Abstract

HIV remains a public health concern in the United States. Although pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) can be expected to reduce HIV incidence, its uptake, adherence, and persistence remain limited, particularly among highest priority groups such as men who have sex with men and transwomen (MSMTW). Using a socioecological framework, we conducted a scoping review to examine PrEP-related stigma to inform future research, policy, and programmatic planning. Using the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews, we conducted database searches from August 2018 to April 2020 for articles addressing PrEP stigma. Studies were independently screened and coded by three authors, resulting in thematic categorization of several types of PrEP stigma on four socioecological levels. Of 557 references, a final sample of 23 studies was coded, 61% qualitative, and 87% focusing exclusively on MSMTW. Most instances of PrEP-related stigma occurred on the interpersonal level and included associations of PrEP with risk promotion, HIV-related stigma, and promiscuity. Other frequent themes across socioecological levels included provider distrust and discrimination, government and pharmaceutical industry distrust, internalized homonegativity, PrEP efficacy distrust, and anticipated homonegativity. Notably, PrEP was also framed positively as having physical and psychological benefits, and assuming responsibility for protecting one’s community via PrEP awareness-raising. PrEP-related stigma persists, demanding interventions to modify its impact. Leveraging PrEP-positive discourses to challenge PrEP stigma is an emerging avenue, alongside efforts to increase provider willingness to promote PrEP routinely by reducing provider bias, aligning with the national strategy to End the HIV Epidemic.

Keywords: PrEP, HIV, Stigma, MSM, Transwomen

Introduction

HIV remains a major public health priority in the United States (U.S.), where 37,968 new HIV cases have recently been reported [1]. Reductions in HIV incidence plateaued in 2013 and have remained stable overall since, primarily because multiple barriers to HIV prevention and treatment for high-risk groups remain [1–5]. Notably, incidence has continued to increase in some groups, particularly among persons aged 25–34, and Black and Latinx men and transwomen who have sex with men (MSMTW) [6]. As such, the HIV epidemic continues to disproportionately affect the U.S. racial minority MSMTW population [7]. With a 50% lifetime risk of HIV and an incidence 23 times that of White heterosexual men [8], Black MSM are at staggering risk of acquiring HIV. The U.S. national HIV strategy and End the HIV Epidemic initiatives both recognize these disparities and aim to address them to reduce HIV incidence [7, 9].

Expansion of antiretroviral therapy use, which prevents forward transmission of HIV once viral suppression is reached and sustained, can be expected to contribute to further incidence reductions [10], if rates of viral suppression increase uniformly across various priority populations (e.g., MSM, transgender individuals). In addition, Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis (PrEP), currently approved in the U.S. as a once-daily fixed dose of emtricitabine and tenofovir, is 99% effective in preventing HIV acquisition when taken as prescribed [11]. Yet, uptake, adherence and persistence of PrEP have been limited [12–14], particularly in the populations at highest risk for HIV acquisition, such as young MSMTW of color [15–18].

Stigma affects quality of life and healthcare engagement for MSMTW, especially for MSMTW of color, and contributes to poorer HIV-related outcomes for HIV-positive individuals [19]. High levels of stigma also contribute to the increased HIV vulnerability of MSMTW of color given that they experience intersecting stigmas of race, ethnicity, sexuality, HIV, and, most recently, PrEP-related stigma [20]. Evidence shows that stigma occurring on multiple levels affects HIV prevention methods such as PrEP by impeding awareness, uptake, adherence and persistence [21]. Furthermore, discrimination against members of the Lesbian, Gay, Bisexual, Trans, and Queer (LGBTQ) community impede healthcare and HIV prevention engagement [22, 23]. Among transgender individuals, gender identity disclosure is a significant barrier, and often tied to fear of discrimination and stigma [23, 24]. For Black MSM and transwomen, individual and systemic racism significantly impact HIV healthcare engagement and outcomes [25–27].

Further, there is considerable PrEP-related stigma from within the MSMTW community, often shaping motivations for PrEP uptake [28–31]. For example, shaming of PrEP users [28] through assumptions of sexual promiscuity [32, 33] and risk taking [33–35], as well as fears of being perceived as HIV-positive [36], have posed major barriers to its use. Notably, another group that is at increased risk for poor HIV-related outcomes, primarily driven by stigma, are transgender men (transmen) [37]. However, the research to date on transmen and PrEP evidences a considerable gap, demanding significant future efforts in this direction. It therefore follows from the above that finding mechanisms to reduce PrEP-associated stigma, across diverse priority groups, is essential [20]. A first step would be to rigorously document the types and characteristics of the stigma that surround PrEP use, in order to directly target them.

There is an increasing body of literature addressing stigma related to PrEP use with varying foci (e.g., it being a primary or exploratory study outcome), addressing a wide range of topics (e.g., disclosure of use, access, relationship implications), and using different measures of assessment (e.g., in-depth interviews, focus groups or surveys). Yet, consensus within this literature has not been reached in terms of how to comprehensively frame and evaluate various types of stigma, with the goal of informing interventions to reduce stigma-related barriers impacting PrEP utilization [33, 38–45].

Prior studies have framed stigma dimensions based on how these are manifested and/or experienced by their targets, categorizing stigma into experienced, perceived, anticipated, and internalized stigma [46]. Experienced stigma is often conflated or combined with enacted stigma, and can include acts of discrimination and shaming, or refer to lived experiences of stereotypes, prejudice, rejection, or violence [31, 47]. Perceived stigma reflects a person’s perception of the sociocultural climate including perceptions of homonegativity, while anticipated stigma refers to the expectation of rejection [31, 48]. Additionally, there is also conflation of perceived and anticipated stigma. For example, Brooks et al. [31] included perceived stigma in their anticipated stigma framing, whereas other authors provide a clearer distinction between the two [33, 49]. Internalized stigma refers to negative self-evaluation as a reflection of ubiquitous stigma in one’s environment, which an individual has attributed to themselves, leading to a negative self-view or self-appraisal [46]. Recently an additional stigma-related dimension has emerged, namely challenging stigma, which explicitly references acts of stigma mitigation and is based on resilience and coping [38, 50–54]. In addition to types of stigma that act on individual, interpersonal, community, and institutional levels, structural stigma refers to the climate of laws, policies and processes that create and/or perpetuate stigma [55].

Importantly, there are different forms of stigma an individual may experience that are attached to different attributes, such as socioeconomic status, mental health conditions, and often being of a minority status. Racial and ethnic minority MSMTW may experience stigma related to their sexual minority identity, race, and HIV status, whether actual or presumed [19]—a phenomenon often referred to as intersectional stigma, when multiple stigmas combine in a multiplicative, rather than additive, manner [56]. Intersectionality focuses on the experience of people from multiply marginalized groups and acknowledges that these multiple social identities produce disparate health outcomes via a confluence of negative social forces such as racism, sexism, transphobia, homophobia and HIV stigma [57].

An organizing framework that may readily lead to understanding the types of interventions needed to combat PrEP-related stigma is the socioecological model [58, 59], which has been widely used across fields, including within HIV research [60]. This approach accounts for the layers of influence that impact health behavior, with the most proximal one being the individual level (one’s own cognitions, affect and behavior), and the most distal being the structural level (laws and policies at a national level). Several published papers on stigma related to PrEP have applied the socioecological model to demonstrate how PrEP stigma operates on various levels of this system [38, 55, 61]. The current scoping review examines the occurrence of PrEP-related stigma on four levels of the socioecological model. At the individual level, for example, internalized homonegativity may lead to increased vulnerability to HIV transmission [62, 63], potential distrust in PrEP efficacy, or side effect concerns that limit PrEP uptake among MSMTW [64]. At the interpersonal level, stigma manifests as shaming individuals with multiple sex partners [45, 65], or suspecting one to be HIV positive [5, 66]. At the community level, homonegativity or shaming from outside or within the LGBTQ community are manifestations of stigma [21, 29, 49, 67]. Recurring experiences of discrimination and unfair treatment by individual healthcare providers and clinic environments lead to medical distrust by patients faced with such negative endemic encounters [68]. Distrust in providers [21, 61], healthcare systems [14], or the government at large [61] have been operationalized in the literature as manifestations of institutional-level stigma and have been associated with negative health outcomes, including poor HIV-related health outcomes [68–71], and may impact PrEP use. Such systems of oppression are largely driven by policies that create and perpetuate discrimination against minority populations, and fueled by political forces that aim to further marginalize minority communities [72], especially in geographical areas of the U.S. that are documenting the highest HIV transmission rates currently [73]. Notably, little research exists to date on PrEP-related stigma on the structural level, such as policies and legislature that shapes PrEP uptake and persistence.

