Abstract

Background and Objectives

Given the increase in methodological pluralism in research on brain health, cognitive aging, and neurodegenerative diseases, this scoping review aims to provide a descriptive overview and qualitative content analysis of studies stating the use of participatory research approaches within Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) literature globally.

Research Design and Methods

We conducted a systematic search across four multidisciplinary databases (CINAHL, SCOPUS, PsycInfo, PubMed) for peer-reviewed, English-language studies addressing ADRD that explicitly described their use of a participatory research approach. We employed a systematic process for selecting articles that yielded a final sample of 163 studies. Data from articles were analyzed to chart trends from 1990 to 2022 in terminology, descriptions, application of participatory approaches, and the extent and nature of partnerships with nonacademics.

Results

Results demonstrated geographic differences in the use of stated approaches between North America—where community-based participatory research predominates—and Europe, where Action Research is most common. We further found that only 73% of papers in this systematic review had identifiable definitions or descriptions of the participatory approach used. Findings also showed that 14% of articles demonstrated no evidence of engaged partnership beyond activities typical of research participants, while 23% of articles identified partnering with people with dementia, and an additional 16% reported partnerships with members from Indigenous, Black, Asian, or Latinx communities.

Discussion and Implications

This scoping review identifies three areas in need of greater attention in ADRD literature using participatory research approaches. First, findings indicate the importance of strengthening the use, transparency, and rigor of participatory methods. Second, results suggest the need for greater inclusion of historically marginalized groups who are most affected by ADRD as research partners. Finally, the findings highlight the need for integrating social justice values of participatory approaches into research project designs.

Keywords: Aging, Dementia, Lived experience, Participatory research, Scoping review

Translational Significance: Participatory research approaches constitute an innovative area of methods for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) research that has been found to increase participation among Black, Indigenous, People of Color (BIPOC) communities and increase the use of interventions in communities and health institutions. However, no study to date has synthesized how participatory approaches are being characterized and applied in ADRD research. We conducted a scoping review to provide an overview of the range of applications of participatory research approaches in ADRD across countries, disciplinary settings, topical areas, and the extent of inclusion of people with dementia and BIPOC communities. These findings highlight the range of approaches and applications and the need for improved professional norms to increase rigor.

The field of Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) has grown tremendously in the past decade, with multiple global initiatives supporting research on brain health, cognitive aging, and neurodegenerative diseases (Aranda et al., 2021; National Institute on Aging, n.d.). Methodological pluralism has accompanied this growth. Researchers from a vast array of disciplines, both within and outside the biomedical sciences, have oriented to studying ADRD (Brody & Galvin, 2013; Super & Ty, 2022).

This scoping review aims to describe one emerging approach in the field of ADRD: participatory research. Participatory research has been defined as a “science and discipline of knowledge creation and use” (Andersson, 2018). The central objective of participatory research is to produce a more democratic process of knowledge creation, transform the social reality of the people involved, and furthermore, contribute to the social transformation of society (Pain & Francis, 2003; Selener, 1997). Its defining characteristic is the degree and quality of engagement of participants in research-related activities (Pain & Francis, 2003). It centers on the relationship dynamics that underlie the research process, paying particular attention to whom the knowledge generated will benefit, whose expertise is valued, and how it will be used beyond academia (Andersson, 2018; Gaventa & Cornwall, 2006; Wallerstein et al., 2017). Researchers have called for greater use of participatory methods in the field of ADRD to improve recruitment and retention (Grill & Galvin, 2014), greater attention to issues of health equity (Gilmore-Bykovskyi et al., 2019), improved study design and application of findings (Hendriks et al., 2018), and to center the voices of people living with dementia (Reuben, 2020).

Our study provides an overview of the stated use of participatory approaches within peer-reviewed research papers on ADRD published through 2022. We deliberately include studies across the world that use a variety of terms to describe their participatory approaches, engage a range of potential partners, and have been conducted in various settings. Guided by the origins of participatory approaches in theoretical stances on the importance of transformational social change and redressing systems of oppression in and of which scientific research methods have developed (Freire, 1968), we also focus on the extent to which researchers are partnering with people living with dementia and individuals from historically oppressed racial/ethnic groups.

Overview of Participatory Methods

Long-standing approaches to human subjects research clearly distinguish roles among actors in research processes: the traditional role expectation for researchers is to advance knowledge by collecting, analyzing, and interpreting data from subjects, and the role of the research participant is to respond to the researchers’ requests for information or specimens. This process of generating knowledge has often led to the objectification of research participants and has been critiqued for its potential to perpetuate oppression among marginalized populations (Fals-Borda & Rahman, 1991; Gaventa & Cornwall, 2006; Reyes et al., 2022; Torres et al., 2020). In this sense, knowledge production is a sociopolitical activity that functions to determine the limits and possibilities of our society. Fals-Borda and Rahman (1991) describe it as a system of power and control that functions alongside processes of material production to create and sustain socioeconomic inequities: “Domination of masses by elites is rooted not only in the polarization of control over means of material production, but also over the means of knowledge production, including control over the social power to determine what is useful knowledge” (Fals-Borda & Rahman, 1991, p. 14). From these observations that position knowledge as a tool of sociopolitical power, scholars such as Kurt Lewin (1946) and Pablo Freire (1968) theorized participatory research as an alternative pathway that could promote empowerment and social equity (Freire, 1968; Lewin, 1946). Freire in particular highlighted the potential of participatory research as a tool that could serve oppressed groups to disrupt power dynamics embedded in the monopoly of knowledge production.

This literature positions participatory research to be particularly valuable for challenging deep-rooted power inequities in the process of knowledge production, and application, and as a tool that can improve the lives of participants. In participatory research approaches, the integration of participants’ expertise and participation in the research process is a central contribution to challenging knowledge inequity and the inequities that follow through its use and applications (Huffman, 2017). It also has been stipulated that actions taken from the knowledge produced must be “collective efforts to effect community-level changes that go beyond efforts to modify individual-level behaviors of community members” (Cook, 2008, p. 669). Without creating processes of decision-making and acknowledging power differentials, researchers cannot create the conditions for authentic participation (Gaventa & Cornwall, 2006; Macaulay, 2017).

Literature Review

Much of the emphasis on participatory approaches in the field of ADRD has focused specifically on the participation of people with dementia. This focus has been prompted, in part, by the efforts of several organizations throughout the world. For example, the Alzheimer’s Society in the United Kingdom has a public statement on its website discussing the importance of including people with dementia and their care partners in research processes (Alzheimer’s Society, n.d.). With similar aims, in the United States, the 2017 National Research Summit on Care, Services, and Supports for Persons with Dementia and Their Caregivers included a stakeholder group comprised of people living with dementia that enabled those individuals and their care partners to share their perspective on future research agendas and strategies to encourage active participation of people with dementia in research (Frank et al., 2020).

Several prior empirical reviews have focused on the use of participatory research methods in the field of ADRD, many of which include people with dementia and their care partners as engaged contributors in the research process. For example, Bethell and colleagues sought to describe the extent and nature of patient engagement approaches that have been used to involve individuals with dementia and their care partners in research (Bethell et al., 2018). The authors identified several barriers to the engagement of individuals with dementia, such as difficulty maintaining ongoing commitment from people with dementia and dementia-related stigma leading to assumptions about lack of capacity to participate in research. On the other hand, the researchers found that the involvement of organizations and philanthropies that serve people with dementia and their care partners created opportunities for engagement of people with dementia in research. Importantly, the authors acknowledged that some studies that actively involved people with dementia in the research process did not adequately describe the ways in which people with dementia and care partners were engaged.

