Abstract

Ciprofloxacin pharmacokinetics have been shown to be modified in patients with renal failure (e.g., the intestinal secretion of ciprofloxacin is increased). This study investigated the influence of renal failure on the pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin following oral and parenteral administration to rats of a dose of 50 mg/kg of body weight. After parenteral administration, only renal clearance (CLR) was reduced in nephrectomized rats (5.3 ± 1.4 versus 17.8 ± 4.7 ml/min/kg, P < 0.01, nephrectomized versus control rats). However, nonrenal clearance was increased in nephrectomized rats (32 ± 4 versus 15 ± 5 ml/min/kg, P < 0.01, nephrectomized versus control rats), suggesting compensatory mechanisms for reduced renal function. After oral administration, apparent total clearance and CLR were reduced (P < 0.01) in nephrectomized rats (117 ± 25 and 6.8 ± 4.4 ml/min/kg, respectively) compared with the values for control rats (185 ± 9 and 22.6 ± 5.3 ml/min/kg, respectively) and the area under the concentration-time curve was higher (P < 0.01) for nephrectomized rats (436.3 ± 90.5 mg · min/liter) than for control rats (271.3 ± 14.3 mg · min/liter). Terminal elimination half lives in the two groups remained constant after oral and parenteral administration. These results suggest an increased bioavailability of ciprofloxacin in nephrectomized rats, which was confirmed by a nonlinear mixed-effect model.

In healthy volunteers, oral ciprofloxacin is rapidly absorbed, with a bioavailability (F) ranging from 50 to 85% (5, 17, 24). Its intestinal absorption occurs mainly in the duodenum and the jejunum, mostly via passive-diffusion mechanisms (11). The first-pass effect through the liver is thought to be unimportant (approximately 5%) (27). Ciprofloxacin diffuses into most body tissues (with particular affinities for the lungs and the prostate), with its protein binding approximating 16 to 40% (5, 24, 27). Ciprofloxacin is mainly eliminated via the kidneys, with 40 to 60% of an administered dose being recovered in the urine in the unchanged form (1). Both glomerular filtration and active tubular secretion appear to be implicated (25). Nonrenal elimination is accounted for by hepatic metabolism (15 to 20%), biliary secretion (less than 1%), and mostly intestinal secretion (10 to 15%) (1, 15, 23, 24).

In moderate renal failure (RF) (creatinine clearance [CLCR] ranging from 30 to 45 ml/min), ciprofloxacin pharmacokinetic parameters were found to be only slightly altered (2, 12). Concentrations in plasma are higher, leading to 25% increases in areas under the concentration-time curves (AUC) (2). Total and renal clearances (CLT and CLR, respectively) were reduced, while the distribution volume (V) remained constant (7, 9). However, ciprofloxacin half-lives (t1/2) were not significantly different between healthy subjects (5.8 ± 1.2 h) and patients suffering from moderate RF (6.9 ± 1.0 h) (2).

In contrast, in patients with severe RF (CLCR being less than 30 ml/min), the ciprofloxacin t1/2 doubled, as a consequence of drastically reduced CLR (2, 6, 7, 9, 12, 21). Rohwedder and coworkers (16) showed that severe RF was accompanied by an increase in the elimination in feces of both ciprofloxacin and its metabolites (37.2% ± 12.5% and 26.2% ± 6.5%, respectively, versus 11.4% ± 2.6% and 7.3% ± 1.6% in healthy subjects), probably to compensate for the decreased renal elimination.

In order to characterize the role of the nonrenal processes in the bodily disposition of ciprofloxacin in patients with RF, we validated a rat model of RF. The consequences of RF on ciprofloxacin pharmacokinetics following oral and parenteral administrations were evaluated.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Experimental protocol.

Twenty-eight male Sprague-Dawley rats, weighing between 220 and 280 g, were housed in individual cages. Three weeks before the experiment, 14 rats underwent 80% nephrectomies, to mimic chronic renal insufficiency. These nephrectomies were carried out in two stages. First, the two poles of each rat’s left kidney were excised and weighed to remove 60% of the kidney mass, with the mean kidney weight of five normal rats as a reference. Hemostatic powder (Pangen; Fournier, Dijon, France) was used to avoid bleeding. Four days later, the right kidneys were completely removed (4). The control rats underwent a laparotomy only. The first surgery was performed under pentobarbital anesthesia (60 mg/kg of body weight; Sanofi, Libourne, France), and the second was performed under ether anesthesia. All rats were fed a low-sodium diet to avoid the development of hypertension in nephrectomized rats. During the night, rats were food deprived for 12 h prior to and 2 h postadministration of ciprofloxacin. Water was given ad libitum.

