Abstract

Purpose of Review:

Periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenitis (PFAPA) syndrome is the most common periodic fever syndrome in childhood. Recent studies report genetic susceptibility variants for PFAPA syndrome and the efficacy of tonsillectomy in a broader cohort of patients with recurrent stereotypical fever. In this review, we highlight the findings of these studies and what they may reveal about the pathogenesis of PFAPA.

Recent findings:

Newly identified genetic susceptibility loci for PFAPA suggest that it is a complex genetic disorder and linked to Behçet’s disease and recurrent aphthous ulcers. Patients who have PFAPA with some features of Behçet’s disease have been reported. Moreover, the efficacy of tonsillectomy has now been described in patients who do not meet the full diagnostic criteria for PFAPA, although the immunologic profile in the tonsils is different from those with PFAPA. Factors that predict response to tonsillectomy are also reported.

Summary:

These findings highlight the heterogeneous phenotypes that may be related to PFAPA due to common genetic susceptibility or response to therapy. These relationships raise questions about how to define PFAPA and highlight the importance of understanding of the genetic architecture of PFAPA and related diseases.

Keywords: autoinflammation, PFAPA, periodic fever, tonsillectomy

Introduction

Periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenitis (PFAPA) syndrome is the most common periodic fever syndrome in children. Fever episodes occur with remarkably regular timing, and patients have aphthous ulcers, pharyngitis, or cervical lymphadenitis during flares. Familial clustering has been observed, suggesting that inherited genetic variants may contribute to risk(1, 2). Efforts to identify rare genetic variants associated with the disease through whole exome sequencing and linkage studies have not yielded causative rare mutations (allele frequency of less than 2% in the population) to date, which suggests that PFAPA is not monogenically inherited in most individuals(2). Instead, PFAPA may be a complex genetic disease. Here, we describe recent advances in understanding the genetic risk variants associated with PFAPA and how these link PFAPA to two other ulcerative disorders, Behçet's disease and recurrent aphthous ulcers. We also review new findings on treatment strategies including response to tonsillectomy in more diverse populations.

Genetic risk variants for PFAPA

In complex genetic diseases, multiple genetic mutations, which may be found in high frequency in the general population (“common variants”), contribute to the disease pathogenesis along with environmental factors. By viewing PFAPA as a complex genetic disease, researchers began to search for common variants associated with the disease. The association of aphthous stomatitis or ulcers with PFAPA gave clues regarding the mutations that may be involved. Aphthous ulcers are commonly present during fever flares in children with PFAPA(3, 4). Moreover, recurrent aphthous ulcers are found with higher prevalence among first-degree relatives of children with PFAPA compared to controls without the disease, suggesting that PFAPA and recurrent aphthous ulcers have common risk factors(1).

Behçet's disease is a chronic systemic inflammatory disorder characterized by aphthous ulcers in the mouth and genital ulcers (5, 6). In addition, patients with Behçet's disease may have inflammatory involvement of other organ systems including the eyes, skin, vasculature, gastrointestinal tract, and neurologic system. In the 1970s, class I HLA alleles were found to be significant risk factors for Behçet's disease, and subsequent studies identified HLA-B*51:01 to be the strongest risk allele for Behçet's disease(7-9). Genome wide association studies (GWAS) for Behçet's disease from 2010 to 2017 revealed numerous additional genetic risk variants outside of the HLA locus as well; many of these risk variants are commonly found in the general population but enriched or reduced in frequency in individuals with Behçet’s disease(10-13). A large portion of these risk variants are near genes involved in immunologic pathways, including IL10, IL23R-IL12RB2, STAT4, IL12A, CCR1-3, TLR4, and TNFAIP3, and affect expression of these genes. Rare risk or protective variants (minor allele frequency less than 1%) were also found in the exons of MEFV, TLR4, and IL23R genes as well(14).