Most recently, Kowe and colleagues conducted a systematic review to explore the impact of participatory research with people with dementia on researchers, as well as provide guidance on how the participatory research process could be improved (Kowe et al., 2022). Based on nine studies from the United Kingdom, Belgium, and the United States, the authors found that researchers benefitted from actively partnering with individuals with dementia by developing an increased understanding of, and greater competence for, collaborating with people with dementia. Challenges identified included difficulty establishing a balanced relationship among researchers and people with dementia and putting forth the additional effort and time to conduct the research beyond traditional research study processes. To improve the participatory research process, the authors called for training and structured guidelines on how to conduct engaged research with people with dementia.

Our study expands upon empirical knowledge of participatory approaches in ADRD literature in several ways. First, our review centers on the concept of participatory research methods, as described earlier. Second, our review includes studies encompassing diverse partnerships to include care partners, family members, health-care professionals, and others in addition to people with dementia. In addition, it draws attention to the inclusion of historically marginalized groups (i.e., people with dementia and individuals from historically marginalized racial/ethnic groups), which is theoretically a primary motivation of participatory approaches as described by Freire (1968) and Lewin (1946). Furthermore, our review incorporates studies representing a global scope given international interest in increasing community-engaged research in the field of ADRD.

Method

We conducted a scoping review of ADRD studies that characterized their research approach as participatory. A scoping review was selected given its utility for examining the extent of empirical literature on a given topic, the range and characteristics of evidence on the topic, current trends, and gaps in the literature to improve future research (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005). Guided by Arksey and O’Malley’s scoping review framework (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005) and Peters et al.’s (2020) updated guidance for conducting a scoping review, our research aims were to provide a descriptive overview of (a) the range of geographic and disciplinary settings, as well as topical areas, in which participatory research approaches in ADRD empirical literature had advanced, (b) the terms and definitions of participatory approaches used, and (c) the extent of inclusion of people with dementia and other groups as participatory partners, as well as individuals from historically marginalized racial/ethnic groups. This study follows the reporting guidelines of the PRISMA-ScR Checklist (Tricco et al., 2018).

Inclusion Criteria

Consistent with our research aim to review studies in the field of ADRD that report the use of participatory methods, our inclusion criteria were as follows:

Empirical study, or study that describes the methods employed for an empirical study;

Substantive focus on cognitive aging or ADRD in later life;

Explicitly state the use of at least one of the following: participatory research, action research, participatory action research (PAR), community-based participatory research (CBPR), co-research, or some variation thereof;

Published in a peer-reviewed publication; and

Available in English

Our search did not apply any specific limits regarding geographic region, time of publication, or severity/type of dementia. Given the variety of participatory approaches and definitions, we focused on selecting studies primarily through the terminology used. Therefore, studies that engaged participants beyond traditional research subjects but did not explicitly state the use of a participatory approach term in any part of the article (i.e., title, abstract, and main body of the text) were not included in this study. In addition, systematic/scoping reviews and conceptual articles were not included.

Data Sources and Search Strategies

A manual preliminary search on Google Scholar of relevant literature was conducted to gain a sense of terms and keywords being used throughout different disciplines, geographic regions, and time. The preliminary search yielded 19 articles; this list was provided to a university librarian, who worked with us to develop and select search terms and databases. Using the records for this initial list, the librarian browsed titles, abstracts, keywords, MESH, identifiers, thesaurus, subject headings, and key concepts and subsequently designed a three-category search term strategy, using “and” across the categories of cognition, participatory research, and aging (see Table 1).

Table 1.

Search Terms

| Criteria # | Concept | Search text string |

|---|---|---|

| 1 | Cognition | Alzheimer’s disease or Alzheimer’s or Alzheimer*or cognition disorder* or memory disorder* or dementia |

| 2 | Participatory research | Participatory action research OR participatory research OR action research or appreciative inquiry or community-based participatory research or community engagement or community involvement or user research |

| 3 | Aging | Older adults OR aged OR older people OR aging |

Given the multidisciplinary nature of the research topic (e.g., across ADRD specifically, health in general, and the social sciences), we used four databases for a systematic search of articles: CINAHL, SCOPUS, PsychInfo, and PubMed.

Study Selection

Search results were downloaded into Zotero, a reference management software. The lead author screened titles and abstracts identified by the search, removed duplicates, and applied the selection criteria. Following this initial review of studies for inclusion criteria, full-text copies of sources were obtained for all studies. For articles that the full-text could not be obtained through institutional holdings, authors were directly contacted to procure the article. Studies were downloaded to a spreadsheet created to facilitate our screening for inclusion/exclusion criteria. This tracker included the following categories: citation, year of publication, keywords, meets criteria (reasons why the article meets criteria), and does not meet criteria (reasons why the article does not meet criteria). As recommended by Levac and colleagues to ensure the reliability of article inclusion and exclusion, the authors independently reviewed papers, classified them according to criteria, and discussed discrepancies to arrive at a final sample (Levac et al., 2010). The first and third authors reviewed the first 30 papers separately to ensure consistency in inclusion/exclusion criteria.

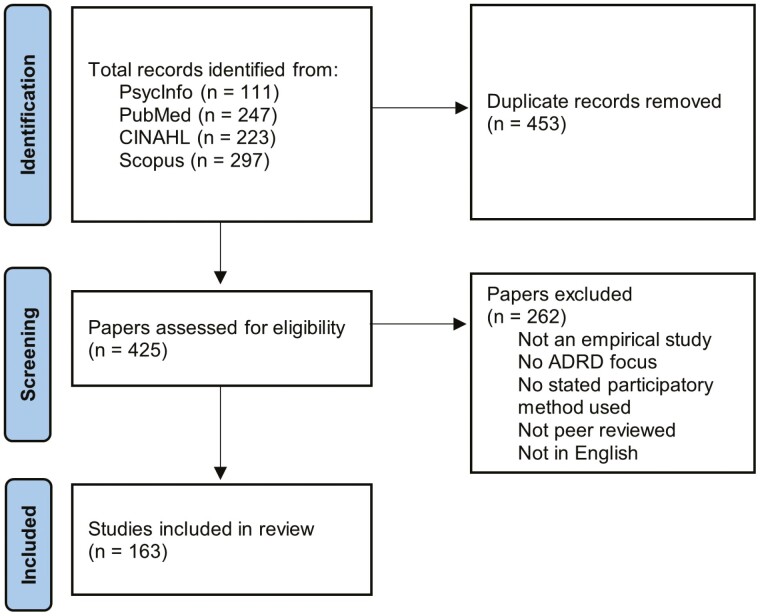

Figure 1 shows the Preferred Reporting Items for Systematic Reviews and Meta-Analyses (PRISMA) Flow Diagram, which outlines the study selection process (Moher et al., 2009). Our initial systematic search began at the end of 2019 but was halted due to the COVID-19 pandemic. The study then restarted in late 2021, and we conducted a new systematic search across the same four databases using the same keywords that yielded a total number of 374 studies. Of these 374 studies, 228 did not meet inclusion criteria, which brought our sample to 146. This sample was divided up into three lists that underwent a full-text review by all three authors independently, and meetings were held to discuss a selection of studies and inclusion criteria. The data extraction and analysis were carried out with this final sample of studies. In January 2023, we decided to do a refresh to include new articles published throughout 2022. This search yielded an additional 51 nonduplicated studies, of which 34 were excluded after undergoing the same process for preliminary and full review. In total, we assessed 425 for eligibility and excluded 262 articles, yielding a final sample of 163 publications.

