Abstract

No data on the quality of life (QOL) of the general population are available for Mongolia. This study aimed to determine normative data on the World Health Organization Quality of Life-Brief Version (WHOQOL-BREF) in the general population of Mongolia. This nationwide, population-based, cross-sectional study was conducted in 48 sampling centers across Mongolia in 2020. We used the WHOQOL-BREF and the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in our study and evaluated their associations with vital signs, body measurements, and lifestyle determinants. A total of 714 participants (261 men and 453 women) with a mean (standard deviation) age of 40.7 (13.2) years were recruited. The mean scores of WHOQOL-BREF subscales were 61.5 for physical health, 73.5 for psychological health, 70.1 for social relationship, and 67.2 for environmental health domains. The prevalence of poor QOL was 16.9% among the participants. Participants living in an apartment in urban areas with high HADS scores had a low QOL. All domains of WHOQOL-BREF were inversely correlated with anxiety score (r = -0.353 ‐ -0.206, p < 0.001) and depression scores (r = -0.335 ‐ -0.156, p < 0.001). Physical health was predicted by residency location, anxiety, and depression (R2 = 0.200, p < 0.001); psychological health by anxiety and depression (R2 = 0.203, p < 0.001); social relationship by residency location, age group, anxiety and depression (R2 = 0.116, p < 0.001); and environmental health by employment, anxiety, and depression (R2 = 0.117, p < 0.001). This is the first report on normative data on the QOL in the general population of Mongolia. Physical health was low compared with that determined using international data. Poor QOL was observed among those with mental health issues living in the urban areas.

Introduction

Mongolia has a small population but a large geographical area. More than half of the population lives in rural areas as nomadic herders in a traditional pelt tent called a ger [1]. Gers are not provided with central electricity, water, sanitation, or heating systems. Conversely, urban residents who predominantly reside in apartments benefit from a connection to centralized utilities, including winter heating systems. Notably, a significant proportion of these structures were constructed several decades ago, adhering to Soviet-era standard panel building designs [2]. A large part of the country is arid and extremely cold, with January averages dropping as low as -30°C. The capital city, Ulaanbaatar, makes up most of the urban areas, whereas prefecture centers play marginal roles because of the lack of infrastructure required for modern cities. Ulaanbaatar is the coldest capital city in the world, with an annual average temperature of -1°C [3]. The rural areas are divided into four regions: eastern, western, mountain (Khangai), and central. Each region has three to seven geopolitical prefectures. Since 1990, after the democratic revolution, the rural population has migrated to Ulaanbaatar, surpassing a million residents. This migration has expanded ger areas in Ulaanbaatar making it one of the most air-polluted cities in the world [4]. While some family households within Ulaanbaatar’s ger areas possess conventional houses, comprehensive central utility systems remain absent, with the exception of electricity. Consequently, living conditions in Mongolia diverge significantly from those commonly perceived in Western countries.

Because of the politico-economical changes, Mongolia’s disease burden has shifted from communicable to non-communicable diseases [5]. This rapid alteration in disease burden might have affected younger people more than older residents, similar to other developing countries [6]. To meet the shift in disease burden, Mongolia has to establish appropriate policies to improve the efficacy of healthcare services by monitoring the quality of life nationwide (QOL). The use of a QOL assessment instrument is generally recommended for evaluating the effectiveness of preventive, diagnostic, and treatment measures.

Notably, no studies have assessed the QOL of the general population in Mongolia. In particular, the political transition from communism to democracy, rapid urbanization, air pollution, lifestyle changes, the shift in disease burden, and economic turbulence over the past 3 decades should have largely impacted the QOL of the Mongolian people. Including these factors, the subjective perception of QOL among Mongolian people may deviate from international standards.

QOL assessment instruments, such as the Short-Form Health Survey (SF-36), EuroQOL (EQ-5D), and World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL-100), have been examined in terms of validity and reliability across different cultures. Among them, the WHOQOL-100 was developed by WHO experts with simultaneous consideration of the context of the cultural aspects in 15 international field centers. The abbreviated version, the brief version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life (WHOQOL-BREF), is a concise self-report questionnaire that assesses health-related QOL in both general and clinical populations. It consists of 24 Likert-scale items representing four latent domains: physical health, psychological health, social relationships, and environmental health. Two additional exclusive questions from the measurement model estimate the participant’s satisfaction with their life and general health [7]. We translated and determined the psychometric properties of WHOQOL-BREF in the general population of Ulaanbaatar in our previous study [8]. Our results demonstrate that the Mongolian version of WHOQOL-BREF has good validity and reliability for assessing QOL in the general population. Using the same tool, this study aimed to establish normative data on QOL in the Mongolian population. Furthermore, sociodemographic, physical, and psychological characteristics of the Mongolian population have been extensively investigated to determine factors associated with the QOL.

Materials and methods

Study participants

This study was part of a nationwide, multicenter, interdisciplinary, prospective, population-based cohort study that investigated brain-related disorders in the general population of Mongolia by the Brain Science Institute at the Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences.

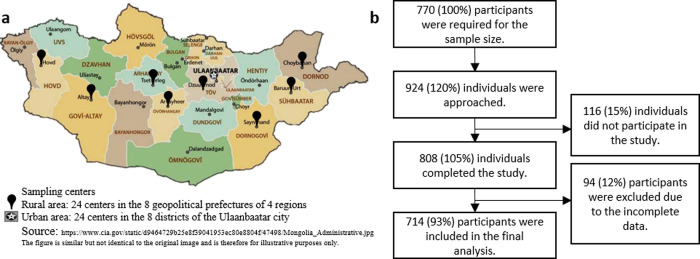

In this cross-sectional study, the sample size was calculated to be 385 for a population size of 1,910,630 individuals aged 18–65 years in Mongolia [1]. According to the 2020 census, 47% of the population lived in the capital city of Ulaanbaatar, and the remaining lived in four rural regions. To cover a full representative population of the rural regions, we included two residency locations (urban and rural areas), resulting in the desired sample size of 770. Considering a response rate of 80%, 924 individuals who fulfilled the inclusion criteria were invited to participate in the study. Mongolian citizens who lived in geopolitical units for at least 6 months were considered to meet inclusion criteria. The participants were recruited from 48 sampling centers, including 24 primary health centers in 8 districts in Ulaanbaatar and 24 primary health centers in 8 prefectures of 4 rural regions across the country (Fig 1A).

Fig 1. Study flowchart and sampling sites.

a) Sampling sites across the country. The study consisted of 48 sampling centers, including 24 in 8 districts of Ulaanbaatar and 24 in 8 prefectures of 4 rural regions. b) Study flowchart: The required sample size was 770. We invited 924 individuals to participate in this study. Among them, 116 refused, and 94 participants were excluded due to the missing data. A total of 714 participants were included in the final analysis.

