Abstract

In Parkinson’s disease, pathogenic factors such as the intraneuronal accumulation of the protein α-synuclein affect key metabolic processes. New approaches are required to understand how metabolic dysregulations cause degeneration of vulnerable subtypes of neurons in the brain. Here, we apply correlative electron microscopy and NanoSIMS isotopic imaging to map and quantify 13C enrichments in dopaminergic neurons at the subcellular level after pulse-chase administration of 13C-labeled glucose. To model a condition leading to neurodegeneration in Parkinson’s disease, human α-synuclein was unilaterally overexpressed in the substantia nigra of one brain hemisphere in rats. When comparing neurons overexpressing α-synuclein to those located in the control hemisphere, the carbon anabolism and turnover rates revealed metabolic anomalies in specific neuronal compartments and organelles. Overexpression of α-synuclein enhanced the overall carbon turnover in nigral neurons, despite a lower relative incorporation of carbon inside the nucleus. Furthermore, mitochondria and Golgi apparatus showed metabolic defects consistent with the effects of α-synuclein on inter-organellar communication. By revealing changes in the kinetics of carbon anabolism and turnover at the subcellular level, this approach can be used to explore how neurodegeneration unfolds in specific subpopulations of neurons.

Supplementary Information

The online version contains supplementary material available at 10.1186/s40478-023-01608-8.

Keywords: Parkinson’s disease, Rodent model, Substantia nigra, Alpha-synuclein, Glucose metabolism, NanoSIMS, SILK-SIMS

Introduction

Parkinson’s disease (PD) is a progressive neurodegenerative disease that affects the function and survival of neuronal populations in various brain regions, with a pattern reflecting the selective vulnerability of different neuron subtypes. In the basal ganglia, dopaminergic neurons located in the substantia nigra pars compacta (SNpc) are among the neuronal subtypes that are most vulnerable to the disease. Furthermore, the loss of nigrostriatal dopaminergic innervation is the main cause of the motor symptoms that characterize PD.

Idiopathic PD is a multifactorial disease linked to genetics, the environment, and aging. Although the cause of sporadic PD remains poorly understood, the identification of genetic factors associated with familial forms of the disease, such as multiplication of the SNCA gene, together with the presence of Lewy bodies containing α-synuclein (α-syn) fibrils, point to α-syn accumulation, misfolding and aggregation as a core mechanism in PD pathogenesis. Alpha-syn dyshomeostasis is known to profoundly affect the metabolic activity and function of neurons via a plethora of cellular mechanisms. When aberrantly localized in the neuronal cell body, α-syn interacts with multiple membranous organelles and thereby affects inter-organellar communication and cellular trafficking [3, 28, 47]. In pathogenic conditions, α-syn impairs mitochondrial function [13] as well as vesicle trafficking in the secretory pathway [20] via inhibition of vesicle transfer from the endoplasmic reticulum (ER) to Golgi apparatus [11]. Alpha-syn also affects the function of autophagosomes and autolysosomes [33, 34]. Ultimately, the deposition of α-syn fibrils into Lewy bodies leads to organelle sequestration, further compromising cellular functions [32, 48]. Other mechanisms, such as the α-syn-induced impairment of ER-mitochondria signaling, have recently been highlighted [21]. However, it remains unclear how these defects affect core cellular functions to progressively lead to the degeneration of vulnerable neuronal subtypes as observed in PD. Notably, little is known about associated pathological changes in cell metabolism at the level of neuronal compartments and key organelles.

Identifying brain metabolic defects at subcellular level in vivo requires dedicated techniques. One such technique combines stable isotope labeling kinetics with secondary ion mass spectrometry (SILK-SIMS) [41]. The NanoSIMS is an ion microprobe instrument capable of imaging and quantifying elemental and isotopic variations in biological tissues with about 100 nm lateral resolution, following sample preparation similar to that required for electron microscopy [27, 38]. The resulting isotope maps can be precisely correlated with scanning electron microscopy (SEM) images of cellular ultrastructure allowing quantification of the isotopic composition at a level of subcellular compartments such as the nucleus, nucleolus, mitochondria, and Golgi apparatus. Combined with stable isotope labeling experiments using, e.g., mice and rats, the correlative NanoSIMS and SEM imaging has proven an efficient method to study metabolic turnover of brain tissue in normal homeostasis, as well as in brain disease models [7, 30, 31, 35, 51, 52].

The aim of the present study was to develop a method to gain new insights into α-syn-induced pathological changes in cell metabolism at the level of compartments and organelles within nigral dopaminergic neurons. To this end, we combined a 13C-glucose pulse-chase experiment with correlative SEM and NanoSIMS imaging and quantified the effects of α-syn overexpression on anabolic incorporation and turnover of glucose-derived carbon in major compartments of the neuronal cell body (cytoplasmic versus nuclear), as well as in specific organelles (mitochondria, Golgi apparatus and lysosomes). Our data revealed specific changes in 13C enrichments in nigral neurons following α-syn overexpression compared with their healthy counterparts: neuronal cell bodies exhibited increased overall carbon turnover, with a decrease in relative carbon incorporation in the nuclear compartment. At the level of organelles, we observed a lower carbon incorporation in the mitochondria as well as lower carbon turnover in the secretory Golgi apparatus.

Materials and methods

Rat model of Parkinson’s disease

To induce pathogenic α-syn overexpression in the ventral midbrain, 11 rats were injected in the SN with serotype 6 adeno-associated viral (AAV) vectors coding for the human wild-type α-syn protein (nucleotides 46–520, NM_000345), as previously described [5]. In this vector, the expression of the human α-syn protein is under the control of the mouse phosphoglycerate kinase 1 (pgk1) constitutive promoter (AAV2/6-pgk1:β-globin-intron:α-syn:WPRE). The coordinates used for stereotactic injection were: − 5.2 mm (anteroposterior), − 2 mm (mediolateral), − 7.8 mm (dorsoventral, relative to skull surface), − 3.3 mm (tooth bar). Viral vectors were produced and titrated as previously described [16]. Briefly, relative AAV infectivity was determined by real-time PCR (rtPCR) quantification of double-stranded vector genomes present in total DNA isolated from HEK293 cells, 48 h post-transduction. The infectivity rate expressed in ‘transducing units’ (TU) was calculated according to a known infectivity of a standard virus encoding GFP (AAV2/6-cmv-eGFP), whose titer was estimated via flow cytometry in similar conditions. Both the vector expressing α-syn (AAV-α-syn) and the control non-coding vector were used at a total injected dose of 1.5 × 107 TU in a volume of 2 µL. The AAV-α-syn vector was injected in the right hemisphere and the control vector in the left hemisphere of the same animal.

Animal handling and experimentation used in this study were performed according to the Swiss legislation and the European Community Council directive (86/609/EEC) for the care and use of laboratory animals. The protocol was approved by the local ethics committee and by the veterinary authorities. The experiments were performed using adult female Sprague–Dawley rats (Janvier) weighing around 200 g. During the whole experiment, the animals were maintained on 12 h light–dark cycle and fed ad libitum with standard chow. Animals were maintained in standard housing conditions for a period of 30 days post-injection until α-syn overexpression induced degenerative effects. At that time, the animals were subjected to labelling with uniformly 13C-labeled glucose, as detailed below. Animals were sacrificed and brain tissues were subsequently processed for SEM and NanoSIMS analyses.

13C glucose labelling

During the pulse phase starting 30 days post-vector injection, 5% (w/v) 13C-labeled glucose (D-Glucose-13C6, 13C atom fraction of 99%, Sigma-Aldrich, Switzerland) was added to the drinking water. The amount of glucose-supplemented water ingested by each individual rat was regularly measured (every 12 h) and was found to be very similar among animals (58.3 ± 2.0 mL per day), also when taking into account body weight. Animals were initially divided into 3 groups containing 3–4 animals per group based on the 13C pulse-chase protocol. Groups 1 and 2 ingested the 13C labeled glucose for 24 h and 48 h before sacrifice, respectively (pulse phase), whereas Group 3 first ingested 13C labeled glucose for 48 h, followed by ingestion of isotopically normal glucose (added at a concentration of 5% (w/v) in drinking water) for additional 48 h (chase phase), after which they were sacrificed for analysis (Fig. 1a). Group 3 contained only 3 rats after one animal died during stereotaxic surgery.

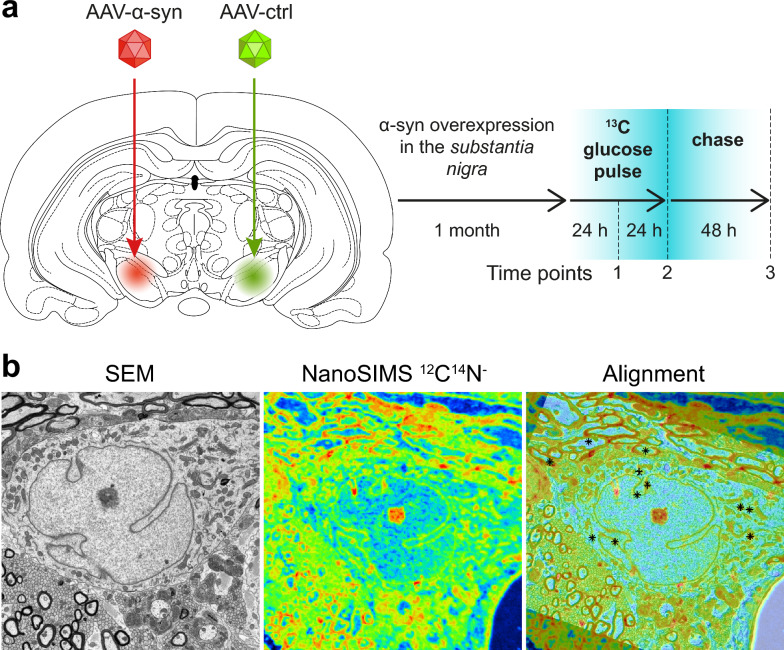

Fig. 1.