In order to garner a comprehensive perspective on PrEP-related stigma, we aimed to examine existing literature to date reporting on various types of stigma that may limit the impact of PrEP for HIV prevention via access, uptake, adherence, and persistence. Distilling the current state of research on PrEP-related stigma has the potential to suggest future research directions, as well as inform policy and programmatic planning, including where and what types of interventions may be needed to reduce PrEP-related stigma and its impact on PrEP utilization. This inquiry was guided by several research questions, as follows: (1) What are the types of stigma that may have emerged in relation to PrEP?; (2) On which levels of the socioecological planes does PrEP-related stigma manifest most frequently?; and (3) What are the implications for future research, intervention and policy that these findings can guide?

Methods

A scoping review format was chosen for this study given its advantages over a systematic review to describe broad themes and analyze current evidence characterizing stigma, as opposed to the effectiveness of a given intervention [74]. This was especially important given the expected heterogenous and qualitative nature of the evidence [74]. We used the PRISMA extension for scoping reviews checklist as a framework for this scoping review [75], and conducted a series of searches from August 2018 to April 2020 using the electronic databases of PubMed, Embase, ProQuest, and clinicaltrials.gov to identify articles discussing PrEP use and stigma among MSMTW and transmen, including conference proceedings, dissertations, and clinical trials. Our search strategy included a broad range of terms related to stigma such as “stigma”, “shame”, “prejudice”, “homophobia”, “distrust”, “discrimination”, and “racism” alongside synonyms for PrEP (e.g., biomedical prevention, HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis), and men who have sex with men (MSM) and transgender individuals. Our definition of MSMTW included individuals assigned male sex at birth (including cis and nonbinary men, and transwomen) who reported sex with partners who were also assigned male sex at birth (including cis and nonbinary men, and transwomen). The final Boolean query consisted of the stigma-related MeSH headings Social stigma, Shame, Social discrimination, Prejudice, Homophobia, and Racism, combined with title and abstract searches for Stigma, Shame, Discriminat*, Prejudice, Distrust, Homophobia, Homonegativity, Racism, Racial discrimination, Barrier, Attitude, and Accept. For PrEP, we used the MeSH term Pre-Exposure Prophylaxis, and the title and abstract searches Pre-exposure prophylaxis, Preexposure prophylaxis, HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis, HIV preexposure prophylaxis, PrEP, HIV PrEP, and Biomedical prevention. Finally, we combined these terms with the MeSH term Sexual and gender minorities, and the title and abstract terms MSM, Men who have sex with men, Transgender women, Gay, Bisexual, Queer, LGBT*, and transgender men.

Sample

We included studies that explicitly addressed a broad range of PrEP-related issues and stigma, from attitudes to actual use. Our inclusion criteria were (1) studies which included MSM and transgender individuals, (2) studies of stigma, discrimination or cultural beliefs about PrEP for HIV prevention, and (3) studies using quantitative, qualitative, or mixed methods. Exclusion criteria were (1) studies of ciswomen, individuals assigned male sex at birth who did not report sex with other males assigned sex at birth, or people with HIV, and (2) reviews, meta analyses, opinion pieces, or letters to the editor. Only studies reporting on primary data were included. Additionally, stigma is a cultural phenomenon with significant variation across cultures and nations [42, 56, 76, 77]. We therefore included only studies from North America because of our intention to provide guidelines for programming and intervention to reduce PrEP-related stigma within the U.S. Given the highly context-specific of PrEP-related attitudes and practices, other global regions would benefit from guidelines unique to their settings. Based on the inclusion criteria, articles in which PrEP-related stigma themes were not present were excluded during the full text review phase.

Coding

All studies were independently screened in both the abstract and full-text screening by two authors (ALR, EWW), and disagreements about study eligibility were resolved by a third author (LHW). For each included study, two authors (ALR, CLW) extracted the objectives, methods and study population (Table 1). We used a discourse analysis theoretical framework to identify the emerging discourses around PrEP use that shaped views on PrEP users/candidates (e.g., responsible, promiscuous, HIV-infected, etc.) or their reported interactions with other individuals and healthcare systems in the U.S. [78]. To abstract themes, we employed a similar process as undertaken in qualitative data analyses via grounded theory of establishing themes and codes in an iterative process between text and an evolving codebook [79]. We used a thematic analysis methodological approach to gradually develop and reconcile a codebook between two independent coders with conflict resolution by a third independent coder. Specifically, two authors, who had qualitative analysis training and experience (ALR, CLW), began developing the codebook by first reading through a set of five articles independently and coding portions indicative of PrEP-related stigma, after which they convened to compare findings. Guided by the socioecological model framework, the authors first classified the emerging themes on five levels of interest within the socioecological framework (e.g., individual, interpersonal, community, institutional and structural). However, no articles captured by our search reflected structural-level PrEP-specific stigma discourses from primary data analyses, therefore this level was not ultimately included in the current analyses. Initial themes under each level were established based on the authors’ preliminary knowledge of PrEP-related stigma discourses in the literature (e.g., promiscuity).

Table 1.

Study characteristics

| Studies | Year(s) data collection | Location | Methodology | N | Sample demographics |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mutchler et al. [65] | 2014 | Los Angeles, CA, US | Dyadic interviews | 48 | Mean age = 22.1 (19–28), 86% Black, 88% gay/bi, 12.5% ciswomen |

| Golub et al. [107] | 2013–2014 | New York, NY, US | Interviews | 160 | Mean age = 32.5 (N/A), 57% Black/Latino, 80% gay/bi, ciswomen N/A |

| Knight et al. [35] | N/A | Vancouver, Canada | Interviews | 50 | Mean age N/A (18–24), 48% non-White, 32% gay/bi, 2% transmen ciswomen N/A |

| Farhat et al. [83] | 2015 | New York, NY, US | Survey | 583 | Mean age = 44 (N/A), 75% Black, 6% Latinx, 9% gay/bi, 53% ciswomen |

| Philbin et al. [61] | 2013–2014 | New York, NY, US | Interviews | 31 | Mean age = 29 (N/A), race/ethnicity N/A, 100% gay/bi, ciswomen N/A |

| Lelutiu-Weinberger and Golub [5] | 2012–2014 | New York, NY, US | Survey, interviews | 491 | Mean age N/A, 56% Black/Latinx, 100% gay/bi, ciswomen N/A |

| Eaton et al. [84] | 2014 | Five US cities | Survey | 1274 | Mean age = 30 (N/A), race/ethnicity N/A, 76% gay/bi, 4% transwomen, ciswomen N/A |

| Eaton et al. [14] | 2015 | City in SE US | Survey | 264 | Mean age = 31 |

| Cahill et al. [67] | 2013 | Boston and Jackson | Focus groups | 35 | Boston: Mean age = 43 (N/A), 73% White non-Hispanic, 100% gay/bi, ciswomen N/A Jackson: Mean age = 23 (N/A), 95% Black, 100% gay/bi, transwomen 5%, ciswomen N/A |

| Hubach et al. [21] | 2016 | Southcentral US | Interviews | 20 | Mean age N/A (N/A), race/ethnicity N/A, 100% gay/bi, 100% cismen ciswomen N/A |

| Garcia and Harris [85] | N/A | San Antonio, Texas | Survey | 159 | Mean age N/A (21–30), 100% Latinx, 100% gay/bi, 100% cismen ciswomen N/A |

| Thomann et al. [29] | N/A | New York, NY, US | Focus groups | 24 | Mean age N/A (21–50), 100% Black/Latinx, 100% gay/bi, ciswomen N/A |

| Golub et al. [94] | 2015 | US | Survey | 692 | Mean age = 33 (N/A), 23% non-white 22% Latino, 100% MSM/TW, ciswomen N/A |

| Franks et al. [66] | N/A | Harlem | Focus groups, interviews | 37 | Mean age = 34 (N/A), 68% Black 8% Asian 2% Latinx, 100% MSM, ciswomen N/A |

| Grace et al. [80] | N/A | Toronto, Canada | Focus groups, interviews | 16 | Mean age = 38 (N/A), 69% White, 100% gay/bi, 100% cismen, ciswomen N/A |

| Mustanski et al. [33] | 2016 | Chicago, US | Survey | 620 | Mean age = 21 (N/A), 29% Black 33% Hispanic, 100% gay/bi/transwomen, ciswomen N/A |

| Grimm and Schwartz [81] | 2016–2017 | US | Interviews | 39 | Mean age = 35 (N/A), 69% White 19% Latinx, 100% gay/bi, ciswomen N/A |

| Pawson and Grov [82] | 2015–2016 | New York, NY, US | Focus groups | 32 | Mean age = 35 (N/A), race/ethnicity N/A, 100% gay/bi, ciswomen N/A |

| Jaiswal et al. [87] | 2014–2016 | New York, NY, US | Data from longitudinal cohort study | 492 | Mean age N/A (N/A; “young”), 26% Black 31% Latinx, 100% gay/bi, ciswomen N/A |

| Dubov et al. [34] | 2015 | US | Interviews | 43 | Mean age = 30 (N/A), race/ethnicity N/A, 100% gay/bi, ciswomen N/A |

| Refugio et al. [88] | 2016–2017 | San Francisco Bay area | Survey | 25 | Mean age = 22 (N/A), 40% Latinx, 32% Asian, 100% gay/bi, 100% cismen, ciswomen N/A |

| Walsh [45] | 2016 | Midwest, US | Survey | 476 | Mean age = 35, 21% Black, 100% gay/bi, ciswomen N/A |

| Brooks et al. [32] | 2017 | US | Interviews | 29 | Mean age = 30 (N/A), 100% Latinx, 100% gay/bi, ciswomen N/A |

After each set of independent coding, each segment of coded text was reviewed together by the two authors, and the codes were further refined to yield a draft codebook. Then the authors recoded the five articles according to the revised codebook, and coded another set of five articles. The process was repeated three times, after which the two authors coded the remainder of the articles based on the final codebook. The authors categorized codes reflective of a particular socioecological level on which stigma could be classified. A particular code (e.g., “risk promotion”) was marked once in each article where it appeared, even if quotes reflective of it were presented from several interview or focus group participants. Once all articles were coded, a third author (PS) conducted inter-rater reliability analyses and the last discrepancies were resolved by the two coders (ALR, CLW) who examined each instance and considered its classification. The inter-coder reliability was κ = 0.71, indicating adequate agreement.

