Abstract

People experiencing homelessness have extremely poor health outcomes and frequently die young. Many single homeless people live in hostels, the remit of which is to provide support to facilitate recovery out of homelessness. They are not usually designed to support people with high health or care needs. A cross-sectional survey was developed with, and completed by, hostel managers to explore and quantify the level of health and care needs of people living in their hostels. In total, 58 managers completed the survey, with information on 2,355 clients: 64% had substance use disorder, 56% had mental health issues, and 37.5% were in poor physical health. In addition, 5% had had more than three unplanned hospital visits in the previous month, and 11% had had safeguarding referrals submitted over the past year. Barriers to getting support and referrals accepted were highlighted, particularly for people with substance use disorder. Hostel managers identified 9% of clients as having needs too high for their service, while move-on options were scarce. Our study highlights significant unmet needs. Health and care services are not providing adequate support for many people living in hostels, who often have very poor health outcomes. This inequity needs to be considered and addressed as a matter of urgency.

KEYWORDS: homeless hostels, unmet health and social care needs, safeguarding referrals, adult social care referrals, barriers to accessing services

Introduction

People experiencing homelessness often exhibit some of the worst health inequalities, with some of the poorest health outcomes in society. They frequently die young, unsupported, from preventable and treatable conditions.1–4 Homelessness does not only include people who are sleeping outside on the street, but also those staying with friends or relatives on their sofas or floors (‘sofa surfing’), squatting or in insecure or temporary accommodation, such as hostels.

Many people experiencing homelessness have a combination of physical health, mental health and substance misuse problems (sometimes referred to as trimorbidity).5,6 A history of complex trauma, including adverse child experiences, is common and often a factor contributing to substance use disorder and mental health difficulties.7 The health of people experiencing homelessness is negatively impacted by a lack of appropriate accommodation, exclusion from services and lack of person-centred support.8 As their health continues to deteriorate, there are increasingly fewer accommodation options that can provide the high and consistent levels of support required to address health and care needs. Given the lack of alternative options, many people with high healthcare and support needs are in homeless hostels.

Although homeless hostels are a form of ‘supported housing’ with a remit to accommodate people who have support needs, such as substance use disorder or mental health difficulties, they are not usually designed for people with high levels of physical health or social care needs.9 In most cases, hostels are supposed to be a short-term solution (usually up to 2 years), mostly working within a recovery-focused model, with the aim of facilitating access to addiction and health services, training and meaningful activities to enable a move out of homelessness.6,9,10

Despite this, many people living in homeless hostels have high levels of unmet health and care needs and many remain homeless for many years (often cycling between hostels, the street and other forms of temporary accommodation).11 Frailty, multiple health conditions and conditions usually associated with older people are prevalent within some hostel populations.12 Within a cohort of people experiencing homelessness with an average age of 56 years, frailty scores were equivalent to people in their late 80s from the general population. The average number of long-term conditions per person was seven. Cognitive decline, falls and poor mobility were present in almost half of the cohort. Despite this, only 9% had any support from adult social care or a package of care.12

Qualitative research suggests that this level of need is not unusual and hostel staff are often left to support people with significant health and social care needs without sufficient specialist support.9 Hostel staff are not trained to deliver health interventions or to be carers. They are not allowed to perform regulated activity, such as personal care, and, yet, because of a lack of anyone else to do so, they often take on burdens and responsibilities that are outside of their job roles.13 This comes at a cost, with burnout rates among staff being extremely high.14 In addition, many hostel residents are not receiving the degree of care and support they require, likely contributing to a reduction in quality of life, increased morbidity and premature mortality.

To inform the development of services that meet the needs of hostel residents, the level of met and unmet needs of people residing in homeless hostels were explored and quantified using a cross-sectional survey of a sample of hostels in London, UK.

Methods

The survey was developed in two phases. Initially, the survey was co-designed by CS (inclusion health clinician and researcher) and health and care leads (MB and JL) from St Mungo's. Some of the survey questions came from different formats used previously by CS and BH as part of other work on frailty and palliative care within homeless populations.12,13 Some of the questions were derived from Supportive and Palliative Care Indicator tool for all (SPICT-4ALL),15 the surprise question16 and comprehensive geriatric assessments. The survey was then further developed and adapted specifically for this use following engagement with hostel managers from across London.