SILK-SIMS measurement of 13C labeling in a model of induced α-syn overexpression. a Pathogenic conditions were induced in the rat ventral midbrain by unilateral AAV-mediated α-syn overexpression for one month. Subsequently, the animal was subjected to a 48 h pulse with 13C-labeled glucose administered in the drinking water. The effects of α-syn overexpression on the kinetics of 13C incorporation were determined by comparing the brain hemisphere injected with AAV6-α-syn with the control hemisphere injected with a non-coding AAV6 vector. b Representative example showing how the SEM ultrastructure image was aligned with the isotopic image measured by NanoSIMS. Note that the NanoSIMS image was rotated relative to the SEM image and acquired with a lower lateral resolution (about 15-fold). Additionally, the NanoSIMS image was slightly distorted (stretched or squeezed) relative to the SEM image because of the movement of the sample stage caused by temperature variations during the relatively long NanoSIMS measurement. The alignment of the two images was done by matching the locations of multiple reference points manually defined by the user. In the ‘alignment’ image, points indicated by ‘ + ’ and ‘✕’ were defined in the SEM and NanoSIMS image, respectively. Superimposed reference points are indicated with ❊.

Tissue preparation

At each sampling time point, animals were deeply anaesthetized via inhalation of isofluorane, and, as soon as the breathing stopped, they were immediately perfused via the heart with 10 mL of isotonic PBS at the speed of 60 mL/min, followed with 300 mL of a buffered mixture of 2.5% glutaraldehyde and 2% paraformaldehyde (0.1 M phosphate buffer (PB), pH 7.4). After the perfusion was complete the animal was left for 2 h. The brain was then removed from the skull and 80 µm thick, coronal sections were cut through the frontal striatum and the SN regions using a vibratome (Leica VT1200S; Leica Microsystems, Vienna, Austria).

The vibratome sections were washed in cacodylate buffer (0.1 M, pH 7.4) and then stained with 1% osmium tetroxide and 1.5% potassium ferrocyanide for 40 min. This was immediately followed by further staining in 1% osmium tetroxide alone for another 40 min. After washing in double-distilled water, the sections were stained again with 1% aqueous uranyl acetate for 40 min. Then, the sections were dehydrated in graded alcohol series (2 × 50% ethanol, 1 × 70%, 1 × 90%, 1 × 95%, 2 × 100%: 3 min each change), and gradually infiltrated with Durcupan resin (Fluka, Buchs, Switzerland) in ethanol at 1:2, 1:1 and 2:1 ratios for 30 min each. Finally, the sections were infiltrated twice with pure Durcupan resin for 2 × 30 min followed by fresh Durcupan for 4 h. The sections were flat embedded between glass slides in fresh resin and polymerized for at least 24 h inside an oven set at 65 °C.

Sample preparation for histology and SEM imaging

Once the resin had hardened, the region of striatum and substantia nigra (A9 region) from both the left (injected with the control non-coding vector) and right (injected with AAV-α-syn) hemispheres were identified according to the rat brain atlas (Paxinos and Watson, 1996), cut out and glued with acrylic cement onto a resin block. Then, 0.5 µm semithin sections were cut using an ultramicrotome (Leica UC6, Leica Microsystems, Vienna, Austria) equipped with a diamond knife (Diatome, Switzerland). These sections were collected onto round silicon wafers (10 mm diameter) and lightly gold-coated (a few nm thickness). These sections were used for SEM and NanoSIMS imaging. Neuronal bodies in the pars compacta of the SN were imaged with a Zeiss Gemini 500 Field Emission Scanning Electron Microscope (Zeiss, Oberkochen, Germany). Micrographs (4096 × 3072 pixels) were recorded by using an in-lens energy selective backscatter detector (EsB) designed to enhance material contrast at low-kV imaging. The backscattered electrons were energy filtered with the EsB grid in front of the detector tuned to 1500 V and the accelerating voltage was 3 kV. The micrographs were recorded with inverted contrast directly. SEM images of individual neurons were used to analyze the aspect ratios of mitochondria (length-over-width) as well as the frequency of the observed contacts between the mitochondrial outer membrane and the ER (MERC) using the Fiji software.

For the images of the striatum and SNpc (examples shown in Fig. 2), semi-thin sections were stained with 1% toluidine blue stain, and imaged using a light microscope (Nikon) equipped with a 20× objective (Olympus AX70). These sections were subsequently imaged by NanoSIMS as described below. Other NanoSIMS imaging was performed on semi-thin sections placed on silicon wafers.

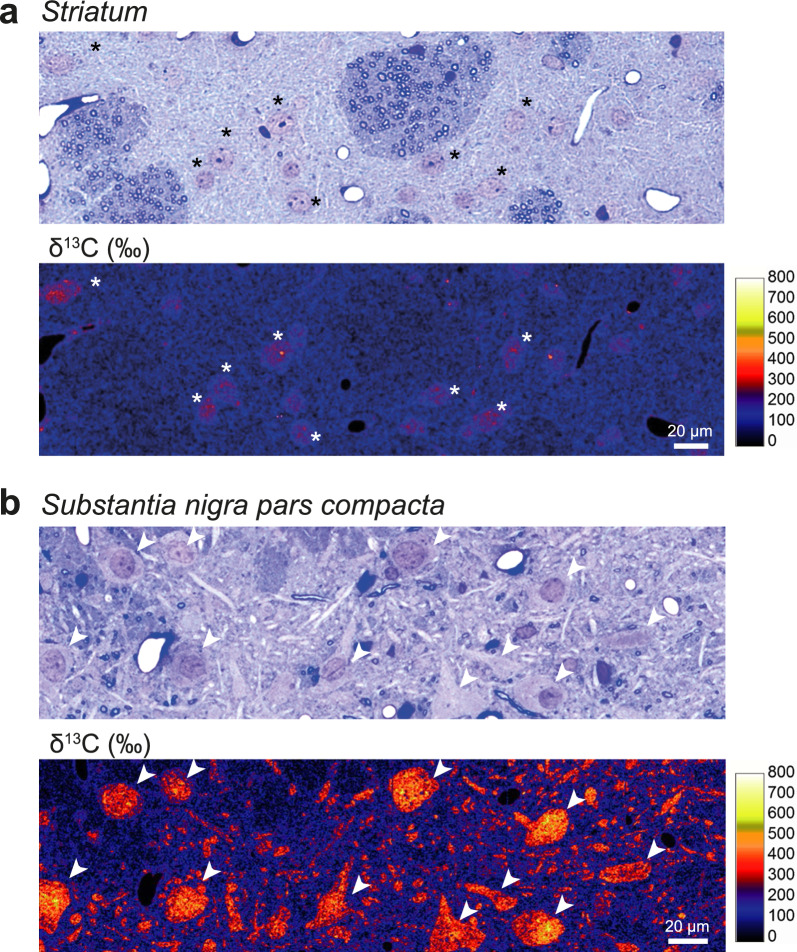

Fig. 2.

Carbon isotope labelling in the brain following 48 h pulse with 13C-labeled glucose: comparison of the striatum and substantia nigra pars compacta. a Representative light microscopy image of the striatal tissue showing a toluidine blue-stained semi-thin section (upper panel), adjacent to a map of 13C isotope enrichment in the same brain region (lower panel). Note the weak 13C labeling mainly present in neuronal cell bodies (*). b Representative light microscopy image of the substantia nigra pars compacta showing large neuronal cell bodies and neurites with intense 13C enrichment (arrowheads). To facilitate direct comparison, the same color-coded δ13C (‰) intensity scale is applied in (a) and (b). Scale bars: 20 µm

NanoSIMS isotopic imaging

To quantify the 13C enrichment in neuronal bodies with a subcellular resolution and correlate it with the ultrastructure information gained via SEM, the exact same regions were imaged with a NanoSIMS 50L ion microprobe using Cs+ primary ion beam. After SEM imaging and prior to NanoSIMS analysis, the same silicon wafers containing sections were coated with an additional 10–15 nm of gold. Following pre-sputtering for 5 min with a primary beam of about 10 pA to remove the metal coating, the beam was focused to a spot size of about 150 nm (1–3 pA) and rastered across an area of typically 50 × 50 µm2 (256 × 256 pixels) with a pixel dwell time of 5 ms. Secondary ions 12C14N− and 13C14N− (that yielded the highest count rates) were counted simultaneously (multi-collection) in electron multipliers at a mass resolution sufficient to avoid all potentially problematic mass-interferences [51, 52]. The rastering was repeated up to 15 times over the same area to increase the overall ion counts and thus improve the precision of the 13C enrichment quantification. For higher resolution imaging, the primary beam was focused to about 100 nm and images of regions 20 × 20 µm2 (256 × 256 pixels) in size were obtained with the raster repeated 10 times.

NanoSIMS data processing

NanoSIMS data were processed using the L’IMAGE® software (Larry R. Nittler, Carnegie Institution of Washington, Washington, DC, USA). First, individual ion count images acquired during each raster were aligned and accumulated. Subsequently, images of the 13C/12C isotope ratio were obtained by taking the ratio between the accumulated 13C14N− and 12C14N− ion count images. The 13C enrichment is reported in the δ notation, as parts per thousand deviation from the 13C14N−/12C14N− ratio measured on similar brain tissues with a natural carbon isotopic composition:

where Rmes and Rnat are the 13C14N−/12C14N− ratios measured in samples obtained from experiments with 13C-labeled and 13C-unlabelled (natural) glucose, respectively, both prepared and analyzed under identical conditions.

NanoSIMS data were additionally processed with the Look@NanoSIMS software [39], which was modified to allow precise alignment of the ultra-high resolution SEM image and the corresponding NanoSIMS image and thus extract the isotopic compositions of small structures that are not identifiable solely based on the NanoSIMS image. Steps required to perform this analysis, which involve resampling of the NanoSIMS image, alignment with the SEM image, drawing of ROIs based on the SEM image, and quantification of secondary ion counts and ion count ratios in these ROIs mapped to the original NanoSIMS image, are described in detail in the Additional file 1.