Reflecting on Turan’s initial framework [46] and in an effort to provide granular information on stigma dimensions, our coding of stigma themes reflects the following logic. Our coding of perceived stigma was that of a general perception of one’s community’s opinions, whereas anticipated stigma assumes the expectation of negative reactions from other individuals. Perceived stigma in this approach generally operates at a higher level of the socioecological model, within the community or society at large, whereas anticipated stigma appears to operate on the interpersonal level. We further distinguished enacted stigma as arising from interpersonal interactions, such that one party is effectively the perpetrator of stigmatization. Defining dimensions of stigma at this level of granularity can promote clarity in future PrEP stigma research, particularly in the quest to reduce negative attitudes and misperceptions to promote widespread acceptance and adoption of PrEP.

Results

General Characteristics of Included Articles

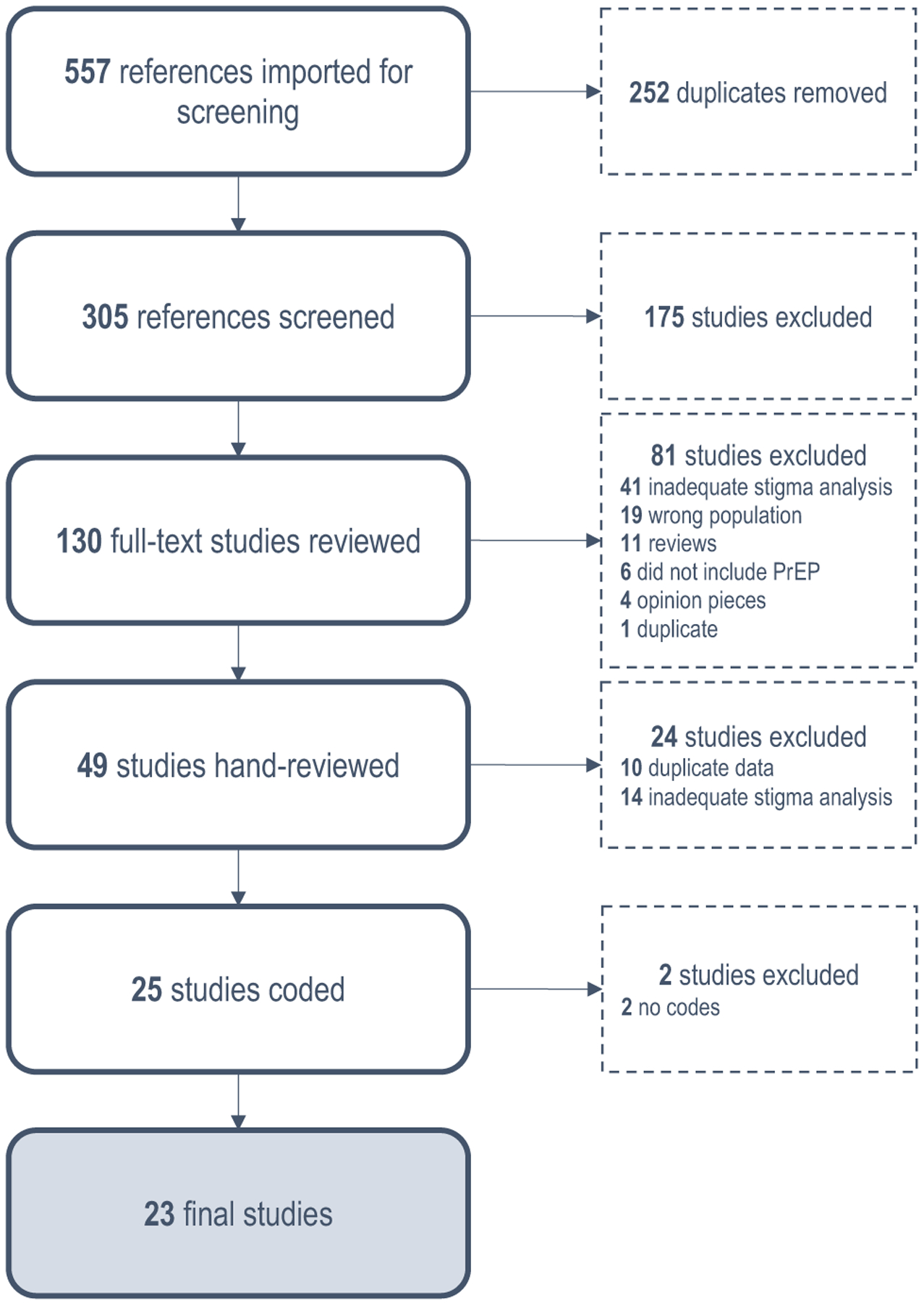

Our initial PubMed search yielded 557 references, resulting in 305 unique studies after 252 duplicates were removed (Fig. 1). Abstract screening excluded 175 references. Full-text review excluded an additional 81 references. An additional 24 articles were excluded during final hand review, 10 of which were papers published from the same data, and 14 of which were deemed to not have a sufficiently in-depth assessment of stigma to allow coding. This yielded a final sample of 25 coded studies. Two additional studies were removed after coding since both studies ultimately yielded no PrEP stigma-related codes (Table 1).

Fig. 1.

PRISMA diagram

Fourteen [5, 21, 29, 31, 34, 35, 49, 61, 65–67, 80–82] (61%) of the 23 coded studies used qualitative or mixed methods such as in-depth interviews or focus groups, and nine (39%) used a cross-sectional survey design [14, 33, 45, 83–88]. The majority (87%) focused mostly or exclusively on MSMTW; one study included men of all sexual orientations [35], one study did not restrict based on sex or gender [83], and one study did not report overall sample demographic information [14]. The earliest date of data collection among these articles was 2012, also coinciding with the year PrEP was US FDA-approved, demonstrating an early quest in the field for manifestations of stigma known to impede health behaviors.

Our gray literature search from Embase, ProQuest and clinicaltrials.gov resulted in six relevant results, including one clinical trial, one poster presentation, and four dissertations. None of these met our inclusion criteria and therefore were not coded.

Prevalence of PrEP Stigma by Socioecological Level

Most instances of identified PrEP-related stigma occurred on the interpersonal level, and included 12 main categories, each of which appeared with different frequency across articles (Table 2). Twelve articles [14, 29, 31, 33, 45, 49, 65, 80–83, 86] reflected discourses of PrEP-related promiscuity, primarily as reported by study participants interviewed or in focus groups, and reflected primarily attributions made by others (actual or potential sex partners, family members, co-workers, providers, or friends) about actual or hypothesized PrEP users. Examples of PrEP use being equated with promiscuity include: “It’s just giving people a free pass. That’s how they take PrEP. They take it as a free pass to go just willy-nilly and do whatever the hell it is they want to do.” [82, p. 1395].

Table 2.