The survey was designed to be completed online by hostel managers about the clients within their service. A broad range of supported accommodation and hostel services were surveyed in both phases. They range in size from small semi-independent accommodation (often five to eight units) to larger hostels (15–80 units). Typically, the accommodation is single rooms with shared facilities. There is a range of staffing models within these services, but the larger, complex needs hostels usually have at least two support workers on shift, although might only have a concierge at night.

Hostel managers completed one survey for their entire caseload. It was a non-clinical assessment containing closed and open questions to explore staff's perceptions of the health and social care needs of their clients, and their ability to access support and appropriate move on accommodation.

Phase 1

The survey was circulated via email to all eligible St Mungo's services in London in March 2022. Given that we were focusing on identifying unmet health and social care needs among people with often undiagnosed frailty and premature ageing, hostels specifically for young people (aged 16–25) were excluded because of fewer health and social care needs within this age group. We also excluded non-accommodation-based services, such as outreach services. Managers from 26 St Mungo's services across London responded. These included managers from first-stage hostels, semi-independent accommodation and assessment hubs (Box 1).

Box 1.

Hostel definitions

| Here, we define the different types of services that took part in the survey. |

| First-stage hostel |

| First-stage hostels typically cater for people with a recent history of rough sleeping with complex needs (ie those whose needs cannot be met by the intervention of a single agency). This often includes those with trimorbidity. Funding requirements typically require residents to move on within 24 months, although this can vary significantly depending on the availability of move-on accommodation within the local housing pathway. Support provided is 24 h by support workers who are generally not trained in health or care, and can be either single or multiple cover depending on the specific needs catered for. Residents are often on ‘excluded licence’ agreements. |

| Semi-independent accommodation |

| Semi-independent accommodation provides a lower level of support compared with first-stage hostels. It is often delivered in a smaller number of shared units of accommodation for people able to maintain a relative degree of independence with more targeted support. It uses a variety of tenure types, including assured shorthold tenancies and excluded licences. Residents are typically expected to move on (often into independent accommodation) within 24 months. It also caters for people with complex needs but where the risks associated with those needs can be managed without 24-h supervision. |

| Assessment centres |

| Assessment centres provide rapid assessment of housing and support needs for people experiencing homelessness. The length of stay can vary but typically move-on into an appropriate housing option is expected within 28 days. They can involve an element of reconnection involving advocacy with the Local Authority in which the resident has a ‘local connection’ as defined by the housing act. |

Phase 2

Following the demonstration of interest and feasibility of Phase 1, an engagement meeting was held with an additional eight hostel providers from across London (Riverside, Look Ahead, Evolve Housing, De Paul Charity, Thames Reach, Salvation Army, Single Homeless Project and Providence Row Housing Association) to explore their interest in cascading a similar survey across their equivalent services. This led to further co-development of the survey, resulting in some minor modifications and additional questions. The second phase of this online survey was completed by an additional 32 services in September 2022.

See supplementary material S1 for survey, with _ marking edited or additional questions for the second phase survey. Where we use the term ‘hostel’, we are referring to first-stage hostels, semi-independent accommodation and assessment hubs.

Analysis

The survey collected both qualitative and quantitative data via open and closed questions. Quantitative data were analysed by RF. Descriptive statistics were used to provide a narrative summary of the data. Qualitative data from the open questions within the survey were analysed by BH using thematic analysis.17 Qualitative and quantitative data were analysed concurrently, with discussion between the two researchers.

Results

Phases 1 and 2 collated information from 58 sites with information on 2,355 clients in total (Fig 1). In Phase 1, responses were collected from managers from 26 St Mungo's hostels representing 1,171 (49.7% of the sample) clients. In Phase 2, a further 32 hostel managers from a range of providers completed the updated survey, representing 1,184 clients. Both phases produced similar results with the exception of the additional questions used in Phase 2.

Fig 1.

Number of clients captured in the survey.

