Keywords: heat stress, occupational exposure limit, ULPZ, WBGT

Abstract

Heat stress has an adverse impact on worker health and well-being, and the effects will increase with more frequent and severe heat events associated with global warming. Acclimatization to heat stress is widely considered to be a critical mitigation strategy and wet bulb globe temperature- (WBGT-) based occupational standards and guidelines contain adjustments for acclimatization. The purpose here was to 1) compare the mean values for the upper limit of the prescriptive zone (ULPZ, below which the rise in core temperature is minimal) between unacclimatized and acclimatized men and women; 2) demonstrate that the change in the occupational exposure limit (ΔOEL) due to acclimatization is independent of metabolic rate; 3) examine the relation between ΔOEL and body surface area (BSA); and 4) compare the exposure-response curves between unacclimatized and acclimatized populations. Empirically derived ULPZ data for unacclimatized participants from Pennsylvania State University (PSU) and acclimatized participants from University of South Florida (USF) were used to explore the difference between unacclimatized and acclimatized heat exposure limits. The findings provide support for a constant 3°C WBGT OEL decrease to account for unacclimatized workers. Body surface area explained part of the difference in ULPZ values between men and women. In addition, the pooled PSU and USF data provide insight into the distribution of individual values for the ULPZ among young, healthy unacclimatized and acclimatized populations in support of occupational heat stress guidelines.

NEW & NOTEWORTHY Occupational exposure limit guidelines using wet bulb globe temperature (WBGT) distinguish between acclimatized and unacclimatized workers with about a 3°C difference between them. For the first time, empirical data from two laboratories provide support for acclimatization state adjustments. Using a constant difference rather than increasing differences with metabolic rate better describes the limit for unacclimatized participants. Furthermore, the lower upper limit of the prescriptive zone (ULPZ) values set forth for women do not relate to fitness level but are partly explained by their smaller body surface area (BSA). An examination of individual ULPZ values suggests that many unacclimatized individuals should be able to sustain safe work at the exposure limit for acclimatized workers.

INTRODUCTION

Occupational heat exposure is widely recognized as contributing to heat-related disorders, and heat-related risks to industrial workers will increase with extreme temperature events caused by global warming. From 2011 through 2020, there were 400 fatalities due to environmental heat exposure (1, 2). Between 1906 and 2005, the global average surface temperature rose by 0.6–0.9°C. The rate of temperature increase has nearly doubled in the last 50 years, and over the next 20 years the rate of rise will accelerate (3, 4). As unstable weather patterns grow in number and severity, more workers will be exposed to extreme heat in the workplace. Heat acclimatization, or more specifically the detrimental effects of the lack of acclimatization, will be an increasingly important consideration in the management of occupational heat stress.

Heat acclimatization—defined as beneficial physiological adaptations to heat stress induced by repeated work-heat exposures over a prolonged period—increases heat tolerance, enhances worker safety, and minimizes the risk and incidence of heat-related illness (5–7). The importance of acclimatization for occupational exposures is commonly expressed by adjusting wet-bulb globe temperature (WBGT) exposure limits used by the National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (8), the ACGIH (previously known as the American Conference of Governmental Industrial Hygienists) (9), and the International Organization for Standardization (10). Generally, the WBGT limit for unacclimatized workers (referred to in this paper as the occupational alert limit, OAL) is ∼3°C lower than the exposure limit for acclimatized workers (i.e., occupational exposure limit, OEL) at a moderate work rate of 300 W. Overall, the OEL-OAL difference gradually increases with metabolic rate from 2°C at 115 W to 3.5°C at 500 W.

A progressive heat stress protocol was designed to determine the upper limit of the prescriptive zone (ULPZ) (11, 12) at a given metabolic rate. As the metabolic rate increases, the WBGT representing the ULPZ decreases (11, 13). To account for the combined effects of environment and metabolic rate, we have suggested expressing exposures as the elevation above the OEL (ΔOEL, see methods for more details) (14, 15). By asking whether ΔOEL changes as a function of metabolic rate, it is possible to demonstrate whether ΔOEL is a satisfactory method to represent the combined effects.

Among a group of young unacclimatized participants, there were significant differences in ΔOEL between men and women that could not be explained by aerobic fitness (15). Because the ULPZ occurs near the upper limit of thermal equilibrium, the ΔOEL may be affected by the body surface area (BSA); such that a higher BSA would allow for greater dissipation of metabolic heat and thus a higher ΔOEL. If this is true, it may partly explain why the ΔOEL would be higher for men than women.

Garzón et al. (14) showed that the WBGT range of critical environments adjusted for metabolic rate among young, healthy, hydrated, acclimatized individuals can be as large as 10°C WBGT. For a large representative sample of young, healthy, hydrated, unacclimatized, and minimally clothed men and women, Wolf et al. (15) reported a range of 6°C WBGT. If the range of individual values (6°C) is greater than the benefit of acclimatization (3°C), there may be implications for acclimatization-based WBGT adjustments in occupational heat stress management.

The purposes of the present paper were to 1) compare the mean values for the upper limit of the prescriptive zone (ULPZ, below which the rise in core temperature is minimal) between unacclimatized and acclimatized men and women; 2) demonstrate that the change in the occupational exposure limit (ΔOEL) due to acclimatization is independent of metabolic rate; 3) examine the relation between ΔOEL and body surface area; and 4) compare the exposure-response curves between unacclimatized and acclimatized populations. The results may provide context for understanding the benefits of acclimatization on promulgated occupational heat stress exposure limits. This may have implications for future research on how occupational policies and practices for acclimatization are articulated and promoted.

