Abstract

Diabetic nephropathy is one of the most significant complications of diabetes, resulting in increased patient mortality. Dapagliflozin is an inhibitor of sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 that has an important protective effect on the kidney. Recent studies showed that pyroptosis is involved in the advancement of diabetic nephropathy (DN). However, the potential molecular mechanisms underlying the association between pyroptosis and renal podocyte injury in DN remain unclear. Thus, the present study investigated the anti-pyroptotic function of dapagliflozin in podocytes and further clarified the potential mechanisms. In this study, a model of lipid metabolism disturbance was established through palmitic acid (PA) induction in a mouse podocyte clone 5 (MPC5) cell line. MPC5 PA-induced pyroptosis was measured by ELISA, western blotting, quantitative PCR and Hoechst 33342/propidium iodide double-fluorescence staining. The protective role of HO-1 was measured using knockdown and overexpression experiments. It was found that dapagliflozin attenuated the expression of pyroptosis-related proteins, including nucleotide oligomerization domain-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase activation and recruitment domain, caspase-1, IL-18 and IL-1β in the PA group. Meanwhile, the heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) expression level decreased within PA, an effect that was reversed by dapagliflozin. Furthermore, the expression of pyroptosis-related proteins and inflammatory cytokines was reduced following HO-1 overexpression. Therefore, these results suggested that dapagliflozin ameliorates MPC5 pyroptosis by mediating HO-1, which has a protective effect on diabetic nephropathy.

Keywords: dapagliflozin, diabetes, pyroptosis, heme oxygenase 1, palmitic acid

Introduction

The main cause of advanced renal disease is diabetic nephropathy globally (1). Renal failure caused by nephropathy involving end-stage diabetes is increasingly becoming one of the principal causes of chronic renal failure (2,3). As an important component of the glomerular filtration barrier, renal podocytes is involved in the progression of diabetic nephropathy (DN). Their damage is associated with proteinuria and severe renal insufficiency (4,5). DN is a metabolic disease mediated by multiple risk factors, such as lipid metabolism disorder, hyperglycemia, advanced glycosylation products and inflammatory response (3). At present, inflammatory diseases are considered to be immune-involved, due to the comprehensive action of various factors, such as hemodynamics, cytokines and growth factors caused by glucose metabolism disorder (6,7).

Dapagliflozin is a relatively novel drug for the treatment of diabetes that acts as a sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitor (SGLT2i), which can reduce the glucose absorption in renal tubules, targeting the kidneys to delay the occurrence and development of diabetic complications. It can also prevent renal function damage and failure in diabetic patients (8,9). A study reported that SGLT2 inhibitors (empagliflozin, canagliflozin and dapagliflozin) generally lowered the risk of death from transplant or dialysis complications (8). An observation report showed that the hazard of a continuous decrease in glomerular filtration rate was reduced by at least 50% among patients with chronic nephrosis (9). As compared with the placebo group, the incidence of terminal kidney disease and mortality rates was significantly reduced in the dapagliflozin group (10). Other studies suggested that SGLT2 inhibitors may improve DN by inhibiting inflammatory response, oxidative stress and autophagy (11). Therefore, SGLT2 inhibitors play an important role in delaying DN (12,13).

Heme oxygenase 1 (HO-1) is a type of antioxidant enzyme that can combat oxidative stress; it is widely distributed in tissues and is more expressed in organs such as the liver, spleen, kidney and heart (14,15). Its metabolic process consumes oxygen (O2), in addition, NADPH is used to provide hydrogen proton, which catalyzes heme catabolism to produce Fe2+, biliverdin and carbon monoxide (CO). The metabolism of the heme group is beneficial to preventing oxidation. Biliverdin and the product of its metabolism, bilirubin, not only have powerful antioxidant and anti-inflammatory effects but can also effectively scavenge reactive oxygen species activity to defend against peroxide, peroxynitrite, hydroxyl and superoxide free radicals (14,16). As a necessary endogenous gas messenger molecule, CO has also anti-inflammatory, vasodilator and microcirculation metabolic roles (16,17). A previous study reported that dapagliflozin as an SGLT2i enhanced the expression of the nuclear factor erythroid 2-related factor 2 (Nrf2)/HO-1 pathway and reduced the levels of oxidative stress biomarkers, leading to amelioration of colitis (18). Dapagliflozin also increased HO-1 expression by increasing Nrf2 protein levels in the rat brain of an Alzheimer's disease model (19).

Pyroptosis is a novel type of programmed cell death during which some immunocompetent cells are activated by caspase-1 under the stimulation of pathogens and inflammatory agents, forming pores in the cell membrane and releasing a large number of inflammatory molecules to the external environment (20,21). In addition, during pyroptosis, the nucleotide oligomerization domain-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3 (NLRP3) inflammasome can cleave caspase-1, causing a cascade reaction and inducing renal inflammatory injury (22,23). Previous studies showed that pyroptosis is widely involved in DN, atherosclerosis, Alzheimer's disease and cardiovascular diseases (24,25).

However, there are only a few studies on the effect of dapagliflozin on cell pyroptosis in diabetic kidney injury and its protection mechanism remains unclear. On this basis, the present study established an in vitro high-fat model of mouse podocyte clone 5 (MPC5) cell line (26) to investigate the improvement effect on renal podocyte of dapagliflozin in palmitic acid (PA)-induced renal podocyte pyroptosis (27,28) and to explore the protective mechanism of dapagliflozin in cell pyroptosis, to provide new ideas for diabetes prevention and treatment.

Materials and methods

Cell culture and transfection

The MPC5 cell line was purchased from the China Center for Type Culture Collection. The basic culture medium for this cell line was composed of 89% RPMI-1640 Medium (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) supplemented with 10% FBS (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.) and 1% penicillin/streptomycin (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.). The MPC5 cell line was maintained at a temperature of 37°C with 5% CO2.