Overview of health and care needs

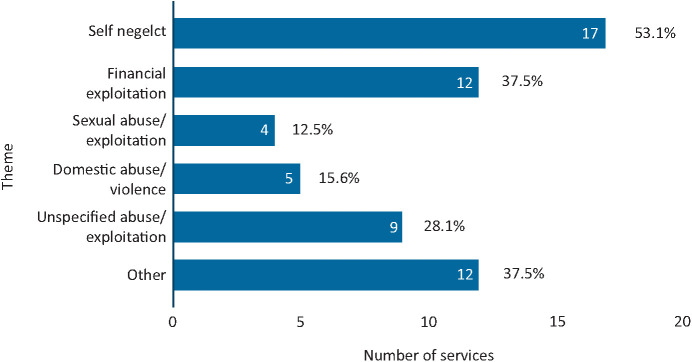

Within the surveys, a range of healthcare issues and conditions were listed and managers reported the number of people within their hostel who had each condition (Fig 2). These included some issues and conditions normally associated with an older population. Managers reported that just over a quarter, 25.9% (n=609) of clients had more than one of the listed problems and that 13% (n=299) had at least three.

Fig 2.

Range of clinical complexity.

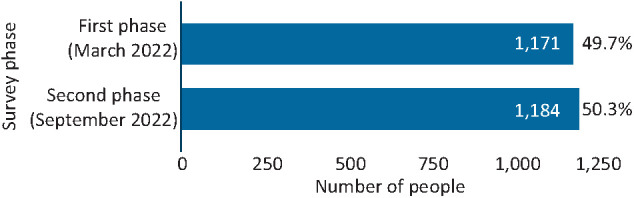

Phase 2 explored overall rates of physical health, mental health and substance misuse that impacted clients' ability to function in their day-to-day lives. Managers reported that nearly two-thirds of clients (63.9%, n=757) had substance use disorder, over half (56%, n=663) experienced mental health issues, and over one-third (37.5%, n=444) had significant physical health issues. For almost one-third of clients (30.8%, n=365), all three of these issues impacted their daily lives (Fig 3).

Fig 3.

Issues affecting the daily lives of clients.

Managers were also asked to report how many of their clients had general poor or deteriorating health, and this accounted for 301 (25.4%) of clients.

Challenges to getting health and care needs met

A range of challenges around supporting clients with complex needs were raised in the qualitative data. Overall, hostel managers felt that other services did not respond to the needs of their clients, leaving hostel staff supporting people with high needs in an environment not designed for this purpose.

Working with other services

Opinions of hostel staff often not valued

Hostel managers described feeling as though their opinions were not valued by other services and that they were often excluded from communications or plans involving their clients, despite often being the person that knew the client the most.

Lack of communication around discharge planning

Several responses highlighted a lack of communication with hostel staff and community teams around discharges from hospital, which then led to swift readmissions. Hostel managers felt that assessments conducted in hospitals did not take into account the environment or situation to which a person would be discharged. This meant that people deemed ‘medically fit’ were being discharged into the community where they had limited access to the care and support they needed.

‘Failed discharges due to self-discharge or poor discharge planning has led to two residents returning to hospital within 72 hours and [in] worse condition than previously. Poor communication with NHS teams and CMHT [community mental health team] has led to residents being discharged to the community who were medically fit but not able to manage in the community independently.’

Self-discharges were also commonly reported, which could be problematic for hostel staff, who rarely received any information as to what had occurred during the admission.

Barriers for clients accessing services

Hostel managers described a range of barriers to accessing mainstream services for their clients. These included the view that services did not understand the needs of clients and what might be required to enable clients to engage with them. For example, managers described how clients' cases with various services were often closed, because of poor engagement. This then left clients unsupported and hostel staff responsible for their wellbeing.

‘There is a lack of flexibility from statutory services in terms of the client group that most need access to these services and their difficulty engaging. Services do not recognise that non-engagement is a support need.’

‘[what's needed is] Services being more flexible in taking on clients and providing support, such as accepting clients with multiple needs or accepting clients who failed to attend appointments (in some cases the need for which they needed support prevented them from accessing the said support).’

The lack of consistency in personnel within services was a further challenge to engagement.

‘...there is a need for more workers so that there's a consistency in the same professional seeing the clients so that there's an improvement in their relationship/support.’

Managers highlighted how clients with substance misuse disorder were often excluded from accessing services and support vital for their recovery. This was raised particularly regarding social services (detailed below) and mental health services. For example:

‘Mental health services refuse our customer referrals without even assessing our customers stating it is drug induced when under NICE guidelines they have a statutory duty to accept people with dual diagnosis. We are left to support the most high risk, complex people with zero support from statutory services. It is a disgrace. Homeless people and people who use substances are entitled to services and care but are failed by these services.’

Similarly, staff felt left to support people following mental health crises.