In 2019, a GWAS for recurrent aphthous ulcers, involving multiple large cohorts primarily from the United Kingdom and United States, found many genetic risk loci and estimated heritability was about 8%(15). Interestingly, several of the risk variants for recurrent aphthous ulcers are in high linkage disequilibrium with or near the same susceptibility loci for Bechet’s disease. In fact, the most strongly associated risk mutation is near the IL12A gene, and this risk mutation is in strong linkage disequilibrium with a risk variant identified for Behçet’s disease, which suggests that these two variants are inherited together. Similarly, the second strongest associated variant is near IL10, and is also in strong linkage disequilibrium with a risk variant for Behçet’s disease. Risk variants near STAT4 for both Behçet’s disease and recurrent aphthous ulcers are also in high linkage disequilibrium. However, in contrast to Behçet’s disease, both class I and class II HLA risk haplotypes were identified for recurrent aphthous ulcers with the most significant haplotype being a rare class II risk allele (HLA-DRB1*01:03). These HLA risk haplotypes are not as strong risk factors for recurrent aphthous ulcers as the non-HLA risk variants.

Because PFAPA shares phenotypic overlap with recurrent aphthous ulcers and Behçet’s disease, 231 European-ancestry individuals (2 European-American cohorts and 1 Turkish cohort) with PFAPA were screened for risk variants previously associated with Behçet’s disease and/or recurrent aphthous ulcers, which were near the IL12A, IL10, STAT4, IL23R-IL12RB2, CCR1-CCR3, and FUT2 genes. The variants near IL12A, STAT4, IL10, and CCR1-CCR3 were found to also be significantly associated with PFAPA. In particular, the variant near IL12A, which was the most significant association, had an odds ratio (OR) of 2.13 (p=6x10−9), and monocytes from individuals who were heterozygous or homozygous for this variant produced higher levels of the proinflammatory cytokine IL-12 upon stimulation than from those without the risk variant. The variant near IL10 was associated with lower IL-10 production from monocytes(12), while the variant near STAT4 was associated with higher STAT4 expression(11). These variants in sum lead to heightened Th1 and Th17 cell activation, and Th1 activation has been noted in the tonsils and blood of children with PFAPA particularly during flares(16, 17).

In addition, both class I and class II HLA risk types for PFAPA were also identified; the most significant was a class II haplotype consisting of HLA-DQB1*06:03, HLA-DRB1*13:01, and HLA-DQA1*01:03. Interestingly, most of the risk HLA types are unique to PFAPA except HLA-B*15:01, which is a risk allele for recurrent aphthous ulcers as well(15). HLA-B*15 is also a risk allele for Behçet’s disease in those without HLA-B*51(9).

