Abstract

Background

People experiencing homelessness frequently die young, from preventable and treatable conditions. They experience significant barriers to healthcare and are often critically ill when admitted to hospital. A hospital admission is an opportunity to intervene and prevent premature mortality by providing compassionate care and facilitating access to safe onward accommodation and support.

Methods

To quantify needs, a cross-sectional audit of inpatients experiencing homelessness across 15 acute hospital teams in London, was undertaken in February 2022. Integrated discharge and hospital homelessness teams were interviewed about each patient identified as homeless or vulnerably housed. Data was collected about patients' health, housing, support needs, and reasons for delayed discharges.

Results

Detailed information was gathered on 86 patients. There was a high level of clinical complexity and multimorbidity. For a safe discharge 60% of individuals were deemed to need accommodation providing high or medium level support and at the time of the audit, half were delayed discharges.

Conclusion

There is an urgent need for a range of intermediate/step down and longer-term accommodation and support to enable safe appropriate discharge from hospital and start to address the huge inequity in health outcomes of this population. This paper includes recommendations for clinicians and commissioners.

KEYWORDS: homelessness, delayed discharges, intermediate/step down care, multimorbidity, health disparity, vulnerable populations

Introduction

There are various reasons why people may become homeless. Homelessness is legally defined as ‘a household that has no home in the UK or anywhere else in the world available and reasonable to occupy’.1 This includes people who are rough sleeping, in temporary accommodation (including hostels), and those in insecure or inadequate housing (such as a shelter, sofa surfing or squatting). Homelessness is always devastating but, for some people, it may be a short-term situation, for example, following loss of a job or relationship breakdown. However, for others, homelessness can be a longer term problem, often linked to past or present traumatic experiences (including adverse childhood experiences), poverty and deep social exclusion, and can result in people cycling between streets, hostels, and other forms of temporary or insecure accommodation.2

People experiencing long-term homelessness often exhibit some of the poorest health outcomes in society and frequently die young, often from preventable and treatable conditions. Studies have shown mortality rates at least three-to-six times higher in people experiencing homelessness compared with housed populations3–5 and an average age of death of 51.6 years, 20 years younger compared with other deprived populations.6 For people who are street homeless or staying in emergency shelters, the mean age of death is during their 40s.7

Many common long-term conditions, including asthma, chronic obstructive pulmonary disorder, epilepsy, and heart problems, are more prevalent within this population,4,5 as are high rates of multiple health conditions and frailty, which occur at a much younger age than in the general population.8 In a hostel where most residents had a history of rough sleeping, their frailty scores were equivalent to people in their late 80s even though the average age of residents was 56.8 Conditions usually found in older people, such as dementia or cognitive impairment, urinary incontinence, malnutrition, poor mobility, and frequent falls, were highly prevalent. All of the residents had multiple health conditions, and the average number of conditions per person was seven. Occurrences of physical ill health in the homeless population are often accompanied by high rates of mental illness and/or substance use disorder.9

Aggregated data from 31 health needs audits, representing 2,776 people experiencing homelessness, found 78% had a physical health condition, 63% reported a long-term illness or disability, 82% reported having a diagnosed mental health problem, 29% had issues with alcohol, and 38% had issues with drugs.9 These figures are significantly higher compared with the general population, of whom 22% reported a long-term illness or disability, 12% reported mental health problems,9 1.4% had issues with alcohol,10 and 9.4% had taken an illicit drug over the past year.11

Homelessness is associated with a high prevalence of trauma, including adverse childhood experiences (ACEs). These ACEs might include a history of abuse, neglect, growing up in care, parental separation, having a parent with addiction or mental health problems, being in a household with domestic violence, among others.12–14 Studies have shown that 85% of people with multiple exclusion homelessness (which includes homelessness in addition to substance misuse, or institutional care, or contact with the criminal justice system) had experienced trauma in childhood.15 ACEs can impact the development of stable attachments, with the world often being viewed as fundamentally unsafe and/or others seen as untrustworthy. People might struggle to develop relationships or understand others' perspectives, or their own emotions. Emotional arousal can escalate quickly, and the combination of difficulty self-soothing, along with not having needs understood, can lead to conflict with others, self-directed harm, or substance misuse.13,14

Self-medicating with substances can be a response to trauma in an attempt to self soothe or numb emotional pain.9,14 In the health needs audits with people experiencing homelessness, 45% said they used alcohol or drugs to self-medicate to manage their mental health problems.9 Homelessness itself is also a risk factor for trauma,12 substance use, and poor mental health outcomes,12 such as being a victim or witness to an attack or sexual assault or being traumatised or retraumatised by services that leave someone feeling powerless or controlled.12

