Abstract

Critics of stop and frisk have heralded its recent demise in several large U.S. cities. Proponents of stop and frisk respond that when the practice ends, crime increases. Both groups typically assume that the end of stop and frisk reduces the number of police-civilian interactions. We find otherwise in Chicago: The decline in pedestrian stops coincided with an increase in traffic stops. Qualitative evidence suggests that the Chicago Police deliberately switched from pedestrian to traffic stops. Quantitative data are consistent with this hypothesis: As stop and frisk ended, Chicago Police traffic stops diverged (in quantity and composition) from those of another enforcement agency in Chicago, and the new traffic stops affected the same types of Chicagoans who were previously subject to pedestrian stops.

When Chicago police stopped stopping pedestrians, they started pulling over more drivers.

INTRODUCTION

The end of stop and frisk is one of the most celebrated developments in U.S. policing. In New York City, pedestrian stops fell by 97% between 2011 and 2015, from nearly 700,000 (eight stops per 100 New Yorkers per year) to under 25,000 (1, 2). A seemingly similar sea change occurred in Chicago in late 2015. In a span of months, pedestrian stops plummeted 85%, from more than 500,000 (20 stops per 100 Chicagoans per year) to fewer than 100,000 (3). Critics of stop and frisk applauded this shift as a victory for civil liberties (4), while others argued that it caused a crime wave (5). Both interpretations rest on the assumption that, as Devi and Fryer (5) put it, “the number of police-civilian interactions decreased by almost 90%” in Chicago. We find instead that the Chicago Police switched from pedestrian to traffic stops. Traffic stops climbed from 85,000 to nearly 600,000 between 2016 and 2019. Four years after the end of stop and frisk, the number of police-civilian interactions remained nearly unchanged.

As one commenter put it on Second City Cop, a blog that served as the “online water cooler for Chicago’s police officers” (6), “that’s when the bosses switched to making their new stat the ‘blue cards’ [traffic stop cards]. They yelled every single day ‘more blue cards’ and they still do. Just like the old contact cards [for pedestrian stops] the blue cards are now the stat for bosses hoping to get promoted even higher.” Quantitative evidence is consistent with the idea of substitution from pedestrian stops to traffic stops. The traffic-stop rate increased most in police beats where pedestrian-stop rates fell the most. The new traffic stops were much less likely to yield citations and much more likely to involve Black drivers. Comparing trends in Chicago Police traffic stops to those of another enforcement agency operating in Cook County—the Illinois State Police, which was not subject to the same pedestrian-stop reforms—we observe a large divergence when stop and frisk ended. Before the end of 2015, the two agencies followed parallel trends in the number of traffic stops, the citation rate, and the racial composition of stopped drivers. After the end of 2015, as traffic stops increased (especially for Black drivers) and the traffic-stop citation rate decreased for the Chicago Police, these quantities remained unchanged for the Illinois State Police in Cook County. These findings suggest that the Chicago Police substituted traffic stops for pedestrian stops.

The welfare consequences of this substitution are ambiguous. Evaluating welfare consequences would require analysis that we do not pursue, including but not limited to (i) estimating the effect of pedestrian and traffic stops on crime [see chapter 7 of (3); (5, 7, 8)] and on traffic safety (9); (ii) estimating the proportion of pedestrian and traffic stops that violate civil liberties {on stop and frisk and civil liberties in Chicago specifically, see [chapter 4 of (3)]; on consequences of violations, see (10, 11)}, and (iii) placing welfare weights on crime, traffic safety, and civil liberties. Welfare analysis along these lines would inform not only our understanding of the Chicago case but also of ongoing policy changes elsewhere. We provide a foundation for such work by documenting the nature and extent of the substitution of traffic stops for pedestrian stops in Chicago.

Context

The end of stop and frisk in New York in 2014 increased scrutiny of pedestrian-stop practices in other major U.S. cities. We use the term “stop and frisk” in our title and introduction for reader familiarity; this is the term commonly used in the press and in the literature [e.g., (3)]. Of course, many, perhaps the majority, of pedestrian stops in Chicago did not involve searches or frisks [page 130 of (3)]. In the remainder of the paper, we use the term “pedestrian stops.”

In the spring of 2015, the American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU) released a report on pedestrian stops in Chicago, documenting large disparities in stop rates by race and exceptionally high stop rates overall: The level of pedestrian stops was nearly three times as high in Chicago as it had been in prereform New York. See chapter 3 of (3) on the emergence of stop and frisk as an organizational strategy for the Chicago Police.