The sampling centers were located at primary health centers where the entire population was registered six age-sex groups (18–29, 30–44, 45–65 years; men and women) to create a representative sample that matches the age and sex distribution of the population. Depending on the population density, two or three individuals for each age-sex group from a sampling center were randomly selected using a computer program. Among the invited individuals, 116 did not reach the sampling center on a given date and time. A total of 808 participants completed the survey, and 94 of whom had missing data. The remaining 714 participants were included in the final analysis (Fig 1B).

Data collection

The data collection started on September 7, 2020, and was completed on November 29, 2020. The study was conducted in the official language (Mongolian). Trained research personnel or medical doctors explained the WHOQOL-BREF questionnaire to the participants face-to-face and helped them to respond using a tablet. In addition, demographic characteristics and lifestyle data were collected. Height, weight, waist circumference, and neck circumference were also measured. To determine the current physical health status, four primary vital signs were examined noninvasively by trained research personnel or medical doctors: body temperature at the forehead or wrest with an electronic infrared thermometer (Tida, TD-133, China), blood pressure and heart rate using an advanced blood pressure monitor (BP A6 PC, Microlife, Switzerland), and arterial oxygen saturation (SpO2) using a pulse oximetry (PO40, Beurer, Germany). Blood pressure, heart rate, and arterial oxygen saturation were assessed in accordance with the WHO’s guidelines on the measurement of these vital signs [9,10].

Instruments

The WHOQOL-BREF), one of the most commonly used generic QOL questionnaires, was developed by the WHOQOL group in 1996 [11]. The WHOQOL-BREF is open-source, and accessible for non-commercial use, and translated into more than 40 languages. This method is suitable for large-sample surveys and clinical trials. This 24-item questionnaire determines QOL using four domain scores: physical health (questions 3,4,10,15–18), psychological health (questions 5–7,11,19,26), social relationships (questions 20–22), and environmental health (questions 8–9, 12–14, 23–25). Each item is measured on a 5-point Likert-scale. The score of each domain consists of the mean score of items multiplied by four, in which a higher score indicates a better QOL. Each domain score is converted to a scale of 0–100. Two more items on the perception of overall QOL and general health were aggregated to the general facet, which was also converted to a scale of 0–100 [12]. We translated the WHOQOL-BREF into Mongolian based on the cross-cultural adaptation guideline and described its psychometric properties in our previous study [8]. The translated version showed a good fit for validity and reliability in the general population. To confirm the previous results, we calculated the Cronbach’s alpha coefficients for all domains of the WHOQOL-BREF. Cronbach`s alpha was 0.84 for the total scale, and 0.84, 0.79, 0.81, and 0.76 for the physical health, psychological health, social relationship, and environmental health domains, respectively.

The Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) is a 14-item self-report questionnaire widely used to evaluate the severity of anxiety and depression symptoms in the past week. It was developed to identify mental symptoms, including anxiety and depression, in the general population and patients in clinical settings [13]. Among the 14 items, 7 were for anxiety (HADS-A subscale), and the remaining 7 were for depression (HADS-D subscale) formulated in a readily understandable language. Each item was rated on a 4-point scale from 0 to 3 for a total score between 0 and 21 for each subscale. The ranges of scores for cases on each subscale were 0–7, normal; 8–10, mild abnormality; 11–14, moderate abnormality; and 15–21, severe abnormality. The HADS has been translated into Mongolian and has good psychometric properties [14].

Statistical analysis

Data were presented as mean ± standard deviation (SD). The distributions of continuous variables were evaluated by Shapiro-Wilk test. Differences between the two groups were examined using the χ2 test for categorical data and Mann-Whitney U-test for continuous data. To determine differences in the domain scores between sociodemographic characteristics for each group (rural vs. urban areas; gers vs. apartments), a one-way ANOVA or t-test was performed, as appropriate. To estimate the prevalence of poor QOL, cut-off points for each subscale domain of the WHOQOL-BREF were established by dichotomizing the domain score at 1 SD below the mean of domain score in the participants of this study [15]. Correlation analyses between continuous variables were performed using Spearman’s bivariate test. Multiple linear regression analyses with the backward stepwise method were used to determine if factors (independent variables: all variables, including sociodemographic characteristics, body measurements, vital signs, and HADS scores) were associated with the mean scores of each domain of the WHOQOL-BREF (dependent variables: physical health, psychological health, social relationship, and environmental health domains). In the residency location variable, we used capital city Ulaanbaatar as the reference group. The remaining four rural regions were combined into one category. Multicollinearity was examined using variance inflation factor (VIF) and tolerance (1 < VIF < 2.5; tolerance < 10). Homoscedasticity was assessed using scatter plots of residuals by predicted values. No outliers were detected (Cook’s distance, < 1; standard residuals < ±3.3). The independence assumption was tested using the Durbin–Watson coefficient (satisfied if 1.5 < Durbin–Watson < 2.5). To construct a receiver operating characteristic (ROC) curve, the general facet variable was dichotomized at 1 SD below the mean score. Using the new nominal variable, we evaluated the screening ability of the WHOQOL-BREF domains at a range of cut-off points.

All statistical tests were two-tailed with a statistical significance set at p < 0.05. Data were analyzed using SPSS v26.0 and JAMOVI v2.2.5.

Ethical considerations

Written informed consent was obtained from all participants. The Institutional Review Board and Ethics Committee of the Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences (MNUMS) approved the study protocol and procedures for obtaining informed consent (number: 2020/03-05).

Results

There were 714 participants (261 men and 453 women) aged 18–65 years, with a mean ± SD of 40.7 ± 13.2 years. The details of the sociodemographic characteristics are described in Table 1. Because the participants had more females and were older, we adjusted for age and sex for further analyses by weighting them with the population report from the 2020 Population and Housing By-Census of Mongolia. The descriptive results suggested that the sample population represented the general population of the country (S1 Table). There were no missing data, except for 91 and 108 participants who did not report alcohol and tobacco use, respectively.

