Abstract

For the past two decades, the study of alternative splicing (AS) and its involvement in plant development and stress response has grown in popularity. Only recently however, has the focus shifted to the study of how AS regulation (or lack-thereof) affects downstream mRNA and protein landscapes and how these AS regulatory events impact plant development and stress tolerance. In humans, protein phosphorylation represents one of the predominant mechanisms by which AS is regulated and thus the protein kinases governing these phosphorylation events are of interest for further study. Large-scale phosphoproteomic studies in plants have consistently found that RNA splicing-related proteins are extensively phosphorylated, however, the signaling pathways involved in AS regulation have not been resolved. In this mini-review, we summarize our current knowledge of the three major splicing-related protein kinase families in plants that are suggested to mediate AS phospho-regulation and draw comparisons to their metazoan orthologs. We also summarize and contextualize the phosphorylation events identified as occurring on splicing-related protein families to illustrate the high degree to which splicing-related proteins are modified, placing a new focus on elucidating the impacts of AS at the protein and PTM-level.

Keywords: phosphorylation, protein kinases, RNA splicing, proteomics, regulation

1. Introduction

Alternative splicing (AS) is of particular importance for plants, with upwards of ~40-80% of multi-exonic genes undergoing AS (Filichkin et al., 2010; Marquez et al., 2012; Thatcher et al., 2014; Chen et al., 2020; Liu et al., 2022). Correspondingly, plants possess a wide range of spliceosome-related proteins, of which, serine/arginine-rich (SR) proteins and heterogeneous nuclear ribonuclear proteins (hnRNPs) function as positive and negative regulators of RNA splicing, respectively (Barta et al., 2010; Busch and Hertel, 2012; Erkelenz et al., 2013). Many of the genes encoding plant SR proteins are themselves alternatively spliced in response to wide-range of environmental changes, including: changes in light (Filichkin et al., 2010; Petrillo et al., 2014; Tognacca et al., 2019), temperature (Calixto et al., 2018; Li et al., 2021c; Ling et al., 2021), osmolarity (Tanabe et al., 2007; Ding et al., 2014; Albaqami et al., 2019), amongst others (Lazar and Goodman, 2000; Isshiki et al., 2006; Hartmann et al., 2018), with these AS events found to confer stress tolerance in an isoform-dependent manner (Albaqami et al., 2019). Examination of SR protein over-expression and loss-of-function plant lines have shown a variety of developmental phenotypes (Ishizawa et al., 2019; Xu et al., 2019; Lee et al., 2020b) and impacts on gene expression (Hartmann et al., 2016; Wu et al., 2016; Yan et al., 2017), with many of these studies uncovering developmental ramifications as a result of dysregulated AS. However, the ways in which AS is regulated through post-translational modifications (PTMs), such as phosphorylation, has only recently become of interest.

In human cells, AS regulates essential functions such as autophagy (Paronetto et al., 2016; Lv et al., 2021), apoptosis (Singh et al., 2016; Kędzierska and Piekiełko-Witkowska, 2017; Stevens and Oltean, 2019), protein localization (Link et al., 2016), and transcription factor activity (Chen et al., 2022), amongst others (Baralle and Giudice, 2017). Therefore, it is no surprise that AS dysregulation results in several medical conditions including: cancer (Da Silva et al., 2015; Wang et al., 2016), heart disease (Liu et al., 2019; Hasimbegovic et al., 2021), neurological disorders (Low et al., 2021; Zhang et al., 2022; Nishanth and Jha, 2023) and multiple genetic disorders (Maule et al., 2019; Ajiro et al., 2021; Jiang and Chen, 2021). Hence in humans, PTM regulation and the signaling pathways governing AS, have been extensively studied, offering opportunities for comparative analysis of new findings being made in plants.

Comparative analyses of human and plant AS regulation have highlighted the largely conserved functionality of AS across eukaryotes, while also revealing unique AS regulation specific to plants (Chaudhary et al., 2019). In both humans and plants, phosphorylation of SR proteins has been found to induce nucleocytoplasmic shuttling (Rausin et al., 2010; Botti et al., 2017; Park et al., 2017), to initiate binding on pre-mRNA (Zhou and Fu, 2013), and facilitate spliceosome assembly (Saha and Ghosh, 2022). In humans, the interactive networks between splicing-related protein kinases and their SR protein substrates are an active area of research, revealing roles in the regulation of vascular endothelial growth factor A (VEGF-A) signaling (Li et al., 2021b), protein kinase B (AKT)/ERK pathways (Zhou et al., 2012), along with the targeting of rapamycin complex 1 (mTORC1)/ribosomal S6 kinase 1 (S6K1) (Lee et al., 2018) pathway; all of which involve human SRPK (HsSRPK) phosphorylation of SR proteins. CDC2-LIKE KINASEs (CLKs), alongside HsSRPK1, have also been shown to be involved in SR protein mediated AS (Aubol et al., 2003; Ngo et al., 2005; Kulkarni et al., 2017). However, in plants, the intricate links between signal transduction, protein phosphorylation, and AS is just beginning to emerge.

In this mini-review, we describe the current state of splicing-related protein kinase research in plants, relating this knowledge to our established understanding of these proteins kinases in humans. We then examine the extent to which splicing-related proteins are phosphorylated and touch upon AS dysregulation in plants. Finally, we briefly discuss what is next for understanding plant AS from a protein-centric perspective and the implications behind PTM-level regulation.

1.1. Splicing-related protein kinases: An overview

Splicing-related protein kinases are conventionally categorized by their ability to phosphorylate splicing factors or components of the spliceosome. Here we summarize the roles and current understanding of the three major splicing-related protein kinase families studied in plants, focusing on the model plant Arabidopsis where most of the recent research has emerged.

1.1.1. Serine arginine protein kinases

The Arabidopsis SRPK family (AtSRPKs) consists of five members divided into two groups: Group I (SRPK1: AT4G35500, and SRPK2: AT2G17530) and Group II (SRPK3: AT5G22840, SRPK4: AT3G53030, SRPK5: AT3G44850) SRPKs (Rodriguez Gallo et al., 2022). These AtSRPK groupings first become clear with the emergence of spermatophytes, suggesting duplication of the family early in the land plant lineage. SRPK peptide sequences are characterized by a bi-partite kinase domain separated by a spacer region, which is conserved across both the animal and plant kingdoms. The SRPK spacer domain has been found to be required for the nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of HsSRPKs, but not necessary for their kinase activity (Ding et al., 2006; Koutroumani et al., 2017; Sigala et al., 2021). Nonetheless, the presence of the spacer domain has been shown to increase HsSRPK phosphorylation rate by facilitating nucleotide release (Plocinik et al., 2011; Aubol et al., 2012). Although the function of the spacer domain of AtSRPKs remains to be determined, it most likely aids in nucleocytoplasmic shuttling similar to its human orthologs as localization experiments of Group II AtSRPKs have demonstrated both nuclear and cytoplasmic localizations (Wang et al., 2023).

HsSRPK have been implicated in various developmental and stress-related pathways. Similarly, AtSRPKs seem to be involved in a variety of biological processes. For example, AtSRPK1 seems to be stress-induced due to its transcriptional up-regulation under various abiotic stresses (cold, heat, osmotic, salt) (Rodriguez Gallo et al., 2022). Further, all AtSRPKs exhibit diel regulation, with peak transcriptional expression occurring mid-night (ZT18) in seedlings, suggesting that AtSRPKs may be a part of circadian regulated processes or involved in circadian mediated AS events. Accordingly, Group II AtSRPK loss-of-function lines displayed a late-flowering phenotype and an up-regulation of FLOWERING LOCUS C (FLC) gene expression; the major negative regulator of flowering (Wang et al., 2023). In the same study, Group II AtSRPKs were implicated in the phosphorylation of a number of SR proteins and beyond, including proteins involved in ribosome biogenesis, abiotic stress, hormone signaling and carbohydrate responses. The authors found phosphorylation motifs ‘xxxxxxSPxxxxx’ and xxxxSxSxxxxxx’ to be enriched amongst differentially abundant phosphorylation events in Group II deficient (sprk3 4 5/sprkii-1) plants and suggested they may be Group II specific phosphorylation motifs.

