Abstract

Introduction

Previous studies have proposed a possible gut–skin axis, and linked gut microbiota to psoriasis risks. However, there is heterogeneity in existing evidence. Observational research is prone to bias, and it is hard to determine causality. Therefore, this study aims to evaluate possible causal associations between gut microbiota (GM) and psoriasis.

Methods

With published large-scale GWAS (genome-wide association study) summary datasets, two-sample Mendelian randomization (MR) was performed to sort out possible causal roles of GM in psoriasis and arthropathic psoriasis (PsA). The inverse variance weighted (IVW) method was taken as the primary evaluation of causal association. As complements to the IVW method, we also applied MR-Egger, weighted median. Sensitivity analyses were conducted using Cochrane’s Q test, MR-Egger intercept test, MR-PRESSO (Mendelian Randomization Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Outlier) global test, and leave-one-out analysis.

Results

By primary IVW analysis, we identified nominal protective roles of Bacteroidetes (odds ratio, OR 0.81, P = 0.033) and Prevotella9 (OR 0.87, P = 0.045) in psoriasis risks. Bacteroidia (OR 0.65, P = 0.03), Bacteroidales (OR 0.65, P = 0.03), and Ruminococcaceae UCG002 (OR 0.81, P = 0.038) are nominally associated with lower risks for PsA. On the other hand, Pasteurellales (OR 1.22, P = 0.033), Pasteurellaceae (OR 1.22, P = 0.033), Blautia (OR 1.46, P = 0.014), Methanobrevibacter (OR 1.27, P = 0.026), and Eubacterium fissicatena group (OR 1.21, P = 0.028) are nominal risk factors for PsA. Additionally, E. fissicatena group is a possible risk factor for psoriasis (OR 1.22, P = 0.00018). After false discovery rate (FDR) correction, E. fissicatena group remains a risk factor for psoriasis (PFDR = 0.03798).

Conclusion

We comprehensively evaluated possible causal associations of GM with psoriasis and arthropathic psoriasis, and identified several nominal associations. E. fissicatena group remains a risk factor for psoriasis after FDR correction. Our results offer promising therapeutic targets for psoriasis clinical management.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1007/s13555-023-01007-w.

Keywords: Psoriasis, Gut microbiota, Mendelian randomization, Gut–skin axis, Causal analysis

Key Summary Points

| Why carry out this study? |

| Previous studies have proposed a possible gut–skin axis, and linked gut microbiota to psoriasis risks. |

| Observational research is prone to bias, and it is hard to determine causality. |

| We performed a two-sample Mendelian randomization study to evaluate possible causal association between gut microbiota (GM) with psoriasis. |

| What was learned from the study? |

| Bacteroidetes and Prevotella9 are nominally associated with lower risk for psoriasis. Bacteroidia, Bacteroidales, and Ruminococcaceae UCG002 are nominally associated with lower risks for arthropathic psoriasis. On the other hand, Pasteurellales, Pasteurellaceae, Blautia, Methanobrevibacter, and Eubacterium fissicatena group are nominal risk factors for arthropathic psoriasis, while E. fissicatena group is a risk factor for psoriasis after false discovery rate correction. |

| Further studies are needed to validate these associations between gut microbiota and psoriasis. |

Introduction

Psoriasis is a chronic inflammatory skin disease manifested by red, itchy, and dry skin plaques [1], affecting 0.84% of the population in 2017 [2]. The detailed pathological mechanisms of psoriasis are not fully understood yet. Previously recognized immune dysregulation, hereditary susceptibility, environmental factors, etc. may be associated with psoriasis [1]. Recently, mounting research also reveals an underlying gut–skin axis, where skin and gut are in intimate contact with the immune system and work together to protect from external antigens [3, 4]. As a result of both skin and gut being exposed to a broad range and complicated microbiota, however, there are still large gaps in understanding the associations between gut microbiota and psoriasis.

Gut microbiota refers to the whole microbial population living in the intestinal tract [5]. Gut microbiota play a vital role in physiological activities including protecting from external antigens, providing metabolic activities, and regulating immune system regulation, etc. [4]. Whereas, dysregulation of gut microbiota and gut dysbiosis disrupt immunological tolerance, then subsequently disturb skin immune balance [6]. Growing clinical evidence has linked the alteration of the gut microbiota to psoriasis [7]. For example, Akkermansia muciniphila is significantly reduced in patients with psoriasis than in controls [8]. However, the available epidemiological evidence for these associations is occasionally conflicting, possibly because o selective bias, varied measuring methods, etc. For example, Prevotella levels were reported to be higher [9] or lower [10] in patients with psoriasis than in healthy controls. Though clinical evidence elaborates, shared cofounders, selective bias (e.g., age, gender, region), and heterogeneity in clinical research, all may cloud the understanding of this association between gut microbiota and psoriasis. Studying the mechanism between the gut microbiota and psoriasis, as well as further evaluating a causal association may enhance the understanding of psoriasis mechanisms and offer evidence-based therapeutic targets for clinical management.

Mendelian randomization (MR) estimates the potential causal relationship between exposure and outcome via genetic variants as instrumental variables for the exposure factor of interest [11]. Since genetic variants are assigned at random, the MR approach is not susceptible to confounding factors. It can also avoid the reverse causality bias caused by genetic variants being assigned prior to disease development.