Table 1. Sociodemographic characteristics of the participants by sex.

| Characteristics, n (%) | Total | Male | Female | p value* | |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Total | 714 (100) | 261 (100) | 453 (100) | ||

| Age group | 18–29 | 181 (25.4) | 52 (19.9) | 129 (28.5) | < 0.001 |

| 30–44 | 248 (34.7) | 83 (31.8) | 165 (36.4) | ||

| 45–65 | 285 (39.9) | 126 (48.3) | 159 (35.1) | ||

| Marital status | Never-married | 119 (16.7) | 50 (19.2) | 69 (15.2) | 0.526 |

| Others# | 76 (10.6) | 21 (8.0) | 55 (12.1) | ||

| Married | 519 (72.7) | 190 (72.8) | 329 (72.6) | ||

| Education | Middle school and below | 302 (42.3) | 134 (51.3) | 168 (37.1) | < 0.001 |

| Associate’s degree | 186 (26.1) | 61 (23.4) | 125 (27.6) | ||

| Bachelor’s degree | 193 (27.0) | 56 (21.5) | 137 (30.2) | ||

| Master’s degree and above | 33 (4.6) | 10 (3.8) | 23 (5.1) | ||

| Employment | Unemployed | 88 (12.3) | 24 (9.2) | 64 (14.1) | 0.545 |

| Student | 84 (11.8) | 35 (13.4) | 49 (10.8) | ||

| Pensioner | 140 (19.6) | 59 (22.6) | 81 (17.9) | ||

| Employed | 402 (56.3) | 143 (54.8) | 259 (57.2) | ||

| Income | < ₮500,000 | 434 (60.8) | 154 (59.0) | 280 (61.8) | 0.295 |

| ₮500,001 - ₮1,000,000 | 258 (36.1) | 96 (36.8) | 162 (35.8) | ||

| > ₮1,000,000 | 22 (3.1) | 11 (4.0) | 11 (2.4) | ||

| Living condition | Ger (traditional pelt tent) | 211 (29.6) | 73.0 (28.0) | 138 (30.5) | 0.989 |

| House | 223 (31.2) | 88 (33.7) | 135 (29.8) | ||

| Dormitory | 42 (5.9) | 15.0 (5.7) | 27 (6.0) | ||

| Apartment | 238 (33.3) | 85 (32.6) | 153 (33.8) | ||

| Residency location | Eastern region | 84 (11.8) | 42 (16.1) | 42 (9.3) | 0.001 |

| Western region | 107 (15.0) | 52 (19.9) | 55 (12.1) | ||

| Mountain region | 110 (15.4) | 36 (13.8) | 74 (16.3) | ||

| Central region | 101 (14.1) | 24 (9.2) | 77 (17.0) | ||

| Ulaanbaatar city | 312 (43.7) | 107 (41.0) | 205 (45.3) | ||

| Alcohol use | Yes | 183 (29.6) | 55 (28.1) | 128 (30.3) | 0.578 |

| No | 436 (70.4) | 141 (71.9) | 295 (69.7) | ||

| Tobacco use | Yes | 127 (20.3) | 55 (27.2) | 72 (17.0) | 0.011 |

| No | 479 (76.6) | 141 (69.8) | 338 (79.9) | ||

| Had smoked before | 19 (3.0) | 6 (3.0) | 13 (3.1) | ||

| Continuous variables, mean ± SD | |||||

| Age | 40.7±13.2 | 42.7±13.2 | 39.5±13.1 | 0.002 | |

| Vital signs | Body temperature | 36.4±0.3 | 36.4±0.3 | 36.4±0.3 | 0.326 |

| Heart rate (per minute) | 78.2±11.4 | 77.8±12.5 | 78.4±10.8 | 0.288 | |

| Arterial systolic pressure | 126.1±19.2 | 130.9±19.6 | 123.4±18.4 | < 0.001 | |

| Arterial diastolic pressure | 80.4±12.9 | 83.6±13.0 | 78.5±12.5 | < 0.001 | |

| Arterial oxygen saturation | 95.0±2.2 | 95.2±2.2 | 94.8±2.2 | 0.030 | |

| Body mass index (BMI) | 26.9±5.5 | 27.3±5.4 | 26.7±5.5 | 0.161 | |

| Psychological symptoms (HADS score) |

Anxiety | 6.2±3.2 | 6.1±3.1 | 6.3±2.3 | 0.706 |

| Depression | 5.8±2.1 | 5.8±2.7 | 5.8±2.9 | 0.633 | |

* p values were analyzed with the Chi-square test and Mann-Whitney U-test.

# Others included remarried, co-habiting, separated, divorced, and widowed. ₮: Mongolian tugrik (MNT₮), US $1 = MNT ₮2850. HADS: Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale. n: Number. SD: Standard deviation. There was no missing data, except for 91 and 108 participants who did not report alcohol and tobacco use, respectively.

There were no differences in marital status, employment, income, living condition, alcohol use, body temperature, heart rate, body mass index (BMI), and psychological symptoms between men and women. Women were more educated, lived more in urban areas, smoked less, and had less blood pressure. The average monthly expenditure was 215,000 Mongolian tugrik (₮) ($1 = ₮2850), and the minimum monthly income was ₮320,000. Of the participants, 60.8% received less than ₮500,000 (low income), 36.1% received ₮500,000–1,000,000 (middle income), and 3.1% received more than ₮1,000,000 (high income). Approximately 30% of the sample population lived in traditional gers. However, another 30% lived in houses that were usually not connected with water, sanitation, and heating system, except electricity.

Table 2 shows the mean and SD of each domain of the WHOQOL-BREF and general facet by sociodemographic characteristics among the 714 participants.

Table 2. Normative values of the WHOQOL-BREF scores by sociodemographic characteristics.

| Characteristics (n) | WHOQOL domains (mean ± SD) | Perception | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHY | PSY | SOC | ENV | GEN | ||

| Total, unadjusted (714) | 61.5±12.6 | 73.6±12.1 | 70.4±15.9 | 67.6±13.4 | 70.5±15.1 | |

| Total, age and sex adjusted (714) | 61.5±1.7 | 73.5±2.2 | 70.1±2.2 | 67.2±1.9 | 70.6±1.8 | |

| Male (261) | 18–29 (52) | 59.7±14.5 | 69.2±17.4 | 63.1±21.7 | 63.2±17.6 | 70.4±19.5 |

| 30–44 (83) | 63.5±13.3 | 76.4±11.7 | 73.7±15.6 | 67.8±13.6 | 72.4±13.5 | |

| 45–65 (126) | 60.9±13.1 | 73.7±10.9 | 69.8±13.7 | 66.8±12.5 | 70.7±14.0 | |

| All male, age-adjusted (261) | 61.6±4.0 | 73.4±5.1 | 69.4±5.4 | 66.1±4.3 | 71.3±4.3 | |

| Female (453) | 18–29 (129) | 61.8±13.2 | 73.0±13.0 | 73.3±17.6 | 69.4±14.3 | 72.5±15.7 |

| 30–44 (165) | 61.3±12.1 | 73.6±12.1 | 70.8±15.9 | 67.4±13.5 | 68.6±16.5 | |

| 45–65 (159) | 61.3±11.2 | 73.7±9.9 | 68.7±12.8 | 68.3±11.2 | 69.5±12.9 | |

| All female, age-adjusted (453) | 61.4±3.5 | 73.5±4.4 | 70.8±3.8 | 68.3±3.7 | 70.0±3.5 | |