PrEP-related stigma documented in scoping review sample by socioecological levels and thematic findings

| Stigma expression | Frequency | Examples |

|---|---|---|

| Individual level | ||

| Internalized homophobia | 4 |

|

| PrEP efficacy distrust | 4 |

|

| Internalized promiscuity | 2 |

|

| Positive health impact | 11 |

|

| Interpersonal level | ||

| Promiscuity | 12 |

|

| Risk promotion | ||

| Anticipating | 10 |

|

| Enacting | 10 |

|

| Experiencing | 6 |

|

| HIV-related stigma | ||

| Anticipating | 10 | |

| Experiencing | 4 | |

| Enacting | 2 |

|

| Negative relationship impact | 8 |

|

| Homophobia/other ing | 6 |

|

| General | 6 |

|

| Community level | ||

| Anticipated homophobia | 4 |

|

| Responsibility to educate peers | 7 |

|

| Institutional level | ||

| Provider distrust | 10 |

|

| Provider discrimination | 7 |

|

| Governmental/pharmaceutical distrust | 7 |

|

| Healthcare distrust | 5 |

|

The next three themes fell in the category of “risk promotion,” namely anticipating and experiencing situations in which PrEP use was framed as promoting sexual risk. Specifically, 10 articles [21, 31, 34, 49, 65, 66, 80–82, 85] reflected that participants, in considering or using PrEP, anticipated encountering discourses of risk promotion from others (e.g., “they’ll tell people as soon as you leave the table that you’re doing that ‘cause you wanna have numerous tricks or anonymous encounters… you’re only using PrEP to rationalize your true behavior.” [21, p. 321]). Further, 10 articles [14, 21, 29, 33–35, 61, 65, 81, 82] presented data on participants endorsing (or enacting) beliefs that PrEP is conducive of risk promotion (e.g., “these men recalled ‘people being slut shamed for using PrEP. My friends had negative thoughts and things to say about it.” [21, p. 321]). Lastly, six articles [21, 31, 34, 66, 80, 81] provided data from participants who had encountered others framing their PrEP use as promoting risk (e.g., “once I told them that I was on PrEP because they assumed that my whole lifestyle is changed…one of the regulars that I had previous to going on PrEP decided to stop doing me because he assumed that I would instantly become like a receptacle…for every gay plague known to man..” [80, p. 26]).

PrEP use in relation to HIV stigma appeared in 12 articles [5, 21, 29, 31, 34, 49, 61, 65, 66, 81, 85, 87]. The most common theme was anticipated HIV stigma (e.g., “‘People don’t like taking any medicine in front of people. Maybe they feel like a stigma would develop from what you are taking? People be nosy, like what’s that you taking?” [61, p. 287]). Other themes included having experienced HIV stigma (e.g., “I think one of my friends I had to tell exactly what it was because they saw the bottle and I think they looked up what it was for and they thought I had HIV because it was an HIV med.” [31, p. 6]), and enacted HIV stigma (e.g., “For me, if someone just said so-and-so’s using PrEP and I knew what PrEP was at that time, I would question what is their HIV status” [66, p. 1145]).

Another interpersonal-level theme was related to the negative impact PrEP had on romantic relationships, which appeared in five articles [29, 31, 34, 66, 80]. Expressly, once one of the partners considered or began taking PrEP, the other partner either confronted them for not trusting their monogamy or for wanting to have sex with other people:

I am recently single due to my partner not understanding why I take PrEP. He felt PrEP was interfering with the possibility of a commitment. He asked me to stop taking Truvada as a show of good faith for a relationship, but I knew his part was fickle at best.

[34, p. 1836].

Six articles [29, 34, 35, 61, 82, 85] reported associations of PrEP with homonegativity, specifically related to gay men being promiscuous (e.g., “I’ve heard that it’s only for gay men… someone today… told me if he was on PrEP he’d be a whore, like that is his get out of jail free card.… It’s only for gay men, it’s only for whores.” [29, p. 776]). Four articles [31, 34, 80, 88] reported general stigmatizing PrEP-related references (e.g., “Instead of continuing these risky behaviours and using HIV medication, maybe people should just stop the behaviour, right?.” [35, p. 7]).

The next level on which PrEP-related stigma was frequently manifested was at the institutional level, under five main coded categories, as follows. Ten articles [5, 21, 29, 31, 61, 67, 81, 85, 87, 88] revealed PrEP themes related to provider distrust, such as Black and Latinx MSMTW reporting having to talk to their doctor about sex being a barrier to seeking PrEP [5], followed by seven articles [21, 29, 31, 67, 80, 81, 88] reporting provider discrimination (e.g., “My previous doctor, who was a man, just told me to have sex with women.” [67, p. 14]). Five articles [14, 29, 61, 65, 85] revealed themes of distrust in the government and/or pharmaceutical companies (e.g., “A more common assumption was that pharmaceutical companies were encouraging the use of PrEP while withholding a cure for HIV in order to generate income from medication sales.” [65, p. 494]). Finally, for this level, five articles [14, 29, 61, 65, 85] contained themes of general healthcare distrust in promoting PrEP (e.g., “Among [Black men and transgender women who have sex with men], believing that the CDC cannot be trusted in their messaging regarding PrEP was associated with a lower interest in using PrEP [14]).

PrEP-related stigma at the individual level was reported in 17 papers, where three main PrEP-related categories emerged: four articles [5, 34, 61, 84] revealed themes of internalized homonegativity in association with PrEP use [84], four articles [5, 29, 45, 67] indicated distrust in PrEP efficacy and two articles reporting instances of internalized promiscuity in relation to PrEP use (e.g., “Like you are not getting the big one, but you are also opening yourself up to syphilis, gonorrhea, all of these. I feel like it would lead me to be more promiscuous.” [21, p. 324]).

Only one main PrEP stigma-related category emerged related to community level stigma, namely four articles reflected general community associations of PrEP use with anticipated homophobic (“homonegative”) reactions from others (e.g., “A small percentage of participants (6.3%, n = 10) were concerned that PrEP use would be associated with negative beliefs about gay men’s sexuality and would intensify negative beliefs about the gay community” [49]).

Of note, within many of the studies, authors noted recurring discourses that defined PrEP use in a positive light, e.g., challenging stigma. These instances occurred at both the individual and community level, with the former referring to individuals recognizing the benefits of PrEP on one’s physical and mental health (11 articles [21, 29, 31, 33, 35, 49, 65, 66, 80–82], e.g., “I’m 51. I stopped counting my friends who died of AIDS around 95. I say grab this. Hooray for PrEP.” [81, p. 10.]). The latter reflected a responsibility towards protecting one’s community from HIV by “spreading the word” about PrEP to “educate others”, by conveying facts, dispelling misconceptions and reducing common PrEP attributions of “promiscuity,” “risk promotion,” or “anticipated HIV stigma” (e.g., “Rather than stigma or shame, many participants discussed being “proud” and “liberated” because of their PrEP use: “I feel proud because I know that I am doing something positive… I know that I am doing the right thing by keeping myself and other people healthy” [80, p. 26]).

Stigma Dimensions

Based on an expanded stigma framework that includes challenging stigma [38, 46], we further organized identified stigma dimensions in each coded study (Table 3). All stigma dimensions were represented in the coded studies. Experienced stigma was primarily found on the interpersonal level, but also manifested on the institutional level as discrimination from healthcare providers. Enacted stigma was found on the interpersonal level, while perceived stigma occurred on the interpersonal and institutional levels. Anticipated stigma was identified on the interpersonal and community levels, and internalized stigma on the individual level. Expressions of challenging stigma were found on the individual and community levels.

Table 3.

PrEP-related stigma documented in scoping review by stigma dimension and thematic findings

| Stigma dimension | Examples |

|---|---|

| Experienced stigma |

|

| |

| Enacted stigma |

|

| |

| Perceived stigma |

|

| Anticipated stigma |

|

| Internalized stigma |

|

| |

| |

| Challenging stigma |

|

| |

|

Discussion

This scoping review of literature published through April 2020 revealed significant and persistent PrEP-related stigma surrounding this highly efficacious biomedical prevention tool. Multiple types of stigma emerged on four levels of the socioecological model: individual, interpersonal, community, and institutional. The most prevalent types of PrEP-related stigma occurred on the interpersonal level (e.g., discourses around promiscuity and risk-promotion), followed by the institutional (e.g., provider distrust) and individual (e.g., PrEP efficacy distrust) levels. Community-level PrEP stigma was the least represented (e.g., anticipated homonegativity). A notable finding was the emergence of PrEP-positive attitudes at the individual (e.g., empowerment, health self-efficacy, improved mental health) and community (sense of responsibility of educating others on the benefits of PrEP) levels. To support the uptake potential of this paradigm-shifting biomedical tool, we discuss our findings as to guide future intervention research towards improved PrEP promotion and clinical implementation.

Sex negativity dominated the interpersonal level focused on judgments and shaming of certain specific behaviors, with risk-promotion (e.g., engaging in condomless sex) and promiscuity (e.g., having multiple partners) being the first and second most common manifestations of PrEP-related stigma. Framing PrEP as promoting of sexual risk was just as frequently endorsed as it was anticipated by participants in these studies, suggesting that wide-canvasing interventions are needed to further emphasize the value of PrEP and the health-bolstering accountability rather than promiscuity of PrEP users. It also appears that beliefs of risk compensation (e.g., decreased condom use once on PrEP) continue to persist, suggesting that interventions targeting healthcare providers and communities would benefit from conveying evidence-based findings around unfounded postulations of risk compensation among PrEP users [11, 89–92].

