Abstract

Background

The identification of novel therapeutic strategies for metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) patients harbouring KRAS mutations represents an unmet clinical need. In this study, we aimed to clarify the role of p21-activated kinases (Paks) as therapeutic target for KRAS-mutated CRC.

Methods

Paks expression and activation levels were evaluated in a cohort of KRAS-WT or -mutated CRC patients by immunohistochemistry. The effects of Paks inhibition on tumour cell proliferation and signal transduction were assayed by RNAi and by the use of three pan-Paks inhibitors (PF-3758309, FRAX1036, GNE-2861), evaluating CRC cells, spheroids and tumour xenografts’ growth.

Results

Paks activation positively correlated with KRAS mutational status in both patients and cell lines. Moreover, genetic modulation or pharmacological inhibition of Paks led to a robust impairment of KRAS-mut CRC cell proliferation. However, Paks prolonged blockade induced a rapid tumour adaptation through the hyper-activation of the mTOR/p70S6K pathway. The addition of everolimus (mTOR inhibitor) prevented the growth of KRAS-mut CRC tumours in vitro and in vivo, reverting the adaptive tumour resistance to Paks targeting.

Conclusions

In conclusion, our results suggest the simultaneous blockade of mTOR and Pak pathways as a promising alternative therapeutic strategy for patients affected by KRAS-mut colorectal cancer.

Subject terms: Cancer therapeutic resistance, Targeted therapies, Colon cancer

Introduction

Targeting epidermal growth factor receptor (EGFR) with monoclonal antibodies panitumumab or cetuximab is the main treatment strategy for RAS wild-type (WT) metastatic colorectal cancer (mCRC) [1]. KRAS mutations occur in ~30–40% of mCRC and represent a common cause of intrinsic resistance to anti-EGFR strategies [2, 3]. Novel selective KRAS G12C covalent inhibitors have been recently developed, changing the perception of KRAS as an undruggable target [4]. However, these promising results are limited to a subset of patients, as the KRAS G12C mutation represents the most prevalent genomic driver event in NSCLC (25–30% of non–squamous-cell NSCLCs [5]), but it is not frequently detected in CRC. Hence, the identification of alternative targets could be crucial to overcome the oncogenic effect of RAS mutations in these patients.

Ras activity is critically dependent on the small GTPase RAC1. The major effectors of RAC1 are the p21-activated kinases (Paks), a family of six (Pak1-6) Ser/Thr protein kinases. Paks regulate several cellular processes such as transcription, cell migration, survival and proliferation by activating downstream substrates [6–9]. Several PAK family members, especially PAK1, PAK2 and PAK4, are frequently overexpressed in most of human cancer types [10] and have been shown to be implicated in oncogenic transformation. For instance, Pak1 enhances the Raf/Mek/Erk signalling pathway by phosphorylating Raf-1 at Ser-338 and Mek1 at Ser-298, ultimately promoting cell proliferation [11]. Pak4 controls cell proliferation, survival, invasion, metastasis, epithelial–mesenchymal transition, and drug resistance promoting overall cancer progression [12].

Hence, the study of mechanisms underpinning the activation of Paks, critical regulators of the RAS-induced signalling cascades, might provide a rationale for the development of therapeutic strategies for KRAS-mutated cancers.

Materials and methods

Cell lines and inhibitors

Colorectal cancer KRAS WT (SW48, HT29) and KRAS MUT (HCT116, SW480, LS174T, SW620, LoVo) cell lines were obtained from the American Type Culture Collection (ATCC, Manassas, VA, USA) and maintained in ATCC-recommended media supplemented with 10% FBS (Gibco, Waltham, MA, USA) and 1× antibiotic/antimycotic (Gibco). SW48 stable overexpressing RAS MUT: G12G/G12A/G12V/G13D cell lines were generated as described previously [13]. All experiments were performed <2 months after thawing early passage cells. Mycoplasma testing was conducted for each cell line before use. PF-3758309 was provided by Pfizer company. Everolimus, FRAX1036 and GNE-2861 were purchased from SelleckChem (Houston, TX, USA).

Immunohistochemistry analysis on cancer tumour tissue samples

A series of 118 colorectal cancer tumour tissue samples from surgical resections were collected at the Pathology Unit, University of Campania “L. Vanvitelli”. We retrospectively recorded pathological parameters, including tumour size (T), lymph node status (N), metastasis (M), stage, histological type, grade, and KRAS mutational status. All cases collected were adenocarcinomas. Among 118 cases selected, 73 were KRAS WT and 45 KRAS-mutated. Immunohistochemical (IHC) staining was carried out on colon tumour whole slides to evaluate the expression of Pak1 and Pak2 and Pak4 phosphorylated form. Paraffin slides of 0.4 μm thickness were analysed using the following antibodies: anti-phospho-Pak1 (Ser199/Ser204) rabbit polyclonal antibody MSDS Millipore Sigma – 09-258 (diluted: 1:100), anti-phospho-Pak2 (Ser20) rabbit polyclonal antibody Cell Signaling #2607 (diluted: 1:50) and anti-phospho-Pak4 (93.Ser 474) mouse monoclonal antibody Santa Cruz Biotechnology #sc135775 (diluted: 1:100).

IHC was performed using BOND Polymer Refine Detection (Leica Biosystem, Milan, Italy) as a fully automated assay on the BOND RX (Leica Biosystems), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. The BOND Polymer Refine Detection kit contains a peroxide block, post-primary, polymer reagent, 3,3′-diaminobenizidine tetrahydrochloride hydrate chromogen, and hematoxylin counterstain. Expressions of the biomarkers were evaluated semi-quantitatively based on the staining intensity and the number of immunoreactive cells. The IHC staining was scored as follows: no staining or weak staining in <10% of tumour cells, score 0; weak staining in >10% of tumour cells, score 1+; moderate staining in >10% of tumour cells, score 2+; strong staining in >10% of tumour cells, score 3+. A Pearson χ2 test was conducted using SPSS20.0 for Mac (SPSS Inc., Chicago, IL, USA) to determine the association of biomarkers expression and the clinical-pathological features.

MTT cell viability assay

CRC cells (2 × 104 per well) were seeded in 24-well plates and treated with increasing doses of PF309 for 72 h. The percentage of cell density was determined using 3-(4,5-dimethylthiazol-2-yl)-2,5-diphenyltetrazolium bromide (MTT) assay according to the manufacturer’s instructions.

Clonogenic assays

Cells (5 × 104/well) were seeded in triplicate in Gibco™ McCoy’s 5A (modified) medium 10% fetal bovine serum (FBS) (Thermo Fisher Scientific) in 6-well plates and treated with the indicated drugs. Media drugs were replenished every 3 days until control wells reached 70–80% confluency. Monolayers were then fixed and stained with 20% methanol/80% water/0.25% crystal violet for 20 min, washed with water, and dried. After that, the plates were scanned at Brother MFCL2710DW (Brother Industries, Nagoya, Aichi, Japan) at 300 dpi, stained cells were solubilized with 20% acid acetic solution and the absorbance was measured by spectrophotometric detection at 490 nm using a plate reader (GloMax® Discover Microplate Reader; Promega, Madison, MI, USA).

CRC spheroids assay

Cells were seeded in Ultra-Low attachment 96 plate (Corning, Inc., Corning, NY, USA), in quadruple assays, using 100 µL of 10% McCoy’s 5A -FBS for 48 h. 5 × 103 HCT116, HCT116-LONG TR or LoVo cells were seeded at least in quadruplicate and representative images were captured at InvitrogenTM EVOSTM FL imaging system (×20 magnification) (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA). Spheroids were treated for 72 h as detailed in the specific figure legends. Tumour spheroids growth was monitored at the inverted microscope, the area was quantified with the ImageJ 1.53 software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) and normalised to time 0 area.

RT-PCR, qPCR

RNA was isolated using TRIzol and 1 μg of RNA/sample was reverse-transcribed using SuperScript™ III Reverse Transcriptase (Invitrogen), according to the manufacturer’s instructions. Quantitative PCRs (qPCR) were performed on the CFX Connect Real-Time PCR Detection System (Bio-Rad), using iTaq Universal SYBR Green Supermix (Bio-Rad). GAPDH gene was used as a reference for data normalisation and relative gene expression was measured with the 2−ΔΔCt method.

qPCR oligo PAIRS are listed as follows:

PAK1 gene: 5’-CCTGCACCGAAACCGAGTTA-3’ (Fwd) and

5’-TAGGAGTCCCACACAGGGTC-3’ (Rev).

