Bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy appears to be higher in patients who self-report as Black.

Abstract

PURPOSE

The incidence of multiple myeloma (MM) is two to three times higher in Black patients compared with other races, making it the most common hematologic malignancy in this patient population. Current treatment guidelines recommend the combination of a proteasome inhibitor, an immunomodulatory agent, and a corticosteroid as preferred induction therapy. Bortezomib use comes with the risk of peripheral neuropathy (PN) and potential need for dose reduction, therapy interruption, and additional supportive medications. Known risk factors for bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy (BIPN) include diabetes mellitus, previous thalidomide, advanced age, and obesity. We aimed to determine the potential association between Black race and incidence of BIPN.

PATIENTS AND METHODS

We identified a cohort of 748 patients with newly diagnosed MM who received induction with bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone from 2007 to 2016. One hundred forty Black patients were matched with 140 non-Black patients on age, sex, BMI, and route of bortezomib administration. Incidence of BIPN was a binary event defined as new use of a neuropathy medication, bortezomib dose reduction, dose omission, or discontinuation because of PN.

RESULTS

The incidence of BIPN was higher in Black patients (46%) compared with non-Black patients (34%; P = .05) in both univariate (odds ratio [OR], 1.61; 95% CI, 1.00 to 2.61; P = .052) and multivariable analyses (OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.01 to 2.67; P = .047). No significant differences in BIPN were seen when stratified by route of administration.

CONCLUSION

These data indicate that Black race is an independent risk factor for the development of BIPN. Additional prevention strategies, close monitoring, and appropriate supportive care measures are warranted for these patients.

INTRODUCTION

Multiple myeloma (MM) is the second most frequent hematologic malignancy in the United States and Europe. The incidence of MM is two to three times higher in Black people, making it the most common hematologic malignancy in this patient population.1 In the past decade, the prognosis of patients with MM has substantially improved, with novel regimens incorporating proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulatory agents, monoclonal antibodies, and stem-cell transplantation yielding improved overall survival outcomes.2 Current guidelines recommend proteasome inhibitors, immunomodulatory agents, and corticosteroids, with or without monoclonal antibodies, followed by stem-cell transplantation as initial treatment for transplant-eligible patients.2,3 The combination of bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone (RVd) has demonstrated excellent clinical outcomes for patients with MM regardless of intent for transplant4,5 and has become a standard induction regimen for patients with newly diagnosed MM.5

CONTEXT

Key Objective

To determine if bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy (BIPN) develops more commonly in patients who self-identify as Black when known risk factors such as diabetes, BMI, and bortezomib route of administration are controlled for across groups.

Knowledge Generated

BIPN as defined by clinical interventions for management occurs more commonly in Black patients and is independent of bortezomib route of administration. This difference was seen in newly diagnosed patients within four cycles of induction therapy with bortezomib, lenalidomide, and dexamethasone.

Relevance

Clinically actionable BIPN occurs more commonly in Black patients and warrants vigilant monitoring for intervention. As therapies for myeloma improve, the risk-benefit calculus of intensity of bortezomib dosing in all patients may need to be re-evaluated to ensure further reduction of BIPN incidence and severity.

Bortezomib, a selective inhibitor of the 26S proteasome, disrupts the major intracellular protein degradation pathway, leading to cell cycle arrest and apoptosis.6 It is not only an important agent in induction, but also an option for maintenance therapy in cytogenetically defined high-risk patients. Nevertheless, the use of bortezomib comes with frequent and potentially debilitating adverse events. Bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy (BIPN) is a significant therapy-limiting toxicity that often leads to dose reduction, therapy interruption, supportive medication initiation, and/or discontinuation. Incidences of grades 1 and 2 BIPN range from 40% to 70% across studies.6 Low-grade BIPN typically presents as mild to moderate distal sensory loss, pain at fingertips and toes, and mild motor weakness. Subcutaneous (SC) administration of bortezomib was approved by the US Food and Drug Administration in 2012 on the basis of a phase III trial showing a lower rate of peripheral neuropathy (PN) with SC administration (38%) compared with intravenous (IV) administration (53%) without loss of efficacy.7 SC administration has therefore become the preferred route of administration of bortezomib for safety, efficacy, efficiency, and patient preference.8 Although subsequent studies support the findings that SC administration is associated with lower rates of PN, all grade PN was reported in 72% of patients receiving SC bortezomib as part of the RVd induction regimen in the GRIFFIN trial.4