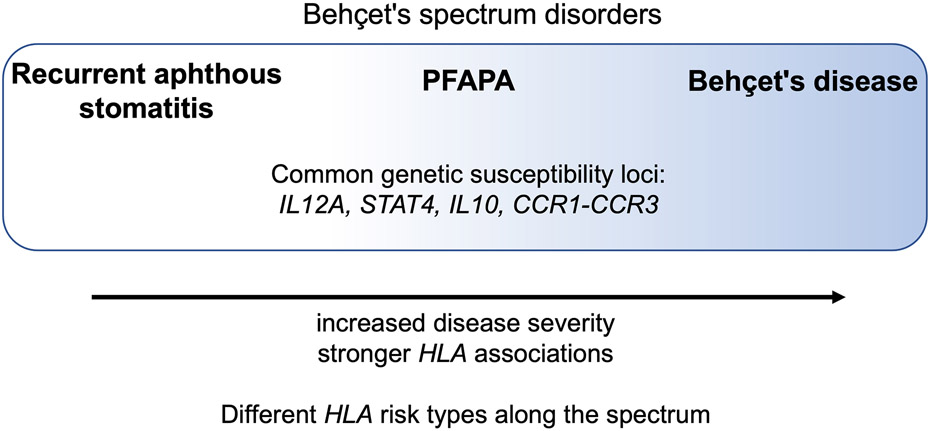

The commonality of genetic risk variants prompted the authors to propose that PFAPA, recurrent aphthous ulcers, and Behçet’s disease are part of common family of inflammatory disease called the Behçet’s spectrum disorders, which are characterized by aphthous ulcers (Figure 1). Recurrent aphthous ulcers are on the mild end of this spectrum, PFAPA is in the middle, and Behçet’s disease is on the severe end. HLA is a stronger risk factor for Behçet’s disease (higher odds ratio), intermediate for PFAPA, and weaker for recurrent aphthous ulcers. Specific HLA types may determine where on the spectrum an individual’s phenotype falls, as HLA risk alleles differ for these three diseases. In clinical practice, patients with features of both PFAPA and Behçet’s disease have been noted, including patients with PFAPA who later develop genital ulcers or pustular rashes during febrile flares(18-21). In addition, adults with Behçet’s disease with PFAPA-like fevers during childhood have been described(22). This disease spectrum ranging from aphthous ulcers to Behçet’s disease allows these patients, some of whom may not meet the full diagnostic criteria for PFAPA or Behçet’s disease, to be better defined and may guide treatment strategies for these patients.

Figure 1.

Genetic susceptibility loci were identified for PFAPA, which are shared with two other ulcerative disease, recurrent aphthous ulcers and Behçet’s disease. This overlap in genetic risk variants suggests that recurrent aphthous ulcers, PFAPA and Behçet’s disease are on a related spectrum of disease. Figure is adapted from: Manthiram K, Preite S, Dedeoglu F, Demir S, Ozen S, Edwards KM, et al. Common genetic susceptibility loci link PFAPA syndrome, Behçet's disease, and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(25):14405-11.

Recently, an ethnic predisposition for PFAPA was found in a cohort of Israeli patients(23). A higher-than-expected proportion of children with PFAPA were of Mediterranean descent (Sephardic Jews or Israeli Arabs) and fewer were of non-Mediterranean descent (Ashkenazi Jews), leading the authors to conclude that Mediterranean ancestry is a risk factor for PFAPA. Moreover, those of Mediterranean descent have earlier disease onset. These findings foster hypotheses of whether particular genetic variants in individuals of Mediterranean descent may contribute to susceptibility for PFAPA as well.

The impact of variants in the MEFV gene, which encodes the pyrin protein, on PFAPA has long been questioned. Homozygous mutations in MEFV, particularly in exon 10, lead to the monogenic periodic fever syndrome, familial Mediterranean fever (FMF). Like PFAPA, children with FMF present with recurrent fever flares, but unlike PFAPA, individuals with FMF have serosal inflammation leading to abdominal pain, chest pain, and arthritis. Populations in the Middle East and around the Mediterranean Sea have a high carrier frequency of pathogenic mutations in MEFV. In Turkish individuals, the pathogenic M694V mutation in MEFV was also found to be a risk mutation for Behçet’s disease(14). Children with clinical features of both PFAPA and FMF who are heterozygous or homozygous for pathogenic MEFV variants have been reported(24). Analysis of 167 Turkish patients diagnosed with PFAPA who underwent genetic testing for mutations in MEFV as part of their clinical care indicated that 43% had mutations in exon 10 of MEFV and 60% had variants in MEFV, most of whom were heterozygous; those with MEFV variants had a later age of onset and shorter episode duration compared to subjects without MEFV mutations(25). No differences in treatment response to colchicine, steroid, and tonsillectomy were observed. Similarly in another Turkish cohort of 157 children, the presence of MEFV variants did not affect clinical features or whether a patient responded to colchicine(26). However, those with MEFV variants had a greater decrease in episode frequency after starting colchicine than those without MEFV mutations.

A deeper understanding of the genetic risk factors for PFAPA syndrome and a comparison of the genetic architecture of recurrent aphthous ulcers, Behçet’s disease, and PFAPA are needed to better define and understand the pathogenesis of these disorders of oral aphthae.

New data on treatment strategies

The main prophylactic medications used to treat PFAPA syndrome are colchicine and cimetidine. Cimetidine is a histamine receptor 2 (H2R) antagonist primarily used as an antacid, but blockage of histamine also has immunologic effects including heightened Th1 cell activation and decreased IL-10 production in addition to fewer B cells and CD25+ T cells(27, 28). How these effects lead to fewer PFAPA episodes requires further study(29). On the other hand, colchicine suppresses pyrin-inflammasome activation(30). Due to its efficacy in patients with FMF, it has been studied in PFAPA as well(31-33). Additional studies over the past two years showed that colchicine reduces the frequency of flares in children with PFAPA(25, 26, 34, 35). In one of these, 67 Iranian children were randomly assigned to either prophylaxis with colchicine or cimetidine; both of these prophylactic agents were found to have similar efficacy(35).