PAK2 gene: 5’-CTCCTCCTGAGAAAGATGGCTT-3’ (Fwd) and

5’-AATAACGGGAGGAGCAGTCT-3’ (Rev).

PAK3 gene: 5’-CCAGGCTTCGCTCTATCTTCC-3’ (Fwd) and

5’ TCAAACCCCACATGAATCGTATG-3’ (Rev)

PAK4 gene: 5’-GCTCTTCAACGAGGTGGTAATC-3’ (Fwd) and

5’-AACTCCATGACCACCCAGAG-3’ (Rev).

PAK5 gene: 5′-CCAAAGCCTATGGTGGACCC-3′ (Fwd) and

5′-AGGCCGTTGATGGAGGTTTC-3′ (Rev)

PAK6 gene: 5’-GTGGGAACCCCCTACTGGAT-3’ (Fwd) and 5’-GTACGGTGGCTCCCCATCTA-3’ (Rev)

TSC1 gene 5’-CCAATGATGGAGCATGTGCG-3’ (Fwd) and

5’-GTGTCAGCATAAGGGCTGGT-3’ (Rev).

TSC2 gene 5’-ACACACCACTTCAACAGCCT-3’ (Fwd) and

5’-GAAGGATGACCAGAAGCCCC-3’ (Rev).

KRAS gene 5’-CTGGTGGCGTAGGCAAGAGT-3’ (Fwd) and

5’-CCTCTTGACCTGCTGTGTCG-3’ (Rev).

Western blot

Cells were lysed with radioimmunoprecipitation assay buffer lysis buffer (sc-24948, Santa Cruz Biotechnology, Inc., Dallas, TX, USA) according to the protocol supplied. Whole-cell lysates (30 µg) were separated by sodium dodecyl sulfate–polyacrylamide gel electrophoresis, transferred to nitrocellulose through Trans-Blot® Turbo™ RTA Mini Nitrocellulose Transfer Kit (Bio-Rad, Hercules, CA, USA). Membranes were subjected to immunoblot analyses using primary antibodies against Phospho-Pak1 (Ser144)/Pak2 (Ser141) (#2606, Cell Signaling), Phosphorylated Pak1 (Ser199/204) (#09-258 Sigma-Aldrich), Pak1 (#2602, Cell Signaling Technology), Phosphorylated Pak2 (Ser20) (#2607, Cell Signaling Technology), Pak2 (#2608, Cell Signaling Technology), Pak4 (ab62509, Abcam), GAPDH (6C5, sc32233, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Phosphorylated β-catenin (Ser675) (#9567, Cell Signaling Technology), β-catenin (sc7963, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Phospho-p44/42 MAPK (Erk1/2) (Thr202/Tyr204) (#9101, Cell Signaling Technology), ERK2 (sc1647, Santa Cruz Biotechnology), Phosphorylated AKT (Ser473) (#9271, Cell Signaling Technology) AKT (#9272S, Cell Signaling Technology), Phosphorylated p70 S6 kinase (Thr389) (#9234, Cell Signaling Technology), p70 S6 kinase (#9202 Cell Signaling Technology), Phosphorylated mTOR (Ser2448) (#2971, Cell Signaling Technology), mTOR (7C10, #2983, Cell Signaling Technology), β-Actin (13E5, #4970, Cell Signaling Technology), phosphorylated S6 Ribosomal Protein (Ser235/236) (#2211, Cell Signaling Technology), S6 Ribosomal Protein (54D2, #2317 Cell Signaling Technology). HRP-conjugated anti-rabbit and anti-mouse were used as secondary antibodies (Bio-Rad). Immunoreactive proteins were visualised by enhanced chemiluminescence using SuperSignal™ West Pico PLUS Chemiluminescent Substrate (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Waltham, MA, USA). Membranes were cut horizontally to probe with multiple antibodies. Films were imaged using Brother MFCL2710DW (Brother) at 300 dpi. Blots included in the figures are representative of three independent experiments. All blots derive from the same experiment and they were processed in parallel. Densitometric data analysis was performed by ImageJ 1.54d software (NIH, Bethesda, MD, USA) and displayed as mean values ± SD of different experiments. Intensity values were normalised on the expression signals of loading controls. Student’s t-test (two samples test; two-tailed) was used for assessing the statistical significance of differences.

Small interfering RNA (siRNA) transfections

Cells were transfected using Lipofectamine RNAi-MAX® (Invitrogen, Waltham, MA, USA) and 20 nM siRNA (Scrambled Negative Control, ON-TARGETplus Non-targeting Control siRNAs, DharmaconTM) or a SMART pool siRNA against PAK1, PAK2, PAK4 or KRAS mRNA (ON-TARGETplus siRNA, DharmaconTM) at 20 nM final concentration. After 2 days, cells were seeded in 10% McCoy’s 5A-FBS in 6-well plates (1 × 105/well for cell counting) or in 60-mm plates (for immunoblot analysis) and treated at the indicated drug concentrations for 24 h. For immunoblot analyses, cells were harvested and protein lysates prepared 3 days after transfection and 1 more day after drug treatment.

Xenograft studies

Six-week-old female Balb/c (nu+/nu+) mice (Charles River Laboratories, Milan, Italy) maintained in accordance with institutional guidelines of the University of Naples Animal Care Committee and in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki were injected subcutaneously into the right flank of each mouse with HCT116 (107 cells per mice) re-suspended in 200 μL of PBS/Matrigel matrix basement membrane (1:1) (Corning #356234). Five days after tumour cell injection, tumour-bearing mice were randomly assigned (8 per group) to receive: (1) vehicle; (2) PF-3758309 (25 mg/kg); (3) Everolimus (5 mg/kg); (4) PF-3758309 + everolimus; via orogastric gavage daily for 4 weeks for 10 days. Animal weights and tumour diameters (with calipers) were measured twice weekly and tumour volume in cm3 was calculated with the formula: volume = width2 × length/2. The researchers measuring animal weights and tumour volume were blinded to the group allocation. Mice were treated for 10 days and 4 h after the last dose of PF-3758309 ± everolimus; tumours were harvested and snap-frozen in liquid nitrogen before proceeding to total protein extraction for western blot analysis as described above.

Results

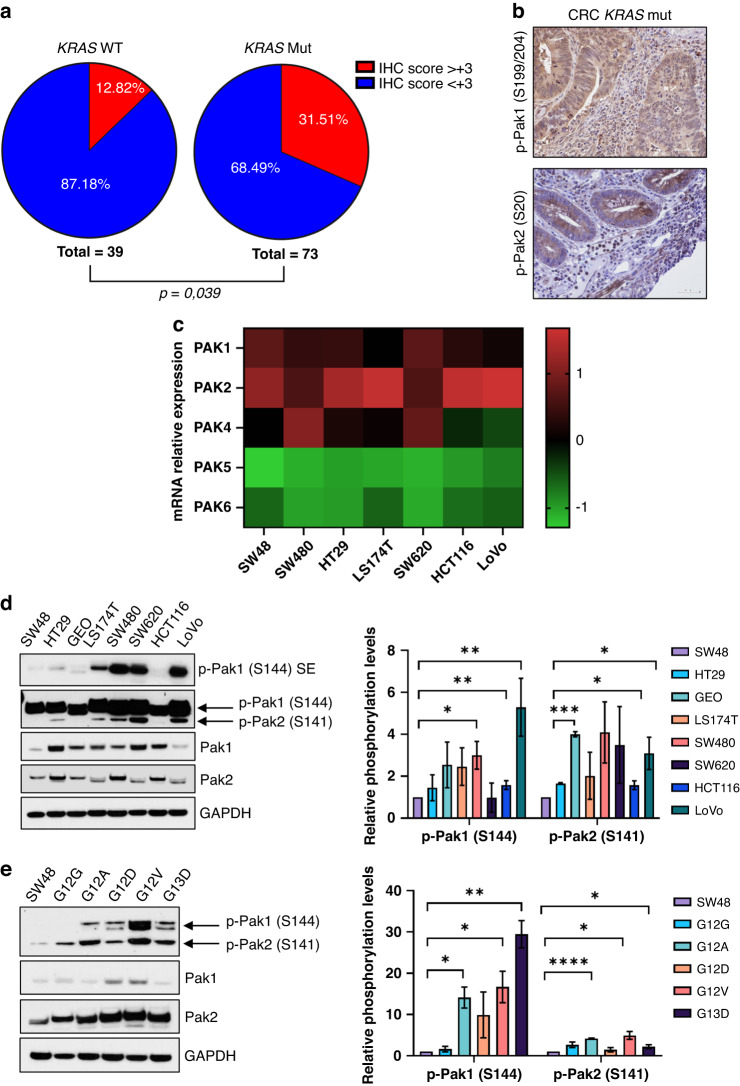

KRAS-mutated tumours and cells showed the hyper-activation of Paks compared to KRAS wild-type CRC models