Cells were added to the culture medium following mixing in Opti-MEM for 15 min at room temperature (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.), followed by the addition of antibiotic-free culture medium. pcDNA3.1-HO-1 was then transfected into MPC5 cells using EZ Cell Transfection Reagent (Life-iLab Biotech Co., Ltd.) at a 3:1 (µl/µg) ratio of reagent to DNA; the concentration of nucleic acid was 1,000 ng/µl and pcDNA3.1 was used as the negative control. pcDNA3.1-HO-1 was synthesized by Tsingke Biotech Co., Ltd., with 5′ HindIII and 3′ EcoRV restriction sites.

Small interfering (si)RNA targeting HO-1 (siHO-1) was transfected into MPC5 cells using Lipofectamine™ RNAiMAX (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The final amount of siHO-1 used per well was 25 pmol, while the amount of transfection reagent was 7.5 µl. After 4–6 h of transfection at 37°C, the medium containing the EZ Trans complex was replaced with fresh medium, the cells were further cultured for 12 h and then treated with or without 0.2 mmol PA (Merck Corp) for 24 h. When the drug treatment was complete, the cell samples were used for protein and total RNA extraction. The following sequences were used: siRNA-HO-1 forward, 5′-GUUCAAACAGCUCUAUCGUTT-3′ and reverse, 5′-ACGAUAGAGCUGUUUGAACTT-3′; and siRNA negative control forward, 5′-UUCUCCGACAGUGUCACGUTT-3′ and reverse, 5′-ACGUGACACUGUCGGAGAATT-3′.

Cells were cultured without penicillin/streptomycin in 6-well plates for 24 h, then the culture medium was changed by RPMI-1640 Medium. Added 2 µl MCC950 (MedChemExpress) for 2 h, then 2 µl dapagliflozin were added for 4 h. After 48 h, the cells were used for fluorescent staining.

ELISA

Following treatment with PA (0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3 and 0.4 mmol) for 24 h at 37°C, the cell culture was centrifuged at 1,000 × g at 4°C for 20 min. Cell-free supernatant was collected for NLRP3 detection. NLRP3 content in the supernatant was measured using an ELISA kit (ELK Biotechnology Co., Ltd.), according to the manufacturer's instructions. Each sample was assayed in more than three technical replicates.

Cell proliferation and cytotoxicity assays

Cell Counting Kit-8 (CCK-8; Biosharp Life Sciences) assay was used to measure cell viability. When the cells had grown to 80–90% confluence, digestion was performed with 0.25% Trysin-EDTA. A total of 1×105 MPC5 cell suspension (100 µl) was transferred into 96-well plates followed by treatment with different concentrations of PA or dapagliflozin for 24 h at 37°C. Subsequently, 10 µl CCK-8 solution was added to each well for 2 h. For the controls, the same concentration of CCK-8, culture medium and PA were added to a 96-well plate without the cells (29). Optical density was measured at 450 nm using a microplate reader (Synergy 2; BioTek China).

Western blotting

Total protein was extracted from 2.5×106 MPC5 cells using RIPA lysis buffer (MedChemExpress) supplemented with 1% protease and phosphatase inhibitors for 20 min on ice, followed by centrifugation at 15,520 × g for 10 min at 4°C (30). The protein concentration was quantified using a BCA protein assay kit (Biosharp Life Sciences) and 25 µg protein/lane was separated by SDS-PAGE on a 12% gel. The separated proteins were then transferred onto a PVDF membrane (MilliporeSigma) and blocked with 5% nonfat dry milk for 1 h at room temperature. The membrane was incubated with primary antibodies against NLRP3 (cat. no. A12694, ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), caspase-1 (cat. no. A0964, ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), IL-18 (cat. no. A16737, ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), IL-1β (cat. no. A11396&A16288, ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.) and HO-1 (cat. no. A19062, ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.), as well as a β-actin antibody (GB11001-100, Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) used as the internal reference, for 10 h at 4°C. All antibodies were diluted at 1:1,000 in western blot primary antibody dilution buffer (ABclonal Biotech Co., Ltd.). Following primary incubation, the PVDF membrane was incubated with anti-rabbit IgG secondary antibody (cat. no. BL003A; 1:10,000; Biosharp Life Sciences) at room temperature for 1 h and then developed using a Pierce™ ECL chemiluminescence kit (Thermo Fisher Scientific, Inc.). The protein bands were exposed and observed in a multifunctional digital gel imaging analysis system and images were obtained (Bio-Rad GelDoc™ XR and ChemiDoc™ XRS System; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.). Finally, ImageJ v1.51 (National Institutes of Health) was used for target protein expression analysis.

Reverse transcription-quantitative PCR (RT-qPCR)

The cell culture medium was removed and the 2.5×106 cells from 6-well plates were washed with 2 ml of 4°C pre-cooled PBS. The PBS was then thoroughly removed and 1 ml RNA extraction solution (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) was added to each sample in the 6-well plate, the bottom cells were gently shaken off the plate to fully contact the RNA extraction solution and the RNA extraction solution was then transferred to a 1.5-ml Eppendorf tube at room temperature for 5 min.