In this study, we aim to evaluate an underlying causal association between the gut microbiota and psoriasis via a Mendelian randomization approach. Hopefully, our findings may benefit the understanding of psoriasis pathological mechanisms, as well as offer potential therapeutic targets for psoriasis clinical management.

Methods

Overall Study Design

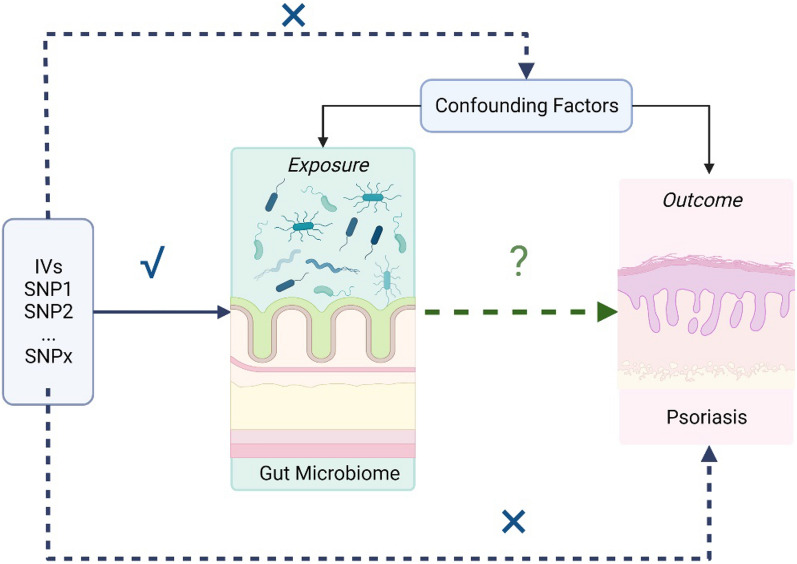

Generally, we conducted a two-sample MR study to evaluate the causal effect between gut microbiota and psoriasis. The validity of MR is based on three main assumptions: (i) the genetic variants selected as instrumental variables (IVs) are associated with gut microbiota as exposure of interest; (ii) the used instrumental variable is not associated with common confounders of exposures and outcomes; (iii) instrumental variables should affect the outcome psoriasis only through the exposure (Fig. 1).

Fig. 1.

Mendelian randomization to assess the causal association between gut microbiota and psoriasis. SNPs single-nucleotide polymorphism, IVs instrumental variables

GWAS Data Sources

For the exposure gut microbiota, the GWAS dataset from MiBioGen consortium comprising 18,340 participants was applied in this study [12]. This GWAS study examined 211 GM taxa by the 16S rRNA method.

As for the main outcome, psoriasis, the GWAS summary statistics consisting of 339,050 individuals, specifically 8075 patients with psoriasis and 330,975, controls were from FinnGen database R8. The GWAS of arthropathic psoriasis comprised 333,887 individuals, specifically 2912 patients with arthropathic psoriasis and 330,975 controls. Psoriasis and arthropathic psoriasis (PsA) in this GWAS were diagnosed following the International Statistical Classification of Diseases (ICD) (Table 1). This study was conducted on the basis of publicly available data from MiBioGen and FinnGen studies and was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments. Ethical approval was granted for each of MiBioGen and FinnGen, and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation. Patient personal information in the databases is unidentifiable.

Table 1.

Summary of genome-wide association studies (GWAS) datasets included in our study

| Trait | Year | Population | Sources | Sample sizes | Cases | Controls |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Exposure | ||||||

| 211 GM taxa | 2021 | 72.3% European | MiBioGen | 18,340 | – | – |

| Outcome | ||||||

| Psoriasis | 2022 | European | FinnGen (R8) | 339,050 | 8075 | 330,975 |

| Arthropathic psoriasis | 2022 | European | FinnGen (R8) | 333,887 | 2912 | 330,975 |

GM gut microbiota

Selection of Genetic Instrument

We selected single-nucleotide polymorphisms (SNPs) associated with gut microbiota with a relatively loose significance level (P < 1 × 10−5). Then, we applied chain disequilibrium r2 ≤ 0.1 within the distance of 500 kp, as a cutoff of linkage disequilibrium, for respective independence before being used as primary genetic instruments. Every paired combination was obtained for further analysis after coordinating with responsive outcomes. F statistic of IVs were calculated to identify bias from weak instrumental variables. F statistic > 10 was considered as no bias from weak instrumental variables.

Statistical Analysis

After harmonizing the SNPs in the data source with the same allele, we performed a two-sample MR analysis. The inverse variance weighting (IVW) method was used as the primary analysis of the causal relationship between gut microbiota and psoriasis. Odds ratios (ORs) of the exponential β for category outcomes and corresponding confidence intervals (CIs) were mainly applied to estimate the effect sizes of causality. P value < 0.05 was considered statically significant.