Figure 1.

PRISMA flow diagram of study selection process. ADRD = Alzheimer's disease and related dementias.

Data Charting Process

We developed a data charting spreadsheet to extract key information from each of the included articles, consistent with the methodological standards for scoping reviews (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005; Peters et al., 2020). To ensure consistency of approach to data extraction (Levac et al., 2010), the study team (authors and a graduate assistant) independently reviewed all papers. Supplementary Table 1 describes the data fields that we extracted in our review for each article, including geographic region, participatory research method, study setting, evidence of active partnership with nonacademic research partners (i.e., non-professionally trained researchers from outside of academia), partner type, research method, community partners from diverse ethnoracial groups, journal type, and research topics. Supplementary Table 2 lists each of the articles organized by type of participatory approach used, their first-listed author’s last name, year of publication, geographic setting (by country), a brief summary of the research aim, and research setting.

Synthesis of Results

Analysis was conducted in compliance with the fourth and fifth stages of the scoping review framework (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005) where key information from selected articles was charted, collated, and summarized. Findings from the studies were compared and contrasted according to the objectives of the review (Peters et al., 2020), which involved a description of the characteristics of the studies, terminologies and definitions, and nonacademic partners. Specifically, we used thematic analysis—where the researchers “identified, analyzed and reported patterns within the data” (Vaismoradi et al., 2013)—to derive insights about terminologies and definitions as well as nonacademic partners. We also identified the limitations of this group of studies and their implications for future research in this area of study.

Findings

We present results in three sections: (1) a descriptive summary of the characteristics of ADRD research stating the use of a participatory research approach, (2) results from an analysis exploring trends in the use of approach terminologies and definitions, (3) a description of the range of nonacademic partners engaged across countries and types of participatory approaches, with particular attention to the inclusion of people with dementia and individuals from Indigenous, Black, Latinx, and Asian communities.

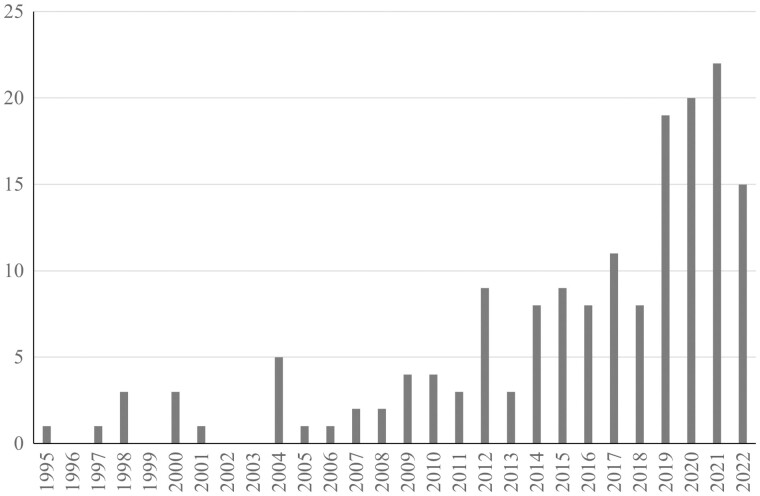

Characteristics of ADRD Research Papers Stating the Use of Participatory Approaches

The number of research articles published by year (1995 to January, 2023) included in the current sample is shown in Figure 2. The results suggest a growing interest in the use of participatory methods within the field of ADRD, as evidenced by the increase in articles published at the turn of the 21st century. CBPR, participatory methods, and co-research are relatively newer approaches (published more frequently in the 2010s and beyond), while action research and PAR have been used since the late 1990s. For example, the earliest paper (Rolfe & Phillips, 1995) used the term “action research,” and it was not until more than a decade later that the term “CBPR” emerged (MacDonald et al., 2006).

Figure 2.

Number of research articles published by year (N = 163).

Table 2 shows a descriptive overview of study characteristics for the 163 articles included in our review. Most studies were conducted in the UK (31%), followed by 25% in North America (United States and Canada), and 17% in Oceania (Australia and New Zealand). An additional 17% were conducted across Europe, 7% in Asia, and 4% in other regions. The study settings varied considerably, with 33% in nonhealth-care settings, 33% in institutional settings, and 31% in community-based health care settings. A total of 23% of articles provided evidence of partnerships with people with dementia, 1% partnered with rural communities, and 16% partnered with Indigenous, Black, Latinx, or Asian communities. In addition, the majority of studies used qualitative methods (66%), 13% were quantitative, 12% used mixed methods, and 9% were process articles (i.e., they described a larger program of empirical research). In addition, the studies were published in a wide range of journals, with 36% in health professions journals, 18% in ADRD-focused journals, and 16% in aging journals.

Table 2.

Characteristics of Studies in the Final Sample (N = 163)

| Study Characteristics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Region | ||

| UK | 50 | 31 |

| North America | 40 | 25 |

| Oceania | 28 | 17 |

| Europe | 28 | 17 |

| Asia | 11 | 7 |

| Other (including multiregion) | 6 | 4 |

| Participatory research method | ||

| Action research | 54 | 33 |

| Participatory action research (PAR) | 47 | 29 |

| Community-based participatory research (CBPR) | 33 | 20 |

| Participatory research | 15 | 9 |

| Co-research | 8 | 5 |

| Other | 6 | 4 |

| Study setting | ||

| Nonhealth-care setting | 54 | 33 |

| Institution | 54 | 33 |

| Community-based health care | 51 | 31 |

| Mixed | 4 | 2 |

| Partnered with people with dementia | 38 | 23 |

| Partnered with rural communities | 2 | 1 |

| Partnered with Indigenous, Black, Latinx, or Asian communities | 26 | 16 |

| Research method | ||

| Qualitative | 108 | 66 |

| Quantitative | 22 | 13 |

| Mixed methods | 19 | 12 |

| Process article | 14 | 9 |

| Journal type | ||

| Health professions | 59 | 36 |

| Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias (ADRD) | 30 | 18 |

| Aging | 26 | 16 |

| Social sciences and health | 17 | 10 |

| Research methods | 16 | 10 |

| Other | 9 | 6 |

| Policy | 2 | 1 |

| Disability | 2 | 1 |

| Technology | 2 | 1 |

Table 3 shows the primary research topics explored in the included studies (see Supplementary Table 3 for specific articles corresponding to each topic). The majority of studies (61%) focused on enhancing the quality of dementia care delivered by health-care professionals, family members, or volunteers. In addition, 14% focused on understanding the lived experience of people with dementia, their care partners, and health-care professionals. An additional 13% aimed to demonstrate the feasibility of partnering with people with dementia and other stakeholders in engaged research. The remaining articles aimed to improve outreach to, and research participation, among people with dementia, their care partners, and individuals from historically oppressed groups (5%), understand environmental and place-based contexts for people with dementia (e.g., outdoor and public spaces; 4%), and increase awareness of dementia and dementia services for the community at large (4%).

Table 3.