METHODS

To determine the implications of dichotomous acclimatization status in the context of WBGT-based heat stress management, this paper re-examined published data from the Pennsylvania State University (PSU) (16, 17) and the University of South Florida (USF) (13, 18) for unacclimatized and acclimatized men and women, respectively. Both groups used a progressive heat stress protocol to determine the ULPZ for a given trial (called critical conditions in previous papers). The typical trial began with climatic conditions that easily allowed thermal equilibrium for the metabolic rate and clothing ensemble. A physiological steady-state was typically established in the first 30 to 45 min. Once the steady-state was established, dry bulb temperature or vapor pressure for PSU or dry bulb at constant relative humidity (RH) for USF was increased in small steps every 5 min, which allowed a quasi-steady-state to exist before the next increment. After the critical condition, core temperature (Tc) increased steadily and continuously. The critical condition was noted using the judgment of experienced investigators as the last climatic condition for which Tc was steady; and after which Tc increased ∼0.1°C per 5-min step. The informed judgment method provides the same results as segmented regressions (19). At the critical condition, dry bulb, natural wet bulb, and globe temperatures were used to compute the WBGT, and this represented the environment at the ULPZ for a given metabolic rate and clothing ensemble. Tc and heart rate (HR) were also noted.

In the PSU studies reported here, participants were tested in a semiclothed ensemble (tee shirt/sports bra, shorts, socks, and shoes) in ambient conditions representing a wide range of temperature (33–53°C) and relative humidity (10–85%) (19–21). The participants were healthy, hydrated, and unacclimatized. The metabolic rates were light (Bike Study at 83 W·m−2) and moderate (Walking Study at 133 W·m−2).

The USF data were reported previously to examine clothing effects on WBGT at critical condition (13, 18). The young and healthy participants completed a 5-day acclimatization protocol to dry heat (50°C and 20% relative humidity) by walking on a treadmill at a metabolic rate of ∼160 W·m−2 for 2 h. The experimental trials included four clothing ensembles (woven clothing as either shirt and trousers or coverall, nonwoven particle barrier, water barrier using microporous film, and vapor barrier). Only the data on woven clothing is reported here. In one study, metabolic rates were considered at three levels (Low, Moderate, and High) with average rates of 115, 180, and 254 W·m−2 in which each participant wore the two woven clothing ensembles at all three metabolic rates (Met Study) with relative humidity held at 50%. A second study (RH Study) used the two woven clothing ensembles at three humidity levels (20, 50, and 70% RH) and a moderate metabolic rate (155 W·m−2).

Participant characteristics by study are described in Table 1. Table 2 describes the distribution of trials with the mean and standard deviation of the metabolic rate (MR), Tc, and HR. The standard deviations for the Met trials were higher due to the wider range of metabolic rates in the experimental design.

Table 1.

Distribution of participant characteristics (age, weight, height, and body surface area) by study

| Age, yr |

Weight, kg |

Height, m |

Body Surface Area, m2 |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study* | Sex | n | Means ± SD | Means ± SD | Means ± SD | Means ± SD |

| PSU** Bike | Men | 24 | 23.7 ± 4.2 | 84.7 ± 15.4 | 1.81 ± 0.08 | 2.05 ± 0.18 |

| Women | 23 | 23.0 ± 3.8 | 68.2 ± 15.2 | 1.65 ± 0.05 | 1.75 ± 0.17 | |

| PSU** Walk | Men | 23 | 23.3 ± 3.8 | 83.0 ± 13.2 | 1.81 ± 0.07 | 2.03 ± 0.16 |

| Women | 26 | 22.6 ± 3.7 | 68.1 ± 15.0 | 1.66 ± 0.05 | 1.75 ± 0.18 | |

| USF*** Met | Men | 12 | 27.3 ± 9.4 | 84.5 ± 14.4 | 1.76 ± 0.11 | 2.01 ± 0.20 |

| Women | 4 | 23.0 ± 4.7 | 64.2 ± 18.0 | 1.65 ± 0.06 | 1.70 ± 0.22 | |

| USF*** RH | Men | 9 | 29.2 ± 6.8 | 97.4 ± 18.4 | 1.83 ± 0.05 | 2.19 ± 0.20 |

| Women | 4 | 34.0 ± 8.9 | 63.5 ± 20.0 | 1.63 ± 0.06 | 1.68 ± 0.26 |

Study: Pennsylvania State University (PSU) Bike (light metabolic rate); PSU Walk (moderate metabolic rate); University of South Florida (USF) Met Trials (low, moderate, and high metabolic rates at 50% relative humidity); USF RH Trials (20, 50, 70% relative humidity at moderate metabolic rate); **the PSU studies used more participants and each participant completed about two trials in each study; ***the USF studies used fewer participants and each participant completed about six trials.

Table 2.

Distribution of progressive heat stress trials by the four types of trials and clothing for metabolic rate, core temperature, heart rate, and physiological strain index at the upper limit of the prescriptive zone; and the distributions by sex for the four types of trials

| Number of Trials† | MR, W |

Tc, °C |

HR, beats/min |

|||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Study* | Clothing** | Means ± SD | Means ± SD | Means ± SD | ||

| PSU | Bike | SC | 91 | 161 ± 37 | 37.38 ± 0.27 | 94 ± 14 |

| Walk | SC | 99 | 280 ± 57 | 37.66 ± 0.35 | 113 ± 21 | |

| USF | Met Trials | WC | 90 | 347 ± 118 | 37.67 ± 0.30 | 117 ± 20 |

| RH Trials | WC | 86 | 305 ± 82 | 37.77 ± 0.36 | 117 ± 16 | |

| Sex | ||||||

| PSU | Bike | Men | 49 | 183 ± 31 | 37.26 ± 0.22 | 91 ± 11 |

| Women | 42 | 135 ± 24 | 37.51 ± 0.25 | 97 ± 16 | ||

| Walk | Men | 52 | 314 ± 47 | 37.54 ± 0.34 | 105 ± 16 | |

| Women | 47 | 243 ± 42 | 37.79 ± 0.31 | 121 ± 21 | ||

| USF | Met Trials | Men | 66 | 369 ± 115 | 37.68 ± 0.32 | 114 ± 17 |

| Women | 24 | 287 ± 107 | 37.65 ± 0.25 | 126 ± 24 | ||

| RH Trials | Men | 55 | 343 ± 65 | 37.70 ± 0.33 | 112 ± 16 | |

| Women | 31 | 236 ± 63 | 37.90 ± 0.38 | 127 ± 13 |

Values are means ± SD. HR, heart rate; MR, metabolic rate; Tc, core temperature; ULPZ, upper limit of the prescriptive zone.