Then, to verify the consistency of our results and analyze sensitivity, MR-Egger, weighted median, MR-PRESSO (Mendelian Ran- 29 domization Pleiotropy RESidual Sum and Out- 30 lier), and leave-one-out analysis were performed. Potential pleiotropy was evaluated and corrected by MR-Egger intercept test and MR-PRESSO global test. Heterogeneity was assessed by Cochrane’s Q test calculated in the IVW method and MR-Egger method. Once potential pleiotropy or heterogeneity was identified, we would try to identify and remove outliers using MR-PRESSO; then the above analysis would be repeated. Finally, FDR correction was applied to reduce the possibility of false positives.

Results

Details of Selected Instrument Variables

As shown in Supplementary Material Table S1, after screening at a relatively loose threshold (P < 1 × 10−5) and LD clumping, SNPs of gut microbiota ranging from phylum to genus levels were applied. All the F statistics of the instrumental variables were over 10.

Causal Impact of Gut Microbiota on Psoriasis

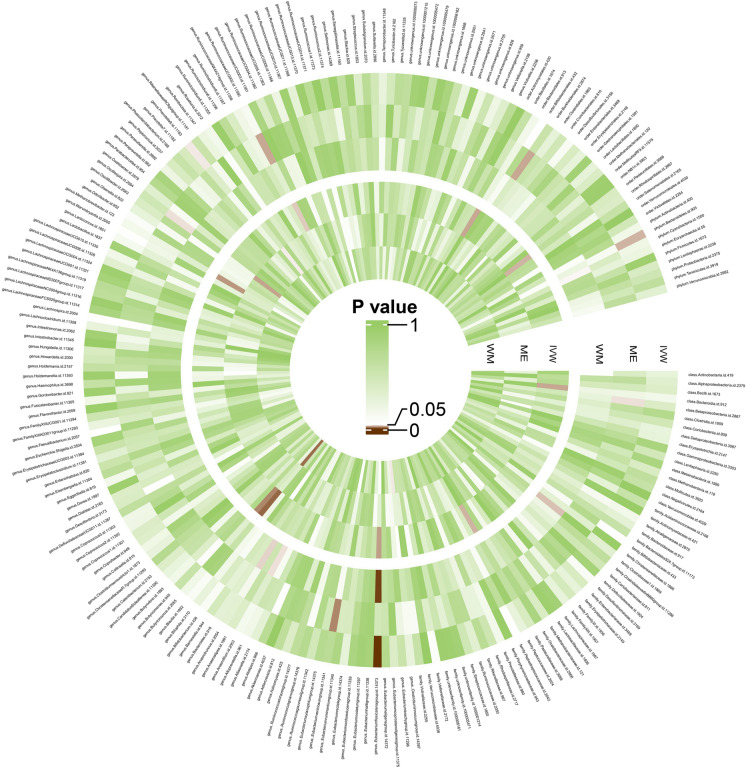

An overview of the causal effect of 211 gut microbiota taxa on psoriasis and PsA is shown in Fig. 2. More specifically, original statistical results are available in Supplementary Material Tables S2 and S3. The effect of each single SNP on psoriasis and arthropathic psoriasis is available in Supplementary Material Fig. S1.

Fig. 2.

Overview of the causal role of gut microbiota in psoriasis (outer section) and arthropathic psoriasis (inner section). The brown color indicates statistical significance (P < 0.05). IVW inverse variance weighted method, ME MR-Egger method, WM weighted median method

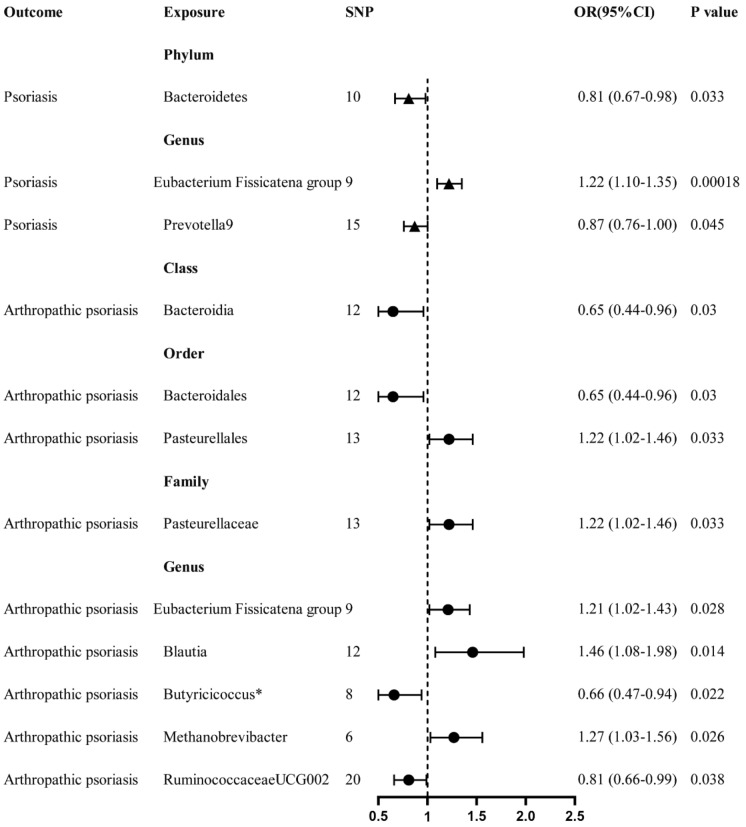

At the phylum level, we observed that Bacteroidetes has a nominally protective role in psoriasis (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.67–0.98, P = 0.033) by the primary IVW method. Then at the genus level, Prevotella9 also showed a nominally protective impact on psoriasis (OR 0.87, 95% CI 0.76–1.00, P = 0.045). On the other hand, Eubacterium fissicatena group is associated with an increased risk of developing psoriasis (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.10–1.35, P = 0.00018) (Fig. 3). Then after multiple-testing correction was performed (false discover rate [FDR] < 0.05, Supplementary Material Table S4), E. fissicatena group remains a significant risk factor for psoriasis (PFDR = 0.03798).