Twenty-four hours prior to the experiment, rats were anesthetized with pentobarbital (60 mg/kg) and catheters were installed in their carotid arteries to allow the parenteral administration of ciprofloxacin and blood sample collections.

Rats were divided into two groups of control and nephrectomized animals. Within each group, seven rats received ciprofloxacin parenterally and seven received it orally.

Ciprofloxacin chlorhydrate was generously given by Bayer Pharma (Puteaux, France). Ciprofloxacin solutions (10 g/liter) were prepared in 0.9% NaCl. The selected dose (50 mg/kg) was administered either via the carotid artery (1-min perfusion) or via oral gavage.

Sample collection.

Blood samples (0.3 ml) were collected in heparinized test tubes and immediately centrifuged. Plasma was aspirated and frozen at −20°C. A blank blood sample was withdrawn before ciprofloxacin administration in order to measure creatinine levels.

Blood samples were collected at 5, 15, 30, 45, 60, 75, 120, 240, 420, 600, and 1,440 min after parenteral administration of ciprofloxacin and at 10, 20, 30, 45, 60, 75, 120, 240, 360, 600, and 1,440 min after oral administration of ciprofloxacin. Blood was replaced by an equal volume of saline. Urine was collected over 24 h.

Analytical method.

Plasma and urine ciprofloxacin levels were determined by reversed-phase (C18 column) high-performance liquid chromatography coupled with fluorimetric detection (18). The method was linear over the concentration range of 0.12 to 40 mg/liter. Intra- and interday coefficients of variation were less than 10%. The limit of detection was 0.04 mg/liter, while the limit of quantitation was 0.12 mg/liter.

Creatinine concentrations in plasma and urine were measured according to the method of Jaffé.

Pharmacokinetic analyses. (i) Noncompartmental analysis.

Concentration-time data for individual rats were analyzed with Siphar/Win software (Simed, Créteil, France).

Peak concentrations in plasma (Cmax) and the time needed to reach Cmax were determined by visual inspection of the concentration-time curves.

Other pharmacokinetic parameters were estimated noncompartmentally. The elimination t1/2 (t1/2el) was determined by the ratio ln2/λ, where λ is the negative slope of the linear terminal phase of the log concentration-time curve. The AUC was determined according to the trapezoidal method. The AUC from 0 h to infinity (AUC0–∞) was calculated by adding C/λ, where C is estimated by applying the last time in the regression equation line to the AUC until the last time point. CLT was derived from the dose over the AUC0–∞. The apparent V was estimated from the dose divided by the product of the AUC0–∞ and λ. Following oral dosing, CLT/F and V/F were determined.

(ii) Urinary data.

CLR was calculated from the total amount of unchanged drug eliminated in urine from 0 to 24 h divided by the AUC from 0 to 24 h. Nonrenal clearance (CLNR) was obtained by substracting the CLR from the CLT.

(iii) Population pharmacokinetic analysis.

Pharmacokinetic calculations were done with P-Pharm software (Simed), which relies on an iterative two-stage method (14).

Since intravenous and oral data were obtained for different animals, F could not be estimated by the ratio of the AUC0–∞ obtained after oral and that obtained after parenteral dosing. Therefore, individual F estimates were obtained by nonlinear mixed-effect modeling (19).

A bicompartmental model was fitted to the concentration in plasma-time data of the 28 animals simultaneously. The model was written as the usual integrated equation (28). Residual errors between observed and predicted concentrations were assumed to be normally distributed, with a mean of 0 and a variance proportional to the concentration. Interindividual variability was taken into account by assuming that individual parameters arose from a multivariate normal distribution, with means and variances being estimated. Covariances between parameters were fixed at 0. The population model was validated by comparing the mean of the standardized residuals to 0 and by assessing whether their distribution was normal (Kolmogorov-Smirnov test). The concentration plot of observed versus predicted data as well as individual concentration-time curves, was examined.

