ABSTRACT

The physician associate (PA) profession is relatively new to the British NHS. Little research has been conducted on the facilitators to integrating these new health professionals into a secondary care service. Thus, a grounded theory qualitative study was conducted. PAs who were educated in the UK and were the first PA in their secondary care service were interviewed, as well as doctors who were on the team when the PA started. Ten facilitators were identified, comprising three facilitator themes: PA involvement in role and skill development is crucial; having a champion for the PAs promotes integration; and principled behaviour by the PA allows the role to develop safely and effectively. Having a clearly defined role for the PA is the primary facilitating factor. This research identified approaches that both PAs and hospital trusts can implement to facilitate the introduction of PAs to secondary care services in the NHS.

KEY WORDS: Physician associate, physician assistant, UK, workforce innovation

Introduction

The physician associate (PA) profession was developed in the USA (where it is called the ‘Physician Assistant’ profession) during the 1960s to address a medical workforce shortage. The PA profession, although well established in the USA, is relatively new to the UK. The first British PA programmes were established during the mid-2000s and, by 2021, nearly 2500 PAs were listed on the Faculty of Physician Associates Managed Voluntary Register.1 Many newly graduated PAs enter secondary care employment either out of preference for secondary care or because they have had their education funded by hospital trusts eager for more medical providers.2 Given the youth of the profession, little is known about how PAs are integrated into medical teams in UK secondary care settings. Two pilot project evaluations were conducted during the mid-2000s, which evaluated incorporating very experienced US-trained PAs into secondary care in the UK.3,4 Both studies found that experienced US PAs were able to make a valuable contribution to the needs of secondary care services by providing safe medical care and increased continuity of care. Drennan and colleagues conducted a mixed-methods study of UK-educated PAs in the hospital setting in 2018. This study found that participants believed PAs were accepted by other members of the healthcare team, that they improved patient flow and continuity of care, and that their presence allowed for more teaching time for junior doctors.5

Our study sought to establish which factors were specific facilitators and barriers to the integration of the first UK-educated PAs in a secondary care service in the NHS. The first PA in a trust faces the challenge of both introducing a new role and becoming the exemplar for that new role. This study interviewed PAs who were the first PA on their secondary care service and doctors who worked with them, to characterise the barriers and facilitators these teams faced when recruiting a PA. In this paper, we report on the facilitators to the integration of the first PA in a clinical service.