Statistical analysis

Statistical analyses were performed with the GraphPad Prism software. Numerical data are reported as mean ± SD. Violin plots of numerical data show the median as well as upper and lower quartiles. The statistical tests as well as the number of replicates are indicated in the figure legends. A non-parametric Mann–Whitney test was applied to data sets for which the distribution of the values did not pass normality testing. The α level of significance was set at 0.05.

Results

Metabolism and turnover of macromolecules and organelles within tissues can be explored using techniques based on the incorporation of stable isotopes. In particular, the anabolic metabolism of 13C-labeled glucose leads to the production of metabolites incorporated into proteins, lipids, and nucleic acids, i.e., the building blocks of the supramolecular cellular structures. In the central nervous system, 13C-labeling in neurons following administration of 13C glucose on the time scale of hours and days can be detected using NanoSIMS imaging in aldehyde-fixed brain tissues [51]. Here, we investigated the incorporation and turnover of glucose-derived carbon in specific sub-populations of neurons in the adult rat brain following a pulse-chase experiment with 13C-labeled glucose (Fig. 1). In particular, we applied this approach to an animal model of PD based on human wild-type α-syn overexpression, to explore how the pathogenic accumulation of this protein affects carbon metabolism in nigral neurons at subcellular level.

Local overexpression of the human α-syn protein in the rat ventral midbrain was induced by unilaterally injecting an AAV6-α-syn vector in the SN of adult rats (Fig. 1a). In this model system, the overexpression of human α-syn was confined to the injected hemisphere and the contralateral hemisphere could be used as a control to identify the effects of α-syn on glucose-derived carbon metabolism in the affected brain tissue. In order to control for potential effects of vector injection, the same dose of a non-coding AAV6 vector was injected in the contralateral hemisphere. As previously shown, overexpression of human α-syn in nigral dopaminergic neurons leads to progressive and selective degeneration of dopaminergic neurons over 1–4 months, loss of nigrostriatal dopamine innervation, and reduced dopamine release in the striatum [5, 19].

To explore the early consequences of human α-syn on 13C incorporation in neurons, we compared quantitative NanoSIMS images of 13C/12C ratios throughout a pulse-chase experiment, one month after AAV6-α-syn injection. Glucose uniformly labeled with 13C was added to the drinking water during a 48 h pulse phase. The chase period was carried out between 48 and 96 h, during which the animals received drinking water supplemented with the same concentration of isotopically normal glucose. The level of 13C enrichment was assessed in brain tissues from the striatum and the SN, at three time points: during (at 24 h; N = 3 rats) and at the end of the pulse phase (at 48 h; N = 4 rats), as well as after the chase phase (at 96 h; N = 3 rats) (Fig. 1a). At each time point, we correlated the SEM image of the ultrastructure of the brain tissue with the NanoSIMS isotopic maps (Fig. 1b). The NanoSIMS 12C14N− map (which allows identification of many subcellular structures) was first used to obtain a precise correlation between NanoSIMS and SEM images using the Look@NanoSIMS software [45], as illustrated in Fig. 1b. It was then possible to precisely map and measure 13C enrichment in the brain tissue, at both cellular and subcellular levels.

13C-labeling of neurons in the basal ganglia reveals clear differences in anabolic carbon incorporation

PD is characterized by the selective vulnerability of dopaminergic neurons located in the SNpc. As these neurons have an extremely complex axonal arborization and make numerous synaptic contacts in the striatum, it is anticipated that they have a very high metabolic turnover [6, 44]. The resulting high metabolic activity may represent a significant stress, which has been proposed to make nigral neurons particularly vulnerable to the development of PD [39, 50].

To compare the metabolic activity of two major neuron populations in the basal ganglia, we assessed the level of 13C incorporation in the striatum and SNpc at the end of the pulse phase (Fig. 2). In both brain regions, 13C accumulation was most evident in neuronal cell bodies. When comparing the striatum and the SNpc, 13C enrichment was distinctly lower in the striatum, where GABAergic medium spiny neurons represent the most abundant neuronal population, exhibiting 13C enrichment values in the range of 100–300 ‰ mainly confined to the neuronal nuclei (Fig. 2a). In contrast, 13C enrichment in the neuronal cell body was on average about 1.8-fold higher in the SNpc, primarily localized to a population of large neurons with a morphology similar to dopaminergic neurons (Fig. 2b), which represent 70% of the neurons in this brain region [15, 37]. In these neurons, 13C enrichment ranged between 200 and 500‰ distributed throughout their entire neuronal cell bodies and neurites, confirming their relatively high anabolic activity. We focused our subsequent analyses on this population of neurons, assessing the 13C enrichment in the neuronal cell bodies as well as specific cellular sub-compartments and organelles to determine the effects of human α-syn overexpression.

Alpha-synuclein overexpression enhances overall 13C turnover in nigral neurons

Large neuronal cell bodies present in the SNpc were outlined using NanoSIMS 12C14N− maps and average levels of 13C enrichment were measured within areas covering individual cell bodies from a randomly chosen population of 49–80 neurons per condition (Fig. 3). In the control condition, we observed a progressive increase in the anabolic 13C enrichment during the pulse phase, reaching on average 156 ± 22‰ and 259 ± 48‰ at 24 h and 48 h, respectively (Fig. 3a,b). At the end of the chase phase, i.e. 48 h after administration of 13C-labeled glucose was stopped and replaced by the administration of unlabeled glucose, the enrichment declined by − 40% to 156 ± 25‰ (Fig. 3a,b).

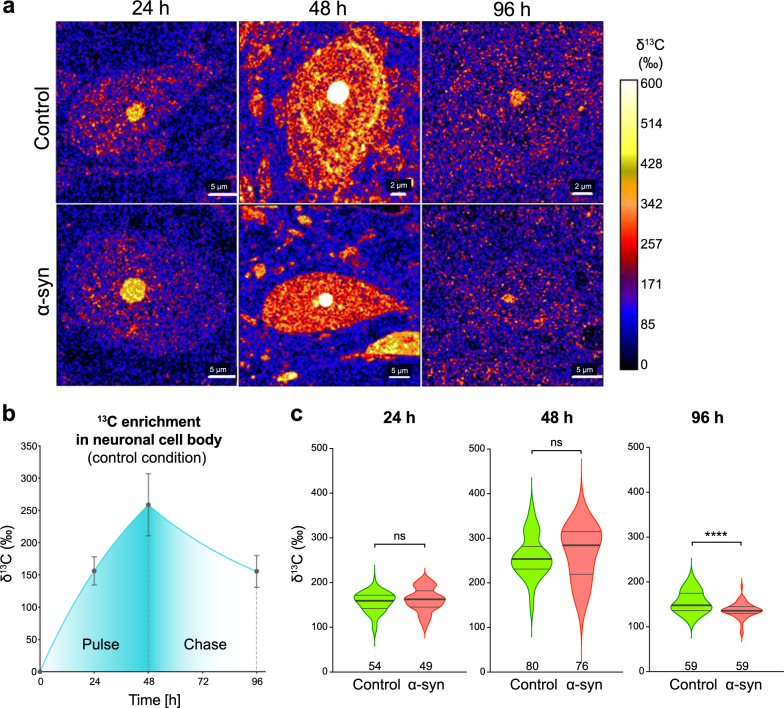

Fig. 3.

Kinetics of 13C incorporation in neuronal cell bodies in the substantia nigra pars compacta. a Representative maps of 13C isotope enrichment throughout pulse-chase experiment in neurons located in the SNpc, either in the control or AAV6-α-syn-injected SNpc. Scale bars: 2 and 5 µm. b Pulse-chase experiment: quantification of 13C enrichment in the whole cell body of nigral neurons in the SNpc injected with the non-coding control vector. Pulse phase: 13C enrichment at 24 h and 48 h after starting 13C-labeled glucose administration in the drinking water. The graph shows curve fitting with exponential plateau. Chase phase: an additional measurement was performed at 96 h and curve fitting was based on the assumption that the observed drop in 13C-enrichment follows a one-phase exponential decay. Data represent mean ± SD. c Violin plots showing 13C enrichment in the whole cell body. The graphs compare nigral neurons located in the SNpc injected with a non-coding AAV6 vector to their counterparts in the contralateral AAV6-α-syn-injected SNpc. The pulse-chase experiment was performed 30 days after intranigral vector injection. Note the effects of human α-syn overexpression on carbon turnover in the neuronal cell bodies during the chase period. The thick lines in the violin plots represent the median and the thin lines the upper and lower quartiles. The number of neurons analyzed is indicated at the bottom of the histogram bar. 24 h: N = 3 animals per group; 48 h: N = 4 animals per group; 96 h: N = 3 animals per group. Statistical analysis: multiple Mann–Whitney tests with False Discovery Rate (FDR) approach; ns = not significant; **** FDR-adjusted P < 0.0001

Next, we assessed the effects of overexpressing the human α-syn protein on the glucose-derived carbon turnover by comparing nigral neurons located in the AAV6-α-syn injected hemisphere (pathological condition) to those located in the contralateral control hemisphere (Fig. 3a,c). Overall, the level of 13C enrichment was similar for both populations of neurons during the entire pulse period, indicating that α-syn overexpression had no major effects on the overall glucose-derived carbon incorporation in neurons (Fig. 3a,c). However, a steeper decline in average 13C enrichment was observed during the chase phase (96 h time point) in the pathological condition. At the end of the chase period, 13C enrichment had declined by 49%, to an average value of 136‰, which was significantly different from the control hemisphere (Fig. 3c). NanoSIMS imaging of specific neuronal populations therefore revealed changes in the turnover of the 13C-labeled macromolecular content, which can be ascribed to α-syn-induced pathogenic conditions in the brain.