Patients who experience BIPN may require additional medication management. Pharmacologic options include opioids, tricyclic antidepressants, anticonvulsants, and serotonin norepinephrine reuptake inhibitors.6 Use of nonsteroidal anti-inflammatory agents, vitamins, and supplements have also been documented to be beneficial.9 Severe neurotoxicity often requires dose adjustments or even therapy discontinuation.6 Previous studies suggest that bortezomib inhibits the proliferation of MM endothelial cells in a dose-dependent and time-dependent manner.1 Therefore, interruption in RVd induction therapy may lead to unfavorable treatment outcomes. Previous studies have also identified previous therapy with thalidomide, advanced age, baseline neuropathy, pre-existing diabetes mellitus (DM), route and cumulative dose of bortezomib, and BMI >25 as risk factors for BIPN.6,10 In addition to these established risk factors, race has also been proposed as a possible risk factor for BIPN. A retrospective study with 27 subjects suggested the incidence and severity of BIPN is higher in Black patients compared with non-Black patients, but the study was not powered to detect statistically significant differences.11 In a previous study, we observed a statistically significant higher rate of gabapentin and pregabalin use during high-dose melphalan conditioning regimen in Black patients compared with non-Black patients.12 30% of patients with newly diagnosed MM seen at our center are Black. To determine whether Black race is a risk factor for development of BIPN, we evaluated incidence of BIPN in a real-world data set of Black patients and compared with non-Black patients.13

PATIENTS AND METHODS

This single-center, retrospective study, approved by the Institutional Review Board at Emory University and the Winship Cancer Institute, examined patients age 18 years and older with newly diagnosed MM treated with bortezomib as part of RVd induction from January 2007 to August 2016. Demographic information including age, sex, BMI, self-reported race, and MM stage were extracted from electronic medical records. Race was categorized as Black or non-Black. Additional demographic and clinical characteristics, including weight, height, pre-existing diabetes, use of neuropathy medications at baseline, MM subtype, bortezomib route of administration, bortezomib dose, frequency, dose modifications, and PN events and interventions, were also collected. Incidence of BIPN was categorized as a binary variable and defined as an event occurring if at least one PN treatment-emergent event was experienced during treatment with bortezomib, within 30 days after discontinuation of bortezomib or until time of transplant. A PN emergent event was defined as use of a neuropathy medication, bortezomib dose reduction, dose omission, or discontinuation because of PN.

On the basis of availability of SC bortezomib at Emory Healthcare and surrounding hospitals, we assigned IV administration for patients who received bortezomib before January 1, 2013, and SC administration for patients who received bortezomib after January 1, 2013, unless route of administration was specified in the chart.

We identified 747 patients with MM treated with RVd induction therapy between the specified date range after excluding patients who received thalidomide in addition to or before bortezomib. Of these, 225 patients were Black, 435 were non-Black, and 87 patients had no race documentation. To eliminate the confounding effect from a few known risk factors for BIPN, 140 Black patients were matched to 140 non-Black patients with regards to sex, BMI, age, and bortezomib route of administration using a coarsened exact matching algorithm.14

Statistical Analyses

Power calculations were conducted a priori assuming an incidence rate of BIPN of 60% in Black and 45% in non-Black. We calculated that at least 140 cases per race group would be needed to have >80% power to determine an association between BIPN and Black race by one-sided Fisher's exact test under significance level of .05.