Study: Bike (light metabolic rate); Walk (moderate metabolic rate); Met Trials (low, moderate, and high metabolic rates at 50% relative humidity); RH trials (20, 50, 70% relative humidity at moderate metabolic rate); **clothing: SC (semiclothed); WC (cotton shirt/trousers or cotton coverall; †note that there was considerable overlap in participants between the two Pennsylvania State University (PSU) studies with each participant completing about two trials in each study. The University of South Florida (USF) studies used fewer participants, each participant completed about 6 trials (2 types of woven clothing at either three metabolic rates or three relative humidity levels) and no overlap between studies.

Because heat stress is a combination of environment, metabolic rate, and clothing, Eq. 1 was used to provide a single metric referenced to the WBGT-based occupational exposure limit (OEL) (15, 22)

| (1) |

where WBGTobs is the observed WBGT in °C, CAV is the clothing adjustment value in °C, and MR is the observed metabolic rate in watts (W). For the USF data, clothing comprised woven work clothes with CAV = 0. For the PSU data, participants wore minimal clothing with CAV taken as −1.0°C based on the 2023 ACGIH TLV for heat stress and strain (9).

Statistical Analysis

JMP v16 (SAS, Cary NC) was used for statistical analysis. A mixed-effects ANOVA with fixed effects for acclimatization state (2 levels) and sex (2 levels) plus the interaction of acclimatization and sex and a random effect for participants was used to examine the ΔOEL for systematic differences in acclimatization state. Significance was accepted at α = 0.05.

The next step examined the independence of ΔOEL from metabolic rate and explored whether there was a difference between acclimatized and unacclimatized. To make the evaluation, a linear regression (Eq. 2) with participants as a random effect was computed. A slope near zero for metabolic rate (MR) (β1) would indicate that ΔOEL was independent of MR. The addition of the acclimatization state (Accl) as a fixed effect and as an interaction with MR would consider if the intercept or slope was affected by acclimatization

| (2) |

To demonstrate the independence of ΔOEL from body surface area (BSA), a similar approach was taken in Eq. 3 with participants as a random effect. A slope (β1 and β2) near zero would support no effect for BSA. Recognizing that BSA and sex are systematically related and to see if BSA accounted for sex effects, a mixed effects model with the main effects of BSA, acclimatization state and sex with participants as a random effect was used to see if sex was an effect

| (3) |

To fit an exposure-response curve, the ΔOEL data were rank ordered from the lowest to highest (15, 22). The probability (p) for each observation was the rank (i, starting at 1) divided by the number of observations (n) plus 1; that is . The odds for each observation was . A ln(odds) linear regression model (Eq. 4) was used to explore the main effects of acclimatization and sex, and their interaction with ΔOEL using a forward stepwise regression using the minimum Akaike information criterion (AICc) to select the model.

| (4) |

To provide additional context to the ULPZ profiles for unacclimatized participants, data from Lind’s study of 3-h exposures were also examined (23). The trials were performed with seminude participants with an approximate metabolic rate of 350 W. For his exposures just below (Tdb/Twb; estimated WBGT) (35.0/25.3; 27.4°C) and above (37.8/26.7; 29.2°C) his proposed limit and well above (40.0/29.4; 31.8°C). The OEL at 350 W for standard clothing was 27.4°C. The effective WBGT was the observed value minus 1.5°C for seminude based on our analysis of a study looking at critical environments for seminude and clothed participants (12). The ΔOELs and proportion of participants not completing the 3-h exposure were: ΔOEL = 0.0°C and 0.04 (1 of 25 did not complete the trial); 1.8°C and 0.32 (6 of 19); and 4.4°C and 0.64 (16 of 25).

RESULTS

From the ANOVA, the least square means are provided in Table 3. Both acclimatization state and sex were significant contributors to ΔOEL (P < 0.001; P = 0.59 for interaction). The mean increase in the ULPZ attributable to acclimatization was 3.4°C, going from a mean for unacclimatized of 2.5°C to 5.9°C. Men had a higher ULPZ (4.9°C) than women (3.5°C) by 1.4°C.

Table 3.

Least square means, with standard error in parentheses, of ΔOEL from ANOVA based on sex and acclimatization state*

| Acclimatization State | Both Sexes | Men | Women | ΔSex |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Both acclimatization state | 4.3 | 4.9 (0.18) | 3.5 (0.23) | 1.4 |

| Acclimatized | 5.9 (0.23) | 6.7 (0.25) | 5.1 (0.38) | 1.6 |

| Unacclimatized | 2.5 (0.17) | 3.2 (0.25) | 1.9 (0.25) | 1.3 |

| ΔAcclimatization | 3.4 | 3.5 | 3.2 |

OEL, occupational exposure limit.

There were significant differences between men and women (P < 0.0001) and between acclimatized and unacclimatized (P < 0.0001). While each combination of sex and acclimatization was significantly different from the others using Tukey’s multiple comparison test at α = 0.05, the interaction of sex and acclimatization state was not significant (P = 0.59).