To further counteract pervasive negative views on PrEP, far-reaching attitude-changing interventions, likely via social media (e.g., Twitter, Instagram, Facebook) and public campaigns (e.g., on buses, television commercials, and healthcare facilities) may alter these trends to further increase awareness around PrEP benefits and promote a discourse of empowerment and responsibility towards one’s health and the health of the community at large. Relatedly, the positive attitudes many PrEP users endorsed around having a sense of responsibility to educate others about the benefits of PrEP at the community-level may be considered as both a shift away from stigma towards resilience, and an avenue to promote PrEP-positive messaging that may permeate communities to reduce attitudes of risk, promiscuity and homonegativity. Community-level interventions remain critical, especially in the light of PrEP stigma being partially rooted within the LGBTQ community itself [34, 93, 94].

The institutional level followed the interpersonal level in reports of PrEP-related barriers. Reverberating a multitude of reports of provider unwillingness or unpreparedness to counsel on and prescribe PrEP [27, 67, 95–102], our review contributes accounts from patients experiencing a range of institutional-level negative encounters when seeking PrEP, which may be characterized as an intersection of homonegative and sex-negative views. Provider-level barriers thus persist, close to a decade after PrEP’s FDA approval. These reports speak to the modest success of continuing education to influence clinical practice in support of PrEP, demanding more rigorous intervention efforts to assess the most efficacious approaches to integrating this prevention modality into standard-of-care within primary care, emergency departments, and community programs [103–105]. Clustering PrEP expertise within infectious disease and sexual health clinics, or within LGBT-serving clinics, will continue to limit access for patients who may not utilize these care points and constitute missed opportunities for essential PrEP-related education for primary care providers [5]. The current limited PrEP availability in select points of care may also perpetuate the stigmatizing idea that PrEP is only for certain populations with high risk behaviors [29, 35, 106], and not capture the broader approach of vulnerability to HIV due to a multitude of socially-determined factors (e.g., intersectional stigma, low resources, poor healthcare access). Lastly, although not highly prevalent, distrust in public health entities, the government, pharmaceutical companies, and medical institutions persists, which may be perceived as promoting PrEP for profit and not for the well-being of its users. Building patient-centered PrEP counseling approaches, where PrEP candidates engage in shared decision making as they consider this prevention option, alongside others (e.g., barrier methods, abstinence) [107], may be an avenue to build trust for those who continue to be apprehensive about institutional motives behind PrEP promotion.

At the individual level, and related to the above, themes of PrEP efficacy distrust emerged, even after PrEP efficacy had been confirmed in multiple large trials and demonstration studies [104, 108, 109]. It is possible that scientific findings are not adequately disseminated across levels beyond medical and academic circles, in order to reach consumers. The tools of intervention research may be leveraged in assessing the most effective attitude-change strategies in conveying factual PrEP information, such as having audiences identify with and trust the “messengers” who may be peers or respected leaders and organizations [110]. While the least number of themes related to PrEP stigma manifested at the community level, efforts to reduce perceptions of negative PrEP associations with the LGBTQ community are worth considering. Campaigns representative of diversity, which are visible to the general population rather than exclusive to certain so-perceived “risk groups” present the promise of normalizing PrEP as an option to prevent HIV for anyone who is or may become sexually active. Family-level interventions via pediatric and adolescent clinics may lend effective avenues for PrEP awareness-raising and potential uptake by upcoming youth generations, and follow a similar successful path taken for human papilloma virus prevention [111]. This recommendation supports the infusion of PrEP in primary care, sexual health curricula and student health services, such that the odds of this medication becoming a standard-of-care option similar to vaccinations or routine HIV/STI testing, are increased.

Our findings uncover new potential avenues for PrEP promotion, within society at large and clinical practice, by revealing distinctly emerging PrEP-positive discourses challenging of stigma, and suggestive of new research directions. While our primary goal was to establish the extent of PrEP stigma literature, a clear message emerged across studies reflective of positive evaluations of PrEP [29, 33, 35, 65, 66, 80–82]. These conveyed suddenly “game-changing” messages of alleviated mental and physical health threats across over three decades of the HIV/AIDS epidemic. Our findings uncovered discourses of empowerment, personal and community responsibility, and the unprecedented opportunity to dissociate sexuality and pleasure from the previously omnipresent fear of “contagion”, associated stigma and death [112]. While there is emerging interest in this direction [113], no empirical work to date has challenged PrEP-associated stigma (e.g., homonegativity, promiscuity) at its core. Several of the studies included in this review described participants’ positive views on PrEP, without explicitly discussing mechanisms to challenge stigma within the context of PrEP. The specific concept of challenging stigma derived from popular social media discourses reclaiming the derogatory term “Truvada whore” [28, 114]. Following these early studies, researchers have identified challenging stigma as a prominent theme in stigma discourse [38, 115], however, challenging stigma is yet to be adopted by the PrEP stigma intervention research to explore its potential to reframe PrEP-negative discourses, on multiple socioecological levels, to increase PrEP utilization.

Notably, several PrEP-related stigma interventions are under way. Our search of clinicaltrials.gov and collective knowledge of active PrEP stigma research revealed five ongoing studies that specifically aim to address PrEP stigma. “Empowering with PrEP” [116] includes PrEP stigma as a secondary outcome measure, defined as “any stigma the participant might have about PrEP or those who use PrEP. In “Value Affirmation and Future Selves” [117], the primary outcome measure is PrEP adherence. The study design is a parallel group randomized, controlled clinical trial to test a behavioral intervention that aims to increase individual resilience against PrEP-related stigma. “Project Jumpstart” [118] uses cognitive behavioral theory to develop an intervention model based on the HIV Stigma Framework and the Medication Necessity-Concerns Framework to increase PrEP uptake, adherence, and persistence. “A Cognitive Behavioral Therapy Group Intervention” [119] examines effective coping, including internalized and anticipated stigma, and medical distrust, as a mechanism of PrEP uptake among Latinx MSM. Finally, “PrEP2Prevent” (pending; R34DA050531; PI: Kipke) entails the development of a mobile app to support PrEP navigation, and will also include evaluation of PrEP stigma as a mediating mechanism for PrEP engagement.

Much of the formative work on challenging stigma is rooted within resilience theory [120], utilizing a strength-based approach instead of focusing on deficits, which poses the risk of reinforcing negative stereotypes [50, 115, 121]. A resilience approach supports the processes through which individuals navigate and counter adversity [122], which may be translated into interventions. For example, individual-level, empowering interventions could be embedded into PrEP counseling sessions, where documentation is provided on barriers to health that may be removed by PrEP use, such as high protection against HIV, improved mental health and general health self-efficacy and accountability, and lowered stigma against HIV-positive people. Provider-level interventions that challenge stigma could entail modules focused on the relationship between provider stigmatization of patient identities, leading to health inequities. This approach would raise awareness of stigma-driven differential treatment by providers of certain groups that is detrimental to their health. For example, providers should be made aware of the evidence indicative of how providers often discuss PrEP with highly sexually active patients by making attributes of promiscuity, or shaming patients who may have multiple sexual partners or same-sex partners. Intervention components that would remove both provider implicit and explicit bias around sexuality and shift the focus on PrEP as an avenue for individual empowerment and accountability would directly address PrEP stigma, increase patient trust in providers and foster affirming patient–provider communication. Lastly, adopting an intersectional perspective, these interventions may layer sexuality bias reduction with reducing racial/ethnic bias of white providers, which continues to linger and lead to underserving people of color. Simultaneous patient–provider interventions may be capable of orchestrating attitudinal and behavioral change on both levels.

A clear gap revealed by our review is the relative lack of studies investigating structural-level stigma, including systematic discrimination in laws and policies both in civic society at large, and in healthcare-related areas such as Medicaid [55]. A multi-level approach to address stigma has been called for [123], and literature has begun to emerge addressing this need [124]. Furthermore, given the complexity of stigma manifestations, an updated review of stigma measurements would be beneficial in bolstering research around stigma reduction interventions, particularly those adapted to measure PrEP-related stigma. Since Earnshaw’s review of HIV stigma mechanisms measures in 2009 [125], a number of validated instruments for measuring stigma have emerged [41, 42]. Our scoping review illustrates a heavy focus on qualitative methods in the quest for understanding the operationalization of stigma on all the levels of the socioecological model. Longitudinal, quantitative work is needed to nuance our understanding of stigma processes beyond hypothesis generation, and to establish causal relationships around PrEP uptake, adherence and persistence.

Limitations

Several limitations emerged. Because stigma is determined by social, political and cultural factors, we did not include studies outside of North America, given our scope of recommending future directions in PrEP promotion that are contextually-tied. Thus, studies reflective of PrEP attitudes in other regions of the world were omitted, reducing potential for immediate generalizability to other contexts without considerable inquiries within local PrEP-related discourses. Further, the time span for this literature is for the time being limited, given that the earliest publication was 5 years ago. This both restricts the sample of potential data points and our ability to understand fluctuations in PrEP-related stigma, including its potential attenuation in favor of increasingly positive attitudes across time. This suggests the benefits of continued monitoring of this literature to observe such potential changes. Additionally, the reviewed literature focused on currently FDA-approved PrEP modalities (e.g., daily oral regimens), and stigma related to alternative PrEP use strategies (e.g., on-demand, long-acting) is worth investigating as this literature emerges. Importantly, no evident research has investigated PrEP-related stigma towards and among transmen. This is a notable gap in knowledge given that many transmen who have sex with men are in fact at risk for HIV and experience a range of unique stigma types likely to affect their PrEP uptake and persistence [37]. Lastly, existing PrEP stigma literature did not include HIV-positive individuals whose opinions are likely to be important given they may be ones discussing this strategy with their partners.