We analyzed the incidence of BIPN experienced by patients in Black and non-Black groups. Association between variables of interest and the race cohort were examined using analysis of variance for numerical covariates and chi-square test for categorical covariates. Univariate logistic regression models were used to identify individual prognostic factors. The impact of Black and other patient- and treatment-related factors on the incidence of BIPN was analyzed using multivariate logistic regression. A P value of < .05 was considered statistically significant for all statistical analyses. Statistical analysis was conducted using SAS version 9.4 (SAS Institute, Cary, NC) and SAS macros developed by the Biostatistics and Shared Resource at Winship Cancer Institute.15

RESULTS

Patient Characteristics

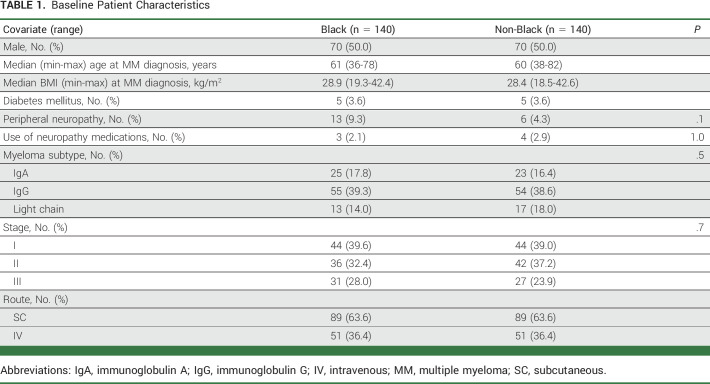

One hundred forty Black patients were included for analysis and matched to 140 non-Black patients on the basis of sex, BMI, age, and route of administration. Patient baseline characteristics before the initiation of bortezomib are shown in Table 1. Median age at diagnosis was 61 years (range, 36-78 years) in the Black group and 60 years (range, 38-82 years) in the non-Black group. Median BMI at diagnosis was 28.9 (range, 19.3-42.4) in the Black group and 28.4 (range, 18.5-42.6) in the non-Black group. This is consistent with population-based study as well as the demographics of the MM population at Emory Healthcare.16,17 MM type and stage were similar between the two groups.

TABLE 1.

Baseline Patient Characteristics

Primary Analysis

Overall, 112 (40%) patients experienced new or worsening PN after initiating bortezomib-containing therapy (Data Supplement [Table 1], online only). The incidence of BIPN was higher in the Black group than in the non-Black group (Black, n = 64, 46%; non-Black, n = 48, 34%; P = .05).