IL-1β inhibition is effective in many periodic fever syndromes in which inflammasome activation and excess IL-1β production are central to the pathogenesis. A small number of studies reported the efficacy of IL-1β inhibitory agents such as anakinra and canakinumab in patients with PFAPA(36). When given at the onset of flares, anakinra led to clinical improvement in all patients, but two had relapse of fever after 1 or 2 days(17). Canakinumab and daily anakinra were reported to reduce the frequency of flares in an adult-onset case(37); however, in a child who was heterozygous for the M694V variant in MEFV and did not respond well to colchicine, canakinumab was only transiently effective in preventing flares(36).

Tonsillectomy has been shown in several observational studies(38) and two randomized controlled trials(39) to lead to episode resolution in most children with PFAPA. Nevertheless, patients with incomplete response to tonsillectomy have been noted. Recent studies have expanded our understanding of the characteristics of patients who respond to tonsillectomy. From a cohort of 53 children in Japan with PFAPA who underwent tonsillectomy, 39 (74%) had complete resolution of flares following their surgery(40). Patients with late age of onset and headache were more likely to have a full response to tonsillectomy (lack of arthralgia was also a predictive factor in the univariate analysis but was not significant in a multivariable analysis). Another study of Turkish patients with PFAPA showed that those with concomitant FMF and PFAPA were significantly less likely to respond to tonsillectomy than those with PFAPA alone(41). These differences in tonsillectomy efficacy based on symptoms suggest that subgroups of PFAPA may have differences in their pathogenesis and involvement of the tonsils. Perhaps particular genetic risk variants that have specific functional significance in the tonsils play a role.

Regrowth of the tonsillar tissue is also proposed to play a role in those with continued symptoms after tonsillectomy(42). Five (5%) of 94 children in Finnish cohort had continued flares after tonsillectomy; most of these 5 patients had relapse of symptoms years after tonsillectomy. Four of these 5 (80%) children had regrowth of the tonsil tissue compared to 19/89 (21%) of those with complete resolution who experienced regrowth.

On the other hand, tonsillectomy was also recently shown to be effective in 15 patients with recurrent fevers who did not fully meet the criteria for PFAPA. These patients were termed as having “SURF” or syndrome of undifferentiated recurrent fever; some had features of PFAPA such as pharyngitis, cervical adenitis, and aphthous ulcers during flares. However, the immunologic profile of the tonsils of SURF patients had differences from those of patients with PFAPA including a stronger IL-1 signature. In another study, 50 patients with “incomplete PFAPA” who had episodes starting after 5 years of age or who did not have aphthous ulcers, adenitis, or pharyngitis during flares similarly had an excellent response to tonsillectomy(43). The efficacy of tonsillectomy in these patients indicates that even patients who do not meet the full diagnostic criteria for PFAPA may have some overlap in pathogenesis. As PFAPA is a complex genetic disease, heterogeneity in clinical features would be expected. Characterizing risk variants for both PFAPA and SURF and understanding whether particular risk variants may predict response to tonsillectomy may shed light on differences and similarities in their pathogenesis. Interestingly, tonsillectomy alone lead to complete episode resolution in two cohorts of patients with PFAPA(42, 44), suggesting that adenoidectomy may not been needed and that the adenoids do not play as significant of a role in disease pathogenesis.

Another factor to consider in the pathogenesis of complex genetic disorders and particularly in these diseases involving the oropharyngeal mucosa are environmental exposures including the microbiome. A recent analysis of 20 children with PFAPA who received probiotics revealed that the frequency and severity of flares was lower after starting Lactobacillus-based probiotics(45).