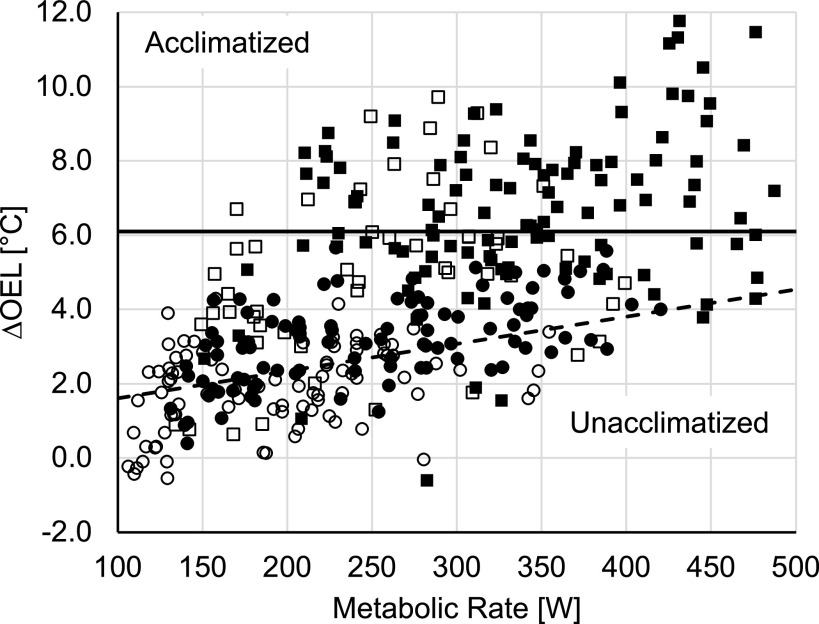

To demonstrate whether the ΔOEL was independent of metabolic rate, the linear regression found both metabolic rate and acclimatization state as well as the interaction to be significant at P < 0.01. Equations 5 (unacclimatized) and 6 (acclimatized) with ±root mean square error (RMSE) are shown. For unacclimatized, the slope and intercept are significant (P < 0.001). The slope for acclimatized was not significant (P = 0.42) and thus the means ± RMSE is reported as Eq. 6. Figure 1 illustrates the relationships. The slope was 0.7°C/100 W, which was associated with a decrease in the difference between unacclimatized and acclimatized from 4.5°C at 100 W to 3°C at 300 W to 1.6°C at 500 W.

| (5) |

| (6) |

Figure 1.

Relationships between Δ occupational exposure limit (OEL) and metabolic rate for acclimatized (squares) and unacclimatized (circles) participants. Men are solid markers and Women are open markers. (See Eqs. 5 and 6.) The effects for acclimatization state, metabolic rate, and the interaction were significant (P < 0.01). The number of participants/observations were for unacclimatized men (24/101), unacclimatized women (26/89), acclimatized men (21/121), and acclimatized women (9/55).

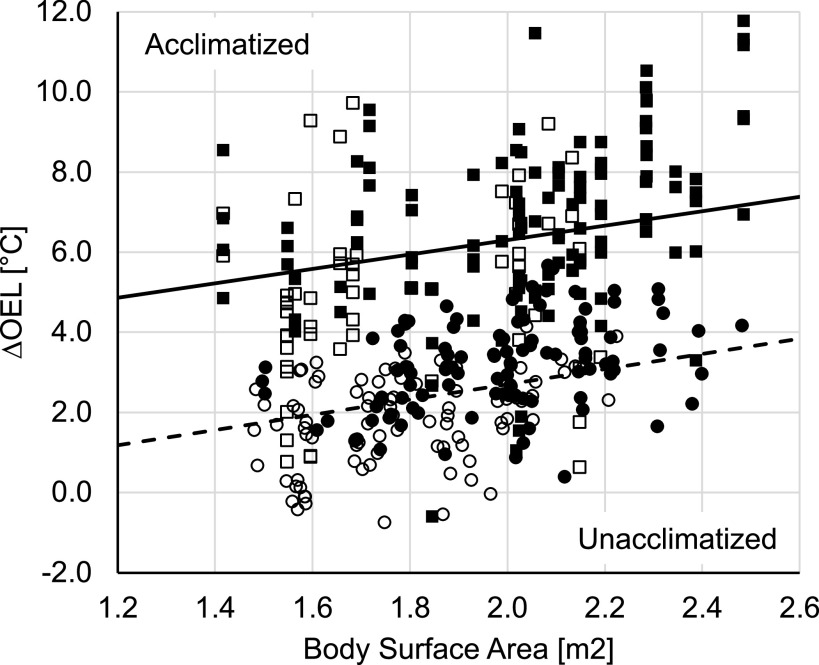

To examine the effect of body surface area (BSA) using Eq. 3, the main effects of BSA and Accl were significant (P < 0.0001) and the interaction was not significant at P = 0.96. The final models were based on BSA. Equations 7 and 8, Table 4, and Fig. 2 illustrate the results. Both the unacclimatized and acclimatized had significant slopes of ∼0.18°C/0.1 m2; such that the ΔOEL increased with BSA. The difference between unacclimatized and acclimatized was virtually constant at 3.6°C (3.7 at 1.4 m2 to 3.5°C at 2.5 m2). The mixed effects model showed that sex was also a significant effect (P < 0.0001) with BSA (P < 0.0001).

| (7) |

| (8) |

Table 4.