Despite the high level of healthcare needs for people experiencing homelessness, many needs remain unmet because of poor and delayed access to services.16 These challenges include practical difficulties in accessing primary care, with barriers including needing to demonstrate proof of address or ID when registering with a GP (despite this not being a legal requirement), and digital exclusion resulting from a lack of smart phone, or lack of follow-up care. In addition, people experiencing homelessness often face stigma, shaming, and discrimination when accessing both primary and secondary care services, particularly when they have concurrent substance misuse.16–19 These barriers, compounded by difficulties in developing trust as a result of complex trauma, frequently mean that there can be a delay in people getting the care they need until there is no choice, often resulting in high rates of unplanned emergency admissions in a critical condition.

Another cohort of people at risk of homelessness are those with uncertain or restricted immigration status who might have no recourse to public funds (NRPF). People with NRPF are not entitled to statutory housing support or benefits. However, if they have care and support needs, they can have their needs met through adult social care, because care and support provided through adult social care is not considered a ‘public fund’. This means, that irrespective of whether someone has recourse to public funds, the local authority has a duty to undertake a Care Act assessment of someone who has an ‘appearance of need’. If thresholds of need are met, they then might be required to provide accommodation. However, it can take several weeks for this assessment to be undertaken. Further guidance can be found online.20

If someone is homeless or at risk of homelessness, there is a statutory duty for the hospital to make a referral to the local authority20 under the Homelessness Reduction Act.22 For the local authority to provide appropriate support, as much information as possible needs to accompany this referral.

For many people experiencing homelessness, including those returning to temporary accommodation or a hostel, there might be no family or friends available to support their recovery. Therefore, they mgiht need to be further along in their recovery compared with people returning to accommodation with support. In addition, people admitted from the street will need suitable wrap-around supported accommodation to prevent an unsafe discharge.23

Given a current lack of available intermediate care and suitable longer term options, many people with health and care needs will remain in hospital longer or are placed into accommodation, such as hostels or other temporary accommodation, that might be inadequate to meet their needs.24 Additional information on levels of need for those living in hostels may be found in our other article in this issue.25 In addition, there are concerns that some people are still being discharged to the street.9

Rationale for audit

This inpatient audit was undertaken because of the absence of adequate data relating to hospital admissions regarding people experiencing homelessness. The aim was to understand and quantify what accommodation and support options were needed for timely and appropriate discharge from hospital of people affected by homelessness, to inform commissioning decisions.

Data are crucial to designing and delivering services that are able to address the needs of its users. Currently, data are not being routinely captured for this cohort because housing or homelessness status is rarely coded.

Method

The audit was a cross-sectional study of inpatients experiencing homelessness across 15 acute hospital teams in London, undertaken over 1 week in February 2022. Given time availability, it was not possible to gather information from every hospital across London. The hospitals that were invited to participate were within two integrated care system (ICS) areas together with all hospitals with a specialist homeless team across the region.

Invitations to participate were sent by email to integrated discharge and specialist homelessness teams, including Pathway teams. (Pathway teams give advice and expertise as well as advocacy about inclusion health issue and homelessness for inpatients; see pathway.org.uk for further information.) All invited hospital teams that agreed to participate in a 2-h telephone interview were asked in preparation of the interview to gather information about all inpatients on their caseload on the day of the interview, who, from their knowledge, were experiencing or at risk of homelessness. These caseloads included individuals who were rough sleeping (street homeless) or living in poor, insecure temporary or unsafe conditions, including sofa surfing, staying in a hostel, night shelter, or squatting.

During the telephone interview, the interviewer completed the survey (entering the information onto Survey Monkey). The survey explored patients' health, housing, and support needs, as well as reasons for delayed discharges. Data collected were both quantitative and free text.

This audit was completed to guide commissioning decisions. Although formal ethical approval was not required because this was an audit, no patient identifiable information was captured. The survey questionnaire is provided as supplementary material S1.

Analysis

Structured interviews were completed by the audit team using a standardised questionnaire. The audit team noted any additional comments within free-text boxes. Quantitative variables were summarised using descriptive statistics. Reasons for admission and other clinical conditions were coded following data collection by CS. Level of need for different types of accommodation and support were coded using all appropriate information collected on each individual (CS,TJ).