Fig. 3.

Forest plot of gut microbiota taxa associated with psoriasis or arthropathic psoriasis identified by the inverse variance weighted method. SNP single-nucleotide polymorphism, OR odds ratio, CI confidence interval. *Pleiotropy-corrected MR-Egger method showed no causal association between Butyricicoccus and arthropathic psoriasis

Causal Impact of Gut Microbiota on PsA

Then, we focused on the PsA subgroup. According to primary IVW analysis, class Bacteroidia (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.44–0.96, P = 0.03), order Bacteroidales (OR 0.65, 95% CI 0.44–0.96, P = 0.03), genus Ruminococcaceae UCG002 (OR 0.81, 95% CI 0.66–0.99, P = 0.038) are associated with a nominal lower risk for PsA (Fig. 3). Although genus Butyricicoccus also showed an association by IVW method (OR 0.66, 95% CI 0.47–0.94, P = 0.022), there is horizontal pleiotropy in IVs (Table 3, MR-Egger intercept, P = 0.048). MR-Egger method, which provides pleiotropy-corrected causal estimates [13], showed no causal association between Butyricicoccus and PsA (Table 2, OR 1.30, 95% CI 0.70–2.41, P = 0.44).

Table 3.

Sensitivity analysis of 12 taxa associated with psoriasis or arthropathic psoriasis

| Exposure | Outcome | SNPs | MR-Egger intercept | Cochrane’s Q IVW | Cochrane’s Q Egger | Presso Gable P | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Intercept value | P value | Q value | P value | Q value | P value | ||||

| Phylum | |||||||||

| Bacteroidetes | Psoriasis | 10 | 0.012494926 | 0.4560901 | 7.892532 | 0.545012 | 7.279194075 | 0.506831161 | 0.6 |

| Genus | |||||||||

| Eubacterium fissicatena group | Psoriasis | 9 | 0.052530524 | 0.1803491 | 6.172651 | 0.627899 | 3.958467739 | 0.784548513 | 0.71 |

| Prevotella9 | Psoriasis | 15 | 0.005113565 | 0.8050901 | 19.94096 | 0.132014 | 19.84413741 | 0.099165384 | 0.12 |

| Class | |||||||||

| Bacteroidia | Psoriasis | 12 | − 0.031146761 | 0.3438256 | 18.08594 | 0.079608 | 16.46069013 | 0.087182309 | 0.11 |

| Order | |||||||||

| Bacteroidales | PsA | 12 | − 0.031146761 | 0.3438256 | 18.08594 | 0.079608 | 16.46069013 | 0.087182309 | 0.15 |

| Pasteurellales | PsA | 13 | 0.026874918 | 0.2730482 | 12.2673 | 0.424458 | 10.93611813 | 0.448630555 | 0.46 |

| Family | |||||||||

| Pasteurellaceae | PsA | 13 | 0.026874918 | 0.2730482 | 12.2673 | 0.424458 | 10.93611813 | 0.448630555 | 0.45 |

| Genus | |||||||||

| Eubacterium fissicatena group | PsA | 9 | 0.085266114 | 0.1864937 | 6.318046 | 0.611653 | 4.173526271 | 0.759587767 | 0.63 |

| Blautia | PsA | 12 | 0.00083935 | 0.9764953 | 8.588019 | 0.659861 | 8.587106829 | 0.571684409 | 0.68 |

| Butyricicoccusa | PsA | 8 | − 0.067010589 | 0.0481149 | 8.641218 | 0.279451 | 2.514420145 | 0.866850344 | 0.27 |

| Methanobrevibacter | PsA | 6 | − 0.022446721 | 0.7121411 | 1.925832 | 0.859309 | 1.768808465 | 0.778183813 | 0.86 |

| Ruminococcaceae UCG002 | PsA | 20 | 0.007469164 | 0.7246516 | 17.2654 | 0.571893 | 17.13737163 | 0.513680071 | 0.54 |

SNPs single-nucleotide polymorphism, IVW inverse-variance weighted, PsA arthropathic psoriasis, MR Mendelian randomization

aWith pleiotropy present, the MR-Egger method, which provides pleiotropy-corrected causal estimates, should be considered as primary estimate of the causal association between Butyricicoccus and PsA

Table 2.