Summary of parameter estimates for the linear regressions for unacclimatized and acclimatized participants (see Eqs. 5–10)

| Model | Acclimatization State | Term | Estimate | Standard Error | P Value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ΔOEL vs. MR | Unacclimatized | Intercept | 0.88 | 0.24 | 0.0003 |

| Equation 5 | MR | 0.0072 | 0.00093 | <0.0001 | |

| ΔOEL vs. MR | Acclimatized | Intercept | 5.8† | 0.58 | <0.0001 |

| Equation 6† | MR | 0.0012 | 0.0015 | 0.42 | |

| ΔOEL vs. BSA | Unacclimatized | Intercept | −1.1 | 0.71 | 0.12 |

| Equation 7 | BSA | 1.9 | 0.37 | <0.0001 | |

| ΔOEL vs. BSA | Acclimatized | Intercept | 2.7 | 1.07 | 0.013 |

| Equation 8 | BSA | 1.8 | 0.53 | 0.0008 | |

| ln(odds) | Unacclimatized | Intercept | −3.41 | 0.029 | <0.0001 |

| Equation 9 | ΔOEL | 1.33 | 0.010 | <0.0001 | |

| ln(odds) | Acclimatized | Intercept | −4.70 | 0.032 | <0.0001 |

| Equation 10 | ΔOEL | 0.767 | 0.0049 | <0.0001 |

BSA, body surface area (m2); MR, metabolic rate (W); ΔOEL, the elevation above the occupational exposure limit (OEL) (°C WBGT); WBGT, wet bulb globe temperature.

Because the slope was treated as zero, the mean of 6.1 was used in Eq. 6 instead of the intercept.

Figure 2.

Relationships between Δ occupational exposure limit (OEL) and body surface area (BSA) for acclimatized (squares) and unacclimatized (circles) participants. Men are solid markers and Women are open markers. (See Eqs. 7 and 8 for BSA and acclimatization.) The number of participants/observations were for unacclimatized men (24/101), unacclimatized women (26/89), acclimatized men (21/121), and acclimatized women (9/55). The effects for acclimatization state and sex were significant (P < 0.0001), but only BSA was reported due to the relationship between BSA and sex.

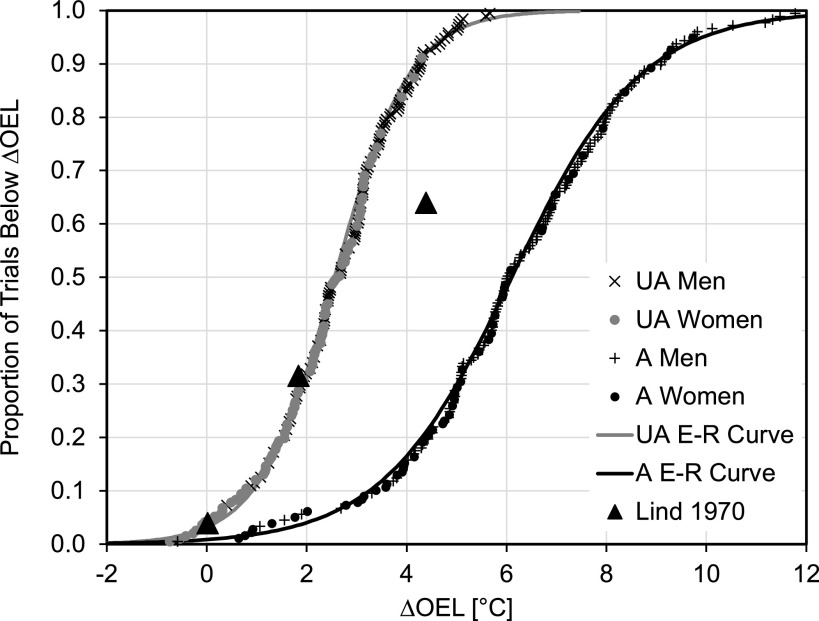

From the stepwise regression of the full ln(odds) model (Eq. 4), ΔOEL, acclimatization state, and the interaction of ΔOEL and acclimatization state were retained; sex and the interaction of sex with ΔOEL increased the AICc and thus were not retained. Because the acclimatization state was both a main effect and an interaction, separate models based on ΔOEL for each acclimatization state were run with participants as a random effect. The results are provided in Table 4 and shown in Eqs. 4 and 5. Figure 3 illustrates the data and the curves based on these equations after converting ln(odds) to a cumulative probability (). As expected the unacclimatized curve was displaced to the left of the acclimatized curve. The slope of the unacclimatized curve was steeper. The difference between the two curves was 2.5°C at P = 0.1, 3.5°C at P = 0.5, and 4.5 at P = 0.9.

| (9) |

| (10) |

Figure 3.

Upper limit of the prescriptive zone (ULPZ) profiles for unacclimatized (Pennsylvania State University, PSU) (left curve) and acclimatized (University of South Florida, USF) (right curve) participants. The markers represent individual data and the lines represent the ln(odds) regression curve where odds were translated to the cumulative proportion of individual ULPZ values below the ULPZ. The number of participants/observations were for unacclimatized men (UA Men: 24/101), unacclimatized women (UA Women: 26/89), acclimatized men (A Men: 21/121), and acclimatized women (A Women: 9/55). The exposure-response (E-R) curve for all unacclimatized (Eq. 9) and all acclimatized participants (Eq. 10) are included. Lind’s data for unacclimatized men (23) are the solid triangles.

DISCUSSION

Occupational heat stress assessment is based on metabolic rate and WBGT, with different safety thresholds for acclimatized and unacclimatized workers. The average adjustment for an unacclimatized worker is currently set at 3°C WBGT; however, empirical data supporting that value have been lacking. To that end, data were collected to specifically determine the upper limit of the prescriptive zone (ULPZ) at Pennsylvania State University (PSU) and University of South Florida (USF) and were used to examine the difference between unacclimatized and acclimatized participants at the ULPZ. The change in the OEL between acclimatized and unacclimatized young men and women was 3.4°C (see Table 3). The mean difference in UPLZs in the present study appeared to be consistent with current professional practice at higher metabolic rates but was greater than the difference at metabolic rates below 275 W (8–10).