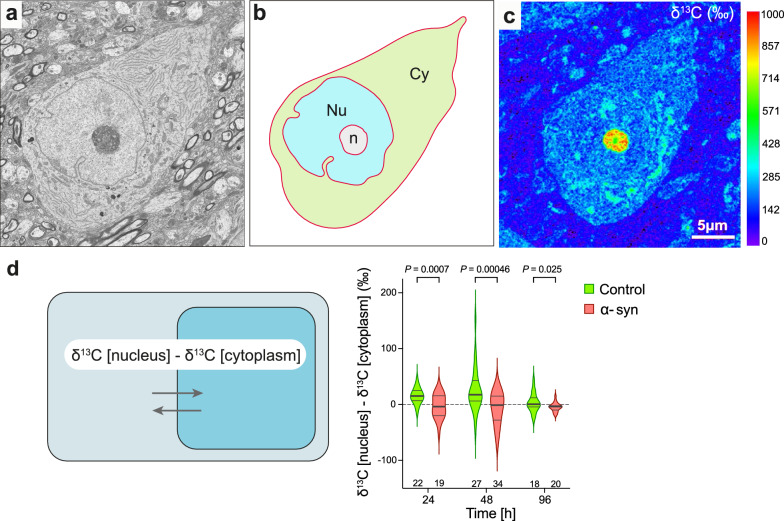

Cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments of nigral neurons are differentially affected by α-synuclein overexpression

Next, we extended our analysis to investigate the effects of α-syn overabundance in major subcellular compartments, the cytoplasm and nucleus, by correlating NanoSIMS isotopic maps with ultra-high resolution SEM images of sections of individual large-sized nigral neurons (Fig. 4a–c). The cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments were delineated in the cell body to determine their mean 13C enrichment. As the nucleoli were typically highly enriched in 13C, they strongly increased the average 13C enrichment among those individual nuclei. Therefore, if the nucleolus was visible within a cell section, the neuron was excluded from the analysis. In each neuron, the difference between 13C enrichments in the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments was determined, to normalize away potential differences in 13C incorporation observed among neurons (Fig. 4d). In the control condition, 13C enrichments in the nucleus was on average 15‰ and 25‰ higher than in the cytoplasm at the 24 and 48 h time points, respectively (Fig. 4d). Remarkably, this difference between the compartments nearly disappeared in the neurons analyzed in the pathological condition (Fig. 4d), indicating that α-syn overexpression affected the cytoplasmic versus nuclear anabolic activity. At the 96 h time point, the difference in 13C enrichment between the cytoplasm and the nucleus nearly disappeared in both the α-syn and control neurons (Fig. 4d).

Fig. 4.

Effect of human α-syn overexpression on glucose-derived carbon incorporation and turnover in the nuclear versus cytoplasmic compartment. a Representative SEM image of a large neuronal cell body located in the SNpc. b Segmentation of the SEM image into cytoplasmic (Cy), nuclear (Nu), and nucleolar (n) compartments. Outlines of the compartments were drawn manually using the Look@NanoSIMS software (see Additional file 1). c The mask generated in (b) was used to measure 13C enrichment in the nuclear versus cytoplasmic compartments in the corresponding isotopic NanoSIMS maps. Note that neurons were excluded from the analysis when the highly 13C enriched nucleolar compartment was present in the image. d The schematic illustrates the determination of the difference in 13C enrichment between the nuclear and cytoplasmic compartments. The graph compares neuronal cell bodies located in the control and α-syn-overexpressing SNpc at the 24 h, 48 h (pulse) and 96 h (chase) time points. Note the loss of nuclear glucose-derived 13C enrichment in the α-syn overexpression condition during the pulse period. The thick lines in the violin plots represent the median and the thin lines the upper and lower quartiles. The number of neurons analyzed is indicated at the bottom of the histogram bar. 24 h: N = 3 animals per group; 48 h: N = 4 animals per group; 96 h: N = 3 animals per group. Statistical analyses: multiple unpaired two-tailed t-test with False Discovery Rate (FDR) approach; FDR-adjusted P values are indicated in the graph. Scale bar: 5 µm

Correlative NanoSIMS/SEM imaging of nigral neurons revealed the kinetics of glucose-derived carbon incorporation at the level of organelles

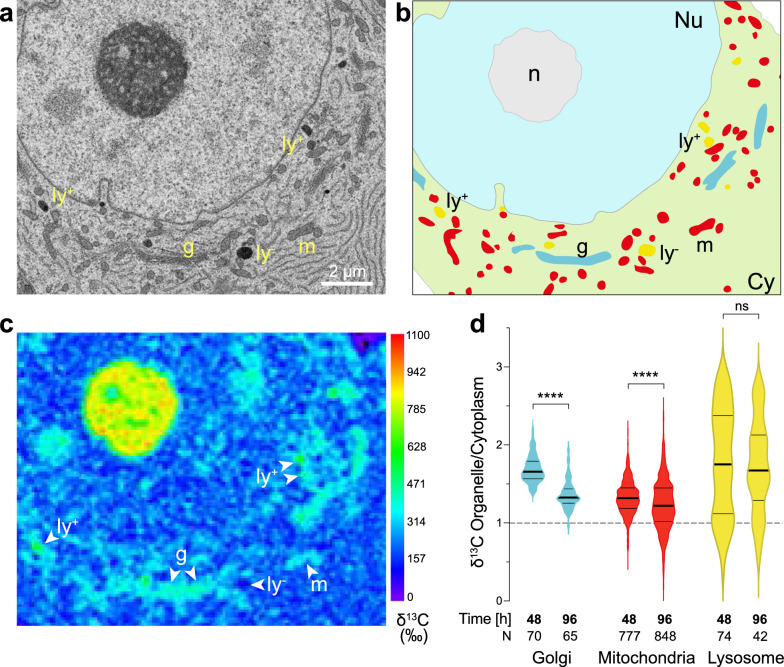

Next, SEM ultrastructural imaging was used to delineate populations of organelles in the cell body of large-sized neurons located in the control SNpc. The analysis focused on the Golgi apparatus, mitochondria, and lysosomes (Fig. 5). For each of these organelle populations, a ROI outline was generated based on the SEM image, which was then applied to the corresponding precisely aligned 13C/12C map to determine the 13C enrichment in each organelle (Fig. 5b, c). The organellar 13C enrichments were normalized to the 13C enrichment averaged throughout the entire cytoplasm visible within the imaged area of individual neurons, to assess carbon incorporation into organelles relative to the corresponding cytoplasmic 13C enrichment levels. This analysis was performed at the 48 h and 96 h time points to investigate potential differences among organelles in the control hemisphere at the end of the pulse phase and during chase (Fig. 5d). At the end of pulse, the average 13C enrichments in all organelles were higher than in the cytoplasm (+ 69% in the Golgi apparatus, + 33% in mitochondria and + 79% in lysosomes). Additionally, the labeling of individual lysosomes was highly variable within the same neuron, with some organelles displaying a threefold greater 13C enrichment relative to that of the cytoplasm, whereas in others the level of 13C enrichment remained very low, even below the average level in the cytoplasm (Fig. 5c, d). Remarkably, during the chase period, we measured the most drastic decline in cytoplasm-normalized 13C labeling in the Golgi apparatus (from 1.69 ± 0.17 at 48 h to 1.36 ± 0.18 at 96 h; Fig. 5d). This observation is consistent with the high macromolecule turnover in this organelle due to its involvement in the processing and trafficking or proteins and lipids. In mitochondria, there was also a significant decrease in cytoplasm-normalized 13C enrichment during the chase (from 1.32 ± 0.22 to 1.23 ± 0.32). In contrast, the average 13C labeling of individual lysosomes remained mostly stable over the chase period. Overall, the kinetics of incorporation and turnover of glucose-derived carbon reveals clear differences in the metabolic activity of these different organelles within neurons.

Fig. 5.

NanoSIMS analysis of 13C enrichment in specific organelles within the cell body of nigral neurons (control hemisphere). a Representative SEM image of a large neuronal cell body located in the SNpc allowed to identify three types of organelles, the mitochondria (m), the Golgi apparatus (g) and lysosomes (ly). b SEM-based segmentation of compartments and organelles in the cell body; Cy: cytoplasm; Nu: nucleus; n: nucleolus. c Corresponding map of 13C enrichment. Note the presence of both 13C-rich lysosomes (ly+) and 13C-poor lysosomes (ly−) within the same neuronal cell body. d 13C enrichment in Golgi, mitochondria and lysosomes, as compared to the cytoplasm, measured at the end of the pulse with 13C-labeled glucose (48 h time point) and after the chase period (96 h time point). Note the significant decrease in 13C enrichment in the Golgi and mitochondria. In contrast, 13C enrichment in lysosomes is highly variable and does not significantly decrease over the chase period. The thick lines in the violin plots represent the median and the thin lines the upper and lower quartiles. The number of organelles analyzed is indicated at the bottom of the histogram bar. 48 h: N = 11 neurons from 2 rats; 96 h: N = 12 neurons from 3 rats. Statistical analysis: Mann–Whitney two-tailed test; ns = not significant; ****P < 0.0001. Scale bar: 2 µm

Kinetics of glucose-derived carbon in neuronal organelles are differentially affected by α-synuclein overexpression