Methods

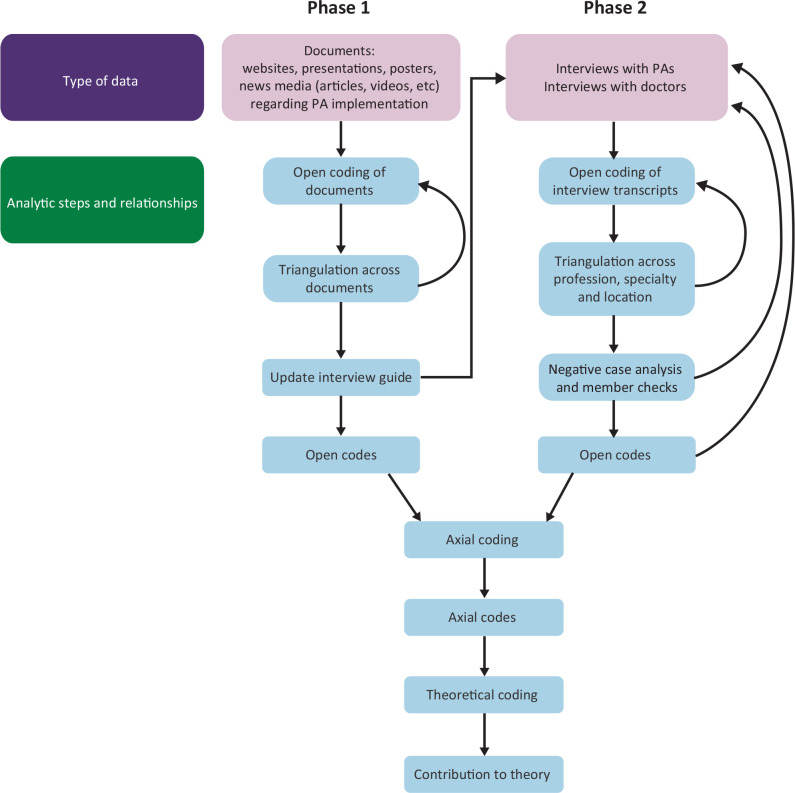

This study used a grounded theory qualitative approach to the research question, with the goal of developing a framework that will inform future larger scale quantitative research. Given that the integration of British PAs into secondary care services had not yet been well described in the literature, any survey using closed-ended questions would likely have failed to capture the needed information. Standard qualitative methodology was used to conduct this study (Fig 1). Grounded theory methodology uses an iterative approach to the data collected, with earlier review of materials and earlier interviews influencing the selection of topics discussed with subsequent interview participants to obtain more detailed information about themes raised by earlier interviewees.

Fig 1.

Data collection and analysis model. PA=physician associate.

Research ethics approval was obtained from the Research Ethics Committee at St George's, University of London and the Institutional Review Board at the George Washington University School of Medicine. Participants were recruited via emails sent to the UK PA programmes that had graduated PAs before January 2018, social media posts and word of mouth. PAs were recruited first. These PAs were then asked to approach a doctor with whom they had worked at the time they began practice. All of these doctors were also currently working with the PAs in the study. Consent was obtained from both the PA and the doctor before entering the pair into the study. Teams from a variety of medical and surgical specialties were recruited to maximise variations in experience (Table 1). At the time of the study, there were no UK-educated PAs working in Wales or Northern Ireland. Attempts to recruit Scottish participants were unsuccessful.

Table 1.

Characteristics of physician associate–doctor participant teams

| Specialty | Location | PA gender | Doctor rank/gender | Group versus solo PA |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Medical | SE England | Female | Consultant/male | Solo |

| SE England | Female | Consultant/male | Solo | |

| NW England | Male | Consultant/male | Solo | |

| SE England | Female | Registrar/male | Group | |

| SE England | Female | Consultant/male | Group | |

| Surgical | SE England | Female | Registrar/male | Solo |

| SW England | Male | Registrar/male | Solo | |

| SE England | Female | Registrar/female | Group |

PA = physician associate.

Inclusion criteria were based on the PA's status. To participate, the PA must have been the first PA or part of the first group of PAs to be employed in a particular secondary care setting. The PA must also have undertaken their PA studies in the UK and started their employment within the past 5 years. The PAs were asked to recruit a consultant or a very senior trainee doctor with whom they had worked at the time they started on the service. Junior doctors were not eligible. PAs and doctors were offered a £10 gift card as an incentive to participate. Seven PA–doctor pairs were eventually enrolled in the study as well as one group of one doctor with two PAs. This group was enrolled to increase the potential for a negative case analysis because these two PAs started at the same time, but one of the two PAs left employment on that service after only ∼1 year. Four potential participants (PAs) could not find a doctor eligible to participate and, thus, were not interviewed. Participants were informed that the Principal Investigator (PI) is a PA who has worked in secondary care and that this research was part of her work for a PhD.

The PI interviewed each participant separately for 30–50 min using a semi-structured interview guide, which had been pilot tested before initiation. Interviews were conducted in an online videoconference, audio recorded and subsequently transcribed by a UK transcription service that complies with data protection laws. Transcripts were independently coded by two investigators using standard three-level grounded theory methodology (open, axial and theoretical coding). Coding of data using NVivo 116 began immediately after the first interview and themes from early interviews were explored in greater depth with later interviewees. Interviewing new pairs continued until later interviews stopped revealing new themes.

Standard quality assurance methods for qualitative research were used to improve the trustworthiness of the data. These included triangulation with other data sources, confidential interviews, piloting of the semi-structured interview guide, multiple data coders, negative case analysis and purposive sampling for maximum variation among participant characteristics, such as specialty, region of the country and whether the PA had been hired as a lone PA or as part of a group of PAs.