The current practice for WBGT-based OELs is to slightly adjust the 3°C difference between acclimatized and unacclimatized workers with increasing differences due to metabolic rate. Our first step was to confirm that ΔOEL does not change with the metabolic rate for acclimatized participants; that is, the OEL adjusted for metabolic rate accounted for the trade-off between the environment and metabolic rate (24). The regression of ΔOEL for acclimatized participants had a slope that was not significantly different from zero, and the mean value of ΔOEL was 6.1°C. Thus, the OEL for acclimatized participants does reasonably account for the trade-off between metabolic rate and the WBGT limit. If the trade-off was the same for unacclimatized individuals, the slope would be zero with an intercept near 2.5°C. This was not the case as seen in Fig. 1. The difference between acclimatized and unacclimatized became smaller with increasing metabolic rate. Comparing the unacclimatized data to the OAL, there were 5 of 190 observations with metabolic rates below 130 W that fell below the OAL. These five observations indicated that the OAL was not sufficiently protective at low metabolic rates. If the OAL = OEL – 3°C, a constant difference, the OAL would be more protective at the lower metabolic rates. For either the current OAL or for one with a constant difference, the limit becomes progressively overprotective above a metabolic rate of 350 W; that is, the ULPZ data for unacclimatized are increasing higher than the OAL.

As shown in Table 3, men demonstrated a 1.4°C greater ΔOEL than women. A difference between sexes was found earlier among unacclimatized participants (15), but aerobic fitness did not explain the difference. When ΔOEL was regressed against body surface area (BSA), the relationship was positively correlated (see Fig. 2). This outcome can be explained by the increased ability to dissipate heat with larger BSA. The slope indicated that there was an 0.2°C increase in the ULPZ for each 0.1 m2 increase in BSA. BSA, however, did not fully account for the sex difference.

When the logit distributions of Fig. 1 and Eqs. 9 and 10 locate the median value of ΔOEL at P = 0.5, the difference was 3.6°C. That is, the mean and median values were essentially the same. The difference was not a surprise given a similar result for clothing when data were analyzed by ANOVA (13, 18) or from ln(odds) regression (22). In a similar comparison with a different set of unacclimatized participants at the ULPZ, Wolf et al. (15) reported a difference of ∼4°C at P = 0.50. The Wolf et al. paper (15) looked at high and low humidity rather than a broad range of humidity that is more likely in occupational exposures. The humidity extremes may have underestimated the level of heat stress (25).

The slopes for the two sexes were significantly different. One possibility was the proportion of men and women were different in the two studies. The unacclimatized data were evenly divided between men and women while the acclimatized data were roughly 2.5 times more men than women. As demonstrated earlier (see Table 3), there was a systematic difference between men and women where women were lower on average by 1.4°C.

The range between the low and high ends of the distributions was 6 and 10°C WBGT for unacclimatized and acclimatized populations, respectively. Because the range and slope were interrelated, the higher proportion of women could also explain the narrower range. Compared with the 3°C difference for acclimatization, this begs the question of who might optimally benefit from acclimatization. It appeared that only a few of the unacclimatized population exhibited a ULPZ that was less than the OEL. To the extent that the ULPZ marks their ability to sustain an exposure (11, 24), most of the PSU (unacclimatized) trials were greater than the OEL (ΔOEL = 0) as well as all the USF (acclimatized) trials.

Lind reported on 69 unacclimatized army personnel with various job duties. He reported that as a whole they were not active, and thus we treated them as unacclimatized. The data for the two exposures near his proposed limit and one well above the limit are also presented in Fig. 3. The displacement of the highest exposure to the right is partly due to the larger body surface areas of men in general. It is worth noting that this higher point is ∼3°C to the left of the acclimatized line. Recall that the exposures were adjusted for clothing but not acclimatization state. That means that at the OEL (ΔOEL = 0), 24 of 25 of his unacclimatized participants could sustain the heat stress exposure for 3 h.

This is not to say that the unacclimatized would not benefit from repeated exposures to heat stress (5). The USF and PSU data provide a picture of the ULPZ profiles but are still limited in the prediction for any individual. To further quantify the change in ULPZ due to acclimatization, the change observed in the same person in a pre- to postacclimatization study would provide more insight.

Because there is no promulgated standard for heat stress in the United States, the U.S. Occupational Safety and Health Administration (OSHA) uses the general duty clause to cite employers for insufficient heat stress protection. A review of 20 OSHA citations that occurred between 2012 and 2013 noted the absence of heat acclimatization programs in workplaces (26). Similarly, a review of 25 cases of heat-related illnesses and deaths from 2011 to 2016 found nearly half of the victims were in their first week of employment (27) and presumably unacclimatized to heat. If the probability is high that unacclimatized workers have an individual ULPZ above the OEL, then emphasizing an acclimatization program may be hiding other explanations. For instance, other individual risk factors (28) and the known carry-over effect from one day to the next (29–32).

Limitations

This paper has a number of important limitations that would need to be addressed in future research and policy development. There were differences in the number of men and women in the two populations. This may have some effect on interpreting and generalizing the results. The magnitude of the sex difference was 1.4°C, which is about half the difference assigned to changes in the acclimatization state. Part of that difference may be explained by body surface area. Regardless, other than acclimatization, personal risk factors are not included in occupational exposure limits. The participants for the PSU and USF were qualified as healthy.

To align the data between PSU and USF, a clothing adjustment value of −1°C was added to the observed WBGT at the critical condition. It is not likely that this value is far off and would not change the outcomes in a substantial way.

The overall framework used the individual ULPZ values to represent the individual’s and population’s ability to sustain a heat stress exposure. The Lind data extended the possible interpretation to 3 h. It is increasingly clear that the OELs may not account for lower capacity to deal with heat stress as the exposure continues over a day (33, 34).

Conclusions

When considering the average expected shift in the ULPZ due to acclimatization, the generally accepted 3°C adjustment for acclimatization was supported by the USF and PSU data. There was evidence that the current OEL reflects the trade-off between WBGT and metabolic rate. The OAL did not appear to represent a balanced trade-off for unacclimatized participants, where the current OAL may be less protective below 150 W. The current OAL may also be overprotective above 250 W.