| Marital status | Never-married (119) | 60.4±13.1 | 71.1±13.4 | 68.3±17.3 | 66.2±14.8 | 72.1±15.4 |

| Others* (76) | 62.5±10.8 | 75.7±2.3 | 72.7±13.3 | 69.7±9.8 | 70.1±13.1 | |

| Married (519) | 61.6±12.8 | 73.8±12.2 | 70.5±15.9 | 67.6±13.5 | 70.2±15.3 | |

| Education | Middle school and below (302) | 62.5±12.3 | 74.1±12.5 | 70.7±15.2 | 68.1±13.2 | 71.4±15.6 |

| Associate’s degree (186) | 61.7±12.2 | 73.8±11.1 | 71.5±14.3 | 67.9±12.8 | 70.2±14.2 | |

| Bachelor’s degree (193) | 59.8±13.6 | 72.2±12.6 | 68.2±18.3 | 66.6±14.4 | 69.4±15.6 | |

| Master’s degree and above (33) | 60.3±11.5 | 75.4±10.3 | 74.5±14.0 | 67.8±13.2 | 70.1±12.5 | |

| Employment | Unemployed (88) | 60.4±12.4 | 72.9±11.3 | 70.6±15.7 | 66.4±14.3 | 70.2±15.2 |

| Student (84) | 62.3±12.9 | 73.4±14.3 | 71.0±19.5 | 67.0±15.5 | 75.3±17.0 | |

| Pensioner (140) | 61.2±12.5 | 72.6±10.8 | 68.2±13.6 | 71.0±15.8 | 69.9±14.5 | |

| Employed (402) | 61.6±12.7 | 74.0±12.2 | 71.0±15.8 | 68.2±13.1 | 69.7±14.7 | |

| Income | < ₮500,000 (434) | 61.4±12.9 | 73.4±12.0 | 70.0±16.0 | 67.5±13.6 | 71.1±15.2 |

| ₮500,001 - ₮1,000,000 (258) | 61.5±12.5 | 73.6±12.0 | 71.0±16.0 | 67.8±13.2 | 69.7±15.1 | |

| > ₮1,000,001 (22) | 61.4±10.4 | 75.2±14.2 | 70.8±13.5 | 67.0±11.7 | 67.0±13.1 | |

| Living condition | Ger (traditional pelt tent) (211) | 63.4±12.9 | 75.0±10.7 | 71.3±14.0 | 69.3±12.5 | 71.1±13.6 |

| House (223) | 61.1±12.4 | 73.4±11.9 | 71.0±15.6 | 68.0±13.4 | 69.7±15.0 | |

| Dormitory (42) | 62.5±13.2 | 74.5±14.6 | 71.6±19.9 | 66.8±13.5 | 78.3±18.1 | |

| Apartment (238) | 60.0±12.4 | 72.3±12.7 | 68.7±16.8 | 65.8±14.1 | 69.2±15.5 | |

| Residency location | Eastern region (84) | 64.0±12.9 | 75.0±10.8 | 73.8±13.7 | 67.9±12.3 | 70.7±14.6 |

| Western region (107) | 65.7±10.0 | 72.2±11.3 | 72.3±13.8 | 69.0±12.2 | 73.5±13.0 | |

| Mountain region (110) | 64.5±12.4 | 75.2±9.2 | 70.5±12.8 | 68.9±11.4 | 71.3±12.6 | |

| Central region (101) | 61.2±12.0 | 72.7±14.7 | 69.7±19.3 | 67.4±15.1 | 70.0±18.2 | |

| Ulaanbaatar city (312) | 58.4±12.9 | 72.4±12.5 | 70.4±15.9 | 66.6±14.1 | 69.2±15.5 | |

| Alcohol use | Yes (183) | 60.7±13.8 | 73.4±12.3 | 69.3±18.4 | 67.0±13.9 | 68.8±14.8 |

| No (436) | 61.6±12.4 | 73.5±12.1 | 70.8±14.7 | 68.0±13.2 | 70.9±15.2 | |

| Tobacco use | Yes (127) | 62.3±12.7 | 73.4±13.4 | 71.1±16.2 | 68.8±13.8 | 70.9±16.4 |

| No (479) | 61.3±12.5 | 73.6±11.7 | 70.4±15.5 | 67.6±12.9 | 70.4±14.5 | |

| Had smoked before (19) | 58.3±13.1 | 71.1±14.4 | 67.5±20.0 | 65.1±15.8 | 67.1±19.2 | |

| BMI ranges | Underweight (10) | 64.3±10.9 | 78.3±6.1 | 75.8±12.7 | 71.3±12.0 | 71.3±20.5 |

| Normal weight (248) | 61.8±13.1 | 73.0±13.4 | 70.5±17.0 | 67.7±13.7 | 70.8±16.2 | |

| Pre-obesity (202) | 60.7±12.2 | 74.1±11.3 | 70.8±15.1 | 67.8±12.8 | 70.4±13.5 | |

| Obesity class I (114) | 62.4±12.1 | 74.1±10.5 | 70.2±14.2 | 68.0±12.9 | 70.5±14.1 | |

| Obesity class II (40) | 60.6±12.5 | 70.7±12.9 | 69.2±17.2 | 67.3±15.0 | 68.4±15.0 | |

| Obesity class III (13) | 54.4±12.8 | 70.2±11.9 | 60.9±14.2 | 62.0±15.3 | 66.3±14.8 | |

| Anxiety level | Normal (482) | 64.1±11.7 | 76.0±11.0 | 72.5±15.1 | 69.6±12.7 | 72.6±14.4 |

| Borderline normal (157) | 56.7±13.0 | 70.3±12.0 | 66.6±16.1 | 63.4±13.0 | 67.0±15.3 | |

| Abnormal (75) | 54.5±12.1 | 64.8±13.2 | 64.8±17.6 | 63.3±15.8 | 64.2±16.4 | |

| Depression level | Normal (535) | 63.6±11.5 | 75.7±10.4 | 72.4±14.5 | 69.2±12.2 | 71.7±14.3 |

| Borderline normal (137) | 54.9±13.6 | 67.4±13.4 | 65.6±18.4 | 62.5±15.4 | 66.6±17.1 | |

| Abnormal (42) | 55.9±14.0 | 66.6±13.1 | 60.7±17.4 | 63.6±16.3 | 67.0±15.1 | |

* Others included remarried, co-habiting, separated, divorced, and widowed. ENV: Environmental health domain. GEN: General facet. PHY: Physical health domain. PSY: Psychological health domain. SOC: Social relationship domain. There were no missing data, except for 91 and 108 participants who did not report alcohol and tobacco use, respectively.