Conclusion

This scoping review revealed multiple manifestations of PrEP-related stigma, at four levels of the socioecological model, including in the most recently published literature. While interventions to directly modify negative PrEP attitudes at various levels need to continue, PrEP proponents may be well-served by leveraging increasing PrEP-positive discourses that appear to be occurring organically and are already challenging manifestations of PrEP-related stigma. Adopting a resilience and strengths-based approach could increase consumer and community awareness of and education around PrEP benefits and efficacy, and promote an affirmative discourse of the health value of PrEP to revert negative attribution of sexual risk promotion and promiscuity. Furthermore, direct efforts to increase provider willingness to educate themselves around and promote PrEP routinely remain essential, in order to reduce provider bias and patient distrust, and align with the national strategy to End the HIV Epidemic in the U.S. [7].

Conflict of interest

Dr. Rosengren-Hovee is supported by Gilead Sciences under the Research Scholars Program. She has no other conflicts of interest to report. Dr. Lelutiu-Weinberger, Dr. Woodhouse, Ms. Sandanapitchai, and Dr. Hightow-Weidman have no conflicts of interest to report.

Funding

No funding supported this work.

Footnotes

Ethical Approval No human or animal subjects were involved in this research. As such, IRB approval was not required.

Research Involving Human Participants and/or Animals This article does not contain any studies involving human participants performed by any of the authors.

Informed Consent No human subjects were involved in this research. As such, informed consent was not applicable.

References

- 1.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV Basics Atlanta, GA. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/basics/statistics.html.

- 2.Katz IT, Ehrenkranz P, El-Sadr W. The global HIV epidemic: what will it take to get to the finish line? JAMA. 2018;319(11):1094–5. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Carey JW, Carnes N, Schoua-Glusberg A, Kenward K, Gelaude D, Denson D, et al. Barriers and facilitators for clinical care engagement among HIV-positive African American and Latino men who have sex with men. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2018;32(5):191–201. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Hightow-Weidman L, LeGrand S, Choi SK, Egger J, Hurt CB, Muessig KE. Exploring the HIV continuum of care among young black MSM. PLoS One. 2017;12(6):e0179688. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Golub SA. Enhancing PrEP access for Black and Latino men who have sex with men. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2016;73(5):547–55. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV and African American Gay and Bisexual Men: Atlanta, GA. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/group/msm/bmsm.html. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Fauci AS, Redfield RR, Sigounas G, Weahkee MD, Giroir BP. Ending the HIV epidemic: a plan for the United States. JAMA. 2019;321:844. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV surveillance report, 2017. 2018. Nov.

- 9.United States. National HIV/AIDS strategy for the United States: updated to 2020. Washington, DC: White House Office of National AIDS Policy; 2020. [Google Scholar]

- 10.Safren SA, Mayer KH, Ou SS, McCauley M, Grinsztejn B, Hosseinipour MC, et al. Adherence to early antiretroviral therapy: results from HPTN 052, a phase III, multinational randomized trial of ART to prevent HIV-1 sexual transmission in serodiscordant couples. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2015;69(2):234–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Grant RM, Lama JR, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu AY, Vargas L, et al. Preexposure chemoprophylaxis for HIV prevention in men who have sex with men. N Engl J Med. 2010;363(27):2587–99. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Hojilla JC, Vlahov D, Crouch PC, Dawson-Rose C, Freeborn K, Carrico A. HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) uptake and retention among men who have sex with men in a community-based sexual health clinic. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(4):1096–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Chan PA, Mena L, Patel R, Oldenburg CE, Beauchamps L, Perez-Brumer AG, et al. Retention in care outcomes for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis implementation programmes among men who have sex with men in three US cities. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1):20903. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Eaton LA, Kalichman SC, Price D, Finneran S, Allen A, Maksut J. Stigma and conspiracy beliefs related to pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) and interest in using PrEP among Black and White men and transgender women who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(5):1236–46. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Thoma BC, Huebner DM. Brief report: HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis engagement among adolescent men who have sex with men: the role of parent-adolescent communication about sex. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2018;79(4):453–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Perez-Figueroa RE, Kapadia F, Barton SC, Eddy JA, Halkitis PN. Acceptability of PrEP uptake among racially/ethnically diverse young men who have sex with men: the P18 study. AIDS Educ Prev Off Publ Int Soc AIDS Educ. 2015;27(2):112–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Bauermeister JA, Meanley S, Pingel E, Soler JH, Harper GW. PrEP awareness and perceived barriers among single young men who have sex with men. Curr HIV Res. 2013;11(7):520–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Holloway IW, Tan D, Gildner JL, Beougher SC, Pulsipher C, Montoya JA, et al. Facilitators and barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis willingness among young men who have sex with men who use geosocial networking applications in California. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2017;31(12):517–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Bogart LM, Landrine H, Galvan FH, Wagner GJ, Klein DJ. Perceived discrimination and physical health among HIV-positive Black and Latino men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2013;17(4):1431–41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Mustanski B, Morgan E, D’Aquila R, Birkett M, Janulis P, Newcomb ME. Individual and network factors associated with racial disparities in HIV among young men who have sex with men: results from the RADAR cohort study. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2019;80(1):24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Hubach RD, Currin JM, Sanders CA, Durham AR, Kavanaugh KE, Wheeler DL, et al. Barriers to access and adoption of pre-exposure prophylaxis for the prevention of HIV among men who have sex with men (MSM) in a relatively rural state. AIDS Educ Prev Off Publ Int Soc AIDS Educ. 2017;29(4):315–29. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Mirza SA, Rooney C. Discrimination prevents LGBTQ people from accessing health care. Washington, D.C.: Center for American Progress; 2018. [Google Scholar]