1.1.2. Arabidopsis Fus3 complement

There are three members comprising the AFC family in Arabidopsis: AFC1 (AT3G53570), AFC2 (AT4G24740), and AFC3 (AT4G32660). AFCs belong to the family of LAMMER kinases, which are characterized by a conserved ‘AHLAMMERILG’ motif in their catalytic kinase domain that is important for substrate recognition (Lee et al., 1996; Kang et al., 2010) as well as their dual tyrosine and serine/threonine kinase activity profile (Ben-David et al., 1991; Yun et al., 1994). In humans, the CLKs represent the AFC orthologs of plants and have been shown to phosphorylate a multitude of substrates, including SR proteins (Ngo et al., 2005; Varjosalo et al., 2013). CLKs bind to SR proteins but lack the mechanism to release phosphorylated SR proteins, requiring an HsCLK/HsSRPK complex for the release of SR proteins (Aubol et al., 2016; Aubol et al., 2018). In Arabidopsis, AFCs have been found to phosphorylate plant SR proteins in vitro (Lin et al., 2022), however, the extent to which AFCs phosphorylate non-SR proteins remains unknown.

Phylogenetic analysis of the photosynthetic eukaryote AFCs indicates that the AFC3 group diverged in gymnosperms, while the AFC1 and AFC2 groups emerged later with the evolution of monocots, suggesting that these AFCs may perform non-redundant functions specific to flowering plants (Rodriguez Gallo et al., 2022). To date, AtAFCs have been implicated in thermoregulation, of which AtAFC2 controls high-temperature AS, with afc2 loss-of-function plants exhibiting aberrant splicing patterns under high temperatures (Lin et al., 2022). Furthermore, AtAFC2 gene expression in shoot tissue is significantly up-regulated under cold stress (Rodriguez Gallo et al., 2022). Connections have also been drawn between temperature, flowering, and AS, with the major spliceform of FLOWERING LOCUS M (FLM) contributing to temperature-responsive flowering in Arabidopsis (Capovilla et al., 2015; Jin et al., 2022). Furthermore, Arabidopsis splicing factor 1 (SF1) interacts with FLM pre-mRNA in a temperature-dependent manner, inducing the production of FLM-β transcripts, and thus modulating flowering time in response to temperature fluctuations (Lee et al., 2020b). Similarly, the metazoan CLKs also have roles in temperature-dependent AS, whereby lower body temperatures activate HsCLKs, resulting in high SR protein phosphorylation both in vitro and in vivo (Haltenhof et al., 2020). The same study also connects CLK temperature-dependent activity with the circadian-regulation of internal body temperature. Similarly, AtAFCs are also expressed in a diel manner, with peak expression occurring mid-night (ZT18) (Rodriguez Gallo et al., 2022).

1.1.3. Pre-mRNA processing factor 4 protein kinases

The last major family of characterized splicing kinases are the PRP4Ks. There are three members to the Arabidopsis PRP4K family: PRP4Ka (AT3G25840), PRP4kb (AT1G13350), and PRP4Kc (AT3G53640). PRP4Ks were the first protein kinases to be characterized to have a regulatory impact on mRNA splicing in both fungi and mammals (Ltzelberger and Käufer, 2012). HsPRP4K is encoded by a single gene (PRPF4B) and is a snRNP-associated kinase. Similar to HsCLKs, HsPRP4K is also a dual-specificity kinase, but unlike the other two families of splicing-related protein kinases, HsPRP4K has been found to associate with major spliceosome proteins (Dellaire et al., 2002) and is required for the formation of the early spliceosome (Schneider et al., 2010). In humans, HsPRP4K plays an essential role in ovarian and other epithelial cancers, with a reduction in HsPRP4K levels leading to anoikis sensitivity (Corkery et al., 2018). To date, our understanding of PRP4Ks across plants is lacking, with only atprp4ka loss-of-function plants being phenotypically and biochemically characterized. Here, phosphoproteomic data identified multiple SR splicing factors (e.g. AtSR30, AtRS41, AtRS40, AtSCL33, and AtSCL30A) as possessing significant changes in their phosphorylation status compared to wild-type plants (Kanno et al., 2018).

1.2. Phosphorylation of splicing-related proteins

1.2.1. Phosphorylation abundance

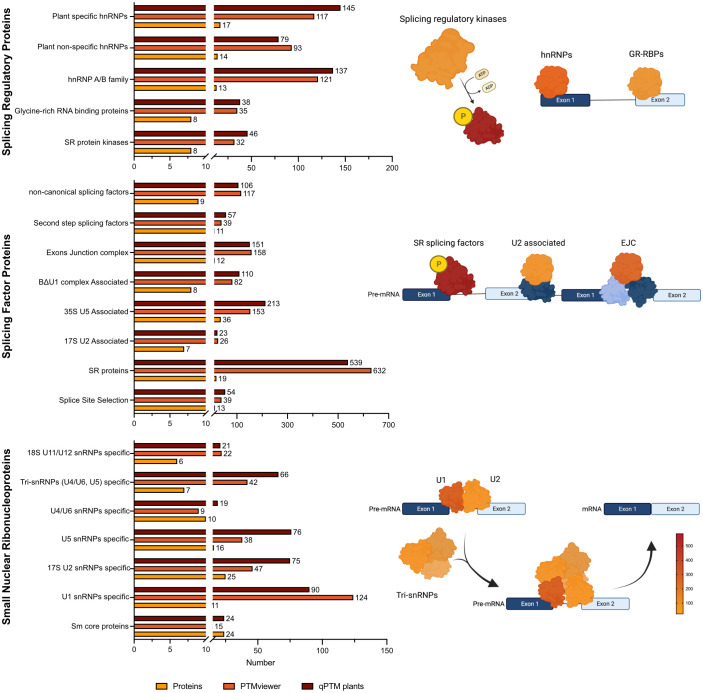

The phosphorylation state of SR proteins can change their activity (Xiang et al., 2013; Keshwani et al., 2015), localization (Stankovic et al., 2016), interaction with other proteins and/or RNA to initiate RNA splicing reactions (Kim et al., 2015). Further, Arabidopsis splicing-related proteins have been reported to be extensively phosphorylated in large-scale phosphorproteomic studies (De La Fuente Van Bentem et al., 2006; Marondedze et al., 2016; Mehta et al., 2021). Using plant SPEAD (Chen et al., 2021; http://chemyang.ccnu.edu.cn/ccb/database/PlantSPEAD/index.php), in conjunction with PTM containing databases: PTMviewer (Willems et al., 2019; https://www.psb.ugent.be/webtools/ptm-viewer/index.php) and qPTM plants (Xue et al., 2022; http://qptmplants.omicsbio.info/), the extent to which diverse splicing-related protein families are phosphorylated highlights the need to resolve the function of these regulatory events ( Figure 1 ).

Figure 1.