Results

In total, 114 people were identified as being homeless or vulnerably housed. Detailed information was available for 86 of those patients. The 28 people whose details were not considered in the analysis were excluded because of a lack of adequate information resulting from insufficient time to complete the survey by hospital staff given that, for some teams, 2 h was inadequate for the high number of patients on their caseload.

The complexity of ill health was extremely high, with many with life-threatening physical health problems, poor mental health, and complications of substance misuse. Out of the 86 people for whom we had information, some of the conditions and reasons for admission included:

14 who were critically ill on admission, such as being unconscious, following a cardiac arrest, or with severe sepsis (several of whom needed intubation);

11 admitted following major trauma (from accidents or suicide attempts) or needing neurosurgery or spinal surgery;

11 needed vascular surgery (six of whom needed limb amputations);

seven admitted with septic arthritis, osteomyelitis, or abscess;

six had acute cerebrovascular events;

six had cancer;

four had end-stage renal failure;

10 had diabetes;

16 had liver disease/pancreatitis or other gastrointestinal conditions; and

10 had dementia.

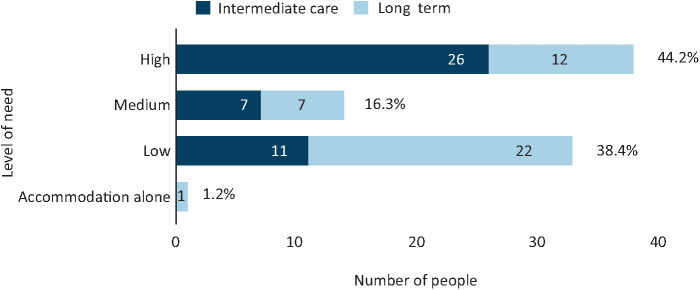

In addition, 15 people (17%) had between five and eight concurrent physical health conditions. Over one-third of patients displayed trimorbidity, a combination of physical and mental ill health and substance use disorders (Fig 1). More than half (55%) were believed to have care needs and around 30% were suspected to have impaired cognitive or mental capacity.

Fig 1.

Health needs.

Almost all patients (92%) were unable to return to their pre-admission living situation, because it was either unsuitable for their health and care needs, or there was no accommodation to return to (patients were either rough sleeping at admission or were being evicted from their previous accommodation). Additionally, for around 30%, there were safeguarding concerns, of which over half (14 people) relating to self-neglect. Other safeguarding concerns were hoarding, self-harm, domestic violence/abuse, or their property had been cuckooed, meaning, often because of their vulnerability, their property had been taken over by other people for illegal activities, such as taking and selling drugs or sex.

Lack of appropriate move-on options

Despite this high level of complexity, there was a lack of appropriate accommodation and support available for people to be discharged to. Teams identified at least 21 people (24%) who were highly likely to be discharged to a destination that was suboptimal and/or unlikely to meet their needs (see case examples below).

When looking at needs of the entire caseloads, only one person out of 86 had a need for housing alone. For everyone else, to achieve a safe discharge, there was also a need for some additional support or care.

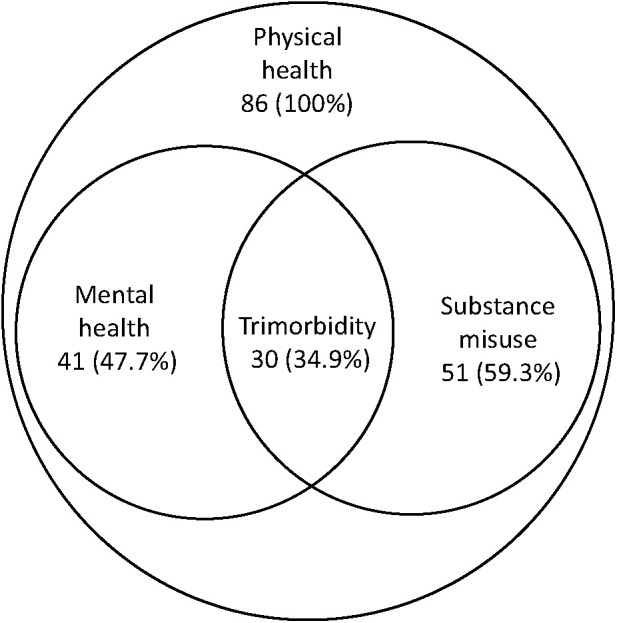

Level of need for a safe discharge

The levels of need were categorised into low, medium, and high, for both intermediate (step-down) and long term.