Wolf et al. (15) reported sex differences using the progressive heat stress protocol and adjusting for absolute metabolic rate. The differences could not be explained by aerobic fitness. Body surface area could explain some of the sex differences.

The difference in slopes of the ULPZ profiles between unacclimatized and acclimatized populations suggested that the largest changes in ULPZ due to acclimatization might accrue to those with higher baseline ULPZ assuming that the acclimatization path travels in a horizontal line in Fig. 3. This is speculative and would need to be verified by comparing the changes in ULPZ before and after acclimatization within individuals.

A substantial portion of the ΔOEL above zero for unacclimatized participants reflects on policy and practice for occupational heat stress management. The first week of work in hot conditions is set aside for acclimatization. This acclimatization period could serve a dual purpose. First, the repeated exposures to occupational heat stress may improve the physiological response to heat for those with an ULPZ above the OEL. Second, closer attention should be paid to those (likely unknown) workers who may have personal risk factors such as chronic diseases or inherently low ability to sustain a heat stress exposure. That is, the first week allocated to acclimatization more generally becomes a time of increased vigilance for new or returning workers.

DATA AVAILABILITY

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.

GRANTS

The data reported in this paper were supported by CDC/NIOSH R01-OH03983 (to T. E. Bernard) and NIH R01-AG067471 (to W. L. Kenney). A. M. Odera was supported by the US Army for his studies at USF.

DISCLAIMERS

The authors declare no conflict of interest relating to the material presented in this article. Its contents, including any opinions and/or conclusions expressed, are solely those of the authors. One of the authors (T. E. Bernard) has acted as an expert witness for both private companies and OSHA in litigation concerning heat stress exposures and may serve as an expert witness in court proceedings related to heat stress in the future.

DISCLOSURES

No conflicts of interest, financial or otherwise, are declared by the authors.

W. Larry Kenney is an editor of Journal of Applied Physiology and was not involved and did not have access to information regarding the peer-review process or final disposition of this article. An alternate editor oversaw the peer-review and decision-making process for this article.

AUTHOR CONTRIBUTIONS

T.E.B., C.D.A., S.T.W., and W.L.K. conceived and designed research; T.E.B., C.D.A., S.T.W., and W.L.K. performed experiments; T.E.B., S.T.W., and A.M.O. analyzed data; T.E.B., C.D.A., S.T.W., A.M.O., R.M.L., and W.L.K. interpreted results of experiments; T.E.B. prepared figures; T.E.B., C.D.A., S.T.W., A.M.O., and R.M.L. drafted manuscript; T.E.B., C.D.A., S.T.W., A.M.O., R.M.L., and W.K. edited and revised manuscript; T.E.B., C.D.A., S.T.W., A.M.O., R.M.L., and W.L.K. approved final version of manuscript.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

The authors acknowledge the many laboratory assistants and trial participants who made this study possible. Ayub M. Odera’s MSPH thesis was the starting point for this paper.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bureau of Labor Statistics. 43 Work-Related Deaths Due to Environmental Heat Exposure in 2019 (Online). The Economics Daily, 2021. https://www.bls.gov/opub/ted/2021/43-work-related-deaths-due-to-environmental-heat-exposure-in-2019.htm [2023 Aug 5]. [Google Scholar]

- 2.US Department of Labor. OSHA Archive: Inspection Guidance for Heat-Related Hazards (Online). https://www.osha.gov/laws-regs/standardinterpretations/2021-09-01 [2023 August 5].

- 3.NASA Earth Observatory. Global Warming (Online). https://earthobservatory.nasa.gov/features/GlobalWarming/page2.php [2022 Jul 12].

- 4.NOAA Climate.gov. History of Earth’s Temperature Since 1880 (Online). https://www.climate.gov/news-features/videos/history-earths-temperature-1880#:~:text=For%20the%20last%2050%20years,over%20the%20previous%20half%2Dcentury [2022 Jul 12].

- 5. Périard JD, Racinais S, Sawka MN. Adaptations and mechanisms of human heat acclimation: applications for competitive athletes and sports. Scand J Med Sci Sports 25, Suppl 1: 20–38, 2015. doi: 10.1111/sms.12408. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6. Taylor NAS. Principles and practices of heat adaptation. J Hum Environ Syst 4: 11–22, 2000. doi: 10.1618/jhes.4.11. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 7. Tyler CJ, Reeve T, Hodges GJ, Cheung SS. The effects of heat adaptation on physiology, perception and exercise performance in the heat: a meta-analysis. Sports Med 46: 1699–1724, 2016. [Erratum in Sports Med 46: 1771, 2016]. doi: 10.1007/s40279-016-0538-5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8. Jacklitsch B, Williams WJ, Musolin K, Coca A, Kim J-H, Turner N.. NIOSH Criteria for a Recommended Standard: Occupational Exposure to Heat and Hot Environments. Cincinnati, OH: Department of Health and Human Services, Centers for Disease Control and Prevention, National Institute for Occupational Safety and Health (DHHS (NIOSH) Publication No. 2016-106), 2016. [Google Scholar]

- 9.ACGIH. TLV for Heat Stress and Strain. Threshold Limit Values and Biological Exposure Indices for Chemical Substances and Physical Agents. Cincinnati, OH: ACGIH, 2023. [Google Scholar]

- 10.ISO. ISO 7243:2017 Ergonomics of the Thermal Environment—Assessment of Heat Stress using the WBGT (Wet Bulb Globe Temperature) Index. Geneva: ISO, 2017. [Google Scholar]