Number of unique protein phosphorylation events identified on splicing-related proteins in Arabidoposis. Identified phosphosites were collected from PTMviewer (Willems et al., 2019; https://www.psb.ugent.be/webtools/ptm-viewer/index.php) and qPTM (Xue et al., 2022; http://qptmplants.omicsbio.info/). Selection and categorization of splicing-related proteins were acquired from plantSPEAD (Chen et al., 2021; http://chemyang.ccnu.edu.cn/ccb/database/PlantSPEAD/index.php) and the number of proteins related to each family is plotted. Number of phosphorylation events for select protein families were converted to a colour intensity gradient.

In Arabidopsis, studies show that the most highly phosphorylated splicing-related proteins are plant specific hnRNPs and the A/B hnRNP family, followed by plant non-specific hnRNPs ( Figure 1 ). The hnRNPs were originally discovered by electron micrographs (Gall, 1956) in metazoans and in the years following, were characterized biochemically (Samarina et al., 1966), and then categorized for their binding to nascent transcripts (Beyer et al., 1977). The hnRNPs are involved in a diverse set of processes such as telomere maintenance (Kwon and Chung, 2004; Lee and Kim, 2010; Shishkin et al., 2019), transcription (Li and Liu, 2010; Rauch et al., 2010; Molitor et al., 2016), and pre-mRNA splicing (Tange et al., 2001; Dreyfuss et al., 2002; Streitner et al., 2012; Geuens et al., 2016). Moreover, human hnRNPs undergo nucleocytoplasmic shuttling which has been proposed to be a way of transporting mRNA to the cytoplasm (Beyer et al., 1977; Yeap et al., 2019; Dabral et al., 2020). In the context of RNA splicing, hnRNPs are antagonistic partners to SR splicing factors, where upon binding to splicing silencing sequences on the pre-mRNA, function to repress the formation of early spliceosome (Wang et al., 2004; Matlin et al., 2005; Rahman et al., 2015; Lin et al., 2020). Due to their involvement in the multiple stages of mRNA transcription, maturation, and shuttling, their regulation must be finely tuned and as such, a high-degree of phosphorylation could be expected.

Interestingly, SR proteins have almost five times more phosphorylation events than any other splicing factor protein group in Arabidopsis ( Figure 1 ). In humans, SR proteins play crucial roles in multiple stages of mRNA maturation, including: splice site selection (Jia et al., 2019; Li et al., 2021a), recruitment of spliceosome proteins (Cho et al., 2011), facilitating mRNA transport to the cytosol (Müller-McNicoll et al., 2016; Jeong, 2017), and mRNA stability (Howard and Sanford, 2015; Grosse et al., 2021). They serve as key determinants of specificity and are believed to integrate multiple signaling pathways mediated by phosphorylation through SRPKs. Human SR proteins are categorized as containing one or two RNA-recognition motifs (RRMs) at their N-termini and a C-terminal RS domain containing at least 50 amino acids with > 40% RS/SR content dipeptide repeats (Manley and Krainer, 2010; Howard and Sanford, 2015) While plant SR proteins are categorized as having one or two RRMs on the N-terminus and a downstream RS domain of at least 50 amino acids and a minimum of 20% RS/SR dipeptide repeats (Barta et al., 2010).

Certain SR proteins shuttle between the nucleus and the cytoplasm depending on their phosphorylation status. The subcellular trafficking of SR proteins is more resolved in humans, with the phosphorylation by HsSRPKs and hyperphosphorylation by CLKs being the driving force behind shuttling SR proteins from the cytoplasm to nucleus and from nuclear speckles to areas of nascent pre-mRNA (Lai et al., 2000; Ngo et al., 2005; Ghosh and Adams, 2011; Jang et al., 2019). As such their movement is highly contingent on their phosphorylation status. In plants, phosphorylation-mediated SR shuttling has also been documented (Tillemans et al., 2006; Rausin et al., 2010; Stankovic et al., 2016; Park et al., 2017). Recently, fluorescent co-localization experiments have determined that the phosphorylation of certain splicing factors by Group II AtSRPKs induced their nucleocytoplasmic shuttling (Wang et al., 2023). But the specific phosphorylation events and upstream signals/signaling pathways driving the shuttling of SR proteins to the nucleus and then to active splice sites remains to be fully characterized.

Lastly, we find that U1 snRNPs are the most highly phosphorylated snRNP group in Arabidopsis ( Figure 1 ). U1 snRNPs are partly responsible for splice site selection (Lacadie and Rosbash, 2005; Kondo et al., 2015), inducing the ordered assembly of the remaining snRNPs to form the early and catalytic spliceosome (Cho et al., 2011). Metazoan U1 snRNP performs functions beyond pre-mRNA splicing, for instance, it is important for mRNA 3’ end cleavage (Kaida et al., 2010), polyadenylation (Ashe et al., 1997; Berg et al., 2012) and transcription (Chiu et al., 2018). The function of the plant U1 snRNP is not well characterized, with some evidence of human U1 snRNP interacting with SR proteins, suggesting a complex interaction for splice site selection (Chiu et al., 2018). It is conceivable that proteins involved in the fundamental steps of RNA splicing would require extensive phosphorylation to ensure accurate and timely initiation of AS.

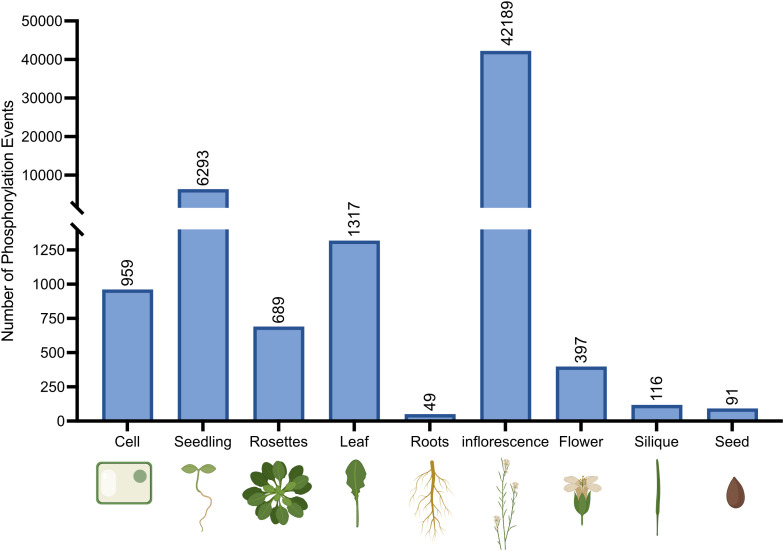

1.3. Tissue specific phospho-regulation of splicing-related proteins

In humans, there is a high degree of tissue-specific AS events in which the inclusion levels of certain exons differ. Correspondingly, these AS events are termed tissue-specific (TS) exons (Clark et al., 2007; Buljan et al., 2012). Therefore, we compiled the phosphorylation events identified as occurring on splicing-related proteins based on tissue type using the PTMviewer data repository ( Figure 2 ). Here, Arabidopsis tissues related to reproduction (inflorescences and flowers) exhibit a high degree of splicing-related protein phosphorylation. Many exogeneous and endogenous cues determine flowering timing, including: photoperiod (Kang et al., 2015; Nakamichi, 2015; Seaton et al., 2015), temperature (Lee et al., 2020a; Cao et al., 2021; Jin and Ahn, 2021), and aging (Jung et al., 2016; Hyun et al., 2017). Further, flowering is in part regulated through AS variants that either repress or promote flowering, such as FLC and CONSTANS (CO) (Park et al., 2019). The AS variants of these genes can be specifically produced in response to environmental cues and thus require finely tuned activation of specific splicing factors.

Figure 2.

Number of unique protein phosphorylation events identified on splicing-related proteins in Arabidopsis tissues. Tissue-specific phosphosites were collected from PTMviewer (Willems et al., 2019; https://www.psb.ugent.be/webtools/ptm-viewer/index.php).