Overarching Research Topics

| Topics | N | % |

|---|---|---|

| Enhance quality of dementia care delivered by health-care professionals, family members or volunteers | 99 | 61 |

| Understand the lived experience of people with dementia, their care partners, and health-care professionals | 23 | 14 |

| Demonstrate the feasibility of partnering with people with dementia and other stakeholders in engaged research | 21 | 13 |

| Improve outreach to, and research participation among, people with dementia, their care partners, and individuals from historically oppressed groups | 8 | 5 |

| Understand environmental and place-based contexts for people with dementia | 6 | 4 |

| Increase awareness of dementia and dementia services | 6 | 4 |

Trends in Terms and Definitions of Participatory Approaches within ADRD Research

Participatory research in ADRD literature has used distinct but related terminology to describe research involving partnerships between researchers and nonacademic partners. As shown in Table 2, action research was the term most used (33%; 54 papers), followed by PAR (29%; 47 papers), CBPR (20%; 33 papers), participatory research (9%; 15 papers), and co-research or another related term (e.g., co-production; 9%; 14 papers). Our findings revealed that the choice of terminology was often closely related to geographic region. For example, the majority of papers that used CBPR and related terms (e.g., CBPAR, CPAR) were from North America (39% from the United States and 36% from Canada). In fact, all papers (100%) published in the United States used CBPR, while publications from other countries varied in the use of participatory terminologies. For example, publications from England made up 63% of publications using co-research, 53% of publications using participatory research, and 35% of publications using action research. On the other hand, 26% of Australian and 17% of Canadian publications used PAR. Studies conducted in countries across Asia (11 papers) primarily used CBPR (36%) and PAR terminology (36%).

In addition, we reviewed groupings of articles according to each participatory approach category and related terminology (denoted by “+”) and synthesized definitions for each terminology as presented in the literature. Only 73% of papers in this systematic review had identifiable definitions or conceptual descriptions of the participatory approach that the articles stated. Following is a summary of the literature by type of participatory approach used.

Action Research (+)

A total of 45 studies stated using action research, and an additional nine papers used a variation of this term (e.g., emancipatory action research and organizational action research). Of these 54 articles, 69% provided a description or definition of the term. Most definitions state or describe the “action research cycle” (Ayton et al., 2020; Davies et al., 2014; Mitchell et al., 2020). This multiphase research cycle begins with problem definition, developing a practice-based solution, generating insights from that change, and re-engaging in the cycle until an improvement is made. Definitions also showed that this is practitioner-centered research with a strong emphasis on their leadership in implementation and practice/systems change within their workplace.

Participatory Action Research (+)

A total of 43 studies were identified using PAR, and an additional four papers used a variation of this approach (e.g., applied PAR and PAR storytelling). Of these 47 articles, 81% provided a description or definition of the term. Notably, while the term used in the title or abstract of these papers was PAR, many of the definitions drew from action research or explicitly used the terminology and described the action research cycle (Andrews et al., 2019; Chenoweth & Kilstoff, 1998; Harkin et al., 2022). The main difference that emerged between studies using action research versus PAR was that the latter focused more on community partnerships beyond practitioners, and more readily identified the involvement of people from marginalized backgrounds (Dupuis et al., 2021; Goeman et al., 2016). Studies stating the use of PAR also included more discussions on different ways of knowing, such as those emerging from lived experience. Definitions often highlighted mutual learning leading to work that supported the transformation of people’s lives and social change.

Community-Based Participatory Research (+)

A total of 27 studies stated the use of CBPR, and an additional six papers used a variation of this approach (e.g., CPAR and de-colonized CBPAR). Of these 33 articles, 75% provided a description or definition of the term. These definitions centered on relationship building and integrating scientific, lived experience, and indigenous knowledge to produce new insights (Cornect-Benoit et al., 2020; MacDonald et al., 2006). The main values of CBPR identified throughout the literature were attention to equity, collaborative partnerships, bridging knowledge and change, acknowledging expertise beyond academia, attention to culture, and valuing partners’ leadership (Askari et al., 2018; Lee et al., 2018; Parker et al., 2022). In addition, community members were sometimes identified as the initiators of the research study, rather than academic researchers. A few studies highlighted the benefit of CBPR for the recruitment and retention of hard-to-reach populations (Austrom et al., 2010; Etkin et al., 2012; Park et al., 2022), and for promoting community-led research (Austrom et al., 2010; Phillipson & Hammond, 2018).

Other Approaches

Less common terminologies in the literature were participatory research (15 articles) and co-research or related terms (14 articles). The studies stating the use of participatory research (and variations) placed emphasis on respect and acknowledgment of participant’s and their expertise. Most articles (80%) using participatory research provided a definition. These definitions discussed the value of engaging participants’ expertise in the research process, as well as acknowledging power dynamics between researchers and participants. In addition, unlike action research, PAR, and CBPR, studies stating the use of participatory research mostly engaged individuals, rather than teams or community groups. Furthermore, only 37% of the eight studies specifically using the term co-research provided a definition. Definition focused involvement of participants in the research process and describing co-researchers as joint contributors (Sprange et al., 2021) and lay co-researchers (Mockford et al., 2016). This language locating participants as nonprofessional rather than experts was not found among the other participatory approaches.

Trends in Partnerships in ADRD Research

Studies’ descriptions of the partners’ participation varied widely. Participation ranged from traditional participant subject to being part of a steering committee or feedback group, engaging in problem identification, instrument and intervention development, recruitment, data collection, data analysis, dissemination of research findings, and co-authoring. Of the total 163 articles stating the use of a participatory approach, 14% (23 articles) demonstrated no evidence of engaged partnership beyond activities typical of research participants (e.g., providing data, member checking, etc.). Of these studies that demonstrated no evidence of engaged partnership, 61% specified using an action research + approach, and the largest concentration was in the UK and Europe.

Of the remaining 140 articles that demonstrated evidence of engaged partnerships, 38 articles identified partnering with people with dementia. Among the 38 studies, 42% identified solely partnering with individuals living with dementia, and the rest included practitioners and caregivers as partners in addition to people with dementia. One study described partnering with people with dementia living in a rural community (Hicks et al., 2020), and no study specified partnering with people with dementia from Indigenous, Black, Asian, or Latinx populations. Globally, only 26 studies discussed partnerships with individuals (e.g., residents, caregivers, health-care professionals) from, or organizations serving Indigenous, Black, Asian, or Latinx communities. Some studies reported partnering with Asian practitioners and community members (Lhimsoonthon et al., 2019; Li & Ho, 2019; Lindgren et al., 2012; Park et al., 2022) as well as Indigenous community members (Acharibasam et al., 2022; Cornect-Benoit et al., 2020; Cox et al., 2019; Dieter et al., 2018; Jacklin et al., 2020; Pace, 2020; Walker et al., 2021; Webkamigad et al., 2020). In addition, a few studies specified partnering with multiethnic practitioners, caregivers, and community residents (Goeman et al., 2016; Kilstoff & Chenoweth, 1998; Nielsen et al., 2022).

Among studies that demonstrated evidence of partnering with individuals with dementia and/or community organizations, residents, caregivers, and/or practitioners from ethno-racially diverse groups (n = 66), the majority were located in Canada (27%), England (21%), and Australia (18%). Almost all studies that reported partnering with Indigenous communities were conducted in Canada, with the exception of one in Australia (Cox et al., 2019). In the United States, no study specified partnering with individuals with dementia, one study reported partnering with Black American community members (Bardach et al., 2021), and another described partnerships with Latinx and Middle Eastern/Arab Americans (Ajrouch et al., 2020). Some studies reported partnerships with organizations representing historically marginalized groups (Askari et al., 2018; Hong et al., 2019; Morhardt et al., 2010; Park et al., 2022). Although a variety of participatory approaches were described across this subset of 66 studies, the most common participatory approaches were CBPR (30%) and PAR (24%).