‘After one client was admitted to hospital after overdosing and admitting to wanting to end his life, he was discharged very soon after, and there was no follow up when he came back to the hostel in regards to preventing a further incident or helping him deal with his mental health.’

In addition, it was reported that professionals focus so much on substance use that other illnesses and symptoms can be overlooked, resulting in delayed diagnoses, lack of attention to long-term conditions and further deterioration of health.

Digital exclusion was also raised as a barrier to access. This included the use of online services for booking appointments, which many people did not have access to. In addition, people without a phone did not receive some appointments or reminders and so ended up missing appointments for this reason.

‘[There is a need to] Improve accessibility to the services, for example some services require users to book appointments or support online, where they do not have access to such equipment or the knowledge to use it.’

In-reach support

Hostel managers reported a range of different in-reach support for their clients, with some receiving none. Two-thirds of services (65.5%, n=38) reported receiving some support from drug and alcohol services. Nearly half (48.3%, n=28) had some support from nursing in-reach, 48.3% (n=38) from mental health practitioners and 29.3% (n=17) from GPs. Although not in place in many services, some managers shared that occupational therapists embedded within teams can be valuable in supporting people with functional needs and building a case for Care Act assessments.

Where there was no health in-reach, managers highlighted how important they felt it would be for supporting clients to engage around their health, including support with dressings and wound care, medication and long-term condition management. Dental care support was also highlighted as an unmet need.

Adult social care

Care Act assessments

A total of 133 Care Act assessment referrals were made by hostel staff over the previous year. In total, 93 residents across all services currently had a personal package of care, but managers felt there were an additional 110 clients (5%) who needed but not have one. When asked about the adequacy of response to Care Act assessment referral in Phase 2, managers responded that 40 of the 62 referrals (65%) had received an adequate response.

Managers highlighted a range of issues that their clients needed help with, including support with personal care, medication management, maintaining their rooms in a habitable way, healthy meals and preventing isolation.

The process of obtaining support through Care Act assessments was felt to be lengthy. One manager shared that there were clients who were rejected from some services because of not meeting the threshold for certain services, but who were also rejected by other services because of having support needs that were deemed ‘too high’.

‘Social services are often slow to respond or arrange assessments. Staff on site will often go above and beyond to support the client but this helps mask the problem.’

For Care Act assessments made in hospitals, it was felt they often did not reflect the realities of life in the community. There was a sense that assessments needed to be more thorough, take place in situ and involve members of hostel staff where appropriate.

‘When Social Services contact a resident they [the resident] states that they are fine and do not require support. Further investigation/room checks by Social Services would have been beneficial in these circumstances.’

If social services could not contact a client or the client refused to see the assessor, their case would often be closed.

‘Challenges are around finding social workers being available to assess cases. It has also been my experience that social workers look to close cases as soon as possible if they are allocated to a client.’

Respondents felt that clients, particularly those with mental health and/or substance misuse issues, were frequently failed by the system. Hostel managers reported social services rejecting assessments of clients because of the belief that their substance use and self-neglect were lifestyle choices. One explained:

‘When we raise safeguarding alerts or request care act assessments for our customers social services staff are judgemental stating they are not eligible due to their substance misuse or self-neglect is a life style choice.

There were also positive responses to Care Act assessment requests. Factors that were associated with positive outcomes included collaboration with other services, notably the involvement of occupational therapists taking a proactive approach to initiating Care Act assessments and having teams that are experienced in the process.

‘The assessments that have been undertaken this year have all had positive outcomes and the partnership between our project and other agencies have proved to be effective.’

‘Our OT has the clinical title and they have achieved results and outcomes that would either take us a long time or would not be able to achieve as health professionals do not listen to our concerns.’