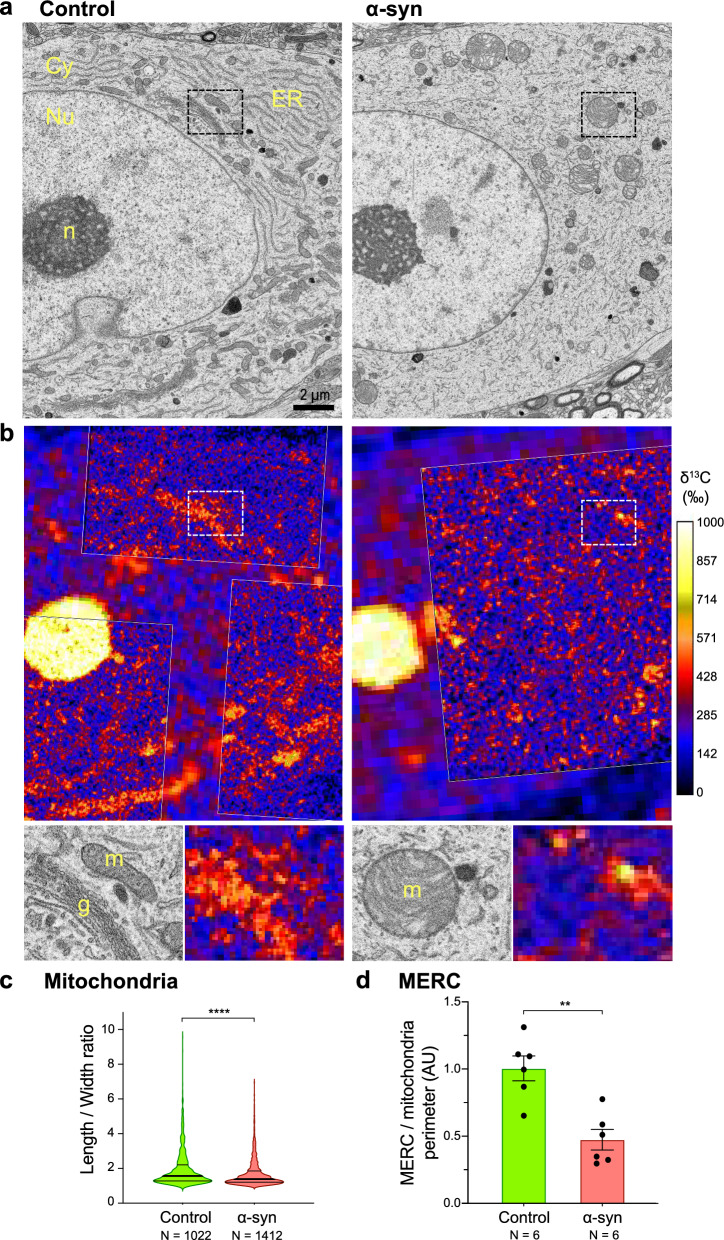

To determine the effects of α-syn overexpression on the incorporation of glucose-derived carbon in individual organelles, we generated SEM images of nigral neuron cell bodies (Fig. 6a) as well as high-resolution 13C enrichment maps (Fig. 6b) in both conditions. These images were aligned as described previously. Overexpression of α-syn in nigral neurons resulted in clear changes in the morphology of major organelles present in the cell body (Fig. 6a). In the contralateral hemisphere injected with the non-coding AAV6 vector, organelle ultrastructure revealed elongated mitochondria as well as ER and Golgi apparatus with typical morphologies. In the pathological condition, however, neuronal cell bodies often displayed a strongly fragmented ER and round-shaped mitochondria with abnormal cristae. To confirm the effects of α-syn overexpression on mitochondrial morphology, the length-over-width ratio was quantified for each individual mitochondria and was found to be significantly reduced (i.e., more spherical shape) in the pathological condition as compared to the control hemisphere (Fig. 6c). In addition, we quantified in individual neurons the relative number of contacts between the ER and mitochondria (MERC), normalized to the overall mitochondrial perimeter length. The frequency of MERC was significantly reduced in the pathological condition (Fig. 6d).

Fig. 6.

Mapping of 13C isotope labeling in three abundant organelles following α-syn overexpression. a Representative SEM images of large neuronal cell bodies comparing the SNpc injected with the control non-coding vector (left panel) and the AAV6-α-syn vector (right panel). Note the changes in organelle morphology caused by α-syn overexpression, with fragmented ER and Golgi apparatus and round-shaped mitochondria with abnormal cristae. Cy: cytoplasm; Nu: nucleus; n: nucleolus; m: mitochondria; g: Golgi apparatus. b Maps of 13C isotope enrichment in the corresponding regions of the neuronal cell bodies. Note the regions analyzed at high resolution to determine 13C levels in specific organelles. The lower panels show high-magnification images corresponding to the regions indicated by dashed rectangles. Note the low 13C enrichment in the mitochondria in the pathologic condition. c Measurement of the length-to-width ratio of mitochondria in the neuronal cell bodies, comparing the control and α-syn-overexpressing hemispheres. The thick lines in the violin plots represent the median and the thin lines the upper and lower quartiles. The numbers of mitochondria analyzed from 2 rats per condition are indicated in the x-axis labels. d Relative number of mitochondria-ER contacts (MERC) normalized to the total length of mitochondria perimeter (N = 6 neurons from 2 rats per condition). Data represent mean ± standard error (SE). Statistical analysis: Mann–Whitney unpaired two-tailed test; ns = not significant; **P < 0.01; ****P < 0.0001

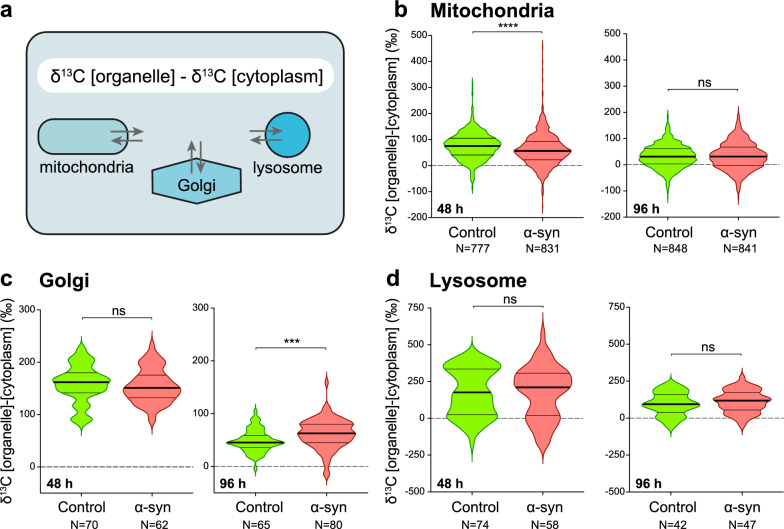

Considering the observed consequences of α-syn on these organelles, we next determined the effects of the α-syn overabundance on 13C incorporation and turnover in each organelle population within the neuronal cell bodies. For each organelle subtype, we determined the difference in 13C enrichment between the organelle and the average 13C enrichment measured in the whole cytoplasm of the corresponding neuron (Fig. 7a–d).

Fig. 7.

Specific defects caused by human α-syn overexpression in the neuronal cell body are revealed by the kinetics of 13C isotope labeling in three abundant organelles. a The schematic illustrates the determination of the difference in 13C enrichment between three organelle subtypes and the average 13C enrichment measured in the cytoplasmic compartment. b–d Measured 13C enrichments in three organelle subtypes: the mitochondria, the Golgi apparatus and the lysosomes. Violin plots are shown to compare the control and α-syn overexpressing conditions at both the 48 h (pulse) and 96 h (chase) time points. Note the significant decrease in 13C incorporation inside mitochondria at 48 h (b) and the significantly higher 13C labeling of the Golgi apparatus at the end of the chase period (c). The thick lines in the violin plots represent the median and the thin lines the upper and lower quartiles. Numbers of organelles analyzed per condition are indicated in the x-axis labels. 48 h: N = 11–12 neurons from 2 rats; 96 h: N = 12 neurons from 3 rats. Statistical analysis: Mann–Whitney unpaired two-tailed test; ns = not significant; ***P < 0.001; ****P < 0.0001

At the end of the pulse period (48 h time point), 13C enrichment relative to the cytoplasm was significantly lower in the mitochondria in neurons located in the α-syn-overexpressing hemisphere (median δ13C: + 56‰ versus + 75‰ in control SNpc; Fig. 7b). This result indicates a specific effect of α-syn accumulation on the incorporation of glucose-derived carbon into mitochondria. In contrast, there were no significant differences in the levels of 13C enrichment measured in the Golgi apparatus and lysosomes between the control and pathological conditions (Fig. 7c, d), indicating that there were no major perturbations of 13C incorporation into these organelles.

A similar comparison was performed at the end of the chase period. In populations of mitochondria and lysosomes, there were no significant differences in the levels of 13C enrichment between the control and pathological conditions (Fig. 7b, d). However, analysis of the Golgi apparatus revealed another effect of α-syn overexpression. At the 96 h time point (i.e., after the chase phase), the 13C enrichment in the Golgi was significantly increased in pathological condition (median δ13C: + 63‰) as compared with the control neurons (median δ13C: + 45‰) (Fig. 7c). This difference indicates that the α-syn accumulation also affects the function of the Golgi apparatus, most likely by slowing down trafficking of macromolecules to other cellular or extracellular compartments.

Discussion

The local expression of human α-syn in the SNpc led to alterations of the neuronal metabolism revealed by a specific pattern of differences in glucose-derived 13C enrichment in subcellular compartments and organelles. These results demonstrate that the combination of NanoSIMS imaging of stable isotope incorporation and turnover, correlated with SEM to identify subcellular structures, is a powerful approach to illuminate how pathological changes affect neuronal and subcellular functions in the brain in early stages of neurodegeneration.

The use of SILK-SIMS to explore metabolic defects during neurodegeneration

The molecular signature of neurodegenerative diseases is characterized by the deposition of misfolded proteins in neurons and glial cells. In PD pathogenesis, the overabundance of the α-syn protein has been shown to cause the formation of misfolded oligomers or fibrils, which interact with a range of cellular processes, although the exact sequence of these events remains unclear. Ultimately, the accumulation of α-syn fibrils into intraneuronal inclusions leads to the trapping of defective organelles, coinciding with major perturbations of cellular organization [32, 48], which can affect metabolic activity in the affected neurons. Here, we used AAV-mediated overexpression of the α-syn protein to induce progressive toxic effects in nigral dopaminergic neurons. In this animal model, α-syn mainly accumulates as disordered monomers [17]. Three to four months after vector injection, misfolded α-syn is detectable using the 5G4 antibody [5], and the formation of proteinase-K resistant α-syn deposits coincides with the presence of insoluble high-molecular weight α-syn species visible in native gel protein electrophoresis [43]. However, extensive aggregation does not occur unless seeding is induced by co-injection of α-syn fibrils [53]. One month after vector injection, we measure α-syn-induced changes in carbon incorporation as an indicator of neuronal dysfunction preceding overt neurodegeneration. A recent study using single-molecule Förster resonance energy transfer showed that A53T α-syn oligomerization occurs on intracellular membrane surfaces, in particular cardiolipin-rich mitochondrial membranes [10]. Although it is unclear where α-syn oligomers form in nigral neurons overexpressing α-syn, this finding is consistent with effects that we observe in the mitochondria and Golgi apparatus.