The age- and sex-adjusted mean scores of the WHOQOL-BREF subscale domains were 61.5 for physical health, 73.5 for psychological health, 70.1 for social relationship, 67.2 for environmental health, and 70.6 for the general facet. There were no differences in the WHOQOL-BREF scores between sex, age group, education, income, alcohol use, tobacco use, and BMI ranges among the participants. Never-married participants had lower scores than those with different marital status in the psychological health domain (p = 0.022). Unemployed and pensioned participants had lower scores than the other participants in the general facet (p = 0.020). Participants living in apartments had lower scores than the other participants in the physical health domain and general facet (p = 0.039 and p = 0.003, respectively). Interestingly, subgroup analyses suggested that participants living in gers or houses without central utilities differ in the quality of life between residency locations only (rural vs. urban areas), whereas participants living in apartments with central utilities differed between age groups, sex, education, and employment (S2 Table). Participants living in Ulaanbaatar had lower scores in the physical health domain than those living in rural areas (p < 0.001). Furthermore, subgroup analyses suggested that participants living in Ulaanbaatar did not differ in the quality of life between sociodemographic characteristics (ger vs. apartment), whereas participants living in rural areas differed between age groups, marital status, and income (S3 Table). Participants with abnormal or borderline anxiety or depression had lower scores than those without anxiety or depression in all domains and general facet (all p < 0.001). Among the male participants, the scores of psychological health and social relationship domains peaked in the middle age (30–44 years) and then dropped (p = 0.007 and p = 0.001, respectively). Among female participants, the social relationship decreased as age increased (p = 0.040).

The prevalence of poor QOL for each domain had the following cut-off points using 1 SD below the mean criterion: 49 for physical health, 61 for psychological health, 54 for social relationship, and 54 for environmental health (Table 3). We found that 13.9–20.0% of the participants had a poor QOL (15.0–22.9% for men and 12.8–17.3% for women). There was no difference in the prevalence of poor QOL between the sexes. In contrast, the prevalence of poor QOL in psychological health differed between age groups. Younger participants had poorer psychological health than older participants.

Table 3. Prevalence of poor QOL by sex and age group.

| Characteristics | WHOQOL-BREF domains | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHY | PSY | SOC | ENV | ||||||

| Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | Count | % | ||

| Cut-off scores using the 1 SD below the mean criterion (PHY 49; PSY 61; SOC 54; ENV 54) | |||||||||

| Male | 18–29 | 11 | 26.8 | 14 | 38.9 | 35 | 16.6 | 17 | 34.5 |

| 30–44 | 9 | 22.0 | 7 | 19.4 | 72 | 34.1 | 11 | 25.5 | |

| 45–65 | 21 | 51.2 | 15 | 41.7 | 104 | 49.3 | 22 | 40.0 | |

| Total | 41 | 15.7 | 36 | 13.8 | 50 | 19.2 | 55 | 21.1 | |

| Age-adjusted %, (CI) | 15.7 (15.7–15.7) | 15.0 (15.0–15.0) | 20.3 (20.3–20.4) | 22.9 (22.9–22.9) | |||||

| p value | 0.255 | 0.007 | 0.016 | 0.009 | |||||

| Female | 18–29 | 18 | 28.6 | 20 | 34.5 | 17 | 22.1 | 22 | 28.2 |

| 30–44 | 23 | 36.5 | 21 | 36.2 | 33 | 42.8 | 32 | 41.0 | |

| 45–65 | 22 | 34.9 | 17 | 29.3 | 27 | 35.1 | 24 | 30.8 | |

| Total | 63 | 13.9 | 58 | 12.8 | 77 | 17.0 | 78 | 17.2 | |

| Age-adjusted %, (CI) | 13.9 (13.9–13.9) | 12.8 (12.8–12.8) | 17.1 (17.1–17.2) | 17.3 (17.3–17.3) | |||||

| p value | 0.999 | 0.477 | 0.303 | 0.590 | |||||

| Total | 18–29 | 29 | 27.9 | 34 | 36.2 | 34 | 26.8 | 41 | 30.8 |

| 30–44 | 32 | 30.8 | 28 | 29.8 | 44 | 34.6 | 46 | 34.6 | |

| ≥ 45 | 43 | 41.3 | 32 | 34.0 | 49 | 38.6 | 46 | 34.6 | |

| Total | 104 | 14.6 | 94 | 13.2 | 127 | 17.8 | 133 | 18.6 | |

| Age-adjusted %, (CI) | 14.8 (14.7–14.8) | 13.9 (13.8–13.9) | 18.7 (18.6–18.7) | 20.0 (19.9–20.1) | |||||

| p value | 0.631 | 0.035 | 0.908 | 0.212 | |||||

* p values were analyzed using the χ2 test. CI: Confidence interval. ENV: Environmental health domain. PHY: Physical health domain. PSY: Psychological health domain. QOL: Quality of life. SOC: Social relationship domain. The cut-off points were 49 for PHY, 61 for PSY, 54 for SOC, and 54 for ENV.

Table 4 shows the Spearman’s correlation coefficients between the WHOQOL-BREF scores and selected continuous variables. All domains of the WHOQOL-BREF showed a significant inverse correlation with anxiety and depression (p < 0.001), and the coefficients ranged from -0.353 to -0.206 and from -0.335 to -0.156, respectively.

Table 4. Spearman correlation coefficients between the WHOQOL-BREF subscale scores and selected factors.

| Variables | WHOQOL-BREF domains | Perception | |||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| PHY | PSY | SOC | ENV | GEN | |

| Age | 0.020 | 0.000 | -0.062 | 0.030 | -0.013 |

| Body temperature | 0.111* | 0.008 | 0.033 | 0.033 | -0.008 |

| Heart rate (per minute) |

-0.071 | 0.006 | 0.019 | -0.012 | -0.036 |

| Arterial systolic pressure | -0.022 | 0.091* | 0.021 | 0.026 | 0.002 |

| Arterial diastolic pressure | -0.026 | 0.070 | 0.003 | 0.037 | 0.013 |

| Arterial oxygen saturation | 0.007 | -0.020 | -0.008 | -0.039 | -0.057 |

| BMI | -0.006 | 0.014 | -0.022 | 0.001 | 0.002 |

| Anxiety score | -0.319*** | -0.353*** | -0.206*** | -0.256*** | -0.223** |

| Depression score | -0.321*** | -0.335*** | -0.249*** | -0.257*** | -0.156** |

* p < 0.05

** p < 0.01

*** p < 0.001. ENV: Environmental health domain. GEN: General facet. PHY: Physical health domain. PSY: Psychological health domain. SOC: Social relationship domain.