- 23.Fisher CB, Fried AL, Desmond M, Macapagal K, Mustanski B. Facilitators and barriers to participation in PrEP HIV prevention trials involving transgender male and female adolescents and emerging adults. AIDS Educ Prev Off Publ Int Soc AIDS Educ. 2017;29(3):205–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Wilson EC, Arayasirikul S, Johnson K. Access to HIV care and support services for African American transwomen living with HIV. Int J Transgenderism. 2013;14(4):182–95. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Freeman R, Gwadz MV, Silverman E, Kutnick A, Leonard NR, Ritchie AS, et al. Critical race theory as a tool for understanding poor engagement along the HIV care continuum among African American/Black and Hispanic persons living with HIV in the United States: a qualitative exploration. Int J Equity Health. 2017;16(1):54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Paradies Y, Ben J, Denson N, Elias A, Priest N, Pieterse A, et al. Racism as a determinant of health: a systematic review and meta-analysis. PloS One. 2015;10(9):e0138511-e. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Quinn K, Dickson-Gomez J, Zarwell M, Pearson B, Lewis M. “A gay man and a doctor are just like, a recipe for destruction”: how racism and homonegativity in healthcare settings influence PrEP uptake among young Black MSM. AIDS Behav. 2018;23:1951–63. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Spieldenner A PrEP Whores and HIV prevention: the Queer communication of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP). J Homosex. 2016;63(12):1685–97. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Thomann M, Grosso A, Zapata R, Chiasson MA. ‘WTF is PrEP?’: attitudes towards pre-exposure prophylaxis among men who have sex with men and transgender women in New York City. Cult Health Sex. 2018;20(7):772–86. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Newman PA, Guta A, Lacombe-Duncan A, Tepjan S. Clinical exigencies, psychosocial realities: negotiating HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis beyond the cascade among gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men in Canada. J Int AIDS Soc. 2018;21(11):e25211. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Brooks RA, Landrian A, Nieto O, Fehrenbacher A. Experiences of anticipated and enacted pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) stigma among Latino MSM in Los Angeles. AIDS Behav. 2019;23:1964–73. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Brooks RA, Nieto O, Landrian A, Donohoe TJ. Persistent stigmatizing and negative perceptions of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) users: implications for PrEP adoption among Latino men who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2019;31(4):427–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mustanski B, Ryan DT, Hayford C, Phillips G 2nd, Newcomb ME, Smith JD. Geographic and individual associations with PrEP stigma: results from the RADAR cohort of diverse young men who have sex with men and transgender women. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(9):3044–56. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Dubov A, Galbo P Jr, Altice FL, Fraenkel L. Stigma and shame experiences by MSM who take PrEP for HIV prevention: a qualitative study. Am J Men’s Health. 2018;12(6):1843–54. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Knight R, Small W, Carson A, Shoveller J. Complex and conflicting social norms: implications for implementation of future HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) interventions in Vancouver, Canada. PLoS One. 2016;11(1):e0146513. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Young I, Flowers P, McDaid LM. Barriers to uptake and use of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) among communities most affected by HIV in the UK: findings from a qualitative study in Scotland. BMJ Open. 2014;4(11):e005717. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Reisner SL, Moore CS, Asquith A, Pardee DJ, Sarvet A, Mayer G, et al. High risk and low uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis to prevent HIV acquisition in a national online sample of transgender men who have sex with men in the United States. J Int AIDS Soc. 2019;22(9):e25391. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Bauermeister JA, Muessig KE, LeGrand S, Flores DD, Choi SK, Dong W, et al. HIV and sexuality stigma reduction through engagement in online forums: results from the HealthMPowerment intervention. AIDS Behav. 2019;23(3):742–52. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Steward WT, Herek GM, Ramakrishna J, Bharat S, Chandy S, Wrubel J, et al. HIV-related stigma: adapting a theoretical framework for use in India. Soc Sci Med (1982). 2008;67(8):1225–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kalichman SC, Simbayi LC, Cloete A, Mthembu PP, Mkhonta RN, Ginindza T. Measuring AIDS stigmas in people living with HIV/AIDS: the Internalized AIDS-Related Stigma Scale. AIDS Care. 2009;21(1):87–93. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Stahlman S, Hargreaves JR, Sprague L, Stangl AL, Baral SD. Measuring sexual behavior stigma to inform effective HIV prevention and treatment programs for key populations. JMIR Public Health Surveill. 2017;3(2):e23. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.McAteer CI, Truong NT, Aluoch J, Deathe AR, Nyandiko WM, Marete I, et al. A systematic review of measures of HIV/AIDS stigma in paediatric HIV-infected and HIV-affected populations. J Int AIDS Soc. 2016;19(1):21204. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Wilkinson AL, Draper BL, Pedrana AE, Asselin J, Holt M, Hellard ME, et al. Measuring and understanding the attitudes of Australian gay and bisexual men towards biomedical HIV prevention using cross-sectional data and factor analyses. Sex Transm Infect. 2018;94(4):309–14. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Garnett M, Hirsch-Moverman Y, Franks J, Hayes-Larson E, El-Sadr WM, Mannheimer S. Limited awareness of pre-exposure prophylaxis among black men who have sex with men and transgender women in New York city. AIDS Care. 2018;30(1):9–17. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 45.Walsh JL. Applying the information-motivation-behavioral skills model to understand PrEP intentions and use among men who have sex with men. AIDS Behav. 2018;23:1904–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Turan B, Hatcher AM, Weiser SD, Johnson MO, Rice WS, Turan JM. Framing mechanisms linking HIV-related stigma, adherence to treatment, and health outcomes. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(6):863–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Fox AB, Earnshaw VA, Taverna EC, Vogt D. Conceptualizing and measuring mental illness stigma: the mental illness stigma framework and critical review of measures. Stigma Health. 2018;3(4):348–76. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Golub SA, Gamarel KE. The impact of anticipated HIV stigma on delays in HIV testing behaviors: findings from a community-based sample of men who have sex with men and transgender women in New York City. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2013;27(11):621–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Golub SA, Gamarel KE, Surace A. Demographic differences in PrEP-related stereotypes: implications for implementation. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(5):1229–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Barry MC, Threats M, Blackburn NA, LeGrand S, Dong W, Pulley DV, et al. “Stay strong! keep ya head up! move on! it gets better!!!!”: resilience processes in the healthMpowerment online intervention of young black gay, bisexual and other men who have sex with men. AIDS Care. 2018;30(sup5):S27–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Meanley S, Yehia BR, Hines J, Thomas R, Calder D, Carter B, et al. HIV/AIDS-related stigma, immediate families, and proactive coping processes among a clinical sample of people living with HIV/AIDS in Philadelphia, Pennsylvania. J Community Psychol. 2019;47(7):1787–98. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Harper GW, Wagner RL, Popoff E, Reisner SL, Jadwin-Cakmak L. Psychological resilience among transfeminine adolescents and emerging adults living with HIV. AIDS (London, England). 2019;33(Suppl 1):S53–62. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Hussen SA, Harper GW, Rodgers CRR, van den Berg JJ, Dowshen N, Hightow-Weidman LB. Cognitive and behavioral resilience among young gay and bisexual men living with HIV. LGBT Health. 2017;4(4):275–82. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Bruce D, Harper GW, Bauermeister JA. Minority stress, positive identity development, and depressive symptoms: implications for resilience among sexual minority male youth. Psychol Sex Orientat Gend Divers. 2015;2(3):287–96. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Oldenburg CE, Perez-Brumer AG, Hatzenbuehler ML, Krakower D, Novak DS, Mimiaga MJ, et al. State-level structural sexual stigma and HIV prevention in a national online sample of HIV-uninfected MSM in the United States. AIDS (London, England). 2015;29(7):837–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 56.Viruell-Fuentes EA, Miranda PY, Abdulrahim S. More than culture: structural racism, intersectionality theory, and immigrant health. Soc Sci Med (1982). 2012;75(12):2099–106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 57.Cole ER. Intersectionality and research in psychology. Am Psychol. 2009;64(3):170–80. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 58.Bronfenbrenner U The ecology of human development: experiments by nature and design. Cambridge: Harvard University Press; 1979. [Google Scholar]

- 59.Hosek SG, Harper GW, Lemos D, Martinez J. An ecological model of stressors experienced by youth newly diagnosed with HIV. J HIV/AIDS Prev Child Youth. 2008;9(2):192–218. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 60.Earnshaw VA, Smith LR, Chaudoir SR, Lee IC, Copenhaver MM. Stereotypes about people living with HIV: implications for perceptions of HIV risk and testing frequency among at-risk populations. AIDS Educ Prev Off Publ Int Soc AIDS Educ. 2012;24(6):574–81. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 61.Philbin MM, Parker CM, Parker RG, Wilson PA, Garcia J, Hirsch JS. The promise of pre-exposure prophylaxis for Black men who have sex with men: an ecological approach to attitudes, beliefs, and barriers. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2016;30(6):282–90. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 62.Herek GM, Gillis JR, Cogan JC. Internalized stigma among sexual minority adults: insights from a social psychological perspective. J Couns Psychol. 2009;56(1):32–43. [Google Scholar]

- 63.Vincent W, Pollack LM, Huebner DM, Peterson JL, Steward WT, Rebchook GM, et al. HIV risk and multiple sources of heterosexism among young Black men who have sex with men. J Consult Clin Psychol. 2017;85(12):1122–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 64.Goedel WC, Halkitis PN, Greene RE, Duncan DT. Correlates of awareness of and willingness to use pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) in gay, bisexual, and other men who have sex with men who use geosocial-networking smartphone applications in New York City. AIDS Behav. 2016;20(7):1435–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 65.Mutchler MG, McDavitt B, Ghani MA, Nogg K, Winder TJ, Soto JK. Getting PrEPared for HIV prevention navigation: young Black gay men talk about HIV prevention in the biomedical era. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2015;29(9):490–502. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 66.Franks J, Hirsch-Moverman Y, Loquere AS Jr, Amico KR, Grant RM, Dye BJ, et al. Sex, PrEP, and stigma: experiences with HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis among New York City MSM participating in the HPTN 067/ADAPT study. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(4):1139–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 67.Cahill S, Taylor SW, Elsesser SA, Mena L, Hickson D, Mayer KH. Stigma, medical mistrust, and perceived racism may affect PrEP awareness and uptake in black compared to white gay and bisexual men in Jackson, Mississippi and Boston, Massachusetts. AIDS Care. 2017;29(11):1351–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 68.Kessler RC, Mickelson KD, Williams DR. The prevalence, distribution, and mental health correlates of perceived discrimination in the United States. J Health Soc Behav. 1999;40(3):208–30. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 69.Relf MV, Pan W, Edmonds A, Ramirez C, Amarasekara S, Adimora AA. Discrimination, medical distrust, stigma, depressive symptoms, antiretroviral medication adherence, engagement in care, and quality of life among women living with HIV in North Carolina: a mediated structural equation model. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2019;81(3):328–35. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 70.Williams DR, Mohammed SA. Discrimination and racial disparities in health: evidence and needed research. J Behav Med. 2009;32(1):20–47. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 71.Whetten K, Leserman J, Whetten R, Ostermann J, Thielman N, Swartz M, et al. Exploring lack of trust in care providers and the government as a barrier to health service use. Am J Public Health. 2006;96(4):716–21. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 72.Prasad A Uché Blackstock: dismantling structural racism in health care. Lancet (London, England). 2020;396(10252):659. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 73.Centers for Disease Control and Prevention. HIV in the United States by Region Atlanta, GA. https://www.cdc.gov/hiv/statistics/overview/geographicdistribution.html.