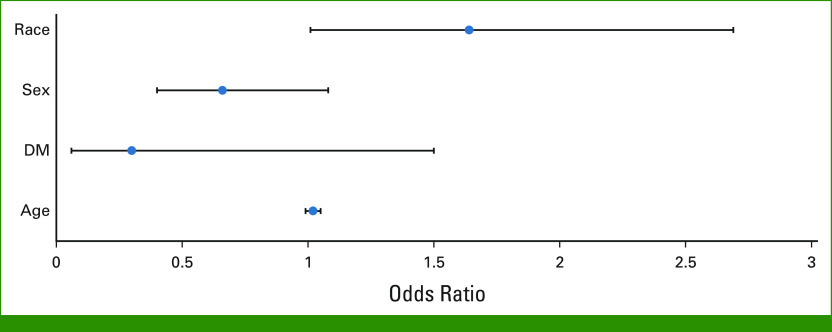

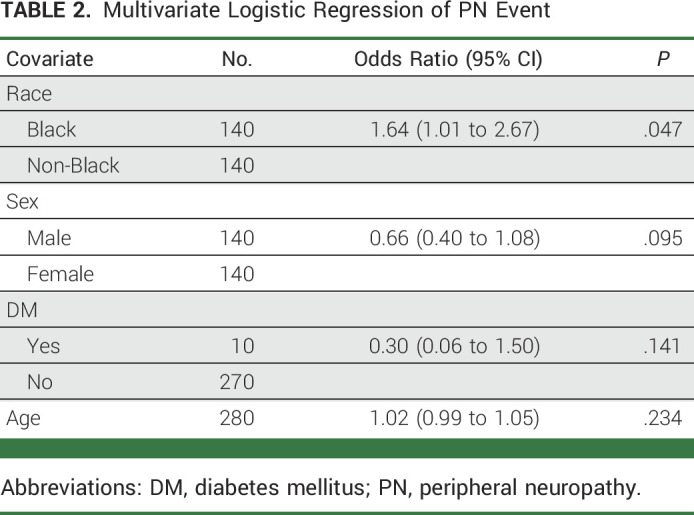

By univariate logistics regression analysis, Black race was associated with an increased risk of BIPN compared with non-Black (odds ratio [OR], 1.61; 95% CI, 1.00 to 2.61; P = .051; Data Supplement [Table 2 and Fig 1]). On the basis of the univariate analysis and previous literature, several risk factors were included in the multivariable logistic regression model, including race, sex, DM, and age. A significant independent association between Black race and the incidence of BIPN was observed (OR, 1.64; 95% CI, 1.01 to 2.67; P = .047; Table 2; Fig 1). Other covariates, including pre-existing DM diagnosis at baseline and advanced age, were not found to independently increase risk of BIPN. Although there was no statistically significant difference between male and female patients, there was a trend toward lower incidence of BIPN in males than in females (OR, 0.66; 95% CI, 0.41 to 1.06; P = .088).

TABLE 2.

Multivariate Logistic Regression of PN Event

FIG 1.

Impact of age, pre-existing DM diagnosis, sex, and race on risk of BIPN using multivariate logistic regression model. ORs and 95% CIs for risk of BIPN with age, pre-existing DM diagnosis, sex, and race using multivariate logistic regression model are shown. ORs for Black patients were compared with non-Black patients; patients with pre-existing DM diagnosis were compared with those without; male were compared with female patients. A significant increased risk of BIPN was observed in Black patients. By contrast, no statistically significant risk for BIPN was observed with other covariates. BIPN, bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy; DM, diabetes mellitus; ORs, odds ratios.

Secondary Analyses

There was no difference in the incidence of bortezomib discontinuation (Black, n = 20, 14.3%; non-Black, n = 15, 10.7%; P = .37) or of addition of PN medications (Black, n = 19, 13.6%; non-Black, n = 17, 12.1%; P = .72; Table 2). Although the overall addition of PN medications was similar among the two groups, Black patients had a slightly higher incidence of documented gabapentin use for BIPN.

Incidence of BIPN was similar for IV and SC routes. For IV, 40.2% (n = 41) of patients versus 39.9% (n = 71) who received SC developed BIPN. There were no significant differences in BIPN incidence in Black patients compared with non-Black patients when stratified by route of administration. In the IV bortezomib subgroup, 47% (n = 24) of Black patients and 33% (n = 17) of non-Black patients developed BIPN. In the SC bortezomib subgroup, 45% (n = 40) of Black patients and 35% (n = 31) of non-Black patients developed BIPN.

DISCUSSION

Our investigation of 280 patients with myeloma receiving bortezomib-based induction showed that, when known risk factors are used for matching, Black patients have a higher incidence of BIPN than non-Blacks (Black, n = 64, 46%; non-Black, n = 48, 34%; P = .05). Although the incidence of BIPN was higher in Blacks than in non-Blacks, there was no difference in rates of bortezomib discontinuation or in addition of PN medications between the two groups. In contrast to previous studies, the route of administration of bortezomib (IV v SC) did not affect the rate of BIPN. Although the rate of BIPN was higher in women than in men, the difference did not reach statistical significance. There is limited preclinical data investigating the impact of sex on BIPN, and sex is not a previously known risk factor for BIPN. The hypothesis that BIPN may affect women more than men warrants further investigation.

To our knowledge, ours is the first study investigating the incidence of BIPN in Black patients with a large sample size. A previous abstract of a retrospective study reported a BIPN rate of 83% in Black patients.11 In another study of patients with Waldenstrom macroglobulinemia, 70% of Black patients developed BIPN.18 Both studies had small sample sizes of <50 patients.