Table 5 shows the coefficients of multiple linear regression for each domain of the WHOQOL-BREF. To investigate how QOL was predicted by the sociodemographic characteristics, independent variables were selected for each domain, using a stepwise method. This demonstrates that the physical health domain was predicted by residency location, anxiety, and depression (R2 = 0.200, p < 0.001); psychological health domain by anxiety and depression (R2 = 0.203, p < 0.001); social relatuonship domain by anxiety and depression (R2 = 0.116, p < 0.001); and environmental health domain by sex, waist circumstance, anxiety, and depression (R2 = 0.117, p < 0.001), respectively. The general facet was predicted by age group, residency location, and anxiety (R2 = 0.087, p < 0.001). No multicollinearity was detected between the tested variables; the independence assumption was satisfied; the distribution of the residuals satisfied the normality assumptions. The variance of the model was constant, and homoscedasticity was not violated.

Table 5. Multiple linear regression analyses on the WHOQOL-BREF domain scores by demographic characteristics, vital signs, and psychological symptoms.

| Variables | B | Beta | t | p value* | 95% Confidence Interval for Exp (B) |

Collinearity Statistics | ||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Lower | Upper | Tolerance | Variance InflationFactor | |||||

| Physical health domain (R2 = 0.200, Durbin-Watson = 2.083, F18 = 8.28, p < 0.001) | ||||||||

| Constant | 4.24 | 0.73 | 0.940 | -110.20 | 118.67 | |||

| Residency location (ref: Ulaanbaatar) | -1.86 | -0.22 | -5.25 | < 0.001 | -2.55 | -1.16 | 0.77 | 1.30 |

| Anxiety score | -0.82 | -0.21 | -4.85 | < 0.001 | -1.16 | -0.49 | 0.72 | 1.38 |

| Depression score | -0.90 | -0.20 | -4.71 | < 0.001 | -1.28 | -0.53 | 0.74 | 1.36 |

| Psychological health domain (R2 = 0.203, Durbin-Watson = 1.963, F18 = 8.448, p < 0.001) | ||||||||

| Constant | 106.0 | 1.89 | 0.060 | -4.31 | 216.31 | |||

| Anxiety score | -1.09 | -0.28 | -6.64 | < 0.001 | -1.41 | -0.77 | 0.72 | 1.38 |

| Depression score | -0.90 | -0.21 | -4.88 | < 0.001 | -1.27 | -0.54 | 0.74 | 1.36 |

| Social relationship domain (R2 = 0.116, Durbin-Watson = 1.911, F18 = 4.353, p < 0.001) | ||||||||

| Constant | 74.40 | 0.96 | 0.340 | -77.10 | 225.9 | |||

| Age group (ref: 45–65) | -1.89 | -0.10 | -2.01 | 0.045 | -3.75 | -0.04 | 0.67 | 1.50 |

| Residency location (ref: Ulaanbaatar) | -1.10 | -0.10 | -2.35 | 0.019 | -2.02 | -0.18 | 0.77 | 1.30 |

| Anxiety score | -0.65 | -0.13 | -2.89 | 0.004 | -1.09 | -0.21 | 0.72 | 1.38 |

| Depression score | -1.17 | -0.21 | -4.59 | < 0.001 | -1.67 | -0.67 | 0.74 | 1.36 |

| Environmental health domain (R2 = 0.117, Durbin-Watson = 2.000, F18 = 4.393, p < 0.001) | ||||||||

| Constant | 26.38 | 0.41 | 0.682 | -100.21 | 152.97 | |||

| Employment (ref: employed) | 1.25 | 0.10 | 2.20 | 0.027 | 0.04 | 2.36 | 0.70 | 1.42 |

| Anxiety score | -0.87 | -0.21 | -4.60 | < 0.001 | -1.23 | -0.50 | 0.72 | 1.38 |

| Depression score | -0.67 | -0.14 | -3.10 | 0.002 | -1.08 | -0.25 | 0.74 | 1.36 |

| General facet (R2 = 0.087, Durbin-Watson = 1.993, F18 = 3.142, p < 0.001) | ||||||||

| Constant | 118.55 | 1.59 | 0.113 | -28.22 | 265.31 | |||

| Age group (ref: 45–65) | -2.01 | -0.11 | -2.20 | 0.028 | -3.81 | -0.22 | 0.67 | 1.50 |

| Residency location (ref: Ulaanbaatar) | -0.98 | -0.10 | -2.16 | 0.031 | -1.87 | -0.09 | 0.77 | 1.30 |

| Anxiety score | -0.98 | -0.21 | -4.51 | < 0.001 | -1.41 | -0.56 | 0.72 | 1.38 |

* p values were tested using the multiple linear regression. Factors: (constant), sex, age group, marital status, education, employment, income, living condition, residency location, alcohol and tobacco use, body temperature, heart rate, systolic blood pressure, diastolic blood pressure, arterial oxygen saturation, body mass index, anxiety and depression score. ref: A reference group for categorical variables.

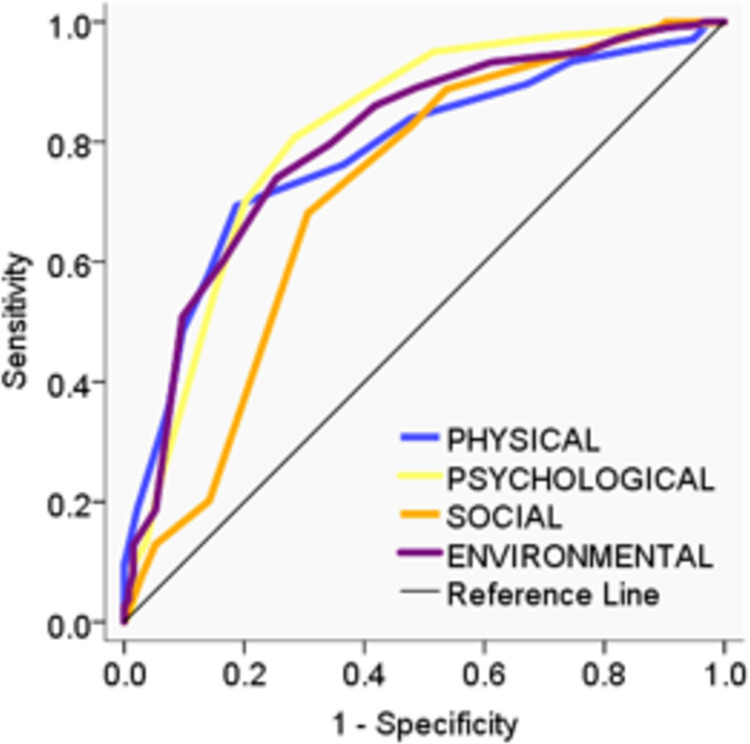

As described in the Methods section, we demonstrated the true-positive rates of each domain against the false-positive rate at a variety of thresholds for a single variable created by dichotomizing the general facet at 1 SD below the mean score (Fig 2).