We aimed to investigate expression levels of Pak kinases in CRC. First, we interrogated The Cancer Genome Atlas (TCGA) to assess the expression of each member of PAK family in CRC tumour samples. TCGA analysis showed that PAK1 (7%), PAK2 (9%), and PAK4 (7%) were the most expressed genes in patients with colorectal adenocarcinoma (PanCancer Atlas) (Supplementary Fig. 1a), although a similar percentage of biopsies showed low mRNA levels of PAK1 and PAK2. Next, we evaluated the levels of phosphorylated Pak1 (S199/204), -Pak2 (S20), -Pak4 (S474) in a cohort of 118 CRC tumour tissue samples by IHC. Clinical and pathological characteristics of CRC employed in the study were reported in Supplementary Tables S1 and S2. For KRAS WT cohort, 39/45 cases were evaluable. In the remaining six samples, the expression of both p-Pak1 and p-Pak2 could not be assessed and therefore they were not included in the analysis. Only two patients’ samples of the KRAS MUT cohort tested positive for p-Pak4 staining; no signal was detected in the KRAS WT samples, resulting in the least expressed Pak isoform in our cohort. For each staining, tumour samples were classified based according to the immunohistochemistry score (IHC score) (see Materials and Methods section). IHC score of CRC specimens employed in the study was reported in Supplementary Tables 1 and 2. p-Pak1 or p-Pak2 levels resulted significantly increased in KRAS-mutated versus KRAS WT CRC samples (p = 0.039) (Fig. 1a, b): 23/73 (31.51%) of CRC KRAS-mutated patients showed strong p-Pak1 or p-Pak2 staining (IHS > 3); Only 5/39 (12.8%) KRAS WT samples showed IHC score >3 for p-Pak1 and p-Pak2 (Supplementary Table 1). No statistically significant differences among the groups were found between biomarkers expression and clinicopathological features. Next, we evaluated by qPCR, mRNA expression levels of PAKs genes in a panel of human CRC cell lines, characterised by a different KRAS/NRAS mutational status. Data on the mutational status of CRC cells are reported in Supplementary Table 3. Consistent with data from CRC patients, PAK1, PAK2 and PAK4 were the top expressed members of the PAK family in CRC cells; no signal was detected for PAK3 (Fig. 1c).

Fig. 1. Expression and activation of p21-activated kinases in CRC patients and cell lines.

a Pie chart representing the percentage of samples included in the KRAS WT and KRAS-mutated CRC cohorts showing immunohistochemistry score (IHC score) >3 for p-Pak1 (Ser199/204) and p-Pak2 (Ser20) expression. b Representative immunohistochemical sections stained for p-Pak1 (upper panel) and p-Pak2 (lower panel) with IHC score >3 of KRAS-mut CRC patient sample (bar scale = 50 μM, ×40 magnification). c Heatmap of gene expression for PAKs in a panel of human CRC cell lines characterised by a different KRAS mutational status. The heatmap showed z-scores of differentially expressed genes of PAK family (PAK1-PAK6); up- and downregulated PAK genes are represented in red and green, respectively. Data show the mean of three independent experiments performed in triplicate. d Representative western blot analysis of Paks and p-Paks in KRAS WT (SW48, HT29) and KRAS-mutated CRC cell lines (GEO, LS174T, SW480, SW620, HCT116, LoVo) (left panel). GAPDH was used as a loading control. Images are representative of three independent experiments. Bar chart showing densitometric quantisation of the p-Pak1 (S144) and p-Pak2 (S141) performed using data from three independent experiments. Phosphorylation levels of Paks were compared to KRASwt SW48 ones (right panel). Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001; Student’s t-test). SE short exposed. e Western blot analysis of Paks and p-Paks in KRAS WT SW48 cell line stably transfected with plasmids carrying different KRAS mutations; GAPDH was used as a loading control. Images are representative of three independent experiments. Densitometric analysis of the p-Pak1 (S144) and p-Pak2 (S141) performed using data from three independent experiments is reported in bar chart (right panel). Phosphorylation levels of Paks were compared to KRASwt SW48 ones. Data are expressed as mean ± standard deviation (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; Student’s t-test).

Next, we sought to evaluate the putative association between KRAS mutational status and Paks/p-Paks levels in CRC cells. Western blot analysis did not reveal significantly different protein levels of Pak1 and Pak2, in KRAS WT (SW48 and HT29) compared to KRAS-mutated CRC cells (LS174T, GEO, SW480, SW620, HCT116, LoVo) (Fig. 1d), confirming qPCR results. However, p-Pak1 (S144) and p-Pak2 (S141) levels were higher in KRAS mut vs KRAS WT cells (Fig. 1d). These data were concordant with findings in CRC tissue samples shown in Fig. 1a and suggest an association between KRAS mutational status and Paks activation in CRC. To test this hypothesis, we assessed p-Paks’ levels in KRAS WT SW48 cells stable-overexpressing KRAS G12A/G/D/V or G13D mutations, previously generated in our laboratory [13] (Fig. 1e and Supplementary Fig. 1b). Overexpression of KRAS mutations induced a robust increase in Pak1 and Pak2 phosphorylation (Fig. 1e). Overall, our analyses clearly suggest a positive correlation between KRAS mutation and Paks activation in both CRC cells and patients’ samples.

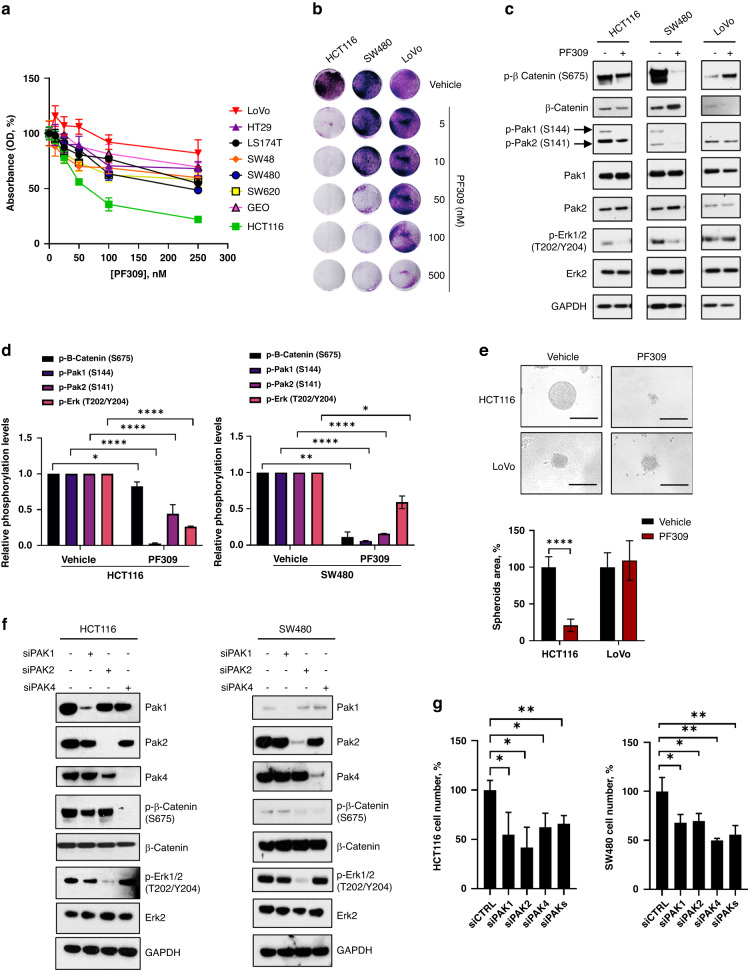

Pak inhibition exerts antiproliferative effect in KRAS mut CRC cells

To define the role of Paks activation on CRC cell growth, we evaluated cell proliferation and signal transduction upon Paks pharmacological inhibition or gene downregulation in CRC cell lines. The treatment with PF-3758309 (PF309), a strong ATP-competitive pan-Pak inhibitor, impaired cell proliferation of CRC cells to a different extent, as measured by MTT assay, with Ic50 ranging between 3 and 100 nM for HCT116, SW480, SW620, GEO and SW48, while, LoVo, HT29 and LS174T cells showed an Ic50 > 100 nM (Fig. 2a and Supplementary Table 4). In particular, KRAS-mutated HCT116, SW480 and LoVo cells showed respectively a high, intermediate and low sensitivity to PF309 (Fig. 2b). In addition, PF309 treatment significantly reduced Pak1 and Pak2 phosphorylation and the activation of key effectors of cell growth, such as p-β-catenin (S675) and p-Erk1/2 (T202/Y204), in sensitive HCT116 and SW480 cells (Fig. 2c, d). On the contrary, PF309 did not alter p-Erk1/2 and p-β-catenin levels in insensitive LoVo cells (Fig. 2c and Supplementary Fig. 1c). PF309 treatment prevented the formation of CRC tumour spheroids in HCT116 but not in LoVo cells. (Fig. 2e). SW480 cells were not reported as they were not able to form spheres in ultra-low attachment conditions.