Conclusion

To date, PFAPA has been diagnosed based on clinical features alone, initially using the diagnostic criteria proposed by Marshall and Edwards(4) and, more recently, using classification criteria developed and validated by experts(46, 47). The studies reviewed here indicate overlap in the pathogenesis of PFAPA, Behçet’s disease, recurrent aphthous ulcers as well as the efficacy of tonsillectomy in heterogeneous patient populations, raising questions about how to define PFAPA. Further understanding of genetic risk factors will play an important role in understanding how to define PFAPA and how those with PFAPA-like disease manifestations are related to those with more classic disease.

Key points:

PFAPA is a complex genetic disease with risk mutations near the IL12A, IL10, STAT4, and CCR1-CCR3 genes as well has class I and class II HLA risk alleles.

PFAPA shares genetic risk variants with Behçet’s disease and recurrent aphthous ulcers.

Tonsillectomy is efficacious in children with periodic fevers that do not fully meet the diagnostic criteria for PFAPA, but is more effective in children with particular clinical features.

Footnotes

Financial Support or Sponsorship: Kalpana Manthiram was supported by the Intramural Research Program of the National Institute of Allergy and Infectious Diseases at the National Institutes of Health.

Conflicts of Interest: There are no conflicts of interest.

References:

- 1.Manthiram K, Nesbitt E, Morgan T, Edwards KM. Family History in Periodic Fever, Aphthous Stomatitis, Pharyngitis, Adenitis (PFAPA) Syndrome. Pediatrics. 2016;138(3):e20154572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Di Gioia SA, Bedoni N, von Scheven-Gête A, et al. Analysis of the genetic basis of periodic fever with aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenitis (PFAPA) syndrome. Sci Rep. 2015;5:10200. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thomas KT, Feder HM Jr., Lawton AR, Edwards KM. Periodic fever syndrome in children. J Pediatr. 1999;135(1):15–21. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Marshall GS, Edwards KM, Lawton AR. PFAPA syndrome. Pediatr Infect Dis J. 1989;8(9):658–9. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.The International Criteria for Behçet's Disease (ICBD): a collaborative study of 27 countries on the sensitivity and specificity of the new criteria. J Eur Acad Dermatol Venereol. 2014;28(3):338–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Criteria for diagnosis of Behçet's disease. International Study Group for Behçet's Disease. Lancet. 1990;335(8697):1078–80. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Ohno S, Aoki K, Sugiura S, et al. Letter: HL-A5 and Behçet's disease. Lancet. 1973;2(7842):1383–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Takemoto Y, Naruse T, Namba K, et al. Re-evaluation of heterogeneity in HLA-B*510101 associated with Behçet's disease. Tissue Antigens. 2008;72(4):347–53. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Ombrello MJ, Kirino Y, de Bakker PI, et al. Behçet disease-associated MHC class I residues implicate antigen binding and regulation of cell-mediated cytotoxicity. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2014;111(24):8867–72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Takeuchi M, Mizuki N, Meguro A, et al. Dense genotyping of immune-related loci implicates host responses to microbial exposure in Behçet's disease susceptibility. Nat Genet. 2017;49(3):438–43. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Kirino Y, Bertsias G, Ishigatsubo Y, et al. Genome-wide association analysis identifies new susceptibility loci for Behçet's disease and epistasis between HLA-B*51 and ERAP1. Nat Genet. 2013;45(2):202–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Remmers EF, Cosan F, Kirino Y, et al. Genome-wide association study identifies variants in the MHC class I, IL10, and IL23R-IL12RB2 regions associated with Behçet's disease. Nat Genet. 2010;42(8):698–702. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mizuki N, Meguro A, Ota M, et al. Genome-wide association studies identify IL23R-IL12RB2 and IL10 as Behçet's disease susceptibility loci. Nat Genet. 2010;42(8):703–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Kirino Y, Zhou Q, Ishigatsubo Y, et al. Targeted resequencing implicates the familial Mediterranean fever gene MEFV and the toll-like receptor 4 gene TLR4 in Behçet disease. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2013;110(20):8134–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Dudding T, Haworth S, Lind PA, et al. Genome wide analysis for mouth ulcers identifies associations at immune regulatory loci. Nat Commun. 2019;10(1):1052. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dytrych P, Krol P, Kotrova M, et al. Polyclonal, newly derived T cells with low expression of inhibitory molecule PD-1 in tonsils define the phenotype of lymphocytes in children with Periodic Fever, Aphtous Stomatitis, Pharyngitis and Adenitis (PFAPA) syndrome. Mol Immunol. 2015;65(1):139–47. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Stojanov S, Lapidus S, Chitkara P, et al. Periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis (PFAPA) is a disorder of innate immunity and Th1 activation responsive to IL-1 blockade. Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences. 2011;108(17):7148–53. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *18. Manthiram K, Preite S, Dedeoglu F, et al. Common genetic susceptibility loci link PFAPA syndrome, Behçet's disease, and recurrent aphthous stomatitis. Proc Natl Acad Sci U S A. 2020;117(25):14405–11. This study reports genetic susceptibility loci for PFAPA syndrome and reveals genetic commonality between recurrent aphthous ulcers, PFAPA, and Behcet’s disease.