Results of MR analyses in nominal significance level (IVW P < 0.05)

| Exposure | Outcome | Method | SNPs | OR (95% CI) | P value |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Phylum | |||||

| Bacteroidetes | Psoriasis | IVW | 10 | 0.81 (0.67–0.98) | 0.033 |

| MR-Egger | 10 | 0.70 (0.45–1.07) | 0.13 | ||

| Weighted median | 10 | 0.86 (0.66–1.11) | 0.24 | ||

| Genus | |||||

| Eubacterium fissicatena group | Psoriasis | IVW | 9 | 1.22 (1.10–1.35) | 0.00018 |

| MR-Egger | 9 | 0.82 (0.48–1.40) | 0.48 | ||

| Weighted median | 9 | 1.23 (1.07–1.42) | 0.0036 | ||

| Prevotella9 | Psoriasis | IVW | 15 | 0.87 (0.76–1.00) | 0.045 |

| MR-Egger | 15 | 0.83 (0.55–1.24) | 0.38 | ||

| Weighted median | 15 | 0.89 (0.75–1.05) | 0.15 | ||

| Class | |||||

| Bacteroidia | Arthropathic psoriasis | IVW | 12 | 0.65 (0.44–0.96) | 0.03 |

| MR-Egger | 12 | 0.98 (0.40–2.39) | 0.97 | ||

| Weighted median | 12 | 0.79 (0.51–1.22) | 0.29 | ||

| Order | |||||

| Bacteroidales | Arthropathic psoriasis | IVW | 12 | 0.65 (0.44–0.96) | 0.03 |

| MR-Egger | 12 | 0.98 (0.40–2.39) | 0.97 | ||

| Weighted median | 12 | 0.79 (0.51–1.23) | 0.29 | ||

| Pasteurellales | Arthropathic psoriasis | IVW | 13 | 1.22 (1.02–1.46) | 0.033 |

| MR-Egger | 13 | 1.00 (0.68–1.47) | 0.99 | ||

| Weighted median | 13 | 1.07 (0.83–1.38) | 0.59 | ||

| Family | |||||

| Pasteurellaceae | Arthropathic psoriasis | IVW | 13 | 1.22 (1.02–1.46) | 0.033 |

| MR-Egger | 13 | 1.00 (0.68–1.47) | 0.99 | ||

| Weighted median | 13 | 1.07 (0.83–1.38) | 0.59 | ||

| Genus | |||||

| Eubacterium fissicatena group | Arthropathic psoriasis | IVW | 9 | 1.21 (1.02–1.43) | 0.028 |

| MR-Egger | 9 | 0.63 (0.26–1.53) | 0.34 | ||

| Weighted median | 9 | 1.22 (0.97–1.54) | 0.09 | ||

| Blautia | Arthropathic psoriasis | IVW | 12 | 1.46 (1.08–1.98) | 0.014 |

| MR-Egger | 12 | 1.45 (0.66–3.15) | 0.37 | ||

| Weighted median | 12 | 1.64 (1.10–2.46) | 0.016 | ||

| Butyricicoccusa | Arthropathic psoriasis | IVW | 8 | 0.66 (0.47–0.94) | 0.022 |

| MR-Egger | 8 | 1.30 (0.70–2.41) | 0.44 | ||

| Weighted median | 8 | 0.77 (0.49–1.20) | 0.25 | ||

| Methanobrevibacter | Arthropathic psoriasis | IVW | 6 | 1.27 (1.03–1.56) | 0.026 |

| MR-Egger | 6 | 1.47 (0.68–3.20) | 0.38 | ||

| Weighted median | 6 | 1.29 (0.99–1.67) | 0.06 | ||

| Ruminococcaceae UCG002 | Arthropathic psoriasis | IVW | 20 | 0.81 (0.66–0.99) | 0.038 |

| MR-Egger | 20 | 0.74 (0.43–1.25) | 0.27 | ||

| Weighted median | 20 | 0.89 (0.67–1.18) | 0.4 | ||

SNPs single-nucleotide polymorphism, OR odds ratio, IVW inverse-variance weighted, CI confidence interval, MR Mendelian randomization

aWith pleiotropy present, the MR-Egger method, which provides pleiotropy-corrected causal estimates, should be considered as the primary estimate of the causal association between Butyricicoccus and PsA (arthropathic psoriasis)

On the other hand, order Pasteurellales (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.02–1.46, P = 0.033), family Pasteurellaceae (OR 1.22, 95% CI 1.02–1.46, P = 0.033), genus Blautia (OR 1.46, 95% CI 1.08–1.98, P = 0.014), genus Methanobrevibacter (OR 1.27, 95% CI 1.03–1.56, P = 0.026), and genus E. fissicatena group (OR 1.21, 95% CI 1.02–1.43, P = 0.028) are nominally associated with increased risks of developing PsA (Fig. 3). After FDR correction (Supplementary Material Table S5), none of gut microbes showed any significant causal associations with PsA.

Sensitivity Analysis

In validating these causal associations identified by the IVW method, we observed inconsistent direction by the MR-Egger method of E. fissicatena group and Butyricicoccus (Table 2, Supplementary Material Fig. S4). This would theoretically be refined by either removing outliers or narrowing the genome-wide significance threshold, then selecting IVs more strictly for reanalysis [14]. But this process was not practical here with such a limited number of SNPs left, and there were no outliers identified by MR-PRESSO or funnel plot (Supplementary Material Fig. S2). With no horizontal pleiotropy or outliers observed, the IVW method should still be considered the primary result for evaluating the causal association of E. fissicatena.