Pharmacokinetic estimates were obtained by a Bayesian method, the mode of posterior density (maxima a posteriori estimates). Estimated pharmacokinetic parameters were the elimination CL, the V of the central compartment, the t1/2 of the first and second decay phases, and, when relevant, the rate constant of ciprofloxacin absorption (Ka) and the F.

Statistical analysis.

Following oral or parenteral administration, noncompartmentally derived pharmacokinetic parameters obtained from control and RF rats were compared by a nonparametric Mann-Whitney test. The level of statistical significance was fixed at 5%.

Differences between mean values obtained for RF versus normal rats were assessed by a one-way analysis of variance based on estimates derived by the mode of posterior density. Pharmacokinetic parameter values were tentatively correlated with renal function, i.e., with the inverse of plasma creatinine levels (1/CRs). A linear model was used, and the significance of the correlation was assessed by analysis of variance.

RESULTS

Compared to control rats, nephrectomized rats had significantly higher concentrations of creatinine in serum (127.75 ± 15.4 versus 62.7 ± 17.4 μmol/liter, P < 0.001). They also had a significantly reduced CLCR (0.24 ± 0.06 versus 1.5 ± 0.45 ml/min, P < 0.001).

Parenteral administration.

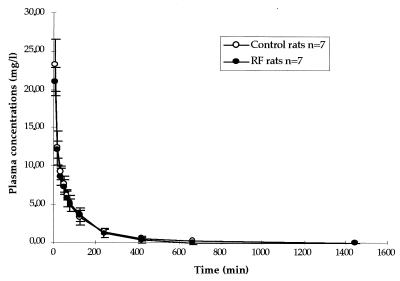

Concentration in plasma-time curves are presented in Fig. 1, and ciprofloxacin pharmacokinetic parameters derived from data for normal and RF rats are compared in Tables 1 and 2. Apart from CLR (Table 2), which was significantly reduced in nephrectomized rats, there was no significant difference in ciprofloxacin pharmacokinetics between the two groups.

FIG. 1.

Mean concentrations ± standard deviations in plasma versus time curves following the parenteral administration of a 50-mg/kg dose of ciprofloxacin.

TABLE 1.

Means for pharmacokinetic parameters following the parenteral and oral administration of a 50-mg/kg dose of ciprofloxacin

| Mode of administration | Type of ratsa | Mean ± SD (median) for pharmacokinetic parameterb:

|

|||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| t1/2el (min) | AUC0–∞ (mg · min/liter) | V (liter/kg) | V/F (liter/kg) | CLT (ml/min/kg) | CLT/F (ml/min/kg) | Cmax (mg/liter) | Tmax (min)c | ||

| Parenteral | Control | 102.3 ± 26.2 (96.7) | 1,565.8 ± 340.5 (1,565) | 9.2 ± 3.3 (7.8) | 33 ± 7 (32) | ||||

| RF | 92.2 ± 13.15 (91.6) | 1,423.8 ± 262.7 (1,321) | 11.3 ± 4.5 (12.1) | 36 ± 6 (38) | |||||

| Oral | Control | 98.2 ± 30.7 (94.2) | 271.3 ± 14.3 (264.4) | 43.4 ± 6.3 (42) | 185 ± 9 (188) | 1.6 ± 0.6 (1.4) | 35.8 ± 24.3 (34.2) | ||

| RF | 105.0 ± 18.2 (106.0) | 436.3 ± 90.5 (418.8)* | 27.4 ± 7.0 (26.5)* | 117 ± 25 (119)* | 2.3 ± 0.5 (2.4)** | 29.3 ± 17.5 (29.1) | |||

In each group, the number of control rats was seven and the number of rats with RF was seven.

*, P < 0.01 compared with the control; **, P < 0.05 compared with the control. All other P values were not significantly different.

Tmax, time needed to reach Cmax.

TABLE 2.