To understand how the mechanisms leading to neurodegeneration unfold inside neurons, we applied SILK-SIMS to characterize the initial effects of α-syn overexpression on cellular functions in vivo. We assessed anabolic activity inside nigral neurons by measuring the build-up of 13C labeling during a 48-h pulse of 13C-glucose administration, as well as the turnover of glucose-derived carbon in specific compartments during a 48-h chase period. Glucose is an essential fuel for the brain, where it contributes to major bioenergetic and biosynthetic pathways, including the glycolytic pathway, the pentose phosphate pathway, and mitochondrial metabolism [14]. Various glucose metabolites contribute to biosynthetic processes including glycogenesis in glia, lipid metabolism, amino acid synthesis, as well as the production of neurotransmitters, neuromodulators, and nucleic acids. While soluble metabolites are washed away during tissue processing applied in this study, NanoSIMS 13C imaging reveals the level of carbon incorporation into synthesized macromolecules including lipids, proteins and nucleic acids.

Selective vulnerability of nigral dopaminergic neurons linked to high metabolism

Whereas the Lewy pathology characterized by α-syn deposition is not restricted to the SNpc in PD, this brain region contains dopaminergic neurons that are among the most vulnerable to the disease. Several arguments have been put forward to explain the selective vulnerability of nigral dopaminergic neurons, mostly related to intrinsic neuronal properties such as the production and metabolism of the dopamine neurotransmitter, which is linked to the production of reactive oxygen species and mitochondrial activity [23]. Nigral dopaminergic neurons have long, highly branched and unmyelinated axons that contribute to their high bioenergetic demand [6, 39, 44]. In addition, they display slow rhythmic spiking activity with large oscillations of intracellular Ca2+ that stimulate mitochondrial OXPHOS activity [50]. These features contribute in a cell-autonomous manner to metabolic and oxidative stress as well as impaired proteostasis, all together increasing the risk of neurodegeneration in conditions of energy deficiency [36]. Although high metabolic needs are considered as an important factor in the degeneration of specific neuronal populations, this aspect has rarely been addressed. Specific approaches need to be developed to allow for targeted analyses of cell metabolism in brain tissues. In the pulse-chase experiment with 13C-labeled glucose, NanoSIMS imaging of the nigrostriatal system reveals that large-sized neurons located in the SNpc display a strikingly higher level of glucose-derived carbon incorporation and turnover as compared to striatal neurons (Fig. 2). Although other neuronal populations will need to be investigated, nigral neurons appear to have high metabolic demand, as predicted from their morphological and electrophysiological properties.

A method to assess changes in carbon incorporation and turnover following α-syn overexpression

Few techniques are available to assess macromolecule turnover at the cellular level in the mammalian brain. Using hippocampal neurons cultured with 15N-labeled leucine, combined NanoSIMS and fluorescence imaging showed a correlation between neuronal activity and presynaptic protein turnover [29]. NanoSIMS has also been used to assess 15N-leucine incorporation in hippocampal pyramidal neurons following erythropoietin administration in mice, as an indicator of protein synthesis [26]. To address neuropathology, SILK-SIMS analysis has mainly been used to determine the turnover of proteins implicated in neurodegenerative diseases, such as Aβ, tau and SOD1 and to analyze the dynamics of protein aggregation [35, 41]. NanoSIMS has also been used to map elements in the neuromelanin present in dopaminergic neurons of the human SNpc [4]. Here, we used NanoSIMS to assess the effects of locally induced α-syn overabundance on glucose-derived carbon incorporation and turnover in nigral neurons. Unilateral AAV6-α-syn injection induces α-syn overexpression in the SN, while the contralateral hemisphere injected with a non-coding vector is used as internal control for the SILK analysis. NanoSIMS imaging provides sensitive and high-resolution measurements of 13C enrichment and, combined with SEM-based segmentation of specific cell compartments, reveals changes in 13C labeling kinetics at a subcellular level. Although the nature of the 13C-labeled molecules is unknown, the 13C enrichments measured in tissue samples processed for SEM analysis reflect carbon incorporation into a broad suite of macromolecules in each cellular compartment, as a function of anabolic and catabolic fluxes. In order to take into account expected variations in 13C incorporation among animals and among individual neurons, values measured in each cellular sub-compartment were systematically related to the overall 13C level determined in the corresponding cellular compartment (cytoplasm and nucleus versus whole cell; organelles versus whole cytoplasm). When comparing control nigral neurons to those exposed to α-syn overexpression in the same animals, this revealed changes in the kinetics of 13C labeling and points to specific metabolic defects/anomalies, in particular in the mitochondria and Golgi apparatus.

Effects of α-syn overexpression on neuronal 13C-glucose incorporation

Alpha-syn pathology can affect central metabolic pathways, such as lipid metabolism [1], by stimulating glucose uptake but impairing glucose metabolism [2, 46]. In the present study, the neurons located in the AAV6-α-syn injected hemisphere were characterized by a higher carbon turnover in the cell body during the chase period (Fig. 3c), indicating that the overall turnover of macromolecules might be increased in neurons overexpressing α-syn. In the rat SNpc, α-syn overexpression also leads to a redistribution of 13C labeling across the cytoplasmic and nuclear compartments. Whereas in the non-affected SNpc, neurons show higher 13C enrichment in the nucleus than in the cytoplasm during the pulse phase (Fig. 4d), there is no such difference between these two compartments following α-syn overexpression. Although multiple causes may account for this effect, one possible explanation is that α-syn can regulate nuclear activity by interacting with DNA and histones and regulate gene transcription [49]. Furthermore, α-syn has recently been found to affect the integrity of the nuclear envelope as well as the nucleocytoplasmic transport [9], to regulate the activity of processing bodies, and to stabilize mRNAs in the cytoplasm [25].

When analyzing specific organellar compartments, we find that α-syn overexpression leads to abnormally shaped mitochondria, as previously reported [18]. Furthermore, it induces a significant reduction in the level of 13C labelling in mitochondria during the pulse phase (Fig. 7b). This effect indicates alterations of mitochondrial metabolism, possibly related to the reported failure of mitochondria to import macromolecules as a consequence of α-syn interaction with the protein import machinery [13], or via the effects of α-syn at the level of mitochondria-ER contacts (MERC) [24, 40], an inter-organelle connection important for metabolic functions such as lipid metabolism [42]. Finally, at the level of the ER-Golgi axis, α-syn slows down macromolecule turnover in the secretory pathway, an effect revealed by elevated 13C levels in the Golgi apparatus at the end of the chase period (Fig. 7c). Overexpression of α-syn affects the ER-Golgi vesicular trafficking, which correlates with ER stress and Golgi fragmentation, and affects lysosomal glucocerebrosidase activity [12, 22, 33, 54]. In this context, overexpression of Rab1a can partially suppress α-syn toxicity [11, 12]. In addition to the early secretory pathway, α-syn can also disrupt intra- and post-Golgi secretory trafficking, as shown by its interaction with several Rab proteins [8, 11, 20, 56]. Overall, α-syn overexpression is a major perturbator of the secretory pathway [55], which is confirmed by our NanoSIMS imaging of glucose-derived carbon metabolism in the SNpc. Although we did not observe any significant changes in the 13C levels labeling of the lysosomal compartment following α-syn overexpression (Fig. 7d), we cannot exclude an effect of α-syn considering the broad variation in the 13C enrichment observed among individual lysosomes (Fig. 5c, d).

Conclusions

This study illustrates how NanoSIMS can be used to reveal changes in carbon metabolism in specific cellular compartments and organelles following overexpression of α-syn, an abundant protein that has been shown to perturb inter-organelle molecular exchanges. NanoSIMS imaging provides sensitive imaging of stable isotope labeling with high spatial resolution. When correlated with SEM, this powerful approach can be used to reveal changes in the metabolic activity of neuronal subpopulations at the subcellular level and compare normal and disease conditions. Combined with various probes carrying specific isotopic labels (e.g., 13C or 15N) designed for specific biological processes, future nanoscale imaging using SILK-SIMS can help interrogate the dynamics of neuronal metabolism in the normal brain and investigate the metabolic changes underlying neurodegenerative diseases.

Supplementary Information

Additional file 1. Correlating NanoSIMS images with ultra-high resolution EM images in Look@NanoSIMS.

Acknowledgements

The Authors would like to thank Philippe Colin, Aline Aebi, Fabienne Pidoux and Viviane Padrun for their expert technical support.

Abbreviations

- AAV

Adeno-associated virus

- α-syn

Alpha-synuclein

- ER

Endoplasmic reticulum

- EsB

Energy selective backscatter detector

- MERC

Mitochondria–ER contacts

- PD

Parkinson’s disease

- SEM

Scanning electron microscope

- SILK-SIMS

Stable isotope labeling kinetics with secondary ion mass spectrometry

- SNpc

Substantia nigra pars compacta

- TU

Transducing units

Author contributions

GK, AM and BLS conceived the project. BM, GK, AM and BLS designed the experiments. SS, BM, SE and LJ performed the experiments. LP conceived the application for image alignment. All Authors contributed to data analysis. GK, LP, AM and BLS wrote the manuscript.

Funding

This work was supported by a grant from the Synapsis Foundation.

Availability of data and materials

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.

Declarations

Ethics approval and consent to participate

Animal handling and experimentation used in this study were performed according to the Swiss legislation and the European Community Council directive (86/609/EEC) for the care and use of laboratory animals. The protocol was approved by the local ethics committee and by the veterinary authorities.

Consent for publication

Not applicable.

Competing interests

The authors declare no competing interests.

Footnotes

Publisher's Note

Springer Nature remains neutral with regard to jurisdictional claims in published maps and institutional affiliations.