Discussion

This scoping review provides a descriptive overview of English-language, peer-reviewed publications on ADRD that state the use of participatory research approaches. We explicitly designed our review to focus on studies conducted across a range of geographies, settings, and disciplines, with a variety of partners and on a diversity of research topics. Despite the expansiveness of our review, we were intentional in our focus on studies that expressly reported the use of participatory approaches, such as through their use of specific terms including action research, CBPR, and the like (refer to search terms in “Method”). Unlike engaged research in general, which broadly calls for participants’ involvement in research projects beyond the typical role of “subject” (Bethell et al., 2018), participatory methods are epistemologically grounded in principles of democratizing knowledge production and attending to issues of power in interpersonal interactions and broader systems change (Freire, 1968; Lindhult, 2022).

Our foundational review provides a beginning portrait of participatory approaches within the field of ADRD. For example, participatory methods were used in the context of biomedical, social, scientific, demographic, and other research traditions. We also found geographic tendencies and historical trends, such as the more predominant use of CBPR in Canada and the United States. In addition, while the majority of studies using participatory approaches in ADRD research used qualitative methods, there were some studies that used quantitative and mixed methods, as well as process-oriented articles that provided an in-depth description of conducting a study using a particular participatory approach. Our analysis of terms and definitions revealed that terminologies are variable, with different emphases on particular components of relational processes and research activities across studies employing both similar and different approaches. Finally, our analysis of partnerships also showed a scarcity of research on people with dementia and Black, Indigenous, Asian, and Latinx people and communities in this field. Primarily, the lack of attention to intersectionality among people with dementia population is a critical gap in ADRD studies using participatory research approaches. In light of these important findings, our foundational review demonstrates the value of undertaking a full systematic review as a next step to advance understanding of this area of research (Arksey & O’Malley, 2005).

Therefore, we interpret our findings to identify essential areas for continuing to develop the use of participatory approaches within the field of ADRD. Subsequently, we discuss ways in which this review highlights the need for greater attention to “how,” “who,” and “why” of participation among partners of academic researchers.

Attending to “How” Participatory Practices are Facilitated and Enacted

Our paper provides an essential foundation for future exploration of how researchers enact core values of participatory research in their practices (e.g., acknowledgment of power dynamics, decision-making processes, and equitable participation; Minkler, 2012). For example, some studies have used a consensus model of governance where every participant receives an equal vote toward decision-making (Tan et al., 2014). Another strategy toward shared power is the use of a decentralized decision-making model, where subcommittees are established with representation from the different stakeholder groups, and each is responsible for a specific aspect of the research project and can shape decisions in that area (Israel et al., 2010). However, as stated previously, many studies only used a participatory term without providing a definition or a description of their approach. This hindered our ability to draw systematic conclusions on the extent to which researchers were attending to key features of participatory research. Similar to conclusions from prior reviews (Bethell et al., 2018; Kowe et al., 2022; Suijkerbuijk et al., 2019), our review indicates the need for greater transparency in how studies implement participatory designs, such as through journal guidelines, study-specific process-focused papers, and Supplemental Materials describing their participatory process to improve the credibility of these approaches and increase replicability of methods in this field. Without evidence-based guidelines on the “how” of participatory research methods, the stated use of participatory approaches can easily subvert their very intention to attend to power issues and contribute to social change (Chambers, 1994).

Attending to “Who” is Participating

Much of the discourse on participatory approaches has called for the inclusion of people with dementia (Tanner, 2012) and people from historically oppressed ethno-racial groups, who are the populations primarily affected by ADRD (Moon et al., 2019). Here in the United States, where all three authors of this paper are located, Black older adults are twice as likely to experience ADRD than non-Hispanic White older adults, and Latinx older adults are 1.5 times more likely to have ADRD compared with non-Hispanic White older adults (Alzheimer’s Association, 2023). Yet, in our sample, only one study conducted in the United States included Black older adults, and another included Latinx and Middle Eastern adults of all ages for recruitment into future ADRD research (Ajrouch et al., 2020; Bardach et al., 2021). Furthermore, from the global sample, not a single study reported including people with dementia who were also Black, Indigenous, Asian, or Latinx. This is a critical gap in the current literature that future research should attend to, especially with regard to attending to how experiences of racism and discrimination negatively affect brain health across the life course (Glymour & Manly, 2008; Pohl et al., 2021). ADRD research has a responsibility to integrate the voices of individuals and communities from historically marginalized racial/ethnic groups to improve the state of empirical knowledge on the subject.

Attending to the “Why” of Participatory Research

We found that some participatory approaches were more centered on action and systems change than others. For example, our analysis of terms indicated that action research and PAR were often applied within intervention studies to change material and structural processes (e.g., in health-care settings), whereas CBPR methods placed greater focus on relationship building over time, with less emphasis on outcomes of the collaborative research. Future participatory research studies might consider integrating community-level actions into their project design to ensure that this dimension of participatory research is attended to. This can include helping to strengthen a community group’s policy advocacy; enhancing the capacity of community stakeholders to conduct their own research and evaluation; helping to bring in additional funding, prestige, and resources to a community; and improving organizational or interorganizational practices (Caldwell et al., 2015; Huffman, 2017). In many cases, the “action” component of research is not singular, but rather a combination of these examples that together provide a benefit in the short- and long-term for the communities involved.

Limitations

Although participatory research was partially developed by Brazilian scholar Paolo Freire, only one study in our sample was from Latin America (Barros et al., 2020). This is a limitation of our study; given our English-language focus, it is probable that this literature is much larger in Latin America and other world regions than what is included here. We also only included studies that stated using a specific term to describe their use of a participatory approach. It is possible that participatory methods are being used more or differently than what we have documented in this review, but our search did not identify them without their use of key terms in the title, abstract, keywords, or body of their published paper. Relatedly, we only included peer-reviewed publications. A review of other types of publications, such as book chapters, dissertations, and “gray literature” reports, might have generated additional nuances to our findings. Also, as stated earlier, our review was designed to address breadth in the literature, as opposed to depth.

Conclusion

Strengthening the use, transparency, and rigor of participatory methods in ADRD research is especially important as leading voices in the field frame ADRD as a focal concern of health equity (Aranda et al., 2021; Bacsu et al., 2022; Bethell et al., 2018). The acceleration of professional norms and journal guidelines would help to better ensure that key information concerning participatory approaches is included as part of the scientific peer-review process. These developments would strengthen the use of participatory approaches in ADRD and are especially important considering growing attention to ADRD as a key health equity concern. The inequitable rates of risk of dementia and Alzheimer’s across racial groups coupled with the lack of structural support and integration of people with dementia in society leads to detrimental consequences for individuals, communities, and our society. These engaged research methods emerging from social justice philosophies would help push the field beyond just describing inequities and begin contextualizing these inequities within historical and sociopolitical processes that call for the collaboration and expertise of community members, practitioners, scholars, and policymakers to redress them through a multilevel systems approach.

Supplementary Material

Contributor Information

Laurent Reyes, School of Social Welfare, University of California, Berkeley, California, USA.

Clara J Scher, School of Social Work, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA.

Emily A Greenfield, School of Social Work, Rutgers University, New Brunswick, New Jersey, USA.

Funding

This work was supported, in part, by a grant from the National Institute on Aging at the National Institutes of Health (R01AG057491).

Conflict of Interest

None.

Ethical Approval

An ethical review was not required to complete this scoping review.