Fig. 2. Effect of PAKs downregulation and pharmacological inhibition on cell proliferation and signalling activation in CRC cell lines.

a Percentage of cell survival of human CRC cell lines exposed to increasing doses of the Paks inhibitor PF-3758309 (PF309) ranging from 0 to 100 nM for 72 h, as measured by MTT assay. Data represent the mean (±SD) of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate. Cell survival of untreated cells was considered as 100%. b Representative crystal violet stained monolayers of HCT116, SW480 or LoVo CRC were grown in 12-well plates and treated with the indicated PF309 doses for 72 h. c HCT116, SW480 and LoVo cell lines were treated with 100 nM PF309 for 24 h. Representative western blot analysis of the major Paks transducers was performed on total cell lysates. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Images are representative of three independent experiments. d Bar chart reporting densitometric analysis of the indicated molecular species performed using data from three independent experiments. Data are reported as relative to vehicle-treated samples and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ****p < 0.0001; Student’s t-test) for HCT116 (left panel) and SW480 (right panel). e HCT116 and LoVo cells were grown in ultra-low attachment 96-well plates, to allow the formation of tumour spheroids. Spheroids were treated for 72 h with PF309 (50 nM) or vehicle (DMSO). Representative images of HCT116 and LoVo spheroids were captured at InvitrogenTM EVOSTM FL imaging system (bar scale = 200 μM, ×20 magnification) (upper panel). Per cent of spheroid area, quantified as described in Methods, of HCT116 and LoVo cells treated with PF309 or vehicle (DMSO). Spheroid area of cells treated with vehicle was considered as 100%. Data represent the mean (±SD) of three independent experiments, each performed in quadruplicate. Error bars indicate SD (****p < 0.001, Student’s t-test) (lower panel). f HCT116 (left panel) and SW480 (right panel) cells were transfected with siRNA for PAK1, PAK2 or PAK4, as described in Methods; siRNA scrambled was used as a control. Representative western blot analysis of the main Paks transducers performed 48 h after transfection on cell total lysates. GAPDH was used as loading control. Images are representative of three independent experiments. g HCT116 and SW480 cells were transfected with siRNA vs PAK1, PAK2 or PAK4 mRNA alone or in combination, as described in Methods; siRNA scrambled was used as a control (siCTRL). 72 h after PAKs knockdown per cent of cell number was determined by counting. Data represent the mean (±SD) of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, Student’s t-test).

To determine the contribution of each Pak to signal transduction, we analysed, by western blot, the expression of downstream Paks’ transducers in HCT116 and SW480 cells in response to PAK1, PAK2 or PAK4 knockdown. As shown in Fig. 2f, Erk1/2 activation was mainly modulated by Pak2, while β-catenin mainly by Pak4, resulting in a significant decrease of cell proliferation in both models upon each single PAK knockdown (Fig. 2f, g and Supplementary Fig. 1d, e). Of note, simultaneous inhibition of PAKs did not amplify the inhibitory effect on cell proliferation and signal transduction in both HCT116 and SW480 cell line (Fig. 2g and Supplementary Fig. 1f, g). Analogously, KRAS-mut-overexpressing SW48 cells resulted sensitive to nanomolar concentrations of PF309, both at 24 and 48 h of treatment (Supplementary Fig. 2a, b), resulting in a strong decrease of Pak2 phosphorylation and a concurrent blockade of both β-catenin and Mek1 pathways (Supplementary Fig. 2c). Moreover, PAKs knockdown led to a significant decrease in both p-β-catenin (S675) and p-Erk1/2 (T202/Y204) in SW48-KRAS-G13D (G13D) and SW48-KRAS-G12V (G12V) cells, as shown in HCT116 and SW480 harbouring the same KRAS mutations, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 2d).

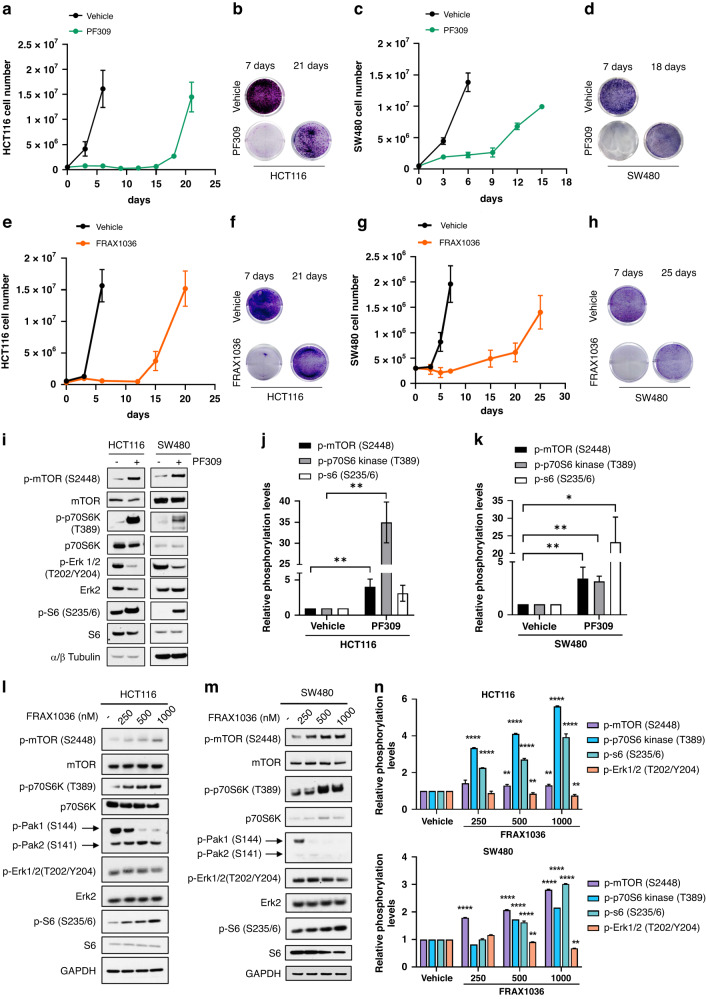

The hyper-activation of mTOR Complex 1 (mTORC1) pathway mediates CRC adaptation to Paks inhibition

Despite the efficacy of Paks targeting in the inhibition of tumour cell proliferation and mitogenic signalling pathway activation, the onset of a rapid tumour adaptation to a single agent is expected. Thus, we assessed the effect of long exposure to PF309 and FRAX1036, a selective pan-Paks inhibitor of Pak1 and Pak2, on HCT116 and SW480 cell proliferation. HCT116 and SW480 showed similar sensitivity to FRAX1036 compared to LoVo cells (Supplementary Fig. 3a–c), which on the contrary resulted insensitive to PF309. HCT116 or SW480 cells were treated with PF309 or FRAX1036 for various times spanning from 1 to 30 days. Growth curves showed that the single-agent PF309 or FRAX1036 induced a robust impairment of cell viability in both HCT116 and SW480 (Fig. 3a–h) only during the first days of treatment. Indeed, the continuous exposure to Paks inhibitors led to rapid tumour cell regrowth after 21 days for HCT116 cells (Fig. 3a, b, e, f) and after 18 days of treatment with PF309 (Fig. 3c, d) or 25 days after FRAX1036 exposure in SW480 cells (Fig. 3g, h). CRC cells exposed for 1 month to PF309 were denoted as long-treated (HCT116- and SW480-LONG TR). Dose-response curves showed that PF309 pre-treatment increased IC50 by 10 times in HCT116-LONG TR compared to sensitive HCT116 cells (~2 vs 20 nM for HCT116 and HCT116-LONG TR, Supplementary Fig. 4a). Similarly, SW480-LONG TR cells were able to grow also in the presence of high concentrations of PF309 (Supplementary Fig. 4b). Moreover, HCT116-LONG TR were able to form CRC spheroids also in the presence of Paks inhibitor, unlike untreated HCT116 (Supplementary Fig. 3c, d). To identify the molecular mechanism underneath the early tumour adaptation upon Paks inhibition, we explored the activation of the main key Ras-downstream transducers. We interestingly found, although Erk phosphorylation levels resulted decreased upon PF309 treatment in both KRAS-mut CRC cells, an early and robust increase in mTOR/p70 S6 kinase/S6 phosphorylation in both HCT116 and SW480 cell lines, even after 24 h of treatment with PF309 (Fig. 3i–k). Analysing long-term effects of PF309 exposure on signalling pathways’ activation, consistently, we observed that although p-Pak1, p-Pak2, p-Pak4 and p-Erk1/2 levels resulted downregulated upon long-term treatment with PF309 (Long TR), p-mTOR and downstream p-p70 S6 kinase levels were upregulated (Supplementary Fig. 3e, f), compared to CRC exposed for 24 h (Short TR) in both HCT116 and SW480.