On 7 August 2015, the ACLU and the Chicago Police announced an agreement introducing extensive new documentation requirements for pedestrian stops and allowing the ACLU to review the documents. The agreement took effect on 1 January 2016. In the intervening months, two other events heightened scrutiny of the Chicago Police. The first was the court-ordered release of video of the murder of Laquan McDonald, who was shot 16 times as he walked away from police (12). The second was the initiation, in December 2015, of a Department of Justice (DOJ) pattern-and-practice investigation, partly in response to the release of the video.

RESULTS

In August of 2015, Chicago police made more than 45,000 pedestrian stops. Just 5 months later, in January 2016, they made fewer than 8000. With Chicago’s (city) population of approximately 2.7 million, this change meant that the annualized stop rate dropped from more than 20 per 100 Chicagoans per year to less than four per 100 Chicagoans per year (Fig. 1) (3, 13).

Fig. 1. The substitution of traffic stops for pedestrian stops.

The shaded region marks the period between the announcement (in August 2015) and implementation (January 2016) of an ACLU agreement requiring extensive new documentation for pedestrian stops. In the intervening months, the release of a video of a police shooting (November) and the announcement of a DOJ investigation (December) also heightened scrutiny of the Chicago Police. Sources: Traffic-stop data from the Illinois Department of Transportation (19). For 2015 and earlier, pedestrian-stop data from the Chicago Police Department’s contact card dataset; for 2016 and later, pedestrian-stop data from the Investigatory Stop Report dataset.

Observers suggested that the decline in pedestrian stops was a response to heightened scrutiny of the Chicago Police (14), including the new documentation for pedestrian stops, which replaced the 3 × 5 contact card with a two-page form. “Holy crap – 9 by 11 huge, easily double the amount of information wanted and … what’s that? Oh, that’s only side one?” wrote one commenter on the blog Second City Cop, “Little wonder that activity has dropped off by extraordinary amounts.”

The drop in pedestrian stops coincided with a sharp increase in traffic stops (Fig. 1). Over the following 4 years (2016–2019), the number of traffic stops rose sevenfold, from an annualized rate of 3.2 per 100 per year to 22 per 100 per year in 2019—approximately the rate of pedestrian stops in 2015. We use traffic-stop data from the Traffic Stop Statistical Study, which records a subset of all stops (it excludes stops of minors, for example; see the Supplementary Materials for details.) The increase in traffic stops occurred in spurts each January, a pattern that was likely influenced by the resetting of year-to-date statistics that were reviewed in accountability meetings, creating incentives to get ahead of last winter’s performance (according to an interview with former Deputy Chief Daniel Godsel). The salience of year-to-date activity figures in accountability meetings may also explain why the composition of traffic stops began to change in late 2015—after the announcement of the ACLU agreement, the Laquan McDonald video release, and the initiation of the DOJ investigation, but before the ACLU agreement took effect on 1 January 2016—while the quantity of traffic stops only began to rise in the new year. It is possible that officers began to focus on Black drivers in the wake of the Laquan McDonald video and/or in response to the announcement of the DOJ investigation (we thank an anonymous reviewer for suggesting this); only in January of 2016 did meetings spotlighting year-to-date activity numbers prompt a call for more traffic stops.

Yet, Fig. 1 makes clear that, while January jumps in traffic stops have occurred since 2011, something changed in 2016. Before 2016, these jumps were followed by gradual February–December declines, leaving the level of traffic stops unchanged. Beginning in 2016, in contrast, traffic stops did not much decline after large increases each January. The result was a fivefold rise in traffic stops. Why?

The ACLU and other observers suggested that this increase in traffic stops was a response to the decline in pedestrian stops [e.g., (15, 16)]. Comments on the law enforcement blog Second City Cop point in the same direction. “Many of us knew immediately that the blue card replaced the old contact card, once po’s stopped writing isr’s [Investigatory Stop Reports, the new documentation for pedestrian stops],” wrote one commenter. Another wrote: "These dope bosses turned the contact card [for pedestrian stops] into a stat and demanded them just for self-promotion. Totally destroying what the card was supposed to be used for, an investigative tool. I’m sure by killing the contact card it also affected the Dets investigations too. They used them to put the pieces together solving crimes. But now the bosses made the blue cards “TSSS” cards [traffic stop statistical study] their new contact card. They run missions for them, ask for them, etc. It’s the new contact card and I’m sure once some group sees the massive increase in TSSS cards that correlates to the same time ISRs [new documentation for pedestrian stops] started, red flags will fly. It’s a no brainer."