cDNA was synthesized using a reverse transcription kit (Novoprotein Scientific, Inc.), according to the manufacturer's instructions. The 2X SYBR Green qPCR Master Mix Kit (Wuhan Servicebio Technology Co., Ltd.) was used to quantify the relative mRNA levels of ASC, NLRP3, IL-18 and IL-1β (31). qPCR was performed using the qPCR System (CFX Connect; Bio-Rad Laboratories, Inc.) for 40 cycles, with GAPDH serving as internal controls. The sequences of primer pairs used for qPCR were as follows: NLRP3 forward, 5′-GCAGCCTCACCTCACACAGCT-3′ and reverse, 5′-TTTCACCCAACTGTAGGCTCT-3′; ASC forward, 5′-CTGACTGAAGGACAGTACCAG-3′ and reverse, 5′-TCCTGACTTTGTATACACAAT-3′; IL-1β forward, 5′-CTCACAAGCAGAGCACAAGC-3′ and reverse, 5′-AGCTGTCTGCTCATTCACGA-3′; IL-18 forward, 5′-GACTCTTGCGTCAACTTCAAGG-3′ and reverse, 5′-CAGGCTGTCTTTTGTCAACGA-3′; HO-1 forward, 5′-AAGGGAGAATCTTGCCTGGCT-3′ and reverse, 5′-ACCCCTCAAAAGATAGCCCCA-3′; GAPDH forward, 5′-AAGAAGGTGGTGAAGCAGGC-3′ and reverse, 5′-TCCACCACCCTGTTGCTGTA-3′.

Hoechst 33342/propidium iodide (PI) fluorescent staining

The cultured cells were washed twice with PBS, followed by the addition of 1 ml cell staining buffer in the Hoechst 33342/PI double stain kit (Solarbio Science & Technology Co., Ltd.). Subsequently, 5 µl Hoechst 33342 staining solution and 5 µl PI staining solution were mixed and kept at 4°C for 20 min (32). Following staining, the cells were washed twice with PBS and observed with a 10Χ objective lens using a fluorescent microscope (IX71; Olympus Corporation).