Results

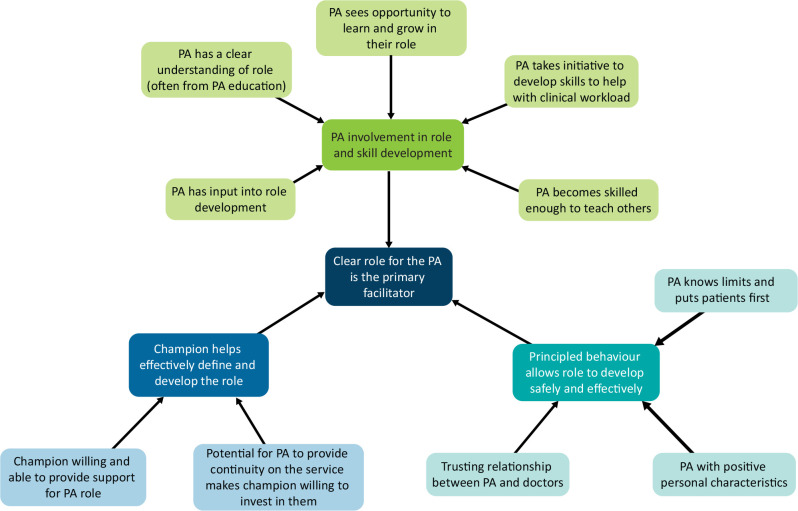

Ten concepts emerged from the data collected, which were grouped into three facilitator themes. Each of these three themes support the overall conclusion that a clear role for the PA on the service is the primary facilitator to the effective integration of the secondary care PA (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Facilitators to the integration of the first physician associates (PAs) into a secondary care service in the NHS.

The three themes comprised the following facilitators:

-

PA involvement in role and skill development facilitates the deployment of PAs (see Table 2 for supporting data)

The PA has some say in the development of the role.

PAs have a clear understanding of the PA role and can communicate that to others.

PA sees opportunity to learn and grow in their role.

PA takes the initiative to develop skills that help the team with clinical workload.

PA becomes skilled enough to teach others.

-

A champion who helps effectively define and develop the role facilitated integration of PAs (data in Table 3)

Champion is willing and able to provide support for the PA role.

The potential for PAs to provide continuity of the service makes champions willing to invest in them.

-

Principled behaviour on the part of PAs allows the role to develop safely and effectively (data in Table 4)

PA knows limits and puts patient safety first.

Positive personal characteristics help the team accept the PA.

A trusting relationship between PAs and doctors enables them to work together effectively.

Table 2.

PA involvement in role and skill development facilitates the deployment of PAs

| Facilitator | Data |

|---|---|

| PA has some say in the development of the role | Whereas some PAs had little say over how their role would be developed, others had substantial input: Surg PA 17 – ‘At the end of the first day we sat with our consultant and explained to him what our interest in [specialty] would be and the role was tailored to that for us.’ |

| A medicine PA worked with a doctor who had previously worked with PAs and sought the PA's input into their new team structure. The PA was asked whether they had any resistance to their efforts to mould the role. They responded: | |

| Med PA 96 – ‘No, and I think that's partly because the consultant who was in charge of the inpatient team at that time is the one consultant who'd worked with a PA before, at [another hospital]. Yes, she vaguely knew what PAs were about and so she had said, ‘What would you rather do?’’ | |

| PAs have a clear understanding of the PA role and can communicate that to others | PAs recognised quickly that it was up to them to be able to explain the scope of their role well to members of the healthcare team: Surg PA 28 – ‘I think the doctors, a lot of them didn't know what to expect. I think I've shown them, [over time], what I am able to learn and take on...I've been very vocal about how I want to progress. I think the doctors are very much in support of that and so I think they're happy to teach me and train me.’ |

| PA sees opportunities to grow in their role | One PA who went from simply attending ward rounds with the team to eventually running her own outpatient rapid-access clinic for specialty consultations illustrated this concept: |