In our study, the rate of PN in both Blacks and non-Blacks was slightly lower than we had hypothesized (12% v 15%, respectively). We observed a lower incidence of BIPN in non-Black patients compared with previous literature possibly because of differences in neuropathy prevention and assessment and/or the differences between our general population compared with those enrolled in prospective clinical trials. In addition, we aimed to carry out racial disparity analysis and our population may have been different than what is commonly seen in other centers and included in the literature (eg, differing rates of pre-existing diabetes). Patient-related factors including denial of pain because of fear of disease recurrence or progression and hesitation about use of pain medications are also identified to contribute to reluctance to report pain, which may affect all BIPN assessments.19

Various genetic factors have also been investigated in relation to BIPN.20,21 Genes associated with immune function (CTLA4 and CTSS), reflexive coupling with Schwann cells (GJE1), drug binding (PSMB1), neuron function (TCF4, DYNC1l1), and steroid hormone biosynthesis (CYP17A1) were identified to be associated with increased risk for BIPN in previous studies.20,21 However, the majority of the patients included in these studies were White, and limited information is available to assess frequency of identified single-nucleotide polymorphisms in Black patients. More recently, race has been hypothesized as a risk factor for BIPN. Cheung and Pang11 reported that incidence and severity of BIPN was higher in non-Caucasian compared with Caucasian patients (80% v 25%). Of the patients who developed BIPN, Black patients had more severe PN that led to dose reduction and discontinuation. Moore et al10 also identified Black race as a risk factor for developing BIPN and concluded that this finding is correlated with higher incidence of BMI in Black patients. In our study, we aimed to control for BMI by using it as one of the parameters to match Black and non-Black patients.

Some studies, but not all, have demonstrated that the IV route of administration causes more neuropathy than the SC route. Moreau et al7 conducted a randomized, international, phase III study that randomly assigned 222 patients with relapsed MM to receive IV or SC bortezomib. BIPN of any grade was significantly less common in the SC group (38% v 53%; P = .044). By contrast, Minarik et al22 reviewed 164 patients with newly diagnosed MM and 98 patients with relapsed MM and reported no statistically significant difference in incidence of BIPN between IV and SC administration. For BIPN of any grade, the rate was 48% in the IV group and 40.5% in the SC group (P = .782). No significant difference in dose reduction was observed in either IV (14.1%) or SC (9.4%) administration (P = .271).

Our study retrospectively evaluated a larger sample size of patients with newly diagnosed MM and adds to the body of knowledge from both the Moreau and the Minarik studies. The Minarik results are similar to what we observed when stratified by route of administration. We recognize the different patient populations in each—our cohort only included patients with newly diagnosed MM, whereas only patients with relapsed disease were enrolled in the Moreau international SQ randomized trial, and Minarik et al22 reviewed patients regardless of treatment lines.7 Across each of these data sets, there may also be differences in neuropathy assessment, prophylaxis used by patients, and bortezomib dosing schedule that may have had an impact on differing BIPN frequency and severity.

Limitations to our study include the retrospective approach. Patients who received bortezomib infusion outside of Emory Healthcare also had limited documentation of dose modifications and PN medications. For patients who received upfront transplant, we only collected data until time of transplant. The majority of transplant-eligible patients received less than four cycles (20.8 mg/m2) of bortezomib and may not have had time to develop BIPN. In an open-label, nonrandomized phase II trial, Richardson et al23 pointed out that the incidence of BIPN rarely increases after the fifth cycle in patients with relapsed myeloma receiving IV bortezomib. However, BIPN is generally recognized as a dose-dependent event and additional studies are needed to investigate the effect of time and cumulative dose in newly diagnosed patients via SC administration, for example, patients ineligible for transplant and those who receive bortezomib as part of maintenance therapy after transplant. Our study did not characterize the grade of PN, but instead took a practical approach to interventions taken in response to patient reports and examination. Finally, while we attempted to account for established and potential risk factors for BIPN, there may be additional confounding factors, including pharmacogenomics, socioeconomic status, and likelihood to report adverse events during office visits, that may need to be further investigated.

In conclusion, this retrospective review illustrated that Black race was an independent risk factor for the development of BIPN in patients with newly diagnosed MM receiving RVd therapy. Black patients had a significantly higher incidence of BIPN compared with non-Black patients when matched for common predictive variables. Considering that bortezomib has significant anticancer properties against multiple cancer types, future studies should address the clinical impact and optimal management for patients of different races at high risk for BIPN. At the same time, clinicians should continue to vigilantly monitor Black patients on bortezomib and prescribe appropriate supportive medications and other interventions as indicated.