Statistical analysis

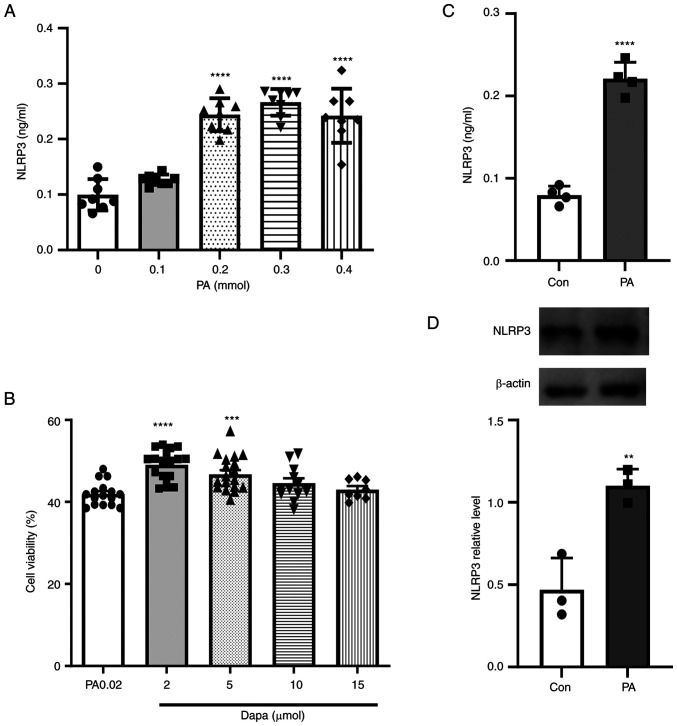

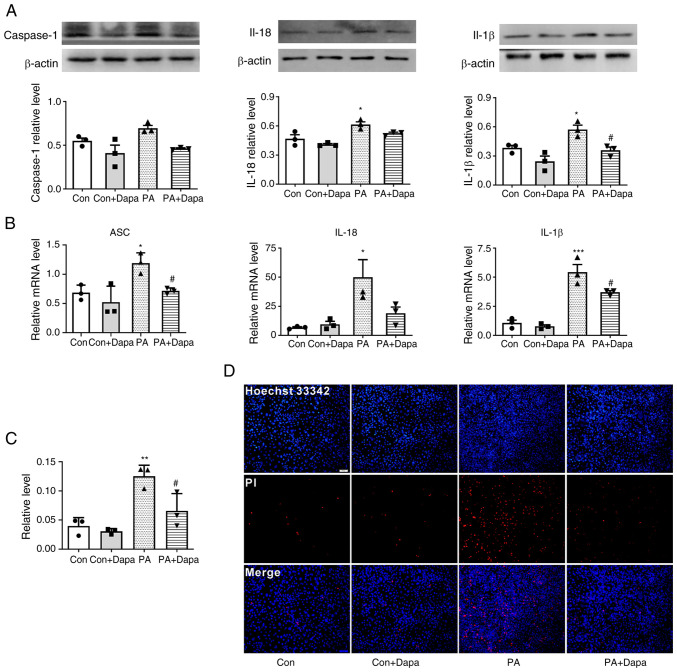

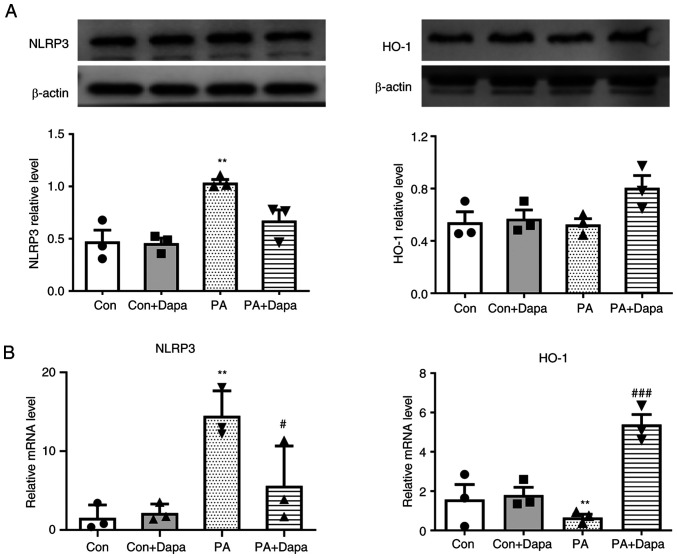

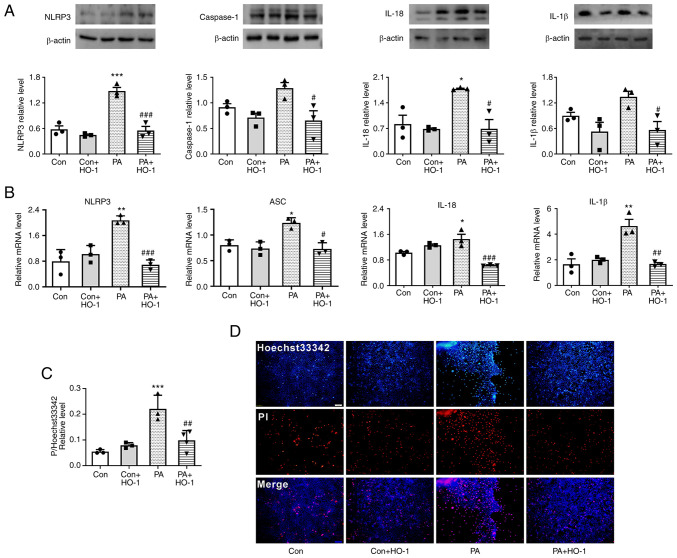

GraphPad Prism 9 software (GraphPad Software; Dotmatics) was used for drawing and statistical analysis. Differences between the control group and each other group in Fig. 1A and B were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Dunnett's post hoc test. An unpaired t-test was used for comparisons between two groups in Fig. 1C and D. Differences between multiple groups were analyzed using one-way ANOVA followed by Tukey's post hoc test (Fig. 2, Fig. 3, Fig. 4). P<0.05 was considered to indicate a statistically significant difference (33).

Figure 1.

Effect of PA on the NLRP3 inflammasome in MPC5 cells and cell viability assay following dapagliflozin treatment. (A) NLRP3 inflammatory production in MPC5 cells following treatment with different PA concentrations (0, 0.1, 0.2, 0.3 and 0.4 mmol). (B) NLRP3 inflammasome production significantly increased in MPC5 cells treated with 0.2 mmol PA. (C) Cell Counting Kit-8 cytotoxicity assay following treatment with different concentrations of dapagliflozin (2, 5, 10 and 15 µmol). (D) NLRP3 inflammatory protein expression increased in MPC5 cells following treatment with 0.2 mmol PA. **P<0.001, ***P<0.001, ****P<0.0001 vs. control group. PA, palmitic acid; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3; MPC5, mouse podocyte clone 5; Con, control; dapa, dapagliflozin.

Figure 2.

Dapagliflozin inhibits PA-induced pyroptosis in MPC5 cells. (A) The protein expression of caspase-1, IL-18 and IL-1β decreased following dapagliflozin treatment. (B) The relative mRNA level of ASC, IL-18 and IL-1β decreased following dapagliflozin treatment in MPC5 cells. (C) Relative cell count ratio of PI uptake. (D) Photomicrographs of double-fluorescent staining with Hoechst 33342/PI. PA, 0.2 mmol; Dapa, 2 µmol; scale bar, 100 µm. *P<0.05, **P<0.01 vs. control group; #P<0.05 vs. PA group. Con, control; Dapa, dapagliflozin; MPC5, mouse podocyte clone 5; PA, palmitic acid; ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase activation and recruitment domain; PI, propidium iodide.

Figure 3.

Effect of dapagliflozin on protein expression and relative mRNA level of NLRP3 and HO-1 in MPC5 cells. (A) Dapagliflozin decreased the protein expression of NLRP3 and increased that of HO-1. (B) Dapagliflozin decreased the relative mRNA expression of NLRP3 and increased that of HO-1. PA, 0.2 mmol; Dapagliflozin, 2 µmol. **P<0.01 vs. control group; #P<0.05, ###P<0.001 vs. PA group. NLRP3, NOD-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3; HO-1, heme oxygenase 1; Dapa, dapagliflozin; MPC5, mouse podocyte clone 5; PA, palmitic acid; Con, control.

Figure 4.

HO-1 overexpression inhibits PA-induced pyroptosis in MPC5 cells. (A) HO-1 overexpression decreased the expression of NLRP3, caspase-1, IL-18 and IL-1β in MPC5 cells. (B) HO-1 overexpression decreased the relative mRNA level of NLRP3, caspase-1, IL-18 and IL-1β in MPC5 cells. (C) Relative cell count ratio of PI uptake. (D) Photomicrographs of double-fluorescent staining with Hoechst 33342/PI. PA, 0.2 mmol; scale bar, 100 µm. *P<0.05, **P<0.001, ***P<0.001 vs. control group; #P<0.05, ##P<0.01, ###P<0.001 vs. PA group. HO-1, heme oxygenase 1; MPC5, mouse podocyte clone 5; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3; PA, palmitic acid; Con, control; Dapa, dapagliflozin.

Results

NLRP3 inflammasome increases in MPC5 cells under PA

The pathophysiology of diabetes is complicated and involves glucose and lipid metabolism disorders. Fat deposits in the kidneys have been suggested to be instrumental to DN, so different concentrations of PA were used to pretreat cells in lipid metabolism-related experiments (34–36).