Low need included in-reach or peripatetic support for someone who was otherwise able to be independent.

Medium need was for people with support needs that required onsite non-clinical staff but with clinical in-reach.

High need was a need for clinical staff onsite, with nurses or carers overnight.

For around half (51%), these needs were likely to change over a matter of weeks or months to support, for example, ongoing recovery or while awaiting further assessment or regularisation of immigration issues. Their needs were categorised as intermediate.

For the other 48% of patients, their needs were unlikely to change over a period of weeks or months; thus, their long-term accommodation and support needs were determined (Fig 2).

Fig 2.

Projected summary of need.

Level of need: high

Of the 86 patients, 38 (44%) were determined to have a high level of need (Fig 2). Around two-thirds of these (26/38, 68%) fell into the intermediate level, because they had complex needs, including neuro rehab or physical rehab needs that were likely to improve over time if managed in a specialist neurological/physical rehabilitation setting. Most of these individuals had additional significant mental health and/or substance use disorders and, thus, would likely not be accepted by many mainstream rehabilitation services (see case examples below).

For those who had care needs that were unlikely to change or improve (12/38), a long-term setting, such as a specialist care home, was deemed appropriate. Several people who fell within this group would be considered too young for mainstream care homes. Their needs were often complex, with a combination of physical health needs in association with mental health difficulties, such as brain injury and dementia and/or addictions.

Case example: high-level need: intermediate. Man, aged 55–64 years. This patient had been admitted because of alcohol withdrawal. He had been alcohol dependent for many years and was self-neglecting. He was very deconditioned on admission and had difficulty with his activities of daily living, requiring two-person assistance. Before admission, he was living in temporary accommodation. The team reported that he wanted support for his alcohol dependency and to go to alcohol rehab. Although he was ‘medically fit for discharge’, at the time of the survey, there was no intermediate care or alcohol rehab available for him to be discharged to. The team was considering a range of accommodation possibilities, including temporary accommodation with a package of care. They made a referral to an intermediate-care hospital for complex needs that specialises in caring for individuals who have experienced homelessness; however there were no beds available. Even if alcohol rehab had been available, it was unlikely he would receive this because of his significant physical health needs.

Case example: high-level need: long term. Woman, aged 45–54 years. This patient was admitted with severe exacerbation of confusion on a background of likely Korsakoff's dementia. She had a long-standing history of alcohol dependency and was living in a hostel before admission. Her level of care and support needs were high and the hostel staff were not able to continue to support her. She had had several recent hospital admissions, with discharges back to the hostel following each admission. Following her previous admission, she was discharged with a care package and in-reach support from an inclusion health nurse. However, her needs were greater than what could be provided and, within a short time, she was readmitted. Given her dementia, alcohol services did not feel there was any potential for rehabilitation.

Level of need: medium

There were a further 14 people (16%) who had a range of complex needs that still needed accommodation with 24/7 non-clinical support with additional clinical in-reach (Fig 2). Medium support might include specialist small units to support, for example, vulnerable women or people with dual diagnosis, or could include a high-support hostel. People with intermediate medium-level needs had a condition that needed further time for recovery/assessment and from which they would be expected to improve.

Case example: medium-level need: intermediate care. Man in his 50s. This patient was admitted following a significant stroke (as a complication of diabetes), with incontinence and poor mobility. He had been street homeless with diabetes that had not been treated for 2 years. He had a history of alcohol and high cannabis use and safeguarding concerns had been raised previously by outreach teams. During this admission, he was deemed to need specialist wheelchair-accessible rehabilitation. However, there were disputes around which local authority was responsible for his housing and social care needs. It took over 3 weeks to gather adequate information to resolve these disputes and enable planning for a safe discharge.

Case example: medium-level need: long term. Man, aged 45–54 years. This patient was admitted with abdominal pain, severe leg ulcers, worsening renal function, and self-neglect. He had a history of schizophrenia and hepatitis B and was a former injecting-drug user. At time of admission, he was taking methadone but was not well engaged with addiction services. He had been evicted from his previous temporary accommodation and needed accommodation with onsite staff to support his mental health difficulties, engagement with substance misuse services, and his physical health issues.

Level of need: low

An additional 33 people (38%) had lower-level needs, which were likely to be long term for 22 of this cohort. This included people who were deemed to be able to manage in independent accommodation in the community, such as Housing First, but needed additional wrap-around support or in-reach from services, such as adult social care, community mental health teams, or district nursing. None of these people were felt to be able to sustain independent accommodation without additional support. (Housing First is an international, evidence-based approach that prioritises access to permanent housing with tailored support and case management for people experiencing homelessness with multiple and complex needs; see www.housing.org.uk for further information.)