Fig. 3. Prolonged exposure of HCT116 and SW480 CRC cells to Paks inhibitors led to a rapid tumor adaptation.

a 5 × 105 HCT116 cells were seeded in p100 cell culture dishes for 24 h and treated with DMSO (vehicle) or 100 nM PF309. Cell were counted at the Countess 3 Automated Cell Counter (InvitrogenTM) every 3 days until cellular confluence and reported in the line chart. Each data point represents the mean ± SD of the representative experiment conducted in triplicate. b 5 × 104 HCT116 cells were seeded in 6-well plate for 24 h and treated with DMSO (vehicle) or 50 nM PF309 for 7 or 21 days. Cells were fixed at the indicated time points and stained with a crystal violet solution and scanned at 300 dpi. c 5 × 105 SW480 cells were seeded, treated and counted as described in panel (a). d 5 × 104 SW480 cells were seeded, treated and stained with crystal violet solution as described in panel (b). e 5 × 105 HCT116 cells were seeded in p100 cell culture dishes for 24 h and treated with 4-methylpyridine (vehicle) or 1 μM FRAX1036. Cells were counted and reported in line charts as described in panel (a). f Representative crystal violet stained monolayers of HCT116 cells treated with 4-methylpyridine (vehicle) or 1 μM FRAX1036 for 7 or 21 days. g 3 × 105 SW480 cells were seeded, treated with 4-methylpyridine (vehicle) or 3 μM FRAX1036 and counted as described in panel (e). h 5 × 104 SW480 cells were seeded, treated and stained with DMSO (vehicle) or 3 μM FRAX1036 crystal violet solution as described in panel (f). i Representative western blot analysis of HCT116 or SW480 treated with vehicle (DMSO) or PF309 (100 nM) for 24 h. α/β Tubulin was used as a loading control. Images are representatives from three independent experiments. j Bar chart reporting densitometric analysis of the indicated molecular species performed using data from three independent experiments. Data are reported as relative to vehicle-treated samples and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, Student’s t-test) for HCT116 (j) and for SW480 (k). l Representative western blot analysis of HCT116 or m SW480 treated with vehicle or with the indicated doses of FRAX1036 for 48 h. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Images are representatives from three independent experiments. n Bar chart reporting densitometric analysis of the indicated molecular species performed using data from three independent experiments. Data are reported as relative to vehicle-treated samples and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (**p < 0.01; ****p < 0.0001, Student’s t-test) for HCT116 (upper panel) and SW480 (lower panel).

In like manner, the exposure to increasing doses of FRAX1036 for 48 h induced a significant increase in the phosphorylation levels of mTOR, p70 S6 kinase and S6, but only a partial effect on Erk1/2 phosphorylation (Fig. 3l–n), apparently due to a low to none effect on Pak2 phosphorylation even at 1 μM concentration, which resulted crucial for Erk1/2 blockade (Fig. 2f). Furthermore, we evaluated also the effects of GNE-2861, a highly selective inhibitor of Group II of the Paks family, on KRAS-mut CRC cell proliferation. HCT116 and SW480 resulted almost insensitive to the inhibition of Group II of Paks, with no effect on Erk1/2 phosphorylation even at μM concentrations both at 24 and 48 h (Supplementary Fig. 5a, b).

These results suggested a pivotal role of mTOR signalling in tumour adaptation to Paks inhibition.

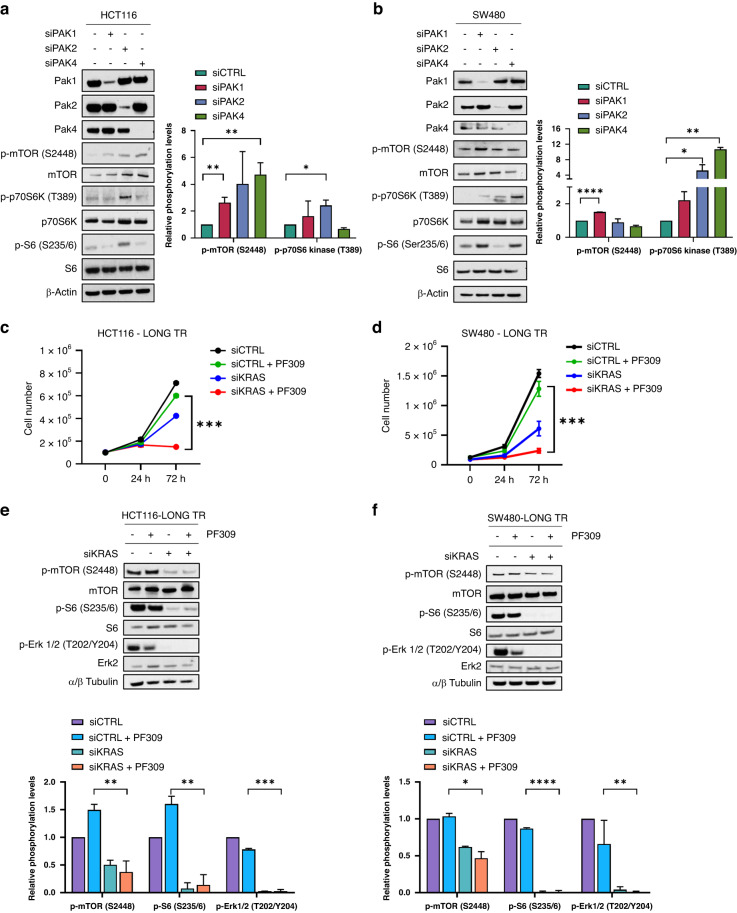

KRAS downregulation restores CRC sensitivity to Paks inhibitor PF309

To dissect the contribution of single Pak kinases’ blockade to mTOR kinase pathway activation, we transiently knocked down PAK1, PAK2 or PAK4 through RNAi in both HCT116 and SW480, in order to emulate PF309 and FRAX1036 pharmacological effects. mTOR phosphorylation increased after gene downregulation of both PAK1, PAK2 and PAK4 in parental HCT116, while mainly PAK2 knockdown seemed to have a marked effect on p70 S6 kinase/S6 phosphorylation (Fig. 4a). On the other hands, PAK1 knockdown significantly induced mTOR phosphorylation on S2448, while PAK2 and PAK4 resulted crucial for p70 S6 kinase activation in SW480 (Fig. 4b). To further dissect the mechanisms of mTOR activation upon Paks inhibition, we analysed TSC1 and TSC2 expression, members of tumour suppressor complex TSC1-2, known to modulate p-S6 activation through the negative regulation of TORC1 kinase function [14]. Both HCT116- and SW480-LONG TR showed a significant decrease in TSC1 and TSC2 expression upon 24 h of treatment with PF309 compared to HCT116 and SW480, respectively (Supplementary Fig. 6a, b), possibly explaining the hyper-activation of mTORC1 downstream mediators, S6, after Paks pharmacological long inhibition.