According to the results of the microplate reader detection of cell-released NLRP3 inflammasome, the present study showed that, under the induction of PA, MPC5 cells released a large amount of NLRP3 inflammasome (Fig. 1B). The protein expression of NLRP3 was also increased in MPC5 cells (Fig. 1D). However, inflammasome release was not significantly increased with increasing PA content. When the PA concentration reached 0.3 mmol, the release amount of NLRP3 inflammasome decreased (Fig. 1A) and a large number of dead cells floated in the culture dish at this time, which indicated that a high PA concentration had a detrimental effect on cell viability. In brief, 0.2 mmol was selected as the PA concentration in this experiment. Based on various relevant studies, concentrations of 2, 5, 10 and 15 µmol dapagliflozin were selected to verify the most suitable treatment methods, following treatment with 0.2 mmol PA. The drug effect was examined through a CCK-8 assay, which showed that when the concentration of dapagliflozin was >5 µmol, the number of viable cells began to decrease. Thus, the CCK-8 assay results showed that 2 µmol dapagliflozin was appropriate as the protective concentration for subsequent experiments (Fig. 1C).

Dapagliflozin inhibits PA-induced pyroptosis in MPC5 cells

Western blot results suggested that the expression of pyroptosis-related proteins NLRP3 and caspase-1 was increased compared with that in the control group. The expression of inflammatory cytokines IL-18 and IL-1β was increased by PA treatment. Following the addition of dapagliflozin, the expression of pyroptosis-related proteins decreased. At the same time, the content of intracellular inflammatory factors was also decreased (Fig. 2A).

qPCR results indicated that the mRNA levels of NLRP3 inflammasome, ASC, and inflammatory factors IL-18 and IL-1β were increased following the treatment of MPC5 cells with PA. Following the addition of dapagliflozin, the mRNA levels of inflammatory and pyroptosis-related factors were significantly decreased (Fig. 2B).

Dapagliflozin reduces the level of membrane rupture in MPC5

Hoechst 33342/PI fluorescence staining results indicated that the uptake of PI dye by MPC5 cells was increased following PA treatment and significantly decreased following the addition of dapagliflozin (Fig. 2C and D).

MCC950 is an effective and selective NLRP3 inhibitor, which can specifically inhibit activation of NLRP3 and reduced IL-1β production in vivo. After MCC950 was added, the uptake of PI dye by MPC5 cells also decreased. When both MCC950 and dapagliflozin were added to the cells, the uptake of PI dye decreased (Fig. S1). This result indicated that cell membrane damage was attenuated when NLRP3 was inhibited and dapagliflozin might also reduce the membrane damage by inhibiting the activity of NLRP3.

HO-1 is associated with the anti-pyroptosis effect of dapagliflozin in MPC5

The protein expression of HO-1 decreased following the treatment of MPC5 cells with PA, which was consistent with the qPCR results. However, following dapagliflozin treatment, HO-1 protein and mRNA expression levels were both increased (Fig. 3).

HO-1 overexpression restrains PA-induced pyroptosis in MPC5 cells

Western blot analysis indicated that the expression levels of pyroptosis-related proteins NLRP3 and caspase-1, as well as inflammatory factors IL-18 and IL-1β, decreased following HO-1 overexpression in the PA group (Fig. 4A). Meanwhile, NLRP3 inflammasome, IL-18 and IL-1β increased following transfection with siHO1. Moreover, when dapagliflozin was added, NLRP3 inflammasome, IL-18 and IL-1β decreased (Fig. S2A).

qPCR results indicated that the mRNA levels of NLRP3 inflammasome and ASC, as well as inflammatory factors IL-18 and IL-1β, significantly decreased following HO-1 overexpression in MPC5 cells (Fig. 4B).

HO-1 overexpression reduces the level of membrane rupture in MPC5

According to Hoechst 33342/PI fluorescence staining, when HO-1 was overexpressed in the PA group, the PI uptake of MPC5 cells was significantly reduced (Fig. 4C and D). This result suggested that a large number of cell membranes were damaged following treatment with PA, while HO-1 overexpression reduced this damage.

Discussion

SGLT2 inhibitors are a type of anti-diabetic agent that can lower glucose reabsorption and lead to urinary glucose excretion (37–39). Their therapeutic effects include lowering lipid markers, assisting weight loss and delaying diabetic vascular complications. Specifically, dapagliflozin has been proven to be effective in preventing and slowing renal function loss and failure in diabetic patients (10). Previous studies suggested that the protective effect of SGLT2 inhibitors is closely associated with the reduction of inflammatory markers including TNF-α, IL-1β and IL-6, and the inhibition of oxidative stress. In addition, SGLT2 inhibitors can help lower blood sugar and lipids, rendering dapagliflozin an ideal drug for the treatment of metabolic abnormalities (40,41). As a recently discovered type of programmed cell death, pyroptosis was shown to be extensively involved in diseases such as diabetes and atherosclerosis, and its key features are loss of cytoplasmic membrane integrity and release of several inflammatory cytokines (20,22). Therefore, it was found that PA can induce NLRP3 inflammasomes in renal podocytes and inflammasome activation can then increase insulin resistance in diabetic patients and significantly increase blood glucose and insulin levels, which are linked to hyperglycemia and hyperinsulinemia. The NLRP3 inflammasome is an intracellular platform that converts the proinflammatory cytokines IL-1β and IL-18 to their active forms in response to ‘danger’ signals, which can be either host or pathogen-derived (20,42,43). Thus, the present authors chose inflammatory cytokines of IL-18 and IL-1β for detection and verification of NLRP3 activation levels.