References

- Acharibasam, J. B., Chapados, M., Langan, J., Starblanket, D., & Hagel, M. (2022). Exploring health and wellness with First Nations communities at the “Knowing Your Health Symposium.” Healthcare Management Forum, 35(5), 265–271. 10.1177/08404704221084042 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ajrouch, K. J., Vega, I. E., Antonucci, T. C., Tarraf, W., Webster, N. J., & Zahodne, L. B. (2020). Partnering with middle Eastern/Arab American and Latino immigrant communities to increase participation in Alzheimer’s disease research. Ethnicity & Disease, 30, 765–774. 10.18865/ed.30.S2.765 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Alzheimer’s Association. (2023). 2023 Alzheimer’s disease facts and figures. https://www.alz.org/media/Documents/alzheimers-facts-and-figures.pdf

- Alzheimer’s Society. (n.d.). Alzheimer’s Society’s view on involving people with dementia. https://www.alzheimers.org.uk/about-us/policy-and-influencing/what-we-think/involving-people-dementia

- Andersson, N. (2018). Participatory research—A modernizing science for primary health care. Journal of General and Family Medicine, 19(5), 154–159. 10.1002/jgf2.187 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Andrews, S. M., Dipnall, J. F., Tichawangana, R., Hayes, K. J., Fitzgerald, J. A., Siddall, P., Poulos, C., & Cunningham, C. (2019). An exploration of pain documentation for people living with dementia in aged care services. Pain Management Nursing, 20(5), 475–481. 10.1016/j.pmn.2019.01.004 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Aranda, M. P., Kremer, I. N., Hinton, L., Zissimopoulos, J., Whitmer, R. A., Hummel, C. H., Trejo, L., & Fabius, C. (2021). Impact of dementia: Health disparities, population trends, care interventions, and economic costs. Journal of the American Geriatrics Society, 69(7), 1774–1783. 10.1111/jgs.17345 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Arksey, H., & O’Malley, L. (2005). Scoping studies: Towards a methodological framework. International Journal of Social Research Methodology, 8(1), 19–32. 10.1080/1364557032000119616 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Askari, N., Bilbrey, A. C., Garcia Ruiz, I., Humber, M. B., & Gallagher-Thompson, D. (2018). Dementia awareness campaign in the Latino community: A novel community engagement pilot training program with promotoras. Clinical Gerontologist, 41(3), 200–208. 10.1080/07317115.2017.1398799 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Austrom, M. G., Bachman, J., Altmeyer, L., Gao, S., & Farlow, M. (2010). A collaborative Alzheimer disease research exchange: Using a community-based helpline as a recruitment tool. Alzheimer Disease and Associated Disorders, 24(Suppl 1), S49–S53. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181f11f8d. Scopus [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Ayton, D., O’Donnell, R., Vicary, D., Bateman, C., Moran, C., Srikanth, V. K., Lustig, J., Banaszak-Holl, J., Hunter, P., Pritchard, E., Morris, H., Savaglio, M., Parikh, S., & Skouteris, H. (2020). Psychosocial volunteer support for older adults with cognitive impairment: Development of MyCare Ageing using a codesign approach via action research. BMJ Open, 10(9), e036449. 10.1136/bmjopen-2019-036449 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bacsu, J. -D. R., O’Connell, M. E., & Wighton, M. B. (2022). Improving the health equity and the human rights of Canadians with dementia through a social determinants approach: A call to action in the COVID-19 pandemic. Canadian Journal of Public Health; Revue Canadienne De Sante Publique, 113(2), 204–208. 10.17269/s41997-022-00618-8 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bardach, S. H., Yarbrough, M., Walker, C., Alfred, D. L., Ighodaro, E., Kiviniemi, M. T., & Jicha, G. A. (2021). Insights from African American older adults on brain health research engagement: “Need to See the Need.” Journal of Applied Gerontology, 40(2), 201–208. 10.1177/0733464820902002 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Barros, M., Zamberlan, C., Gehlen, M. H., Horbach da Rosa, P., & Ilha, S. (2020). Awareness raising workshop for nursing students on the elderly with Alzheimer’s disease: Contributions to education. Revista Brasileira de Enfermagem, 73, 1–8. 10.1590/0034-7167-2019-0021. CINAHL with Full Text [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Bethell, J., Commisso, E., Rostad, H. M., Puts, M., Babineau, J., Grinbergs-Saull, A., Wighton, M. B., Hammel, J., Doyle, E., Nadeau, S., & McGilton, K. S. (2018). Patient engagement in research related to dementia: A scoping review. Dementia (London, England), 17(8), 944–975. 10.1177/1471301218789292 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Brody, A. A., & Galvin, J. E. (2013). A review of interprofessional dissemination and education interventions for recognizing and managing dementia. Gerontology & Geriatrics Education, 34(3), 225–256. 10.1080/02701960.2013.801342 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Caldwell, W. B., Reyes, A. G., Rowe, Z., Weinert, J., & Israel, B. A. (2015). Community partner perspectives on benefits, challenges, facilitating factors, and lessons learned from community-based participatory research partnerships in Detroit. Progress in Community Health Partnerships: Research, Education, and Action, 9(2), 299–311. 10.1353/cpr.2015.0031 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Chambers, R. (1994). Paradigm shifts and the practice of participatory research and development. Institute for Development Studies at the University of Sussex Brighton England [Google Scholar]

- Chenoweth, L., & Kilstoff, K. (1998). Facilitating positive changes in community dementia management through participatory action research. International Journal of Nursing Practice (Wiley-Blackwell), 4(3), 175–188. 10.1046/j.1440-172x.1998.00063.x. CINAHL with Full Text [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cook, W. K. (2008). Integrating research and action: A systematic review of community-based participatory research to address health disparities in environmental and occupational health in the USA. Journal of Epidemiology & Community Health, 62(8), 668–676. 10.1136/jech.2007.067645 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cornect-Benoit, A., Pitawanakwat, K., Walker, J., Manitowabi, D., & Jacklin, K.; Wiikwemkoong Unceded Territory Collaborating First Nation Community (2020). Nurturing meaningful intergenerational social engagements to support healthy brain aging for Anishinaabe older adults. Canadian Journal on Aging, 39(2), 263–283. 10.1017/S0714980819000527. Scopus [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Cox, T., Hoang, H., Goldberg, L. R., & Baldock, D. (2019). Aboriginal community understandings of dementia and responses to dementia care. Public Health (Elsevier), 172, 15–21. 10.1016/j.puhe.2019.02.018. CINAHL with Full Text [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Davies, K., Lambert, H., Turner, A., Jenkins, E., Aston, V., & Rolfe, G. (2014). Making a difference: Using action research to explore our educational practice. Educational Action Research, 22(3), 380–396. 10.1080/09650792.2013.872575. Scopus [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dieter, J., McKim, L. T., Tickell, J., Bourassa, C. A., Lavallee, J., & Boehme, G. (2018). The path of creating co-researchers in the File Hills Qu’Appelle Tribal Council. International Indigenous Policy Journal, 9(4), 1–17. 10.18584/iipj.2018.9.4.1. Scopus [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Dupuis, S., McAiney, C., Loiselle, L., Hounam, B., Mann, J., & Wiersma, E. C. (2021). Use of participatory action research approach to develop a self-management resource for persons living with dementia. Dementia (14713012), 20(7), 2393–2411. 10.1177/1471301221997281. CINAHL with Full Text [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Etkin, C. D., Farran C. J., Barnes L. L., & Shah R. C. (2012). Recruitment and enrollment of caregivers for a lifestyle physical activity clinical trial. Research in Nursing & Health, 35(1), 70–81. 10.1002/nur.20466. CINAHL with Full Text [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Fals-Borda, O., & Rahman, M. A. (1991). Action and knowledge: Breaking the monopoly with participatory action research. Apex Press. [Google Scholar]