We report additional comments along these lines in the Supplementary Materials. Quantitative data are consistent with the hypothesis of substitution. Traffic-stop rates increased most in police beats where pedestrian-stop rates fell the most. One simple way to way to see this is to note the strong correlation (ρ = −0.71) across beats between the 2015-to-2016 increase in traffic stops and the 2015-to-2016 decrease in pedestrian stops (right, Fig. 2). The relationship does not arise because of a preexisting negative correlation between changes in traffic-stop rates and changes in pedestrian-stop rates: The correlation is much weaker and runs in the opposite direction (ρ = 0.13) for 2014-to-2015 changes (left, Fig. 2). In other words, between 2014 and 2015, traffic stops and pedestrian stops tended (weakly) to increase in the same beats, whereas from 2015 to 2016, traffic stops grew much more in the beats where pedestrian stops fell. (Both panels of Fig. 2 calculate changes using the first 6 months of each year: The first 6 months of 2016 minus the first 6 months of 2015; we use the first 6 months because heightened scrutiny of pedestrian stops begins in August 2015.)

Fig. 2. New traffic stops occurred where pedestrian stops disappeared.

Across Chicago’s police beats, the increase in the traffic-stop rate between 2015 and 2016 was highly correlated with the decrease in the pedestrian-stop rate during that same period. In other words, traffic stops increased where pedestrian stops disappeared. This correlation is consistent with the idea that traffic stops were seen as a substitute for pedestrian stops. That we observe no such correlation between 2014 and 2015 further suggests that the 2015–2016 correlation reflects substitution, rather than a continuation of preexisting trends. Sources: Traffic-stop data from the Illinois Department of Transportation (19). Pedestrian-stop data from the Chicago Police Department’s contact card dataset for 2015 and earlier and Investigatory Stop Report dataset for 2016 and later (20). Beat population data come from (21). Note: We exclude one outlier from the right panel for visual clarity. That outlier is included in the correlation calculation.

The quantitative record is hard to reconcile with alternative explanations. One such alternative is that traffic stops increased because driver behavior changed. Indeed, (7) do find that citizen behavior, in particular, the propensity to commit crimes, changes in the wake of police scandals, such as the release of footage of the Laquan McDonald shooting. If Chicago drivers began committing more violations in early 2016, the increase in traffic stops might have reflected a change in driver rather than police behavior.

We address this possibility by comparing Chicago Police Department traffic stops to traffic stops conducted by another agency operating in Cook County: the Illinois State Police. These two agencies share many roadway responsibilities. Both are responsible for enforcing the state laws that define moving violations (like speeding), for example, and the state laws that define equipment violations (like broken tail lights). Their jurisdictions are not identical; for example, only the Chicago Police enforce city ordinances (such as parking rules). In addition, the geographic identifiers in the Traffic Stop Statistical Study data do not allow us to distinguish Illinois State Police stops within the City of Chicago from Illinois State Police Stops elsewhere in Cook County (during this period, Chicago contained just over half of the Cook County population); we therefore think of the two agencies as policing similar but not identical driver populations. Still, if the increase in Chicago Police traffic stops were driven by a change in driver behavior, we would expect the number of Illinois State Police traffic stops in Cook County to increase, too.

Instead, we find that the Illinois State Police did not ramp up traffic stops in Cook County after 2015. Before 2016, trends in traffic-stop rates for the Illinois State Police (in Cook County) and the Chicago Police were parallel. In 2016, in contrast, the Chicago Police traffic-stop rate nearly doubled, to almost seven stops per 100 residents per year, while the Illinois State Police traffic-stop rate remained just under one per 100 residents (Fig. 1). By 2019, the gap had widened further, as the Chicago Police traffic-stop rate reached almost 22 per 100 residents and the rate for Illinois State Police remained unchanged. This difference in differences in traffic-stop rates (comparing the Chicago Police to the Illinois State Police in Cook County, before and after 1 January 2016) is substantively large (11 stops per 100 residents per year) and statistically different from zero (robust SE, 0.89). Specifically, we estimate StopRateit = αi + γt + βTreatit + εit, where i indexes the two agencies, t indexes months, and Treatit takes a value of 1 for Chicago Police beginning in January, 2016.