People with intermediate low-level needs included those who could manage independently (eg in a hotel or B&B) but who had ongoing needs (such as immigration or benefits, or completion of assessments) that were required before they could move into other accommodation.

Case example: low-level need: intermediate. Man, aged 55–64. This patient was admitted with chest pain, nephrotic syndrome, and renal failure. During admission, it was found he had prostate cancer and went on dialysis. Although a UK national, he had only returned to the UK from Nigeria 1 day before admission, having lived there since 2016. This meant that there were issues with ordinary residence and entitlement to benefits and support with accommodation from the local authority. He had been medically fit for discharge for 14–20 days before the survey, with discharge being delayed beause of a lack of accommodation to go to, while awaiting responses around eligibility.

Case example: low-level need (independent accommodation) with long-term community in-reach.

Man, aged 651. This patient was admitted with acutely ischaemic leg. He needed an embolectomy and fasciotomy. He had a history of diabetes, atrial fibrillation, and transient ischaemic attacks. He was also self-neglecting. His previous accommodation was repossessed; staff believed that the repossession was because it had become uninhabitable. With additional support from adult social care and district nurses, he could manage in his own home.

Delayed discharge

The audit found 48.8% of discharges (42 people) were delayed and, of those, 29% (12 people) were delayed for 2 or more weeks. In conjunction with a lack of available appropriate accommodation and support options, there were delays resulting from people awaiting further assessments from adult social care, disputes between local authorities, or a need to obtain evidence as to eligibility for benefits or support. The latter was particularly relevant for people with restricted or uncertain eligibility for public funds, who often required legal advice. Given all of these reasons for delayed discharges, nearly half of the people had remained in hospital longer than they needed, over half of whom were delayed longer than a week.

No recourse to public funds

There were 16 people (19%) who had restricted or uncertain eligibility for public funds and another eight (9%) whose eligibility was still being determined. This meant that local authority housing services might not have a statutory duty to support them. Around 42% (10 people) of these experienced a delayed discharge, three of whom had been deemed ready for discharge for two weeks or longer. Reasons for delays included awaiting assessments and outcomes by adult social care services, with no other options available. Of the 16 people, there were 10 who were reported to have care needs, of whom seven had been referred to social services for an assessment and were either still awaiting an outcome at the time of the audit or the team were challenging the outcome. The three who had not yet been referred were still undergoing treatment; thus, assessment of needs was not yet clear.

Discussion

This audit highlights how people experiencing homelessness who are admitted to hospital are often critically ill with a range of complex needs. These encompass not only profound physical health needs, but are also linked with psychological, emotional, mental health, addiction, social, housing, and immigration needs.

To complete each in-depth interview, an ample amount of time was needed by both the hospital teams and those conducting the survey. The significant pressures that the hospital teams are under and the large number of people on some teams' caseload meant that some teams were not able to share information about everyone on their caseload. An additional limitation was that some hospitals were not able to provide detailed data because people experiencing homelessness were not consistently identified. Where a hospital team had a specialist homelessness team, the data was more thorough, giving a richer understanding of the patients' needs.

People experiencing homelessness are dying unacceptably young, often from preventable or treatable conditions. Although homelessness is affected by a range of issues, including housing, immigration, and welfare systems, the NHS has a key role in addressing these huge health inequalities.

A hospital admission can serve as a vital opportunity to assess and deliver interventions that can begin to address these complex issues, start the process of engagement, and prevent premature mortality. Given that lack of trust can be a significant barrier to good engagement and contributes to self-discharge and late presentations, a compassionate, person-centred approach is vital to reduce these barriers. Clinical advocacy can provide the support needed to start the process of recovery, including supporting applications for housing and social care and preventing unsafe discharge.

Considering the complexity of need, multiple health conditions, premature ageing, and frailty in people experiencing homelessness, needs-based rather than age-based assessments are essential for equitable care, as highlighted in National Institute for Health and Care Excellence (NICE) Guidance NG214.26 These assessments also need to take discharge destination and living situation in the community into account. If the patient has a support worker or key worker, contacting them can be very valuable for collateral information and to explore what pre-existing support, if any, is currently provided. Additional information on levels of need for those living in hostels may be found in our other article in this issue.25 Clinicians and allied health professionals can have an important role in supporting referrals to adult social care and housing services, to facilitate the provision of appropriate accommodation and support.