All possible causal associations identified by the IVW method showed no significant heterogeneity by Cochrane’s Q test. Leave-one-out analysis confirmed the results were not driven by a single SNP (Supplementary Material Fig. S3). Most IVs for gut microbiota showed no horizontal pleiotropy except for Butyricicoccus (Table 3). Pleiotropy-corrected MR-Egger method was therefore considered the more appropriate method for estimating the causal association [13] between Butyricicoccus and PsA. Hopefully, when GWAS datasets of the gut microbiota with more participants and SNPs are made publicly available in the future, we can further validate these associations.

Discussion

In this study, we comprehensively evaluated the causal effect of 211 GM taxa (from phylum to genus level) on psoriasis and PsA, with the merit of large-scale GWAS summary statistics. Generally, we identified several gut microbes nominally associated with psoriasis and arthropathic psoriasis. After FDR correction, E. fissicatena group remains a risk factor for psoriasis. Hopefully, these identified gut microbiota biomarkers may be of benefit to the understanding of psoriasis pathology and offer promising therapeutic recommendations.

Firstly, we identified the nominal protective role of Bacteroidetes and Prevotella9 in psoriasis risks, as well as Bacteroidia, Bacteroidales, and Ruminococcaceae UCG002 which are nominally associated with lower risks for PsA. Notably, four out of these six protective GMs identified are from Bacteroidetes phylum (including Bacteroidetes, Bacteroidia, Bacteroidales, Prevotella9); these four gut microbes could produce short-chain fatty acids (SCFAs). Consistent with our results, previous clinical research has also reported that patients with psoriasis and PsA showed a decrease in SCFAs [15] and SCFA-producing bacteria, such as Bacteroidetes [16] and Prevotella [16].

SCFAs, including butyrate, propionate, etc., are the main metabolites from gut microbial fermentation of dietary fiber [17]. SCFAs show anti-inflammatory characteristics [7] by reducing the proliferation of various immune cells, and pro-inflammatory cytokine production, such as Th17, Treg, and DCs [18]. Additionally, SCFAs also upregulate Treg cells, transforming growth factor (TGF)-β, etc. [19], which are responsible for keeping inflammatory and immune reactions in line. Considering the inflammatory nature of psoriasis, these immune regulation SCFAs are critical for controlling psoriasiform inflammation [20]. More specifically, butyrate is an inhibitor of histone deacetylase (HDAC) and induces Foxp3 enhancer. Then with the expression of Foxp3, naïve CD4+ T cells are induced to differentiate into peripheral-derived Treg (pTreg) cells, protecting the host from inflammation [19, 21]. Further, in patients with psoriasis, SCFA metabolism genes are significantly downregulated [22]. In consideration of these pathways, SCFAs and SCFAs-producing microbes should be further studied as therapeutic targets for psoriasis. On the other hand, other bacterial metabolites such as trimethylamine N-oxide (TMAO) have been widely recognized for their pro-inflammatory effect. TMAO could cause M1 polarization and Th1 and Th17 differentiation [23]. TMAO was also reported to be elevated in patients with psoriasis [24]. However, considering the complexity of gut microbiota, there is indeed inconsistency between our results and existing evidence. For instance, previous research reported the Ruminococcaceae family, Coprococcus_1 genus [25], was decreased with psoriasis improvement. Prevotella was reported to be higher in those with psoriasis compared to the control group [26] and may be associated with psoriasis improvements in mice. Therefore, with these potential therapeutic targets provided in this study, future studies are also in need to develop personalized, evidence-based treatment protocols for patients with psoriasis.

On the other hand, Pasteurellales, Pasteurellaceae, Blautia, Methanobrevibacter, and E. fissicatena group are nominal risk factors for PsA, while E. fissicatena group is a risk factor for psoriasis after FDR correction. Consistent with our results, several clinical research studies reported that Blautia genus increased in psoriasis [25, 27, 28], and decreased as psoriasis improved [25]. Whereas, to the best of our knowledge, there has not been previous research on the association between E. fissicatena group and psoriasis. Although the detailed mechanism of GMs on psoriasis is not fully understood yet, there are a few theories. Firstly, the interleukin (IL)-23/Th17 axis, tumor necrosis factor (TNFα), etc. [29] have been recognized as significant biomarkers in the mechanism of irregular upregulation of inflammation in psoriasis. While gut microbiota plays a critical role in immune response, gut microbiota alterations were reported to be associated with alteration in Th17 cells [29, 30]. Additionally, as mentioned previously, gut microbiota-related metabolites, especially SCFAs, are essential for regulating immune hemostasis [31]. Whereas, gut dysbiosis and inflammatory gut may lead to lower production of SCFAs [32], and therefore increase psoriasis risks.