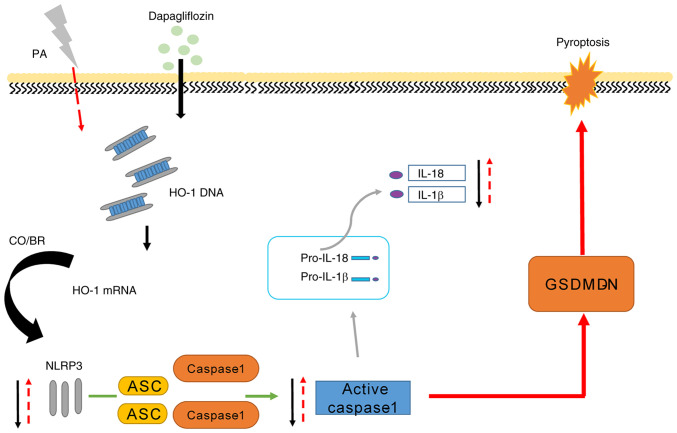

Pyroptosis-related signals were also detected in MPC5 cells following PA treatment; the expression of NLRP3 and caspase-1 was found to be significantly increased, as well as the inflammatory factors IL-18 and IL-1β. A significant increase in pyrototic pores was observed in the Hoechst 33342/PI staining assay. Based on this, we hypothesized that PA acts as a stimulating factor to induce NLRP3 upregulation in MPC5 cells, further resulting in the formation and activation of caspase-1. The mature inflammatory factors pro-IL-18 and pro-IL-1β were activated by active caspase-1, which led to the generation of the inflammatory reaction in cells and the phenomenon of pyroptosis. Following dapagliflozin treatment, the expression of NLRP3, caspase-1 and inflammatory cytokines IL-18 and IL-1β decreased. Meanwhile, the degree of cell plasma membrane rupture decreased. Compared with previous studies, the aforementioned experimental results indicated that the activation of NLRP3 inflammatory signaling may serve a role in diabetic cell injury and dapagliflozin may slow down the phenomenon of pyroptosis by inhibiting the NLRP3 inflammasome-mediated inflammatory response. These results provide scientific validation for further exploration of the therapeutic effect of dapagliflozin on PA-induced renal cell pyroptosis.

HO-1 is an important rate-limiting enzyme in the process of heme catabolism, which plays a key role in oxidative stress and inflammatory damage (15). The present study found that HO-1 expression decreased following MPC5 induction by PA and increased following dapagliflozin treatment. Moreover, HO-1 overexpression in MPC5 significantly reduced the uptake of PI and the level of cytoplasmic membrane rupture. The above experimental results confirmed that HO-1 could reduce cell damage in high-fat in vitro models and that dapagliflozin may mediate the expression of HO-1 to inhibit cell pyroptosis, hence exerting a renal protective effect (Fig. 5). This result suggests that the protective role of dapagliflozin might be mediated by the regulation of HO-1 expression.

Figure 5.

Dapagliflozin improves renal podocyte pyroptosis by regulating HO-1/NLRP3 signaling under PA. PA or high fat resulted in an increased NLRP3 expression and NLRP3 inflammasome activated downstream factors such as cleaved caspase-1, IL-1β and IL-18. Of note, dapagliflozin could alleviate cell injury by increasing HO-1-expression mediated by NLRP3 inflammasome activation in MPC5 cells. HO-1, heme oxygenase 1; NLRP3, NOD-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3; PA, palmitic acid; ASC, apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase activation and recruitment domain; GSDMDN, gasdermin D N-terminal fragment.

In conclusion, dapagliflozin was found to significantly improve dyslipidemia damage by restraining pyroptosis in MPC5 cells. These results showed that HO-1 mediates the anti-pyroptosis effects of dapagliflozin. However, the detailed molecular mechanism of dapagliflozin affects HO-1 in pyroptosis protective pathway was not verified in the present study and will be further investigated in future studies. Further studies are also required to verify the present results in vivo.

Supplementary Material

Acknowledgements

Not applicable.

Glossary

Abbreviations

- ASC

apoptosis-associated speck-like protein containing a caspase activation and recruitment domain

- NLRP3

nucleotide oligomerization domain-like receptor thermal protein domain associated protein 3

- caspase-1

cysteinyl aspartate specific proteinase

- Dapa

dapagliflozin

- DN

diabetic nephropathy

- HO-1

heme oxygenase 1

- IL-1β

interleukin-1β

- IL-18

interleukin-18

- PA

palmitic acid

- SGLT2

sodium-glucose cotransporter 2

- MPC5

mouse podocyte clone 5

Funding Statement

This present study was supported by the Foundation of Hubei Educational Committee (grant no. Q20202803) and the Special Project on Diabetes and Angiopathy (grant nos. 2020TNB10 and 2022TNB11) and the Doctoral Scientific Research Foundation of Hubei University of Science and Technology (grant no. BK202010).

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.

Authors' contributions

BZ and CL conceived and designed the experiments; ZZ and BZ drafted the manuscript; ZZ, PN, MT and YS acquired and analyzed the data, and interpretated the results; PN and CL revised the draft critically. ZZ and BZ confirm the authenticity of all the raw data. All the authors read and approved the final version of the manuscript.

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Not applicable.

Patient consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare that they have no competing interests.