One concern about our comparison between these two agencies might be that the behavior of the Chicago Police could itself affect the behavior of the Illinois State Police in the Chicago area: Perhaps the Illinois State Police would have begun making more stops within Chicago, were it not for the heightened stop activity of the Chicago Police. A second concern might be that, even within city limits, the Illinois State Police might focus traffic enforcement on different types of roadways, where driver behavior could respond to different time-varying shocks. To partially address both of these concerns, we repeat our difference-in-differences analysis with a different comparison group: police in other cities in the Chicago area. Specifically, we consider police in every city in Illinois in the census-defined Chicago-Naperville Combined Statistical Area that has a population of at least 50,000. The results are similar: As the Chicago Police doubled and then eventually septupled their traffic-stop rate, traffic-stop rates in the near suburbs remained unchanged (fig. S3).

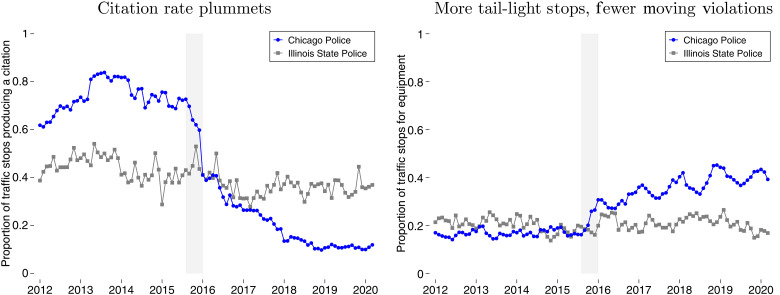

Another alternative explanation might be that the drop in pedestrian stops happened to coincide with unrelated efforts to increase traffic safety. As a result of the Laquan McDonald scandal, the mayor of Chicago fired Chicago Police superintendent Garry McCarthy in December 2015. New leadership often brings fresh priorities. However, a new emphasis on traffic safety would be unlikely to produce a sharp decline in the proportion of traffic stops producing a citation, which we document in Fig. 3 (if anything, the citation rate might have gone up), nor would we expect a focus on traffic safety to cause a jump in the percentage of stops involving equipment violations, such as dangling air fresheners or broken tail or license place lights (right, Fig. 3). Rather, both the falling citation rate and rising equipment violation rate are consistent with the idea that the new traffic stops were proactive, intended to replace pedestrian stops as a tool of proactive policing. Again, in each case, the difference in differences (comparing the Chicago Police to the state police in Cook County, before and after 1 January 2016) is substantively large (45 percentage points for the citation rate and 18 percentage points for the equipment violation rate) and precisely estimated (robust SE, 1.8 and 1.1, respectively). The same differences in differences arise when we compare the Chicago Police to police agencies in the Chicago suburbs (fig. S4).

Fig. 3. Strategic substitution or traffic safety campaign?

The proportion of Chicago Police Department traffic stops producing a citation declined from 72% in August 2015 to 41% in January 2016; over that same period, there was no analogous change for the Illinois State Police in Cook County. Similarly, the proportion of Chicago Police traffic stops for “equipment violations,” such as broken tail lights, dangling air fresheners, or missing license-plate lights, rose from less than 20% to more than 30% of stops (displacing stops for moving violations); there was no such compositional change in Illinois State Police traffic stops in Cook County.

Not only did the number of police-citizen interactions in Chicago rebound within 4 years of the end of stop and frisk but the racial composition of stopped drivers also shifted quickly toward the prereform racial composition of stopped pedestrians. The proportion of stopped drivers who were Black increased from 45 to 60% (Fig. 4), pulling the postreform population of stopped Chicagoans (meaning, people subject to pedestrian stops or traffic stops) closer, although not all the way back, to the prereform racial composition of stopped Chicagoans. Similarly, the proportion of stopped drivers who were Hispanic shifts toward the prereform proportion of stopped pedestrians who were Hispanic (fig. S1).

Fig. 4. Racial composition of stopped drivers shifts toward prereform composition of stopped pedestrians.

The blue line plots the proportion of Chicago Police traffic stops in which the driver was Black; the red line plots the proportion of stops overall, traffic and pedestrian stops together, in which the stopped person was Black. As police switched from pedestrian to traffic stops (Fig. 1), the racial composition of stopped drivers shifted toward the prereform composition of stopped pedestrians.

Most of this change in the racial composition of stopped drivers stems from the shifting geography of traffic stops across police beats, rather than from within-beat changes in the racial composition of stopped drivers. The fact that traffic stops increased more in beats that previously had many pedestrian stops (beats that also have high rates of Black residents in the population) accounts for approximately 80% of the 15-percentage-point increase in the proportion of stopped drivers who are Black (see the Supplementary Materials Section D). In other words, in the absence of any within-beat change in the racial composition of stopped drivers, the proportion Black would have risen from 45 to 57% citywide, rather than to 60%. The remaining three percentage points, or 20%, was driven by within-beat increases in the proportion of stopped drivers who are Black, meaning that, in some beats, officers made not only more stops but also different types of stops.