Kathryn T. Maples

Employment: Pfizer

Consulting or Advisory Role: GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Janssen, Pfizer

Kevin H. Hall

Employment: Lilly

Nisha S. Joseph

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen Biotech, GlaxoSmithKline

Research Funding: Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation, Janssen Biotech, Novartis, Regeneron

Craig C. Hofmeister

Honoraria: AbbVie, Janssen Oncology

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Oncopeptides

Research Funding: Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Sanofi (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Patent related to REC-2282 (formerly AR-42, NSC D736012)

Jonathan L. Kaufman

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, AbbVie, Incyte

Research Funding: Merck (Inst), Celgene (Inst), Janssen (Inst), Sutro Biopharma (Inst), Fortis (Inst), Amgen (Inst), AbbVie/Genentech (Inst), BMS (Inst)

Madhav Dhodapkar

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche/Genentech, Lava Therapeutics, Janssen Oncology

Ajay K. Nooka

Honoraria: Amgen, Janssen Oncology, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Takeda, Oncopeptides, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Genzyme, BeyondSpring Pharmaceuticals, Secura Bio, Pfizer, ONK Therapeutics, Cellectar

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen, Janssen Oncology, Bristol Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Takeda, Oncopeptides, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Genzyme, BeyondSpring Pharmaceuticals, Secura Bio, Pfizer, ONK Therapeutics, Cellectar

Research Funding: Amgen (Inst), Janssen Oncology (Inst), Takeda (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene (Inst), Arch Oncology (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Cellectar (Inst), Pfizer (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: GlaxoSmithKline

Sagar Lonial

This author is an Associate Editor for JCO Oncology Practice. Journal policy recused the author from having any role in the peer review of this manuscript.

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: TG Therapeutics

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen Oncology, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Amgen, AbbVie, Takeda, Merck, Sanofi, Pfizer

Research Funding: Celgene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Takeda, Janssen Oncology, Novartis

Other Relationship: TG Therapeutics

R. Donald Harvey

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen, Erasca, Inc, Janssen Oncology

Research Funding: AbbVie (Inst), Nektar (Inst), Xencor (Inst), Meryx Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Abbisko (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Merck (Inst), Takeda (Inst), Janssen Research & Development (Inst), ADC Therapeutics, Incyte, MorphoSys

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

SUPPORT

Supported in part by the Biostatistics and Bioinformatics Shared Resource of Winship Cancer Institute of Emory University and NIH/NCI under award number P30CA138292.

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Disclosures provided by the authors are available with this article at DOI https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.22.00781.

DATA SHARING STATEMENT

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, R.D.H. The data are not publicly available because of restrictions such as their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

Conception and design: Laura F. Sun, Kathryn T. Maples, Kevin H. Hall, Yuan Liu, Jonathan L. Kaufman, Ajay K. Nooka, Sagar Lonial, R. Donald Harvey

Provision of study materials or patients: Nisha S. Joseph, Craig C. Hofmeister, Jonathan L. Kaufman, Madhav Dhodapkar, Ajay K. Nooka, Sagar Lonial

Collection and assembly of data: Laura F. Sun, Kathryn T. Maples, Nisha S. Joseph, R. Donald Harvey

Data analysis and interpretation: Laura F. Sun, Kathryn T. Maples, Kevin H. Hall, Yuan Liu, Yichun Cao, Craig C. Hofmeister, Jonathan L. Kaufman, Madhav Dhodapkar, Sagar Lonial, R. Donald Harvey

Manuscript writing: All authors

Final approval of manuscript: All authors

Accountable for all aspects of the work: All authors

AUTHORS' DISCLOSURES OF POTENTIAL CONFLICTS OF INTEREST

Impact of Black Race on Peripheral Neuropathy in Patients With Newly Diagnosed Multiple Myeloma Receiving Bortezomib Induction

The following represents disclosure information provided by authors of this manuscript. All relationships are considered compensated unless otherwise noted. Relationships are self-held unless noted. I = Immediate Family Member, Inst = My Institution. Relationships may not relate to the subject matter of this manuscript. For more information about ASCO's conflict of interest policy, please refer to www.asco.org/rwc or ascopubs.org/op/authors/author-center.