Surprisingly, root tissue was found to have the lowest number of phosphorylation events. This may be due to: 1) root tissues being under sampled in phosphoproteomic databases, or 2) regulatory differences exist in roots relative to other tissues. Interestingly however, the application of GEX1A and Pladienolide B (PB), both spliceosome specific inhibitors in humans, produced short root phenotypes in Arabidopsis seedlings (AlShareef et al., 2017; Ishizawa et al., 2019), suggesting spliceosome function is integral for root development. Although both studies explored the transcriptional landscape changes in inhibited tissues, neither study analyzed the phosphoproteome. Therefore, it may be possible that fewer, more integral phosphorylation events are necessary for normal root growth and development.

2. Concluding remarks

The study of AS and its regulation through PTMs represents an exciting new avenue of research for plant biology and plant cell regulation. Acquired proteomic data relating the intersection of protein phosphorylation and AS has gained momentum over the last five years, with the characterization of splicing-related protein kinases now emerging. Through the comparison of metazoans to plants, it is evident that many aspects of the AS regulatory machinery is evolutionarily conserved, however, the extent to which this machinery is functionally conserved remains to be uncovered.

Author contributions

MCRG and RU contributed to the writing of this review. All authors contributed to the article and approved the submitted version.

Funding Statement

The study of plant alternative splicing and proteomics has been supported by the Natural Sciences and Engineering Research Council of Canada (NSERC).

Conflict of interest

The authors declare that the research was conducted in the absence of any commercial or financial relationships that could be construed as a potential conflict of interest.

Publisher’s note

All claims expressed in this article are solely those of the authors and do not necessarily represent those of their affiliated organizations, or those of the publisher, the editors and the reviewers. Any product that may be evaluated in this article, or claim that may be made by its manufacturer, is not guaranteed or endorsed by the publisher.