Fig. 4. Dissecting the effects of PAK1, 2 and 4 or KRAS knockdown on the mTOR pathway activation and cell proliferation.

a HCT116 or b SW480 cells were transfected with siRNA against PAK1, PAK2 or PAK4 as described in Methods; siRNA scrambled was used as a control. Representative western blot analysis of total cell lysates for the indicated antibodies was performed 48 h after transfection. Bar chart reporting densitometric analysis of p-mTOR (S2448) or p-p70 S6 Kinase (T389) performed using data from three independent experiments. Data are reported as relative to samples transfected with siCTRL and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, Student’s t-test) for HCT116 (a, right) and SW480 (b, right). c HCT116-LONG TR or d SW480-LONG TR cells were transfected with siRNA against KRAS. 24 h after gene knockdown, 1 × 105 cells were seeded in 6-well plate, counted after a further 24 h and treated with 100 nM PF309 for 72 h. Cell number was determined at the Countess 3 Automated Cell Counter (InvitrogenTM). Data represent the mean (±SD) of three independent experiments, each performed in triplicate (***p < 0.001; Student’s t-test). e HCT116-LONG TR or f SW480-LONG TR cells were transfected with siRNA vs KRAS mRNA for 48 h and treated for further 24 h with 100 nM PF309. siRNA scrambled was used as a control. Representative western blot analysis of total cell lysates for the indicated antibodies. Bar chart reporting densitometric analysis of the indicated molecular species performed using data from three independent experiments. Data are reported as relative to samples transfected with siCTRL and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (*p < 0.05; **p < 0.01, ***p < 0.001, ****p < 0.0001; Student’s t-test) for HCT116 (e, bottom) and SW480 (f, bottom).

Ras is a known mediator of mTOR phosphorylation through concurrent activation of PI3K and MAPK activation [15]. We wondered if KRAS knockdown was able to prevent PF309-dependent mTOR/S6 pathway activation in long exposed CRC cell lines and to restore cell sensitivity to Paks inhibitor. PF309 treatment strongly decreased cell proliferation of both HCT116- and SW480-LONG TR cells when KRAS was downregulated, therefore restoring sensitivity to the Pak inhibitor (Fig. 4c, d, respectively). Efficacy of KRAS RNAi was assessed by qPCR 24 h after transfection (Supplementary Fig. 6c). In accordance, western blot analysis showed that KRAS interference concurrently abrogated both Erk1/2 and mTOR/S6 activation in HCT116- and SW480-LONG TR cells (Fig. 4e, f), preventing PF309-dependent pathway activation. Consistently, KRAS knockdown also impaired cell proliferation of PF309-insensitive LoVo and GEO cell lines, concurrently inhibiting Erk1/2 and mTOR phosphorylation (Supplementary Fig. 6d–g). Thus, we hypothesised that in CRC KRAS mut, insensitive to EGFR target therapy, Paks inhibition through TSC1/2 downregulation induced mTOR/S6 pathway activation unless KRAS gene downregulation (Supplementary Fig. 6h), possibly through Erk-dependent TSC1-TSC2 phosphorylation [16].

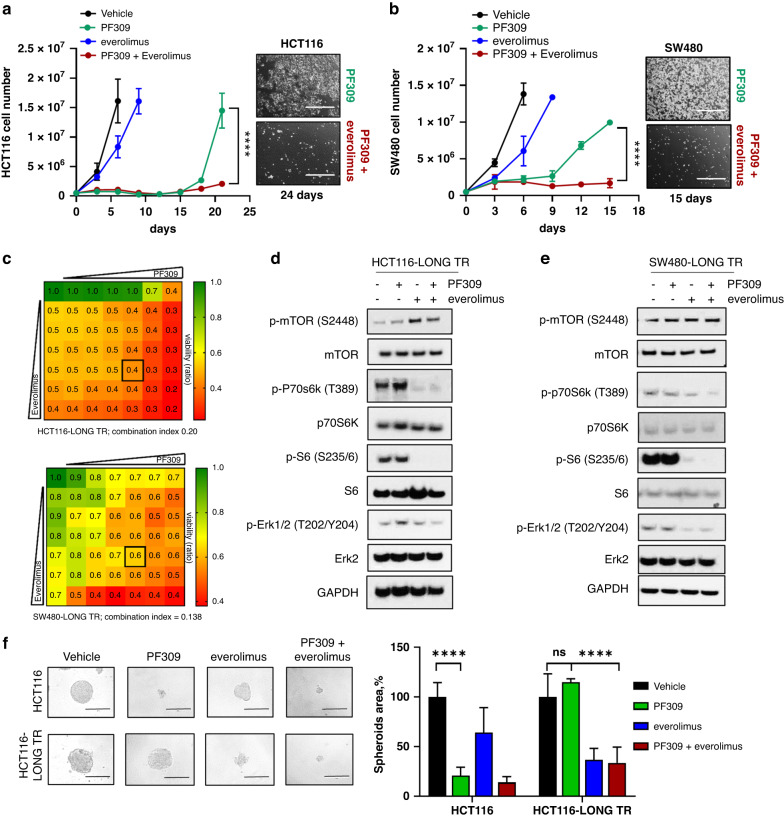

mTOR inhibitor everolimus reverts tumour adaptation to Paks inhibition, preventing CRC tumour growth

Finally, we wondered if mTOR inhibition, similar to KRAS downregulation, was able to prevent CRC tumour adaptation to Paks inhibition. Growth curves clearly showed that the addition of mTOR inhibitor, everolimus, to PF309 prevented the regrowth of both HCT116 and SW480, after 21 and 15 days, respectively (Fig. 5a, b). The single agent everolimus exerted almost no effect on HCT116 and SW480 cell proliferation (Fig. 5a, b). However, dose-response curves showed that the long treatment of HCT116 with PF309 sensitised CRC cells to everolimus (Supplementary Fig. 7a). Drug combination assays revealed a synergistic effect of PF309 and everolimus in HCT116-LONG TR and SW480-LONG TR (Fig. 5c, CI = 0.20 for HCT116-LONG TR, upper panel, and CI = 0.138 for SW480-LONG TR, lower panel). Western blot analysis showed that everolimus alone or in combination with PF309 induced a complete abrogation of p70 S6 kinase (T389) and S6 (S235/6) activation in both HCT116-LONG TR and SW480-LONG TR (Fig. 5d, e and Supplementary Fig. 7b, c). However, only the addition of PF309 induced a concurrent inhibition of Erk1/2 phosphorylation, suggesting that to prevent cell proliferation in KRAS-mut CRC cells pre-treated with PF309, it is necessary to act on both Pak-Erk and mTOR-p70 S6 kinase pathways (Fig. 5d and Supplementary Fig. 7b for HCT116-LONG TR and Fig. 5e and Supplementary Fig. 7c for SW480-LONG TR, respectively).

Fig. 5. Overcoming CRC tumour adaptation to PF309 through mTOR inhibition.

a 5 × 105 HCT116 cells were seeded in p100 cell culture dishes for 24 h and treated with vehicle (DMSO) 500 nM everolimus, 100 nM PF309 alone or in combination. Cells were counted at the Countess 3 Automated Cell Counter (InvitrogenTM) every 3 days until cellular confluence and reported in the line chart on the left. Each data point represents the mean ± SD of the representative experiment conducted in triplicate (****p < 0.0001; Student’s t-test). Representative images of HCT116 treated with PF309 alone or combined with everolimus 21 days after treatment are shown on the right. Images were captured at InvitrogenTM EVOSTM FL imaging system (×4 magnification, bars = 1000 µm). b 5 × 105 SW480 cells were seeded, treated, counted as described in panel (a) and reported in the line chart on the left. Each data point represents the mean ± SD of the representative experiment conducted in triplicate (****p < 0.0001; Student’s t-test). Representative images of SW480 treated with PF309 alone or combined with everolimus, 15 days after treatment are shown on the right (×4 magnification, bars = 1000 µm). c Viability assay to test synergy between PF309 and everolimus. HCT116-LONG TR (upper panel) or SW480-LONG TR (lower panel) cells were treated with increasing concentrations of PF309 and everolimus (up to 100 nM and 10 μM, respectively) alone or in combination every 72 h until vehicle-treated controls reached ∼90% of confluency. Intensity values of cell monolayers stained with crystal violet were used to perform the Chou–Talalay test. Numbers inside each box indicate the ratio of viable treated cells to untreated cells from three independent experiments. d Representative western blot analysis of HCT116-LONG TR or e SW480-LONG TR treated with vehicle, 100 nM PF309, 500 nM everolimus, alone or in combination for 24 h. GAPDH was used as a loading control. Images are representatives from three independent experiments. f Representative images of HCT116 and HCT116-LONG TR spheroids cultured in ultra-low attachment plates and treated with vehicle (DMSO) or PF309 10 or 500 nM everolimus alone or in combination every 72 h for 6 days. All images were captured at ×20 magnification (bars = 200 µm). Spheroids area is reported in the right panel; values are expressed as percentage relative to vehicle-treated spheroids. Data represent the mean (±SD) of three independent experiments, each performed in quadruplicate (****p < 0.001, two-way ANOVA Bonferroni’s multiple comparisons).