This study is the first of its kind, comprehensively analyzing the causal association of 211 GM taxa and psoriasis via Mendelian randomization approach. This method could significantly mitigate the potential effects of reverse causation and residual confounding factors. However, there are several limitations in this present study that should be disclosed. Firstly, in screening IVs for gut microbiota, we noticed extremely minimal IVs fulfilled P < 5 × 10−8, thus we finally applied a relatively loose threshold (P < 1 × 10−5). In addition, this study included individuals mainly of European ancestry, which may undermine the applicability of our results to citizens from other regions. Meanwhile, the GWAS dataset for gut microbiota applied in this study was confined from phylum to genus level, with several microbes without specific names. Future analysis based on large-scale studies is needed to evaluate the species level. Further, with an extremely limited number of SNPs left, and no specific outliers identified by MR-PRESSO, we were unable to address inconsistent direction by the MR-Egger method. There could be also a number of known or unidentified factors influencing both microbiota on the host and possible psoriasis risk. These limitations all make it difficult to determine the causal relationship between gut microbiota and psoriasis at this time. Hopefully, when GWAS dataset of gut microbes with more participants and SNPs is made publicly available in the future, further studies can validate these associations.

Conclusion

Several gut microbes are nominally associated with psoriasis and arthropathic psoriasis. Our results offer promising therapeutic targets for psoriasis clinical management. Further studies are needed to validate these associations between gut microbiota and psoriasis.

Supplementary Information

Below is the link to the electronic supplementary material.

Acknowledgements

We appreciate the MiBioGen and FinnGen studies for providing GWAS datasets.

Author Contribution

Study design: Chenyang Zang; data collection: Chenyang Zang, Jie Liu; data analysis: Chenyang Zang; writing: Chenyang Zang, Wangqing Chen, Manyun Mao; revision: Baojian Wei, Chenyang Zang; funding: Baojian Wei, Wangqing Chen, and Wu Zhu; administration: Baojian Wei, Wangqing Chen, and Wu Zhu.

Funding

This research was funded by The National Natural Science Foundation of China (Grant Nos. 81830096, 82221002, 81974479, 82173426) Research program of Medical and Health Science and Technology Development Plan Project of Shandong province (No. 202103070653). The Rapid Service Fee was funded by the authors and Health Science and Technology Development Plan Project of Shandong province (No. 202103070653).

Data Availability

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data is publicly available at https://mibiogen.gcc.rug.nl/, https://r8.finngen.fi/. The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.

Ethical Approval

This study was conducted on the basis of publicly available data from MiBioGen and FinnGen studies and was performed in accordance with the Helsinki Declaration of 1964 and its later amendments.. Ethical approval was granted for each of MiBioGen and FinnGen, and informed consent was obtained from all participants prior to participation. Patient personal information in the databases is unidentifiable.

Conflict of Interest

Chenyang Zang, Jie Liu, Manyun Mao, Wu Zhu, Wangqing Chen, Baojian Wei declare no conflict of interest.

Contributor Information

Wu Zhu, Email: zhuwu70@hotmail.com.

Wangqing Chen, Email: lanchen2008@163.com.

Baojian Wei, Email: bjwei@sdfmu.edu.cn.