- 19.Wurster VM, Carlucci JG, Feder HM Jr., Edwards KM. Long-term follow-up of children with periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenitis syndrome. J Pediatr. 2011;159(6):958–64. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Scattoni R, Verrotti A, Rinaldi VE, et al. Genital ulcer as a new clinical clue to PFAPA syndrome. Clin Exp Dermatol. 2015;40(3):286–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lin CM, Wang CC, Lai CC, et al. Genital ulcers as an unusual sign of periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngotonsillitis, cervical adenopathy syndrome: a novel symptom? Pediatr Dermatol. 2011;28(3):290–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Cantarini L, Vitale A, Bersani G, et al. PFAPA syndrome and Behçet's disease: a comparison of two medical entities based on the clinical interviews performed by three different specialists. Clin Rheumatol. 2016;35(2):501–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *23. Amarilyo G, Harel L, Abu Ahmad S, et al. Periodic Fever, Aphthous Stomatitis, Pharyngitis, and Adenitis Syndrome – Is It Related to Ethnicity? An Israeli Multicenter Cohort Study. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2020;227:268–73. This study reports an ethnic predisposition to PFAPA among patients of Mediterranean origin in Israel.

- 24.Butbul Aviel Y, Harel L, Abu Rumi M, et al. Familial Mediterranean Fever Is Commonly Diagnosed in Children in Israel with Periodic Fever Aphthous Stomatitis, Pharyngitis, and Adenitis Syndrome. The Journal of Pediatrics. 2019;204:270–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Yildiz M, Adrovic A, Ulkersoy I, et al. The role of Mediterranean fever gene variants in patients with periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis syndrome. European Journal of Pediatrics. 2021;180(4):1051–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Otar Yener G, Aktaş İ, Altıntaş Meşe C, Çakan M. Does having MEFV gene sequence variants affect the clinical course and colchicine response in children with PFAPA syndrome? European Journal of Pediatrics. 2023;182(1):411–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Elenkov IJ, Webster E, Papanicolaou DA, et al. Histamine Potently Suppresses Human IL-12 and Stimulates IL-10 Production via H2 Receptors. The Journal of Immunology. 1998;161(5):2586–93. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Meghnem D, Oldford SA, Haidl ID, et al. Histamine receptor 2 blockade selectively impacts B and T cells in healthy subjects. Scientific Reports. 2021;11(1):9405. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Feder HM, Salazar JC. A clinical review of 105 patients with PFAPA (a periodic fever syndrome). Acta Paediatr. 2010;99(2):178–84. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Park YH, Wood G, Kastner DL, Chae JJ. Pyrin inflammasome activation and RhoA signaling in the autoinflammatory diseases FMF and HIDS. Nat Immunol. 2016;17(8):914–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Butbul Aviel Y, Tatour S, Gershoni Baruch R, Brik R. Colchicine as a therapeutic option in periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, cervical adenitis (PFAPA) syndrome. Semin Arthritis Rheum. 2016;45(4):471–4. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Dusser P, Hentgen V, Neven B, Koné-Paut I. Is colchicine an effective treatment in periodic fever, aphtous stomatitis, pharyngitis, cervical adenitis (PFAPA) syndrome? Joint Bone Spine. 2016;83(4):406–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Tasher D, Stein M, Dalal I, Somekh E. Colchicine prophylaxis for frequent periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and adenitis episodes. Acta Paediatr. 2008;97(8):1090–2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Quintana-Ortega C, Seoane-Reula E, Fernández L, et al. Colchicine treatment in children with periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenitis (PFAPA) syndrome: A multicenter study in Spain. Eur J Rheumatol. 