Safeguarding referrals

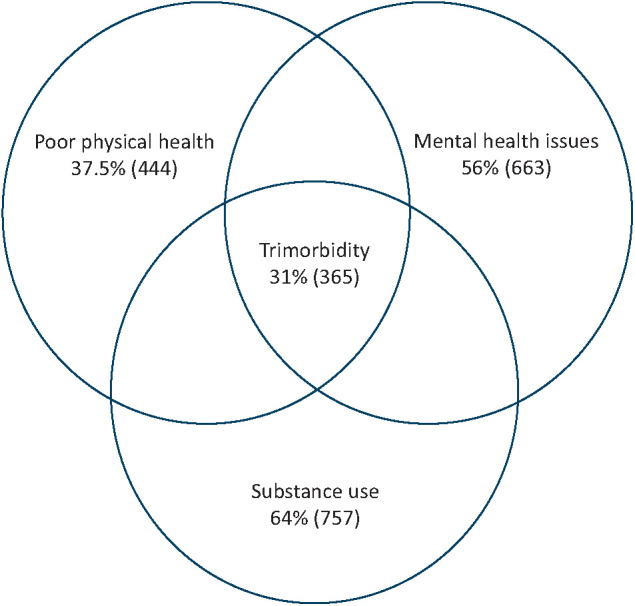

Of the 58 hostel managers, 48 reported that they had made safeguarding referrals over the past year, for a total of 257 (10.91%) clients. In Phase 2, respondents were also asked how many clients had repeated safeguarding referrals, key themes and how many of the referrals had an adequate response. Of the 32 hostels that completed the updated survey, there were 135 (11.4%) clients for whom safeguarding referrals had been made, with 55 of those (40.7%) needing repeated referrals. The key themes of reason for referral are captured in Fig 4.

Fig 4.

Key themes for safeguarding referrals.

Similar to challenges around Care Act assessments, hostel managers also reported difficulties relating to safeguarding referrals, which included the length and complexity of the process, the reliance of cooperation from the client and the siloed nature of services preventing person-centred and holistic assessments and approaches.

Managers reported receiving an adequate response to 59 out of the 135 safeguarding referrals (44% of referrals). Several referrals were ongoing or recently made at the time of responding to the survey; thus, overall success rates might be higher.

Referrals for self-neglect often failed to result in an adequate response, particularly where clients with substance use were deemed to have capacity. This left hostel staff to support people with extremely complex needs.

‘Safeguarding referrals for self-neglect usually do not get addressed adequately as residents are assumed to have capacity.’

‘I have been to 3 serious case reviews when customers died after I have made safeguarding alerts for self-neglect which were rejected by social services citing life style choice. Each review concluded that social services must not reject cases citing lifestyle choice but it keeps happening. There is no learning, no change and people keep dying.’

Managers reported factors related to positive outcomes linked to safeguarding assessments included collaboration with other services and having a named social worker. Successful outcomes included clients being moved to more suitable placements, professionals meetings being arranged and packages of care being put in place.

Unplanned hospital attendances and ambulance call outs

Managers reported that 5% of clients (n=108) had had more than three unplanned hospital visits in the previous month.

In Phase 2, managers were also asked specifically about ambulance call-outs in the previous month. Out of the 32 hostels, managers reported needing to call an ambulance a total of 100 times for 62 different clients over the previous month. For at least half of those clients, an ambulance was called at least twice and, for a small number of clients, an ambulance had been called three or more times. Qualitative data showed that these repeated calls were often for mental and psychiatric concerns.

Qualitative data also showed that a small number of responses described situations in which ambulance services were called but did not take the client to hospital. The reasons for this included clients refusing to go to hospital and ambulance staff not feeling that transfer to hospital was necessary, particularly if the crisis was deemed to be related to substance misuse rather than mental health issues. This left staff having to deal with very difficult situations without specialist support. One manager reported:

‘We have some clients with MH [mental health] related needs that we would consider high-when Crisis team or ambulance is requested to support, often they don't attend, or if they do they leave as it's felt the client's behaviour is substance use related rather than MH.’

Move-on options

In phase 2, managers were asked how many of their current clients they believed should be in a different service beause of the level of their needs.

Of the 32 services, 25 had at least one individual where the manager believed they needed high-support accommodation, with some having multiple such clients. Out of the 25 services, there were 102 clients (9% of all clients) identified as having needs that were too high for the service they were in.

Managers were also asked about the availability of move-on options for their clients. Of all managers, 52% had no options or rarely had access to move-on options. Only one hostel manager reported that they had adequate move-on options for their clients.

Waiting lists for accessing different move-on options were long and thresholds for eligibility were high. The lack of options was particularly evident for people who used substances and had high levels of care needs.

Based on data from the open and closed questions, particular types of accommodation that were called for among responders included more care homes, more sheltered accommodation, Housing First with floating support, specialist options for women and smaller units for people with mental health issues. (Housing First is an international evidence-based approach that prioritises access to permanent housing with tailored support and case management for people experiencing homelessness with multiple and complex needs.)