References

- 1.Shi Y, Hu FB. The global implications of diabetes and cancer. Lancet. 2014;383:1947–1948. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(14)60886-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lee HB, Ha H, Kim SI, Ziyadeh FN. Diabetic kidney disease research: Where do we stand at the turn of the century? Kidney Int Suppl. 2000;77:S1–S2. doi: 10.1046/j.1523-1755.2000.07701.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Samsu N. Diabetic nephropathy: Challenges in pathogenesis, diagnosis, and treatment. Biomed Res Int. 2021;2021:1497449. doi: 10.1155/2021/1497449. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Jin J, Hu K, Ye M, Wu D, He Q. Rapamycin reduces podocyte apoptosis and is involved in autophagy and mTOR/P70S6K/4EBP1 signaling. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2018;48:765–772. doi: 10.1159/000491905. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Lin X, Zhen X, Huang H, Wu H, You Y, Guo P, Gu X, Yang F. Role of MiR-155 signal pathway in regulating podocyte injury induced by TGF-β1. Cell Physiol Biochem. 2017;42:1469–1480. doi: 10.1159/000479211. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Tuttle KR, Bakris GL, Bilous RW, Chiang JL, de Boer IH, Goldstein-Fuchs J, Hirsch IB, Kalantar-Zadeh K, Narva AS, Navaneethan SD, et al. Diabetic kidney disease: A report from an ADA consensus conference. Diabetes Care. 2014;37:2864–2883. doi: 10.2337/dc14-1296. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Wada J, Makino H. Inflammation and the pathogenesis of diabetic nephropathy. Clin Sci (Lond) 2013;124:139–152. doi: 10.1042/CS20120198. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Cassis P, Locatelli M, Cerullo D, Corna D, Buelli S, Zanchi C, Villa S, Morigi M, Remuzzi G, Benigni A, Zoja C. SGLT2 inhibitor dapagliflozin limits podocyte damage in proteinuric nondiabetic nephropathy. JCI Insight. 2018;3:e98720. doi: 10.1172/jci.insight.98720. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Heerspink HJL, Stefánsson BV, Correa-Rotter R, Chertow GM, Greene T, Hou FF, Mann JFE, McMurray JJV, Lindberg M, Rossing P, et al. Dapagliflozin in patients with chronic kidney disease. N Engl J Med. 2020;383:1436–1446. doi: 10.1056/NEJMoa2024816. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Neuen BL, Young T, Heerspink HJL, Neal B, Perkovic V, Billot L, Mahaffey KW, Charytan DM, Wheeler DC, Arnott C, et al. SGLT2 inhibitors for the prevention of kidney failure in patients with type 2 diabetes: A systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet Diabetes Endocrinol. 2019;7:845–854. doi: 10.1016/S2213-8587(19)30256-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Ala M. SGLT2 inhibition for cardiovascular diseases, chronic kidney disease, and NAFLD. Endocrinology. 2021;162:bqab157. doi: 10.1210/endocr/bqab157. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Neumiller JJ, White JR, Jr, Campbell RK. Sodium-glucose co-transport inhibitors: Progress and therapeutic potential in type 2 diabetes mellitus. Drugs. 2010;70:377–385. doi: 10.2165/11318680-000000000-00000. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.El-Rous MA, Saber S, Raafat EM, Ahmed AAE. Dapagliflozin, an SGLT2 inhibitor, ameliorates acetic acid-induced colitis in rats by targeting NFκB/AMPK/NLRP3 axis. Inflammopharmacology. 2021;29:1169–1185. doi: 10.1007/s10787-021-00818-7. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Takahashi T, Morita K, Akagi R, Sassa S. Heme oxygenase-1: A novel therapeutic target in oxidative tissue injuries. Curr Med Chem. 2004;11:1545–1561. doi: 10.2174/0929867043365080. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Kozakowska M, Dulak J, Józkowicz A. Heme oxygenase-1-more than the cytoprotection. Postepy Biochem. 2015;61:147–158. (In Polish) [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Ryter SW, Alam J, Choi AMK. Heme oxygenase-1/carbon monoxide: From basic science to therapeutic applications. Physiol Rev. 2006;86:583–650. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00011.2005. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Otterbein L, Chin BY, Otterbein SL, Lowe VC, Fessler HE, Choi AM. Mechanism of hemoglobin-induced protection against endotoxemia in rats: A ferritin-independent pathway. Am J Physiol. 1997;272:L268–L275. doi: 10.1152/ajplung.1997.272.2.L268. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Arab HH, Al-Shorbagy MY, Saad MA. Activation of autophagy and suppression of apoptosis by dapagliflozin attenuates experimental inflammatory bowel disease in rats: Targeting AMPK/mTOR, HMGB1/RAGE and Nrf2/HO-1 pathways. Chem Biol Interact. 2021;335:109368. doi: 10.1016/j.cbi.2021.109368. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Samman WA, Selim SM, El Fayoumi HM, El-Sayed NM, Mehanna ET, Hazem RM. Dapagliflozin ameliorates cognitive impairment in aluminum-chloride-induced Alzheimer's disease via modulation of AMPK/mTOR, oxidative stress and glucose metabolism. Pharmaceuticals (Basel) 2023;16:753. doi: 10.3390/ph16050753. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Fuchs Y, Steller H. Programmed cell death in animal development and disease. Cell. 2011;147:742–758. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.10.033. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Bertheloot D, Latz E, Franklin BS. Necroptosis, pyroptosis and apoptosis: An intricate game of cell death. Cell Mol Immunol. 2021;18:1106–1121. doi: 10.1038/s41423-020-00630-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Hutton HL, Ooi JD, Holdsworth SR, Kitching AR. The NLRP3 inflammasome in kidney disease and autoimmunity. Nephrology (Carlton) 2016;21:736–744. doi: 10.1111/nep.12785. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Cookson BT, Brennan MA. Pro-inflammatory programmed cell death. Trends Microbiol. 