Fig 2. ROC curve of the WHOQOL-BREF domains.

AUC values were 0.78, 0.81, 0.71, and 0.80 for the physical health, psychological health, social relationship, and environmental health domains, respectively.

The area under the ROC curve (AUC) indicates performance; the greater the AUC, the better the performance. Four cut-off points were set to calculated sensitivity, specificity, positive predictive value, negative predictive value, and Youden’s index for each domain (S4 Table); 1 SD below the mean, 95% of sensitivity, 95% of specificity, and the highest of Youden’s index. Youden’s index was the highest for psychological health domain (0.52) and the lowest for social relationship domain (0.38).

Discussion

This is the first report on the normative data on QOL in the general population of Mongolia using the WHOQOL-BREF. The WHOQOL-BREF is a frequently used self-report questionnaire for QOL which has more merits than shortcomings [16]. In our previous study, we validated the Mongolian version of the WHOQOL-BREF, which showed good validity and reliability for assessing QOL [8]. However, we assessed the questionnaire’s psychometric properties only in the general urban population. The present study investigated the differences in QOL between urban and rural residents. The sample population was chosen to represent the target population, considering sociodemographic characteristics. The level of internal consistency was acceptable to good. Therefore, the current results provide valuable information on QOL in the general population of Mongolia.

The present findings suggest that the Mongolian adults in this sample had a specific QOL pattern in terms of domain characteristics of WHOQOL-BREF. As shown in Table 6, the physical health domain score was lower, whereas the psychological health, social relationship, and environmental health domain scores were higher or similar compared with those of other countries [12,16–20]. Furthermore, the psychological health was relatively higher compared to other countries except Norway.

Table 6. WHOQOL-BREF domain scores by different countries.

| Countries | n | PHY | PSY | SOC | ENV |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Mongolia (this study) a | 714 | 13.8±2.0 | 15.8±1.9 | 15.3±2.5 | 14.8±2.1 |

| Mongolia (this study) b | 61.5±12.6 | 73.6±12.1 | 70.4±15.9 | 67.6±13.4 | |

| Norway (Kafloss et al. 2021) [17]a | 615–626 | 16.5±2.6 | 15.9±2.2 | 15.4±2.6 | 15.3±2.2 |

| Pakistan (Lodhi et al. 2019) [12] b | 2063 | 65.2±15.2 | 67.4±15.0 | 72.0±16.5 | 55.5±15.0 |

| China (Xia et al. 2012) [18] a | 1052 | 14.6±2.0 | 13.7±2.2 | 14.1±2.2 | 12.3±2.3 |

| China (Xia et al. 2012) [18] b | 66.0±12.6 | 60.6±14.0 | 63.2±13.9 | 52.0±14.5 | |

| Iran (Nedjat et al. 2008) [19] a | 906 | 14.7±2.3 | 13.7±2.5 | 14.1±2.4 | 12.7±2.4 |

| Taiwan (Wang et al. 2006) [20] b | 13083 | 59.1±13.7 | 49.4±15.6 | 56.5±14.3 | 42.4±14.9 |

| Global (Skevington et al. 2002: 23 countries) [16] a | 11830 | 16.2±2.9 | 15.0±2.1 | 14.3±3.2 | 13.5±2.6 |

a scale in the range 4–20. b scale in the range 1–100. ENV: Environmental health domain; PHY: Physical health domain; PSY: Psychological health domain; SOC: Social relationship domain. n: Number.

By the estimated prevalence rates of good/poor QOL, the Mongolian adults showed a relatively higher proportion of poor QOL (ranging from 13 to 19%) compared with Chinese adults (ranging from 7 to 16%) [18]. These findings might be reasonable because the life expectancy of the Mongolians is still low compared with that of developed countries. In addition, we found that living in an apartment in an urban area had a negative influence on physical health. It might be associated with the recent rapid urbanization that can cause decreased physical activity, implicating obesity. Psychological problems, including anxiety and depression, had a strong negative impact on each domain of the WHOQOL-BREF. A high rate of unemployment, low income, increased alcohol consumption, and living in urban areas were associated with the underlying high rate of anxiety and depression. These findings also support our previous studies that measured mental distress and sleep quality in the general population [21,22]. Employment was directly related to an increased QOL. Sex did not affect the QOL, and there was a tendency for male participants to have lower environmental QOL than female participants. Unlike the other Asian cultures, Mongolia does not share male dominance in society. Age was an important factor for social QOL, which declined in older participants. Living in urban areas has harmed the physical and social domain. Because Ulaanbaatar is the coldest capital and one of the most air-polluted cities in the world, many health issues have been addressed. Moreover, the intentional homicide rate in Mongolia was among the highest in Asian countries in the last few decades after Iraq [23]. In clinical implication, the findings of this nationwide population-based study seem to provide comprehensive information for evidence-based policy and service quality assessment for health care.

The main limitations of this study are as follows: (i) as a self-report questionnaire, WHOQOL-BREF is based on subjective answers; (ii) although this study investigated the QOL in the adult population using WHOQOL-BREF, future studies should include more tools such as EQ-5D and SF-36 to determine criterion validity. Despite these limitations, we believe this is the first study to provide normative data for the WHOQOL-BREF in Mongolia, enabling further studies to use the results as baseline data and compare them with international findings.

Conclusion

This is the first report on normative data on the QOL in the general population of Mongolia. Physical health was low compared with that of international data. Poor QOL was observed among those living in urban areas with mental health issues.

Supporting information

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Acknowledgments

The authors acknowledge the assistance of the Timeline cohort study team of the Brain Science Institute at the Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences. We greatly appreciate those who participated in our study and 48 sampling center coordinators who supported for collecting data.

Data Availability

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.

Funding Statement

The corresponding author, Battuvshin Lkhagvasuren, received a research grant, 200305, from the Mongolian National University of Medical Sciences for this study.

References

- 1.National Statistical Office of Mongolia, 2019 Population and Housing By-Census of Mongolia 2020. Available from: https://en.nso.mn/.