Open Payments is a public database containing information reported by companies about payments made to US-licensed physicians (Open Payments).

Kathryn T. Maples

Employment: Pfizer

Consulting or Advisory Role: GlaxoSmithKline, Sanofi, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Janssen, Pfizer

Kevin H. Hall

Employment: Lilly

Nisha S. Joseph

Consulting or Advisory Role: Janssen Biotech, GlaxoSmithKline

Research Funding: Bristol Myers Squibb Foundation, Janssen Biotech, Novartis, Regeneron

Craig C. Hofmeister

Honoraria: AbbVie, Janssen Oncology

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Oncopeptides

Research Funding: Bristol Myers Squibb (Inst), Sanofi (Inst)

Patents, Royalties, Other Intellectual Property: Patent related to REC-2282 (formerly AR-42, NSC D736012)

Jonathan L. Kaufman

Consulting or Advisory Role: Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, AbbVie, Incyte

Research Funding: Merck (Inst), Celgene (Inst), Janssen (Inst), Sutro Biopharma (Inst), Fortis (Inst), Amgen (Inst), AbbVie/Genentech (Inst), BMS (Inst)

Madhav Dhodapkar

Consulting or Advisory Role: Roche/Genentech, Lava Therapeutics, Janssen Oncology

Ajay K. Nooka

Honoraria: Amgen, Janssen Oncology, Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene, GlaxoSmithKline, Takeda, Oncopeptides, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Genzyme, BeyondSpring Pharmaceuticals, Secura Bio, Pfizer, ONK Therapeutics, Cellectar

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen, Janssen Oncology, Bristol Myers Squibb, GlaxoSmithKline, Takeda, Oncopeptides, Karyopharm Therapeutics, Adaptive Biotechnologies, Genzyme, BeyondSpring Pharmaceuticals, Secura Bio, Pfizer, ONK Therapeutics, Cellectar

Research Funding: Amgen (Inst), Janssen Oncology (Inst), Takeda (Inst), Bristol Myers Squibb/Celgene (Inst), Arch Oncology (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Cellectar (Inst), Pfizer (Inst)

Travel, Accommodations, Expenses: GlaxoSmithKline

Sagar Lonial

This author is an Associate Editor for JCO Oncology Practice. Journal policy recused the author from having any role in the peer review of this manuscript.

Stock and Other Ownership Interests: TG Therapeutics

Consulting or Advisory Role: Celgene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Janssen Oncology, Novartis, GlaxoSmithKline, Amgen, AbbVie, Takeda, Merck, Sanofi, Pfizer

Research Funding: Celgene, Bristol Myers Squibb, Takeda, Janssen Oncology, Novartis

Other Relationship: TG Therapeutics

R. Donald Harvey

Consulting or Advisory Role: Amgen, Erasca, Inc, Janssen Oncology

Research Funding: AbbVie (Inst), Nektar (Inst), Xencor (Inst), Meryx Pharmaceuticals (Inst), Abbisko (Inst), GlaxoSmithKline (Inst), Merck (Inst), Takeda (Inst), Janssen Research & Development (Inst), ADC Therapeutics, Incyte, MorphoSys

No other potential conflicts of interest were reported.