‘There is a block in accessing extra care and sheltered living in this borough-there is also no pathway into extra care or Sheltered living for people who suffer with long standing substance misuse issues. Once this can be accessed it can take up to 12 months to get a client access-this is a current issue for us with one particular client who we have been back and forth with for 18 months plus.’

In addition, the process for accessing the options that are available was thought to be complex.

‘It's challenging to access the service and homes they need. There is limited information on who to contact, some pathways require bidding however some clients do not have the capacity to do so. There needs to be a way of accessing these homes that take into consideration their capabilities.’

Deaths within services

In Phase 2, managers were asked about the number of clients who had died within the previous 12 months. Out of the 32 hostels, there had been 28 deaths in the past year (equivalent to 2% of clients). Of these deaths, 15 (54%) occurred within the hostel, eight (29%) in hospital and two (7%) in a hospice, with three being elsewhere (not specified). Most deaths (60%) were believed to be related to overdose, accident or suicide, while the remaining were caused by a range of conditions, including brain haemorrhage, cancer, heart failure or heart attack, multiple organ failure caused by infection and liver disease.

Discussion

This survey demonstrates need among people residing in a range of homeless services in London at one point in time. High levels of unmet needs were identified. Managers reported that nearly two-thirds of clients had substance use disorder, over half experienced mental health issues, and over one-third had significant physical health issues that impacted their daily lives. Reportedly, one-third of clients had a combination of all three issues affecting their daily lives.

The numbers of people reported to be experiencing issues such as serious self-neglect, difficulties around medication management and poor mobility were considerable. These issues represent significant challenges for each individual and the services supporting them. For example, 224 individuals required support to take their medication, which falls outside the remit of most hostel staff, yet the repercussions of non-adherence to medication are serious.

Despite the high level of need of this population, hostel managers described a range of barriers that their clients experienced in accessing health and care services. Significant delays or lack of access to appropriate support can be extremely detrimental and result in further deterioration in their clients' conditions.

A lack of person-centred and trauma-informed approaches by health and care services was highlighted as a barrier to accessing services. Improving the relational continuity in services can provide opportunities to build trusting relationships, which can be vital to engagement and recovery, particularly for people who have experienced trauma. Poor engagement needs to be recognised as a need in itself, because it is often related to this lack of trust, fear, past trauma and previous negative experiences.9 It also needs to be recognised that substance use is often used by people with a history of trauma as a means to self-soothe or self-medicate.6,18

A hospital admission can serve as an important opportunity to address someone's health and care needs. Hostel staff are in an ideal position to help bridge the gap and provide support to health teams, because they are often trusted by their clients and have a key role in that person's day-to-day life. Their input into hospital multidisciplinary team meetings and Care Act assessments can be invaluable for understanding the full scope of the individual's needs for effective discharge planning. An appropriate discharge destination that is able to fully meet the individual's needs is essential to prevent unsafe discharges, avoidable readmissions, morbidity and mortality. Follow-up assessments within the community might be essential to ensure that needs are addressed.

People experiencing homelessness who have substance use disorder were often discharged from services because of poor engagement or are not actively supported to stay during a hospital admission. In addition, referrals for Care Act assessments for unmet care needs or safeguarding concerns were often rejected. One reason frequently given for the above is that they ‘have capacity’ to refuse treatment or, in the case of self-neglect, have capacity around their ability to self-care. Firstly, having mental capacity should not prevent a response to Care Act or safeguarding referrals. In addition, undertaking mental capacity assessments in people with substance use disorder can be complex. For example, people with alcohol dependency often have frontal lobe injury and might be deemed to have decision-making mental capacity when, on fuller examination, it is clear that they have impaired executive functioning. Executive capacity is the ability to actually use that decision, which is often impaired by alcohol dependence.19 It is important that, before someone is deemed to have the mental capacity to refuse treatment, every effort is made to consider executive functioning,20 with input and discussion from frontline hostel and/or outreach staff to obtain collateral history.