| Med PA 85 – ‘Compared to now, I was a lot more dependent on the doctors then. I was only a year out of university, so each morning I would do the rounds with them, kind of being more of a scribe [on the inpatient service] and just a presence rather than seeing patients on my own. I think that reflected my level. I wasn't seeing any outpatients. I started in [month], and initially we would review the inpatients in the morning, and, in the afternoon you do the jobs, and organising investigations, and paperwork and things. It was fairly shortly after that [consultant] start talking about setting up a rapid access clinic.’ | |

| PA takes initiative to develop skills that help the team | PAs felt that, if they took the initiative to learn more skills, that would be rewarded by increase of scope of practice and trust and appreciation from their team. |

| Surg PA 17 – ‘For example [invasive procedure G], on the PA course we weren't really trained how to do that. When we got into the role we said, ‘It's [Specialty], in a day we could have four [invasive procedure G]. For one doctor that's a lot. If you teach me how to do this, that's you doing two and that's me doing two.’’ | |

| ‘People were eager to teach us. ‘Okay, cool. I've seen her debride a wound. I've seen her suture a wound. I've seen her do other things, so clearly they have the capability of learning how to do this.’ People were even eager to teach us, so that they could rely on us more.’ | |

| PAs become skilled enough to teach others | Two PAs really enjoyed teaching junior doctors and felt that it gave them credibility with the team. Med PA 74 – ‘I'm known as the person who does the lumbar punctures, and I've started training the junior doctors when they come round, and they know that I've been there for a couple of years, and I'm looked at as somebody more trusted.’ |

| Surgeon A – ‘The other thing I had realised later on ... is that they became the trainers of the SHOs. So with the new SHOs joining in, the department would pair them up with the PAs because they then had a full knowledge of the SHO duties... and that was incredibly useful.’ |

med = medical; PA = physician associate; surg = surgical.

Table 3.

A champion who helps effectively define and develop the role facilitates integration of physician associates

| Facilitator | Data |

|---|---|

| PAs have a champion who is willing and able to provide support and advocacy | Consultants felt that it was their duty to model acceptance and advocacy for their PAs to their junior doctors. Physician G – ‘I hope that we modelled that acceptance by the fact that the consultants all treated [PA] with respect, as an important member of the team. We all thought it was a great appointment and she was going to be great and the idea was great. I'm hoping that we modelled that to the junior medical staff because they saw us treating [PA] as a respected, important member of the team, that they would do the same.’ |

| Med PA 96 – ‘I think, now that we've all worked with more of the consultants for quite a period of time, they're able to introduce us better. I think the fact that they are happy and used to working with us has a bit of a knock-on effect in front of the others.’ | |

| Potential for PA to provide continuity on the service makes champions willing to invest in them | Consultants find that the constant churn of junior doctors is a poor fit for wards that care for patients with long-term chronic disease and that PAs are a better fit because they do not rotate away. Physician H – ‘We are developing inpatient specialist diabetes [care]. Typically, the junior doctors rotate within the blink of an eye. Whereas diabetes is a long-term condition and [we get] benefits from [medical practitioners] who spend a bit longer. They get a more in-depth understanding. So we were quite keen to have the physician associate. I imagine that if she didn't like our particular specialty, she does have some choice of moving. So, by definition, if they stay, it's because they have chosen to.’ |

med = medical; PA = physician associate.

Table 4.

Principled behaviour on the part of physician associates allows the role to develop safely and effectively

| Facilitator | Data |

|---|---|

| PAs know their limits and put patient safety first | PAs discussed how they built trust by having a low threshold for consulting doctors early in their time in the post. |

| Med PA 85 – ‘I am not sure if it's my personality, but I am quite cautious. In running things by [the doctors] and being extra specially safe and wary about any patient I am not happy with. I think over time people acknowledge that and then recognise you've got a pretty good clinical safety record. Being ultra-cautious from the beginning of your career results in [the doctors] trusting. That's eventually rewarded by, if you do have a worry about patients and you flag up your concerns, then they will absolutely take it seriously. [My PA programme] banged [patient safety] into us for the whole course. It is so important as a PA to know your scope and know your limits.’ | |