- 11. Lind AR. A physiological criterion for setting thermal environmental limits for everyday work. J Appl Physiol 18: 51–56, 1963. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1963.18.1.51. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12. Belding HS, Kamon E. Evaporative coefficients for prediction of safe limits in prolonged exposures to work under hot conditions. Fed Proc 32: 1598–1601, 1973. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13. Bernard TE, Caravello V, Schwartz SW, Ashley CD. WBGT clothing adjustment factors for four clothing ensembles and the effects of metabolic demands. J Occup Environ Hyg 5: 1–5, 2008. doi: 10.1080/15459620701732355. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14. Garzón-Villalba XP, Wu Y, Ashley CD, Bernard TE. Ability to discriminate between sustainable and unsustainable heat stress exposures. I. WBGT exposure limits. Ann Work Expo Health 61: 611–620, 2017. doi: 10.1093/annweh/wxx034. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15. Wolf ST, Bernard TE, Kenney WL. Heat exposure limits for young unacclimatized males and females at low and high humidity. J Occup Environ Hyg 19: 415–424, 2022. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2022.2076859. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16. Wolf ST, Cottle RM, Vecellio DJ, Kenney WL. Critical environmental limits for young, healthy adults (PSU HEAT). J Appl Physiol 132: 327–333, 2021. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00737.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17. Cottle RM, Lichter ZS, Vecellio DJ, Wolf ST, Kenney WL. Core temperature responses to compensable vs. uncompensable heat stress in young adults (PSU Heat Project). J Appl Physiol 133: 1011–1018, 2022. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00388.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18. Bernard TE, Luecke CL, Schwartz SW, Kirkland KS, Ashley CD. WBGT clothing adjustments for four clothing ensembles under three relative humidity levels. J Occup Environ Hyg 2: 251–256, 2005. doi: 10.1080/15459620590934224. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19. Wolf ST, Cottle RM, Vecellio DJ, Kenney WL. Critical environmental limits for young, healthy adults (PSU HEAT Project). J Appl Physiol (1985) 132: 327–333, 2022. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00737.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20. Cottle RM, Lichter ZS, Vecellio DJ, Wolf ST, Kenney WL. Core temperature responses to compensable versus uncompensable heat stress in young adults (PSU HEAT Project). J Appl Physiol (1985) 133: 1011–1018, 2022. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00388.2022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21. Cottle RM, Wolf ST, Lichter ZS, Kenney WL. Validity and reliability of a protocol to establish human critical environmental limits (PSU HEAT Project). J Appl Physiol (1985) 132: 334–339, 2022. doi: 10.1152/japplphysiol.00736.2021. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22. Garzón-Villalba XP, Wu Y, Ashley CD, Bernard TE. Heat stress risk profiles for three non-woven coveralls. J Occup Environ Hyg 15: 80–85, 2018. doi: 10.1080/15459624.2017.1388514. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23. Lind AR. Effect of individual variation on upper limit of prescriptive zone of climates. J Appl Physiol 28: 57–62, 1970. doi: 10.1152/jappl.1970.28.1.57. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24. Dukes-Dobos FN, Henschel A. Development of permissible heat exposure limits for occupational work. Am Soc Heating Refrig Air Cond Eng J 15: 57–62, 1973. [Google Scholar]

- 25. Budd GM. Wet-bulb globe temperature (WBGT)—its history and its limitations. J Sci Med Sport 11: 20–32, 2008. doi: 10.1016/j.jsams.2007.07.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26. Arbury S, Lindsley M, Hodgson M. A critical review of OSHA heat enforcement cases: lessons learned. J Occup Environ Med 58: 359–363, 2016. doi: 10.1097/JOM.0000000000000640. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27. Tustin AW, Lamson GE, Jacklitsch BL, Thomas RJ, Arbury SB, Cannon DL, Gonzales RG, Hodgson MJ. Evaluation of occupational exposure limits for heat stress in outdoor workers—United States, 2011–2016. MMWR Morb Mortal Wkly Rep 67: 733–737, 2018. doi: 10.15585/mmwr.mm6726a1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28. Notley SR, Flouris AD, Kenny GP. Occupational heat stress management: does one size fit all? Am J Ind Med 62: 1017–1023, 2019. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22961. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29. Garzon-Villalba XP, Mbah A, Wu Y, Hiles M, Moore H, Schwartz SW, Bernard TE. Exertional heat illness and acute injury related to ambient wet bulb globe temperature. Am J Ind Med 59: 1169–1176, 2016. doi: 10.1002/ajim.22650. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30. Wallace RF, Kriebel D, Punnett L, Wegman DH, Wenger CB, Gardner JW, Gonzalez RR. The effects of continuous hot weather training on risk of exertional heat illness. Med Sci Sports Exerc 37: 84–90, 2005. doi: 10.1249/01.mss.0000150018.90213.aa. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31. Shire J, Vaidyanathan A, Lackovic M, Bunn T. Association between work-related hyperthermia emergency department visits and ambient heat in five southeastern states, 2010–2012—a case-crossover study. Geohealth 4: e2019GH000241, 2020. doi: 10.1029/2019GH000241. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32. Schlader ZJ, Colburn D, Hostler D. Heat strain is exacerbated on the second of consecutive days of fire suppression. Med Sci Sports Exerc 49: 999–1005, 2017. doi: 10.1249/MSS.0000000000001191. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33. Sahu S, Sett M, Kjellstrom T. Heat exposure, cardiovascular stress and work productivity in rice harvesters in India: implications for a climate change future. Ind Health 51: 424–431, 2013. doi: 10.2486/indhealth.2013-0006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34. Smallcombe JW, Foster J, Hodder SG, Jay O, Flouris AD, Havenith G. Quantifying the impact of heat on human physical work capacity. IV. Interactions between work duration and heat stress severity. Int J Biometeorol 66: 2463–2476, 2022. doi: 10.1007/s00484-022-02370-7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Data Availability Statement

Data will be made available upon reasonable request.