Sofia Spataro and Bohumil Maco contributed equally.

Contributor Information

Anders Meibom, Email: anders.meibom@epfl.ch.

Bernard L. Schneider, Email: bernard.schneider@epfl.ch

References

- 1.Alecu I, Bennett SAL. Dysregulated lipid metabolism and its role in α-synucleinopathy in Parkinson’s disease. Front Neurosci. 2019;13:328. doi: 10.3389/fnins.2019.00328. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Anandhan A, Lei S, Levytskyy R, Pappa A, Panayiotidis MI, Cerny RL, Khalimonchuk O, Powers R, Franco R. Glucose metabolism and AMPK signaling regulate dopaminergic cell death induced by gene (α-synuclein)-environment (paraquat) interactions. Mol Neurobiol. 2017;54:3825–3842. doi: 10.1007/s12035-016-9906-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Auluck PK, Caraveo G, Lindquist S. α-Synuclein: membrane interactions and toxicity in Parkinson’s disease. Annu Rev Cell Dev Biol. 2010;26:211–233. doi: 10.1146/annurev.cellbio.042308.113313. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Biesemeier A, Eibl O, Eswara S, Audinot J-N, Wirtz T, Pezzoli G, Zucca FA, Zecca L, Schraermeyer U. Elemental mapping of neuromelanin organelles of human Substantia Nigra: correlative ultrastructural and chemical analysis by analytical transmission electron microscopy and nano-secondary ion mass spectrometry. J Neurochem. 2016;138:339–353. doi: 10.1111/jnc.13648. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Bobela W, Nazeeruddin S, Knott G, Aebischer P, Schneider BL. Modulating the catalytic activity of AMPK has neuroprotective effects against α-synuclein toxicity. Mol Neurodegener. 2017;12:80. doi: 10.1186/s13024-017-0220-x. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bolam JP, Pissadaki EK. Living on the edge with too many mouths to feed: why dopamine neurons die. Mov Disord. 2012;27:1478–1483. doi: 10.1002/mds.25135. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Bonnin EA, Rizzoli SO (2020) Novel secondary ion mass spectrometry methods for the examination of metabolic effects at the cellular and subcellular levels. Front Behav Neurosci 14 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 8.Breda C, Nugent ML, Estranero JG, Kyriacou CP, Outeiro TF, Steinert JR, Giorgini F. Rab11 modulates α-synuclein-mediated defects in synaptic transmission and behaviour. Hum Mol Genet. 2015;24:1077–1091. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddu521. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Chen V, Moncalvo M, Tringali D, Tagliafierro L, Shriskanda A, Ilich E, Dong W, Kantor B, Chiba-Falek O. The mechanistic role of alpha-synuclein in the nucleus: impaired nuclear function caused by familial Parkinson’s disease SNCA mutations. Hum Mol Genet. 2020;29:3107–3121. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddaa183. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Choi ML, Chappard A, Singh BP, Maclachlan C, Rodrigues M, Fedotova EI, Berezhnov AV, De S, Peddie CJ, Athauda D, Virdi GS, Zhang W, Evans JR, Wernick AI, Zanjani ZS, Angelova PR, Esteras N, Vinokurov AY, Morris K, Jeacock K, Tosatto L, Little D, Gissen P, Clarke DJ, Kunath T, Collinson L, Klenerman D, Abramov AY, Horrocks MH, Gandhi S. Pathological structural conversion of α-synuclein at the mitochondria induces neuronal toxicity. Nat Neurosci. 2022;25:1134–1148. doi: 10.1038/s41593-022-01140-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 11.Cooper AA, Gitler AD, Cashikar A, Haynes CM, Hill KJ, Bhullar B, Liu K, Xu K, Strathearn KE, Liu F, Cao S, Caldwell KA, Caldwell GA, Marsischky G, Kolodner RD, LaBaer J, Rochet J-C, Bonini NM, Lindquist S. α-Synuclein blocks ER-golgi traffic and Rab1 rescues neuron loss in Parkinson’s models. Science. 2006;313:324–328. doi: 10.1126/science.1129462. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 12.Coune PG, Bensadoun JC, Aebischer P, Schneider BL. Rab1A over-expression prevents golgi apparatus fragmentation and partially corrects motor deficits in an alpha-synuclein based rat model of Parkinson’s disease. J Parkinson’s Dis. 2011;1:373–387. doi: 10.3233/JPD-2011-11058. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Di Maio R, Barrett PJ, Hoffman EK, Barrett CW, Zharikov A, Borah A, Hu X, McCoy J, Chu CT, Burton EA, Hastings TG, Greenamyre JT. α-Synuclein binds to TOM20 and inhibits mitochondrial protein import in Parkinson’s disease. Sci Transl Med. 2016;8:342ra78. doi: 10.1126/scitranslmed.aaf3634. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Dienel GA. Brain glucose metabolism: integration of energetics with function. Physiol Rev. 2019;99:949–1045. doi: 10.1152/physrev.00062.2017. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Domesick VB, Stinus L, Paskevich PA. The cytology of dopaminergic and nondopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra and ventral tegmental area of the rat: a light- and electron-microscopic study. Neuroscience. 1983;8:743–765. doi: 10.1016/0306-4522(83)90007-6. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Dusonchet J, Bensadoun J-C, Schneider BL, Aebischer P. Targeted overexpression of the parkin substrate Pael-R in the nigrostriatal system of adult rats to model Parkinson’s disease. Neurobiol Dis. 2009;35:32–41. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2009.03.013. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fauvet B, Mbefo MK, Fares M-B, Desobry C, Michael S, Ardah MT, Tsika E, Coune P, Prudent M, Lion N, Eliezer D, Moore DJ, Schneider B, Aebischer P, El-Agnaf OM, Masliah E, Lashuel HA. α-Synuclein in central nervous system and from erythrocytes, mammalian cells, and escherichia coli exists predominantly as disordered monomer*. J Biol Chem. 2012;287:15345–15364. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M111.318949. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Ganjam GK, Bolte K, Matschke LA, Neitemeier S, Dolga AM, Höllerhage M, Höglinger GU, Adamczyk A, Decher N, Oertel WH, Culmsee C. Mitochondrial damage by α-synuclein causes cell death in human dopaminergic neurons. Cell Death Dis. 2019;10:865. doi: 10.1038/s41419-019-2091-2. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Gaugler MN, Genc O, Bobela W, Mohanna S, Ardah MT, El-Agnaf OM, Cantoni M, Bensadoun J-C, Schneggenburger R, Knott GW, Aebischer P, Schneider BL. Nigrostriatal overabundance of α-synuclein leads to decreased vesicle density and deficits in dopamine release that correlate with reduced motor activity. Acta Neuropathol. 2012;123:653–669. doi: 10.1007/s00401-012-0963-y. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Gitler AD, Bevis BJ, Shorter J, Strathearn KE, Hamamichi S, Su LJ, Caldwell KA, Caldwell GA, Rochet J-C, McCaffery JM, Barlowe C, Lindquist S. The Parkinson’s disease protein α-synuclein disrupts cellular Rab homeostasis. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2008;105:145–150. doi: 10.1073/pnas.0710685105. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Gómez-Suaga P, Bravo-San Pedro JM, González-Polo RA, Fuentes JM, Niso-Santano M. ER–mitochondria signaling in Parkinson’s disease. Cell Death Dis. 2018;9:1–12. doi: 10.1038/s41419-017-0079-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Gosavi N, Lee H-J, Lee JS, Patel S, Lee S-J. Golgi fragmentation occurs in the cells with prefibrillar alpha-synuclein aggregates and precedes the formation of fibrillar inclusion. J Biol Chem. 2002;277:48984–48992. doi: 10.1074/jbc.M208194200. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 23.Graves SM, Xie Z, Stout KA, Zampese E, Burbulla LF, Shih JC, Kondapalli J, Patriarchi T, Tian L, Brichta L, Greengard P, Krainc D, Schumacker PT, Surmeier DJ. Dopamine metabolism by a monoamine oxidase mitochondrial shuttle activates the electron transport chain. Nat Neurosci. 2020;23:15–20. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0556-3. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 24.Guardia-Laguarta C, Area-Gomez E, Rüb C, Liu Y, Magrané J, Becker D, Voos W, Schon EA, Przedborski S. α-Synuclein is localized to mitochondria-associated ER membranes. J Neurosci. 2014;34:249–259. doi: 10.1523/JNEUROSCI.2507-13.2014. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 25.Hallacli E, Kayatekin C, Nazeen S, Wang XH, Sheinkopf Z, Sathyakumar S, Sarkar S, Jiang X, Dong X, Di Maio R, Wang W, Keeney MT, Felsky D, Sandoe J, Vahdatshoar A, Udeshi ND, Mani DR, Carr SA, Lindquist S, De Jager PL, Bartel DP, Myers CL, Greenamyre JT, Feany MB, Sunyaev SR, Chung CY, Khurana V. The Parkinson’s disease protein alpha-synuclein is a modulator of processing bodies and mRNA stability. Cell. 2022;185:2035–2056.e33. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2022.05.008. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.Hassouna I, Ott C, Wüstefeld L, Offen N, Neher RA, Mitkovski M, Winkler D, Sperling S, Fries L, Goebbels S, Vreja IC, Hagemeyer N, Dittrich M, Rossetti MF, Kröhnert K, Hannke K, Boretius S, Zeug A, Höschen C, Dandekar T, Dere E, Neher E, Rizzoli SO, Nave K-A, Sirén A-L, Ehrenreich H. Revisiting adult neurogenesis and the role of erythropoietin for neuronal and oligodendroglial differentiation in the hippocampus. Mol Psychiatry. 2016;21:1752–1767. doi: 10.1038/mp.2015.212. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 27.Hoppe P, Cohen S, Meibom A. NanoSIMS: technical aspects and applications in cosmochemistry and biological geochemistry. Geostand Geoanalytical Res. 2013;37:111–154. doi: 10.1111/j.1751-908X.2013.00239.x. [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 28.Hunn BHM, Cragg SJ, Bolam JP, Spillantini M-G, Wade-Martins R. Impaired intracellular trafficking defines early Parkinson’s disease. Trends Neurosci. 