Means of CLR and CLNR following the parenteral and oral administration of a 50-mg/kg dose of ciprofloxacin

| Mode of administration | Type of rats | Mean ± SD (median) for pharmacokinetic parametera:

|

|

|---|---|---|---|

| CLR (ml/min/kg) | CLNR (ml/min/kg) | ||

| Parenteral | Control | 17.8 ± 4.7 (17.9) | 15.0 ± 5.0 (16.5) |

| RF | 5.3 ± 1.4 (4.9) | 32.0 ± 4.0 (30.9) | |

| Oral | Control | 22.6 ± 5.3 (23.2) | |

| RF | 6.8 ± 4.4 (6.2) | ||

All P values were less than 0.01.

Oral administration.

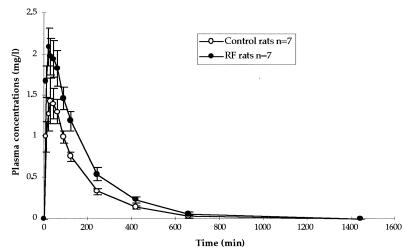

In nephrectomized rats, ciprofloxacin concentrations in plasma were higher than in control rats (Fig. 2), leading to significantly higher values of AUC0–∞.

FIG. 2.

Mean concentrations ± standard errors in plasma versus time curves following the oral administration of a 50-mg/kg dose of ciprofloxacin.

As a result, V/F and CLT/F values were significantly lower while the t1/2el remained unchanged (Table 1). Nephrectomized rats also had significantly lower values of CLR (Table 2).

Oral versus parenteral administration.

Mean population estimates of CL (34 ml/min/kg), V of the central compartment (1.4 liter/kg), t1/2 of the first decay phase (5.6 min), and t1/2 of the second decay phase (96 min) did not evidence any differences between RF and control rats. In contrast, Ka and F values were best described by two mean values: both were significantly higher for RF rats than for control rats (0.034 versus 0.023 min−1 [P < 0.001] and 0.24 versus 0.17 [P < 0.001]), respectively. Among the six estimated pharmacokinetic parameters, only F was significantly correlated with the covariate 1/CR (r2 = 0.73). Therefore, 73% of the variability in F could be explained by the variability in CR.

DISCUSSION

Despite producing a marked decrease in CLCR, RF does not alter the pharmacokinetic profile of ciprofloxacin administered parenterally. The increase in CLNR suggests the existence of compensatory mechanisms of elimination when renal function is compromised. Nonrenal elimination could be increased via modifications in hepatic metabolism or intestinal elimination, i.e., via alterations in biliary excretion or intestinal secretion.

In RF, alterations in drug metabolism depend on the selected molecule. Investigations of conjugation reactions in bilaterally nephrectomized rats evidenced increases in UDP-glucuronosyl transferase activity (suggesting that toxic phenols do not accumulate in RF) (8). However, in human, metabolism plays only a minor role in ciprofloxacin elimination (1, 5).

Following intravenous administration of drug (5 mg/kg), Siefert et al. (20) showed that ciprofloxacin urinary excretion accounted for 51% of the total elimination, compared to 47% for fecal excretion, and they recovered minor quantities of metabolites (5%). Using an ex vivo intestinal perfusion rat model, Rubinstein et al. (18) evidenced the importance of intestinal elimination in the disposition of ciprofloxacin. With the same model, we showed that in RF rats, ciprofloxacin intestinal secretion was increased without any modification in biliary elimination (unpublished data). The increased CLNR of ciprofloxacin in rats suffering from RF may be therefore due to an increase in its intestinal secretion. These results confirm what has been found for humans (16).

In contrast, RF does modify the pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin administered orally, leading to substantially higher concentrations in the plasma of rats suffering from RF than in controls. This increase in concentrations in plasma led to increases in AUC, decreases in apparent V/F, and reductions in CLT/F. However, the ciprofloxacin t1/2el were identical between RF and control rats. When results are compared to those obtained following parenteral administration of ciprofloxacin (i.e., unchanged V and CL), one can suggest an increased F of the drug in rats suffering from RF. The increased F of ciprofloxacin in rats with RF was confirmed by nonlinear mixed-effect modeling, which also demonstrated an increased rate of absorption.

Factors which may influence ciprofloxacin F in RF include an increase in its absorption and a decrease in its hepatic first-pass effect.