The racial composition and reason-for-stop changes interacted. As the Chicago Police began stopping (proportionally) more Black drivers, the citation rate fell faster for Black than for white drivers (Fig. 5). At the same time, the proportion of stops for equipment violations, rather than moving violations, rose more for Black drivers than for white drivers (Fig. 5). These differential changes are consistent with the hypothesis of substitution: Just as the Chicago Police began stopping (proportionally) more Black drivers, they also made (differentially) more proactive (or discretionary) stops of Black drivers. In other words, compared to white drivers, Black drivers were newly subject to the types of traffic stops that replaced pedestrian stops.

Fig. 5. Proactive traffic stops increase more for Black drivers than white drivers.

The late 2015 decrease in the citation rate and the increase in equipment stops affected Black drivers more than white drivers. Before 2015, there was no systematic difference in the citation rate for Black and white Drivers; in January 2016, there was nearly a 20-percentage-point difference. Similarly, the gap in the equipment stop rate for Black and white drivers grew sharply in late 2015. Both gaps gradually narrowed again after the initial period of substitution.

DISCUSSION

The recent series of reforms curtailing stop and frisk has generated a corresponding wave of scholarship investigating both intended consequences (reduced stops) and unintended ones (increased crime). We find a different unintended consequence: substitution of traffic stops for pedestrian stops in Chicago.

Our findings have implications for academic and policy discussions about the reform of proactive policing. Common suggested reforms of stop and frisk policies include not only improved selection and training of police officers but also additional mechanisms for external and internal accountability [e.g., (17)]. In Chicago, additional external accountability for pedestrian stops (in the form of more detailed documentation, to be reviewed by the ACLU) interacted with preexisting internal accountability mechanisms (for the level of policing activity, measured by number of stops, and also for crime counts) to produce substitution from pedestrian stops to traffic stops [see (3), especially chapter 3, for an informative discussion of the relative focus on activity numbers versus crime outcomes in Chicago Police accountability meetings]. Policymakers should weigh the possibility of that substitution when they consider accountability mechanisms that address one form of police activity but not others. Traffic stops may be an especially likely form of alternative activity when pedestrian stops are difficult. Los Angeles Police, for example, have been criticized for a policy of “stop and frisk in a car” (18): traffic stops, often for equipment violations, that disproportionally affect minority drivers.

The substitution of traffic stops for pedestrian stops also suggests a need for research on the effects of both types of stops on crime and traffic safety. In Chicago itself, future studies might evaluate whether substitution toward traffic stops reduced traffic crashes, building on existing research on the effects of pedestrian stops on crime [e.g., (5, 7)]. Such research would allow scholars examining the consequences of proactive pedestrian stops to incorporate the costs and benefits of substitution to traffic stops. More broadly, further work could investigate the equity implications of substitution of one police tactic for another.

Our findings raise two additional questions for future work. First, if studying the effect of reform on a single behavior is unlikely to characterize the full set of reform outcomes, how should researchers and policymakers define the set of outcomes to study in any particular case? We have been guided here by the qualitative record, but this approach may not generalize. Second, what are the conditions under which we should expect to observe the substitution of one tactic for another? These are key questions both for researchers and for policymakers.

MATERIALS AND METHODS

Traffic-stop microdata, from which we calculate traffic-stop counts and characteristics, are publicly available from the Illinois Department of Transportation. Pedestrian-stop microdata, from which we calculate pedestrian-stop counts and characteristics, are publicly available for 2016 and subsequent years (on the website of the Chicago Police Department) and were obtained through Freedom of Information Act requests for 2015 and prior years. See the Supplementary Materials for details and additional discussion.

Acknowledgments

We thank B. Ba for pointing toward this case. For expertise, we thank D. Godsel, K. Sheley, K. Towner, J. Rountree, W. Skogan, and G. Stoddard. For comments, we thank B. Ba, J. Glaser, G. Grossman, A. Lerman, M. Meredith, J. Mummolo, S. Raphael, W. Skogan, and T. Slough.

Funding: The authors acknowledge that they received no funding in support of this research.

Author contributions: Both authors (D.H. and D.K.) collected data, conducted analysis, and wrote the paper.