Some hospitals have recognised the value of specialist multidisciplinary teams with inclusion health and housing expertise (eg Pathway teams) or housing workers embedded within integrated discharge teams. These teams can help navigate and support integration between hospital and community health, housing, and social care. Most of the detailed information of this audit came from such teams.

In this audit, approximately half of the inpatients were delayed discharges because of a lack of a safe and appropriate place to be discharged to. This demonstrates the clear lack of adequate accommodation and support options across London for all levels of need. This has been previously demonstrated and can be an important reason for unsafe or delayed discharge.22 The gaps identified in this audit were particularly significant for people with complex physical health, mental health, and substance use issues that require 24-h nursing support, both intermediate and long term. NICE Guidance NG214 highlights the benefit and cost effectiveness of intermediate care for people experiencing homelessness who have ongoing needs but no longer require inpatient care.26 Having a safe place for recovery or on-going case working can help reduce the pressure on hospital beds while preventing unsafe discharges. To support hospital flow, there is an urgent need for more intermediate care/step-down beds. This can also be particularly helpful for people with restricted or uncertain eligibility for public funds where there can be considerable delays in establishing whether they could be supported under the Care Act and what their rights and options are regarding their immigration status.

For long-term recovery and to reduce emergency unplanned admissions, there is also an urgent need for additional support in the community. People with lived experience can be invaluable in providing support27 along with partners from health, housing, and social care services, who are skilled in trauma-informed practice and person-centred care, and recognise the importance of long-term wraparound support. This might include community multidisciplinary peripatetic teams that can deliver in-reach services to temporary and supported accommodation.

With the number of people rough sleeping up by 24% in the past year28 and over 300,000 households estimated to become at risk of homelessness in the next year,29 we must continue to build upon the achievements made during the Coronavirus 2019 (COVID-19) pandemic. This includes improving access to a consistent and sustained service offer that is person centred, trauma informed, and diverse in its ability to meet the range of housing, health, care, and support needs of this population.

As The Marmot Review states, to achieve equity, people with the highest need should receive the greatest resource (proportionate universalism).30 This audit shines a light on the extreme health inequity for people experiencing homelessness, but also presents opportunities for change and improvement.

Recommendations

The audit demonstrated the gap between the ideal system offering for this population (as per NICE guidance), and what is available in current practice. It reinforces the value of an integrated partnership and suggests further action is needed to ensure that there are adequate options available across the system to meet the diverse range of needs of this population.

Recommendations for clinicians

Recognising that homelessness is not a lifestyle choice. It is often the result of years experiencing trauma, with substance misuse and poor mental health intrinsically tied in, using alcohol and/or drugs to self-medicate.

Asking people if they have a safe place to go upon discharge. Not only is this important to identify people experiencing homelessness early, but also acknowledges the difference in recovery experiences for those going home to someone who can look after them compared with those who have no support network. Given that frailty scores among this population are on par with those of older people, they should be treated with the same concerns and empathy.

Recognising the need for step-down provision to support further assessments, recovery or rehabilitation

Complete a Duty to Refer 21 if the person is homeless or at risk of being so.

Use existing NHS housing status codes as part of routine data collection.

Consider and challenge bias and perceptions: recognise that people experiencing homelessness frequently have a range of complex and unmet needs, have often experienced significant trauma, and need our help.

Working with voluntary, community, and social enterprise (VCSE) partners as well as with peer advocates to support registration with local primary care services.

Care packages to be based on an individual's needs rather than biological age (as per NICE guidance). This could help people to receive support sooner and prevent poorer outcomes.

Upskill on trauma-informed practice, reflective practice, and training to de-escalate crises. This would be helpful in dealing with difficult behaviours (relating to mental health and/or substance use) and prevent discharges or self-discharges to the street.

Having an understanding of the patient's needs and the impact of their discharge location on their recovery. For example, someone requiring physical or neurological rehabilitation will not receive adequate support if discharged to a hostel for complex needs. Similarly, discharging someone who has detoxed to a wet hostel can trigger their substance use and cause them to relapse.

Access available resources (eg NRPF Network; www.nrpfnetwork.org.uk/) for people who have restricted or uncertain eligibility to public funds.

Recognise the need to prevent and address withdrawal in someone with substance use disorder as a matter of urgency to prevent disengagement, self-discharge, and perceived challenging behaviour.