Exposure to PF309 abolished HCT116 spheroids growth, while did not prevent spheroid formation of HCT116-LONG TR (Fig. 5f). Furthermore, HCT116-LONG TR spheroids were more sensitive to everolimus compared to HCT116 (Fig. 5f). Only combination of PF309 + everolimus prevented HCT116-LONG TR spheroids growth (Fig. 5f), in accordance to cell growth curves showed in Fig. 5a. Concordantly, cell viability assays showed that only concomitant Pak and mTOR inhibition affected HCT116-LONG TR and SW480- LONG TR cell proliferation after 3, 6 and 9 days of treatment (Supplementary Fig. 7d–i).

Consistently, also FRAX1036-dependent activation of mTOR/p70 S6 kinase pathway was successfully prevented by everolimus treatment. Indeed, mTOR inhibitor was able to arrest both HCT116 and SW480 regrowth upon the prolonged exposure of CRC cells to FRAX1038 (Supplementary Fig. 8a, b). Drug combination assays revealed a synergistic effect of FRAX1036 and everolimus in HCT116 and SW480 (Supplementary Fig. 8c, d CI = 0.16 for HCT116, and CI = 0.43 for SW480). Furthermore, only the combined therapy of FRAX1036 and everolimus was able to prevent Erk1/2 and mTOR-p70 S6 kinase activation in both HCT116 and SW480 (Supplementary Fig. 8e, f), confirming the need to concurrently act on both signalling pathways to prevent KRAS-mut CRC growth.

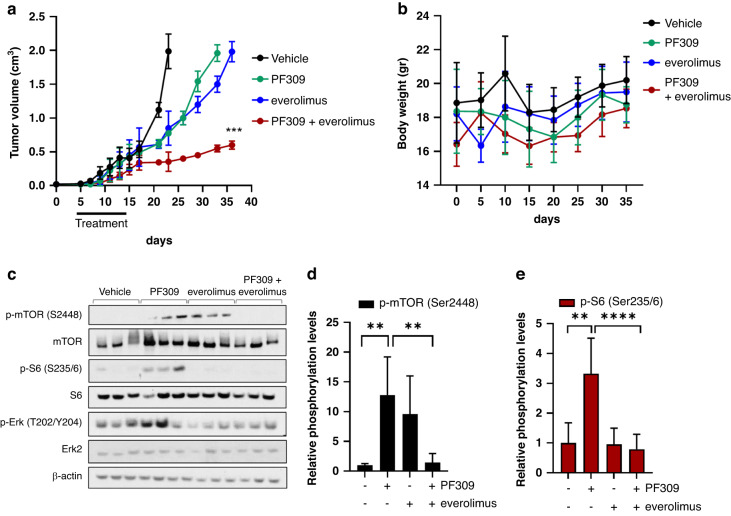

To test the efficacy of PF309 ± everolimus combination in vivo, we established xenografts of parental HCT116 cells in BALB/c nude mice (Fig. 6a). Pharmacological treatments started 5 days after cell inoculation, for 10 days with everolimus (5 mg/kg once a day via o.g.), or PF309 (17 mg/kg once a day via o.g.) or both. Tumour growth was monitored until volume reached an average of 2 cm3.

Fig. 6. The combination of mTOR and Paks’ pathway blockade prevents HCT116 xenografts growth.

a HCT116 xenografts were established in Balb/c nude mice. Five days after injection, mice were treated with vehicle, everolimus (5 mg/kg once a day via o.g.), or PF309 (17 mg/kg once a day via o.g.) or both for 10 days. Tumour growth curve is shown. Each data point represents the mean of tumour volume in cm3 ±SD (n = 8 per arm, ***p < 0.001 vs. PF309 drug arms; Student’s t-test). b Line chart showing mice body weight trend during the pharmacological treatment. Data are presented as means ± SD. c Representative western blot analysis of proteins extracted from three representative HCT116 tumour xenografts after 4 h of treatment and blotted for the indicated antibodies. d Bar chart reporting densitometric analysis of p-mTOR (Ser2448) or e p-S6 (Ser235/6) performed using data from three independent experiments. Data are reported as relative to vehicle-treated samples and expressed as mean ± standard deviation (n = 8, **p < 0.01; ****p < 0.001, Student’s t-test).

Only a combination of Paks and mTOR inhibitors significantly hampered the growth of HCT116 xenografts (Fig. 6a). Of note, drug combination did not affect body weight (Fig. 6b). In accordance with our previous evidence in vitro, PF309 induced a significant increase in p-mTOR and p-S6 levels (Fig. 6c–e), further supporting the hypothesis that mTOR signalling activation boosted cell proliferation despite PF309 treatment. The combination of PF309 and everolimus induced a concurrent downregulation of p-ERK, p-mTOR and p-S6 levels, supporting our in vitro findings.

Collectively, these data suggest that Pak inhibition, per se, is not sufficient to efficiently impair RAS-mut CRC growth, both in vitro and in vivo. However, the simultaneous blockade of mTOR is required.

Discussion

In the last years, molecular target therapy significantly impacted CRC patient prognosis, mostly in combination with chemotherapy, increasing cancer patient survival and preventing tumour progression and relapse. In particular, the introduction of monoclonal antibodies against EGFR, including cetuximab or panitumumab, significantly increased the overall survival of metastatic CRC patients. Unfortunately, not all patients benefit from anti-EGFR therapy. In the past decade, alternative strategies have been investigated but with very poor success.

Here, we demonstrated for the first time a significant positive correlation between KRAS mutations and Pak kinases activation in colorectal adenocarcinoma patients and cell lines. Pharmacological inhibition or gene downregulation of PAK1, PAK2 and PAK4 prevented CRC cell proliferation and survival. We identified the hyper-activation of mTOR/p70 S6 kinase/S6 pathway as an RAS-mediated escape mechanism from targeted Paks inhibition in KRAS-mutated CRC cells. Alteration of mTOR pathway was frequently observed in CRC: elevated mTOR mRNA and protein levels, as well as a strong correlation between a higher malignancy stage and higher expression level, were observed in CRC patient tissues [17, 18]. In our KRAS mut models of CRC, the addition of everolimus restores cell sensitivity to PF-3758309 and FRAX1036 both in vivo than in vitro, concurrently suppressing both Erk and S6 activation. We found that KRAS has a key role in mTOR/p70 S6 kinase/S6 pathway activation upon Pak/Erk pathway inhibition. Similar to the everolimus effect, KRAS knockdown prevents mTOR/p70 S6 kinase activation and cell proliferation of CRC cell lines treated with PF309, which rapidly developed drug tolerance to Pak inhibitors both in vitro than in vivo, suggesting RAS-dependent TORC1 hyperactivity. A similar mechanism was previously demonstrated in HER2-mutant breast cancer models with acquired resistance to neratinib, where RAS-mediated TORC1 aberrant activation was prevented by the addition of everolimus, as well as by RAS knockdown, restoring sensitivity to neratinib [19]. In addition, a rapid mechanism of mTORC1-dependent adaptive resistance was also observed after only 12 days in triple-negative breast cancer models, upon treatment with FGFR-1 inhibitor [20], in accordance with our findings of a rapid tumour cell growth after about 20 days of treatment with PF309 or FRAX1036.

Although pharmacokinetics and pharmacodynamics issues led to a premature interruption of Phase I clinical trial of escalating doses of PF-03758309 in patients with advanced solid tumours [NCT00932126], the need to block Pak activity seems to be crucial as an alternative strategy in RAS-mutated CRC patients [21, 22]. In the last years, the dual Pak4-NAMPT inhibitor KPT-9274 showed promising results in pancreatic, kidney cancers and haematological malignancies [23–25]. However, we showed that targeting Pak1 and Pak2 is crucial to prevent KRAS-mutated CRC growth and proliferative pathway activation.

In conclusion, based on our experimental evidence, we propose the combined molecular targeting of Pak kinases plus mTOR as a promising alternative therapeutic strategy in RAS-mutated CRC patients with poor prognosis and unresponsive to EGFR inhibitors.

