanding of the neural dynamics of intentional learning: Considering the timescale. NeuroImage, 142, 668–673. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2016.06.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saykin AJ, Shtasel DL, Gur RE, Kester DB, Mozley LH, Stafiniak P, & Gur RC (1994). Neuropsychological deficits in neuroleptic naive patients with first-episode schizophrenia. Archives of General Psychiatry, 51, 124–131. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schnack HG, & Kahn RS (2016). Detecting neuroimaging biomarkers for psychiatric disorders: Sample size matters. Frontiers in Psychiatry, 7, Article 50. doi: 10.3389/fpsyt.2016.00050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schreiber K, & Krekelberg B (2013). The statistical analysis of multi-voxel patterns in functional imaging. PLOS ONE, 8(7), Article 069328. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0069328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield JM, Kandala S, Burgess GC, Harms MP, & Barch DM (2016). Cingulo-opercular network efficiency mediates the association between psychotic-like experiences and cognitive ability in the general population. Biological Psychiatry: Cognitive Neuroscience and Neuroimaging, 1, 498–506. doi: 10.1016/j.bpsc.2016.03.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield JM, Kandala S, Tamminga CA, Pearlson GD, Keshavan MS, Sweeney JA, … Barch DM (2017). Transdiagnostic associations between functional brain network integrity and cognition. JAMA Psychiatry, 74, 605–613. doi: 10.1001/jamapsychiatry.2017.0669 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sheffield JM, Ruge H, Kandala S, & Barch DM (2018). Rapid instruction-based task learning (RITL) in schizophrenia. Journal of Abnormal Psychology, 127, 513–528. doi: 10.1037/abn0000354 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Supekar K, Cai W, Krishnadas R, Palaniyappan L, & Menon V (2019). Dysregulated brain dynamics in a triple-network saliency model of schizophrenia and its relation to psychosis. Biological Psychiatry, 85, 60–69. doi: 10.1016/j.biopsych.2018.07.020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torrey EF (2002). Studies of individuals with schizophrenia never treated with antipsychotic medications: A review. Schizophrenia Research, 58, 101–115. doi: 10.1016/S0920-9964(02)00381-X [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Waltz JA, & Gold JM (2016). Motivational deficits in schizophrenia and the representation of expected value. Current Topics in Behavioral Neurosciences, 27, 375–410. doi: 10.1007/7854_2015_385 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wechsler D (2001). Wechsler Test of Adult Reading: WTAR. The Psychological Corporation. [Google Scholar]

- Whitfield-Gabrieli S, Thermenos HW, Milanovic S, Tsuang MT, Faraone SV, McCarley RW, … Seidman LJ (2009). Hyperactivity and hyperconnectivity of the default network in schizophrenia and in first-degree relatives of persons with schizophrenia. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences, USA, 106, 1279–1284. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0809141106 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Winkler AM, Ridgway GR, Webster MA, Smith SM, & Nichols TE (2014). Permutation inference for the general linear model. NeuroImage, 92, 381–397. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroimage.2014.01.060 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wolfensteller U, & Ruge H (2012). Frontostriatal mechanisms in instruction-based learning as a hallmark of flexible goal-directed behavior. Frontiers in Psychology, 3, Article 192. doi: 10.3389/fpsyg.2012.00192 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Woodward ND, Rogers B, & Heckers S (2011). Functional resting-state networks are differentially affected in schizophrenia. Schizophrenia Research, 130, 86–93. doi: 10.1016/j.schres.2011.03.010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yarkoni T (2009). Big correlations in little studies: Inflated fMRI correlations reflect low statistical power—Commentary on Vul et al.(2009). Perspectives on Psychological Science, 4, 294–298. doi: 10.1111/j.1745-6924.2009.01127.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.