For rats and humans, ciprofloxacin has a low hepatic extraction coefficient and is only slightly bound to plasma proteins (30%) (20, 22, 23, 27). Hence, its metabolism is expected to be governed mostly by the enzymatic capacity of the liver (22). Since RF has been associated with reductions in human hepatic oxidative systems, ciprofloxacin F may be proportionally increased (3, 8, 10). However, if ciprofloxacin metabolism decreases, then differences in AUC would be observed between control and RF rats following parenteral administration of ciprofloxacin.

Drug absorption depends on numerous factors, such as intestinal residence times, intestinal motility, blood flow, intestinal mucosa integrity, lumen pH, and the drug liposolubility. The absorption rate and the amount of ciprofloxacin absorbed via the gut have never been investigated for rats suffering from RF. However, Magnusson et al. (13) evidenced that in rats, chronic RF induces changes in intestinal mucosa that lead to an increased intestinal permeability towards polar drugs via an increased water absorption. The increase in ciprofloxacin Ka is consistent with the hypothesis of increased permeability of the small intestines of nephrectomized rats.

For lipophilic or neutral molecules, drug transport across the intestinal membrane occurs primarily through passive diffusion. The main sites of ciprofloxacin intestinal absorption are the duodenum and the proximal jejunum (5, 11). In the duodenum, pH varies between 5 and 7, while in the jejunum and the ileum it is more than 7. RF-induced elevations in intestinal pH may yield to increased proportions of electrically neutral zwitterionic species (pH is 7.4 at the isoelectric point [22, 26]), thereby increasing ciprofloxacin lipophilicity and its intestinal absorption.

In conclusion, in rats, RF increases the CLNR and the F of ciprofloxacin. The exact mechanisms underlying these observations have not been elucidated and are under investigation.