- Frank, L., Shubeck, E., Schicker, M., Webb, T., Maslow, K., Gitlin, L., Hummel, C. H., Kaplan, E. K., LeBlanc, B., Marquez, M., Nicholson, B., O’Brien, G., Phillips, L., Van Buren, B., & Epstein-Lubow, G. (2020). Contributions of persons living with dementia to scientific research meetings. Results from the national research summit on care, services, and supports for persons with dementia and their caregivers. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(4), 421–430. 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.10.014. Scopus [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Freire, P. (1968). Pedagogy of the oppressed. Continuum. [Google Scholar]

- Gaventa, J., & Cornwall, A. (2006). Challenging the boundaries of the possible: Participation, knowledge and power. IDS Bulletin, 37(6), 122–128. 10.1111/j.1759-5436.2006.tb00329.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Gilmore-Bykovskyi, A. L., Jin, Y., Gleason, C., Flowers-Benton, S., Block, L. M., Dilworth-Anderson, P., Barnes, L. L., Shah, M. N., & Zuelsdorff, M. (2019). Recruitment and retention of underrepresented populations in Alzheimer’s disease research: A systematic review. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: Translational Research & Clinical Interventions, 5, 751–770. 10.1016/j.trci.2019.09.018 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Glymour, M. M., & Manly, J. J. (2008). Lifecourse social conditions and racial and ethnic patterns of cognitive aging. Neuropsychology Review, 18(3), 223–254. 10.1007/s11065-008-9064-z [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Goeman, D., King, J., & Koch, S. (2016). Development of a model of dementia support and pathway for culturally and linguistically diverse communities using co-creation and participatory action research. BMJ Open, 6(12), 1–8. 10.1136/bmjopen-2016-013064. Scopus [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Grill, J. D., & Galvin, J. E. (2014). Facilitating Alzheimer disease research recruitment. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 28(1), 1–8. 10.1097/WAD.0000000000000016. CINAHL with Full Text [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Harkin, D., Coates, V., & Brown, D. (2022). Exploring ways to enhance pain management for older people with dementia in acute care settings using a Participatory Action Research approach. International Journal of Older People Nursing, 17(6), e12487. 10.1111/opn.12487 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Hendriks, N., Huybrechts, L., Slegers, K., & Wilkinson, A. (2018). Valuing implicit decision-making in participatory design: A relational approach in design with people with dementia. Design Studies, 59, 58–76. 10.1016/j.destud.2018.06.001 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hicks, B., Innes, A., & Nyman, S. R. (2020). Exploring the “active mechanisms” for engaging rural-dwelling older men with dementia in a community technological initiative. Ageing & Society, 40(9), 1906–1938. 10.1017/S0144686X19000357. CINAHL with Full Text [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Hong, M., Casado, B. L., & Lee, S. E. (2019). The intention to discuss advance care planning in the context of Alzheimer’s disease among Korean Americans. Gerontologist, 59(2), 347–355. 10.1093/geront/gnx211. Scopus [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Huffman, T. (2017). Participatory/action research/CBPR. In The international encyclopedia of communication research methods (pp. 1–10). John Wiley & Sons, Ltd. 10.1002/9781118901731.iecrm0180 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Israel, B. A., Coombe, C. M., Cheezum, R. R., Schulz, A. J., McGranaghan, R. J., Lichtenstein, R., Reyes, A. G., Clement, J., & Burris, A. (2010). Community-based participatory research: A capacity-building approach for policy advocacy aimed at eliminating health disparities. American Journal of Public Health, 100(11), 2094–2102. 10.2105/AJPH.2009.170506 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Jacklin, K., Pitawanakwat, K., Blind, M., O’Connell, M. E., Walker, J., Lemieux, A. M., & Warry, W. (2020). Developing the Canadian indigenous cognitive assessment for use with indigenous older Anishinaabe adults in Ontario, Canada. Innovation in Aging, 4(4), 1–13. 10.1093/geroni/igaa038 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kilstoff K., & Chenoweth L. (1998). New approaches to health and well-being for dementia day-care clients, family carers and day-care staff. International Journal of Nursing Practice (Wiley-Blackwell), 4(2), 70–83. 10.1046/j.1440-172x.1998.00059.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Kowe, A., Panjaitan, H., Klein, O. A., Boccardi, M., Roes, M., Teupen, S., & Teipel, S. (2022). The impact of participatory dementia research on researchers: A systematic review. Dementia, 21(3), 1012–1031. 10.1177/14713012211067020 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lee, C., Mellor, T., Dilworth-Anderson, P., Young, T., Brayne, C., & Lafortune, L. (2018). Opportunities and challenges in public and community engagement: The connected for cognitive health in later life (CHILL) project. Research Involvement and Engagement, 4(1), 2–12. 10.1186/s40900-018-0127-x [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Levac, D., Colquhoun, H., & O’Brien, K. K. (2010). Scoping studies: Advancing the methodology. Implementation Science, 5(1), 69. 10.1186/1748-5908-5-69 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lewin, K. (1946). Action research and minority problems. Journal of Social Issues, 2(4), 34–46. 10.1111/j.1540-4560.1946.tb02295.x [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lhimsoonthon, B., Sritanyarat, W., & Rungrengkolkit, S. (2019). Development of care services for older people with dementia in a primary care setting. Pacific Rim International Journal of Nursing Research, 23(3), 214–227. [Google Scholar]

- Li, B. Y., & Ho, R. T. H. (2019). Unveiling the unspeakable: Integrating video elicitation focus group interviews and participatory video in an action research project on dementia care development. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 18. 10.1177/1609406919830561 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Lindgren, H., Winnberg, P. J., & Yan, C. (2012). Collaborative development of knowledge-based support systems: A case study. Studies in Health Technology & Informatics, 180, 1111–11113. 10.3233/978-1-61499-101-4-1111 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Lindhult, E. (2022). The movement toward knowledge democracy in participatory and action research. In Bacal Roij A. (Ed.), Transformative research and higher education (pp. 107–128). Emerald Publishing Limited. 10.1108/978-1-80117-694-120221006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Macaulay, A. C (2017). Participatory research: What is the history? Has the purpose changed? Family Practice, 34(3), 256–258. 10.1093/fampra/cmw117 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- MacDonald, C. J., Stodel, E. J., Casimiro, L., & Weaver, L. (2006). Using community-based participatory research for an online dementia care program. Canadian Journal of Program Evaluation, 21(2), 81–104. 10.3138/cjpe.21.004. https://www.scopus.com/inward/record.uri?eid=2-s2.0-34250344255&partnerID=40&md5=f37605755dcddb182cafc758c4ff661d [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Minkler, M. (Ed.). (2012). Community organizing and community building for health and welfare. Rutgers University Press. [Google Scholar]