2001;9:113–114. doi: 10.1016/S0966-842X(00)01936-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Al Mamun A, Ara Mimi A, Wu Y, Zaeem M, Abdul Aziz M, Aktar Suchi S, Alyafeai E, Munir F, Xiao J. Pyroptosis in diabetic nephropathy. Clin Chim Acta. 2021;523:131–143. doi: 10.1016/j.cca.2021.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.He X, Fan X, Bai B, Lu N, Zhang S, Zhang L. Pyroptosis is a critical immune-inflammatory response involved in atherosclerosis. Pharmacol Res. 2021;165:105447. doi: 10.1016/j.phrs.2021.105447. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Tu Q, Li Y, Jin J, Jiang X, Ren Y, He Q. Curcumin alleviates diabetic nephropathy via inhibiting podocyte mesenchymal transdifferentiation and inducing autophagy in rats and MPC5 cells. Pharm Biol. 2019;57:778–786. doi: 10.1080/13880209.2019.1688843. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Chu SG, Villalba JA, Liang X, Xiong K, Tsoyi K, Ith B, Ayaub EA, Tatituri RV, Byers DE, Hsu FF, et al. Palmitic acid-rich high-fat diet exacerbates experimental pulmonary fibrosis by modulating endoplasmic reticulum stress. Am J Respir Cell Mol Biol. 2019;61:737–746. doi: 10.1165/rcmb.2018-0324OC. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Urso CJ, Zhou H. Palmitic acid lipotoxicity in microglia cells is ameliorated by unsaturated fatty acids. Int J Mol Sci. 2021;22:9093. doi: 10.3390/ijms22169093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Zhu B, Liu Q, Han Q, Zeng B, Chen J, Xiao Q. Downregulation of Krüppel-like factor 1 inhibits the metastasis and invasion of cervical cancer cells. Mol Med Rep. 2018;18:3932–3940. doi: 10.3892/mmr.2018.9401. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Zhang L, Jiang B, Zhu N, Tao M, Jun Y, Chen X, Wang Q, Luo C. Mitotic checkpoint kinase Mps1/TTK predicts prognosis of colon cancer patients and regulates tumor proliferation and differentiation via PKCα/ERK1/2 and PI3K/Akt pathway. Med Oncol. 2019;37:5. doi: 10.1007/s12032-019-1320-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Dong D, Wu J, Sheng L, Gong X, Zhang Z, Yu C. FUNDC1 induces apoptosis and autophagy under oxidative stress via PI3K/Akt/mTOR pathway in cataract lens cells. Curr Eye Res. 2022;47:547–554. doi: 10.1080/02713683.2021.2021586. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Wu J, Li QQ, Zhou H, Lu Y, Li JM, Ma Y, Wang L, Fu T, Gong X, Weintraub M, et al. Selective tumor cell killing by triptolide in p53 wild-type and p53 mutant ovarian carcinomas. Med Oncol. 2014;31:14. doi: 10.1007/s12032-014-0014-8. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Gao ZD, Yan HD, Wu NH, Yao Q, Wan BB, Liu XF, Zhang ZW, Chen QJ, Huang CP. Mechanistic insights into the amelioration effects of lipopolysaccharide-induced acute lung injury by baicalein: An integrated systems pharmacology study and experimental validation. Pulm Pharmacol Ther. 2022:73–74. 102121. doi: 10.1016/j.pupt.2022.102121. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Huang B, Wen W, Ye S. Dapagliflozin ameliorates renal tubular ferroptosis in diabetes via SLC40A1 stabilization. Oxid Med Cell Longev. 2022;2022:9735555. doi: 10.1155/2022/9735555. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Chen X, Han Y, Gao P, Yang M, Xiao L, Xiong X, Zhao H, Tang C, Chen G, Zhu X, et al. Disulfide-bond A oxidoreductase-like protein protects against ectopic fat deposition and lipid-related kidney damage in diabetic nephropathy. Kidney Int. 2019;95:880–895. doi: 10.1016/j.kint.2018.10.038. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Du Q, Wu X, Ma K, Liu W, Liu P, Hayashi T, Mizuno K, Hattori S, Fujisaki H, Ikejima T. Silibinin alleviates ferroptosis of rat islet β cell INS-1 induced by the treatment with palmitic acid and high glucose through enhancing PINK1/parkin-mediated mitophagy. Arch Biochem Biophys. 2023;743:109644. doi: 10.1016/j.abb.2023.109644. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Pafili K, Maltezos E, Papanas N. The potential of SGLT2 inhibitors in phase II clinical development for treating type 2 diabetes. Expert Opin Investig Drugs. 2016;25:1133–1152. doi: 10.1080/13543784.2016.1216970. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Pafili K, Papanas N. Luseogliflozin and other sodium-glucose cotransporter 2 inhibitors: No enemy but time? Expert Opin Pharmacother. 2015;16:453–456. doi: 10.1517/14656566.2015.994505. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Plosker GL. Dapagliflozin: A review of its use in patients with type 2 diabetes. Drugs. 2014;74:2191–2209. doi: 10.1007/s40265-014-0324-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Kimura T, Obata A, Shimoda M, Okauchi S, Kanda-Kimura Y, Nogami Y, Moriuchi S, Hirukawa H, Kohara K, Nakanishi S, et al. Protective effects of the SGLT2 inhibitor luseogliflozin on pancreatic β-cells in db/db mice: The earlier and longer, the better. Diabetes Obes Metab. 2018;20:2442–2457. doi: 10.1111/dom.13400. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Daems C, Welsch S, Boughaleb H, Vanderroost J, Robert A, Sokal E, Lysy PA. Early treatment with empagliflozin and GABA improves β-cell mass and glucose tolerance in streptozotocin-treated mice. J Diabetes Res. 2019;2019:2813489. doi: 10.1155/2019/2813489. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Jorgensen I, Rayamajhi M, Miao EA. Programmed cell death as a defence against infection. Nat Rev Immunol. 2017;17:151–164. doi: 10.1038/nri.2016.147. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Jourdan T, Godlewski G, Cinar R, Bertola A, Szanda G, Liu J, Tam J, Han T, Mukhopadhyay B, Skarulis MC, et al. Activation of the Nlrp3 inflammasome in infiltrating macrophages by endocannabinoids mediates beta cell loss in type 2 diabetes. Nat Med. 2013;19:1132–1140. doi: 10.1038/nm.3265. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding author on reasonable request.