Competing interests: D.H. was an attorney for the ACLU’s national Immigrants’ Rights Project from 2016 to 2019 and continues to consult occasionally for the national ACLU. He has no affiliation with the ACLU of Illinois, and had no involvement with the ACLU activities discussed in this paper. D.K. declares no competing interests.

Data and materials availability: All data and code needed to replicate this analysis are available at https://doi.org/10.7910/DVN/HJNNDG. All other data needed to evaluate the conclusions in the paper are present in the paper and/or the Supplementary Materials.

Supplementary Materials

This PDF file includes:

Supplementary Text

Tables S1 and S2

Figs. S1 to S5

References

REFERENCES AND NOTES

- 1.New York Civil Liberties Union NYCLU, Stop-and-frisk data. Technical Report, 2020.

- 2.Mummolo J., Modern police tactics, police-citizen interactions and the prospects for reform. J. Polit. 80, 1–15 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 3.W. G. Skogan, Stop and Frisk and the Politics of Crime in Chicago. (Oxford Univ. Press, 2023). [Google Scholar]

- 4.K. Sheley, Reported Dramatic Decrease in The Number of Pedestrian Stops by Cpd Officers. (American Civil Liberties Union, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 5.T. Devi, R. G. Fryer, Policing the police: The impact of "pattern-or-practice" investigations on crime. Technical Report, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2020.

- 6.S. Charles, After 15 years, popular ‘Second City Cop’ blog goes dark. (Chicago Sun-Times, 14 January 2021). [Google Scholar]

- 7.B. Ba, R. Rivera, The effect of police oversight on crime and allegations of misconduct: Evidence from chicago. (Working Paper, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 8.Weisburd D., Majmundar M. K., Aden H., Braga A., Bueermann J., Cook P. J., Goff P. A., Harmon R. A., Haviland A., Lum C., Manski C., Mastrofski S., Meares T., Nagin D., Owens E., Raphael S., Ratcliffe J., Tyler T., Proactive policing: A summary of the report of the national academies of sciences, engineering, and medicine. Asian J. Criminol. 14, 145–177 (2019). [Google Scholar]

- 9.J. Williams, Effect of high-visibility enforcement on motor vehicle crashes. (National Institute of Justice, 2020). [Google Scholar]

- 10.T. R. Tyler, Why People Obey the Law. (Princeton Univ. Press, 2006). [Google Scholar]

- 11.A. E. Lerman, V. M. Weaver, Arresting Citizenship: The Democratic Consequences of American Crime Control. Chicago Studies in American Politics. (University of Chicago Press, 2014). [Google Scholar]

- 12.N. Husain, Laquan mcdonald timeline: The shooting, the video, the verdict and the sentencing. (Chicago Tribune, 18 January 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 13.M. Kapustin, J. Ludwig, M. Punkay, K. Smith, L. Speigel, D. Welgus, Gun Violence in Chicago, 2016, (University of Chicago Crime Lab, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 14.J. Gorner, After officers complain, chicago police simplifying stop reports required by aclu deal. (The Chicago Tribune, 2016). [Google Scholar]

- 15.ACLU, Racism in the rear view mirror: Illinois traffic stop data 2015–2017. (American Civil Liberties Union, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 16.P. Cassell, R. Fowles, What caused the 2018 What Caused the 2016 Chicago Homicide Spike? An Empirical Examination of the 'ACLU Effect' and the Role of Stop and Frisks in Preventing Gun Violence. (University of Illinois Law Review, 2018), p. 1581. [Google Scholar]

- 17.Fradella H. F., White M. D., Reforming stop-and-frisk. Criminol. Crim. Justice Law Soc. 18, 45 (2017). [Google Scholar]

- 18.C. Chang, B. Poston, ‘Stop-and-frisk in a car:’ Elite LAPD unit disproportionately stopped Black drivers, data show. (Los Angeles Times, 2019). [Google Scholar]

- 19.IDOT, Traffic and pedestrian stop study. Technical report, 2022.

- 20.CPD, Investigatory stop report data. Technical report, 2022.

- 21.R. Yu, L. Chang, Chicago police district demographics. 2022.

- 22.J. Gorner, While pedestrian stops by Chicago police plummeted, officers’ traffic stops soared, ACLU says. Chicago Tribune (2019); https://www.chicagotribune.com/news/breaking/ct-met-chicago-police-traffic-stops-20190111-story.html.

Associated Data

This section collects any data citations, data availability statements, or supplementary materials included in this article.

Supplementary Materials

Supplementary Text

Tables S1 and S2

Figs. S1 to S5

References