Given the barriers and challenges described, it often falls on hostel staff to manage clients with significant self-neglect and poor health, in the absence of appropriate support. They try to support their clients to access the care they need by submitting referrals for Care Act assessments or safeguarding, encouraging them to engage with services and advocating for them when they have missed appointments or been refused care. This is an ongoing process, often with unsatisfactory results and places a huge strain on hostel staff, contributing to high rates of staff burnout.14

Homelessness services are not resourced to provide the level of support needed by people with care needs. Although National Institute of Health and Care Excellence (www.nice.org.uk/guidance/ng214) guidance recommends that care packages should be based on needs rather than on biological age; this frequently does not happen for residents in hostels. Although hostel environments and their staff are rarely equipped to support individuals with care needs, many people remain in hostels without adequate support or end up back in hospital. In the absence of sufficient alternatives, hostels are having to flex to support people as best they can. An additional problem with this is that supporting people who are inappropriately housed disproportionately redirects resources away from other residents and undermines efforts to move people away from homelessness more rapidly.

Over the past year, hostel managers reported 10 client deaths among their services relating to physical ill health and a further 18 related to an accident, overdose or suicide. Previous research has highlighted how hostel residents with advanced ill health rarely have access to palliative care services for several reasons, and often die unsupported following crisis hospital admissions.13

This survey strengthens the evidence of the need for a greater range of accommodation options with access to support, such as specialist care homes for people who are young with substance use disorder and/or mental health difficulties. In addition, more in-reach from peripatetic multidisciplinary teams (including primary care) into existing hostels is needed to support the development of relationships and engagement with services that can help address unmet health and care needs.

Strengths and limitations

Strengths

This is a large survey encompassing input from 58 services for people experiencing homelessness across London, with a wide representation of service providers. The total number of clients that responses related to was 2,355. It contained a combination of closed questions and also gave an opportunity for free-text responses following open-ended questions. This increased the richness of the data extracted. Many of the findings are consistent with other qualitative data collected within hostels, but this survey has, in addition, provided an opportunity to quantify the level of unmet need in a sample of London hostels.

Limitations

This was a non-clinical survey and depended on a hostel manager knowing all of the clients within the hostel. There were no individually collected data and the level of detail to which the manager knew about all of the conditions affecting the clients within the services is likely to be variable. If anything, this is likely to underestimate levels of need.

Conclusion

People experiencing homelessness have some of the worst health outcomes in society and are being failed on many levels by our health and social care system. To address this inequity, there is a need for much greater accessibility to compassionate, person-centred and trauma-informed services.

Without significantly more support, hostels are not an appropriate setting for people with high care and support needs. Despite this, many people with high needs remain in homeless hostels. Frontline homelessness staff often struggle to get their concerns, including safeguarding concerns, taken seriously. This leaves them to support people with high need without adequate training or support, in an environment not designed for this purpose. There is a clear need for statutory services to provide more essential support to this population as well as for more alternative places of care and support.

In the meantime, it is essential that frontline homelessness staff and people with lived experience of homelessness are involved in health and care planning. In-reach into hostels and flexible, person-centred, trauma-informed health and social care are essential in addressing the challenges described.

We are all striving for equitable access to healthcare. The Inverse Care Law21 highlights how those with the most need receive the least. This could not be clearer than for people experiencing homelessness. Proportionate universalism22 states that those with the greatest need should receive the greatest resource. Equitable care does not mean providing the same for everyone. It involves considering the unique needs of different groups and providing them with the support that they need to achieve the same health outcomes. The evidence in these findings outlines how this is not currently being delivered, and should be addressed as a matter of urgency with more in-reach support to people living in hostels and more alternative places of care.

Supplementary material

Additional supplementary material may be found in the online version of this article at www.rcpjournals.org/content/clinmedicine:

S1 – Survey questionnaire.