2020;8(2):73–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Raeeskarami SR, Sadeghi P, Vahedi M, et al. Colchicine versus cimetidine: the better choice for Periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, adenitis (PFAPA) syndrome prophylaxis, and the role of MEFV gene mutations. Pediatric Rheumatology. 2022;20(1):72. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Soylu A, Yıldız G, Torun Bayram M, Kavukçu S. IL-1β blockade in periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and cervical adenitis (PFAPA) syndrome: case-based review. Rheumatology International. 2021;41(1):183–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Lopalco G, Rigante D, Vitale A, et al. Canakinumab efficacy in refractory adult-onset PFAPA syndrome. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. 2017;20(8):1050–1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Licameli G, Lawton M, Kenna M, Dedeoglu F. Long-term surgical outcomes of adenotonsillectomy for PFAPA syndrome. Arch Otolaryngol Head Neck Surg. 2012;138(10):902–6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Burton MJ, Pollard AJ, Ramsden JD, et al. Tonsillectomy for periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis and cervical adenitis syndrome (PFAPA). Cochrane Database Syst Rev. 2019;12(12):Cd008669. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *40. Hara M, Morimoto N, Watabe T, Morisaki N, et al. Can the effectiveness of tonsillectomy for PFAPA syndrome be predicted based on clinical factors. International Journal of Rheumatic Diseases. 2023;26(3):480–6. This study assessed predictors of response to tonsillectomy and found that children with late age of onset and headache had a more complete response.

- 41.Gozen ED, Yildiz M, Kara S, et al. Long-term efficacy of tonsillectomy/adenotonsillectomy in patients with periodic fever aphthous stomatitis pharyngitis adenitis syndrome with special emphasis on co-existence of familial Mediterranean fever. Rheumatology International. 2023;43(1):137–45. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Lantto U, Koivunen P, Tapiainen T, Renko M. Periodic Fever, Aphthous Stomatitis, Pharyngitis, and Cervical Adenitis Syndrome: Relapse and Tonsillar Regrowth After Childhood Tonsillectomy. The Laryngoscope. 2021;131(7):E2149–E52. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Lantto U, Koivunen P, Tapiainen T, Renko M. Long-Term Outcome of Classic and Incomplete PFAPA (Periodic Fever, Aphthous Stomatitis, Pharyngitis, and Adenitis) Syndrome after Tonsillectomy. J Pediatr. 2016;179:172–7.e1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- *44. Luu I, Sharma A, Guaderrama M, et al. Immune Dysregulation in the Tonsillar Microenvironment of Periodic Fever, Aphthous Stomatitis, Pharyngitis, Adenitis (PFAPA) Syndrome. J Clin Immunol. 2020;40(1):179–90. This study showed efficacy of tonsillectomy in 15 children with periodic fever syndromes that did not meet the criteria for PFAPA. The tonsils of these individuals, however, had distinct immunologic features from those of children with PFAPA.

- 45.Batu ED, Kaya Akca U, Basaran O, et al. Probiotic use in the prophylaxis of periodic fever, aphthous stomatitis, pharyngitis, and adenitis (PFAPA) syndrome: a retrospective cohort study. Rheumatology International. 2022;42(7):1207–11. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Vanoni F, Caorsi R, Aeby S, et al. Towards a new set of classification criteria for PFAPA syndrome. Pediatric Rheumatology. 2018;16(1):60. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Gattorno M, Hofer M, Federici S, et al. Classification criteria for autoinflammatory recurrent fevers. Annals of the Rheumatic Diseases. 2019;78(8):1025–32. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]