| Positive personal characteristics help the team accept the PA | Both PAs and doctors recognised how positive personal traits, such as humility, friendliness, being hard working and having strong communication skills, helped them integrate into the team: |

| Physician D – ‘These are maybe soft skills, but [the PAs have good] communication. They come out and say ‘I understand why we did this. I don't understand why we did that’. So it shows you ‘Okay – they are thinking about what's happening rather than just filling in forms or making requests, etc.’’ | |

| Physician G – ‘She's unassuming yet very capable. She doesn't put anyone's backs up. She just gets on with stuff... She's made a big impact on the team, on how well people get [along] together. I think she contributes more there than we'd anticipated.’ | |

| Med PA 74 – ‘Be keen and enthusiastic. Be humble in your role, and ask questions, show that you're interested on ward rounds. Go to one of your seniors if you have any problems, or any questions, and gain that trust from them. Be keen on doing procedures. Be keen on having difficult conversations with patients, and patients' relatives. Be confident, but not over-confident.’ | |

| A trusting relationship between PAs and doctors enables them to work together effectively | A surgeon outlined the factors that had led them to trust their PAs. Surgeon A – ‘Let's say I am at home, and I want to know something about the patient. Nine times out of ten, I would call one of [the PAs] rather than call the SHOs. Perhaps, partially because the SHOs rotate and are new to the job, but also partly because I know that if I ask [the PAs] it will be done, and I do not have to check whether it has been done and documented. I know for a fact. The personal relationship that you have them that is part of this trust; not only their competence, but just that you know their character. They are going to tell you the truth.’ |

med = medical; PA = physician associate.

The theoretical code that emerged from these data was that a clear role for the PA is the primary facilitator to successful integration into a secondary care service (Fig 2).

Discussion

This qualitative study of PA–doctor teams offers insights into the factors that enable NHS trusts to introduce the PA more effectively to secondary care teams. We found that having a clear role for the PA on the team was the primary facilitator to integration of the PA in the team. To develop this role, it is helpful to have PAs involved in the process of delineating the PA's responsibilities and the ways in which the PA will interact with the team. This process is made easier when the PA has a clear understanding of their knowledge and limits and when there is a doctor willing to be a proactive champion for individual PAs and for the PA role within the institution. PAs can increase the acceptance of their role by exhibiting desirable personal characteristics, such as humility, service to the team and an awareness of their own limitations, and by working hard to develop advanced clinical skills, which will benefit both patients and the secondary care team. In turn, PAs provided several benefits to the team, most prominently continuity of care that junior doctors cannot provide, given their frequent rotation. Senior doctors felt their investments in training PAs and developing trust with them yielded fruit for years instead of months, which increased their interest in having PAs on their team.

Although several of the findings of this study are consistent with previous literature on PAs both in the UK and abroad, a few findings in this study were new. A crucial finding new to the literature is that having opportunities to grow and learn in their role is a key facilitator of PA practice. When PAs took the initiative to develop skills they thought would be valuable, doctors noted this with appreciation. Learning new skills set up a beneficial cycle. PAs noted that demonstrating facility with one skill often increased the willingness of doctors to train them further. PAs claimed the medical identity through undertaking tasks previously only performed by doctors, such as invasive procedures or breaking bad news to patients. Given that doctors could see how training the PAs reduced their own workload, they became even more willing to educate the PAs further. Although this finding is new in the PA literature, research has found that employees are motivated by development opportunities.7 It will be interesting to observe over time just how motivating these factors are for PAs.