- Mitchell, B., Jackson, G. A., Sharp, B., & Tolson, D. (2020). Complementary therapy for advanced dementia palliation in nursing homes. Journal of Integrated Care, 28(4), 419–432. 10.1108/jica-02-2020-0009 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Mockford, C., Murray, M., Seers, K., Oyebode, J., Grant, R., Boex, S., Staniszewska, S., Diment, Y., Leach, J., Sharma, U., Clarke, R., & Suleman, R. (2016). A SHARED study—The benefits and costs of setting up a health research study involving lay co-researchers and how we overcame the challenges. Research Involvement and Engagement, 2(1), 8. 10.1186/s40900-016-0021-3 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moher, D., Liberati, A., Tetzlaff, J., & Altman, D. G.; PRISMA Group (2009). Preferred reporting items for systematic reviews and meta-analyses: The PRISMA statement. BMJ, 339, b2535. 10.1136/bmj.b2535 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Moon, H., Badana, A. N. S., Hwang, S.-Y., Sears, J. S., & Haley, W. E. (2019). Dementia prevalence in older adults: Variation by race/ethnicity and immigrant status. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 27(3), 241–250. 10.1016/j.jagp.2018.11.003 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Morhardt, D., Pereyra, M., & Iris, M. (2010). Seeking a diagnosis for memory problems: The experiences of caregivers and families in 5 limited English proficiency communities. Alzheimer Disease & Associated Disorders, 24, S42–S88. 10.1097/WAD.0b013e3181f14ad5 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- National Institute on Aging. (n.d.). International Alzheimer’s and related dementias research portfolio (IADRP). National Institute on Aging. https://www.nia.nih.gov/research/dn/international-alzheimers-and-related-dementias-research-portfolio-iadrp [Google Scholar]

- Nielsen, T. R., Nielsen, D. S., & Waldemar, G. (2022). Feasibility of a culturally tailored dementia information program for minority ethnic communities in Denmark. International Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 37(1), 1–8. 10.1002/gps.5656 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pace, J. (2020). “Place-ing” dementia prevention and care in NunatuKavut, Labrador. Canadian Journal on Aging = La Revue Canadienne Du Vieillissement, 39(2), 247–262. 10.1017/S0714980819000576 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Pain, R., & Francis, P. (2003). Reflections on participatory research. Area, 35(1), 46–54. 10.1111/1475-4762.00109 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Park, V. M., Meyer, O. L., Tsoh, J. Y., Kanaya, A. M., Tzuang, M., Nam, B., Vuong, Q., Bang, J., Hinton, L., Gallagher-Thompson, D., & Grill, J. D. (2022). The Collaborative Approach for Asian Americans and Pacific Islanders Research and Education (CARE): A recruitment registry for Alzheimer’s disease and related dementias, aging, and caregiver-related research. Alzheimer’s & Dementia: The Journal of the Alzheimer’s Association, 19(2). 10.1002/alz.12667 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Parker, L. J., Gaugler, J. E., & Gitlin, L. N. (2022). Use of critical race theory to inform the recruitment of Black/African American Alzheimer’s disease caregivers into community-based research. Gerontologist, 62(5), 742–750. 10.1093/geront/gnac001 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Peters, M. D. J., Marnie, C., Tricco, A. C., Pollock, D., Munn, Z., Alexander, L., McInerney, P., Godfrey, C. M., & Khalil, H. (2020). Updated methodological guidance for the conduct of scoping reviews. JBI Evidence Synthesis, 18(10), 2119–2126. 10.11124/JBIES-20-00167 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Phillipson, L., & Hammond, A. (2018). More than talking: A scoping review of innovative approaches to qualitative research involving people with dementia. International Journal of Qualitative Methods, 17(1), 160940691878278. 10.1177/1609406918782784 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Pohl, D. J., Seblova, D., Avila, J. F., Dorsman, K. A., Kulick, E. R., Casey, J. A., & Manly, J. (2021). Relationship between residential segregation, later-life cognition, and incident dementia across race/ethnicity. International Journal of Environmental Research and Public Health, 18(21), 11233. 10.3390/ijerph182111233 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reuben, D. B. (2020). The voices of persons living with dementia. American Journal of Geriatric Psychiatry, 28(4), 443–444. 10.1016/j.jagp.2019.11.005 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Reyes, L., Shellae Versey, H., & Yeh, J. (2022). Emancipatory visions: Using visual methods to coconstruct knowledge with older adults. Gerontologist, 62(10), 1402–1408. 10.1093/geront/gnac046 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Rolfe, G. A. R. Y., & Phillips, L. M. (1995). An action research project to develop and evaluate the role of an advanced nurse practitioner in dementia. Journal of Clinical Nursing, 4(5), 289–293. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Selener, D. (1997). Participatory action research and social change. Cornell Participatory Action Research Network, Cornell University. [Google Scholar]

- Sprange, K., Beresford-Dent, J., Mountain, G., Thomas, B., Wright, J., Mason, C., & Cooper, C. L. (2021). Journeying through dementia randomised controlled trial of a psychosocial intervention for people living with early dementia: Embedded qualitative study with participants, carers and interventionists. Clinical Interventions in Aging, 16, 231–244. 10.2147/CIA.S293921 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Suijkerbuijk, S., Nap, H. H., Cornelisse, L., IJsselsteijn, W. A., de Kort, Y. A. W., & Minkman, M. M. N. (2019). Active involvement of people with dementia: A systematic review of studies developing supportive technologies. Journal of Alzheimer’s Disease: JAD, 69(4), 1041–1065. 10.3233/JAD-190050 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Super, N., & Ty, D. (2022). Multisectoral collaboration to improve dementia care. Public Policy & Aging Report, 32(2), 80–83. 10.1093/ppar/prac006 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- Tan, E. J., McGill, S., Tanner, E. K., Carlson, M. C., Rebok, G. W., Seeman, T. E., Fried, L. P., & Van Haitsma, K. (2014). The evolution of an academic–community partnership in the design, implementation, and evaluation of Experience Corps® Baltimore City: A courtship model. Gerontologist, 54(2), 314–321. 10.1093/geront/gnt072 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tanner, D. (2012). Co-research with older people with dementia: Experience and reflections. Journal of Mental Health, 21(3), 296–306. 10.3109/09638237.2011.651658 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Torres, V. N., Williams, E. C., Ceballos, R. M., Donovan, D. M., Duran, B., & Ornelas, I. J. (2020). Participant engagement in a community based participatory research study to reduce alcohol use among Latino immigrant men. Health Education Research, 35(6), 627–636. 10.1093/her/cyaa039 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Tricco, A. C., Lillie, E., Zarin, W., O’Brien, K. K., Colquhoun, H., Levac, D., Moher, D., Peters, M. D. J., Horsley, T., Weeks, L., Hempel, S., Akl, E. A., Chang, C., McGowan, J., Stewart, L., Hartling, L., Aldcroft, A., Wilson, M. G., Garritty, C., … Straus, S. E. (2018). PRISMA extension for scoping reviews (PRISMA-SCR): Checklist and explanation. Annals of Internal Medicine, 169(7), 467–473. 10.7326/M18-0850 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Vaismoradi, M., Turunen, H., & Bondas, T. (2013). Content analysis and thematic analysis: Implications for conducting a qualitative descriptive study. Nursing & Health Sciences, 15(3), 398–405. 10.1111/nhs.12048 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Walker, J. D., O’connell, M. E., Pitawanakwat, K., Blind, M., Warry, W., Lemieux, A., Patterson, C., Allaby, C., Valvasori, M., Zhao, Y., & Jacklin, K. (2021). Canadian indigenous cognitive assessment (CICA): Inter-rater reliability and criterion validity in anishinaabe communities on Manitoulin Island, Canada. Alzheimer’s and Dementia: Diagnosis, Assessment and Disease Monitoring, 13(1), e12213. 10.1002/dad2.12213 [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- Wallerstein, N., Duran, B., Oetzel, J. G., & Minkler, M. (2017). Community-based participatory research for health: Advancing social and health equity. John Wiley & Sons. [Google Scholar]

- Webkamigad, S., Cote-Meek, S., Pianosi, B., & Jacklin, K. (2020). Exploring the appropriateness of culturally safe dementia information with indigenous people in an urban northern Ontario community. Canadian Journal on Aging, 39(2), 235–246. 10.1017/S0714980819000606 [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.