2015;38:178–188. doi: 10.1016/j.tins.2014.12.009. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 29.Jähne S, Mikulasch F, Heuer HGH, Truckenbrodt S, Agüi-Gonzalez P, Grewe K, Vogts A, Rizzoli SO, Priesemann V. Presynaptic activity and protein turnover are correlated at the single-synapse level. Cell Rep. 2021;34:108841. doi: 10.1016/j.celrep.2021.108841. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 30.Li F, Fornasiero EF, Dankovich TM, Kluever V, Rizzoli SO. A Reliable approach for revealing molecular targets in secondary ion mass spectrometry. Int J Mol Sci. 2022;23:4615. doi: 10.3390/ijms23094615. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 31.Lovrić J, Dunevall J, Larsson A, Ren L, Andersson S, Meibom A, Malmberg P, Kurczy ME, Ewing AG. Nano secondary ion mass spectrometry imaging of dopamine distribution across nanometer vesicles. ACS Nano. 2017;11:3446–3455. doi: 10.1021/acsnano.6b07233. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 32.Mahul-Mellier A-L, Burtscher J, Maharjan N, Weerens L, Croisier M, Kuttler F, Leleu M, Knott GW, Lashuel HA. The process of Lewy body formation, rather than simply α-synuclein fibrillization, is one of the major drivers of neurodegeneration. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2020;117:4971–4982. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1913904117. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 33.Mazzulli JR, Xu Y-H, Sun Y, Knight AL, McLean PJ, Caldwell GA, Sidransky E, Grabowski GA, Krainc D. Gaucher disease glucocerebrosidase and α-synuclein form a bidirectional pathogenic loop in synucleinopathies. Cell. 2011;146:37–52. doi: 10.1016/j.cell.2011.06.001. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 34.Mazzulli JR, Zunke F, Isacson O, Studer L, Krainc D. α-Synuclein-induced lysosomal dysfunction occurs through disruptions in protein trafficking in human midbrain synucleinopathy models. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2016;113:1931–1936. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1520335113. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 35.Michno W, Stringer KM, Enzlein T, Passarelli MK, Escrig S, Vitanova K, Wood J, Blennow K, Zetterberg H, Meibom A, Hopf C, Edwards FA, Hanrieder J. Following spatial Aβ aggregation dynamics in evolving Alzheimer’s disease pathology by imaging stable isotope labeling kinetics. Sci Adv. 2021;7:eabg4855. doi: 10.1126/sciadv.abg4855. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 36.Muddapu VR, Chakravarthy VS. Influence of energy deficiency on the subcellular processes of Substantia Nigra Pars Compacta cell for understanding Parkinsonian neurodegeneration. Sci Rep. 2021;11:1754. doi: 10.1038/s41598-021-81185-9. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 37.Nair-Roberts RG, Chatelain-Badie SD, Benson E, White-Cooper H, Bolam JP, Ungless MA. Stereological estimates of dopaminergic, GABAergic and glutamatergic neurons in the ventral tegmental area, substantia nigra and retrorubral field in the rat. Neuroscience. 2008;152:1024–1031. doi: 10.1016/j.neuroscience.2008.01.046. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 38.Nuñez J, Renslow R, Cliff JB, Anderton CR. NanoSIMS for biological applications: current practices and analyses. Biointerphases. 2018;13:03B301. doi: 10.1116/1.4993628. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 39.Pacelli C, Giguère N, Bourque M-J, Lévesque M, Slack RS, Trudeau L-É. Elevated mitochondrial bioenergetics and axonal arborization size are key contributors to the vulnerability of dopamine neurons. Curr Biol. 2015;25:2349–2360. doi: 10.1016/j.cub.2015.07.050. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 40.Paillusson S, Gomez-Suaga P, Stoica R, Little D, Gissen P, Devine MJ, Noble W, Hanger DP, Miller CCJ. α-Synuclein binds to the ER–mitochondria tethering protein VAPB to disrupt Ca2+ homeostasis and mitochondrial ATP production. Acta Neuropathol. 2017;134:129–149. doi: 10.1007/s00401-017-1704-z. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 41.Paterson RW, Gabelle A, Lucey BP, Barthélemy NR, Leckey CA, Hirtz C, Lehmann S, Sato C, Patterson BW, West T, Yarasheski K, Rohrer JD, Wildburger NC, Schott JM, Karch CM, Wray S, Miller TM, Elbert DL, Zetterberg H, Fox NC, Bateman RJ. SILK studies—capturing the turnover of proteins linked to neurodegenerative diseases. Nat Rev Neurol. 2019;15:419–427. doi: 10.1038/s41582-019-0222-0. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 42.Petkovic M, O’Brien CE, Jan YN. Interorganelle communication, aging, and neurodegeneration. Genes Dev. 2021;35:449–469. doi: 10.1101/gad.346759.120. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 43.Pino E, Amamoto R, Zheng L, Cacquevel M, Sarria J-C, Knott GW, Schneider BL. FOXO3 determines the accumulation of α-synuclein and controls the fate of dopaminergic neurons in the substantia nigra. Hum Mol Genet. 2014;23:1435–1452. doi: 10.1093/hmg/ddt530. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 44.Pissadaki E, Bolam JP (2013) The energy cost of action potential propagation in dopamine neurons: clues to susceptibility in Parkinson’s disease. Front Comput Neurosci 7 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 45.Polerecky L, Adam B, Milucka J, Musat N, Vagner T, Kuypers MMM. Look@NanoSIMS—a tool for the analysis of nanoSIMS data in environmental microbiology. Environ Microbiol. 2012;14:1009–1023. doi: 10.1111/j.1462-2920.2011.02681.x. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 46.Powers R, Lei S, Anandhan A, Marshall DD, Worley B, Cerny RL, Dodds ED, Huang Y, Panayiotidis MI, Pappa A, Franco R. Metabolic investigations of the molecular mechanisms associated with Parkinson’s disease. Metabolites. 2017;7:22. doi: 10.3390/metabo7020022. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 47.Serratos IN, Hernández-Pérez E, Campos C, Aschner M, Santamaría A. An update on the critical role of α-synuclein in Parkinson’s disease and other synucleinopathies: from tissue to cellular and molecular levels. Mol Neurobiol. 2022;59:620–642. doi: 10.1007/s12035-021-02596-3. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 48.Shahmoradian SH, Lewis AJ, Genoud C, Hench J, Moors TE, Navarro PP, Castaño-Díez D, Schweighauser G, Graff-Meyer A, Goldie KN, Sütterlin R, Huisman E, Ingrassia A, de Gier Y, Rozemuller AJM, Wang J, Paepe AD, Erny J, Staempfli A, Hoernschemeyer J, Großerüschkamp F, Niedieker D, El-Mashtoly SF, Quadri M, Van IJcken WFJ, Bonifati V, Gerwert K, Bohrmann B, Frank S, Britschgi M, Stahlberg H, Van de Berg WDJ, Lauer ME, Lewy pathology in Parkinson’s disease consists of crowded organelles and lipid membranes. Nat Neurosci. 2019;22:1099–1109. doi: 10.1038/s41593-019-0423-2. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 49.Surguchev AA, Surguchov A. Synucleins and gene expression: ramblers in a crowd or cops regulating traffic? Front Mol Neurosci. 2017;10:224. doi: 10.3389/fnmol.2017.00224. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 50.Surmeier DJ, Obeso JA, Halliday GM. Selective neuronal vulnerability in Parkinson disease. Nat Rev Neurosci. 2017;18:101–113. doi: 10.1038/nrn.2016.178. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 51.Takado Y, Knott G, Humbel BM, Escrig S, Masoodi M, Meibom A, Comment A. Imaging liver and brain glycogen metabolism at the nanometer scale. Nanomed: Nanotechnol Biol Med. 2015;11:239–245. doi: 10.1016/j.nano.2014.09.007. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 52.Takado Y, Knott G, Humbel BM, Masoodi M, Escrig S, Meibom A, Comment A. Imaging the time-integrated cerebral metabolic activity with subcellular resolution through nanometer-scale detection of biosynthetic products deriving from 13C-glucose. J Chem Neuroanat. 2015;69:7–12. doi: 10.1016/j.jchemneu.2015.09.003. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 53.Thakur P, Breger LS, Lundblad M, Wan OW, Mattsson B, Luk KC, Lee VMY, Trojanowski JQ, Björklund A. Modeling Parkinson’s disease pathology by combination of fibril seeds and α-synuclein overexpression in the rat brain. Proc Natl Acad Sci USA. 2017;114:E8284–E8293. doi: 10.1073/pnas.1710442114. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 54.Thayanidhi N, Helm JR, Nycz DC, Bentley M, Liang Y, Hay JC. α-Synuclein delays endoplasmic reticulum (ER)-to-golgi transport in mammalian cells by antagonizing ER/Golgi SNAREs. Mol Biol Cell. 2010;21:1850–1863. doi: 10.1091/mbc.E09-09-0801. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 55.Wang T, Hay JC (2015) Alpha-synuclein toxicity in the early secretory pathway: how it drives neurodegeneration in Parkinsons disease. Front Neurosci 9 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 56.Yin G, Lopes da Fonseca T, Eisbach SE, Anduaga AM, Breda C, Orcellet ML, Szegő ÉM, Guerreiro P, Lázaro DF, Braus GH, Fernandez CO, Griesinger C, Becker S, Goody RS, Itzen A, Giorgini F, Outeiro TF, Zweckstetter M. α-Synuclein interacts with the switch region of Rab8a in a Ser129 phosphorylation-dependent manner. Neurobiol Dis. 2014;70:149–161. doi: 10.1016/j.nbd.2014.06.018. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Additional file 1. Correlating NanoSIMS images with ultra-high resolution EM images in Look@NanoSIMS.

Data Availability Statement

The datasets used and/or analyzed during the current study are available from the corresponding authors on reasonable request.