References

- Ajiro M., Awaya T., Kim Y. J., Iida K., Denawa M., Tanaka N., et al. (2021). Therapeutic manipulation of IKBKAP mis-splicing with a small molecule to cure familial dysautonomia. Nat. Commun. 12, 1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41467-021-24705-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Albaqami M., Laluk K., Reddy A. S. N. (2019). The Arabidopsis splicing regulator SR45 confers salt tolerance in a splice isoform-dependent manner. Plant Mol. Biol. 100, 379–390. doi: 10.1007/s11103-019-00864-4 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- AlShareef S., Ling Y., Butt H., Mariappan K. G., Benhamed M., Mahfouz M. M. (2017). Herboxidiene triggers splicing repression and abiotic stress responses in plants. BMC Genomics 18, 1–16. doi: 10.1186/s12864-017-3656-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ashe M. P., Pearson L. H., Proudfoot N. J. (1997). The HIV-1 5’ LTR poly (A) site is inactivated by U1 snRNP interaction with the downstream major splice donor site. EMBO J. 16, 5752–5763. doi: 10.1093/emboj/16.18.5752 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubol B. E., Chakrabarti S., Ngo J., Shaffer J., Nolen B., Fu X. D., et al. (2003). Processive phosphorylation of alternative splicing factor/splicing factor 2. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 100, 12601–12606. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1635129100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubol B. E., Keshwani M. M., Fattet L., Adams J. A. (2018). Mobilization of a splicing factor through a nuclear kinase–kinase complex. Biochem. J. 475, 677–690. doi: 10.1042/BCJ20170672 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubol B. E., Plocinik R. M., McGlone M. L., Adams J. A. (2012). Nucleotide release sequences in the protein kinase SRPK1 accelerate substrate phosphorylation. Biochemistry 51, 6584–6594. doi: 10.1021/bi300876h [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aubol B. E., Wu G., Keshwani M. M., Movassat M., Fattet L., Hertel K. J., et al. (2016). Release of SR proteins from CLK1 by SRPK1: A symbiotic kinase system for phosphorylation control of pre-mRNA splicing. Mol. Cell 63, 218–228. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2016.05.034 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Baralle F. E., Giudice J. (2017). Alternative splicing as a regulator of development and tissue identity. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 18, 437–451. doi: 10.1038/nrm.2017.27 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barta A., Kalyna M., Reddy A. S. N. (2010). Implementing a rational and consistent nomenclature for serine/arginine-rich protein splicing factors (SR proteins) in plants. Plant Cell 22, 2926–2929. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.078352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ben-David Y., Letwin K., Tannock L., Bernstein A., Pawson T. (1991). A mamMalian protein kinase with potential for serine/threonine and tyrosine phosphorylation is related to cell cycle regulators. EMBO J. 10, 317–325. doi: 10.1002/j.1460-2075.1991.tb07952.x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Berg M. G., Singh L. N., Younis I., Liu Q., Pinto A. M., Kaida D., et al. (2012). U1 snRNP determines mRNA length and regulates isoform expression. Cell 150, 53–64. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2012.05.029 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Beyer A. L., Christensen M. E., Walker B. W., LeStourgeon W. M. (1977). Identification and characterization of the packaging proteins of core 40S hnRNP particles. Cell 11, 127–138. doi: 10.1016/0092-8674(77)90323-3 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Botti V., McNicoll F., Steiner M. C., Richter F. M., Solovyeva A., Wegener M., et al. (2017). Cellular differentiation state modulates the mRNA export activity of SR proteins. J. Cell Biol. 216, 1993–2009. doi: 10.1083/jcb.201610051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Buljan M., Chalancon G., Eustermann S., Wagner G. P., Fuxreiter M., Bateman A., et al. (2012). Tissue-specific splicing of disordered segments that embed binding motifs rewires protein interaction networks. Mol. Cell 46, 871–883. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Busch A., Hertel K. J. (2012). Evolution of SR protein and hnRNP splicing regulatory factors. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 3, 1–12. doi: 10.1002/wrna.100 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Calixto C. P. G., Guo W., James A. B., Tzioutziou N. A., Entizne J. C., Panter P. E., et al. (2018). Rapid and dynamic alternative splicing impacts the arabidopsis cold response transcriptome. Plant Cell 30, 1424–1444. doi: 10.1105/tpc.18.00177 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cao S., Luo X., Xu D., Tian X., Song J., Xia X., et al. (2021). Genetic architecture underlying light and temperature mediated flowering in Arabidopsis, rice, and temperate cereals. New Phytol. 230, 1731–1745. doi: 10.1111/nph.17276 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Capovilla G., Pajoro A., Immink R. G. H., Schmid M. (2015). Role of alternative pre-mRNA splicing in temperature signaling. Curr. Opin. Plant Biol. 27, 97–103. doi: 10.1016/j.pbi.2015.06.016 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chaudhary S., Khokhar W., Jabre I., Reddy A. S. N., Byrne L. J., Wilson C. M., et al. (2019). Alternative splicing and protein diversity: Plants versus animals. Front. Plant Sci. 10. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00708 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. X., Mei L. C., Wang F., Boyagane Dewayalage I. K. W., Yang J. F., Dai L., et al. (2021). PlantSPEAD: a web resource towards comparatively analysing stress-responsive expression of splicing-related proteins in plant. Plant Biotechnol. J. 19, 227–229. doi: 10.1111/pbi.13486 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M., Sun Y., Qian Y., Chen N., Li H., Wang L., et al. (2022). Case report: FOXP1 syndrome caused by a de novo splicing variant (c.1652+5 G>A) of the FOXP1 gene. Front. Genet. 13. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2022.926070 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chen M. X., Zhu F. Y., Gao B., Ma K. L., Zhang Y., Fernie A. R., et al. (2020). Full-length transcript-based proteogenomics of rice improves its genome and proteome annotation. Plant Physiol. 182, 1510–1526. doi: 10.1104/PP.19.00430 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chiu A. C., Suzuki H. I., Wu X., Mahat D. B., Kriz A. J., Sharp P. A. (2018). Transcriptional pause sites delineate stable nucleosome-associated premature polyadenylation suppressed by U1 snRNP. Mol. Cell 69, 648–663.e7. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2018.01.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cho S., Hoang A., Sinha R., Zhong X. Y., Fu X. D., Krainer A. R., et al. (2011). Interaction between the RNA binding domains of Ser-Arg splicing factor 1 and U1-70K snRNP protein determines early spliceosome assembly. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 108, 8233–8238. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1017700108 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Clark T. A., Schweitzer A. C., Chen T. X., Staples M. K., Lu G., Wang H., et al. (2007). Discovery of tissue-specific exons using comprehensive human exon microarrays. Genome Biol. 8, R64. doi: 10.1186/gb-2007-8-4-r64 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Corkery D. P., Clarke L. E., Gebremeskel S., Salsman J., Pinder J., Le Page C., et al. (2018). Loss of PRP4K drives anoikis resistance in part by dysregulation of epidermal growth factor receptor endosomal trafficking. Oncogene 37, 174–184. doi: 10.1038/onc.2017.318 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dabral P., Babu J., Zareie A., Verma S. C. (2020). LANA and hnRNP A1 Regulate the Translation of LANA mRNA through G-Quadruplexes. J. Virol. 94, e01508-19. doi: 10.1128/jvi.01508-19 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Da Silva M. R., Moreira G. A., Gonçalves Da Silva R. A., De Almeida Alves Barbosa É., Pais Siqueira R., Teixera R. R., et al. (2015). Splicing regulators and their roles in cancer biology and therapy. BioMed. Res. Int. 2015. doi: 10.1155/2015/150514 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- De La Fuente Van Bentem S., Anrather D., Roitinger E., Djamei A., Hufnagl T., Barta A., et al. (2006). Phosphoproteomics reveals extensive in vivo phosphorylation of Arabidopsis proteins involved in RNA metabolism. Nucleic Acids Res. 34, 3267–3278. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkl429 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dellaire G., Makarov E. M., Cowger J. M., Longman D., Sutherland H. G. E., Lührmann R., et al. (2002). MamMalian PRP4 kinase copurifies and interacts with components of both the U5 snRNP and the N-coR deacetylase complexes. Mol. Cell. Biol. 22, 5141–5156. doi: 10.1128/mcb.22.14.5141-5156.2002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding F., Cui P., Wang Z., Zhang S., Ali S., Xiong L. (2014). Genome-wide analysis of alternative splicing of pre-mRNA under salt stress in Arabidopsis. BMC Genomics 15, 1–14. doi: 10.1186/1471-2164-15-431 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ding J.-H., Zhong X.-Y., Hagopian J. C., Cruz M. M., Ghosh G., Feramisco J., et al. (2006). Regulated cellular partitioning of SR protein-specific kinases in mamMalian cells. Mol. Biol. Cell 17, 876–885. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E05 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Dreyfuss G., Kim V. N., Kataoka N. (2002). Messenger-RNA-binding proteins and the messages they carry. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 3, 195–205. doi: 10.1038/nrm760 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Erkelenz S., Mueller W. F., Evans M. S., Busch A., Schöneweis K., Hertel K. J., et al. (2013). Position-dependent splicing activation and repression by SR and hnRNP proteins rely on common mechanisms. RNA 19, 96–102. doi: 10.1261/rna.037044.112 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Filichkin S. A., Priest H. D., Givan S. A., Shen R., Bryant D. W., Fox S. E., et al. (2010). Genome-wide mapping of alternative splicing in Arabidopsis thaliana. Genome Res. 20, 45–58. doi: 10.1101/gr.093302.109 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Gall J. G. (1956). Small granules in the amphibian oocyte nucleus and their relationship to RNA. J. Cell Biol. 2, 393–397. doi: 10.1083/jcb.2.4.393 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Geuens T., Bouhy D., Timmerman V. (2016). The hnRNP family: insights into their role in health and disease. Hum. Genet. 135, 851–867. doi: 10.1007/s00439-016-1683-5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ghosh G., Adams J. A. (2011). Phosphorylation mechanism and structure of serine-arginine protein kinases. FEBS J. 278, 587–597. doi: 10.1038/jid.2014.371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grosse S., Lu Y. Y., Coban I., Neumann B., Krebber H. (2021). Nuclear SR-protein mediated mRNA quality control is continued in cytoplasmic nonsense-mediated decay. RNA Biol. 18, 1390–1407. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2020.1851506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Haltenhof T., Kotte A., De Bortoli F., Schiefer S., Meinke S., Emmerichs A. K., et al. (2020). A conserved kinase-based body-temperature sensor globally controls alternative splicing and gene expression. Mol. Cell 78, 57–69. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2020.01.028 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann L., Drewe-Boß P., Wießner T., Wagner G., Geue S., Lee H.-C., et al. (2016). Alternative splicing substantially diversifies the transcriptome during early photomorphogenesis and correlates with the energy availability in arabidopsis. Plant Cell 28, 2715–2734. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00508 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hartmann L., Wießner T., Wachter A. (2018). Subcellular compartmentation of alternatively spliced transcripts defines SERINE/ARGININE-RICH PROTEIN30 expression. Plant Physiol. 176, 2886–2903. doi: 10.1104/pp.17.01260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hasimbegovic E., Schweiger V., Kastner N., Spannbauer A., Traxler D., Lukovic D., et al. (2021). Alternative splicing in cardiovascular disease—A survey of recent findings. Genes 12, 1457. doi: 10.2307/j.ctv1zckz9j.8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Howard J. M., Sanford J. R. (2015). The RNAissance family: SR proteins as multifaceted regulators of gene expression. Wiley Interdiscip. Rev. RNA 6, 93–110. doi: 10.1002/wrna.1260 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hyun Y., Richter R., Coupland G. (2017). Competence to flower: Age-controlled sensitivity to environmental cues. Plant Physiol. 173, 36–46. doi: 10.1104/pp.16.01523 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ishizawa M., Hashimoto K., Ohtani M., Sano R., Kurihara Y., Kusano H., et al. (2019). Inhibition of pre-mRNA splicing promotes root hair development in arabidopsis thaliana . Plant Cell Physiol. 60, 1974–1985. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcz150 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Isshiki M., Tsumoto A., Shimamoto K. (2006). The serine/arginine-rich protein family in rice plays important roles in constitutive and alternative splicing of pre-mRNA. Plant Cell 18, 146–158. doi: 10.1105/tpc.105.037069 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jang S., Cook N. J., Pye V. E., Bedwell G. J., Dudek A. M., Singh P. K., et al. (2019). Differential role for phosphorylation in alternative polyadenylation function versus nuclear import of SR-like protein CPSF6. Nucleic Acids Res. 47, 4663–4683. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkz206 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jeong S. (2017). SR proteins: Binders, regulators, and connectors of RNA. Mol. Cells 40, 1–9. doi: 10.14348/molcells.2017.2319 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jia R., Ajiro M., Yu L., McCoy P., Zheng Z. M. (2019). Oncogenic splicing factor SRSF3 regulates ILF3 alternative splicing to promote cancer cell proliferation and transformation. Rna 25, 630–644. doi: 10.1261/rna.068619.118 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jiang W., Chen L. (2021). Alternative splicing: Human disease and quantitative analysis from high-throughput sequencing. Comput. Struct. Biotechnol. J. 19, 183–195. doi: 10.1016/j.csbj.2020.12.009 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S., Ahn J. H. (2021). Regulation of flowering time by ambient temperature: repressing the repressors and activating the activators. New Phytol. 230, 938–942. doi: 10.1111/nph.17217 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jin S., Kim S. Y., Susila H., Nasim Z., Youn G., Ahn J. H. (2022). FLOWERING LOCUS M isoforms differentially affect the subcellular localization and stability of SHORT VEGETATIVE PHASE to regulate temperature-responsive flowering in Arabidopsis. Mol. Plant 15, 1696–1709. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2022.08.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jung J. H., Lee H. J., Ryu J. Y., Park C. M. (2016). SPL3/4/5 integrate developmental aging and photoperiodic signals into the FT-FD module in arabidopsis flowering. Mol. Plant 9, 1647–1659. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2016.10.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kędzierska H., Piekiełko-Witkowska A. (2017). Splicing factors of SR and hnRNP families as regulators of apoptosis in cancer. Cancer Lett. 396, 53–65. doi: 10.1016/j.canlet.2017.03.013 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kaida D., Berg M. G., Younis I., Kasim M., Singh L. N., Wan L., et al. (2010). U1 snRNP protects pre-mRNAs from premature cleavage and polyadenylation. Nature 468, 664–668. doi: 10.1038/nature09479 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang M. J., Jin H. S., Noh Y. S., Noh B. (2015). Repression of flowering under a noninductive photoperiod by the HDA9-AGL19-FT module in Arabidopsis. New Phytol. 206, 281–294. doi: 10.1111/nph.13161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kang W. H., Park Y. H., Park H. M. (2010). The LAMMER kinase homolog, Lkh1, regulates tup transcriptional repressors through phosphorylation in Schizosaccharomyces pombe. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 13797–13806. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M110.113555 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kanno T., Venhuizen P., Wen T. N., Lin W. D., Chiou P., Kalyna M., et al. (2018). PRP4KA, a putative spliceosomal protein kinase, is important for alternative splicing and development in arabidopsis Thaliana. Genetics 210, 1267–1285. doi: 10.1534/genetics.118.301515 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Keshwani M. M., Aubol B. E., Fattet L., Ma C. T., Qiu J., Jennings P. A., et al. (2015). Conserved proline-directed phosphorylation regulates SR protein conformation and splicing function. Biochem. J. 466, 311–322. doi: 10.1042/BJ20141373 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kim E., Ilagan J. O., Liang Y., Daubner G. M., Lee S. C. W., Ramakrishnan A., et al. (2015). SRSF2 mutations contribute to myelodysplasia by mutant-specific effects on exon recognition. Cancer Cell 27, 617–630. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2015.04.006 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kondo Y., Oubridge C., van Roon A. M. M., Nagai K. (2015). Crystal structure of human U1 snRNP, a small nuclear ribonucleoprotein particle, reveals the mechanism of 5’ splice site recognition. Elife 4, 1–19. doi: 10.7554/eLife.04986 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Koutroumani M., Papadopoulos G. E., Vlassi M., Nikolakaki E., Giannakouros T. (2017). Evidence for disulfide bonds in SR Protein Kinase 1 (SRPK1) that are required for activity and nuclear localization. PloS One 12, 1–21. doi: 10.1371/journal.pone.0171328 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kulkarni P., Jolly M. K., Jia D., Mooney S. M., Bhargava A., Kagohara L. T., et al. (2017). Phosphorylation-induced conformational dynamics in an intrinsically disordered protein and potential role in phenotypic heterogeneity. Proc. Natl. Acad. Sci. U. S. A. 114, E2644–E2653. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1700082114 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kwon C., Chung I. K. (2004). Interaction of an arabidopsis RNA-binding protein with plant single-stranded telomeric DNA modulates telomerase activity. J. Biol. Chem. 279, 12812–12818. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M312011200 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lacadie S. A., Rosbash M. (2005). Cotranscriptional spliceosome assembly dynamics and the role of U1 snRNA:5′ss base pairing in yeast. Mol. Cell 19, 65–75. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.05.006 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lai M. C., Lin R. I., Huang S. Y., Tsai C. W., Tarn W. Y. (2000). A human importin-β family protein, transportin-SR2, interacts with the phosphorylated RS domain of SR proteins. J. Biol. Chem. 275, 7950–7957. doi: 10.1074/jbc.275.11.7950 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lazar G., Goodman H. M. (2000). The Arabidopsis splicing factor SR1 is regulated by alternative splicing. Plant Mol. Biol. 42, 571–581. doi: 10.1023/A:1006394207479 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K. C., Chung K. S., Lee H. T., Park J. H., Lee J. H., Kim J. K. (2020. b). Role of Arabidopsis Splicing factor SF1 in Temperature-Responsive Alternative Splicing of FLM pre-mRNA. Front. Plant Sci. 11. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2020.596354 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee K., Du C., Horn M., Rabinow L. (1996). Activity and autophosphorylation of LAMMER protein kinases. J. Biol. Chem. 271, 27299–27303. doi: 10.1074/jbc.271.44.27299 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee Y. W., Kim W. T. (2010). Tobacco GTBP1, a homolog of human heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein, protects telomeres from aberrant homologous recombination. Plant Cell 22, 2781–2795. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.076778 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee J. H., Ryu H.-S., Chung K. S., Posé D., Kim S., Schmid M., et al. (2020. a). Regulation of temperature-responsive flowering by MADS-box transcription factor repressors. Science 342, 628–633. doi: 10.5040/9780755621101.0007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee G., Zheng Y., Cho S., Jang C., England C., Dempsey J. M., et al. (2018). Post-transcriptional regulation of de novo lipogenesis by mTORC1-S6K1-SRPK2 signaling. Cell 171, 1545–1558. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2017.10.037 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li J., Li G., Qi Y., Lu Y., Wang H., Shi K., et al. (2021. a). SRSF5 regulates alternative splicing of DMTF1 pre-mRNA through modulating SF1 binding. RNA Biol. 18, 318–336. doi: 10.1080/15476286.2021.1947644 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li H., Liu J. (2010). Identification of heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein K as a transactivator for human low density lipoprotein receptor gene transcription. J. Biol. Chem. 285, 17789–17797. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M109.082057 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Z., Tang J., Bassham D. C., Howell S. H. (2021. c). Daily temperature cycles promote alternative splicing of RNAs encoding SR45a, a splicing regulator in maize. Plant Physiol. 186, 1318–1335. doi: 10.1093/PLPHYS/KIAB110 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Li Q., Zeng C., Liu H., Yung K. W. Y., Chen C., Xie Q., et al. (2021. b). Protein-protein interaction inhibitor of SRPKs alters the splicing isoforms of VEGF and inhibits angiogenesis. iScience 24, 102423. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2021.102423 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin J., Shi J., Zhang Z., Zhong B., Zhu Z. (2022). Plant AFC2 kinase desensitizes thermomorphogenesis through modulation of alternative splicing. iScience 25, 104051. doi: 10.1016/j.isci.2022.104051 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lin B. Y., Shih C. J., Hsieh H. Y., Chen H. C., Tu S. L. (2020). Phytochrome coordinates with a hnRNP to regulate alternative splicing via an exonic splicing silencer. Plant Physiol. 182, 243–254. doi: 10.1104/pp.19.00289 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ling Y., Mahfouz M. M., Zhou S. (2021). Pre-mRNA alternative splicing as a modulator for heat stress response in plants. Trends Plant Sci. 26, 1153–1170. doi: 10.1016/j.tplants.2021.07.008 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Link S., Grund S. E., Diederichs S. (2016). Alternative splicing affects the subcellular localization of Drosha. Nucleic Acids Res. 44, 5330–5343. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkw400 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Chen S., Liu M., Chen Y., Fan W., Lee S., et al. (2022). Full-Length Transcriptome Sequencing Reveals Alternative Splicing and lncRNA Regulation during Nodule Development in Glycine max. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 23, 7371. doi: 10.3390/ijms23137371 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Liu J., Kong X., Zhang M., Yang X., Xu X. (2019). RNA binding protein 24 deletion disrupts global alternative splicing and causes dilated cardiomyopathy. Protein Cell 10, 405–416. doi: 10.1007/s13238-018-0578-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Low Y. H., Asi Y., Foti S. C., Lashley T. (2021). Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins: implications in neurological diseases. Mol. Neurobiol. 58, 631–646. doi: 10.1007/s12035-020-02137-4 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ltzelberger M., Käufer N. F. (2012). The prp4 kinase: its substrates, function and regulation in pre-mRNA splicing. Protein Phosphorylation Hum. Heal 6, 195–216. doi: 10.5772/48270 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lv Y., Zhang W., Zhao J., Sun B., Qi Y., Ji H., et al. (2021). SRSF1 inhibits autophagy through regulating Bcl-x splicing and interacting with PIK3C3 in lung cancer. Signal Transduction Targeting Ther. 6, 108. doi: 10.1038/s41392-021-00495-6 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Manley J. L., Krainer A. R. (2010). A rational and consistent nomenclature for serine/arginine-rich protein splicing factors (SR proteins). Genes Dev. 24, 1073–1074. doi: 10.1105/tpc.110.078352 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marondedze C., Groen A. J., Thomas L., Lilley K. S., Gehring C. (2016). A Quantitative Phosphoproteome Analysis of cGMP-Dependent Cellular Responses in Arabidopsis thaliana. Mol. Plant 9, 621–623. doi: 10.1016/j.molp.2015.11.007 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Marquez Y., Brown J. W. S., Simpson C., Barta A., Kalyna M. (2012). Transcriptome survey reveals increased complexity of the alternative splicing landscape in Arabidopsis. Genome Res. 22, 1184–1195. doi: 10.1101/gr.134106.111 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Matlin A. J., Clark F., Smith C. W. J. (2005). Understanding alternative splicing: Towards a cellular code. Nat. Rev. Mol. Cell Biol. 6, 386–398. doi: 10.1038/nrm1645 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Maule G., Casini A., Montagna C., Ramalho A. S., De Boeck K., Debyser Z., et al. (2019). Allele specific repair of splicing mutations in cystic fibrosis through AsCas12a genome editing. Nat. Commun. 10, 3556. doi: 10.1038/s41467-019-11454-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Mehta D., Ghahremani M., Pérez-Fernández M., Tan M., Schläpfer P., Plaxton W. C., et al. (2021). Phosphate and phosphite have a differential impact on the proteome and phosphoproteome of Arabidopsis suspension cell cultures. Plant J. 105, 924–941. doi: 10.1111/tpj.15078 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Molitor A. M., Latrasse D., Zytnicki M., Andrey P., Houba-Hérin N., Hachet M., et al. (2016). The arabidopsis hnRNP-Q protein LIF2 and the PRC1 subunit LHP1 function in concert to regulate the transcription of stress-responsive genes. Plant Cell 28, 2197–2211. doi: 10.1105/tpc.16.00244 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Müller-McNicoll M., Botti V., de Jesus Domingues A. M., Brandl H., Schwich O. D., Steiner M. C., et al. (2016). SR proteins are NXF1 adaptors that link alternative RNA processing to mRNA export. Genes Dev. 30, 553–566. doi: 10.1101/gad.276477.115 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nakamichi N. (2015). Adaptation to the local environment by modifications of the photoperiod response in crops. Plant Cell Physiol. 56, 594–604. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcu181 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ngo J. C. K., Chakrabarti S., Ding J. H., Velazquez-Dones A., Nolen B., Aubol B. E., et al. (2005). Interplay between SRPK and Clk/Sty kinases in phosphorylation of the splicing factor ASF/SF2 is regulated by a docking motif in ASF/SF2. Mol. Cell 20, 77–89. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2005.08.025 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Nishanth M. J., Jha S. (2023). Genome-wide landscape of RNA-binding protein (RBP) networks as potential molecular regulators of psychiatric co-morbidities: a computational analysis. Egypt. J. Med. Hum. Genet. 24, 2. doi: 10.1186/s43042-022-00382-x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park H. Y., Lee K. C., Jang Y. H., Kim S. K., Thu M. P., Lee J. H., et al. (2017). The Arabidopsis splicing factors, AtU2AF65, AtU2AF35, and AtSF1 shuttle between nuclei and cytoplasms. Plant Cell Rep. 36, 1113–1123. doi: 10.1007/s00299-017-2142-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Park Y. J., Lee J. H., Kim J. Y., Park C. M. (2019). Alternative RNA splicing expands the developmental plasticity of flowering transition. Front. Plant Sci. 10. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.00606 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Paronetto M. P., Passacantilli I., Sette C. (2016). Alternative splicing and cell survival: From tissue homeostasis to disease. Cell Death Differ. 23, 1919–1929. doi: 10.1038/cdd.2016.91 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Petrillo E., Godoy Herz M. A., Fuchs A., Reifer D., Fuller J., Yanovsky M. J., et al. (2014). A chloroplast retrograde signal regulates nuclear alternative splicing. Science 344, 427–430. doi: 10.1126/science.1250322 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Plocinik R. M., Li S., Liu T., Hailey K. L., Whitehouse J., Ma C. T., et al. (2011). Regulating SR protein phosphorylation through regions outside the kinase domain of SRPK1. J. Mol. Biol. 410, 131–145. doi: 10.1016/j.jmb.2011.04.077 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rahman M. A., Azuma Y., Nasrin F., Takeda J. I., Nazim M., Bin Ahsan K., et al. (2015). SRSF1 and hnRNP H antagonistically regulate splicing of COLQ exon 16 in a congenital myasthenic syndrome. Sci. Rep. 5, 1–13. doi: 10.1038/srep13208 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rauch J., O’Neill E., Mack B., Matthias C., Munz M., Kolch W., et al. (2010). Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoprotein H blocks MST2-mediated apoptosis in cancer cells by regulating a-raf transcription. Cancer Res. 70, 1679–1688. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-09-2740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rausin G., Tillemans V., Stankovic N., Hanikenne M., Motte P. (2010). Dynamic nucleocytoplasmic shuttling of an arabidopsis SR splicing factor: Role of the RNA-binding domains. Plant Physiol. 153, 273–284. doi: 10.1104/pp.110.154740 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rodriguez Gallo M. C., Li Q., Devang M., Uhrig R. G. (2022). Genome-scale analysis of Arabidopsis splicing-related protein kinase families reveals roles in abiotic stress adaptation. BMC Plant Biol. 22, 496. doi: 10.1186/s12870-022-03870-9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Saha K., Ghosh G. (2022). Cooperative engagement and subsequent selective displacement of SR proteins define the pre-mRNA 3D structural scaffold for early spliceosome assembly. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, 8262–8278. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkac636 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Samarina O. P., Krichevskaya A. A., Georgiev G. P. (1966). Nuclear ribonucleoprotein particles containing messenger ribonucleic acid. Nature 210, 1319–1322. doi: 10.1038/2101319a0 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Schneider M., Hsiao H. H., Will C. L., Giet R., Urlaub H., Lührmann R. (2010). Human PRP4 kinase is required for stable tri-snRNP association during spliceosomal B complex formation. Nat. Struct. Mol. Biol. 17, 216–221. doi: 10.1038/nsmb.1718 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Seaton D. D., Smith R. W., Song Y. H., MacGregor D. R., Stewart K., Steel G., et al. (2015). Linked circadian outputs control elongation growth and flowering in response to photoperiod and temperature. Mol. Syst. Biol. 11, 776. doi: 10.15252/msb.20145766 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Shishkin S. S., Kovalev L. I., Pashintseva N. V., Kovaleva M. A., Lisitskaya K. (2019). Heterogeneous nuclear ribonucleoproteins involved in the functioning of telomeres in Malignant cells. Int. J. Mol. Sci. 20, 745. doi: 10.3390/ijms20030745 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Sigala I., Koutroumani M., Koukiali A., Giannakouros T., Nikolakaki E. (2021). Nuclear translocation of SRPKs is associated with 5-FU and cisplatin sensitivity in heLa and T24 cells. Cells 10, 1–22. doi: 10.3390/cells10040759 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Singh R., Gupta S. C., Peng W. X., Zhou N., Pochampally R., Atfi A., et al. (2016). Regulation of alternative splicing of Bcl-x by BC200 contributes to breast cancer pathogenesis. Cell Death Dis. 7, 1–9. doi: 10.1038/cddis.2016.168 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stankovic N., Schloesser M., Joris M., Sauvage E., Hanikenne M., Motte P. (2016). Dynamic distribution and interaction of the arabidopsis SRSF1 subfamily splicing factors. Plant Physiol. 170, 1000–1013. doi: 10.1104/pp.15.01338 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Stevens M., Oltean S. (2019). Modulation of the apoptosis gene bcl-x function through alternative splicing. Front. Genet. 10. doi: 10.3389/fgene.2019.00804 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Streitner C., Köster T., Simpson C. G., Shaw P., Danisman S., Brown J. W. S., et al. (2012). An hnRNP-like RNA-binding protein affects alternative splicing by in vivo interaction with transcripts in Arabidopsis thaliana. Nucleic Acids Res. 40, 11240–11255. doi: 10.1093/nar/gks873 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanabe N., Yoshimura K., Kimura A., Yabuta Y., Shigeoka S. (2007). Differential expression of alternatively spliced mRNAs of Arabidopsis SR protein homologs, atSR30 and atSR45a, in response to environmental stress. Plant Cell Physiol. 48, 1036–1049. doi: 10.1093/pcp/pcm069 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tange T., Damgaard C. K., Guth S., Valcárcel J., Kjems J. (2001). The hnRNP A1 protein regulates HIV-1 tat splicing via a novel intron silencer element. EMBO J. 20, 5748–5758. doi: 10.1093/emboj/20.20.5748 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Thatcher S. R., Zhou W., Leonard A., Wang B. B., Beatty M., Zastrow-Hayes G., et al. (2014). Genome-wide analysis of alternative splicing in Zea mays: Landscape and genetic regulation. Plant Cell 26, 3472–3487. doi: 10.1105/tpc.114.130773 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tillemans V., Leponce I., Rausin G., Dispa L., Motte P. (2006). Insights into nuclear organization in plants as revealed by the dynamic distribution of Arabidopsis SR splicing factors. Plant Cell 18, 3218–3234. doi: 10.1105/tpc.106.044529 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tognacca R. S., Servi L., Hernando C. E., Saura-Sanchez M., Yanovsky M. J., Petrillo E., et al. (2019). Alternative splicing regulation during light-induced germination of arabidopsis thaliana seeds. Front. Plant Sci. 10. doi: 10.3389/fpls.2019.01076 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Varjosalo M., Keskitalo S., VanDrogen A., Nurkkala H., Vichalkovski A., Aebersold R., et al. (2013). The protein interaction landscape of the human CMGC kinase group. Cell Rep. 3, 1306–1320. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2013.03.027 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang Z., Rolish M. E., Yeo G., Tung V., Mawson M., Burge C. B. (2004). Systematic identification and analysis of exonic splicing silencers. Cell 119, 831–845. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2004.11.010 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang T., Wang X., Wang H., Yu C., Xiao C., Zhao Y., et al. (2023). Arabidopsis SRPKII family proteins regulate flowering via phosphorylation of SR proteins and effects on gene expression and alternative splicing. New Phytol. 238, 1889–1907. doi: 10.1111/nph.18895 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wang J., Wu H. F., Shen W., Xu D. Y., Ruan T. Y., Tao G. Q., et al. (2016). SRPK2 promotes the growth and migration of the colon cancer cells. Gene 586, 41–47. doi: 10.1016/j.gene.2016.03.051 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Willems P., Horne A., Van Parys T., Goormachtig S., De Smet I., Botzki A., et al. (2019). The Plant PTM Viewer, a central resource for exploring plant protein modifications. Plant J. 99, 752–762. doi: 10.1111/tpj.14345 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wu Z., Zhu D., Lin X., Miao J., Gu L., Deng X., et al. (2016). RNA binding proteins RZ-1B and RZ-1C play critical roles in regulating pre-mRNA splicing and gene expression during development in arabidopsis. Plant Cell 28, 55–73. doi: 10.1105/tpc.15.00949 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xiang S., Gapsys V., Kim H. Y., Bessonov S., Hsiao H. H., Möhlmann S., et al. (2013). Phosphorylation drives a dynamic switch in serine/arginine-rich proteins. Structure 21, 2162–2174. doi: 10.1016/j.str.2013.09.014 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xu Y., Wu W., Han Q., Wang Y., Li C., Zhang P., et al. (2019). Post-translational modification control of RNA-binding protein hnRNPK function. Open Biol. 9, 180239. doi: 10.1098/rsob.180239 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Xue H., Zhang Q., Wang P., Cao B., Jia C., Cheng B., et al. (2022). qPTMplants: an integrative database of quantitative post-translational modifications in plants. Nucleic Acids Res. 50, D1491–D1499. doi: 10.1093/nar/gkab945 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yan Q., Xia X., Sun Z., Fang Y. (2017). Depletion of Arabidopsis SC35 and SC35-like serine/arginine-rich proteins affects the transcription and splicing of a subset of genes. PloS Genet. 13, 1–29. doi: 10.1371/journal.pgen.1006663 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yeap W. C., Namasivayam P., Ooi T. E. K., Appleton D. R., Kulaveerasingam H., Ho C. L. (2019). EgRBP42 from oil palm enhances adaptation to stress in Arabidopsis through regulation of nucleocytoplasmic transport of stress-responsive mRNAs. Plant Cell Environ. 42, 1657–1673. doi: 10.1111/pce.13503 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Yun B., Farkas R., Lee R., Rabinow L. (1994). The Doa locus encodes a member of a new protein kinase family and is essential for eye and embryonic development in Drosophila melanogaster. Genes Dev. 8, 1160–1173. doi: 10.1101/gad.8.10.1160 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhang L., Abendroth F., Vázquez O. (2022). A chemical biology perspective to therapeutic regulation of RNA splicing in spinal muscular atrophy (SMA). ACS Chem. Biol. 17, 1293–1307. doi: 10.1021/acschembio.2c00161 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z., Fu X. D. (2013). Regulation of splicing by SR proteins and SR protein-specific kinases. Chromosoma 122, 191–207. doi: 10.1007/s00412-013-0407-z [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Zhou Z., Qiu J., Liu W., Zhou Y., Plocinik R. M., Li H., et al. (2012). The akt-SRPK-SR axis constitutes a major pathway in transducing EGF signaling to regulate alternative splicing in the nucleus. Mol. Cell 47, 422–433. doi: 10.1016/j.molcel.2012.05.014 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]