- 74.Munn Z, Peters MDJ, Stern C, Tufanaru C, McArthur A, Aromataris E. Systematic review or scoping review? Guidance for authors when choosing between a systematic or scoping review approach. BMC Med Res Methodol. 2018;18(1):143. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 75.Tricco AC, Lillie E, Zarin W, O’Brien KK, Colquhoun H, Levac D, et al. PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-ScR): checklist and explanation. Ann Intern Med. 2018;169(7):467–73. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 76.Rao D, Elshafei A, Nguyen M, Hatzenbuehler ML, Frey S, Go VF. A systematic review of multi-level stigma interventions: state of the science and future directions. BMC Med. 2019;17(1):41. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 77.Hatzenbuehler ML. Structural stigma: research evidence and implications for psychological science. Am Psychol. 2016;71(8):742–51. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 78.Fairclough N Critical discourse analysis and critical policy studies. Crit Policy Stud. 2013;7(2):177–97. [Google Scholar]

- 79.Charmaz K Grounded theory as an emergent method. In: Hesse-Biber SN, Leavy P, editors. Handbook of emergent methods. Guilford Press; 2008. p. 155–72. [Google Scholar]

- 80.Grace D, Jollimore J, MacPherson P, Strang MJP, Tan DHS. The pre-exposure prophylaxis-stigma paradox: learning from Canada’s first wave of PrEP users. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2018;32(1):24–30. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 81.Grimm J, Schwartz J. “It’s like birth control for HIV”: communication and stigma for gay men on PrEP. J Homosex. 2018;66(9):1–19. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 82.Pawson M, Grov C. ‘It’s just an excuse to slut around’: gay and bisexual mens’ constructions of HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) as a social problem. Sociol Health Illn. 2018;40(8):1391–403. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 83.Farhat D, Greene E, Paige MQ, Koblin BA, Frye V. Knowledge, stereotyped beliefs and attitudes around HIV chemoprophylaxis in two high HIV prevalence neighborhoods in New York City. AIDS Behav. 2017;21(5):1247–55. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 84.Eaton LA, Matthews DD, Driffin DD, Bukowski L, Wilson PA, Stall RD. A multi-US City assessment of awareness and uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention among Black men and transgender women who have sex with men. Prev Sci Off J Soc Prev Res. 2017;18(5):505–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 85.Garcia M, Harris AL. PrEP awareness and decision-making for Latino MSM in San Antonio, Texas. PLoS One. 2017;12(9):e0184014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 86.Golub SA, Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Surace A. Experimental investigation of implicit HIV and preexposure prophylaxis stigma: evidence for ancillary benefits of preexposure prophylaxis use. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2018;77(3):264–71. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 87.Jaiswal J, Griffin M, Singer SN, Greene RE, Acosta ILZ, Kaudeyr SK, et al. Structural barriers to pre-exposure prophylaxis use among young sexual minority men: the P18 cohort study. Curr HIV Res. 2018;16(3):237–49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 88.Refugio ON, Kimble MM, Silva CL, Lykens JE, Bannister C, Klausner JD. Brief report: PrEPTECH: a telehealth-based initiation program for HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis in young men of color who have sex with men. A pilot study of feasibility. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr. 2019;80(1):40–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 89.Marcus JL, Glidden DV, Mayer KH, Liu AY, Buchbinder SP, Amico KR, et al. No evidence of sexual risk compensation in the iPrEx trial of daily oral HIV preexposure prophylaxis. PLoS One. 2013;8(12):e81997. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 90.Thigpen MC, Kebaabetswe PM, Paxton LA, Smith DK, Rose CE, Segolodi TM, et al. Antiretroviral preexposure prophylaxis for heterosexual HIV transmission in Botswana. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):423–34. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 91.Baeten JM, Donnell D, Ndase P, Mugo NR, Campbell JD, Wangisi J, et al. Antiretroviral prophylaxis for HIV prevention in heterosexual men and women. N Engl J Med. 2012;367(5):399–410. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 92.Grant RM, Anderson PL, McMahan V, Liu A, Amico KR, Mehrotra M, et al. Uptake of pre-exposure prophylaxis, sexual practices, and HIV incidence in men and transgender women who have sex with men: a cohort study. Lancet Infect Dis. 2014;14(9):820–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 93.Herron PD. Ethical implications of social stigma associated with the promotion and use of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention. LGBT Health. 2016;3(2):103–8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 94.Golub SA. PrEP stigma: implicit and explicit drivers of disparity. Curr HIV/AIDS Rep. 2018;15(2):190–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 95.Calabrese SK, Earnshaw VA, Underhill K, Hansen NB, Dovidio JF. The impact of patient race on clinical decisions related to prescribing HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): assumptions about sexual risk compensation and implications for access. AIDS Behav. 2014;18(2):226–40. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 96.Calabrese SK, Earnshaw VA, Krakower DS, Underhill K, Vincent W, Magnus M, et al. A closer look at racism and heterosexism in medical students’ clinical decision-making related to HIV pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP): implications for PrEP education. AIDS Behav. 2018;22(4):1122–38. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 97.Adams LM, Balderson BH. HIV providers’ likelihood to prescribe pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention differs by patient type: a short report. AIDS Care. 2016;28(9):1154–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 98.Clement ME, Seidelman J, Wu J, Alexis K, McGee K, Okeke NL, et al. An educational initiative in response to identified PrEP prescribing needs among PCPs in the Southern U.S. AIDS Care. 2018;30(5):650–5. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 99.Desai M, Gafos M, Dolling D, McCormack S, Nardone A. Healthcare providers’ knowledge of, attitudes to and practice of pre-exposure prophylaxis for HIV infection. HIV Med. 2016;17(2):133–42. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 100.Maksut JL, Eaton LA, Siembida EJ, Fabius CD, Bradley AM. Health care discrimination, sex behavior disclosure, and awareness of pre-exposure prophylaxis among Black men who have sex with men. Stigma Health. 2018;3(4):330–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 101.Maloney KM, Krakower DS, Ziobro D, Rosenberger JG, Novak D, Mayer KH. Culturally competent sexual healthcare as a prerequisite for obtaining preexposure prophylaxis: findings from a qualitative study. LGBT Health. 2017;4(4):310–4. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 102.Mullins TLK, Zimet G, Lally M, Xu J, Thornton S, Kahn JA. HIV care providers’ intentions to prescribe and actual prescription of pre-exposure prophylaxis to at-risk adolescents and adults. AIDS Patient Care STDs. 2017;31(12):504–16. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 103.Calabrese SK, Krakower DS, Mayer KH. Integrating HIV preexposure prophylaxis (PrEP) into routine preventive health care to avoid exacerbating disparities. Am J Public Health. 2017;107(12):1883–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 104.Liu A, Cohen S, Follansbee S, Cohan D, Weber S, Sachdev D, et al. Early experiences implementing pre-exposure prophylaxis (PrEP) for HIV prevention in San Francisco. PLoS Med. 2014;11(3):e1001613. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 105.Krakower D, Mayer KH. What primary care providers need to know about preexposure prophylaxis for HIV prevention: a narrative review. Ann Intern Med. 2012;157(7):490–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 106.Garcia J, Parker C, Parker RG, Wilson PA, Philbin M, Hirsch JS. Psychosocial implications of homophobia and HIV stigma in social support networks: insights for high-impact HIV prevention among Black men who have sex with men. Health Educ Behav Off Publ Soc Public Health Educ. 2016;43(2):217–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 107.Golub SA, Peña A, Hilley A, Pachankis J, Radix A, editors. Brief behavioral intervention increases PrEP drug levels in a real-world setting. Conference on Retroviruses and Opportunistic Infections (CROI); 13–16 Feb, 2017; Seattle, WA. [Google Scholar]

- 108.Liu AY, Vittinghoff E, Chillag K, Mayer K, Thompson M, Grohskopf L, et al. Sexual risk behavior among HIV-uninfected men who have sex with men participating in a tenofovir pre-exposure prophylaxis randomized trial in the United States. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2013;64(1):87–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 109.Donnell D, Baeten JM, Bumpus NN, Brantley J, Bangsberg DR, Haberer JE, et al. HIV protective efficacy and correlates of tenofovir blood concentrations in a clinical trial of PrEP for HIV prevention. J Acquir Immune Defic Syndr (1999). 2014;66(3):340–8. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 110.Lelutiu-Weinberger C, Wilton L, Koblin BA, Hoover DR, Hirshfield S, Chiasson MA, et al. The role of social support in HIV testing and PrEP awareness among young Black men and transgender women who have sex with men or transgender women. J Urban Health Bull NY Acad Med. 2020;97:715–27. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 111.Smith PJ, Stokley S, Bednarczyk RA, Orenstein WA, Omer SB. HPV vaccination coverage of teen girls: the influence of health care providers. Vaccine. 2016;34(13):1604–10. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]