Recommendations for commissioners

More accommodation options that are able to address the varying needs of this population and support personal choice and control. This includes an urgent need for a range of intermediate care/step-down provisions to support hospital discharge, as well as longer-term placements, such as specialist care homes.

See hospital admission as an opportunity to begin to address complexity of need and enable access to expertise within hospitals from multidisciplinary teams who are skilled in inclusion health, housing law, and access to immigration advice.

Recognise the value of involving people with lived experience to support people to attend appointments and with engagement, and to support co-production of services.

Ensure access to continued support in the community from inclusion health, peers with lived experience, and floating support within temporary accommodation and hostels.

Collaboration and co-production of shared protocols with health, housing, social care, and lived-experience colleagues that aim to enable more timely identification and assessments, as well as prevent self-discharges, discharges to the street, and trauma-induced situations.

Improve support for people who have restricted or uncertain eligibility for public funds through enabling timely access to legal support and increasing staff awareness around relevant legislation, policy, and practice.

Fund implementation of NHS housing codes in acute trusts.

Summary

What is known?

People experiencing homelessness and multiple disadvantage have some of the worst health outcomes of any group in society and yet face significant barriers to accessing health and social care. A hospital admission is an opportunity to begin to address some of these issues, which often need a multidisciplinary approach.

What are the questions?

What are the reasons for hospital admission for people experiencing homelessness? What are the barriers to safe discharge and what action can be taken as integrated care partnerships to support timely and safe discharge from hospital and improve out-of-hospital care for people experiencing homelessness?

What was found?

The complexity of ill health was extremely high, with many with life-threatening physical health problems, poor mental health, and complications of substance misuse. At the time of the audit, half of the cohort were deemed delayed discharges by the hospital teams. Reasons for delays included a lack of safe appropriate discharge destinations, including specialist accommodation and support, waiting for assessments from local authority housing or adult social care, or awaiting further information about eligibility for support.

Implications for practice:

For safe and timely discharge from hospital, there is a need for better identification of people who are admitted with no safe discharge destination, holistic multiagency trauma-informed support, and improved access to a range of step-down/intermediate and long-term accommodation and support options to facilitate ongoing recovery. More detailed recommendations for clinicians and commissioners are included following the discussion.

Supplementary material

Additional supplementary material may be found in the online version of this article at www.rcpjournals.org/content/clinmedicine:

S1: Survey

References

- 1.Public Health England . Homelessness: applying all our health. www.gov.uk/government/publications/homelessness-applying-all-our-health/homelessness-applying-all-our-health#:∼:text=The%20legal%20definition%20of%20homelessness,London%20and%20the%20South%20East [Accessed 7 July 2023].

- 2.Crisis . Home for all: the case for scaling up Housing First in England. www.crisis.org.uk/media/245740/home-for-all_the-case-for-scaling-up-housing-first-in-england_report_sept2021.pdf [Accessed 7 July 2023].

- 3.Bowen M, Marwick S, Marshall T, et al. Multimorbidity and emergency department visits by a homeless population: a database study in specialist general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2019;69:e515–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Lewer D, Aldridge RW, Menezes D, et al. Health-related quality of life and prevalence of six chronic diseases in homeless and housed people: a cross-sectional study in London and Birmingham, England. BMJ 2019;9:e025192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 5.Aldridge RW, Story A, Hwang SW, et al. Morbidity and mortality in homeless individuals, prisoners, sex workers, and individuals with substance use disorders in high-income countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Lancet 2017;391:241–50. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Aldridge RW, Menezes D, Lewer D, et al. Causes of death among homeless people: a population-based cross-sectional study of linked hospitalisation and mortality data in England. Wellcome Open Res 2019;4:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 7.Office for National Statistics . Deaths of homeless people in England and Wales. www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/datasets/deathsofhomelesspeopleinenglandandwales [Accessed 7 July 2023].

- 8.Rogan-Watson R, Shulman C, Lewer D, Armstrong M, Hudson B. Premature frailty, geriatric conditions and multimorbidity among people experiencing homelessness: a cross-sectional observational study in a London Hostel. Hous Care Support 2020;23:77–91. [Google Scholar]

- 9.Hertzberg D, Boobis S. Unhealthy state of homelessness 2022: findings from the Homeless Health Needs Audit. https://homeless.org.uk/knowledge-hub/unhealthy-state-of-homelessness-2022-findings-from-the-homeless-health-needs-audit/ [Accessed 7 July 2023].