References

- 1.Bowen M, Marwick S, Marshall T, et al. Multimorbidity and emergency department visits by a homeless population: a database study in specialist general practice. Br J Gen Pract 2019;69:e515–25. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 2.Lewer D, Aldridge RW, Menezes D, et al. Health-related quality of life and prevalence of six chronic diseases in homeless and housed people: a cross-sectional study in London and Birmingham, England. BMJ Open 2019;9:e025192. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 3.Aldridge RW, Menezes D, Lewer D, et al. Causes of death among homeless people: a population-based cross-sectional study of linked hospitalisation and mortality data in England. Wellcome Open Res 2019;4:49. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 4.Deaths of homeless people in England and Wales. London; Office for National Statistics, 2022. www.ons.gov.uk/peoplepopulationandcommunity/birthsdeathsandmarriages/deaths/datasets/deathsofhomelesspeopleinenglandandwales [Accessed 15 June 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 5.Vickery KD, Winkelman TNA, Ford BR, et al. Trends in trimorbidity among adults experiencing homelessness in Minnesota, 2000-2018. Med Care 2021;59 (Suppl 2):S220–7. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 6.Hertzberg D, Boobis S. Unhealthy state of homelessness 2022: findings from the homeless health needs audit. London; Homeless Link, 2022; https://homeless.org.uk/knowledge-hub/unhealthy-state-of-homelessness-2022-findings-from-the-homeless-health-needs-audit/ [Accessed 15 June 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 7.Centre for Homelessness Impact . Hostels. London; Homelessness Impact; 2021; www.homelessnessimpact.org/intervention/hostels#:∼:text=The%20goal%20of%20homeless%20hostels,a%20more%20sustainable%20housing%20solution [Accessed 15 June 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 8.McNeill S, O'Donovan D, Hart N. Access to healthcare for people experiencing homelessness in the UK and Ireland: a scoping review. BMC Health Serv Res 2022;22:910. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 9.Armstrong M, Shulman C, Hudson B, et al. Barriers and facilitators to accessing health and social care services for people living in homeless hostels: a qualitative study of the experiences of hostel staff and residents in UK hostels. BMJ Open 2021;11:e053185. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 10.Homeless Link . The future hostel: the role of hostels in helping to end homelessness. London; Homeless Link, 2018; https://homelesslink-1b54.kxcdn.com/media/documents/The_Future_Hostel_June_2018.pdf [Accessed 15 June 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 11.Crisis . Home for all: The case for scaling up Housing First in England. Crisis, 2021; www.crisis.org.uk/media/245740/home-for-all_the-case-for-scaling-up-housing-first-in-england_report_sept2021.pdf [Accessed 15 June 2023].

- 12.Rogan-Watson R, Shulman C, Lewer D, et al. Premature Frailty, geriatric conditions and multimorbidity among people experiencing homelessness: a cross-sectional observational study in a London Hostel. Housing Care and Support 2020;23:77–91. [Google Scholar]

- 13.Shulman C, Hudson BF, Low J. End-of-life care for homeless people: a qualitative analysis exploring the challenges to access and provision of palliative care. Palliat Med 2018;32:36–45. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 14.Maguire N, Grellier B, Clayton K. The impact of CBT training and supervision on burnout, confidence and negative beliefs in a staff group working with homeless people. http://eprints.soton.ac.uk/id/eprint/155113 [Accessed 15 June 2023].

- 15.The University of Edinburgh . SPICT-4All. www.spict.org.uk/spict-4all/ [Accessed 15 June 2023].

- 16.Downar J, Goldman R, Pinto R, et al. The “surprise question” for predicting death in seriously ill patients: a systematic review and meta-analysis. CMAJ 2017;189:E484–93. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 17.Clarke V, Braun V, Hayfield N. Thematic analysis. In: Smith J.A., ed., Qualitative psychology: a practical guide to research methods. London; SAGE Publications, 2015. p 222–48. [Google Scholar]

- 18.Alexander AC, Waring JJC, Olurotimi O, et al. The relations between discrimination, stressful life events, and substance use among adults experiencing homelessness. Stress Health 2022;38:79–89. [DOI] [PMC free article] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 19.Preston-Shoot M, Ward M. How to use legal powers to safeguard highly vulnerable dependent drinkers. London; Alcohol Change UK, 2021; https://alcoholchange.org.uk/publication/how-to-use-legal-powers-to-safeguard-highly-vulnerable-dependent-drinkers [Accessed 15 June 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 20.Local Government Association . Care and support and homelessness: top tips on the role of adult social care. London; Local Government Association, 2022. https://www.local.gov.uk/sites/default/files/documents/25.207%20Care%20and%20Support%20and%20Homelessness%20AA%20WEB.pdf [Accessed 15 June 2023]. [Google Scholar]

- 21.Tudor-Hart J. The inverse care law. Lancet 1971;291;7696. [DOI] [PubMed] [Google Scholar]

- 22.Marmot M, Goldblatt P, Allen J, et al. Fair society, healthy lives (The Marmot Review). London; Institute of Health Equity, 2010. https://www.instituteofhealthequity.org/resources-reports/fair-society-healthy-lives-the-marmot-review/fair-society-healthy-lives-exec-summary-pdf.pdf [Accessed 15 June 2023]. [Google Scholar]