Supplementary information

Author contributions

Conceptualisation: SB, AP, LF and RB. Methodology: SB, AP, LF and RB. Writing—original draft preparation: SB, AP, AS LF. Investigation: SB, AP, DE, AA, FZM. Writing—review and editing: SB, AP, AS, DE, PC, CMA, AA, NZ, FZM, RF, TT, LF and RB. Supervision: LF and RB. Funding acquisition: AS, LF and RB. All authors have read and agreed to the published version of the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by AIRC IG 21339 grant (RB); MFAG 21505 – 2018 grant (LF) and Lilly (LF); MFAG 27826 – 2022 grant (AS). DE was supported by AIRC fellowship for Italy – 26795.

Data availability

All relevant data are included in the manuscript and its Supplementary materials file or available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.

Competing interests

AS reports honoraria from Eli Lilly, MSD, and Janssen and travel support from Bristol-Myers Squibb and AstraZeneca. LF declares the following competing interests: consultant and advisory board for Seagen, Amgen, BMS, MSD, Jansen and Pierre Fabre Pharma. RB declares the following competing interests: consultant and advisory board for BMS, MSD, Pfizer, AstraZeneca, Lilly and Novartis. The remaining authors declare no competing interests.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

CRC samples were retrospectively analysed at the Pathology Unit, University of Campania “L. Vanvitelli”. All patients agreed to participate in the study based on informed consent. Research Ethics Committee of the University of Campania “L. Vanvitelli” – AORN “Ospedale dei Colli” approved the study (reference n.0019530/2016). The study was performed in accordance with the Declaration of Helsinki.

Footnotes

Publisher’s note Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

These authors contributed equally: Stefania Belli, Ada Pesapane.

Contributor Information

Luigi Formisano, Email: luigi.formisano1@unina.it.

Roberto Bianco, Email: robianco@unina.it.

Supplementary information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1038/s41416-023-02390-z.

References

- 1.Biller LH, Schrag D. Diagnosis and treatment of metastatic colorectal cancer. JAMA] 2021;325:669. doi: 10.1001/jama.2021.0106. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Douillard J-Y, Oliner KS, Siena S, Tabernero J, Burkes R, Barugel M, et al. Panitumumab–FOLFOX4 treatment and RAS mutations in colorectal cancer. N Engl J Med. 2013;369:1023–34. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa1305275. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Karthaus M, Hofheinz R-D, Mineur L, Letocha H, Greil R, Thaler J, et al. Impact of tumour RAS/BRAF status in a first-line study of panitumumab + FOLFIRI in patients with metastatic colorectal cancer. Br J Cancer. 2016;115:1215–22. doi: 10.1038/bjc.2016.343. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Canon J, Rex K, Saiki AY, Mohr C, Cooke K, Bagal D, et al. The clinical KRAS(G12C) inhibitor AMG 510 drives anti-tumour immunity. Nature. 2019;575:217–23. doi: 10.1038/s41586-019-1694-1. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Skoulidis F, Li BT, Dy GK, Price TJ, Falchook GS, Wolf J, et al. Sotorasib for lung cancers with KRAS p.G12C mutation. N Engl J Med. 2021;384:2371–81. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2103695. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Rane CK, Minden A. P21 activated kinase signaling in cancer. Semin Cancer Biol. 2019;54:40–9. doi: 10.1016/j.semcancer.2018.01.006. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wang K, Baldwin GS, Nikfarjam M, He H. p21-activated kinase signalling in pancreatic cancer: new insights into tumour biology and immune modulation. World J Gastroenterol. 2018;24:3709–23. doi: 10.3748/wjg.v24.i33.3709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Shan L-H, Sun W-G, Han W, Qi L, Yang C, Chai C-C, et al. Roles of fibroblasts from the interface zone in invasion, migration, proliferation and apoptosis of gastric adenocarcinoma. J Clin Pathol. 2012;65:888–95. doi: 10.1136/jclinpath-2012-200909. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Li Q, Zhang X, Wei N, Liu S, Ling Y, Wang H. p21-activated kinase 4 as a switch between caspase-8 apoptosis and NF-κB survival signals in response to TNF-α in hepatocarcinoma cells. Biochem Biophys Res Commun. 2018;503:3003–10. doi: 10.1016/j.bbrc.2018.08.085. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Liu H, Liu K, Dong Z. The role of p21-activated kinases in cancer and beyond: where are we heading? Front Cell Dev Biol. 2021;9:641381. https://www.frontiersin.org/articles/10.3389/fcell.2021.641381/full. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 11.Wang Z, Fu M, Wang L, Liu J, Li Y, Brakebusch C, et al. P21-activated kinase 1 (PAK1) can promote ERK activation in a kinase-independent manner. J Biol Chem. 2013;288:20093–9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 12.Won S-Y, Park J-J, Shin E-Y, Kim E-G. PAK4 signaling in health and disease: defining the PAK4–CREB axis. Exp Mol Med. 2019;51:1–9. doi: 10.1038/s12276-018-0204-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Mauro CD, Pesapane A, Formisano L, Rosa R, D’Amato V, Ciciola P, et al. Urokinase-type plasminogen activator receptor (uPAR) expression enhances invasion and metastasis in RAS mutated tumors. Sci Rep. 2017;7:9388. doi: 10.1038/s41598-017-10062-1. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Huang J, Dibble CC, Matsuzaki M, Manning BD. The TSC1-TSC2 complex is required for proper activation of mTOR complex 2. Mol Cell Biol. 2008;28:4104–15. doi: 10.1128/MCB.00289-08. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Shaw RJ, Cantley LC. Ras, PI(3)K and mTOR signalling controls tumour cell growth. Nature. 2006;441:424–30. doi: 10.1038/nature04869. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ma L, Chen Z, Erdjument-Bromage H, Tempst P, Pandolfi PP. Phosphorylation and functional inactivation of TSC2 by Erk. Cell. 2005;121:179–93. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2005.02.031. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.AlQurashi N, Gopalan V, Smith RA, Lam AKY. Clinical impacts of mammalian target of rapamycin expression in human colorectal cancers. Hum Pathol. 2013;44:2089–96. doi: 10.1016/j.humpath.2013.03.014. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Gulhati P, Bowen KA, Liu J, Stevens PD, Rychahou PG, Chen M, et al. mTORC1 and mTORC2 regulate EMT, motility, and metastasis of colorectal cancer via RhoA and Rac1 signaling pathways. Cancer Res. 2011;71:3246–56. doi: 10.1158/0008-5472.CAN-10-4058. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sudhan DR, Guerrero-Zotano A, Won H, González Ericsson P, Servetto A, Huerta-Rosario M, et al. Hyperactivation of TORC1 drives resistance to the pan-HER tyrosine kinase inhibitor neratinib in HER2-mutant cancers. Cancer Cell. 2020;37:183–199.e5. doi: 10.1016/j.ccell.2019.12.013. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Li Y, Qiu X, Wang X, Liu H, Geck RC, Tewari AK, et al. FGFR-inhibitor-mediated dismissal of SWI/SNF complexes from YAP-dependent enhancers induces adaptive therapeutic resistance. Nat Cell Biol. 2021;23:1187–98. doi: 10.1038/s41556-021-00781-z. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Crawford JJ, Hoeflich KP, Rudolph J. p21-Activated kinase inhibitors: a patent review. Expert Opin Ther Pat. 2012;22:293–310. doi: 10.1517/13543776.2012.668758. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Rudolph J, Murray LJ, Ndubaku CO, O’Brien T, Blackwood E, Wang W, et al. Chemically diverse group I p21-activated kinase (PAK) inhibitors impart acute cardiovascular toxicity with a narrow therapeutic window. J Med Chem. 2016;59:5520–41. doi: 10.1021/acs.jmedchem.6b00638. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Mpilla G, Aboukameel A, Muqbil I, Kim S, Beydoun R, Philip PA, et al. PAK4-NAMPT dual inhibition as a novel strategy for therapy resistant pancreatic neuroendocrine tumors. Cancers (Basel) 2019;11:1902. doi: 10.3390/cancers11121902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Abu Aboud O, Chen C-H, Senapedis W, Baloglu E, Argueta C, Weiss RH. Dual and specific inhibition of NAMPT and PAK4 By KPT-9274 decreases kidney cancer growth. Mol Cancer Ther. 2016;15:2119–29. doi: 10.1158/1535-7163.MCT-16-0197. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Khan HY, Uddin MH, Balasubramanian SK, Sulaiman N, Iqbal M, Chaker M, et al. PAK4 and NAMPT as novel therapeutic targets in diffuse large B-cell lymphoma, follicular lymphoma, and mantle cell lymphoma. Cancers (Basel) 2021;14:160. doi: 10.3390/cancers14010160. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are included in the manuscript and its Supplementary materials file or available from the corresponding author upon reasonable request.