- 10.Public Health England . Alcohol dependence prevalence in England. 2017. www.gov.uk/government/publications/alcohol-dependence-prevalence-in-england [Accessed 7 July 2023].

- 11.NHS Digital. Statistics on drug misuse, England, 2019. https://digital.nhs.uk/data-and-information/publications/statistical/statistics-on-drug-misuse/2019 [Accessed 7 July 2023].

- 12.FEANTSA: European Federation of National Organisations Working with the Homeless . Recognising the link between trauma and homelessness. www.feantsa.org/download/feantsa_traumaandhomelessness03073471219052946810738.pdf [Accessed 7 July 2023].

- 13.Song MJ, Nikoo M, Choi F, et al. Childhood trauma and lifetime traumatic brain injury among individuals who are homeless. J Head Trauma Rehabil 2018;33:185–90. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Sundin E, Baguley T. Prevalence of childhood abuse among people who are homeless in Western countries: a systematic review and meta-analysis. Soc Psychiatry Psychiatr Epidemiol 2015;50:183–94. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 15.Lankelly Chase Foundation . Hard edges: mapping severe and multiple disadvantage, England. http://lankellychase.org.uk/wp-content/uploads/2015/07/Hard-Edges-Mapping-SMD-2015.pdf [Accessed 7 July 2023].

- 16.Armstrong M, Shulman C, Hudson B, Stone P, Hewett N. Barriers and facilitators to accessing health and social care services for people living in homeless hostels: a qualitative study of the experiences of hostel staff and residents in UK hostels. BMJ Open 2021;11:e053185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Purkey E, MacKenzie M. Experience of healthcare among the homeless and vulnerably housed a qualitative study: opportunities for equity-oriented health care. Int J Equity Health 2019;18:101. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 18.Reilly J, Ho I, Williamson A. A systematic review of the effect of stigma on the health of people experiencing homelessness. Health Soc Care Commun 2022;30:2128–41. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Ramsay N, Hossain R, Moore M, Milo M, Brown A. Health care while homeless: barriers, facilitators, and the lived experiences of homeless individuals accessing health care in a Canadian regional municipality. Qual Health Res 2019;29:1839–49. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 20.NRPF Network/ Assessing and supporting adults who have no recourse to public funds (England): Practice guidance for local authorities. NRPF Network, 2023. http://guidance.nrpfnetwork.org.uk/reader/practice-guidance-adults/ [Accessed 1 July 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Department for Levelling Up, Housing and Communities A guide to the duty to refer. www.gov.uk/government/publications/homelessness-duty-to-refer/a-guide-to-the-duty-to-refer [Accessed 1 July 2023].

- 22.UK Government . Homelessness Reduction Act 2017. www.legislation.gov.uk/ukpga/2017/13/contents/enacted [Accessed 7 July 2023].

- 23.Department of Levelling Up, Housing and Communities . Ending rough sleeping for good. www.gov.uk/government/publications/ending-rough-sleeping-for-good/ending-rough-sleeping-for-good [Accessed 7 July 2023].

- 24.Dorney-Smith S, Hewett N, Burridge S. Homeless medical respite in the UK: a needs assessment for south London. Br J Health Care Manag 2016;22:405–13. [Google Scholar]

- 25.Shulman C, Nadicksbernd JJ, Nguyen T. People living in homeless hostels: a survey of health and care needs. Clin Med 2023;23:387–94. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 26.National Institute for Health and Care Excellence . Integrated health and social care for people experiencing homelessness. www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng214 [Accessed 7 July 2023]. [PubMed]

- 27.Groundswell . #HealthNow literature review update: how has patient experience changed for people who are homeless? https://groundswell.org.uk/2022/healthnow-literature-review-patient-experience/ [Accessed 7 July 2023].

- 28.Booth R. Number of people sleeping rough in London up 24% in a year. The Guardian, 30 October 2022. www.theguardian.com/society/2022/oct/30/number-of-people-sleeping-rough-in-london-up-24-in-a-year [Accessed 7 July 2023].

- 29.Watts B, Bramley G, Pawson H, et al. The Homelessness Monitor: England 2022. www.crisis.org.uk/ending-homelessness/homelessness-knowledge-hub/homelessness-monitor/about/the-homelessness-monitor-great-britain-2022/ [Accessed 7 July 2023].

- 30.Marmot M, Goldblatt P, Allen J, et al. Fair society, healthy lives (The Marmot Review). www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review/fair-society-healthy-lives-exec-summary-pdf.pdf [Accessed 7 July 2023].