The finding that PAs integrate into the team more effectively when they have some input into the development of their particular role is also new in this population. However, it is more likely that no one has asked this specific question before, rather than that this finding is novel. Ritsema and Roberts obliquely touched on the degree of satisfaction that PAs have with their ‘freedom to choose my own way of working’ in their paper on PA job satisfaction.8 Literature on employee motivation more generally has demonstrated that highly educated professionals strongly value having input into the content and structure of their work.9

The importance of the ability of PAs to communicate their role clearly to others has previously been reported. Multiple studies have shown that PAs need to understand, and be able to articulate, their role to patient and other NHS workers. They cannot rely on others to know that they expect to be contributing as a member of the medical team and, thus, need to advocate for themselves.10 Most PAs were able to make their expectations for their roles clear to the members of the team, but a few PAs struggled to get their teams to view the role the same way they did, and had their scope of practice restricted because of these misunderstandings.

A few studies, including this one, have begun to demonstrate that PAs can become skilled enough on a service to begin to be able to train others, including medical students and junior doctors.5 Initially, PAs needed a lot of help from junior doctors, but, over time, the direction of training often reversed. PAs become the experts on the needs of the patients in the services on which they work, often for years. Trainees rotating through these services then benefit from the knowledge and skills of the PAs and, as future consultants, are introduced to the PA role. The importance of having a champion for PAs within the hospital trust and the finding that champions are willing to invest in PAs because they reap the benefit of their investment in the continuity of care have both been described in previous studies.4–5,11 Champions smoothed the path for the PAs in many ways: administratively, socially and educationally. Crucially, champions used their own credibility to help the PAs increase their own credibility with the medical teams and hospital staff.

The current study reinforced findings related to the effects of prosocial and ethical behaviour of PAs. A key concept in the establishment of the PA profession in the USA 50 years ago was that PAs would be trained explicitly to know the limits of their medical knowledge and seek help when needed.12 In this study, PAs and doctors alike spoke about the need to establish trust. PAs worked to establish this trust by knowing their limits, telling the truth, working diligently to expand their medical knowledge and being willing to do less-glamorous ward tasks. These findings are consistent with studies by Williams and by Theodoraki in which doctors noted how the strong communication skills of PAs increased their willingness to have them on their clinical team.13,14 PAs in this study had often been instructed in these prosocial behaviours by the leadership of their PA programmes.

These findings should assist both those considering recruiting PAs and PAs themselves. As hospital trusts consider adding PAs, they should determine exactly how PAs might help fulfil the needs of their services. PAs are not the answer to every workforce issue in the hospital. It might be advisable to recruit other health professionals instead. Hospital trusts or doctors considering adding a PA to the team would be advised to consult experienced PAs and PA educators about their plans to ensure that the envisioned role is appropriate for a PA. Hospital trusts also need to identify doctors to be PA champions, to be the face of the PA initiative and to give the PAs a source of help. PAs who are new to a service need to take the initiative to continue to develop their medical knowledge and clinical skills. They need to prioritise patient safety in all their work. PAs need to be willing to sometimes do unglamorous tasks, which will help them establish credibility with their teams. They need to capitalise on their training in communication skills to help them develop good relationships with patients, doctors and other members of staff.

The main limitation of this study is the inductive approach inherent in the study design. It is easy to ‘find what you are looking for’ in a study based on a relatively small number of interviews. We attempted to mitigate this limitation by having two investigators independently analyse the data. Another potential limitation is an overly homogenous set of informants, which might limit the themes raised. Unfortunately, we were only able to recruit from 60% of the universities with eligible graduates. In addition, most UK PAs work in south-east England and, thus, this area of the UK is over-represented here. A final limitation is that the participants in this study were all volunteers. It is possible that study volunteers have different views on the PA profession, which might have influenced the results. Further research that is more representative will be helpful to either confirm or refute the findings of this study.

This research study was conducted before the advent of the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic and during a time where the number of PA programmes in the UK was expanding rapidly, bringing even more PAs into the NHS. These factors provide many avenues for future research. Interviewing a larger number of PAs, from more programmes and hospital trusts would enable us to characterise how the ‘second wave’ of new PA graduates is integrating into NHS hospitals. PAs might have had their roles changed or expanded because of the workforce needs of the NHS during various COVID-related surges. As more programmes have developed, the effects of potentially heterogeneous PA education on the development of individual PAs and the PA profession might become more apparent. Finally, the ongoing attempt to achieve regulation for the profession (as of this writing, slated for 2024) and more clarity around scope of practice could present new barriers and facilitators for PAs working in secondary care.15 Conducting more representative quantitative research with larger numbers of PAs and doctors across the UK would also allow us to overcome some of the methodological limitations of this study.