References

- 1.Greb JE, Goldminz Am, Elder JT, et al. Psoriasis. Nat Rev Dis Primers. 2016;2:16082. doi: 10.1038/nrdp.2016.82. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.AlQassimi S, AlBrashdi S, Galadari H, Hashim MJ. Global burden of psoriasis - comparison of regional and global epidemiology, 1990 to 2017. Int J Dermatol. 2020;59(5):566–571. doi: 10.1111/ijd.14864. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Thye AY, Bah YR, Law JW, et al. Gut-Skin Axis: Unravelling the Connection between the Gut Microbiome and Psoriasis. Biomedicines. 2022;10(5). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 4.Mahmud MR, Akter S, Tamanna SK, et al. Impact of gut microbiome on skin health: gut-skin axis observed through the lenses of therapeutics and skin diseases. Gut Microbes. 2022;14(1):2096995. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2022.2096995. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Cresci GA, Bawden E. Gut microbiome: what we do and don’t know. Nutr Clin Pract. 2015;30(6):734–746. doi: 10.1177/0884533615609899. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.De Pessemier B, Grine L, Debaere M, et al. Gut-Skin Axis: Current Knowledge of the Interrelationship between Microbial Dysbiosis and Skin Conditions. Microorganisms. 2021;9(2). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 7.Buhaş MC, Gavrilaş LI, Candrea R, et al. Gut Microbiota in Psoriasis. Nutrients. 2022;14(14). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Tan L, Zhao S, Zhu W, et al. The Akkermansia muciniphila is a gut microbiota signature in psoriasis. Exp Dermatol. 2018;27(2):144–149. doi: 10.1111/exd.13463. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hidalgo-Cantabrana C, Gómez J, Delgado S, et al. Gut microbiota dysbiosis in a cohort of patients with psoriasis. Br J Dermatol. 2019;181(6):1287–1295. doi: 10.1111/bjd.17931. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Shapiro J, Cohen NA, Shalev V, et al. Psoriatic patients have a distinct structural and functional fecal microbiota compared with controls. J Dermatol. 2019;46(7):595–603. doi: 10.1111/1346-8138.14933. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Pierce BL, Burgess S. Efficient design for Mendelian randomization studies: subsample and 2-sample instrumental variable estimators. Am J Epidemiol. 2013;178(7):1177–84. doi: 10.1093/aje/kwt084. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kurilshikov A, Medina-Gomez C, Bacigalupe R, et al. Large-scale association analyses identify host factors influencing human gut microbiome composition. Nat Genet. 2021;53(2):156–165. doi: 10.1038/s41588-020-00763-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Burgess S, Thompson SG. Interpreting findings from Mendelian randomization using the MR-Egger method. Eur J Epidemiol. 2017;32(5):377–389. doi: 10.1007/s10654-017-0255-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Luo M, Cai J, Luo S, et al. Causal effects of gut microbiota on the risk of chronic kidney disease: a Mendelian randomization study. Front Cell Infect Microbiol. 2023;13:1142140. doi: 10.3389/fcimb.2023.1142140. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Khyshiktuev BS, Karavaeva TM, Fal'ko EV. Variability of quantitative changes in short-chain fatty acids in serum and epidermis in psoriasis. Klin Lab Diagn. 2008;8:22–4. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Olejniczak-Staruch I, Ciążyńska M, Sobolewska-Sztychny D, et al. Alterations of the skin and gut microbiome in psoriasis and psoriatic arthritis. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22(8). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 17.Koh A, De Vadder F, Kovatcheva-Datchary P, Bäckhed F. From dietary fiber to host physiology: short-chain fatty acids as key bacterial metabolites. Cell. 2016;165(6):1332–1345. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2016.05.041. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Vinolo MA, Rodrigues HG, Nachbar RT, Curi R. Regulation of inflammation by short chain fatty acids. Nutrients. 2011;3(10):858–76. doi: 10.3390/nu3100858. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Martin-Gallausiaux C, Béguet-Crespel F, Marinelli L, et al. Butyrate produced by gut commensal bacteria activates TGF-beta1 expression through the transcription factor SP1 in human intestinal epithelial cells. Sci Rep. 2018;8(1):9742. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-28048-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Stockenhuber K, Hegazy AN, West NR, et al. Foxp3(+) T reg cells control psoriasiform inflammation by restraining an IFN-I-driven CD8(+) T cell response. J Exp Med. 2018;215(8):1987–1998. doi: 10.1084/jem.20172094. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Chriett S, Dąbek A, Wojtala M, et al. Prominent action of butyrate over β-hydroxybutyrate as histone deacetylase inhibitor, transcriptional modulator and anti-inflammatory molecule. Sci Rep. 2019;9(1):742. doi: 10.1038/s41598-018-36941-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Ahn R, Gupta R, Lai K, et al. Network analysis of psoriasis reveals biological pathways and roles for coding and long non-coding RNAs. BMC Genomics. 2016;17(1):841. doi: 10.1186/s12864-016-3188-y. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Wu K, Yuan Y, Yu H, et al. The gut microbial metabolite trimethylamine N-oxide aggravates GVHD by inducing M1 macrophage polarization in mice. Blood. 2020;136(4):501–515. doi: 10.1182/blood.2019003990. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Sun L, Guo X, Qin Y, et al. Serum intestinal metabolites are raised in patients with psoriasis and metabolic syndrome. Clin Cosmet Investig Dermatol. 2022;15:879–886. doi: 10.2147/CCID.S351984. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Sun C, Chen L, Yang H, et al. Involvement of gut microbiota in the development of psoriasis vulgaris. Front Nutr. 2021;8:761978. doi: 10.3389/fnut.2021.761978. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Schade L, Mesa D, Faria AR, et al. The gut microbiota profile in psoriasis: a Brazilian case-control study. Lett Appl Microbiol. 2022;74(4):498–504. doi: 10.1111/lam.13630. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Choy CT, Chan UK, Siu PLK, et al. A novel E3 probiotics formula restored gut dysbiosis and remodelled gut microbial network and microbiome dysbiosis index (MDI) in Southern Chinese Adult Psoriasis Patients. Int J Mol Sci. 2023; 24(7). [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 28.Dei-Cas I, Giliberto F, Luce L, Dopazo H, Penas-Steinhardt A. Metagenomic analysis of gut microbiota in non-treated plaque psoriasis patients stratified by disease severity: development of a new Psoriasis-Microbiome Index. Sci Rep. 2020;10(1):12754. doi: 10.1038/s41598-020-69537-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.de Alcantara CC, Reiche EMV, Simão ANC. Cytokines in psoriasis. Adv Clin Chem. 2021;100:171–204. doi: 10.1016/bs.acc.2020.04.004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Guo M, Liu H, Yu Y, et al. Lactobacillus rhamnosus GG ameliorates osteoporosis in ovariectomized rats by regulating the Th17/Treg balance and gut microbiota structure. Gut Microbes. 2023;15(1):2190304. doi: 10.1080/19490976.2023.2190304. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Ney LM, Wipplinger M, Grossmann M, et al. Short chain fatty acids: key regulators of the local and systemic immune response in inflammatory diseases and infections. Open Biol. 2023;13(3):230014. doi: 10.1098/rsob.230014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Liu L, Li Q, Yang Y, Guo A. Biological function of short-chain fatty acids and its regulation on intestinal health of poultry. Front Vet Sci. 2021;8:736739. doi: 10.3389/fvets.2021.736739. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

Publicly available datasets were analyzed in this study. This data is publicly available at https://mibiogen.gcc.rug.nl/, https://r8.finngen.fi/. The authors confirm that the data supporting the findings of this study are available within the article and its supplementary materials.