- 2.Plueckhahn R, Bayartsetseg T. Negotiation, social indebtedness, and the making of urban economies in Ulaanbaatar. Central Asian Survey. 2018;37(3):438–56. doi: 10.1080/02634937.2018.1442318 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Pillarisetti A, Ma R, Buyan M, Nanzad B, Argo Y, Yang X, et al. Advanced household heat pumps for air pollution control: A pilot field study in Ulaanbaatar, the coldest capital city in the world. Environmental research. 2019;176:108381. Epub 2019/07/22. doi: 10.1016/j.envres.2019.03.019 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lim M, Myagmarchuluun S, Ban H, Hwang Y, Ochir C, Lodoisamba D, et al. Characteristics of Indoor PM2.5 Concentration in Gers Using Coal Stoves in Ulaanbaatar, Mongolia. International journal of environmental research and public health. 2018;15(11). doi: 10.3390/ijerph15112524 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6267369. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Access GBDH, Quality Collaborators. cue Electronic address, GBDH Access, Quality C. Healthcare Access and Quality Index based on mortality from causes amenable to personal health care in 195 countries and territories, 1990–2015: a novel analysis from the Global Burden of Disease Study 2015. Lancet. 2017;390(10091):231–66. doi: 10.1016/S0140-6736(17)30818-8 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC5528124. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Bollyky TJ, Templin T, Cohen M, Dieleman JL. Lower-Income Countries That Face The Most Rapid Shift In Noncommunicable Disease Burden Are Also The Least Prepared. Health affairs. 2017;36(11):1866–75. doi: 10.1377/hlthaff.2017.0708 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7705176. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.WHOQOL-BREF: introduction, administration, scoring and generic version of the assessment: field trial version, December 1996. World Health Organization. [Internet]. WHO, at https://apps.who.int/iris/handle/10665/63529. 1996.

- 8.Bat-Erdene E, Tumurbaatar E, Tumur-Ochir E, Jamiyandorj O, Jadamba T, Yamamoto E, et al. Validation of the abbreviated version of the World Health Organization Quality of Life in Mongolia: A population-based cross-sectional study among adults in Ulaanbaatar. Nagoya Journal of Medical Science. 2023;85(1): 79–92. doi: 10.18999/nagjms.85.1.79 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC10009621. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.World Health Organization, WHO Technical specifications for automated non-invasive blood pressure measuring devices with cuff 2020. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789240002654. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed]

- 10.World Health Organization, WHO-UNICEF Technical specifications and guidance for oxygen therapy devices 2019. Available from: https://www.who.int/publications/i/item/9789241516914.

- 11.Development of the World Health Organization WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment. The WHOQOL Group. Psychological medicine. 1998;28(3):551–8. doi: 10.1017/s0033291798006667. PubMed PMID: 9626712. [DOI] [PubMed]

- 12.Lodhi FS, Montazeri A, Nedjat S, Mahmoodi M, Farooq U, Yaseri M, et al. Assessing the quality of life among Pakistani general population and their associated factors by using the World Health Organization’s quality of life instrument (WHOQOL-BREF): a population based cross-sectional study. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2019;17(1):9. doi: 10.1186/s12955-018-1065-x ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC6332637. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 13.Zigmond AS, Snaith RP. The hospital anxiety and depression scale. Acta psychiatrica Scandinavica. 1983;67(6):361–70. doi: 10.1111/j.1600-0447.1983.tb09716.x [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Tumurbaatar E, Hiramoto T, Tumur-Ochir G, Jargalsaikhan O, Erkhembayar R, Jadamba T, et al. Translation, reliability, and structural validity of the Hospital Anxiety and Depression Scale (HADS) in the general population of Mongolia. Neuroscience Research Notes. 2021;4(3Suppl):30–9. doi: 10.31117/neuroscirn.v4i3Suppl.101 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Al-Fayez GA, Ohaeri JU. Profile of subjective quality of life and its correlates in a nation-wide sample of high school students in an Arab setting using the WHOQOL-Bref. BMC psychiatry. 2011;11:71. doi: 10.1186/1471-244X-11-71 PubMed PMID: 21518447; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3098152. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 16.Skevington SM, Lotfy M, O’Connell KA, Group W. The World Health Organization’s WHOQOL-BREF quality of life assessment: psychometric properties and results of the international field trial. A report from the WHOQOL group. Quality of life research: an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2004;13(2):299–310. doi: 10.1023/B:QURE.0000018486.91360.00 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Kalfoss MH, Reidunsdatter RJ, Klockner CA, Nilsen M. Validation of the WHOQOL-Bref: psychometric properties and normative data for the Norwegian general population. Health and quality of life outcomes. 2021;19(1):13. doi: 10.1186/s12955-020-01656-x ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC7792093. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Xia P, Li N, Hau KT, Liu C, Lu Y. Quality of life of Chinese urban community residents: a psychometric study of the mainland Chinese version of the WHOQOL-BREF. BMC medical research methodology. 2012;12:37. doi: 10.1186/1471-2288-12-37 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC3364902. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Nedjat S, Montazeri A, Holakouie K, Mohammad K, Majdzadeh R. Psychometric properties of the Iranian interview-administered version of the World Health Organization’s Quality of Life Questionnaire (WHOQOL-BREF): a population-based study. BMC health services research. 2008;8:61. doi: 10.1186/1472-6963-8-61 PubMed PMID: 18366715; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC2287168. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.Wang WC, Yao G, Tsai YJ, Wang JD, Hsieh CL. Validating, improving reliability, and estimating correlation of the four subscales in the WHOQOL-BREF using multidimensional Rasch analysis. Quality of life research: an international journal of quality of life aspects of treatment, care and rehabilitation. 2006;15(4):607–20. doi: 10.1007/s11136-005-4365-7 . [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 21.Lkhagvasuren B, Hiramoto T, Tumurbaatar E, Bat-Erdene E, Tumur-Ochir G, Viswanath V, et al. The Brain Overwork Scale: A Population-Based Cross-Sectional Study on the Psychometric Properties of a New 10-Item Scale to Assess Mental Distress in Mongolia. Healthcare (Basel, Switzerland). 2023;11(7). Epub 2023/04/14. doi: 10.3390/healthcare11071003 ; PubMed Central PMCID: PMC10094685. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Tumurbaatar E, Hiramoto T, Tumur-Ochir G, Bat-Erdene E, Erdenebaatar C, Amartuvshin T, et al. Psychometric properties of the Mongolian version of the Pittsburgh Sleep Quality Index. Neuroscience Research Notes. 2023;6(3):190.1-.8. doi: 10.31117/neuroscirn.v6i3.190 [DOI] [Google Scholar]

- 23.World Development Indicators: Intentional homicides [Internet]. 2012. Available from: https://databank.worldbank.org/reports.aspx?source=2&series=VC.IHR.PSRC.P5&country=#advancedDownloadOptions.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

(DOCX)

Data Availability Statement

All relevant data are within the paper and its Supporting Information files.