REFERENCES

- 1.Röllig C, Knop S, Bornhäuser M: Multiple myeloma. Lancet 385:2197-2208, 2015 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.National Comprehensive Cancer Network : Multiple myeloma (version 5.2022). https://www.nccn.org/professionals/physician_gls/pdf/myeloma.pdf

- 3.Fricker LD: Proteasome inhibitor drugs. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol 60:457-476, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Voorhees PM, Kaufman JL, Laubach J, et al. : Daratumumab, lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone for transplant-eligible newly diagnosed multiple myeloma: The GRIFFIN trial. Blood 136:936-945, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Durie BGM, Hoering A, Abidi MH, et al. : Bortezomib with lenalidomide and dexamethasone versus lenalidomide and dexamethasone alone in patients with newly diagnosed myeloma without intent for immediate autologous stem-cell transplant (SWOG S0777): A randomised, open-label, phase 3 trial. Lancet 389:519-527, 2017 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Argyriou AA, Iconomou G, Kalofonos HP: Bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy in multiple myeloma: A comprehensive review of the literature. Blood 112:1593-1599, 2008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Moreau P, Pylypenko H, Grosicki S, et al. : Subcutaneous versus intravenous administration of bortezomib in patients with relapsed multiple myeloma: A randomised, phase 3, non-inferiority study. Lancet Oncol 12:431-440, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Barbee MS, Harvey RD, Lonial S, et al. : Subcutaneous versus intravenous bortezomib: Efficiency practice variables and patient preferences. Ann Pharmacother 47:1136-1142, 2013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Cleary JF: The pharmacologic management of cancer pain. J Palliat Med 10:1369-1394, 2007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Moore DC, Ringley JT, Nix D, et al. : Impact of body mass index on the incidence of bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy in patients with newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma Leuk 20:168-173, 2020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cheung E, Pang K: Impact of race on bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy. Blood 130, 2017. (suppl 1; abstr 5436) [Google Scholar]

- 12.Sivakumar A, Bryson EB, Hall KH, et al. : Impact of concurrent gabapentin or pregabalin with high‐dose melphalan in patients with multiple myeloma undergoing autologous hematopoietic stem cell transplant. Pharmacotherapy 42:233-240, 2022 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Sun L, Maples KT, Hall KH, et al. : African American race as a risk factor for developing peripheral neuropathy in newly diagnosed patients with multiple myeloma receiving bortezomib induction. Blood 140:7131-7132, 2022. (suppl 1) [Google Scholar]

- 14.Iacus SM, King G, Porro G: Causal inference without balance checking: Coarsened exact matching. Polit Anal 20:1-24, 2012 [Google Scholar]

- 15.Liu Y, Nickleach DC, Zhang C, et al. : Carrying out streamlined routine data analyses with reports for observational studies: Introduction to a series of generic SAS macros. F1000Res 7:1955, 2019 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Joseph NS, Kaufman JL, Dhodapkar MV, et al. : Long-term follow-up results of lenalidomide, bortezomib, and dexamethasone induction therapy and risk-adapted maintenance approach in newly diagnosed multiple myeloma. J Clin Oncol 38:1928-1937, 2020 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Waxman AJ, Mink PJ, Devesa SS, et al. : Racial disparities in incidence and outcome in multiple myeloma: A population-based study. Blood 116:5501-5506, 2010 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Chen C, Kouroukis CT, White D, et al. : Bortezomib in relapsed or refractory Waldenström’s macroglobulinemia. Clin Lymphoma Myeloma 9:74-76, 2009 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sun V, Borneman T, Piper B, et al. : Barriers to pain assessment and management in cancer survivorship. J Cancer Surviv Res Pract 2:65-71, 2008 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Favis R, Sun Y, van de Velde H, et al. : Genetic variation associated with bortezomib-induced peripheral neuropathy. Pharmacogenet Genomics 21:121-129, 2011 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Corthals SL, Kuiper R, Johnson DC, et al. : Genetic factors underlying the risk of bortezomib induced peripheral neuropathy in multiple myeloma patients. Haematologica 96:1728-1732, 2011 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Minarik J, Pavlicek P, Pour L, et al. : Subcutaneous bortezomib in multiple myeloma patients induces similar therapeutic response rates as intravenous application but it does not reduce the incidence of peripheral neuropathy. PLoS One 10:e0123866, 2015 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Richardson PG, Barlogie B, Berenson J, et al. : A phase 2 study of bortezomib in relapsed, refractory myeloma. N Engl J Med 348:2609-2617, 2003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

The data that support the findings of this study are available on request from the corresponding author, R.D.H. The data are not publicly available because of restrictions such as their containing information that could compromise the privacy of research participants.