Conclusion

The success of bringing PAs into a secondary care service in the NHS is not automatically assured. We found 10 facilitators to the successful initiation of the role, some of which are under the control of the hospital trust and some of which are under control of the PA. Both PAs and the hospital trust leadership teams need to work and plan to enable the successful implementation of PAs. Further research as the profession expands across the country and across specialties will likely uncover further facilitators.

Acknowledgements

We would like to thank Dr Barbara Jackson for her mentorship and all of our participants for their time and insights. The authors would also like to thank the PA Foundation for their financial support of the transcription services for this project.

References

- 1.Faculty of Physician Associates . Faculty of Physician Associates Annual Census 2021. FPA, 2021. www.fparcp.co.uk/about-fpa/fpa-census [Accessed 08 August 2022]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.Newcastle University . Health Education England Bursaries (Physician Associate Studies, PGDip) Newcastle University, value of award. www.ncl.ac.uk/postgraduate/funding/sources/allstudents/heepas.html. [Accessed 6 May 2017].

- 3.Woodin J, McLeod H, McManus R, Jelphs K. Evaluation of US-trained Physician Assistants working the NHS in England: the introduction of US-trained Physician Assistants to Primary Care and the Accident and Emergency departments in Sandwell and Birmingham Final Report. University of Birmingham, 2008. www.birmingham.ac.uk/Documents/college-social-sciences/social-policy/HSMC/publications/2005/Evaluation-of-US-trained-Physician-Assistants.pdf [Accessed 10 May 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 4.Farmer J, Currie M, West C, Hyman J, Arnott N. Evaluation of Physician Assistants to NHS Scotland. University of the Highlands and Islands, 2009. https://static1.squarespace.com/static/544f552de4b0645de79fbe01/t/54b544e0e4b0c1225eb116ce/1421165792194/Scotland-PA-Final-report-Jan-09.pdf. [Accessed 10 May 2017]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Drennan VM, Halter M, Wheeler C, et al. What is the contribution of physician associates in hospital care in England? A mixed methods, multiple case study. BMJ Open 2019;9:e027012. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.NVivo 11 . QSR International; 2015. www.qsrinternational.com/nvivo-qualitative-data-analysis-software/home

- 7.Govaerts N, Kyndt E, Dochy F, Baert H. Influence of learning and working climate on the retention of talented employees. J Workplace Learning 2011;23:35–55. [Google Scholar]

- 8.Ritsema TS, Roberts KA. Job satisfaction among British physician associates. Clin Med 2016;16:511–3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gagné M, Deci EL. Self-determination theory and work motivation. J Organizational Behavior 2005;26:331–62. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Halter M, Wheeler C, Drennan VM, et al. Physician associates in England's hospitals: a survey of medical directors exploring current usage and factors affecting recruitment. Clin Med 2017;17:126–31. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Drennan VM, Calestani M, Taylor F, Halter M, Levenson R. Perceived impact on efficiency and safety of experienced American physician assistants/associates in acute hospital care in England: findings from a multi-site case organisational study. JRSM Open 2020;11:2054270420969572. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hutchinson L, Marks T, Pittilo M. The physician assistant: would the US model meet the needs of the NHS? BMJ 2001;323:1244–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Williams LE, Ritsema TS. Satisfaction of doctors with the role of physician associates. Clin Med 2014;14:113–6. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Theodoraki M, Hany T, Singh H, Khatri M. Multisource feedback for the physician associate role. R Coll Surgeons Bull 2021;103:206–10. [Google Scholar]

- 15.Faculty of Physician Associates - quality health care across the NHS. https://www.fparcp.co.uk/about-fpa/news/update-on-pa-and-aa-regulation-wider-regulatory-reform-department-of-health-and-social-care-latest-position. [Accessed 19 August 2012].