REFERENCES

- 1.Bergan T. Pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin with reference to other fluorinated quinolones. J Chemother. 1989;1:10–17. doi: 10.1080/1120009x.1989.11738857. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Bergan T, Thorsteinsson S B, Rohwedder R, Scholl H. Elimination of ciprofloxacin and three major metabolites and consequences of reduced renal failure. Chemotherapy. 1989;35:393–405. doi: 10.1159/000238702. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Bianchetti G, Graziani G, Brancaccio D, Morganti A, Leonetti G, Manfrin M, Sega R, Gomeni R, Ponticelli C, Morselli P L. Pharmacokinetics and effects of propranolol in terminal uraemic patients and in patients undergoing regular dialysis treatment. Clin Pharm. 1976;1:373–384. doi: 10.2165/00003088-197601050-00004. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Burtin M, Laouari D, Kindermans C, Kleinknecht C. Glomerular response to acute protein load is not blunted by high-protein diet or nephron reduction. Am J Physiol. 1994;266:F746–F755. doi: 10.1152/ajprenal.1994.266.5.F746. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Campoli-Richards D M, Monk J P, Price A, Benfield P, Todd P A, Ward A. Ciprofloxacin: a review of its antibacterial activity, pharmacokinetic properties and therapeutic use. Drugs. 1988;35:373–447. doi: 10.2165/00003495-198835040-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Dirksen M S C, Vree T B. Pharmacokinetics of intravenously administered ciprofloxacin in intensive care patients with acute renal failure. Pharm Weekbl [Sci] 1986;8:35–39. doi: 10.1007/BF01975477. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Drusano G L, Weir M, Forrest A, Plaisance K, Emm T, Standiford H C. Pharmacokinetics of intravenously administered ciprofloxacin in patients with various degrees of renal function. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:860–864. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.6.860. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 8.Elston A C, Bayliss M K, Park G R. Effect of renal failure on drug metabolism by the liver. Br J Anaesth. 1993;71:282–290. doi: 10.1093/bja/71.2.282. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Gasser T C, Ebert S C, Graversen P H, Madsen P O. Ciprofloxacin pharmacokinetics in patients with normal and impaired renal function. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1987;31:709–712. doi: 10.1128/aac.31.5.709. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Gibson T P, Giacomini K M, Briggs W A, Whitman W, Levy G. Propoxyphene and norpropoxyphene plasma concentrations in the anephric patient. Clin Pharmacol Ther. 1980;27:665–670. doi: 10.1038/clpt.1980.94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Harder S, Fuhr U, Beermann D, Staib A H. Ciprofloxacin absorption in different regions of the human gastrointestinal tract. Investigations with the hf-capsule. Br J Clin Pharmacol. 1990;30:35–39. doi: 10.1111/j.1365-2125.1990.tb03740.x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Kowalsky S F, Echols M, Schwartz M T, Bailie G R, McCormick E. Pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin in subjects with varying degrees of renal function and ondergoing hemodialysis or CAPD. Clin Nephrol. 1993;39:53–58. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Magnusson M, Magnusson K-E, Sundqvist T, Denneberg T. Reduced intestinal permeability measured by differently sized polyethylene glycols in acute uremic rats. Nephron. 1992;60:193–198. doi: 10.1159/000186738. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Mentre F, Gomeni R. A two-step iterative algorithm for estimation in nonlinear mixed-effect models with an evaluation in population pharmacokinetics. J Biopharm Stat. 1995;5:141–158. doi: 10.1080/10543409508835104. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Parry M F, Smego D A, Digiovanni M A. Hepatobiliary kinetics and excretion of ciprofloxacin. Antimicrob Agents Chemother. 1988;32:982–985. doi: 10.1128/aac.32.7.982. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Rohwedder R, Bergan T, Thorsteinsson S B, Scholl H. Transintestinal elimination of ciprofloxacin. Chemotherapy. 1990;36:77–84. doi: 10.1159/000238751. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.von Rosenstiel N, Adam D. Quinolone antibacterials: an uptake of their pharmacology and therapeutic use. Drugs. 1994;47:872–901. doi: 10.2165/00003495-199447060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Rubinstein E, St. Julien L, Ramon J, Dautrey S, Farinotti R, Huneau J F, Carbon C. The intestinal elimination of ciprofloxacin in the rat. J Infect Dis. 1994;169:218–221. doi: 10.1093/infdis/169.1.218. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Sheiner L B, Ludden T M. Population pharmacokinetics/pharmacodynamics. Annu Rev Pharmacol Toxicol. 1992;32:185–209. doi: 10.1146/annurev.pa.32.040192.001153. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Siefert H M, Maruhn D, Maul W, Förster D, Ritter W. Pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin. 1st communication: absorption, concentrations in plasma, metabolism and excretion after a single administration of [14C]ciprofloxacin in albino rats and rhesus monkey. Arzneim-Forsch. 1986;36:1496–1502. [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Singlas E, Taburet A M, Landru I, Albin H, Ryckelink J P. Pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin tablets in renal failure. Influence of haemodialysis. Eur J Clin Pharmacol. 1987;31:589–593. doi: 10.1007/BF00606636. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Sörgel, F. 1989. Metabolism of gyrase inhibitors. Rev. Infect. Dis. 11(Suppl. 5):1119–1129. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 23.Sörgel, F., G. Naber, U. Jaedhe, A. Reiter, R. Seelmann, and G. Sigl. 1989. Brief report: gastrointestinal secretion of ciprofloxacin. Am. J. Med. 87(Suppl. 5A):S62–S65. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 24.Sörgel, F., and M. Kinzig. 1993. Pharmacokinetics of gyrase inhibitors, part 1: basic chemistry and gastrointestinal disposition. Am. J. Med. 94(Suppl. 3A):44S–55S. [PubMed]

- 25.Sörgel, F., and M. Kinzig. 1993. Pharmacokinetics of gyrase inhibitors, part 2: renal and hepatic elimination pathways and drug interactions. Am. J. Med. 94(Suppl. 3A):56S–69S. [PubMed]

- 26.Takacs-Novak K, Noszal B, Hercmecz I, Kereszturi G, Podanyi B, Szasz G. Protonation equilibria of quinolone antibacterials. J Pharm Sci. 1990;79:1023–1028. doi: 10.1002/jps.2600791116. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Vance-Bryan K, Guay D R P, Rotschafer J C. Clinical pharmacokinetics of ciprofloxacin. Clin Pharmacokinet. 1990;19:434–461. doi: 10.2165/00003088-199019060-00003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Wagner J G. Pharmacokinetics for the pharmaceutical scientist. Lancaster, Pa: Tecnomic Publishing; 1993. pp. 1–313. [Google Scholar]